Introduction

The building type of the ancient library is a significant one that, since the invention of the institution of the public library as a space for the storage of knowledge, open and accessible to the public in the late classical period in Greece, all important Hellenistic and Roman cities and towns boasted of having. Its architectural form appears with a great diversity of scale and monumentality from case to case, ranging from a single-room detached building to a multiroom complex or a part of a complex. Taking into account the added difficulty of the uncertainty and multiple readings of the fragmentary state of preservation of libraries, which is inherent in the interpretation and reconstruction of the archaeological record, the library is not as easily identified as other building types such as the theater and the temple. Even in cases that researchers identify buildings as libraries, there is no systematic approach for their reconstruction, pointing to all different possible ways of reconstruction.

A first effort to order and formalize the design of Roman libraries was by Makowiecka (Reference Makowiecka1978), who suggested that Roman libraries could fit into eight schemata. However, some libraries combine features from multiple schemata, as the Library of Rogatinus combines a semicircular main hall with two storage rooms of one schema and a portico of another. Thus, these schemata do not account for all known Roman libraries, and they mislead us to believe that we cannot identify components of one schema in another. Ultimately, they understate the diversity in the design of libraries and the variation with which we can reconstruct a library.

The author proposes parametric shape grammars as a methodology to tackle the problem of defining the building type of the ancient library in its entire variability visually, meaning the problem of defining the sum of mandatory and variable architectural characteristics. Generative grammars (Hodder, Reference Hodder1982; Chippindale, Reference Chippindale1992) and shape grammars (Stiny and Gips, Reference Stiny and Gips1972; Stiny, Reference Stiny1980) are not new in archaeological research (Mamoli and Knight, Reference Mamoli and Knight2013; Mamoli, Reference Mamoli2019). They have been used as a systematic methodology for classification and reconstruction (Knight, Reference Knight1994; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Vereenooghe, Wonka, Paap and Van Gool2006; Dylla et al., Reference Dylla, Frischer, Müller, Ulmer and Haegler2009). Parametric shape grammars define the rules parametrically, so that they can apply with a range of valid values in specific parametrically defined dimensions. The most well-known example of a parametric shape grammar for the analysis of historical architecture is the Palladian Grammar (Stiny and Mitchell, Reference Stiny and Mitchell1978).

This paper presents a parametric shape grammar that summarizes the design principles of ancient libraries visually, and that can generate possible plans of ancient libraries, known and hypothetical. Also, the paper uses frequency analysis to rank the rules based on frequency in the derivations of the known libraries, and ultimately, to evaluate their importance in the definition of the building type of the ancient library, and their probability of occurring in other libraries in the future.

The data from the archaeological record of ancient libraries

The study of the history of the ancient library and its architectural form has been based on the archaeological record of 17 buildings located around the Mediterranean that have been identified as ancient libraries based on the reference to epigraphic and/or literary sources (Langie, Reference Langie1908; Cagnat, Reference Cagnat1909; de Gregori, Reference de Gregori1937; Götze, Reference Götze1937; Callmer, Reference Callmer1944; Wendel, Reference Wendel1949; Makowiecka, Reference Makowiecka1978; Johnson, Reference Johnson1984; Strocka, Reference Strocka1981, Reference Strocka2000, Reference Strocka2003; Hoepfner, Reference Hoepfner2002; Mamoli, Reference Mamoli2014). These buildings survive in various degrees of preservation with some surviving only in their foundations. One of these cases is the Library at the Serapeion. Only the foundation trenches of the walls of the basement level remain, from which we can deduct to some extent the plan of the first floor. In other cases, that the libraries are unexcavated, their architectural form is known only through ancient map depictions, such as the Library at the Porticus Octaviae, partially known through the 3rd-century marble map of Rome. Thus, the corpus of 17 libraries is reduced to only 15 when we consider the remains of their main hall, as are given in Figure 1. The data in the archaeological record consist of descriptions, state of preservation plans, measurements of certain architectural features, and the building as a whole. Surviving evidence either verifies or excludes the existence of an architectural feature and sometimes there is no evidence to determine whether an architectural feature was part of the original design or not.

Fig. 1. Redrawn state of preservation plans of the 15 libraries that have building remains of the main hall in chronological order, foregrounding the fragments of the original form of the hall of the libraries, in scale 1:1000 (author's drawing). (b) Library of Pergamon; (c) Academy of Plato; (d) Library of Rhodes; (e) Augustan Palatine Library; (g) Library at the Templum Pacis; (h) Domitianic Palatine library; (i) Pantainos Library; (j) Celsus Library; (k) Ulpian Library; (l) Neon Library; (m) Library of Nysa; (n) Melitine Library; (o) Hadrian's Library; (p) Library in the Forum of Philippi; and (q) Library of Rogatinus.

Early libraries had a nondiscrete rectangular main hall with no characteristics of monumental interior design, whereas most of the later libraries in the Roman Empire exhibited a formalized and monumentalized main hall, often apsidal in plan, with permanent recesses on the walls, the niches, preceded by a podium, in which often stepped a colonnade. Figure 1 shows the 15 libraries with an identified main hall at a scale of 1:500 to foreground these characteristics.

Wooden bookcases, known as armaria, contained books and busts of poets and philosophers and were most often embedded in the marble-framed niches (Fig. 1j–o,q), rectangular recesses in the walls about 1 m wide and 60–90 cm deep and about 2 m high. Not all libraries had niches though. Some early Hellenistic and some small Roman libraries did not have monumental interior design and had walls too thin (Fig. 1i,p) to include niches. In these cases, we can assume that the armaria were set directly on the floor against the walls.

The most consistent element of libraries was a focal point emphasizing the axis of the main hall, either through architectural or visual design. In smaller libraries in the corpus, where there is no evidence of a constructed focal point, the focal point was established by the patron statue, perhaps of the goddess Athena or of the emperor, set against the floor on the axis of the main hall. In the libraries with monumental interior design, an emphasized point in the center of the back wall hosted the statue. It had a diverse form: it was a projection in the podium (Fig. 1b,g), or a widened niche in the wall (Fig. 1h), or a sizable semicircular apse (Fig. 1j,n), or an aedicula (Fig. 1q), and was in one (Fig. 1g,h,j,l,n) or two levels (Fig. 1o,k).

A raised platform, the podium, often preceded the niches and the focal point. The podium was either U-shape along the side and back walls of the main hall (Fig. 1g,h,j,l,o), or interrupted in front of the focal point, thus forming two L-shaped podia (Fig. 1k,m,q). However, the podium is not an essential element of the main hall. Some libraries in the corpus show evidence of marble-paved floor from wall to wall, which excludes the possibility of a podium (Fig. 1i,n). When it exists, it works as a visual threshold between the niches and the space in the main hall of the library and supports an interior colonnade that framed the niches and the focal point (Fig. 1j,k,o,q). In cases that it is low enough or preceded by steps, it functions as a sitting area, thus transforming the main hall into an auditorium (Fig. 1h,q). Table 1 shows the occurrence or nonoccurrence of these architectural features in the known Roman libraries.

Table 1. The occurrence of niches, podium, column screens, focal point, windows, and stairs in the Roman libraries

The ✓ signifies the existence, and the X signifies the absence of a characteristic in a library; the dash signifies that there is not enough evidence to secure the existence or not of a characteristic.

In addition to the main hall, some libraries had additional spaces such as rooms attached to the main hall or exedras that opened from the stoa. Thus, the library plan varied from a single-room building to a whole complex, to a single room or series of rooms part of a larger complex with symmetric or asymmetric arrangements. The libraries that include additional rooms are given in Figure 2 to exemplify the variation of the layout in scale and design.

Fig. 2. Redrawn state of preservation plans of the libraries that have an identified main hall and additional spaces, as part of a larger complex, and as a complex themselves, with asymmetric or symmetric arrangements (author's drawing): (b) Library of Pergamon; (p) Library in the Forum of Philippi; (q) Library of Rogatinus; (c) Academy of Plato; (g) Library at the Templum Pacis; (i) Pantainos Library; and (o) Hadrian's Library.

This analysis does not take into account the use of a peristasis, stairs, and the duplication of halls that have been suggested by earlier scholars as programmatic features of the Roman libraries. A fresh look at early evidence in the light of recent discoveries cannot confirm them as programmatic features. Firstly, the second hall in the Domitianic Palatine Library, the primary evidence for the duplication of halls has been proven as a later addition (Iacopi and Tedone, Reference Iacopi and Tedone2005–2006). Secondly, the corridors by the sidewalls of the Library of Celsus, the primary evidence for the duplication of halls, have been proven as unroofed gaps with drains for the rainwater (Strocka, Reference Strocka2003). Finally, the steps behind the Library of Celsus, the primary evidence for steps to upper floors, have been proven that led to an underground funerary chamber (Strocka, Reference Strocka2003). The absence of these features as programmatic for Roman libraries brings the Greek and Roman libraries closer in type and undermines their clear distinction.

The main challenge in defining a building type for the ancient library has been the variation in monumentality and formality, a quality that appears throughout its history and is especially apparent between the Greek and Roman periods. Generally, the increase in scale and monumentality progressed with time, that is, simpler forms appeared early on in the Hellenistic period, while more elaborate forms appeared in the Roman high imperial period. An early effort of the classification of Greek and Roman libraries distinguished them as simple versus monumental (Callmer, Reference Callmer1944). The criterion of monumentality further classified Roman libraries into Imperial libraries in Rome versus provincial libraries (de Gregori, Reference de Gregori1937; Johnson, Reference Johnson1984). Another classification of Roman libraries has distinguished them as of the eastern versus western type based on whether the main hall is wide or long, respectively (Callmer, Reference Callmer1944; Makowiecka, Reference Makowiecka1978). However, this is not to say only the Greek libraries were simple because simple and elaborate forms appeared throughout the Roman period as well. Primarily, the main hall of such Roman libraries appears with a variety of designs and different degrees of monumentality: with a rectangular or apsidal, wide or elongated plan, with or without interior colonnade, podium, niches, and a focal point. The outcome of these classifications has been to create types with very few instances in each of them and quite some exceptions that are not very helpful in foregrounding their similarities and placing them in the same conceptual tradition of design, thus establishing the library as a distinct building type. An additional layer of difficulty in defining a building type for libraries is that libraries share characteristics with other building types of classical architecture. For example, stoas and temples also have niches and podiums (Johnson, Reference Johnson1984). All these make researchers very hesitant in identifying a building as a library, and even when the identification is secure, they do not know how to reconstruct it.

The library grammar

To overcome the conundrum of defining a concrete theory about the building type of the ancient library, the author has developed a parametric shape grammar (Figs. 3–15) that summarizes and encodes in design rules, the design principles that occur in the 17 cases of known ancient libraries (Mamoli, Reference Mamoli2014). The methodology includes three steps: firstly, the bibliographical review of measurements and state of preservation drawings, primarily plans but also sections and elevations where the archaeological remains are at a sufficient height; secondly, the compilation of this evidence in a database that will inform the parameters of the rules of the grammar with a valid range of values; and thirdly, the design of the grammar in two dimensions in plan that consists of 91 design rules, subdivided into 12 stages that roughly correspond to the generation process of a library. The first six generate the layout of the main hall with its interior design, including the podium, the niches, the focal point, the interior colonnade, and the entry. The final six stages generate the general layout of the building or the building complex with the side rooms, the stoas, the exedras, the entrance, and the courtyard if any. The rules include metadata specified by letters of the alphabet that point to each library that shows evidence in the archaeological record for each rule.

Fig. 3. The initial shape of the library grammar.

Fig. 4. Rules in stage 1 that generate the main hall of the library.

Fig. 5. Rules in stage 2 that generate the podium in the main hall and define the location of an interior colonnade, if any.

Fig. 6. Rules in stage 3 that place an interior colonnade in the main hall and add pedestals, half-pilasters.

Fig. 7. Rules in stage 4 that generate niches or armaria in the main hall.

Fig. 8. Rules in stage 5 that generate the focal point in the main hall.

Fig. 9. Rules in stage 6 that generate the entrance to the main hall.

Fig. 10. Rules in stage 7 that generate the entry of the main hall and add extra rooms to the library.

Fig. 11. Rules in stage 8 that close the exterior walls of the main hall and secondary rooms and define the threshold.

Fig. 12. Rules in stage 9 that define the threshold as a single stoa, a U-shape stoa, or a peristyle and further treat the stylistic features of the stoa.

Fig. 13. Rules in stage 10 that generate exedras or rooms in the back of the stoas.

Fig. 14. Rules in stage 11 that treat the entry to the complex of the library as steps, an engaged colonnade, a propylon, or shops in the back of a stoa.

Fig. 15. Rules in stage 12 that treat the interior design of the library side rooms as banqueting halls, auditoria, or a storage room.

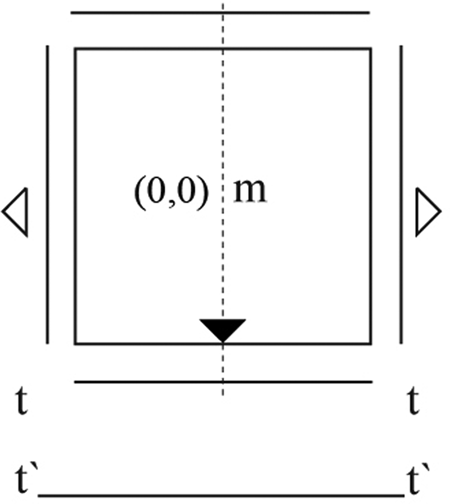

The initial shape is a parametric cell with bilateral symmetry that stands for the main hall of the library and includes labels for the aggregation of additional rooms on the sides as well as a threshold in the front façade (Fig. 3).

The main hall of the library acquires its actual shape, rectangular or apsidal, and dimensions after its instantiation in stage 1 with the rules 1 or 2 (Fig. 4). These rules label the side and back walls of the library as walls to accept the bookcases or niches, the focal point, and the entry wall of the main hall. Subsequently, the optional rules 3 and 4 define the subdivisions in a rectangular or apsidal room, respectively, where the podium is going to be inserted and lead to the next stage that adds a podium. In case neither rule 3 or 4 is selected, the user skips the next two stages that generate the podium and the colonnade and moves directly to stage 4.

In stage 2, rules 5–10 add different types of podia: at either a distance p d from the wall of the library or directly against the walls of the library as a continuous U-shape podium or two L-shape podia that stop precisely in front of the focal point.

In cases that the podium is precisely against the wall of the library, the label c leads to stage 3 for the optional addition of a colonnade that inserts end columns in the corners and the endpoints of the podium (rules 11, 12) and then propagates the colonnades based on a standard interaxial dimension (rules 13, 14). Rules 15–17 generate the stylistic characteristics of the columns: half pilasters against the wall as reflections of the columns, column bases to denote an Ionic or Corinthian order, and finally pedestals to the columns connected with steps, thus giving the effect of seating space around the main hall.

Stage 4 offers different ways for the placement of the armaria: rules 18 and 19 add a niche in each intercolumniation and rules 20 and 21 add a niche in every other intercolumniation on the side and back walls of libraries that have a podium and interior colonnade. Rules 22 and 23 add niches in libraries with no podium and interior colonnade; rules 24 and 25 add armaria against the walls of libraries without niches, podium, and interior colonnade. Lastly, rules 26 and 27 erase the labels and thus allow for the main hall without armaria, as in the Hellenistic libraries that functioned as a banqueting hall.

Stage 5 of the grammar generates the focal point of the library in various forms: rule 28 generates a projection in the podium, rules 29–32 generate a recess in the wall, rectangular or semicircular with or without a projection of the wall in the back, rule 33 generates an aedicula. Lastly, rules 34 and 35 add a statue against the wall on the floor or the podium.

Stage 6 adds the entry on the front wall of the library. Rules 36 and 37 add one or three doorframes, respectively; rules 38 and 39 add one opening in antis with tripartite or quintuple division, respectively. Rules 40–43 further specify the style of the posts as Doric or Corinthian columns, half-columns, or piers.

Stage 7 takes the computation at the scale of the general layout of the library and adds additional rooms by the main hall. Rules 44 and 45 generate symmetrical structures by adding additional rooms with bilateral symmetry, one or two on each side, respectively. Rule 46 generates asymmetric structures, with the main hall being on the side and not on-axis. Rule 47 adds more rooms to the side rooms that have been generated by rule 46. Rules 48 and 49 subdivide the side rooms horizontally and vertically while preserving the bilateral symmetry.

Every room addition also adds a line segment that represents the wall thickness at a distance w. These perpendicular, parallel, and collinear line segments connect in stage 8 (rules 50–53) to create the exterior walls of the main hall and its adjoining rooms. Also, rules 54 and 55 redefine the threshold labels, so that the threshold can either extend beyond the main hall and its support spaces or decrease, so that the exterior walls of the library extend beyond the threshold.

The rules in stage 9 generate alternative variations of thresholds with stoas and courtyards. Rules 56–58 convert the threshold into a linear stoa that either extends to the flanks of the main hall or framed by walls is slightly over the street level or is preceded by a monumental stairway. Rules 59 and 60 further modify the stoa generated by rule 56 into a peristyle or a U-shaped stoa. Rule 61 applies recursively to populate the stoas with columns. The rest of the rules in this stage add stylistic characteristics to the colonnades: rule 62 duplicates the stoa width and adds a second colonnade; rule 63 adds thorakia among the columns; rule 64 subdivides the stoa into two aisles with a low wall, which could support statuary or prevent circulation among statues in the back. Lastly, rule 65 generates a projection of the stoa on the axis of the courtyard that further emphasizes symmetry and axiality.

Stage 10 generates exedras or rooms opening off the stoas for recitations and discussions. Rules 66–69 generate projecting exedras, rectangular (rules 66 and 68) or semicircular (rules 67 and 69), arranged sometimes alternating in combination with each other but always preserving the bilateral symmetry. Rules 70 and 71 place rooms along the back walls of the stoa, one in each corner and the rest parametrically along the back wall. Lastly, rule 72 erases the label t signifying the end of the treatment of the threshold.

Once the parti of the building complex is complete, rules in stage 11 generate the entry to the building complex in the side labeled ee. Rules 73 and 74 specify the entrance in a peristyle, the first creating an entrance opening and the second substituting parametrically part of the wall segment with a colonnade. Rules 75 and 76 specify the entrance in a U-shape stoa, the first adding some steps in the opening, and the second closing the opening with a wall. Rules 77, 78, and 79 generate one, three, and five openings, respectively, and add columns in the interior to continue the order of the peristyle. Rules 80–83 specify the exterior façade of the building complex with one opening; rule 80 adds flanking shops and a stoa; rules 81 and 82 add a monumental tetrastyle propylon with or without two projecting wings; and rule 83 adds a decorative exterior colonnade.

Rule 84 further emphasizes the axis by changing the order of the four or six central columns. Rules 85 and 86 are recursive rules that repeatedly add the columns and the shops in the scheme. Lastly, rule 87 is an erasing rule that erases the labels ee and thus concludes the treatment of the entrance façade.

Finally, rules in stage 12 generate the interior design of the side rooms adjacent to the main hall. Rule 88 generates an auditorium with steps along the sidewalls and a bema on the axis of the opposite wall. Rule 89 generates a banquet hall, in which the door is placed off-axis for the banquet klinai to fit rotationally in the room. Rules 90 and 91 generate offices or stacks with bookcases along the walls and desks placed in the center to support different functions, such as the copying of manuscripts.

The rules include parameters (given in italics) specified by measurements in the archaeological record such as width, depth, height, column diameter, intercolumniation, inter-niche space, and conditions under which they apply. Other dimensions are calculated based on the relationships established. For example, the rules that propagate the columns in the stoas, calculate the distance between the two corner columns tt i and te i (rules 56–60), subdivide it by the number of columns to determine the intercolumniation c i and propagate a pair of columns at a time by subtracting the intercolumniation c i from the space between the end columns tt i and te i (rule 61). Similarly, the rules that add rooms in the side stoas calculate the width of the opening of the stoa o w add one room with length o l (rule 70) and recalculate the remaining space to add more rooms (rule 71) further. Besides, rule 70 increases the stoa, depth st d, and thus returns us to the stage to recalculate the columns in the threshold of the main hall t't'.

We understand that the computer implementation of the grammar, currently in progress with the new cutting-edge software Shape Machine, developed by the Shape Computation Lab at Georgia Tech (Economou et al., Reference Economou, Hong, Ligler and Park2019), will highlight possible gaps in the variables and that the rules will have to be systematized at a higher degree at that point. For example, rules that generate series of objects, such as bookcases or colonnades, and which do not align with the axes, will have to be clarified so that the computer can compute recursively columns and bookcases based on the remaining distance each time. Also, the less worked-out stages, which generate variation that is not critical in the identification of a library, such as stage 12 that generates the interior design of the side rooms, will have to be reworked at a greater detail and precision for a computer to be able to compute them.

Grammar-generated libraries

The application of the rules generates libraries of diverse sizes and monumentality; known libraries in the corpus as well as hypothetical. The user of the grammar can start with the underlying plan of the state of preservation of a library. The plans have been redrawn to follow the same conventions of representation, to integrate evidence brought to light and documented over time in different drawings, and to be deprived of earlier and later building phases and interventions as well as reconstructions. The user selects and embeds the rules in the building remains, either fully or partially. This process involves a lot of decision-making and speculation as the archaeological fragments can generate different maximal lines, that is, different lines of maximum length can emerge from connecting shorter lines, with the assumption that the latter refers to fragments of the same structure. For example, two wall fragments might or might not belong to the same room or building, and therefore, a variety of maximal lines can be identified. Depending on the degree of preservation, the user can secure, speculate, or eliminate the application of some rules. In cases that the building remains present evidence about an architectural feature, the user can either eliminate or select a rule for application. In cases of rule selection, the user can plug in the actual dimensions of the building components as preserved in the archaeological record in the parameters of the rules and reconstruct the plan of the building. A subcase of secure application of a rule is the partial embedding when there is evidence for the embedding of the rule in the building remains but only partially with some tweaking. In these cases, an exclamation mark (!) next to the rule denotes that the particular characteristic is case-specific or exceptional. In cases that the building remains show no or little evidence and require speculation, the user can pick the rule that s/he considers more probable based on the other libraries and generates the corresponding building component based on the site specifications and the other parallels. In this case, an asterisk (*) next to the rule denotes that the rule is speculative.

Figure 16 gives the derivations of all known libraries along with the strings of rules that apply to demonstrate how this works. Rules that occur recursively to generate a series of objects that do not align with the axes defined by labels, such as niches (rules 22, 23), bookcases (rules 24 and 25), columns (rules 61, 85), or rooms in the back of stoas (rule 86), are noted only once. The label tt' that is left in some computations show that the library is part of a more massive complex and that it shares a threshold with other spaces. The derivations of the known libraries showcase the diversity of library plans that the grammar can generate: libraries that consist of the main hall and a threshold, libraries that are part of a larger complex and libraries that are a complex themselves. Some of the computations are secure based on extensive building remains, whereas some are speculative (Mamoli, Reference Mamoli2014, Reference Mamoli2015). In cases of well-preserved libraries, scholars securely propose a reconstruction following traditional methods. The grammar does not add anything to secure current reconstructions and verifies them. In cases of partially or not preserved libraries, scholars are hesitant to reconstruct them visually and usually provide verbal descriptions of reconstructions. The grammar contributes one or more visual reconstructions that we would not have otherwise, for example, the Library at the Porticus Octaviae, as shown with the (*) next to almost all rules needed to generate them.

Fig. 16. Computations of all known libraries with the strings of rules that apply for their generation. Asterisks (*) denote the speculative application of the rule, and exclamation marks (!) denote a not very precise embedding of the rule in the building remains. The layouts of libraries showcase the variation in the scale and monumentality of the main hall and the general layout.

The computation of a well-preserved library, the Library of Celsus in Ephesus is given step-by-step to showcase how the process works. The plan of the Library of Celsus is preserved at a high degree, has been documented precisely through documentation drawings (Fig. 17a), and therefore, its reconstruction is secure. The plan has been redrawn here integrating information from other more recent studies that have attributed some of the walls to neighboring buildings, here noted in gray (Fig. 17b). The redrawn plan of the state of preservation is used here as the underlying plan that helps the user pick the appropriate rules and generate the library (Fig. 18), but for reasons of visual clarity, it is shown only in the first and last step. The computation captures the architectural form of the library, except for some stylistic characteristics such as the polyrhythmic intercolumniations. Since the grammar can generate the forms of libraries well documented and reconstructed with a high degree of certainty, we can evaluate it as a reliable tool for the description, analysis, and reconstruction of building remains of ancient Greek and Roman libraries.

Fig. 17. The state of preservation plan of the Library of Celsus (Wilberg, Reference Wilberg1953; Fig. 3). (b) Author's redrawn plan integrating evidence from more recent studies on which the derivation of the grammar is based (Mamoli, Reference Mamoli2014).

Fig. 18. Computation based on the evidence on the archaeological record that generates with high accuracy the plan of the building as traditional methods restore it.

In addition to the library plans that are captured with certainty by excavation and on-site work, the grammar can also generate other variational schemata of them. By comparison to the actual, these computations can help the researcher understand better the design intent of the building. For example, alternative derivations of the Library of Celsus (Fig. 19) with a different from the actual focal point and by introducing niches to all intercolumniations generate alternative plans with more than double capacity in the storage of books. These computations make us think that the patron and the architect were more interested in the symbolism rather than the functionality of their dedication. Of course, additional furnishings floating in the main hall of the library could also increase the capacity, but this would be counter-productive for such an elaborate interior, and scholars reject it as an interpretation. Thus, we can conclude that the grammar produces novel reconstructions that help the researcher evaluate the design choices of the architect and the patron and gain an understanding of the social aspects of the library.

Fig. 19. Variational computations of the Library of Celsus in Ephesus that based on site specifications, maximize the capacity in books. In comparison to the actual design, they highlight the design intent of the architect and the patron to build a building with a monumental façade with not much interest in maximizing its capacity in books.

For the libraries that are partially preserved or not preserved at all, the grammar can generate speculative and possible reconstructions and thus work as a prediction tool in reconstruction. At the extension of this, the grammar can generate hypothetical library plans that can work as a prediction tool and guidance to any excavation by giving hints as to what kinds of evidence one can look for and where. For the unidentified classical buildings, the grammar can work as an evaluative tool – if the rules of the grammar can be embedded in its state of preservation plan and can generate a possible library plan, then this building is evaluated and interpreted as a possible library. The question is, for any decision of the above that includes speculation, how can we know what is more probable than the rest? How can we know which rule to apply and which architectural component to reconstruct each time?

A complete enumeration of the possible libraries showcases a high complexity; with 91 rules, some of which are mandatory and others optional, and while some can apply more than once, while others can apply only under certain conditions, the task is not easy. The real question that arises is how can we determine and quantify which libraries are more probable than others?

Evaluating grammar-generated libraries

Statistics and frequency analysis are commonly used in archaeology for the mathematical description of data to deduct long-term patterns and regularities in the classification and spatial distribution of archaeological artifacts, as well as to reframe the problem quantitatively (Clarke, Reference Clarke1968; Doran and Hodson, Reference Doran and Hodson1975). Traditional data analysis techniques are used to provide the interpretative framework for the conceptualization of artifacts, while statistical models analyze the actual instances in the class of artifacts to feed back the discussion about its conceptualization, its functional or stylistic differentiation and the impact of time (Read, Reference Read, Whallon and Brown1982, Reference Read and Aldenderfer1987). Read made the distinction between the “ideational” and the “phenomenological” domain, or else between the conceptualization of an artifact versus the actual artifact, or else the class versus the group of objects: class being the sum of parameters that define the shape of the conceptual category of artifacts, while the group being the actual values to the parameters that a known sample of artifacts of the specific category has. The quantitative analysis of the values of the groups of artifacts gives the mean values in each parameter per site. Parameters that have a small standard deviation across sites are considered functional, parameters that have a high variance from site to site are considered stylistic, and parameters that have a high variance in the same site are considered culture-free.

In shape grammars, there is an increasing interest in the use of statistical methods in evaluating the importance of each rule in the definition of style or type. The recent work on the shape grammar of the rural houses of Murcutt's architecture (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Gu and Ostwald2016) utilizes frequency analysis to evaluate the rules used for the generation of the ten known houses, identify the dominant rules, and determine the deviance of the rest of the rules from them. Subsequently, Lee et al. identified rule paths with the rules that apply with the maximum probability each time, creating new instances in Murcutt's rural domestic architecture, and thus exploring further that particular architectural language.

In a very similar way to the analysis of Murcutt's architecture discussed above, the author uses frequency analysis of the rules in the computation of the 17 known libraries to determine which stages occur more often and with which rules, and therefore to deduct which ones are more important in the type definition of a library and to determine the probability with which they will occur in instances or reconstructions for which there is no evidence. Figures 20 and 21 give the histograms of the frequency analysis of the stages and the frequency analysis of the rules within each stage that apply to generate the known 17 libraries. Rules that occur recursively to generate series of objects that do not align with the axes defined by labels, such as niches (rules 22, 23), bookcases (rules 24 and 25), columns (rules 61, 85), or rooms in the back of stoas (rule 86) are considered only once. Also, rules that are denoted with an asterisk (*) and are conjectural, are not considered in the analysis. Table 2 summarizes their hierarchy based on their frequency, ranking them from the most frequent to the least frequent. The rows of the table present the different stages, and the second column presents the rules in each stage, ordered according to their frequency. Parentheses denote rules that occur with the same frequency. The next two paragraphs discuss the results of the frequency analysis.

Fig. 20. Histogram with the occurrence of stages in the derivations of the known libraries.

Fig. 21. Histograms with the occurrence of rules in each stage in the derivations of the known libraries.

Table 2. Stages of the grammar ordered from the mandatory to the least frequent. Each stage includes the corresponding rules ordered according to frequency

The main hall of the library is more likely rectangular rather than apsidal (rules 1 vs. 2). If there is a podium, it is most likely that the podium is continuous (rule 6), along the three walls of the room, and that it supports a colonnade (rule 10). If there is a colonnade, columns are equally likely to be supported on pedestals among which there are steps (rule 15) and to be placed directly on the podium (rule 17), which remains unmodified. Also, a library is most likely to have niches on the walls, which take advantage of the whole wall length (rules 18 and 19), and a focal point. There is a wide variety in the type of the focal point, and all types appear equally frequently, thus making the focal point the most flexible characteristic of the library. Lastly, the main hall of the library is most likely to have a wide entrance with more than one opening (rules 37 and 39), which is equally likely to be articulated with openings among columns (rules 38 and 39) and door openings in the wall (rules 36 and 37).

In terms of the general layout of the library, it is most likely that the library constitutes a symmetric complex (rules 44 and 45). The threshold of the library very often extends beyond the boundaries of the library (rule 54), and this accounts for cases that the library is part of a larger complex, with or without extra rooms. The frequency of rules 61 and 9 expresses the importance of the threshold, and the frequency of rule 59 emphasizes the importance of a peristyle, which occurs as many times as a single stoa and a U-shaped stoa combined (rules 57, 58, and 60). Regarding exedras, the rule that occurs mostly is the rule that erases the label t to stop the computation of exedras, which shows the limited occurrence of exedras in the corpus. In relationship to entrances, the distribution of occurrences shows that there is no consistent way of making a grand entry to the complex. Finally, the limited occurrences in stage 12 reflect the limited building remains that keep most reconstructions of side rooms conjectural.

Rules that occur with zero frequency are rules for which there is no archaeological evidence. Still, they are included in the grammar based on logical assumptions, either because there might be references in literary sources, or because they constitute variations in scale or style of other rules. For example, rules 24 and 25 generate bookcases in the main hall, directly placed on the floor. These rules are necessary in cases of the absence of an architecturally articulated focal point, but there are no remains to verify them. Examples of rules based on stylistic variation are rules 40, 42, and 43 that generate Doric columns, half-columns, and piers, respectively, and are variations of rule 41 that generates Corinthian columns. Finally, an example of rules to account for the change of scale are rules 77 and 78 that generate one and three openings in the courtyard, respectively, and are a variation of rule 79 that generates five openings.

The frequency analysis discussed here generally captures the importance of the rules in the building-type definition of the library. However, it is not very illuminating in the probability of combinations of rule paths one can take that from first sight do not come across as more probable. For example, libraries with a rectangular main hall and continuous podium occur more frequently than libraries with an apsidal main hall and an interrupted podium. Still, all apsidal libraries in the archaeological record were monumental, while two of them had an interrupted podium, and two had a colonnade on pedestals and steps. The association of the apsidal plan of the main hall with the monumental interior design becomes a robust association, which gives the highest probability in reconstructing an apsidal plan as monumental. Finally, we can identify specific rule paths with the lowest probability. They generate hybrid libraries among the ones known, possible within the same language, as defined by the grammar, but unlikely, because they do not occur in the record. For example, there is no library in the record that is apsidal without monumental interior design, or even without a podium.

Conclusions

In defining the architectural form of an ancient building type, the ancient library, shape grammars provide an inclusive methodology that accounts for all variation in the corpus. They visualize the design principles and provide them as guidance in the recursive generation of any library plan that might need to be reconstructed, despite its fragmentary state of preservation.

The library grammar provides a theoretical and constructive description of the ancient library as both an independent building with one hall and a complex. In both cases, the strong emphasis is on the core of the library – the main hall with its architectural elements including the podium, niches, focal point, interior colonnade, entry sequence, and proportional relations encoded in parametric rules. Also, the grammar has been designed to generate main halls of simpler forms, for example, libraries without a podium and interior colonnade, or libraries without niches and focal point but with armaria and a statue set directly on the floor, against the walls of the hall. Thus, the grammar can generate a whole spectrum of libraries, from the most monumental to the simplest. The underlying principle in all of them is the existence of the main hall in association with a colonnaded entrance or stoa.

Aspects of the buildings, which are evident in the archaeological record but cannot be generated by the grammar are stylistic characteristics unique to specific libraries, such as the polyrhythm in the intercolumniations of the façade of the Library of Celsus. Other characteristics of libraries that the grammar does not deal with are case-specific typological characteristics that are the outcome of specific context or functional circumstances, such as the combination of the library with the function of a funerary monument in the Library of Celsus with the introduction of doors in the main hall giving access to corridors that led to the funerary chamber.

The analysis of the metadata of the rules in the grammar and the rules used in the derivations of the known 17libraries addresses the building-type definition of ancient Greek and Roman libraries. It provides us with quantitative data about the building type of the ancient library, about the mandatory, the more probable, and the less probable architectural components in a library. The assumption is that rules that occur more often reflect the design principles at the core of the building typology of the ancient library, while rules that occur less frequently reflect stylistic and case-specific characteristics.

According to the metadata analysis, the building type of the library includes a main hall attached to a threshold, a stoa. Most probably the library includes niches and a focal point, and less often a podium and an interior colonnade. The threshold is one of the most striking features of the library and is the architectural component that organizes the auxiliary spaces of the library if any. At its less common but most monumental form, the library is a whole complex that includes semicircular and rectangular exedras, a monumental propylon and additional rooms that function as auditoria, banquet halls, or offices.

To make the most out of the grammar and its analysis, we need to keep in mind its limitations. We cannot deny that the set of architectural components that occur in a library do not occur in other building types of classical architecture, such as gymnasia and stoas, but this cannot exclude the definition of a building type for the ancient library, according to which specific architectural features are mandatory, some others are most likely, and others are less likely to occur in a library. Also, we need to keep in mind that the library grammar encodes the design principles of ancient libraries as derived from the current archaeological record along with our objectivity in its interpretation. Future discoveries in the field will ask for a review of the grammar to incorporate changes in our understanding of ancient libraries. New evidence will add more instances to the metadata of specific rules, and the derivations of the newly found instances might change the frequency in the occurrence of rules and therefore, the probability of certain features. For example, if we identify new libraries in monumental complexes in the future, the exedras that now appear as less programmatic features will become more probable features in the building type of the ancient library. Still, this model of probabilities is a systematic guide in identifying, evaluating, and predicting the architectural form of ancient libraries and reconstructing them despite their diverse scale and monumentality.

The library grammar provides a combinatorial problem, where enumerating all combinations is not straightforward. A matrix of possibilities with the simple multiplication of the different possibilities within each stage is not enough, as some rules are optional and others apply more than once. An advanced mathematical model for a rule path analysis is needed to identify the rule subsets that are more likely to occur and to calculate the number of different possibilities. The frequency analysis needs not to be limited only to each rule separately, but to be extended to subsets of rules. A tree of rule paths with the corresponding probability of each of them can help us conclude to the ones that are more important in the building type of the library and more likely to capture the original design in any given partially preserved library that requires reconstruction. Most importantly, the computer implementation of the grammar in Shape Machine is expected to revolutionize the way we enumerate and understand iterations and automatically generated variations.

Myrsini Mamoli, BA, MSc, PhD is a digital scholar and architectural historian with a specialization on the use of analytical and formal methods for the analysis and reconstruction of historical architectural designs. I hold a PhD in Architecture with major in computation and minor in architectural history (GATECH), an MSc in Cultural Technology and Digital Media (University of the Aegean, Greece), and a BA in Archaeology and Art History (Aristotle University, Greece). Previously, she was a tenure-track Assistant Professor of Art History at LSU, a position she had to leave to return to Greece as mandated by the terms of her Fulbright scholarship. Currently she is a visiting scholar at Georgia Tech, exploring at a bigger breadth the efficacy of digital technologies in the analysis, reconstruction and presentation of archaeological and cultural artifacts.

Her training is at its core interdisciplinary, bridging the fields of museum studies, anthropology, archaeology, art history, architectural history, digital humanities, and computational media. More specifically, my teaching and research interests and experience lie at the intersection of architectural history and computation. The key driver of her teaching and research lies on the exploration of the ways technology and computation shed new light upon historical analysis of the architecture and design of historical artifacts: Three-dimensional modeling, generative grammars, immersive and interactive digital environments with game engines, databases, are the technologies and methodologies she employed complementarily to traditional historical research for the analysis, interpretation and reconstruction of architectural building remains.

Her area of expertise is classical Greek and Roman art and architecture with a particular research focus on the architecture of the ancient library, a prominent civic institution that appeared and developed in ancient Greece and became further widespread in the Roman Empire. In addition to its history, she has studied its architectural form, and she has analyzed it developing a rule-based visual system, a shape-grammar, for the reconstruction of different fragments in variant ways, given the constraints of the archaeological evidence. Her work on ancient libraries received the Faculty Award of Merit for the best PhD dissertation at Georgia Tech, has been published in several peer-reviewed conference proceedings, and at the Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Engineering, Design, Analysis, and Manufacturing.

Currently, she is working on implementing analogue archaeological analysis on rule-based visual systems with the new-cutting-edge software Shape Machine, developed by the Shape Computation Lab at Georgia Tech, that computes shapes and not symbols, in order to explore the variation in reconstruction, as it is constrained by the archaeological evidence.