Introduction

Organizations try to retain a thriving workforce which feels energized and alive (vitality) and able to grow and develop (learning) (Prem, Ohly, Kubicek, & Korunka, Reference Prem, Ohly, Kubicek and Korunka2017) in order to stay competitive. The topic of thriving at work is important because organizations can thus alleviate problems such as absenteeism resulting from burnout, disengagement, depression, and other illnesses (Porath, Spreitzer, Gibson, & Garnett, Reference Porath, Spreitzer, Gibson and Garnett2012) and improve performance, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and employee innovation (Gerbasi, Porath, Parker, Spreitzer, & Cross, Reference Gerbasi, Porath, Parker, Spreitzer and Cross2015; Parker, Gerbasi, & Porath, Reference Parker, Gerbasi and Porath2013; Paterson, Luthans, & Jeung, Reference Paterson, Luthans and Jeung2014). Commonly perceived as ‘the psychological state in which individuals experience both a sense of vitality and a sense of learning at work’ (Spreitzer, Sutcliffe, Dutton, Sonenshein, & Grant, Reference Spreitzer, Sutcliffe, Dutton, Sonenshein and Grant2005: 538), thriving is not a personality disposition (Spreitzer, Lam, & Fritz, Reference Spreitzer, Lam, Fritz, Bakker and Bakker2010), but rather a psychological state, which can be crafted by the work context and job design (Wrzesniewski, LoBuglio, & Dutton, Reference Wrzesniewski, LoBuglio, Dutton and Bakker2013). According to Spreitzer et al. (Reference Spreitzer, Sutcliffe, Dutton, Sonenshein and Grant2005), thriving at work depends on certain individual characteristics (e.g., knowledge), interpersonal characteristics (e.g., support), contextual features (e.g., job autonomy), and agentic work behaviors (e.g., task focus and exploration). Agentic work behaviors overlap with the definition of job crafting (JC).

Recently, JC has emerged in human resource management literature (Berg, Dutton, & Wrzesniewski, Reference Berg, Dutton, Wrzesniewski, Dik, Byrne and Steger2013; Nielsen, Reference Nielsen2013) and in the management field (Evans & Holmes, Reference Evans and Holmes2013). This concept refers to the self-initiated changes employees make to redesign their job by increasing their job resources and challenges and decreasing the job demands (Tims & Bakker, Reference Tims and Bakker2010). Thriving at work can be associated with increasing resources and challenges, as job resources stimulate personal growth, learning, and development (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007: 312) and cultivate energy.

Although the concept of ‘thriving at work’ seems relevant, research ‘has been quite sparse’ (Niessen, Sonnentag, & Sach, Reference Niessen, Sonnentag and Sach2012: 468) and the predictors are not well understood (Niessen, Sonnentag, & Sach, Reference Niessen, Sonnentag and Sach2012). Although research reveals that JC has positive effects on job satisfaction, work engagement, and well-being (e.g., meta-analysis of Rudolph, Katz, Lavigne, and Zacher, Reference Rudolph, Katz, Lavigne and Zacher2017), it is unclear whether this would also hold for other work outcomes such as thriving at work. This paper examines the effects of JC strategies on thriving at work.

Whether or not employees proactively craft their job may depend on boundary conditions like job resources and perceived opportunity to craft (POC) (van Wingerden & Niks, Reference van Wingerden and Niks2017; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Reference Wrzesniewski and Dutton2001). Although the opportunity to craft employees' job is an important issue, researchers have paid little attention to this topic (van Wingerden & Niks, Reference van Wingerden and Niks2017). These authors indicate that future research must examine various boundary conditions that facilitate/mitigate JC. Also, van Wingerden and Niks (Reference van Wingerden and Niks2017) advance that the POC itself may directly affect work attitudes. Hence, this study investigates whether the POC may influence directly JC strategies and whether these can increase thriving at work. It also aims to examine the indirect effect of POC on thriving at work via JC.

Researchers have investigated the positive side of JC and have aggregated all dimensions of JC into one construct, analyzing its antecedents and outcomes, leading to inconsistent results. Rudolph et al. (Reference Rudolph, Katz, Lavigne and Zacher2017) call for unpacking the black box: ‘a more complete “unpacking” of the adaptive and counterproductive implications of decreasing hindering job demands is warranted’ (p. 132). This research fulfills this gap by focusing on the positive as well as the negative sides of JC.

Although research on JC has been conducted in professions like hospitality (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Yen and Tsai2014), healthcare (Gordon, Demerouti, Le Blanc, & Bipp, Reference Gordon, Demerouti, Le Blanc and Bipp2015), education (Leana, Appelbaum, & Shevchuk, Reference Leana, Appelbaum and Shevchuk2009), administration (Bell & Njoli, Reference Bell and Njoli2016), mining, and manufacturing (De Beer et al., Reference De Beer, Tims and Bakker2016), this study focused on accounting professionals (CPAs), which can bring a novel contribution. Byrne and Pierce (Reference Byrne and Pierce2007) indicated that management accountants generally want broader role contents and are active in designing or developing their work. Also, they ‘may change the task and relational boundaries of their work in order to better fit their identities’ (Horton & de Wanderley, Reference Horton and de Wanderley2018).

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Job crafting

JC is a concept which stems mainly from two distinct theoretical currents (Zhang and Parker (Reference Zhang and Parker2018). In 2001, Wrzesniewski and Dutton introduced the concept by focusing on the nature of the changes made to the boundaries of work, that is, changes in tasks, relational or cognitive, as part of a vision focusing on the meaning given to work. Later, Tims and Bakker (Reference Tims and Bakker2010) conceptualized JC in terms of the job demands-resources (JD-R) model (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2016) as a theoretically significant mechanism to explain the relationship between characteristics of work and work outcomes. JC is defined as ‘the changes employees make to balance their job demands and job resources with their personal abilities and needs’ (Tims et al., Reference Tims, Bakker and Derks2012: 174).

In a recent meta-analysis, Zhang and Parker (Reference Zhang and Parker2018) synthesized these two theoretical currents into a typology based on the orientation, form and content of JC. The orientation relates to the general attitude of employees toward JC. Indeed, they will engage either in a proactive logic of promotion aiming to make certain things happen, or of prevention, aiming to prevent certain things from happening (Parker, Bindl and Strauss, Reference Parker, Bindl and Strauss2010). We thus speak of JC according to a logic of ‘approach,’ aimed at increasing certain resources or demands at work, or a logic of ‘avoidance,’ aiming to reduce them (Bruning and Campion, Reference Bruning and Campion2018). The precise form of JC concerns the behavioral (tasks and relations) or cognitive aspects (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Reference Wrzesniewski and Dutton2001). Finally, the content of JC determines whether the employee acts upon a demand or a resource associated with work.

The JD-R model constitutes a complete theoretical framework for understanding how job design components enhance meaningfulness and stimulate occupational well-being, engagement, and work performance (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Katz, Lavigne and Zacher2017). It has inspired empirical research over the past decade. This is why we retain the conceptualization of Tims and Bakker in our research. Indeed, Tims and her team (Reference Tims, Bakker and Derks2012) have distinguished four possible strategies of JC: increasing social resources (e.g., asking a colleague for advice), increasing structural resources (e.g., learning new things at work), increasing challenges (e.g., offering oneself proactively when a new project is announced), and decreasing hindering demands (e.g., organizing oneself to don't have to focus too long). Following this logic, eight types of JC emerge, representing all of the possible combinations between the forms, content, and possible orientations of the JC (see Zhang and Parker, Reference Zhang and Parker2018). JC is therefore a multidimensional concept, and it is important to distinguish the approach logic from the avoidance logic. Indeed, these two orientations result from different dynamics and seem to have almost opposite effects on well-being and performance at work.

POC as a precondition to JC

Van Wingerden and Niks defined POC as employees' perceptions regarding opportunities to craft their work (van Wingerden & Niks, Reference van Wingerden and Niks2017: 2). POC is seen as psychologically positive because it involves autonomy and sense of gain. It can be defined as ‘the sense of freedom or discretion employees have in what they do in their job and how they do it’ (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Reference Wrzesniewski and Dutton2001: 183); task interdependence and freedom to craft are thus preconditions to POC. Also, management and supervisors play a key role in offering an opportunity to craft or not. Accordingly, employees tend to evaluate the opportunity to craft before they engage in JC behaviors; POC can thus hinder or facilitate possibilities for JC (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Reference Wrzesniewski and Dutton2001). Although research showed that job characteristics were associated with JC behavior, the results are mitigated. Although several researchers revealed that job resources such as perceived autonomy support and a leadership style were a predictor of JC behavior (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Demerouti, Le Blanc and Bipp2015; Petrou, Demerouti, Peeters, Schaufeli, & Hetland, Reference Petrou, Demerouti, Peeters, Schaufeli and Hetland2012; Slemp et al., Reference Slemp, Kern and Vella-Brodrick2015), others found that job autonomy and task interdependence did not predict an increase in JC (Niessen et al., Reference Niessen, Weseler and Kostova2016). It thus appears that the relationship between job characteristics and JC is complex and dynamic.

van Wingerden, Derks, Bakker, and Dorenbosch (Reference van Wingerden, Derks, Bakker and Dorenbosch2013) revealed that employees did not engage in JC because they did not perceive opportunities for this and felt that their jobs were controlled by managers, organizations, contrarily to colleagues who stated that they changed aspects of their work due to their POC (van Wingerden et al., Reference van Wingerden, Derks, Bakker and Dorenbosch2013 as reported by van Wingerden & Niks, Reference van Wingerden and Niks2017). Berg, Grant, and Johnson (Reference Berg, Grant and Johnson2010) showed that employees are sometimes required to shape expectations of their supervisors in order to engage in JC: one respondent ‘feels that her supervisor's expectations of their relationship limit her power to get her supervisor to accommodate her job crafting intentions’ (Berg, Grant, & Johnson, Reference Berg, Grant and Johnson2010: 170). van Wingerden and Niks (Reference van Wingerden and Niks2017) found that job resources (autonomy and opportunities for professional development) predicted POC.

This study suggests that a high level of POC, which implies a high level of autonomy, leads to an increase in social and structural resources and to enhance challenging job demands. In contrast, it is expected that the POC might lead to reduce employees' intention to decrease hindering job demands. Indeed, Hobfoll's resource conservation theory (COR) (1989, 1998) helps to understand how POC influences JC. Indeed, Hobfoll's conservation of Resources theory (COR) (Reference Hobfoll1998: 82) states that ‘those who possess resources are more inclined to gain new ones and that initial gains lead to future gains.’ Thus, when the level of POC is high, employees try to acquire new social resources (e.g., ask others for feedback on their performance) and structural (e.g., develop professionally) and to increase challenges to work (e.g., take new tasks or a new project), which in turn would lead to improving their well-being. As for the loss spiral, Hobfoll (1998: 81) indicates that ‘those lacking resources are not only fragile in the face of loss of resources, but the initial loss leads to future losses.’ As a result, in the face of this loss of resources, employees adopt defensive strategies, causing them to protect their resources at work to avoid future losses. Such strategies can lead to dysfunctional results such as the intention to leave (Mansour & Tremblay, Reference Mansour and Tremblay2016). Research indicated that employees use a strategy of self-protection (decreasing hindering job demands) when they experience uncontrollable demands. For instance, when employees face a high workload, they try to decrease hindering demands and to seek resources that help them manage these excessive demands (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017). In other words, when job demands are perceived as devastating and cost-oriented, employees try to reduce them proactively (e.g., organize work so that they don't have to focus too long) (Tims et al., 2012). However, although many work characteristics (e.g., job autonomy, job resources, and leadership) predicted positively proactive JC behaviors, Zhang and Parker (Reference Zhang and Parker2018) in a meta-analysis considered decreasing hindering job demands as a less proactive behavior, which is also related to job characteristics but in the opposite direction. In another meta-analysis, Rudolph et al. (Reference Rudolph, Katz, Lavigne and Zacher2017) found that job autonomy influenced negatively avoidance hindering demands. We believe that employees may fear stigma or feel that their resources are at risk (e.g., career advancement, development, learning opportunity, etc.) if they reduce certain job tasks. For instance, some authors indicated that decreasing job demands can cause conflicts among coworkers (Tims, Bakker, & Derks, Reference Tims, Bakker and Derks2015b).Therefore, as POC involves autonomy and control over what one does and how one does it (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Reference Wrzesniewski and Dutton2001), it seems that it can enhance employees' goal-oriented behaviors and prevent avoidance demands and withdrawal behaviors (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007). Thus:

Hypothesis 1: POC is positively related to increasing structural resources (1a); increasing social resources (1b), increasing challenging job demands (1c), and negatively to decreasing hindering demands (1d).

Thriving at work

Spreitzer et al. (Reference Spreitzer, Sutcliffe, Dutton, Sonenshein and Grant2005) examined two mechanisms of thriving at work (learning and vitality). Learning can be defined as individuals' perceptions of constantly cultivating their expertise, talents, and capabilities in their job (Elliott & Dweck, Reference Elliott and Dweck1988); vitality means that one feels energized and alive when doing one's job (Nix, Ryan, Manly, & Deci, Reference Nix, Ryan, Manly and Deci1999). As thriving at work includes learning, it has been empirically distinguished from flourishing and core self-evaluation (Porath et al., Reference Porath, Spreitzer, Gibson and Garnett2012) and from engagement (Spreitzer, Lam, & Fritz, Reference Spreitzer, Lam, Fritz, Bakker and Bakker2010).

JC and thriving at work

Spreitzer et al. (Reference Spreitzer, Sutcliffe, Dutton, Sonenshein and Grant2005) observed that ‘individuals might find ways to craft their jobs’ and (…) ‘can become more active agents in shaping the contexts that enable their thriving’ (Spreitzer et al., Reference Spreitzer, Sutcliffe, Dutton, Sonenshein and Grant2005: 545). Indeed, according to the COR theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll1998, Reference Hobfoll1989), the more an employee has resources, the more he is in a good position to acquire more resources to protect himself and the more he is ready to invest resources at work. Therefore, having more resources via JC behaviors (e.g., increasing social and structural resources), employees may invest resources obtained to gain more resources (in the form of learning and development) and become thus more energized at work (via vitality). For instance, approach crafting improves employees' career, as employees become able to enhance their personal resources through more learning opportunities or to transform already existing resources into other valuable assets (Kira, van Eijnatten, & Balkin, Reference Kira, van Eijnatten and Balkin2010). However, employees who enhance their job's challenges can cultivate their knowledge and attain more challenging ambitions (LePine, Podsakoff, & LePine, Reference LePine, Podsakoff and LePine2005). Increasing challenges at work may increase personal growth, development and learning, enhance the level of functioning and self-efficacy at work, and increase motivation, performance, and engagement.

Job demands can be defined as ‘physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical and/or psychological (cognitive and emotional) effort or skills and are therefore associated with certain physiological and/or psychological costs’ (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007: 312). If hindering job demands are perceived as devastating and imply costs, employees may proactively reduce them (Tims et al., Reference Tims, Bakker and Derks2012). However, the effect of this JC strategy on work outcomes is inconsistent and at best weak and negative (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Katz, Lavigne and Zacher2017). Demerouti et al. (Reference Demerouti, Bakker and Halbesleben2015) revealed that decreasing hindering job demands can lead to negative outcomes (e.g., reduced engagement and task performance). Therefore:

Hypothesis 2: Increasing structural resources (2a); increasing social resources (2b); and increasing challenging job demands (2c) are positively related, whereas decreasing hindering demands (2d) is negatively related to thriving at work (vitality).

Hypothesis 3: Increasing structural resources (3a); increasing social resources (3b); and increasing challenging job demands (3c) are positively related, whereas decreasing hindering demands (3d) is negatively related to thriving at work (learning).

Mediating role of JC between POC and thriving

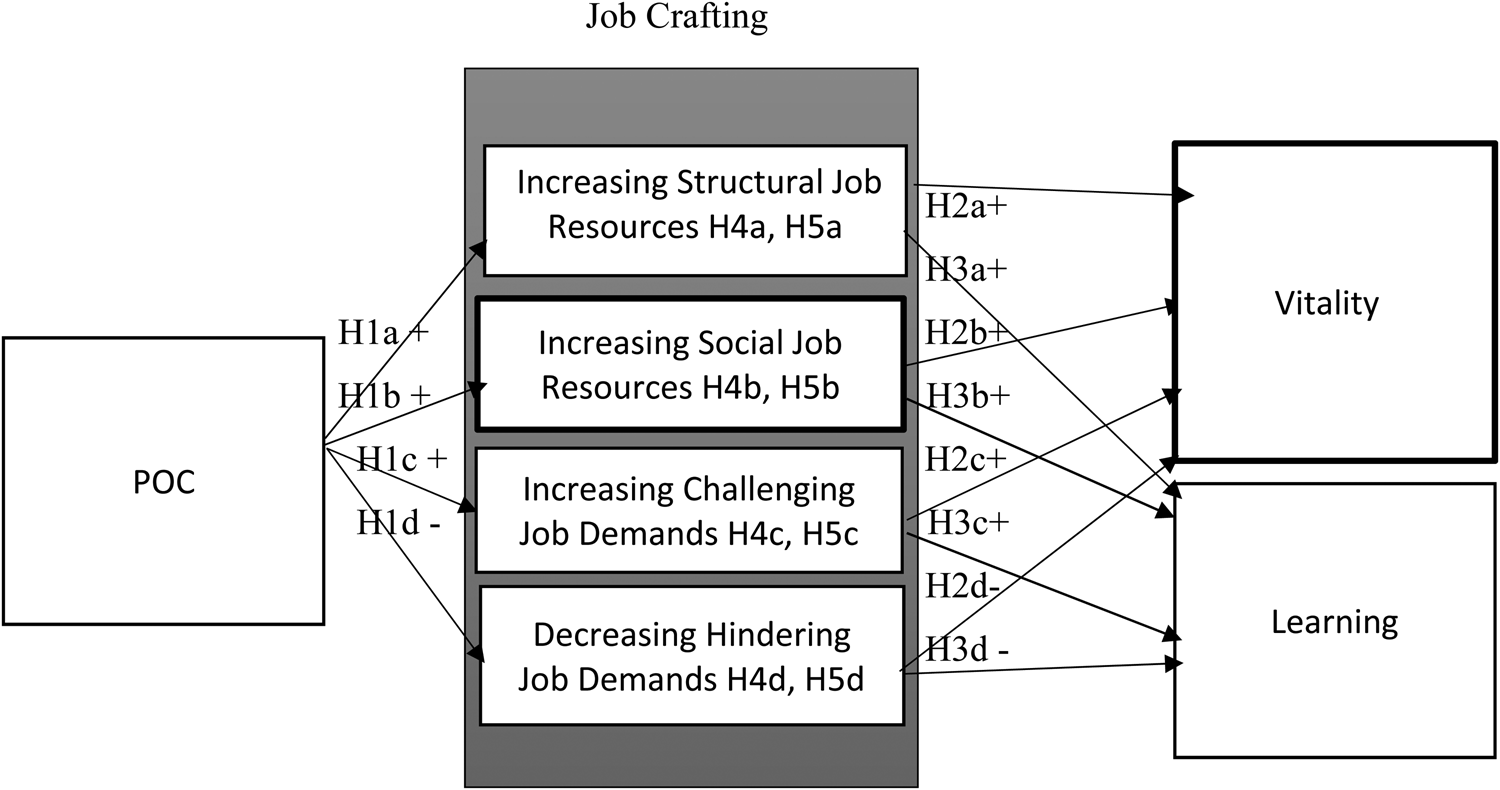

The theoretical model suggests that JC behaviors act as a mechanism through which POC enhances thriving at work, both vitality and learning. When the level of POC is high, employees try to balance their job demands and job resources to align their work environment with their personal abilities, preferences, and needs (Tims et al., Reference Tims, Bakker and Derks2012) and to better use their capabilities and experience meaning at work (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Reference Wrzesniewski and Dutton2001). Increasing their pool of resources via JC behaviors leads to an increase in thriving at work as job resources stimulate personal growth, learning, and development (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007: 312). The mediation mechanism which links POC, JC, and thriving at work can be explained by the COR theory (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2011, Reference Hobfoll2012). Hobfoll (Reference Hobfoll2011) extended COR theory by developing the concept of ‘resource caravan passageways,’ which are ‘environmental conditions that support, foster, enrich, and protect the resources of individuals, sections or segments of workers, and organizations in total, or that detract, undermine, obstruct, or impoverish people's or group's resource reservoirs’ (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2011: 129). Resources are often beyond individuals’ control (Hobfoll & Dejong, Reference Hobfoll, De Jong, Zoellner and Feeny2013) and are rarely found alone but rather present themselves in packs or aggregates (Hobfoll, Reference Hobfoll2011). This means that the presence of one resource entails the presence of others, and increases their efficiency. Thus, as the COR theory stipulates, POC may act as a passageway allowing employees to enrich, protect or even gain new resources (by increasing their social and structural resources as mentioned before) leading them to a better state of mind (feeling energized and able to learn and develop). This study suggests that JC mediates the relation between POC and thriving at work. More precisely, when the level of POC is high, employees try to acquire new social resources (e.g., ask colleagues for advice) and new structural resources (e.g., learn new things at work) which in turn would lead to improving their sense of vitality and learning. POC thus influences thriving at work via increasing social and structural resources. In the same vein, POC can play a role of passageway by allowing employees to increase challenges (e.g., by starting a new project), which in turn may increase personal growth, development, and learning., POC can thus increase thriving at work via increasing challenging demands. Also, when employees feel that POC is high, this can give them a sense of autonomy and control they need to manage their workload, decreasing thus their intention to decrease hindering demands. Fig. 1 present our conceptual model.

Hypothesis 4: The effect of POC on vitality is mediated positively by increasing structural resources (4a); increasing social resources (4b) and increasing challenging job demands (4c), and negatively by decreasing hindering demands (4d).

Hypothesis 5: The effect of POC on learning is mediated positively by increasing structural resources (5a); increasing social resources (5b) and increasing challenging job demands (5c), and negatively by decreasing hindering demands (5d).

Fig. 1. Conceptual model.

Methods

Sample

This research was conducted in partnership with the association of CPAs of the province of Québec (Canada) and there were 424 respondents. The questionnaire was sent to participants online via an information letter. In the sample, 136 were males (32.1%) and 288 were females (67.9%). The participants had different ages: ‘less than 20 years’ (n = 1, .2%), ‘21–30 years’ (n = 21, 5%), ‘31–40 years’ (n = 153, 36.1%), ‘41–50 years’ (n = 143, 33.7%), ‘50–60 years’ (n = 88, 20.8%), and ‘more than 60 years’ (n = 18, 4.2%).

Participants were in organizations of various sizes: 88 in organizations from 1 to 50 employees, 147 in organizations from 51 to 500 employees, and 189 in organizations of more than 500 employees. Also, 166 participants were working in public administration/Parapublic agencies/Crown corporations and 258 in industry/private company/accounting firms. Finally, 174 were chief financial officer (CFO)/director/vice-president/partners/top managers, 58 were controller/assistant or controller/auditor, 76 were agent/analyst and 116 were accountant.

Measures

Perceived opportunity to craft

The scale by van Wingerden and Niks (Reference van Wingerden and Niks2017) was used to measure POC (5 items). An example of an item is ‘at work I have the opportunity to vary the type of tasks I carry out’ (POC, 5 items, Cronbach's α = .864). Responses were on a 7-point frequency scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree).

Job crafting

For JC, the scale developed by Tims et al. (Reference Tims, Bakker and Derks2012), which is composed of increasing challenges and decreasing hindering job demands, as well as increasing structural and social job resources was used. For example: ‘I try to develop my capabilities’ (increasing structural job resources, 5 items, Cronbach's α = .90), ‘I ask my supervisor to coach me’ (increasing social job resources, 5 items, Cronbach's α = .77), ‘when there is not much to do at work, I see it as a chance to start new projects’ (increasing challenging job demands, 5 items, Cronbach's α = .70), and ‘I make sure that my work is mentally less intense’ (decreasing hindering job demands, 6 items, Cronbach's α = .64). The scale ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (very often).

Thriving at work

For thriving at work, the scale of Porath et al., (Reference Porath, Spreitzer, Gibson and Garnett2012) was used. For example: ‘I find myself learning often’ (learning, 5 items, Cronbach's α = .84) and ‘I feel alive and vital’ (vitality, 5 items, Cronbach's α = .87). The responses were from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Table 1 displays the means and standard deviations observed as well as corrected correlations, reliabilities, and validity for all variables. POC was positively related to all other concepts except for decreasing hindering job demands, which was not significant. Also, increasing social and structural resources and increasing challenging demands were positively associated with thriving at work, both vitality and learning, whereas decreasing hindering demands was unrelated. Concerning control variables, only gender is positively correlated on increasing structural and social resources and on learning.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations

Note: Employer was coded 1 for public and 2 for private. Number of employees was coded 1 from 1 to 50, 2 from 51 to 500, and 3 for 501 and more. Position was coded 1 for CFO, 2 for controller, 3 for accountant, and 4 for other positions. Sex was coded 1 for men and 2 for women.

*p < 05, **p > 01

Analysis

In order to confirm the structure of constructs and the reliability and validity of the measurement scales, confirmatory factor analyses were carried out by the method of maximum likelihood using AMOS 24. To measure the quality of adjustment of scales for the data, indexes such as CFI, TLI, SRMR, RMSEA, PClose, and chi-square/df were retained. The cutoff criteria are presented in Table 2 for each index. For example, for CFI and TLI, a value of ≥.95 is presently recognized as indicative of good fit and an SRMR of less than .08 is acceptable (Hu and Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). Factor loading should be more than .70. One item, related to decreasing hindering demands (I organize my work so that I don't have to concentrate for too long), was dropped because it had a loading of less than .70 (the acceptable value). As shown in Table 2, we compared six models. First, model 1 with seven factors, where each dimension is considered as a latent variable. Second, model 2 with five factors, where all positive JC behaviors, that is increasing social and structural resources and increasing challenges load onto one factor and decreasing hindering job demands on another factor, POC and vitality and learning as distinctive constructs. Third, model 3 with four factors, where all dimensions of JC load onto one factor, POC, vitality and learning. Fourth, model 4 with three factors, where all four dimensions of JC are grouped together, the two dimensions of thriving are loaded onto one factor and the POC. Fifth, model 5 with two factors, where all dimensions of JC and POC are loaded into one factor and thriving at work (two dimensions load together). Finally, model 6 with one factor where all dimensions are loading onto one factor.

Table 2. Comparison of models fit

As expected, the results shown in Table 2 indicate that the 7-factor model fits data adequately (χ 2/df = 480.912/229 = 2.1, CFI = .96, SRMR = .05, RMSEA = .05, PClose = .39, TLI = .96), and significantly better than any alternative models (e.g., the five-factor model [χ 2/df = 4.37, CFI = .84, SRMR = .09, RMSEA = .09, PClose = .00, TLI = .81]). This suggests that one should consider these 7 factors as separate variables.

To measure convergent validity, the AVEFootnote 1 for each construct was calculated; values above .5 mean a good convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). Also, all factor loadings vary between .70 and .90 and all loading factors are significant as Student's t varies between 9.29 and 16.175. Discriminant validity is established when MSVFootnote 2 is lower than the AVE for all the constructs (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Reference Hair, Black, Babin and Anderson2010). Table 3 shows a satisfactory convergent validity for all constructs of our model as its value varies between .54 and .75. Discriminant validity is also verified as MSV is lower than the AVE for all constructs (it varies between .01 and .25).

Table 3. Reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity

CR, reliability; AVE, convergent validity; MSV, discriminant validity.

Structural model

As our study looked at perceptions of employees on behavioral variables measured at one point in time and responses were self-reported, there might be a bias of the common method variance (CMV). Podsakoff et al. (2003) have suggested four preventive methods to diminish the CMV bias, including (1) adding reverse items in the survey, (2) randomly organizing items, (3) concealing the purpose of the research, and (4) concealing the relationship between questions. Our questionnaire was formulated on the basis of these suggestions. Also, the assurance of anonymity and confidentiality was provided (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2012). In addition, using Harman's one-factor test (Podsakoff & Organ, Reference Podsakoff and Organ1986), all items related to JC, POC, and thriving at work were subjected to an exploratory factor analysis. Results revealed that common method bias was not a major issue, as the test reveals that the newly introduced common latent factor explains 26% of the variance, which is less than 50% (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Secondly, as mentioned above, CFA was employed to test the effect of CMV (Stam & Elfring, Reference Stam and Elfring2008). The seven-factor model involving all dimensions as separate variables demonstrated fairly better fit to the data compared with one factor. Thirdly, an unmeasured latent method factor was controlled, and all self-reported items were allowed to load both on their theoretical constructs and on the method factor (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). The results for all structural path parameters remained the same after controlling for the method factor, suggesting that CMV did not bias our findings.

Results

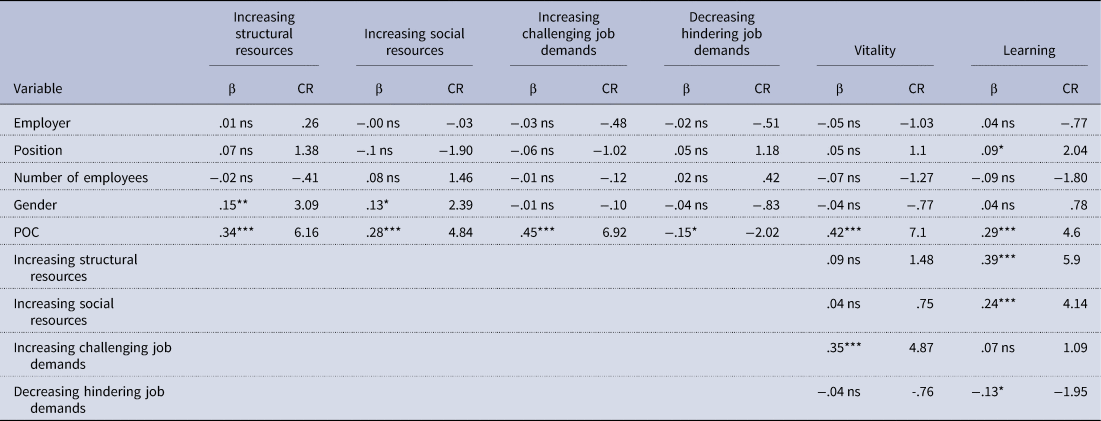

The hypotheses were verified using structural equation modeling with AMOS 24. Employer (public vs. private), organization size, position, and gender were introduced as control variables in the model. Tables 4 and 5 display the results of these tests of directional and mediational model respectively. As for model fit, the results show that the mediational model fits data adequately (χ 2/df = 1.95, CFI = .96, SRMR = .05, RMSEA = .04, PClose = .76, TLI = .96), and better than a directional model (χ 2/df = 2.06, CFI = .94, SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .05, PClose = .49, TLI = .92).

Table 4. Standardized direct effects of POC on JC and of JC on vitality and learning

*Significant p < .05; **significant p < .01; ***significant p < .001.

Table 5. Standardized indirect effects

*Significant p < .05; **significant p < .01; ***significant p < .001.

Direct effects

As predicted in hypotheses 1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d, POC was positively related to increasing structural resources (β = .34, p < .001), increasing social resources (β = .28, p < .001), increasing challenging job demands (β = .45, p < .001), and negatively related to decreasing hindering job demands (β = −.1, p < .05). This means that hypotheses 1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d were supported. Contrarily to what was suggested in hypotheses 2a and 2b, increasing structural resources and increasing social resources were not related to vitality (β = .09, p > .05 and β = .04, p > .05 respectively). As suggested in hypothesis 2c, an increase in challenging job demands was positively related to vitality (β = .35, p < .001). Contrarily to hypothesis 2d, a decrease in hindering job demands was not negatively related to vitality (β = −.04, p > .05). Hypotheses 2a, 2b, and 2d were not confirmed, whereas hypothesis 2c was verified.

As proposed in hypotheses 3a, 3b, and 3d, increasing structural resources and increasing social resources were positively associated with learning (β = .39, p < .001 and β = .24, p < .001, respectively) and decreasing hindering job demands was negatively associated with learning (β = −.1, p < .05). Unexpectedly, increasing challenging job demands were not linked to learning (β = −.07, p > .05) contrarily to hypothesis 3c. These results mean that hypotheses 3a, 3b, and 3d were supported, whereas hypothesis 3c was rejected. POC explains 3% of decreasing hindering demands, 20% of increasing challenging job demands, 14% of increasing structural resources, and 13% of increasing social resources. Also, JC explains 18% of vitality and 32% of learning. Finally, we can note that the direct effects of POC on thriving, on both vitality and learning, when controlling for JC dimensions, are positive and significant (β = .42, p < .001, β = .29, p < .001, respectively).

Indirect effects

The analysis of mediation process was performed using a bootstrap analysis (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2004). This method overcomes the limits of the approach of Baron and Kenny (Reference Baron and Kenny1986), traditionally used in the analysis of mediation and in particular the statistical power problem (Edwards & Lambert, Reference Edwards and Lambert2007) and the decrease in type I error (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008). The method of Monte Carlo (parametric bootstrap) and more precisely bias corrected percentile method (Efron, Reference Efron1987) was used. The analyses with AMOS v.24 are based on 2000 replications generated by the bootstrap method with a 95% confidence interval.

The results of bootstrap indicate that the indirect effect of POC on vitality through increasing structural resources, increasing social resources, and increasing challenging job demands is positive and significant (β = .094, SE = .03, 95% CI = [.05, .15]; β = .054, SE = .02, 95% CI = [.02, .11]; β = .21, SE = .05, 95% CI = [.12, .33], respectively). Thus, hypotheses 4a, 4b, and 4c are supported; POC increases vitality by increasing structural and social resources and increasing challenging job demands.

The results also reveal that the indirect influence of POC on learning via increasing structural resources, increasing social resources and increasing challenging job demands is positive and significant (β = .17, SE = .03, 95% CI = [.11, .24]; β = .11, SE = .03, 95% CI = [.05, .17]; β = .18, SE = .05, 95% CI = [.1, .3], respectively). Hypotheses 5a, 5b, and 5c are supported; POC increases vitality by increasing structural and social resources and increasing challenging job demands. On the contrary, results show that the indirect effect of POC on vitality and learning through decreasing hindering job demands is not significant (β = .01, SE = .01, 95% CI = [−.00, −.03]; β = .01, SE = .01, 95% CI = [−.01, −.04], respectively). Hypotheses 4d and 5d are rejected; POC does not decrease vitality and learning by decreasing hindering job demands.

The results reveal that the indirect influence of POC on learning via increasing structural resources, increasing social resources and increasing challenging job demands is positive and significant (β = .17, SE = .03, 95% CI = [.11, .24]; β = .11, SE = .03, 95% CI = [.05, .17]; β = .18, SE = .05, 95% CI = [.1, .3], respectively). Hypotheses 5a, 5b, and 5c are thus supported; POC increases vitality by increasing structural and social resources and increasing challenging job demands. However, results show that the indirect effect of POC on vitality and learning through decreasing hindering job demands is not significant (β = .01, SE = .01, 95% CI = [−.00, −.03]; β = .01, SE = .01, 95% CI = [−.01, −.04], respectively). Hypotheses 4d and 5d are rejected; POC does not decrease vitality and learning by decreasing hindering job demands.

Discussion

The findings suggest that the more organizations provide opportunity to craft one's job, the more employees try to increase structural job resources, social job resources, and challenging job demands and the less they try to decrease hindering job demands. Indeed, employees in our study find in POC a ‘green light’ to redesign their job via increasing structural and social resources and increasing challenging job demands to fit their needs, competences, and goals. However, the results reveal that POC is negatively related to decreasing hindering job demands. It seems that accountants are motivated and seek to accumulate resources to grow and develop rather than use avoidance and disengaging behaviors such as decreasing hindering job demands. It appears that in organizations where the level of opportunity to redesign one's job is high, employees find more autonomy and control on job demands associated with high levels of challenging workload. They thus seek to increase resources and challenges as an effective strategy rather than try to decrease hindering demands (Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Csikszentmihalyi1990).

Contrary to what was suggested, increasing structural resources and social resources and decreasing hindering job demands were not related to thriving at work (vitality). Also, the results indicated that the more employees seek increasing challenging job demands, the more thriving (vital and alive) they are in their work. A possible explanation for not finding positive effects of increasing structural and social resources on vitality could lie in the fact that vitality may increase primarily because of motivating consequences of increasing challenging job demands.

Decreasing hindering job demands could contribute to reducing these energizing effects (feeling vital and alive). Indeed, although seeking challenges leads to accumulate challenges that further motivate employees and energize them, decreasing stressors, by removing those challenges, leads to less stimulation and motivation of employees (Petrou et al., Reference Petrou, Demerouti, Peeters, Schaufeli and Hetland2012). Consequently, the level of vitality could diminish and reach near zero when individuals try to increase structural and social resources, which requires investing more time and energy. These results confirm the positive as well as the negative side of JC strategies (Oldham & Hackman, Reference Oldham and Hackman2010). Another explanation of these findings lies in the fact that a model with multiple dimensions of JC having positive as well as negative effects on thriving at work was tested, and paths could have cancelled each other out as in the case of ‘inconsistent or suppressor mediation’ (for more details, see MacKinnon et al. Reference MacKinnon, Krull and Lockwood2000), causing the non-significant effects of increasing structural and social resources on vitality. This also can explain the absence of a mediating role of decreasing job demands between POC and both vitality and learning, whereas POC has an indirect effect on these variables via increasing structural and social resources and increasing challenging job demands. In fact, inconsistent mediation models are models where at least one mediated effect has a different sign from the other mediated or direct effects in a model (MacKinnon et al., Reference MacKinnon, Krull and Lockwood2000). It is ‘more common in multiple mediator models where mediated effects have different signs. Inconsistent mediator effects may be especially critical in evaluating counterproductive effects of experiments, where the manipulation may have led to opposing mediated effects’ (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, Reference MacKinnon, Fairchild and Fritz2007).

It seems that the more employees increase their structural resources and social resources, the more they feel they learn at work. In addition, employees who decrease their hindering job demands increase their ability to learn. Unexpectedly, increasing challenging job demands was not linked to learning. According to Russo (Reference Russo2017), job design influences the amount of learning provided by the workplace and the context features (i.e., advice from supervisors and coworkers) reinforce the learning process. Although organizations can shape the availability of learning opportunities, via job design, learning processes require employees to take some initiative (Russo, Reference Russo2017). Therefore, drawing on their knowledge, skills, abilities, and needs, employees may seek the increasing structural (e.g., taking new responsibilities at work or new and more challenging clients, offering spontaneously more advice to a client, suggesting innovative work practices) and social resources (e.g., coaching from supervisor or advice from colleagues or even from some clients) in order to enhance learning at work. These JC strategies could, however, push employees to deal with higher levels of learning demands that they can view as more hindering job demands (Prem et al., Reference Prem, Ohly, Kubicek and Korunka2017) leading them to try another JC strategy, that is decreasing hindering job demands. Reducing demands is described as withdrawal and avoidance work behaviors in the context of change because employees cannot try this strategy without trying to avoid or disregard some tasks (Petrou et al., Reference Petrou, Demerouti, Peeters, Schaufeli and Hetland2012). Other examples were given by Morales and Lambert (Reference Morales and Lambert2013) who found that accountants' craft theirs accounting practices by delegating tasks and the reporting of accounts, in an effort to resolve inherent contradictions in their identities. Additionally, they tried to hide or reduce tasks that might humiliate their prestigious occupational identities and also fundamentally changed the nature of their practices to mask the existence of accounting-related ‘dirty work’ and to maintain positive self-views (Horton & de Wanderley, Reference Horton and de Wanderley2018).

This study is the first one to test the relationships between JC and thriving at work, which is a different concept from engagement and others. For example, although work engagement refers to dedication and absorption, it does not involve learning (Spreitzer, Lam, & Fritz, Reference Spreitzer, Lam, Fritz, Bakker and Bakker2010). Nevertheless, results of our study should be interpreted with caution.

Limitations

The first weakness of this study is related to its cross-sectional nature, which does not allow us to draw causal relationships. A diary-daily study could capture such effects, but it is always difficult to get many people to fill in such diaries. Furthermore, future studies are needed to examine separately the negative as well as positive dimensions of JC, their effects on vitality and learning, and how the strategies can influence each other. Also, it seems that POC could have an interaction effect in the model. Additionally, there might also be interaction among crafting strategies. These possibilities can be tested in future research to better understand the model and relationships tested.

Theoretical implications

This research contributes from a theoretical and practical perspective. First, this is the first study investigating if JC is linked to thriving at work which highlights the generative feature of thriving and the pool of resources that may enable future thriving (Spreitzer, Lam, & Fritz, Reference Spreitzer, Lam, Fritz, Bakker and Bakker2010). Second, this study helps in understanding how employees can craft their own job to be more energized and to grow at work; little research has focused on the role of organizations to facilitate/mitigate JC (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Katz, Lavigne and Zacher2017; van Wingerden & Niks, Reference van Wingerden and Niks2017). Although van Wingerden and Niks (Reference van Wingerden and Niks2017) have already highlighted that POC increases JC behaviors, this study validates the POC scale in different contexts, and is one of the first to confirm that POC influences vitality and learning with JC behaviors as mediators.

This study also advanced the findings of van Wingerden and Niks (Reference van Wingerden and Niks2017) by examining the four dimensions of JC integrated in the study of Tims et al. (Reference Tims, Bakker and Derks2012) and including the decreasing hindering job demands. In addition, the findings provide support for the complementarity of top down and bottom-up approaches in order to better design employees' jobs and to support crafting behaviors.

The findings highlight the positive but also the potential negative side of JC (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Reference Wrzesniewski and Dutton2001) while research has mainly examined the positive aspects (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Katz, Lavigne and Zacher2017). However, some studies showed that decreasing hindering job demands influences negatively the contextual performance (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Demerouti, Le Blanc and Bipp2015). Tims et al. (Reference Tims, Bakker and Derks2015a) did not reveal a significant relationship between these variables. This study measured the association between POC and decreasing hindering job demands, and the effect on thriving at work, which shows the negative side of JC. Decreasing hindering demands appears to be related differently to antecedents and outcomes compared to the other three JC dimensions. This finding is important to develop improved theories on proactivity (Tornau & Frese, Reference Tornau and Frese2013).

The findings also enhance the predictions on thriving at work and the work design that can support it (Spreitzer, Lam, & Fritz, Reference Spreitzer, Lam, Fritz, Bakker and Bakker2010). This study demonstrates that some JC strategies like increasing structural and social resources or increasing challenging demands can be more efficient than others such as decreasing hindering job demands, which seems largely ineffective.

The research also examines a profession, which has been ignored by researchers as concerns JC, although JC behaviors seem to be quite common among CPAs who adjust the accounting practices by delegating and managing tasks in order to develop positive self-identity (Horton & de Wanderley, Reference Horton and de Wanderley2018). Thus, focusing on this profession makes the contributions of the current study to this literature particularly important.

Managerial implications

The findings indicate that all JC strategies are not efficient for thriving at work and give insights into how organizations can stimulate ‘constructive job crafting’ (Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Bakker and Halbesleben2015) by demonstrating that the POC, which can be increased by more autonomy and job resources, plays a fundamental role in JC behaviors. Managers can positively influence the perception of employees regarding the possibility to craft, shape and optimize their jobs to fit their needs, skills, and knowledge. In accounting, the crafting of relational boundaries can allow more connections between CPAs, and operational managers bringing about greater commercial mindfulness and important changes in accounting roles and practices (Horton & de Wanderley, Reference Horton and de Wanderley2018). This confirms that JC (bottom-up approach) complements top-down approaches of job design in organizations.

Decreasing hindering job demands seems to be an inefficient strategy and managers should encourage employees to avoid such a strategy by seeking a strategy of increasing resources and challenges. Interventions to train and coach employees to use the more effective JC strategies to improve and strengthen thriving at work would be fruitful for organizations.

Sari Mansour holds a PhD in management sciences. He is professor in human resources management at the School of Business Administration, TELUQ-University of Québec. He specializes in HRM, organizational behavior, job design, work–life balance, aging management and psychosocial risk management. His research has been conducted in various professional sectors such as hotels and tourism, healthcare, civil aviation, and so on. He has published his research in several scientific journals: International Journal of Human Resources Management, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Personnel Review, International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development, Journal of Human Resource Development and Management, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Journal of Human Resource Management, Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, International Review of Psychosociology and Organizational Behavior Management.

Diane-Gabrielle Tremblay holds a PhD in economy. She is specialist in human resources management, economics and sociology of work. She has been a professor at the School of Business Administration, TELUQ-University of Québec since 1988. She has held the Research Chair on Socio-Organizational Issues in the Knowledge Economy since 2002 (renewed in 2009) and has obtained significant SSHRC funding for a CURA on age and social time management (www.teluq.ca/CCC-gats). She has also obtained numerous research grants from Canadian and European organizations on themes related to work organization, telework, communities of practice, job–family linkages, as well as local economic development and industrial clusters. She has published her research in several scientific journals: New Technology, Work and Employment, International Journal of Enterprise and Innovation Management, International Journal of Technology Management, Social Indicators Research, Applied Research on Quality of Life, Geojournal, The Journal of E-working, Journal Human Resource Management, Management 2000, Geography, Economics and Society, Social Policy, Industrial Relations.