Introduction

Auxinic herbicides have been applied to crops such as wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) for more than 60 yr, with usage levels in the major grain crops generally decreasing as newer herbicides were added to the market (Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, McMasters, Riechers, Skelton and Stahlmann2016). However, growers are once again becoming more reliant on auxinic herbicides to control weeds in cropping situations, due to the introduction of auxin-resistant transgenic crops and/or the development of widespread weed resistance to other herbicide modes of action. Consequently, there is a risk that this high selection pressure could accelerate the evolution of auxinic herbicide resistance in weeds. This scenario has already been observed in Western Australian populations of wild radish (Raphanus raphanistrum L.), where almost universal resistance to the acetolactate synthase–inhibiting herbicides has resulted in increased use of the synthetic auxins 2,4-D and MCPA and a concomitant increase in the number of 2,4-D–resistant populations (Owen et al. Reference Owen, Martinez and Powles2015). Research aimed at characterization of the resistance mechanism(s) in a number of these populations has ruled out common non–target site mechanisms such as metabolic detoxification, vacuolar sequestration, and reduced herbicide uptake and has pointed to altered synthetic auxin perception or signaling and/or enhanced defense at the plasma membrane (Goggin et al. Reference Goggin, Kaur, Owen and Powles2018). Although many resistant populations exhibit restricted phloem movement of 2,4-D, the extent of this reduced translocation is not correlated with resistance level. Therefore, the precise molecular mechanism(s) of auxinic herbicide resistance in R. raphanistrum remains to be determined.

Arabidopsis [Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh.] plants with resistance to natural or synthetic auxins conferred by mutations in auxin transporters, receptors, signaling proteins, or metabolic enzymes often display characteristic phenotypes such as dwarfism (e.g., Estelle and Somerville Reference Estelle and Somerville1987; Woodward et al. Reference Woodward, Ratzel, Woodward, Shamoo and Bartel2007), lack of shoot apical dominance and inhibited lateral root formation (e.g., Ruegger et al. Reference Ruegger, Dewey, Hobbie, Brown, Bernasconi, Turner, Muday and Estelle1997), twisting and epinasty (e.g., Geisler et al. Reference Geisler, Kolukisaoglu, Bouchard, Billion, Berger, Saal, Frangne, Koncz-Kálmán, Koncz, Blakeslee, Murphy, Martinoia and Schulz2003), altered leaf serration (e.g., Bilsborough et al. Reference Bilsborough, Runions, Barkoulas, Jenkins, Hasson, Galinha, Laufs, Hay, Prusinkiewicz and Tsiantis2011; Kasprzewska et al. Reference Kasprzewska, Carter, Swarup, Bennett, Monk, Hobbs and Fleming2015) and delayed flowering (e.g., Tognetti et al. Reference Tognetti, Van Aken, Morreel, Vandenbroucke, van de Cotte, De Clercq, Chiwocha, Fenske, Prinsen, Boerjan, Genty, Stubbs, Inzé and Van Breusegem2010), but these do not always lead to a reproductive cost (Roux and Reboud Reference Roux and Reboud2005). In general, the phenotypes of weeds with evolved auxin resistance are less differentiated from their susceptible counterparts, although a wild mustard (Sinapis arvensis L.) population with resistance to four auxinic herbicides (2,4-D, MCPA, dicamba, and picloram) contained plants that were smaller, lacked apical dominance, and had darker green leaves that were more serrated than those of a susceptible population (Hall and Romano Reference Hall and Romano1995; Mithila et al. Reference Mithila, McLean, Chen and Hall2012). Plants in a dicamba-resistant common lambsquarters (Chenopodium album L.) population were also smaller in stature and less competitive, but in this case the leaves were lighter green and less serrated than those of the susceptible population (Ghanizadeh and Harrington Reference Ghanizadeh and Harrington2018; Rahman et al. Reference Rahman, James and Trolove2014).

Initial observations made during the generation of seed resources for the 2,4-D–resistant R. raphanistrum populations studied in Goggin et al. (Reference Goggin, Kaur, Owen and Powles2018) suggested possible differences between populations in terms of leaf size and serration, plant stature, and reproductive capacity. Therefore, the current study quantified parameters relating to seedling morphology, flowering, and seed production (with and without competition from wheat) between two herbicide-susceptible and eleven 2,4-D–resistant populations that were previously characterized at the physiological and biochemical level. The potential confounding effects of (1) the different genetic backgrounds of each population and (2) the presence of resistance to non-auxinic herbicides (Owen et al. Reference Owen, Martinez and Powles2015) are partially offset by the use of a large number of populations (Osipitan and Dille Reference Osipitan and Dille2017; Van Etten et al. Reference Van Etten, Kuester, Chang and Baucom2016). Although these populations have different genetic backgrounds and (potentially) auxin-resistance mechanisms, they represent the spectrum of auxin-resistant R. raphanistrum populations present in Australian cropping fields. Thus, it is important to identify any weaknesses in growth or reproduction that could be used to develop nonherbicidal management strategies.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

The 2 herbicide-susceptible (S1 and S2) and 11 resistant (R1–R11) R. raphanistrum populations originally collected from across the Western Australian grain belt (Owen et al. Reference Owen, Martinez and Powles2015) and characterized in Goggin et al. (Reference Goggin, Kaur, Owen and Powles2018) were used for the current study. These field-collected populations had been screened for resistance to the recommended field rates of chlorsulfuron, imazamox + imazapyr (hereafter abbreviated as IMI), diflufenican, atrazine, glyphosate, and bromoxynil + pyrasulfotole as well as 2,4-D (Owen et al. Reference Owen, Martinez and Powles2015), and the observed levels of resistance to these herbicides were taken into account when examining potential effects of 2,4-D resistance on plant characteristics. None of the populations were resistant to atrazine, glyphosate, or bromoxynil + pyrasulfotole (0% plant survival). Survival after chlorsulfuron treatment was >90% in all R populations, whereas resistance to diflufenican (0% to 30% survival) and IMI (0% to 50% survival) was more variable (Owen et al. Reference Owen, Martinez and Powles2015). In the study of Goggin et al. (Reference Goggin, Kaur, Owen and Powles2018), the original R populations were twice selected at the recommended field rate (500 g ae ha−1) of 2,4-D amine in an effort to increase the homogeneity of the 2,4-D–resistance mechanism(s) in each population, and their levels of resistance to 2,4-D and dicamba were quantified in dose–response experiments. The proportion of applied 2,4-D retained in the treated leaf was also quantified in Goggin et al. (Reference Goggin, Kaur, Owen and Powles2018) using 14C-labeled 2,4-D. A summary of the characteristics of each population is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of herbicide-resistance characteristics of the Raphanus raphanistrum populations.

a Rainfall zones (H, 450–750 mm; M, 325–450 mm; L, <325 mm) from which the populations were originally collected are given in parentheses after the population names.

b The resistance indices for 2,4–D and dicamba were expressed as the ratio of the LD50 value (survival) or postspray biomass (growth) of each R population and the mean of the S1 and S2 populations (see Goggin et al. [Reference Goggin, Kaur, Owen and Powles2018] for original data).

c Resistance to chlorsulfuron (Chlor), imazamox + imazapyr (IMI), and diflufenican (DFF) was classified as S (0% plant survival at the recommended field rate); r (1%–19%); or R (≥20%) (Owen et al. Reference Owen, Martinez and Powles2015).

All plants were grown in potting mix (composted pine bark:peat moss:washed river sand, 2:1:1) in pots of 250-mm diameter and 230-mm depth. To ensure uniformity, seeds were pre-germinated on 6 g L−1 agar in the dark for 3 d at 20 C, and then seedlings with radicles of similar length were transplanted into moist potting mix and grown outdoors at the University of Western Australia (31.99°S, 115.82°E) between May and October 2018 (average climatic conditions: maximum/minimum temperature, 20/11 C; day length, 11 h, 6 min; daily solar exposure, 14 MJ m−2). Pots were arranged randomly on five adjacent 4-m2 benches in full sun, watered as required, and fertilized weekly with 500 ml of 1.5 g L−1 commercial soluble fertilizer (Diamond Red [N 27%, P 5.7%, K 10.9%, trace elements]; Campbells Fertilisers, Laverton North, Australia). Aphids were controlled either by hand picking or by spot spraying with commercial pyrethrum formulated for use in home gardens (Pyrethrum Long Life Insect Spray, 0.9 g L−1 pyrethrum + 3 g L−1 piperonyl butoxide, Multicrop, Scoresby, Australia).

Assessment of Seedling Growth and Morphology

For each population, there were five replicates of 5 seedlings pot−1. When plants had reached the 3- to 4-leaf stage (11 d after transplant [DATr]), the first leaf was removed from the biggest plant in each pot, pressed, and dried at 70 C for 48 h, at which time it was photographed, measured, and weighed. Leaf area was measured by weighing cut-out photographs of the leaves and comparing the weights against a standard curve of the masses of known areas of paper, allowing the area of the leaf photograph to be calculated from its mass. At 15 DATr, plant diameter and height were recorded, along with the number of leaves per plant. When floral buds were just visible in most pots (34 DATr), the aboveground plant parts were harvested and dried at 70 C for 72 h and then weighed.

Assessment of Plant Performance in the Presence and Absence of Competition

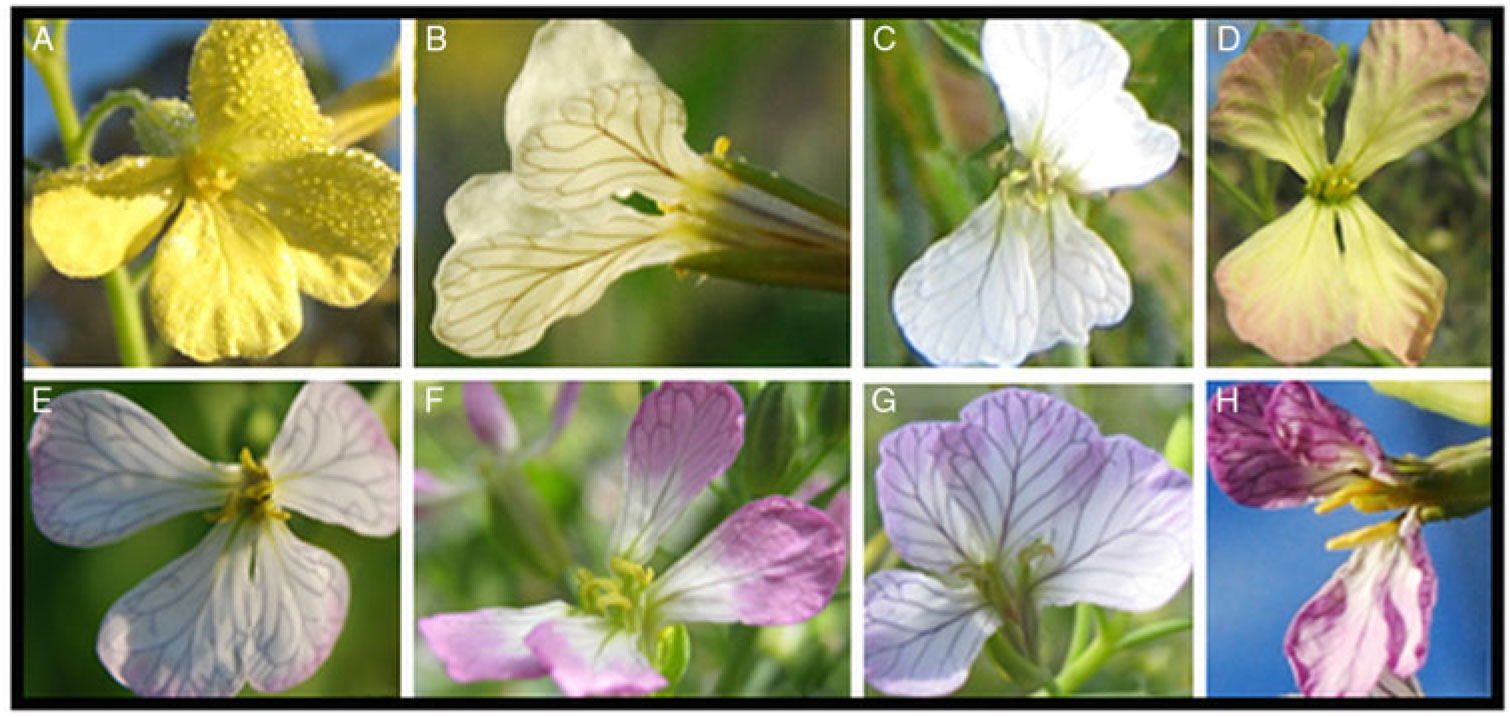

Five replicates of 1 plant pot−1 were set up for each population, either without competition or in competition with 5 wheat (‘Mace’) seedlings pot−1. This corresponds to a wheat density of 100 plants m−2, which approximates commercial wheat crop densities. Wheat seeds were germinated on agar and transplanted into pots at the same time as the R. raphanistrum seeds. Raphanus raphanistrum plants were monitored daily during the experiment, and the following parameters were recorded: date when floral buds first became visible; date of anthesis of first flower; height above soil of first flower; and flower color. The last parameter was arbitrarily quantified by giving scores based on the range of colors observed in the study (Figure 1) and the fact that yellow (carotenoid production) is recessive (color score: 0), while purple (anthocyanin production) is dominant (color score: 7) in R. sativus (Irwin and Strauss Reference Irwin and Strauss2005).

Figure 1. Variation in Raphanus raphanistrum flower color, with arbitrary scores assigned as follows: (A) yellow: 0; (B) pale yellow/cream: 1; (C) white: 2; (D) yellow with purple edges: 3; (E) white with purple edges: 4; (F) purple with white center: 5; (G) pale purple: 6; (H) purple: 7.

Wheat booting commenced at 68 DATr, heading at 74 DATr, and anthesis at 87 DATr. When the wheat had reached maturity, watering and fertilization of all pots was ceased even if the R. raphanistrum plants were still actively growing and flowering. This protocol more closely reproduces conditions in an Australian cropping field, where late-flowering plants might experience terminal drought. Raphanus raphanistrum siliques were collected as they matured to minimize losses through shedding (most plants started shedding siliques before the wheat ears had matured) and stored in a cool shed until harvest was completed. The date of final harvest for each R. raphanistrum plant was recorded, and the aboveground vegetative parts were collected and dried at 70 C for 48 h and then weighed. Once the harvest was complete, siliques were dried in a 30 C oven for 7 d, weighed, and then milled to obtain the seeds. Seeds were weighed and counted, and their dormancy and viability were assessed in a germination test (see following section). Wheat ears were counted, weighed, and threshed, and the seeds were counted and weighed.

Seed Germination Tests

Fifty seeds from each R. raphanistrum plant were placed on 6 g L−1 agar and incubated in the dark at 20 C. Seed germination was counted every 3 to 4 d for 14 d, and the germinated seedlings were removed. At 14 d, ungerminated seeds were transferred to agar containing 50 μM each of gibberellin A3 and fluridone, a combination known to break dormancy in R. raphanistrum seeds (Goggin and Powles Reference Goggin and Powles2014), and placed in a growth cabinet at 20/15 C day/night with a 12-h photoperiod of white incandescent and LED light at 200 μmol m−2 s−1. Germination was counted every 3 to 4 d for another 17 d, and the ungerminated seeds were tested for viability by cutting through the embryos and assessing their firmness and color.

Statistical Analysis

While keeping in mind that the auxinic herbicide–resistance mechanism(s) in the populations studied is not fully characterized, the fitness of each population was calculated using the equation cited in Vila-Aiub et al. (Reference Vila-Aiub, Gundel and Preston2015), where fitness (W) is the product of the proportion of plants surviving after seed dispersal (P) and the number of offspring produced (N). For this study, seed viability was used as a measure of P, and the total number of seeds produced as N. Differences between populations and treatments were assessed by one- and two-factor analysis of variance and the Fisher’s LSD test at a significance level of 5%, as well as by principal component analysis (PCA) using MetaboAnalyst v. 4.0 (Xia et al. Reference Xia, Psychogios, Young and Wishart2009), with autoscaling used for data normalization. As the data were normally distributed according to a quantile–quantile plot (Wilk and Gnanadesikan Reference Wilk and Gnanadesikan1968), but heteroscedastic according to a Bartlett’s test (McDonald Reference McDonald2014), weighted least-squares regression was used to identify possible links between population characteristics and their resistance to 2,4–D and dicamba or ability to translocate 2,4-D out of the treated leaf (all quantified in Goggin et al. [Reference Goggin, Kaur, Owen and Powles2018]). Weighted least-squares regression was performed using the Real Statistics Resource Pack software (release 6.2) in Excel (Zaiontz Reference Zaiontz2019), and correlation coefficients were considered to be significant if P < 0.05. Resistance was expressed as both “survival,” based on the herbicide dose required to kill 50% of the plants in the population (LD50), and as “growth,” based on vegetative biomass of survivors following auxinic herbicide treatment. To account for possible confounding effects due to the resistance of the R populations to other herbicides, the correlation between the various parameters measured in this study and the level of resistance (in this case expressed as the percentage survival of a population sprayed with the recommended rate of each herbicide from Owen et al. [Reference Owen, Martinez and Powles2015]) was also calculated. All significant correlations were plotted to check for outliers distorting the correlation coefficient.

Results and Discussion

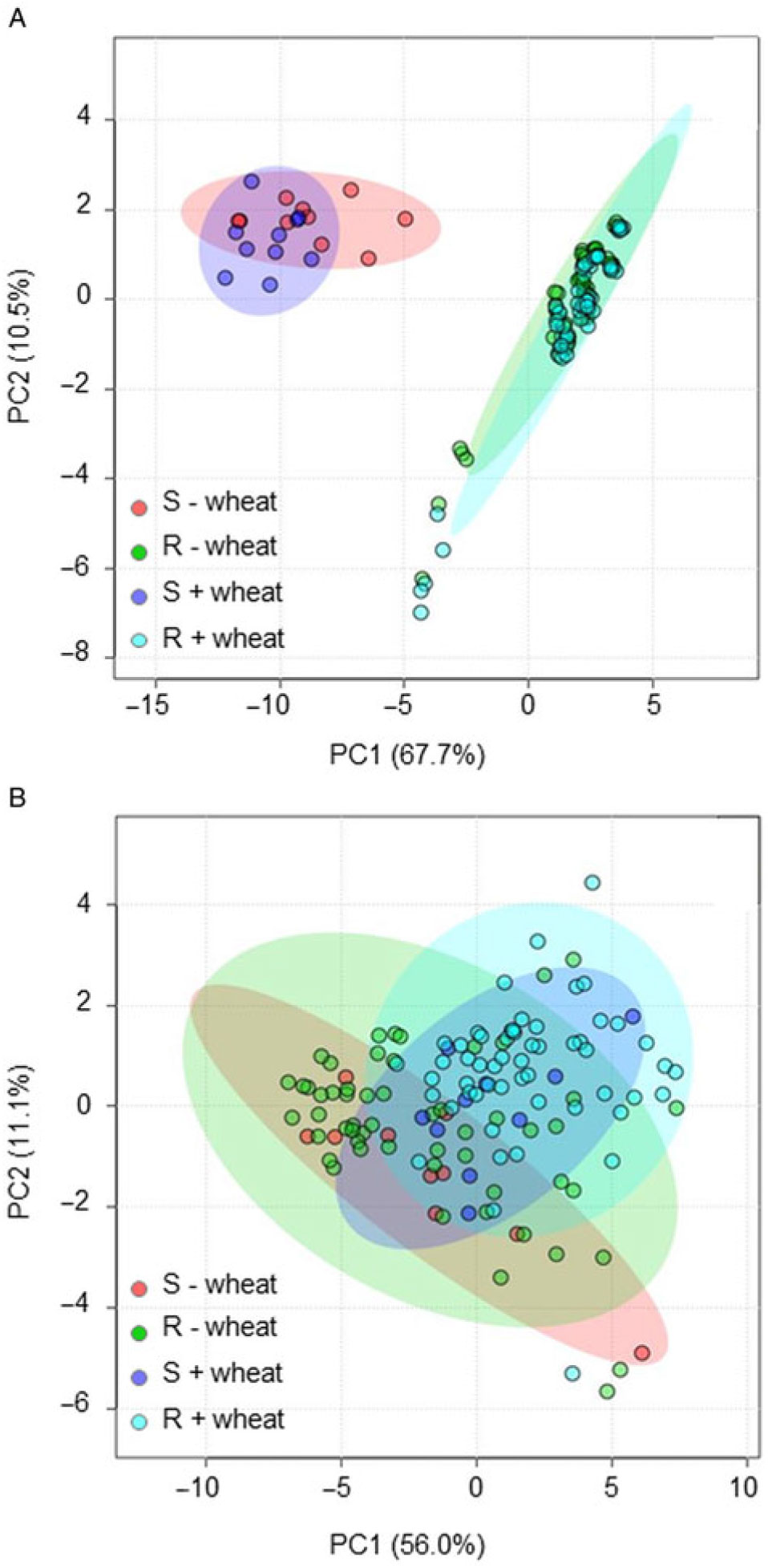

Overall, there were no striking differences among populations in the parameters measured (Supplementary Table S1), despite their geographically distinct origins. As was observed for the biochemical characteristics assessed in Goggin et al. (Reference Goggin, Kaur, Owen and Powles2018), a distinguishing feature of these R. raphanistrum populations is their wide intrapopulation variability, which often precludes identification of statistically significant interpopulation differences. The PCA showed separation between the S and R populations when resistance parameters (LD50 values and postspray biomass for 2,4-D and dicamba) were included in the analysis, but not when only plant growth and seed production parameters were used (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Principal component analysis of growth and seed production of 2,4-D–susceptible (S) and 2,4-D–resistant (R) Raphanus raphanistrum populations grown in the presence (+wheat) and absence (−wheat) of competition, with herbicide-resistance parameters included (A) or excluded (B) from the analysis. Shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals of each group. The first two of eight components in total are shown.

Growth and Morphology of Young Plants

The first leaf of population R8 was around 20% larger than that of most other populations, while the first leaf of R5 was 20% smaller (Supplementary Table S1). Populations R6 and R8 had a 12% larger seedling diameter than most others; R1 had an average of 0.5 extra leaves at 15 DATr; and S2 had 20% higher biomass than most other populations at 34 DATr, while that of R5 was around 25% lower (Supplementary Table S1).

Seedling diameter and the dry mass and area of the first leaf were positively correlated with vegetative growth following dicamba treatment, while there was a negative relationship between specific leaf area and resistance to 2,4-D (postspray growth) and dicamba (survival and postspray growth) (Table 2). Seedling height and dry mass were negatively correlated with IMI resistance, and the same relationship was observed between seedling height and growth after 2,4-D treatment. First-leaf serration was not quantified, but visual examination of leaf photographs shows a level of variability within populations that was similar to the interpopulation variation and no consistent differences between the S and R populations (Figure 3).

Table 2. Significant (P < 0.05) associations between herbicide-resistance parameters and plant characteristics as calculated by weighted least-squares regression. a

Figure 3. Morphology of first leaves of 5 seedlings from each population at 11 d after transplant. Leaves were pressed and dried at 70 C before being photographed.

Although the dicamba-resistant seedlings tended to be of larger diameter and leaf area, the difference between the largest resistant populations and the smallest susceptible population was only around 1.3-fold, which may be difficult for a grower to visually identify before spraying a field with an auxinic herbicide. However, the almost 2-fold difference in height between the most IMI-resistant and the susceptible populations could represent an opportunity for growers to identify fields with high numbers of IMI-resistant seedlings and use an alternative weed control method with a higher likelihood of success.

Performance of Raphanus raphanistrum Populations in the Absence of Competition

Bud formation and anthesis were 2 to 3 wk later in population R2 than in most others, and occurred at least 2 wk earlier in R1 (Supplementary Table S1). The first flower of population S2 was positioned at least 15 cm higher above the soil than in other populations, while those of R5 were around 14 cm lower (Supplementary Table S1). Vegetative shoot dry mass at harvest was around 30% higher in S1 and S2 and 40% lower in R3, and silique dry mass and seed number were close to 40% higher in R9 and 65% lower in R2 (Supplementary Table S1). Mass of 100 seeds was 25% higher in R1 (Supplementary Table S1). Survival and growth after both 2,4-D and dicamba treatments were strongly negatively correlated with vegetative biomass at harvest (Table 2). There was also a positive correlation between the ratio of silique:vegetative biomass and growth following dicamba treatment (Table 2).

The consistent association between auxinic herbicide resistance and lower accumulation of aboveground vegetative biomass suggests that the resistance mechanism(s) in R. raphanistrum causes the plants to divert resources from growth into other processes (reviewed in Vila-Aiub et al. Reference Vila-Aiub, Gundel and Preston2015); for example, constitutive activation of plant defense pathways (Goggin et al. Reference Goggin, Kaur, Owen and Powles2018). However, this potential resistance cost did not extend to seed production, and indeed the populations showing the strongest vegetative growth following dicamba treatment also invested the most in silique production.

Performance of Raphanus raphanistrum Populations under Competition with Wheat

Overall, the presence or absence of wheat competition did not cause a separation of R. raphanistrum populations in the PCA (Figure 2). Competition did not significantly affect certain parameters (e.g., timing of bud formation and anthesis, relative partitioning between vegetative and reproductive mass, mass of 100 seeds), while others (e.g., plant biomass, silique mass, seed number) were decreased by approximately 50% (Table 3). Additionally, the average height of the first flowers was around 25% greater when plants were grown with wheat, and the final harvest occurred 6 d earlier (Table 3). There were no significant differences between pots in terms of number of wheat ears produced (overall mean: 15 ± 0.2 ears pot−1), total ear dry mass (40 ± 1 g), total wheat seed mass (31 ± 1 g), or total wheat seed number (605 ± 15).

Table 3. Effect of wheat competition on Raphanus raphanistrum growth and reproduction. a

a Data for all 13 populations were pooled.

b DATr, days after transplant.

c Significant differences between competition treatments (P < 0.05) are denoted by an asterisk (*).

When R. raphanistrum populations were analyzed individually, there were few differences among them in terms of time of bud formation, anthesis, date of final harvest, or reproductive performance (Supplementary Table S1). The first flowers of population S2 were around 15 cm higher, and S2 also had a 50% greater vegetative biomass at harvest, and R1 and R5 had first flowers that were at least 15 cm shorter than those of most other populations (Supplementary Table S1). Populations with earlier bud formation tended to show better growth following dicamba treatment, and vegetative biomass at harvest was negatively correlated with dicamba survival and posttreatment growth, reflecting the result observed with plants grown in the absence of competition (Table 2). The fact that there was not also a relationship between 2,4-D resistance and biomass at harvest in the presence of wheat suggests that the overall suppression of biomass production caused by competition masks the observed growth penalty inflicted by 2,4–D resistance in the absence of competition. As the relationship between dicamba resistance and plant biomass was expressed in both the presence and absence of competition, it is possible that dicamba resistance imposes a greater cost on vegetative growth than does 2,4-D resistance, but a firm conclusion cannot be drawn until the precise resistance mechanisms are known.

Previous work has shown that a combination of 2,4-D treatment and competition from wheat at ≥100 plants m−2 was successful in controlling one 2,4-D–resistant R. raphanistrum population, but not another (Walsh et al. Reference Walsh, Maguire and Powles2009). The surviving population from that study corresponds to the population designated here as R1, which exhibits the lowest level of 2,4-D resistance of the 11 R populations tested (Goggin et al. Reference Goggin, Kaur, Owen and Powles2018). Therefore, although useful in suppressing R. raphanistrum in general, as also observed by Eslami et al. (Reference Eslami, Gill, Bellotti and McDonald2006), crop competition alone is not likely to be more effective on auxin-resistant vs. auxin–susceptible populations.

Seed Dormancy and Viability

Overall, R. raphanistrum seed viability and responsiveness to germination stimulants was not affected by wheat competition during seed production, but the level of primary dormancy was slightly higher (i.e., lower germination at 14 d after the start of imbibition, just before the seeds were transferred to germination stimulants) under competitive conditions, and fitness was decreased by more than 50% (Table 3). Between populations, the viability of seed produced by S2 and R9 grown without competition was lower than for the other populations, but seed viability was >90% in all populations (Supplementary Table S1). In spite of population R9 having slightly lower seed viability, its calculated fitness in the absence of competition was at least 80% higher than that of most of the others due to its high seed production. Under competitive conditions, however, there were no differences between populations in terms of fitness (Supplementary Table S1). Primary dormancy was highest in populations R3, R6, and R9 under both competitive and noncompetitive conditions, while R7 seeds were the least dormant (Supplementary Table S1). Population R7 was also the most responsive to germination stimulants, with 50% germination occurring at least 5 d earlier than in most other populations (Supplementary Table S1). Under competitive conditions, there was a moderate negative correlation between vegetative growth after 2,4-D treatment and germination at 14 d (Table 2).

Based on the slightly higher dormancy of seeds produced by the R populations, it could be beneficial to delay sowing the next season’s crop in a field with a high number of 2,4-D survivors so that the next generation of R. raphanistrum can be controlled with nonselective, pre-sowing herbicides. Alternatively, a highly competitive crop or pasture could be sown early, to suppress the late-emerging auxin-resistant R. raphanistrum seedlings. A similar situation exists in glyphosate-resistant (Beckie et al. Reference Beckie, Blackshaw, Leeson, Stahlman, Gaines and Johnson2018) and auxin-resistant (Kumar and Jha Reference Kumar and Jha2016) kochia [Bassia scoparia (L.) A. J. Scott], in which the slower germination of the resistant populations could potentially be exploited using the same strategies.

Other Considerations

Populations that retained a higher proportion of applied 2,4-D in the treated leaf tended to have a higher number of leaves at 15 DATr, a higher ratio of seed:silique biomass (no competition), a higher silique biomass (under competition), and, interestingly, flowers that were more likely to be purple (Table 2). High concentrations of auxin have been shown to initiate leaf formation in seedlings (Bar and Ori Reference Bar and Ori2014), stimulate fruit production (Figueiredo and Köhler Reference Figueiredo and Köhler2018), and inhibit biosynthesis of anthocyanins (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Shi and Xie2014) and carotenoids (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Shao, Zhang and Wang2015). Therefore, the alteration in auxin transport that seems to have developed under repeated selection with 2,4-D may have minor effects on leaf formation, resource allocation, and floral pigment production by affecting local auxin concentrations, although this does not have a significant impact on plant performance. These correlations are, however, based on population-level characteristics, and experiments in which translocation or resource allocation are assessed in individual seedlings with known flower color have not yet been performed.

Management of Auxin-Resistant Raphanus raphanistrum

The lack of an obvious resistance cost in 2,4-D– and dicamba-resistant R. raphanistrum is similar to the situation observed in several other auxin-resistant weeds, such as horseweed (Erigeron canadensis L.) (Kruger et al. Reference Kruger, Davis, Weller and Johnson2010), musk thistle (Carduus nutans L.) (Bonner et al. Reference Bonner, Rahman, James, Nicholson and Wardle1998), yellow starthistle (Centaurea solstitialis L.) (Sterling et al. Reference Sterling, Lownds and Murray2001), and B. scoparia (Menalled and Smith Reference Menalled and Smith2007) (although it must be noted that a different B. scoparia population, resistant to both dicamba and fluroxypyr, did exhibit a significant resistance cost [Kumar and Jha Reference Kumar and Jha2016]). In tall buttercup (Ranunculus acris L.), the fitness penalty identified in the resistant population was too slight to make a practical difference (Bourdot et al. Reference Bourdot, Saville and Hurrell1996).

There also seems to be little opportunity to exploit any resistance costs in 2,4-D–resistant R. raphanistrum populations, apart from the slightly higher seed dormancy described earlier. In spite of the lower biomass of resistant populations, there was no impairment in seed production, so it is expected that 2,4-D–resistant individuals of R. raphanistrum found across the Western Australian grain belt would not decline in frequency relative to susceptible individuals in populations if use of 2,4-D was discontinued. Therefore, effective practices already in place, such as rotation and mixing of still-effective herbicides (including synthetic auxins at the full recommended doses), harvest weed seed control, and high crop-sowing rates, need to be rigorously maintained to mitigate the further evolution and spread of auxin-resistant weeds. It is also worth exploring the observed reduction in seedling height associated with resistance to imidazolinones, by studying populations that are resistant to this mode of action but still susceptible to auxinic herbicides. If the relationship is found to be reliable, growers may be able to readily identify fields with potential imidazolinone-resistance problems and avoid the use of these herbicides on plants that will not be adequately controlled.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/wsc.2019.40

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Australian Research Council (project no. LP150100161). CS is an employee of Nufarm Australia, which manufactures and sells auxinic herbicide products. We thank Paula Reeve for threshing the wheat and R. raphanistrum seeds generated in the study, Mechelle Owen for providing the original R. raphanistrum populations and accompanying information, and the two anonymous reviewers whose suggestions helped to improve the article.