Introduction

As part of the UK government’s initiative to improve access to mental health care services (e.g. Department of Health, 2008; Scottish Government, 2008), an increasing number of National Health Service (NHS) staff from different disciplines are being trained in the delivery of psychological interventions. The most widely used intervention is cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), which has been recommended by the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) for a range of mental health difficulties (e.g. NICE, 2009; NICE, 2011; NICE, 2014).

Consequently, more staff are being trained in the delivery of CBT to meet demand across different levels of care. Successful implementation of the required competencies (e.g. Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2008) is required to ensure effective service provision. In doing so, it is important to understand the effects of training and how different training elements affect CBT skill development.

Bennett-Levy and colleagues’ (Reference Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling and Fennell2009) survey of 120 CBT therapists found that different training methods were thought to aid different types of skills. Declarative knowledge was reported to be best enhanced through reading and lectures, whereas procedural skills were thought to benefit most from modelling, role-play and reflective practice. These results echo the view that workshops or didactic instructions alone are not sufficient for CBT skill development (Westbrook et al., Reference Westbrook, Sedgwick-Taylor, Bennett-Levy, Butler and McManus2008), and that the ‘gold standard’ of training incorporates a combination of both didactic and supervisory components (Rakovshik and McManus, Reference Rakovshik and McManus2010; Sudak et al., Reference Sudak, Codd III, Ludgate, Sokol, Fox, Reiser and Milne2015). As Rakovshik and McManus’ (Reference Rakovshik and McManus2010) extensive review of studies on the efficacy of CBT training illustrated, supervision is a particularly important component of the experiential and interactive learning elements of training that help promote consolidation. However, the authors also note that much is still to be learnt about effective training, including developing understanding of the role of supervision.

The role of supervision in CBT training

Supervision is now recognised as a crucial aspect in the training of mental health professionals, and CBT trainees in the UK are required to have a minimum level of supervision ‘contact time’ (BABCP, 2012; British Psychological Society, 2014). Furthermore, supervision is viewed as essential for building confidence and supporting trainees through the difficulties of early experiences with clients (Folkes-Skinner et al., Reference Folkes-Skinner, Elliott and Wheeler2010; Wheeler & Richards, Reference Wheeler and Richards2007) and can serve as a form of ‘quality control’ and evaluation of professional functioning (Sudak et al., Reference Sudak, Codd III, Ludgate, Sokol, Fox, Reiser and Milne2015; Watkins, Reference Watkins2012). Thus, supervision plays a significant role in CBT trainee development by improving their learning and monitoring future practice (Falender and Shafranske, Reference Falender and Shafranske2004; Fleming and Steen, Reference Fleming and Steen2013).

Research has demonstrated that adding supervision to training programmes results in better outcomes for trainees (e.g. Öst et al., Reference Öst, Karlstedt and Widén2012; Rakovshik et al., Reference Rakovshik, McManus, Vazquez-Montes, Muse and Ougrin2016; Westbrook et al., Reference Westbrook, Sedgwick-Taylor, Bennett-Levy, Butler and McManus2008). Rakovshik and colleagues (Reference Rakovshik, McManus, Vazquez-Montes, Muse and Ougrin2016) found that CBT skills measured after training were higher in trainees who received supervision as part of their training than in trainees who did not. Additionally, survey research has shown that trainees view supervision as a vital part of their CBT training (Westbrook et al., Reference Westbrook, Sedgwick-Taylor, Bennett-Levy, Butler and McManus2008), and perceive it to have a greater effect on their skill development than any other training element (Rakovshik and McManus, Reference Rakovshik and McManus2013). These studies demonstrate the importance of supervision as part of CBT training; however, much of the existing literature has focused on quantitative measures, which do not give a complete picture of what happens within supervision (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Davies and Weatherhead2016). For instance, it is not clear how specific aspects of supervision aid trainees in their learning and how trainees experience supervision as part of their skill development.

The present study

Studies investigating different aspects of supervision and their impact on trainee therapists were explored in a recent meta-synthesis of 15 qualitative studies (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Davies and Weatherhead2016). One over-arching concept developed from the synthesised themes was that ‘different learning opportunities within supervision allowed participants to build their confidence and professional identity’ (p. 345). Important learning opportunities were: the provision of alternative approaches to specific issues with their patients, being able to observe their supervisor’s practice, and being encouraged to reflect on supervision.

In another study, Folkes-Skinner et al. (Reference Folkes-Skinner, Elliott and Wheeler2010) qualitatively explored aspects of a counsellor training programme that were helpful to trainee development. Role play in supervision was perceived as important to professional development and receiving reassurance helped build confidence.

These studies provide insight into those aspects of supervision that are deemed important by trainees; however, it remains unclear how trainees experience supervision as part of their learning. Furthermore, little seems to be known about the specific experiences of CBT trainees.

The present study set out to explore CBT trainees’ perspectives on how supervision aids skill development, and what specific aspects of supervision they experience as valuable to their learning. By qualitatively unpacking the dimensions of supervision that are experienced as salient in trainees’ learning, a better understanding of their needs is expected to be gained. Additionally, potential weaknesses in supervision can be identified. The findings could inform future training and supervision practice, potentially contributing to the improvement of CBT training and competence development.

Method

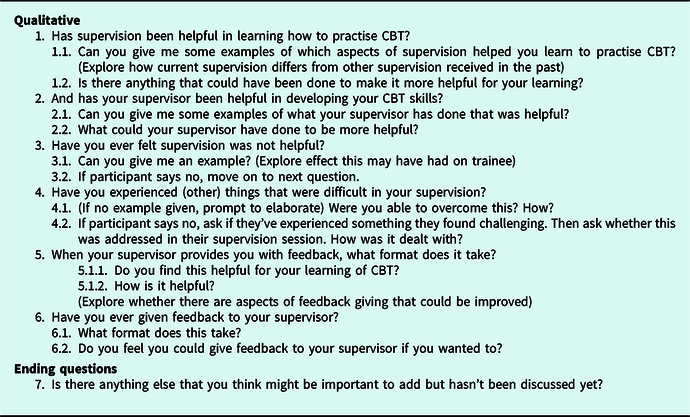

Semi-structured interviews were employed to allow for open-ended responses. The interview questions were designed with a view to generating rich and detailed accounts (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013; Forrester, Reference Forrester2010) and were developed in consultation with colleagues who had particular expertise in supervision and CBT (authors S.H. and L.N.). Questions were designed to open up discussion about all experiences in supervision. A list of the questions generated is contained in Table 1. These questions were further reviewed and considered valid and appropriate by a group of experts in CBT involved in the delivery of supervision and clinical training in Scotland. Prior to completion of the interview guide, a pilot study was conducted with a neutral trainee who was out with the studied cohort (a clinical psychologist who had previously been trained in CBT). This allowed the researcher to confirm that the questions were easily understood and that appropriate responses could be generated.

Table 1. Questions generated

The interviews were recorded on two voice recorders. To encourage participants to speak openly about their experiences, a conversational interview style was adopted that allowed for the discussion to steer away from the interview guide where appropriate, and for the interviewer to probe for further details and clarification. All participants were asked each question on the interview guide.

Participants

Participants were recruited from a CBT training programme for healthcare professionals provided by NHS Lothian and NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde in collaboration with Queen Margaret University. The average age of those in the study was 42 years and 82% of the sample were female. Participant professions were 73% community psychiatric nurses, 18% health psychologists and 9% were counsellors. All participants were therefore very experienced mental health professionals with undergraduate degree level status and many years post-qualification experience. Also, all participants had some experience in the delivery of low-intensity CBT-informed psychological interventions.

Of a total cohort of 20 trainee cognitive behavioural therapist, a convenience sample of 11 volunteer participants agreed to take part in the study, all of whom were interviewed individually face-to-face (one interview was conducted over the telephone). Fifty-five per cent of participants were studying at certificate level in CBT and were offering CBT in their trainee capacity to clients with mild to moderate disorders of anxiety and/or depression, consistent with the aims of the certificate training programme. The other 45% of participants were studying in their second year of CBT training working with more complex disorders on anxiety and depression, so were more experienced in receiving CBT supervision at the time of the study commencing. All participants were approximately midway through their training programme for the year so were well engaged in the supervisory process and relationship. In addition, all those interviewed at this stage had successfully passed an academic essay on CBT and one assessment of CBT competence through a CTS-R rating of live practice for their respective year of study.

The supervisors of the participants were experienced cognitive behavioural therapists, all of whom had training in the supervision of psychological therapists. This training is based upon the competence framework for the supervision of psychological therapies (Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2009) and covers the objectives of supervision, supervisory relationship, supervision models, feedback and professional issues. It involves a mix of e-learning, interactive teaching and peer discussion totalling 20 hours. Over 1000 supervisors have attended this training programme (the Generic Supervision Competencies Training (GSC) in Scotland; Bagnall et al., Reference Bagnall, Sloan, Platz and Murphy2011).

Supervisor core professions were from clinical psychology (18%), counselling psychology (9%), cognitive behavioural nurse therapists (55%) and psychiatry (18%). The majority of supervisors were male (73%) and were aged between 40 and 55 years (see Table 2 for summary of profession of supervisors and trainee participants). In order to meet criteria to supervise on the programme, supervisors will have been practising CBT for at least 2 years post-qualification. Some will have also attended specialist training in CBT supervision training (Ferguson et al., Reference Ferguson, Harper, Platz, Sloan and Smith2016) and all supervisors are also required to have attended workshops for supervisors delivered by the CBT training programme, which covers core expectations/requirements of supervisors on the programme. All supervisors are involved in the programme marking of audios of therapy assessed using the CTS-R (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001) for students other than their own supervisee. All audios are double marked with one of the programme team in order to benchmark standards of CBT delivery and maximise clarity of communication for trainees on interpretation of CTS-R competencies. All supervisors are also invited to regular group supervision of supervision facilitated by the programme team in order to support supervisors and provide feedback on any issues arising for trainees.

Table 2. Participant profession

Supervision for trainees on the programme requires a minimum of 1.5 hours fortnightly, where a mix of methods including feedback on live practice (using CTS-R as a formative tool), observation of practice, role play as well as case review are required. The training programme is benchmarked at Post Graduate Masters level 11, and trainees attend on a part-time basis. Trainees are required to demonstrate competence in CBT practice (rated by CTS-R), theory of CBT (via an essay) and integration of theory to practice via two case studies. The Certificate Programme is delivered over 1 year of study and the Diploma for a further 1 year of study which, on completion, allows graduates to practise CBT for disorders of mild to moderate anxiety and depression and complex disorders of anxiety and depression, respectively, mapping on to the CBT competency framework defined by Roth and Pilling (Reference Roth and Pilling2009).

Method of analysis

The recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013). This method was chosen as it lends itself to identifying, analysing and reporting patterns across a qualitative data corpus. Furthermore, thematic analysis can be used to provide a rich overall description of interview data, which was appropriate for the present study’s aim of exploring how trainees experience different aspects of supervision.

An inductive approach was taken by paying equal attention to each data set and by coding diversely, so where a data item consisted of several different codes the aim was to ensure that all were captured, consistent with the procedures described by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2013). In deciding which codes were developed into themes, two factors were considered. Firstly, the frequency with which something occurred in the data corpus was noted during the coding process. Secondly, items in the data that captured something important in relation to the aims of the study were also included (Buetow, Reference Buetow2010). ‘Important’ data items included those items that could advance the understanding of the subject at hand, and those that address problems that are interesting in relation to the research topic. This approach allowed for the inclusion of data items that would otherwise go unnoticed if the focus was purely on recurring codes. Thus, the themes presented here were developed from codes that were either important, recurrent, or both, in relation to the research question.

Procedure of analysis

In carrying out the analysis, the following procedure was followed. First, the audio recordings were transcribed verbatim into a Word document and then checked against the recordings for accuracy. This resulted in 31,090 words of transcripts, which were then read and annotated iteratively, noting down any observations of interest. All of the transcripts were then coded, giving equal attention to each data item and ensuring that relevant features of the data were evoked. The software NVivo was employed to allow for a coherent and consistent organisation of the codes as suggested by Bazeley and Jackson (Reference Bazeley and Jackson2013). This process resulted in 109 codes that were then organised into themes using the criteria as described above.

The researcher was independent to the programme and coding of interviews were cross-checked with an independent rater (who was also independent to the study and considered expert in qualitative analysis) to ensure reliability of themes emerging from the data. The themes were then checked between the study authors with concordance reached regarding the key themes.

In presenting the data, extracts were carefully distilled from the data corpus to capture the centralising concepts of the over-arching themes. To ensure anonymity, participant names were changed to numbers, and the sex of their supervisor was neutralised (i.e., ‘he’ or ‘she’ was changed to ‘they’). Where necessary, repetitions in the data extracts were removed to allow for a more coherent reading. In presenting and discussing the results, participants will henceforth be referred to as ‘trainees’.

Results

During analysis, four themes and three subthemes were developed (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of themes and subthemes developed during analysis

Linking theory to practice

The key finding from the analysis of the transcripts was that trainees perceived supervision to be essential to their learning as it helped them link theory to practice. The most common difficulty reported by trainees was being able to ‘bridge that gap (P1, l. 112) between classroom teaching and delivering CBT to a patient. This difficulty was particularly felt in situations where patients did not present ‘in a textbook way’ (P3, l .96).

‘…actually applying the skill of CBT is really difficult, understanding CBT maybe is a bit simpler but then when you’ve got someone in front of you it becomes really difficult to actually use the technique or use, trying to put the theory into practice…’ (Participant 5, lines 47–50)

In helping trainees learn to implement theory in practice, trainees reported the following aspects of supervision to be most useful: The use of audio recordings, Discussing formulations and The use of modelling and role-play.

The use of audio recordings

The most frequently mentioned element of supervision that trainees found to be useful was the use of audio recordings of their therapy sessions. This approach enabled trainees to discuss and listen again to their therapy sessions together with their supervisor, which helped them better understand their own practice and alerted them to areas in need of improvement. Some trainees reported that they experienced initial worries about feeling exposed, and that the prospect of somebody listening to their work was ‘daunting’ (P1, l. 213). However, once trainees overcame that initial ‘cringe factor’ (P11, l. 25), they found the use of recordings to be very helpful in aiding their skill development. Trainees felt that recordings are very effective in conveying what happened in therapy sessions, which can be difficult to capture in verbal reports.

‘I think the probably most helpful things, as painful as they are, is when we’ve reflected on actual recordings… my supervisor can actually hear what it’s like to be with some of the patients that I’m actually working with, which obviously gives a real sense of what they’re like, what they’re like to work with, what they’re like when they go off, erm, and trying to pull them back, erm, but also what the rapport’s like, and you get a really good sense of that from the recordings, it’s very real compared to, erm, me just saying that I’ve got a good rapport with someone, erm, so yeah, that’s been really, really helpful.’ (Participant 9, lines 23–40)

Through discussing the recordings with their supervisor, trainees gained a better understanding of how well they delivered CBT. Trainees reported that hearing where they did something well and where they needed to improve helped them get a better sense of their own performance. ‘Having another ear listening’ (P3, l. 69) and receiving input on the recordings increased trainees’ awareness of how they could respond differently and thereby improve their ability to successfully implement CBT.

The feedback that trainees received on particular sections of the recordings also drew their attention to aspects of their own practice of which they were previously unaware. Trainees were then able to take this information into subsequent therapy sessions and implement their supervisor’s recommendations.

‘…they’ll ask me to play bits back that I’ve maybe, kinda skirted over, and they’ll, they’ll focus on something specific… the other day we sat and listened to some patient who has, erm, social anxiety, and the patient said something and I quickly moved onto another topic, and my supervisor said “What I would do there would be pursue that a bit further with the patient and try and elicit more cognitions”… they were very aware that I had not picked up something that they might have with the patient and they would have pursued that bit further and done a bit more questioning around it, whereas I had gone onto the next thing, so for me that was huge, I am, I’ve really taken that on and used it the next time.’ (Participant 3, lines 57–66)

Overall, trainees felt that the use of recordings was vital in helping them understand where they needed to improve and what they did well. Being able to reflect on and discuss specific examples in the recordings enabled trainees to improve their delivery of CBT and use this information to implement it in future sessions. Listening again to therapy sessions together with their supervisor also helped draw attention to aspects of the trainee’s practice that they had not noticed themselves previously.

Discussing formulations

In learning how to apply theory to practice, trainees felt that working through formulations with their supervisor was particularly useful and developed a better understanding of applying the CBT framework to their practice. This was particularly true for instances where trainees were confronted with complex cases that made application of their theoretical knowledge more challenging, e.g. when meeting a patient that presented with several additional problems to what was stated on their referral form. By discussing their formulations with their supervisor, trainees were able to learn what they needed to focus on and gain a different perspective, helping them build on their skills and regain confidence in their abilities.

‘…it was a case where I questioned my own competence, erm, and if this was the right patient for me, erm, but then after going through that with my supervisor, they were able to then say “No, this is the case that you need to be looking at”. This particular patient had a lot of things going on, in their own personal life… I was thinking it was too much for me. Erm, but yeah after speaking in supervision has kind of reaffirmed that this is, “This patient would be good for you and this is what you’re kind of looking at”. My supervisor was able to highlight, you know, things to look at going forward, erm for helping with the formulation for this patient.’ (Participant 1, line 157–166)

Trainees reported that receiving input and recommendations on the formulations they had generated helped them understand how to integrate information from assessments within the CBT framework. Through working on the formulations collaboratively, trainees learned how to make sense of their patients’ presenting problems, thereby improving their skills in generating formulations.

‘…my supervisor would actually sit with me and we would formulate what, what my interpretation of what I thought the client was saying or doing. So that to me stood out, it was something completely different, erm, and I, I find that, again I find that hugely helpful, er, because I was just able to apply that back into my sessions, erm and I was able to help my clients then, whatever they were saying or how they were saying it, presenting it, we were able to put into a CBT framework quite easily.’ (Participant 5, lines 79–84)

By discussing their formulations with their supervisor, trainees were further able to get a second opinion on their ‘hypotheses’. Where their supervisors generated a different formulation, trainees were able to use this information for their learning.

‘…it’s almost they’re being a therapist by proxy, kinda, they’re formulating as we talk, so that’s useful to see how they take the same information I’ve gathered from patients but they maybe put it into a slightly different, erm, formulation than I do, so I can then obviously sort of use this to learn.’ (Participant 3, lines 110–113)

Working through formulations in supervision sessions helped trainees learn how to apply their theoretical knowledge to the sessions with their patients. In particular, being able to discuss and compare their formulations with that of their supervisor gave trainees insight into how to make meaning of clinical presentations, focus on the important aspects of complex cases and provided them with confidence when they doubted their abilities.

The use of modelling and role-play

In learning how to implement their theoretical knowledge in practice, trainees also reported the use of modelling and role-play to be of great utility in their skill development. Specifically, the provision of concrete examples and phrases to use in sessions with patients was regarded as valuable for their learning. Although trainees learn key phrases in lectures and textbooks, these can often feel ‘robotic’ (p. 10, l. 34) and are not always appropriate in a given situation with a patient. By being able to work through specific examples of patient interactions with their supervisor, trainees could expand their repertoire, thereby becoming more flexible and versatile as a therapist. The playing out of different scenarios with their supervisor also helped trainees get a better feel for how to respond in situations where they previously felt stuck.

‘I’ve had a few [supervision] appointments where we almost, like, thought out doing it, and, like, my supervisor said exactly how they would say it, and then I’m able to then say “Yeah, but then she’ll be avoidant and she’ll do this, and she’ll be defensive and say this, that and the other”, and seeing how my supervisor dealt with that, and then I just think, you know, it’s given me confidence so then sometimes in my sessions when you sort of think [laughs] “Right I’m just repeating what my supervisor said”, but that, then that’s, I am actually doing it.” (Participant 10, lines 51–57)

The learning of alternative approaches to patient interactions is an effective method for trainees to build on their pre-existing knowledge and become more skilful in delivering CBT. Where supervisors provided their trainees with specific words and phrases to use, trainees were able to build on their skills and develop new ways of responding to their patients.

‘…sometimes it will just be very much about certain phrases that I’d document in supervision that my supervisor suggests and I will use those, you know, and, and really just trying, it’s almost like then what we’ve had in supervision or what we’ve discussed I’m really bringing into the session, and really trying to apply that in a real way, ‘cos sometimes, you know, with the experience my supervisor has they’ll come out with phrases that I might not have thought of saying in a particular way that I think the patient would really connect to, erm, and that, that really helps me.’ (Participant 9, lines 82–89)

Modelling and role-play in supervision can greatly enhance a trainee’s learning as it helps them get a better understanding of different ways of responding to a patient. Through playing out scenarios with their supervisor, trainees learn to go beyond the standard textbook phrases, which can be limited in their applicability. By observing how their supervisor would react and by being given alternative words and phrases to use in sessions with their patients, trainees can learn new ways of responding, thereby improving their CBT skills.

Mirroring CBT in supervision

Some trainees reported that their supervisor used an approach in session mirroring that of the delivery of CBT. Trainees found this method to be very helpful in their learning as it gave them aims to work towards and encouraged them to reflect on their work. Using an agenda, and setting homework and action plans helped trainees develop a structured learning process together with their supervisor. Rather than being taught in a one-direction fashion, trainees could incorporate their own goals and ensure that issues important to them were discussed in supervision. Trainees also felt that this approach shaped the relationship between them and their supervisor in a positive way.

‘I think my supervisor was applying the CBT techniques, so guided discovery, Socratic questioning, which was useful to see and it’s quite subtly done, so it engages you, and, and you end up building a good relationship with your supervisor, rather than walking into supervision in terms of “Oh God, here we go again another 50 minutes, what am I gonna say?”… I’m enjoying this, and it is hugely helpful to my practice.’ (Participant 5, lines 54–62)

When comparing the CBT approach to other supervision styles, trainees felt that the sessions were more focused on their development, rather than results or the outcome of their work. Trainees felt more listened to and encouraged to reflect on their work.

‘…the supervision I have now is very much, it’s a slower pace, it slows things down, so I can really, like, I use the word “reflect”, so it’s much more reflective, whereas previously I wouldn’t have that opportunity, it would be like “Where’s your patient at, where are they at in the treatment process, what have we still to do with them, what’s the plan, what’s the next step”, erm, whereas this is more, it’s, erm, asking me “Right so what’s, what do you think that’s about from the patient, how can we get the patient to come to that conclusion”, rather than, kind of teaching or leading.’ (Participant 3, lines 75–81)

Although clearly a more challenging approach to supervision, trainees expressed their preference for being encouraged to reflect on their thinking processes and coming up with their own ideas, in comparison with previous experiences of supervision.

‘…when I’m getting supervision [from outside of CBT training programme], they’re not very CBT with me, it’s more reassuring, you know, rather than actually sort of, exploring things with me, and I think maybe I come to session and just “Uff”, like offload a lot of feelings and thoughts, and quite rapid, erm, maybe if they would do a bit more CBT with me, they could slow me down and maybe say “Let’s look at this”… rather than throwing ideas at me, I would rather they drew something out of me and reflect back on what I’d said.’ (Participant 4, lines 30–34)

The CBT approach employed by supervisors was welcomed by trainees as they felt that it placed more emphasis on their learning when compared with other supervision styles. The use of guided discovery supported trainees in generating their own ideas and in reflecting on their thoughts, which aided their development. Being able to come away with an action plan and specific learning points helped trainees focus on the areas they needed to develop. Additionally, it helped them make more effective use of the time with their supervisor and consider what they wanted to discuss in their session. Overall, trainees felt that an interactive trainee–supervisor relationship – as opposed to ‘offloading’ and receiving reassurance – was more beneficial to their skill development.

The expert supervisor

Some trainees reported that having a supervisor who was an expert in the modality and in the disorders they were learning about gave them more confidence and helped them understand if they were delivering CBT correctly. A number of trainees were previously taught different therapeutic modalities, which they at times found difficult to ‘shift’ (P10, l .110) from their practice. Trainees felt that having an expert supervisor helped them differentiate CBT from other modalities and gave them more confidence in their supervisor’s ability.

‘…my current supervisor is actually a CBT therapist and only focuses on CBT, and I found that to be really helpful … whereas with my previous supervisor had different models so they were more eclectic and not everything was CBT-driven, so it was attachment-based theory or it was based on Roger’s person-centred theory and I wasn’t finding that I was going into sessions using CBT all the time, so I remember looking at some recordings and “well is that really CBT or is this actually just person-centred therapy or counselling?”… so I feel with my current supervisor I’m more practising CBT, and types of CBT, whereas with the other supervisor, who I thought was brilliant as well, but it wasn’t necessarily CBT, it was just being a therapist.’ (Participant 5, lines 87–99)

Trainees’ reluctance to give negative feedback

A number of trainees showed reluctance in telling their supervisor when they were unhappy with supervision or felt that it was not working for them. Some trainees worried that appearing critical of their supervisor could negatively impact the relationship or their course grade, whereas others felt that it was not their ‘place’ (P5, l. 131) to give feedback to their supervisor. This hesitancy around expressing criticism towards their supervisor left trainees feeling unable to ask for changes, resulting in their training being a ‘struggle’ (P7, l. 110). Rather than voicing their concerns, trainees instead just continued with it.

‘… when you’re in the middle of the course and you need, you need to have that relationship and it’s a core part of developing your CBT skills, so it wouldn’t have been helpful to raise, it could have made it more difficult… if the relationship isn’t particularly strong and then you’re raising difficult things it could be perceived as criticisms, I suppose it might be then very difficult when you’re going through a course and you have to have that to pass the course so you want, you want it to work, it needs to work. And it’s a year’s course and my approach was just to get through this.’ (Participant 8, lines 70–81)

‘Er, I probably would not [give negative feedback], and that’s to do with me, that’s to do with me not wanting to create a difficult situation, erm because we work together so we have to have a working relationship… I’ve given positive feedback, you know, I’ve told them when something’s been really helpful, but I don’t think I’ve, er, given any negative feedback. I guess I’ve just kind of dealt with it…’ (Participant 3, lines 187–192)

Although these trainees were dissatisfied with their supervision, they also stated that they were appreciative of their supervisor’s time, noting that they are a ‘busy person’ (P4, l. 140) and ‘really working hard’ (P3, l. 104). Trainees also reported an awareness of their supervisor being ‘higher up’ (P4, l. 237), suggesting a perceived imbalance in the trainee–supervisor relationship.

‘I don’t know if I would feel confident putting that on the agenda, they’ve not put it on the agenda, so I think it would have to come from them [pause], it’s a power kind of thing, you know, they’re, you know, I mean I’m very grateful for their time but don’t quite feel like I could say “Oh, well actually, can I give you some feedback?” [laughs]’ (Participant 4, lines 216–220)

Difficulties for trainees addressing issues arising in supervision is an important factor in skill development as reluctance to disclose dissatisfaction prevents them from asking for changes in supervision that might improve their learning. The trainees’ perception of an unequal dynamic in the relationship with their supervisor and the worry that raising concerns might damage that relationship resulted in issues and concerns not being discussed. As problems in their supervision remained unresolved, trainees continued their sessions potentially not eliciting the support they felt they needed, thereby negatively impacting on learning.

Discussion

This study drew on the experiences of 11 CBT trainees aiming to understand how supervision aids their CBT skill development. In doing so, different aspects of supervision experience were explored and four main themes emerged from the data which will be discussed in turn.

Linking theory to practice was the key theme developed from the data, suggesting that the most important role of supervision is to help trainees bridge the gap from classroom teaching to the practice with their patients. Specifically, the use of audio recordings, discussing formulations, modelling and role-play were of greatest value in helping trainees apply their theoretical knowledge to practice.

Through supervisors’ feedback on audio recordings of live clinical sessions, trainees were clearer regarding their own performance and were alerted to aspects of their practice requiring development of which they were previously unaware. These findings are in line with the view that listening to recordings is important in examining a trainee’s progress as it allows for specific feedback to be provided and previously unnoticed issues to be identified (Liese and Beck, Reference Liese and Beck1997; Newman, Reference Newman2010). Trainees reported that recordings accurately convey what happened in session, which supports recent recommendations of using audio recordings instead of relying on trainee memory/self report (Barnfield et al., Reference Barnfield, Mathieson and Beaumont2007; Sudak et al., Reference Sudak, Codd III, Ludgate, Sokol, Fox, Reiser and Milne2015).

Through discussing formulations supervisors helped trainees apply the CBT framework to their practice. Specifically, where trainees struggled with complex cases, discussing formulations helped them regain confidence and gain a different perspective. These reports are in keeping with De Stefano and colleagues’ study (De Stefano et al., Reference De Stefano, D’Iuso, Blake, Fitzpatrick, Drapeau and Chamodraka2007) on counselling students’ experiences of clinical impasses, where providing alternative perspectives in supervision was found to help students overcome feelings of incompetence that were triggered by complex cases. Importantly, where students felt unsupported, supervision added to their feelings of incompetence.

Further comparisons can be drawn with the study of McClain et al. (Reference McClain, O’Sullivan and Clardy2004), where psychiatric residents’ ability to competently generate formulations was found to be improved by discussing formulations with a faculty member. These findings illustrate the importance of providing different perspectives to trainees in developing their formulation skills.

Modelling and role-play helped trainees become more flexible and versatile in their practice. Specifically, being given example phrases and playing out scenarios with their supervisor helped trainees learn alternative approaches in responding to their patients. These results are in line with the long-standing view of the utility of role-play and modelling for skill development (Baum and Gray, Reference Baum and Gray1992; Milne and Reiser, Reference Milne and Reiser2017), and with studies demonstrating that these methods are the most effective in encouraging trainees to incorporate new approaches and behaviours (e.g. Bearman et al., Reference Bearman, Weisz, Chorpita, Hoagwood, Ward and Ugueto2013, Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling and Fennell2009).

Some trainees reported that their supervisor used an approach in supervision that mirrored CBT. This approach was experienced as more reflective and explorative than other forms of supervision. Trainees felt that the CBT approach placed more emphasis on their learning and encouraged them to develop their own ideas.

The positive impact of reflective practice on CBT skill learning has previously been demonstrated (Bennett-Levy and Padesky, Reference Bennett-Levy and Padesky2014) and studies have found that a lack of reflective opportunities in supervision is negatively experienced by trainees (Reichelt and Skjerve, Reference Reichelt and Skjerve2001). The findings of the present study further support the view that CBT tools are equally useful in teaching as they are in clinical practice, and that CBT supervision structure should mirror CBT practice (Beck, Reference Beck, Falender and Shafranske2008; Sudak et al., Reference Sudak, Codd III, Ludgate, Sokol, Fox, Reiser and Milne2015).

Having a supervisor with perceived expertise in CBT gave trainees more confidence, helped them move away from previously learnt non-CBT modalities, and increased their understanding of whether they delivered CBT correctly. These findings are consistent with a recent survey of counselling and psychotherapy students, which found that the ‘supervisor as expert clinician’ was necessary for trainees’ professional growth (Ladany et al., Reference Ladany, Mori and Mehr2013). Moreover, it is in line with the view that expert supervision is critical during the training period as it allows trainees to solidify their competence (Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Abramowitz, Furr, Kalsy and Riggs2003; Milne, Reference Milne2009).

As Schoenwald et al. (Reference Schoenwald, Sheidow and Chapman2009) found, supervisors’ adherence to specific modality therapy treatment principles predicted greater modality adherence by their supervisees, demonstrating the importance of supervisor expertise, consistent with the findings of this study.

Less positively it emerged that trainees were reluctant to provide negative feedback or constructive criticism to supervisors as they feared that appearing critical could affect their course marks and the relationship with their supervisor. This was compounded by the power dynamic that trainees perceived, which led to the belief that it was not a trainees’ place to provide feedback to supervisors. These findings are corroborated by Gray and colleagues’ study (Gray et al., Reference Gray, Ladany, Walker and Ancis2001) on counselling trainees’ experiences of negative events in supervision, which found that most trainees who had experienced conflict in supervision did not disclose their dissatisfaction. The reluctance of participants to share negative feedback echo’s Ladany’s (Reference Ladany, Mori and Mehr2013) findings on non-disclosure. Recent work focusing on using tools to encourage regular structured feedback, such as the Supervision Adherence and Guidance Evaluation (SAGE) – a scale for rating competence in CBT supervision (Milne and Reiser, Reference Milne and Reiser2014) aims to reduce the sense of rating or criticising the supervisor and re-focus on skills and methods required to maximise the benefit of supervision. It would be of interest in future research to explore if use of the SAGE altered trainees’ perceived inability to provide negative feedback to supervisors and re-balanced the identified power dynamic in therapy training supervisory environments.

Limitations

It is recognised that a volunteer convenience sample may bias results in that we do not have access to the views from the other trainees in this cohort who may have different perspectives on supervision. Also the group of participants were at varied stages of training in CBT so had different amounts of experience of CBT-specific supervision. However, the participant sample came from a range of professions all with significant professional experience and were all engaged in CBT supervision so the data should be broadly representative in that sense. Indeed, coming from a range of different professional backgrounds, some participants had previously experienced different forms of supervision. These differences in experiences may have affected how trainees perceived supervision in the CBT training context. However, as the aim of the study was to identify how trainees experienced supervision specific to the learning of CBT skills, it is expected that trainees were able to report on what was valuable to their learning, irrespective of their previous experience. A further limitation is that the trainees’ reports represent their perceptions of supervision and are therefore not an objective measure of their learning experience and skill acquisition.

Future research

It would be of considerable interest to compare trainee’s perceptions of supervision with training outcomes, such as pass rates and measures of CBT competence, e.g. CTS-R (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001). We hope to test this in a future paper using the training programme outcomes and a larger sample size. It would also be helpful to replicate this preliminary study with a larger sample and control for the relative experience of both trainees and supervisors in order to see if our findings can be replicated. Another future step would be to compare training outcomes for those supervisors who had engaged in specialist CBT supervision training with those who had not. Finally it would be of interest in future research to explore if use of structured feedback tools for supervisors, e.g. the SAGE (Milne and Reiser, Reference Milne and Reiser2014), altered trainees’ perceived inability to provide negative feedback to supervisors and re-balance the identified power dynamic in therapy training supervisory environments.

Conclusion

The findings of this study highlight the importance of supervision in helping trainees bridge the gap from classroom learning to clinical practice. Applying CBT theory to cases that diverge from ‘textbook’ examples can be very challenging for trainees as they start out in their practice. A range of supervision methods, specifically feedback on audio recordings of clinical sessions, discussing formulations and role-play and modelling, helped trainees improve and understand their own practice, focus on important aspects of a complex case, and become more flexible as therapists. The CBT approach to supervision is a valuable aspect to trainees’ learning as it helps them reflect on their work and provides them with action plans to work towards. Having a CBT expert as a supervisor is important for trainees’ ability to shift previously learnt therapeutic modalities from their practice, and in helping them focus on the principles of CBT. As trainees may not always feel satisfied with their supervision, it is vital that they feel that they can voice concerns they might have. Supervisors need to be aware of the power dynamic within supervision and ensure that their trainees feel able to give feedback to them where appropriate. The findings of this study therefore provide evidence of key areas that should be focused upon in CBT supervision within a training context to maximise learning opportunities. The methods of learning most effective in supervision highlighted in this paper should then be mirrored in CBT training and CBT supervision training programmes such that the opportunities for most effective learning can be utilised for maximum benefit to competency based learning in CBT.

The present study therefore offers a unique preliminary insight into CBT trainees’ experiences of the supervision process and provides direction for CBT supervision foci, methods, process and content that may also contribute to content of CBT and CBT supervision training programmes.

Acknowledgements

With many thanks to the trainee cognitive behavioural therapists who took the time to be interviewed and contribute to this project.

Financial support

This project received no financial.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statements

The authors confirm that they have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Full ethical approval for the project was provided by University of Edinburgh and the original version of this paper was submitted in dissertation format as part fulfilment of MA in Psychology by the first author. Ethical approval was deemed not to be necessary by NHS R&D as the project was considered to be a training programme evaluation as opposed to formal research.

Key practice points

(1) CBT supervision is particularly valued when the supervisor is received as modality expert.

(2) CBT supervision is a key mode of promoting theory to practise links in a training context.

(3) Feedback to CBT supervisors is challenging and should be addressed early in the supervisory process to encourage collaboration.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.