Introduction

Self-reflection has been shown to be important for therapist development (Laireiter & Willutzki, Reference Laireiter and Willutzki2003). It is particularly relevant to the development of interpersonal skills. Self-reflection can be promoted through supervision, schema questionnaires, focused training, reflective practice groups and self-practice of cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) (Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006; Bennett-Levy & Thwaites, Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Gilbert and Leahy2007). Formulation is a key CBT skill and this case report illustrates how formulation of client and therapist interaction may assist self-reflection and focus on interpersonal skills.

Bennett-Levy's (Reference Bennett-Levy2006) cognitive model summarizes therapist skills and how these develop. The model identifies the three systems used in skill development: declarative, procedural and reflective. The declarative system is comprised of factual knowledge, whereas the procedural system is know-how and skills that can be applied. The reflective system helps therapists to discern when and with whom to use knowledge and skills and can identify areas for their further development. Reflection uses meta-cognition where the therapist considers thoughts, emotions and actions either during or after therapy. Reflection allows therapists to notice their client's reactions and to then adjust behaviour. It also allows therapists to reflect on their own attitudes; interpersonal, technical and conceptual skills; and rules for when skills and knowledge are deployed.

Within Bennett-Levy's (Reference Bennett-Levy2006) model, interpersonal skills are key to therapist development and require reflection. Interpersonal skills partly rely on noticing the impact of sessions on the client and on oneself, which could be explored through discussion of process issues in therapy (e.g. Bennett-Levy et al. Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001). These skills require attention to the client's behaviour, knowledge of the client's beliefs and attitudes, in addition to knowledge of the therapist's own schema. A poor therapeutic alliance may arise from lack of attention to interpersonal factors or a lack of interpersonal skills. This is highly relevant to therapy as poor alliance predicts higher rates of treatment failure (Weck et al. Reference Weck, Grikscheit, Jakob, Hofling and Stangier2014). Therapist beliefs can affect the course of therapy (Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006). Therefore self-reflection on these beliefs and interactions between client and therapist can enhance interpersonal skills.

Self-reflection may be generally useful; however it might be particularly indicated when working with distressing material and cross-culturally. Working with traumatic material can provoke intense emotional responses in therapists, strongly held beliefs about how distress is experienced, strong beliefs about how distress should be managed, and an intense desire to help and rescue (Bennett-Levy et al. Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001; Brown, Reference Brown2008). Reflection is required to be aware of these responses. Working effectively cross-culturally also demands cultural competence. Cultural competence is the consideration of cultural differences leading to adaptation in services to accommodate different beliefs, attitudes and norms (Betancourt et al. Reference Betancourt, Green, Carrillo and Ananeh-Firempong2003). Self-reflection highlights one's own thinking errors and supports affect regulation (Vaughn, Reference Vaughn2010). Self-reflection may then enhance cultural competence, improve intervention and limit the personal impact of trauma work (Ruiz et al. Reference Ruiz, Gupta, Bhugra, Bhugra, Craig and Bhui2010).

Self-reflection is central to therapist development, particularly interpersonal skills and it may enable therapists to manage the emotional impact of their work, in addition to promoting cultural competence. Given the importance of reflection to interpersonal skills, reflecting on interactions between client and therapist may be particularly valuable. Self-reflection can be achieved through using CBT therapy skills (Kennerley et al. Reference Kennerley, Mueller, Fennell, Mueller, Kennerley, McManus and Westbrook2010). Formulation is a core CBT skill. The therapist may formulate their own thoughts, behaviours and feelings, thereby facilitating self-reflection. This can help not only in planning interventions but also to explore the impact of work on themselves (Bennett-Levy & Thwaites, Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Gilbert and Leahy2007).

CBT formulations typically focus on an individual's thoughts, feelings and behaviours but not explicit details of interpersonal interactions. Understanding interactions in therapy can explore the process of therapy and promote development of interpersonal skills. Simple ‘antecedent-belief-consequence’ (ABC) style formulations can chain together interactions, with the consequence of one person's formulation supplying the antecedent for the other's formulation. This has been used to explore barriers in treatment in psychosis (Chadwick, Reference Chadwick2006) and to formulate team responses to clients with risky behaviours (Meaden & Hacker, Reference Meaden and Hacker2010). This approach may be useful to promote self-reflection, which is particularly relevant with trauma and cross-cultural work.

This case study aims to provide a consideration of the interaction between a client's and therapist's (F.M. as therapist) beliefs and behaviour during the assessment and stabilization phase of trauma-focused CBT. The case study reports a treatment failure, where therapy was terminated during a stabilization phase. Exploring treatment failure can assist in the development of meta-competences and highlight areas for further development (Worrell, Reference Worrell, Whittington and Grey2014). The utility of simple ABC formulations to consider interaction, promote self-reflection and inform intervention is considered through the example of this case.

Case description

This study uses client and therapist ABC formulations relating to a particular case, as such brief details of the case, assessment and intervention are provided prior to outlining the method for self-reflection.

Informed consent was gained from the client, ‘Amir’, at the beginning of assessment, using a Farsi version of the service's standard consent form and discussed in session with the interpreter. Amir gave permission for use of his material for research, training and (anonymized) publication. Any identifying details have been altered or removed, while preserving the central details of the case and outcome.

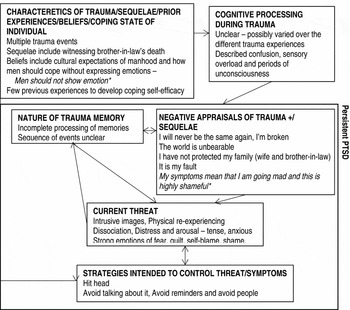

Amir was a 28-year-old Iranian male asylum seeker and survivor of torture. He had experienced multiple traumatic events, including several episodes of torture, a distressing journey to the UK and detention on arrival in the UK. His family's involvement in politics in Iran resulted in his own torture, his wife's torture and his brother-in-law's murder. He described significant post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, including dissociation with amnesia and flashbacks. Amir also described low mood, suicidal ideation and complicated grief reactions, with shame, guilt and self-blame that also relate to the complex nature of his trauma (Courtois, Reference Courtois2008). To provide contextual information, the formulation for Amir's distress is presented in Figure 1, based on the Ehlers & Clark model (Reference Ehlers and Clark2000).

Fig. 1. Case formulation for Amir. * Text in italics indicates elements of the formulation arising from the ABC formulations and reflections.

Planned course of intervention

A phased approach to PTSD treatment is recommended, with trauma-focused CBT as the first-line treatment (NICE, 2005). A three-phase approach to treatment is common (particularly for multiple traumas): (1) establishment of safety and stabilization, (2) trauma-focused therapy (e.g. reliving with rescripting) and (3) social reintegration (Herman, Reference Herman1997; Grey & Young, Reference Grey, Young, Bhugra, Craig and Bhui2010).

The NICE guidelines (2005) state that trauma-focused therapy should be conducted only when the client feels safe enough to proceed. Prior to this, work on safety and stabilization may be a necessary precursor to therapy, particularly where trauma-focused therapy would cause overwhelming stress if the client is unable to manage the arousal accompanying techniques such as reliving (Young, Reference Young and Grey2009).

Trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT) has been shown to be effective with asylum seekers and refugees, with a growing evidence base (e.g. Paunovic & Öst, Reference Paunovic and Öst2001; Nicholl & Thompson, Reference Nicholl and Thompson2004; Nickerson et al. Reference Nickerson, Bryant, Silove and Steel2011). TF-CBT can be challenging with multiple traumas, seen not only in asylum seekers and refugees but also in a range of other clinical populations, such as survivors of childhood abuse (Stallworthy, Reference Stallworthy and Grey2009). Developing a trusting relationship may present a greater challenge. There may be relationships between the trauma events, for example negative beliefs linking the events or shared triggers. This can mean formulation and treatment require greater consideration (Stallworthy, Reference Stallworthy and Grey2009). Multiple traumas may require more treatment sessions and although linked to lower successful treatment outcome, can still be successfully treated with TF-CBT (Ehlers et al. Reference Ehlers, Grey, Wild, Stott, Liness, Deale, Handley, Albert, Cullen, Hackmann, Manley, McManus, Brady, Salkovskis and Clark2013). Narrative exposure therapy (NET) was designed specifically for survivors of multiple traumas and involves techniques similar to CBT such as exposure and cognitive challenge (Schauer et al. Reference Schauer, Neuner and Elbert2005; Dossa & Hatem, Reference Dossa and Hatem2012). Briefly, NET involves the creation of a chronological account of biography with detailed reconstruction of fragmented trauma memories in order to achieve habituation (Robjant & Fazel, Reference Robjant and Fazel2010; Ertl et al. Reference Ertl, Pfeiffer, Schauer, Elbert and Neuner2011). NET has been shown to be effective with asylum seekers and refugees (Neuner et al. Reference Neuner, Kurreck, Ruf, Odenwald, Elbert and Schauer2009; Slobodin & de Jong, Reference Slobodin and de Jong2014). The clinician working with this population then has a choice of available therapies with an emerging evidence base for both TF-CBT and NET. Here, TF-CBT was planned.

Five sessions of assessment were completed with Amir, owing to the need for an interpreter, and the context of the intervention – working within a service that offers assessment of the client's medical, social, legal and psychological state and needs. Subsequently, stabilization work was commenced, focusing on grounding techniques and psychoeducation. This was because of Amir's high level of uncontrolled symptoms leading to very high arousal, significant stress experienced in his relationship with his wife and Amir's disclosed thoughts of suicide. A total of four stabilization-focused sessions are included in this study.

The first step of the treatment plan with Amir was to reach a level of stabilization where Amir was able to better self-soothe and manage the arousal in a safe manner. This was key to ensure Amir could safely go on to engage and manage the arousal that can arise during TF-CBT. The next planned step was to engage in TF-CBT, following published treatment outlines (Grey & Young, Reference Grey and Young2008).

ABC formulation method

Following assessment and initial formulation of Amir's current distress, I (F.M. as therapist) kept detailed notes during and after sessions. These notes captured my thoughts, feelings and behaviours as the session progressed and Amir's stated thoughts, and stated or observed feelings and behaviours. The notes alternated between my material and then Amir's material.

Simple ABC formulations were derived from the notes that captured the interactions. This was done after sessions and in preparation for supervision during a period of self-reflection after Amir withdrew from therapy. Following Meaden & Hacker's (Reference Meaden and Hacker2010) process, the client's consequences provided my antecedents, which then lead through my beliefs to my consequences, in turn providing antecedents for the client. Examples of the ABC formulations were selected for presentation on the basis of illustrating a chain of interactions and showcasing how this type of reflection can be used practically. These are shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. ABC chain formulations. Amir's sequences are shown in normal text, my responses are shown in italics. Potential activated schemas are shown in square brackets. The emotions that are underlined are hypothesized in the client, others were checked with him.

Course of therapy and outcome

Stabilization intervention began with psychoeducation regarding the impact of trauma on Amir's mood and thoughts. Guided discovery explored Amir's hyperarousal, linking this to his trauma experiences. The metaphor of a full bucket was used, naming his multiple stressors, to clarify why a small stressor could lead to an angry or distressed outburst. Strategies that might act as a small tap to reduce his stress were explored. Amir expressed doubt at this point in the usefulness of such strategies. We practised relaxed breathing and a sensory grounding activity, to help control the physiological arousal, provide a sense of control over his experiences and connect him with the present moment.

Amir missed an appointment and his friend called to explain a crisis episode where Amir had been unable to recognize his surroundings and his wife. At the next meeting, following initial denial, Amir went on to describe the episode. No trigger was identified. We worked together to generate hypotheses that explained the difficulties. Based on the hypotheses, the importance of remaining in the present moment was identified. Amir expressed that he wanted to get better and wanted to move faster. Despite a lack of time remaining in session, I responded by rapidly outlining basic grounding techniques and Amir chose an object (a marble) to help him distinguish past from present (as this object was newly acquired so grounded him in the present). Amir expressed a lack of hope and disbelief that I, or therapy, could help. This was discussed as a communication of the extent of his distress and a symptom of his low mood. At this point, I noted feeling particularly worried about my level of skill and experienced a significant amount of concern about Amir's wellbeing, increasing the demand I placed on myself to ‘do a better job’.

In the next session, Amir described access to anxiolytics (without GP prescription) and suicidal ideation. He explained his distress and disbelief that he could get better, having found other techniques unhelpful. He said he felt he was getting worse and not better, therefore no longer wished to attend. He then described wanting to write a letter ‘in case something happens’, which through discussion unveiled Amir was concerned he was ‘mad’ and felt his only option was suicide. Amir declined to answer several risk assessment questions and left the building. As his therapist, I felt greatly concerned as I had been unable to estimate the risk, rejected and as if I had failed. (For information purposes, this risk was followed up and statutory agencies were involved in Amir's care as appropriate at this stage.)

ABC formulations

The chained ABC formulations given in Figure 2 were seen.

Discussion

Formulation of my ‘ABCs’ in response to Amir's ABCs promoted self-reflection and provided a method to understand the interaction. The beliefs and interpretations interacted to create difficulties within the therapy. The formulation provided lessons about the relevance of therapist beliefs and suggests processes to be aware of in future work. First, I consider my own beliefs within the interaction, together with the schema evoked in both parties, with implications for improved practice. Throughout this, I highlight the lack of attention paid to the interpersonal system. Second, I briefly discuss the emotional impact of the work, highlighted by the ABC. Third, I consider the role of culture and how the ABC process highlighted this. Next, I apply basic CBT principles to generate alternatives to my beliefs. The usefulness of this simple ABC formulation process to promote reflection and therapist development is thus demonstrated.

My response to the client's vulnerability was elicited through the ABC formulation. I seemed to focus on self-critical thinking, which in turn altered my responses to the client and choices of intervention. My awareness of this behaviour was clarified through making thought records and building the ABC formulations. My self-criticism directed my attention at myself and my technical performance. This diverted me away from interpersonal skills. During this case, I was a final year trainee, working with severe trauma for the first time. It has been found previously that novice therapists tend to attribute difficulties to their own shortcomings (Haarhoff, Reference Haarhoff2006) and feelings of responsibility are common when working with trauma (Kennerley et al. Reference Kennerley, Mueller, Fennell, Mueller, Kennerley, McManus and Westbrook2010). The presence of the self-critical beliefs is therefore unsurprising. My response to this was to increase efforts to create change, which here was unhelpful. The ABC formulation then allowed me to understand that I am prone to this way of responding and therefore to be mindful of this in the future.

Considering schema, Figure 2 includes a brief reference to hypotheses about schema, here referring to high level sets of beliefs and strategies about the world and emotional expression. The ABC and formulation suggest that Amir is perhaps holding an ‘emotional schema’, not uncommon in PTSD (Leahy, Reference Leahy, Sookman and Leahy2009). In an emotional schema, emotions are paid significant attention and interpreted negatively. This is reinforced by processes such as rumination and avoidance and may be culturally informed (see below). I hold a ‘demanding-standards’ schema, with assumptions that I should be able to help clients, meet high standards and work efficiently. This entails discussion of emotional material, which I view as essential to achieving this goal. There creates an immediate mismatch.

The initial mismatch around our schemas and emotions may have created some ‘validation resistance’ (Leahy, Reference Leahy2008) for Amir. He experienced a need to for greater validation of his emotions, which I accepted as distressing yet to be expected and discussed. Conversely, Amir experienced these emotions as intolerable and difficult to discuss. Together with my demanding-standards schema, I sought to provide psychoeducation, information and intervention at a greater pace to address his concerns and provide ‘good’ therapy. My task orientation was mismatched with Amir, who continued to require validation of his emotions to a greater level. Indeed, the validation resistance may have activated my demanding-standards schema through my interpretation of this as evidence of my failure. Working through the ABCs at the end of therapy has allowed me to identify this mismatch and contributing factors more clearly.

Leahy (Reference Leahy2008) asks why clients and therapists are not smarter at noticing this sort of interaction, noting that such insight requires awareness of many factors, including the interaction, role-taking, inferences made and seeing the self as object in another's view. The ABC model allowed me to examine my behaviour as seen by my client and drew attention to the interactions. This allowed me to focus on the interpersonal skills that contributed to treatment failure. It is important to note that it is not possible to pinpoint this as a single factor in the treatment failure. Clearly, the skilled application of declarative knowledge and procedural skills in delivering an evidence-based intervention, such as trauma-focused CBT, is vital in addition to strong interpersonal skills.

Turning now to consider the emotional impact of the work upon me, the ABC process allowed me to explore not only my emotional state, but also the factors internally and within the interaction that led to this. Amir's story is highly distressing, and it is not surprising that this led to an impulse in me to work hard to help him alleviate his distress. Indeed, this is perhaps a very human reaction. Using the ABC identified schema allowed me to understand how I seek to manage my worry about clients – and this is often by increasing attempts to offer intervention. Generating alternatives using basic CBT techniques on the ABC interactions offers alternatives thoughts and behaviours (as discussed below). This allowed me to feel differently about the treatment failure, seeing learning and options rather than unfixable failing and to think about working on my own ability to sit with my own distress in response to clients’ stories.

Next, the role of culture demands attention. Considering the client's and therapist's own culture and how they might work together is recommended (El-Leithy, Reference El-Leithy, Whittington and Grey2014). The ABC formulation highlights some differences in my and Amir's beliefs, which may be culturally mediated. As a white, British, middle-class, female therapist, to me the expression of emotion is highly acceptable and to be encouraged. In my own culture, mental health, including specific difficulties such as PTSD and its treatment, are widely discussed in the media and in my more immediate socio-cultural experiences. Furthermore, I am aware of the extent to which my own life has been protected from the kind of trauma Amir has experienced – my culture is one of relative safety. Amir is a middle-class, educated Iranian man of roughly the same age as me. During assessment, he described his culture and family culture, as not talking to each other about emotions. Research into emotional expression in Iran supports this, for example research with children revealed Iranian children were more likely to report concealing emotions than children from The Netherlands (Novin et al. Reference Novin, Banerjee, Dadkhah and Rieffe2009). He described having no experience of his own or others’ mental health difficulties and was not familiar with ideas such as ‘PTSD’. Evidence suggests that stigma towards and self-stigma by those with mental health difficulties in Iran is high (Lauber & Rössler, Reference Lauber and Rössler2007; Ghanean et al. Reference Ghanean, Nojomi and Jacobsson2011). The consideration of culturally mediated beliefs about emotional expression gives rise to hypothesized prior beliefs and appraisals of the trauma that can be incorporated into reformulation. Figure 1 includes these elements to showcase the utility of this self-reflection in developing case conceptualizations.

Amir entered the interaction tracked in Figure 2 with the belief it is not OK to talk about his distress. I offered some basic validation and encouragement around this and, through my cultural lens and distracted by self-focused demanding standards, I assumed this would be sufficient. I moved on to psychoeducation and information, which may have implicitly reinforced for Amir the idea that it is not acceptable to express emotions. I was focusing on offering technical and conceptual skills, partly as I was working with my first client who was a survivor of torture and I was in clinical training. I believed it important to provide information about PTSD and attempt to instil hope about treatment, based on my view of the situation. I was out of step with Amir, as we had mismatched fundamental assumptions about emotional expression and the meaning of ‘mental illness’. Amir displayed concern about being ‘mad’, which held a different meaning to each of us in terms of the level of stigma and consequences. I missed the opportunity here to use and develop my interpersonal skills to address this mismatch.

The ABC formulation shows the interactions that took place in detail, which can be understood through a variety of lenses, including looking at schema but also looking at culture more generally. For me, this method facilitated the ability to step-back and explore the interactions and draws attention to the importance of considering culturally mediated expressions of distress, important for culturally competent practice (Brown, Reference Brown2008). The simple method then led to reflection and supervision discussions offering alternative ways of responding and learning for me. For example, the formulation highlights a need to improve the therapeutic relationship and attend to Amir's communications that he did not feel were understood. Greater empathy, active listening and validation of distress may have allowed me to address the difficulties and facilitated Amir's engagement.

Alternative beliefs for me, as a therapist, can be generated. For example, one belief was ‘He doesn't like me as he is often quiet’. An alternative would be that ‘I do not know why the client is quiet’, therefore the behaviour could be to raise the issue with the client. Furthermore, I could use the client's beliefs as the antecedent rather than the client's ‘consequences’. For example, the client expressed the belief that he could not be helped. I could have focused on this communication, rather than the client's increased distress. I then may have engaged in a discussion about this belief, eliciting the accompanying emotions, instead of increasing discussion about the conceptual elements including psychoeducation. Finally, I had the belief ‘I need to do something else’. Self-reflection revealed that the ‘something else’ could be a greater focus on the interpersonal issues. Consideration of alternative behaviours is promoted through this reflection on therapist ABCs.

This case study has several limitations. The views of the ABCs are of course my interpretations. It may be possible through session recording and structured supervision to elicit alternative versions of the ABCs, perhaps with the view of a third person a different formulation would arise. There were of course multiple, complex interactions between myself and Amir, and this case study selects only a few. Further, these all relate to the difficulties in our work as this was of most relevance to me; however, there may be ABCs illustrating elements of our work that went well. The ABCs capture a small snapshot of Amir's and my beliefs. A broader consideration of schema may also be of relevance. The role of the interpreter has also not been considered, as some of Amir's beliefs may have related to the interpreter and my concerns about my performance were heightened by the presence of a third party in the room. Furthermore, although the interpreter was experienced, there may have been elements of his own beliefs and attitudes affecting the way in which he expressed Amir's and my words.

In conclusion, this case study demonstrates the importance of self-reflection and the utility of the ABC formulations to promote this. The chaining ABC mini-formulations allowed a conceptualization of the interactions using CBT theory. CBT focuses predominately on the individual; however, this chaining can help elucidate interactions. This method has potential use for helping therapists to be aware of patterns of responding and notice warning signs, to develop alternative ways of behaving through the use of basic CBT techniques and to be aware of the need to concentrate on interpersonal skills. The learning from self-reflection can then be applicable to the current case and more generally. ABC formulations are simple and can be done by the individual, as such this approach may be useful for integrating ongoing reflection and development into everyday practice.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the client for his input and for providing consent for anonymized data to be used for this paper. Thanks are due to fellow staff at Freedom from Torture for discussion and input.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. This study was completed as part of the first author's Doctorate in Clinical Psychology training at the University of Bath.

Declaration of Interest

None.

Learning objectives

-

(1) Self-reflection can be promoted by using simple ABC formulations to chain the interaction between client and therapist, using one person's consequences as the other's antecedents.

-

(2) These formulations allow a conceptualization of the interaction between client and therapist and may therefore point to areas for further skill and knowledge development.

-

(3) Standard CBT techniques can be used by the therapist and supervisor to explore alternative interpretations and consider alternative behaviours, which can then be tested and evaluated to help address barriers in therapy.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.