INTRODUCTION

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched by President Xi Jinping in late 2013, has been the most studied policy from China in recent years. A range of foreign observers have portrayed BRI as Beijing's imperialist ambition to achieve dominance (Economy Reference Economy2018), realize the “China Dream” (Miller Reference Miller2017), “entrap” recipient countries (Hoslag Reference Hoslag2019), and boost authoritarian values globally (Roth Reference Roth2019). Such geopolitical characterization has been popular among politicians and think-tanks in the United States (Pence Reference Pence2018; Russel and Berger Reference Russel and Berger2020), leading to policy responses that advocate “all society” and “all-government” resistance to China (U.S. Department of Defense 2019). Other observers, researching China's domestic politics and BRI projects, have concluded that BRI is China's globalization strategy driven by internal priorities (Ye Reference Ye2015, Reference Ye2019, Reference Ye2020), a spatial fix to address economic challenges (Jones Reference Jones and Zeng2019), or state capitalism led by state-owned enterprises (Zeng and Li Reference Zeng and Li2019) and local governments (Li Reference Li2020).

Furthermore, as scholars focused on the recipient countries, they found the host was often the driver of BRI projects and the host environment has shaped BRI implementation. Jonathan Hillman (Reference Hillman2020) explores different regions’ experiences with BRI throughout Asia, Europe, and Africa. Meg Rithmire and Yinghao Li (2019) explain how the Sri Lankan government was the driver of BRI projects there, and Erica Downs (Reference Downs2019) finds Pakistan was partly to blame for its BRI debt risks and environmental costs. Hong Liu and Guanie Lim (Reference Liu and Lim2018), David Lampton, Selina Ho, and Cheng-Chwee Kuik (2020), in particular, compare different BRI projects in Southeast Asian countries to show that home institutions have decisive roles to play, and the Chinese government has been more reactive and “adaptive” to different regions than was initially understood.

These studies have caught important aspects of the BRI, and yet they miss critical dynamics shaping China's state behavior. This article conceptualizes the Chinese state system as an integrated framework that accounts for fragmented actors driving BRI and resulting in contradictory effects, real or misperceived, in China and abroad. The framework has two theoretical underpinnings: firstly, the Chinese state is a tri-block structure, consisting of political leadership, national bureaucracy, and the government's economic arms (i.e., state-owned companies and local governments). Secondly, BRI is not a uniform plan but a process of multiple steps and stages. This state system helps explain why some scholars observe that geostrategic ambition has motivated BRI while others underscore domestic economic drivers. While BRI is a Chinese initiative, the recipient governments have often played decisive roles in specific projects.

Specifically, operating under the tri-block structure, the BRI process illuminates fragmented motives and policies: the leadership employed strategic rhetoric at its launch; bureaucracies formulated guiding policies; more pervasively, the economic actors largely implemented the BRI on commercial concerns. Therefore, focusing on different state actors, scholars have arrived at different explanations for BRI. For specialists interested in actual investment and effects, the pattern is relatively clear: despite the geopolitical rhetoric from Beijing, BRI has largely proceeded via commercial activities. Much of BRI's risks should be viewed and properly dealt with as consequences of the capitalist behavior under China's fragmented state.

The BRI process also shows that recipients have played important parts in choosing and executing BRI projects by working with different Chinese actors in the fragmented system. And when BRI projects generated political backlash and economic fallout in the recipients, external critiques have reached China's policymakers via multiple channels, forcing Beijing to adjust policies to address such external backlash. However, given the tri-block structure, Beijing's policy adjustment will not be sufficient to induce a fundamental change in Chinese capital behavior. A workable solution requires Beijing and the recipients to change market incentives facing Chinese investors under the BRI framework.

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic presented a challenge for BRI and for the PRC's efforts to sell it. Many doubted the BRI's ability to survive since some infrastructure projects were canceled or paused due to the pandemic and pandemic-induced debt issues. Meanwhile, China suffered significant financial losses, constraining its ability to commit resources to the BRI. Foreign opinion of China reached rock bottom, making recipients less likely to embrace BRI. The domestic framework in this article, however, draws a different conclusion. Firstly, BRI was motivated by China's national priorities in diplomacy and economy; as long as those motivations do not fundamentally alter after the pandemic, BRI is likely to continue. Secondly, BRI's implementation has expanded vested interests in China, involving key state actors. Those interests are not going away with the pandemic (Ye Reference Ye2021a). China's BRI projects are thus likely to continue, with necessary adaptation to the post-COVID world.

The rest of the article has three sections. The first section provides the “fragmented state” theoretical background and focuses on the state system governing China's major policies. It conceptualizes the tri-block state system and explains how different institutions and actors have contributed to China's policy fragmentation in BRI and other major policy areas. The second section draws a multi-staged policy process rooted in the state system, comprising initiation, implementation, and readjustment. This process applies to BRI but also other major policy programs in China. The section also addresses the extent to which fragmentation has continued in the current leadership.

The third section constitutes the primary empirical section and maps out the BRI process in detail. Firstly, the section illustrates that strategic, diplomatic, and economic challenges had empowered the leadership to launch the BRI. Then, during BRI formation, bureaucracies inserted their policy preferences and priorities. More important, at the ground level economic actors largely interpreted BRI according to commercial considerations. Thus, as a whole, while the leadership and bureaucracy promoted BRI in strategic and policy-planning languages, the implementation was largely commercial in nature. Finally, external backlash forced Beijing to recalibrate and adjust BRI policies. Again, given the tri-block structure, such policy adjustment would be inadequate unless it also involves a change in commercial calculations on the ground.

THE CHINESE STATE'S THREE BLOCKS

The literature on BRI has divided its focus on different parts of the Chinese state. Those that emphasize geopolitical motivations assume that China's leaders have sufficient control over the initiative and issue cohesive directives for BRI implementation. Explanations that focus on project-level analyses tend to observe profitability and business motivations behind China's state capital and local governments and the influence and input from the recipients. While these perspectives correctly depict aspects of China's BRI, they miss key features, particularly regarding the Chinese state's internal dynamics.

This article approaches China as a tri-block state system; it emphasizes the domestic logic of BRI while also complementing these other accounts. In this understanding, the political leadership determines the strategic rhetoric and mobilization of the initiative, but it does not control the policies to implement BRI or its specific projects. Second, the national bureaucracy, including financial agencies, provides guidelines and resources for BRI project implementation but does not have cohesive oversight over companies, local governments, and other actors in the actual project design and execution. Finally, BRI implementers—SOEs and local governments—have prioritized their profits and commercial gains in BRI projects, resulting in both intended and unintended benefits and risks. Thus, while Chinese state actors all have stakes in BRI, regarding actual implementation, the economic actors are decisive, and their commercial calculations have driven BRI projects in China and abroad.

This view into the complex BRI process reflects enduring and increasing contradictions in China's political economy in recent years. On the one hand, the political leadership has become more overbearing in shaping the national policy directions while largely keeping subnational and corporate autonomy during implementation. This pattern has been described as “grand steerage” by Barry Naughton (Reference Naughton, Fingar and Oi2020). On the other hand, fragmentation has continued in the state system and, in some areas, intensified at the subnational levels (Ye Reference Ye2020). Despite increasing power in the core leaders (particularly Xi Jinping), there remains a profound limitation to China's “party-state” capitalism, imposed by pluralized and globalized businesses in China (Pearson, Rithmire, and Tsai Reference Pearson, Rithmire and Tsai2020).

The fragmented state idea is familiar to scholarship on China's politics, ranging from references to “fragmented authoritarianism” in the 1980s (Lieberthal and Lampton Reference Lieberthal and Lampton1992) to entrepreneurial policy actors in recent decades (Mertha Reference Mertha2009). The application of the tri-block formula to the BRI has several advantages. Firstly, it captures interactions and fragmentation across and within the three blocks of state actors (as noted, the leadership, bureaucracy, and economic arms). Such analysis captures the whole state at different levels, rather than just center–local dynamics that have anchored other scholarship (Chen Reference Chen2018; Heilmann Reference Heilmann2018; Oi Reference Oi, Fingar and Oi2020). Secondly, the model shows how China's foreign policy around the BRI is bound up in domestic and local politics. Neither the leadership nor the heads of functional and subnational units have much control over policy implementation. In each phase of the Belt and Road Initiative, the process appears chaotic; the transition looks disjointed from one step to another. Nevertheless, at the systemic level, after a completed policy cycle, there is a kind of “chaotic cohesion” in the BRI, where refined and readjusted policies help address new challenges facing the country and reinforce the importance of the initiative to the state.

THE LEADERSHIP

Without question, the Chinese Communist Party is the sole ruling political party in the PRC, with ideology and organization thoroughly in the party leadership's hands. However, the leadership's relationships with the national bureaucracy and with subnational and corporate actors are more complex than party control over all others. The tri-block formula helps illustrate these actors’ separate functions, their exercise of power, and mutual interactions in the state system. It explains why policy fragmentation is deep-seated in the single-party-dominated system and, paradoxically, how cohesion is somewhat maintained without overcoming structural fragmentation in the state. In the BRI, as explicated later, messages were controlled by the leadership and appeared cohesive and strategic, and yet the implementation was conducted by other state actors with divergent interests.

In Figure 1, the Chinese state's first block is the political leadership, which includes the heads of the ruling Chinese Communist Party: the top leader, Politburo members, and the Central Committee. The leadership's political power lies in control of organization, ideology, and information that influence all CCP members (McGregor Reference McGregor2010). As of 2019, the CCP had more than 90 million members, covering most central bureaucracy, local government, state companies, and government-affiliated research institutions and think-tanks. However, the CCP members who serve in functional bureaus are civil servants. They have gone through globalized education and succeeded in merit-based exams. Even in research institutions, these members need to pass recruitment tests based on the expertise required in their functional domains. Therefore, these CCP members may share the party affiliation with non-civil servant members, but they assume functional roles and professional expertise in making and implementing specific policies.

Figure 1. The Tri-Block State in China

Note: NDRC = National Development and Reform Commission, a super-ministry in charge of domestic economic planning, overseeing development efforts in local governments and different sectors; PBOC = People's Bank of China, the monetary bank that determines rates and money supply to commercial and policy banks; SASAC =State Assets Administration and Supervision Agency.

In principle, the leadership has the ultimate power to make the bureaucracy and the economic arms execute preferred policies, as shown in “direct power” lines in Figure 1. In practice, however, the leadership's control over policy content, not to mention implementation, is limited. Most policies in China do not originate from the leadership. Those launched by the leadership are typically motivated and composed by other state actors. Their implementation always falls in the hands of bureaucracies, local governments, and state companies (see “indirect influence” lines in Figure 1). These state actors have their own specific functional and economic goals to fulfill. They also have considerable latitude in deciding how and whether to implement a set of national policies, as top-down directives are often numerous and contradictory.

In Figure 1, the leadership block is led by the top leader, followed by Politburo Standing and Alternative Members (around 25 of them), and the Central Committee (roughly 200). In overseeing significant domestic and foreign policies, the leadership creates leading small groups (LSGs) that supervise and coordinate actions across different bureaucracies. The LSGs’ policy oversight varies, and unless its head is powerful and committed to the policy, LSGs’ supervision over implementation tends to be limited. LSGs also have limited staffing, and their policy expertise on the issues is relatively underdeveloped. Further, although LSGs have the authority to convene cross-bureaucracy conferences and collect information from different functions, they rely on cooperation from parallel agencies. For example, in the case of BRI, all its 24 LSG members came from other agencies and served as liaisons in the LSG. The chair of the BRI's LSG, although a permanent member of the Politburo, has a broad portfolio of power and responsibilities, and not necessarily an exclusive and committed interest in BRI per se. Given that BRI involves so many actors in so many areas, the LSG's supervision is likely to be partial and limited.

Fragmentation seen in BRI policies is also frequently observed in the relationship between the leadership and the other government blocks (bureaucracies and the economic arms). Weidong Liu (Reference Liu, Dunford and Liu2014) finds abundant “vertical” and “horizontal” divisions in China's governance structure, which results in what he calls “consultative authoritarianism” in China's national and regional planning. Ang (Reference Ang2016) has established that Beijing's top-down policies provided “directional” but not obligatory guidelines in China's localities. In analyzing the Western Development Program and China Goes Out, Ye (Reference Ye2020) showed systematic fragmentation separating top-down rhetoric and actual implementation by local state and non-state actors. Even under leader Xi Jinping, Naughton (Reference Naughton, Fingar and Oi2020) confirms “grand steerage”—providing general direction, but not top-down planning in China's major economic policies recently.

To summarize, political leadership in China theoretically has the supreme power to decide critical issues and directions facing the nation. Its power comes from the CCP-controlled organization, ideology, and information used to align behaviors in the bureaucracy and other state units, so that they appear cohesive, even if they are not actually so. Beyond the political power, the leadership delegates policy issues, such as design and execution of specific policies to bureaucracies, local governments, and companies. In this process, fragmentation persists in policy interpretation and implementation by diverse actors.

In recent decades, the tri-block structure has been relatively stable in China. Still, the state blocks’ interactions have changed in response to changing circumstances in China and abroad. The relative power dynamic between the leadership and other state actors, between Beijing and localities, has swung from one end of the pendulum to another. In the BRI process, fragmented bureaucracies empowered the leadership to launch BRI in 2013, which mobilized SOEs and local governments into unchecked commercial behaviors. External backlash then strengthened the influence of bureaucracy in making regulatory measures to rein in such economic actors. The tri-block structure also predicts that, without changing commercial incentives or market conditions, such regulatory efforts alone are unlikely to change Chinese capital's behavior.

THE BUREAUCRACY

In Figure 1, the second block consists of the national bureaucracy, with the State Council at the top and dozens of ministries, governing the country from the capital. Professional bureaucracies have been the hallmark of East Asian countries during their high-growth eras (Haggard Reference Haggard2018). China's bureaucracies also conducted industrial planning, selecting “national champions,” and subsidizing specific sectors. Frequently, Chinese bureaucracies learned from and emulated successful policies from their neighbors (Ye Reference Ye2014). However, the bureaucracy has not featured centrally in the literature on the Chinese economy. China specialists have generally emphasized political leadership (Lampton Reference Lampton2014), state companies (Naughton and Tsai Reference Naughton and Tsai2015), and local governments (Heilmann Reference Heilmann2018; Oi Reference Oi, Fingar and Oi2020).

The bureaucracy is treated as one block in the state structure in the tri-block framework, equivalent to the leadership and economic arms. Such inclusion is warranted, as Chinese bureaucracies are state actors that can make economic and social policies in Beijing and then mobilize resources and power to influence local governments and business behaviors. Bureaucracies have ideas and interests that differ from the leadership and economic arms. They have a power that is separate from and checked by the leadership. Central bureaucracy has functional authority over local governments and companies, but more frequently, it depends on cooperation from these state actors to achieve operational goals.

Figure 1 shows those bureaucracies that are important to China's capital globalization and illustrates fragmentation inside the bureaucratic block and across other state actors. Like political leadership, the bureaucracy's relative power and its relationships with other state actors shift when circumstances in China and abroad change. Sometimes they have considerable cohesion and make policy decisions in their functions. Other times they are deeply divided and cannot impose intervention on society and the economy. In the relationship with political leadership, sometimes they act more cohesively, and other times they are stuck in an impasse or resistance. Yet, despite such variations and internal fragmentation, China's bureaucracies consist of a robust and autonomous state block with overarching information and expertise in governance, making new policies and policy adjustments during implementation.

Demonstrating bureaucratic functions and fragmentation, Figure 1 includes ministries and industrial agencies that influence China's outbound investment and BRI. Among them, three bureaucracies have general decision-making and regulatory functions regarding China's outbound investment: the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), and the Ministry of Foreign affairs (MFA). China's outbound infrastructure, state financing, and large-scale investments require step-by-step approval from all three agencies. In BRI, the three agencies drafted the national BRI guidelines in 2015 and 2019.

NDRC, MOFCOM, and MFA embody different priorities, interests, and functions in the state system. NDRC is mainly responsible for domestic industry, deciding national economic priorities, and fulfilling national growth targets in China's localities. It is the most powerful agency guiding China's outbound globalization, yet it is also predisposed toward the domestic economy and internal priorities. MOFCOM handles foreign economic relations and negotiations of international economic treaties. After it orchestrated China's tumultuous and successful negotiation to join the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2000, however, other agencies, localities, and companies vastly expanded their globalization independent of MOFCOM supervision. MFA manages China's diplomatic relations, political ties, and leadership visits to foreign countries. In recent years, it has become more active in formulating and pushing economic projects to facilitate diplomacy. However, MFA does not have autonomous financial resources, or institutional power over other state actors, and cannot execute economic diplomacy forcefully.

Other than the above intra-bureaucracy fragmentation, the leadership exercises the ultimate check on bureaucracy's rule-making and regulatory authority over state's economic arms (Block 3). The Party Organization appoints and promotes bureaucrats, managers of state companies and local governments, making the regulators (bureaucracy) and regulated (SOEs and local governments) parallel units in the CCP. The state companies and local governments can have equal or higher ranks in the Party Organization than the regulating bureaucracies, leading to ineffective regulatory oversight. Because of the divided party-state structure in Beijing, the reporting lines in the state system are simultaneously “narrow,” in small bureaucratic cells, and “broad,” accountable to the leadership writ large (Weidong Liu Reference Liu, Dunford and Liu2014). Due to Beijing's separation of powers, state actors in the localities and companies have considerable autonomy to focus on their own priorities, generating policy fragmentation.

Fragmented bureaucracies have led to peculiar policy outcomes in China regarding its outbound investment (Ye Reference Ye2020). On the one hand, they often fail to make decisive and coordinated policies regarding outgoing capital, even when market conditions demand policy change. On the other hand, they cannot control or regulate activities by Chinese companies across borders. Although the state has largely financed outward investment, bureaucracies have limited oversight on capitalists’ behaviors once they leave the country. In particular, in Figure 1, agencies like the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), Ministry of Finance (MOF), and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) have conducted “fragmented liberalization” without going through overarching bureaucracies and enabled more liberal rules to specific sectors, localities, and companies. Hong Kong, the global hub of finance and investment, served as the “parking” place for Chinese money subsequently invested elsewhere; for example, from 2001 to 2015, MOFCOM reported that three-quarters of China's outbound investment went to Hong Kong. In reality, a lot of it was destined for other recipients.

ECONOMIC ARMS

Finally, state companies and local governments comprise the third block in the system—the state's economic arms. The companies have considerable assets, allowing them the ability and incentives to construct globalization projects. Local governments have tax revenues bases, revenues from their SOEs, and land sales under their jurisdiction. They also have the autonomy and resources to decide how and how much to implement top-down guidelines. Therefore, although political power is in the leadership's hands, the economic arms are relatively free to interpret national policies according to their localized needs and opportunities. Besides, across China, local governments have very different capabilities and resources. Thus they interpret and implement the national policy quite differently in their jurisdiction.

In the BRI case, different localities came up with various projects and programs. These initiatives featured divergent actors, such as state companies, local agencies, and private companies. In particular, as Beijing's BRI rhetoric and policies were ambitious and vague, they imposed little direction on the localized implementation. As Haitao Yin, Yunyi Hu, and Xu Tian find, in their article in this issue, local governments and companies also face multiple and contradictory policy directives from Beijing. They can choose which orders to abide by and which to ignore in their BRI implementation, serving the immediate needs perceived by their local interests.

Given the tri-block state in China, the models to characterize BRI as geostrategy, global infrastructure, or commercial activities are all incomplete, if not wrong. The reality is that, while the leadership launched the initiative in strategic rhetoric and bureaucracies inserted their policy ideas on globalization, it was the commercial actors (SOEs and local governments) that conducted investment and infrastructure projects in China and abroad. Nevertheless, when BRI resulted in economic fallout and political backlash, Beijing has been readjusting its rhetoric to address the adverse outcomes since 2017. The national-level adjustments are unlikely to suffice, however; rather, financial incentives and market conditions need to be changed on the ground.

THE POLICY-PROCESS ANALYSIS

Operating under the tri-block state system, China's globalization strategies (BRI and others) follow a complex policy process with multiple stages and steps. In each stage and step, the motivations, conditions and actors, and the ways they drive the BRI policy have varied in China. While the leadership employs geopolitical rhetoric in initiating a strategy, fragmentation exists at the bureaucratic level and even more pervasively during implementation by subnational and business actors. The result is a fragmented process in which the rhetoric, the announced policy, and the actual implementation are disconnected. The process is also cyclical, as external critiques result in a feedback loop that induces policy readjustment in Beijing without resolving the system's fundamental fragmentation.

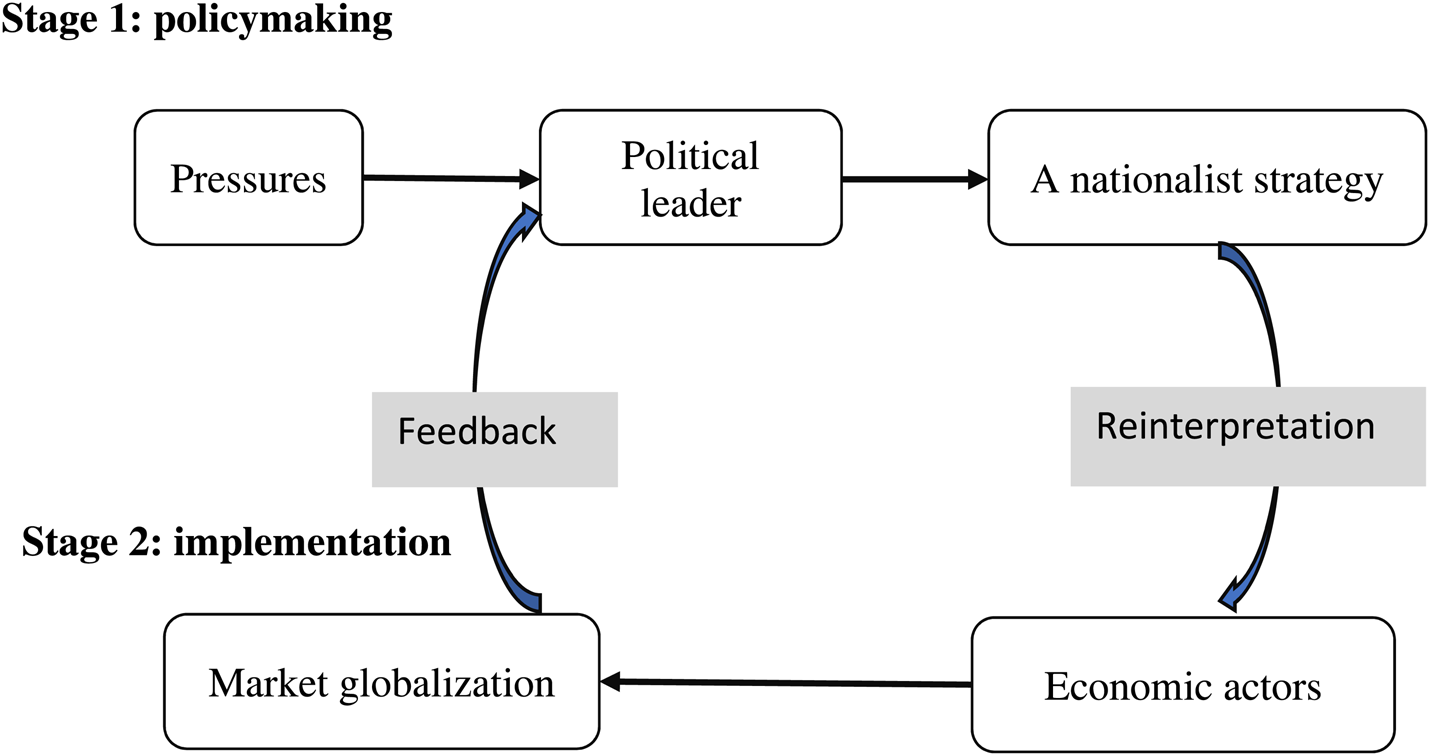

Figure 2 shows the process of BRI, with two stages and five steps. In the first stage, policymaking began, with economic, geopolitical, and diplomatic imperatives that required the state to respond with coordinated and forceful programs. However, the divided bureaucracies could not make cross-agency policy responses, forcing the leadership to announce the ambiguous yet ambitious initiative. Next, in the implementation stage, state economic actors played a central part, reinterpreting the policy, and pursuing globalization in line with their own economic interests. Finally, the outcomes of implementation, good or bad, were fed back to policymakers in Beijing and resulted in recalibration and adjustment of the BRI in political rhetoric and policy guidelines. This cycle is likely to be followed by fragmented implementation in which the effects, feedback, and limited adaptation continue.

Figure 2. The Policy Mechanism

At various moments in the process, observers from the outside witness different drivers but not the precise causation. For example, at the outset of BRI, they have observed severe challenges in the economy, diplomacy, and geostrategy in China, which required quick bureaucratic responses. However, due to fragmentation, the bureaucracy failed to rally support and resources to make coordinated policy responses. The bureaucratic impasse was thus a causal condition underlying the leadership's BRI announcements. Next, outside observers witnessed the strategy's launch and ambitious and ambiguous rhetoric employed by the leadership. They also observed extensive mobilization of and implementation by other state members (Block 2 and Block 3). What was missing from external observations were: one, bureaucracies inserted their own policies to address their preexisting functional challenges, and two, the state economic arms came up with BRI projects to serve their own interests.

In other words, looking at different points in time during the BRI process, scholars could observe different actors and activities. Still, the fundamental driver of the initiative and its implementation were rooted in the fragmented state. Bureaucratic fragmentation propelled the leadership announcement, and central fragmentation empowered state companies and local governments to conduct BRI implementation in their own ways. Why has BRI been so ambitious and ambiguous in rhetoric, creating this much external confusion? The cause was in the Chinese state system, with ambitious rhetoric helping mobilize the state actors and ambiguous content incentivizing bureaucracies and economic actors to benefit and jump on the bandwagon (White Reference White1998). Such duality in rhetoric and reality has been common in China. In the past, in the 1992 Southern Tour (Ye Reference Ye2014), the Western Development Program, and the China Goes Out policy, the leaders had also employed ambitious and ambiguous rhetoric to promote such national policies: ambition makes a strategy generally acceptable to other state actors, and ambiguity enables subnational and business actors to improvise their self-benefiting projects.

While policy-making was important, it was the implementation stage that demonstrated the drivers of BRI projects and effects on the ground. And this stage had multiple steps too. Entering implementation, the state's economic arms—local governments and state companies, with priorities in business expansion—interpret the strategy in their jurisdictions. Localized implementation can be positive, stimulating enterprises’ interest in global markets. It can also be harmful, increasing the financial and environmental risks in China's outbound investment. In the feedback loop, adverse outcomes are transmitted back to decision-makers in Beijing, resulting in recalibration and adjustment in policy rhetoric and guidelines.

In the Chinese system, external critiques are particularly important for pressuring policy adjustment in Beijing. The tri-block system embodies many entry points for the external backlash to enter China and pressure points for leadership and bureaucracies to readjust the strategy. On the one hand, external information and critiques can flow from popular media, scholarly and policy forums, diplomatic settings, and think-tank reports in China. On the other hand, different interests and institutions in the state system pick up various external information to enhance their BRI roles and influence. National bureaucracies tend to enforce institutional control and oversight over commercial activities by state companies and local governments. Political leadership is also inclined to rein in unproductive projects to enhance its national image and political legacy. Thus, severe external backlash forces Beijing to adjust rhetoric and policies overseeing the BRI. Again, given the fragmented state structure and economic actors’ dominance in implementation, national-level recalibrations need changes in financing and market conditions to make a real difference on the ground.

What about the Chinese state under Xi? Western observers have widely viewed that President Xi Jinping had amassed so much power that fragmentation in favor of local governments and local companies no longer existed in China (Minzner Reference Minzner2018; Lardy Reference Lardy2019; Schuman Reference Schuman2021; Blanchette Reference Blanchette2021). Indeed, plenty of evidence exists to show that Xi has more power than his predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. When he assumed the leadership position in 2012, he launched the nationwide promotion of the “socialist core values.”Footnote 1 Starting in 2019, he promoted a campaign (“not to forget your historical missions”) to mobilize and discipline the CCP members.Footnote 2 Currently, he leads the country's efforts to work toward the two “centenary goals,” enriching society and rising on the world stage. Can we still argue that fragmentation persists under Xi? Can bureaucracies, local governments, and companies still have the flexibility to interpret and implement major programs announced by Xi?

As long as it exists, the tri-block structure predicts fragmentation in China's state system and BRI's dynamic policy process. Empirical investigation of policy matters under Xi has supported continual fragmentation in China (Ye Reference Ye2020; Lampton, Ho, and Kuik Reference Lampton, Ho and Kuik2020). Particularly, analysis of China's globalization needs to be separate from the discussion of Xi's political power in elite politics. While Xi has concentrated power in the party organization, ideology, information control, the military, and foreign policy, making himself the “chairman of everything,” the BRI process has been profoundly fragmented. As shown later, bureaucratic fragmentation had compelled the BRI's birth, and after the launch economic actors fragmented BRI implementation in their diverse jurisdictions.

The reality remains that, while Xi promoted BRI through strategic and political rhetoric, giving rise to BRI's external reputation as an “emperor's project” (Economy Reference Economy2018; Hillman Reference Hillman2020) at the bureaucratic level, the State Council has most forcefully pursued “industrial capacity cooperation” and mutual connectivity projects (Ye Reference Ye2020). Still, on the ground BRI projects demonstrate diverse, and mainly commercial, motivations by SOEs and local governments, defying Beijing's geostrategic rhetoric. In other words, the process illustrates that various policy actors with different motivations have shaped China's outbound capital. Such behavior of Chinese capital is not going to change under Xi's rule. Unfortunately, while unchecked commercial behaviors were largely responsible for emerging risks to the recipients, external critics have focused on Beijing's geostrategic motivations and state-dominance in the projects. An effective approach should instead integrate actions across the three blocks, pressuring changes in Beijing and in the local recipients.

BRI'S DRIVERS AND PROCESSES

This empirical section establishes the tri-block state framework and how the multi-staged policy process has operated over the life of the BRI. Figure 3 synthesizes the main steps of BRI and leading actors during each step. The analysis shows that the divided bureaucracies had faced severe challenges in 2013, forcing the leadership to launch BRI at the year's end. During the ensuing political mobilization, bureaucracies and policy professionals inserted various ideas and proposals into the BRI, expanding the strategy's broad appeal to state actors in Beijing. These two steps—launch and expansion—comprised BRI's policymaking. The implementation stage was conducted by state companies and local governments, which promoted their commercial considerations in devising and executing BRI projects.

Figure 3. The BRI Process in China

Fragmented state actors have had competing goals, and the fragmented process sent mixed signals to the recipients. For example, the economic actors have diverged from the leadership's strategic rhetoric in their commercial operations abroad. Diverse state motivations have generated political and economic backlash of different natures. Sometimes BRI resulted in political backlash from the recipients, as the latter were afraid of China's geopolitical expansion; at other times BRI projects resulted in development risks due to commercial behaviors on the ground. Both types of adverse effects have created a feedback loop in the BRI process and resulted in Beijing's efforts to recalibrate and readjust BRI's guidelines and implementation. The effectiveness of such adjustment depends on whether the regulations can alter commercial calculations on the ground, however, and in that process the recipients have just as much influence as the Chinese state.

BRI'S LAUNCH

Fragmentation has marked the whole cycle of the BRI. Before the leadership announced the initiative in late 2013, bureaucracies had faced grave challenges in foreign policy and the domestic economy. They had policy proposals to address these challenges in their functional areas, but they could not coordinate resources to implement the policies or to impose them on other state actors. Specifically, there were challenges from three fronts. In diplomacy, China's relationships with neighboring Asian countries had been difficult, ranging from Kazakhstan to Mongolia to Indonesia. In the military and security, China's maritime disputes with other Asian countries and with the US were intensifying. And in the economy, industrial overcapacity was severe across China and an economic recession was incoming. As SOEs and local governments faced pressure to cut down production and close plants, large-scale unemployment was expected, and social stability was in danger (Ye Reference Ye2019).

The functional bureaucracy and policy professionals proposed thoughtful, practical proposals to address these challenges. In addressing diplomatic friction, the MFA and diplomats advocated increasing China's infrastructure investment in Asia as a means to build common interest and improve relationships, broadly called “infrastructure diplomacy” (Zhu Reference Zhu2013). To address US-led geopolitical containment in maritime Asia, China's strategists proposed a “China goes west” rebalancing, directing Beijing's strategic efforts to continental Eurasia (Wang Reference Wang2011). However, for either infrastructure diplomacy or “go west” rebalancing to work, the diplomats and strategists would have had to secure coordination and support from other state agencies. And more importantly, they needed to have strong financial backing from the state capital and local governments. As explained, neither diplomats nor strategists had the power or mechanism to push for such high-level coordination. Nor did they have any meaningful influence on decisions at the state companies and subnational government levels.

In the economic realm, industrial overcapacity had grown since 2008, following China's massive stimulus plan to counter the global financial crisis. By 2012, industrial overcapacity had swept the country, reaching a level considered unsustainable by Beijing's technocrats. The “Chinese Marshall Plan,” a proposal to finance overseas investment and infrastructure to help Chinese industries go global, was popular among Beijing's economic policy circles (Jin Reference Jin2012), but it generated criticism from domestic social groups, who charged that the Chinese Marshall Plan was wasting money abroad (Ye Reference Ye2020).

In short, pre-BRI, Beijing faced real challenges in diplomacy, geopolitics, and the economy that required speedy and coordinated responses from the state. Unfortunately, bureaucracies and policy professionals had ideas but no power to impose broad overarching policies. President Xi's two announcements on the BRI received immediate and extensive cheers from bureaucrats and think-tank scholars who quickly got on board. Strategically employing the ambitious and ambiguous slogans, previously paralyzed bureaucracies were revived, and they churned out ideas, programs, and projects to implement the BRI strategy. Their affiliated think-tanks rapidly published and promoted policy ideas in line with these moves. They helped define BRI as enhancing China's connectivity with other countries in five areas: policy, trade, investment, infrastructure, and culture, incorporating main state and societal groups in the initiative.

EXPANSION: STAGING AND MOBILIZATION

In the policy cycle (Figure 2), the leadership's launch of the policy is an important step in the strategy, without which an overarching national strategy is impossible. However, the strategy's significance and contents are largely shaped by the expansion and interpretation by bureaucracies and other state actors in China. Within two years after Xi's announcements about BRI, the central agencies, policy specialists, local governments, and SOEs jointly expanded the leadership rhetoric into a comprehensive national strategy. During this process, the ambitious rhetoric was followed by careful stage management in Beijing, and the ambiguity led to different groups’ participation (for their own good).

After the leadership's announcement, there was a period of building top-level consensus in Beijing. In November 2013, the administration convened the “Periphery Diplomacy Work Meeting,” attended by representatives of the entire Communist Party, state bureaucracy, and ambassadorial appointees in neighboring countries. It established consensus to build infrastructure linkages with Eurasian countries in the BRI framework (Swaine Reference Swaine2014). The NDRC, MFA, and MOFCOM began to publicize the BRI and develop ideas and proposals for implementation. Finally, BRI was endorsed both at the Third Plenum of the 18th Communist Party Congress in December 2014, and in the Annual Government Report to the National People's Congress in January 2015.

During this period, major newspapers and journals in China began to publish think-tank research supporting the BRI. Specialists affiliated with various bureaucracies seized the opportunity to promote their policy ideas. Publications associated with the MFA, for example, advocated free trade areas and economic corridors, consistent with their ideas of economic diplomacy (Li Reference Li2014). Those affiliated with the NDRC, on the other hand, underscored the establishment of industrial parks and infrastructure projects abroad to help relieve manufacturing overcapacities in China (Jianchao Liu Reference Liu2014; Yang, Guo, and Yao Reference Yang, Guo and Yao2014; Kong, Tian, and Zhang Reference Kong, Tian and Zhang2014). Those with interests in western border security emphasized BRI's strategic significance and how it would revive China's traditional preeminent place in the region (Chen Reference Chen2015).

In short, the bureaucracy, previously failing to impose government-wide responses to the challenges they faced, could “use” the leadership rhetoric and BRI to promote their existing policies. For example, strategists used BRI to pursue the “go west” rebalancing; diplomats used BRI to promote China's infrastructure abroad; economic technocrats used BRI to help China's industries expand globally to ease overcapacity. More actors interpreted BRI flexibly to cover all directions (Africa and Latin America, for example) and almost all issue areas (tea and tourism included). Doing so, they result in a “coordinated voice” in the central government. But “coordinated” voices do not resolve state fragmentation, and different agencies continued to pursue and prioritize their own preferences. Ever ambitious and ambiguous, BRI thus intensified fragmentation in the implementation stage, as state economic arms took the strategy into their hands. The following pages describe implementation by state capital and local governments separately.

IMPLEMENTATION BY STATE CAPITAL

With top-down political mobilization and yet no specific policy directives, the state's economic arms (state banks, SOEs, and local governments) implemented BRI in ways that worked for their economic ideas and business needs. Some large SOEs proposed projects that were infeasible in the near term and attracted little real investment. Some proposed projects were in the name of BRI but, in substance, mainly served the SOE's business needs. For example, in 2015, China Railways committed a $200 million investment in Malaysia to establish its regional headquarters (Lin Reference Lin2016). This was precisely the same project the SOE had been planning for a couple of years. Similarly, China Construction invested in a landmark building in Cambodia, making it a BRI project in 2016. Shanghai Bao Steel created an online portal to increase foreign sales, submitting it as its BRI project (He and Wang Reference He and Wang2016). From 2014 to 2016, many BRI projects were continuations of former aid programs in South Asia and Southeast Asia (Ye Reference Ye2019).

Following the BRI's launch, there was a sharp increase in China's overseas financing and investment in 2016–2017. Yet, the patterns of state financing were similar to state financing before BRI. For example, the Export-Import Bank of China (EIBC) had been mandated to support the Chinese industry to export since 2005. With the BRI, EIBC sponsored new projects and loans abroad to help Chinese producers and service providers expand globally. The other big state financer is China Development Bank (CDB), a leading infrastructure investor before the BRI (Chin and Gallagher Reference Chin and Gallagher2019). In the name of BRI, CDB had made more large-scale investments and led infrastructure financing in the BRI countries. CDB's projects were mainly railways, nuclear energy, hydropower plants, large shipping ports, and digital infrastructure. CDB's investments had profit motivations while helping China's state companies expand global business in the long term (Downs Reference Downs2016). This pattern has been consistent in BRI too.

At BRI's launch in 2013 the political leader announced the creation of the Silk Road Fund (SRF) and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as new financiers for BRI implementation. However, SRF, with a $40 billion fund, and AIIB, pooling $100 billion from members, had financing ability much smaller than China's overall outbound financing. Furthermore, SRF and AIIB had developed different institutional patterns and financing principles. But both organizations demonstrated their institutional interests as representative of what their funders wanted, not instruments for China's geopolitical agendas. SRF, in particular, was profit-driven. It openly stipulated that the priority of its lending was to ensure safe and long-term returns on investment (Li Reference Li2016). AIIB became a multilateral investment bank in 2016, having 66 original members and expanding to 100 in recent years. Most AIIB funded projects had collaborated with the World Bank and Asian Development Bank and concentrated in relatively stable and promising markets. India, a notable BRI resister, was the dominant recipient of AIIB loans. Again, SRF and AIIB are small players in China's financing abroad, and they reveal institutional interests common to other sovereign funds or multilateral banks.

State capital's implementation of BRI demonstrates 1) continuity in drivers and behavior patterns from pre-BRI globalization, and 2) most SOE projects have followed preexisting overseas networks and business planning. BRI has mainly helped state companies expand or improve their investment projects. In the name of BRI, state financiers worked closely with SOEs and government agencies in selecting and executing overseas projects. In this process, the banks and SOEs have focused on their investors’ interests rather than Beijing's geopolitical strategy.

IMPLEMENTATION BY LOCALITIES

In China, local governments have resources, incentives, and the autonomy to implement—or not—national guidelines. When they do, they often adopt very different measures and programs. This has also been the case with regards to the BRI. On the one hand, local governments have extensively implemented BRI, enhancing its domestic and external potential. On the other hand, local governments’ motivations are local, including helping companies in their jurisdictions and, in recent years, stabilizing the impact of China's slowing growth. Due to different economic structures and priorities, China's local governments have interpreted BRI differently, and have improvised with a wide range of BRI projects. What is clear, however, is that they have mostly conducted BRI to serve local commercial interests, whether or not those interests are in line with central policies. Such behavior has stimulated investment and stabilized economic activities in the localities; but it might have also aggravated financial and environmental risks at the local level.

This section focuses on four localities, Chongqing, Ningbo, Wenzhou, and Urumqi, to showcase the localized BRI implementation in China. Chongqing, in western China, had predominant SOEs in the local economy, and its BRI implementation focused on two directions (Ye Reference Ye2020). First, the city started a “3+N” scheme to help SOEs expand globally. Chongqing's Export-Import Bank, MOFCOM, the Chongqing Foreign Trade Group (the largest SOE in the city) all work with other SOEs to explore overseas markets. Second, SOEs spun off small and new firms in new sectors to generate quick returns. Here, the Chongqing Foreign Trade Group founded YuXinOu E-commerce. Drawing on the China–Europe Railways brand, the e-commerce company imported high-end consumer goods from Western Europe to sell to customers in western China. The inbound e-commerce business was a rapid commercial success in the city, but it did not facilitate the BRI's intent to promote Chinese goods abroad.

In the eastern city Ningbo, the local government identified its priority to upgrade industry and improve the city's global profile. Its BRI projects demonstrate such goals. First, the city launched the Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) Consortium, with an annual goods expo from CEE countries. The city's calculation was straightforward. Once CEE became an international group, and Ningbo hosted the goods expo, the city would become more visible and attractive to multilateral companies in high-tech manufacturing and services sectors. Ningbo hosted the first China-CEE Goods Expo in 2019, serving as the business consortium for BRI's multilateral organization “17+1” (China, 16 CEE countries, and Turkey). Second, the Ningbo government sponsored the creation of the Silk Road Maritime Shipping Index, rivaling the Baltic Index, a global shipping index, and in 2016, it managed to insert the Silk Road Maritime Index in China's thirteenth Five Year Plan. Lastly, Ningbo expanded and upgraded its newest special zone, the Plum Mountain New Area, which became Zhejiang's Belt and Road Experiment Site in 2017.

In southern China, the city of Wenzhou had a predominantly private economy. Its BRI projects were nationally renowned and were led by private entrepreneurs. The Belt and Road Goods Expo was created by a private entrepreneur, who secured the endorsement from five central agencies in Beijing. The other BRI project was orchestrated by the city's largest power device manufacturer, which built a new production site in Xi'an, the Silk Road Economic Belt's origin city. Wenzhou entrepreneurs had followed the leadership's trips abroad, to Pakistan, Cambodia, and Indonesia. Commercial logic had driven Wenzhou's BRI projects and entrepreneurs’ participation in the strategy. For example, the BRI Expo was held annually in Italy and designed to help Wenzhou producers sell products in the European market.

BRI's influence on local development was also evident in Urumqi, a city in China's western border area and a major checkpoint on the Silk Road Economic Belt. As the largest and the capital city in Xinjiang, Urumqi had aggressively pursued development initiatives to attract investments from other parts of China. For years, it had applied to Beijing for permission to construct a tariff-free zone in the city, but it failed to get approval. In 2015, after the BRI's launch, the city submitted its zone application in the name of BRI. This time, it got a quick approval. And within months, the city expeditiously finished constructing the new zone, with a large customs building, transport hub, and residential real estate. In addition to the zone, Urumqi used BRI to sponsor development forums, improve local infrastructure, and revamp the city's landscape to attract investment and tourism.Footnote 3

Localities’ BRI implementation shows that local governments have actively and proactively leveraged BRI to achieve their developmental goals. These goals differed across the localities, and therefore local BRI featured a variety of projects and programs. The process also shows that local governments have worked closely with SOEs, banks, and central agencies, enhancing their long-term networks in the state system. Therefore, local implementation has reinforced BRI's commercial tendency and reflected the broad appeal and sustainability of the strategy in China. In other words, while Beijing promoted BRI as a diplomatic and political initiative, the strategy's real support and motivations in the state system were commercial and self-motivated interests of different state actors writ large.

EXTERNAL BACKLASH

BRI's launch and implementation reflected different interests and policy actors in China, but its repercussions were extensively felt outside the country. Some commercially motivated projects did not meet common global standards for social and environmental inclusion and assessments (Russel and Berger Reference Russel and Berger2019). Bo Kong and Kevin Gallagher's article in this issue shows China's external finance and BRI projects, in particular, have concentrated in energy and resources sectors that have severe environmental externalities. In Pakistan, China's energy projects were mainly coal-powered and raised concerns about environmental risks in CPEC (Downs Reference Downs2019).

In addition to such external backlash due to unwelcome development effects, the backlash against BRI was also generated by China's strategic rhetoric in promoting BRI and “BRI fever” exhibited by Chinese actors during the implementation stage. Outside China, the fear of BRI as Beijing's “economic statecraft” to penetrate recipient countries’ independence and strategic resources proliferated in recent years (Li Reference Li2020). After China took over Sri Lanka's Hambantota Port for a 99-year lease in 2018, following the host government's failure to serve its loans from China, the charge of BRI as Beijing's “debt trap” reached a climax in the region and the world.

To be sure, such external critiques have been qualified by in-depth studies of BRI projects in recipient countries. In Sri Lanka, Rithmire and Li (Reference Rithmire and Li2019) found the host government had initiated China's Hambantota Port investment, and host-nation politics shaped implementation. They also point out that the Chinese investor, China Merchants’ Group, had long been headquartered in Hong Kong with a corporate history older than the PRC.Footnote 4 In Pakistan, Downs (Reference Downs2019) confirms that the coal-powered plants were preferred by the host government and local politicians, as such plants were cheaper to build and quicker to finish, and created more jobs. In Southeast Asia, comparative evidence was compelling that recipients, not China, largely decided BRI projects’ origin and execution (Lampton, Ho, and Kuik Reference Lampton, Ho and Kuik2020).

Nevertheless, BRI's “reputation deficit” resounded in China, and policy communities in Beijing commonly felt that BRI projects had tarnished China's international image and undermined its soft power (Zhang Reference Zhang2020). A study at the State Council-affiliated Development Research Center found that, in 2018 alone, thousands of reports were published on BRI in the United States, and most of them were highly critical (Zhang Reference Zhang2020). In many countries, both BRI or non-BRI, public opinion on China and Chinese capital has deteriorated sharply in recent years, narrowing Beijing's diplomatic maneuverability in the region (Acharya Reference Acharya2020). Drawing on such anti-China political and popular discourse, the US and its allies launched the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy (FOIP), which gained momentum as a counterweight to BRI. Through FOIP, the Quad alliance—the US, Japan, Australia, and India—formed diplomatic narratives critical of China and offered competitive bids for infrastructure projects in the region.

Facing such heightened external backlash in 2018–2019, what would China's policy actors do? How should Beijing respond? Should BRI die a quiet death, as Minxin Pei provocatively argued (Reference Pei2019)? Or should it be pursued with more force (Wang Reference Wang2020)? This article shows that BRI was motivated by policy imperatives to address geostrategic, diplomatic, and economic challenges in China, and was conducted by important state actors such as central agencies, state banks, SOEs, and local governments. Neither the policy needs nor the policy actors are going away because of external criticism and challenges. Instead, external critiques have made their way into the Chinese state, pressuring them to adapt and recalibrate the style and methods in promoting the initiative in Asia and beyond (Erie Reference Erie2020).

FEEDBACK AND ADJUSTMENT

How have the feedback and policy affected China's BRI, given that it was the leadership's initiative? Like the fragmented system that has enabled diverse policy actors to interpret and implement BRI based on their commercial calculations, the system has also facilitated information flow from outside China to policymakers in Beijing, forcing them to react. Feedback channels included policy exchange at different levels, information flows in specific sectors, and unfettered online materials in open sources. Through these channels, BRI's external criticism was transmitted back to government agencies in Beijing, and in response, the bureaucracies recalibrated BRI and promoted new regulations to oversee its implementation. However, given the tri-block structure, new bureaucratic regulations depend on SOEs and local governments’ follow-through on the ground.

Indeed, feedback and adjustment have accompanied the process of BRI, as the central bureaucracies continuously seek to regulate commercial behavior by Chinese capital. In 2015, for example, to warn Chinese companies against risky projects and address foreign concerns about geostrategic motivations, NDRC (2015) stipulated that, “[we] must insist on companies as the main actors and market as the driving mechanism. [We] must follow international norms and economic principles; the companies are responsible for their own decisions, returns, and the risks.” In 2016, MOFCOM started to publish annual social and political risk assessments and held training programs for China's outbound investors. However, due to state fragmentation, Beijing's regulatory bodies could not exercise effective control and oversight over BRI activities conducted locally or abroad.

Paradoxically, increasing external resistance has enhanced the role of central agencies in BRI. In particular, in the running up to major global events in Beijing, external critics’ impacts were the greatest. In early 2019, leading up to the Second BRI Summit, the Beijing bureaucracy was open and receptive to foreign input and suggestions. NDRC, in particular, strengthened the Third-Market Cooperation Mechanism in China's BRI, forming inter-governmental working groups, arranging cooperation between Chinese and western MNCs, and inviting joint sponsorship with multinational institutions (Zhang Reference Zhang2020). In settling the debt repayment issue in Pakistan, Beijing involved the IMF.

In mid-2019, as the second BRI Summit was held, statements and documents from the Summit showcased political and bureaucratic recalibration. The leadership, changing from the earlier rhetoric of “the project of the century,”Footnote 5 underscored green and sustainable development, as well as cooperation as the key to achieving “high quality” BRI construction. Furthermore, the leadership repeatedly argued that BRI aimed to facilitate the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDB).Footnote 6 At the bureaucratic level, NDRC joined the United Nations agencies to publish “One Belt One Road Green Lighting Action Initiative” and “the Belt and Road Green and High-Efficiency Cooling Action Initiative.” Such initiatives promoted clean energy and green technology, addressing the environmental concerns of BRI projects.

Addressing external critiques on predatory lending, China's Ministry of Finance published “the One Belt One Road Sustainable Debt Analysis Framework” and pledged to improve BRI countries’ debt servicing ability and achieve sustainable and inclusive development. China's Commercial and Industrial Bank published the first Belt and Road Green Bond at the Summit. MOFCOM arranged conferences and activities that involved exchange and joint investment plans between Chinese and foreign companies. The Ministry of Science and Technology announced innovation exchanges with BRI countries that would include 5,000 people in five years. China's Environmental Protection Agency was committed to training 1,500 officials in BRI countries and establishing technology exchange and diffusion centers along the Belt and Road.Footnote 7

At the second Belt and Road Summit, the academic exchanges between China and BRI countries increased. The Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) announced scholarships to graduate students from BRI countries. With the partnership with the World Bank, legal scholars in China started the BRI Joint Legal Study Program, focusing on anti-corruption training to companies operating in BRI countries. Specialists representing China, international organizations, business communities jointly published the “Beijing Initiative on Clean Silk Road.”

These policy readjustments show that Beijing was aware of and concerned about the external backlash against BRI implementation. Different agencies came up with measures in their domains to address these concerns, and bilateral exchanges between China and BRI partner countries had a significant boost. The idea “BRI 2.0” was circulated in 2019 and was expected to lead to more moderate and institutionalized BRI in the next stage (Erie Reference Erie2020). However, in early 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic broke out, and BRI's future was once again debated. Some questioned its survivability after the pandemic, and others highlighted its triumphant expansion in the post-pandemic world (Ye Reference Ye2021b).

Following the BRI framework here, Ye (Reference Ye2021a) found that neither BRI's death nor dominance would be the likely future. Instead, China's policy discussions continued to argue that BRI addressed China's geopolitical, diplomatic, and economic challenges. Chinese policy actors—SOEs, local governments, and national agencies—continued their globalization during Covid-19, while adapting to new realities in the post-pandemic world. Thus far, BRI's policy emphasis has been on “softer” projects, such as public health, crisis management, and the digital economy. BRI's implementation in 2020 has featured scientific communities, internet-enabled companies, and trade via rail routes from China to Europe and other BRI countries. Once the pandemic is over, infrastructure connectivity is likely to revive, with digital infrastructure projects taking more salience than before.

The feedback and adjustment, shown at the second BRI Summit and in the aftermath of the Covid-19 outbreak, are informative of BRI dynamics, resilience and vulnerabilities included. It is an important step in the BRI process, driven by external critiques and led by Beijing's bureaucracy. Nevertheless, to make an actual impact it needs a complementary transformation of conditions shaping commercial actors in China and abroad. Feedback and adjustment at the policy level in Beijing are likely to have limited impact on the ground, while adjustment to change incentives for investors can profoundly affect BRI implementation in the future. For that to happen, the Chinese state and the recipients have to play complementary roles.

CONCLUSIONS

Publications on China's BRI have been abundant and divided; but the general thinking in the literature underscored China's strategic control over its outward state capital. This article conceptualizes the Chinese state as three blocks, the leadership, bureaucracy, and economic arms, and unpacks the BRI process into different stages and steps. It finds that once we formulate the state into different blocks of actors and map out BRI into processes, the strategic state model fails to capture the main dynamics of the BRI and diverges from realities on the ground.

The Chinese state has exhibited profound intra- and cross-block fragmentation in the tri-block structure, with critical impacts on policymaking and implementation. In BRI's genesis, bureaucratic fragmentation contributed to the leadership's launch of the strategy to respond to pressing imperatives facing the country—economic, diplomatic, and strategic challenges. Following the leadership's launch, the fragmented system then allowed bureaucracies and economic actors to formulate and interpret BRI according to their own ideas and interests. Statements and measures by central agencies in BRI confirmed continuity in bureaucratic preferences and policy measures before and after the initiative: specifically, strategic need to deescalate US–China rivalry, improving diplomacy through infrastructure and connectivity, and expanding Chinese economy abroad. Subnational actors and local BRI projects demonstrated that implementers had followed local interests, sometimes at odds with national motivations, as shown in this article and in the article in this issue by Yin, Hu, and Tian.

In the face of ambitious rhetoric by Chinese leaders and aggressive implementation by Chinese capital, foreign observers have formed strong doubts and resistance to BRI projects, particularly since the 2017 BRI Summit. Such external backlash was partly motivated by geopolitics, as Audrye Wong describes Australia's case in this issue. Some pushback was due to genuine concerns about sustainable development in BRI countries. External criticism and concerns pressured Beijing to readjust its BRI rhetoric and implementation. As shown during the feedback phase, China's technocrats, with help from global institutions and specialists, rolled out arrangements to ease external concerns. However, such measures’ effectiveness critically depend on a complementary change in commercial calculations on the ground.

In conclusion, we can make three broad observations. First, the geopolitical drivers of BRI have been overblown. The BRI originated from the context that China faced severe diplomatic and economic challenges. At the same time, functional bureaucracies failed to form coordinated responses, forcing the leadership to announce the strategy with geopolitical rhetoric. Once entering implementation, commercial interests on the ground have prevailed in specific projects and investment decisions. However, outside China, geostrategic concerns have been exacerbated by Chinese leadership's need for domestic mobilization and the hostile rhetoric in the recipients, as Wong finds in this issue.

Second, Chinese companies, operating under the fragmented state and state financing, have resulted in financial risks, environmental disruption, and the lack of social inclusion in some BRI projects abroad, as many external critics pointed out. Although the host countries have just as much to blame, such outcomes have caused political tensions in the recipients and created a geopolitical backlash against China. However, such costs should be seen as driven by these companies’ commercial behavior abroad rather than by China's “strategic” state. And they should be appropriately dealt with Beijing based on this understanding.

Finally, the fragmented structure also allows feedback and external information to enter policymakers in Beijing and help them readjust implementation in its capital globalization. The BRI process shows that bureaucratic adjustment had been continuous. But, when major global events were being held, such as the BRI Summit II, Beijing's response to external feedback and regulatory adjustment appeared the most effective. However, given the fragmentation between Beijing's rule and implementation on the ground, such regulatory adjustment will have limited impacts unless the market conditions are also changed for Chinese investors going global.

Beyond BRI, the globalization of Chinese capital has been expanding rapidly in the last decades and will continue to be a force to reckon with. Compared to other and earlier globalizing capital—from the US, Europe, and Japan, Chinese capital has been embedded in a distinct set of home institutions. It is likely to behave differently from other capital sources. Global specialists need to understand the Chinese state's inner workings, particularly the relationship between the state and state's economic arms, to evaluate Chinese investment and infrastructure's immediate and long-term effects abroad.

The other articles in the special issue elaborate on the tri-block state and policy process and focus on specific actors and their behaviors. Kong and Gallagher's investigation of industrial regulators, energy financiers, and major companies sheds light on how the bureaucratic-industrial complex works in influencing China's external behavior. Yin, Hu, and Tian examine opportunistic behaviors by China's local state-business nexus and show how these local actors’ commercial choices have had deleterious environmental costs, not outside, but inside China. Shi and Siem study perceptions and realities in China's investment projects in Zambia, demonstrating how China's investment behavior, shaped by politics and institutions at home, contributed to the “reputation deficit.” Audrye Wong finds China's domestic politics and business behaviors in Australia led to deep suspicion and anti-China backlash. Together, these articles offer important insights into the Chinese state and business behaviors, as well as the reactions and perceptions in the recipients. It is clear that the China-side drivers and recipients-side feedback are likely to continuously interact and reshape China's globalization trajectory in the BRI and beyond.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author thanks Kevin Gallagher, William Grimes, Bo Kong, and John Ravenhill for useful comments on early drafts, and Stephan Haggard for his suggestions during the final-draft stage.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Research on China's Belt and Road initiative was financially supported by Boston University's Center for the Study of Longer-Range Future and Smith Richardson Foundation.