Changing Attitudes Towards Female Voters Before the January 1919 Elections

In November 1918, the newly established Polish socialist government enfranchised every citizen above the age of twenty-one, regardless of sex; women of all nationalities and ethnicities in the Polish territory were now able to participate in their first elections to the Polish parliament, scheduled for the 26th of January of the following year. Male political leaders soon realized that female votes were key to their parties’ success and began exploiting women’s newly won right. As many men had been deported to German labor camps during the war or joined the new Polish army and engaged in the ongoing military operations after November 1918—men in military service were excluded from voting—women constituted the majority of voters in many parts of Poland, particularly in large cities such as Warsaw, Kraków, or Łódź (Malec Reference Malec2009; Fuszara Reference Fuszara, Pawilka and Zakrzewska-Manterys2008). Before the First World War, and throughout the nineteenth century, women in the partitioned Polish territories had been involved in different forms of resistance to the occupying governments, which determined their roles as those preserving the traditional values that came under threat after the partitions. Through teaching of the Polish language and history, and reproducing these values within their families, women ensured the survival of Polish culture and a Polish nation that had no independent territory (Żarnowska Reference Żarnowska2014; Fuszara Reference Fuszara, Pawilka and Zakrzewska-Manterys2008).Footnote 1 The introduction of suffrage in 1918 provided women, for the first time, with the opportunity to directly participate in shaping the country’s future, however, since they had little agency, they had to align themselves with the existing political parties to increase their chances of effective political participation (Ilski Reference Ilski2018).Footnote 2

The central issue on the political agenda was the position of the national and ethnic minorities as, in 1918, Poland became a multi-ethnic and multinational state.The two major political parties emerging after the war promoted contrasting visions of democracy in independent Poland. The Polish Socialist Party (PPS, Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, in 1926 transformed into the Independence Camp or Sanacja) led by Józef Piłsudski, promoted the idea of a “spiritual community,” a return to the founding principles of Poland-Lithuania, where different national and ethnic groups were connected by shared historical and cultural experiences (Davies Reference Davies1982). The National Democratic Party (SND, Stronnictwo Narodowo-Demokratyczne, popularly referred to as Endecja) led by Roman Dmowski, used the argument of “national interest” and “national solidarity” to exclude other national and ethnic groups, particularly Jews; anti-Jewish slogans served to rally Polish peasants and workers “against the socialists” (Weeks Reference Weeks1995, 54). In their criticism of the first leftist government of Poland, the right-wing nationalists evoked Jewish conspiracy theories by equating socialists with Bolsheviks, a discourse supported by the Polish clergy (on this, see Zamoyski Reference Zamoyski2015, 305), accusing the socialists of undermining the interest of Poles by filling in the positions of power with Jewish candidates. Dozens of political groups stood in those first elections—Christian, peasant, socialist, and nationalist—those that existed before the war, as well as new political groups, including a number of parties representing Jewish interests, each with their own program; yet, in reality, it was these two visions of a future Poland that were diametrically opposed (Ilski Reference Ilski2018). It is also this aspect that dominated the 1919 elections and much of the political debate of the entire interwar period.

This article explores the context of the January 1919 elections to the Legislative Sejm (Lower House of Parliament), focusing on the intense, wide-reaching campaign addressed to Polish women by the National Democratic camp and how anti-Jewish slogans were used to mobilize their participation. The National Democratic camp (ND, Narodowa Demokracja) included not only formal political groups, but also a number of economic, social, cultural, sport, and women’s associations supportive of ND’s national ideology (Dawidowicz, Reference Dawidowicz, Dajnowicz and Miodowski2016). Footnote 3 Prior to the enfranchising law, ND was one of the biggest opponents of women’s political emancipation, but already by December 1918, the National Election Committee for the Democratic Parties overlooking the election within the nationalist camp established the Women’s Organization for National Elections (NOWK, Narodowa Organizacja Wyborcza Kobiet), later renamed the National Women’s Organization (NOK, Narodowa Organizacja Kobiet) (see Jakubowska Reference Jakubowska, Żarnowska and Szwarc1996; Maj Reference Maj, Kulak and Dajnowicz2016), which was tasked specifically with attracting female voters (Ilski Reference Ilski2018; Kotowski Reference Kotowski, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2009). Until 1918, only a narrow elite of women engaged in politics, which fell outside the traditionally accepted female roles (Żarnowska Reference Żarnowska2014). Hence the appointed female leaders of NOK were to appeal to the wider population of mainly Catholic and ethnically Polish women of all social classes to take part in the elections, primarily as voters. The vigorous election campaign resulted in a high turnout of female voters, at 66.92 percent of eligible voters in Warsaw, 70.86 percent in Kraków, and 78.1 percent in Łódź—surprising numbers, given that women had had no previous experience of voting (Śliwa Reference Śliwa, Żarnowska and Szwarc2000, 52). Thanks to the contribution of NOK, the National Democratic Party secured 36 percent of the vote in the Kingdom of Poland (former Russian partition) alone, compared to PPS’s nine percent, a victory which undoubtedly can be attributed to women’s efforts, both as campaigners and as voters (Gawin Reference Gawin2015).

Described in the statute of the National Democratic Party as a “socio-cultural organization,” NOK was, from its inception, one of the many groups working under the auspices of the party (Bełcikowska Reference Bełcikowska1925; 66). Starting with the 1919 election, antisemitic tropes began to be systematically used in NOK’s election campaign materials, with typical slogans calling to protect the country from “enemies” (Kałwa Reference Kałwa and Passmore2003, 61; Gawin Reference Gawin2015, 231). NOK appeals to Polish women were printed in Gazeta Poranna (Morning Gazette) and Gazeta Warszawska (Warsaw Gazette), the ND-owned, nationalist-Catholic newspapers known for publishing content that portrayed Jews as a threat to the reborn Polish nation (Dawidowicz Reference Dawidowicz, Dajnowicz and Miodowski2016; Paczkowski Reference Paczkowski1983). NOK’s engagement with antisemitism was noted and criticized by members of other female organizations, such as The Union of Civic Work of Women (ZPOK, Związek Pracy Obywatelskiej Kobiet) (Jóźwik Reference Jóźwik2015). In addition to providing a divisive force within the Polish women’s movement, the radical nationalism promoted by NOK appeared to be a major cause of the lack of collaboration between Polish and Jewish female groups (Sierakowska Reference Sierakowska, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2009). A decade after the creation of NOK, the Jewish feminists gave a diagnosis of the women’s movement in Poland in the emerging post-WWI Jewish feminist press, noting the movement was not free of “passive and active” antisemitism (Ewa 1928, 6). The idea of active and passive antisemitism is extremely fitting in the context analyzed here, for it recognizes the diverse expressions of antisemitism in relation to the issues of political power and agency, while also distinguishing its more or less direct manifestations, such as calls for boycotts, spreading Jewish conspiracy theories, or limiting membership in NOK to women of Christian faith.

Considering Dmowski’s extreme anti-feminist and sexist outlook (Maj Reference Maj, Kulak and Dajnowicz2016; Gawin Reference Gawin2015; Wapiński Reference Wapiński1988),Footnote 4 this article proposes that women’s activism within the structures of ND was instrumentalized in order to promote the party’s ethno-nationalist vision of Poland and to win crucial votes of women at the time, when the party’s fate was being decided. The great participation in the 1919 election did not translate into a great female representation in the parliament, with only two women, Gabriela Balicka and Zofia Sokolnicka, becoming deputies for the National Democratic party and six women getting seats across other parties (Śliwa Reference Śliwa, Żarnowska and Szwarc2000). Notably, with each election, women’s political involvement dwindled, as did the party’s interest in female voters (Żarnowska Reference Żarnowska2014). Hence, the momentary turn to women by ND and the glorification of their role during the January 1919 campaign should be viewed as populist election rhetoric and not an acknowledgment of women’s equal political rights or an invitation to political partnership. At the same time, the women who joined NOK, and thus affiliated themselves with the ND’s political camp, became the major advocates of the party’s ethno-nationalist political agenda, including the spread of anti-Jewish propaganda beyond large centers such as Warsaw, Kraków and Łódź. The study of ND’s strategic inclusion of women and, simultaneously, exclusivist policies towards Jews during the election campaign, shows a tactical and gradual insertion of antisemitism across organizations sprouting in the newly established Polish state.

While women’s engagement with antisemitism in the post-WWI period has received mentions in various academic studies (Kałwa Reference Kałwa and Passmore2003; Gawin Reference Gawin, de Haan, Daskalova and Loutfi2005; Sierakowska Reference Sierakowska, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2009), no comprehensive analysis of the topic has appeared to date. The notable scholarly contributions on NOK’s history, Ewa Maj (Reference Maj, Kulak and Dajnowicz2016), Jolanta Mysiakowska-Muszyńska (Reference Mysiakowska-Muszyńska2015), and Robert Kotowski (Reference Kotowski, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2009), focus on NOK’s activity in the field of social work and their role as National Democracy’s mercenaries for nationalistic and Catholic values throughout the 1920s and 1930s. The literature’s silence on antisemitism within women’s groups could suggest a fear of undermining the hard-fought for achievements of women in the area of political and public life during and after the First World War. The new rights allowed women to emerge from their previously subjugated position, yet soon began to be used to oppress minorities. Significantly, NOK’s alignment with antisemitic ideology demonstrates the abandonment of women’s postulates from the months leading to the January 1919 elections and compromising women’s fight for equality by tainting it with ethnic nationalism. As Joanna Michlic observed, the anti-Jewish tropes had their “strongest political influence” in interwar Poland (1918–1939), leaving a lasting legacy that extended to the Second World War and beyond (Reference Michlic2006, 1). Given NOK’s prominence as one of the largest women’s associations in interwar Poland, it is important to begin a scholarly conversation about the role of women in the acts of anti-Jewish violence that intensified in interwar Poland and that until recently were described as “random” and unplanned (Kijek Reference Kijek2020). Moreover, the analysis of NOK’s activism should ignite a discussion about to what extent, if at all, did political and ideological loyalties determine women’s attitudes towards Jews during the Holocaust.

The Shifting Position of Women during the First World War

The women’s struggle for equal rights did not begin with Poland’s national independence. The introduction of suffrage in November 1918 marked the end of a long process of campaigning for equality by female groups of diverse profiles, some of them participating in combat and military operations in the First World War, some strictly feminist, and others actively engaged in the emerging political parties (Fuszara Reference Fuszara, Pawilka and Zakrzewska-Manterys2008). Although the movement was diversified across three different partitions, it is safe to say that the majority of women’s groups in Polish territories before the war had not focused strictly on suffrage rights, most likely due to the lack of the country’s independence and the freedom of association imposed by Austrian, Russian, and Prussian governments (Żarnowska and Szwarc Reference Żarnowska, Szwarc, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2008, 29–33; Kuźma-Markowska Reference Kuźma-Markowska, Sharp and Stibbe2011). Outwardly, women fought for a broadly understood betterment of women’s social position, hiding their emancipationist agenda; for example, female activists organised all-partitions women’s congresses disguised as literary events, which provided a platform of collaboration and an important impetus for consolidation of the women’s movement across partitions (Żarnowska and Szwarc Reference Żarnowska, Szwarc, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2008; Górnicka-Boratyńska Reference Górnicka-Boratyńska2018). The “woman question,” a debate around the position of women and attempts to reform the patriarchal idea of womanhood that began in Europe at the end of the nineteenth century, which fuelled the suffrage campaign, was overshadowed by the struggle for political and territorial independence; as a result, it was a marginal subject (Blobaum Reference Blobaum2002). At the same time, women’s role outside of the home increased due to political persecution and imprisonment of male members of the resistance movement, which made women assume roles previously reserved for men (Fuszara Reference Fuszara, Pawilka and Zakrzewska-Manterys2008).

Since much of women’s activism during the long period of Poland’s partitions focused on resistance and preservation of Polishness, thus, on the “patriotic mission,” women responded keenly to the patriotic calls on the eve of the First World War, when the majority of existing or newly formed women’s groups gave priority to Poland’s national cause (Dufrat Reference Dufrat, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2008, 114; Żarnowska and Szwarc Reference Żarnowska, Szwarc, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2008, 20). The leftist, progressive intelligentsia groups supporting Piłsudski, namely the female unit of the Riflemen’s Association (Związek Strzelczyń, est. 1912) and Women’s League for War Alert (LKPW, Liga Kobiet Pogotowia Wojennego, est. 1913), which in 1916 had nearly 16,000 members acting as the auxiliary force to Piłsudski’s Polish Legions, saw their primary mission in aiding the armed struggle for national independence (Kuźma-Markowska Reference Kuźma-Markowska, Sharp and Stibbe2011, 266)Footnote 5 The members of these organizations assumed that since they fought next to men for the country, they would later continue to run the country “on equal footing with men” once its freedom was secured (Dufrat Reference Dufrat, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2008, 126–127). The only exception was the feminist Union of Equal Rights for Polish Women (ZRKP, Związek Równouprawnienia Kobiet Polskich, est. 1907 in Warsaw), which gave priority to the demands of women’s equality in political life and full civic rights over the national cause (Kuźma-Markowska Reference Kuźma-Markowska, Sharp and Stibbe2011; Górnicka-Boratyńska Reference Górnicka-Boratyńska2018).

The greatest ever mobilization of women in the Polish territories during the First World War coincided with worsening Polish-Jewish relations in that period. National Democrats, who were gaining more and more influence on Polish society, argued that “the Jews, along with the occupiers of Poland, were acting to the detriment of the country” (Zieliński Reference Zieliński2009, 273). ND’s antisemitism, which they justified mainly by economic reasons calling for a boycott of the Jewish trade, quickly spread across other nationalist-Catholic milieux. Particularly the victory of the national parties, who used antisemitic slogans in 1918 council elections in the Austro-Hungarian occupied zone, encouraged antisemitism as an effective weapon in political warfare (Zieliński Reference Zieliński2009). For Catholic nationalists, the Jewish presence in Poland was a far more urgent matter than the introduction of suffrage, hence they stigmatised the female activists, who fought for gender equality (Blobaum Reference Blobaum2002). Moreover, women’s open demands for suffrage were met with the criticisms of the Roman Catholic Church, who accused women of radicalism, portraying their goals as “threatening the Church and the nation,” and calling on all Catholic women to abandon the organizations postulating for women’s enfranchisement (Dufrat Reference Dufrat, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2008, 128). As a result of the pressure of the Catholic Church as well as the extremely anti-suffrage outlook of the majority of the nationalist political establishment, many women shifted to the right of the political spectrum, giving in to ideologies tinted with antisemitism.

The attitude of the male leaders of all major political groups towards women’s suffrage was determined by their patriarchal outlook, noted Małgorzata Fuszara (Reference Fuszara, Pawilka and Zakrzewska-Manterys2008). The National Democrats generally shared a view that women’s place was at home and that the postulates of women’s political rights sabotaged the national postulates; prior to the war, women who supported the idea of women’s suffrage had been removed from Dmowski’s party (Gawin Reference Gawin2015).Footnote 6 Within PPS, which officially included women’s suffrage as a part of their programme of widely understood social emancipation of different classes, there was discrepancy between the public and private views, with many members having stereotypical ideas on gender roles, a view that proved a great obstacle to implement the emancipatory ideas in reality (Fuszara Reference Fuszara, Pawilka and Zakrzewska-Manterys2008). Even Piłsudski, the PPS leader, generally perceived as liberal and progressive, who represented the government introducing the legislation that enfranchised women, privately expressed concerns about women’s abilities to resist the nationalist propaganda and not wasting their votes (Piłsudska Reference Piłsudska1989, 87).

The anti-suffrage attitudes were displayed at the start of 1917, when the idea of the independent Poland became realistic, yet, neither of the political parties had women’s enfranchisement as a part of their agenda, despite the loyalty and support given by women’s groups to the national struggle for independence (Dufrat Reference Dufrat, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2008). Responding to this, in September 1917, over one thousand female activists from all three partitions, representing women’s organizations of diverse profiles, gathered at a Women’s Congress in Warsaw to negotiate with the then-emerging Polish government to legitimize women’s demands for equal political rights and put the issue back on the political agenda of the parties (Fuszara Reference Fuszara, Pawilka and Zakrzewska-Manterys2008; Dufrat Reference Dufrat, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2008). According to Katarzyna Sierakowska (Reference Sierakowska, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2009), the 1917 Congress was a key development in the history of the Polish women’s movement as it unified its different currents under one umbrella, ensuring women’s political rights as a part of the emerging Polish democracy. Despite the patriarchal, anti-feminist stance, after November 1918, all political parties strove to appeal to women, who constituted half, or sometimes more than half, of voters, and who were considered a serious but “unpredictable” political force (Kałwa Reference Kałwa and Passmore2003, 163).

The creation of NOK was a direct response to the new challenges that came with the creation of the modern Polish state and what the nationalist politicians saw as threatening forces preventing them in realising their vision of Poland. Women’s role was to support the politicians in their efforts. Unlike the female activists discussed above, the majority of NOK’s members were not involved in the struggle for independence or suffrage campaign, and represented the aristocratic, intelligentsia, and landed gentry women with ideological, and often familial, ties to National Democrats. They embodied the patriarchal and nationalist ideals of the party milieu, declaring their rejection of the “revolutionary struggle between sexes,” proclaiming their mission to build a strong community of Poles based on nationalist and Christian principles (Mysiakowska-Muszyńska Reference Mysiakowska-Muszyńska2015, 25). Considering this, it was not surprising that in the January 1919 election campaign, the glorification of women’s role in building the bright future of the nation within the National Democratic campaign occurred on a par with the male hostility towards women’s political rights; all (male-dominated) parties were reluctant to share the power with women. As a result, the female candidates, who could only be proposed indirectly, via political parties, were placed at the bottom of the election lists, in positions “doomed to fail” (see Żarnowska Reference Żarnowska2014, 58) or they were missing from the lists entirely, while the slogans emphasized women’s role in the elections as counterbalancing the Jewish electorate (Ilski Reference Ilski2018).

Ethnic Nationalism in the National Democratic Party and the Role of the Press

Dmowski created the National Democratic Party in 1897, around the time when he began introducing his radical nationalistic views based on European ideas of Social Darwinism and racial discourse. In 1902, Dmowski published Thoughts of a Modern Pole (Myśli nowoczesnego Polaka), which began a new phase of Polish nationalism (Górny Reference Górny, Mishkova, Turda and Trencsenyi2014; Dawidowicz Reference Dawidowicz2017; Walicki Reference Walicki2000).Footnote 7 Until 1912, the founding men of ND, Roman Dmowski, Zygmunt Balicki, and Jan Popławski, paid little attention to the issue of the Jewish minority in Poland, with Dmowski being a proponent of a Polish union with Russia, where Poland would gradually become an autonomous state and where Jews would be loyal to the Polish national interest (Dawidowicz Reference Dawidowicz2017; Michnik and Marczyk, “Introduction” Reference Michnik, Marczyk, Michnik and Marczyk2018). He drastically changed this stance becoming xenophobic and hostile towards Jews, particularly after losing a seat in the Russian Duma in 1912 to a socialist candidate, who received great support from the Jewish electorate in Warsaw (Walicki Reference Walicki2000). It was this context that set the tone for Dmowski’s publication of “The Jewish Question” (1912), where he rejected the idea of assimilation of Jews into Polish society (Górny Reference Górny, Mishkova, Turda and Trencsenyi2014; Dawidowicz Reference Dawidowicz2017, Michnik and Marczyk, Reference Michnik, Marczyk, Michnik and Marczyk2018). The publication, widely read in Poland and abroad, contributed to the heightened ethnic nationalism, which, in the same year, provoked an antisemitic boycott, largely centred in Warsaw, uniting “Polish liberals and nationalists” (Blobaum Reference Blobaum2002, 813). According to Theodore Weeks other factors contributing to the intensified antagonism between Poles and Jews included the strengthening of Jewish national self-consciousness, reflected in the emergence of national organizations and parties, which collided with heightened Polish nationalism, but also relaxation of censorship, which allowed for a greater cultural development and revival of Jewish intellectual life, such as sprouting of newspapers in Yiddish (Weeks Reference Weeks1995).

Gradually, political antisemitism became an immanent part of Dmowski’s version of nationalism, which fed on “ethnic rivalry,” and which constituted an integral element of his party’s programme aimed at attracting the support of various social classes (Walicki Reference Walicki2000, 14; Bełcikowska Reference Bełcikowska1925).Footnote 8 The concept of Jew as a threatening other became a key component of the “exclusivists ethnic nationalism” espoused by National Democrats. Arguably, this aspect of Dmowski’s ideology was a way of clearly distinguishing himself from his greatest political rival, Józef Piłsudski, whose socialist party embraced the idea of a multi-ethnic state.Footnote 9 Over time, Dmowski’s rhetoric grew radically antisemitic and he advocated for the expulsion of Jews from Poland, a narrative spreading to the party’s major press sources as well as the programmes of organizations supportive of ND’s camp, including the emerging women’s organizations (Dawidowicz Reference Dawidowicz2017). Even though the party generally presented NOK as fully independent,Footnote 10 it is clear that it operated within the ideological framework of the party’s founding fathers. The core female members of NOK were linked to the National Democratic Party through family ties; their husbands, fathers, or brothers were active in the party circles. The most prominent members included Gabriela Balicka (1871–1962), the wife of one of the party’s early leaders, and, next to Dmowski, a chief ideologist of modern Polish nationalism, Zygmunt Balicki; Zofia Kirkor-Kiedroniowa (1872–1952), a sister of prominent MPs, Stanisław and Władysław Grabski, whose husband, Józef Kiedroń, was an active pro-Polish activist in Silesia; and Józefa Szebeko, the leader of NOK at its creation, whose brother was a first chargé d’affaires of the Second Polish Republic in Berlin (Kotowski Reference Kotowski, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2009, 283–284). These were an elite group of women close to the political life well before all women in Poland could vote. The same family links, however, determined the scope of activism and duties performed by women in NOK.

The key platforms through which ND shared their vision of the ethno-nationalist Poland during the election campaign were rallies and the press (Ilski Reference Ilski2018, 37). The National Democratic Party had a great financial means, strong press and employed “radical and ruthless” tactics to achieve their agenda, observed Alicja Bełcikowska in her Reference Bełcikowska1925 book, a first study of political parties and associations in Poland (Bełcikowska Reference Bełcikowska1925, 66). The party created the “most opinion-forming press systems” of the interwar period: it was a widely accessible source of information about the rapidly changing political situation, mainly in the Kingdom of Poland and Galicia, a former Habsburg partition (Dawidowicz Reference Dawidowicz, Dajnowicz and Miodowski2016, 229). The most efficient political propaganda outlets were the party’s two major papers, Gazeta Warszawska, the oldest public press title in the capital, purchased by the party in 1909, and its sister paper, Gazeta Poranna (1912–1929).Footnote 11 The content of Gazeta Warszawska was highly politicized, with all editors being Endecja-sympatizers, and the newspaper gaining a serious, somewhat elitist character. Gazeta Poranna, on the other hand, was aimed at a wider public and had a more populist profile. After the suspension of Gazeta Warszawska between 1915 and 1918, Gazeta Poranna became the major conveyor of the ND’s political ideology; incidentally, the first election campaign coincided with the newspaper’s peak of popularity (Paczkowski Reference Paczkowski1983). Most importantly, Dmowski himself ordained the creation of Gazeta Poranna, which was to become a major “platform of the economic boycott of Jews,” mainly in the Kingdom of Poland (Walicki Reference Walicki2000, 28–29). The newspaper promoted swój do swego (“each to their own”), an idea underlying the boycott. The slogan “Swój do swego” has its roots in the economic boycott of the German trade by the Poles, in the heavily Germanized Prussian partition. However, in the interwar period, it was used by the nationalists to discredit Jewish businesses urging the public to buy in stores run by ethnic Poles instead (Zieliński Reference Zieliński2004; Halczak Reference Halczak2000; Wilczkowski Reference Wilczkowski1937): “The National Democratic propaganda targeted Poles engaged in petty trade, who viewed every Jew as a competitor,” summed up the situation Czesław Miłosz (Reference Miłosz, Michnik and Marczyk2018, 11). At the end of 1918 and beginning of 1919, both newspapers were oriented towards the election results and had a wide outreach, especially in the parts of Poland previously under the Russian rule, that is, where the majority of constituencies for the January 1919 elections were located.Footnote 12

It was symptomatic that individuals and groups linked to Endecja repeatedly rejected accusations of antisemitism, including the members of NOK. Dmowski, for instance, claimed the boycott was a “non-violent, civilised means of inter-ethnic struggle” for influence, even though it was the antisemitic, inflammatory language of ND that has been considered the major catalyst for the assassination of the first Polish president, Gabriel Narutowicz (Walicki Reference Walicki2000, 28–29).Footnote 13 In a similar vein, Zofia Kirkor-Kiedroniowa, NOK’s members and a regular contributor to ND’s newspapers, whose articles espoused the conspiratory, antisemitic rhetoric, insisted she was not an antisemite, reasoning that the Jewish control of the trade and industries in Poland debilitated the nation.Footnote 14 In her memoir (Kirkor-Kiedroniowa Reference Kirkor-Kiedroniowa1986), she reminisced with a sense of pride about her efforts to revive Swój do swego, the initiative blocked by another member of NOK, Aniela Zdanowska (Dawidowicz Reference Dawidowicz2017). Notably, during the January elections, appeals to Polish women signed by NOK were published in the populist Gazeta Poranna, in order to “mould public opinion,” as NOK’s statute described its goal (Kobieta w Sejmie, 6). From its inception in 1912, the year when Dmowski announced a more aggressive policy towards Jews in Poland by publishing “The Jewish Question,” Gazeta Poranna targeted Jewish businesses allegedly sabotaging Polish trade. NOK played a large role in spreading the anti-Jewish propaganda, which soon translated into exclusionist policies. Antisemitism continued in various forms throughout the interwar period through the organization’s readiness to manage various types of social and economic initiatives, often “aimed at Jewish interests” (Maj Reference Maj, Kulak and Dajnowicz2016, 167). Furthermore, NOK issued numerous anti-Jewish decrees and resolutions, demanding the removal of Jews from trade, education, and schools.Footnote 15

In the Name of God and Fatherland: Antisemitism in the National Women’s Organization

Within the structures of NOK there were teachers, postal and telephones workers, and domestic servants, as well as clerks and office workers employed in the state and local government offices located in cities and in the villages; without a doubt, NOK had the character of a mass organization with a wide outreach. During the January election campaign, NOK’s members travelled across the country to pre-election rallies where they met with voters, appealing particularly to women in provincial towns sceptical towards their new won right (Maj Reference Maj, Kulak and Dajnowicz2016; Mysiakowska-Muszyńska Reference Mysiakowska-Muszyńska2015). Next to press, rallies were the second most efficient platform of attracting voters, particularly those from the poorer parts of society, who were often illiterate and responded to more direct means. In the background of those first elections were the internal and external crises, such as revolutionary tendencies, difficulty of integrating lands previously under the rule of different empires, and unemployment, which the new government had to face and which, to a large degree, shaped the campaign characterized by tensions and fierce rivalry (Ilski Reference Ilski2018, 29–33; Żarnowska Reference Żarnowska2014). Thus, accompanying NOK’s campaign were initiatives aimed at building “national solidarity” in a post-partitioned, highly fragmented society. The activities, through which NOK could promote the party’s values while performing traditional femininity based on the maternal role, included educational events, summer camps for peasant children, or collecting means from charity work to help the poorest (Maj Reference Maj, Kulak and Dajnowicz2016, 167). Most importantly, women who joined the Catholic-nationalist camp through NOK emulated the antisemitic language of the party in the election leaflets and in press appeals (Kałwa Reference Kałwa and Passmore2003). Their content was used to shift public opinion in favour of the “National List,” effectively the members of the National Democratic Party.

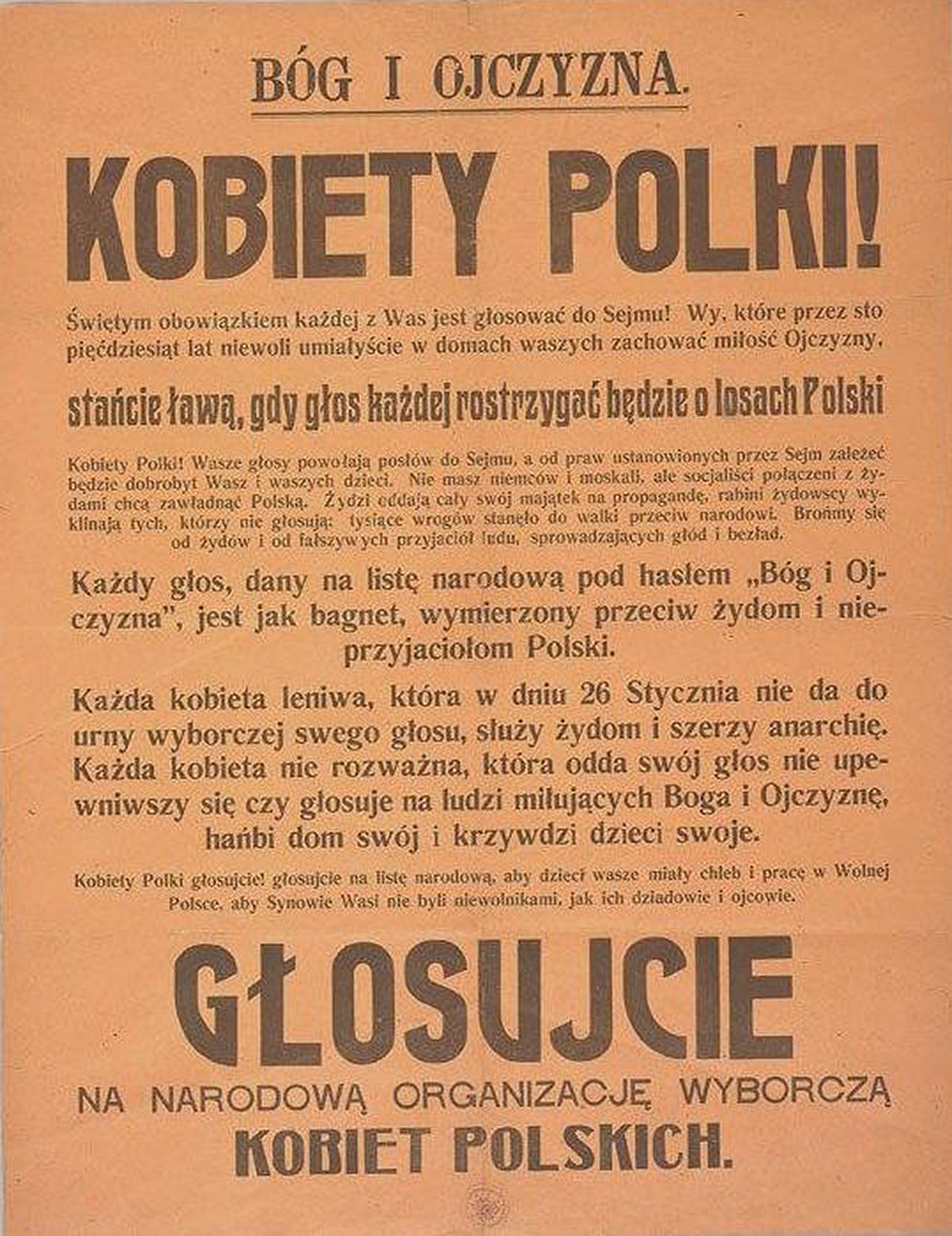

Two weeks before the elections, the entire front page of Gazeta Poranna featured NOK’s leaflet with an enlarged, dramatic-looking heading “Kobiety Polki!” (“Polish women”) and a slogan “Bóg i ojczyzna” (“god and fatherland”) (see Figure 1).Footnote 16 It urged women to fulfil their “sacred duty” and register to vote, stating the vote will impact on “your wellbeing and that of your children.” In a smaller font, the leaflet insinuated that Jews had been spending large sums on propaganda and that, together with socialists, they wanted to take over Poland. The leaflet concluded with a kind of warning, that non-voting women would be found to be traitors at service to Jews. The call concluded with a blunt statement: “Every vote cast for the National List under the slogan ‘God and Fatherland’ is like a bayonet aimed against Jews and enemies of Poland” (Figure 1).Footnote 17 Aside from the antisemitic propaganda, the leaflet failed to address issues relevant to the experiences of the female voters, for example, explaining how exactly women’s lives will improve through casting the vote.

Figure 1. “Kobiety Polki.” 1919 election leaflet of National Organization of Women described Jews as a threat to Poland’s sovereignty. Source: NAC (Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe), public domain.

The leaflet echoes the ideologically charged content found across the Catholic nationalist newspapers leading up to the elections, such as Gazeta Poranna’s short text “Polki a Sejm” (“Polish women and the Parliament”), also an example of ND’s instrumental treatment of women’s role in the elections.Footnote 18 The article opens with the statistics about the disproportionate number of male and female voters in large Polish cities but the narrative soon shifts from discussing the divisions alongside gender to the language of religious denomination; namely, contrasting Polish Catholic voters with Jewish voters. It stresses the bravery and sacrifices made by the Catholic men, and suggests that the significantly larger proportion of the Jewish male voters in relation to the Jewish female voters was due to Jewish men avoiding military service.Footnote 19 It implied that Jews did not sufficiently support Poland’s struggle for independence, a continuation of the discrediting political discourse that emerged during the war. Drawing from the motifs of Polish martyrology and Jewish conspiracy, the text presents a typically divisive discourse of “us” and “them” used by the Catholic nationalists to demonise their political opponents. To mobilise the female voters, the articles and election materials included lines about Jews as a kind of threat to the budding Polish democracy, stressing women’s role in defending the country against this threatening other. As Dobrochna Kałwa aptly noted, the editors of nationalist newspapers perceived women’s role primarily as “counterbalancing the Jewish influences” (Kałwa Reference Kałwa and Passmore2003, 162).

Even though, in theory, NOK was to focus primarily on social work without too much involvement in politics (on this, see Kobieta w Sejmie, 6), unsurprisingly, two of its programme’s main objectives were strictly political. One was to help building national and political awareness within the society, and the other, to develop the internal and external politics based on the principles of Christian ethics (Statut, 1–2). Catholicism played a unique role within NOK. The Catholic Church was a fully-fledged part of the ND camp, with priests organizing election rallies and openly influencing voters during masses (Ilski Reference Ilski2018). ND’s treatment of the Church was purely strategic as, by embracing it, the Democrats hoped to use its influence to increase theirs (Wapiński Reference Wapiński1980, 128). Aside from aligning with the Catholic Church, the rhetoric of religious denomination across the press and campaign leaflets was a way of exercising the policy of exclusion. In many cases, the word “Christian,” used interchangeably with “Catholic,” euphemistically stands for “ethnic Polish” or “non-Jewish,” often additionally stressed by the pronoun “our:” our (Polish) shops, our (Polish) produce, a clear pronouncement of the Swój do swego ideology. It was in this vein that the Catholic-nationalist newspapers, including Gazeta Poranna, promoted turning to “Christian” shops and products as a manifestation of Polish patriotism; examples include semantically ridiculous phrases such as an advertisement of “Christian dairy” or “Christian hardware.”Footnote 20 From these examples, it is apparent that the religious rhetoric was exploited in order to strengthen the exclusionist policies towards Jewish citizens, in line with Dmowski’s idea of “healthy national egoism” (Zamoyski Reference Zamoyski2015, 286).

This exclusionist rhetoric is apparent in the statute of NOK, issued in May 1919 at the organization’s approval by the Minister of Internal Affairs, when it became the first officially recognized women’s organization in the Second Polish Republic. The statute explained that the membership of NOK was open to any Polish woman of the Christian faith, “loyal to the order God and Fatherland” (Statut, 3; Kotowski Reference Kotowski, Janiak-Jasińska, Sierakowska and Szwarc2009, 285). Without specifically mentioning Jewish women, it clearly limited the possibility of their participation in the organization on the basis of religion. As much as Catholicism shaped women’s activities in the public sphere—during the partitions it was an added value in efforts to preserve national identity and resist cultural colonization—it also was a conservative force that helped to maintain the patriarchal order, in other words the “traditionally subjugated position of women,” in both private and public spheres (Żarnowska Reference Żarnowska2014, 61). Reading the report of NOK’s activity for the years 1919–1927, Catholicism appears discussed precisely in these two contexts: as a set of morals that dictate women’s destiny, and as a part of national heritage that needs protecting from “alien” influences (Kobieta w Sejmie, 6).

The contribution of Catholic-nationalist women’s groups to increased antagonism between Poles and Jews, which continued through the 1920s and escalated in the 1930s (see Michlic Reference Michlic2006; Michnik and Marczyk Reference Michnik, Marczyk, Michnik and Marczyk2018), was touched upon by female activists in the rapidly developing Jewish press, in the aftermath of the war. The editors of Ewa: Tygodnik (Eva: a Weekly), the only Polish-language Jewish feminist newspaper, published in the years 1928–1933,Footnote 21 commented how the project of building all-women’s solidarity in Poland failed due to “backward antisemitism” (Antosik-Piela Reference Antosik-Piela2008). The example of Iza Moszczeńska, an influential campaigner for women’s political emancipation in Poland and one of the creators of the Women’s League for War Alert (Gawin Reference Gawin, de Haan, Daskalova and Loutfi2005), is an example of how the intensified debate about Polish Jews undermined women’s collaboration, further straining Polish-Jewish relations. Moszczeńska’s stance on the presence of Jews in Poland became radicalized at the onset of the war when she began engaging with what Theodore Weeks termed the Polish “progressive antisemitism”Footnote 22 even though initially, she objected to the ethno-religious agenda of Polish nationalists (Blobaum Reference Blobaum2002). In the weekly Ewa, Moszczeńska was described as an especially aggressive “Jew-eater” (original Polish word: żydożerczyni), Footnote 23 for her continuous attacks on Jews, among others, in Izraelita (1866–1912), the Polish-language Jewish weekly and her 1911 monograph, Postęp na rozdrożu (“Progress at the Crossroads”) (Weeks Reference Weeks1995).

The subject of “double oppression” of Jewish women became a key theme in Jewish women’s writing after the war, capturing both their emancipatory aspirations as well as the increasingly disadvantageous position of Jews in the independent Poland. Writing about Jewish feminists’ reaction to the country’s independence, Joanna Lisek (Reference Lisek2019) stressed that anti-Jewish incidents occurring after Poland gained independence had a major impact on ideological and life choices of parts of the young generation of Jews. As Lisek’s analysis of the journalistic and poetic texts clearly demonstrates, the optimism resulting from the newly won rights and opportunities for all women in Poland in 1918 were constantly overshadowed by the fear and alienation stemming from the traumatic experiences of the First World War and the wave of anti-Jewish violence that followed in its wake (Lisek Reference Lisek2019).Footnote 24 Jewish women suffered doubly: as women within the traditional Jewish society and as Jews discriminated against. Ewa’s contributors, however, labeled women’s hostile attitudes towards Jews “chauvinist” and “reactionary,” hinting that many female activists had no agency and, hence, operated within the framework imposed by the male-dominated political apparatus (Antosik-Piela Reference Antosik-Piela2008).

Indeed, one may ask to what extent the content of NOK’s statute, election leaflets, and appeals signed by NOK and published by Gazeta Poranna in 1919 truly reflected the views of its members, and to what extent it was merely “dictated?” The enfranchising law introduced in November 1918 sparked a lot of enthusiasm among the female representatives of varied political orientations, who launched a lively discussion in the press about women’s role in politics. Footnote 25 A survey of some of the key texts published within the month following the introduction of suffrage rights demonstrates a firm belief among the contributors that women, due to their high ethical values and morality, can be an asset in politics and steer it away from corruption. Notably, women organized around National Democracy and other Catholic organizations shared in these views (Górnicka-Boratyńska Reference Górnicka-Boratyńska2018). The focal point of the discussion were issues relevant to women’s experiences, such as securing the interests of mothers and children (e.g. enabling women’s work by building crèches) and introducing vocational training and equal pay (Kałwa Reference Kałwa, Haan, Daskalova and Loutfi2005). These early texts present a very different narrative to the language of NOK’s election materials, which referred to women as lazy, a traitor or the “enemy of the country” in case they voted for the socialist party. NOK’s leaflets, unlike, for example, the leaflets for the PPS party,Footnote 26 rarely used incentives that could advance women politically, such as inviting them to vote on the few female candidates that did appear on the ND’s election lists (Kaniewska Reference Kaniewska2019). Contrary to that, the debate, which sprang as a reaction to the introduction of voting rights, focused on women’s common needs and goals and the importance of a female representation in the parliament: only women could best look after women’s issues, argued the authors (Górnicka-Boratyńska Reference Górnicka-Boratyńska2018). Unsurprisingly, any form of targeting ethnic or religious groups was not part of the issues put forward by these activists in the autumn of 1918.

What explains the shifting mood and abandoning these postulates within the month leading to the January 1919 election? We should view women’s activism during those first elections in the independent Poland as a continuation of efforts to maintain their activism in the public sphere, as was the case during the partitions, and as a way of gaining political visibility by the means available to them, including a hostile attitude towards ethnic minorities. Increasingly, as women’s groups began aligning themselves with the political parties, the parties’ ideological aspirations compromised women’s demands. Kuźma-Markowska sees it as an expression of backlash, an attempt to diminish women’s public roles by the dominant political groups: “As early as the beginning of 1919, the previous emphasis on the commonality of women’s needs and ideals was replaced with statements about the irreconcilable social and political differences between men and women” (Reference Kuźma-Markowska, Sharp and Stibbe2011, 279). It is clear that National Democracy mobilized women for its own gains. Gradually, within the rhetoric used by ND’s politicians and journalists, women became replaced by a symbolic “Polish woman,” a construct or ideal, which conveniently de-personalized women and marginalized them politically. Commending the National Democratic Party for including Gabriela Balicka, the wife of the co-founder of the party, on its election list, Gazeta Warszawska pointed out that by doing it, the party paid an overdue tribute to a “Polish woman,” who fought for the freedom of “our country” and who always represented its strength (Ilski Reference Ilski2018, 48–49). This strategy enabled the party to project themselves as keen in sharing political power with women, when in reality only one woman represented their party as an MP.

Women against “Egoistic Nationalism” and Antisemitism

It would not be justified to exonerate the members of NOK, who, by their affiliation and support for ND’s ideology and practices, contributed to spreading the collective fear and hatred of Jews. The situation of Jews in Poland was a popular subject and a heavily exploited political argument, before and immediately after the First World War, to which women, also outside NOK, did not stay indifferent. Unfortunately, the spread of aggressive nationalism and ensuing antisemitism proved an extremely divisive force, undermining women’s principles and distracting them from pursuing equal rights in the public and private spheres. Established in 1928 by Józef Piłsudski, The Union of Civic Work of Women, a second largest women’s organization in interwar Poland, often clashed with NOK, whom they accused of inciting antisemitism (Jóźwik, Reference Jóźwik2015).Footnote 27 A remarkable feminist activist and a member of the female unit of the Riflemen Association, Aleksandra Piłsudska spoke with disgust about Jewish-conspiracy gossip and slander thrown at her husband, Józef Piłsudski, by the ND’s media and politicians in their attempt to discredit him. She observed how National Democracy capitalized on anti-Jewish sentiment, although she found it ridiculous to put it as a charge or a form of reproach to someone that they were Jewish (Piłsudska Reference Piłsudska1989, 179). Commenting on the intensifying atmosphere of hatred surrounding the assassination of the president Gabriel Narutowicz in 1922, Piłsudska remarked that antisemitism had been actively “planted in the society for a while” (Piłsudska Reference Piłsudska1989, 202), only for the seeds of hatred to culminate in this tragedy.Footnote 28 In 1929, one of NOK’s key members, Irena Puzynianka, left the organization to protest the fact that the group became “too involved” in National Democrats’ political ideology, loosing women’s interest from sight (Jóźwik Reference Jóźwik2015). In the following decade, Maria Dąbrowska, an activist who worked closely with Iza Moszczeńska as together they founded and run the Polish Women’s League for War Alert (LKPW, Liga Kobiet Polskich Pogotowia Wojennego, est. 1913) supporting Piłsudski’s Legions, published an essay “Annual Shame” (1936). In it, she condemned the anti-Jewish violence at the universities that ensued after the ND’s government introduction of “ghetto benches,” the quotas on the number of Jewish students admitted to universities (Dąbrowska Reference Dąbrowska, Michnik and Marczyk2018, 50–52). It is hard not to view such aggressive nationalism, characterized by the hostility to ethnic and national minorities as its main feature, as a “manly” response to the “woman question,” an attempt to efface women’s emancipatory progress and replace it with an issue where power and strength—over weaker groups or those marginalized—associated with traditional masculinity, could be demonstrated.

But as nationalism grew more extreme in the first decades of the twentieth century, together with the strengthened support for the idea of an ethnic Polish state, many women from the feminist circles addressed its damaging effects, in some cases, directly critiquing the spread of antisemitism. Marya Turzyma a member of the Union of Equal Rights for Polish Women and the editor of its magazine, Nowe Słowo (New word, a biweekly social-literary magazine devoted to women’s matters, 1902–1907), criticized “national egoism” practiced by National Democracy, which she saw as a form of patriotism based on the oppression of the weaker. In her lengthy book about the goals and challenges of women’s emancipation, Wyzwalająca się kobieta (“emancipating women,” Reference Turzyma1906), Turzyma pointed out that it should be in Poland’s national interest to respect all national groups and grant them equal rights: “today, the national question exists only in places, where the national minorities are oppressed. That’s why we are still dealing with it here [in Polish territories],” concluded the writer (Turzyma Reference Turzyma1906, 113). Quite poignantly, Turzyma compared the purposeful strategy of fueling distrust and resentment between different national minorities used by nationalists to the practices of “those who colonized Poland,” a clear reference to Poland’s partitions, as they would frequently set different social groups against each other for their own cynical gains (Turzyma Reference Turzyma1906, 111). Another feminist activist and educator, Teodora Męczkowska,Footnote 29 insisted that women’s movements could provide an antidote to antisemitism and a “strong moral brake” for all forms of nationalism (Męczkowska Reference Męczkowska1907, 34). Indeed, the Union of Equal Rights for Polish Women as well as the feminists from the PPS circles provided a powerful counterweight to the sympathizers of the right-wing nationalists and their racist rhetoric even though their voices became increasingly muted through the 1930s as feminism grew unpopular while the feminist activists were ostracized (Blobaum Reference Blobaum2002). In their introduction to Against Anti-Semitism, an anthology of the twentieth-century texts addressing antisemitism, Adam Michnik and Agnieszka Marczyk argued that antisemitism has never been something organic to the Polish culture, as shown by the continuing attempts to counter it (Reference Michnik, Marczyk, Michnik and Marczyk2018, xii). That was also shown to be the case with feminist activists, who made repeated attempts at countering antisemitism despite having to face the chauvinist, anti-feminist environment themselves.

Conclusion

The introduction of women’s enfranchisement in 1918, together with the emerging independent Polish state, brought new hopes and ideas for the future. Even though women, similarly to the majority of the population, had had no experience of the democratic process and political organizations, they responded keenly to the new task of electing their representatives in parliament. Male-dominated parties quickly realized the importance of women in the process of government creation, even though the majority had reservations about the presence of women in the public sphere. The right-wing conservative National Democratic camp acted strategically by creating the Women’s Organization for National Elections, entrusting them with attracting the female electorate through patriotic slogans that stressed women’s mission to protect the national interest, traditional family values, and the Catholic faith from the enemies of the country. ND politicized roles traditionally ascribed to women in their pursuit of gaining political advantage and instrumentalized women’s newly gained right to campaign to attract more voters. Even though NOK’s 1928 report stated that women entered the parliament as equal employees of the state, at the inception of the modern Polish state, women had little agency in the decision-making process in the country. The female turnout in the January 1919 elections reached record numbers, but with each subsequent election, women’s participation shrunk.

The NOK did, however, play a major role in popularizing the party’s divisive ethnic ideology, and became one of the channels of spreading antisemitic propaganda within society. The joint front of extreme nationalism (and antisemitism) and anti-feminism that characterized the Catholic nationalist groups at the time still haunts Poland today.Footnote 30 Although many women joined in with the parties in their use of the racist rhetoric against political opponents as a way of empowering themselves politically, ultimately women who supported extreme nationalism and antisemitism denigrated their own rights. The more the Polish women’s movement became divided, the more women’s solidarity—a powerful resource that enabled women to unite and put pressure on politicians to introduce suffrage during and after the Women’s Congress in 1917—was severely undermined. While women became more and more invested in the parties’ ideological conflicts, they moved away from the issues of equality, abandoning the pursuit of women’s equal rights, which could have advanced women politically. As antisemitic attacks intensified through the 1930s, anti-feminist attitudes also became more prevalent, apparent in laws curbing women’s rights (e.g marriage and abortion laws) introduced in tandem with increasingly restrictive policies towards Jews (e.g. university quotas). Maria Turzyma hinted at this, when she remarked that the opposition of women’s emancipationist efforts united “the reactionary and the social democrat, the antisemite with the kabalist, the capitalist and the worker.”Footnote 31

Disclosure

Author has nothing to disclose.