Introduction

Parent-child interactions during the early years, particularly joint book sharing, are crucial in promoting language development, especially children's conversational and narrative skills (Fletcher & Reese, Reference Fletcher and Reese2005; Schick & Melzi, Reference Schick and Melzi2010). Just as autobiographical reminiscing (e.g., Fivush & Fromhoff, Reference Fivush and Fromhoff1988) and play (e.g., Tamis-LeMonda, Baumwell & Cristofaro, Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Baumwell and Cristofaro2012), book sharing presents an opportunity for more competent social partners such as parents to scaffold their children's language by engaging children in the co-construction of the narrative (e.g., Haden, Reese & Fivush, Reference Haden, Reese and Fivush1996; Hoff-Ginsberg, Reference Hoff-Ginsberg1991; Melzi, Schick & Kennedy, Reference Melzi, Schick and Kennedy2011). In addition to providing support for children's acquisition of language and literacy skills, book sharing prepares children for social interactions, as parents transfer knowledge of culture-specific communicative norms to their children during this joint activity (Heath, Reference Heath1983; Pellegrini & Galda, Reference Pellegrini, Galda, van Kleeck, Stahl and Bauer2003; Rogoff, Reference Rogoff1990). Although previous research has shown variability in parent-child book sharing conversations, less is known about cultural differences in gender-specific socialization goals and about cultural differences in the relationship between maternal and child narrative patterns. The present study aimed to compare book sharing practices in the United States and Thailand, specifically examining how narrative styles may differ as a function of culture and child gender, as well as how maternal and child communicative patterns may be associated.

Variability in narrative styles across cultures

Children develop within their larger cultural context and therefore are socialized according to culture-specific norms (Rogoff, Reference Rogoff2003). Socialization goals have been shown to differ between individualistic and collectivist cultures (Markus & Kitayama, Reference Markus and Kitayama1991). Collectivist cultures, including Asian, African, and Latino communities, value interdependence, group harmony, and filial piety (Triandis, Reference Triandis1995). Individuals are often in group settings, which leads to shared knowledge among group members and less reliance on explicit contextual verbal cues during communication (Ng, Loong, He, Liu & Weatherall, Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000). On the other hand, individualistic cultures, including the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom, place importance on independence. Due to the emphasis on the individual, there is less shared knowledge among group members and increased need for more direct and explicit information during communication (Gudykunst & Kim, Reference Gudykunst and Kim1984).

Due to the differences in values of individualistic and collectivist societies, mothers from the two types of culture have different ways of supporting their children's language development. Cross-cultural comparisons of mother-child interactions, specifically communicative patterns of Western and Eastern mother-child dyads during discussions of personal narratives, have revealed distinct conversation styles that correspond to values held by each respective culture (e.g., Minami & McCabe, Reference Minami and McCabe1995; Mullen & Yi, Reference Mullen and Yi1995; Wang, Reference Wang2001; Winskel, Reference Winskel2010). Individualistic North American and Anglo-Australian mothers tend to be elaborative, while collectivist Japanese, Korean, Chinese, and Thai mothers tend to be less elaborative. For instance, Anglo-Australian caregivers generally talk more and provide more evaluative statements when engaging in autobiographical conversations with children, whereas Thai caregivers tend to have more concise conversations with children (Winskel, Reference Winskel2010). Importantly, such differences in maternal conversation styles have implications for children's language development. Specifically, the way mothers talk to their children during dyadic reminiscing conversations has been shown to influence children's narrative skills (Fivush, Haden & Reese, Reference Fivush, Haden and Reese2006). Children of elaborative mothers share longer and more descriptive stories (Reese, Haden & Fivush, Reference Reese, Haden and Fivush1993; Reese & Newcombe, Reference Reese and Newcombe2007), and also have better developed vocabulary and story comprehension skills (Reese, Reference Reese1995).

As previously mentioned, parent-child interactions during book sharing also provide opportunities for teaching children rules of social interaction (Rogoff, Reference Rogoff2003), as well as culture-specific literacy norms (Heath, Reference Heath1982; Melzi & Caspe, Reference Melzi and Caspe2005). As such, there is variability across cultures in the ways that books are shared between parents and their children (e.g., Luo, Snow & Chang, Reference Luo, Snow and Chang2012; Luo, Tamis-LeMonda, Kuchirko, Ng & Liang, Reference Luo, Tamis-LeMonda, Kuchirko, Ng and Liang2014; Murase, Dale, Ogura, Yamashita & Mahieu, Reference Murase, Dale, Ogura, Yamashita and Mahieu2005). One dimension in which cross-cultural differences have been observed between individualistic and collectivist cultures is the expected roles of mothers and children during book sharing. Evidence from previous studies suggests that American mothers adopt a story-builder style where they invite their child to co-construct the narrative through the use of questions. Conversely, Latino, Chinese, and East Indian mothers adopt a story-teller style where they take the lead in narrating the story by asking the child fewer questions and using more directives, as children are expected to be an attentive audience (Caspe, Reference Caspe2009; Harkins & Ray, Reference Harkins and Ray2004; Melzi & Caspe, Reference Melzi and Caspe2005; Melzi et al., Reference Melzi, Schick and Kennedy2011; Wang, Leichtman & Davies, Reference Wang, Leichtman and Davies2000). These two distinctive narrative styles are in line with the socialization goals of each respective culture: the story-builder style aims to promote children's autonomy and self-expression via active participation, whereas the story-teller style teaches children to show respect to adults by listening attentively. As with the autobiographical reminiscing interactions, a story-builder style that involves co-construction through use of open-ended questions has been shown to be important for children's early literacy development (Haden et al., Reference Haden, Reese and Fivush1996).

As a result of differing expectations regarding their roles (co-constructor versus audience), children from different cultural backgrounds also exhibit distinct narrative styles. For instance, compared to American children, Latino children contribute less to the construction of the story (Caspe, Reference Caspe2009; Melzi & Caspe, Reference Melzi and Caspe2005; Melzi et al., Reference Melzi, Schick and Kennedy2011). There are also differences in the use of specific linguistic strategies such as labeling. Japanese children tend to produce labels in response to their mothers’ labeling, whereas American children tend to produce labels as a result of mothers’ questions, suggesting that Japanese children are expected to follow their mothers’ lead via imitation, whereas American children are not (Murase et al., Reference Murase, Dale, Ogura, Yamashita and Mahieu2005). These results provide further evidence for the emphasis on filial piety in the collectivist Japanese culture and independence in the individualistic American culture respectively. However, the binary distinction between individualistic versus collectivist culture is overly simplistic (Tamis-LeMonda et al., Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Way, Hughes, Yoshikawa, Kalman and Niwa2008). Although cultures that fall under the same umbrella category (e.g., collectivist Asian cultures) share numerous similarities, there are also nuanced differences in language and literacy socialization goals. Thus, instead of generalizing communicative patterns from one culture to another, it is important to examine the potential variability across cultures to examine how unique socialization practices may manifest through language use.

Despite cross-cultural differences in maternal and child narrative styles, one commonality across different cultural groups is the fact that maternal scaffolding styles during book sharing are generally related to the children's own narrative contributions (e.g., Kang, Kim & Pan, Reference Kang, Kim and Pan2009; Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000). Wang et al. (Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000) compared narrative styles of American and Chinese mother-child dyads during book sharing interactions and found associations between mothers’ and children's repetitions, evaluations, associative utterances (i.e., statements that are not specific to the story but are related to it), and off-topic utterances (i.e., comments not related to the story book) in both cultural groups. However, for metacognitive utterances (i.e., comments about the task itself and the cognitive processes related to the task), there were associations between the metacognitive talk of Chinese mothers and children but not between American mothers and children. These findings suggest that although maternal narrative scaffolding and children's own narrative contributions tend to be related, there may be cultural differences in which particular sets of maternal and child conversation styles are associated. However, systematic examinations of culture-specific associations between maternal and child narrative patterns are currently lacking in the literature.

Gender differences in parent-child interactions

Culture is not the only factor that has been shown to influence the nature of parent-child interactions and the ways that children are socialized. Research on mother-child interactions has provided evidence that the way parents talk to their children also differs as a function of child gender. Specifically, during dyadic autobiographical reminiscing, parents have been shown to use a more elaborative style when reminiscing with daughters than with sons (Haden, Haine & Fivush, Reference Haden, Haine and Fivush1997; Reese & Fivush, Reference Reese and Fivush1993; Reese, Haden & Fivush, Reference Reese, Haden and Fivush1996). Mothers are more evaluative (Reese & Fivush, Reference Reese and Fivush1993; Reese et al., Reference Reese, Haden and Fivush1996), use more emotion words (Adams, Kuebli, Boyle & Fivush, Reference Adams, Kuebli, Boyle and Fivush1995), and use more supportive speech with daughters than with sons (Leaper, Anderson & Sanders, Reference Leaper, Anderson and Sanders1998). Children themselves have also shown gender differences in their speech patterns, where girls' narratives tend to be longer and include more evaluations compared to boys (Haden et al., Reference Haden, Haine and Fivush1997).

Similar to the context of dyadic reminiscing, joint book sharing interactions between parents and children may also differ depending on the child's gender (e.g., Anderson, Anderson, Lynch & Shapiro, Reference Anderson, Anderson, Lynch and Shapiro2004; Curenton & Craig, Reference Curenton and Craig2011; Meagher, Arnold, Doctoroff & Baker, Reference Meagher, Arnold, Doctoroff and Baker2008). For example, mothers have been shown to direct more specific questions to girls than boys (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Arnold, Doctoroff and Baker2008). In terms of content, parents have been shown to discuss emotions more when reading with boys than with girls (Curenton & Craig, Reference Curenton and Craig2011), although this is opposite to the trends found during personal narratives (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Kuebli, Boyle and Fivush1995). Despite the mixed evidence across types of interactions, results from previous studies suggest that child gender is an important variable to consider when examining mother-child conversations.

Comparably less is known about how cultures may differ with regard to gender-specific socialization goals and the way those goals are transmitted through literacy tasks. Most of the research showing evidence of gender differences in parent-child interactions has either focused on dyads from the same cultural background (Curenton & Craig, Reference Curenton and Craig2011; Haden et al., Reference Haden, Haine and Fivush1997; Reese & Fivush, Reference Reese and Fivush1993; Reese et al., Reference Reese, Haden and Fivush1996) or on ethnically diverse samples of dyads without systematically comparing across different cultures (Meagher et al., Reference Meagher, Arnold, Doctoroff and Baker2008). In the extant literature, cross-cultural comparisons that considered potential interactions between culture and gender have shown no gender effects (Harkins & Ray, Reference Harkins and Ray2004; Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000). For example, Wang et al. (Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000) compared book sharing and reminiscing interactions in American and Chinese mother-child dyads and found no interactions between culture and gender in maternal and child talk for both tasks. However, very little has been done to examine the intersection between these two factors. Therefore, it is critical to improve our understanding of how gender-specific socialization goals may influence narrative and literacy outcomes for boys and girls, as well as how these outcomes may differ depending on the children's cultural background.

The present study

The present study examined cross-cultural differences in how American and Thai mothers scaffold their children's abilities to produce narratives, as well as how the two groups of children differ in their co-construction of the narrative. Although previous work has compared communicative styles of Thai caregivers and children during conversations about past experiences, there has been no systematic investigation of book sharing practices in Thailand. Particularly, no prior research has examined the scaffolding strategies that Thai caregivers typically use to support children's narrative development or strategies that are emphasized by intervention programs. In comparison, literacy practices and interventions in the United States have been more well-studied. Specifically, research has provided support for the effectiveness of dialogic reading in improving literacy outcomes (Zevenbergen & Whitehurst, Reference Zevenbergen and Whitehurst2003). Dialogic reading involves adults asking open-ended questions, repeating children's contributions, and expanding upon children's incomplete responses. Implementation of these techniques has been shown to improve children's expressive vocabulary (Crain-Thoreson & Dale, Reference Crain-Thoreson and Dale1999; Whitehurst et al., Reference Whitehurst, Arnold, Epstein, Angell, Smith and Fischel1994). Building on the extant research, our work aimed to examine communicative patterns of American and Thai mother-child dyads during book sharing, specifically focusing on linguistic measures that are important for children's language development.

The present study set out to answer three sets of research questions. First, we examined how maternal and child communicative patterns during book sharing differed as a function of culture. In line with evidence from previous studies suggesting that mothers from individualistic and collectivist cultures adopt different narrative styles during book sharing (Melzi et al., Reference Melzi, Schick and Kennedy2011; Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000), American and Thai mothers in this study were expected to adopt a story-builder and story-teller style respectively. Specifically, we predicted that American mothers’ and children's narratives, compared with Thai mothers’ and children's, would be longer (measured by total number of utterances and words), more elaborate (i.e., utilizing more utterances that fall under categories such as labels, descriptions, open-ended questions, closed-ended questions, expansions, extensions etc.), and contain more evaluative responses such as feedback and affirmations.

Second, we examined how maternal and child communicative patterns during book sharing differed as a function of gender, as well as how cultural differences in maternal and child communicative patterns were moderated by child gender. Based on previous findings from the joint reminiscing literature (Haden et al., Reference Haden, Haine and Fivush1997; Reese & Fivush, Reference Reese and Fivush1993; Reese et al., Reference Reese, Haden and Fivush1996), we predicted that mothers of girls would have more elaborated conversations than mothers of boys when sharing a book with their children. Similarly, we expected that girls would adopt a high-elaborative style compared to boys (Haden et al., Reference Haden, Haine and Fivush1997). Additionally, cultural differences were expected to potentially be moderated by child gender. For example, we predicted that, among mothers of girls, American mothers would have more elaborate conversations than Thai mothers, while American and Thai mothers of boys would show no significant difference.

Third, we examined how maternal and child communicative patterns are associated during book sharing. Maternal and child speech patterns during the book sharing interaction were expected to be positively correlated overall (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Kim and Pan2009; Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000). Specifically, we predicted that there would be positive mother-child associations within the same linguistic measures (e.g., maternal and child use of labels). However, cultural differences were also expected in the associations between maternal and child conversation patterns (Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000). Due to the differences in socialization goals and communicative norms, we expected there to be positive correlations between American maternal and child use of language measures such as mothers’ use of descriptions and children's use of recasts and feedback, which would be characteristic of a high-elaborative story-builder style. Conversely, we would expect negative correlations between Thai maternal and child use of language measures such as mothers’ use of directives and children's use of labels and feedback, which would indicate a low-elaborative story-teller style.

By examining cultural and gender differences in book sharing interactions of American and Thai mother-child dyads, we can gain insight into how children are taught to use language in culturally appropriate ways as well as how language interactions can be used as a vehicle for socializing children to fit into their larger cultural context (Schieffelin & Ochs, Reference Schieffelin and Ochs1986). Furthermore, understanding the cross-cultural variation, as well as gender differences, that exist in parent-child joint book reading can improve the current knowledge of the natural variation in narrative development and potentially inform the design of effective intervention strategies to promote literacy and academic success in children from linguistically and culturally diverse backgrounds. Specifically, examining potential cross-cultural differences in scaffolding strategies could reveal techniques that are more well-aligned with culture- and gender-specific socialization goals. Instead of putting effort into training techniques that go against cultural norms, focusing on strategies that caregivers are already inclined to employ could facilitate the training process and improve the efficacy of intervention.

Method

Design

The present study followed a 2 (culture: American, Thai) x 2 (child gender: boy, girl) between-subject design. Two sets of dependent variables focused on 1) maternal language use during the interaction and 2) child language use during the interaction. Measures of maternal and child language use include the number of total utterances, total words, and frequency of each utterance type (e.g., labeling, affirmations, reframing etc.). See the Coding and Data Analysis section and Tables 2a and 2b for the full list of measures.

Participants

Participants were 21 middle-class English monolingual American mother-child dyads (11 boys, 10 girls) living in the United States and 21 middle-class Thai monolingual mother-child dyads (10 boys, 11 girls) living in Thailand. Among the American mother-child dyads, 19 were White and 2 were African American. All Thai mother-child dyads were Asian. Children were four-year-old (range: 3;11 to 5;0 years) preschool children. The rationale for selecting this particular age group was rooted in previous literature examining the development of narrative discourse. Researchers have typically focused on the preschool years because it is a critical period for the ability to co-construct narratives (Nelson & Fivush, Reference Nelson and Fivush2004). Specifically, four-year-olds were selected, as opposed to three-year-olds, because they were old enough to expand upon a topic of conversation (Minami & McCabe, Reference Minami and McCabe1995), which ensured that a substantial amount of child language could be collected for analysis. Four-year-olds were also more likely to have internalized narrative skills scaffolded by their mothers (Chang, Reference Chang2003; Reese et al., Reference Reese, Haden and Fivush1993), allowing for the relation between maternal and child discourse patterns to be examined. Compared with five-year-olds, four-year-olds have yet to make enough gains in conversation skills (Peterson & McCabe, Reference Peterson and McCabe1983), which meant that mothers were still going to provide substantial language scaffolding, allowing for maternal language use to be examined.

Mothers’ and children's background information were obtained using questionnaires. Specifically, mothers were asked to fill out the Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q; Marian, Blumenfeld & Kaushanskaya, Reference Marian, Blumenfeld and Kaushanskaya2007) to assess their own language profiles including their proficiency in speaking, understanding, and reading in their first language, as well as their second language if there was any. Information regarding socioeconomic status, specifically maternal and paternal education, was also obtained from the questionnaire. American and Thai parents did not differ in their years of education. Mothers were also asked to fill out a separate questionnaire that assesses their child's language background and experience. Inclusionary criteria for monolingual dyads included: (a) maternal and child exposure to a second language was less than 20% (if they have a second language or were exposed to one) and (b) maternal and child proficiency in a second language was 5 or lower on the 0-to-10 LEAP-Q scale. Ten Thai and 4 American additional mother-child dyads were tested but were not coded or analyzed for the present study because they did not meet the inclusionary criteria.

In addition to mothers’ self-reported language measures from the LEAP-Q and maternal reports of child language profiles, mother-child dyads were given the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Third Edition (PPVT-III; Dunn & Dunn, Reference Dunn and Dunn1997), a standardized test of English receptive vocabulary and the Expressive Vocabulary Test (EVT; Williams, Reference Williams1997), a standardized test of English expressive vocabulary that is co-normed with the PPVT-III, or the translated Thai versions of the two tests, depending on the dyads’ language background. American and Thai dyads did not differ on their PPVT and EVT scores. See Tables 1a, 1b, and 1c for additional participant information.

Table 1a. Language Background of Thai and American Children

Note. aExposure was reported in terms of percentage per day. bProficiency was averaged across speaking, understanding, and reading domains, measured using the LEAP-Q, on a 0–10 scale.

Table 1b. Language Background of Thai and American Mothers

Note. aExposure was reported in terms of percentage per day. bProficiency was averaged across speaking, understanding, and reading domains, measured using the LEAP-Q, on a 0–10 scale.

Table 1c. Language Background of Thai and American Fathers

Note. aExposure was reported in terms of percentage per day. bProficiency was averaged across speaking, understanding, and reading domains, measured using the LEAP-Q, on a 0–10 scale.

Materials

Two wordless picture books, Frog, where are you? (Mayer, Reference Mayer1969) and Frog goes to dinner (Mayer, Reference Mayer1974), were chosen for this study. We used two separate books to ensure that any differences observed were not stimulus specific. The two books were balanced across cultures and were given to the participants with the titles in English. Based on previous research, the two books do not differ in length or narrative complexity (Gutiérrez-Clellen, Reference Gutiérrez-Clellen2002) and have been used extensively by researchers to elicit narrative samples from children and adults of diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds (e.g., Kuchirko, Tamis-LeMonda, Luo & Liang, Reference Kuchirko, Tamis-LeMonda, Luo and Liang2016; Melzi et al., Reference Melzi, Schick and Kennedy2011). To confirm that there were no differences between the two books, participants’ linguistic measures (mean percentages) were compared across books. Notably, the measures for which there were significant group differences and/or interactions were examined, and no differences across the two books (ps > .05) were observed.

Procedure

During a preliminary visit, the researcher explained to mothers that the study was investigating how children talk with their families. Mothers filled out questionnaires regarding their own background, as well as their child's language experience, to ensure that they meet the criteria for the study. Following the language questionnaires, the researcher also administered the PPVT-III (10–15 minutes) and the EVT (10–20 minutes) to assess mothers’ and children's English or Thai proficiencies.

In a subsequent visit, each mother-child dyad was videotaped interacting at home in the language that they speak. Each dyad completed a book sharing task. Mothers were asked to share with their children wordless picture books, Frog, where are you? (Mayer, Reference Mayer1969) and Frog goes to dinner (Mayer, Reference Mayer1974). Mothers were instructed to share the story as they typically would share picture books and for as long as they would like. The average duration of the book sharing interaction across the two groups was 7.69 minutes (SD = 2.22 minutes). Half of the monolingual mother-child dyads in each group shared Frog, where are you? (Mayer, Reference Mayer1969), while the other half shared Frog goes to dinner (Mayer, Reference Mayer1974), in their respective language. See Appendix A for pictures of the two books and Appendix B for a picture of the set-up of this task.

Coding and data analysis

Video recordings were transcribed at the utterance level using a standardized format, Codes for the Analysis of Human Language (CHAT), available through the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES; MacWhinney, Reference MacWhinney2000). Native speakers of Thai and English transcribed and coded all conversations in their respective languages. Additionally, a Thai–English bilingual speaker who was blind to the hypotheses coded 20% of the transcripts to verify that the coding scheme aligned cross-culturally. Interrater reliability was established between the coders on 20% of the transcripts using Cohen's kappa for all of the measures (Cohen's κ = .88 for Thai coders and κ = .93 for English coders).

Two types of measures were collected: 1) maternal language use and 2) child language use.

Maternal language use

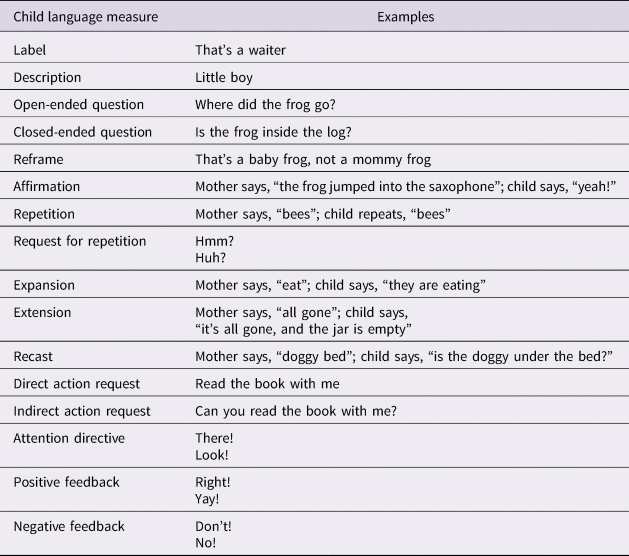

Each maternal utterance was classified into 16 mutually exclusive categories (i.e., affirmation, attention directive, closed-ended question, description, direct action request, expansion, extension, indirect action request, label, negative feedback, open-ended question, positive feedback, recast, reframe, repetition, request for repetition) using a taxonomy adapted from coding systems typically used in the literature (e.g., Tamis-LeMonda et al., Reference Tamis-LeMonda, Baumwell and Cristofaro2012; Tomasello & Farrar, Reference Tomasello and Farrar1986). See Table 2a for more information.

Table 2a. Mothers’ Language Use and Corresponding Examples

Child language use

All intelligible vocalizations were classified into the same 16 mutually exclusive categories as the mothers’, adapted from coding systems of young children's language previously used in the literature (e.g. Bates, Bretherton & Snyder, Reference Bates, Bretherton and Snyder1988; Tamis-LeMonda & Bornstein, Reference Tamis-LeMonda and Bornstein1994). See Table 2b for more information.

Table 2b. Child Language Use and Corresponding Examples

To determine if there was a significant difference in maternal and child language as a function of culture or child gender, the mean percentage of each linguistic measure (calculated by dividing the total count by total number of words) was submitted to a 2 (culture) × 2 (child gender) ANOVA. Post-hoc comparisons, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, were conducted to follow up any significant interaction between culture and child gender. Relations between maternal and child language measures were examined using correlations. Outliers were winsorized, resulting in 74 outliers from the total of 1512 data points being replaced with values 2 standard deviations from the mean.

Results

Results of the maternal and child 2 (culture) × 2 (child gender) ANOVA analyses are presented in Table 3a and 3b respectively. Maternal and child correlations within the same linguistic categories are presented in Table 3c. Full correlation matrices are available in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Materials). Examples of transcript excerpts can be found in Appendix C.

Table 3a. Mean Percentages (Standard Deviations) of Mothers’ Language Use

Note. †p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 3b. Mean Percentages (Standard Deviations) of Child Language Use

Note. †p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 3c. Correlations Between Maternal and Child Language Use

Note. †p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Maternal narrative style

American mothers used more affirmations, descriptions, direct action requests, extensions, negative feedback, and recasting than Thai mothers (ps < .05, partial η2 range: 0.11–0.35), whereas Thai mothers used more attention directives, expansions, and indirect action requests than American mothers (ps < .05, partial η2 range: 0.21–0.37). See Figure 1 for a summary of mean differences between American and Thai maternal communicative patterns. There was a main effect of child gender on maternal use of expansions, where mothers of girls used expansion (M = 0.29, SD = 0.29) more than mothers of boys (M = 0.15, SD = 0.14), F(1,38) = 4.32, p < .05, partial η2 = 0.10. There were no significant interactions between culture and gender for any of the linguistic measures.

Figure 1. Mean differences between American and Thai mothers’ language use during book sharing. Positive mean difference values indicate greater use of the linguistic measure by American mothers compared to Thai mothers. Negative mean difference values indicate greater use of the linguistic measure by Thai mothers compared to American mothers. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Child narrative style

American children produced more words and utterances than Thai children (ps < .05, partial η2 = 0.16 and 0.17 respectively), whereas Thai children repeated their mothers’ utterances more than their American peers (p < .05, partial η2 = 0.12). American children produced more direct action requests than Thai children (p < .001, partial η2 = 0.27), whereas Thai children produced more attention directives and positive feedback than American children (ps < .05, partial η2 = 0.11 and 0.14 respectively). See Figure 2 for a summary of mean differences between American and Thai children's communicative patterns. There was no main effect of child gender on any of the linguistic measures. There was a significant interaction between culture and gender for children's use of attention directives (p < .05, partial η2 = 0.10) and a marginally significant interaction for use of indirect action requests (p = .08, partial η2 = 0.08). However, post-hoc comparisons revealed no significant simple effects (ps > .025) for either use of attention directives (American boys: M = 0.22, SD = 0.39 vs. Thai boys: M = 2.04, SD = 2.79, t(19) = −2.14, p = .05; American girls: M = 0.32, SD = 0.46 vs. Thai girls: M = 0.35, SD = 0.51, t(19) = −0.15, p = .88) or use of indirect action requests (American boys: M = 0, SD = 0 vs. Thai boys: M = 0.80, SD = 1.54, t(19) = −1.73, p = .10; American girls: M = 0.24, SD = 0.27 vs. Thai girls: M = 0.17, SD = 0.44, t(19) = 0.47, p = .64).

Figure 2. Mean differences between American and Thai children's language use during book sharing. Positive mean difference values indicate greater use of the linguistic measure by American children compared to Thai children. Negative mean difference values indicate greater use of the linguistic measure by Thai children compared to American children. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Associations between maternal and child narrative styles

When focusing on associations between maternal and child use of the same linguistic measures, correlation analyses revealed significant positive correlations (ps < .05) between maternal and child number of utterances (American r = 0.59, Thai r = 0.74) and use of labels (American r = 0.76, Thai r = 0.49) for both the American and Thai groups. There were significant positive correlations between maternal and child use of descriptions (r = 0.50) and expansions (r = 0.46) only in the Thai group, and significant positive correlations between maternal and child use of attention directives (r = 0.43) only in the American group.

Additionally, associations between maternal and child language measures were examined for all of the linguistic categories. Correlation analyses revealed that maternal use of descriptions was positively correlated with child use of negative feedback (r = 0.46), positive feedback (r = 0.46), and recasts (r = 0.46) only in the American group, whereas maternal use of direct action requests was negatively correlated with child use of labels (r = −0.55) and maternal use of attention directives was negatively correlated with child use of affirmations (r = −0.49) only in the Thai group.

Discussion

To examine how the narrative styles of mothers and children differ as a function of their cultural background and child gender, as well as how maternal and child speech patterns are related, language samples were collected from American and Thai mother-child dyads as they engaged in a book sharing task. Results provide evidence suggesting that there were cross-cultural differences in book sharing practices of American and Thai mother-child dyads and that specific speech patterns of mothers and children were related when engaging with a book. However, narrative styles did not differ as a function of child gender and there were no significant interactions between culture and gender in terms of mother-child book sharing patterns.

American and Thai mothers exhibited distinct narrative scaffolding styles, which provide evidence for cross-cultural differences in book sharing practices in the United States and Thailand and reflect culture-specific socialization goals. Specifically, American mothers used more affirmations, negative feedback, and recasting compared to Thai mothers, whereas Thai mothers used more attention directives than American mothers. Greater use of affirmations and recasting by American mothers compared to Thai mothers is indicative of the story-builder style, where positive evaluations and questions are used to encourage children to continue narrating (Caspe, Reference Caspe2009; Melzi & Caspe, Reference Melzi and Caspe2005; Melzi et al., Reference Melzi, Schick and Kennedy2011; Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000), while negative feedback may be used to model autonomy and self-expression (Doan & Wang, Reference Doan and Wang2010; Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000; Winskel, Reference Winskel2010). On the other hand, greater use of attention directives by Thai mothers compared to American mothers is characteristic of the story-teller style because commands inherently do not serve the purpose of inviting children to co-construct the narrative (Melzi et al., Reference Melzi, Schick and Kennedy2011; Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000) but instill the values of filial piety in the children (Minami & McCabe, Reference Minami and McCabe1995; Mullen & Yi, Reference Mullen and Yi1995, Winskel, Reference Winskel2010). Another cultural difference between maternal scaffolding styles was found in the use of action requests. American mothers used more direct action requests than Thai mothers, whereas Thai mothers used more indirect action requests than American mothers. Although use of action directives by the American mothers may contradict the story-builder style, the cultural difference between the two groups of mothers here still aligns with individualistic and collectivist values respectively. Since explicit information is valued in individualistic societies (Gudykunst & Kim, Reference Gudykunst and Kim1984), American mothers were more likely to use commands that were direct. Conversely, collectivist cultures place an importance on group harmony (Triandis, Reference Triandis1995), which may explain why Thai mothers were more likely to opt for indirect commands instead.

Differences in maternal narrative styles in the present study are also in line with the mother-child autobiographical reminiscing literature (Minami & McCabe, Reference Minami and McCabe1995; Mullen & Yi, Reference Mullen and Yi1995; Winskel, Reference Winskel2010) and suggest that an elaborative style is favored in the American culture and a repetitive style is favored in the Thai culture. American mothers produced more descriptions, extensions, and recasting than Thai mothers, whereas Thai mothers produced more expansions than American mothers. Compared with Thai mothers, American mothers utilized a larger variety of scaffolding strategies to elaborate upon their child's utterances. The fact that the two groups of mothers showed these distinct scaffolding styles (elaborative versus repetitive) during book sharing interactions suggests that mothers use the same culture-specific strategy to support children's narrative skills across not only autobiographical memories, but also storybooks.

The two groups of children also differed in their narrative patterns, congruent with the individualistic and collectivist values previously found in comparisons of book sharing interactions. American children spoke significantly more than their Thai peers, whereas Thai children repeated their mothers’ utterances more than American children did. Similar to the narrative styles of Latino children, Thai children contributed less to the storytelling compared to their American counterparts (Caspe, Reference Caspe2009; Melzi & Caspe, Reference Melzi and Caspe2005; Melzi et al., Reference Melzi, Schick and Kennedy2011). Thai children repeating their mothers more than American children is reminiscent of Japanese children who produced labels in response to their mothers’ labels more than their American counterparts (Murase et al., Reference Murase, Dale, Ogura, Yamashita and Mahieu2005) and provides evidence that Thai culture may value learning by imitation, in line with the emphasis of filial piety in collectivist cultures. Additionally, the fact that Thai children produced more positive feedback than their American peers could also be indicative of their expected role as an audience (i.e., instead of producing their own unique narrative contributions, Thai children were giving their mothers feedback as a sign of attentiveness).

When examining associations between maternal and child language use during book sharing, results revealed relations between maternal and child narrative length in terms of number of utterances produced, as well as between maternal and child use of attention directives, descriptions, expansions, indirect action requests, and labeling. Although these findings reiterate that there are similarities between mothers’ narrative styles and their children's own narrative skills (Fivush et al., Reference Fivush, Haden and Reese2006; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Kim and Pan2009; Reese et al., Reference Reese, Haden and Fivush1993; Reese & Newcombe, Reference Reese and Newcombe2007; Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000), one limitation to the current study is the fact that these correlation results are unable to capture the temporal contingencies of maternal and child language use during the book sharing activity, as well as the bidirectional nature of the narrative contributions. Further research will be necessary to examine the direction of effects in order to conclude how much of the mothers’ narrative styles were influencing the children's narrative abilities and vice versa. Additionally, it is notable that only a small subset of all the language measures showed associations between mothers and children. This could potentially be attributed to the nature of the task, where, regardless of whether the mothers adopt a story-teller or story-builder style, book reading is a task during which mothers predominantly ask questions to guide and scaffold their children's narrative abilities (Hoff-Ginsberg, Reference Hoff-Ginsberg1991).

With respect to cross-cultural differences in the associations of maternal and child language use, there were specific linguistic measures that were correlated within one group but not the other, as was found in Wang et al. (Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000). Maternal and child use of attention directives were correlated in the American group but not in the Thai group, whereas use of descriptions and expansions were associated in the Thai group, but not in the American group. These cultural differences may be illustrative of what is normative for children to say to their parents. For instance, because American culture values competence and emphasizes children's autonomy (Doan & Wang, Reference Doan and Wang2010; Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000), it may be acceptable for American children to direct their mothers’ attention and instruct adults what to do. On the other hand, Thai children are expected to be obedient and respectful to their elders (Doan & Wang, Reference Doan and Wang2010; Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000) and therefore it may not be appropriate for Thai children to use directives during interactions with their mothers. Additionally, cross-cultural differences in mother-child associations contribute to our understanding of the book sharing practices in the United States and Thailand and further support the dichotomy of story-builder versus story-teller style (Melzi et al., Reference Melzi, Schick and Kennedy2011; Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000). Particularly, American mothers’ elaborative utterances such as descriptions were positively associated with American children's own narrative contributions such as use of feedback and recasts, while Thai mothers’ use of directives were negatively associated with Thai children's contributions such as use of labels and affirmations.

The other goal of the current work was to examine gender differences in maternal and child narrative styles. Maternal speech was shown to differ as a function of gender on one linguistic measure, where mothers of girls used more expansions than mothers of boys. This pattern of maternal scaffolding is in line with previous findings in the reminiscing literature (Haden et al., Reference Haden, Haine and Fivush1997; Reese & Fivush, Reference Reese and Fivush1993; Reese et al., Reference Reese, Haden and Fivush1996) and suggests that mothers may be more elaborative when constructing narratives with daughters than with sons. However, this was the only maternal language measure in which there was a gender difference. With regard to children's own narrative styles, although there were two language measures for which child gender was a moderating factor, follow-up comparisons showed no significant effects. Thus, similar to previous studies, there did not seem to be robust effects of gender on maternal and child narrative styles (e.g., Harkins & Ray, Reference Harkins and Ray2004, Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000) or significant interactions between culture and gender (e.g., Wang et al., Reference Ng, Loong, He, Liu and Weatherall2000) during book sharing of American and Thai mother-child dyads in the present study. These findings suggest that child gender may not be an important moderator for cultural differences observed in the book sharing practices of the two cultures, and that mother-child interactions during book sharing may not be heavily driven by gender-specific socialization goals.

Note that the two cultural groups were similar in many of the linguistic behaviors examined in the study, suggesting that, overall, the two communities overlap in literacy practices. These results highlight the universality of the human experience, revealing that across languages and cultures, there are more similarities than differences in parent-child book sharing practices. Understanding the natural variability that exists across cultures in mothers’ scaffolding strategies and children's narrative styles is necessary in order to accurately distinguish between difference and disorder and to ultimately promote children's successful language outcomes.

Taken together, results from the present work have implications for the language development trajectory of children from diverse cultural backgrounds. Conversations that children engage in with their parents, especially parent-child book sharing interactions during the preschool years, are critical for later literacy development and school readiness. Thus, findings from this study can be particularly helpful to classroom teachers and speech-language service providers, in increasing the sensitivity to and awareness of how particular narrative styles may be appropriate and normative of one culture, but not the other. Additionally, these results may be helpful in informing the development of effective literacy interventions in linguistically and culturally diverse groups. Considering that intervention programs in the United States typically implement dialogic reading, which recommends parents to ask open-ended questions, repeat and expand children's utterances, and overall encourage children's participation (Zevenbergen & Whitehurst, Reference Zevenbergen and Whitehurst2003), the current findings suggest that perhaps some components of dialogic reading may not be appropriate for mothers and children of all cultural backgrounds. For instance, training Asian mothers who typically adopt a story-teller style to encourage participation from the children would be dismissive of their cultural norm and could be less effective than using approaches that are more culturally friendly and appropriate. Instead, practitioners may consider reinforcing and honing in on the sub-components of the intervention technique that are culturally acceptable in order to improve efficacy.

To conclude, parent-child book sharing interactions are influenced in part by culture-specific communicative norms and practices. There are cross-cultural differences in the way that mothers scaffold their children's conversations, as well as differences in children's own narrative skills. American mothers encouraged their children to equally engage in the story-telling process, compared to Thai mothers who took on the role of the story-teller. American mothers also adopted a more elaborative style compared to Thai mothers. In turn, American children contributed more to the narrative than their Thai peers. Overall, the present study demonstrates that there is variability in maternal and child narrative styles across cultures and that children internalize culture-appropriate communicative skills as early as the preschool years.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the mothers and children who participated in this study, as well as the research assistants who have worked on transcribing and coding the video data including Julia Borland, Laura Montenegro, and Grace Pickens. They would also like to thank the members of the Northwestern University Bilingualism and Psycholinguistics Research Group and Drs. Erika Hoff and Steve Zecker for helpful comments and input on this work.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD059858 to Viorica Marian. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000920000562

Appendices

Appendix A Book stimuli: Frog, where are you? and Frog goes to dinner

Appendix B Set-up

Appendix C Sample Transcript Excerpts

Thai mother-child dyads

Example of maternal use of attention directives

Mother: Look! Why is he looking at the frog?

Mother: Oh look! The frog ran away when no one was there right?

Mother: What happened?

Mother: Ah he's asleep, right? The boy is asleep.

Child: How did it disappear?

Child: I don't know where it went. Here! The jar!

Mother: Hmm? Let's see! Where did it go?

Mother: Oh look! Did they find it?

Mother: The dog went to search in here.

Mother: Where did the frog go?

Child: I don't know.

Mother: Look, they're all helping to look for it.

Mother: Look at the dog!

Example of child use of repetition

Mother: They're at the restaurant!

Mother: Who is here?

Child: There is…

Mother: Daddy

Child: Daddy

Mother: Mommy

Child: Mommy

Mother: And here is the sister

Child: Sister

American mother-child dyads

Example of maternal use of affirmations

Mother: Okay what do we have here?

Mother: It looks like we've got…

Child: A doll, a dog, and a kid.

Mother: Yep and a turtle and a frog!

Child: And what's that?

Mother: Um those look like boots to me. What is he…?

Child: Shoes!

Mother: Shoes yeah.

Example of maternal use of extensions

Mother: Why do you think they're mad?

Child: (Be)cause he brought his frog.

Mother: (Be)cause he brought his frog and now they have to leave the restaurant!

Mother: He says go away go away!

Mother: And they are like

Mother: We were hungry!

Mother: We wanted to eat!

Mother: Uh oh now dad's kinda mad.

Mother: What does dad say?

Child: Go in your room.

Mother: Go in your room and put the frog away.