Introduction

A ranula is an extravasation mucocele arising from the sublingual gland or its main duct after trauma or obstruction.Reference Packiri, Gurunathan and Selvarasu1 The word ranula derives from the latin ‘rana’, used to refer to a small frog, as the blue translucent colour of the oral floor resembles a frog's belly. The pathophysiological basis is the extravasation of saliva, the consequent inflammatory reaction and the formation of a pseudocyst where saliva is retained. Ranulas can only occur from sublingual and minor salivary glands, which are able to produce saliva against a pressure gradient, while major glands downregulate salivary production when obstructed.

Ranulas can be classified as simple, when confined to the oral floor, or plunging, when the pathology extends into the neck, usually in the submandibular space, passing through mylohyoid and hypoglossal muscles, or through a defect in mylohyoid muscle.Reference Hills, Holden and McGurk2 Simple ranulas are common during the first and second decade of life,Reference Yang and Hong3 while plunging ranulas occur frequently during the third decade of life, with a higher prevalence in specific ethnic groups, which is why a congenital predisposition has been proposed.Reference Lomas, Chandran and Whitfield4

If not treated, a ranula can cause difficulty in speech and mastication, while airway obstruction is rare. Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation and palpation; fine needle aspiration cytology and imaging assessment – by means of ultrasonography, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – can be useful when the pathology extends into the neck. While plunging ranulas are usually treated surgically via a cervical or transoral approach,Reference Lomas, Chandran and Whitfield4 treatment modalities for simple ranulas range from conservative to more invasive procedures, including marsupialisation, sclerotherapy, sutures, traditional transoral surgical excisionReference Morita, Sato, Kawana, Takahasi and Ikarashi5 or robotic transoral surgical excision.Reference Walvekar, Peters, Hardy, Alsfeld, Stromeyer and Anderson6 Definitive treatment is represented by complete excision associated with sublingual sialadenectomy, with risk of lingual nerve and Wharton's duct injuries.Reference Hills, Holden and McGurk2

Despite all these therapeutic options, the incidence of recurrence is high.Reference Zhi, Gao and Ren7 Poor outcomes may be related to a misunderstanding of local anatomy and pathophysiology principles. Harrison,Reference Harrison8 in his review, highlighted the importance of decompression of the swelling and subsequent mucosal epithelium growth, to manage ranula. Recently, Goodson et al.Reference Goodson, Payne, George and McGurk9 described a novel suture technique based on the concepts of decompression and epithelisation, with a high rate of success, low morbidity and no major complications.

We propose a novel technique, named the ‘piercing–stretching suture technique’, for simple ranulas. This represents an adaptation of Goodson and colleagues’ method,Reference Goodson, Payne, George and McGurk9 based on the same pathophysiological basis. This paper describes the preliminary results of the technique in a series of adult and paediatric patients.

Materials and methods

Fourteen naïve patients with simple ranulas underwent the piercing–stretching suture technique at the Department of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Fondazione Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (‘IRCCS’) Ca’ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico of Milan, Italy, between January 2016 and September 2019. These simple ranulas had a mean size of 16.3 mm (range 8–20 mm); 12 were located on the right side of the oral floor and 2 were on the left side. The patients consisted of 4 children and 10 adults (6 females and 8 males), with a mean age of 20.3 years (range, 7–55 years).

The inclusion criterion was the presence of a simple ranula lying into the oral floor superficial to the mylohyoid muscle, as confirmed by ultrasonography (performed using a Hitachi H21 ultrasound transducer probe, with an operating frequency of 7.5 MHz; Hitachi High-Tech Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). All patients with clinical and radiological evidence of a plunging ranula or previous oral floor surgery were excluded from the study. A clinical diagnosis was made on the basis of oral inspection and palpation. An MRI assessment (carried out using an Achieva 3.0 Tesla TX scanner; Koninklijke Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands) was performed when the extension of the ranula could not be clearly defined by clinical and ultrasonography examination.

The study was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and parents of the children comprising this case series. The consent procedure was approved by the local ethics committee.

Surgical technique

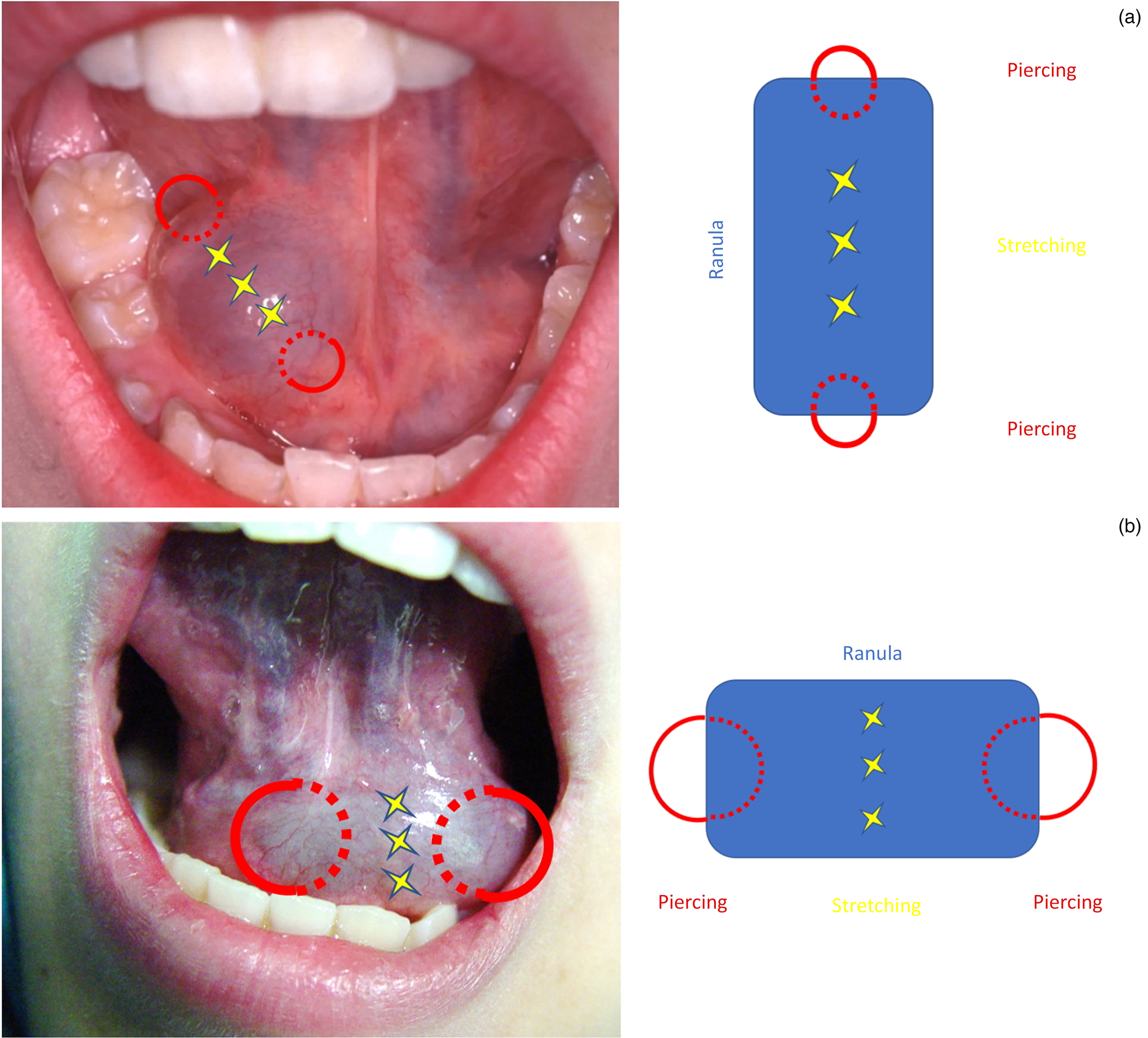

Wharton's duct is dilated and cannulated by means of lacrimal dilators and probes (Bowman probes, size 0000-6; Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany), for identification purposes. Subsequently, two interrupted, 2-0 gauge silk sutures are placed through the edges of the ranula. These create loose rings (Figure 1a, b) that favour saliva leakage from the pseudocyst (Figure 1c), prevent swelling of the cavity and aid the scarring process (piercing). Adjunctive 2-0 gauge or thicker silk sutures (up to four sutures depending on the size of the ranula) are placed between the first two loose sutures (Figure 2a, b), in an orthogonal or parallel direction, through the edge of the sublingual gland around the origin of the ranula (stretching). The leaking salivary unit is caught within the sutures and strangulated. The sutures help to decompress the ranula, and cause fibrosis and scarring of the sublingual gland at the site of the salivary leak (Figure 3a, b).

Fig. 1. Placement of piercing sutures. Two interrupted 2-0 gauge silk sutures are placed through the edges of the ranula to create loose rings (a & b) that favour saliva leakage from the pseudocyst (c, black arrow).

Fig. 2. Placement of stretching sutures (a & b).

Fig. 3. Diagram showing the placement of sutures. Piercing sutures (red circles) help to decompress the ranula. Stretching sutures (yellow stars) cause fibrosis and scarring of the sublingual gland at the site of the salivary leak. Stretching sutures can be placed in an orthogonal (a) or parallel (b) direction depending on extension of the ranula.

In order to check the patency of Wharton's duct, a diagnostic sialendoscopy (Figure 4a) can be performed with the patient in a half-seated position, with their head on a headrest turned towards the surgeon and mouth held open by a small gag (in cases of general anaesthesia). Endoscopic exploration of the ductal system (Figure 4b) is performed using a semi-rigid sialendoscope with an outer diameter of 0.8 mm (Erlangen sialendoscope; Karl Storz).

Fig. 4. A diagnostic sialendoscopy can be performed (a) to check the patency of Wharton's duct (b).

Post-operative follow up

Only the children received antibiotic prophylaxis (amoxicillin sodium and clavulanic acid, 50 mg/kg/day for 7 days) and, when necessary, steroids (betamethasone, 0.2 mg/kg/day) to reduce possible oedema of the floor of the mouth. All patients followed a cold semi-solid diet for 5 days. They were clinically re-examined after one week, two weeks and one month, in order to evaluate the course of wound healing, the absence of recurrence and the presence of a clear secretory flow from Wharton's duct. If still in place, sutures were removed one month after surgery. Patients were interviewed telephonically six months after surgery to verify the clinical course and check for any symptom recurrence.

Results

Fourteen patients with oral floor ranulas (mean size of 16 mm (range, 8–20 mm); 12 on the right side and 2 on the left side) successfully underwent the piercing–stretching suture technique. Four patients were children and 10 were adults. The patients’ ages ranged from 7 to 55 years, with a mean age of 20.3 years. Six patients were female (two children) and eight were male (two children). In all but one patient, diagnosis was based on clinical and ultrasonography evaluation; MRI scans were available for one patient.

Surgery was performed under local anaesthesia in adults (10 patients). General anaesthesia was utilised in two paediatric patients, with sedation in the remaining paediatric patients (using a bolus intravenous injection of 1 mg/kg propofol and 1 mcg/kg fentanyl, maintained with a continuous infusion of 2 mg/kg/hour propofol; another bolus injection of 1 mg/kg propofol was administered in cases of reversion to full arousal).

The technique was successful in terms of oral floor swelling recovery (Figure 5a–c) for all patients. The patency of the submandibular duct after the placement of sutures was checked by means of bimanual gland palpation and squeezing, with subsequent evidence of clear salivary flow from the ostium. In two doubtful cases, both paediatric patients, a diagnostic sialendoscopy was performed to confirm the patency of Wharton's duct. Complete recovery of the ranula after one treatment was obtained in all but one of the patients. This latter patient had a recurrence two months after surgery and underwent a new suture technique, with a final successful result.

Fig. 5. A right oral floor ranula in a female patient (a). Placement of sutures (b). Oral floor one month after surgery (c).

No major complications (in particular, no lingual nerve or Wharton's duct injuries) occurred in any of the patients. No infection, haemorrhage or haematoma were reported. No patients complained of soreness or pain during the healing process. After one month, sutures were still in place in 10 patients and were removed in the out-patient department. All patients were free of symptoms and oral floor swelling after a mean follow-up time of 22 months (range, 6–44 months).

Discussion

Definitive treatment of an oral floor ranula mainly consists of transoral removal of the salivary sac or pseudocyst and sublingual sialadenectomy,Reference Than, Rosenberg, Anand and Sitton10 with risk of injury to the lingual nerve (11 per cent) and submandibular duct (2 per cent).Reference Goodson, Payne, George and McGurk9 As this condition typically affects children, the choice of a minimally invasive therapeutic strategy, although related to a higher risk of recurrence, is counterbalanced by the risk of an untoward effect. In this regard, minimally invasive surgical and medical alternatives include: marsupialisation with or without packing, sutures, laser ablation, and sclerotherapy. Unfortunately, these procedures have been associated with a high rate of recurrence, ranging from 13 to 66.7 per cent.Reference Zhao, Jia and Jia11

Goodson et al.Reference Goodson, Payne, George and McGurk9 recently described a suture technique based on the principle that ranula recovery is favoured by decompression of the cyst and subsequent mucosal epithelium growth, as described by Harrison.Reference Harrison8 We modified this technique by adding the piercing suture to the stretching with seton; by positioning two additional silk sutures to create loose rings, saliva flushes out from the pseudocyst, thereby downgrading continuous pressure of the sublingual glands and preventing any further swelling of the oral floor.

Our technique was successfully applied to all patients; only one adult patient underwent a new suture technique for a recurrence that occurred two months after the first procedure. Recurrence may be secondary to a limitation in salivary leakage that occurs as a result of: the precocious loss of the ‘piercing’ sutures which guarantee the planned fistulisation, and the interruption of the fibrotic process favoured by the stretching suture.

The procedure is minimally invasive and repeatable in cases of recurrence; no anatomical sequelae of the oral mucosa were observed during follow up. Moreover, the technique does not preclude any further and more aggressive management of ranulas with traditional transoral sublingual sialadenectomy and pseudocyst removal. No major complications occurred in our patients; nevertheless, the risk of possible injury to the lingual nerve or damage to Wharton's duct (variably reported in the literature for other surgical proceduresReference Zhao, Jia and Jia11) exists.

The intra-operative use of Bowman dilators or, eventually, a sialendoscopic test of Wharton's duct (at the end of the procedure in doubtful cases with an unclear salivary duct flow after gland squeezing), are useful steps to orientate the surgeon towards an adequate suture technique.Reference Capaccio, Canzi, Gaffuri, Occhini, Benazzo and Ottaviani12 The application of sialendoscopy is important, especially in the paediatric field where adequate long-term experience is mandatory.Reference Capaccio, Canzi, Gaffuri, Occhini, Benazzo and Ottaviani12 Sialendoscopy guidance for the management of a plunging ranula through the oral floor has already been described.Reference Truong, Guerin and Hoffman13 The availability of the sialendoscopic system in the operating field is always welcome, although the absence of complications after this minimally invasive procedure does not necessitate its presence in the surgical set.

General anaesthesia was necessary only in two paediatric patients. As no technical difficulties have been encountered during sedation with propofol, we support the use of local anaesthesia or, eventually, sedation, for this minimally invasive procedure.

• Simple ranulas are oral floor pseudocysts originating from the sublingual gland

• Minimally invasive surgical techniques have been proposed, but so far have been associated with a high recurrence rate

• Definitive treatment involves excision and sublingual sialadenectomy

• The piercing–stretching suture technique is a non-invasive option for simple ranulas

• Sialendoscopy can be useful in placing sutures, especially in paediatric patients

Conclusion

The piercing–stretching suture technique is a safe and minimally invasive surgical option for the treatment of simple oral floor ranulas. Long-term follow up with a larger series of patients will further support the value of our technique as a feasible treatment for naïve patients with ranulas.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Prof Mario Mantovani for his technical support.

Competing interests

None declared