1. Introduction

There is widespread discomfort at an apparent lack of ethics in the modern finance sector, with blame partly being apportioned to education (Bennis & O’Toole, Reference Bennis and O’Toole2005; Khurana, Reference Khurana2007; Navarro, Reference Navarro2008; Boatright, Reference Boatright2010). While there is agreement about the need for an ethical actuarial education, with ethics appearing in the international syllabus, there appears to be some confusion, and perhaps disagreement, about its content. At one level, we share so little common agreement on ethics that it is scarcely remarkable for a discussion on “ethical dilemmas in pensions” to begin with basic questions such as: “Isn’t ethics just a matter of opinion? Why should I be ethical?”Footnote 1 . Underlying these questions is a common misconception that ethics is an often arbitrary constraint on personal preferences and corporate profitability.

This paper suggests, however, that we can find much common agreement in a framework that includes integrity and the four cardinal virtues with our professional vocation to serve the public interest. Such an agreed framework could be used in actuarial training to develop a common vocabulary and understanding of ethical issues that could dispel these misconceptions. The suggestions owe most – in the academic literature – to the philosopher, Alasdair MacIntyre (Reference MacIntyre1999, Reference MacIntyre2007), and other proponents of the theory of virtue ethics, who specifically recognise the role of professions and their ethical codes. The need for a common vocabulary is particularly relevant to the International Actuarial Association’s (IAA) review of its educational syllabusFootnote 2 .

Part two of this paper opens with some explanations of the difficulties in teaching ethics, and why it is necessary. It then explores the four cardinal virtues of courage, justice, prudence (wisdom) and self-control, which together with the unifying virtue of integrity, enable us to strive for the life well lived. This model of the classical virtues can however seem cold and unforgiving, and particularly needs to make allowance for weakness and ethical failures. Failures also bring with them the need for regulation, which itself should not be too unforgiving. A more human approach is suggested by Braithwaite’s (Reference Braithwaite2002) responsive regulation and restorative justice, which are compatible with the flourishing society envisaged by virtue theory.

Potential alternatives to the virtue framework suggested, and some of the arguments against them, are covered in part three. The virtues fit fairly comfortably with the ethical imperatives of the major religions and the professional virtues required by our actuarial education system. They are not inconsistent with the teleological (often utilitarian) and deontological ethical theories commonly taught in ethics courses, but MacIntyre (Reference MacIntyre1984) raises objections to the use of these theories, in education particularly. He explores the consequence of the paradox that the ethical theories provide different justifications for ethical values, while there is in practice little disagreement about the values themselves. A further problem exists where attempts to be value free lead to a perversion of values, as argued by Polanyi (Reference Polanyi1962) and Ghoshal (Reference Ghoshal2005), amongst others.

Virtue theory suggests that training in virtue has to take place in a community of virtue, of which the professions provide an exemplar. Part four considers the role of members of these communities, particularly teachers, in supporting students while their ways of thinking are challenged and their identities transformed. Learning ethics cannot merely be an intellectual exercise as it involves expanding and clarifying one’s personal aspirations. Students will make easier progress if they are given personal support as they negotiate the challenging concepts and applications that make up the theory and practice of actuarial work. The professions have always recognised this, and include a considerable element of mentoring in their educational or formation process.

2. A Taxonomy of Virtue

This part attempts to show how a framework of integrity and the cardinal virtues can (indeed already does in part) provide a shared language for communicating ethics that could usefully be used more explicitly in actuarial education, as well as being used more widely in continuing professional development (CPD).

2.1. Why ethics are problematic

Even if we agree they are necessary, why is it that we have difficulty with discussing ethics, in company or in the classroom?

2.1.1. It is difficult to agree on definitions…

Ethical standards are difficult to define, universally debated and seem impossible to measure. They therefore fall short of being meaningful in philosophical traditions such as positivism. We do however need some criteria for determining what has value (is “good”), or else there are no grounds for any enquiry or communication. Positivism, for instance, ascribes value to science and understanding – even if it belittles other elements of traditional ethics, even wisdom (Thomson, Reference Thomson2004).

Ethical terms do have limited precision. For instance, I may argue that justice is a universal standard, but there are seven definitions on http://dictionary.reference.com and they are largely interchangeable with equity, treating people fairly, and even righteousness. One reason for this is that the concepts have been used so widely and for so long that there is no possibility of obtaining an unequivocal definition. The variety of vocabulary is inevitable. Those sympathetic to positivist positions might note that even in science, we get a variety of usagesFootnote 3 .

The other element of this imprecision is that there is normally a range of what should be seen as acceptable behaviour. On questions of justice (fairness), for instance, it is impossible to give a precise measure for a fair charge for wholesale investment management of an ordinary pension fund. However, there is a range which most people would agree was reasonable (say under 50 basis points) and one which all would agree to be extortionate: say over 2% pa. Drawing the line (or lines) is difficult, but it sometimes has to be done.

2.1.2. … but not impossible to define

Some unethical behaviours can readily, and are frequently, judged as unacceptable – even criminal – and the perpetrators judged accordingly. While the law is not all universally enforced, much is. Similarly, professional bodies do enforce standards of personal competence and integrity. The existence of the law and millennia of jurisprudence confirm that some ethically unacceptable behaviour can be identified and defined, but that it is a complicated matter!

2.1.3. Ethics are a personal challenge

External enforcement by the law or the profession is however a blunt and often ineffective instrument. Stansbury & Barry (Reference Stansbury and Barry2007) discuss how laws and regulations can call forth counterproductive reaction. External enforcement suffers from inconsistency, can make errors of omission and commission, and is often too late. It is personally unpleasant – whether we are judge, accuser or accused. It can only work if supported by a large majority or otherwise by force, and is vulnerable to capture by vested interests and to sliding community standards.

Ethical failures in leaders are more likely to escape legal sanctions with potentially disastrous consequences for companies (Messing et al., Reference Messing, Sugarman and Cramer2006) and states (Rotberg, Reference Rotberg2010). When institutions fail, the antidote has to be found in the moral fibre of individuals, preferably acting in concert, who can call leaders to account. Actuaries with experience will applaud the International Actuarial Association’s riposte to a suggestion that there can be organisational arrangements to curb strong personalities: “The only thing that can offset a strong personality is another strong personality” (2014: 6). By strong, they surely meant virtuous: with the integrity, courage and wisdom to stand up to corrupting influences.

Tangibly present in many discussions on ethical issues, is that while we may aspire to ethical standards, we fall short of our own aspirations. Any discussion that has direct application therefore has the potential for mutual recrimination, for stirring up feelings of personal guilt, and for displays of unpleasant criticism of others. Tangney et al. (Reference Tangney, Stuewig and Mashek2007) review psychological research on shame and guilt and their impact on feelings. Our talk can easily be deflected into comfortable but anodyne platitudes. It can also become equally boring academic discussion of who thought what. Alternatively the hidden discomfort can be deflected into politics, which may itself get unpleasantly heated.

Avoiding the subject is not however the answer. Shu et al. (Reference Shu, Gino and Bazerman2011) reaffirm, from experimental evidence, the long held view that “people routinely engage in dishonest acts without feeling guilty about their behaviour”, but “increasing moral saliency by having participants read or sign an honour code significantly reduced or eliminated unethical behavior”. We need basic ethical training and regular reminders. We already have them in the ethical component of basic actuarial training, in professional codes of conduct, and in regular reminders in our mandatory CPD programmes. This paper suggests that there are good reasons to give them greater salience, and base them on a framework that will provide a richer common vocabulary.

2.1.4. Vested interests or shamelessness

The discussion thus far may have some readers asking whether justice is a relevant concept and whether it is universally acceptable. Justice is singled out because it governs our impacts on others. The question of universality is deferred until part three below.

On relevance, there is a range of views. Some people may value personal effectiveness and economic wealth over justice in some cases. Economic performance is necessary for human flourishing, so it is only the idea that this may legitimately require injustice that is problematic. But even Ayn Rand (Reference Rand1988), with her significant influence over some business people, aspires to integrity and justice – even if compassion is reserved for innocent victims. People have legitimate differences on what constitutes material injustice, but debates about these can be situated within the model. Such debates should of course – as in the Greenspan apologyFootnote 4 – acknowledge human frailty especially among the powerful.

This may not be a sufficiently strong response to more extreme views. Many business people do argue that it is the role of government to maintain justice, and that the individual or firm fulfils its obligations to society by conforming to the law – even at the minimum level required. Giacalone & Promislo (Reference Giacalone and Promislo2013) document, however, a “mindset that disparages virtue” and the “stigmatization of the good”: how some business people and students have come to believe that “virtuous individuals are dangerous to material goals and should be castigated”. This can go with views that “demonizes” the poor and needy, especially those on welfare and can be guilty of blaming the victims of various forms of oppression.

Where it is not a cloak for vested interests, the view that current policy is necessarily ethical is based on a dangerously narrow perspective. The arguments are those of collaborators – with Nazism, Communism, Apartheid or other instruments of terror, and of exploitation of the vulnerable. It begs the question of who makes the law and designs its implementation. Drucker (Reference Drucker1969: 228) warns: “If the decent and idealistic toss power in the gutter, the guttersnipes pick it up”.

We would not expect even precisely defined ethical standards with almost universal acceptance to be always followed. Those who fall short of the standards may be as likely to deny the value of virtue as to admit that they have failed. Ariely (Reference Ariely2013) is a recent and popular exposition of the disconcerting tendency to attempt to avoid punishment or disapproval from our peers, and to rationalise our own behaviour. Bellis (Reference Bellis2000) records some just, and some more cynical, criticisms of professional hypocrisy over the past century and more. These need to be acknowledged, but hypocrisy at least pays homage to virtue. To continue to believe that justice is irrelevant is shameless, a perversion of clear thought, to become a renegade from society, let alone from professions that aspire to ethical standards.

2.2. The Cardinal Virtues

The cardinal virtues describe qualities that cover three elements of what constitutes a good life: good character, which leads to ethical behaviour, and to a contribution to the flourishing of society. They have been out of fashion for some decades for various reasons. One of the better known critiques is repeated by Kohlberg (Reference Kohlberg1970), who criticised the traditional “bag of virtues” as lacking coherence, and as restricting personal development as they are external and rule based (Hamm, Reference Hamm1977). Hamm is persuasive in arguing that Kohlberg is rejecting rules abused by those in authority, rather than genuine virtues.

Another criticism is that empirically, people are inconsistent in their behaviour, and so it is meaningless to talk about developing virtues and of virtuous characters. Harman (Reference Harman1999) is one who makes this extreme case in the academic literature. The extreme case is rebutted by Peterson & Seligman (Reference Peterson and Seligman2004). While acknowledging that there is significant inconsistency, they claim that “correlations of honesty scores across situations are higher than between cigarette smoking and lung cancer…” (Peterson & Seligman Reference Peterson and Seligman2004: 59). Solomon (Reference Solomon2003) and Luban (Reference Luban2003) also respond to these criticisms, exploring some of the many ways in which we fall short of the virtues while still affirming that they reflect our deepest aspirations.

2.2.1. A framework

While MacIntyre, Carr, Hamm and other defenders of the traditional virtues seem to be at some pains not to attempt to impose any structure on the virtues, this section does suggest a framework for classifying the moral or cardinal virtues. The framework is fuzzy, in that the different virtues are vaguely defined and are intertwined rather than mutually exclusive, and it does not claim to be comprehensively exhaustive. The structure does however capture something of the different nature of some of the virtues to which, it is argued, people universally aspire – and to identify those that need to be encouraged in an educational system. The framework may lead to something of a different understanding of its elements, but it does not seem to do violence to their common usage.

We have inherited the four cardinal virtues from the classical philosophers. Though they are ancient concepts, they are supported by recent research as having a coherent meaning.

-

∙ Self-control curbs our personal appetites and cultivates (by practice) our aspirations, shaping our character and the habits of a good life. As self-regulation, it has been intensively studied by psychologist Mischel, whose The Marshmallow Test (Reference Mischel2014) is currently a best seller. He confirms that self-control is a character trait that can be developed throughout life, although its manifestation is often situation specific. Higher scores in young children appear to lead to better academic results, better earnings and longer marriage relationships – 20 years later. Relevant particularly in the workplace, Bandura (Reference Bandura1993) talks about the development of self-efficacy, which is the attitude needed to overcome the feelings that accompany personal setbacks.

-

∙ Courage fulfils a similar role in protecting our character and choices against external forces – attempts by others to dominate us. It can be physical, but it is moral courage to maintain personal integrity and stand up to domineering others that is relevant here. Hannah et al. (Reference Hannah, Avolio and Walumbwa2011) consider the exercise of moral courage in the military. Although not the intention of their research, they confirm that courage is a characteristic that can be recognised and that it can be encouraged by appropriate leadership. Gentile (Reference Gentile2010), although not labelling it courage, covers how we can train ourselves to “give voice to values” in difficult ethical situationsFootnote 5 . This courage runs along similar lines to the courage required for non-violent direct action as epitomised by Gandhi.

-

∙ Justice is traditionally defined as giving other people their due; treating them fairly. It incorporates tolerance and mutual respect. It is the social virtue that should govern the use of power over others. Sandel (Reference Sandel2010) provides an easy overview of the main theories of justice, coming down at the end to the virtue ethics view. Asher (Reference Asher2010) summarises a traditional view of justice as a procedure that balances the interests of different stakeholders and seeks to maximise just deserts, equality, liberty, and people’s specific needs in an efficient manner. That paper then applies this to actuaries’ work in the design of benefits and social security systems. Asher (Reference Asher1998) applies the traditional view to ethical issues in investment.

-

∙ Wisdom is making good decisions in the face of limited knowledge and uncertainty. As the primary intellectual virtue it has a role in the development and exercise of each of the other virtues. It requires both technical expertise in order to know the context, and the choice of appropriate criteria to produce a good decision. Staudinger & Glück (Reference Staudinger and Glück2011) provide a recent summary of psychological research, considering the cognitive, emotional, and motivational processes involved and identifying ways in which wisdom can be developed. There remain differences of opinion, but they can be seen to enrich the concept rather than undermine it. Staudinger and Glück, for example, refer to Sternberg, who

found that university professors from different disciplines agreed only partly in their conceptions of wisdom. Art professors defined wisdom largely as a balance of logic and intuition, philosophy professors focused on deep and nonbiased thinking, and business professors emphasized awareness of limitations and on long-term perspectives (Reference Sternberg1985: 219).

The cardinal virtue is sometime called practical wisdom, emphasising that it goes beyond knowledge and mere theory. It is also called prudence, which would reflect the views of the business professors and its application in situations where there is uncertainty.

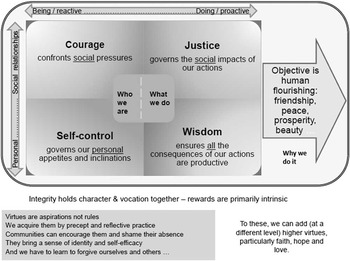

Figure 1 provides a taxonomy of the virtues: providing some explanation as to why they are normative. The two virtues on the left (self-control and courage) defend our integrity from internal appetites on the one hand and external threats on the other. They defend who we are. Those on the right (justice and prudence) should govern what we do if we want to prosper in society; justice covers how what we do affects others, while wisdom, as the intellectual virtue, considers all the consequences of our actions. The bottom two (self-control and wisdom) do not need a social context – they would be required by Robinson Crusoe if he were the only one on his island. The top two (courage and justice), however, relate to relationship with others. The arrow on the right indicates that our actions have meaning to the extent that we participate, where possible, in building a flourishing community.

Figure 1 The cardinal virtues here.

Holding the virtues and indeed our lives together, is integrity – indicated by the line around the diagram. Integrity is more than honesty, it is concerned with “internal connections” between who we are, what we say and what we do, our motivation and our actions, and means and ends. In an educational and work environment it is concerned with intrinsic, rather than instrumental, motivation. As with the cardinal virtues, integrity has social as well as personal value: Ones & Viswesvaran (Reference Ones and Viswesvaran2001) report on the variety of integrity tests used in selection of personnel and their (relative) success in predicting desirable employee behaviour.

The cardinal virtues can however be cold and unforgiving on their own. For a start, integrity needs to include a proper humility to acknowledge failures and weaknesses. Justice needs to be supplemented with mercy; wisdom to include reasonable doubts, self-control and courage need patience. The structure of Figure 1 can accommodate these by envisaging another dimension of perhaps higher virtues with a similar structure. Such higher virtues could accommodate the three theological virtues – faith, hope and love that Aquinas (Reference Aquinas1275/Reference Aquinas2006) took from St PaulFootnote 6 to make a total of sevenFootnote 7 . These can be defined variously. If faith is required in the face of reasonable doubt, it might be seen to belong with wisdom; to the extent it is faithfulness it is an aspect of integrity. Love links easily with extending justice to include mercy and contributions to a flourishing society. It can be described as compassion, care or humanity. Research reported in the next section shows that people link hope with self-control, which ties in with Bandura’s self-efficacy that invariably goes with some optimism. These virtues do go somewhat further than the virtues that we might expect a professional actuarial education system to impart, although it should not close the door to higher aspirations.

Why do we value the virtues? They do lead to the good life in ourselves and in society – all other things being equal – but they have value in themselves, so we pursue them for their own sake. They are promoted, and in cases required, by communities as the foundation of prosperity and peace, but they are also constitutive of personal growth, happiness and peace. The virtuous person is one who has trained him or herself to want to do what is right. The virtues justify themselves in that they are inherent in our natures as persons and members of society. Just as our bodies attain the virtues of strength and health with proper food and exercise, and our intellects acquire understanding with proper academic training and personal application, so our characters develop self-control, courage, wisdom and justice with appropriate direction and encouragement. Peaceful and prosperous societies similarly require (indeed consist of) virtuous citizens and institutions.

Carr puts the arguments for education of the virtues in a way that may resonate best:

… no really rational being could understand fully what a quality like courage, temperance, justice or compassion is and yet fail to want to possess it. From this point of view, since the virtues are not innate but entail both proper habit formation and the development of reason, it is clear that it is squarely within the responsibility of all concerned with the socialisation and education of children – parents, teachers and others – to ensure that such habituation and instruction takes place.

There are legions of young people, who … continue to perceive what is admirable about virtue through the fog of lies that have been woven about her, and live lives of self-respect, decency, sobriety and genuine altruism. There are far too many others who have been blinded by the rhetoric, who have come to believe that morality is a matter of reluctantly doing one’s duty where this cannot be avoided, and otherwise going to the devil (Reference Carr1991: 255).

2.2.2. Positive psychology

If this framework is to be of use, its constituents need to be universally intelligible in one form or other. Peterson & Seligman (Reference Peterson and Seligman2004) outline the findings of positive psychology in identifying whether virtues (what they also call character strengths) are can be universally understood as concepts. Most extensive is the analysis of the 120-question Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS) survey, which has been completed by over a million respondents from 75 countries. McGrath finds significant convergence of responses: “Even the smallest correlation with the US profile of ranked strengths that emerged in this study meets the common standard for a large effect” (Reference McGrath2015: 51). When he uses cluster analysis on a smaller sample (McGrath, Reference McGrath2014), he finds five clusters that can be mapped to the four cardinal virtues, integrity and the higher virtues.

The questionnaire does not ask people to group the virtues, but to identify their own values. The results arise because people who have the one virtue in the cluster think that they also have the others rather than whether they see them as similar. The strengths within each cluster are thus mutually supportive. It should also be noted that the questionnaire was drafted with an awareness of Aquinas’s seven virtues and so the results are not proof that they provide the best classification of universal values. Peterson & Seligman (Reference Peterson and Seligman2004), however, explain the care that they have taken to be open to alternative values and classifications. The VIA websiteFootnote 8 itself maps the list of strengths onto six virtues (the cardinal virtues without Integrity plus Humanity and Transcendence), based on previous cluster studies and the earlier evaluation of religious traditions by Peterson & Seligman (Reference Peterson and Seligman2004).

Positive psychology can be criticised for being purely descriptive (Beadle et al., Reference Beadle, Sison and Fontrodona2015), and the results in Table 1 merely show that the elements of the framework suggested in Figure 1 are not meaningless as suggested by some such as Kohlberg. They are however aspirational. The higher virtues listed also perhaps suggest how we might expand our understanding of the nature and benefits of the classical virtues. Perhaps social IQ, humour and creativity can contribute to the appropriate expression of courage. Gentile (Reference Gentile2010) incorporates just this. Similarly, our understanding of self-control can be extended positively when it is related to healthy self-efficacy and future mindedness.

Table 1 Mapping the values in action inventory of strengths to the virtues.

The role of integrity also needs some elaboration. It is not classified as a cardinal virtue, and some writers group it with one or other. In the VIA-IS study, apart from honesty, the other strengths in the integrity cluster seem to belong elsewhere. Perspective – said by McGrath to be a simile for wisdom – loads primarily in the restraint cluster, and secondarily onto courage. Perseverance has a strong secondary loading onto self-control. Judgement might be expected to tie in with wisdom, or with justice, as requiring consideration of alternative points of view. These overlaps are however consistent with seeing integrity as a unifying virtue that unites intellectual insight with all our actions: self-control and courage to preserve our character, justice that further displays consistency in treating others as we would want to be treated, and an intrinsic motivation that unites means and ends.

2.3. Responsive regulation and restorative justice

Not only does integrity require us to acknowledge mistakes, but our understanding of virtue is incomplete without a view on law and regulation – including punishment and rehabilitation.

One approach to ethics is characterised by MacIntyre as

Society is understood as an arena of rival and competing interests and what morality supplies are rules which from a neutral and impartial point of view set constraints upon how these interests may be pursued (Reference MacIntyre1984: 498).

While common, such as view is unhelpful. On the one hand, few are truly single minded in their pursuit of self-interest, while on the other, rules are seldom neutral or impartial and provide limited constraint unless enforced by the just and courageous. A more helpful view is to see society, and professional communities, as places of collaboration and of friendship – and moral or ethical rules as a means of socialisation. Communities develop institutions that contribute to flourishing, and these must include rules to protect members against harm from the ethical failures of other members. Such rules need enforcing, but the ideal, in a flourishing society, is that this will not be frequent.

Braithwaite (Reference Braithwaite and Braithwaite1995) describes an approach to regulation that is explicitly based on the view that the role of regulation is to bring the best out of people. He calls for responsive regulation leading, where necessary, to restorative justice.

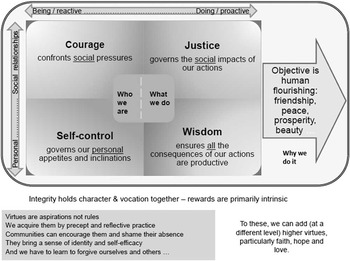

As an ideal, responsive regulation is self-regulation in the first place; people and organisations are responsible that they do no harm to themselves or others. Figure 2 illustrates

The left hand side of the pyramid represents the stances that can be adopted by taxpayers … ( Braithwaite, Reference Braithwaite and Braithwaite1995 ) … The right hand side presents the pyramid of regulatory strategy which is described in … (Ayres & Braithwaite, Reference Ayres and Braithwaite1992).

Figure 2 Responsive regulation here. Taken from Australian Taxation Office (1998: 23).

Restorative justice aims to preserve the community by reintegrating offenders. Rather than avoiding shame (which as noted in section 2.1 is common), there is need for reintegrative shaming, which aims at rehabilitation, as against stigmatising shame that excludes and further belittles those who fail. It emphasises the responsibility to make good any harm that has been done. Punishment is not ruled out as it acts as a disincentive and it recognises the harm done to victims where adequate compensation is impossible. The aim of restorative justice, however, is to avoid vicious cycles of revenge, and the emergence of dysfunctional counter-cultures – such as gangs and terrorist groups.

This is not the place to explore the full implications of the idea of restorative justice, which Braithwaite has applied in areas as diverse as juvenile crime, the regulation of age-care providers and financial institutions. The approach advocated requires some personal maturity, but – for those who fear that this may lead to a drop in standards – Murphy and Harris (Reference Murphy and Harris2007) confirm the earlier hypotheses of Braithwaite & Braithwaite (Reference Braithwaite2001) that reintegrative shaming leads, inter alia, to better tax compliance.

In a similar vein, Moore (Reference Moore2012) suggests a number of organisational strategies to “crowd in virtue” and intrinsic motivation, based on experimental results of “social dilemma games”. These are also built on recognising the responsibility of all members of an organisation to contribute actively to its social purpose.

Recognising our propensity to fail is to face the truth. It does not mean we need harsh zero tolerance policing to prevent standards dropping; recognising failure is however, a necessary element of strategies for raising them.

3. Reconciliation With Other Approaches

Differences in personal and cultural values are often seen as an obstacle to the teaching of ethics, as it is believed that the values are arbitrary and would therefore be wrong to impose on others – especially the young. This, however, is to confuse tastes, about which there should be no debate (which are neutral as to their impact on human and social flourishing), social norms that are arbitrary and may differ from society to society without harm, and moral or ethical values that have personal value in themselves and are essential for social cohesion.

This part attempts to uncover the most obvious alternatives to virtue ethics and finds that there is little evidence of huge differences in values in traditions or theories of the good. While far from exhaustive, it is suggested that the framework above is flexible enough to incorporate the differences that do occur.

3.1. Across religious and cultural traditions

The convergence of values across cultures has long been recognised – MacIntyre in particular applauds Aquinas’s (Reference Aquinas1275/2009) harmonisation of Greek philosophy and Christian theology, incorporating both Jewish and Muslim views. Yu (Reference Yu2013) writes of the “mirror of virtue” in Confucian thought. Wade (Reference Wade2010) finds the virtues paralleled in Islam and Buddhism. Dahlsgaard et al. (Reference Dahlsgaard, Peterson and Seligman2005) and Peterson & Seligman (Reference Peterson and Seligman2004) explored the virtues in these and other traditions – considering in particular areas of difference that might be thought to undermine their classification system, which is based on the classical virtues.

One of the differences arises from the value that most religions and many cultures place on humility, duty and submission to the existing order – both political and religious. This stands in some contrast to modern secular views more likely to value Aristotle’s “magnanimity”, or ambition that aims at wealth and success. Attempts to reconcile this tension go back to Aquinas at least. Keys develops Aquinas’s proposal that magnanimity and religious humility are in fact “twin virtues”:

Humility moderates excessive or misplaced hope, curbing the “impetuosity” of that passion and hence removing an obstacle to prudence … Magnanimity arouses and nurtures hope, motivating and directing a person to attempt the good of which he or she is capable. Every human being, mortal and limited and fallible, needs both of these character traits in order to act well on a consistent basis … (Reference Keys2008: 219).

This view would tie in with the idea that hopeful future-mindedness ties in with self-control. Like integrity, a proper humility, however, seems to have a role in all the virtues: an awareness of what we do not know in wisdom, and an appropriate respect for others in matters of courage and justice. It can perhaps be included as an element of integrity, which requires the pursuit of clarity as to our own abilities and importance. This can be seen to be consistent with the view, repeated in Aquinas, that a pride that rejoices in our personal superiority is the main enemy of all the virtues; it distorts all our insights and our motivations and leads to the domination and unjust oppression of others.

The conflict is therefore perhaps more apparent than real, except when humility is suggested for some and magnanimity for others. Both can be used as manipulative concepts to dominate or justify the wealth and prestige of the fortunate.

3.2. Cultural differences and virtue

Also in the psychology literature, but entirely distinct from positive psychology, Hofstede (Reference Hofstede2001 – inter alia) has developed a widely used model of national culture along the dimensions of uncertainty avoidance, collectivism (versus individualism), power distance (between those with different statuses) and masculinity (versus femininity). This model has developed in a variety of directions, one of which is described in Javidan et al. (Reference Javidan, House, Dorfman, Hanges and De Luque2006). Their GLOBE model adds dimensions of gender equality and future, performance and humane orientations, and splits collectivism into institutional and family scales. As discussed in Tung & Verbeke (Reference Tung and Verbeke2010) though, the additional research has revealed that, although these values differ across nations, they do so as much within national borders and over time.

This research does raise the possibility that there are alternative normative values in different cultures, and which do not obviously fit our taxonomy – in particular power distance, collectivism and status. Jost & Hunyady (Reference Jost and Hunyady2005) identify these values, and a belief in the value of hard work, as elements of ideologies that are used to bolster the position of vested interests, to the detriment of others. The ideologies are able to create support for unjust institutions – even from those they oppress – as shown by Jost et al. (Reference Jost, Banaji and Nosek2004), in their review of what they call system justification theory. We do need to recognise the tendency of what MacIntyre (Reference MacIntyre2007) calls “the corrupting power of institutions” to turn apparent virtues into unjust exploitation.

Arguments for high power distances are relatively easy to dismiss, especially in cases where those with power claim to speak for the collective. It is impossible to directly capture the “will of the people”, and those who claim to speak for others in more than a few limited matters are either deluded or manipulative. Such arguments are therefore invariably a justification for the arbitrary exercise of power, however well meaning. Similarly, the recognition of an arbitrarily higher status for men, Hindu classes, parents or authorities in general goes against equality, which is an essential element of justice. The debates about these issues can therefore be included in our taxonomy as debates about issues of justice, and of courage. A proper courage is necessary at times to resist the manipulative claims of those who would exploit notions of the collective and of personal status.

3.3. In economics and management studies

In the economics and management literature, much research is intentionally “value free”, explicitly classifying ethics as beyond economic analysis. Many, such as Sandel (Reference Sandel2012) think that this is a mistake. There are alternative theories of value such as communitarianism (Etzioni, Reference Etzioni1988), human-centred values or the ethics of care (Giacalone & Promislo, Reference Giacalone and Promislo2013) and an economic framework that better recognises complexity and ethics (Colander et al., Reference Colander, Goldberg, Haas, Juselius, Kirman, Lux and Sloth2009) but they can be incorporated into the framework suggested above. There are also those, such as McCloskey (Reference McCloskey2006), who argue that the traditional virtues provide an adequate basis for business ethics.

Treviño et al. (Reference Treviño, Weaver and Reynolds2006) reviews published research into behavioural ethics in organisations and considers the development of moral awareness, judgement and motivation. Their underlying definition of ethical behaviour is largely related to issues of integrity with little consideration of other virtues. There is a discussion of justice, but they conclude that “the link between justice and moral motivation can certainly be developed further” (Treviño et al. Reference Treviño, Weaver and Reynolds2006: 972). This illustrates how little is to be found on practical ethical questions in the literature of value free traditions. We return, however, in section 4.4 to the impact on teaching without explicitly considering ethical values.

3.4. In the actuarial and other professions

All professional codes, by definition, include ethical components. The IAA has affiliates in 92 countries, and the Professionalism Committee (International Actuarial Association, 2012) confirms that they agree on ethical standards of integrity, independence, trustworthiness and the obligation to act in the public interest. While recognising differences in emphasis, “There do not appear to be material or cultural differences in views on what is ethical. No such differences have emerged during discussions in the Professionalism Committee, nor has anyone challenged this assertion …” (International Actuarial Association, 2012: 7).

To these standards, the Financial Reporting Council adds the need for actuaries to be “robust in identifying and resisting pressures to act against their professional judgment or against the legitimate interests of users or potential users of their work” and to “speak up whenever they have reasonable concerns” (2010: 5). This is clearly a description of courage, and illustrates the value of a taxonomy that includes this virtue.

In addition to its call for actuaries to “speak up”, the Financial Reporting Council (2010) is concerned about “clear and unambiguous” communication – in particular that which identifies inherent uncertainty and the limitations of advice. This concern ties in with the oft-expressed view that actuaries are poor communicators, and provides a useful illustration of the relevance of ethical considerations in what initially appears to be a purely technical question.

Communicating uncertainty is not easy and has a technical element that needs mastery. As Taleb (Reference Taleb2005) puts it, many people are “fooled by randomness” in financial markets. Garvin-Doxas & Klymkowsky (Reference Garvin-Doxas and Klymkowsky2008) provide an illustration when they test their undergraduate science students carefully for misconceptions: the students have learnt to refer to the process of genetic mutation as random, but are not able to apply the concept and so fall back on various deterministic explanations when questioned in depth. There is therefore reason to believe that people can fail to understand actuarial communication of the unpredictability of future financial flows. To the extent that this is true, there is an ethical obligation on actuaries to ensure that their communication is not only accurate, but does not mislead those who misunderstand it.

This does not however exhaust the ethical issues. Failure to communicate may arise not from a lack of skill nor of courage, but from an ethical naivety that fails to see the role of self-interest and self-justification, both in others and ourselves. This is seldom discussed, but actuaries should recognise Eraut’s distinction between manifest and latent (hidden) motivations for communication:

The latent functions may be to keep clients happy while asserting the professional role, to maintain good relations with colleagues while preserving freedom from their influence, and to tell managers what they want to hear while keeping them off your back (Reference Eraut2000: 120).

Such latent purposes “may seek to disguise rather than to share uncertainty and risk-taking”, and “they may mislead because implicitly acquired discourse has developed for that very purpose”.

Raising uncertainty and the limitations of advice may well unsettle clients, colleagues and managers. Speaking with integrity in such situations represents a challenge: requiring not just insight, technique and emotional awareness, but also the courage and wisdom to balance maintaining one’s integrity and one’s financial or even physical security. Overall, the ethical components of professionalism appear to include all the virtues in this framework. Service of the public interest, at its minimum applies the rules of justice (such as treating customer fairly), while at best may extend to a personal vocation to contribute to financial security.

As to be expected, other international bodies such as the International Federation of AccountantsFootnote 9 , the International Bar AssociationFootnote 10 and the World Medical AssociationFootnote 11 have much the same principles as actuaries. Professionals are expected to have integrity, justice in treating their clients fairly and wisdom in having the competence to advise them appropriately. They are also expected to serve the public interest: contributing to the flourishing of society. The principles are not identical, partly because of differences in context, and partly as a consequence of the influence of interest groups, but are not explored further here.

3.5. In philosophy

There are two main groups of ethical theories that are seen as philosophical alternatives to virtue ethics, but the difference is often in the justification of why we should be ethical rather than what constitutes ethical behaviour – in the professional realm at least. Deontological theories are concerned with right actions and duties, teleological theories concerned with the relevance and success of the outcomes. Both are at least partly convincing. For an easy overview, Sandel (Reference Sandel2010) considers their relative merits and how most people cannot accept their application in some extreme cases, and repeats the arguments that justifications for ethical behaviour are not enough on their own to change behaviour. The theories also focus on actions and consequences respectively, while we need a world view that integrates both of these with our characters, and that inspires.

Nietzsche can be used as an example of why it is not possible to develop an alternative to virtue. He figures prominently in MacIntyre’s (Reference MacIntyre2007) analysis of much of contemporary culture with its dismissal, or perhaps ignorance, of the traditional virtues. MacIntyre, as many others, is impressed by Nietzsche’s demolition both of morality that is little more than a “taboo” – to mask the exercise of domination over others – and of other philosophers’ attempts to justify ethics. He does however show that it is in the nature of humanity and society that Nietzsche is unable to put anything in the place of traditional morality – in spite of his attempts to argue for “some gigantic and heroic act of the will” to create a personal ethic. MacIntyre (Reference MacIntyre2007: 133) goes on to repeat the belief that Nietzsche’s thought is thus ancestor to “irrationalisms of the Left as well of the Right” in Communism and Nazism. Attempts to create a new morality inevitably fail.

Many of the debates in philosophy are not therefore about the content, but rather about the justification and development of ethical theories, but they can be distractions. MacIntyre highlights the contradiction in what is still the “dominant conception of ethics”:

The central requirement … is then that the rules of morality are such as any rational agent would agree to. But … they are in fact unable to agree either upon the precise content of the rules of morality or upon the appropriate way in which such rules are to be rationally justified (Reference MacIntyre1984: 499).

He goes on to point out however that when it comes to practice, as we have seen in the case of professional ethics, there is significant agreement in

… medicine, law, the world of such professions as accountancy and engineering, the military. These are areas in which highly determinate types of action of great moral import have continually to be taken. It is impossible most of the time at least to fudge the question of what one is actually doing. These are also areas in which public confidence in professional activity is required and a necessary condition for such confidence is a high degree of warranted expectation. Such warranted expectation can only be provided by relatively uniform behavior on the part of those engaged in such professional activities within any one particular profession. And such uniform behavior requires a high degree of uniformity of moral education and of ways of handling the problematic. Hence the ubiquity in those areas of codes, explicit and implicit … (MacIntyre, Reference MacIntyre1984: 511).

Carr argues that the agreement we find in professional standards is not surprising

that the overall shape and outline of moral life is already given and observable in the deep grammar of any human moral discourse: that is to say, not in the variability of beliefs and values of particular human languages, but in the essential moral form or structure that any human language would need to exhibit to be a recognizable expression of any appreciably human form of life. For while the lives of particular human agents will have been shaped or guided by the beliefs and values of the particular societies and cultures into which they have been born, it is surely no less clear that the moral discourses of such diverse societies and cultures have largely common form as narratives of human striving to achieve what is perceived as good and just in opposition to what is evil and unjust. This is surely why, as modern readers, we have little trouble understanding the moral character and import of narratives as remote from us in time and cultural space as the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Mahabharata (Reference Carr2015: 24).

The consequence is set out in Carr (Reference Carr1996): the dominant approach to ethical education, of which Kohlberg (Reference Kohlberg1981) is the prime example, is mistaken. Teaching conflicting theories, and dwelling on ethical dilemmas – where there are legitimate ethical alternatives – offers little in the way of affirming or developing students’ best aspirations. It can rather distract from and trivialise pressing ethical challenges, especially – as MacIntyre (Reference MacIntyre1984) puts it – where it serves to “protect power from scrutiny”.

4. Developing Virtue at a Tertiary Level

We are concerned with the development of virtue in young adults, some years into their trajectory of ethical formation. To become actuarial students, they would have already demonstrated considerable self-control, and have laid the foundations of wisdom. Even if they have been given an education in virtue, however, they will need to consider how it plays out in new contexts, and will benefit from encouragement.

The first two sections in his part outline the need to understand the profession as a community in which to develop ethical aspirations and the role of teachers and mentors in this process. Section 4.3 expands on the link between personal and intellectual development. The last three sections consider how and where ethical issues can be included in the syllabus; the importance of narrative, and the need for appropriate assessments of progress.

4.1. The professional community

MacIntyre, inter alia, suggests that our moral development takes place in communities – with their particular laws, traditions and myths (or defining stories). Pellegrino defines professionals as those who have made a personal commitment that has led to their membership of a “community of virtue”.

On this view professionals make a “profession” of a specific kind of activity and conduct to which they commit themselves and to which they can be expected to conform. The essence of a profession then is this act of “profession” – of promise, commitment and dedication to an ideal (Reference Pellegrino2002: 379).

The relevance of community is further illustrated by the fellowship designation, which is not a certificate but signifies membership. We are more likely to say “I am a qualified actuary/fellow” than “I have an actuarial qualification”.

4.2. Ethical teachers

Induction into the community is personal, and needs personal connections: teachers and mentors. Their role is more than intellectual. Traditional education in ethics places relatively little importance on teaching philosophical theories. It is rather aimed at “educo”, Latin for “leading out”Footnote 12 students’ best aspirations and understanding.

This section reaffirms the traditional approach to teachers and teaching, suggesting that induction into the professional community falls to teachers and mentors who identify with the profession, as argued by Bennis & O’Toole (Reference Bennis and O’Toole2005) in their analysis of the failure of business education. Blakemore & Frith (Reference Blakemore and Frith2005: 161), from the perspective of educational neuroscience, suggest: “The teacher’s values, beliefs and attitude to learning could be as important in the learning process as the material being taught”. Palmer (Reference Palmer2007: 10) emphasises “good teaching comes from the identity and integrity of the teacher”. Carr and Skinner (Reference Carr and Skinner2009: 153) write “the most effective teachers are not those who simply regard the acquisition of knowledge and understanding as worthwhile for others, but those who have first and foremost grasped its value for their own personal, moral and spiritual development”.

The teachers’ role is also pivotal in the legal practical experience of Luban & Millemann (Reference Luban and Millemann1995), and in the discussion of the building of character in Hartman (Reference Hartman2006). Egan et al. (Reference Egan, Parsi and Ramirez2004) see exposure to practitioners and their real-life problems as enhancing the moral imagination of medical students. The need for appropriate encouragement from teachers and mentors is also consistent with recent research in neuro-education (Tokuhama-Espinosa, Reference Tokuhama-Espinosa2008: 368 ff).

Good teachers play other roles. Efklides (Reference Efklides2006) suggests that they can provide particular support in enabling and requiring students to reflect on their own learning. Frye (Reference Frye1982: 15) puts the more traditional view that the best teachers are those who raise questions rather than giving answers: “… to answer a question … is to consolidate the mental level on which the question is asked. Unless something is kept in reserve, suggesting the possibility of better and fuller questions, the student’s mental advance is blocked”. In the case of virtue, the students largely know what is right, but need leading out so that they give it form and voice.

One conclusion from this is that students should be exposed to a variety of teachers and mentors over the period of their training. If all are required to address ethical issues then students will be exposed to a variety of views and approaches, and be challenged to develop a personal ethical framework and commitment to professional judgement. Exposure in a single course is unlikely to be enough. There is also a need for more conscious management of the recruitment and direction of an appropriate range of committed teachers and mentors.

The other conclusion is that teachers (or material in distance learning) must explicitly raise ethical and practical issues in their teaching – even of the apparently technical subjects, and in a manner that emphasises the personal and affective. One critical area to change is identified by Dean & Beggs’s survey of what business-school teachers believe about ethics education. Rather surprisingly they find: “Major results indicate that faculty generally do not believe that they can change students” ethical behaviours, and that faculty’s conceptualisation of ethics do not match their classroom approaches (Reference Dean and Beggs2006: 15). “… Most faculty believe that ethics is a value-driven and internal construct but teach using compliance-driven and external methods” (Reference Dean and Beggs2006: 40).

Teaching ethics must therefore be personal, and represents a personal challenge to teachers, but it is not especially difficult. To take the first actuarial course as an example: can one really talk about the technicalities of compound interest without discussing the extent to which one should save to take advantage of its power, or the unfairness of credit contracts that exploit the less informed? All teachers will have made personal financial decisions in these areas, and will be aware of the pitfalls set for the unwary.

In particular, there should be some explicit discussion of integrity and its relationship to a professional identity – in every course if possible. Such discussion has to actively avoid hypocritical moralising. Mazar et al. (Reference Mazar, Amir and Ariely2008) have confirmed experimentally that we invariably think of ourselves as honest, but fail to live up to our own standards. Lecturers and mentors have to acknowledge this, and be prepared to discuss how they have addressed their own failings. The content of such discussions can be left to common sense, once we understand that such failures are universal, and need acknowledgement and perhaps some form of restitution. Howard & Korver (Reference Howard and Korver2008) suggest a format for a written set of personal standards of integrity that will generate such reminders. Ariely (Reference Ariely2013) confirms, experimentally, that we can reset our moral self-image when we have been dishonest – by rituals such as confession.

It would be unreasonable not to expect that some teachers and mentors through fear, cynicism, hypocrisy, idleness or even conviction, will undermine the teaching of integrity, and ethics more broadly. There may be no institutional means of preventing this, but if a discussion of ethics is explicitly required in every course, there is a chance that they will be a less influential minority, especially if there is encouragement to admit our own propensity to fail and self-justify.

While it is necessary to recognise personal failings and disabuse naivety, this should not degenerate into cynicism – which may start with anger at the duplicity of vested interests and the hypocrisy of the respectable – but may eventually expand to questioning all good aspirations and enthusiasms. In warning about the failures of respectability, Berger notes

It is possible to view social reality with compassion or with cynicism, both attitudes being compatible with clear sightedness (Reference Berger1973: 47).

Cynicism is an ethical failure: unjust in that it can make unwarranted and unkind judgements; unwise in missing opportunities for good, and lacking self-control in that it gives vent to arrogance.

4.3. Transformed thinking and being

Entry into the professional community requires both intellectual growth and a redefining of our identity. The intellectual process is described by Cousin (Reference Cousin2006) as being the result of learning the “threshold concepts”. These are critical ideas that lead students into identifying with a discipline, and adopting its ways of thinking. They have a “transformative” and “irreversible” impact on the students’ thinking, although students can find the process of transition emotionally disturbing.

Perry (Reference Perry1981: 79) described how his students progressed intellectually from a “dualistic” concept of right and wrong with a reliance on authority, through various degrees of “multiplicity” and scepticism, to personal commitments to truth and meaning. Such commitments, however, face the “paradoxical necessity to be both whole hearted and tentative – attitudes that one cannot ‘compromise’ but must hold together with all their tensions”. Students become anxious when the meanings and truths they had previously accepted as certain are shown to be unproven or even mistaken. This anxiety can be expressed as anger and frustration with the lecturers, and may be one reason why universities can be places of conflict.

These descriptions of intellectual transition are analogous to Piaget’s “accommodation” – as describe in Phillips (Reference Phillips1969). Learners construct new mental models to accommodate new information, as distinguished from the mere “assimilation” of knowledge. The motivation to make the accommodation arises from the “cognitive conflict” that occurs when students face new information that does not fit in with previous ideas. This conflict goes someway to explain students’ anxiety.

Fowler (Reference Fowler1981) integrates Piaget’s intellectual stages of development with Erikson’s (Reference Erikson1982) psychological, and Kohlberg’s (Reference Kohlberg1981) moral stages. Fowler described his stages as the development of faith, which he defines as a consistent commitment to “shared centres of value and power”. He suggests that the developments in the intellectual and psycho-social dimensions feed off each other. In particular, the early adult intellectual stage that includes the making of reasoned and independent judgements, follows the development of personal identity and autonomy, which feed into integrity.

Hannah et al. (Reference Hannah, Avolio and Walumbwa2011) also suggest that moral development needs to occur across different dimensions that include the development of personal identity. They identify different elements of moral judgement and action, being moral cognitive sensitivity, ownership of moral issues, personal efficacy and courage – which again include parallels with the cardinal virtues. In another parallel, Baxter Magolda (Reference Baxter Magolda2004) speaks of “self-authorship” as young adults develop autonomy and their own narrative (life story), and what could be called a vocation in the workplace.

Land et al. (Reference Land, Cousin, Meyer and Davies2005) suggest that students can be given support to navigate the discomfort of the threshold concepts, and refer to the work of Efklides (Reference Efklides2006). She suggests that students need “meta-cognitive experiences” where they reflect on the personal and intellectual difficulties of the concepts with which they are grappling. They are then more able to deal with the effort required, and with their emotional confusion. The framework suggested here is intended to be part of such meta-cognitive support, locating the virtues in personal development and actuarial practice.

Baxter Magolda (Reference Baxter Magolda2004: xxii) has followed the ongoing intellectual and moral development of her college students into their 30s, but suggests that their college experiences might have contributed more to their development if they had not seen a “lack of emphasis on developing an internal sense of self” – being a sense of integrity. McNeel (Reference McNeel1994: 30) identifies “strong longitudinal growth in moral judgment development” across 4 years of college for some groups of students. Hartman (Reference Hartman2006) suggests that by providing a language of virtue and teaching the benefits of ethical reflection, the education process lays the foundation for the building of character over a lifetime.

MacIntyre (Reference MacIntyre2007) develops the concept of “practice”, which is a “socially established cooperative human activity through which goods internal to that form of activity are realised”. For an older generation, Frank Redington was perhaps the leading expositor of the joy of developing actuarial models and understanding (the internal goods) in contributing to the profession’s objectives (for which it is socially established. The Words and Numbers papers included in Redington (Reference Redington1986) particularly illustrate the mind, transformed by an actuarial education and applied to its social challenges.

4.4. Embedding in actuarial education

If students are making these personal transitions at university, what is the impact of failing to address ethical issues explicitly – as in value free economics for instance? At best, the arguments for value free teaching arise from a desire not to unfairly influence students with personal prejudices, as in Max Weber (Reference Weber1919/2009). Weber, however, is explicitly committed to the courageous pursuit of integrity and to the development of a sense of vocation. He intends to exclude political and religious partisanship rather than ethics. Polanyi (Reference Polanyi1962) gives the lie to the suggestion that moral commitments are unacademic or unscientific. He writes of the necessity of a passionate rather than disinterested approach to finding truth. He also suggests that denying the moral basis of one’s own passions creates a “moral inversion”, where we deceive ourselves, and may begin to justify unethical behaviour. Donaldson (Reference Donaldson2012) also argues along these lines, pointing at how easy it is to miss the normative assumptions underlying theories.

Many believe that community standards of ethics have declined, and that some of the failure of moral formation results from the intellectual content of positive economics. Khurana (Reference Khurana2007) traces the academic philosophies that have most influenced business schools over the past century and driven out ideas of professionalism and responsibility. Ghoshal (Reference Ghoshal2005) argues that the consequences are:

that by propagating ideologically inspired amoral theories, business schools have actively freed their students from any sense of moral responsibility. As has been extensively documented in the literature over the last 50 years business school research has increasingly adopted the scientific model – an approach … that Friedrich A. Von Hayek described as the pretence of knowledge (75).

Mearman et al. (Reference Mearman, Shoib, Wakeley and Webber2012) provide some confirmation of this opinion by reporting beneficial effects on students’ ethical development from going beyond positive economics and teaching alternative economic theories. The profession has to take some care that its recruits are not exposed too much to reductionist thinking. Embedding ethics in the curriculum is one counter, and all goes towards increasing the role of ethics in the syllabus. Robertson (Reference Robertson2009) makes a similar suggestion for a legal curriculum, as do Rasche et al. (Reference Rasche, Gilbert and Schedel2013) for management education.

There is probably not too much to teach about the virtues in the abstract before descending into platitude, but there is more to consider and debate about how they play out in practice. Asher (Reference Asher2015) explores their personal application, and raises a number of challenges in the modern financial sector, suggesting

-

∙ As to injustices, the main concerns relate to overcharging and over-servicing, while

-

∙ On the question of the fulfilment of its social functions of allocating capital and creating financial security, there is much work that still needs to be done.

Specific suggestions are made in the Appendix as to how both the cardinal virtues together with the idea of vocation as a change of identity could be incorporated into the subjects required by the current syllabus of the IAA. The details would need to be worked out by the drafters of the syllabus, and interpreted by lecturers and providers of written material – drawing out the connections between principles and application. The order of introduction is probably unimportant, and repetition permissible because we need to keep the values salient. Boredom needs to be avoided by ensuring that the applications are real, and that they are covered with integrity – without cant or cynicism.

It should be noted that Bok was critical of attempts to “weave moral issues” into other courses and suggested the development of

problem-oriented courses in ethics. These classes are built around a series of contemporary moral dilemmas …. Prospective lawyers, doctors, or businessmen may set higher ethical standards for themselves if they first encounter the moral problems of their calling in the classroom instead of waiting to confront them at a point in their careers when they are short of time and feel great pressure to act in morally questionable ways (Reference Bok1976: 28).

George (Reference George1987) reports that Bok’s article was the precursor to a significant increase in ethics courses in US business schools. One such is the popular Harvard course that provides the basis for Sandel (Reference Sandel2010). There appears, however, to be no evidence to date that this approach has led to more ethical graduates, which suggests that it is not enough. This paper suggests that there is a prior need for an agreed ethical framework, and explicit induction into a professional community of virtue by teachers and practicing mentors.

4.5. Narratives and case studies

The suggestions, in section 4.4 above, are for ethical applications in practical situations which should either raise feelings of injustice, or concern not to repeat others’ mistakes. Achieving this requires some art. Carr makes the argument “that the moral significance of the aesthetic dimension of works of art lies in its direct engagement with the affective or emotional aspects of moral development” (Reference Carr2013: 80). This is in contrast with the dominant “cognitivist” view that “moral understanding is a function of individual development … of gradually more rationally principled responses to hypothetical moral problems and dilemmas”. Such a view leaves no room for “feeling, emotion and imagination” (Carr, Reference Carr2013: 88). In Carr, he puts it

human understanding of moral agency, of the moral visions that inspire such agency and of the moral or other characters that are formed under the influence of such visions are quite irreducible to such deterministic explanation. Rather, such visions are hardly expressible other than in terms of the great cultural, religious and imaginative narratives by which human agents have ever sought to explore the possibilities of human flourishing and the forms of human character that either do or do not conduce to flourishing (Reference Carr2015: 29).

The actuarial profession could not think of situating the actuarial vision in any of the great cultural or religious narratives that might have energised the past. One vision that might attract is suggested by Wyma in his vision of investment advisors participating in the “Great Game”: “a game with stakes so high that the world’s economies depend on it” (Reference Wyma2015: 239). His vision may be widely shared, incorporating a faith in the efficacy of competition to work the invisible hand, which means it is something of an alternative religious narrative. That faith however is necessarily self-defeating: competitive markets only work efficiently when participants believe that they are not working (Grossman & Stiglitz, Reference Grossman and Stiglitz1980).

The narrative suggested here, and in greater length in Asher (Reference Asher2015), is of personal professional vocations within a largely collaborative society – dubbed regulatory capitalism by Levi-Faur (Reference Levi-Faur2005). Actuaries play their social (public interest) roles in the regulation and management of institutions that provide appropriate and trustworthy insurance and savings products. In this context, we can include feeling, emotion and imagination in the discussion of appropriate case studies. Some of these will be tragedies of the likes of Enron and the others described in Messing et al. (Reference Messing, Sugarman and Cramer2006). Some, however, should be positive and could include, for instance, the gratitude of widows who receive life insurance payouts, or obituaries of actuaries such as John Prevett, who was successful in obtaining greater compensation for Thalidomide victimsFootnote 13 .

Helpful actuarial cases are given in Ferris (Reference Ferris2006, Reference Ferris2012) and De Jong & Ferris (Reference De Jong and Ferris2006). Case studies, or “war stories” as they were repeatedly called in the discussion of Stott (Reference Stott2006), can be difficult to share for reasons of confidentiality. One possibility is to create more space for anonymous reporting, perhaps along the lines of the “agony aunt” columns that have had some success in the professional journals, and of career reflections from retiring actuaries, where cases from a long career can be conflated and disguised to protect confidences. Another possibility is for the professional journals to explicitly welcome more case studies.

Roca (Reference Roca2008) expands on the arguments of this section, and makes some useful suggestions as to how use business school case studies to involve students in making ethical judgements.

4.6. Assessments and rubrics

If a framework of ethics is taught, it will need to be assessed in some way. The theory of the “constructive alignment” of teaching and assessments is currently dominant in educational theory. Students do need clarity about what is expected, and should be taught what is to be assessed. Gijbels et al. (Reference Gijbels, Coertjens, Vanthournout, Struyf and Van Petegem2009), however, find that constructivist learning approaches have mixed results in encouraging deep learning. Gibbs (Reference Gibbs2010: 25) also reports on surveys that students “progressively abandon studying anything that is not assessed as they work their way through 3 years of their degree”. Inadequately challenging outcomes are one possible reason. Another is suggested by Land et al.:

Given the often troublesome nature of threshold concepts it is likely that many learners will need to adopt a recursive approach … they cannot be tackled in a simplistic “learning outcomes” model where sentences like “by the end of the course the learner will be able to…” undermine, and perhaps do not even explicitly recognize the complexities of the transformation a learner undergoes (Reference Land, Cousin, Meyer and Davies2005: 61).

Plummer (Reference Plummer2005) also argues that teaching ethical judgement requires fostering the deep approach to learning that is as interested in context and application as in technicalities. It is intrinsically rather than instrumentally motivated and central to the development of integrity. At university, the extrinsic rewards are marks; for the employee, the salary; for the company, profits. If we let students think that good marks justify a lack of understanding it seems to me that we also let them think that good wages justify shady practices and good profits justify exploitation. Moore (Reference Moore2005: 250) also agrees that the recovery of ethics means a focus on the intrinsic rather than instrumental value of work. Students have to see that education consists of more than is assessed, if they are to develop personal integrity and autonomy. They must also not be rewarded for mimicking good judgement by regurgitation of rote learning.

If ethics teaching is to be assessed by written work or oral presentations, these will need assessment rubrics if they are to be fairly evaluated. The rubrics need however to be sufficiently challenging. Ethical judgements obviously fall into the higher levels of the educational taxonomies described in Chan et al. (Reference Chan, Tsui, Chan and Hong2002). These include, for the well-known Bloom’s taxonomy, synthesis and evaluation. For the SOLO taxonomy developed by Biggs & Collis (Reference Biggs and Collis1982), the higher level is an extended abstract classification that places facts into a theoretical framework. Chan et al. (Reference Chan, Tsui, Chan and Hong2002: 513) also describe a third taxonomy that requires the ability for “critical reflection”. Rubrics should aspire to these higher levels. The more penetrating and unseen questions that are typical of the later actuarial examinations are capable of overcoming these obstacles and can be a fair test of ethical judgement.

The rubrics often used to evaluate ethical thinking, however, reflect the dominant Kohlbergian paradigm. An example is the “Ethical Reasoning Value Rubric”Footnote 14 , which is concerned with “core beliefs” and the ability to identify and apply different “ethical perspectives”. As discussed in section 3.5 above, this has little to do with taking an ethical stance. Better are the rubrics suggested by Carlin et al. (Reference Carlin, Rozmus, Spike, Willcockson, Seifert, Chappell, Hsieh, Cole, Flaitz, Engebretson, Lunstroth, Amos and Boutwell2011) for medical students. The column in their rubric that denotes proficiency includes the following criteria with which to measure students’ grasp of the ethical issues when presented with a practical scenario:

-

∙ Fully describes multiple ethical concerns in a complex situation.

-

∙ Fully describes multiple options for addressing the issue.

-

∙ Developed a realistic approach/plan about action in a complex situation. Takes ownership for action/decision.

-

∙ Fully incorporates professional guidelines and applies ethical models or values to consideration of alternative options. In choosing one option, recognises that alternate ethical perspectives may result in differing options and is able to evaluate the merits of these differing options.

There is a question as to whether “multiple ethical concerns” are intended to refer to alternative ways of thinking about ethics, or applying different weights to different concerns. Carlin et al. mention “alternative perspectives”, but are clear that they are not training “bioethicists”, and say that they do not advocate “any one way of thinking about ethics” – theoretically that is. If we follow the arguments of MacIntyre and Carr summarised in section 3.5, then we would say that bioethics was irrelevant, and that while different approaches to ethics are valid, there are no alternatives when it comes to placing value on integrity and the cardinal virtues. The question may allow for different interpretations of justice, but justice is the main principle when making decisions that affect other people. Debates about justice are highly unlikely to be illuminated by discussion of whether different parties are utilitarian, deontologists or virtue ethicists. On the other hand, productive debates can be conducted in negotiating the importance placed on values such as personal freedom and on economic equality when they conflict. Relevant in such debates would be personal interests and political affiliations.

The cases presented to actuarial students are more likely to have multiple stakeholders, and identification of key stakeholders should probably figure in rubrics, as suggested by Baker et al. (Reference Baker, Ni and Van Wart2012).

4.7. Assessing the educational system

Baker et al. also sought to assess whether their teaching of ethics made any difference to their students’ answer to the question: “I would lie and cheat for a million dollars, but I would not break the law even if I was unlikely to be caught”. It disappointingly did not, but it would be desirable to have some type of assessment of the effects of teaching ethics. There is evidence that the structure and content of education can influence students’ moral reasoning, although it is not always positive. McNeel (Reference McNeel1994: 32) reports that some US Bible colleges have a detrimental effect on their students, while the impact of business and education majors can also be negative. Frank et al. (Reference Frank, Gilovich and Regan1993) summarised research that found that the study of economics made students more selfish, but Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2008) found no tendency to selfishness in his sample of Swedish economic students. He did however report that their experience at university does not develop a willingness to collaborate, which is fostered in the police academy. Plummer (Reference Plummer2005) also reports on surveys that find that accountants’ education fails to advance ethical judgements in a way that other courses do.