1 Introduction

Tensile fracture driven by internal pressurisation of viscous fluid takes place in the transport of magma in the lithosphere (Spence & Turcotte Reference Spence and Turcotte1985; Lister & Kerr Reference Lister and Kerr1991; Rubin Reference Rubin1993), tensile jointing of overpressured saturated rock formation (Secor Reference Secor1965; Engelder & Lacazette Reference Engelder, Lacazette, Barton and Stephansson1990) and hydraulic fracturing, a widely used method for the development of oil or gas reservoirs. Modelling of these fractures remains a challenge, owing to the strong, nonlinear coupling of the governing physical processes, associated with breakage of the rock, viscous fluid flow in the fracture and the fluid exchange between the fracture and permeable formation, often manifested at distances from the moving fracture tip too small to be efficiently resolved in conventional numerical models (e.g. Detournay (Reference Detournay2016) and references therein). To overcome this deficiency, one approach has been to devise an accurate near-fracture-tip model for the small-scale processes (Lister Reference Lister1990; Desroches et al. Reference Desroches, Detournay, Lenoach, Papanastasiou, Pearson, Thiercelin and Cheng1994; Garagash & Detournay Reference Garagash and Detournay2000; Garagash, Detournay & Adachi Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011), which can then be bridged with the macroscopic process of hydraulic fracture propagation by incorporating it as a near-tip module of an appropriate numerical framework (Siebrits & Peirce Reference Siebrits and Peirce2002; Peirce & Detournay Reference Peirce and Detournay2008; Dontsov & Peirce Reference Dontsov and Peirce2017; Zia & Lecampion Reference Zia and Lecampion2018). On both the macro- and micro-scales, the complexity of the fluid flow inside the fracture increases along a number of orthogonal axes (rheology of the carrier fluid, impact of carried proppant particles, bridging of particles, the effect of fracture surface roughness, individual settling or particles and gravitational convection, and interplay between the fluid flow inside the open fracture and outside in the permeable ambient medium) (Osiptsov Reference Osiptsov2017). In this work we will focus on the classic formulation: Newtonian incompressible fluid, no particles and smooth fracture walls, fracturing and pore fluids have the same properties.

The models of the near-tip region have proliferated since the early contributions focusing on elastohydrodynamic coupling in a fully fluid-filled fracture (Lister Reference Lister1990; Desroches et al. Reference Desroches, Detournay, Lenoach, Papanastasiou, Pearson, Thiercelin and Cheng1994) to include the effects of the fluid lag and rock fracture toughness (Spence & Sharp Reference Spence and Sharp1985; Rubin Reference Rubin1993; Garagash & Detournay Reference Garagash and Detournay2000), fracturing fluid leak-off into permeable rock (Lenoach Reference Lenoach1995; Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011), pore pressure diffusion and poroelasticity (Detournay & Garagash Reference Detournay and Garagash2003; Kovalyshen Reference Kovalyshen2010), non-laminar flow in the fracture (Dontsov Reference Dontsov2016a; Lecampion & Zia Reference Lecampion and Zia2019), viscous fluid drag onto the fracture walls (Wrobel, Mishuris & Piccolroaz Reference Wrobel, Mishuris and Piccolroaz2017), and non-Newtonian fracturing fluid rheology (Dontsov & Kresse Reference Dontsov and Kresse2018; Moukhtari & Lecampion Reference Moukhtari and Lecampion2018), among others.

In this paper we revisit the nature of the fluid exchange between the fracture and the host permeable rock, and its coupling to the fluid flow in the fracture and to the fracture propagation. As the fluid exchange (usually viewed as the leak-off of the pressurised fracturing fluid into the rock) influences the propagating fracture (fluid-filled) volume and the level of fluid pressurisation in the fracture, it exerts a first-order influence on the fracture opening and propagation. Fluid exchange between the pressurised fracture and the rock can be complicated by a priori unknown time-and-space varying fluid pressure in the fracture and that of the resulting process of the pore pressure diffusion in the permeable rock, time-dependent poroelastic effects, and the ‘cake-building’ (deposition of fracturing fluid solids at the fracture walls and in the pore space of the wall-rock). As a result, many modelling attempts resorted to the use of a phenomenological Carter’s model (Carter Reference Carter, Howard and Fast1957), which suggests that the local rate of fluid exchange (leak-off) at the fracture wall can be approximated by the inverse of the square root of the exposure time (the time since the fracture front has arrived at the considered location along the fracture path). The underpinnings of the Carter’s relation is the assumption of the invariant (constant in space and time) fluid pressure differential between the fracture wall and the far-field ambient pore pressure in the rock,  $p_{f}-p_{o}\approx \text{const}$. The latter assumption often justified on the grounds that the fluid pressure in the fracture scales with the far-field confining stress

$p_{f}-p_{o}\approx \text{const}$. The latter assumption often justified on the grounds that the fluid pressure in the fracture scales with the far-field confining stress  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$ (in order for the fracture to stay open),

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$ (in order for the fracture to stay open),  $p_{f}\approx \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$, while the latter assumed to be distinctly larger than the pore fluid pressure, i.e.

$p_{f}\approx \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$, while the latter assumed to be distinctly larger than the pore fluid pressure, i.e.  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}>p_{o}$, leading to approximately constant pressure differential between the fracture and the rock,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}>p_{o}$, leading to approximately constant pressure differential between the fracture and the rock,  $p_{f}-p_{o}\approx \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}-p_{o}$. This reasoning may be justifiable on average along the fracture length, but it does not stand the scrutiny locally when we consider a drop in fluid pressure in the flow towards the fracture tip. Indeed, near-tip solutions for a fully fracturing-fluid-filled hydraulic fracture in impermeable rock (Desroches et al. Reference Desroches, Detournay, Lenoach, Papanastasiou, Pearson, Thiercelin and Cheng1994) and permeable rock with Carter’s leak-off (Lenoach Reference Lenoach1995; Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011) lead to infinite fluid suction at the tip, which not only invalidates the Carter’s leak-off assumptions in the vicinity of the fracture tip, but actually calls for the separation (lagging) of the fracturing fluid behind the fracture front (Rubin Reference Rubin1993; Garagash & Detournay Reference Garagash and Detournay2000) and pore fluid leak-in (not fracturing fluid leak-off) into the vacant volume of the (fracturing) fluid lag (Detournay & Garagash Reference Detournay and Garagash2003). A number of recent numerical studies of hydraulic fracture propagation in permeable rock which account for the pore pressure diffusion, e.g. (Sarris & Papanastasiou Reference Sarris and Papanastasiou2011; Carrier & Granet Reference Carrier and Granet2012; Golovin & Baykin Reference Golovin and Baykin2018), do not show pore fluid leak-in, as a possible consequence of the spatially under-resolved fracture tip region in these simulations.

$p_{f}-p_{o}\approx \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}-p_{o}$. This reasoning may be justifiable on average along the fracture length, but it does not stand the scrutiny locally when we consider a drop in fluid pressure in the flow towards the fracture tip. Indeed, near-tip solutions for a fully fracturing-fluid-filled hydraulic fracture in impermeable rock (Desroches et al. Reference Desroches, Detournay, Lenoach, Papanastasiou, Pearson, Thiercelin and Cheng1994) and permeable rock with Carter’s leak-off (Lenoach Reference Lenoach1995; Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011) lead to infinite fluid suction at the tip, which not only invalidates the Carter’s leak-off assumptions in the vicinity of the fracture tip, but actually calls for the separation (lagging) of the fracturing fluid behind the fracture front (Rubin Reference Rubin1993; Garagash & Detournay Reference Garagash and Detournay2000) and pore fluid leak-in (not fracturing fluid leak-off) into the vacant volume of the (fracturing) fluid lag (Detournay & Garagash Reference Detournay and Garagash2003). A number of recent numerical studies of hydraulic fracture propagation in permeable rock which account for the pore pressure diffusion, e.g. (Sarris & Papanastasiou Reference Sarris and Papanastasiou2011; Carrier & Granet Reference Carrier and Granet2012; Golovin & Baykin Reference Golovin and Baykin2018), do not show pore fluid leak-in, as a possible consequence of the spatially under-resolved fracture tip region in these simulations.

This paper deals with the near-tip region of a fluid-driven fracture propagating in a permeable reservoir rock, while allowing for the pressure-dependent fluid leak-off and leak-in and associated pore pressure diffusion in the host rock. In formulating the problem, we build on the original model framework of Detournay & Garagash (Reference Detournay and Garagash2003), further generalised by Kovalyshen (Reference Kovalyshen2010), Kovalyshen & Detournay (Reference Kovalyshen and Detournay2013). Specifically, we consider the stationary plane-strain problem of a semi-infinite fracture moving at constant speed under the following simplifying assumptions: (i) the fracture propagates under the condition of small scale yielding (or linear elastic fracture mechanics) (Rice Reference Rice and Liebowitz1968); (ii) the incompressible viscous fracturing fluid is Newtonian, and its flow in the fracture is described by Poiseuille lubrication theory (Batchelor Reference Batchelor1967); (iii) the fluid exchange between the fracture and the host rock (leak-off and leak-in processes) is governed by a one-dimensional pore pressure diffusion; (iv) possible properties’ contrast between the pore and the fracturing fluids is neglected; and (v) the poroelastic ‘back stress’ effects are considered negligible (Kovalyshen Reference Kovalyshen2010).

This paper is organised as follows. First, the problem formulation, underlining assumptions and the resulting governing equations are presented. We follow with the discussion of the various asymptotic limits of the solution, including the reduction to the Carter’s leak-off case (Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011), which then allows us to frame the general structure of the sought solution and its parametric dependence. Next, we introduce the characteristic scalings of the solution as they pertain to corresponding limiting regimes of the fracture propagation, and the general non-dimensional problem parametric space defined in terms of two numbers, non-dimensional leak-off  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}$ and leak-in

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}$ and leak-in  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$. The rest of the paper is devoted to the analytical and numerical exploration of the solution to the problem in the parametric space, including an analysis of the relative importance of the pressure-dependent effects in the fluid exchange process between the fracture and the reservoir.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$. The rest of the paper is devoted to the analytical and numerical exploration of the solution to the problem in the parametric space, including an analysis of the relative importance of the pressure-dependent effects in the fluid exchange process between the fracture and the reservoir.

2 Model formulation

2.1 Problem definition

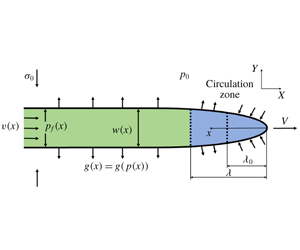

To examine the near-tip behaviour of a fluid-driven fracture, we consider the problem of a semi-infinite fracture (figure 1) propagating with constant velocity  $V$, which is understood as the instantaneous local tip velocity of the parent hydraulic fracture (HF). The host permeable linear-elastic rock is characterised by Young’s modulus

$V$, which is understood as the instantaneous local tip velocity of the parent hydraulic fracture (HF). The host permeable linear-elastic rock is characterised by Young’s modulus  $E$ and Poisson’s ratio

$E$ and Poisson’s ratio  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}$. Small-scale yielding (Rice Reference Rice and Liebowitz1968), i.e. it is assumed that the rock damage/yielding zone at the advancing fracture front is small compared to the length scales of other physical processes active near the tip (e.g. dissipation in the viscous fluid flow). Linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM) theory is therefore utilised for the modelling of the quasi-static propagation of the fracture in the rock characterised by the fracture toughness

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}$. Small-scale yielding (Rice Reference Rice and Liebowitz1968), i.e. it is assumed that the rock damage/yielding zone at the advancing fracture front is small compared to the length scales of other physical processes active near the tip (e.g. dissipation in the viscous fluid flow). Linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM) theory is therefore utilised for the modelling of the quasi-static propagation of the fracture in the rock characterised by the fracture toughness  $K_{Ic}$.

$K_{Ic}$.

In figure 1 we show the schematics of the considered problem. The fracture, loaded internally by the fluid pressure  $p_{f}(x)$, opens (with aperture distribution

$p_{f}(x)$, opens (with aperture distribution  $w(x)$) against the in situ confining stress

$w(x)$) against the in situ confining stress  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$. We consider fluids presented in the model as Newtonian. Fluid flow in the fracture is described by lubrication theory (Batchelor Reference Batchelor1967).

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$. We consider fluids presented in the model as Newtonian. Fluid flow in the fracture is described by lubrication theory (Batchelor Reference Batchelor1967).

Figure 1. Schematic picture of the fracture tip model with the pressure-dependent fluid exchange between the fracture and permeable saturated rock.

The rock adjacent to the fracture is permeable and saturated by pore fluid at ambient pore pressure  $p_{o}$. The fluid exchange between the fracture and the reservoir is driven by the pressure difference between the fracture (

$p_{o}$. The fluid exchange between the fracture and the reservoir is driven by the pressure difference between the fracture ( $p_{f}$) and the reservoir (

$p_{f}$) and the reservoir ( $p_{o}$). The fluid exchange process is modelled by one-dimensional pressure-dependent leak-off/leak-in (PDL) driven by pore pressure diffusion in the rock (Detournay & Garagash Reference Detournay and Garagash2003; Kovalyshen Reference Kovalyshen2010; Kovalyshen & Detournay Reference Kovalyshen and Detournay2013). This model is a convenient approximation of a full two-dimensional leak-off and associated diffusion problem (Detournay & Garagash Reference Detournay and Garagash2003) based on the assumption that the characteristic thickness of the diffusive boundary layer around the crack is small compared to the characteristic length scale of the fracture tip problem. The local rate of the fluid exchange is denoted by

$p_{o}$). The fluid exchange process is modelled by one-dimensional pressure-dependent leak-off/leak-in (PDL) driven by pore pressure diffusion in the rock (Detournay & Garagash Reference Detournay and Garagash2003; Kovalyshen Reference Kovalyshen2010; Kovalyshen & Detournay Reference Kovalyshen and Detournay2013). This model is a convenient approximation of a full two-dimensional leak-off and associated diffusion problem (Detournay & Garagash Reference Detournay and Garagash2003) based on the assumption that the characteristic thickness of the diffusive boundary layer around the crack is small compared to the characteristic length scale of the fracture tip problem. The local rate of the fluid exchange is denoted by  $g(x)$. We also assume that the pore and hydraulic fracturing fluids have similar (identical in the model) properties.

$g(x)$. We also assume that the pore and hydraulic fracturing fluids have similar (identical in the model) properties.

Fluid pressure  $p_{f}(x)$ diminishes in the fluid flow along the fracture towards the tip. If its value at the tip,

$p_{f}(x)$ diminishes in the fluid flow along the fracture towards the tip. If its value at the tip,  $p_{f}(0)$, drops below

$p_{f}(0)$, drops below  $p_{o}$, there exists a near-tip zone of some length

$p_{o}$, there exists a near-tip zone of some length  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}_{o}$ (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}_{o}$ ( $x\in [0,\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}_{o}]$) along which the pore fluid flows into the fracture from the surrounding rock. For distances larger than

$x\in [0,\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}_{o}]$) along which the pore fluid flows into the fracture from the surrounding rock. For distances larger than  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}_{o}$, the fluid pressure recovers enough to enable the leak-off of the formation fluid from the fracture back into the rock. Owing to the steady crack propagation (i.e. problem is stationary in the coordinate system

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}_{o}$, the fluid pressure recovers enough to enable the leak-off of the formation fluid from the fracture back into the rock. Owing to the steady crack propagation (i.e. problem is stationary in the coordinate system  $x$ moving with the crack tip), all of the formation fluid leaked-in along

$x$ moving with the crack tip), all of the formation fluid leaked-in along  $x\in [0,\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}_{o}]$ has to circulate (leak-off) back into the formation, thus defining the pore-fluid circulation zone of some length

$x\in [0,\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}_{o}]$ has to circulate (leak-off) back into the formation, thus defining the pore-fluid circulation zone of some length  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}>\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}_{o}$ near the fracture tip (figure 1). The crack channel within the interval

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}>\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}_{o}$ near the fracture tip (figure 1). The crack channel within the interval  $[\unicode[STIX]{x1D706},+\infty )$ is filled by the hydraulic fracturing fluid which, due to pressure continuity, is also expected to leak-off into the rock.

$[\unicode[STIX]{x1D706},+\infty )$ is filled by the hydraulic fracturing fluid which, due to pressure continuity, is also expected to leak-off into the rock.

2.2 Governing equations

Let us consider the moving coordinate system ( $x,y$) related to the fixed coordinate system (

$x,y$) related to the fixed coordinate system ( $X,Y$) by equations:

$X,Y$) by equations:  $x=Vt-X$ and

$x=Vt-X$ and  $y=Y$. The considered problem is stationary in the moving coordinate system. The governing equations are written for unknown fracture opening

$y=Y$. The considered problem is stationary in the moving coordinate system. The governing equations are written for unknown fracture opening  $w(x)$ and net pressure distribution

$w(x)$ and net pressure distribution  $p(x)=p_{f}(x)-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$ along the fracture (

$p(x)=p_{f}(x)-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$ along the fracture ( $0<x<+\infty$), elaborating further on the framework proposed by Garagash et al. (Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011).

$0<x<+\infty$), elaborating further on the framework proposed by Garagash et al. (Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011).

2.2.1 Fracture propagation

Linear elastic fracture mechanics fracture propagation criteria under quasi-static conditions states that the stress intensity factor at the crack tip matches the rock toughness:  $K_{I}=K_{Ic}$. This condition prescribes the asymptotic behaviour of the fracture opening near its front (Irwin Reference Irwin1957):

$K_{I}=K_{Ic}$. This condition prescribes the asymptotic behaviour of the fracture opening near its front (Irwin Reference Irwin1957):

$$\begin{eqnarray}w(x)=\frac{K^{\prime }}{E^{\prime }}\sqrt{x}.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}w(x)=\frac{K^{\prime }}{E^{\prime }}\sqrt{x}.\end{eqnarray}$$ Here  $E^{\prime }=E/(1-\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}^{2})$ is the plane strain modulus and

$E^{\prime }=E/(1-\unicode[STIX]{x1D708}^{2})$ is the plane strain modulus and  $K^{\prime }=4\sqrt{(2/\unicode[STIX]{x03C0})}K_{Ic}$ is the toughness parameter.

$K^{\prime }=4\sqrt{(2/\unicode[STIX]{x03C0})}K_{Ic}$ is the toughness parameter.

2.2.2 Crack elasticity

The net pressure  $p(x)$ in the fracture can be expressed as the crack line integral of the opening

$p(x)$ in the fracture can be expressed as the crack line integral of the opening  $w(x)$ using the elasticity equation (Bilby & Eshelby Reference Bilby, Eshelby and Liebowitz1968)

$w(x)$ using the elasticity equation (Bilby & Eshelby Reference Bilby, Eshelby and Liebowitz1968)

$$\begin{eqnarray}p(x)=\frac{E^{\prime }}{4\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}}\int _{0}^{\infty }\frac{\text{d}w(s)}{\text{d}s}\frac{\text{d}s}{x-s}.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}p(x)=\frac{E^{\prime }}{4\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}}\int _{0}^{\infty }\frac{\text{d}w(s)}{\text{d}s}\frac{\text{d}s}{x-s}.\end{eqnarray}$$Equation (2.2) can be inverted (Garagash & Detournay Reference Garagash and Detournay2000) to aid in the numerical implementation of the problem solution, i.e.

$$\begin{eqnarray}w(x)=\frac{K^{\prime }}{E^{\prime }}\sqrt{x}+\frac{4}{\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}E^{\prime }}\int _{0}^{\infty }K(x,s)p(s)\,\text{d}s,\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}w(x)=\frac{K^{\prime }}{E^{\prime }}\sqrt{x}+\frac{4}{\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}E^{\prime }}\int _{0}^{\infty }K(x,s)p(s)\,\text{d}s,\end{eqnarray}$$ where the integral kernel is  $K(x,s)=\ln |(\sqrt{x}+\sqrt{s})/(\sqrt{x}-\sqrt{s})|-2\sqrt{x/s}$. This form of crack elasticity equation already accounts for the propagation condition (2.1) (i.e. the integral in (2.3) is

$K(x,s)=\ln |(\sqrt{x}+\sqrt{s})/(\sqrt{x}-\sqrt{s})|-2\sqrt{x/s}$. This form of crack elasticity equation already accounts for the propagation condition (2.1) (i.e. the integral in (2.3) is  $o(\sqrt{x})$).

$o(\sqrt{x})$).

2.2.3 Fluid flow

The flow of a viscous incompressible fluid in the crack channel is described by the continuity equation averaged across the fracture aperture, which, upon transforming to the moving coordinate system, is given by

$$\begin{eqnarray}V\frac{\text{d}w}{\text{d}x}-\frac{\text{d}(wv)}{\text{d}x}+g=0,\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}V\frac{\text{d}w}{\text{d}x}-\frac{\text{d}(wv)}{\text{d}x}+g=0,\end{eqnarray}$$ where  $g$ is the local rate of fluid exchange between the fracture and the rock (

$g$ is the local rate of fluid exchange between the fracture and the rock ( $g>0$ for leak-off and

$g>0$ for leak-off and  $g<0$ for leak-in) given in the PDL model by the following expression (appendix A):

$g<0$ for leak-in) given in the PDL model by the following expression (appendix A):

$$\begin{eqnarray}g(x)=Q^{\prime }\sqrt{V}\left(\frac{p(0)+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }}{2\sqrt{x}}+\int _{0}^{x}\frac{\text{d}p}{\text{d}x^{\prime }}\frac{\text{d}x^{\prime }}{2\sqrt{x-x^{\prime }}}\right).\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}g(x)=Q^{\prime }\sqrt{V}\left(\frac{p(0)+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }}{2\sqrt{x}}+\int _{0}^{x}\frac{\text{d}p}{\text{d}x^{\prime }}\frac{\text{d}x^{\prime }}{2\sqrt{x-x^{\prime }}}\right).\end{eqnarray}$$ Here  $Q^{\prime }=4k/(\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}\sqrt{\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}c})$ is a leak-in coefficient defined in terms of the pore pressure diffusivity coefficient

$Q^{\prime }=4k/(\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}\sqrt{\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}c})$ is a leak-in coefficient defined in terms of the pore pressure diffusivity coefficient  $c$, reservoir permeability

$c$, reservoir permeability  $k$ and fluid viscosity

$k$ and fluid viscosity  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}$,  $p(0)=p_{f}(0)-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$ is the net fluid pressure value at the fracture front, and

$p(0)=p_{f}(0)-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$ is the net fluid pressure value at the fracture front, and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}-p_{o}$ is the ambient value of the effective confining stress.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}-p_{o}$ is the ambient value of the effective confining stress.

Integrating (2.4) from the tip  $x=0$ to some distance

$x=0$ to some distance  $x>0$, we obtain

$x>0$, we obtain

$$\begin{eqnarray}wv=wV+q_{\bot },\quad q_{\bot }=\int _{0}^{x}g(s)\,\text{d}s,\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}wv=wV+q_{\bot },\quad q_{\bot }=\int _{0}^{x}g(s)\,\text{d}s,\end{eqnarray}$$ which signifies that the local fluid volumetric flow rate at distance  $x$ from the fracture tip

$x$ from the fracture tip  $w(x)v(x)$ is partitioned between the fluid stored in the fracture

$w(x)v(x)$ is partitioned between the fluid stored in the fracture  $w(x)V$ and in the rock via the cumulative rate of fluid exchange

$w(x)V$ and in the rock via the cumulative rate of fluid exchange  $q_{\bot }(x)$, given by

$q_{\bot }(x)$, given by

$$\begin{eqnarray}q_{\bot }(x)=Q^{\prime }\sqrt{V}\int _{0}^{x}\frac{p(s)+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }}{2\sqrt{x-s}}\,\text{d}s=C^{\prime }\sqrt{Vx}+Q^{\prime }\sqrt{V}\int _{0}^{x}\frac{p(s)}{2\sqrt{x-s}}\,\text{d}s.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}q_{\bot }(x)=Q^{\prime }\sqrt{V}\int _{0}^{x}\frac{p(s)+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }}{2\sqrt{x-s}}\,\text{d}s=C^{\prime }\sqrt{Vx}+Q^{\prime }\sqrt{V}\int _{0}^{x}\frac{p(s)}{2\sqrt{x-s}}\,\text{d}s.\end{eqnarray}$$ Here  $C^{\prime }=Q^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }=4k\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }/(\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}\sqrt{\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}c})$ is the Carter’s leak-off coefficient. The first term on the right-hand side of (2.7) corresponds to the classical Carter’s leak-off expression strictly valid only when

$C^{\prime }=Q^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }=4k\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }/(\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}\sqrt{\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}c})$ is the Carter’s leak-off coefficient. The first term on the right-hand side of (2.7) corresponds to the classical Carter’s leak-off expression strictly valid only when  $p_{f}(x)=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$ (or

$p_{f}(x)=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$ (or  $p(x)=0$), while the second term is the pressure-dependent correction. Since the net fluid pressure

$p(x)=0$), while the second term is the pressure-dependent correction. Since the net fluid pressure  $p(x)<0$ (or

$p(x)<0$ (or  $p_{f}(x)<\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$) in a semi-infinite hydraulic fracture (e.g. Garagash & Detournay Reference Garagash and Detournay2000), the corrective pressure-dependent term is always negative or, in other words, corresponds to a corrective leak-in.

$p_{f}(x)<\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}$) in a semi-infinite hydraulic fracture (e.g. Garagash & Detournay Reference Garagash and Detournay2000), the corrective pressure-dependent term is always negative or, in other words, corresponds to a corrective leak-in.

Finally, Poiseuille’s law for the fluid velocity along the crack channel

$$\begin{eqnarray}v=\frac{w^{2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }}\frac{\text{d}p}{\text{d}x},\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}v=\frac{w^{2}}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }}\frac{\text{d}p}{\text{d}x},\end{eqnarray}$$ with  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }=12\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}$ designating the viscosity parameter, completes the fluid flow description.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }=12\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}$ designating the viscosity parameter, completes the fluid flow description.

3 Asymptotes and structure of the general solution

3.1 Vertex solutions

Two different mechanisms govern the propagation regime of a finite hydraulic fracture (e.g. Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011). The first one is the partitioning of the injected fluid between the fracture and the reservoir as a result of the leak-in and leak-off processes (fracture storage versus fluid exchange with the rock). The second mechanism is the partitioning of the total dissipated energy between the creation of the new fracture surfaces and flow of the viscous fluid along the fracture (toughness versus viscosity).

In the process of fracture growth, the partition of the fracturing fluid and the partition of the dissipated energy change over time, which can lead to the realisation of different limiting regimes dominated by one storage mechanism and one dissipation mechanism at different times. In the context of a semi-infinite hydraulic fracture, the change in the partitioning of the fluid and energy with time can be recast into the change with the distance from the fracture tip.

One can suggest four limiting propagation regimes that are characterised by the dominance of one storage/exchange mechanism and one dissipation mechanism: toughness dominated  $(\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }=0)$, storage-viscosity dominated

$(\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }=0)$, storage-viscosity dominated  $(C^{\prime }=Q^{\prime }=0,K^{\prime }=0)$, leak-off-viscosity dominated

$(C^{\prime }=Q^{\prime }=0,K^{\prime }=0)$, leak-off-viscosity dominated  $(C^{\prime }\rightarrow \infty ,K^{\prime }=0)$ and storage-leak-in-viscosity dominated

$(C^{\prime }\rightarrow \infty ,K^{\prime }=0)$ and storage-leak-in-viscosity dominated  $(K^{\prime }=0,C^{\prime }>0,Q^{\prime }<+\infty )$. The corresponding solutions are referred to as ‘vertex’ solutions in a problem parametric space.

$(K^{\prime }=0,C^{\prime }>0,Q^{\prime }<+\infty )$. The corresponding solutions are referred to as ‘vertex’ solutions in a problem parametric space.

While the leak-in ( $Q^{\prime }$) and the leak-off (

$Q^{\prime }$) and the leak-off ( $C^{\prime }$) coefficients define the partitioning of the fluid, viscosity

$C^{\prime }$) coefficients define the partitioning of the fluid, viscosity  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }$ and toughness

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }$ and toughness  $K^{\prime }$ parameters are responsible for the partitioning of the dissipated energy.

$K^{\prime }$ parameters are responsible for the partitioning of the dissipated energy.

The first three vertex solutions ( $k$,

$k$,  $m$,

$m$,  $\widetilde{m}$) are given, e.g. by Garagash et al. (Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011), and summarised in table 1 for completeness, in terms of the following three characteristic length scales:

$\widetilde{m}$) are given, e.g. by Garagash et al. (Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011), and summarised in table 1 for completeness, in terms of the following three characteristic length scales:

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle \ell _{k}=\left(\frac{K^{\prime }}{E^{\prime }}\right)^{2},\quad \ell _{m}=V\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }}{E^{\prime }},\quad \ell _{\widetilde{m}}=\left(C^{\prime }\sqrt{V}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }}{E^{\prime }}\right)^{2/3}. & & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle \ell _{k}=\left(\frac{K^{\prime }}{E^{\prime }}\right)^{2},\quad \ell _{m}=V\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }}{E^{\prime }},\quad \ell _{\widetilde{m}}=\left(C^{\prime }\sqrt{V}\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }}{E^{\prime }}\right)^{2/3}. & & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$Table 1. Three limiting solutions of a semi-infinite hydraulic fracture for the identified limiting values of problem parameters.

The pressure dependency of the fluid exchange between the fracture and the rock is coupled with the fluid pressure drop in the flow toward the crack tip (when viscosity is non-negligible:  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }>0$). This fact suggests that the leak-in dominates near the fracture front. In other words, we anticipate that in the vicinity of the fracture tip the newly created crack volume (storage) is accommodated entirely by the pore fluid leaking-in from the rock (while the fluid flow towards the fracture tip along the crack channel is negligible there,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }>0$). This fact suggests that the leak-in dominates near the fracture front. In other words, we anticipate that in the vicinity of the fracture tip the newly created crack volume (storage) is accommodated entirely by the pore fluid leaking-in from the rock (while the fluid flow towards the fracture tip along the crack channel is negligible there,  $v\approx 0$). However, this dominance of the leak-in has to be limited to a finite near-tip region, since crack elasticity requires that

$v\approx 0$). However, this dominance of the leak-in has to be limited to a finite near-tip region, since crack elasticity requires that  $p(x)$ vanishes as

$p(x)$ vanishes as  $x\rightarrow \infty$, or

$x\rightarrow \infty$, or  $p_{f}(x)\rightarrow \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}>p_{o}$, thus, eventually giving a way to the leak-off process.

$p_{f}(x)\rightarrow \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}>p_{o}$, thus, eventually giving a way to the leak-off process.

Vertices  $k$,

$k$,  $m$,

$m$,  $\widetilde{m}$ (table 1) are the solutions for the entire semi-infinite fracture for the corresponding limiting values of governing parameters. They can be determined from the monomial solution to the crack elasticity equation (2.2):

$\widetilde{m}$ (table 1) are the solutions for the entire semi-infinite fracture for the corresponding limiting values of governing parameters. They can be determined from the monomial solution to the crack elasticity equation (2.2):

$$\begin{eqnarray}w_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}}(x)=Bx^{\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}};\quad p_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}}(x)=E^{\prime }Bf(\unicode[STIX]{x1D706})x^{\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}-1},\quad f(\unicode[STIX]{x1D706})=\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}\cot (\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}\unicode[STIX]{x1D706})}{4},\quad 0<\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}<1.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}w_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}}(x)=Bx^{\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}};\quad p_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}}(x)=E^{\prime }Bf(\unicode[STIX]{x1D706})x^{\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}-1},\quad f(\unicode[STIX]{x1D706})=\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}\cot (\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}\unicode[STIX]{x1D706})}{4},\quad 0<\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}<1.\end{eqnarray}$$ Here particular values of the prefactor  $B$ and the exponent

$B$ and the exponent  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}$ are constrained by the lubrication equation when setting parameters (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D706}$ are constrained by the lubrication equation when setting parameters ( $C^{\prime }$,

$C^{\prime }$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }$ and  $K^{\prime }$) to the corresponding limiting values, as detailed by Garagash et al. (Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011). In the

$K^{\prime }$) to the corresponding limiting values, as detailed by Garagash et al. (Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011). In the  $k$-vertex, viscosity is negligible (

$k$-vertex, viscosity is negligible ( $\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }=0$) and the solution follows from the propagation condition (2.1). In the

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }=0$) and the solution follows from the propagation condition (2.1). In the  $m$-vertex, the fluid exchange (

$m$-vertex, the fluid exchange ( $C^{\prime }=Q^{\prime }=0$) and toughness (

$C^{\prime }=Q^{\prime }=0$) and toughness ( $K^{\prime }=0$) are negligible, and the solution is recovered by balancing the fluid flux in the crack

$K^{\prime }=0$) are negligible, and the solution is recovered by balancing the fluid flux in the crack  $w(x)v(x)$ with the storage term

$w(x)v(x)$ with the storage term  $w(x)V$ in the continuity equation. We anticipate that in the general parametric case (i.e. not limited to the stated values of

$w(x)V$ in the continuity equation. We anticipate that in the general parametric case (i.e. not limited to the stated values of  $K^{\prime }$ and other parameters) the

$K^{\prime }$ and other parameters) the  $m$-vertex solution provides the far-field solution asymptote (e.g. Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011). In the

$m$-vertex solution provides the far-field solution asymptote (e.g. Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011). In the  $\widetilde{m}$-vertex, the fluid storage (

$\widetilde{m}$-vertex, the fluid storage ( $C^{\prime }\rightarrow \infty$) and toughness (

$C^{\prime }\rightarrow \infty$) and toughness ( $K^{\prime }=0$) are negligible. In this case, the fluid flux in the crack is balanced with the Carter’s leak-off term. In the general case, the

$K^{\prime }=0$) are negligible. In this case, the fluid flux in the crack is balanced with the Carter’s leak-off term. In the general case, the  $\widetilde{m}$-vertex can be realised as an intermediate field solution (Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011).

$\widetilde{m}$-vertex can be realised as an intermediate field solution (Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011).

The new storage-leak-in-viscosity vertex  $\widetilde{o}$ emerges as a particular case of the viscosity-dominated (

$\widetilde{o}$ emerges as a particular case of the viscosity-dominated ( $K^{\prime }=0$) behaviour linked to the dominance of the fluid leak-in (rather than the leak-off) in the near field (

$K^{\prime }=0$) behaviour linked to the dominance of the fluid leak-in (rather than the leak-off) in the near field ( $x\rightarrow 0$). It corresponds to the classical zero-toughness behaviour of the crack opening,

$x\rightarrow 0$). It corresponds to the classical zero-toughness behaviour of the crack opening,  $w=B_{\widetilde{o}}x^{3/2}$, and the non-singular pressure

$w=B_{\widetilde{o}}x^{3/2}$, and the non-singular pressure  $p=-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{0}^{\prime }-\frac{3}{2}B_{\widetilde{o}}(V^{1/2}/Q^{\prime })x$. The first term in the expression for the net pressure is obtained from balancing the leak-in and leak-off terms in the continuity equation. On the other hand, the second term arises from matching the leak-in and the fracture storage terms and gains particular importance in/near the zero-leak-off limit (

$p=-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{0}^{\prime }-\frac{3}{2}B_{\widetilde{o}}(V^{1/2}/Q^{\prime })x$. The first term in the expression for the net pressure is obtained from balancing the leak-in and leak-off terms in the continuity equation. On the other hand, the second term arises from matching the leak-in and the fracture storage terms and gains particular importance in/near the zero-leak-off limit ( $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{0}^{\prime }=0$). This vertex solution contains prefactor

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{0}^{\prime }=0$). This vertex solution contains prefactor  $B_{\widetilde{o}}$ (with units

$B_{\widetilde{o}}$ (with units  $1/\sqrt{m}$) that is unknown and a part of the overall solution. This betrays the fact that the

$1/\sqrt{m}$) that is unknown and a part of the overall solution. This betrays the fact that the  $\widetilde{o}$-asymptote can be realised only as a near or intermediate field of the fracture, as it can not satisfy the elasticity equation over the full semi-infinite crack extent. The second term in the net pressure is found with the assumption that the

$\widetilde{o}$-asymptote can be realised only as a near or intermediate field of the fracture, as it can not satisfy the elasticity equation over the full semi-infinite crack extent. The second term in the net pressure is found with the assumption that the  $\widetilde{o}$-vertex solution is realised in the near field, and in this case, the left-hand side of the continuity equation (

$\widetilde{o}$-vertex solution is realised in the near field, and in this case, the left-hand side of the continuity equation ( ${\sim}w^{3}(x)p^{\prime }(x)$) for this vertex solution is negligible as compared to the terms on the right-hand side (storage, leak-off and leak-in).

${\sim}w^{3}(x)p^{\prime }(x)$) for this vertex solution is negligible as compared to the terms on the right-hand side (storage, leak-off and leak-in).

For non-zero fracture toughness  $K^{\prime }>0$, the near-field (

$K^{\prime }>0$, the near-field ( $x\rightarrow 0$) behaviour of the fracture opening is given by the

$x\rightarrow 0$) behaviour of the fracture opening is given by the  $k$-vertex solution (table 1), as stems from the propagation condition (2.1). The corresponding asymptotic expression for the net pressure

$k$-vertex solution (table 1), as stems from the propagation condition (2.1). The corresponding asymptotic expression for the net pressure  $p(x\rightarrow 0)=-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{0}^{\prime }-(K^{\prime }V^{1/2})/(E^{\prime }Q^{\prime })$ follows from the fluid continuity equation (2.6) by balancing the fluid exchange (the leak-in pore fluid volume) with the fracture storage. (We note that the fluid flux along the crack

$p(x\rightarrow 0)=-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{0}^{\prime }-(K^{\prime }V^{1/2})/(E^{\prime }Q^{\prime })$ follows from the fluid continuity equation (2.6) by balancing the fluid exchange (the leak-in pore fluid volume) with the fracture storage. (We note that the fluid flux along the crack  $wv$ is negligibly small in the near-field fluid balance.) The obtained finite net pressure value at the fracture tip is drastically different from the one in the Carter’s, pressure-independent leak-off model (Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011), where the pressure sustains a negative singularity as the fracturing fluid is assumed to reach the tip of the fracture. When reformulated in terms of the fluid pressure,

$wv$ is negligibly small in the near-field fluid balance.) The obtained finite net pressure value at the fracture tip is drastically different from the one in the Carter’s, pressure-independent leak-off model (Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011), where the pressure sustains a negative singularity as the fracturing fluid is assumed to reach the tip of the fracture. When reformulated in terms of the fluid pressure,  $p_{f}(x\rightarrow 0)=p_{0}-K^{\prime }\sqrt{V}/(E^{\prime }Q^{\prime })$, this asymptote suggests that the fluid pressure at the crack tip is reduced from its drained value given by the ambient pore pressure

$p_{f}(x\rightarrow 0)=p_{0}-K^{\prime }\sqrt{V}/(E^{\prime }Q^{\prime })$, this asymptote suggests that the fluid pressure at the crack tip is reduced from its drained value given by the ambient pore pressure  $p_{0}$ by the amount

$p_{0}$ by the amount  $K^{\prime }\sqrt{V}/(E^{\prime }Q^{\prime })$. The latter, undrained pressure change vanishes for slowly propagating cracks (

$K^{\prime }\sqrt{V}/(E^{\prime }Q^{\prime })$. The latter, undrained pressure change vanishes for slowly propagating cracks ( $V\rightarrow 0$) or/and zero rock toughness (

$V\rightarrow 0$) or/and zero rock toughness ( $K^{\prime }\rightarrow 0$).

$K^{\prime }\rightarrow 0$).

The obtained near-field  $k$ (

$k$ ( $K^{\prime }>0$) and

$K^{\prime }>0$) and  $\widetilde{o}$ (

$\widetilde{o}$ ( $K^{\prime }=0$) asymptotes are summarised in table 2.

$K^{\prime }=0$) asymptotes are summarised in table 2.

Figure 2. Parametric diagram (pyramid  $m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$) and corresponding four limiting faces corresponding to the dominance of one energy dissipation or one fluid storage mechanism. Few solution trajectories parameterised by the leak-off

$m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$) and corresponding four limiting faces corresponding to the dominance of one energy dissipation or one fluid storage mechanism. Few solution trajectories parameterised by the leak-off  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}$ and leak-in

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}$ and leak-in  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$ numbers (or their ratio

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$ numbers (or their ratio  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$) are also shown.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$) are also shown.

Table 2. Near-field ( $x\rightarrow 0$) of semi-infinite hydraulic fracture.

$x\rightarrow 0$) of semi-infinite hydraulic fracture.

3.2 Structure of solution and scaling

The general solution of the considered problem can be tracked within the parametric triangular pyramid  $m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$ formed by the four aforesaid vertices. The schematic diagram of this pyramid is represented in figure 2.

$m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$ formed by the four aforesaid vertices. The schematic diagram of this pyramid is represented in figure 2.

Four triangular faces of pyramid  $m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$ correspond to either the dominance of one of the three fluid storage/exchange mechanisms or one of the dissipation mechanisms:

$m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$ correspond to either the dominance of one of the three fluid storage/exchange mechanisms or one of the dissipation mechanisms:

(i) storage-leak-off face

$m\widetilde{m}k$: leak-in process is negligible,

$m\widetilde{m}k$: leak-in process is negligible,  $Q^{\prime }=0$;

$Q^{\prime }=0$;(ii) storage-leak-in face

$m\widetilde{o}k$: leak-off process is negligible,

$m\widetilde{o}k$: leak-off process is negligible,  $C^{\prime }\propto \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }=0$;

$C^{\prime }\propto \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }=0$;(iii) leak-face

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$: fluid storage in the fracture is negligible,

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$: fluid storage in the fracture is negligible,  $C^{\prime }\rightarrow \infty$; and

$C^{\prime }\rightarrow \infty$; and(iv) viscosity-face

$m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$: toughness is negligible,

$m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$: toughness is negligible,  $K^{\prime }=0$.

$K^{\prime }=0$.

Six edges of the pyramid  $m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$ correspond to the intersection of the corresponding two faces and, thus, reflect the dominance of one of the three fluid storage/exchange mechanisms and one of the dissipation mechanisms. For example,

$m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$ correspond to the intersection of the corresponding two faces and, thus, reflect the dominance of one of the three fluid storage/exchange mechanisms and one of the dissipation mechanisms. For example,  $\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$ is the leak-viscosity edge (

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$ is the leak-viscosity edge ( $C^{\prime }\rightarrow \infty$ and

$C^{\prime }\rightarrow \infty$ and  $K^{\prime }=0$), bounding the leak

$K^{\prime }=0$), bounding the leak  $\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$ (

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$ ( $C^{\prime }\rightarrow \infty$) and the viscosity

$C^{\prime }\rightarrow \infty$) and the viscosity  $m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$ (

$m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$ ( $K^{\prime }=0$) faces, and, thus, corresponds to the negligible storage and toughness.

$K^{\prime }=0$) faces, and, thus, corresponds to the negligible storage and toughness.

The proposed pyramidal parametric space  $m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$ for the fracture tip with the pressure-dependent leak-off is a direct generalisation of the triangular parametric space, face

$m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$ for the fracture tip with the pressure-dependent leak-off is a direct generalisation of the triangular parametric space, face  $m\widetilde{m}k$, for Carter’s (pressure-independent) leak-off (Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011), by the addition of the new vertex

$m\widetilde{m}k$, for Carter’s (pressure-independent) leak-off (Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011), by the addition of the new vertex  $\widetilde{o}$. The emergent edges

$\widetilde{o}$. The emergent edges  $\widetilde{o}k$,

$\widetilde{o}k$,  $\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$ and

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$ and  $m\widetilde{o}$ are expected to describe the transitions of the corresponding limiting solutions with distance from the crack tip between the corresponding vertices (from the second to the first, i.e.

$m\widetilde{o}$ are expected to describe the transitions of the corresponding limiting solutions with distance from the crack tip between the corresponding vertices (from the second to the first, i.e.  $\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$-edge corresponds to the transition from the near field

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$-edge corresponds to the transition from the near field  $\widetilde{o}$ to the far field

$\widetilde{o}$ to the far field  $\widetilde{m}$, etc). As discussed above, the

$\widetilde{m}$, etc). As discussed above, the  $\widetilde{o}$-vertex solution can be realised only in the near field of a semi-infinite fracture, thus suggesting that the

$\widetilde{o}$-vertex solution can be realised only in the near field of a semi-infinite fracture, thus suggesting that the  $\widetilde{o}k$-edge may in fact correspond to the near-field expansion of the

$\widetilde{o}k$-edge may in fact correspond to the near-field expansion of the  $k$-vertex (

$k$-vertex ( $w\propto x^{1/2}$) which includes the next order correction given by the

$w\propto x^{1/2}$) which includes the next order correction given by the  $\widetilde{o}$-vertex solution (

$\widetilde{o}$-vertex solution ( $w\propto x^{3/2}$), and this correction may come to eventually dominate (over the

$w\propto x^{3/2}$), and this correction may come to eventually dominate (over the  $k$-term) with increasing distance from the tip.

$k$-term) with increasing distance from the tip.

In the case of the other two edges involving the  $\widetilde{o}$-vertex as the fracture near field, i.e.

$\widetilde{o}$-vertex as the fracture near field, i.e.  $\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$ (

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$ ( $K^{\prime }=0$,

$K^{\prime }=0$,  $C^{\prime }\rightarrow \infty$) and

$C^{\prime }\rightarrow \infty$) and  $m\widetilde{o}$ (

$m\widetilde{o}$ ( $K^{\prime }=0$,

$K^{\prime }=0$,  $C^{\prime }\propto \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }=0$), they should in principle provide solutions for the entire semi-infinite HF under the corresponding limiting values of the parameters. Before attempting these (and other edge) solutions, let us attempt to constrain the a priori unknown near-field coefficient

$C^{\prime }\propto \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }=0$), they should in principle provide solutions for the entire semi-infinite HF under the corresponding limiting values of the parameters. Before attempting these (and other edge) solutions, let us attempt to constrain the a priori unknown near-field coefficient  $B_{\widetilde{o}}$ in the

$B_{\widetilde{o}}$ in the  $\widetilde{o}$ expression for the opening

$\widetilde{o}$ expression for the opening  $w=B_{\widetilde{o}}x^{3/2}$ (

$w=B_{\widetilde{o}}x^{3/2}$ ( $x\rightarrow 0$). Using the inverted form of the elasticity equation (2.3) with

$x\rightarrow 0$). Using the inverted form of the elasticity equation (2.3) with  $K^{\prime }=0$, and formally passing to the asymptotic limit

$K^{\prime }=0$, and formally passing to the asymptotic limit  $x\rightarrow 0$ under the integral, we obtain

$x\rightarrow 0$ under the integral, we obtain

$$\begin{eqnarray}B_{\widetilde{o}}=\frac{8}{3\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}E^{\prime }}\int _{0}^{\infty }\frac{p(s)}{s^{3/2}}\,\text{d}s.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}B_{\widetilde{o}}=\frac{8}{3\unicode[STIX]{x03C0}E^{\prime }}\int _{0}^{\infty }\frac{p(s)}{s^{3/2}}\,\text{d}s.\end{eqnarray}$$ Since  $p(s\rightarrow 0)=-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{0}^{\prime }-\frac{3}{2}B_{\widetilde{o}}(V^{1/2}/Q^{\prime })s$ (table 2), the above integral expression for

$p(s\rightarrow 0)=-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{0}^{\prime }-\frac{3}{2}B_{\widetilde{o}}(V^{1/2}/Q^{\prime })s$ (table 2), the above integral expression for  $B_{\widetilde{o}}$ converges (finite) for the

$B_{\widetilde{o}}$ converges (finite) for the  $m\widetilde{o}$-edge (when

$m\widetilde{o}$-edge (when  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }=0$) and diverges for the

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }=0$) and diverges for the  $\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$-edge. This suggests that the underlining formal limit-taking procedure to arrive to (3.2) is not applicable to the latter (

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$-edge. This suggests that the underlining formal limit-taking procedure to arrive to (3.2) is not applicable to the latter ( $\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$-edge), while conversely (3.2) can be used to constrain coefficient

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$-edge), while conversely (3.2) can be used to constrain coefficient  $B_{\widetilde{o}}$ in the former case (

$B_{\widetilde{o}}$ in the former case ( $m\widetilde{o}$-edge). Specifically, we observe for the

$m\widetilde{o}$-edge). Specifically, we observe for the  $m\widetilde{o}$-edge that if the net pressure is negative in the entire crack coordinate domain (

$m\widetilde{o}$-edge that if the net pressure is negative in the entire crack coordinate domain ( $p(s)<0$ for all

$p(s)<0$ for all  $s>0$), which is suggested by the negative net pressure values in both the near field and far field, then (3.2) results in

$s>0$), which is suggested by the negative net pressure values in both the near field and far field, then (3.2) results in  $B_{\widetilde{o}}<0$ or, in other words, negative crack opening near the tip. This contradiction rules out the existence of the

$B_{\widetilde{o}}<0$ or, in other words, negative crack opening near the tip. This contradiction rules out the existence of the  $m\widetilde{o}$-edge solution (under the plausible assumption of the negative net pressure in the crack), which implies that the general solution to the problem does not have a well-defined limiting solution when both toughness and leak-off (or, conversely, ambient effective stress) equal zero.

$m\widetilde{o}$-edge solution (under the plausible assumption of the negative net pressure in the crack), which implies that the general solution to the problem does not have a well-defined limiting solution when both toughness and leak-off (or, conversely, ambient effective stress) equal zero.

The general solution of the fracture tip problem within the parametric pyramid transitions with increasing distance from the tip from the near-field  $k$ to the far-field

$k$ to the far-field  $m$-vertex, and in different limiting cases can collapse onto or be attracted to the series of faces and/or edges, as apparent from their parametric definitions. To identify non-dimensional parameters which fix a given solution trajectory in the parametric space, we follow the methodology of Garagash et al. (Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011) and introduce characteristic scales for the transition distance

$m$-vertex, and in different limiting cases can collapse onto or be attracted to the series of faces and/or edges, as apparent from their parametric definitions. To identify non-dimensional parameters which fix a given solution trajectory in the parametric space, we follow the methodology of Garagash et al. (Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011) and introduce characteristic scales for the transition distance  $\ell _{\ast }$, opening

$\ell _{\ast }$, opening  $w_{\ast }$ and pressure

$w_{\ast }$ and pressure  $p_{\ast }$ closely related to the evolution of the solution along a given edge in the parametric space between the two corresponding vertices, or the ‘edge scalings’.

$p_{\ast }$ closely related to the evolution of the solution along a given edge in the parametric space between the two corresponding vertices, or the ‘edge scalings’.

Edge scalings  $mk$,

$mk$,  $\widetilde{m}k$ and

$\widetilde{m}k$ and  $m\widetilde{m}$ are defined after Garagash et al. (Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011) such that the solutions for either

$m\widetilde{m}$ are defined after Garagash et al. (Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011) such that the solutions for either  $p(x)$ or

$p(x)$ or  $w(x)$ for the corresponding two vertices forming the edge in question ‘intersect’ at

$w(x)$ for the corresponding two vertices forming the edge in question ‘intersect’ at  $x\sim \ell _{\ast }$. For example, in the case of the storage

$x\sim \ell _{\ast }$. For example, in the case of the storage  $mk$-edge, we find the characteristic length by contrasting the

$mk$-edge, we find the characteristic length by contrasting the  $k$ and

$k$ and  $m$ asymptotes for the opening,

$m$ asymptotes for the opening,  $w_{\ast }=\ell _{k}^{1/2}\ell _{\ast }^{1/2}=\ell _{m}^{1/3}\ell _{\ast }^{2/3}$, while

$w_{\ast }=\ell _{k}^{1/2}\ell _{\ast }^{1/2}=\ell _{m}^{1/3}\ell _{\ast }^{2/3}$, while  $p_{\ast }$ follows from the elastic scaling constraint

$p_{\ast }$ follows from the elastic scaling constraint  $w_{\ast }/\ell _{\ast }=p_{\ast }/E^{\prime }$. Edge scalings which involve vertex

$w_{\ast }/\ell _{\ast }=p_{\ast }/E^{\prime }$. Edge scalings which involve vertex  $\widetilde{o}$ (i.e.

$\widetilde{o}$ (i.e.  $\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$ and

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$ and  $\widetilde{o}k$) are obtained similarly but also recognising that the

$\widetilde{o}k$) are obtained similarly but also recognising that the  $\widetilde{o}$-asymptote depends on the solution trajectory (via a priori unknown prefactor). In the

$\widetilde{o}$-asymptote depends on the solution trajectory (via a priori unknown prefactor). In the  $\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$-case the transition length scale

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$-case the transition length scale  $\ell _{\ast }$ is found by contrasting the leading order

$\ell _{\ast }$ is found by contrasting the leading order  $\widetilde{o}$-asymptote for the net pressure (i.e.

$\widetilde{o}$-asymptote for the net pressure (i.e.  $p\approx -\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }$) with that of the

$p\approx -\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }$) with that of the  $\widetilde{m}$-vertex, i.e.

$\widetilde{m}$-vertex, i.e.  $p_{\ast }=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }=E^{\prime }(\ell _{\widetilde{m}}/\ell _{\ast })^{3/8}$, while

$p_{\ast }=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }=E^{\prime }(\ell _{\widetilde{m}}/\ell _{\ast })^{3/8}$, while  $w_{\ast }$ follows from the elastic constraint. In the

$w_{\ast }$ follows from the elastic constraint. In the  $\widetilde{o}k$-scaling the characteristic pressure is taken equal to

$\widetilde{o}k$-scaling the characteristic pressure is taken equal to  $p_{\ast }=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{0}^{\prime }$. Using

$p_{\ast }=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{0}^{\prime }$. Using  $p_{\ast }$, elastic scaling constraint and balancing

$p_{\ast }$, elastic scaling constraint and balancing  $\widetilde{o}$- and

$\widetilde{o}$- and  $k$-vertex solutions, we find that

$k$-vertex solutions, we find that  $\ell _{\ast }=K^{\prime 2}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime 2}$ and

$\ell _{\ast }=K^{\prime 2}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime 2}$ and  $w_{\ast }=K^{\prime 2}/E^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }$. All of the above edge scalings are recorded in table 3.

$w_{\ast }=K^{\prime 2}/E^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }$. All of the above edge scalings are recorded in table 3.

Table 3. Characteristic distance from the tip  $\ell _{\ast }$, pressure

$\ell _{\ast }$, pressure  $p_{\ast }$ and opening

$p_{\ast }$ and opening  $w_{\ast }=(p_{\ast }/E^{\prime })\ell _{\ast }$, corresponding to the five scalings of the problem.

$w_{\ast }=(p_{\ast }/E^{\prime })\ell _{\ast }$, corresponding to the five scalings of the problem.

Comparing three transition (edge) length scales within a given parametric face of the pyramid  $m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$ allows us to identify a ‘trajectory number’ parameterising that face solution. Considering, for example, the zero-leak-in face

$m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$ allows us to identify a ‘trajectory number’ parameterising that face solution. Considering, for example, the zero-leak-in face  $m\widetilde{m}k$, one can introduce a single number expressible as a ratio of any two of the face’s three transition length scales (

$m\widetilde{m}k$, one can introduce a single number expressible as a ratio of any two of the face’s three transition length scales ( $\ell _{mk}$,

$\ell _{mk}$,  $\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}$, and

$\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}$, and  $\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}$) (Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011):

$\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}$) (Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011):

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}=\left(\frac{\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}}{\ell _{mk}}\right)^{1/6}=\left(\frac{\ell _{mk}}{\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}}\right)^{1/2}=\left(\frac{\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}}{\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}}\right)^{1/8}=\frac{C^{\prime }E^{\prime }}{K^{\prime }V^{1/2}}.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}=\left(\frac{\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}}{\ell _{mk}}\right)^{1/6}=\left(\frac{\ell _{mk}}{\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}}\right)^{1/2}=\left(\frac{\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}}{\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}}\right)^{1/8}=\frac{C^{\prime }E^{\prime }}{K^{\prime }V^{1/2}}.\end{eqnarray}$$ This number, which can be interpreted as a dimensionless leak-off or ambient effective stress (since  $C^{\prime }=Q^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }$), or non-dimensional reciprocal of toughness, parameterises solution trajectory within the

$C^{\prime }=Q^{\prime }\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }$), or non-dimensional reciprocal of toughness, parameterises solution trajectory within the  $m\widetilde{m}k$-face. The limiting case

$m\widetilde{m}k$-face. The limiting case  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow 0$ corresponds to the storage-dominated

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow 0$ corresponds to the storage-dominated  $mk$-edge solution

$mk$-edge solution

$$\begin{eqnarray}\text{zero leak-in},\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D712}=0:\quad k\underset{\ell _{mk}}{\rightarrow }m,\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\text{zero leak-in},\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D712}=0:\quad k\underset{\ell _{mk}}{\rightarrow }m,\end{eqnarray}$$ which transitions from the  $k$- to the

$k$- to the  $m$-vertex with distance from the tip over length scale

$m$-vertex with distance from the tip over length scale  $\ell _{mk}$ (shown by the blue coloured trajectory in figure 2). While the other limiting case

$\ell _{mk}$ (shown by the blue coloured trajectory in figure 2). While the other limiting case  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty$ corresponds to the separation of the corresponding transitional scales,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty$ corresponds to the separation of the corresponding transitional scales,  $\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}\ll \ell _{m\widetilde{m}}$, (3.3), leading to the nested solution structure corresponding to the succession of the two edge solutions (

$\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}\ll \ell _{m\widetilde{m}}$, (3.3), leading to the nested solution structure corresponding to the succession of the two edge solutions ( $\widetilde{m}k$ and

$\widetilde{m}k$ and  $m\widetilde{m}$)

$m\widetilde{m}$)

$$\begin{eqnarray}\text{zero leak-in},\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty :\quad k\underset{\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}}{\rightarrow }\widetilde{m}\underset{\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}}{\rightarrow }m,\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\text{zero leak-in},\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty :\quad k\underset{\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}}{\rightarrow }\widetilde{m}\underset{\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}}{\rightarrow }m,\end{eqnarray}$$ signifying transition with distance from the tip first from the  $k$- to

$k$- to  $\widetilde{m}$-vertex over length scale

$\widetilde{m}$-vertex over length scale  $\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}$ and then from the

$\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}$ and then from the  $\widetilde{m}$- to

$\widetilde{m}$- to  $m$-vertex over length scale

$m$-vertex over length scale  $\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}$ (shown by the brown coloured trajectory in figure 2).

$\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}$ (shown by the brown coloured trajectory in figure 2).

Similarly, for the zero-storage face  $\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$,

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty$, we define another number in terms of the ratios of any two of the corresponding three edge length scales (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty$, we define another number in terms of the ratios of any two of the corresponding three edge length scales ( $\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}$,

$\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}$,  $\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}$, and

$\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}$, and  $\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}$)

$\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}$)

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}=\left(\frac{\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}}{\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}}\right)^{1/6}=\left(\frac{\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}}{\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}}\right)^{1/2}=\left(\frac{\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}}{\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}}\right)^{1/8}=\frac{E^{\prime }}{K^{\prime }}\left(\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }Q^{\prime }V^{1/2}\right)^{1/3},\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}=\left(\frac{\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}}{\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}}\right)^{1/6}=\left(\frac{\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}}{\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}}\right)^{1/2}=\left(\frac{\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}}{\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}}\right)^{1/8}=\frac{E^{\prime }}{K^{\prime }}\left(\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime }Q^{\prime }V^{1/2}\right)^{1/3},\end{eqnarray}$$ which can be interpreted as dimensionless leak-in or a reciprocal of toughness. This number parameterises solution trajectory within the  $\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$-face. The limiting case

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}k$-face. The limiting case  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow 0$ corresponds to the leak-off-dominated

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow 0$ corresponds to the leak-off-dominated  $\widetilde{m}k$-edge solution, also a part of the limiting trajectory (3.5) in the

$\widetilde{m}k$-edge solution, also a part of the limiting trajectory (3.5) in the  $m\widetilde{m}k$-face. While

$m\widetilde{m}k$-face. While  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty$ corresponds to the separation of the relevant transitional scales,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty$ corresponds to the separation of the relevant transitional scales,  $\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}\ll \ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}$, (3.6), leading to the nested solution structure corresponding to the succession of the two edge solutions (

$\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}\ll \ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}$, (3.6), leading to the nested solution structure corresponding to the succession of the two edge solutions ( $\widetilde{o}k$ and

$\widetilde{o}k$ and  $\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$) with distance from the tip

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$) with distance from the tip

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty ,\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty :\quad k\underset{\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}}{\rightarrow }\widetilde{o}\underset{\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}}{\rightarrow }\widetilde{m}.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty ,\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty :\quad k\underset{\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}}{\rightarrow }\widetilde{o}\underset{\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}}{\rightarrow }\widetilde{m}.\end{eqnarray}$$ For the zero-toughness face  $m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$,

$m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty$, we can define another number in terms of the ratio of the

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty$, we can define another number in terms of the ratio of the  $\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$- and

$\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$- and  $m\widetilde{m}$-edge length scales

$m\widetilde{m}$-edge length scales

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\left(\frac{\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}}{\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}}\right)^{1/8}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }\left(\frac{Q^{\prime }}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime 1/2}V}\right)^{2/3},\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\left(\frac{\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}}{\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}}\right)^{1/8}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{o}^{\prime }\left(\frac{Q^{\prime }}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}^{\prime 1/2}V}\right)^{2/3},\end{eqnarray}$$ which can be interpreted as, e.g. a dimensionless effective confining stress. Note that  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ is not an independent parameter, but expressible in terms of the previously introduced leak-off

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ is not an independent parameter, but expressible in terms of the previously introduced leak-off  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}$ and leak-in

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}$ and leak-in  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$ numbers,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$ numbers,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$. This number parameterises solution trajectory within the

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$. This number parameterises solution trajectory within the  $m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$-face, such that

$m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$-face, such that  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}\rightarrow \infty$ corresponds to the separation of the two length scales,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}\rightarrow \infty$ corresponds to the separation of the two length scales,  $\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}\ll \ell _{m\widetilde{m}}$, (3.8), resulting in a solution comprised of the two edge solutions (

$\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}\ll \ell _{m\widetilde{m}}$, (3.8), resulting in a solution comprised of the two edge solutions ( $m\widetilde{o}$ and

$m\widetilde{o}$ and  $m\widetilde{m}$)

$m\widetilde{m}$)

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty ,\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty :\quad \widetilde{o}\underset{\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}}{\rightarrow }\widetilde{m}\underset{\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}}{\rightarrow }m.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty ,\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty :\quad \widetilde{o}\underset{\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}}{\rightarrow }\widetilde{m}\underset{\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}}{\rightarrow }m.\end{eqnarray}$$ The other limit,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=0$, corresponding to the viscosity-leak-in

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=0$, corresponding to the viscosity-leak-in  $m\widetilde{o}$-edge, is not expected to exist per discussion in the above. The behaviour of the solution within the

$m\widetilde{o}$-edge, is not expected to exist per discussion in the above. The behaviour of the solution within the  $m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$ and particularly how it approaches the non-existing

$m\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}$ and particularly how it approaches the non-existing  $m\widetilde{o}$-edge with diminishing value of

$m\widetilde{o}$-edge with diminishing value of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ is to be explored numerically.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ is to be explored numerically.

We note that in the case when the parametric conditions in (3.7) and (3.9) are combined, i.e. when  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty ,\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty ,\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty$, the three scales separate,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty$, the three scales separate,  $\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}\ll \ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}\ll \ell _{m\widetilde{m}}$, and the ‘triple-nested’ solution structure is realised

$\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}\ll \ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}\ll \ell _{m\widetilde{m}}$, and the ‘triple-nested’ solution structure is realised

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty ,\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty ,\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty :\quad k\underset{\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}}{\rightarrow }\widetilde{o}\underset{\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}}{\rightarrow }\widetilde{m}\underset{\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}}{\rightarrow }m,\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}\rightarrow \infty ,\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty ,\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty :\quad k\underset{\ell _{\widetilde{o}k}}{\rightarrow }\widetilde{o}\underset{\ell _{\widetilde{m}\widetilde{o}}}{\rightarrow }\widetilde{m}\underset{\ell _{m\widetilde{m}}}{\rightarrow }m,\end{eqnarray}$$as shown by the green coloured trajectory in figure 2.

For the fourth and final face of the pyramid, the zero-leak-off face  $m\widetilde{o}k$,

$m\widetilde{o}k$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}=0$, we can use the previously defined non-dimensional leak-in number

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}=0$, we can use the previously defined non-dimensional leak-in number  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$ to track solution trajectories, such that

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$ to track solution trajectories, such that  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}=0$ corresponds to the storage

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}=0$ corresponds to the storage  $mk$-edge and

$mk$-edge and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty$ corresponds to the non-existing limit of either the

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty$ corresponds to the non-existing limit of either the  $m\widetilde{o}$-edge or the

$m\widetilde{o}$-edge or the  $\widetilde{o}k$-edge. (Note that the

$\widetilde{o}k$-edge. (Note that the  $\widetilde{o}k$-edge can only be realised as the near or near-to-intermediate field of a given solution; thus, non-existence of the

$\widetilde{o}k$-edge can only be realised as the near or near-to-intermediate field of a given solution; thus, non-existence of the  $m\widetilde{o}$ solution, which would form the intermediate-to-far-field solution in the limit

$m\widetilde{o}$ solution, which would form the intermediate-to-far-field solution in the limit  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty$, implies the absence of the near-to-intermediate-field,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow \infty$, implies the absence of the near-to-intermediate-field,  $\widetilde{o}k$-edge, solution within the zero-leak-off face

$\widetilde{o}k$-edge, solution within the zero-leak-off face  $m\widetilde{o}k$.)

$m\widetilde{o}k$.)

3.3 Asymptotic expansions of the vertices

Some insight into how the solution departs from the vertices in the parametric space in response to small perturbation of problem parameters and distance from the fracture tip can be afforded by constructing corresponding asymptotic expansions.

3.3.1 Expansion near  $k$-vertex

$k$-vertex

The near-field  $k$-vertex expression (table 2) for the net pressure is simply given by the value at the tip set by the balance between the incipient fluid exchange and crack opening, respectively, and, thus, independent of the fluid flow along the crack channel. The latter becomes more important when moving away from the tip, and can be accounted for by incorporating next-order terms in the

$k$-vertex expression (table 2) for the net pressure is simply given by the value at the tip set by the balance between the incipient fluid exchange and crack opening, respectively, and, thus, independent of the fluid flow along the crack channel. The latter becomes more important when moving away from the tip, and can be accounted for by incorporating next-order terms in the  $k$-vertex asymptotic expansion (§ 1 of the supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2020.193). The

$k$-vertex asymptotic expansion (§ 1 of the supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2020.193). The  $k$-expansion for the net fluid pressure is given by

$k$-expansion for the net fluid pressure is given by

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D701}>0:\quad \frac{p}{E^{\prime }}=\frac{\ell _{k}^{1/2}}{\ell _{1}^{1/2}}\left[-\frac{1}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}^{3}}+\frac{1}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FE}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D701})}\left(\frac{x}{x_{o}}\right)^{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FE}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D701})}\right], & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D701}>0:\quad \frac{p}{E^{\prime }}=\frac{\ell _{k}^{1/2}}{\ell _{1}^{1/2}}\left[-\frac{1}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}^{3}}+\frac{1}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FE}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D701})}\left(\frac{x}{x_{o}}\right)^{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FE}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D701})}\right], & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ $$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D701}=0:\quad \frac{p}{E^{\prime }}=\frac{\ell _{k}^{1/2}}{\ell _{1}^{1/2}}\ln \left(\frac{x}{x_{o}}\right) & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D701}=0:\quad \frac{p}{E^{\prime }}=\frac{\ell _{k}^{1/2}}{\ell _{1}^{1/2}}\ln \left(\frac{x}{x_{o}}\right) & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ in the general  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}>0$ case and in the Carter’s

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}>0$ case and in the Carter’s  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow 0$ limit (Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011), respectively. Length scale

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}\rightarrow 0$ limit (Garagash et al. Reference Garagash, Detournay and Adachi2011), respectively. Length scale  $\ell _{1}$ is defined in terms of a pair of transitional length scales

$\ell _{1}$ is defined in terms of a pair of transitional length scales

$$\begin{eqnarray}\ell _{1}=(\ell _{mk}^{-1/2}+\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}^{-1/2})^{-2}.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\ell _{1}=(\ell _{mk}^{-1/2}+\ell _{\widetilde{m}k}^{-1/2})^{-2}.\end{eqnarray}$$ Exponent  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FE}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FE}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D701})$ in (3.11) is provided implicitly by