Introduction

Since being rolled out in 2008, the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme has radically transformed the provision of mental health services in England (Clark, Reference Clark2018). In an effort to substantially increase the availability of evidence-based psychological therapies, there has been significant investment into the training of a new workforce of psychological therapists. This new workforce consists primarily of psychological wellbeing practitioners (PWPs) and high intensity therapists (HITs), and already numbers several thousand practitioners. Government planning for the NHS demonstrates that this number is set to continue to rise significantly in the coming years (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2020; NHS England, 2019).

IAPT training programmes are a joint venture between education providers and IAPT services. Programmes typically last approximately one year, during which time trainees divide their time between university and their employing service. Alongside the formal teaching they receive at university, trainees undertake a range of exams, written assignments and clinical competency-based assessments (Department of Health, 2019; University College London, 2015). In service, trainees spend time shadowing qualified peers, receiving formal supervision, and building up a clinical caseload.

Despite its successes in increasing access to effective psychological therapies (Clark, Reference Clark2018; Wakefield et al., Reference Wakefield, Kellett, Simmonds-Buckley, Stockton, Bradbury and Delgadillo2020), worrying levels of stress, burnout and staff turnover have been reported amongst the qualified IAPT workforce (Health Education England, 2015; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Macdonald, Schroder and Mellor-Clark2015). Consequently, an increasing recognition of the need to focus on staff wellbeing has been evident in IAPT publications in recent years (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2020).

Research suggests that problematic levels of stress and burnout are common in trainee clinical psychologists (Cushway, Reference Cushway1992; Hannigan et al., Reference Hannigan, Edwards and Burnard2004) and trainee psychotherapists (Cushway, Reference Cushway and Varma1997). In common with these groups, IAPT trainees simultaneously manage positions as mental health professionals and university students. The elevated levels of stress and psychological disturbance documented in both these populations suggests that IAPT trainees could be particularly vulnerable to stress and stress-related problems (Morse et al., Reference Morse, Salyers, Rollins, Monroe-DeVita and Pfahler2012; Pascoe et al., Reference Pascoe, Hetrick and Parker2019; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Macdonald, Schroder and Mellor-Clark2015). Given this, it is important that consideration is given to the possibility for stress and burnout in the role.

Lazarus and Folkman’s (Reference Lazarus and Folkman1984) widely accepted transactional model of stress states that ‘psychological stress is a particular relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her well-being’ (Lazarus and Folkman, Reference Lazarus and Folkman1984; p. 20). Burnout is described as emotional and physical exhaustion that develops as a result of chronic interpersonal stressors on the job (Maslach and Leiter, Reference Maslach and Leiter2016). Amongst therapists both within and outside of IAPT, elevated levels of stress and burnout have been associated with reductions in professional functioning, job satisfaction and clinical effectiveness (Delgadillo et al., Reference Delgadillo, Saxon and Barkham2018; Pakenham and Stafford-Brown, Reference Pakenham and Stafford-Brown2012). Given the potential for stress and burnout during training discussed above, and the manifold ways in which elevated levels of stress and burnout have been shown to impact on clinician performance and functioning, exploration of these topics in relation to IAPT trainees is important.

Objectives

The purpose of this review is to establish what is known about the levels and perceived causes of stress and burnout in IAPT trainees. The specific questions the study seeks to answer are as follows:

(1) What is the current state of the evidence regarding stress and burnout in IAPT trainees?

(2) What are the levels of stress and burnout in IAPT trainees?

(3) What are the perceived causes of stress and burnout in IAPT trainees?

Method

Eligibility criteria

Both published and unpublished work was included in this review. To be included, studies had to meet all of the following inclusion criteria:

-

Report data relating to IAPT employees working as trainee or qualified HITs and/or trainee or qualified PWPs;

-

Report data regarding stress or burnout;

-

Report data from studies in which trainee HITs and/or trainee PWPs were eligible to take part, or data reporting the experience of training recalled by qualified staff;

-

Report original data-driven research findings;

-

Formally reported in a way that would allow for critical evaluation of the procedures and findings;

-

Report data between 2007 and 2020.

Data sources and search strategy

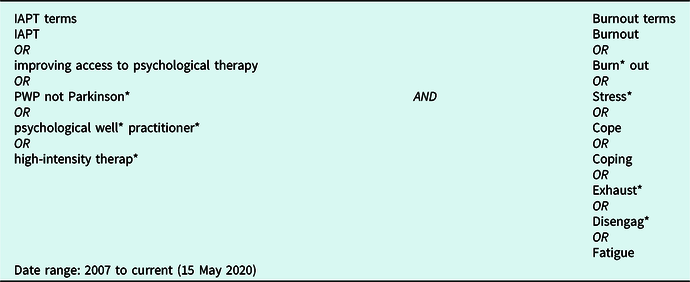

In order to identify all published and available unpublished work on stress and burnout in IAPT trainees, a systematic search was carried out on AMED, ASSIA, CINAHL, Cochrane CENTRAL, Cochrane Reviews, EMBASE, Medline, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, Scopus and SSCI. Combinations of keywords were used, using wildcards (the ‘*’ symbol) and Boolean operators (AND and OR) where appropriate (see Table 1). The search was run to identify any relevant work between 2007 (when the 11 IAPT Pathfinder sites were set up) and the day of the final search (15 May 2020). In addition to this systematic search of databases, searches were performed on OpenGrey and Google Scholar in an attempt to identify any further published or unpublished work. Hand searching of the reference lists of all included articles was also carried out.

Table 1. Search terms

Databases searched: AMED, ASSIA, CINAHL, Cochrane (CENTRAL and Reviews), EMBASE, Medline, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, Scopus and SSCI.

Screening and study selection

The systematic search described above identified a total of 893 articles which reduced to 615 following the removal of duplicates (see Fig. 1). Articles were then screened in stages. In order to remove studies which were obviously unrelated to the topic of this review, the first author carried out an initial broad screening based on title alone. Following this, the same author screened the remaining 182 articles again based on title and abstract. An online random number generator was used to identify 10% of these studies which were also screened in the same way by a second author in order to check for screening consistency. Results were compared between the two researchers who agreed fully on all papers except one; this disagreement was resolved through discussion and reference to the eligibility criteria.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

This process led to 44 papers being read in full by the first author. Of these, eight studies met the inclusion criteria and were subsequently included in the final review. In cases where insufficient information was available in the article to assess whether inclusion criteria were met, authors of the study in question were contacted for clarification. To ensure consistency throughout the screening process, the authors met several times to discuss the development of the process and the rationale for any decisions made.

Data extraction

Data extracted from the studies included the research questions, the participant information and sample size, the study type, measures used and summary of results. Table 2 presents an overview of the included studies.

Table 2. Summary of papers included in the systematic review

CD-RISC10, Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (Connor and Davidson, Reference Connor and Davidson2003); COPE, COPE Inventory (Carver et al., Reference Carver, Scheier and Weintraub1989); DASS, Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (Lovibond and Lovibond, Reference Lovibond and Lovibond1995); ECR, Experience of Close Relationships (Brennan et al., Reference Brennan, Clark, Shaver, Simpson and Rholes1998); FFMQ-SF, Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire-Short Form (Bohlmeijer et al., Reference Bohlmeijer, ten Klooster, Fledderus, Veehof and Baer2011); GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006); GHQ-12, General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg and Williams, Reference Goldberg and Williams1988); GSES, General Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer and Jerusalem, Reference Schwarzer, Jerusalem, Weinman, Wright and Johnston1995); HS, Hardiness Scale (Bartone et al., Reference Bartone, Ursano, Wright and Ingraham1989); HSE, HSE Management Standards Indicator Tool (Cousins et al., Reference Cousins, Mackay, Clarke, Kelly, Kelly and McCaig2004); JCQ, Job Content Questionnaire (Karasek et al., Reference Karasek, Brisson, Kawakami, Houtman, Bongers and Amick1998); MBI, Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach et al., Reference Maslach, Jackson and Leiter1996); OLB, Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (Demerouti et al., Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001); OSI-R, Occupational Stress Inventory-Revised (Osipow, Reference Osipow1998); PF-SOC, Problem-Focused Style of Coping (Heppner et al., Reference Heppner, Cook, Wright and Johnson1995); PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001); PSS-10, Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen and Williamson, Reference Cohen, Williamson, Spacapan and Oskamp1988); SCS, Self-Compassion Scale (Neff, Reference Neff2003); SMBM, Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure (Shirom, Reference Shirom, Cooper and Robertson1989); TARS, Training Acceptability Rating Scale (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Rawana and Capponi1989); TWIS, Therapist Work Involvement Scale (Orlinsky and Rønnestad, Reference Orlinsky and Rønnestad2005); WEMWBS, Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (Stewart-Brown and Janmohamed, Reference Stewart-Brown and Janmohamed2008).

Results

As the systematic search for this study yielded a heterogeneous collection of studies, and following the guidance of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2009), results are presented and discussed through a narrative synthesis approach.

Study characteristics

The eight studies included in the review form a varied collection of research, employing quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods approaches. Only two of the studies are published in peer-reviewed journals (Walklet and Percy, Reference Walklet and Percy2014; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017); the remaining six are doctoral theses. Both the total number of participants and the proportion of those who were IAPT trainees varied significantly between studies. One study (Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017) included trainees in their eligibility criteria but were unable to confirm how many of the final sample were trainees. Several studies reported data for both qualified and trainee IAPT staff. Of these, two studies (Kostaki, Reference Kostaki2018; Turnpenny, Reference Turnpenny2017) reported data in a manner that enabled comparison between these groups, whilst others (Walklet and Percy, Reference Walklet and Percy2014; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017) did not distinguish in the presentation of results between trainee and qualified staff. There was significant variation in use of measures with each of these studies employing a different measure for stress and burnout. As such, there was variation between these studies with regard to multiple aspects of the research.

Quality assessment

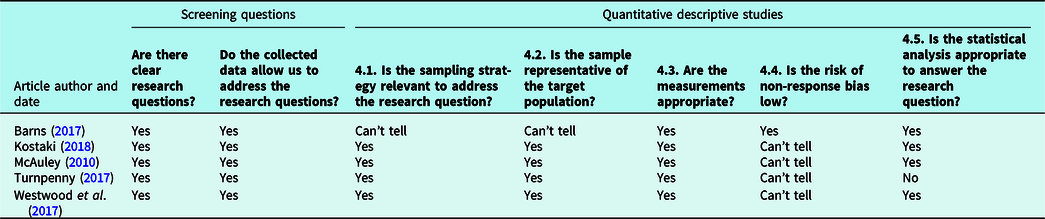

All studies were assessed for quality by the first author using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Pluye, Fàbregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo, Dagenais, Gagnon, Griffiths, Nicolau, O’Cathain, Rousseau and Vedel2018). The second author also independently appraised one of the included studies to check for appraisal consistency, and study characteristics and quality were frequently discussed between the authors. The MMAT is a reliable and efficient tool (Pace et al., Reference Pace, Pluye, Bartlett, Macaulay, Salsberg and Jagosh2012; Pluye et al., 2012; Souto et al., Reference Souto, Khanassov, Hong, Bush, Vedel and Pluye2015) for appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods research and was chosen for this review so that a consistent measure for appraisal could be used throughout. Each component addressed through the MMAT is scored either as ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘can’t tell’. The MMAT discourages the use of an overall score or rating (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Pluye, Fàbregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo, Dagenais, Gagnon, Griffiths, Nicolau, O’Cathain, Rousseau and Vedel2018), suggesting instead that a more detailed discussion of study quality should be developed. As such, Tables 2, 3 and 4 present how each individual article was rated using the tool, and a more detailed consideration of study qualities will be outlined throughout the discussion of the results.

Table 3. Study appraisal using the MMAT (2018) for quantitative studies

Table 4. Study appraisal using the MMAT (2018) for qualitative studies

Table 5. Study appraisal using the MMAT (2018) for mixed methods studies

Levels of stress and burnout in IAPT trainees

Stress

Four studies reported quantitative data regarding stress in IAPT professionals (Barns, Reference Barns2017; Kostaki, Reference Kostaki2018; McAuley, Reference McAuley2010; Walklet and Percy, Reference Walklet and Percy2014). Of these, two studies reported levels of stress in the ‘normal’ or ‘mild’ ranges, and two reported elevated levels of stress. Drawing firm conclusions from this regarding the prevalence or levels of stress in IAPT trainees is further complicated by several factors discussed below.

The finding that all trainee therapists in Barns’ (Reference Barns2017) study, and 95.4% of those in the study of McAuley (Reference McAuley2010) scored in the ‘normal’ or ‘mild’ range for stress prompted both authors to comment that their findings were notably out of keeping with the wider literature on stress in mental health professionals and trainees. Although these findings may appear encouraging, several factors indicate that caution should be applied when interpreting these results. McAuley’s (Reference McAuley2010) study of stress in IAPT trainees (n=44) is the oldest of those included in this review. With the IAPT programme and its associated training courses still in their infancy at the time of this research, it is likely that the experience of the trainees included would be notably different from trainees entering the workforce today. Since the time of this study for example, the training curriculums for both high and low intensity courses, as well as the national expectations regarding access rates have undergone significant changes, and consequently, the extent to which these results reflect current circumstances is unclear. Although Barns’ (Reference Barns2017) study of distress in trainee therapists also found levels of stress well below those frequently reported in other mental health professionals, it is important to note that IAPT trainees comprised only 6% (16 of the total 257 completers) of the final sample included in this research. The remaining 241 participants were trainee clinical psychologists and as such, the extent to which these findings generalise to the IAPT trainee population is unclear. Notably, IAPT trainees were also more likely to be amongst the 127 participants who dropped out of this study before completing the measures for a second time. Whilst there were no significant differences reported in terms of any of the variables of interest for those who dropped out before completing the measures a second time and those who did not, the over-representation of IAPT trainees amongst non-completers further indicates that caution must again be applied when interpreting these results for IAPT trainees.

In contrast to the two studies discussed above, the studies of Walklet and Percy (Reference Walklet and Percy2014) and Kostaki (Reference Kostaki2018) reported comparatively high levels of stress in IAPT professionals. Kostaki’s (Reference Kostaki2018) study of 207 IAPT clinicians used the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen and Williamson, Reference Cohen, Williamson, Spacapan and Oskamp1988) to measure stress and reported that IAPT professionals experience higher levels of stress than normative data for the measure and are ‘among the higher end’ of scorers recorded for healthcare professionals (Kostaki, Reference Kostaki2018). Using the GHQ-12 (Goldberg and Williams, Reference Goldberg and Williams1988), Walklet and Percy (Reference Walklet and Percy2014) reported that 29.5% of the IAPT professionals included in their study (n = 44) met clinical ‘caseness’. They comment that this finding indicates relatively high levels of stress in IAPT employees, similar to levels previously identified in mental health nurses, but lower than those reported in mental health social workers or clinical psychologists. The small proportion of participants (just three from a total of 44) who were trainees in this research limits its implications for the present review, and the fact that trainee and qualified results are not distinguished also further restricts the extent to which anything can be said with certainty about levels of stress in IAPT trainees specifically. Kostaki, however, whose Reference Kostaki2018 study included the highest total number of IAPT trainees (n=95) in any of those discussed here, distinguishes between trainee and qualified scores, noting that in descriptive terms, trainees scored higher on the Perceived Stress Scale than their qualified peers. The larger sample size and consequent power, as well as the broad recruitment strategy (recruiting via professional bodies and contacting all universities known to provide IAPT training) are notable strengths of this study. As such, its finding that trainees reported more stress than qualified peers and that the total sample scored in the higher end of healthcare professionals more generally, deserves further consideration.

Considered together, the studies included in the review present inconsistent findings regarding the levels of stress experienced by IAPT trainees. Although each study discussed here demonstrates a reasonably good level of overall quality, the variability of methods and measures used, the small numbers of IAPT trainees contributing to most results, and the fact that trainee and qualified scores were not always distinguished significantly limits the extent to which definitive conclusions may be drawn from them. Additionally, the fact that participants were in some cases drawn from only one or two IAPT settings may partially explain the variability in findings, as factors specific to particular work and training settings may have influenced the levels of stress identified.

Burnout

Three studies report quantitative data on levels of burnout in IAPT professionals (Nelson, Reference Nelson2019; Turnpenny, Reference Turnpenny2017; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017). However, the varied, and in some cases uncertain extent to which trainees contributed to these results means that firm conclusions and generalisations cannot be drawn from them regarding the levels of burnout in IAPT trainees specifically. Nelson’s (Reference Nelson2019) study of resilience and wellbeing in trainee PWPs (n=56) invited trainees from two cohorts at the same university to participate in research exploring whether a resilience workshop could improve trainee resilience and wellbeing. Using the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (Stewart-Brown and Janmohamed, Reference Stewart-Brown and Janmohamed2008) and the Shirom-Melamed Burnout Measure (Shirom, Reference Shirom, Cooper and Robertson1989), Nelson’s research reported that trainees had lower levels of wellbeing and higher levels of burnout than normative data for the measures used (Nelson, Reference Nelson2019), a finding the author attributes to the challenges associated with holding a stressful training position. Using a cross-sectional approach to explore the experience of burnout in IAPT staff, Turnpenny’s (Reference Turnpenny2017) study found that participants working across four IAPT sites scored significantly higher in the emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation components of burnout than those in previously published work on IAPT professionals or US comparison samples (Turnpenny, Reference Turnpenny2017). Such a finding suggests that IAPT professionals may be experiencing problematic levels of burnout and that the picture may be worsening as the IAPT programme develops. Although well powered overall, the implications of this finding for the present review are again limited by the fact that only 26% of the total participants (29 from a total of 112) were trainees.

High levels of burnout were also identified in IAPT staff working across Step 2 and Step 3 by Westwood and colleagues (Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017). In this research, IAPT professionals recruited from a variety of settings completed online questionnaires regarding job characteristics and levels of burnout. Approximately two-thirds of PWPs and half of HITs reported problematic levels of burnout. However, the extent to which this finding contributes meaningfully to the question regarding levels of burnout in IAPT trainees is unclear as although trainee PWPs and trainee HITs were eligible to participate, the researchers were unable to confirm how many (if any) of the total 201 participants were trainees. It is interesting to note that whilst several studies included in this review did not differentiate between trainee and qualified scores, all those that did so reported higher levels of stress or burnout in trainees (Kostaki, Reference Kostaki2018; Turnpenny, Reference Turnpenny2017). In keeping with the findings of Kostaki (Reference Kostaki2018) reported above, Turnpenny (Reference Turnpenny2017) indicates that trainees may experience more burnout than their qualified peers. Trainees in Turnpenny’s study scored higher on the emotional exhaustion (EE) and depersonalisation (DP) components, and lower on the personal accomplishment (PA) component of burnout when compared with qualified peers.

Considered together, these studies suggest that burnout is a cause for concern amongst IAPT staff in general and trainees in particular. Although there are few studies in the area, the studies included in this review represent a methodologically strong collection of research indicating that IAPT staff may be experiencing levels of burnout that are amongst the highest reported in mental health professionals (Morse et al., Reference Morse, Salyers, Rollins, Monroe-DeVita and Pfahler2012). Notably, all the studies presenting quantitative data regarding burnout in IAPT professionals report problematic or elevated levels. The existing evidence suggests that trainees may be experiencing levels of burnout that exceed normative samples (Nelson, Reference Nelson2019) and those of their qualified peers (Turnpenny, Reference Turnpenny2017). Although additional research is clearly needed to confirm and extend these findings, this notable preliminary finding should be a significant cause for concern for the national IAPT programme.

The perceived causes of stress and burnout in IAPT trainees

Significantly, no articles included in this review sought to openly explore the specific sources of stress or burnout in IAPT trainees. Despite this, six studies (Kostaki, Reference Kostaki2018; McAuley, Reference McAuley2010; Scott, Reference Scott2018; Turnpenny, Reference Turnpenny2017; Walklet and Percy, Reference Walklet and Percy2014; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017) report data relevant to this question and from this, tentative answers can begin to be formulated.

In two well-conducted qualitative pieces, Walklet and Percy (Reference Walklet and Percy2014) and Scott (Reference Scott2018) both used semi-structured interviews to explore issues regarding the sources of stress and burnout in IAPT clinicians. Notably, whilst both studies focused on the experience of stress or burnout in IAPT generally (not in training in particular), both report how the experience of training emerged as an important theme in their work. Whilst the six participants taking part in Walklet and Percy’s interviews for example were all qualified, it is notable that what is termed ‘high-stakes, in service training’ emerged as one of the seven themes regarding sources of stress. These practitioners commented on how the pressures of undergoing training whilst working on the job, and knowing that one’s continued employment was dependent upon passing the course, had been amongst the most significant sources of stress during their IAPT careers to date. Comments from participants suggested that a combination of clinical and academic targets and the constant threat of failing the course and losing their job meant that the training period was one during which they had struggled to maintain a work–life balance and which had subsequently been a significant source of stress. In a similar vein, Scott (Reference Scott2018) used interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) to explore the experience of burnout in IAPT staff and whilst only three of the total ten participants were trainees at the time of the research, Scott comments that ‘all participants discussed the concept of training’ (Scott, Reference Scott2018; p. 76). Again, participants commented on how they had felt they had not been given the time, support or reduced caseload required to benefit properly from the training and consolidate the material being learnt.

The in-depth exploration of the experience of these participants suggests that training to work in IAPT is a challenging and often stressful experience. Although small in number, both of these studies represent methodologically strong pieces of research, with the steps of the research process described in detail and clearly supported by verbatim quotes from participants.

McAuley’s (Reference McAuley2010) quantitative exploration of levels and sources of stress and strain in IAPT trainees further contributes to the current topic. Although no in-depth or open exploration regarding sources of stress during training is offered, the use of the Occupational Stress Inventory-Revised (OSI-R) (Osipow, Reference Osipow1998) provides some tentative indications regarding the sources of stress in IAPT trainees that may be more generalisable to trainees working throughout IAPT services. Although, as discussed above, 95.4% of trainees scored in the normal range for total perceived stress, the highest overall source of stress identified through the OSI-R was on the ‘Role Boundary’ component. McAuley interprets this finding as potentially indicating that trainees’ dual position as NHS employees and university students may be experienced as a source of stress for some trainees. Such an interpretation appears to fit well with the accounts offered by participants in both Walklet and Percy (Reference Walklet and Percy2014) and Scott (Reference Scott2018), where the competing demands of university and employment represented a notable source of stress for participants. The analyses reported in McAuley’s thesis also provide some tentative evidence that sources of stress may differ between high- and low-intensity trainees. For HIT trainees, the primary source of stress identified through the OSI-R was on the ‘Responsibility’ component, suggesting that the higher clinical responsibility and complexity handled by HIT trainees may lead to comparatively higher levels of stress with regard to this component of their work. For PWP trainees conversely, the ‘Role Insufficiency’ component emerged as a more important source of stress, suggesting that low-intensity trainees may feel bored, under-utilised or unclear about how their career is progressing and that consequently, this aspect of their role leads to comparatively higher levels of stress. Although interesting, it is important to keep in mind when interpreting these findings that any suggestions offered by this study are constrained by the remit of the OSI-R.

In the studies of Kostaki (Reference Kostaki2018), Turnpenny (Reference Turnpenny2017) and Westwood et al. (Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017), factors such as demographic information, job characteristics and measures of how therapists perceive their relationship to their clients, were used to quantitatively identify predictors of stress and burnout in IAPT clinicians. Although the measures used and results generated in these studies were not intended to address the perceived causes of stress or burnout during training in particular, interpreted with due caution, these results offer further insight into the question under review here.

Kostaki (Reference Kostaki2018) used the HSE Management Standards Indicator Tool (Cousins et al., Reference Cousins, Mackay, Clarke, Kelly, Kelly and McCaig2004) to measure perceived potential stressors at work and found that all seven of the work-related stressors measured by the tool were significantly negatively related to perceived stress. As such, for the IAPT therapists in this sample, better psychosocial working conditions – including things such as a more manageable workload, more positive relationships with colleagues and more managerial support - were associated with less perceived stress. It is worth noting again that Kostaki’s (Reference Kostaki2018) study included the highest total number of IAPT trainees of all the studies included in this review. As such, the implications of these findings for IAPT trainees may be important.

Using the Therapist Work Involvement Scale (Orlinsky and Rønnestad, Reference Orlinsky and Rønnestad2005), Turnpenny (Reference Turnpenny2017) found that the way IAPT clinicians perceive their relationship with clients was a particularly important factor relating to burnout. Being unsure how best to support clients, feeling unable to promote therapeutic change or unable to empathise with clients for example, were all associated with higher burnout. Turnpenny’s study also identified that lower levels of supervision were associated with higher levels of the depersonalisation component of burnout, a finding mirrored in that of Westwood and colleagues (Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017) that increased hours of supervision was associated with lower levels of burnout in PWPs.

Notably, the studies of Kostaki (Reference Kostaki2018), Turnpenny (Reference Turnpenny2017) and Westwood et al. (Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017) all converged on the finding that higher therapist workload was an important predictor of stress and burnout. This point may be particularly relevant for the present question when considered in relation to the findings discussed above regarding IAPT trainees’ perceptions that the high workload managed across the training period is a notable cause of stress and burnout. The findings discussed here appear to indicate that high workloads (as evidenced by factors such as hours of overtime, hours of clinical work or time spent inputting data) may be important factors relating to stress and burnout both for qualified and trainee staff.

Although limited by the remit of the measures used and the numbers of trainees contributing to results, these three studies then provide an important additional insight into the potential sources of stress and burnout in IAPT trainees and clinicians. Taken together, the studies of Kostaki (Reference Kostaki2018), Turnpenny (Reference Turnpenny2017) and Westwood et al. (Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017) suggest that the work environment and organisational structure in which IAPT clinicians and trainees work has an important impact on stress and burnout. To clarify the extent to which such findings explain the sources of stress and burnout during training specifically, future research presenting results for trainees separately and including mixed methods or qualitative approaches is needed.

Discussion

The findings of this review are drawn from a small pool of research made up primarily of unpublished doctoral theses. Whilst the overall quality of each included study is generally strong, it is notable that the extent to which each study contributes meaningfully to the questions of this review is limited by several factors. The proportion of IAPT trainees participating in studies is frequently small and occasionally uncertain. Several studies were under-powered when based on trainee participants alone. In a number of studies, the scores of trainees are not differentiated from their qualified peers, making the drawing of conclusions regarding stress or burnout in IAPT trainees specifically, difficult. With several articles reporting data on participants working in just one or two IAPT settings, it is also conceivable that organisational factors specific to one or more services may have influenced results, thus limiting their generalisability. As such, the findings of this review suggest that there is as yet insufficient evidence to draw clear conclusions regarding the levels and perceived sources of stress and burnout in IAPT trainees. Consequently, the findings discussed here must be interpreted with due caution. Despite this, the evidence that is presented tentatively suggests that IAPT trainees may be experiencing elevated levels of stress and burnout that are equal to or greater than those of their qualified peers, and amongst the higher end of mental health professionals more generally. This tentative finding should be of interest to IAPT services, education providers and the national IAPT programme. Several studies report data in a way that enables the comparison of qualified staff and trainees working as PWPs with those working as HITs. The small literature on this point is inconclusive, with differences being identified such that low-intensity staff and trainees report higher levels of stress and burnout in some studies (Kostaki, Reference Kostaki2018; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Morison, Allt and Holmes2017) but not in others (McAuley, Reference McAuley2010; Turnpenny, Reference Turnpenny2017).

The question regarding the primary sources of stress or burnout for IAPT trainees has, to our knowledge, not been explored in depth and as such, understanding in this area is limited. The studies reviewed here suggest that the demands of managing a challenging clinical role alongside a fast-paced academic training position are such that many trainees experience the training year as a period during which work–life balances slip and problematic levels of stress and burnout are experienced. The fact that continued employment depends on passing each component of the course also appears to be a significant stressor for many trainees. Whilst a number of IAPT training providers have begun in recent years to accept a small number of self-funded places, the overwhelming majority of IAPT trainees are employed by IAPT services throughout their training and to retain their jobs at the end of the training period, all aspects of the course must be passed in full. The research reviewed here appears to suggest that the pressure of this fact adds an additional weight to the training experience. As university students and mental health professionals, IAPT trainees are at an elevated risk for stress and burnout on two fronts (Morse et al., Reference Morse, Salyers, Rollins, Monroe-DeVita and Pfahler2012; Pascoe et al., Reference Pascoe, Hetrick and Parker2019). The studies reviewed here suggest that holding these dual roles is itself an additional risk factor. Managing conflicting demands on time, being bound by two sets of policies, and answering to both service supervisors and university lecturers concurrently may mean that IAPT trainees are vulnerable to a further source of stress emanating directly from the fact of holding dual roles.

Interestingly, this review found that all known studies reporting data on burnout reported problematic and elevated levels, whilst only two of the four studies reporting data on stress did the same. One potential explanation of this may be that IAPT professionals and trainees are more vulnerable to burnout than to stress. Despite areas of overlap between the concepts of burnout and stress, it is possible that burnout, with its emphasis on emotional exhaustion, cynicism and reduced personal accomplishment, more closely encapsulates the problems to which IAPT clinicians and trainees are vulnerable. The emotionally draining nature of fast-paced, high-volume work could mean that burnout then is a larger threat to IAPT staff than the experience of stress. Alternatively, the discrepancies in findings between those reporting data on burnout and those on stress could also be a product of the significant variation in measures used across studies. As discussed above, such variation renders comparisons between studies difficult and consequently, it may be desirable for the field to seek to standardise the measures used in future research. To understand such points in more detail, future research is required, and recommendations for such research are made below.

Strengths and limitations

Although IAPT has now been training psychological therapists for more than a decade, this is the first study to systematically review the available evidence regarding the levels and perceived causes of stress and burnout in this population. The findings of the review are however constrained by a number of limitations. Firstly, a protocol for this review was not registered at the inception of the project, and as such, the completed review reported here cannot be compared with a protocol plan. Additionally, whilst a second author was involved in screening or reading articles at multiple stages as outlined above, and the research team met frequently to ensure consistency, the fact that the screening of the 44 full texts was carried out by the primary researcher alone is a further limitation.

Conclusion

The results of this review tentatively suggest that stress and burnout are significant issues for IAPT trainees. The literature on this topic has, however, been identified as under-developed. More research, including qualitative research that explores the perceived causes of stress during training, and more highly powered studies recruiting larger numbers of IAPT trainees are needed to understand this in more detail. The findings of this review must then be considered in the context of the under-developed literature from which they have arisen. However, given that there exists already significant evidence regarding the adverse effects that excessive stress or burnout has on academic learning (Pascoe et al., Reference Pascoe, Hetrick and Parker2019), clinical effectiveness (Delgadillo et al., Reference Delgadillo, Saxon and Barkham2018), clinical decision making and ethical practice (Elman and Forest, Reference Elman and Forrest2007), the findings discussed here suggest that trainee wellbeing should be further considered by IAPT services, education providers and the national IAPT programme, as further IAPT expansion is planned.

Recommendations and future research

The findings of this review suggest that more research is needed to understand the levels and causes of stress and burnout in IAPT trainees. Future research should seek to include larger samples of IAPT trainees. Researchers in this area should also consider the measures used, seeking to ensure that chosen measures are the most relevant for the construct under consideration, and making efforts to follow practice in the existing literature base, as this will help improve the extent to which findings can be compared with related research. Any research presenting findings for both trainee and qualified IAPT staff should present and discuss findings separately, as the levels and perceived causes of stress amongst these populations probably differ. Additionally, researchers should consider presenting findings for high- and low-intensity trainees separately, as the perceived causes and levels may differ between the two roles. Understanding how the perceived causes and overall levels of stress differ between high- and low-intensity trainees will help educators and services better understand how to support trainees during the training period. Finally, in-depth qualitative research exploring the specific causes of stress during training is needed to help better understand what the perceived causes of stress are during training, and how they change across the training period.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical statement

No ethical approval was required for this review. However, the authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BPS and BABCP.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Key practice points

(1) This review has identified an important gap in the existing literature regarding stress and burnout in IAPT trainees.

(2) The existing literature tentatively suggests that IAPT trainees may experience levels of stress and burnout that are higher than their qualified peers, and in the higher end of healthcare professionals more generally.

(3) Future research on the topic should present IAPT trainee and qualified results separately and should also differentiate between high- and low-intensity trainees.

(4) Future research requires more highly powered studies, as well as mixed or qualitative approaches to further understand the perceived causes of stress and burnout.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.