Introduction

This article examines the discursive construction of prevention in the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda. The WPS agenda, as it has become known, derives from the adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (UNSCR 1325) in the year 2000; this resolution was the first in the sequence of ten resolutions adopted by the Council under the title of ‘Women and Peace and Security’. UNSCR 1325 is frequently described as a ‘watershed’ or ‘landmark’ moment in the international peace and security governance apparatus.Footnote 1 The resolution is highly significant not only because it represented the first time the Council had debated the gendered effects of conflict and the gendered exclusions in conflict prevention and resolution but also because of the resolution's co-production by representatives of UN member states, UN officials, and civil society practitioners and advocates.Footnote 2 The overarching principles of the WPS agenda are usually grouped into ‘pillars’, of which there are four: (1) the participation of women in peace and security governance; (2) the protection of women's rights and bodies in conflict and postconflict environment; (3) the prevention of violence, which is the focus of the present investigation; and (4) relief and recovery, which involves gender-sensitive humanitarian programming in the wake of disasters and complex emergencies, as well as the inclusion of women in postconflict reconstruction.

This research engages the ‘prevention’ pillar, which has been called the ‘weakest “P” in the 1325 pod’.Footnote 3 The dynamics of prevention have been widely contested in scholarship on WPS, not least in regard to Resolution 2242, which purports to offer a new articulation of prevention in its focus on counter-terrorism and countering violent extremism. This investigation is driven by a central puzzle related to the construction of prevention in the WPS agenda; the questions that animate the study presented here are: first, how is prevention constituted in the policy architecture of the WPS agenda?, and, second, what are the effects of having prevention thus constituted? I argue that an examination of prevention in the Women, Peace and Security agenda reveals its paradoxical construction: prevention is constituted as something other than (military) security but it is governed by dominant logics of security and militarism. This insight provides a useful complement to existing scholarship on prevention as a technique of governmentality, as analysts can better understand the effects and affordances of prevention when it is shown that prevention is not only constructed through an anticipatory logic of security but also through a logic of militarism, both of which dominate the subordinate logic of peace that is also evident in the construction of prevention in the WPS agenda. The organisation of prevention discourse in accordance with these logics, and the ways in which these logics are constituted, is discussed further below. I further contend that recognising prevention as a paradox, as a concept that is constituted within the contemporary system of security governance by logics of its own inhibition, forces ever greater scrutiny towards the concept of security we use to think with, as well as opening up the possibility of reproducing prevention in the WPS agenda according to different logics, or elevating the logic of peace that I identify.

I develop this argument in three sections. In the first section, I briefly review research on prevention, putting this literature into conversation with broader literatures on the governance of peace and security, to develop an argument about the performative and constitutive effects of governance practices in the domain of peace, security, and prevention. Specifically, I engage with scholarship on the governmentality of prevention. Second, I outline how it is possible to excavate logics (in this case, logics of peace, militarism, and security) through discourse analysis applied to texts (in this case, the WPS resolutions with which I am working), and briefly discuss the possibilities and limitations of this methodology. In the third section I develop the argument that prevention is constructed in the WPS agenda such that it represents a paradox. I examine the ten current WPS resolutions to draw out the constructions of prevention in the primary policy architecture of the WPS agenda. I show how the prevention pillar is manifested through unstable and sometimes contradictory articulations of prevention itself. I present a close reading of the resolutions, to show how the dominant constructions of prevention in the resolutions relies on logics of militarism and security, which then bring into play the state-based, masculinised, and violence-prone ideas and ideals for which conventional militarised/security discourse is widely critiqued.Footnote 4 In conclusion, I propose that the critical potential of such an argument lies both in reconstructing prevention in the WPS agenda according to different, or subordinate, logics and in the potential of undoing militarism/security – as the manifestation of prevention in practice – in queer, feminist, decolonial, and posthuman ways of knowing and encountering the world.

Examining the governance of conflict, prevention, and security

This analysis is situated within the broader literature on the governance of peace and security, particularly the critical tradition that explores the productive power of techniques and rationalities pertaining to conflict, prevention, and security.Footnote 5 Deliberate techniques of (bio)power have constitutive effects in terms of their obvious impact on our world(s); the concepts with which we work and think in the realm of conflict, prevention, and security also have such effects. From a perspective that accepts the ontological significance of discourse,Footnote 6 I propose, in line with existing scholarship, that theories and policy prescriptions pertaining to conflict, prevention, and security bring into being particular configurations and operations of power and authority that render certain actions thinkable/permissible while foreclosing the consideration of alternatives. Simply put, the governance of conflict, prevention, and security does not only ‘live’ or occur in the overt expression or application of power and authority – in what we might think of as ‘implementation’ – but its reproduction and the conditions of its legitimacy can also be traced through the discourses that articulate and (at least temporarily stabilise) its various meanings and practices.

The global governance of peace and security has cohered over the last decades in the form of the so-called ‘liberal peace’ paradigm, ‘based on a consensus that democracy, the rule of law and market economies would create sustainable peace in post-conflict and transitional state and societies, and in the larger international order that they were a part of’.Footnote 7 The legitimacy, or otherwise, of the liberal peace has been fiercely contested in scholarly literature on peace and security governance, with the emergence of a robust research agenda that interrogates the ways in which peace interventions ‘tend to reify state sovereignty, fail to address adequately issues related to justice, reconciliation, welfare, and gendered power, and validate “top-down institutional neoliberal and neocolonial” practices’.Footnote 8 Peace and security interventions inform and structure behaviours, practices, and the formulation of ‘solutions’ to the ‘problems’ identified in what Séverine Autesserre calls ‘peaceland’, the space of post-conflict peace interventions by international institutions.Footnote 9 Critical literature on peace interventions, postconflict peacebuilding, and development has examined the ways in which the techniques and rationalities associated with peace and security governance are produced by and, productive of, specific configurations of power and thus constitutive of specific forms of subjectivity.Footnote 10

Of particular interest here is the ways in which the positioning of prevention as a technique of security governance, seen from this perspective as a set of discursive practices that have material effects in the world, produces subjects, objects, and the relationships between them. The analysis of conflict prevention as a political project, dated back by some to the Congress of Vienna in 1815,Footnote 11 has tended to focus on ‘what works’ in conflict prevention,Footnote 12 rather than asking how prevention discourse functions. There is an emerging literature now, though, that examines – mostly with reference to new policy initiatives aimed at preventing ‘violent extremism’ or related forms of political violence – how prevention discourse produces certain possibilities while excluding others. This body of work situates prevention within the broader discussion of liberal peace and its (bio)political rationalities of governance, arguing, for example, that ‘[g]lobal liberal governance … responds to the turbulence of emerging political complexes by forming its own emerging strategic complexes as a means of dealing with the instances of violence that the densely mediated policies of the West periodically find unacceptable there or in response to the security threats that they are generally said to pose’.Footnote 13 Prevention is located here within the ‘emerging strategic complex’ or architecture of governmentality aimed at dealing with violence.Footnote 14

A particularly noteworthy example of scholarship in this field is work by Charlotte Heath-Kelly on logics of prevention.Footnote 15 In line with the above, Heath-Kelly examines prevention discourse in the form of UK counter-terrorism policy and traces a shift in UK Prevention of Terrorism Acts from a criminal justice approach to a ‘regime of risk’.Footnote 16 Prevention, in this context, is configured according to logics of pre-emption rather than punishment/deterrence. In a related piece of research, which applies a critical risk perspective to the UK's PREVENT Strategy and its construction of radicalisation,Footnote 17 Heath-Kelly argues that ‘PREVENT actively tries to induce specific types of conduct from British Muslim communities while also securitising them in terms of “risk”.’Footnote 18 Thus, prevention discourse is linked to security in terms of its sociopolitical function in the constitution of subjects: it produces certain subjects that are securitised. The subjectivities produced through prevention discourse in the UK, as Heath-Kelly deftly shows, are at once vulnerable and risky, but the will to prevent – to govern subjects through discourses of prevention – is itself rendered risky because of the necessarily incomplete knowledge about those subjects that informs prevention decision-making.Footnote 19 The partiality of knowledge/power, or ‘gap’, identified by Heath-Kelly in UK prevention discourse is alibied or denied by conventional and sovereign security actions, exemplified in the use of force (Heath-Kelly gives the example of the shooting by London Metropolitan Police of Jean Charles de Menezes in 2005).Footnote 20 Thus, Heath-Kelly shows how UK prevention discourse is organised in accordance with a logic of security.

Conventional logics of security permit the use of lethal force in service of the state, binding security to the state and its territorial integrity. Within this view, which could be labelled ‘national security’ discourse, ‘states are … the object to which security policy and practice refers and humans can only be secured to the extent that they are citizens of a given state’.Footnote 21 The insecurities produced by this concept of security is illustrated well by Heath-Kelly's analysis of the ‘execution-style killing’ of de Menezes, mentioned above.Footnote 22 Feminist and other critical scholars, of course, have worked to challenge and undermine this narrow envisioning of security for many decades, arguing for a much more expansive conceptualisation that recognises the many ways in which security – and insecurity – functions and manifests. Many examples exist: analysing the leakage of tonnes of methyl isocyanate from a chemical factory owned and operated by the Union Carbide Corporation in the Indian city of Bhopal as an event that threatened the security of thousands in the local area shows how ‘socio-political arrangements’ that marginalise some and privilege others ‘are implicated in the production of threats and injustices’;Footnote 23 and ‘everyday insecurity’Footnote 24 is created through endemic sexual violence in the military – an institution that is notionally intended to provide security for populations.Footnote 25

Given the centrality of security discourse to the state, and the ways in which prevention can be ‘filled’ with an anticipatory logic of security in practice – intertwined as it is with risk and pre-emption, as discussed above – a close analytical scrutiny of the way that security produces political possibilities is essential. There is a wealth of resources available to us if we seek to revise our discourse of security in recognition of its imbrication with prevention; the collective imaginings of creative and undisciplined scholarsFootnote 26 conjure ways of thinking security far greater in potential than the narrow, militarised, material concept of security that haunts the ‘halls of power’, to reappropriate Janet Halley's phrase.Footnote 27 Approaches to security that are queer,Footnote 28 feminist,Footnote 29 decolonial,Footnote 30 posthuman,Footnote 31 and those that are as yet unformalised as ‘approaches’ as such,Footnote 32 offer vivid and potentially transformative figurations of security that could enable those working in service of prevention to realise the promise of a world free – or at least freer – from violence. Such approaches to security would, of course, (re)produce different configurations of power and different constellations of subjects and objects, rendering possible different security actions and security knowledges.

Heath-Kelly and others demonstrate that prevention operates as a technique of governmentality, and show, through their careful analysis, the effects of prevention as it is constituted in counter-terrorism discourse. A focus on the biopolitics – and necropoliticsFootnote 33 – of prevention illuminates the ways in which the concept, when articulated into particular discursive formations, functions to govern, and produce, subjects and the relations between them in particular ways. Frequently, these productive possibilities reinforce the power and authority of the state over the body/life/death of the citizen-subjectFootnote 34 and concretise the effects of constructing prevention in accordance with a logic of risk and pre-emption. In the analysis I present below, I show that prevention is constituted in the WPS agenda in three distinct and different ways: through a logic of security; a logic of militarism; and a (much subordinate) logic of peace. A logic of security securitises prevention, in accordance with the narrow conventional understanding that articulates security as the survival of the sovereign state. A logic of militarism militarises prevention, predicating prevention on the availability and suitability of military institutions and solutions to mitigate conflict. A logic of peace, conversely, pacifies prevention, constituting prevention as the transformation of conflict, violence, and peacelessness into peace. Prevention can thus be articulated into multiple and quite different constellations of meaning – meanings that are fundamentally at odds, creating the paradox of prevention alluded to in the title of this article.

Discourse and logics: On method

Following a Derridean deconstructive approach to a text, it is possible to identify ‘the mechanisms, processes and practices through which a text orients, balances, and structures itself’,Footnote 35 through the application of ‘pressure’ to those moments of textual balance.Footnote 36 Deconstructive discourse analysis can show how subjects and objects are constituted as known/knowable, and how the discourse in question creates relational chains of meaning between these subjects and objects such that they are known/knowable in particular ways – according to particular logics. Logics organise a discourse, and produce, through signification, the overarching semblance of fixity that allows for the expression of the known/knowable. These logics are never predetermined, and it is in fact part of the ethos of deconstructive discourse analysis that the taking apart of discourse is always a project of radical possibility. The ‘centre’ or logics of the discourse that hold together certain possibilities, while precluding others, create instead of instability the appearance of totality (though of course such an appearance of totality is always precarious).Footnote 37

The idea that discourses are held together by logics is of central importance in this research. Logics structure the organisation of concepts within discourse, creating associative chains of value and hierarchy that structure the position and relationship of subjects and objects. Different logics inform different discourses that have radically different effects. If we take security discourses as an example, discourse on national security, for example, underpinned by a logic of state-centrism and a logic of anarchy, produces very different political possibilities (and policy prescriptions) than discourse on human security, underpinned by a logic of equality, and a logic of dignity. Similarly, different discourses of gender construct masculine subjects as either aggressors or protectors (though these are of course intertextually articulated with other discourses and logics that constitute some masculine subjects as aggressors and some as protectors – ‘virtuous masculinity depends on its constitute relation to the presumption of evil others’).Footnote 38 The theoretical claim here is simply that discourses are governed by logics, and that both discourses and logics have constitutive effects – they produce, rather than describe, the worlds we encounter as researchers.

To excavate the logics of discourse, to apprehend the construction of meaning, a researcher can deploy textual analytical strategies in a deconstructive mode. For this investigation, I have selected Roxanne Lynn Doty's methods of analysis,Footnote 39 involving the analysis of predication and subject-positioning. As Doty explains, ‘together, these methodological concepts produce a “world” by providing positions for various kinds of subjects and endowing them with particular attributes’.Footnote 40 Crucially, this world then makes possible certain kinds of activities, outcomes, and sensibilities, while other possibilities are foreclosed. This method of analysis is attentive to

how a discourse produces this world … how it renders logical and proper certain policies by authorities and in the implementation of those policies shapes and changes people's modes and conditions of living, and how it comes to be dispersed beyond authorized subjects to make up common sense for many in everyday society.Footnote 41

The ‘common sense’ of prevention is thus what is at stake in this analysis.

Of course, prevention discourse, even when limited to its articulation in the WPS agenda, exists beyond the Security Council resolutions that make up the formal architecture. There are many other sites and artefacts of WPS practice that are worthy objects of study; research might engage, for example, the articulation of prevention discourse in the UN Secretary-General's annual reports to the Council on women, peace and security, or in different national contexts through examination of national action plans for the implementation of the WPS agenda.Footnote 42 How prevention discourse operates and travels in institutional contexts might also be interrogated, through interviewing staff associated with prevention-focused initiatives undertaken under the auspices of the United Nations, or the African Union, or NATO.Footnote 43 These are all important terrains and vectors of prevention discourse and, to better understand the specific logics of prevention in these contexts, future research should carefully examine the sites and artefacts that articulate prevention in detailed and contextualised analysis. The focus of this research, however, is the WPS resolutions, as a component of broader WPS practice. Although the WPS agenda cannot be reduced to the resolutions that represent its policy architecture, the resolutions are the negotiated and agreed upon product of UN member state and civil society deliberations about priorities and emphases for the agenda at the point of adoption. They are therefore meaningful policy objects that, taken together, reveal baseline state and civil society agreements and parameters of the agenda, and can be analysed as part of the discursive terrain of the agenda.Footnote 44

The insights derived from such an analysis are necessarily partial, both in terms of the ability of a single study to capture the complexity of WPS practice, and in terms of the method's engagement solely with the conditions of possibility of implementation, rather than implementation itself. The study of implementation requires different questions, and different techniques. Similarly, a discourse-theoretical analysis of the resolutions cannot reveal how or why the resolutions contain the language that they do; the process of negotiation among member state representatives and the advocacy efforts of allied actors can be elicited in interview or through participant-observation and these are important avenues of enquiry. The aim here is not to suggest that resolutions – or indeed any other document or textual artefact – are indicative of how WPS works, and is worked with, in implementation, but to make the rather different argument that the words of WPS matter, in structuring the conditions of WPS action. Discourse-theoretical methodology conceives of textual practice as a significant site for analysis in its own right, rather than as backdrop to, or documentation of, implementation practice. This research shows how different logics of prevention, configuring different meanings of prevention in WPS prevention discourse, open up various possibilities while foreclosing others. The affordance of discourse-theoretical methodology, in which logics and other forms of discursive arrangement are excavated, is to demonstrate not only the productive power of text, but also the contingency of meaning, such that meanings can change. With shifts in meaning construction, the realities constituted by contemporary configurations of discourse themselves become visible as contingent; such an approach allows people ‘to imagine how their being-in-the-world is not only changeable, but perhaps, ought to be changed’.Footnote 45 Given the pressing significance of prevention efforts in world politics, and the dominance, as I argue below, of logics of militarism and security in WPS prevention discourse, a methodology that reveals the contingency of such dominance is, while necessarily limited, potentially fruitful indeed.

Prevention in the Women, Peace and Security agenda

The United Nations, as the institutional home of the Women, Peace and Security agenda, has a long, if somewhat chequered, history of prevention in rhetoric and practice. UN prevention discourse more broadly is grounded in the first Article of the UN Charter, which commits member states to, among other things, such collective actions as are necessary ‘for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace’.Footnote 46 Subsequent Secretaries-General have reaffirmed or rearticulated the relative priority of conflict prevention: Kofi Annan, for example, saw prevention as central to the role of the Secretary-General, and was committed both to developing regional prevention alliances and to equipping the Secretariat with robust information and data that could inform preventative action in a timely fashion.Footnote 47 The Security Council began to debate its role in prevention in the late 1990s, coinciding with broader shifts in the discursive terrain of security within that institution; at the time, Secretary-General Kofi Annan urged the international community to move ‘from a culture of reaction to a culture of prevention’.Footnote 48 The current Secretary-General, António Guterres, has similarly made conflict prevention a linchpin of his agenda. In remarks delivered on his behalf to a side event during the 2017 Commission on the Status of Women titled ‘Women, Peace and Security and Prevention’, Guterres's ‘prevention agenda’ was elaborated, envisioning cohesive action across all UN spheres of engagement; work is being undertaken to enable ‘upstream prevention efforts’, creating ‘an integrated platform for early detection and action building on a mapping of prevention capacities in the system’.Footnote 49

As noted above, the Women, Peace and Security agenda includes prevention as one of its four ‘pillars’.Footnote 50 There has, however, been relatively little attention paid to the prevention pillar in scholarship or practice. Katrina Lee-Koo, for example, has commented that ‘[t]he prevention pillar … tends to be marginalised’,Footnote 51 while Soumita Basu and I have argued elsewhere that ‘prevention is visible only “in pieces”’ rather than as a coherent and consistently well-articulated dimension of the agenda.Footnote 52 In this section, I show that prevention in WPS discourse is embedded in at least three different constellations of meaning, structured by three different logics: conflict prevention (structured in accordance with a logic of peace); the prevention of sexual violence (structured in accordance with a logic of militarism); and the prevention of ‘violent extremism’ (structured in accordance with a logic of security). Prevention thus emerges as a paradox, or impossibility: either it is configured as utopian/ideal; or it collapses into security/militarism. To show this, I examine the policy architecture of the agenda (narrowly conceived), engaging in a textual analysis of the Security Council resolutions adopted under the title of ‘Women and Peace and Security’.Footnote 53

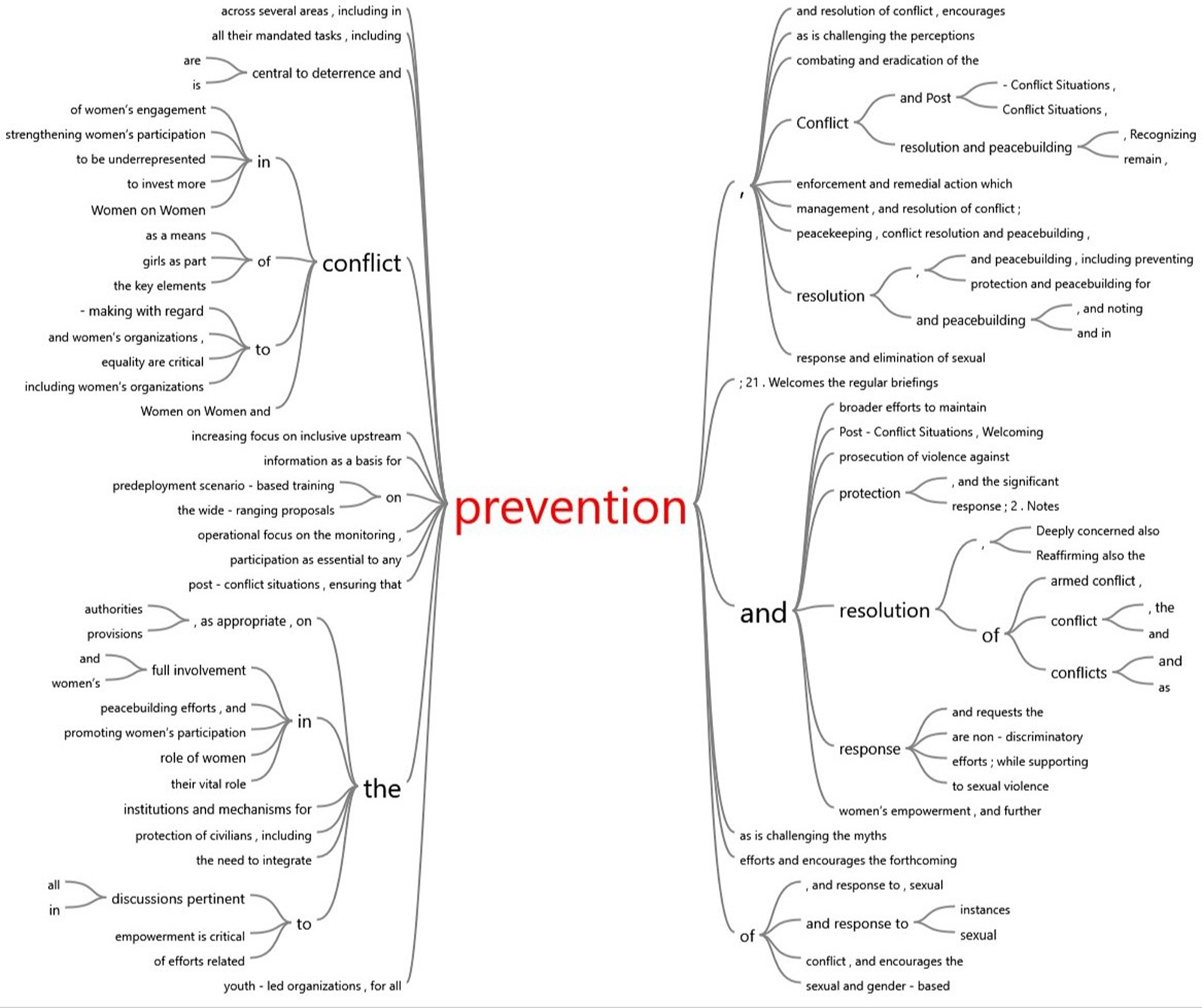

The dominant attachments of prevention across the WPS resolutions can be mapped using NVivo as shown in Figure 1. This graphic depicts the immediate context of the word ‘prevention’ in all ten of the current WPS resolutions; on the left-hand side of the image are the words that come immediately before each articulation of the word ‘prevention’, and on the right-hand side are the words that follow. The meaning of prevention is thus irreducible; its plural and oppositional logics render it a paradox.

Figure 1. Prevention in context across the WPS resolutions.

Further, I ran a simple word frequency query in NVivo to establish the number of mentions in each resolution. Stemmed words were included (represented as ‘prevent*’), meaning that the program reported all words containing ‘prevent’, such as prevent, preventing, and preventative. Figure 2 depicts the results of this query; it shows a steady increase in frequency of mentions of prevention in the resolutions, since a low point in 2009 with the adoption of UNSCR 1889.Footnote 54 Notably, though, the most recent resolution does not feature prevention prominently, despite the fact that the resolution focuses on women's participation in initiatives to create peace.Footnote 55

Figure 2. Mentions of prevent* in the WPS resolutions over time.

Conflict prevention

In UNSCR 1325, ‘prevention’ is firmly articulated with conflict: it appears three times and in each representation it is association with conflict either directly (as in the phrase ‘conflict prevention’)Footnote 56 or indirectly (as in the phrase ‘prevention, management, and resolution of conflict’.Footnote 57 This articulation is reproduced in a number of resolutions: UNSCR 1820 mentions ‘prevention and resolution’ of conflict four times,Footnote 58 for example, while the Preambular material of UNSCR 1889 reproduces the articulation of conflict prevention and conflict resolution three times.Footnote 59 Further, UNSCR 2493 relates ‘the prevention of conflict’ directly to ‘women's participation in peacebuilding efforts’ in one of the operative paragraphs.Footnote 60

Soumita Basu and Catia Confortini posit that the limited focus on prevention in practice is a function of the conflict prevention agenda being associated with the transformation of gendered structures of inequality and discrimination. In their very persuasive analysis, they argue that the linking of conflict prevention with gender equality presents three inhibitors to the development of a strong and consistent prevention pillar, rendering it an impossibility. First, the prevention agenda is hampered by the slippage between gender and women, ‘as is generally prevalent at the United Nations’,Footnote 61 as women are not taken seriously as political actors. Second, the UN system tends to overlook the work done in local prevention initiatives and, further, ‘there is little evidence of … [the WPS resolutions] being used in official mandates of the Security Council to invest in and engage with … women's groups and local actors as partners in conflict prevention’.Footnote 62 Third, and finally, Basu and Confortini suggest that the prevention element of the WPS agenda is potentially too radical a project for an organisation such as the United Nations. Because UNSCR 1325 ‘leaves the “war system” intact’,Footnote 63 full realisation of the prevention dimension of the WPS agenda ‘would require fundamental changes at the United Nations and in the global system’.Footnote 64 Associating prevention with the resolution of conflict functions to link prevention to the ‘maintenance of international peace and security’; this should create horizons of possibility around the concept of prevention that open, rather than foreclose, discussions about peace. But the logic of peace instead creates the impossibility of prevention. Further, as Figure 1 demonstrates, several attachments are not related to peace but instead constitute prevention in relation to management of conflict, peacekeeping, and sexual and gender-based violence.

The prevention of sexual violence

Prevention, when it is associated with sexual violence in conflict, is structured in accordance with a logic of militarism in the WPS resolutions. In UNSCR 1820, for example, the ‘deployment of a higher percentage of women peacekeepers or police’Footnote 65 is presented as a measure to combat conflict-related sexual violence. Resolution 1888 links prevention to sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers, noting the Council's intention to build in prevention language to peacekeeping mission mandatesFootnote 66 and the importance of combatting impunity for such violence.Footnote 67 In practice, this prevention work is associated with peacekeeping, police, and military forces. UNSCR 2122, which otherwise has prevention language strongly focused on structural change and women's participation in peacebuilding, similarly posits increasing ‘the percentage of women military and police in deployments to United Nations peacekeeping operations’Footnote 68 as an effective prevention initiative, which somewhat undermines the resolution's emphasis on women's agency: the resolution requests of the Secretary-General that they report to the Council ‘on progress in inviting women to participate, including through consultations with civil society, including women's organizations, in discussions pertinent to the prevention and resolution of conflict, the maintenance of peace and security and post-conflict peacebuilding’.Footnote 69 The value afforded to women's participation in these activities, not only through textual placement (in the second operative paragraph of the resolution) but also through the positioning of the request to the Secretary-General himself, is significant, and is reinforced later in the resolution when the Council ‘recognizes with concern that without a significant implementation shift, women and women's perspectives will continue to be underrepresented in conflict prevention, resolution, protection and peacebuilding for the foreseeable future’.Footnote 70

Leaving aside UNSCR 2242 for a moment, to which I return in the section below, it is interesting to explore the construction of prevention in one of the most recent WPS resolutions, UNSCR 2467. As shown in Figure 1, this resolution contains by far the most mentions of ‘prevent*’ in the suite of WPS resolutions adopted by the Council, which is unsurprising given its focus on sexual violence; the resolution was adopted during the April 2019 open debate at the UN Security Council on sexual violence in conflict. Almost half of these mentions are in the Preamble, which is significant because the material in the Preamble is not binding or actionable, unlike the numbered operative paragraphs, which are considered the substantive elements of each resolution. The Preambular material in resolution 2467 associates prevention with conflict as well as with sexual violence, for example noting ‘that the safety and empowerment of women and girls is important for their meaningful participation in peace processes, preventing conflicts and rebuilding societies’.Footnote 71 The operative paragraphs, on the other hand, almost exclusively link prevention with sexual violence, with one exception in paragraph 20, as noted above. This paragraph strengthens the articulation of prevention and conflict forged in the Preamble and is worth quoting in full. In this paragraph, the Security Council

Encourages concerned Member States and relevant United Nations entities to support capacity building for women-led and survivor-led organizations and build the capacity of civil society groups to enhance informal community-level protection mechanisms against sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict situations, to increase their support of women's active and meaningful engagement in peace processes to strengthen gender equality, women's empowerment and protection as a means of conflict prevention.Footnote 72

There is much of interest here in terms of the construction of prevention.

Again bearing in mind that this is the only point within the document at which prevention is articulated in the context of conflict prevention rather than the prevention of sexual violence, the resolution charges member states with building capacity within civil society as part of the governance of peace and security. Such encouragement weakens the link between the state and the provision of security, recognising that in this context (and therefore perhaps in other contexts), it might be ‘women-led and survivor-led organizations’ and ‘civil society groups’ who can create secure spaces for survivors of sexual violence and lead initiatives to prevent such violence. Further, this paragraph links the protection of women from sexual violence (and their empowerment) to conflict prevention, in fact marking out the strengthening of gender equality and women's empowerment as a prevention strategy. These representations of prevention ‘fill the gap’, per Heath-Kelly's formulations discussed above, in quite different ways than through the permission and exercise of force and sovereign power.Footnote 73

This is, however, one articulation of twenty in the resolution. The others conform broadly to the logic outlined in this section, such that prevention work is militarised. United Nations peacekeeping contingents are attributed a role in preventing sexual violence.Footnote 74 Paragraph 26 discusses the need to ‘enhance the capacity of military structures to address and prevent sexual violence related crime’,Footnote 75 and prevention is firmly anchored within the remit of the state, exhorting engagement ‘with national authorities, as appropriate, on the prevention and response to sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict situations’.Footnote 76 While, as outlined above, there are tentatively different possibilities of prevention articulated within this resolution, the dominant construction of prevention here is prevention-as-militarisation. There is another construction of prevention within the agenda, however, which emerges through a close reading of UNSCR 2242.

Preventing, and countering, terrorism and violent extremism

The background against which prevention is constructed in UNSCR 2242 is composed of the institutional context at the UN in 2015, a year in which three major, high-level, reviews of the UN peace architecture were undertaken and the dynamics of the prevention pillar of the WPS agenda explained above. Given its introduction of a different articulation of prevention – in the form of ‘preventing violent extremism’ – UNSCR 2242 caused consternation among feminist activists and scholars alike when it was adopted in 2015. Concerns were raised that efforts to prevent and counter terrorism and violent extremism would instrumentalise women, endangering their relationships within their communities, and further reinforce the idea that minoritised communities are a source of insecurity and threat. There was also a worry that, given the political salience of, and investment in, terrorism and violent extremism, resources would be diverted from other important initiatives – that terrorism and violent extremism would become the dominant form of violence deserving of international attention, in relation to WPS and more broadly.Footnote 77 There are three operative paragraphs within the resolution that invoke prevention, associating the WPS agenda with the UN's counter-terrorism and countering violent extremism initiatives and establishing a mandate for ‘the greater integration by Member States and the United Nations of their agendas on women, peace and security, counter-terrorism and countering-violent extremism which can be conducive to terrorism’.Footnote 78

Three paragraphs of UNSCR 2242 are devoted to explaining how these agendas could align better, with the following elements: an emphasis on mainstreaming gender in the operations of the Counter-Terrorism Committee (CTC) and the Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate (CTED) (United Nations Security Council); calls for better data collection in this sphere; and ‘the participation and leadership of women and women's organizations in developing strategies to counter terrorism and violent extremism which can be conducive to terrorism’.Footnote 79 It is noteworthy, however, that prevention is not actually the primary focus of the three relevant paragraphs. The primary focus of the three paragraphs of UNSCR 2242 that focus on violent extremism is on counter-terrorism and countering violent extremism (CT/CVE). It is interesting that there has been such energy around prevention and such a clear articulation of a renewed commitment to prevention and yet the operative paragraphs of the resolution that seek to link the WPS agenda with terrorism and violent extremism prioritise countering these forms of violence rather than preventing them.Footnote 80

In these paragraphs, CT/CVE is located within the domain of security and intelligence, with the UN's Counter-Terrorism Committee and the Counter-Terrorism Executive Directorate ‘to hold further consultations with women and women's organizations to help inform their work’Footnote 81 and CTED being encouraged ‘to conduct and gather gender-sensitive research and data collection on the drivers of radicalization for women’.Footnote 82 This is a fairly instrumental, extractive, vision of women's inclusion, and a model of ‘integration’ that both leaves undisturbed the politics of counter-terrorism and CVE at the UN and engages only superficially with the provisions and principles of the WPS agenda.Footnote 83 Paragraph 13 of UNSCR 2242 ‘welcomes the increasing focus on inclusive upstream prevention efforts’Footnote 84 but this is the sole mention of prevention in the three operative paragraphs that are widely considered to have prevention as their explicit focus.

Prevention thus emerges in UNSCR 2242 as a collective ‘effort’ that happens ‘upstream’ (read: chronologically prior to and simultaneously separate from the domain of peace and security) and can be ‘inclusive’, while countering threats to peace and security remains firmly within the remit of security organisations – the CTC and CTED, which Fionnuala Ní Aoláin describes as ‘male-dominated security institutions … whose interest in a robust dialogue about the definition of terrorism, the causes conducive to the production of terrorism, and the relationship between terrorism and legitimate claims for self-determination by collective groups has been virtually nil’.Footnote 85 As Pip Henty observes, the effect of having three paragraphs ostensibly related to prevention but in operation articulating a vision of security as a means to counter perceived threat is to risk (further) ‘militarising the agenda, as in many contexts CVE sits, and is associated, with the military, defence or police’.Footnote 86 In sum, prevention is constituted here in accordance with a logic of security, which is closely related to the logic of militarism discussed above. These logics could not be farther removed from the logic of peace that is subordinated in the construction of prevention in the WPS agenda.

Little security everythingsFootnote 87

This article has shown that prevention is plural, undecidable, paradoxical; it is never fully knowable and never complete. In the WPS agenda, its logics are logics of peace, militarism, and security, with militarism and security dominating even within what is widely described as a ‘peace agenda’. Though the management and achievement of security is necessarily illusory, security has an apparatus and a will to power such that it is easier to obscure its incompleteness and uncertainties while prevention cannot be thus contained. Thus, prevention submits to and is perpetuated within the techniques and rationalities of governance that is focused on ‘eliminating insecurity’Footnote 88 and not preventing violence and harm. Constituting prevention in this way creates the conditions for, and legitimacy of, militarised and securitised initiatives and efforts under the auspices of ‘prevention’ – activities which, in turn, are likely to increase peacelessness.

I have situated my analysis in the context of research on the productive power of peace and security governance, specifically research on prevention and pre-emptive security practices that draw out the logic of risk that organises prevention in the context of counter-terrorism. Through a deconstructive approach to prevention in the WPS agenda, I have attempted to show that prevention manifests as a paradox. The ‘experience’ of prevention, in Derridean terms, is the imperative to sit with it as a concept even as it is undone, unmade in its articulation in opposition to militarism/security even as it is simultaneously fixed as militarism/security through coherence of the dominant logics that structure it in discourse. What is at stake here is twofold. First, if prevention is articulated into discourse as plural and undecidable, then this requires the exploration of critical and difficult questions about what can be achieved in the name of prevention. This includes engaging seriously and consistently with the constructions of prevention in Security Council discourse and exploring the possibilities for reconstruction. While the often fraught process of negotiation at the Council might seem to mitigate against the possibility of prevention's reconstruction according to logics other than militarism/security, the very existence of the ‘Women and Peace and Security’ agenda at the Council demonstrates that it is possible to pry open spaces for engagement in even the moment conservative contexts. Clearly, a blanket prescription to reconstruct prevention will not solve all associated issues – is in fact likely to create as many issues as it addresses – but thinking about how to foster political energy around conflict prevention creates the opportunity for WPS practitioners and advocates to ‘reclaim SCR 1325 as a tool for feminist purposes and work with it harder, stronger, differently’.Footnote 89 This might include articulating conflict prevention more consistently with peacebuilding, in Security Council resolutions and beyond, or deliberately addressing the structural conditions of peacelessness. This is particularly important because second, and relatedly, if prevention as currently constituted collapses, when pressed, into militarist and security measures taken to alibi the impossibility of achieving security now and in the future, then the kind of security politics that are espoused and supported – including but not limited to those presented in our scholarly musings – take on a renewed significance.

Felicity Ruby has stated: ‘I do not think SCR 1325 has been used enough as a tool of conflict prevention.’Footnote 90 I have shown here that simply pushing forward with the prevention pillar of the WPS agenda as it is currently configured is unlikely to have positive effects in the pursuit of sustainable peace. Further, if the above analysis of prevention is persuasive, and prevention is undone in the moment of its articulation into practice such that it collapses into militarism/security, then the concept of security that is used to think with – in relation to peace, in relation to governance, in relation to the resolution of conflict and the recognition of dignity and the constitution of grievable lives – is of profound significance. As outlined above, there is a wealth of resources on which to draw in this endeavour. The WPS agenda purports to offer a transformative vision for peace, but its articulation of prevention in accordance with dominant logics of militarism and security render such transformation unlikely, if not impossible. In line with the conclusions offered by Basu and Confortini,Footnote 91 it may be that working to reconstruct prevention in the WPS agenda is a necessary precondition for enabling the transformation of the war system that feminist activists and advocates desire.

Acknowledgments

This research was enabled by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT170100037), and the University of Sydney provided additional funding towards the research programme. I am grateful to Doris Asante who worked as a research assistant on this manuscript. I would also like to acknowledge the generous and constructive comments provided by three anonymous reviewers, which, along with guidance from the editors, encouraged revisions that much improved the argument and analysis. Mistakes and omissions remain my own.

Laura J. Shepherd is an Australian Research Council Future Fellow and Professor of International Relations at the University of Sydney and a Visiting Senior Fellow at the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security. Her primary research focuses on the United Nations Security Council's Women, Peace and Security agenda, and she also has strong interests in pedagogy and popular culture. She is author/editor of several books, including, most recently, Gender, UN Peacebuilding and the Politics of Space (Oxford University Press, 2017) and Handbook of Gender & Violence (Edward Elgar, 2019). She tweets from @drljshepherd and blogs semi-regularly for The Disorder of Things.