Introduction

Social science has endeavored to explain the occurrence and intensity of episodes of genocide and mass killing through a growing range of analytic approaches. From an initial generalized and broad engagement with the subject (Harff and Gurr Reference Harff and Gurr1988; Horowitz Reference Horowitz1997; Kuper Reference Kuper1981), areas of analytic focus now include macrolevel political, institutional, and economic forces (Fein Reference Fein1993a; Harff Reference Harff2003; Krain Reference Krain1997; Mann Reference Mann2005), elite decision-making processes (Gagnon Reference Gagnon2004; Midlarsky Reference Midlarsky2005; Valentino Reference Valentino2004), nonelite perpetrator motivation and participation (Hinton Reference Hinton2005; Mann Reference Mann2000), and the dissemination of collective scripts or frames for violent action (Fujii Reference Fujii2004; Oberschall Reference Oberschall2000; Straus Reference Straus2007). In addition, a more recent body of research demonstrates that local and temporal variation in violence during genocides is associated with distinct meso-level determinants (Fujii Reference Fujii2008, Reference Fujii2009; Hagan and Rymond-Richmond Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2008; Kopstein and Wittenberg Reference Kopstein and Wittenberg2011; Straus Reference Straus2006; Su Reference Su2011; Verwimp Reference Verwimp2003, Reference Verwimp2004, Reference Verwimp2005). These recent works support Bartov's (Reference Bartov, Gellately and Kiernan2003: 86) contention that “we cannot understand certain central aspects of modern genocide without closely examining the local circumstances in which it occurs” (see also King Reference King2004).

Despite the promise of this emerging empirical focus, analytic challenges remain. Researchers generally conceptualize genocides as the product of interactions between a variety of factors that are rarely sufficient on their own (Fein Reference Fein1993b; Tilly Reference Tilly2003: 103–10). However, most studies either focus on the direct effects of these factors, or privilege one or two explanatory factors and marginalize others. As a result, the specific ways in which multiple explanatory factors interact in specific meso-level contexts remains to be accounted for empirically.

In order to address this shortcoming, this study presents a fuzzy set analysis (Ragin Reference Ragin2000, Reference Fujii2008) of local and temporal variation in the emergence of violence during the Cambodian genocide. I focus on how changing combinations of cognitive and relational mechanisms created distinct patterns of violence. To address changes in local conditions over time, I utilize a sample of twenty-four historical accounts from survivors of the genocide. Results indicate that while the increasing coercive capacity of the central state was the primary vector of increasing violence, consistent with historical scholarship, variation in victimization for different social groups was mediated by changes in official crisis framing, intergroup polarization and dehumanization, and quotidian disruption. These findings confirm and extend the insights of other meso-level studies of genocide, and demonstrate the utility of comparative configurational methods in the study of its emergence.

The Rule of the Khmer Rouge, 1975–1979

On April 17, 1975 after roughly five years of civil war in Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge army seized the capital city of Phnom Penh. Its victory would usher in one of the most violent and extremist regimes of the twentieth century: Pol Pot's Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK). The CPK sought to rapidly reshape Cambodia, now renamed Democratic Kampuchea, into the purest manifestation of agrarian socialism in the world. Instead, over the next four years Democratic Kampuchea became an indentured agrarian “prison camp state” (Kiernan Reference Kiernan2002: 9). By its overthrow by a Vietnamese invasion in January 1979, demographic scholars estimate that between one and three million people had died from starvation, lack of medicine, and violence (De Walque Reference De Walque2005; Heuveline Reference Heuveline1998, Reference Harff, Alker, Gurr and Rupesinghe2001). Notably, Heuveline (Reference Heuveline1998) finds that at least six hundred thousand deaths, and perhaps as many as 1.1 million, are directly attributable to physical violence (i.e., executions; see also Etcheson Reference Etcheson2005: 118–19).

In order to best summarize the overall historical dynamics of the regime, I periodize its history into three sections.Table 1 presents a summary of these periods across three aspects: state-institutional dynamics, local-situational dynamics, and the general dynamics of victimization.

TABLE 1. Historical periodization of CPK rule

Throughout its rule, the CPK regime “combined highly centralized control and what often appears to be an unchanging character with complex regional and temporal variations” (Chandler Reference Chandler1991: 265; Vickery Reference Vickery1984). During the civil war, the CPK was a loosely bound coalition of different political factions, many with stronger ties to Vietnamese communism than to the CPK's extremist central committee, secretly led by Pol Pot (Chanda Reference Chanda1986; Etcheson Reference Etcheson1984; Kiernan Reference Kiernan2004). After the war, administration of the country's different regions was delegated to various autonomous local officials. While some regional administrations were closely connected with Pol Pot and the CPK center (Kiernan Reference Kiernan2002: 169; Vickery Reference Vickery1984: 93), others were overseen by officials whose connections to the party center were quite tenuous (Becker Reference Becker1998: 176–81). However, in March and April 1976, Pol Pot and the CPK center began to take increasingly violent repressive measures to eliminate officials seen as moderate or disobedient and consolidate centralized political control. By 1978, internecine violence had engulfed the party, and the CPK's revolution disintegrated into a quagmire of repressive violence. The spread of violence across different regions was thus largely defined by the “CPK center's unceasing, and increasingly successful, struggle for top-down domination” (Kiernan Reference Kiernan2002: 26).

Central to the organization of violence in Cambodia was the categorization of the population into two “class” groups (Becker Reference Becker1998: 226–29). Those categorized as “New People” were seen as contaminated by foreign capitalist influence, and were predominantly deported into the countryside from urban areas, but also included numerous non-Khmer minorities (in particular the Vietnamese and Cham; see Kiernan Reference Kiernan2002). Rural peasants seen as uncontaminated by foreign influence were categorized as “Base People,” who would serve as the raw human materials for the CPK's social revolution (Mann Reference Mann2005: 343; Valentino Reference Valentino2004: 138–39). While these categories exploited urban-rural tensions nurtured during Cambodia's civil war (Kiernan Reference Kiernan2002: 16–25), they also reflected the CPK's peculiar notion of “class.” For the CPK, class was the manifestation of an essentialist “organic purity” (Straus Reference Straus2001) that could be observed, and thus changed, through an individual's actions (Kiernan Reference Kiernan, MacKerras and Knight1985). For instance, if a Base peasant committed a minor infraction such as breaking a farming tool, they might be redesignated as a “class traitor” for their act of “sabotage.” The CPK also subsumed ethnic, national, and religious differences within this organic notion of class (Becker Reference Becker1998: 242–43; Heder Reference Heder, Kimenyi and Scott2001), with non-Khmer minorities such as the Vietnamese and Cham identified as particularly prone to class treachery (Kiernan Reference Kiernan2002). Such volatile and shifting means through which the CPK identified its purported “enemies” eventually contributed to high levels of victimization for both New and Base.Footnote 1

This victimization has been variously defined as a genocide for the CPK's targeting of ethnic minorities (e.g., Kiernan Reference Kiernan2002; United Nations 1948), as a “politicide” for its targeting of “class” groups (e.g., Harff Reference Harff2003), and as an “auto-genocide” to characterize Khmer-on-Khmer mass violence (e.g., Melson Reference Melson1992; Subcommission 1979). Rather than qualify different types of violence as separate phenomena, I argue for a conceptual broadening of genocide as a term. One element that distinguishes genocide from other violence is that victims are targeted for elimination en masse because of their real or purported membership in some collectivity, as that collectivity is defined by perpetrators (Chalk and Jonassohn Reference Chalk and Jonassohn1990: 23–26). The group-based nature of elimination is what is essential, not the specific content of a collectivity's “groupness” (Fein Reference Fein1993b: 23–24; Owens et al. Reference Owens, Su and Snow2013). Furthermore, state-sponsored annihilation can be just as easily directed against groups constructed out of revolutionary ideologies as those based on preexisting categories (Conquest Reference Conquest1986; Harff Reference Harff2003; Su Reference Su2011). In Cambodia, “class” served as the dominant “contrast conception” (Shibutani Reference Shibutani and Shibutani1973) through which the CPK identified its purported adversaries, subsuming various national, ethnic, and religious boundaries. Thus, in this study I use “genocidal violence” to refer to sustained and purposeful physical violence to eliminate individuals on the basis of their purported “class” membership, as that membership was contemporaneously defined by perpetrators.

Previous social scientific research on violence in Cambodia focuses on the cultural and psychological logics of participation (Hinton Reference Hinton2005). Here I leverage the historical insights mentioned in the preceding text to explore a different empirical question: uneven temporal and geographic distribution of violent victimization among Base and New “class” groups. While the spreading coercive capacity of the central CPK seems to account for a generalized increase in violence across the country, does it explain its uneven application against two seemingly polarized groups? Why did the CPK's revolution eventually victimize both friend and foe?

Explaining Genocidal Violence

The study of genocide and mass killing in the social sciences is increasingly moving toward an engagement with a diversity of underlying, contributing processes that occur at multiple levels of analysis. Early works focused on broad and generalized societal types (Harff and Gurr Reference Harff and Gurr1988; Horowitz Reference Horowitz1997; Kuper Reference Kuper1981). More recently, tests of state-level hypotheses find that episodes of genocide and mass killing are strongly associated with social upheaval and warfare, autocratic regimes, preexisting social divisions, exclusionary ideology, and economic marginalization (Fein Reference Fein1993a; Harff Reference Harff2003; Krain Reference Krain1997). Supplementing these findings, other works suggest that mass violence can occur along multiple and contingent trajectories of state development (Mann Reference Mann2005) and conflict escalation (Harff Reference Harff, Davies and Gurr1998, Reference Harff, Alker, Gurr and Rupesinghe2001). Likewise, studies of elite decision-making processes emphasize the escalation and radicalization of violent policies over time (Gagnon Reference Gagnon2004; Midlarsky Reference Midlarsky2005; Valentino Reference Valentino2004; see also Mann Reference Mann2005). Studies of nonelite perpetrators and supporters focus variously on the role of ideological and institutional incentives (Mann Reference Mann2000), social-psychological dynamics and group pressures (Kelman and Hamilton Reference Kelman and Hamilton1989; Waller Reference Waller2007), and how violence becomes actionable as either collective frames or cultural scripts (Fujii Reference Fujii2004; Hinton Reference Hinton2005; Oberschall Reference Oberschall2000; Straus Reference Straus2007). In addition, an emerging body of meso-level research focuses on variation in local and regional environments, and their effects on individual and collective participation (Fujii Reference Fujii2008, Reference Fujii2009; Hagan and Rymond-Richmond Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2008; Kopstein and Wittenberg Reference Kopstein and Wittenberg2011; Straus Reference Straus2006; Su Reference Su2011; Verwimp Reference Verwimp2003, Reference Verwimp2004, Reference Verwimp2005). This focus on local and regional factors addresses itself to the important question of how meso-level mechanisms can mediate the effects of larger state and institutional processes (Tilly Reference Tilly2003: 20–22).

While the development of this meso-level emphasis is promising, significant analytic challenges remain. Current research has yet to empirically specify ways in which multiple theoretical factors interact and combine in specific meso-level contexts, and how such concatenation is linked to the variable emergence of violence. As Cress and Snow (Reference Cress and Snow2000: 1070) note, the explanatory strength of individual factors “does not reside solely in the strength of their association with a particular outcome, but in the more complex ways they interact with each other.” To address this lacuna, this study draws from Tilly's (Reference Tilly2003: 20) theoretical emphasis on how “recurrent small-scale mechanisms” can “combine variously to generate very different outcomes.” I focus on two types of mechanisms: cognitive mechanisms, which “operate through alterations of individual and collective perceptions”; and relational mechanisms, which “change connections among social units” (Tilly Reference Tilly2003: 20–21). In identifying these collective mechanisms, I balance attention to insights from the genocide and collective action literatures with an examination of historically specific social processes (Bradshaw and Wallace Reference Bradshaw, Wallace and Ragin1991; Walton Reference Walton, Ragin and Becker1992).

Moral Distancing

Moral distancing is derived from Fein's (Reference Fein1979, Reference Fein1993b) contention that for a group to become a target of genocidal violence, its members must first be excluded from the “universe of moral obligation” (see also Gamson Reference Gamson1995; Kelman and Hamilton Reference Kelman and Hamilton1989; Waller Reference Waller2007: 201–12). Such exclusion generally involves the creation and/or activation of “us-them” social boundaries and the subsequent widening of political and social space between groups. Through this exclusion, moral impediments against violence and mistreatment are removed, and perpetrators are absolved from moral responsibility for their actions.

Political Coercive Capacity

This measure is derived from arguments that the emergence of mass violence is determined by the situational capacity of dominant institutions to instigate and coordinate violent participation. State and military institutions are often the primary enablers and orchestrators of genocidal events (Fein Reference Fein1993b), and provide uniquely coercive means through which to mobilize potential perpetrators (Kelman and Hamilton Reference Kelman and Hamilton1989). However, coercion is not just physical: dominant institutions channel behavior through their consolidation as ideological structures (Abrams Reference Abrams1988), creating durable patterns of political behavior (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1994). Thus, it follows that participation may also be coerced through the official routinization and legitimation of violence, and the channeling of moral responsibility away from individual perpetrators (Kelman and Hamilton Reference Kelman and Hamilton1989; Waller Reference Waller2007: 247–50). Because processes of cognition and meaning making are inextricably bound to the coercive capacity of state and other institutions, we should expect a high degree of interactivity between this capacity and the specific claims-making activities of such institutions, potentially influencing both the form and directionality of violence (e.g., Straus Reference Straus2006).

Crisis Framing

Frames are cognitive and social structures that situate and connect events, individuals, and groups into a meaningful and interpretable narrative (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Rocheford, Worden and Benford1986). Collective action frames focus attention on situations considered problematic, suggest lines of action to address them, and provide motivational rationales for action through their diagnostic, prognostic, and motivational attributes (Snow and Benford Reference Snow and Benford1988). Frames also construct, maintain, and transform group “identity fields” through the imputation of characteristics to relevant sets of actors (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Benford, Snow, Larana, Johnson and Gusfield1994). Here I use Oberschall's (Reference Oberschall2000) concept of a “crisis frame” to describe collective framing processes that alter the salience and content of intergroup boundaries through the construction of a zero-sum conflict between two or more groups. Crisis frames bring dormant in-group fears of domination by an out-group to the surface in order to mobilize violent retributive action against them, creating a “kill or be killed” dynamic (Oberschall Reference Oberschall2000; Straus Reference Straus2006). When such conflicts are officially framed as a “war,” they have the additional effect of removing social and legal sanctions against violence (Straus Reference Straus2006; Su Reference Su2011). Crisis frames may draw from or heighten the salience of preexisting group boundaries, but can also develop radically new boundaries (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Benford, Snow, Larana, Johnson and Gusfield1994).

Systemic Disruption

Systemic disruption draws from the “quotidian disruption” and “breakdown” concepts employed by collective action scholars (Buechler Reference Buechler, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004; Snow et al. Reference Snow, Cress, Downey and Jones1998). The measure refers to the degree to which both the material and social routines of a particular locale are thrown into disarray, introducing new sources of grievances and potential for genocidal mobilization. The concept of “quotidian” is rooted in the “specious present” where “doubts, uncertainties, and inhibitions are not at the forefront of consciousness, and action is largely habituated and routinized” (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Cress, Downey and Jones1998: 5). Collective experiences of disruption create a “problematic present,” where routine action is stymied, and uncertainties emerge. Such disruptions include events that “throw a community's routines into doubt and/or threaten a community's existence,” disrupt “the immediate protective environment,” and create “dramatic alterations in subsistence routines” or “dramatic changes in existing structures of social organization and control” (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Cress, Downey and Jones1998: 6, 9, 14). I contend that within a revolutionary authoritarian milieu such as Democratic Kampuchea, severe quotidian disruptions may eliminate perpetrators’ “suspension of doubt” (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Cress, Downey and Jones1998) regarding victim groups. As such, this measure provides an extension of findings that large-scale political or economic disruptions may act as “triggers” or “accelerators,” changing the course of conflicts in the presence of facilitative conditions (Ahmed and Kassinis Reference Ahmed, Kassinis, Davies and Gurr1998; Fein Reference Fein1993a; Harff Reference Harff, Davies and Gurr1998, Reference Harff, Alker, Gurr and Rupesinghe2001, Reference Harff2003; Krain Reference Krain1997).

Data and Method

For my analysis I utilize twenty-four open-ended interviews with survivors of the Cambodian genocide, conducted by historian Ben Kiernan in 1979 and 1980 in Cambodia, Thailand, and France. This sample of twenty-four is drawn from roughly five hundred interviews conducted by Kiernan. The five hundred interviews, and thus my subset of them, are not representative in a statistical sense. However, Kiernan's data represent the most comprehensive existing collection of survivor accounts on the genocide, drawing from both rural and urban sources. The interviews are not publicly available at this time, so I contacted Kiernan to see if he would be willing to share a sample of the interviews with me. He agreed and assembled a subset of twenty-six interview transcripts. After close reading, I determined that twenty transcripts matched my selection criteria of accounts that presented a consistent local or regional picture of conditions throughout the entire period: 1975–79. Six accounts that did not meet these criteria were dropped from the analysis. These accounts were supplemented by four additional interviews published in a separate text (Kiernan and Boua Reference Kiernan and Boua1982: 338–62), which were selected using the same criteria of consistent local accounts that covered the entire period. This yielded a final sample of twenty-four accounts.

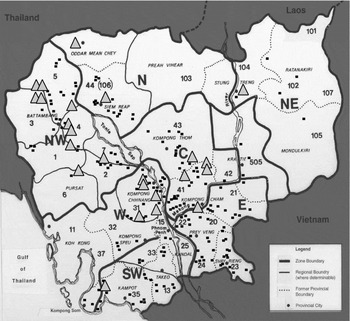

Because the selection process was nonrandom, there exists the possibility of sample bias, which I assess in the following text by examining the geographic and demographic characteristics of the sample. The geographic distribution of the twenty-four informants across the country is presented in figure 1.Footnote 2 Although representation is low in the eastern, southwestern, and northeastern areas, the locations of the informants are relatively consistent with the agriculturally productive central regions that the Khmer Rouge pushed much of the population into during its rule. These locations also match fairly well with the best available regional indicators of violence, specifically the locations of mass graves uncovered by investigators.Footnote 3

FIGURE 1. Geographic representation of informant sample

Additional Key:

![]() Informant Location

Informant Location

![]() Mass Burial Site

Mass Burial Site

Table 2 presents a summary of descriptive characteristics of the sample. It is extremely difficult to obtain reliable population data for Cambodia during this period (Heuveline Reference Heuveline1998, Reference Harff, Alker, Gurr and Rupesinghe2001). Because the 1962 Cambodian census data presented in Migozzi (Reference Migozzi1973) contains the most reliable data available prior to the genocide, I refer to them for purposes of comparison. Migozzi does not provide data on the racial and ethnic composition of the population. The best alternative source for ethnic and racial composition data are Kiernan's (Reference Kiernan2002: 458) estimates; I also use Kiernan's estimates of the Base and New populations for 1975. In comparing the sample with these estimates, several differences are notable. The sample underrepresents women by almost 13 percent relative to the 1962 population. Because men were disproportionately victims of mortality (Heuveline Reference Heuveline1998), the expected bias would be female overrepresentation. This disproportionate targeting of men could mean that male and female accounts will have important differences with regard to the reported level of violence.Footnote 4 The Cham minority is somewhat overrepresented in the sample, consistent with Kiernan's effort to capture the experiences of minority ethnic groups. Because Cham communities were specifically targeted by the state for violent repression relatively early in the regime's history, this may slightly overestimate violence levels against the New class in Periods I and II, because Cham were predominantly classified as New (Kiernan Reference Kiernan2002). By adjusting standard errors for intragroup correlations (Longest and Vaisey Reference Longest and Vaisey2008), you can control for such group-based differences. About a third of informants did not provide information on their previous occupations, but because prior occupation was largely determinative of what class designation would be given to an individual, this shortcoming is largely corrected for by the relatively even split in the Khmer Rouge class designation data.

TABLE 2. Characteristics of informant sample (N = 24)

Note: Blank cells indicate that demographic data is unavailable. All population estimates are based upon census data for pregenocide Cambodia (Migozzi Reference Migozzi1973) except: aestimates based upon demographic estimates for postgenocide Cambodia (Kiernan Reference Kiernan2002: 458).

Coding the accounts began with a preliminary line-by-line or “open” coding, commonly employed in grounded theoretical approaches (Charmaz Reference Charmaz2006). As the coding became more elaborated, I drew from relevant concepts such as moral disengagement (Fein Reference Fein1993b; Kelman and Hamilton Reference Kelman and Hamilton1989; Waller Reference Waller2007), collective action framing (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Rocheford, Worden and Benford1986), and symbolic coercion (Abrams Reference Abrams1988; Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1994) to orient my exploration of the data. Over time, I connected and refined these orienting concepts with elaborated codes through an iterative verification process (Ragin Reference Ragin1994). Despite the open-ended nature of each account and the relative invisibility of the interviewer in the transcripts,Footnote 5 consistent patterns of speech did appear throughout the interviews relating to the local conditions and events. My preliminary line-by-line coding was largely an effort to isolate these patterns and compare their prevalence across the sample. This does hold out the possibility that the failure to mention a particular mechanism in an account will be coded as the absence of the mechanism, and may be a source of potential bias in the accounts. However, because the patterns of speech that became operationalized were highly consistent throughout my final sample, I was able to infer that consistent lines of questioning on certain core topics and processes were likely to have been used with all informants.

To assess how independent measures interacted and combined to create changing dynamics of violence, I utilize the technique of fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (Ragin Reference Ragin2000, Reference Ragin2008) through the Stata “Fuzzy” command (Longest and Vaisey Reference Longest and Vaisey2008). Qualitative-comparative analysis (QCA) is based on the conjunctural logic of set relations, which allows that multiple “pathways” leading to an outcome may exist, as opposed to the linear and additive assumptions of correlation (Ragin Reference Ragin1987). Set relation analysis in QCA compares the relative presence of independent measures and dependent outcomes across different cases, seeing how these measures interact and combine to produce similar outcomes. Because such relationships are often asymmetric and complex, the logic of set analysis reflects the multifaceted nature of many social processes. Factors that may not be sufficient on their own to produce a particular outcome might still be necessary for that outcome to occur; in such cases, all that is needed is the presence of some additional configuration of factors to generate the expected outcome. This makes the method extremely useful in assessing complex patterns of interaction between independent factors and outcomes, particularly in analyses of small-N data (for elaboration, see Ragin Reference Ragin1987: 10–16).

The addition of fuzzy set membership into QCA allows for fine-grained assessment of independent factors and outcomes by allowing for different degrees of membership in a particular set, rather than the dichotomous present or not present distinctions of “crisp” QCA (Ragin Reference Ragin2000, Reference Ragin2008). Crisp QCA set membership is coded either as 1 (present) or 0 (not present), but fuzzy set membership can be coded anywhere between 1 and 0. In cases such as the present one, being able to distinguish between a stronger or weaker presence of independent measures and outcomes, rather than simply their presence or nonpresence, is extremely useful for a more detailed analysis of social dynamics.

Operationalization of Independent Measures and Outcomes

All independent measures are focused on local-level mechanisms that encouraged or facilitated violent participation on the part of Khmer Rouge soldiers and officials. Violence during the genocide was predominantly carried out by armed soldiers, who were under the charge of local CPK cadres; thus, the military and political-administrative aspects of the CPK were the only observable institutional entities present in the interviews. All measures are coded on a five-point fuzzy-set scale. Both independent and outcome measures are assigned a single letter for representation in the analysis. For specific coding guidelines and examples, see Appendix Tables A1–A4.

Moral distancing (M) refers to the degree to which the Base and New populations were subjected to different “class”-based polarization regimes by soldiers and administrative officials within a given local context. Distancing was commonly manifested through physical separation between Base and New, but also includes the degree to which privileges, food, and work assignments were distributed unequally according to status. Political coercive capacity (T) refers to the degree to which the local administrative and military structure of a particular locale was penetrated by extremist elements of the central CPK. This manifested itself in the accounts primarily through forcible changes in the administrative leadership of a village, moving from relatively decentralized regional and local governance to eventual consolidation and domination by agents of the central CPK. The presence of crisis framing (R) was assessed by noting whether or not the informant observed the invocation of a crisis frame (Oberschall Reference Oberschall2000) by a local administrative official or soldier in their particular locale. Because political “education” sessions were mandatory in many villages, most informants were regularly exposed to revolutionary rhetoric and slogans by local officials and soldiers. These “educational” sessions often acted as a political barometer for a village, and were used to draw public attention to new “threats” to the revolution. Crisis frames were coded on the degree to which these threats were located as specifically internal to the village population, as opposed to vague external sources of threat. Some informants also overheard conversations of officials and soldiers where such frames were invoked. The presence of systemic disruption (D) was assessed by noting whether or not there was some event that threatened a community's existence, dramatically altered subsistence routines, or dramatically changed local structures of social organization and control.

Class-based violence (X), as the outcome of interest, is split between the New and Base groups in order to track changes in the directionality of victimization. Levels of violence are coded 0 for no violence, 0.25 for sporadic, low levels of violence (e.g., 1–10 individual killings per year), 0.5 for consistent, low levels of violence (e.g., more than 10 individual killings per year), 0.75 for sporadic killings of large groups (e.g., 1–3 killings of groups of 11 or more, per year), and 1 for consistent killings of large groups (4 or more killings of groups of 11 or more, per year). Because violence was not equally present at all times and places in Cambodia, and the two “class” groups were not always targeted with equal force, it is also important to analytically account for low levels of violence. Low class-based violence is assessed through the creation of a separate fuzzy set for low violence (x) out of the high violence fuzzy set (X) using the following calculation: x = 1 – X. Thus, using the principles of fuzzy set membership, a case with a high level of membership in the high violence set (i.e., 0.95) would have a correspondingly low level of membership (i.e., 0.05) in the low violence set.

Throughout the coding process, almost all informants tended to reference time periods in some fashion when describing their experiences, generally with reference to a particular time of year (e.g., early 1976, late 1978), if not a specific month and year (e.g., October 1978). It thus became clear that interrogating the interviews on the basis of temporal dynamics was empirically valid. Drawing from this insight, the fuzzy-set model is divided into the three historical periods noted in table 1, with all independent and outcome measures coded separately for each time period. Because not all accounts were equally specific in their references to time, the duration of each period is broad, so that all temporally referential information could be included. As a result, the final analysis contains four analytic models for each time period: two models for each class group, one for high violence outcomes, and one for low violence outcomes. This yields a total analytic framework of twelve models. The unit of analysis for each model is the population of an informant's local community within a given historical period.

Results

The results of the fuzzy set analysis of the twelve analytic models are presented in tables 3–5. The significance of a solution's set membership coefficient in the positive (Y) versus negative (1 ‒ Y) outcome sets is determined using Wald's F-test, and standard errors are adjusted for intragroup correlations by gender. The solutions in tables 3 and 4 are logical reductions of the significant solutions for each period.Footnote 6 All empirically represented solutions are shown in table 5. The asterisk in between each letter denotes logical “and,” meaning that the formula shown is a specific combination of conditions that are linked with their respective outcome. Lowercase letters denote a low level of set membership (< 0.5), and uppercase denote a high level of set membership (> 0.5). Sections with no result (—) indicate that there was no sufficient set of conditions to account for the outcome. The coverage and consistencyFootnote 7 of the reduced solutions are displayed, respectively, below each solution in tables 3 and 4.

TABLE 3. Fuzzy set results on the presence of moral distancing (M), political coercive capacity (T), crisis framing (R), and systemic disruption (D) in low violence outcomes (x)

Note: Coverage and consistency scores are shown, respectively, in parentheses below each solution.

TABLE 4. Fuzzy set results on the presence of moral distancing (M), political coercive capacity (T), crisis framing (R), and systemic disruption (D) in high violence outcomes (X)

Note: Coverage and consistency scores are shown, respectively, in parentheses below each solution.

TABLE 5. Empirical solutions by historical period and victimized group

Note: High violence outcomes are indicated by (X); low violence outcomes are indicated by (x).

** p < .01; * p < .05; *** p < .10

In Period I a combination of low levels of all independent factors (m*t*r*d) was perfectly consistent with low violence levels against the New. In contrast, low levels of class-based distancing and coercive capacity do not play a central role in low Base violence, which was constituted through either inconsistent levels of distancing and low levels of all other factors, or high distancing with inconsistent state power, low disruption, and low crisis framing (r*d*[t+M], where “+” is logical “or”). Period II's results depict a growing schism in violence dynamics between the New and Base. Rising levels of violence against the New are associated with an increase in both moral distancing and political coercive capacity. However, this increase in New violence is not linked to an increase in the presence of crisis framing or systemic disruption. In contrast, violence directed against the Base in Period II generally remained low, and was associated with fluctuating levels of most measures (r*[T*D + M*d]). Period III's results reflect the maelstrom of repression and violence that defined the final years of the CPK. While both high and low levels of moral distancing are associated with high violence against the New class (T*R*[m+D]), declining class polarization is specifically associated with increasing violence against the Base (m*T*R*D). High levels of political coercive capacity and systemic disruption were constitutive of violence against both groups, but disruption figures more centrally in Base violence. Increasingly salient official crisis frames form the primary distinction between low Base violence in Period II and high Base violence in Period III.

For both the Base and New, the conditions that led to changing levels of violence were highly conjunctural, with no single factor acting alone in constituting either high or low levels of violence. I will now explore the specific ways in which the four independent mechanisms interacted and combined with each other to produce changing local patterns of violence, using excerpts and insights from the informant accounts to illustrate these processes.

New Victimization

Despite the significant violence that accompanied the Khmer Rouge's forced urban evacuations and population transfers in 1975, many survivors’ early experiences in the countryside gave few indications of the massive violence to come. So Davinn, who prior to April 1975 studied medicine at Phnom Penh University, reports that after being forcibly evacuated from Phnom Penh in 1975, village life under the Khmer Rouge was initially “not so hard.” City evacuees often received equal treatment with local peasants, and Davinn adds that “we had freedom. If we needed something, we just let the Khmer Rouge know.” At this time, many villages were still being administered by officials and soldiers who had little knowledge of the central CPK's extremist agenda.

As the CPK began its campaign to expand control over local administrations in March 1976, class-based polarization regimes became increasingly prominent, and violence against the New increased. This distancing was sufficient to constitute New victimization in the context of increasing political coercive capacity, as illustrated in the account of Hong Var (Kiernan and Boua Reference Kiernan and Boua1982: 338–44). Var tells that most of the people in their village were evacuees from Phnom Penh. Discipline was very harsh: “people who were caught simply complaining were executed; if a person accidentally broke a plowshare while working in the fields, he would be accused of being negligent with the property of Angkar and would be shot.” However, Var notes that “it was considerably worse for the Phnom Penh people. . . than for the local peasants.” Mistakes made by the city people would lead to their certain execution, while the same offense by a peasant would often be overlooked.

Intergroup polarization was enabled, and became sufficient to constitute increasing violence, through the increasingly coercive presence of extremist CPK leaders in local administrative institutions. Consistent with historical scholarship, political coercive capacity remains the focal situational factor that pushed violence from relatively sporadic levels (the exemplary executions of soldiers and officials noted by many survivors) in Period I to truly genocidal proportions (mass executions) in Periods II and III. For instance, So Davinn recounts that violent victimization increased only after their village was taken over by extremist CPK forces early in 1978, when a new group of cadres arrived from the Southwest Zone of Kampuchea. These new officials arrested all the cadres who had been in place since 1975, accusing them of being “agents of the enemy Vietnamese.” They then began a series of “large-scale” executions, targeting mostly men, some of whom were arrested apparently without having committed any infraction at all. Many other New accounts depict a similar dynamic: at some point in Periods II or III, local administrations were replaced, often violently, with new extremist leaders who began campaigns of violence and intimidation against the local populace.

Official crisis framing also tended to exacerbate violence against the New. These frames often characterized internal dissent as a spreading “sickness” within the country, or linked internal dissent with foreign threats to CPK sovereignty. However, in areas where strong polarization regimes remained in place, violence tended to remain focused on the New and did not target the Base. Sah Roh's experiences exemplify this trend. Talo village, where she was located, was a “pure Khmer Rouge base” where the local cadres and peasants had always worked together. As soon as the urban evacuees arrived in 1975, they were forced to give up all personal property, and had to submit to biographical examinations of their pasts. In 1978, the local cooperative chief was replaced by several cadres from the Western Zone, who then began a series of large executions. At this time, around three thousand evacuees from the Eastern ZoneFootnote 8 arrived in the village. At a work meeting, the new cadres told villagers that these evacuees were “sick” and had to be “cleaned up completely.” The evacuees started to be executed, sometimes as many as five hundred in one day, and Roh tells that none were spared, “not even small children.” Before the arrival of the Eastern Zone evacuees, only “state officials, teachers, police, soldiers” were killed, but after their arrival Roh overheard that “all the ‘4/17 [New] people’ would not be spared – all were to be killed.” Larger executions of New people began, including the wives and children of officials and soldiers who had been previously killed.

We should note here both the presence of an official crisis frame linking dissent with a spreading “sickness,” exemplified by the arrival of Eastern Zone deportees, and the massive disruption that the arrival of these deportees caused, effectively doubling the village's population. However, the spread of violence is not linked in Roh's account with a decline in social polarization between the Base and New. Rather, a thick boundary was maintained between the two groups. In areas where local polarization regimes endured, violence remained focused against the “enemies” of the regime: the New. This demonstrates that, even in the presence of strong crisis frames, social polarization acted as a key mediating factor in determining the directionality of violence. In areas where moral distancing declined in Period III, however, violence against both Base and New became much more likely.

Base Victimization

The increasing presences of moral distancing and political coercive capacity in Period II, which contributed to increasing levels of New victimization, were associated with low levels of Base violence. By and large, the Base remained the nominal allies of the Khmer Rouge, and local officials had no incentive to target them. Hong Var tells that “the peasants in [the village] really liked the Khmer Rouge. . . [they] had high hopes for the revolution as far as their living standards were concerned.” Local Base populations were often given considerable control over the New by local officials: as Yon Sau recounts, in his village “Base groups were put in charge of the New by local cadres, and supervised their work teams.” Srey Pich Chnay, a former art student at Phnom Penh University, recalls a Base peasant saying to him: “You used to be happy and prosperous. Now it's our turn” (Kiernan and Boua Reference Kiernan and Boua1982: 346).

However, the Khmer Rouge quickly lost Base support in many areas during later periods, as local working and eating conditions became increasingly harsh and the Base lost many of their earlier privileges. As Tae Hui Lang recalls:

Towards the end of 1976, the local leaders of the Khmer Rouge were replaced, including a number of people who had once been schoolteachers. They were accused of being “traitors” and disappeared. From the end of 1976, the [Base] people and the urban dwellers began to be treated equally. From then on, everyone received the same low ration of food, and the [Base] people became very hostile to the Khmer Rouge. (Kiernan and Boua Reference Kiernan and Boua1982: 361)

But violence against the Base remained predominantly low in Period II when there was no invocation of an official crisis frame, even in areas where Base people became increasingly restive. Long Nem's account is illustrative: in their village, the confidence of the Base population in the revolution was shaken by executions of soldiers and teachers in 1976, growing food difficulties, and doubt in revolutionary rhetoric. By early 1977, “few Base people believed in the revolution.” This eventually manifested in a small, localized rebellion. Although Nem's account does not go into great detail regarding this rebellion, the “action failed” and the fifteen Base people involved were executed. Although those responsible for the uprising were executed, there was no official framing of a generalized internal threat, and no further violence was targeted against the Base. Rather, threats remained outside the village, in the form of “Vietnamese aggression.”

However, Base violence levels sharply increased in Period III. Here the accounts indicate important interconnections between declining levels of intergroup polarization, the consolidation of CPK coercive capacity, and an increase in official crisis framing by new CPK officials. This is illustrated in the account of Som Sarouen, who says that the “most terrifying years” were 1977 and 1978, in which the village was taken over by extremist CPK forces from the Southwestern Zone. The Southwestern Zone forces arrested and replaced everyone in the village administrative network. Under the old village administration there had only been targeted killings of New people identified as soldiers, but the Southwest Zone troops began to arbitrarily kill “truckloads” of people, both New and Base, particularly targeting the Cham minority, of whom Sarouen says ten families were killed in 1978 alone. In 1975–76 the New people had been regarded as “enemies,” but had not been killed; the Southwest Zone cadres now told the people that enemies of the regime had become “Khmer bodies with Vietnamese minds.”

Such population purges often occurred in the wake of disruptive local events, as Pech Sovannareth recounts:

In January 1977. . . the people of Chicheng and Kompong Kdei [had] rebelled, and drove out or killed the old leaders. . .. These rebels arrived [in Sovannareth's village], and [Khmer Rouge] soldiers were disarmed, mingled, and worked with the people. Then a new group of soldiers arrived two or three days later and arrested all the old cadres and soldiers and the [rebel] people, and took them in trucks to Siem Reap to be killed, “to study.” These new forces began arresting the people and killing them, for the first time since the 1975 wave. . .. They said they were real, “strong” socialists; all others were “traitors” (Kiernan, interview).

Local disruptions often led to official framings of the Base as “traitors,” blurring the collective boundaries between ally and enemy, and making generalized violence much more likely.

Official crisis frames, in the form of strong, credible narratives of threat from internal enemies, are a central factor in explaining the spread of violence to both Base and New in Period III. These narratives of threat acted as powerful situational mechanisms that, when present, challenged the fixity of previous distinctions between New and Base groups, suggesting that the Base might harbor equally counterrevolutionary sentiments. This demonstrates that official crisis frames can not only heighten the salience of existing collective boundaries (Oberschall Reference Oberschall2000), but also rearticulate and transform established protagonist and antagonist identity fields (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Benford, Snow, Larana, Johnson and Gusfield1994) through changes in their diagnostic attributes, producing important shifts in the organization of violent victimization. The extension of the central CPK's coercive capacity across different regions, while operating as the primary vector of increasing violence, does not account for the shifting directionality of violence between Periods II and III. Collective processes of moral distancing and crisis framing help account for these changes in group victimization.

Of course, resonance is a central factor in explaining the effectiveness of framing processes: frames must make credible claims about existing social conditions. Here the cognitive effects of strong systemic disruptions in Period III play a key role, in that they provided an experiential basis for making frames of spreading internal dissent salient with local soldiers and authorities. The occurrence of uprisings and rebellions, mass food shortages, and other highly disruptive local events, in the context of the CPK's ongoing campaign to consolidate political control, would certainly resonate with official statements that the revolution was being sabotaged by internal “treachery.”

The distinct microdynamics of genocidal violence for the New and Base are illustrated in the “substantive historical models” in figures 2 and 3. For the New, the purported enemies of the Pol Pot regime, there were multiple pathways to genocidal victimization throughout Periods II and III. For the Base, however, there was only one sufficient pathway to genocidal victimization in Period III: the conjunction of increasing political coercive capacity, local quotidian disruptions, and salient official crisis frames in the context of declining intergroup polarization. This specific concatenation of meso-level mechanisms resulted in the realignment of collective boundaries such that any individual could be seen as a potential “enemy” of the regime.

FIGURE 2. Substantive historical model of New class victimization

FIGURE 3. Substantive historical model of Base class victimization

Discussion and Conclusion

Historical scholarship indicates that genocidal violence in Cambodia spread as the coercive arm of the CPK state extended its reach across different regions. But why did violence so rapidly shift from the purported enemies of the regime to its potential base of support? The findings of this study suggest that this transformation is accounted for, in part, by the official invocation of crisis frames that became salient in the wake of strong quotidian disruptions and declining intergroup polarization, realigning group boundaries and broadening collective potential for victimization. This illustrates that perpetrator and victim group boundaries during genocides are not always stable constructs. Rather, such boundaries operate as “contrast conceptions” (Shibutani Reference Shibutani and Shibutani1973) that are managed, negotiated, and potentially transformed in light of emergent events and available frames of meaning (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Benford, Snow, Larana, Johnson and Gusfield1994). Boundaries are dynamic products of boundary “work,” rather than static properties of actors (Lamont and Molnar Reference Lamont and Molnar2002), and exclusionary ideologies (Harff Reference Harff2003) function as both a resource and constraint in their construction, maintenance, and transformation. Framing processes are critical in accounting for how broader ideologies are negotiated and understood at the meso-level, and therefore in explaining how these emergent understandings influence the subsequent organization of intergroup violence. This insight is especially important for clarifying the relationship between genocide and revolutions (e.g., Melson Reference Melson1992), because revolutions rarely go according to plan.

In this way, this study extends recent efforts to apply a collective action perspective to genocide. Understanding how genocide and other mass violence spreads and evolves within specific meso-level contexts, and identifying the mechanisms that facilitate these processes, remains an important challenge for social scientific inquiry. The role of broader political and institutional forces in genocides remains central, and I have only indirectly accounted for them in this study. A related shortcoming of my data is that it gave me little access to the characteristics of perpetrators in different areas (who they were and why they committed violence, or not), and the specific policies decided upon by military and administrative institutions in different geographic regions. The meso-level approach advocated for here should thus serve as a supplement to others in the field.

Lastly, the continued use of configurational comparative methods such as QCA may help genocide scholars to more firmly link their theoretical arguments regarding the causal complexity of genocide with their analyses. Genocide is generally conceptualized as an outcome of interactions between multiple contributing factors that are rarely sufficient on their own, but researchers have not employed methods that empirically account for this interaction. As a result, the precise combinations of conditions that account for the emergence of violence across different areas can only be accounted for indirectly. Methods such as QCA allow for recognition of causal complexity, identifying the precise concatenations of mechanisms that produce important variations in the dynamics of violence. Having proven to be of great utility in the Cambodian case, use of QCA and other configurational methods would likely be fruitful in exploration of other cases.

Appendix Tables

TABLE A1. Moral distancing coding

TABLE A2. Political coercive capacity coding

TABLE A3. Crisis framing coding

TABLE A4. Systemic disruption coding