Unless we count his modest contribution, along with four other composers, to Der Stein der Weisen, The Magic Flute was a new type of opera for Mozart, at least in its handling of word-music-drama relationships.1 It was less new in other ways; its moral content is anticipated in Die Entführung aus dem Serail, where, as again in La clemenza di Tito, the characters’ fate lies in the hands of a benevolent autocrat (here Sarastro). The Introduction, arias, ensembles, and multisection finales followed naturally from Mozart’s recent Viennese comedies, but with significant differences. Spoken dialogue bears much of the weight of action and characterization conveyed in opera buffa by simple recitative. At dramatic high points, Italian opera uses orchestrally accompanied recitative (the voice supported by expressive instrumental gestures), usually leading to an important aria. In The Magic Flute, orchestrated recitative occurs mainly in the finales, which would be unusual in opera buffa.2

The variety of forms and the passages in finales that are neither recitative nor aria look ahead to the more continuous opera of the next century. From a post-Wagnerian standpoint, linking stage action to musical design may seem unremarkable. But closed, fully cadenced forms were the eighteenth-century norm, despite the example of Gluck’s later operas, where recitative, arioso, and aria come closer thanks to his abandonment of simple recitative. The long finales of The Magic Flute are unlike those of the Viennese comedies; they do not follow Lorenzo Da Ponte’s prescription for few if any scene-changes, the music accelerating as characters fill the stage. The finales of The Magic Flute require several scene-changes, and the spectacle assumes greater importance. Another novelty is that two “characters” are multivoiced, but sing as a unit: the Three Ladies attendant on the Queen, and Three Genii or “Knaben” (boys, although the original singers were female). And unlike Viennese opera buffa, the opera makes serious use of a chorus.

Overture and Introduction

Overtures are the composer’s domain, without text and with the stage as yet unseen. Yet, perhaps following Gluck’s precedent, Mozart linked his overtures to the dramatic action, to the point of prequotation (the overtures were written last).3 So, although the dramaturgy of The Magic Flute is remote from that of Gluck’s late operas, the overture shows what must be deliberate connections to what follows. The overture offers a sense of the numinous, of energy, and of intellectual engagement – all elements that play a significant role in the unfolding action – but it is not a symphonic précis of the opera, unlike the overture written shortly before, to La clemenza di Tito, which has been subtly interpreted by Daniel Heartz as a “dramatic argument.”4

Schikaneder’s public may have expected comedy, sentiment, and fantasy, but the overture prepares for higher styles. The Adagio “alla breve” (two half-note beats per measure rather than four quarters) is not so slow, and is short but solemn. The opening is rhythmically related to the “threefold chords” (“dreimalige Akkord”). In the Allegro, these are “quoted” from Act 2, dividing the sonata exposition from the development. The rest suggests mystery: strings, their dotted rhythm a hushed reminder of the opening, introduce minor coloring, punctuated by soft trombone chords. In the second finale, trombones present a similar dotted rhythm to introduce the chorale and “learned” (imitative) texture of the scene with two Armored Men. This full orchestration with trombones – which retain their association with religion and the supernatural – is unique in Mozart’s overtures (in Don Giovanni, trombones play in the “statue” scenes, but not when the same music opens the overture; his other Vienna operas use no trombones). Fugue, not a standard component of comic opera (despite the ending of Don Giovanni), is a principal topic of the Allegro, which combines fugue and sonata form – a procedure new to Mozart’s overtures but anticipated in the finale of the String Quartet in G, K. 387.5 Unlike that movement, however, the overture has only one well-defined theme, the fugue subject, which is also used for a brilliant tutti, then combined in the secondary key area with graceful woodwind solos (from mm. 57 and 74). The “threefold chords” intrude on the sonata design, bringing the music virtually to a halt (mm. 96–102). The development responds by further resourceful handling of the theme, largely in minor keys, with some strict canonic imitation (basses and violins, from m. 116). The retransition, and Mozart’s compositional resourcefulness in combining the recapitulation with fresh developments (from m. 144), add to the surpassing quality of this overture, which remains a concert favorite despite the oddly intrusive “threefold chords.”

Sarastro’s last words (Act 2 finale) assert that as sunrise expels night, so does virtue overcome wickedness. The breakthrough from night into day is the central metaphor for progress toward enlightenment, and is repeatedly reflected in the music: already in the overture (Adagio–Allegro; stormy development–recapitulation), and in No. 1, headed “Introduction” (sic). The scene presents a rugged, hence dangerous, terrain as Tamino runs on, pursued by a monstrous serpent. The key, C minor, is the dark shadow of the overture’s E-flat. Marked rhythms, tremolo, and sweeping scales represent terror, using the topic identified as tempesta.6 As Tamino faints, a harmonic interruption (m. 40) brings release; the Ladies slay the monster and their “Triumph!” restores the overture’s E-flat. Such harmonic strokes are a feature of later scenes, marking significant turning points in the plot. The Ladies cannot trust one another, if left alone, not to be too affectionate toward the unconscious prince. Thus the dark (tempesta) turns not to light but to the first passage of comedy, with a mild sexual charge. The keys follow the action: E-flat modulates to closely related G minor (by m. 119), followed by a lively G major in 6/8 and a furious stretta, closing in the tonic C, but in the major, at a faster tempo.7 No. 1, therefore, is an introduction to dramatic contrasts – terror; triumph; popular, if slightly misogynist, comedy – and to the opera’s principal tonalities.

A Tonal Overview

After E-flat, C, and G, the principal keys used in The Magic Flute are F and B-flat, neither of which frames a finale; nor does G, but its association, in major and minor modes, with Pamina and Papageno gives it an importance comparable to the framing tonalities.

A word of caution is needed in connection with keys. The subject offers more than the usual temptation to search for key symbolism, but while E-flat, the overall frame, has been associated with Freemasonry partly because it has three flats, it is also used for the servants of the evil Queen (Introduction). Mozart also employed C, major and minor, for “Masonic” works. C minor (also with three flats) reappears in the second finale for the solemn chorale before the trials of initiation, but also for the last entry of the Queen and her minions, intent on violence. C major frames the first finale and reappears in the second for the trials (and so for both “magic flute” solos), but C is also the key of Monostatos’s aria as he prepares to rape Pamina. A composer’s hands cannot be tied by fixed connotations of keys, even within a single work.

Tonality on its own cannot distinguish truth from falsehood, good from evil. Mozart’s choice of keys reflects practical considerations, instrumental (since only a few were then available for natural trumpets) and vocal, reflecting Mozart’s concern to “fit the costume to the figure.”8 His chosen keys place notes from the tonic chord, normally the third (mediant) or the fifth (dominant), high but comfortably within his singers’ ranges. These are usually exceeded by no more than one degree, at moments of climax or intense expression.

C and E-flat suited Benedikt Schack (the first Tamino); as Abert remarks, “It is doubtless largely thanks to Schack that the role of Tamino is of such high quality.”9 In his aria (No. 3), high G (g′) is the mediant in the tonic chord, E-flat, and the highest notes are all a-flat′. His first-finale solo is in C, using both a-flat′ and a-natural′ above the dominant, g′.10 The keys of G and F suited the actor-singer (baritone) Schikaneder (the first Papageno); both his arias and his solo in the second finale (also in G) exceed the dominant by one degree, reaching e, d, and in the finale a poignant e-flat′ borrowed from the minor mode as he contemplates suicide. B-flat (the Queen’s first aria, No. 4) and F (within the second, D minor, aria) invited Josepha Hofer’s top note (f′′′), approached by a leap, and probably attained by a vocal harmonic; it is noticeable that in her second aria (No. 14) f′′′ does not reappear in the final section. But B-flat is not the Queen’s personal key; it is used for the stern “threefold chords” and the Act 2 trio (No. 19) for Pamina, Tamino, and Sarastro. The keys of Sarastro’s principal utterances exploit the vocal resources (low notes, wide intervals) of Franz Xaver Gerl. His aria (No. 15) is in E, reaching c-sharp′, one degree above the dominant; his deepest note is F, the keynote of “O Isis und Osiris” (No. 10) and the fifth (dominant) in the trio. Mozart appreciated that Anna Gottlieb (once little Barbarina in Figaro) could now, as Pamina, ascend expressively to high B-flat and pitch wide intervals in her aria (No. 17). In each finale she sings important passages in F. In the first (from m. 395), kneeling, she explains her escape to Sarastro (whose kindly response brings his first low F).11 In the second finale (from m. 277), embracing Tamino, she leaps to the high mediant, a′′. Such instrumental and vocal considerations were more likely to have been at the forefront of Mozart’s choice of keys than symbolism or larger structural questions.

Musical Styles

The variety of musical styles in The Magic Flute, and the separation of musical numbers by lengthy dialogues, gave rise to a study whose title queries whether it is more muddle than masterpiece.12 The Magic Flute overture prepares us for grand ideas, and for storm and stress, but not for the sufferings of the characters; the Introduction (No. 1) combines terror and high comedy. Papageno’s entry introduces a new stylistic element, for “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja” (No. 2) is headed “Aria” but is essentially a popular song.

Seeing the dead serpent, Papageno flinches, but (in speech) he is soon lying glibly to Tamino. This first passage of spoken dialogue introduces elements – comedy, deceit, friendship – that recur throughout the opera, in speech and in musical numbers. The strophic song form used by Papageno (twice) reappears in arias for Monostatos and Sarastro; Mozart also found strophic forms useful in arias that are not popular in character. The central plot is launched when, in the first true aria (No. 3, “Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön”), Tamino contemplates Pamina’s portrait. Like most arias in The Magic Flute, it is in one tempo throughout. Although Mozart composed several important arias in two or more tempi (e.g., those for Fiordiligi in Così fan tutte), only two in The Magic Flute change speed: the Queen’s first, grandly operatic in style, and Papageno’s second, popular in style. This usage corresponds to Der Stein der Weisen (written for – and, indeed, partly by – some of the same singers).

Mozart’s aria forms, like their keys, were selected to suit the strengths of the singers. But, in turn, these choices may affect our understanding of character. In a strophic song or a single-tempo aria the dramatic situation remains essentially unchanged; rather than advancing the action, the music explores the singing personality. Correspondences with characters in other works by Mozart, not necessarily of the same voice type, also contribute to the context in which we listen today: Heartz revealingly juxtaposes passages from The Magic Flute and La clemenza di Tito.13 When Tamino rises in his first phrase to g′ (the mediant), and develops it with its upper neighbor, the resulting gentle tension suggests comparisons to Mozart’s song “Das Traumbild” and the Countess’s E-flat aria (“Porgi amor”) in Figaro.14

The arias in Act 2 richly develop the varied characters: Monostatos intent on rape (No. 13), the Queen chastising her daughter (No. 14), Sarastro comforting Pamina (No. 15), her despair at Tamino’s obdurate silence (No. 17, “Ach ich fühl’s”), and Papageno’s second strophic song (No. 20, the stanzas progressively elaborated by the “magic bells”). Each form suits characters whose feelings at this stage are concentrated on one thing only. This makes the two-tempo aria for the Queen in Act 1 (No. 4) a significant exception. We hear her approach before we see her; the libretto mentions a “hideous chord with music” (“erschütternde Akkord mit Musik”), for which Mozart provided no notation. Her arrival should be spectacular, and her appearance visibly alarms Tamino, for her first words, in recitative, are “Do not tremble” (“O zittre nicht”). McClelland identifies her entry music as tempesta, pointing to its “veiled” reappearance in the brilliant B-flat major Allegro that concludes the aria.15 The first, slow section of the aria is a plaint in G minor, the key Mozart favored for women in distress.16 The voice rises with almost overdone sincerity to a semitone above the keynote (a-flat′′), foreign to the G minor scale, and the harmonized cadential descent (mm. 59–60) employs all twelve pitches of the chromatic set.

At this point, the Queen appears sympathetic, and Tamino is easily persuaded to attempt Pamina’s rescue; but her music – including another unusual feature: aria sections in different keys – may allow us to question her sincerity. The difference from Pamina’s G minor aria is telling. The 6/8 meter of “Ach ich fühl’s” is more lilting than the Queen’s 3/4, but the phrasing is hesitant, the vocal line divided by rests. The Queen’s line is more sustained and controlled (indeed controlling, of Tamino). Pamina’s coloratura (many notes to a syllable) is slower, gentler, and not stratospheric like the Queen’s, and her wide intervals (one and a half octaves: m. 34) are agonized where those of Sarastro seem authoritative, secure. Wide vocal intervals for Fiordiligi are sometimes misinterpreted as satirical, but they were part of every prima donna’s technique.17

Chromatic saturation does not in itself imply insincerity. In the Queen’s aria, it provides information which, with hindsight, suggests that, if not actually lying, she is operating on Tamino for her own selfish ends. Pamina’s closing phrases use ten of the possible twelve notes (lacking only F and B), but her final cadences are straightforwardly diatonic. She is less complex than her mother, but the distribution of musical elements suggests the genuineness of her love and consequent misery. Pamina’s entry in the second finale adopts C minor and then intensifies tonally to G minor (from m. 80); all twelve pitches are in play at the cadence (mm. 92–93). Yet this cadence is deceptive; the music, like her suicide, is interrupted when the Genii intervene, and G minor is displaced by E-flat, which the Genii adopt for the Allegro. Thus the course of Pamina’s life, like Tamino’s in the first finale, is turned round by a harmonic deception.

Whereas in Mozart’s opera buffa finales, the linked sections consist mostly of ensembles that usually run their course to a cadence, those of The Magic Flute include various kinds of declamation, recitative-like or in tempo, and sections of music that are “open” in form, without a final cadence. This freedom enabled him to include the complex scene of Tamino’s realization that all may not be as it seemed prior to his arrival at the temples. Following solemn, if nonspecific, advice from the Genii, he is left alone to express his puzzlement in recitative. Rejected at two of the temple gates, he is confronted at the third by the “Elderly Priest” (also sometimes called “Sprecher” [Orator]18) whose entry, which changes Tamino’s life, is signaled by a change of harmonic direction when A-flat follows the descending C minor arpeggio (m. 85, Adagio). Recitative allows Mozart to distinguish orchestrally between Tamino’s impetuosity and the Priest’s grave, if cryptic, responses. When Tamino grows agitated, with tremolo (m. 109, “Sarastro herrschet hier”), the harmony implies resolution into F minor; as if in reproof, the Priest contradicts this expectation with a C minor chord (m. 110), rather than C major, the dominant of F. More sustained harmonies, as if to calm the young man, introduce the Priest’s last words, sung in tempo (m. 137), in A minor, to a distinct melodic shape – a minuscule arioso.

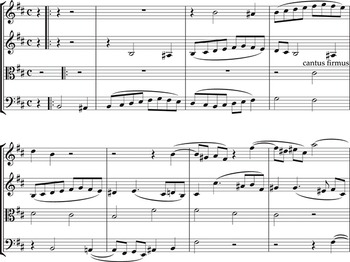

Still more perplexed about what is truth and what deceit, Tamino invokes the night (“O ew’ge Nacht!”), retaining the key of A minor, but with an unmistakable echo of the Queen’s first words (Example 5.1). Can this be coincidence? Perhaps it was intentional; by harmonizing with the voice (the Queen’s a′ and Tamino’s g-sharp: her “nicht” and his “Nacht”), the chords in the upper parts clash with the retained bass note.19 Other musical cross-references, making connections across the spoken dialogues, suggest that in this opera Mozart, or his unconscious, may have been working that way. The scene is concluded in A minor, when the Priest’s miniature arioso is twice repeated on cellos, accompanying the unseen male chorus.

Example 5.1 The Queen’s “O zittre nicht” (No. 4) and Tamino’s “O ew’ge Nacht” (No. 8).

Tamino has recourse to the magic flute, playing solo in a section unlike anything in Mozart’s other finales.20 “Wie stark ist nicht dein Zauberton” is an open form; after a reprise and a darkening to C minor, the flute scale is answered by Papageno’s pipe and the song breaks off. Tamino’s excited response (m. 212, Presto) ascends to f′, then a′, on a pause (m. 216); there follows one measure only of Adagio, then Presto, this time with a cadence in C. He exits to a recitative-style punctuation figure, very much like that with which he had approached the temples. Unfortunately, Pamina and Papageno enter from the other direction, as if to remind us that The Magic Flute is, among other things, a comedy. The last part of the finale, framed by choruses in praise of Sarastro, proceeds swiftly and flexibly through confrontations and the noble couple’s moment of recognition. The key scheme is simple (C major and near relations G and F), without deceptive tonal shifts, for good and evil are now distinct; Sarastro’s speech to Pamina is all benevolence, he punishes Monostatos, and although he parts the lovers before their trials, trumpets and drums in C major proclaim his dignity and strength.

When Mozart went to Munich to work on Idomeneo in the presence of the singers, he engaged in an epistolary battle with the librettist (by way of his father) and exerted further control by composing the final ballet, which could have been left to a local composer. In Vienna Mozart lived near his poets, so there is no comparable record of their collaboration. But given his intimacy with Schikaneder and his troupe, it seems likely that he helped shape elements of the libretto and stage action and was happy with the freedom these offered to select appropriate musical forms without having to bend to the will of the highly paid singers at the court theater. Schikaneder, as impresario, no doubt took a controlling hand in ensuring the variety and brilliance of the spectacle, but it was surely Mozart who decided to set the various trials to strikingly original music that eschews the invitation to melodramatic excess.

Pamina, unlike Tamino and the reluctant Papageno, seems not to know that she is being subjected to trials, which she mostly has to face alone. The men receive specific advice after the solemn hymn (“O Isis und Osiris”), when two Priests interrogate them in dialogue, concluding with a very short duet (No. 11). The words are an invitation to critics of the opera seeking out misogyny. But Mozart does not present this stern advice to beware of the wiles of women in severe, minor key music, nor in the martial style already associated with Sarastro. Instead, the music is fast, light in tone and texture, in a comic vein, the flowing, galant melody incorporating a chromatic innuendo (on the words “er fehlte”). True, the orchestra includes trombones. But even the march-like conclusion (from m. 18) is sung sotto voce, with the orchestra piano and staccato. Mozart seems to imply that although the men must follow the Priests’ injunction, we – the audience – should not take it too seriously.

Tamino is given no music to correspond to the pain he must feel on hearing Pamina’s aria (“Ach ich fühl’s”), and his flute, even if it is heard during the dialogues (as sometimes happens, without notation from Mozart), is of no service here. The use of dialogue, rather than recitative, contributes directly to characterization when the Queen, who does not speak in the first act, confronts Pamina before her tempestuous “Der Hölle Rache” by talking – like an ordinary person. In this justly celebrated aria, requiring her to hit the top note four times (against once in Act 1), Mozart again shows his resourcefulness in handling tonal form, which requires a return to the original key, D minor, and also to the passagework heard in the subsidiary key, F major. So her rage now overflows in running triplets (from m. 69), before the passagework resumes, compensating for its lower pitch (reaching d′′′ rather than f′′′) by a sequential extension (from m. 77). The conclusion is an incisive recitative (“Hört der Mutter Schwur!”), with eleven pitches (missing only C) in the last few measures.

Another trial for Pamina is that she is reintroduced to Tamino (in dialogue), only to be told by Sarastro (speaking) that they are meeting for their “letzte Lebewohl” (final farewell). When the music starts (Trio, No. 19), Sarastro contradicts himself, singing that they will meet again (“Ihr werdet froh euch wiedersehn”). The lovers seem not to hear, even at the end where Sarastro’s deep notes reassure us: “We’ll meet again” (“Wir sehn uns wieder”). Pamina’s deafness to Sarastro’s words leads to further despair and her resolve to die if she must lose Tamino. The trio’s music is serene (Andante moderato in B-flat, with few woodwind instruments but no brass or percussion) and may represent the truth of the situation, but not the whole truth, for it leaves the lovers in uncertainty. In the interests of dramatic suspense, Mozart is careful not to express this too obviously.

The lovers’ reunion within the finale is in F major, the key of the solemn march that opened Act 2. Now Pamina takes control; after an outburst of joy, she becomes grave on recognizing the magic flute. As in the parallel scene with the Elderly Priest in the first finale, Mozart turns to near-recitative, moving fluidly (m. 317) to G minor, before returning to the local tonic, F, for a quartet in which Pamina soars above Tamino and the two Armored Men. After each trial the lovers’ voices join, their personalities merged as if in matrimony; their silence in the last scene at their moment of glorification marks their absorption into the community, and with it, perhaps, a loss of autonomy.

For the final trials Mozart hit on something extraordinary. Did Schikaneder ask him not to make the music too exciting, in case it distracted from the visual representation of the perils of fire and water? For in this scene the spectacle (as in the French “merveilleux”) should indeed be wonderful. Mozart makes no attempt to parallel what the stage machinery offers; fire and water are alike in the music. Not every late eighteenth-century composer would be so reticent; compare the collapse of the magic palace and gardens in Lully’s Armide (a simple, major key flourish) with the D- minor histrionics to which Gluck set the same libretto (1777). Mozart created a unique sound-world; it sufficed to provide the flute with its second solo, over basic harmony from a brass choir, the phrases softly punctuated by timpani. Taken out of context, this might appear dry, unresponsive, and not a little weird; within the opera it is utterly compelling.

Apotheosis of Papageno

When the chorus proclaims “Triumph!” the opera might have ended, except that the key is still C major, not E-flat, and Papageno’s story is incomplete. He seems to have failed the trials, but he is otherwise worthy and does no harm. He has glimpsed a youthful Papagena, cruelly snatched away. He becomes worthy of her through his willingness to die. The scene is in G major, like his first song, but the musical form is far from simple. He calls her name, with a fanfare shape resembling the choral “Triumph!” of the Act 1 finale, and pipes in vain to summon her. Then comes new melodic material that forms the basis of a sonata rondo of 130 measures, a thoroughly modern (though usually instrumental) form that cannot be called popular. Mozart takes full control by imposing a musical design on a shapeless text. The rondo theme involves stuttering calls and the smoother phrase first heard at measure 418. When this phrase returns at measure 444, the two-note anacrusis will not fit the words, so Mozart uses a three-note anacrusis instead; at measure 468 the original anacrusis is restored (Example 5.2).

Example 5.2 Papageno in the Act 2 finale, comparison of mm. 443–47 and 468–71.

The rondo episodes are Papageno’s only extended minor-mode music, though his tragicomic “O Weh!” ended the first-act quintet in G minor. The first episode uses the relative, E minor, with an agitated running figure inverting his piping motif (Example 5.3); chromatic runs further expand Papageno’s musical lexicon.

Example 5.3 Papageno in the Act 2 finale, motives from the same section, mm. 415–17 and 447–49.

In the second episode, as if in empathy with Pamina, Papageno adopts G minor, relating the episode material to the main keynote. His tonal domain is further enriched by cadences in its relative, B-flat (to m. 493). Papageno is an allegro character, but now he falters, with sensitive chromatic touches (G minor, with “Neapolitan” A-flat, m. 539), in a passage that could almost be inserted into her aria. Again, harmonic interruption signals a change of fortune; a G-minor cadence seems to have been prepared, but is displaced by a dominant seventh on G, pointing to C (m. 543). In a new tempo and meter, the Genii remind Papageno of the magic bells, which ring out again in C major before the scene is rounded tonally by returning to G for the duet with Papagena.

This is the climax of the comic element in The Magic Flute, but with all Papageno has gone through, it is an epiphany he thoroughly deserves, prepared by the relative complexity of his sonata rondo. With the ensembles in which he takes part, this scene confirms that Schikaneder was an accomplished musician as well as a versatile actor and ambitious impresario. This apotheosis of the bird couple is remote from the world of the temple, but the authors’ enlightenment conception seems to have been that simple folk, without ambition and represented mainly in a comic mode, should receive their due as real people who can also suffer. Papageno’s actions are a potent critique of the initiates who have brought him to this pass. Mozart’s music is pitched at a level that makes it possible to interpret it as simultaneously comical and essentially serious. We may laugh at Papageno’s counting one-two-three before accepting his destiny, but it is through tears – unless we withhold those for the sudden incursion of the Genii, whose music throughout is among the most beguiling of the whole opera.

The Genii and the Ending

The Genii (“Knaben”) embody the comical sublime that binds the disparate strands of the opera – not, mercifully, into a “unity” but into a more interesting kind of wholeness. They are purely musical; they are only heard in song. Their first entry (Act 1 finale) is heralded by an imposing slow march, using trombones for the first time since the overture, in marked contrast to their high voices. On their last appearance, they toss Papagena onto the stage in a scene of pure fun. These entries may be made on foot, but for one delicious ensemble (No. 16), they should appear in a flying machine (“Flugwerk”). Their words echo the Priests in commanding the initiates to silence, distinguishing Tamino from Papageno, but the music is the same for each; the dancing A major Allegretto in 6/8 has some of the lightest orchestration even for this opera, so that, as with the Priests’ duet, we are encouraged not to take the next trial too much in earnest. Sounding graver in the second finale, counseling Pamina (from m. 94), the Genii nevertheless sing in a delicately orchestrated galant style. Less individualized than the Queen’s Ladies (the first of whom has a few solo passages and who do speak), the Genii affect the action more and touch the extremes of the opera’s dramatic and musical range.

At the end, a scene heralded by a glorious sunrise, the Genii and the noble lovers are on stage, but silent. The Queen’s futile attempt at a coup is followed by a final transition from darkness to light and to the framing key, E-flat major. The brittle C-minor march of the Queen and her minions and the violence of their overthrow are slowed by whole-measure harmonies in tremolo (Example 5.4). The transition emerges onto F, which, with an added seventh, brings temporary closure in B-flat. The chain of suspensions (mm. 820–21) invites a slight relaxation of the tempo, not indicated by Mozart but an invitation to conductors that is sometimes accepted to good effect.

Example 5.4 Act 2 finale, the Queen and her entourage, mm. 812–22.

As the stage fills with light, orchestral gestures give Sarastro’s short recitative the incisive character of his entry in Act 1. His speech overlaps with a steadily unfolding cadence, in tempo (Andante), settling in E-flat. The chorus enters with more intertextual references. Within the Act 2 finale, the scene of the two Armored Men already recalled the overture by its imitative counterpoint (albeit with a different theme) and the first finale by its solemn introduction. The latter is more literally redeployed to start the final two-section chorus that proceeds from solemn thankfulness to festive joy (Example 5.5).

Example 5.5 Act 2 finale comparison: mm. 190–96 (Adagio of the Armored Men) and 829–34 (in the opera’s last scene).

The glorification of Pamina and Tamino is followed by an Allegro contredanse of the kind often used in symphonic finales, its pointed first theme (m. 847) contrasted with a lyrical phrase (m. 787), which may remind us that this work was intended to entertain as much as, if not more than, edify.

The Magic Flute, in sum, is not a muddle, but an inspired synthesis of stylistic elements. Joseph Kerman endorsed Edward J. Dent’s “appreciation of the impeccable dramatic structure,” in which “the music sums up the dramatic situation and illuminates it” in every number.21 In this respect, the music also justifies the dialogues which Dent’s edition curtailed, while resisting any temptation to subvert the work’s nature by substituting recitative.22 Antonio Salieri, no mean composer of opera, serious and comic, and Caterina Cavalieri, the first Konstanze in Die Entführung, rightly called The Magic Flute an “operone” (grand opera).23 There is no need to apologize for its stylistic mixture which, on the contrary, is an essential part of its strength.

The arias in Mozart’s The Magic Flute are undoubtedly some of the most recognizable in the operatic repertoire. What factors influenced their creation? The same ones that shaped practically all opera arias in the eighteenth century: poetic structures, musical and dramatic conventions, as well as the abilities of the singers who originated the roles. Staging and other practical considerations also played a part. What, then, makes these arias so enduring and memorable? Mozart’s ability to create vivid music that portrays the character and dramatic situation might be one answer. How the arias explore and stretch customary operatic practices and musical language could be another. The composer seems to have taken great care to make each aria distinctive. The arias’ diversity of style, color, and affect is striking, especially when we hear and see them in the context of the drama. Moreover, most contain something unusual or extravagant – a musical element or moment that extends beyond the ordinary. As a result, the arias offer a compelling demonstration of one of the opera’s main themes: the power of music.

What Shapes an Aria?

All arias involve multiple components – what some analysts refer to as “domains.”1 Poetic structures and literary devices within the text often shape the vocal line’s phrases as well as the aria’s musical meter and overall musical form. The composer can opt to adhere closely to the text’s poetic form (to set the text line by line, for example) or s/he can choose to repeat words, sentences, or entire stanzas. The vocal line can be primarily syllabic or melismatic (multiple notes present one syllable of text); it can be more declamatory in nature, lyrical and tuneful, or florid. As we shall see, how the orchestra interacts with the vocal line can vary a great deal. The instruments can double the voice, utter comments in between the vocal phrases, or be quite independent. The orchestral material itself may encompass interlocking rhythmic layers, and certain instruments may carry semantic associations. In addition, the dramatic situation and a character’s social status and gender can also influence an aria’s musical content.2 Finally, the strengths and proclivities of the initial cast actively shaped the music. Eighteenth-century composers knew the singing and acting abilities of the performers who would premiere their works and composed with those in mind. The original singer’s range and technical prowess could influence an aria’s tonality, orchestration, and, most importantly, the scope and nature of the vocal line, including such things as the size and number of the leaps or runs it contained. As Mozart himself wrote in February 1778, “I love it when an aria is so accurately measured for a singer’s voice that it fits like a well-tailored suit of clothes.”3

In other words, even though arias combine music and text and use standard musical forms, many additional factors influence the end result, which in turn affects how and what the number reveals about the character who sings it. While many writers focus primarily on musical form when analyzing arias,4 The Magic Flute contains examples in which overarching form is perhaps the least important and telling aspect. Frequently, other elements contribute more to the aria’s expressivity and the dramaturgical role it plays. Our journey through The Magic Flute’s arias will begin with three examples that share the same form, to demonstrate how these other musical and dramatic components shape a number. It will then examine arias for each character, to show how Mozart responds to poetic content and structures, adapts conventions, “tailors” arias to the singers who created the roles, and infuses each number with delightful, extravagant touches.

Strophic Numbers for the Bird-Catcher, the Moor, and the Ruler

“Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja,” “Alles fühlt der Lieben Freuden,” and “In diesen heil’gen Hallen” share the same form. All are strophic; in each case, two stanzas of text are set to the same music. Because the poetic stanzas share the same meter and number of lines, the same music can be repeated for each verse of text. In all three arias, the rhyme scheme remains the same for both verses.

In addition to matching stanzas, the text for the first aria sung by the bird-catcher Papageno, “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja,” contains other poetic features that influence the musical form (see Table 6.1). Both eight-line strophes commence with exactly the same four lines. Each poetic line ends with an accented syllable. The text’s straightforward meter and simple rhyme scheme (rhyming couplets) prompt end-oriented phrases in the music: regular four-bar phrases that begin on upbeats and cadence on strong beats.

Table 6.1 “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja”: text, translation, and rhyme scheme

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Center column of letters = rhyme scheme. Bold = accented syllable & line ending.]

Much else in the aria remains within a narrow scope. The vocal line spans a ninth, but many of its gestures move within a fifth or even a third. The upper strings largely double the voice. The limited range and doubling of the voice line may be due to the abilities and reputation of the singer who premiered the role. The first Papageno, Emanuel Schikaneder, was the opera’s librettist and the star of the troupe. He was primarily an actor and impresario, not an opera singer, and had performed in a wide variety of roles; in Vienna, he had made a name for himself by playing comic, not too bright, peasant characters such as the gardener Anton (another role he wrote for himself).

Yet the aria’s harmonic vocabulary is also limited, inordinately so. Most chords are in root position; tonic-dominant-tonic progressions dominate; many dominant chords lack a seventh. Mi-re-do (3–2–1) figures permeate the melody. In other words, the music is about as diatonic as it could possibly be. The key – G major – is simple, too.

Together, the limited verbal, melodic, and harmonic content gives the impression that Papageno is the unsophisticated “Naturmensch” (natural man) he later claims to be. What you hear is what you get. The strophic form, straightforward syllabic melody, and nonsense syllables in the text also give the aria what some commentators call a Volkston or folk tone.5

Monostatos’s aria, “Alles fühlt der Liebe Freuden,” also uses strophic form, but the aria’s poetic and grammatical structures, irregular phrases, and musical conventions for portraying Otherness result in a very different-sounding aria. Like “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja,” the text consists of two eight-line stanzas that share the same meter and rhyme scheme, but in this case the rhyme scheme and metrical pattern are more complicated. Each poetic line begins with an accented syllable; thus, practically every vocal phrase starts on a strong beat. The ends of lines, however, alternate between accented and unaccented syllables. Some poetic lines, particularly in the second verse, contain incises or shorter phrases within the longer line, as in the stanza’s opening lines:

| Drum so will ich, weil ich lebe, | Thus, I wish, because I am alive, |

| Schnäbeln, küssen, zärtlich sein! – | To coo, kiss, to be tender! – |

| Lieber, guter Mond – vergebe | Dear, good moon – forgive [me] |

In the 1791 libretto, Monostatos is described in the dramatis personae as “ein Mohr” (a Moor). Pamina calls him “Der böse Mohr” (the wicked Moor) during the Act 1 finale (scene 18). Monostatos refers to himself as “Ein Schwarzer” (a black man) during his aria, as does Papageno in Act 1, scene 14.6 “Exotic,” lecherous men were a specialty of singer-actor Johann Nouseul, who premiered the role. The poetry and the character depicted prompted Mozart to employ many of the musical devices associated with “Turkish” music in the 1700s, including duple meter, a fast tempo, and phrases that begin on a strong beat with a longer note followed by sixteenths or eighths and are uneven in length.7 The aria opens with a lopsided nine-measure introduction (five measures plus four measures) rather than the customary four, eight, or two bars. Irregular phrase lengths continue throughout the aria. In fact, just as five-measure phrases seem to become the norm, two-measure or three-measure insertions interrupt the pattern (see mm. 25–34, for example).

The instrumentation also signifies Otherness. The piccolo (an unusual instrument for the time), flute, and first violin double one another, while the lower strings reiterate a single pitch for the first five bars. As Mary Hunter has argued, the alla turca style “represents Turkish music as a deficient or messy version of European music.”8 In this case, the sparse orchestration supports an equally sparse or “deficient” tune. The melody circles around a single pitch, the tonic. In fact, one could apply the epithet “too many notes” to this number – it has too many of the same notes, because so many pitches are reiterated. Even the aria’s home key, C major, can be considered a sign of Otherness, as that tonality was commonly used to portray these types of characters. In short, much about “Alles fühlt der Liebe Freuden” is irregular, despite the regular rhythms of the text and the repetitive strophic form. Arguably, Monostatos’s Otherness and the resultant musical irregularities have to be contained within a repetitive, predictable form.

Sarastro’s “In diesen heil’gen Hallen” is also strophic, but differences in multiple domains distinguish it from the opera’s other strophic numbers. The aria’s text consists of two six-line stanzas whose scansion is more complex than the above examples. Lines 1–4 alternate rhymes and unaccented line endings with accented ones. Two lines that conclude with accented syllables close each stanza, forming a rhyming couplet. The stanzas themselves are linked by anaphora – beginning with the same word or phrase – in this case the words “In diesen heil’gen.” This poetic device implies strophic form.

While the overall musical form of the aria is strophic, the strophe itself is through-composed. The vocal line does not conclude any of its phrases on the tonic until the strophe’s final bars; instead, Mozart has the vocal phrases end on scale degrees 3 or 5. Both of these musical choices create a sense of forward momentum and continuity of thought. The shape of the vocal line does as well. In accordance with the prosody of the text and in contrast with Monostatos’s aria, Sarastro’s vocal lines all commence on an upbeat; most conclude on a downbeat on a more stable harmony. While the vocal line in all three strophic arias is largely syllabic, Sarastro’s vocal line is more conjunct and thus sounds more lyrical. Appoggiaturas abound.

The relationship between the accompaniment and the vocal line also differs. Even a cursory glance at the score reveals more counterpoint between the voice and the orchestra than in the other strophic numbers, perhaps due to the skill of the original performer. The first Sarastro, Franz Xaver Gerl, was an accomplished musician, a composer and performer, who had studied under Mozart’s father, Leopold, as a choirboy in Salzburg.

What does the use of strophic form for “In diesen heil’gen Hallen” imply? Perhaps that the character Sarastro and the values he espouses (friendship, forgiveness, love) are constant and unchanging. Together, the vocal line’s low range, the stately tempo, and the aria’s straightforward form depict Sarastro as a calm, reasonable person, particularly since the number contrasts starkly with the aria that immediately precedes it, the Queen’s “Der Hölle Rache.”

The Queen’s Arias: Displays of Power and Rage

The Queen of the Night’s numbers, “Der Hölle Rache” and “O zittre nicht … Zum Leiden,” exemplify how Mozart “tailors” numbers to a particular singer and adapts a variety of musical traditions to create two of the most celebrated arias ever written. The soprano who originated the role, Josepha Hofer, Mozart’s sister-in-law, certainly had special capabilities. Judging from these arias and other music written for her, she must have had an agile voice and an impressive high register.9 Both of the Queen’s arias require the singer to ascend to an f′′′, the highest note on the Viennese piano at the time. Additionally, the character’s status, musical conventions, and perhaps Mozart’s desire to show off his compositional prowess converge in the Queen’s music.

To take the second aria first, “Der Hölle Rache” is undeniably music fit for a Queen. The marchlike rhythms, full orchestration (strings, double winds, timpani, and trumpets), and extended coloratura passages that require exceptional vocal virtuosity signal that the character is a powerful person of high rank. Here, Mozart adapts a conventional aria type from opera seria. “Der Hölle Rache” has many of the hallmarks of a “rage aria.” Its minor key, large leaps in the vocal line, bustling accompaniment, use of tremolo and sforzandi, and chromatic ascents and descents customarily conveyed great anger during the eighteenth century. But Mozart draws on a local Viennese tradition as well: that of spectacular arias for powerful supernatural characters. Other magical Singspiele written for the company that premiered The Magic Flute contain flashy, vocally demanding arias.10 Paul Wranitzky’s Oberon (1789), which also starred Hofer in a similar role, for example, includes numbers with elaborate coloratura that require the soprano to ascend to a d′′′. Did competitiveness prompt Mozart to write an even higher and flashier aria?

The Queen’s first aria, “O zittre nicht … Zum Leiden,” also presents extreme vocal demands and synthesizes several operatic traditions. Practical considerations shape the scene as well. Written for a theater that was celebrated for its spectacular staging, extravagant music complements extraordinary stage effects.11 A lengthy and majestic orchestral prelude ushers the Queen onstage. Rising arpeggios over a B-flat pedal gradually increase the volume and tonal expanse. The orchestral introduction clearly portrays the Queen as a grand personage (mm. 1–10). It also allows time for the scenic transformation described in the original libretto to unfold:

The mountains part and the theater transforms into a magnificent chamber. The Queen sits on a throne which is decorated with transparent stars.

Mozart draws on several other noble idioms to portray this character. An orchestrally accompanied recitative precedes the aria (mm. 11–20). Accompagnato in this repertoire, like coloratura and the grand prelude, also signified noble or supernatural characters. Motives from the orchestral introduction continue to frame the Queen’s utterances as she reassures Tamino.

| Recitative Do not tremble, my dear son! You are innocent, wise, pious; A youth, such as you, can best Console this deeply saddened mother’s heart. |

“O zittre nicht … Zum Leiden” is perhaps an instance where the text’s structure suggests one musical form and Mozart opted to employ another. The metered poetry of the aria commences with three quatrains, the second of which has shorter lines and a different rhyme scheme. A fourth stanza is marked Allegro. This combination of poetic structures suggests a two-tempo rondò (ABAC in form, with C being in a faster tempo), an aria type associated with upper-class heroines. While Mozart alludes to this conventional aria type, he fashions a number that is looser in form. The Andante section in particular (mm. 21–64) has an arioso-like character and is more formally ambiguous.

| Arie | Aria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Allegro | Allegro |

|

|

The aria proper commences at measure 21 with a triple-meter section in G minor in the middle range of the voice. Mozart carefully crafts the opening paragraph to highlight the character’s plight and the reason for it. Lightly orchestrated three-measure phrases underscore the Queen’s sorrowful opening lines. In keeping with the accents of the poetry, most of the vocal phrases begin and end on weak beats, until the Queen’s revelation that “an evil creature” took her daughter. Here, dotted rhythms and militaristic flourishes in the orchestra lead to the aria’s first strong cadence (both the voice and bass land on the tonic) and a change of key to B-flat major (mm. 32–35).

Word painting permeates the next segment, as the Queen describes how her daughter was taken from her. Fluttering sixteenth notes in the violins depict Pamina’s “trembling,” “fearful tremors,” and “timid struggles” (mm. 38–44). A chromatic countermelody in the bassoons and violas, which perhaps can be heard as representing Pamina, accompanies the Queen’s narrative (mm. 36–44).

The aria’s third verse returns to the soft dynamics, delicate scoring, and the key of G minor as the Queen describes Pamina’s cries for help and her own inability to rescue her (mm. 45–61).12 A lengthy series of minor and diminished harmonies, a deceptive cadence (m. 56), and a prolonged descent in the vocal line conclude her tale and lead into the Allegro moderato that follows.

Once the Queen completes her story, her speech shifts from past to future tense. She issues commands and promises rewards (“You will go to free her”). Mozart reflects the change to the imperative by composing it into the music. The meter, tonality, and tempo all shift – from triple to duple meter, G minor to B-flat major, Andante to Allegro moderato. Mozart also employs contrasting melodic contours. Decisive scalar figures and arpeggios in the vocal line replace the sighing figures and descending phrases that dominated the previous section. Most phrases now commence and conclude on strong beats. In fact, the composer sometimes ignores the prosody in order to do so.

The vocal line soars into the stratosphere (B-flat′′ to f′′′) as we approach the aria’s conclusion. Extensive roulades (m. 79ff.) and the medium tessitura of the accompaniment highlight the power of the singer’s (and the character’s) voice. While Mozart has been criticized for setting the word “dann” (then) on a melisma lasting thirteen measures, such complaints ignore how the word contains a felicitous vowel for singing in the upper register.13 The composer’s choice also stresses the conditional nature of the Queen’s promise. Melodically, the line becomes the equivalent of saying, “And if I see you as the victor, then she shall be forever yours.” The vocal line’s extensive sixteenth- and eighth-note runs broaden to half-notes to drive home the aria’s final words “auf ewig dein” (forever yours). A harmonically decisive postlude that recalls the opening of the Allegro closes the entire scene.

The grand entrance music, the accompagnato, and the vocal pyrotechnics give the impression of a forceful being. The scene as a whole displays the breadth of the Queen’s rhetorical arsenal as she uses three, very different musical styles to persuade Tamino to rescue her daughter. During the accompagnato she reassures and flatters; in the triple-meter Andante section she laments, narrates, and seeks empathy; during the melismatic Allegro she dispenses orders and makes promises. After such a compelling musical and rhetorical display, it is no wonder that Tamino believes she is telling the truth and undertakes his quest.

A Man of Feeling: “Dies Bildnis”

While the Queen’s arias draw on traditional methods of depicting nobility, Tamino’s aria “Dies Bildnis” draws on another prominent eighteenth-century dramatic convention: the portrayal of sensibility. The text’s content and its punctuation indicate passionate emotions. Tamino’s monologue contains repeated words, exclamation points, and dashes, particularly during its second half. The use of first person in eighteenth-century sentimental novels is often interrupted by similar pauses, exclamations, and heavily emphasized or repeated words, as in this excerpt from the quintessential sentimental novel, Samuel Richardson’s Pamela:

This is indeed too much, too much for your poor Pamela! And as I hoped all the worst was over, and that I had the pleasure of beholding a reclaimed gentleman, and not an abandoned libertine. What now must your poor daughter do! O the wretched, wretched Pamela!14

And this selection from J. W. von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther:

Why I have not written to you?—You, who are a learned man too, ask a question like that. You might guess that things are well with me, and indeed—In a word, I have made an acquaintance who has touched my heart very closely. I have—I know not what. … I am unable to tell you how, and why, she is perfection itself; suffice it to say that she has captivated me utterly.

So much simplicity with so much understanding, so much goodness and so much resolve, and tranquility of soul together with true life and vitality.15

As James Webster points out, “Dies Bildnis” as a whole depicts how Tamino’s feelings “progress … from [the character’s] initial undifferentiated reaction to the portrait, through the realization that he has fallen in love, and the confusion engendered by awakened but unfulfilled passion, to conviction.”16 Mozart’s music enhances the arc of Tamino’s emotional journey in a number of ways. The composer matches Tamino’s fragmented ruminations with irregular phrases, harmonic interruptions, rests, and pauses. For example, an unexpected harmony (an augmented sixth chord) on the downbeat of measure 12 underscores the “new emotion” Tamino feels. The musical setting increases the text repetition even more. To give but one instance, the prince asks himself, “Could this sensation be love?” twice (mm. 22–25), before responding, “It is love alone. Love, love, love alone” (mm. 27–34).

|

|

|

|

|

|

| What would I do? – Full of delight, [I would] press her to this scorchingbreast, And then for eternity would she be mine. |

Harmonic arrivals and departures promote the sensation of emotional transformation. This surface variety is grounded in a clear tonal structure. A paragraph in the tonic (mm. 1–15) is followed by one in the dominant key (mm. 16–34). The aria’s third paragraph prolongs the harmonic tension through extended dominant pedals (mm. 35–43) that lead to a grand pause. A full bar of silence precedes the tonic’s unequivocal return at a crucial dramatic moment (discussed below).

The aria’s melodic variety, complex orchestration, and through-composed form suggest that Tamino is a refined, more complicated person. Not surprisingly, the number was written for a sophisticated, multitalented musician, Benedikt Schack, who was praised by Mozart’s father for his elegant singing.17 In contrast to the arias written for Schikaneder, the orchestra here rarely doubles the voice; when it does, it presents embellished versions of the vocal line. At times, the orchestra paints the text; sixteenth- and thirty-second-note figures during the third paragraph, for example, portray Tamino’s growing ardor and pounding heart. Simon P. Keefe suggests that the clarinets, bassoons, and horns included in the ensemble underscore (literally and figuratively) the character’s aristocratic status and were chosen to enhance Schack’s beautiful tenor voice.18

In addition to being an illustration of growing sentiment, “Dies Bildnis” can also be understood as a shift from ignorance to awareness – what Aristotelian poetics calls a scene of recognition. Musically, the aria meets Jessica Waldoff’s criteria for recognition scenes. Her study of these pivotal dramatic moments shows that musical shifts prompt shifts in action or thought, which are then followed by an explanatory narrative. Musical recollections (references to prior material) also frequently occur.19 “Dies Bildnis” encompasses all of these, albeit in miniature. A musical shift precedes Tamino’s realization that he is in love. Winds and horns sans strings lead into his ecstatic “Ja, ja” (Yes! Yes! mm. 24–26). The modulation to the dominant is confirmed decisively in both the vocal and orchestral material shortly thereafter (m. 34). That in turn ushers in an extended dominant pedal as Tamino expounds upon his desires. The character then begins to fashion his own explanatory, self-predictive narrative, a narrative he later seeks to fulfill: “What would I do? I would press her to this scorching bosom, and then for eternity would she be mine.” An entire measure of silence – comparable to the dashes in sentimental fiction – precedes his final declaration. The aria concludes with the richest accompaniment pattern yet (three interlocking gestures) and a musical recollection. The aria’s closing figures repeat, decorate, and extend material that originally accompanied the words “my heart with new emotion fills” (compare mm. 10–15 to mm. 52–61).

Tamino repeats his final declaration five times. Regardless of whether we view this monologue as a sentimental statement or a scene of recognition, “Dies Bildnis” is an extremely end-oriented aria tonally, formally, and dramatically. More importantly, the sense of emotional discovery it conveys arises more from the music Mozart creates than the aria’s text.

The Princess Laments: “Ach ich fühl’s”

While Tamino’s aria depicts blossoming love, Pamina’s sole aria laments its loss. Arguably, this number is the most poignant and the most complex aria of the opera. The character sings “Ach ich fühl’s” in response to Tamino’s refusal to speak to her, mistakenly believing that he has rejected her.

The aria’s home key and instrumentation set this number apart and lend it a “special intensity.”20 As Christoph Wolff notes, “Ach ich fühl’s” is the only aria in the opera with three soli winds (flute, oboe, bassoon).21 The home key of G minor is one Mozart used sparingly in his later operas. The other instances also involve distraught heroines (Ilia in Idomeneo and Konstanze in Die Entführung aus dem Serail, for example) and, as we have just discussed, the account Pamina’s mother gives of her daughter’s abduction (“Zum Leiden”).22

“Ach ich fühl’s” is replete with harmonic and rhythmic tension. The predictable and the unexpected rub against one another in almost every measure. The aria is notated in 6/8. An unrelenting, repeating rhythm in the strings (a march? a heartbeat?) underpins practically every bar. Yet, as William Braun points out, the characteristic 6/8 rhythm of “long-short-long … is nowhere to be found. In fact, it is about the only possible rhythm in 6/8 that Mozart does not use in the aria, and Pamina, almost unbelievably, sings a new rhythm in just about every bar.”23 Even though each line of the aria’s text begins with an accented syllable, the vocal line never begins its phrases on the downbeat. Again, Mozart works against, ignores even, the scansion of the text.

| Ah, I feel it, it has vanished – Forever gone, the happiness of love! Nevermore will come, hours of bliss, Back to my heart. See, Tamino, these tears [that] Flow, beloved, for you alone. If you do not feel love’s longing, Then I must find tranquility in death. |

What does occur on numerous downbeats is dissonance. Tritones and diminished sevenths abound within the vocal line and between it and the bass. Chromatic motion saturates the voice leading as well.

The vocal line begins with three descents in bars 1–4 (from 5 down to 1, from 1 down to 5, and then 6 down to sharp-7), setting up a pattern that permeates the aria. Extended descents and incomplete ascents pull against one another throughout the number. In measures 16–19, for example, the flute and oboe attempt, but cannot even manage, to scale the octave. Instead, they rise through the seventh and fall; their leap downward creates a tritone with their counterpart, the bassoon, whose half-step sighs belatedly resolve the dissonances two beats too late (mm. 17–18 and 19–20).

As Thomas Bauman writes, Mozart uses “silence … as expressively as the notes themselves” throughout Pamina’s lament, but particularly near the end.24 The aria’s final measures contain small, but telling, details. The persistent rhythm subsides (mm. 36–37). The strings sound an eighth note while the voice sustains a quarter (m. 38). Pamina, it seems, is truly on her own, unsupported musically and dramatically. The voice utters its final phrase largely unaccompanied. It hovers on a flat-6 (E-flat, an implied ninth over the dominant) before tumbling down to the tonic again (mm. 37–38). A moment of silence precedes the postlude, whose melodic contours echo Pamina’s earlier pleas but whose rhythms do not.25 Syncopated descents laced with pungent dissonances cascade into the strings’ lower ranges. The aria’s final sonority barely whispers a third above the tonic G.

How are we to interpret the aria’s postlude? Bauman points out that all previous postludes in the opera have a close rhythmic connection to important phrases in the numbers they close. This one does not.26 Some authors have suggested that the postlude, and other passages that feature the flute in the opera, might represent the mute Tamino’s inner thoughts. Braun and Webster, on the other hand, believe it depicts a devastated Pamina, her pleas unanswered, staggering away.27 Another possibility exists. The postlude pairs instruments that have not partnered one another earlier in the aria – the bassoon and flute, oboe and second violin, viola and cello – which implies that the passage portrays the anguish both characters feel.

Papageno Improvises: “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen”

The Magic Flute’s final aria, “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen,” juxtaposes simplicity with opulence, as poetic structures, standard musical forms, and the skills of the original creators intertwine. Sung by Papageno, the number again inhabits the realm of the Volkston. Formwise, however, “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” is more complex than “Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja,” the character’s first aria. The number features two soloists, not one – the baritone and the magic bells – whose interplay captures both Mozart’s and the original Papageno’s gifts for improvisation.

“Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” alternates between two contrasting sections: a refrain in 2/4 (labeled in Table 6.2 below as A) and verses in 6/8 (labeled B). The poetry, with its built-in refrain, clearly prompts the form: different line lengths and accentuations in the poetry inspire the meter changes. The iambs of the refrain fit neatly into 2/4; the verses, on the other hand, incorporate dactyls (an accented syllable followed by two unaccented ones), a pattern that suggests 6/8. The verses also incorporate two different types of line endings. The first couplet ends with an unaccented syllable, the second couplet with an accented one.

Table 6.2 “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen”: text, translation, rhyme scheme, and scansion

| Music | REFRAIN [Iambs] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A′ |

|

| |

| B′ |

|

|

|

| A′′ |

|

| |

| B′′ |

|

| VERSE 3 Will none grant me love, Then the flames must consume me! But if a feminine mouth should kiss me, Then I would again be healthy. |

[Bold = accented syllable. Center column of letters = rhyme scheme. Underlined letters = accented syllable at end of the poetic line.]

It is perhaps a bit unusual that the aria begins with a refrain. From the outset we hear an unexpected and distinctive tone color. Papageno’s magic bells introduce the simple but catchy tune and then alternate with the voice during both the A and B sections. Like the character’s first aria, the simple but memorable diatonic melody moves within a limited range. Root-position chords and tonic–dominant–tonic progressions dominate the harmony. As the aria progresses, however, the music for the bells becomes more and more florid. During the third repetition of the refrain, for instance, the bells play triplet sixteenths and thirty-second notes while the winds take over the tune; the bell part features continuous sixteenths during the aria’s third and final verse (see Table 6.3).

Table 6.3 “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen”: overview of text and music

| Form | A | B | A′ | B′ | A′′ | B′′ | B′′′ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Text | Lines 1−4 | Lines 5−8 | Lines 1−4 | Lines 9−12 | Lines 1−4 | Lines 13−16 | |

| ABAB | CCDD | ABAB | EEFF | ABAB | GGHH | ||

| Iambs | Dactyls | Iambs | Dactyls | Iambs | Dactyls | ||

| Meter | 2/4 | 6/8 | 2/4 | 6/8 | 2/4 | 6/8 | 6/8 |

| Tempo | Andante | Allegro | Andante | Allegro | Andante | Allegro | Allegro |

| Refrain 1 | Verse 1 | Refrain 2 | Verse 2 | Refrain 3 | Verse 3 | Coda(orchestra alone) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Therefore, the aria melds strophic form with techniques commonly found in keyboard variations on popular tunes, one of Mozart’s specialties. On one level, “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” can be analyzed as a strophic song with a refrain. On another, it can be viewed as a double or alternating variation, with variants that may have grown out of improvisations. Like Mozart, Schikaneder, the original Papageno, was known for his ability for extemporization, including adding strophes to popular arias.28 A letter by Mozart from October 1791 indicates how one performance involved a bit more improvisation than Schikaneder anticipated:

[W]hen Papageno’s aria with the Glockenspiel came on, at that moment I went backstage because today I had a kind of urge to play the Glockenspiel myself. – So I played this joke: just when Schikaneder came to a pause, I played an arpeggio – he was startled – looked into the scenery and saw me – the 2nd time he came to that spot, I didn’t play – and this time he stopped as well and did not go on singing – I guessed what he was thinking and played another chord – at that he gave his Glockenspiel a slap and shouted “shut up!” – everybody laughed. – I think through this joke many in the audience became aware for the first time that Papageno doesn’t play the Glockenspiel himself.29

The aria’s significantly more complex form and the increasingly complicated accompaniment patterns suggest that the character Papageno has grown as a person. His simple rhetoric has been enriched.

Conclusion

The Magic Flute reveals Mozart’s ability to tailor arias not only to singers, but also to the character portrayed and the dramatic situation. As stated earlier, the composer seems to have taken great care to make each of the opera’s arias distinctive. All of the arias contain something unusual and/or extravagant. From the extreme high notes of the Queen’s numbers, to the increasingly florid flourishes of the bells in “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen,” to the panoply of rhythms in “Ach ich fühl’s,” and the full measure of silence in “Dies Bildnis,” each aria stretches the limits of eighteenth-century music in some fashion. As a result, Mozart’s skill and creativity as a composer was and is on display, particularly his ability to compose in diverse styles and create nuanced timbres. Ironically, these arias, so deftly tailored to particular singers’ strengths and to specific dramatic situations, have become some of the most well-known pieces of European art music. Therefore, the arias manifest the power of music on multiple levels, including its ability to endure and speak beyond its original context.

To be invited, as a music analyst, to explore the ensembles and choruses in The Magic Flute is at once both enticing and daunting. The enticement needs little explanation: Who would not rejoice at the chance to spend scholarly time with this work, the music of which is unquestionably as bezaubernd schön as the image of Pamina that launches Tamino’s quest? As for what is daunting – aside from the very challenge to do verbal justice somehow to that Schönheit – part of the answer lies in the fact that the traditional concentration on ensembles, including finales (if not choruses), in analytical accounts of Mozart’s operas has been subjected to harsh criticism, and in high places. Carolyn Abbate and Roger Parker, addressing (again) the opening duet from Le nozze di Figaro, argued more than thirty years ago that “the traditional concentration on ensembles in the Mozart literature may lie simply in professional habits. Writers on musical topics – analysts in particular – tend to turn to a small repertoire of much-analysed pieces whenever they wish to advance a new theory or to demonstrate a new prowess.” And they note that Figaro in particular “has its share of these poor, battered and dismembered exemplars, brutally denied an opportunity to speak out against those who have assailed them.”1 One can at least reply that the ensembles in The Magic Flute have suffered less battering than those in Figaro, and in the Da Ponte operas more generally.

Abbate and Parker go on to suggest, more seriously, that the concentration on ensembles may be laid at the door of late nineteenth-century Mozart reception, and Wagnerism in particular, with its emphasis on unity of music and dramatic action, on the one hand, and purely musical unity, particularly in the shape of large-scale “symphonic” formal structures, on the other. And although eschewing a “call to arms,” they invite consideration of the possibility that “coherence, symmetry or ‘symphonic’ sense” and “absolute correspondence between the unfolding of music, text and stage-action” may not be the only aesthetic criteria against which the Mozartian operatic ensemble may be fruitfully measured.2 They trace the concern with large-scale formal processes, and thus ensembles and finales, back to the work of Alfred Lorenz in the 1920s, as also has James Webster, who notes that what Lorenz initiated was perpetuated in the work of writers such as Joseph Kerman and Charles Rosen.

This brings Webster to the importance given over by Kerman and Rosen to the role of sonata form, “both as a primary constituent of Mozart’s operas and as a criterion of value.”3 Indeed, writing of the chief characteristics of the sonata style in his hugely influential The Classical Style, Rosen could state that “there is no question, however, that Mozart was the first composer to comprehend, in any systematic way, their implications for opera,”4 before going on to develop an extended sonata-form analysis of the Act 3 sextet from Figaro that itself quickly became paradigmatic for later commentators. Yet, as Webster noted, only one of the sixteen nonduet ensembles in the Da Ponte operas “is unambiguously in sonata form!”5 And already by 1996 Tim Carter could report that sonata-form analyses of Mozart ensembles were “coming under threat,” while going on to remark that “the need for an adequate typology of Mozart’s ensemble sonata (and other) forms has not yet been met by the literature.”6 More importantly, perhaps, in comparing Figaro to Così fan tutte, he suggested that Mozart may have become increasingly eager “to explore realistic alternatives to sonata-form organization,” in particular adopting the “looser, more progressive structures” typical of finales to mid-act ensemble movements.7

The twenty-first-century ensemble analyst, then, can no longer take easy refuge in cozy formal strategies of earlier critics, which were already creaking at the end of the twentieth.8 And even if one were to argue that the ensembles in The Magic Flute, a Singspiel, may not best be approached from the formal paradigm of Italian opera buffa, there remains the fact that the dramatis personae of The Magic Flute include unique groupings that materially affect the musical and dramatic conception of several ensembles. Most telling in this respect are the Three Ladies and the Three Boys, who function not as individuals but rather as what might be termed “ensemble characters.” This point was noted as far back as 1956 by Gerald Abraham, in the context of a discussion of Mozart’s preference for the operatic ensemble as a vehicle for the development of dramatic character. Given this purpose, it is not surprising that the composer tended to favor duets and trios, “the combinations which offer him one character to strike against another or two others. When more characters are introduced, problems begin to arise.”9 While in Figaro and Don Giovanni, and excluding finales, the trio texture is exceeded only by one quartet and two sextets, The Magic Flute boasts a quintet in each act, both set for the same characters (namely, Tamino, Papageno, and the Three Ladies). But since the Ladies “amount to only one character, their quintets … are, from the dramatic point of view, essentially trios.”10

The lack of individuality of these two sets of characters is emphasized by the layout of some editions of the score (the Eulenburg version, edited from the autograph by Hermann Abert, being a case in point), in which the first two Ladies and two Boys are scored on one stave while the third (often functioning as what Abraham terms a “pseudo-bass”11) is scored separately. This does not reflect Mozart’s practice in the autograph, in which he routinely provided a separate stave for each part.12 But even in cases such as the Introduction (No. 1), measures 106–19, when the Ladies sing in contrapuntal dialogue with one another, their music, thoughts, and motivation are essentially all one. As for the multisection Introduction as a whole, it might logically be termed a quartet, in that the participating characters are the Three Ladies and Tamino. Even so, the entrance of the Ladies (m. 40) marks the end of Tamino’s vocal contribution: he sings as a soloist and then remains unconscious for the rest of the number, so the four characters never sing together. This is an ensemble – and Introduction – in a quite different sense to that of the action- and character-filled “Introduzione” that opens Don Giovanni.

Tamino’s presence in the Act 1 quintet is similarly compromised. It is notable that following his opening duet with Papageno, lamenting his inability to free Papageno’s padlocked mouth, he is largely silent, except for those passages in which all five parts combine in “moralizing” statements (mm. 54–77, 111–32, 184–203).13 Only after the last of these does Tamino make any contribution to plot development, in asking where he and Papageno are to find Sarastro’s castle; remarkably, the Ladies’ earlier gift of the magic flute (mm. 80–87) – a sine qua non of the entire action – brings forth no individual response from him. A good deal of this “quintet” actually operates as a vocal quartet for the Three Ladies and Papageno; or rather, by Abraham’s logic, it functions as a duet. Similarly, the three constituent characters of the succeeding trio (No. 6) never sing as a trio: rather, the number is constituted of two duets, each tonally closed in G, one for Monostatos and Pamina, the other for Monostatos and Papageno. Even the duets (Act 1, No. 7; Act 2, No. 11) are not occasions for “one character to strike against another”; the Two Priests in “Bewahret euch vor Weibertücken” sing as one, like the Ladies and Boys, while Pamina and Papageno, highly differentiated characters in so many respects though they be, inhabit the same musical and emotional world in “Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen.” This characteristic merging of characters perhaps reaches its apogee in the celebrated “duet” for the Men in Armor in the Act 2 finale (mm. 206–37), where both sing in unison at the octave, their music not even Mozart’s but rather the chorale melody “Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh’ darein.” Indeed, given that the chorale melody was substituted for an alternative melodic line initially sketched by Mozart, one can perhaps speak here not so much of the merging of characters but rather of the anonymization or even suppression of “character” itself.14

The Act 1 and 2 Quintets

The temptation to invoke classical instrumental forms in relation to the ensembles is well illustrated by Erik Smith’s suggestion that the Act 1 quintet “could be described harmonically as a sonata rondo with coda, but not in the normal sense of a recurring melody, for Mozart constantly finds new words and new situations requiring new music.”15 Inasmuch as one cannot deny the overarching I–V–I–vi/modulatory–I tonal scheme, the formal comparison is at least intelligible; but to try to think of this music in terms of sonata rondo does little for one’s experience of its unfolding. In particular, there is lacking the more dynamic transition between sections, and especially between dominant and tonic, that is so characteristic of the sonata style. Smith himself notes the “perfunctory” nature of the shift to V (mm. 33–35) for the beginning of his second section; and one might say the same of the return to I for the beginning of the third, measures 77–81 – essentially the same formula that links the penultimate and final sections of the Introduction, measures 151–53. Mozart’s musical design is clearly indebted to the structure of the libretto: the move to V at measures 34–35 corresponds to the scene shift introducing the Three Ladies, for example; and the “moralizing” statements directed to be sung by “Alle Fünf” in Schikaneder’s libretto evidently dictated the location of the close to Smith’s second and third sections.

Smith’s suggestion that measures 133–71 form a section “in G minor” in which “Papageno is ordered to accompany Tamino” is also open to question, in that it fails to acknowledge the strong turn toward D minor (iii) that sets in as the Ladies tell Papageno what the Queen of the Night requires of him, including the emphatic V pedals with neighboring augmented-sixth harmonies in measures 150–57. Only after the passage has come to a full cadence in D minor with the Ladies’ closing instruction at measure 163 is there a return to the realm of G minor, where Papageno is speaking “für sich” rather than engaging with those around him.16 If one were to defend Smith’s G-minor reading, however, one could point to the detail that as he begins this private speech, Papageno reiterates the VI♯6–V/g progression that concluded his attempted leave-taking of the Ladies at measures 138–39. In this sense, then, the D-minor passage, for all its musical and dramatic prominence, might be considered musically subordinate, or parenthetical, to a more overarching tonal continuity. There will be occasion to return to the notion of parenthesis below.

Schikaneder’s “Alle Fünf” directions in the libretto are absorbed into the close of the second and third sections of Smith’s sonata rondo scheme, as already remarked. But the third such direction (“Silberglöckchen, Zauberflöten”) is treated by Smith as the beginning of his sixth section, which would implicitly function as the “recapitulation” in his sonata rondo scheme. Prior to this, he identifies measures 172–83 as a conspicuously “short E flat section in which Papageno is presented with the glockenspiel.” (Only the beginning is “in” E-flat; by its conclusion, this section has returned to V/I.) It is not difficult to recognize that this event parallels the presentation, earlier and in the tonic B-flat, of the magic flute to Tamino. If we allow our analysis to be guided as much by the construction of the libretto and the events on stage as by abstract, tonic-driven tonal and formal schemes, it makes sense to read the arrival at B-flat in measure 184 as an ending rather than a beginning. And an ending it clearly is, as the words of farewell and the stage direction “Alle wollen gehen” make clear.