Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are defined as a set of exposures to personal abuse, neglect and household dysfunction prior 18 years of age.Reference Felitti, Anda and Nordenberg 1 Based on the landmark work by Felitti and Anda,Reference Felitti, Anda and Nordenberg 1 a graded relationship has been observed between the number of ACEs experienced and adult health risk factors and problems. Extensive research has revealed the within-generation impact of ACEs on children and adults over the lifespan (for review, see McLaughlinReference McLaughlin 2 ). Depression, inflammation and multiple metabolic risk markers such as obesity and diabetes are well-documented outcomes of exposure to ACEs.Reference Danese, Moffitt and Harrington 3 – Reference Schilling, Aseltine and Gore 6 Not only do ACEs significantly increase risk for a variety of mental health problems over the lifespan, they place women at increased risk for prenatal and postnatal depression and anxiety.Reference Leeners, Rath, Block, Görres and Tschudin 7 – Reference Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, Maguire and Jenkins 11 While prenatal and postnatal depression and anxiety have been linked to internalizing (e.g. anxiety, depression) and externalizing (e.g. aggression, hyperactivity) behavioural problems in their children,Reference Thomas, Letourneau, Bryce, Campbell and Giesbrecht 12 , Reference Letourneau, Dennis, Linder and Cosic 13 growing evidence suggests that mothers’ exposure to ACEs may also increase the child’s risk for behavioural problems.Reference McDonnell and Valentino 8 , Reference Fredland, McFarlane, Symes and Maddoux 14 Understanding these associations may help guide intervention to address the steady increase in children’s behavioural problems observed in first world countries,Reference Atladottir, Gyllenberg and Langridge 15 that has recently placed these problems among the top five childhood disabilities.Reference Halfon, Houtrow, Larson and Newacheck 16

In contrast to the extensive evidence of within-generation impacts of ACEs on health, the intergenerational impact of ACEs on child outcomes has received less attention, with most studies examining associations between specific ACEs and children’s behaviour, as opposed to using the omnibus ACE Questionnaire.Reference Felitti, Anda and Nordenberg 1 Indeed, the impacts of mothers’ exposures to specific ACEs such as intimate partner violence and maltreatmentReference Renner and Slack 17 – Reference Stith, Rosen and Middleton 19 in childhood have well-documented consequences for children’s mental health and behaviour. For example, in a sample of at-risk mothers (n=398) recruited from community clinics, mothers’ history of child abuse directly predicted socioemotional problems (e.g. difficultness) in their 6-month-old infants, while household dysfunction indirectly predicted socioemotional problems.Reference McDonnell and Valentino 8 Another study that utilized a measure of childhood adversity that overlapped with the ACE Questionnaire with the exception of questions about childhood physical and emotional neglect, found that more maternal ACEs were associated with more emotional health difficulties in 18-month-old infants. The only intergenerational study (that we could find) that utilized the ACE Questionnaire examined mothers (n=300) who were also victims of intimate partner violence. When their children were 36 months of age, but not 12 or 24 months of age, maternal total ACE score was positively associated with more child behavioural problems, including anxiety, depression, aggressive behaviour, attention problems, and overall scores for internalizing and externalizing behavioural problems.Reference Fredland, McFarlane, Symes and Maddoux 14 However, findings are limited by the concurrent exposure of children to both high-maternal ACE score and intimate partner violence. In summary, studies have not typically utilized broad exposure measures, like the ACE Questionnaire, to assess intergenerational impacts of maternal exposure on their children’s behaviour and the one exception was confounded by concurrent exposed to violence. Thus, the intergenerational impact of ACES on children in community and normative samples remains to be explored.

Specific childhood adversities have also been linked to mental disorders in women, and especially to an increased risk for prenatal and postnatal depression and anxiety. Pregnancy increases the risk for depression and anxiety, which are often co-morbid during the perinatal period.Reference Kingston, Tough and Whitfield 20 – Reference Fricchione 23 The prevalence of prenatal symptoms consistent with major depression is between 7 and 12%, with symptoms often persisting into the postnatal period resulting in rates of postpartum depression between 10 and 15%.Reference Campbell, Cohn, Murray and Cooper 24 – Reference Muñoz, Le and Ippen 26 Findings are worse for anxiety, with prenatal rates between 18 and 25%Reference Falah-Hassani, Shiri and Dennis 27 and postnatal rates between 13 and 40%.Reference Field 28 A systematic review found a positive association between child sexual abuse and depressive symptoms in pregnancy, but an inconsistent association with postnatal depression.Reference Wosu, Gelaye and Williams 9 For example, 25% of women exposed to child sexual abuse became depressed during pregnancy v. less than 2% of women not exposed.Reference Leeners, Rath, Block, Görres and Tschudin 7 Another systematic review identified that a history of abuse predicted both prenatal anxiety and depression.Reference Biaggi, Conroy, Pawlby and Pariante 10

Connections between prenatal anxiety,Reference O’connor, Heron, Golding, Beveridge and Glover 29 , 30 prenatal depression,Reference Field, Diego and Hernandez-Reif 31 – Reference Giallo, Woolhouse, Gartland, Hiscock and Brown 33 postnatal anxietyReference Field 28 and postnatal depression,Reference Giallo, Woolhouse, Gartland, Hiscock and Brown 33 , Reference Grace, Evindar and Stewart 34 with children’s behavioural problems are well-established. Prenatally, depression and anxiety activate the maternal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis with resulting increases in cortisol that pass through the placenta to elevate the level of fetal cortisol concentration and dysregulate HPA axis developmentReference Giesbrecht, Letourneau and Campbell 35 , which is a potential biological mechanism that increases risk of child behavioural problems.Reference Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, Maguire and Jenkins 11 , Reference Waters, Hay, Simmonds and van Goozen 36 , Reference Thomas, Magel and Tomfohr-Madsen 37 Postnatally, mothers with depression characteristically demonstrate diminished sensitivity and responsiveness to infant needs,Reference Moehler, Brunner, Wiebel, Reck and Resch 38 as well as reduced affection during interactions with infants,Reference Field 39 while anxious mothers are less likely to grant autonomy, and more likely to be withdrawn and disengaged.Reference Schrock and Woodruff-Borden 40 These maternal behaviours are a potential psychosocial mechanism by which maternal postnatal anxiety and depression are linked to behavioural problems in children.Reference Letourneau, Tramonte and Willms 41 – Reference Pemberton, Neiderhiser and Leve 44 Taken together, prenatal biological and postnatal social processes may help explain why both externalizing and internalizing behavioural problems are more prevalent among children born to mothers who experience depression and anxiety and may be a mechanism by which maternal ACEs influence behavioural outcomes in the second generation.

A meta-analysis (n=21,709 children) revealed that girls tend to experience more internalizing psychopathology and less externalizing psychopathology than boys.Reference Chaplin and Aldao 45 Consistent with the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis,Reference Wadhwa, Buss, Entringer and Swanson 46 differences in the prevalence and presentation of behavioural problems between boys and girls may be related to early life exposure to factors such as perinatal depression and anxiety.Reference Arnett, Pennington, Willcutt, DeFries and Olson 47 – Reference Chaplin and Aldao 50 Gendered behaviours are shaped by biological and sociocultural influences,Reference Leman and Tenenbaum 51 resulting in different patterns of behaviour for boys and girls.Reference Chaplin and Aldao 45 Boys, compared with girls, display greater difficulty engaging with depressed mothers,Reference Grace, Evindar and Stewart 34 and are therefore more likely to demonstrate maladaptive behaviours and hampered emotional regulation.Reference Carter, Garrity-Rokous, Chazan-Cohen, Little and Briggs-Gowan 52 The increased risk of girls demonstrating internalizing behavioural problems as a result of maternal depression may be explained by gender socialization during early childhood that encourages boys to be more aggressive and girls to be more passive than boys.Reference Goodman, Rouse and Copnnell 53 , Reference Goodman and Gotlib 54 Whatever the reason, any examination of predictors of internalizing and externalizing behaviour needs to consider moderation by child sex.

Social support has long been established as a buffer to maternal perinatal depressionReference Fleming, Klein and Corter 55 , Reference Coburn, Gonzales, Luecken and Crnic 56 and anxietyReference Meritesacker, Bade, Haverkock and Pauli-Pott 57 and as protecting children from the influence of postnatal depressionReference Fleming, Klein and Corter 55 , Reference Herwig, Wirtz and Bengal 58 , Reference Cutrona and Troutman 59 and anxiety.Reference Meritesacker, Bade, Haverkock and Pauli-Pott 57 Low social support is associated with prenatal anxietyReference Norbeck and Anderson 60 and partner support is associated with a lower risk of co-morbid postnatal anxiety and depression.Reference Falah-Hassani, Shiri and Dennis 61 In contrast, low-income has also been implicated in postpartum depressive symptomsReference Coburn, Gonzales, Luecken and Crnic 56 and difficulties with finances and non-white ethnicity have been implicated in co-morbid postnatal depression and anxiety.Reference Falah-Hassani, Shiri and Dennis 61 Thus, it is important to consider the socioeconomic and interpersonal influences on the intergenerational transmission of ACEs to children’s behavioural problems.

In summary, there is a paucity of research examining the intergenerational relationship between maternal ACEs and children’s behavioural outcomes, especially considering the potential mediating mechanisms of maternal symptoms of depression and anxiety or moderation by child biological sex. Thus, our objectives were to determine: (1) the association between ACEs and 2-year-old children’s behaviour, (2) whether maternal symptoms of prenatal and postnatal depression and anxiety mediate the relationship between maternal ACEs and 2-year-old children’s behaviour, and (3) whether the relationships observed in addressing objective 2 are moderated by child sex.

Method

Study design and sample

The data are from the Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition (APrON) longitudinal cohort study designed to examine the relationship between prenatal nutrition, maternal mental health, and child neurodevelopment and mental health. A detailed description of the APrON study design and methods has been previously published.Reference Kaplan, Giesbrecht and Leung 62 Briefly, a community sample of pregnant women residing in Alberta, Canada was recruited from maternity care and ultrasound clinics. Women were eligible if they had a gestational age less than 27 weeks and were 16 years of age or older. Women were not eligible if they were unable to complete questionnaires in English or were planning to move out of the study region within the next 6 months. Participants provided informed consent before participation in the study. The study was approved by both the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (ID E22101/REB14-1702) and the University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Biomedical Panel (Pro00002954).

Measures

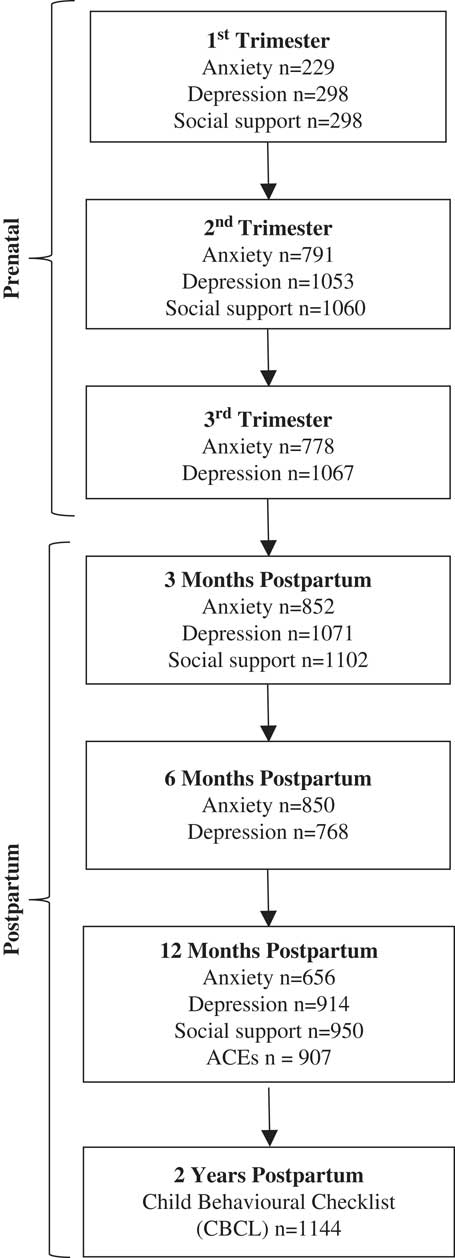

Data were collected in each trimester of pregnancy and 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-months postnatal. Data collection occurred between May 2009 and February 2015. Figure 1 presents the number of participants who provided data at each time point. The analytic sample was constrained to the sample of 907 with complete data on the ACE Questionnaire.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram for study time points and measurements. ACEs, adverse childhood experiences.

Exposure

Maternal ACEs

The ACEs QuestionnaireReference Felitti, Anda and Nordenberg 1 is a 10-item self-report measure that examines cumulative adverse experiences from birth to 18 years of age. ACE items assess five aspects of child maltreatment including physical, verbal or sexual abuse, and physical or emotional neglect. An additional five items assess family factors including domestic violence, marital dissolution, parental addiction, mental illness or incarceration. Responses are scored as ‘0=no’ or ‘1=yes’ with total scores ranging from 0 to 10, and higher scores indicating a greater accumulation of ACEs. Murphy et al.Reference Murphy, Steele and Dube 63 demonstrated excellent convergent validity and internal consistency (α=0.88) of the ACE Questionnaire. In the current study, total ACEs ranged from 0 to 9. Because scores above 4 occurred infrequently, and in keeping with previous studies (e.g. Anda et al.Reference Anda, Felitti and Bremner 64 ), scores above 4 were recoded to a value of 4 so that the final ACEs scores ranged from 0 to 4.

Mediators

Measures of maternal anxiety and depression were administered to mothers in each trimester of pregnancy and at 3-, 6-, and 12-months postpartum. These repeated measures were used to construct pre- and postnatal latent variables for anxiety and depression.

Maternal depressive symptoms

The Edinburgh Depression Scale (EDS)Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky 65 is a 10-item, likert-type scale with total scores that can range from 0 to 30, and higher scores indicating more severe symptoms of depression. The EDS correlates well with other measures of depressionReference Brouwers, van Baar and Pop 66 and has excellent internal consistency, Cronbach’s α=0.87.Reference Huizink, Mulder, de Medina, Visser and Buitelaar 67

Maternal anxiety symptoms

The Symptoms Checklist-90-Revised QuestionnaireReference Derogatis 68 is a 90-item self-administered questionnaire measuring psychological problems and symptoms of psychopathology. For this study, only the 10-item anxiety subscale was administered. Scores across items are summed and can range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater distress. Research supports the convergent validityReference Dinning and Evans 69 and internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.81)Reference Vallejo, Jordán, Díaz, Comeche and Ortega 70 of this anxiety subscale.

Outcome measures

Child internalizing and externalizing behaviour

The Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) for children ages 1.5–5Reference Achenbach and Rescorla 71 is a 100-item parent report questionnaire measuring parent perceptions of their child behaviour within the preceding 2 months. The CBCL examines internalizing problems (emotionally reactive, anxious/depressed, somatic complaints and withdrawn), and externalizing problems (aggressive behaviour, attention problems). Internalizing scores can range from 0 to 72 and externalizing scores from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating greater problematic child behaviours. The CBCL has excellent convergent validityReference Achenbach and Rescorla 71 and displays high internal consistency(α=0.87 and 0.89 for the internalizing and externalizing problem scales, respectively).Reference Kristensen, Henriksen and Bilenberg 72 Maternal report of children’s behaviour was measured at 2 years of age.

Moderator measure

Child sex was based on maternal report at birth.

Covariates

Socioeconomic status and sociodemographics

Variables for maternal self-reported ethnicity, education and household annual income were obtained at the first study visit (first or second trimester). These variables were standardized before inclusion in all models. Child age at the 2 year assessment was also included in all models.

Maternal social support

Maternal perception of social support received during pregnancy and at 3-, and 12-months postpartum was assessed with the Social Support Questionnaire,Reference Michalos 73 a four-item measure of emotional, affirmational, informational and instrumental support available. Responses were scored as ‘Yes=1’ or ‘No=0’ and summed. Thus, total scores ranged from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating higher levels of support from family, friends and the community. The internal consistency for this measure is strong (α=0.81).Reference Michalos 73

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic characteristics of women and children who participated in the 2-year follow-up and all model variables. To address objective 1, Pearson correlations were conducted. To address objective 2 latent path analyses were conducted in Mplus Version 8 74 to test the indirect (mediation) effects of maternal ACEs on child internalizing and externalizing behaviours via maternal anxiety and depression. Latent path analysis maximized the use of the available longitudinal repeated measures and enabled the examination of mediation and moderation.Reference Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal 75 Mediation models were estimated using maximum likelihood and tests of indirect effects were evaluated using bias corrected 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals (CI) with 5000 resamples. This approach accounts for the non-normality of the indirect effects.Reference Hayes 76 Indirect effects are supported when the CI does not contain 0. All results reported are standardized estimates and included the following covariates selected a priori and collected at time of behavioural assessment: maternal education, ethnicity and social support, household income, and child age and biological sex (when not included as a moderator as in objective 3). To address objective 3, multi-group analyses were conducted to determine whether there were differences between males and females with regard to the effects of maternal ACEs on child behaviour. The Satorra–Bentler scaled χ2 difference testFootnote 1 (as described at www.statmodel.com/chidiff.shtml) was used to determine whether the indirect effects differed by child sex. Significant differences between models constrained to be the same for both sexes and models that were estimated freely for each sex provide evidence of moderation. Goodness of fit for models was assessed using the following criteria: χ2 test>0.05, Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI)⩾0.90, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) close to or below 0.05, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR)<0.05.Reference Bentler 77 , Reference Lt and Bentler 78 Although the χ2 test is not a sensitive measure of model fit with large samples,Reference Bearden, Sharma and Teel 79 we report it for full disclosure.

Results

Descriptive findings

The mean age of mothers was 32.2 years. Most were married or in a common-law relationship, had some post-secondary education, had family income ⩾ $70,000, were born in Canada, and were first time mothers (see Table 1). The mean age of children was 24.3 months, and more were male. Table 2 provides descriptive data on responses to the ACE Questionnaire and Table 3 provides descriptive data on the other predictors and outcomes. Missing data were less than 16.5% across all variables.

Table 1 Socio-demographics of study participants (n=907)

Table 2 Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) Questionnaire scores (n=907)

Table 3 Descriptive data on predictors and outcomes (n=907)

pp, postpartum.

Because exposure information was available from only 907 mothers, we conducted comparisons between this sample and the remaining members of the cohort for which other data were available (n=237). Women included in the analysis were more likely to be married (97.5 v. 94.5%, χ2 (1)=4.8, P=0.03) and White (86.9 v. 81.9%, χ2 (1)=3.9, P=0.05), but did not differ on education, annual household income, number of previous children, immigration to Canada, age, anxiety, depression or social support (all P’s>0.05).

Objective 1: association between maternal ACES and child behaviour.

Table 4 presents the bivariate correlations between the child behavioural outcomes and ACEs total and individual items scores, revealing that only externalizing behaviours are significantly correlated (r=0.08) with ACEs total scores. One ACE item, on emotional neglect, was significantly correlated with internalizing behaviour (r=0.10), while two ACE items, on emotional neglect (r=0.10) and sexual abuse (r=0.09), were significantly correlated with externalizing behaviour.

Table 4 Correlations between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and child behaviour (n=907)

*P-value <0.05.

Objective 2: mediation by maternal depression and anxiety

Prenatal mediation of externalizing behaviour

The prenatal mediator model for child externalizing behaviours had good fit (see Table 5), accounting for 10.1% of variance in externalizing behaviour at 2 years. Unique indirect effects of maternal ACEs on child externalizing behaviours were not supported for either depression, 95% CI [−0.001–0.055], or anxiety, 95% CI [−0.010–0.085]. However, the 95% CI for the combined effects of prenatal depression and anxiety, [0.017–0.089], indicated that depression and anxiety together are associated with the effects of maternal ACEs on children’s externalizing behaviours. Maternal exposure to ACEs was positively associated with both prenatal depression and anxiety, which were in turn positively associated with the child externalizing behaviour. Child sex was not reliably associated with externalizing behaviour, 95% CI [−0.022–0.101], indicating no overall difference in externalizing behaviour for boys and girls.

Table 5 Overall indirect effects of maternal adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on externalizing and internalizing behaviour

CI=confidence interval; RMSEA=root mean square error of approximation which is a parsimony-adjusted index in which values closer to 0 represent a good fit and cut-off representing good fit is RMSEA<0.08; TLI=Tucker–Lewis Index. A TLI of 0.95, indicates the model of interest improves the fit by 95% relative to the null model. Cut-off for good fit is TLI ⩾0.95; SRMR=standardized root mean square residual which is the square-root of the difference between the residuals of the sample covariance matrix and the hypothesized model. Cut-off for good fit is SRMR <0.08. Covariates included were: maternal education, ethnicity, social support, household annual income, and child age and sex.

Prenatal mediation of internalizing behavior

The model for child internalizing behaviour had good fit (see Table 5), accounting for 10.9% of variance in internalizing behaviour at 2 years. A unique indirect effect of maternal ACEs on child internalizing behaviours was supported for anxiety, 95% CI [0.022–0.143], but not for depression, 95% CI [−0.033–0.020]. Maternal exposure to ACEs was positively associated with maternal prenatal anxiety, which was positively associated with child internalizing behaviour. There was also a combined indirect effect of prenatal depression and anxiety, 95% CI [0.030–0.116]. Child sex was associated with internalizing behaviour, 95% CI [−0.149 to −0.025], indicating that boys had lower internalizing scores than girls.

Postnatal mediation of externalizing behavior

The postnatal model for child externalizing behaviour had good fit (see Table 5), accounting for 10.4% of variance in externalizing behaviour at 2 years. A unique indirect effect of maternal ACEs on child externalizing behaviour was supported for depression, 95% CI [0.007–0.076], but not for anxiety, 95% CI [−0.003–0.050]. Maternal exposure to ACEs was positively associated with maternal postnatal depression, which was positively associated with the child externalizing behaviour. There was also a combined indirect effect of postnatal depression and anxiety, 95% CI [0.010–0.078].

Postnatal mediation of internalizing behaviour

The postnatal model for child internalizing behaviour had good fit (see Table 5), accounting for 10.3% of variance in internalizing behaviour at 2 years. A unique indirect effect of maternal ACEs on child internalizing behaviour was supported for depression, 95% CI [0.001–0.063], but not for anxiety, 95% CI [−0.018–0.066]. Maternal exposure to ACEs was positively associated with maternal postnatal depression, which was also positively associated with children’s internalizing behaviour. There was also a combined indirect effect of depression and anxiety, 95% CI [0.015–0.080].

Post-hoc analyses of mediator models

The patterns of results observed for mediator models raised further questions that we addressed in post-hoc analyses. Specifically, the model for prenatal exposures and child externalizing behaviour found that neither prenatal anxiety nor depression had unique effects, although they did have combined effects. Therefore, we ran two additional models with prenatal anxiety and depression as separate mediators to determine if either had individual effects when the other was not included in the model. The models for prenatal anxiety and depression were both supported, 95% CI [0.018–0.090] and [0.014–0.059], respectively, suggesting that although prenatal anxiety and depression are not unique mediators of maternal ACEs on child externalizing behaviour, they each contribute to transmitting the effects of maternal ACEs to child externalizing behaviour, with considerable overlap in their effects.

In addition, for child internalizing behaviour, we ran an additional model with the two previously identified mediators, prenatal anxiety and postnatal depression, to determine if either was a unique mediator after controlling for the other. The indirect effects of ACEs via postnatal depression was supported, 95% CI [0.003–0.065], but the pathway via prenatal anxiety was not [−0.008–0.088], suggesting that postnatal depression uniquely contributes to the effects of maternal ACEs on child internalizing behaviour even after accounting for the effects of prenatal anxiety.

Objective 3: moderation by child sex.

In multi-group analyses, all four mediation models had significantly better model fit when child sex was included as a grouping factor, suggesting that the mediator models may be moderated by child sex: prenatal model for externalizing (unconstrained χ2(78)=81.4; constrained χ2(108)=251.8; χ2 diff(30)=154.9, P<0.001); prenatal model for internalizing (unconstrained χ2(78)=72.4; constrained χ2(108)=247.9; χ2 diff(30)=158.7, P<0.001); postnatal model for externalizing models (unconstrained χ2(78)=88.4; constrained χ2(108)=269.5; χ2 diff(30)=160.6, P<0.001); and postnatal model for internalizing (unconstrained χ2(78)=88.4; constrained χ2(108)=269.5; χ2 diff(30)=160.6, P<0.001). Accordingly, all mediator models were re-estimated with child sex as a grouping factor. Model fit for all models was excellent, RMSEA=0.03 [0.01, 0.05], TLI=0.97–1.0, SRMR=0.03–0.04, with the exception of χ2, which had P<0.05 for the postnatal models.

Prenatal model of externalizing behaviour

Similar to what was observed for the model without grouping by sex, all 95% CIs for the indirect effects of ACEs on externalizing behaviour included 0: girls via prenatal depression [−0.006–0.067], and prenatal anxiety, [−0.018–0.107], and boys via prenatal depression, [−0.026–0.067], and prenatal anxiety, [−0.017–0.163]. However, when the effects of the two mediators were combined, the model did support a moderated mediator effect for boys 95% CI [0.018–0.144], but not for girls, [−0.003–0.099].

Prenatal model of internalizing behavior

The 95% CI for the unique indirect effect of ACEs on internalizing behaviour via prenatal depression was not supported for girls [−0.036–0.029] or boys [−0.079–0.025]. In contrast, the 95% CI for prenatal anxiety supported a unique mediating effect of anxiety for boys [0.035–0.265], but not girls [−0.001–0.140]. As shown in Fig. 2, maternal exposure to ACEs was associated with increased prenatal anxiety, which in turn was related to increased internalizing behaviour in boys. The combined indirect effects of prenatal anxiety and depression on internalizing behaviour were significant for both girls [0.002–0.111] and boys [0.045–0.209].

Fig. 2 Standardized parameter estimates for the moderated mediator model for child internalizing behaviour. Parameter estimates are for girls and boys (in brackets). Non-significant associations are designated as NS, otherwise all associations were significant at P<0.05. The curved line with double-headed arrows represents the correlation between latent variables. For simplicity, covariates were not included in the figure but were included in the models: maternal education, ethnicity, and social support, household income, and infant age at behavioural assessment.

Postnatal model of externalizing behaviour

The 95% CI for the indirect effect of ACEs on externalizing behaviour via postnatal depression was supported for boys, [0.002–0.113], but not girls [−0.009–0.110]. There was no support for postnatal anxiety as a unique mediator for either girls [−0.087–0.043], or boys, [−0.048–0.084]. Furthermore, the combined indirect effect of postnatal anxiety and depression on externalizing was not significant for girls [−0.036–0.076], but was significant for boys [0.011–0.111]. As shown in Fig. 3, maternal exposure to ACEs was associated with increased postnatal depression, which was related to increased externalizing behaviour in boys. Although the individual path from maternal depressive symptoms to externalizing behaviour in boys was only marginally significant (β=0.23, P=0.069), the indirect effect was significant for boys, as described above.

Fig. 3 Standardized parameter estimates for the moderated mediator model for child externalizing behaviour. Parameter estimates are for girls and boys (in brackets). Non-significant associations are designated as NS, otherwise all associations were significant at P<0.05, with the exception of the pathway from maternal depressive symptoms to externalizing behaviour for boys for which P=0.07. The curved line with double-headed arrows represents the correlation between latent variables. For simplicity, covariates were not included in the figure but were included in the models: maternal education, ethnicity, and social support, household income, and infant age at behavioural assessment.

Postnatal model of internalizing behaviour

None of the moderated mediator models for internalizing behaviour was supported, despite the fact that when children were not grouped by sex there was a significant indirect effect for depression. The indirect effects of postnatal anxiety and depression for girls were, [−0.066–0.068] and [−0.006–0.100], and for boys [−0.011–0.136] and [−0.016–0.096], respectively. However, the combined indirect effect of anxiety and depression was significant for boys, 95% CI [0.025–0.128], but not for girls, 95% CI [−0.029–0.072]. Similar to other models, ACEs were associated with increased postnatal anxiety and depression, which subsequently were associated with increased internalizing behaviour in boys.

Discussion

This study builds on emerging research examining the intergenerational effects of ACEs and mechanisms related to behavioural psychopathology. The objectives of this study were to examine first, the impact of maternal ACEs on child behaviour at 2 years of age, second, maternal depression and anxiety as mediators, and third, the potential for moderation of associations by child sex. Direct associations were observed between total maternal ACE scores and children’s externalizing behaviours. Overall, we observed a positive relationship between the number of maternal ACEs and both children’s externalizing and internalizing behavioural problems via both maternal anxiety and depression. Even after controlling for relevant social and sociodemographic characteristics, mothers’ exposure to ACEs increased their symptoms of depression and anxiety during the prenatal and postnatal periods, which consequently increased the expression of children’s behavioural problems. Exposure timing effects and sex differences were observed.

ACEs predicted externalizing behaviour only in boys. The only unique mediator was postnatal depression, however, the combined effects of maternal anxiety and depression, both in the prenatal and postnatal periods, were significant mediators of ACEs on externalizing behaviour in boys. For internalizing behaviour, again the findings were primarily for boys. The only unique mediator was prenatal anxiety. The combination of prenatal anxiety and depression mediated the effects of ACEs on internalizing behaviour for both girls and boys and the combination of postnatal anxiety and depression also mediated the effects of ACEs on internalizing behaviour in boys. The findings also suggest a relatively greater impact of prenatal and postnatal anxiety and depression for boys compared to girls in both internalizing and externalizing behaviours. Effects for girls were observed only for internalizing behaviour and only when the effects of prenatal depression and anxiety were combined. Other research suggests that effects of early adversity on girls, particularly in internalizing behaviours such as anxiety, may be observable at later ages in boys.Reference Roza, Hofstra, van der Ende and Verhulst 80

While our findings agree with other studies showing maternal ACEs increased the propensity for child behavioural problems,Reference Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, Maguire and Jenkins 11 , Reference Fredland, McFarlane, Symes and Maddoux 14 our novel examination of sex differences revealed that maternal postnatal depression or anxiety did not mediate the relationships between maternal ACEs and internalizing problems among girls (although there was an effect for prenatal anxiety and depression). This is in contrast to other research showing that maternal postnatal anxiety and depression are associated with internalizing symptoms in girls.Reference Essex, Klein, Cho and Kraemer 81 Taken together, the findings suggest that maternal depression and anxiety may be important predictors of internalizing behaviour in girls but they do not appear to be involved in transmitting the effects of maternal ACEs to girls. Nevertheless, our finding that prenatal depression and anxiety together do mediate the effect of ACEs on internalizing in girls suggests that the timing of exposure may be an important determinant of outcome in girls. This did not appear to be the case for boys, where both prenatal and postnatal depression and anxiety were involved in transmitting the effects of ACEs to both internalizing and externalizing behaviour. In the context of exposure to ACEs, it appears that boys are vulnerable to both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology via prenatal and postnatal distress, while girls appear vulnerable in the prenatal period only, and only with respect to internalizing psychopathology. In general, these findings support the premise that boys are more vulnerable than girls to the intergenerational transmission of ACEs via maternal distress.Reference Schore 82

The transmission of maternal ACEs to childhood vulnerability for developmental psychopathology may stem from sustained perturbations of stress regulatory systems that persist from early life into childhood and adulthood.Reference Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, Maguire and Jenkins 11 Childhood is a developmentally salient period,Reference Holzman, Eyster and Tiedje 83 during which cumulative exposure to adversities may participate in developmental programming of biological,Reference McLaughlin 2 emotionalReference Cloitre, Stovall‐McClough, Zorbas and Charuvastra 84 and socialReference Al Odhayani, Watson and Watson 85 responses to stress. For some women, such developmental programming persists into the childbearing years where its effects predispose women to develop depression or anxiety during the major life changes that occur as a consequence of childrearing. Depression and anxiety may operate together to affect the growing fetus via biological mechanismsReference Giesbrecht, Poole, Letourneau, Campbell and Kaplan 86 or the growing child via alterations in caregiver–child interaction,Reference Letourneau, Dennis and Benzies 42 with sex differences in vulnerability as proposed by the DOHaD hypothesis.Reference Wadhwa, Buss, Entringer and Swanson 46 So, for both girls and boys, whose mothers were exposed to ACEs, prenatal exposures to the biological substrates of maternal distress connotes vulnerability to behavioural psychopathology. Postnatally, the observation that infant girls display greater responsiveness to social stimuli than boys (e.g. more eye contact and orientation to faces and voices),Reference Alexander and Wilcox 87 suggests a potential protective mechanism for girls by improving the quality of caregiver–child relationship.

Our findings corroborate previous research which demonstrated that maternal depression during the prenatal and postnatal periods negatively impacts children’s behavioural outcomesReference Field, Diego and Hernandez-Reif 31 , Reference Avan, Richter, Ramchandani, Norris and Stein 88 , Reference Choe, Olson and Sameroff 89 and extends this understanding to include the effects of maternal anxiety. The findings also broaden our understanding of the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs, specifically via the effect of maternal depression and anxiety on child behaviour, paying special attention to sex differences associated with perinatal exposures. These findings are also in line with previous work which demonstrated increased externalizing behaviours among boys as a result of prenatal and postnatal maternal distress.Reference Arnett, Pennington, Willcutt, DeFries and Olson 90

Strengths and limitations

The prospective nature of our study design and sample size are significant strengths that allow us to evaluate the plausibility of causal pathways from maternal early life adversity to offspring behaviour and to control for relevant covariates while testing for sex differences. To our knowledge, the findings are the first to formally test indirect (mediator) effects of ACEs on children’s behaviour via maternal depression and anxiety experienced in the prenatal or postpartum periods. Moreover, research to date utilized high-risk samples (e.g. mothers affected by concurrent or recent intimate partner violence),Reference Fredland, McFarlane, Symes and Maddoux 14 assessed more limited conceptions of behaviour (e.g. socioemotional functioning),Reference McDonnell and Valentino 8 , Reference Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, Maguire and Jenkins 11 used less rigorous measures of behaviour,Reference McDonnell and Valentino 8 , Reference Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, Maguire and Jenkins 11 and did not examine the moderating influence of sex differences. Our study employed a community sample, rigorous, well-regarded measures of both internalizing and externalizing behaviours, and a well-designed examination of sex differences.

Nevertheless, several limitations constrain interpretation and generalizability of the findings. First, the sample represents a relatively low-risk sociodemographic population. Mothers were predominantly White, university educated, and had high income. The generalizability of these findings may therefore be limited to middle and upper class families. Second, the measurement of maternal ACEs is retrospective and prone to recall bias; however, evaluations of repeated administrations of the ACE Questionnaire reveal it to be reliable.Reference Dube, Williamson, Thompson, Felitti and Anda 91 , Reference Hardt and Rutter 92 Third, our measures may have common source variance owing to the fact that mothers self-reported on their ACEs, self-reported on their depression and anxiety, and reported on their children’s behaviour. Child behaviour assessment relied exclusively on maternal report, and others may have different perceptions of behaviour problems in the children. The APrON data set does not possess information on mental health history which would have been ideal to consider in modelling. Fourth, despite temporal ordering of the exposure, mediator and outcome variables, these data remain correlational and therefore cannot conclusively establish causality. Finally, despite the inclusion of relevant covariates, residual confounding may persist.

Conclusion

This study provides new evidence regarding the role of maternal mental health in the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs on internalizing and externalizing behaviour in 2-year-old boys and girls. The study shows that adverse experiences before the age of 18 are associated with increased symptoms of maternal depression and anxiety during both the prenatal and postnatal periods, and this increase in symptoms is associated with increased symptoms of behavioural problems in children, especially in boys. Overall, the current study suggests that children of mothers who experienced ACEs may be at heightened risk for developmental psychopathology. Mental health interventions for mothers with a history of ACEs represents an important future research objective because it has the potential to prevent or reduce the intergenerational cascade that perpetuates cycles of stress.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participants of the APrON study and the members of the APrON study team whose individual members are B.J. Kaplan, C.J. Field, D. Dewey, R.C. Bell, F.P. Bernier, M. Cantell, L.M. Casey, M. Eliasziw, A. Farmer, L. Gagnon, G.F. Giesbrecht, L. Goonewardene, D.W. Johnston, L. Kooistra, N. Letourneau, D.P. Manca, J.W. Martin, L.J. McCargar, M. O’Beirne, V.J. Pop and N. Singhal.

Financial support

This work was supported by Alberta Innovates – Health Solutions (AIHS), the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation, and the Alberta Children’s Hospital Chair in Parent-Infant Mental Health awarded to the first author.

Conflicts of interest

All of the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation, the Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement on the Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and has been approved by the institutional committees at the University of Calgary and the University of Alberta.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S2040174418000648