In his classic work on currency, Nurkse argues that ‘the post-war history of the French Franc up to the end of 1926 affords an instructive example of completely free and uncontrolled exchange rate variations’.Footnote 1 According to Friedman,Footnote 2 Nurkse only uses this example to defend his thesis on the potentially destabilising effect of currency speculation. More recently, Eichengreen argues in relation to the French episode that ‘A notable feature of post-war international money arrangements was the freedom of the float. As a rule, central banks did not intervene in the foreign-exchange market. The first half of the 1920s thus provides a relatively clean example of a floating exchange rate regime.’Footnote 3 For Eichengreen, ‘the French authorities only intervened in the exchange market for two months, in the spring of 1924 and during the second half of 1926’.Footnote 4

These two episodes became well known following Jeanneney'sFootnote 5 and Debeir'sFootnote 6 writings on the former and Governor Moreau'sFootnote 7 on the latter. Following Eichengreen's empirical investigations of the impact of speculating on stability,Footnote 8 these authors developed the hypothesis of a one-to-one relationship between the monetary base and exchange rate during the second half of 1924 and the first half of 1926. Frenkel, who uses the French example to check the PPP relationship, makes exactly the same assumption in that he assumes, de facto, an absence of endogeneity in variations of the monetary base.Footnote 9

Our study of the archives of the Bank of France and the French Ministry of Finance, as well as a thorough examination of the exchange rates (FRF/USD) and (FRF/GBP) during the 1920s, reveals that the French authorities intervened on three other occasions: once between November and December 1924, again from June to October 1925 and also between May and June 1926. We will here analyse the motives, means and consequences of the actions as systematically as possible. Even if these interventions seem to be non-sterilised, the fact that the French authorities maintained the stability of nominal interest rates to facilitate the sustainability of the public debt leads us to bypass their effect on portfolios.Footnote 10 However, their direct influence on exchange rates can be noted and our attention will therefore be focused on their signalling effects.Footnote 11

Far more than contemporary studies, dedicated to interventions during the 1980s and 1990s, this original contribution encounters the problem of state secrecy surrounding the means of action of the monetary authorities and is therefore exploratory. However, from these first direct actions, as well as some other abortive attempts, several lessons can be drawn about the effectiveness of such an action in a ‘modern environment’ where the exchange rate regime is forced, international capital mobility is relatively high,Footnote 12 and numerous speculative attacks against weak currencies take place.Footnote 13 Aftalion, very early, underlined the key role played by speculators in the modification of the market equilibrium and the importance of new information in the formation of exchange rates.Footnote 14 He also identified some exuberant behaviour, describing the mechanisms of what we today call ‘bubbles’.

From an economic point of view, the French episode of the 1920s shows that the concept of credibility is essential when considering the effectiveness of an intervention. Only a credible intervention can send a signalling effect able to obtain a reversal of the dominant opinion in a market where exchange rates are below their ‘equilibrium level’. This credibility depends more on the perception the operators have of the authorities’ financial and monetary intentions than on the means which are actually used. This opinion is shared in contemporary papers on the subject.Footnote 15

From a strictly historical perspective, we show that the main role of the French monetary authorities in the regulation of the foreign-exchange market was determined by the fact that decisions taken about the means of action to be used dictated the choice of the future monetary regime. Finally, the reality of these interventions invites us to challenge the conventional view of the existence of a pure floating regime in France during the mid 1920s.

I

In the early 1920s, the authorities in charge of exchange rate policy were bicephalous, with a clear asymmetry between the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of France. Indeed, until the Monetary Reform of 7 August 1926, the Bank of France was not empowered to intervene in the market either directly or alone. In addition, before 16 October 1926, the Bank of France did not have a foreign-exchange department. If the Bank wanted to intervene, prior approval from the Ministry of Finance was necessary: decisions on exchange rate policy were governmental and therefore took time, given their political nature. Hence, the limits of the autonomy of the Bank of France in the post-World War I period can be observed. It should nonetheless be noted that the Ministry of Finance also needed the Bank of France, as it was extremely difficult to obtain foreign exchange (necessary for any defensive action) without the ‘golden guarantee’ of the issuing institution, especially during the period of depreciation and up until the reversal of the situation in July 1926. Technically speaking, all market intervention had to be led by duly mandated commercial banks (at this time, most frequently the Banque Lazard, but also Société Générale and Crédit Lyonnais). This deprived the authorities of direct contact with effective management of the foreign-exchange market.

The well-known episode of March 1924 illustrates, among other things, the fact that the success of intervention crucially depended on cooperation between the different institutions involved in monetary affairs. After two months of procrastination,Footnote 16 those in charge of interventions at the Treasury and the Banque Lazard succeeded in convincing Poincaré's government of the necessity of action: the spectre of the collapse of the Deutshmark convinced them of the necessity to respond to the speculative offensive against the Franc. The Bank of France agreed to engage part of its gold reserves against two loans: one of £4 million negotiated on 9 March with four British banks, the other of $100 million from the Morgan bank. The latter was subordinated by the French government's commitment to press the Senate to adopt a rapid vote for measures of budgetary austerity. In this way, the authorities hoped to obtain a lasting reversal of the situation.

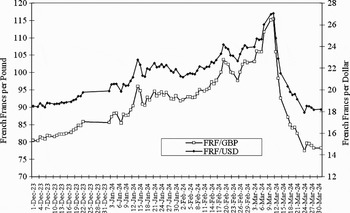

The intervention began on Monday, 10 March, with only the British loan and a small amount of currency at the disposal of the Bank of France. Each morning, bankers and officials from the Treasury and the Bank of France conferred and came up with a plan. As shown in Figure 1, this action resulted in a reversal of the trend on 12 and 13 March, when international speculators learnt of the up-coming vote on financial measures and the opening of the Morgan loan. In Paris, on Friday, 14 March, sterling and the US dollar were worth 92.6 FRF and 21.5 FRF respectively, whereas on Monday, 10 March, they had been worth 111.2 and 26.9 FRF, respectively. At the end of the same month, these two currencies were only worth 78.3 FRF and 18.2 FRF respectively. The French Franc had regained almost one-third of its nominal value. Less than half of the Morgan loan had been enough to obtain this result and at the end of March the Ministry had already bought back enough currency to pay back two of the British loans. The Bank of France used the opportunity to create foreign-exchange reserves.Footnote 17 The operation was a great success.

Figure 1. FRF/GBP and FRF/USD spot exchange rates (December 1923 − March 1924)

II

In June 1924, the newly appointed Herriot government (left-coalition) stated its intention to continue with the deflationary policy that had been in place since the 1920 François-Marsal Convention. To obtain appreciation of the French currency, the circulation of notes had to be maintained, up to the ceiling of 41 billion Francs. The figure for the circulation of notes, published every Thursday, was an indicator of the government's monetary credibility. However, this variable illustrated modifications of the government's financial policy (through advances obtained from commercial banks), and it was heading towards the statutory limit. In reality, until April 1925, the Bank of France used to falsify its weekly statements to conceal the fact that the legal limit had been exceeded. This is the affair of the so-called ‘false statements’ of the Bank of France (see Appendix 1). Public knowledge of this situation would have led to the definitive failure of French monetary policy and a loss of all hope for the revaluation of the Franc. These facts can be considered as an instance of the type of domination of monetary policy by budgetary policy, as described by Sargent and Wallace.Footnote 18

According to Philippe of the Banque Lazard, the general secretary of the Bank of France, Aupetit, first had the idea of market action in November 1924.Footnote 19 The Bank of France sought to bring down note circulation by the following mechanism: the appreciation of the Franc would have a positive impact on public confidence and if the latter would allow a general decrease in prices via the reduction of import prices, it would furthermore incur a drop in ‘monetary demand’. Herriot accepted this scheme; he presumably thought it would restore public confidence at a time when his government was issuing bonds. The action began two weeks after the launch of Clementel's loan and finished a few days before its close.

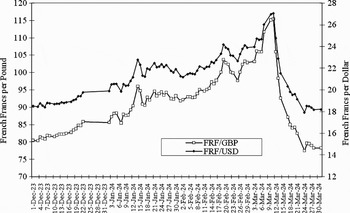

The Banque Lazard intervened on behalf of the French monetary authorities from the end of November 1924 by essentially using the sterling and dollars collected by the Central Bank after the March intervention, and without having to use the Morgan funds. Figure 2 shows the consequences of the operation: sterling was worth 87.83 FRF on 26 November, whereas by 2 December it had fallen to under 85 FRF. The dollar, on the other hand, which had been falling slowly, then very dramatically dropped: on 26 November it was worth 18.95 FRF and by 4 December it had dropped to 18.16 FRF. However, at the beginning of December, foreign-exchange demand grew stronger as the market clearly intended to take advantage of the fall in exchange rates. The Bank of France − lacking the means − had to take the decision to stop the operation from 12 December very quickly, as sterling and the dollar were worth what they had been prior to intervention.

Figure 2. FRF/GBP and FRF/USD spot exchange rates (October–December 1924)

In March 1925, further intervention was again contemplated. The idea, this time, came from the minister of finance, E. Clementel; according to him, the targeted drop in the rates of the dollar and sterling would allow ‘a marked remission of the amount of notes in circulation in a short time’.Footnote 20 The deflationary inspiration was the same. Clementel put 30 million dollars at the disposal of the Bank of France, 15 million taken from the Morgan funds and the other 15 million from a recent transfer between the Treasury and the Bank. For the government, this intervention was a way of obtaining a little respite and a way of leaving the scene honourably if note circulation had effectively dropped below the ceiling. Robineau waited until 12 March before formulating this request to the Board of the Bank. He undoubtedly delayed, but the next day the Board noted that confidence in the Franc was lower than it had been in March 1924. With 30 million dollars, the Bank was only able to contain the depreciation of the Franc, and the action could not be justified. The Bank was also against a large-scale operation: ‘the effectiveness of such operations remains always uncertain, given that the French Franc is grappling with the interests and strengths of the whole world. It is even more doubtful today and will be even more preoccupying, as long as the state of the Treasury remains as it is, despite the upcoming issue of a contribution check and opinion will clearly not be oriented towards the revaluation of the Franc through the government's budgetary program.’Footnote 21 On the impulse of Regent Wendel (member of the opposition to the Cartel) the Bank of France now waited patiently for the revelation of its own false statements in order to hasten the fall of Herriot's government.

III

The operation undertaken from June to October 1925, newly revealed here, was the result of a personal initiative taken by the minister of finance, J. Caillaux. The Bank of France and the Banque Lazard were not in favour of it and no note of recommendation from the Treasury can be found on the subject. The minister of finance had two goals: naturally to stop the depreciation of the Franc, which had spiralled downward since the scandal of the false statements at the beginning of 1925, but furthermore to re-establish public confidence a few days before the launch of Caillaux's exchange-guarantee loan.

At the beginning of June, the possibility of an operation in which all the foreign exchange at the disposal of the Bank of France and the totality of the Morgan funds would be used was investigated ‘to not allow domestic or international speculation to operate in an empty market where offers are lacking’.Footnote 22 However, an incident between Caillaux and the Bank of France put paid to this plan. According to Philippe, the Bank of France was alerted by the Lazard Bank of mounting tension vis-à-vis the Franc in New York and refused to act, arguing that they did not have ministerial backing. It is said that in a state of anger, Caillaux confronted Governor Robineau: ‘I testify that from this day forward, I will bestow my services to ensure this defence and I resign myself to do so without your approval.’

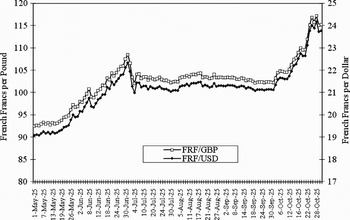

From the last week of June, therefore, the Treasury sold its currency (over 1.3 million sterling and more than 1.3 million dollars) without being able, however, to stop the Franc's depreciation: as shown in Figure 3, sterling reached a maximum of 108.55 Francs on 1 July. There is no doubt that the announcement of the vote to increase note circulation by 6 billion on 27 June had a very negative effect on the exchange rate of the Franc. Nevertheless, the ministry continued. Table 1, which relates purchases and sales of foreign exchange performed by the Treasury, shows that between June and October the Lazard Bank not only bought currency (as it had done since the end of World War I) which allowed the Treasury to cope with repayments of foreign debt, but it also sold sterling and dollars in an attempt to stabilise the exchange rate of the Franc.

Figure 3. FRF/GBP and FRF/USD spot exchange rates (May − October 1925)

Table 1. Foreign-exchange purchases and sales on behalf of the Treasury in 1925 (thousands)

Source: Archives Economiques et Financières, B 32351, Ministère des Finances.

It can be seen that in July 1925, while purchases were almost four times higher than sales, the trend was then reversed: from 3 July, the pound dropped to 103.47 FRF. Had all the possible means of action been used at the beginning of July? Had the authorities given a strong market signal? Did agents in the market expect that the monetary authorities had the firm intention of controlling the external value of the Franc, and that it would therefore pay back, per contra, the Francs supplied in the market, from that moment on? In any case, the rates remained relatively stable until the end of September: sterling moved between 102 FRF and 105 FRF and the dollar between 21 FRF and 21.5 FRF. This was the result of engaging £3.7 million in August and £3.825 million in September, though the amount of dollars used was smaller. The fact that sales of currency were higher than purchases may reveal the existence of market ‘pressure’ leading to the Franc's decline. No more can be said about this, given the available data.

During 1925, even if some purchases were motivated by strategic considerations (that is to take advantage of the opportunity to develop foreign-exchange reserves in order to channel looming tensions), the fact that the Treasury needed foreign exchange in the post-war period was an additional factor in the Franc's depreciation. In 1925 alone, $35 million and almost £35 million were absorbed in this way.

From 1 October, after three months of stability, the Franc suffered a dramatic depreciation. Whereas, on 1 October, sterling and the dollar were worth 102.3 FRF and 21.12 FRF respectively, on 14 October, these currencies had already reached 107.46 FRF and 22.22 FRF and by the 28th they stood at 116.9 FRF and 24.02 FRF. How can such a sudden and substantial drop be explained?

SicsicFootnote 23 suggests that it is linked to the failure of Caillaux's loan which had had an effect from mid September onwards. It may also be observed that the Franc's decline perfectly coincides with the unsuccessful conclusion of Franco-American negotiations over debt. The latter were made public on 2 October, following the rejection of Caillaux's proposals. Without financial approval from the US, the goal of monetary stabilisation was rapidly disappearing. From that moment on, the decline of the French Franc appeared inexorable.

Seven million pounds sterling was sold, but the Treasury was still unable to stop the Franc from spiralling: there was only a very short respite from 7 to 9 October (see Figure 3). During the first two weeks of October, the Treasury used up the totality of the foreign exchange accumulated during the summer. If the difference between total purchases (16,759,999 pounds) and total sales (16,716,768 pounds) carried out between June and October is calculated, it can be seen that the positive balance was only 43,231 pounds. This clearly shows that the Treasury had committed all the reserves of currency which had been collected during this period. As reserves were rapidly depleting, the Treasury considered using the Morgan funds, which had not yet been touched.

Caillaux clearly was ready to use these funds if necessary: in June, he had already given instructions to the Treasury so as to make sure of the liquidity of the available amounts. This premature request confirms that intervention was the minister's personal initiative. In August, whereas Moret deplored the low yield obtained from these funds, Caillaux once again stated his request for liquidity: ‘As the Minister has decided to maintain the liquidity of the Morgan funds in order to be able to act if intervention in the exchange market was necessary, the Treasury has to take this consideration into account while trying to invest the fund as well as possible.’Footnote 24

At the beginning of October, Painlevé (the prime minister at that time) contacted the Bank on this subject ‘given the current trend in the exchange market, I think the time has come to use a first instalment of 10 million dollars’.Footnote 25 The proposal did not meet with approval. Robineau stated his reservations to the General Council of the Bank: ‘in the present circumstances, the Council would undoubtedly not have taken the initiative to suggest such an intervention, which would demand, it thought, much greater contingents, given the seasonal requirements of the market and the exceedingly preoccupying state of the Treasury. It apprehends seeing successive instalments of exchange rate reserves being spent, reserves which had protected the market from foreign speculation for the past eighteen months, and which it seems imperative to conserve. It can, however, only defer to governmental decisions.’Footnote 26 If the operation were to fail, the government alone would be responsible for it. However, on 9 October, Painlevé ordered the Bank of France to transfer 10 million dollars, drawn on the Morgan Funds, to the Lazard Bank in New York. A letter, from Caillaux to Robineau, dated 12 October, confirmed this transfer. In reality, however, this amount was not used. The operation was stopped in circumstances that still remain unclear. The mounting lack of confidence in the Franc may have led the minister to deem its commitment unnecessary: the cabinet was also in the grip of internal political conflict.

IV

The Treasury held sole responsibility for the intervention in May − June 1926. In a memo dated 5 May 1926, Moret warned of the dangers linked to the Franc's sustained depreciation, which had been going on for the past few months. The acceleration of this decline was fuelled by the general rise in prices, the cost of which would become extremely high. Inflation first threatened the fragile equilibrium of the budget, owing to the increase in expenditure it would cause later. Social discontent was also a factor; demands for higher wages were giving rise to a situation of mounting tension. Furthermore, the Franc's total collapse was to be avoided. The experience of the Deutschmark in 1922–3 still haunted memories. The director of the Treasury, in particular, expressed his concern that ‘the exchange rates of these last few days and data obtained from various market sources may lead us to expect a climate of panic which would give rise to even sharper drops if the Government does not intervene and decide on immediate market action’.Footnote 27 Moret was clear about his reservations on the likelihood of success of such an operation to the minister, given the extreme lack of confidence in the Franc. The dollars in the Morgan funds alone would not suffice and according to Moret it would be imperative for the Bank of France to secure part of its gold reserves against loans from the Federal Bank.

Péret immediately approached the Bank of France and warned: ‘the circumstances seem to justify short-term intervention’.Footnote 28 At the same time, the minister of finance demanded that the Bank of France make the dollars from the Morgan funds, which belonged to the Treasury, available. This occurred on 10 May. On the same day, he referred to the possibility of using part of the Central Bank's cash reserves as security if the Morgan funds were insufficient. Péret first spoke of 100 million dollars and then of 150 million dollars (20 May 1926). While, for the minister, this was essentially a defensive measure, it was also meant to restore confidence in assets denominated in French Francs. The commitment of foreign loans secured against the gold reserves of the bank would constitute a strong signal which would squeeze currency speculation to a point where it would no longer be necessary to use the foreign currency and hence the gold reserves. Later, it would open the way to structural measures.

The Bank's reaction was violent and negative. It emphasised the problem of the lack of volume effect against the potential importance of the signalling effect. In a first letter, dated 6 May, addressed to the ministry, the Bank underlined that using the Treasury's dollars would only give short-term respite, and greater action would be unrealistic given the profound lack of public confidence that prevailed in the Franc. There was, therefore, no need to obtain foreign loans, particularly if the Bank of France had to commit its gold reserves to do so: ‘the Board still believes that such a measure is dangerous and should be discarded as a threat of confidence in the currency, the preservation of which has always been a priority’.Footnote 29 The Bank believed that the outcome of the intervention would be negative and as a result it would be unable to pay back the short-term loans to which it had subscribed. It would not be able, therefore, to get back its gold, which would constitute a difficulty when the Franc recovered its gold-convertibility.

For the Bank of France, only the return of public confidence would allow the Franc to appreciate. Nonetheless, the minister of finance thought that, if the Bank could be morally and technically involved in the first operations with the Morgan funds, it would be brought eventually to lend its gold and thus continue the good work. On 19 May, at the Elysée Palace, Robineau, Rothschild and Wendel acknowledged that the commitment of the Morgan dollars, which did not belong to the Bank, could not be opposed. Briand and Péret purposefully recorded: ‘the assent must be given by the Bank of France to use the Morgan funds, insinuating that without that assent they would never assume responsibility for even short-term intervention’.Footnote 30 Péret must have thought that once the Bank became part of the operation, it would follow. The very next day, he wrote to Robineau: ‘using the Morgan funds could only obtain insufficient results and leave us ill-equipped to cope with the inevitable reaction that follows any intervention. It is, therefore, imperative that additional means be obtained, as quickly as possible, for our currency to be saved.’Footnote 31 On 20 May, the Bank had still not given in.

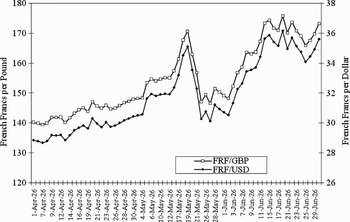

The operation did in fact begin on 21 May in the afternoon. Figure 4 shows that the Franc rose in a spectacular way from 20 May: on 19 May sterling and the dollar were worth 170.8 and 35.11 Francs respectively; the following day they had fallen to 163 and 33.5 Francs. JeanneneyFootnote 32 notes Wendel's view that Lazard Brothers, in association with the Maison Louis-Dreyfus, had taken a position towards the Franc a few days earlier. Desiring to make profit, they would have committed foreign exchange (their own) from 20 May onwards. However, a letter from Lazard Brothers, dated 22 May, seems to suggest the contrary. It reveals that the Lazard Bank was doubtful about the success of the intervention: ‘indeed, we should not, at any time, dissimulate the difficulty of the task and we remain convinced that even if the operation is entered into with all the necessary guarantees, its success can still not be seen as certain’.Footnote 33 So the Bank Lazard regarded the failure of the operation as probable and was already careful to deny all responsibility. Why, therefore, in such circumstances would it have taken its position?

Figure 4. FRF/GBP and FRF/USD spot exchange rates (April − June 1926)

The appreciation of the Franc was certainly more likely to have been the result of expectations by certain ‘well-informed’ agents, wise to massive up-coming intervention in the exchange market. The exceptional meeting, held at the Elysée Palace on 19 May, reminds us of the counter-offensive of March 1924. Moreover, on 20 May, a government communiqué announcing that it intended to use all the resources at its disposal was released. This news would also have influenced expectations.

Whatever the reason, the first results were positive (see Figure 4). On 26 May, sterling and the dollar were worth 149.5 and 30.8 FRF respectively (whereas on 19 May, they had reached 170.8 and 35.1 FRF). To obtain such a result, it had been necessary to commit 35 million dollars on the market. The Morgan funds were therefore exhausted very rapidly and it became necessary to find a new source of money. The Bank of France, however, maintained its opposition, despite repeated requests by Peret and Briand.

On 27 and 28 May, the time came to take a decision. Moret wrote: ‘the balances carried forward on foreign currency are tightening incessantly: they are currently attaining 13 FRF for one pound on three months, which means 35% per annum. It is not surprising that the Franc is being sold short more and more and in such conditions a certain release in the exchange market may be expected.’Footnote 34 Expectations of the French Franc were still pessimistic (foreign currency was still being carried over), brokers were still borrowing Francs short term, hoping to pay them back once the Franc had depreciated. For Moret, strong intervention, provoking additional appreciation of the Franc, would ‘bear squeeze’ speculators and lead to a reversal of the situation as it had in March 1924.

The pound and the dollar were stable at around 150 FRF and slightly over 30 FRF respectively. The Lazard Bank also felt that stopping action at this point would have serious consequences and that it was absolutely necessary to obtain the support of the Bank of France. The Treasury appealed yet again, but to no avail.

After having ‘dumped’ over half the Morgan funds onto the market and, faced with the fact that it could no longer obtain new currency, the Lazard Bank stopped all action on 3 June. However, at the Ministry of Finance all hope had not been lost. During a meeting with Robineau and Briand on 5 June, Péret told the governor that the newly formed board of experts had voted unanimously, minus two votes (one of which was that of the vice-governor of the Bank, P. Ernest-Picard), in favour of the Bank committing its gold reserves. A few days later, on 14 June to be exact, a quarrel broke out between the members of the board: Rist insisted that a formal motion be voted on for the bank to deliver its gold reserves; Ernest-Picard was against and threatened to resign.

Left to itself, the Franc depreciated yet again: on 8 June sterling and the dollar were already worth 163.7 and 33.4 FRF respectively and by 14 June they had attained 173.4 and 35.6 FRF. Peret had not managed to turn the situation around. He resigned from office on 15 June, regretting not having been able to find support from the Bank of France.

V

In a floating exchange rate regime, the intervention of the monetary authorities is used, either to smooth short-term fluctuations on the foreign-exchange market or to bring about a trend reversal in a situation judged as ever more irrational by seeking to correct market perceptions. During the 1920s, interventions were not aimed at reducing the excessive volatility of exchange rates. At the time, this was not a structural factor in the reduction of social well-being. They were used by the French authorities to curb the prolonged decline of the Franc, the so-called ‘leaning against the wind’. Thus, first, the strength of the pressure must be gauged by briefly analysing the features of the dynamics of the exchange market between 1924 and July 1926.

The period is dominated by financial constraints which weighed heavily on the French government.Footnote 35 The policy of fixing interest rates − in order to facilitate the management of public debt − made money supply endogenous to the demand for public bonds.Footnote 36 In a context where fiscal uncertainty was lessened (paradoxically, a capital levy was never introduced under the left-coalition), this demand basically depended on the real yield of bonds, that is to say inflationary expectations. With fixed nominal interest rates, the price level was undetermined: its value was dependent only on the expectations concerning its future movements. Modifications in these involve a variation in the general level of prices and, therefore, expectations were self-fulfilling. On this basis, it seems that intervention in the foreign-exchange market could be successful if and only if it managed to provoke a lasting reversal of price expectations through its signalling effect. Was this really the intention of the French monetary authorities?

On two occasions (March 1924 and May 1926) the monetary authorities agreed on the necessity of intervention to avoid the Franc following the downward path of the Deutschmark, and each time they maintained the hope of a lasting reversal of expectations in the exchange market. We have to note, however, that they more often had circumstantial objectives and were really only waiting for some respite.

In November 1924, the Bank of France wished to reduce the amount of note circulation, at a time when it may have still seemed possible to cover up the scandal of the ‘false statements’ (the Bank no longer cared about this in March 1925, as it intended using the affair to bring down the Herriot government). As far as the Ministry of Finance was concerned, its main intention was to reverse the dynamics of the foreign-exchange market and improve its financial situation on a temporary basis: it wanted either to ensure the success of a loan as at the end of 1924 or during the summer of 1925, or hinder the growth of the nominal value of administrative expenditure as in May 1926.

On account of the limited motivations and the pursuit of certain individual personal interests, the French monetary authorities did not consider the credibility of their defensive actions, that is to say the context in which would be operating. Indeed, the compatibility of their interventions with the current monetary and financial environment or, more precisely, with the way in which the market perceived the French situation, was not taken into account.

The credibility of an intervention, i.e. its capacity to overturn expectations, is greatly linked to the definition of the budgetary stabilisation plan. The three interventions of November 1924, June 1925 and May 1926 were effective in the very short term, as the authorities managed to turn the trend of the market around for a few days or even for a few weeks. It can be noted, however, that both the effect of surprise and the secrecy which surrounded these actions were reduced. The political nature of the decision and the intermediation of commercial banks favoured the announcement to a few ‘initiated’ individuals a few days before. On several occasions, an official communiqué forewarned the public of pending intervention. On the basis of the existence of asymmetric information between the authorities and the market, the traders presumably anticipated a change of tactics in French economic policy. If, in principle, the concept of credibility articulates the means, the effects and the context, we do have to underline that this capacity provisionally to reverse the depreciation of the Franc was not determined by the means employed: in May–June almost all the Morgan funds were used without success, whereas in March 1924 less than half had been enough to obtain a reversal of expectations; and during the summer of 1925 it had taken very little in the way of resources to obtain respite. More recent theoretical work on the subject reaches the same conclusion.Footnote 37

In the long term, these interventions were ineffective, as nothing changed the market perception, even though it was incorrect, of the fundamentals of the French economy. The authorities did not send any other signals destined to reassure traders: no increase in fiscal pressure, no reduction of public expenditure, and, above all, no will to develop any inclusive and coherent plan to stabilise the Franc. Besides, and more precisely, this sequence of signals had ensured the success of the operation in March 1924. The detailed chronology of this episode shows that it was the announcement of the setting-up of a programme to re-equilibrate public finances rather than that of intervention that permitted the reversal of expectations. Indeed, the episode of stabilisation also puts things into perspective, underlining the importance of interventions for the reversal of expectations. The policy of stabilisation proposed by the board of experts at the beginning of July 1926 (which garnered broad consensus amongst economists and politicians) considered that obtaining foreign loans so as to guarantee the stability of exchange rates by direct intervention in the foreign-exchange market was essential (the figure of 100 million dollars was announced, but at the beginning of August Moret thought that twice the amount would be necessary). As a matter of fact, the change in regime during the summer of 1926, was so transparent and credibleFootnote 38 and the inflow of capital was so great that the Poincaré government did not need to use this currency and that the intervention which began in December 1926 and continued until June 1928 had the objective of avoiding too greater an appreciation of the Franc.Footnote 39

Taking the French experience as an example, it seems that interventions do not play a major role in the process of reversal of expectations. They can only be effective when accompanied by monetary and budgetary measures. It can also be seen that the French authorities’ way of learning to deal with the management of exchange rates was hesitant: motivation was unclear and neither the timing nor the credibility of actions was envisaged. The novelty of the economic phenomena at stake and the specificity of the historic circumstances can partially explain these prevarications.

At the same period, the Belgian monetary experience leads to similar conclusions as regards the effectiveness of exchange rate interventions. The monetary trajectory of that country and France are comparable: significant inflation prevailed since the end of World War I and the successive governments faced important financial difficulties. The Belgian Franc depreciated but the Belgian authorities were not able to accept the idea of a stabilisation devaluation.

ChlepnerFootnote 40 and Van der Vee and TavernierFootnote 41 highlight the three main actions of the National Bank of Belgium in the foreign-exchange market in 1925 and 1926 during the pre-stabilisation process of the Belgian Franc.

During this period, the Belgian monetary authorities had observed with much interest the success of the French intervention in March 1924: in May 1925 the National Bank of Belgium supported the Belgian Franc in order to facilitate the placing of a great funding loan of debt. More precisely, its intervention on the foreign-exchange market tried to smooth the course of the Belgian Franc via a diminution of its exchange reserves. Hence, the Belgian Franc was stabilised around 109 BEF for one GBP in a few days. According to Van Der Vee and Tavernier ‘at the beginning of June, the speculative pressure was so intense that the Bank was resolved to cease its interventions.’Footnote 42 This intervention took place during an important governmental crisis when public finances seemed to be out of control; and the funds raised were unable to counterbalance refunding of debt. Moreover, at that time, the national consensus was not in favour of the stabilisation of the Belgian Franc (a persistent debate between the partisans of deflation and those who favoured stabilisation-devaluation). In this context, this intervention could not durably turn over the anticipations of depreciation on the foreign-exchange market. According to Chlepner,Footnote 43 another intervention took place between October 1925 and 15 March 1926: the National Bank managed to maintain the Belgian Franc around the 107 BEF for one GBP. Here again, the lack of credibility of the stabilisation plan put in place by Janssen and the failure of a foreign loan negotiated with private bankers forced the Bank to withdraw. At the end of March, one pound was equal to 130 BEF, but by the end of April it had risen to 140 BEF.

In October 1926, the plan of stabilisation was now credible and a consensus emerged in favour of stabilisation, the Belgian Franc (as did the French Franc) appreciated on the foreign-exchange market: expectations were overturned. The National Bank successfully intervened in October to stop this appreciation and the Belgian Franc was stabilised on 25 October 1926 at 175 BEF for one GBP.

VI

When put into perspective, it can be seen from the four defensive actions we have studied, that co-operation − even when it was imposed − between poles of the monetary authority (minister and director of the Treasury on one side, the Bank of France on the other) constituted the prerequisite for the success of an intervention, even if it did not guarantee it. The perennial state of discord between the monetary powers under the left-coalition represented a factor of uncertainty which was harmful for the credibility of the action. The repeated failure to halt the fall of the Franc certainly aggravated the exchange rate crisis in the spring of 1926. In fact, the disagreement on the possibility of intervention concealed far greater divergence on the choice of monetary regime for France. When Keynes, as a conclusion to his open letter to the French minister of finance in January 1926, asked the question: ‘is there any sufficient objection to using the gold in the Bank of Franc to anchor the Franc exchange?’,Footnote 44 he knew that, since the publication of Tract on Monetary Reform, he was practically alone in defending the superiority of the forced exchange rate regime over the gold standard, and that in France the question of the Issuing Institution commitment of its gold reserves was truly at the centre of monetary debate.

If consensus among the monetary authorities prevailed after the war, on the introduction of a deflationary policy allowing the return of former parity between the Franc and gold, from mid 1922, in the face of Germany's proven financial weakness and the ever-increasing difficulty to support the national debt, the Treasury denounced the chimerical nature of such an action. The Treasury called for a more realistic monetary policy involving a stabilisation-devaluation of the national currency. Until 1926, the Treasury was in open conflict with the Bank of France (which remained in favour of the revaluation of the Franc). The Bank's gold, essential for forceful intervention in the exchange market, did not have the same importance for the two institutions. For the Bank of France, committing its reserves would jeopardise the future revaluation of the Franc; it was unable to dissociate the gold standard principle of stability from the issue of the level of ‘metallic’ definition of the Franc. For the Treasury, which had accepted the idea of lowering the gold value of the Franc, the loss of gold was not really a problem. The French monetary authorities’ failure to squeeze expectations cannot be dissociated from their divergences on the future definition of the ‘metallic’ value of the Franc. As from the end of the month of June 1926, those who supported the idea of stabilisation-devaluation of the Franc were at the head of the Bank, French monetary intentions became clearer and stabilisation more credible. The market was then ready to shift its opinion.

VII

To conclude, we must obviously emphasise that the existence of these actions in the foreign-exchange market leads us to reconsider the hypothesis of exogeneity of the monetary base in France in the mid 1920s and leads us to reject the conventional view of the existence of a perfectly pure floating regime at this period. These interventions should not be overlooked and the French Franc is not as it is traditionally presented, the archetype of a floating currency. By the same token, this French episode surely calls for a more detailed examination of the behaviour of other European central banks during the period.

Finally, these interventions can be reintroduced into the Nurkse/Friedman debate on the stabilising or destabilising nature of speculation. As they did, in fact, reveal the discord between monetary authorities and their inability to control the economic situation. They had the counter-productive effect of bringing into the open the absence of anchorage for expectations: in such conditions, it is not only the traders’ actions that were destabilising.

Appendix

Note circulation dynamics (true and announced) between March 1924 and April 1925