RACIAL ATTITUDES AND BLACK UNDERREPRESENTATION

It is a longstanding truth that the number of black members in Congress is not proportionate to the national population. Even recent Congresses, which are racially diverse by historical standards, continue to have fewer blacks than we should expect from national demographics. Data from the Congressional Research Service and from the US Census Bureau show that in 2015 only 8.9% of the members of the 114th Congress were black compared with 12.2% of the national population (Irving Reference Irving2015; Manning Reference Manning2014). This gulf in representation is near its narrowest in US history (Bump Reference Bump2015), but the gap has been narrowing at an extremely slow rate with eventual representational parity being an uncertainty.

Despite longstanding awareness in political science of black underrepresentation in national elected office, various studies have been inconclusive on the causes of this disparity (Hutchings and Valentino Reference Hutchings and Valentino2004). Scholarly and popular explanations have included voter suppression (Bentele and O'Brien Reference Bentele and O'Brien2013; Hajnal, Lajevardi and Nielson Reference Hajnal, Lajevardi and Nielson2017), partisan gerrymandering (Barabas and Jerit Reference Barabas and Jerit2004), racial gerrymandering (Canon Reference Canon1999), the geographic distribution of black voters (Grofman and Handley Reference Grofman and Handley1989), first-past-the-post elections (Rule and Zimmerman Reference Rule and Zimmerman1994), and variation in black voter empowerment/mobilization (Gilliam Jr. and Kaufman Reference Gilliam and Kaufman1998; Rocha et al. Reference Rocha, Tolbert, Bowen and Clark2010; Washington Reference Washington2006; Whitby Reference Whitby2007). Perhaps the most obvious explanation, that racial resentment attitudes held by whites toward blacks are to blame, is still in question. Some researchers find little effect of racial attitudes on vote choice (Highton Reference Highton2004; Sigelman et al. Reference Sigelman, Sigelman, Walkosz and Nitz1995). Other researchers have found that negative racial attitudes toward blacks do hurt black candidates in elections (Moskowitz and Stroh Reference Moskowitz and Stroh1994; Piston Reference Piston2010; Terkildsen Reference Terkildsen1993). Furthermore, an increasingly large body of work argues that negative racial attitudes toward blacks among white voters not only harm black candidates but all Democrats running for office, by dint of their association with civil rights and other policy positions supported by blacks (Aistrup Reference Aistrup1996; Brewer and Stonecash Reference Brewer and Stonecash2001; Edsall and Edsall Reference Edsall and Edsall1992; Luttig and Motta Reference Luttig and Motta2017; Tesler Reference Tesler2013). In short, whether racial resentment is the mechanism by which blacks are systematically underrepresented in national elected office is still a matter of debate.

To address this gap in the literature, I endeavor in this paper to answer a pair of important questions about the role of racial attitudes in contemporary congressional elections. First, do negative racial attitudes toward blacks affect vote choice, regardless of the race of the Democratic candidate? Second, are these effects more pronounced for black Democratic congressional candidates than for white Democratic candidates?

My research seeks to help us understand why black underrepresentation in Congress has persisted despite massive social and political change in recent decades. This debate is particularly salient given recent evidence that racial resentment was a key driver of President Trump's electoral support in 2016 (Hooghe and Dassonneville Reference Hooghe and Dassonneville2018; Schaffner, Macwilliams and Nteta Reference Schaffner, Macwilliams and Nteta2018; Tolbert, Redlawsk and Gracey Reference Tolbert, Redlawsk and Gracey2018). This analysis examines the effect of racial attitudes on white voting behavior by utilizing the large-N Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES) dataset to systematically examine voter behavior at the congressional district level. In particular, I seek to resolve the question of what role white racial resentment toward blacks plays in contemporary American voting behavior.

Additionally, this paper enhances our understanding of racial inequality in the United States in several significant ways. First, this research sheds light on persistent representational inequalities on the national stage, specifically the underrepresentation of blacks in Congress. I find that racial resentment is negatively affecting whites’ likelihood of voting for black candidates, providing a potential mechanism that helps explain the ongoing underrepresentation of blacks in Congress. This suggests that the normatively undesirable conundrum of black underrepresentation may not be resolved by merely recruiting additional black candidates to run for office. Furthermore, I find that Democratic candidates of all races are penalized electorally as a result of discriminatory attitudes by white voters, which provides additional support for the “racial realignment” argument advocated by many studies of the modern American party system.

RACE, RACIAL ATTITUDES, AND VOTING

The effect of race and racial attitudes on voter behavior has a long history in the United States. Indeed, it was not until Reconstruction that the first black candidate was elected to the House of Representatives. It would not be until 1928 that the first black candidate would win election outside the South, where blacks lived in the highest concentrations. Though the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 lowered many of the formal institutional barriers preventing blacks from exercising their voting rights, black candidates continued to win a staggeringly low number of congressional seats. In the 30-year period from 1966 to 1996, black candidates won a mere 35 House elections in majority white districts (Canon Reference Canon1999). The paucity of black electoral success in majority white districts suggests two possible (and non-exclusive) explanations: (1) there are mechanisms at work in these majority white districts that stymie black candidate emergence and (2) white voters are less willing to vote for black candidates.

With regard to the first theory, there is some research that suggests that black candidate emergence is dampened in districts with low black populations. As Highton (Reference Highton2004) and Silver (Reference Silver2009) note, blacks rarely emerge as candidates in majority white districts. While white voter reluctance to vote for black candidates is one possibility, discouragement of potential black candidates by party elites (party leaders, donors, etc.) may be to blame. A similar suggestion is made by Sonenshein (Reference Sonenshein1990), who finds three prominent examples of black candidates for statewide office who were discouraged to run by party leaders. This possible aversion party leaders have to black candidates may result in lower recruitment of black candidates, which may in turn result in the emergence of fewer black candidates outside the context of minority–majority districts. In such minority–majority districts, party leaders can “afford” to nominate black candidates, knowing that they are likely to prevail. In whiter constituencies however, party leaders’, interest groups’, and donors’ aversion to black candidates (due to in-group bias or due to strategic calculations about the electorate's willingness to support a black candidate) may retard the emergence of black candidates. Furthermore, the wealth gap between blacks and whites makes it difficult for black “outsider” candidates (who are not backed by party elites) to self-fund in the way many white candidates who lack party backing are able to (Highton Reference Highton2004).

Though the question of black candidate emergence is of interest when considering why black candidates are underrepresented in Congress, the central question of this paper concerns whether white voters are less likely to vote for black candidates under certain conditions. Specifically, I seek to address how white voters’ attitudes of racial resentment affect both their willingness to vote for black candidates. While significant research has been conducted on how candidate race affects the attitudes of white voters, less research has been conducted on the specific effect of racial resentment. That being said, evidence for how candidate race (not racial attitudes) affects white voter attitudes is decidedly mixed. Moskowitz and Stroh (Reference Moskowitz and Stroh1994) suggest that black candidates receive poorer evaluations from white voters. In addition, Petrow, Transue and Vercellotti (Reference Petrow, Transue and Vercellotti2017) find that white in-group identity makes white voters less likely to support black candidates. Furthermore, when black politicians run for office, their campaigns tend to feature more racial campaign messages, which further prime voters to incorporate their racial attitudes into their vote choice (McIlwain and Caliendo Reference McIlwain and Caliendo2011). In a recent study that also makes use of CCES data, Ansolabehere and Fraga (Reference Ansolabehere and Fraga2016) find that white voters (of both parties) show a preference for white incumbents to incumbents of other races, which may help white candidates emerge and win in swing House districts.

Some authors find however that race has a minimal impact on white voting behavior. Sigelman et al. (Reference Sigelman, Sigelman, Walkosz and Nitz1995) argue that a candidate's race is a minor factor in whites’ political perceptions. Highton (Reference Highton2004) similarly finds that in the 1996 and 1998 congressional elections, “white voters were not less likely to vote Democratic when the Democratic candidate was black.” These latter two findings are not directly at odds with my predictions but do suggest that race may be less salient electorally than we might predict.

Importantly, these previous findings that a candidate's race does not radically affect whites’ voting behavior or political perceptions do not account for racial attitudes, as my research attempts to do. The model of white voting behavior used by Highton (Reference Highton2004), for example, accounts for the race and party of the candidate as well as the ideology and party of the voter, but does not control for the voter's racial attitudes. Sigelman et al. (Reference Sigelman, Sigelman, Walkosz and Nitz1995) take a similar approach in their experiment-driven research, accounting for the ideology and race of the candidate and the ideology of the white participants but not explicitly pre-screening for racial attitudes. While both these authors and others may be entirely correct that a candidate's race in and of itself may not affect the likelihood of her receiving support from white voters, the authors’ studies do not explicitly test whether this non-effect holds specifically among the large number of white voters with racially prejudiced attitudes.

Previous research that focuses on questions of racial resentment and racial prejudice (and not solely the race of the candidate) suggests that differing levels of racial resentment among white voters affects their willingness to vote for black candidates. An experiment conducted by Terkildsen (Reference Terkildsen1993) finds that white voters somewhat prefer to vote for white candidates and, importantly, that this effect is stronger when those voters scored high on measures of racial prejudice. More recently, several studies have found that President Obama received fewer votes due to racial resentment in his 2008 and 2012 election campaigns (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Kornberg, Scotto, Reifler, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2011; Knuckey and Kim Reference Knuckey and Kim2015; Lewis-Beck, Tien and Nadeau Reference Lewis-Beck, Tien and Nadeau2010; Piston Reference Piston2010) and that opposition to his candidacy was more racialized than for ideologically similar white candidates (Tesler Reference Tesler2013). Finally, several authors have suggested that white voters’ negative racial attitudes toward blacks not only harm black candidates but all Democrats running for office, by dint of their association with civil rights and other policy positions supported by blacks (Aistrup Reference Aistrup1996; Brewer and Stonecash Reference Brewer and Stonecash2001; Edsall and Edsall Reference Edsall and Edsall1992). For instance, recent analyses have shown that racial resentment toward Obama “spilled over” into the 2010 (Petrow, Transue and Vercellotti Reference Petrow, Transue and Vercellotti2017; Tesler Reference Tesler2013) and 2014 (Luttig and Motta Reference Luttig and Motta2017) midterm elections, with Democratic congressional candidates receiving fewer votes from high resentment white voters by dint of their association with President Obama. Even in the absence of a racially polarizing black political figure, racialized campaign messaging has been found to be effective for altering the candidate and policy preferences of white voters (Algara and Hale Reference Algara and Hale2019; Hurwitz and Peffley Reference Hurwitz and Peffley2005; Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg1997; Reference Mendelberg2008; Valentino, Hutchings and White Reference Valentino, Hutchings and White2015).

In sum, the various strains of the literature discussed here offer varying explanations for black underrepresentation in Congress, there is no clear narrative that emerges regarding the combined effect of candidate race and racial attitudes on vote choice in modern congressional elections. As Hutchings and Valentino (Reference Hutchings and Valentino2004) point out, “in the area of race, partisanship, and voting behavior, for example, we still are unsure why whites do not support black political candidates” (p. 398). Still, research on the effect of racial prejudice on political attitudes outside the voting booth is fairly conclusive, making the lack of consensus on the effect of racial attitudes on voting behavior all the more puzzling. Several studies have found that racial attitudes among whites are extremely strong predictors of major public policy attitudes (e.g., welfare, Social Security, equal opportunity hiring), even when controlling for party ID, ideology, and other potential confounding variables (Gilens Reference Gilens1996; Sears et al. Reference Sears, Lau, Tyler and Allen1980; Reference Sears, Van Laar, Carillo and Kosterman1997; Winter Reference Winter2008). There is no theoretical rationale to believe that this well-documented effect of whites’ racial attitudes on their policy preferences should be sequestered from their electoral behavior. We should expect that just as racial prejudice affects policy attitudes, so too does it constrain voting behavior.

A COMPOUND EFFECT OF RACIAL RESENTMENT

Previous research on the effect of racial resentment on vote choice has tended to separately ask whether racial resentment hurts black candidates or Democratic candidates. However, there is ample evidence in the literature that suggests that racial resentment operates at multiple levels of electoral competition and that spillover effects across these levels are commonplace—particularly in the Obama era. Tesler (Reference Tesler2013) not only finds that racial resentment much more strongly predicted opposition to Obama than white candidates with similar left-right ideological positions, but also that racial attitudes better predicted vote choice in the 2010 midterms than in the 2006 midterms. Tesler (Reference Tesler2012) also finds that racial resentment better predicted support for Obamacare than for Bill Clinton's health reform proposal in 1993. In combination, these results suggest a spillover effect of racial resentment from the presidential level (see also Petrow, Transue and Vercellotti (Reference Petrow, Transue and Vercellotti2017) and Luttig and Motta (Reference Luttig and Motta2017)). In short, the effects of candidate race and racial resentment on vote choice are not easily distinguished from one another—even in contests where there is no black candidate.

While there is mixed evidence that candidate race affects vote choice, previous studies finding little effect of candidate race on vote choice have not accounted for whether this effect is mediated by voters’ racial attitudes. In this light, these null results are unsurprising, as voters with low resentment could be counteracting an effect among high resentment voters. Rather than look at the effects of candidate race and racial resentment on vote choice independently, I instead propose that they are interactive. I predict that Democratic candidates are punished electorally by voters with high-racial resentment, and that black Democratic candidates face a compound penalty among these voters as a result of their race.

H1: White voters with strong racial resentment toward blacks will be less likely to vote for Democratic House candidates than for non-Democratic candidates of any race.

H2: White voters with strong racial resentment toward blacks will be less likely to vote for black Democratic House candidates than white ones.

DATA

This study relies on CCES national election survey data from 2010 to 2016. The CCES studies how Americans view Congress and hold their representatives accountable in elections. The CCES data used in this paper make possible statistically significant analysis at the congressional district level. Though the study began in 2006, I examine the period from 2010 to 2016, as questions regarding racial resentment were introduced in 2010.

Rather than look at the effects of racial resentment on all black candidates I choose to focus my research on black Democratic candidates (and Democratic candidates more broadly). There are two main reasons for excluding black Republican candidates from my analysis. First, there are very few black Republican candidates who actually receive their party's House nomination and run in the general election. Considering that there are only four black Republicans who have served in the House since 2010, the paucity of black House candidates should come as little surprise. In addition, the black Republican candidates that do emerge in House races in this period do not seem to follow a clear pattern. There is little that the districts of Tim Scott (R-SC), Allen West (R-FL), Will Hurd (R-TX), and Mia Love (R-UT) have in common. Hurd is a relatively moderate representative hailing from a racially diverse TX swing district, whereas Love comes from an extremely white and very Republican UT House district.Footnote 1 Given the scarcity and anomalous nature of black Republican House candidates, it has proven infeasible to use them as a subject of analysis.

From this data, I have specified a number of variables that I believe are important for evaluating the relationship between racial resentment and voting behavior. Though I will explain my key variables in depth below, refer to the Supplementary material for coding explanations and question wording for each variable. My dependent variable, House vote choice, is a simple dichotomous measure. A respondent voting for a Republican House candidate is coded as a “0,” whereas voting for a Democratic House candidate is coded as a “1.” This voting measure is generated using a standard voting intention question which asks, “In the general election for US House of Representatives in your area, who do you prefer?” The small number of voters who prefer a third party and the larger number who are undecided are not included in this analysis.

My primary independent variable of interest is an index of racial resentment from the two relevant questions in the CCES. The first asks voters to agree or disagree with the following statement on a 5-point Likert scale: “The Irish, Italians, Jews, and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors.” Agreement with this statement is considered racial resentment. The second statement is as follows: “Slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for blacks to work their way out of the lower class.” Disagreement with this statement is coded as racial resentment. To standardize the scales, I flipped the first measure so a “1” would constitute a lack of racial resentment and a “5” would signify strong resentment prior to merging the two scales.Footnote 2 This measure of racial resentment is based on groundbreaking work by Kinder and Sears (Reference Kinder and Sears1981), Kinder and Sanders (Reference Kinder and Sanders1996), and Henry and Sears (Reference Henry and Sears2002).Footnote 3 The questions offered in the CCES do not include all those included in the Henry and Sears (Reference Henry and Sears2002) scale and are focused on indirectly measuring a new, post-civil rights era, racism “that is more subtle than its predecessor but equally invidious, deriving its strength from a combination of anti-black sentiment and traditional American values, one of which, above all, is individualism” (Carmines, Sniderman and Easter Reference Carmines, Sniderman and Easter2011).Footnote 4 Though the 2016 CCES uses different questions to measure racial attitudes,Footnote 5 voters agree/disagree responses in 2016 to the statement “White people in the United States have certain advantages because of the color of their skin” correlate with party identification, approval of President Obama, and party identification nearly identically to the two-item scale I construct for 2010–2014. This suggests strongly that the two-item scale from 2010 to 2014 and the one-item scale used in 2016 are capturing the same underlying racial attitudes.Footnote 6

The second theoretically crucial independent variable used in my model is the candidate's race. In the CCES, respondents are asked to report the race of each major party candidate running in their district. If a voter believes the Democratic candidate is white, the Democratic candidate race variable is coded as a “0.” If a voter believes the Democratic candidate is black, this variable is coded as a “1.” If a voter does not have a belief about the candidate's race or believes them to be of another race, that voter is excluded from the analysis. A parallel coding approach is applied to the Republican House candidate. Since I believe negative racial attitudes toward blacks should be affected by voters’ beliefs about a candidate's race, I believe that using perceptions of candidate race is appropriate in this instance.Footnote 7 It is worth noting that 44% of my respondents did not answer this question for either the Democratic or Republican candidate.Footnote 8Table 1 shows the percentage of the 56% of respondents in my sample who correctly and incorrectly identified the race of the Democratic candidate running in their district.

Table 1. Correct identification rate of Democratic candidate race

Table 1 demonstrates that among the 56% of voters who reported that they knew the race of the Democratic candidate, they overwhelmingly reported the candidate's race correctly. If the Democratic candidate was black, white voters correctly identified the candidate as such over 85% of the time. When the Democratic candidate was white, white voters correctly perceived their race 96% of the time. Voters who declined to identify or incorrectly identified the race of the Democratic candidate in their district are excluded from this analysis, as we should not expect them to punish black candidates if they do not know their race.Footnote 9

In addition to my two central independent variables, I also include a number of controls in my vote choice model. In deciding which variables to include, I have followed the example set by previous congressional vote choice models, such as that used by Eckles et al. (Reference Eckles, Kam, Maestas and Schaffner2014). Higher values of my “presidential approval” variable indicate higher approval of President Obama, which I expect will be predictive of increased willingness to vote for a Democratic House candidate. I use a simple dichotomous measure of incumbency, as incumbents should fare better than non-incumbents electorally. There are also a series (2012, 2014, and 2016) of election year dummy variables, with 2010 as the baseline, to account for national trends. Most importantly, I include control variables to account for partisanship (by far the most important predictor of congressional vote choice in recent elections). These partisanship variables are dichotomous dummy variables for each category of the standard 7-point Likert scale of partisanship (strong Democrat, lean Democrat, weak Democrat, independent, weak Republican, lean Republican, strong Republican), with the neutral category omitted and used as the baseline.

To improve the robustness of my model, I have also incorporated data from sources outside the CCES. To account for the competitiveness of a given district and supplement my incumbency data, I have drawn upon Gary Jacobson's congressional elections dataset, which contains such district-level information. Furthermore, I have also added data from the 2010 decennial census and the 2015 American Communities Survey to my analysis as well. These datasets contain congressional district-level measures of racial demographics, which are a vital indicator of whether a black Democratic candidate could viably contest the seat.

Rather than use data from across all 2010–2016 congressional elections, I make a theoretically important sample restriction based on a simple truth: black candidates do not emerge and run randomly in House races across the country. There is no theoretical reason to believe that the types of House districts where black Democratic candidates do emerge and run are substantively similar to those where black Democratic candidates do not. As Highton (Reference Highton2004) and Silver (Reference Silver2009) find, the vast majority of black officeholders are elected from constituencies with a large proportion of blacks. This finding is confirmed by the 2010–2016 CCES data in conjunction with census figures. Among races where white voters reported the Democratic candidate was black, the average congressional district was 31% black, compared with the average district in the sample, which is only 10% black.

To accurately reflect reality that black candidates tend to run and win only in districts with a certain threshold of black voting population, I restrict my sample based on the demographics of actual congressional districts. I set the lower bound of black district population in this model to be 12%, which is just shy of the 12.8% black population in Keith Ellison's (D-MN) congressional district in 2009. For the upper bound of black district population, I use 64%, which is just over the 63.5% black population of Steve Cohen's (D-TN) congressional district. Ellison's district is the least black district represented by a black House member and Cohen's district the most black district represented by a white House member in recent Congresses. As such, I use them as extreme bounds, excluding districts with higher or lower proportions of black citizens.Footnote 10 This approach seeks to address selection bias by limiting my sample to districts that could feasibly have a black or a white Democratic nominee. With this restriction in place, the subsample of 2010–2016 CCES data I use contains 42,452 white voters.

To gain further insight into the data, we can examine the summary statistics for the key variables in my model.Footnote 11 Recall that the universe of respondents examined in this study is restricted to white voters (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary statistics of key dependent, independent, and control variables among white voters in “Black Emergent” districts

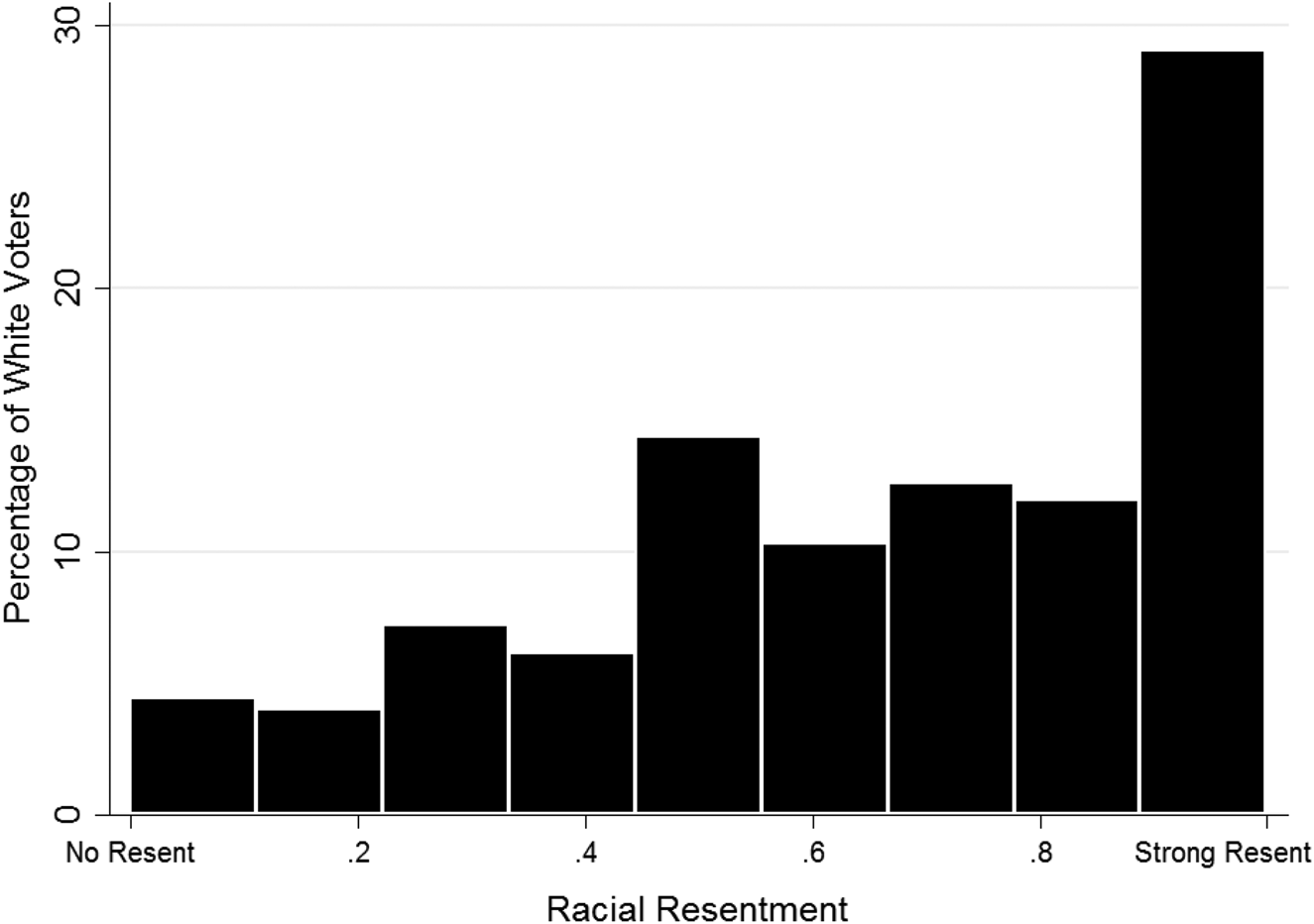

As the summary statistics in Table 2 show, the Democratic candidates in my sample are largely white, the voters tend to prefer Republican House candidates, and racial resentment is fairly high. This last point can be corroborated by examining a histogram showing the distribution of racial resentment attitudes among white voters.

As Figure 1 indicates, the distribution of racial attitudes toward blacks among white voters is left-skewed, with most tending to be on the higher range of the index. In particular, nearly 30% of white voters fall into the “1” category, indicating strong levels of racial resentment. This means that these voters selected the responses in the implicit racial resentment questions in the CCES (that compose my racial resentment index) that correspond with the most negative attitudes toward blacks.

Figure 1. Distribution of racial attitudes toward blacks among white voters.

RESEARCH DESIGN

To motivate this research let us consider a set of “naive” simple cross tabulations between racial resentment and vote choice. Figure 2a shows the two-party vote choice among white voters by their level of racial resentment toward blacks. Figure 2b shows the vote choice between a black candidate and a white one (regardless of party), with the sample restricted to voters in districts where a black House candidate was actually on the ballot.

Figure 2. Vote by racial resentment. (a) Racial resentment by vote choice and (b) racial resentment by race of preferred candidate.

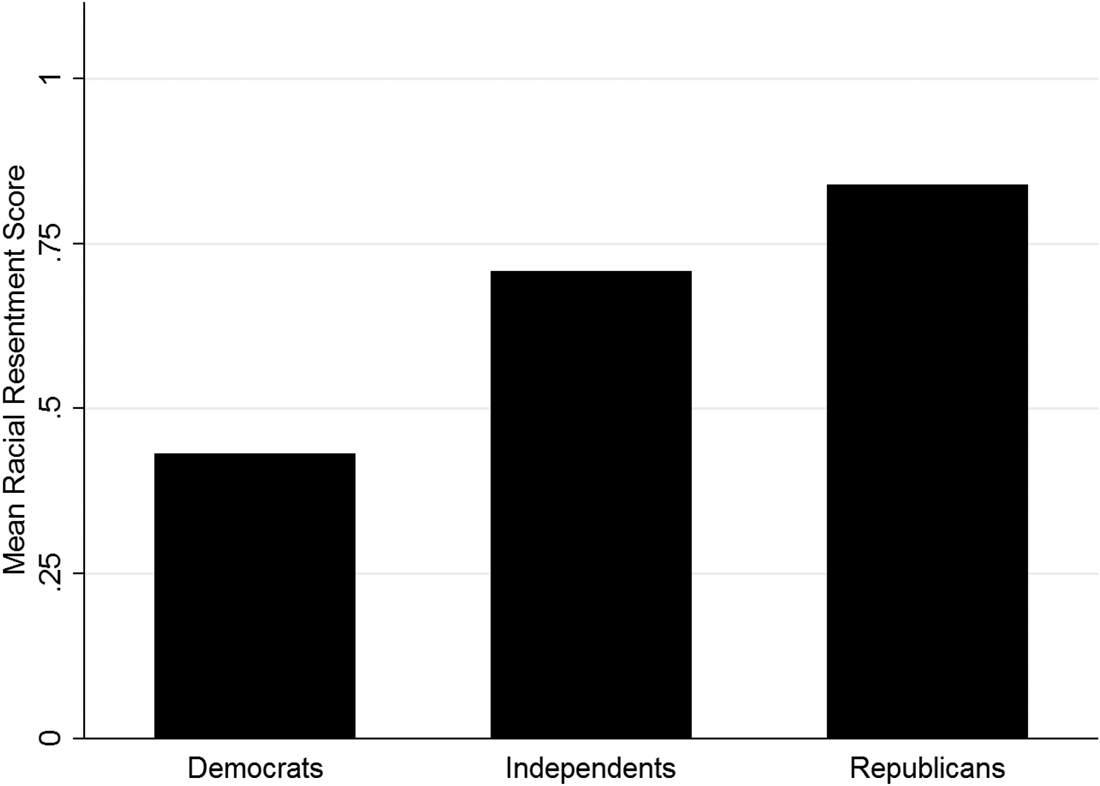

At first blush, these figures seem to indicate that racial resentment attitudes toward blacks have a massive impact on whites’ vote choice in House elections. As shown in Figure 2a, the mean racial resentment of voters who prefer the Republican candidate is much higher than that of voters who prefer the Democratic candidate. The relationship is similar in Figure 2b, which only contains elections featuring a black Democratic candidate. The apparent strength of this effect is not to be trusted, however. Considering the overwhelming evidence that partisanship is the all-encompassing explanation for voter behavior in contemporary congressional elections (Abramowitz and Webster Reference Abramowitz and Webster2015; Bafumi and Shapiro Reference Bafumi and Shapiro2009; Jacobson Reference Jacobson2015), the obvious explanation for this relationship is that partisanship and racial resentment are strongly correlated, and that the strong relationship shown in these figures is merely a proxy for partisanship. Figure 3 provides ample evidence for a strong correlation between partisanship and racial resentment, which makes an independent relationship between racial resentment and vote choice hard to determine merely from a cursory examination.

Figure 3. Distribution of racial resentment by party.

Figure 3 shows that there is a clear correlation between racial resentment and partisanship among white voters, with GOP voters having the highest resentment on average, and Democratic voters the least. Given the correlation between vote choice and racial resentment and the correlation between racial resentment and partisanship (as well as the well-documented relationship between partisanship and vote choice), the obvious next step is to construct a statistical model that will allow us to disaggregate the effects of partisanship and racial resentment toward blacks on whites’ vote choices.

Let us consider a model of vote choice that incorporates racial resentment, the race of the candidate, and partisanship. Because of the dichotomous dependent variable, I have elected to use a logit model to capture the probability of voting for a Democratic House candidate.

$$ \eqalign{& {\rm Vote}\;{\rm for}\;{\rm a}\;{\rm Democratic}\;{\rm Candidate}\; \cr = \;{\rm \alpha }\, &+ \,{\rm \beta }_1\left( {{\rm Race}\;{\rm of}\;{\rm Democratic}\;{\rm Candidate}} \right)\, + \,{\rm \beta }_2\left( {{\rm Racial}\;{\rm Resentment}} \right)\, \cr &+ {\rm \beta }_3({\rm Democratic}\;{\rm Candidate}\;{\rm Race}\; \times \;{\rm Resentment}) \cr & + \,{\rm \beta }_4\left( {{\rm Voter}\;{\rm Party}\;{\rm ID}} \right)\; + \;{\rm \beta }_5\left( {{\rm Presidential}\;{\rm Approval}} \right)\, \cr &+ {\rm \beta }_6\left( {{\rm Incumbency}\;{\rm Status}\;{\rm of}\;{\rm Democratic}\;{\rm Candidate}} \right)\; \cr &+ {\rm \beta }_7\left( {{\rm Year}} \right)\,\; + \;\varepsilon } $$

$$ \eqalign{& {\rm Vote}\;{\rm for}\;{\rm a}\;{\rm Democratic}\;{\rm Candidate}\; \cr = \;{\rm \alpha }\, &+ \,{\rm \beta }_1\left( {{\rm Race}\;{\rm of}\;{\rm Democratic}\;{\rm Candidate}} \right)\, + \,{\rm \beta }_2\left( {{\rm Racial}\;{\rm Resentment}} \right)\, \cr &+ {\rm \beta }_3({\rm Democratic}\;{\rm Candidate}\;{\rm Race}\; \times \;{\rm Resentment}) \cr & + \,{\rm \beta }_4\left( {{\rm Voter}\;{\rm Party}\;{\rm ID}} \right)\; + \;{\rm \beta }_5\left( {{\rm Presidential}\;{\rm Approval}} \right)\, \cr &+ {\rm \beta }_6\left( {{\rm Incumbency}\;{\rm Status}\;{\rm of}\;{\rm Democratic}\;{\rm Candidate}} \right)\; \cr &+ {\rm \beta }_7\left( {{\rm Year}} \right)\,\; + \;\varepsilon } $$In this model (as described in the “Data” section) I use a racial resentment index that combines two CCES questions as my first primary independent variable. I also incorporate a dummy variable for the party of the black candidate. Importantly, I also include an interaction term for these two variables, as I expect that they have co-varying effects on vote choice—racial resentment should have a greater bearing on vote choice when the Democratic candidate is black. In the vein of Eckles et al. (Reference Eckles, Kam, Maestas and Schaffner2014), I also incorporate a measure of party identification. In lieu of the economic evaluations measure used by Eckles et al. (Reference Eckles, Kam, Maestas and Schaffner2014), I use presidential approval, which is a highly correlated measure. Finally, I include yearly fixed effects to control for the differences in the political climates in 2010–2016.

RESULTS

Table 3 displays the tabular output from a pair of differently specified logit models of House voting among white voters in the 2010–2016 US general elections.Footnote 12 The coefficients for each model are displayed in odds ratios. As such, coefficients above one for a variable indicate that voting for the Democratic House candidate is more likely as the value of the variable increases. In turn, coefficients below one for a variable indicate that voting for the Democratic House candidate is less likely as the value of the variable increases.Footnote 13 Control variables are marked with a “Y” to indicate their inclusion or an “N” to indicate their exclusion from each model.Footnote 14

Table 3. Summary of models of the effect of racial resentment toward blacks on voting Democratic in house election

Odds ratios and robust standard errors are reported.

From the output in Table 3, we can see support for my hypotheses. In both models, racial resentment has a negative effect on a white voter's likelihood of voting for the Democratic House candidate (supporting H1); and the presence of a black candidate further decreases those odds (supporting H2).

The simplest way to evaluate my hypotheses is to run a “naive” model that excludes many of the controls called for in the literature. This model uses only candidate race, racial resentment, and the interaction term (excluding partisanship, incumbency, presidential approval, and yearly fixed effects). This “naive” approach, which excludes the theoretically grounded controls of the “full” model, shows a strong effect from racial resentment and a significant effect of the interaction between candidate race and racial resentment.

My “full” model, which I will be relying on for the remainder of this paper, incorporates the main interaction of candidate race and racial resentment, includes standard congressional voting control variables (not present in the “naive” model), and is applied to only the subset of districts where either black or white Democratic candidates could feasibly emerge. The substantive interpretation of the results of this model are largely in line with those that came before it, with racial resentment and the presence of a black candidate (particularly at higher levels of racial resentment) decreasing the odds of a white voter supporting a Democrat. The control variables in this model function entirely as expected. White voters who approve of President Obama are more likely to vote for a Democratic house candidate. Strong Democrats are much likelier to support a Democratic House candidate than a weak or lean Democrat, who in turn are more likely to support the Democratic candidate than an independent (who is more likely to vote Democratic than a weak Republican, etc.). Finally, incumbent Democrats are more likely to receive support than non-incumbent Democrats (see footnote 14).

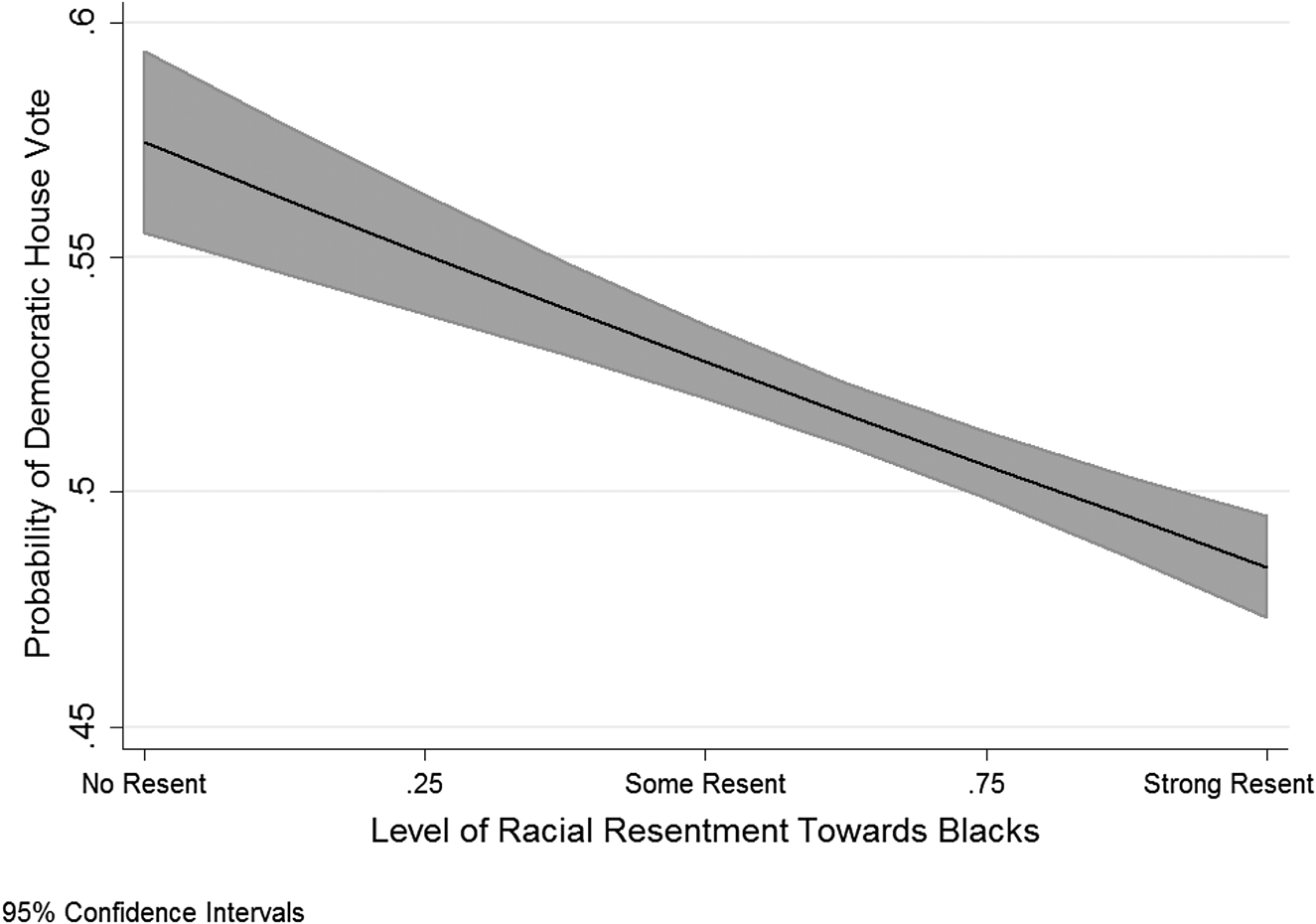

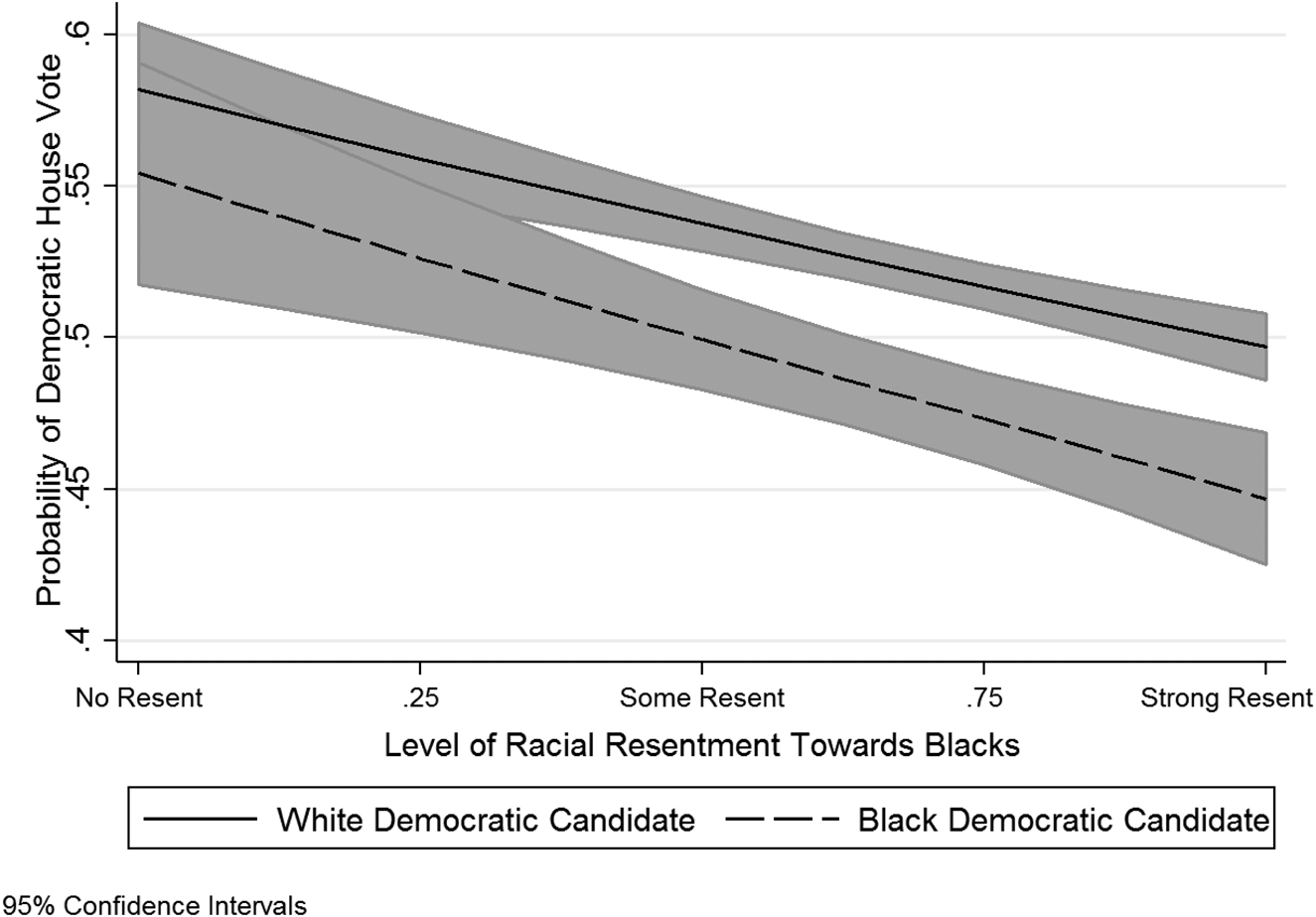

To get a better visualization of the “full” model results from Table 3, let us examine a pair of predicted probability plots. The first of these figures shows the effect of racial resentment attitudes on a white voter's likelihood of voting for the Democratic House candidate in the 2010–2016 elections (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Predicted probability of Democratic house by racial resentment vote among whites (black population restricted model) (95% confidence intervals).

This figure provides a visual confirmation of H1: white voters with higher levels of racial resentment are less likely to vote for Democratic candidates. Whereas white voters with the lowest score on the racial resentment index are nearly 60% likely to vote for the Democratic candidate, white voters with the highest level of racial resentment are less than 50% likely to vote Democratic. In short, no matter the race of the Democratic candidate, they clearly fare worse among white voters with higher levels of racial resentment toward blacks.

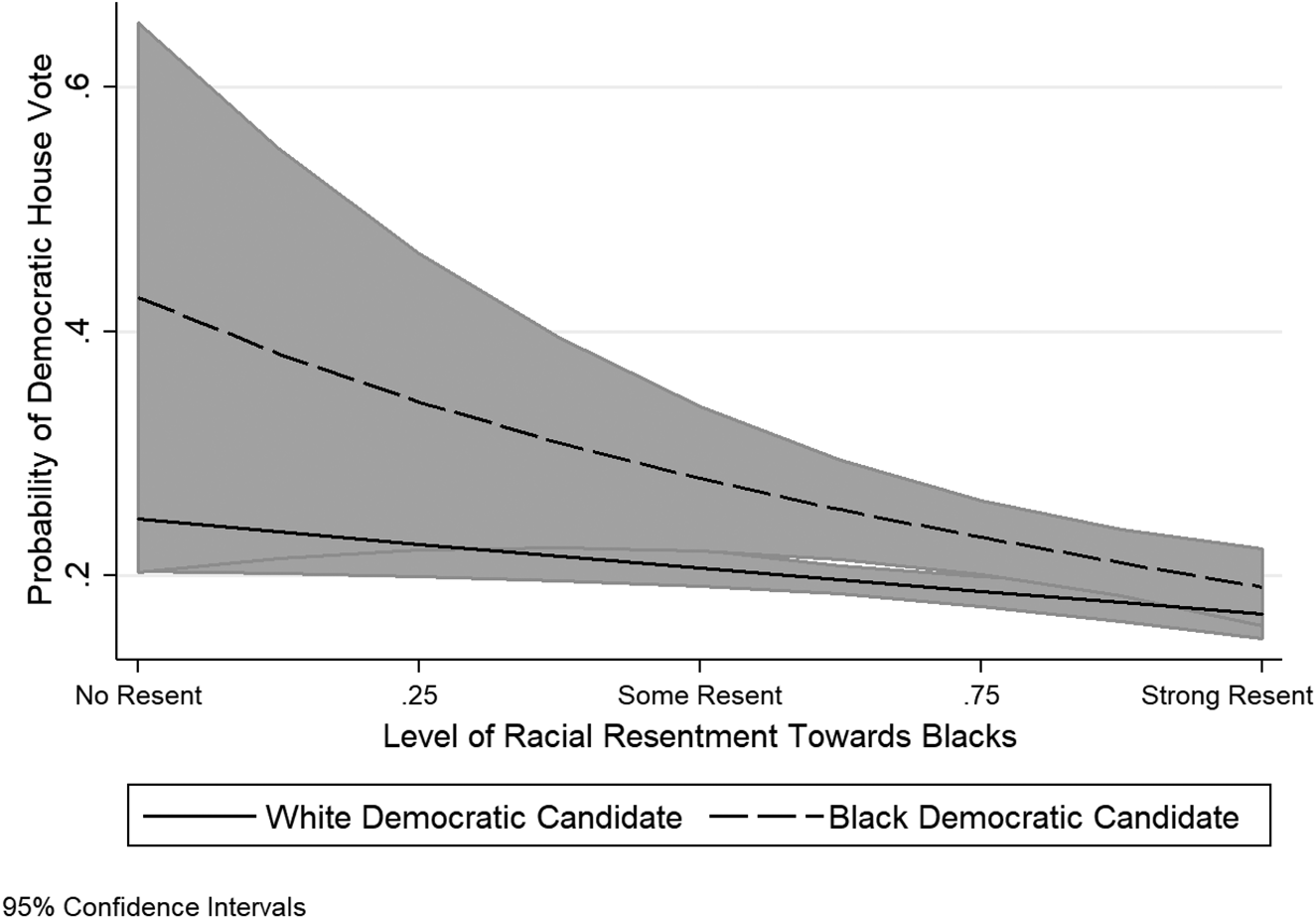

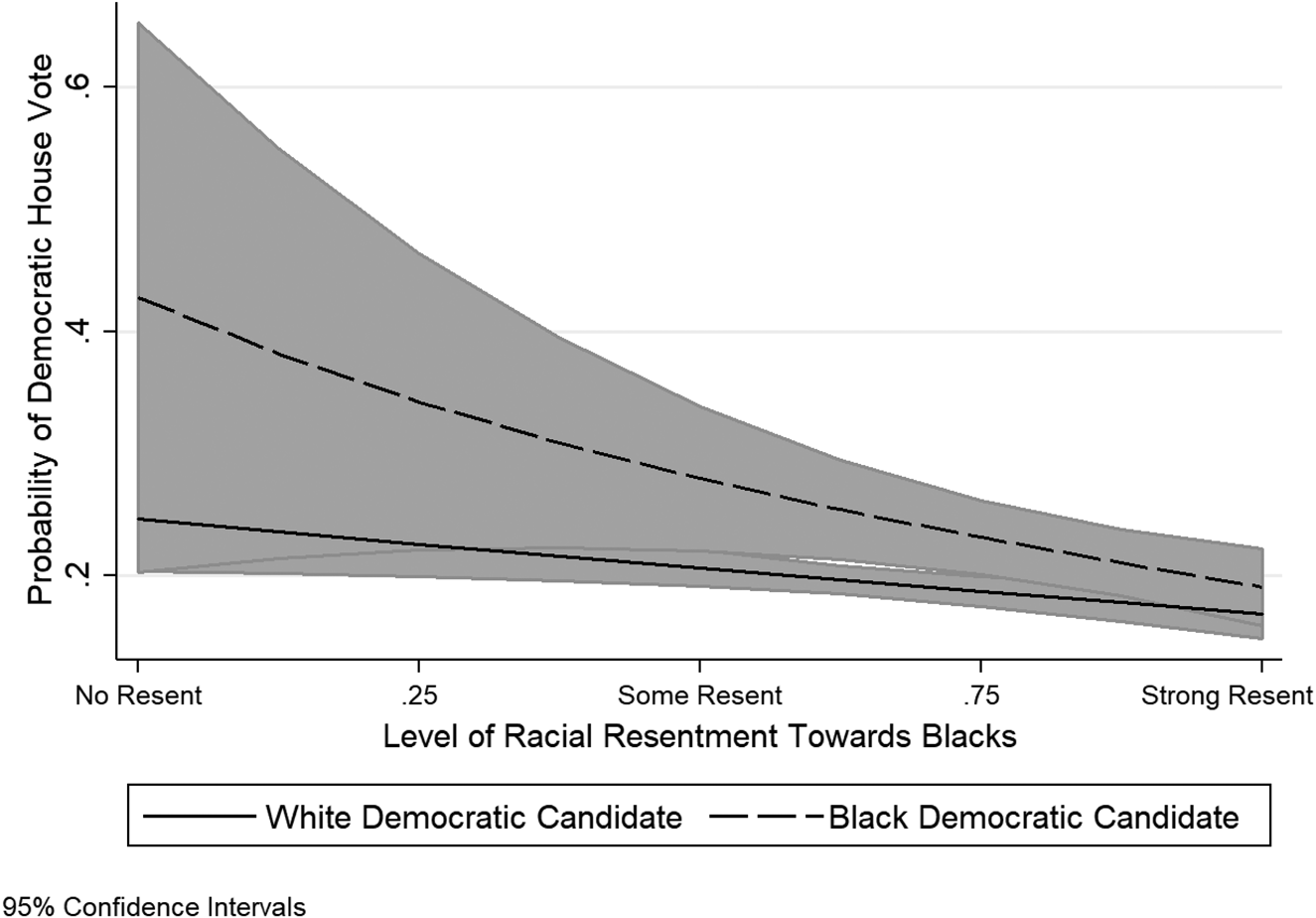

We can also visually evaluate H2 via a predicted probability plot. Recall that the “full” model (column 4) from Table 3 treats racial resentment and Democratic candidate race as an interactive effect. I hypothesize that voters with higher levels of racial resentment should not only be less likely to support Democratic candidates (H1), but they should also be less likely to support a black Democrat than a white one (H2). Figure 5 shows the effect of racial resentment on a white voter's likelihood of voting Democratic by the race of the Democratic candidate.

Figure 5. Predicted probability plot of racial resentment and candidate race on house voting among whites (black population restricted model) (95% confidence intervals).

Figure 5 provides visual confirmation of H2: at higher levels of resentment, white Democratic candidates fare better than black Democratic candidates. At the highest category of resentment (recall that almost 30% of whites fall into this “strong resentment” category), a white Democratic candidate is predicted by this model to have a 49% chance of getting a white citizen's vote whereas a black Democratic candidate is expected to have only a 42% chance of getting that vote. The effect shown in this plot accounts for partisanship, presidential approval, wave elections, and incumbency, as they are all included as controls in the “full” model.Footnote 15

An obvious concern that arises when viewing these results is that I am unduly restricting my sample to voters who were sure of the Democratic candidate's race. There is a real concern that the effect of the Democratic candidate's race on voters who do not know the candidate's race could be operating in a different direction than among voters who do report the candidate's race when asked (as in my models above). To address this concern, I re-administer the model only among white voters who do not identify the Democratic candidate's race.

Figure 6 demonstrates that though higher levels of racial resentment attitudes correspond with decreased likelihood of a vote for the Democratic House candidate among voters who do not report the race of the Democratic candidate, there is no statistically significant differentiation in vote choice depending on the candidate's race. This “placebo test” of sorts is in line with expectations, as we should not expect voters who do not know the race of the Democratic candidate to punish or reward them at the polls based on their race.

Figure 6. Predicted probability plot of racial resentment and candidate race on house voting among whites who do not know the Democratic candidate's race (95% confidence intervals).

In addition to this test, I also account for alternative explanations and confounders through a series of robustness checks. First and foremost, I examine whether voter and candidate ideology (and the distance between the two candidates) is confounding my results. I also check whether non-response bias on the question of candidate race is confounding my findings. I additionally test whether my findings are particular to the case selection of “black emergent” districts. Furthermore, I consider the possibility that racial resentment affects white voter attitudes and behavior differently in the South, perhaps as a function of the post-civil rights era “Southern Strategy” employed by the Republican Party (Brewer and Stonecash Reference Brewer and Stonecash2001). Another area of concern that I scrutinize is whether any possible effects of racial resentment are limited to Republican voters; a possibility suggested by Hajnal (Reference Hajnal2001). I also re-administer the models in competitive districts, to account for the possibility that voters in swing districts may have different motivators behind their vote choice. The effect of candidate quality is also tested. I also examine whether using reported (rather than actual) candidate race is driving my findings. Finally, I also test whether candidate gender affects my results. My model is robust to each of these potential challenges.Footnote 16

DISCUSSION

While white voters’ generalized aversion to black candidates may not be to blame for the challenges faced by black candidates, as Highton (Reference Highton2004), Sigelman et al. (Reference Sigelman, Sigelman, Walkosz and Nitz1995), and others argue, the results I report in this paper suggest that racial resentment attitudes among certain white voters are salient. As such, we perhaps ought to consider that candidate race in and of itself is not necessarily a key variable that contributes to vote choice among white voters. Rather, this study argues that racial resentment among white voters is a variable worth considering, both for its overall partisan effects as well as its effects for black Democratic candidates in particular.

To reiterate the results of my study, let us once again address the hypotheses proposed at the beginning of this paper. I find that high levels of racial resentment negatively affect a white voter's likelihood of voting for a Democratic candidate, regardless of that candidate's race (confirming H1). I also find that black Democratic candidates are less likely than non-black Democrats to receive votes from white voters with higher levels of racial resentment (confirming H2).

There are a variety of significant implications we can draw from these results. First, research by Edsall and Edsall (Reference Edsall and Edsall1992), Aistrup (Reference Aistrup1996), Brewer and Stonecash (Reference Brewer and Stonecash2001), Tesler (Reference Tesler2013) and others was correct: the Democratic party is electorally punished by white voters with racial prejudice toward blacks. Even after controlling for partisanship and presidential approval, Democratic candidates are still less likely to receive votes from white voters with high levels of racial resentment toward blacks than white voters with low racial resentment. Additionally, the findings I present here provide support for the research by Terkildsen (Reference Terkildsen1993), Moskowitz and Stroh (Reference Moskowitz and Stroh1994), Piston (Reference Piston2010), and others who argue that racial resentment has a negative impact on black candidates running for office. As my results show, black Democratic candidates fare even worse among white voters with anti-black racial prejudice than do white Democratic candidates.

The findings I present in this paper also have significant normative implications for black congressional underrepresentation. Since black Democratic candidates suffer a disproportionate amount in the face of racial prejudice, this supplies one possible explanation for the underrepresentation of blacks in Congress. Black Democrats may simply be losing races that could have been winnable by white Democrats, who do better among white voters with higher levels of racial resentment. Furthermore, it is also possible that Democratic party elites rationally choose to not recruit black candidates in swing districts, knowing that nominating a black House candidate will cost them at the polls. In short, the problem of black underrepresentation in congressional elections may not be simple elite failure, wherein the parties have devoted insufficient effort to recruiting and grooming black candidates (though this is certainly possible). Instead, black Democratic candidates not only face obstacles to nomination, but also unique electoral penalties when they do receive their party's nomination.

The finding that racial resentment hurts white Democratic candidates in addition to black ones also has implications for the study of racial partisan realignment in the American electorate. As Carmines and Stimson (Reference Carmines and Stimson1989), Edsall and Edsall (Reference Edsall and Edsall1992), Brewer and Stonecash (Reference Brewer and Stonecash2001), Valentino and Sears (Reference Valentino and Sears2005), and many other authors establish, partisan realignment has occurred strongly along racial lines in the post-civil rights era, as the Democrats and Republicans have become firmly associated with racial liberalism and conservatism respectively; leading blacks to align with the Democratic party and racially conservative whites (especially in the South) to align with the GOP. This paper's finding that Democratic candidates are electorally penalized by racially conservative white voters helps explain how racial realignment has manifested itself in US elections. Not only have racial conservatives sorted into the GOP and vice versa (see Figure 3), but even those racially conservative white voters who have not sorted into the Republican Party are less likely to support Democratic candidates than white voters with low levels of racial resentment.

Future research may also be able to use counter-factual simulations to gain additional leverage from the models presented in this paper. While it is theoretically interesting to see that racial resentment can affect voting behavior (as I have already shown), future research could identify specific electoral contests where racial resentment attitudes swayed the outcome. By simulating electoral data and varying the distribution of racial resentment attitudes among white voters in the simulation, I could potentially create scenarios that demonstrate how differing levels of racial resentment in the electorate could change the result of congressional elections.

While the research presented here shows a relationship between racial resentment toward blacks and vote choice among whites, the contributions of other authors on the subject of racial resentment also merit additional consideration in future work. Hajnal (Reference Hajnal2001), for instance, finds that incumbent black mayors tend to decrease racial tension and increase racial sympathy in the electorate (though not among Republicans). As such, we might perhaps consider that not only does racial resentment affect black candidates who are in or seeking office, but that the presence of black officeholders may be reciprocally decreasing overall levels of resentment. In a somewhat similar vein, Citrin, Sears and Green (Reference Citrin, Sears and Green1990) find that the effect of a candidate's race on voter behavior is contingent upon a host of factors, including the candidate's record and campaign style. Black candidates such as Tom Bradley, who ran for CA governor in 1982, who attempt to lower the ethnic relevance of their campaigns may be differently affected by racial resentment than black candidates who choose to include racial and ethnic cues in their campaigns and messaging. New work by Tolbert, Redlawsk and Gracey (Reference Tolbert, Redlawsk and Gracey2018) that finds a mediating effect of campaign-generated enthusiasm on the electoral effects of voter racial resentment also indicates that racial resentment does not affect every black candidate equally.

To conclude, racial resentment among white voters both negatively affects Democratic candidates and additionally harms black Democratic candidates. The combination of partisan racial realignment in recent decades in conjunction with the continued salience of race in national politics has likely contributed to the ongoing underrepresentation of blacks in Congress. Considering the evidence presented in this paper, it is perhaps not surprising that there have been so few black Republican House members in recent years, given the relatively high levels of racial resentment among white Republican voters.

While exceptionally charismatic candidates such as Barack Obama may be able to overcome white voters’ latent concerns about their race by generating intense emotional enthusiasm for their campaigns (Lewis-Beck, Tien and Nadeau Reference Lewis-Beck, Tien and Nadeau2010; Redlawsk, Tolbert and Franko Reference Redlawsk, Tolbert and Franko2010; Tolbert, Redlawsk and Gracey Reference Tolbert, Redlawsk and Gracey2018), this phenomenon is the exception, not the rule. Despite proclamations to the contrary, the election of Barack Obama in 2008 did not signal the start of a post-racial era in American politics. For the 2010–2016 elections, white voters’ negative racial attitudes toward blacks continued to have an effect on their congressional vote choice. If racial resentment among whites is acting as a barrier to Democratic and black House members’ electoral success, as this research suggests, then we might expect the fortunes of the Democratic Party, and black Democratic candidates in particular, to shift as racial politics in the United States continue to evolve.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2019.34