In the past decade, social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat and YouTube have expanded rapidly as online public spaces for political expression.Footnote 1 Through these platforms, ordinary citizens are articulating their opinions on various political issues, sharing like-minded political opinions from their social networks and engaging in active debates about political events. Memes, Facebook or Instagram live videos, and political commentary videos are some examples of creative audio-video political content generated in the process. Politicians too are exploiting these new outlets to communicate their political positions, to shape their own political images and to correspond with the masses. Hardly a day goes by without the president of the USA, Donald Trump, unleashing the next political news cycle through his controversial tweets.

Drawn by the rich amount of publicly available empirical data from these online social media platforms, political scientists have sought to use these data to answer important questions in the discipline. For instance, scholars have examined how authoritarian governments censor online expression aimed at generating collective action (King et al. Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013, Reference King, Pan and Roberts2014), and how they attempt to distract their citizens instead of engaging with them (King et al. Reference King, Pan and Roberts2017). Other scholars have documented how a politician's gender influences their communication style (Evans and Clark Reference Evans and Clark2016), how social media use increases awareness of electoral fraud in electoral autocracies (Reuter and Szakonyi Reference Reuter and Szakonyi2015) and how campaigning on social media actually wins votes and elections (Bright et al. Reference Bright2018).

Yet, as more scholars make use of social media data to make descriptive or causal inferences, greater attention must be paid to the data-generation process. Bias in the data-generation process can lead to inaccurate inferences (Mellon and Prosser Reference Mellon and Prosser2017; Nyblade et al. Reference Nyblade, O'Mahony and Sinpeng2015). Indeed, in a research note published as part of a symposium on ‘Technology, Data, and Politics’, Sheena Greitens (Reference Greitens2013) argues that cross-national variation in a state's information and communication technology (ICT) regulatory policies shape how empirical data on the internet are generated. For example, given China's extensive censorship bureaucracy, it would be unwise for scholars to use publicly available already-censored Chinese social media data as empirical evidence for testing hypotheses. The same is true for any other state that employs extensive online censorship. At the minimum, scholars must first understand how the political context truncates or structures their data, before developing research questions and research designs to use the data. As Greitens (Reference Greitens2013: 264) cautions, ‘understanding the structure and potential biases of the data is the only way for scholars to make precise and accurate causal claims’.

This article argues that self-censorship of political expression on online social media platforms is a crucial way in which social media data can be truncated. When online self-censorship occurs, politically engaged citizens avoid expressing any political preferences and opinions on social media platforms at all, even if they have a strong private desire to do so (Loury Reference Loury1994). This definition of self-censorship is conceptually distinct from the concept of preference falsification (Kuran Reference Kuran1991). The latter concept is defined as a divergence between an individual's public and private preferences. For instance, an individual may publicly profess support for an authoritarian regime but may actually privately prefer to vote for an opposition party if provided with a choice. With self-censorship, however, an individual makes a decision to not profess any political preferences and opinions at all.

I propose a simple expected utility model for explaining who self-censors on social media: an individual self-censors when he or she expects the costs of online political expression to outweigh its benefits. In other words, social media self-censorship occurs when the expected pay-off for expressing one's political opinion online is negative. Assuming that the benefits of online political expression, such as self-gratification, is constant across politically engaged social media users, the degree of self-censorship is likely to vary depending on the expected costs of online political expression. The expected costs to online political expression are, in turn, primarily a function of an individual's expected probability of encountering state-initiated repression, as well as the actual penalty of repression.

Consequently, I hypothesize that politically engaged social media users who have higher incomes are likely to perceive higher costs to online political expression, and are therefore more likely to self-censor, as compared to lower-income politically engaged social media users. Citizens with higher incomes have more to lose in terms of current income, future incomes and valuable personal reputations if they are ever publicly harassed, arrested, prosecuted and incarcerated for their online speech by the state. Their perceived costs of the actual penalty of repression will be very high. They are hence less likely to express their political opinions online. Lower-income citizens who have less to lose will perceive the actual material penalty of encountering repression to be lower. They will be more likely to take the risk to reap the benefits of making their political opinions known online.

Furthermore, cross-national variation in a state's degree of online repression is likely to condition the relationship between the incomes of politically engaged social media users and the degree of self-censorship. In countries where the state is very aggressive in criminalizing online speech and prosecuting online critics, the probability of getting caught and punished is likely to be very high. High-income politically engaged social media users will be more afraid of state-initiated prosecution for anything that they say online. Hence, we can expect the correlation between the incomes of politically engaged social media users and self-censorship to be strong. In countries where the state only pursues moderate or low levels of online repression, then the correlation is likely to be weak or non-existent. High-income politically engaged social media users are more likely to believe that they can escape repression and get away with expressing their political opinions online.

For empirical evidence on cross-national variation in online repression and self-censorship, I turn to Southeast Asia. Studying the region on this issue is suitable to the extent that the region's countries exhibit representative variation in regime type at different levels of development, with varying historical antecedents and pressures for criminalizing online political expression. Southeast Asia has also been generally neglected in the political science literature on technology and its effects on politics because other world regions, particularly Russia and the Middle East, have seen more prominent episodes of internet technology contributing to offline mobilization and political upheaval (Gainous et al. Reference Gainous, Wagner and Ziegler2018; Lynch Reference Lynch2011; Pearce and Hajizada Reference Pearce and Hajizada2014; Reuter and Szakonyi Reference Reuter and Szakonyi2015). I rely on data from Freedom House's Freedom on the Net reports alongside data from the 2014–16 wave of surveys by the Asian Barometer project to test my hypotheses. Through examining how 10,216 citizens in eight Southeast Asian countries respond to a new list of questions about how they engage on social media and the internet, I find that higher-income politically engaged social media users are indeed less likely to express their political opinions online on social media. This correlation was especially strong in Thailand and Myanmar, two of the three Southeast Asian countries that have the highest levels of online repression. Vietnam was the only exception. As expected, in the five other Southeast Asian countries where the criminalization and prosecution of online speech is moderate or low, the correlation is non-existent.

Beyond the immediate methodological implications for researchers, the twin phenomena of online repression and self-censorship also have crucial implications for the contemporary study of democracies and autocracies around the world. In autocracies where there is less protection for freedom of expression, state-initiated online repression targeting anti-regime critics induces self-censorship among other fellow anti-regime critics (Bhasin and Gandhi Reference Bhasin and Gandhi2013; Carey Reference Carey2009; Davenport et al. Reference Davenport, Johnston and McClurg Mueller2005). This outcome allows an autocratic government to enhance its perceived popularity online, which enhances and entrenches its overall legitimacy and political authority (Gerschewski Reference Gerschewski2013, Reference Gerschewski2018). Even in democracies where there are typically greater legal protections for freedom of expression, populist leaders keen on subverting traditional democratic constraints oftentimes resort to repression to silence their critics (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Gandhi Reference Gandhi2018; Jones and Matthijs Reference Jones and Matthijs2017; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Pepinsky Reference Pepinsky2017; Waldner and Lust Reference Waldner and Lust2018). In states such as Turkey, Hungary, Poland and Brazil, these repressive leaders have shrunk the public space for civil discourse, increased political polarization and generated distrust in democratic institutions, leading those countries down a dangerous path of democratic erosion (Mechkova et al. Reference Mechkova, Lührmann and Lindberg2017). Unpacking how state-sponsored online repression leads to self-censorship is critical in clarifying how executive aggrandizement engenders democratic backsliding.

The rest of this article proceeds as follows: I first discuss how states, especially autocratic regimes, are developing new laws to regulate and criminalize online speech. I use several examples from Singapore to illustrate the modus operandi of online repression. Second, I propose a simple expected utility model of online self-censorship, arguing that high-income politically engaged social media users are more likely to self-censor, and explaining why the correlation is likely to be strong in countries where the severity of online repression is high. Third, I describe variation in the criminalization and public persecution of online political expression across Southeast Asia. Finally, I present evidence of online self-censorship using the Asian Barometer data. A short conclusion summarizes the most important findings and discusses the implications for future research on backsliding democracies and entrenched autocracies.

Online repression and self-censorship

The existing literature on the nexus between the state and cyberspace has largely focused on the variety of mechanisms through which the state controls the internet (Deibert Reference Deibert2015; Deibert et al. Reference Deibert, Palfrey, Rohozinski and Zittrain2012; Diamond and Plattner Reference Diamond and Plattner2012; Farrell Reference Farrell2012; Hellmeier Reference Hellmeier2016). Scholars have examined state pressure on internet service providers (ISPs) to selectively block politically sensitive websites such as online news portals and have studied the ‘just-in-time’ censorship of controversial topics on social media. Conversely, many scholars have also studied the numerous ways in which online activists have resisted state control and have even successfully brought about various degrees of liberalization and democratization (Goh Reference Goh2015; Pearce and Hajizada Reference Pearce and Hajizada2014; Reuter and Szakonyi Reference Reuter and Szakonyi2015; Ruijgrok Reference Ruijgrok2017; Tang and Huhe Reference Tang and Huhe2014). Online activists have pushed back against state control by documenting and highlighting government transgressions to the public through alternative news outlets, frequently using dark humour and memes to undermine political authority. Many also serve as information providers to coordinate and lower the costs of offline collective mobilization against the regime.

In this ongoing battle between online activists and the governments that seek to control them, during this time period which Ronald Deibert and his co-authors (Reference Deibert, Palfrey, Rohozinski and Zittrain2012) dub the ‘access contested’ era, governments – especially autocratic regimes – have increasingly resorted to the legal criminalization and prosecution of online political speech to gain an upper hand against online activists. Because governments claim legitimacy and monopoly over the use of violence in a country, they maintain discretion to deploy their coercive powers to harass, intimidate, arrest, charge and incarcerate online critics. The purpose is to silence these online activists, forestall collective action, as well as to spread fear in their fellow online sympathizers (Deibert Reference Deibert2015; Gainous et al. Reference Gainous, Wagner and Ziegler2018; King et al. Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013, Reference King, Pan and Roberts2014, Reference King, Pan and Roberts2017). When the public observes the criminalization of critical online speech and the incarceration of online activists, they self-censor to avoid similar negative repercussions.

In general, the modus operandi of a government's online repression strategy is not extensive and arbitrary arrest and incarceration. Governments typically first use existing legislation, such as existing sedition laws or defamation laws, or create new legislation, such as Thailand's Cyber Crimes Act, to criminalize critical online political expression. They often legitimize and justify rhetorically these laws as necessary to maintain societal law and order (Pepinsky Reference Pepinsky2017). These ‘catch-all’ laws are typically broadly worded to give incumbent governments wide discretion to define critical speech freely as somehow threatening to the state or society, therefore authorizing legal prosecution and incarceration. A 2017 report by the Association for Progressive Communication, a global network of non-governmental organizations dedicated to supporting a free internet, noted that both autocracies and democracies in Asia are using existing colonial-era laws and rapidly developing new laws to target and criminalize online speech (Association for Progressive Communications 2017). The multiple overlapping legal provisions from existing laws and new regulations serve to eliminate the possible ‘escape routes’ of the online critics. They ensure that the state's failure to charge critics via one law can always be supplanted by charging them under another law.

Once governments are empowered with the necessary legislative provisions, they then target specific high-profile online critics for harassment, arrest, prosecution and incarceration. A most recent example is the very public investigations into alleged computer crimes committed by Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, a Thai autoparts tycoon who founded the Future Forward Party to contest in the general election against the Thai junta (Financial Times 2018; Senawong Reference Senawong2018). States target these high-profile individuals not only because they can achieve the maximum public impact in spreading fear and self-censorship, but also because they desire to be perceived by the public as exercising self-restraint in deploying the state's coercive power. When states employ coercion indiscriminately and arbitrarily, they risk catalysing mass resistance and opposition. If they use ‘calibrated coercion’ to target specific individuals and ‘get the job done with as little force as necessary’, then they maximize the benefits of coercion while minimizing its attendant costs (George Reference George2007; Liu Reference Liu2014; Sinpeng Reference Sinpeng2013).

Additionally, legal provisions for online repression provide a veneer of legitimacy for governments, both democratic and autocratic, against their international and domestic critics. Political leaders can more easily justify the prosecution and incarceration of online activists not only because these activists are deemed a threat to national security and stability, but also because legislation passed by majority rule makes such repression legitimate. The deeper operative logic is that constraining the individual freedom of expression is legitimate as leaders have to prioritize the broader public interests of the country which only they, via majority rule, can define. In this sense, then, political leaders contort the spirit of legislative and legal institutions to rule through law rather than respect the rule of law (Ginsburg and Moustafa Reference Ginsburg and Moustafa2008; Jayasuriya Reference Jayasuriya1996; Rajah Reference Rajah2012; Rodan Reference Rodan1998). Legally justified repression via majority rule thus represents a key mechanism through which autocracies are entrenched and democracies are eroded.

To better illustrate the operational sophistication of online repression, consider Singapore's very recent history of criminalizing and prosecuting online political expression. Contemporary Singapore is a robust electoral authoritarian regime. The dominant People's Action Party (PAP) has governed the country since 1959 (Barr and Skrbiš Reference Barr and Skrbiš2009; Mauzy and Milne Reference Mauzy and Milne2002; Rajah Reference Rajah2012; Slater Reference Slater2012; Tremewan Reference Tremewan1994). In recent years, at least three prominent online activists have either been arrested and incarcerated, or at least been served papers. In 2014, blogger Roy Ngerng was sued for defamation by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong for implying in his blog that the prime minister was guilty of criminal misappropriation of monies from the city state's pension funds (Sim Reference Sim2015). In the end, Ngerng was found guilty of defamation and ordered to pay more than S$150,000 in damages to the prime minister. In 2015 and 2016, teenage YouTuber Amos Yee was charged for uploading videos that ‘wounded the religious feelings of Muslims and Christians’ as well as for offending viewers with remarks and images that criticized Singapore's late prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew (Chia Reference Chia2016; Chong Reference Chong2015). He was sentenced to about 50 days in jail in total for the offences he committed in the two years.

Even more surprising is the more recent prosecution in 2017 of Li Shengwu, nephew of Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and grandson of former prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew (Wong Reference Wong2018). On 15 July 2017, Li shared on Facebook, using a ‘Friends Only’ setting, a Wall Street Journal article. In sharing that article, Li commented that ‘the Singapore government is very litigious and has a pliant court system’. Within a week, the Attorney General's Chambers (AGC) began court proceedings to start a contempt of court investigation into his comments. Singapore's AGC subsequently argued that even though his Facebook sharing settings were set to ‘Friends Only’, it does not entitle Li to claim privacy, and that his comments ‘pose a real risk of undermining public confidence in the administration of justice’ (Seow Reference Seow2017).

These three critics – Ngerng, Yee and Li – were all prosecuted under different kinds of existing laws that had no direct relation to online speech in particular. Ngerng's case was a private lawsuit initiated by the prime minister under Singapore's existing defamation laws. Yee was charged under Section 298 of the Penal Code for deliberately intending to wound the religious and racial feelings of a person. Li is very likely to be charged under Section 3 of Singapore's Administration of Justice (Protection) Act of 2016, which criminalizes any act that undermines the public perception of the judiciary, broadly speaking.Footnote 2 Not only do their cases demonstrate that critical online speech is treated no differently from critical offline speech, they also signal to anti-regime critics that multiple legal provisions can be used to target them if necessary.

Unsatisfied with existing laws narrowing the freedom of speech, however, the Singapore government has recently embarked on an initiative to write new legislation regulating what it terms ‘deliberate online falsehoods’ or DOFs. A Green Paper presented to the Singapore Parliament in January 2018 argued that there has been a growing trend of falsehoods being spread through online technologies to ‘weaken and damage societies’ ‘all over the world’.Footnote 3 Parliament then formed a Select Committee to investigate the DOF phenomena and to report on ‘any specific measures, including legislation, that should be taken for the country to prevent and combat online falsehoods’.Footnote 4 As of this writing, no legislation has been proposed and passed. But the month-long public hearings in March 2018 revealed extensive debates and concerns about the potentially broad discretion which the government and attorney general have to define what constitutes a DOF as well as the specific criminal and punitive measures that can be taken against people who were deemed to be spreading DOFs.

Who self-censors?

It is clichéd to say that social media users in any country are not representative of the population of that country. To deal with this problem of the non-representativeness of social media users, researchers can likely use standard statistical weighting techniques to correct the sample data for the broader population. The problem of self-censorship, however, is distinct from the problem of the non-representativeness of social media users. Among social media users, there are those who are politically engaged, whom I define as possessing an above average level of political knowledge, and those who are not politically engaged (Carpini and Keeter Reference Carpini and Keeter1993; Galston Reference Galston2001). It is among the politically engaged social media users in which self-censorship occurs. To be more explicit, even though politically engaged social media users are more likely than the average social media user to express their political opinions online, self-censorship among them depresses the observed likelihood and frequency of online political expression. As a result, any observed online political expression on social media is probably going to be a truncated subset of the potential distribution of online political expression.

No existing theory articulates who self-censors for what reasons. I propose a simple expected utility model as a first step towards helping researchers study the phenomenon more rigorously. I propose that self-censorship more likely occurs among politically engaged social media users who expect the costs of online political expression to outweigh its benefits. In other words, if the expected pay-offs to online political expression are negative, then politically engaged social media users will self-censor and choose not to express their political opinions online.

To be more precise and explicit about the pay-off function, I propose that an individual's expected utility for online political expression can be written in a simple formula:

where ‘express’ stands for an individual's specific instance of online political expression, and ‘repression’ stands for an individual's encounter with state-initiated repression. EUexpress is an individual's expected utility for one specific instance of online political expression; Bexpress is an individual's expected benefits from online political expression; Cexpress refers to the cost to an individual of expressing that particular opinion online; p repression represents the probability of an individual actually encountering state repression; and Crepression represents the actual costs to the individual once he or she has encountered state repression.

Bexpress is typically an intangible reward for an individual for making one single instance of political expression online. For instance, an individual may feel emotionally gratified for sharing a tweet or a Facebook post that corresponds to his or her political beliefs, and for the ‘Likes’ that his or her friends in the same social network leave on that post. Cexpress is more material, but also often implicit. It can refer to the cost of the smartphone that one has to pay to access the internet and social media, as well as the cost of time that one incurs in writing a social media post. As the costs of access to the internet decrease with technological improvements, and as the upfront fixed costs incurred in buying a smartphone or a computer are distributed over the long life of the device, then we can expect Cexpress to be very small for an active social media user for every instance of online political expression. In short, the actual material cost of making one single tweet is infinitely small.

If a politically engaged social media user has zero expectations of encountering state repression at all, then the user's likelihood of online political expression will simply be driven by his or her individual perceptions of Bexpress and Cexpress. We can expect he or she will express their political opinions online as long as Bexpress is larger than Cexpress. However, if the individual observes a state's passing of legislation criminalizing online speech and the public prosecution of online activists, then that individual will have to consider p repression and Crepression.

Politically engaged social media users with higher incomes will perceive the actual penalty of repression, Crepression, to be very large, as compared to counterparts with lower incomes. If they do indeed get arrested, charged and incarcerated for any particular social media post, then they can expect to lose their current high incomes, anticipated very large future incomes, as well as their reputation in their respective fields. That is, they stand a real risk of losing the great bulk of all the comfortable material life that they have ever worked for. In contrast, lower-income politically engaged social media users will perceive Crepression to be smaller, even if they are ever prosecuted by the state. Their current incomes, future incomes and long-term reputation are considerably less valuable. Accordingly, assuming Bexpress, Cexpress and p repression are constant for any two politically engaged individuals, the higher-income individual expecting a greater value for Crepression is more likely to experience negative utility for online political expression. The lower-income individual with a lower value for Crepression may still expect an overall positive utility for expressing their political opinions online. Thus, even when both high- and low-income politically engaged social media users observe the same state criminalization and prosecution of online speech, it is those with high incomes who are more likely to self-censor. This perspective yields the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

High-income politically engaged social media users will be less likely to express their political opinions online, as compared to lower-income politically engaged social media users.

In addition, we can also expect the correlation between income and self-censorship to vary across countries where there are different degrees of online repression. In countries where there is severe state-initiated prosecution and incarceration of critical online activists, then an individual in that country will expect p repression to be high. Frequent, prominent public prosecutions of online activists are likely to provoke fear in high-income politically engaged social media users that they will encounter similar fates if they make anti-government criticisms, resulting in higher rates of self-censorship. In countries where there is only moderate to low state criminalization of online speech, then an individual in that country will expect p repression to be low. Less frequent public prosecutions of online activists may lead citizens to think that there is broader state tolerance of critical online speech. They can therefore ‘get away’ with expressing their political views. Another reason may be that stronger legislative protections for the freedom of speech emboldens citizens to express their political views. Thus, even if Crepression is high among high-income politically engaged social media users, the low probability of getting persecuted in a low-repression country means that the overall expected utility of expressing one's political opinions online may still be positive. This attention to cross-national variation leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2:

In countries where the criminalization of online political expression is severe, the inverse relationship between income and the likelihood of online political expression will be strong. In countries where the criminalization of online political expression is moderate or low, the inverse relationship between income and the likelihood of online political expression will be weak or non-existent.

There are two important caveats to this simple expected utility model of self-censorship. First, an important assumption is that the individual's probability of encountering state repression does not vary with income. For instance, high-income social media users may be less likely to encounter the full brunt of repression as compared to lower-income users because the criminal justice system is biased in favour of them. This then mitigates the effect of Crepression. While there is no systematic evidence comparing the degree to which a state's criminal justice system is biased one way or another, anecdotal reports of governments that criminalize critical online speech suggest that they are much more interested in curtailing an individual's capacity to incite collective action against the state, regardless of their income. Singapore's persecution of Ngerng, a middle-income public hospital employee, Yee, an unemployed teenager, and Li, an assistant professor at Harvard University, reflect the regime's non-discriminatory approach to an activist's social status. In the next section examining Southeast Asia's various regimes, a similar narrative about their emphasis on targeting dissent, rather than social status, emerges.

Second, the model is agnostic as to the degree to which individuals are dependent on the state for their livelihoods. In the abstract, if a state has extensive controls over the political economy of a country, then politically engaged social media users may be much more wary of expressing their political opinions regardless of their income level (Rodan Reference Rodan1998; Tremewan Reference Tremewan1994). State persecution and incarceration could mean a lifetime of economic and social marginalization, as reflected in Ngerng's subsequent emigration to Taiwan, Yee's asylum in the US, and Li's self-imposed exile in the US. Where a state has less command and control over the economy and society, then social media activists may be less deterred from online expression. Even if they are harassed and persecuted by the state, they are more likely to be able to recover their previous lives with support from fellow anti-regime allies. Whether the political economy of a regime conditions the effect of online repression and self-censorship is an important concern that is beyond the scope of this article. The exceptional case of Vietnam discussed below suggests that it warrants serious investigation in future research.

Online repression across Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia provides the setting with which to observe variation in both online repression and online political expression. Data measuring the degree of online repression in the region come from Freedom House's Freedom on the Net (FON) reports. Of the 10 countries in the region, Freedom House tracks the state's policies and regulations governing the internet in eight of them – Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines. Only the small, insular countries of Laos and Brunei are excluded. The FON reports track state policies on the internet across 100 different questions. The 40 questions that are most relevant to our inquiry in this article – the criminalization of online speech – are grouped under the ‘Violation of User Rights’ category. The score for this particular category ‘measures legal protections and restrictions on online activity; surveillance; privacy; and repercussions for online activity, such as legal prosecution, imprisonment, physical attacks, or other forms of harassment’ (Freedom House 2017: 28).Footnote 5 Specifically, Freedom House asks its expert in-country assessors to answer the 40 questions within eight question themes in this category such as ‘Are there laws which call for criminal penalties or civil liability for online and ICT activities?’, ‘Are individuals detained, prosecuted or sanctioned by law enforcement agencies for disseminating or accessing information on the internet or via other ICTs, particularly on political and social issues?’, and ‘Are bloggers, other ICT users, websites, or their property subject to extralegal intimidation or physical violence by state authorities or any other actor?’.

Figure 1 shows the scores for the ‘Violation of User Rights’ category across Southeast Asia over the five years between 2014 to 2018. A casual inspection of these scores shows that there is some face validity. Vietnam and Thailand, ruled by a single party and a military junta respectively, have the highest scores at 35 and 32 for the year 2018. Both countries have had particularly bad instances of prosecuting online activists in recent years. In Vietnam, Human Rights Watch's 2018 annual report noted that ‘Vietnam's human rights situation seriously deteriorated in 2017’ primarily because ‘authorities arrested at least 21 rights bloggers and activists … for exercising their civil and political rights in a way that the government views as threatening national security’ (Human Rights Watch 2018). The country's newly passed cybersecurity laws also severely narrow online freedom of speech by imposing regulatory guidelines on social media firms to store user data locally, release information to the government whenever it requests, and remove any critical content that authorities demand (National Public Radio 2019). Thailand's military junta has also relied on existing sedition laws alongside its infamous Computer-Related Crime Act to prosecute online critics. Most notably, veteran journalist Pravit Rojanaphruk and ex-ministers Pichai Naripthaphan and Watana Muangsook were charged for their critical Facebook commentaries in August 2017 (Human Rights Watch 2017). More incredible was the arrest and prosecution in March 2016 of a housewife who had posted a picture on Facebook of herself with a red plastic bowl. She was apparently inciting sedition because the bowl was inscribed with Thai New Year greetings from former Prime Ministers Thaksin and Yingluck Shinawatra (Holmes Reference Holmes2016). In Thailand, both the rich and the poor can incur the wrath of a repressive authoritarian government.

Figure 1. Freedom House's Freedom on the Net ‘Violation of User Rights’ Scores

Note: 0 = most free; 40 = least free.

Myanmar has the third highest ‘Violation of User Rights’ scores and has seen its scores increase from 25 in 2014 to 30 in 2018. There are conflicting reports of the exact severity of the prosecution of online speech under the newly elected National League of Democracy (NLD) government, but almost all agree that the frequency is fairly high. Freedom House's FON report found at least 61 cases criminalizing online speech filed under the current NLD government under the broadly worded Telecommunications Law (Freedom House 2017: 649–650), while another local advocacy group found 73 cases from April 2016 to August 2017 alone (Association for Progressive Communications 2017: 95). The more prominent of these cases involved journalists being prosecuted and jailed for posting on Facebook allegations of government corruption, as well as criticism of the government by various political parties.

Cambodia, Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia make up the cluster of countries that have more moderate violations of individual rights to the freedom of online expression. In all of these countries, the frequency of prosecution of critical online speech is much lower. The state deliberately targets only a small number of key activists for legal prosecution. Cambodia has seen its scores rise the fastest, from 18 in 2014 to 26 in 2018. This reflects the increasing repression by Hun Sen's government in the run-up to local elections in June 2017 and national elections in July 2018. Opposition politicians from the Cambodian National Rescue Party and the Khmer Power Party were arrested, charged and incarcerated for critical comments that they made on Facebook (Association for Progressive Communications 2017: 33–49). The Malaysian government under the long-ruling Barisan Nasional and Prime Minister Najib Razak focused on eliminating viral satirical artworks that criticize the government for its corruption scandals.Footnote 6 Well-known online satirical comedians such as Zunar and Fahmi Reza were among the most prominent online activists targeted. The Singapore government, as previously mentioned, has sought to selectively target only a few prominent online critics who have amassed a sizeable online following. In Indonesia, most charges brought against social media users appear to involve private disputes over defamation or criticisms of religious scholars (Freedom House 2017: 459–465). State-sponsored prosecution appeared to be low or non-existent.

Finally, in the Philippines, there were few incidences of state-sponsored criminal prosecution of online speech as well as no apparent acts of violence and intimidation. There were more than 1,000 cybercrimes recorded, however, with the top category of online libel disputes seeing the highest number of cases (Freedom House 2017: 691–695).

In sum, there is significant cross-national variation in state-initiated criminalization and prosecution of online political expression across Southeast Asia. The situations in Vietnam, Thailand and Myanmar are most severe. Cambodia, Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia see much more moderate and targeted incidents. The Philippines sees almost no instances of state criminalization of online speech. Hence, the arguments articulated in the previous section suggest that we should expect self-censorship among high-income politically engaged social media users to be highest in Vietnam, Thailand and Myanmar, while being weak or non-existent in the other five countries.

Assessing self-censorship in Southeast Asia

Data and dependent variables

The Asian Barometer project is coordinated by the Center for East Asian Democratic Studies at the National Taiwan University and is part of the Global Barometer network of surveys. The latest wave of surveys was conducted between 2014 and early 2016. All eight Southeast Asian countries discussed thus far – Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines – were surveyed. From the eight countries, a total of 10,216 respondents were polled on a comprehensive, standardized questionnaire of 172 questions. A new section, Section G, titled ‘Internet and Social Media’, was introduced in this latest wave. Three questions in this section are the most important for our analysis:

Q50: Do you currently use any of the following social media networks? (Provide the three most popular examples in a given country context.) Answer: Yes/No

Q51. How often do you use the internet including social media networks to find information about politics and government? (Provide the three most popular examples in a given country context.) Answer: Everyday/Several times a week/Once or twice a week/A few times a month/A few times a year/Practically never

Q52: How often do you use the internet including social media networks to express your opinion about politics and the government? Answer: Everyday/Several times a week/Once or twice a week/A few times a month/A few times a year/Practically never

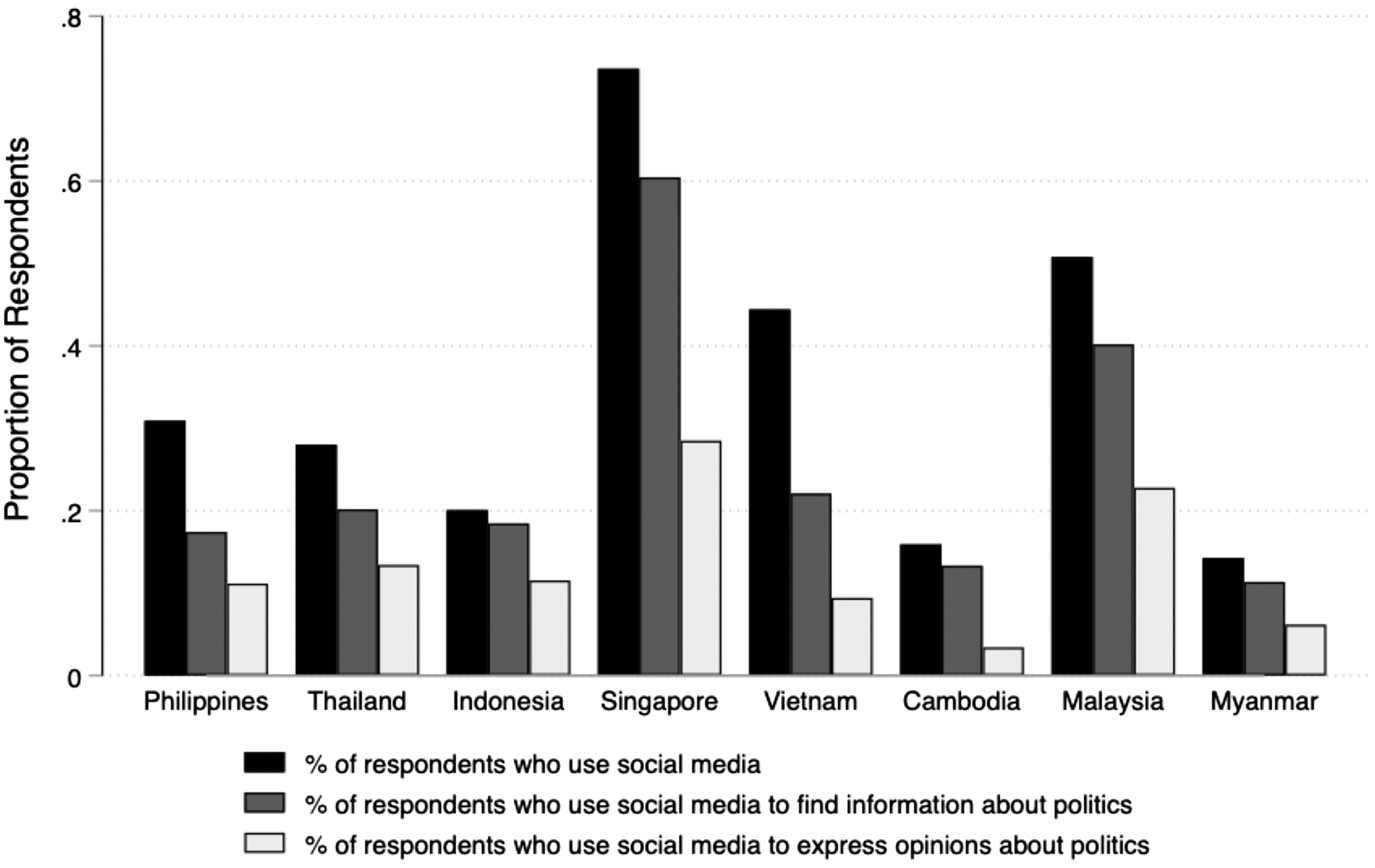

For ease of interpretation, I recoded the answers to the three questions into dichotomous variables. Respondents who answered ‘Yes’ to Q50 were coded as 1 with all other responses coded as 0. Respondents who answered ‘Everyday’, ‘Several times a week’, ‘Once or twice a week’, ‘A few times a month’, ‘A few times a year’ for both Q51 and Q52 were coded as 1, with all other responses as 0. The responses to Q52 will be the main dependent variable. Figure 2 shows the answers to the three questions across the eight Southeast Asian countries.

Figure 2. Social Media Use Across Eight Southeast Asian Countries

At least two findings are immediately relevant. First, the degree of social media use and proportion of respondents who are politically engaged to find information online appears loosely correlated with the level of economic development. Singapore and Malaysia, the two most economically developed countries in the region, have the highest proportions of politically engaged social media users in the region – between 40% and 60%. Cambodia and Myanmar, the two poorest countries in the sample, have the lowest proportions of their populations, about 10%, using social media to find political information. Respondents in the Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam were more moderate with about 15–22% of them politically engaged online.

Second, while a high proportion of social media users used social media to find information about politics, which I define to be the sub-population of ‘politically engaged social media users’, there was a substantial variation in how many of them used the same medium to express their opinion about politics. In the Philippines, Thailand and Indonesia, close to two-thirds of politically engaged social media users also used the same medium to express their political views. In Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia and Myanmar about half of the politically engaged social media users did so. In Cambodia, only a quarter of politically engaged social media users expressed their political views.

Unfortunately, we cannot use variation in the proportion of politically engaged social media users who express their political opinions online to make inferences about the degree of self-censorship in each country. After all, the likelihood of online political expression in each country may be a function of a range of observed and unobserved variables, including self-censorship. What we can do, however, is to infer whether self-censorship occurs by assessing if the likelihood of online political expression varies with income and across countries as hypothesized.

Independent variable

The independent variable of interest is income. The Asian Barometer asks respondents to indicate their household income in the appropriate quintile of their respective countries. I code the level of a respondent's income as 1 if the household income is reported to be in the lowest quintile and 5 if it is in the highest quintile.

Controls

I include two types of controls in my regression analysis – the socio-demographics of respondents and their general political attitudes. In the former category, I controlled for age, gender, whether the respondent resided in a rural or urban area, the education level of the respondent and whether the respondent was employed. It is important to control for these available socio-demographic variables because they may be correlated with the likelihood of online political expression alongside income (Mellon and Prosser Reference Mellon and Prosser2017; Sinpeng Reference Sinpeng2017).

For the latter category, I do so to account for the fact that political attitudes may not be evenly or randomly distributed across the population. For example, wealthier politically engaged social media users who have fewer economic grievances, have less dissatisfaction with a regime, or who may have voted for the winning party, may be less likely to express their political opinions online (Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Nadeau et al. Reference Nadeau, Lewis-Beck and Bélanger2013). I thus control for four types of general political attitudes – whether they believe that there is freedom of expression, the economic situation that they are currently in, their general dissatisfaction with the government, and whether they voted for the winning party in the previous general election. Respondents were coded 1 if they agreed that ‘People are free to speak what they think without fear’ and 0 otherwise; coded 1 if they thought that the economic situation of their family at present was ‘Bad’ or ‘Very bad’ and 0 otherwise; coded 1 if they were dissatisfied with the current government and 0 otherwise; and coded 1 if they voted for the winning camp in the previous general election and 0 otherwise. Table 1 shows summary statistics of the variables.

Table 1. Summary Statistics of Variables

Results

As a first test of whether the respondents who express their political opinions on social media are actually from the subset of ‘politically engaged social media users’ – that is, those who use the internet and social media to find information about politics, a simple cross-tabulation confirmed the intuition. The cross-tabulation revealed that fewer than 1% of respondents who are not ‘politically engaged social media users’ use social media to express their political views. This is 72 out of 7,757 respondents. Of the 2,459 ‘politically engaged social media users’, almost half express their political opinions online. In the analysis, therefore, I focus my attention on these 2,459 politically engaged social media users.

For ease of interpretation of the results, I ran an ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression estimating the likelihood of a respondent using the internet and social media to express their opinion about government and politics based on the reported household income level of the respondent, alongside other control variables. Table 2 shows the results of four OLS models with robust standard errors.

Table 2. OLS Regression Results

Notes: DV = Use internet and social media to express their opinion about politics and government (0–1). Standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

The results reveal that among politically engaged social media users, higher income levels are indeed inversely correlated with the propensity to use social media to express political opinions. For every quintile increase in reported household income, a politically engaged social media user is estimated to be about 1.7% less likely to express his or her political opinion online. These results are robust to the range of control variables included in models 2, 3 and 4. Two robustness checks also revealed no substantive changes to the results. Logistic regression used to account for the dichotomous nature of the dependent variable confirmed that the inverse correlation was statistically significant for all four models specified. When the dependent variable was recoded to an interval variable with ‘Everyday’ coded as 5 and ‘A few times a year’ coded as 1, the same inverse relationship was found. Substantively, Figure 3 shows the probability of expressing one's political views decreasing from about 50.5% to about 44.5% from the lowest to highest household income quintiles, based on Model 4.

Figure 3. Linear Prediction of the Likelihood of Expressing Political Opinions Online

To test if online self-censorship varies across countries where there are different severities of state-initiated criminalization and prosecution of online political expression, I ran the same OLS regression in Model 4, this time only for respondents within each individual country. The results revealing the coefficient estimates for household income level in Model 4 for each country are shown in Figure 4. The results demonstrate that the inverse relationship between income and the likelihood of online political expression among politically engaged social media users holds as expected in Thailand and Myanmar, two of the three countries with the worst record of state criminalization and prosecution of online speech for which we have data. In Thailand, every increase in quintile in reported household income means an estimated 6.6% reduction in the likelihood of expressing one's political opinions online. For Myanmar, it is almost a 9% decrease in the likelihood of online political expression for each increase in reported household income quintile.

Figure 4. OLS Regression Coefficients for Household Income Level Across Southeast Asia

For the five other countries – Cambodia, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines – the inverse relationship is non-existent, as hypothesized. In these five countries, online repression, to the extent that it exists, is not correlated with lower levels of online political expression by higher-income politically engaged social media users. Evidently, the low probability of getting caught by state authorities means that there is no difference in the likelihood of online political expression among politically engaged social media users with different incomes.

The key exception in Figure 4 is Vietnam. Despite Vietnam's severe online repression as documented by Freedom House, there is no statistically significant difference in online political expression among high- versus low-income politically engaged social media users, contrary to the expected utility model's theoretical expectations. What reasons can account for this anomaly? Considering the fact that Vietnam is the only Communist single-party regime among the eight Southeast Asian countries analysed in this article, a political economy explanation might better account for Vietnam's exceptionalism. The Communist Party of Vietnam's domineering control over all aspects of society and economy suggests that the vast majority of Vietnamese citizens are very wary of expressing their political opinions, regardless of their income, or their support or opposition to the regime. Any form of political speech regarding any topic, offline or online, could potentially be interpreted or misinterpreted as a form of political activity seeking to undermine the regime (Duong Reference Duong2017). Because citizens are so dependent on the state for their livelihoods, almost no one dares to challenge the regime for fear of perpetual social and economic exclusion. In short, there is no way back if the state decides to target them. Corroborating this widespread fear of political expression in Vietnam, Amnesty International found that state-initiated online repression was so severe in the country that ‘self-censorship is a common practice amongst the population as a whole’ (Amnesty International 2006: 11).

Conclusion

Both democracies and autocracies around the world are increasingly criminalizing and prosecuting critical online political expression. New laws are being written to equip governments with broad powers to legally harass, intimidate, arrest, investigate, charge and incarcerate online political activists who criticize them. At times, as in Vietnam, Thailand and Myanmar, the criminalization and prosecution of online activists has been frequent and widespread, spreading fear in politically engaged social media users about the risks involved in expressing their political opinions online. At other times, like in Cambodia, Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia, the prosecution of online activists has been more targeted, with governments selectively prosecuting prominent activists who are politically salient or who have amassed a significant online following. This article has advanced a novel, simple expected utility model of self-censorship, suggesting that self-censorship more likely occurs among high-income politically engaged social media users, especially in countries where there is severe criminalization of online speech and prosecution of online activists. In countries where online repression is moderate or low, politically engaged social media users are more likely to believe that they can ‘get away’ with critical online speech, and are hence less likely to self-censor. Researchers relying on social media data to make descriptive or causal inferences should adjust their research designs and analyses to account for this particular bias generated by self-censorship.

Certainly, the present study is limited both theoretically and empirically. The theoretical model assumes that an individual makes a decision to self-censor independent of the broader political economy context of the regime. As the Vietnamese case demonstrates, extensive state control of everyday life can induce self-censorship among the entire populace, significantly diminishing intra-country variation for self-censorship. In contrast, the dramatic fall of Malaysia's autocratic regime in the May 2018 general elections also suggests that citizens have the capacity and potential to resist self-censorship amid the uncertainty of repression (Tapsell Reference Tapsell2019). Social media on smartphones can both spread fear and be a ‘weapon of the weak’. Further illuminating the delicate circumstances under which autocrats repress and when the public resists in the new online arena will require new theoretical extensions beyond this initial expected utility model.

Empirically, the cross-national survey data examined in this analysis are also far from perfect. They have provided a snapshot of the general cross-national correlation between online repression and online political expression when the surveys were conducted between 2014 and early 2016, and do not account for worsening trends of online repression in the region. Furthermore, the frequency of online political expression is used as a proxy for inferring self-censorship and is not a direct measure of self-censorship itself. Future research should at least attempt to develop alternative, more accurate measures of self-censorship, and also endeavour to track if and how the public's views of online repression evolve over time. Recent advances in survey analyses, such as survey experiments, list experiments and conjoint experiments, can potentially be deployed to estimate more precisely the causal relationship between perceptions of state-initiated online repression and propensity for online political expression.

Nevertheless, despite these limitations, the most important takeaways of this study have been clarifying how exactly state-initiated legally justified online repression works, and in developing a novel theory about which individuals are more likely to self-censor. Executive office politicians in both contemporary autocracies and eroding democracies are using very similar methods to silence their most vocal critics on what was previously thought to be the most liberal and open platform for free speech – the internet and social media. Freedoms of speech and expression are stifled when those freedoms are not exercised because of self-censorship. In this way, autocratic leaders boost their perceived popularities, creating a snowball effect of further legitimizing and strengthening executive aggrandizement. This is how online repression and self-censorship entrenches autocrats and encourages democratic backsliding.

Author ORCID

Elvin Ong, 0000-0002-8618-5629

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Allen Hicken, Kai Ostwald and the participants at the 2018 American Political Science Association annual conference for their generous comments and feedback. Nhu Truong and Aim Sinpeng were instrumental in organizing the panel sponsored by the APSA Southeast Asian Politics Related Group (SEAPRG). The research was supported by National University of Singapore's Overseas Postdoctoral Fellowship under the Ministry of Education's Singapore Teaching and Academic Research Talent (START) scheme.