Introduction

During South Africa’s colonization of Namibia (1915–1990), ideologies of white supremacy reached beyond social and civil society to the wildlife and the landscape.Footnote 1 Since independence in 1990, Namibia has been moving toward a more just and equitable society. But decolonization has not emphasized the more-than-human effects of South African imperial rule (Whatmore Reference Whatmore2002). Throughout the colonial era, human-lion (Panthera leo) interactions were differently experienced by white settlers and Africans as expressions of racialized social and environmental politics, with lasting effects. This case study examines the history of human-lion interactions in northwest Namibia, with an emphasis on the colonial era. It reveals a history in which Europeans and the state reproduced white supremacy through human-livestock-lion interactions. This deepens the environmental historiography of Namibia by showing how white settler-farmers and African pastoralists experienced colonial power differently through environmental vectors. This is part of an emerging historiography of the global South and the subaltern, in which nonwestern perspectives are given equal voice with imperialist and politically dominant perspectives. The more-than-human approach shows that racialized imperial rule had clear environmental effects that are still evident within these postcolonial landscapes; this is part of an emerging approach to environmental history that can also make substantive contributions to African studies scholarship (O’Gorman & Gaynor Reference O’Gorman and Gaynor2020). For wildlife conservationists, this history reveals the durability of human-lion conflict and the lasting effect of racialized colonial policies, suggesting that human-lion conflict interventions must address both social and environmental management challenges. Here, reproduction refers to the social processes through which cultural ideas of privilege and dominance are entrenched among groups and across generations (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Brown1996).

Human-lion interactions during the South African colonial period were coopted to serve the racialized goals of the South African empire. In their Namibian-centered overview of South African colonialism, Dag Henrichsen et al. describe empire as “a systematic order, an arrangement of the world into categories…express[ing] itself through disciplines and institutions, the division of nature and culture, and in the enduring colonial legacies of racialised collecting” (Reference Henrichsen2015:433). I have found these threads in the history of human-lion interactions in colonial northwest Namibia, where racial categories were manifest in government policy concerning human-lion interactions, while enduring colonial legacies still influence the geography of lion survival, as well as the ongoing challenge of human-lion conflict facing African pastoralists.

Lions in northwest Namibia are the most geographically isolated free-ranging population of lions in southern Africa; they exhibit pride structure and behavioral and social adaptations to their arid environments.Footnote 2 Lions have historically inhabited central and northern Namibia (Shortridge Reference Shortridge1934). Today they persist in the wild in the northwest (Etosha and Kunene) and north-eastern parts of the country. I focus on the northwest population, due to high government interest in resolving human-lion conflicts there (NMET 2017). I begin by contrasting the history of human-lion interactions in northwest Namibia with the popular western conceptions of lions, which are primarily derived from human-lion interactions in East Africa. The role of livestock is central to this history. The arrival of livestock in northwest Namibia transformed human-lion interactions into spaces of potential and actual conflict. In particular, asymmetric colonial efforts to protect white-owned livestock—cattle (Bos taurus), goats (Capra aegagrus), and sheep (Ovis aries)—from antagonistic interactions with lions were integral to perpetuating European dominance and racialized government policies. The different experiences of whites versus Africans echoes historian Emmanuel Kreike’s contention that environmental changes in Namibia did not follow a “unilinear Nature-to-Culture” narrative (Reference Kreike2009:81). The important role of livestock in generating human-lion conflict is underscored by the rise of wildlife conservation in Etosha, a space formerly occupied by humans and livestock, but which became a space set aside for wildlife where human-lion interactions were no longer antagonistic. In contrast, the neighboring “ethnic homeland” of Kaokoveld remained a space inhabited by humans, livestock, and lions, with each suffering as a result. Following independence, Kaokoveld (renamed Kunene Region) became the only space where humans, livestock, and lions all continue to exist. In Kunene, pastoralists are now being pressured to conserve lions, though they still suffer from human-lion conflict and limited government support.

This “animal-sensitive history” (Swart Reference Swart2019) draws upon scholarship from human-animal studies, a diverse field accounting for animal agency and providing alternate theorizations to the hierarchical ordering of human over animal (Benson Reference Benson2011; Pearson Reference Pearson2013). By focusing on human-(livestock-)lion interactions, I show that predators and livestock have been vectors of reproducing inequality (Oommen Reference Oommen2019; Rangarajan Reference Rangarajan2013). This study also draws upon the environmental historiography of northwest Namibia, particularly the work of historian and anthropologist Michael Bollig (Reference Bollig, Hayes, Silvester, Wallace and Hartmann1998, Reference Bollig2020) and historians Lorena Rizzo (Reference Rizzo2012) and Giorgio Miescher (Reference Miescher2012), whose works are highly recommended for those seeking to learn more about the region. While these and other historiographies and ethnographies have shown how African pastoralists and their livestock negotiated the practices and policies of the colonial period, they have not shown how wild species either exacerbated or undermined colonial efforts to rule northwest Namibia. As I have shown elsewhere, humans, livestock, and wildlife all resisted colonial rule in different ways (Heydinger Reference Heydinger2021). I add to this perspective by showing that wild species, in this case lions, were relationally dynamic in their own right, and that they did not affect colonial subjects equally. This further reveals the extent of the social and economic injustices of colonial rule. Many of the issues raised remain pertinent to decolonization challenges and questions of socioeconomic and environmental justice.

The available material on human-lion interactions in northwest Namibia is limited, and it is diverse in format. Precolonial material primarily comes from nineteenth-century European “explorers” and archaeological evidence. Colonial-era records primarily come from Namibia’s National Archives and published sources. Environmental historian Lance van Sittert notes that the reliance on elite archives within the historiography of wild animals in southern Africa perpetuates the marginalization of subaltern perspectives (Reference van Sittert2005). Bringing forth oral accounts of African pastoralists contravenes the reproduction of historical inequalities by rebalancing historical accounts away from the previously dominant voices too frequently reproduced in archives and published accounts. These accounts were collected by me between July 2017 and May 2019 as part of a broader oral history and social project examining human-lion conflict on communal land in northwest Namibia, in which eighty-five livestock-owning household heads participated in semi-structured surveys and seventeen community members participated in unstructured oral histories. All information was audio recorded, and relevant passages were transcribed. To protect respondent anonymity, responses are identified by an assigned number along with the location of the interview. Additional oral accounts are drawn from published anthropological works. Grey literature and limited-circulation documents detail changing lion conservation efforts. My own perspective is informed by more than four years of lion conservation and community extension work in northwest Namibia. The history related here provides critical context and informs ongoing locally-centered conservation interventions (Lion Rangers 2021).

Pan-African Human-Lion Narratives

Environmental historians have examined the role of elite European hunters in forging western perspectives of typical interactions between humans and African wildlife (Carruthers Reference Carruthers2005; MacKenzie Reference MacKenzie1988). Within the English-speaking world, early popular accounts emphasized the experiences of British and American hunters in present-day Kenya and Tanzania. John Patterson’s Man-Eaters of Tsavo (Reference Patterson1907), reports of U.S. President Roosevelt’s safaris (Neumann Reference Neumann2013), and works by Ernest Hemingway (Reference Hemingway1961), all feature violent human-lion interactions and emphasize the prospect of human death from lions. Though specific numbers may be exaggerated, they communicate a tone of fear and likely understate the death toll; across Africa, untold numbers of “natives” were killed by lions during the colonial era, but most of these deaths went unrecorded (Kruuk Reference Kruuk2002:61).

Early scientific perspectives of lions also primarily came from Kenya and Tanzania. Biologist George Schaller’s The Serengeti Lion (Reference Schaller1972) was one of the first high-profile scientific works on the species; it became the standard understanding of lion behavior, ecology, and sociality for a generation. In 1978, Craig Packer took over the Serengeti Lion Project, which he directed for more than thirty years, authoring dozens of scientific and popular articles and two books on lions in the area (Packer Reference Packer1994, Reference Packer2015). As a result, lions from these areas are among the most studied, publicized, and consistently conserved.

Until the twentieth century, lions ranged across African habitats (Haas et al. Reference Haas, Hayssen and Krausman2005). During the twenty-first century, lion range has been reduced to approximately 10 percent of their historically recorded range and has decreased by 43 percent since assessments were compiled in the late 1990s. There are currently 20,000 to 30,000 free-ranging lions in Africa. As many as half of these reside in East Africa, primarily within the Serengeti or similar grassland ecosystems (IUCN 2018). In contrast, wars of independence, civil wars, and other forms of societal turmoil and government instability in formerly lion-rich places such as West Africa, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique, and the lingering effects of apartheid in Namibia often kept information about lions in these places from reaching international audiences. Many of these countries contain lions inhabiting settings radically different from the Serengeti, including the forests of West Africa and Mozambique and the deserts of Botswana and northwest Namibia. Thus, the popularly-received picture of lions, of human-lion interactions, and lion conservation efforts provide only a small sample of the diverse localities in which humans and lions have historically interacted and continue to interact today.

The Shared Landscape

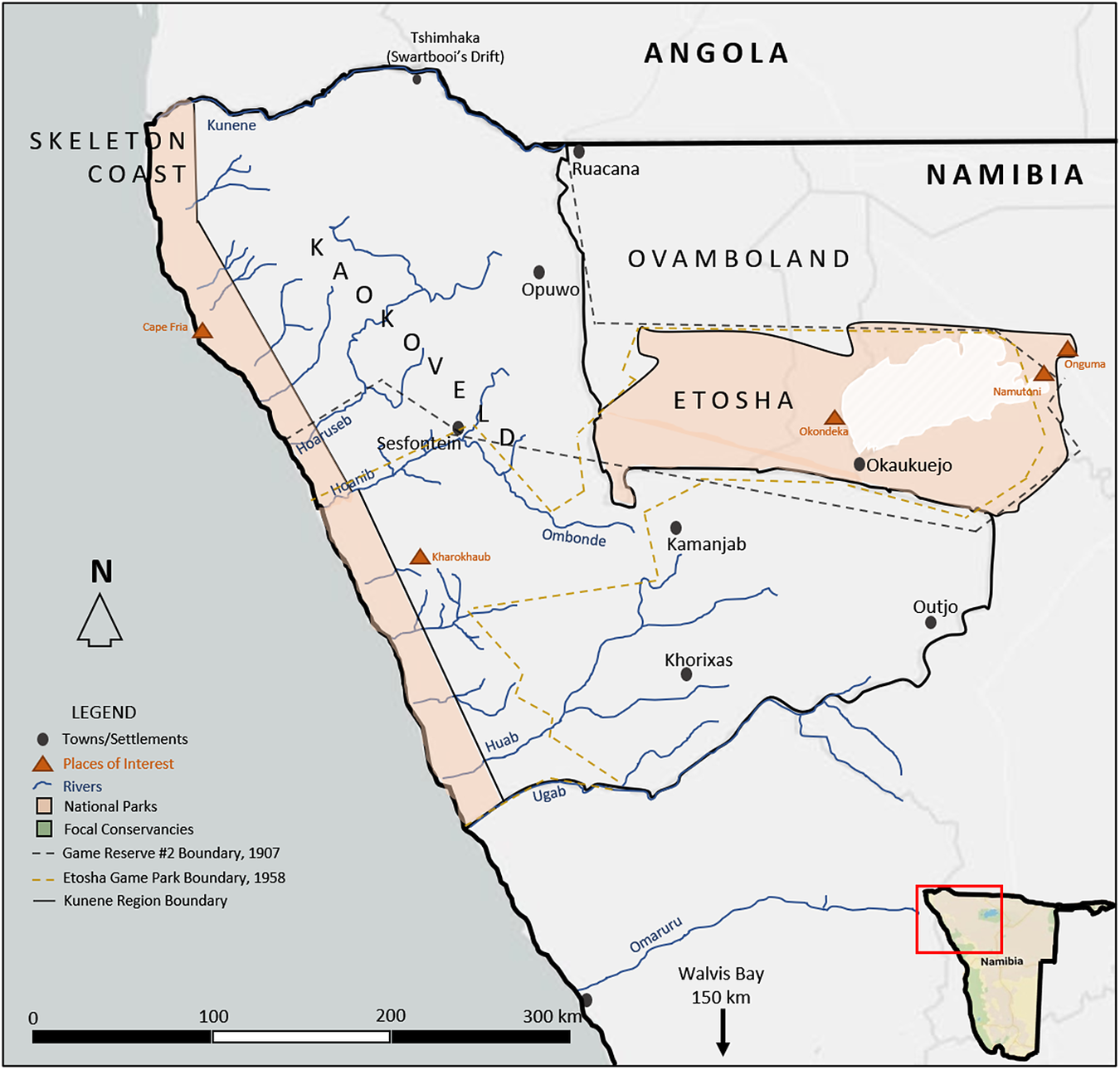

Northwest Namibia is bounded by the Ugab river in the south, the Kunene in the north, the Skeleton Coast in the west, and Ovamboland in the east (see Map 1). Previously referred to as Kaokoveld, and as Kaokoland and Damaraland during apartheid, following independence the area was renamed the Kunene Region. The region’s heterogeneous environments are dominated by mountains, gravel plains, and sandy dunes bisected by ephemeral riverbeds in the west and mopane savannah further east around present-day Etosha National Park. Rainfall is low (50 to 300 millilitres per year) and erratic, though it generally increases as one moves east away from the ocean. The region supports a variety of wild species adapted to the boom-and-bust nature of the rainfall and available grazing, including springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis), oryx (Oryx gazella), mountain zebra (Equus zebra) and plains zebra (E. quagga), kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros), and giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis). During the wet season (January to May), rains may come in brief, localized downpours. These are followed by migrating wildlife and livestock driven by semi-nomadic herders. During the dry season (June to December), both wildlife and livestock often congregate in ephemeral riverbeds where grass remains (Mendelsohn et al. Reference Mendelsohn2003).

Map 1. Map of northwest Namibia (created by author).

Genetic evidence indicates that lions have inhabited northwest Namibia for tens of thousands of years (Antunes et al. Reference Antunes2008). Prior to the arrival of intensive pastoralism, the region was home for thousands of years to small bands of highly mobile Khoe-Sān, who were primarily hunter-gatherers. Anthropological work by Ute Dieckmann with the Hai||om, a Khoe-Sān group residing near Etosha, suggests that lions and hunter-gatherers can maintain somewhat collegial relationships. Dieckmann recorded memories of lions and humans recognizing each other’s dominance based upon different times of day or night. One man remembered that when he was young,

“We even shared meat with the lions. In the daytime we took their meat and at night we served them our wounded game!” Another elaborates that “the lions were regarded as ‘colleagues,’ if not friends.” And if they tried to attack them? Kadison explains that there was a saying shouted at approaching lions: “||Gaisi ai!nakarasa!”, meaning “You ugly face, go away!”

(van Schalkwyk & Berry Reference van Schalkwyk and Berry2007:66, 73)During their Serengeti research, Schaller and anthropologist Gordon Lowther found lions to be “little inclined to attack during the day.” They posited groups of hominid hunter-gatherers could have cautiously moved through the daytime landscape. They put this proposition to the test by stalking game and scavenging carcasses on foot. Analogizing their experiences to early hominids, Schaller and Lowther concluded,

If they kept in open country, away from thickets in which lions often rest, and traveled in groups, a practice which would increase their rank in the inter-specific predator hierarchy, hominids would probably have been molested only rarely. Even when encountering a predator at close quarters, they could have put it to flight by using such typical primate intimidation displays as vocalizing and throwing and shaking branches, a technique effective against today’s predators.

(Reference Schaller and Lowther1969:330)Biologist Hans Kruuk has challenged these assertions, noting, “present-day lions are conditioned to people being armed and dangerous” (Reference Kruuk2002:113). Kruuk also notes that human-lion antagonism may be driven by lion cultural transmission, suggesting, “one animal learning from another, plays a role in prey selection…Perhaps lions have now learned from their elders that people do not fit into their normal spectrum of prey species” (Reference Kruuk2002:62). Field work in northwest Namibia supports the perspective that human-lion interactions cannot be essentialized as antagonistic or violent. Lions typically avoid people traveling on foot during the daytime. In contrast, lions are much bolder at night, sometimes investigating groups of people, including approaching the open windows of an unfamiliar research vehicle and lingering nearby while their pride-mates are immobilized and collared (personal observation). Because human-lion interactions take a variety of forms, historians can examine the contingencies of different interactions.

Livestock and Lions

Livestock presence transforms human-lion interactions into almost universally antagonistic experiences for humans, livestock, and lions. This was recognized by one pastoralist in northwest Namibia, who put the matter succinctly: “If you are only a person you can live with lions. But if you are having livestock, then it is not good.”Footnote 3

The arrival of livestock in northwest Namibia, beginning in the last few centuries BCE, would have had significant livelihood effects for the region’s residents and the prospects of the region’s lions (Sadr Reference Sadr2015).Footnote 4 Domesticated sheep were present among the Khoe-Sān in the northern Namib desert two thousand years ago; cattle arrived in large numbers during the last one thousand years (Kinahan Reference Kinahan2016, Reference Kinahan2019). Intensive pastoralism in northwest Namibia increased in the sixteenth century, coinciding with the arrival of the ovaHerero people (Borg & Jacobsohn Reference Borg and Jacobsohn2013).Footnote 5 With the ovaHerero came large numbers of cattle.

The introduction of large numbers of domestic stock, which were not as adapted to resisting predators as wild prey were, would have been a boon for the lions. Historian William Beinart has shown that predators at the Cape quickly adapted to the novel opportunities presented by the slower, less dangerous animals that crowded out wild prey (Reference Beinart1998). As Mahesh Rangarajan has noted for India’s Gir Forest, “Herding of sheep, cattle, and goats offered large cats and canids easy meat on the hoof…That lions should hunt cattle was only logical” (Reference Rangarajan2013:113). Goats and sheep—local breeds weighing an average 29 to 32 kg and 50 to 90 kg respectively—could feed a small group of lions for a day or two, while large-bodied cattle (300 to 600 kg) could feed them for a number of days (Schaller Reference Schaller1972:276).

Historian Jon Coleman has found that the arrival of livestock in colonial North America created relationships that predators were ill equipped to navigate. “Wild” animals generally evince great fear of humans. However, a similar fear of livestock has not been developed by predators. Coleman shows that livestock survival, and by extension the social and economic reproduction of human livelihoods, lay at the heart of human-wolf conflict. “Wolves,” Coleman writes, “had enough sensibility to retreat from people, but…[w]hen they sank their teeth into cows, pigs, and sheep, wolves committed sins unimaginable to them.” He continues: “Wolves and people were not natural enemies…humans’ relationship with other animals established their rivalry with wolves” (Reference Coleman2004:36, 49). Similarly, when lions attack livestock, they constrain human livelihoods, engendering human antagonism. However, as we will see, when governments intervene, livestock owners’ relationships with predators can take different forms.

The economic value of a growing livestock culture was reinforced by European trading ships moving along the Skeleton Coast throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. While the ovaHerero mostly kept their stock hidden in the rugged Kaokoveld, Khoe-Sān pastoralists sought to benefit from this new market by maintaining stock camps near Walvis Bay. However, without sufficient water or suitable forage at the coast, these pastoralists and their stock trekked further inland (Kinahan Reference Kinahan2014). Such drives, with livestock and people sleeping in the open, presented an opportunity for lions and other predators (Wallace & Kinahan Reference Wallace and Kinahan2011:35–36). As lions turned toward more densely populated herds of docile livestock, I suggest that their hunting success improved and lion numbers increased. The pastoralists’ bow-and-arrows, spears, or rudimentary firearms and/or botanical poisons would not have been much of a deterrent. Whereas previously, the threat of lions may have been considered too great for pastoralists to make such dangerous treks, access to trade goods would have ameliorated some of the material effects of livestock loss. This period drew humans, livestock, and lions into a feedback loop interweaving colonial markets, livestock death, and human-lion conflict.

European Strength and the Killing of “Man-Eaters”

When European “explorers” entered northwest Namibia during the nineteenth century, human-livestock-lion interactions were a familiar challenge to local pastoralists. Speaking of the end of the 1800s, one Himba recounted,

In those days the cattle were properly herded because of hyenas and lions…During the night the people would not go out; sometimes the lions were even entering the homesteads to kill the cattle.

(Bollig Reference Bollig2020:36)Western accounts of lions in northwest Namibia began with Francis Galton and C. J. Andersson in 1853 and were typically antagonistic. They recorded lions being attracted by their party’s retinue of livestock (Andersson Reference Andersson1856:53). The conflict that occurred when lions attacked livestock, or the humans tending them, created a space in which Europeans—well-equipped with firearms—could exercise a dominance regarding human-lion interactions that was not widely available to locals. In a series of dramatic stories, Andersson depicted locals as terrified, rendered helpless, and even killed by lions. A typical incident of panic included,

the screechings of the terrified women and children…the hallooings of the men, the rush of the cattle and the sheep, firebrands whizzing through the air, the discharge of fire-arms, the growls of the lions, and other discordant noises, the scene was one which baffles description.

(Andersson Reference Andersson1861:140)Like other Europeans, Andersson and Galton reproduced accounts of “white male gigantism,” in which brave white men penetrate wild Africa to destroy fearsome man-eaters (Coleman Reference Coleman2011). Tales of (white) muscular colonialism, communicated back to the metropole, reproduced perspectives of European triumphing over African, and civilization over nature. Human-animal historian Simon Pooley has shown that European hunters considered lions and crocodiles to be Africa’s most fearsome animals (Reference Pooley2016). As historian Jane Carruthers notes, for Europeans, “hunting lions came to be regarded as the ultimate test of masculine bravery and strength” (Reference Carruthers2005:192). While this may be true, we can see through the history surrounding Andersson and Galton’s (Reference Galton1853) accounts that such experiences, though they may have sold books, largely represented a passing era.

Lion Eradication as White Domination

Profit and capitalist growth were the driving forces behind white colonialism in Namibia, but the natural world was not easily constrained by economic idealizations (Botha Reference Botha2000). By the twentieth century, European interactions with lions primarily took the form of settler-farmers eradicating lions and other predators for economic reasons. During the colonial era, South Africa and Namibia maintained Africa’s only large white settler underclass. White settler-farmers during the early twentieth century were primarily composed of landless white bywoners (sharecroppers) from South Africa, who were encouraged to settle in Namibia by generous government assistance programs (Lau & Reiner Reference Lau and Reiner1993:53). Though these landholders were well-to-do compared to African farmers, many required extensive government assistance to make ends meet (Botha Reference Botha2000). Environmental historians have examined the historical interactions between this relative underclass and predators, emphasizing jackals (Canis mesomelas), and finding that jackal killing was important for securing white livelihoods (Moore Reference Moore2017; Swanepoel Reference Swanepoel2016). Among settlers, the fearsome traits of lions were secondary to their economic effects; lions were primarily considered vermin needing to be destroyed in order to secure rangelands for livestock. Efforts to control valuable pastureland for white benefit resulted in widespread lion death on white farms (Heydinger Reference Heydinger2020a). Though the “sport” of lion killing never disappeared entirely among Europeans, as the number of white settlers, primarily from Germany and South Africa, rose dramatically in the early twentieth century, the driver of human-lion conflict was the threat that lions posed to livestock (Botha Reference Botha2000).

Colonial farmers demanded government assistance in eradicating lions and other “vermin” (ongedierte) (NAN SWAA 1349 1921; NAN SWAA 2328 1918, 1923). As van Sittert has shown for the Cape Colony/Province, marginally productive rangelands forced farmers to drive livestock far afield, sometimes for days at a time, where their exposure to predators greatly increased. This meant stock often slept in the open, as opposed to trekking back and forth each day to enclosures where they were more likely to suffer from diseases of overcrowding (van Sittert Reference van Sittert1998). Though fences were useful against small and medium-sized predators (Moore Reference Moore2017), expensive lion-proof fencing was beyond the means of most farmers, many of whom relied upon government cash grants and infrastructure loans (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Werner and Vale1990:20–24; GSWA 1927). The recurrence of human-lion conflict created a space in which the colonial government’s prioritization of white settler livelihoods was evident. Elsewhere I have shown that the destruction of predators by settlers received extensive government support, such as tax relief and ammunition and industrial poisons at cost price (Heydinger Reference Heydinger2020a). The government also supported the creation of “vermin clubs”—whites-only hunting groups empowered to eradicate predators on private land. By contrast, non-whites were barred from receiving ammunition and poisons and from joining vermin clubs, revealing yet another form of racialized colonial domination, this time by constraining Africans’ interactions with predators. Similar to the destruction of wildlife by whites in eastern South Africa, the slaughter of predators served white Namibians’ “physical and economic survival” (Carruthers Reference Carruthers2005:187). As noted by Coleman regarding bear hunting in the southeastern United States, the necessity of such eradication indicated the socially and economically marginal positions occupied by the settlers (Reference Coleman2011).

When it came to lion killing, economic marginality did not preclude, but rather supported the reproduction of a mythos of white dominance. As lions were widely recognized symbols of wild Africa, their destruction reproduced white strength in written and visual discourse. In Lords of the Last Frontier, Lawrence Green, a popular South African author, portrayed typically rugged, white masculine lion hunters in northwest Namibia as the vanguard of European civilization. Green praised one Outjo-area settler as a “great lion hunter.” Another was reputed to have killed at least fifty lions, only to die at the hands of a lion he had wounded (Reference Green1952:126, 136). Though lion hunting evoked danger, more often than not it was the lions who died, surrendering their heads and skins for prominent display (NAN SWAA 2329 1952). More mundanely, German soldiers at remote Fort Namutoni fought boredom by shooting lions from observation towers during the first decade of the 1900s (van Schalkwyk & Berry Reference van Schalkwyk and Berry2007:46). Historian Patricia Hayes has analyzed photographic portrayals of white dominance on the Namibian frontier. For example, photographs of Ovamboland and Kaokoveld Native Commissioner Carl “Cocky” Hahn centered Hahn as the dominant force in scenes of lion death (Hayes Reference Hayes, Hartmann, Silvester and Hayes1998, Reference Hayes, Miescher and Henrichsen2000) (See Figure 1). When Africans are present in these images, they stand adjacent to Hahn’s position of dominance—present, but peripheral.

Figure 1. Carl “Cocky” Hahn with unnamed Africans and dead lions, 1930s.

Source: Namibia National Archives.

Game Reserve No. 2/Etosha

State support of the white economy, reinforced by European masculinity emphasizing wildlife destruction, led to the dramatic decline of lions in white-controlled areas. By 1912, lions around Etosha had become so rare that when Lieutenant Adolf Fisher heard them roaring near Namutoni, it was the first evidence of lions there in years (Berry Reference Berry1997:5). In later years, Rudolph Böhme, a long-time resident of Onguma farm bordering eastern Etosha, noted there were no lions in the area when he was young, until 1917 (NAN SWAA 2331 1952).

The slaughter coincided with increasing government control over the northwest. In 1907, efforts to protect the white economy led to policies demarcating specific areas for settlers, Africans, and wildlife (Miescher Reference Miescher2012:43–68). The largest area set aside was “Wildschutzgebiet Nr. 2.” Originally encompassing Kaokoveld as well as Etosha, Game Reserve No. 2 was approximately 80,000 square kilometers, which made it at that time the world’s largest wildlife reserve (Berry Reference Berry1997). The reserve’s creation was part of a trend in southern Africa for colonial governments to designate African-controlled land for the protection of charismatic wildlife, which was considered an economic and social resource (Miescher Reference Miescher2012:52–53). This practice also limited human mobility and increased state surveillance (Carruthers Reference Carruthers, Griffiths and Robin1997). The southern border of the reserve delineated the extent of German, and later South African, colonial possession, spaces to the north being considered “too rough and mountainous for European occupation” (NAN SWAA 1168 1926).

At the outset, Game Reserve No. 2 was no haven for lions. White ownership of farms within the reserve only ended in 1935 (Berry Reference Berry1997). In 1922, the local magistrate supported the request of two whites to shoot lions at Okaukuejo (NAN SWAA 2328 1922). In 1924, G. C. Shortridge noted that lions inhabited “the Kaokoveld and Etosha Pan areas, in the second of which districts, owing to trapping and poisoning in the Game Reserve, they have been very much thinned out” (NAN SWAA 1331 1924). In a 1926 survey, Etosha and Ovamboland, a combined area of at least 48,000 square kilometers, were estimated to contain 200 lions total (GRSA 1964:27; Berry Reference Berry1997). In 1934, Shortridge showed lions to be present around Etosha and increasingly plentiful further north, though he thought they were uncommon in Kaokoveld. This perspective was not universal. Böhme believed that though lions were largely absent from his farm, they persisted in Kaokoveld, where whites infrequently went (NAN SWAA 2329 1952; NAN SWAA 2331 1952).

As Etosha’s profile as a wildlife reserve was growing, the colonial government’s stance on killing lions there changed. During the early 1930s, vermin clubs killed lions and other predators along the reserve’s southern and eastern borders by the hundreds and thousands annually (Heydinger Reference Heydinger2020a). However, in 1936 the vermin law was repealed, leaving the status of lions within the reserve unclear. Although they were no longer classified as vermin, they were not explicitly protected. In 1938, Native Commissioner Hahn, also serving as the Etosha warden, convinced the Secretary for South West Africa to enforce an existing prohibition against shooting within the reserve, though lions could still be killed “in defence of human life or to prevent the infliction of personal injury” (NAN SWAA 2328 1938a, 1938b). During the 1940s, Etosha lions were still considered a menace by neighboring white farmers, leading to an estimated eighty lions per year being killed and prompting one farmer to request permission to pursue lions into the reserve (de la Bat Reference de la Bat1982:16; NAN SWAA 2329 1952). The request was rejected. Peter Stark, who later served as an Etosha ranger, claimed to have killed seventy-five lions while employed on a farm bordering Etosha during the 1940s and 50s. Stark later wrote, “In those days if you asked Nature Conservation for help, your pleas fell on deaf ears” (Reference Stark2011:38). This put Etosha conservationists at odds with both European and Africans on surrounding lands.

As they disappeared from white farmlands, lions still caused fear and destruction among African pastoral communities. This disparity had lasting effects on the geographic distribution of lions and other predators, leading to a spatially explicit divergence in human-lion interactions that continued throughout the South African period.

Lion Persistence in Kaokoveld

While the colonial government supported white farmers facing the challenges of human-lion conflict—in the form of financial support, as well as ammunition and poisons—Africans’ struggles went largely unaddressed and were even hampered by official practices. Kaokoveld residents requested access to firearms and industrial poisons but were denied. When South Africa took control of Namibia during World War I, at least 155 firearms were seized in Kaokoveld (Bollig Reference Bollig2020:110). The few communities that still had firearms often had only one weapon available for use. Ammunition was rarely issued, and then as few as five to ten rounds. Africans were also not trusted with the use of strychnine or other poisons (NAN NAO 031 1943; NAN SWAA 2328 1945). This forced Kaokoveld pastoralists to find their own solutions. Certain residents confronted lions armed only with spears. As one report stated,

This usually results in several of the hunters being mauled. Only a few days ago [a Himba] was treated for an arm wound caused by a lion, and he intimated that two of his less fortunate comrades were laid up with more serious wounds.

(NAN NAO 061 1946)Kaokoveld inhabitants pleaded for assistance. Addressing government officials, one headman summarized their struggles and the inadequate government response,

Here in the Kaokoveld we live only on our livestock…We thank you for the guns we have received. They are not enough. The Kaokoveld is very big. The cartridges are also too few. We have trouble with lions, hyaenas and wild dogs. Vermin has destroyed a lot of our stock.

(NAN NAO 061 1949)Official inaction led to numerous livestock deaths. In 1942, the Officer-in-Charge of Native Affairs for Kaokoveld reported, “It is not possible to ascertain how many animals were killed by lions and hyenas…the natives maintain that they have sustained very heavy losses” (NAN NAO 029 1942). Another official described lions and other predators as having been, “troublesome during the year…the natives frequently bring in reports of the losses sustained” (NAN NAO 029 1944). Complaints among Kaokoveld residents occurred so frequently that a category detailing human-predator problems, termed “Carnivora,” began appearing in government reports (NAN NAO 029 1942, 1944).

Nevertheless, officials remained skeptical. In 1946, the Officer-in-Charge of Native Affairs for Kaokoveld stated his position plainly,

Numerous reports were received of the losses sustained as a result of the onslaughts of carnivora, but I feel convinced that the natives are inclined to exaggerate their losses, and that a high percentage of these losses are due to the carelessness of their herd[er]s, also to the neglect of adequate kraaling at night.

(NAN NAO 061 1946)Denigrating African herding practices and questioning the veracity of the pastoralists’ claims formed part of what Bollig has called a “supremacist, imperious, and aggressive” discourse among colonial officials (Reference Bollig2020:81); it also remains a common reaction among Europeans in Namibia (personal observation). Yet, “adequate kraaling at night” was often not an option. In arid areas with limited grazing, bringing stock to and from enclosures each night strains the animals and degrades grasses near the homestead (van Sittert Reference van Sittert1998). When asked why she does not always kraal her stock, one Sesfontein pastoralist responded that in her experience, stock being kraaled each night will lose 25 to 30 percent of their body condition, due to overcrowding and tramping back and forth to available grazing. In contrast, if they are allowed to sleep where grazing is available, perhaps predators will kill some of them.Footnote 6

Attacks on humans also persisted. In the early 1940s, a headman from Sesfontein, a major settlement and gathering point, was killed by lions (Green Reference Green1952:42). In 2017, one elder man remembered his own fearful encounter: “When I was a young man, I was with a man who was attacked by a lion.”Footnote 7 Another shared this story:

One man was looking for honey…He went into the mountains and was camping there and the lions killed him there. The people around here were looking for him, looking for him…My father went into the mountains to get some honey also and saw the bones [of the man] lying there and brought the bones back so they could bury the bones. This is when I was a very young person—my father told me about this.Footnote 8

The disparate outcomes between white farmlands and Kaokoveld pastureland indicate the important role of government intervention in influencing the outcomes of human-lion conflict. Yet, the government’s dismissal of African pastoralists’ struggles also served state goals. Livestock deaths constrained livelihoods. Because native reserves were intended to serve as reservoirs of cheap labor for white-owned mines and farms, dead livestock helped maintain a prostrate African peasantry. Elsewhere I have shown how colonial era policies that were focused on livestock movements and predator eradication were interwoven with state economic concerns (Heydinger Reference Heydinger2020a, Reference Heydinger2020b). The success of Kaokoveld pastoralists in maintaining large herds frustrated government attempts to recruit workers from the region (van Wolputte Reference van Wolputte2004:157). The state’s use of veterinary and environmental means to keep Kaokoveld pastoralists impoverished during the colonial era have been examined by Bollig (Reference Bollig, Hayes, Silvester, Wallace and Hartmann1998), among others. Steven van Wolputte (Reference van Wolputte2004) has interpreted ovaHerero livestock ownership and mobility during this period as a form of political disobedience. Furthermore, livestock, particularly cattle, played—and still play—an important cultural role among the ovaHerero (Crandall Reference Crandall1998; Jacobsohn Reference Jacobsohn1998). More than simply being commodities which provide milk, meat, and cash, cattle embody nonmaterial values and historical continuities. When lions kill livestock, they can rupture these trans-generational cultural continuities. Because they also threaten human lives, lions are still seen as particularly dangerous and destructive (Heydinger et al. Reference Heydinger, Packer and Tsaneb2019).

The difficulties that Kaokoveld pastoralists faced from predators were generated by livestock ownership and the central role of livestock in maintaining their livelihoods. In this way, Kaokoveld pastoralists were similar to white farmers. The critical difference, one entrenching human-lion conflict as an ongoing challenge in Kaokoveld, can be seen in the unequal government policies that exacerbated the challenges of human-lion conflict. Whether or not these policies were expressly racist in design, they were certainly racist in effect. Unsupported and prohibited by the government from departing Kaokoveld due to policies of racialized isolation (GRSA 1964) and unable to make use of modern firearms or poisons, the pastoralists’ antagonistic feelings toward lions persisted. This hostility created challenges for conservationists in succeeding generations. Near the Etosha border in the late 1960s, one government official was requested by his ovaHerero companions to shoot a group of nearby lions. Lecturing them on the virtues of wildlife conservation was no use: “‘Lions are not animals,’ they insisted. ‘They are the devil’s children and should be killed wherever they are’” (Owen-Smith Reference Owen-Smith2010:135).

Conservation in Etosha

During the colonial period, access to northern “native” areas was tightly regulated for purposes of controlling human and livestock movements (Miescher Reference Miescher2012). With the vast majority of white areas having been converted to private rangelands, Etosha became one of the few places where white Namibians could view lions. Following the 1930s karakul sheep boom and World War II, Namibia’s white economy was on stronger footing; this gave birth to a robust domestic tourism market (Bravenboer Reference Bravenboer2007; Wellington Reference Wellington1967:126).

During the 1940s, Etosha lions increasingly functioned as a tourist attraction (NAN NAO 066 1947). By the 1950s, Etosha was becoming a haven for wildlife. At this point, lion conservation in northwest Namibia began in earnest; human-lion interactions were increasingly mediated by state officials aiming to conserve, not eradicate, the lions. Within the reserve, lions became objects of official responsibility and tourists’ affection. Tourism and wildlife management during this period was ad-hoc, leading to a variety of frightening, often surprising, and occasionally humorous interactions between tourists and lions. Accommodations were rough and ready, including camping at waterholes which were shared with wildlife. One time, two elderly women were confined to a restroom for hours as a lion pride encircled the structure. When one lioness fell into a half-filled swimming pool, a quick-thinking witness threw her a dry stump, which she clung to while the pool was refilled so she could climb out. It is not recorded where the staff hid themselves once she exited. At the Leeubron (‘lion source’) waterhole, when an emaciated lioness dubbed “Isabella” by the staff was struggling to provision five cubs, the Etosha staff routinely provided the group with wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus) and plains zebra (Equus quagga) carcasses. Routine feedings attracted other lions and the “lion restaurant” became a tourist attraction (de la Bat Reference de la Bat1982:16).

The provisioning of “Isabella” demonstrates a type of care for individual animal welfare directed from humans to lions. “Isabella” and a pride male named “Castor” were the first Etosha lions known to be given names—a practice that became increasingly common. Previously, predators only entered into human records as individuals following violent encounters with humans. With the rise of conservation, lions given individual identities by people became durable historical figures rather than generic members of their species (Maglen Reference Maglen2018). Human-animal historian Etienne Benson has shown that the naming of animals is associated with a set of ethical claims concerning their individual status and sentience (Reference Benson2016). Lions were transformed from fearsome pests into cosseted individuals, while in a similar manner the human-lion relationships in the Etosha region transformed dramatically in fewer than thirty years.

Lions in the park became further separated from white farmers and African pastoralists due to colony-wide government policies. In 1948, a conservative white nationalist government began implementing a decades-long series of racialized legislation, known as apartheid, that also affected human-wildlife interactions in Namibia. By simplifying, arranging, classifying, and ordering its human subjects and environments, the apartheid government sought to create what political scientist James Scott terms a “legible” state (Reference Scott1998). This process was implemented following the recommendations of the so-called “Odendaal Plan,” which was intended by apartheid planners to spatially organize Namibia upon “rational” planning principles (GRSA 1964; Heydinger Reference Heydinger2021). This included separating Etosha and its wildlife from the surrounding landscape by enclosing Etosha, thereby effectively keeping wildlife inside and livestock outside. The similarities between the apartheid government’s confinement of wildlife and the segregation of Africans are evident (Brown Reference Brown2002). Both took place with the support of white settlers who overwhelmingly stood on the side of colonial authority (Miescher Reference Miescher2012:152). The effects of the Odendaal Plan codified a new type of space for lions, one permanently free of livestock and the antagonistic human-lion interactions that came with their presence.

The effects of the Odendaal Plan coalesced and exacerbated transformations in human-lion relationships in Etosha and the surrounding areas. The creation of fencing separating Etosha from neighboring rangelands delineated differing human-lion interactions within the park and beyond its borders. As Etosha’s borders were fenced, first along its southern boundary in 1961–63 to control a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak, then completely in 1973 by 850 kilometers of “game-proof” fence, herbivores no longer migrated beyond the park, as many historically had done (Ebedes Reference Ebedes1976). This had unanticipated benefits for the lions. The confinement of prey species coincided with increased lion recruitment. In contrast, lions exploited gaps in Etosha’s fences, frustrating the efforts of both African and neighboring settler farmers to keep livestock safe. During this period, lion numbers in Etosha rose from an estimated 200 in 1953 to approximately 500 at the end of the 1970s (Berry Reference Berry1987). Henceforth, the park would serve as the source of lions in the region.

Disappearance in Kaokoveld

Following the Odendaal Plan’s policies of racialized isolation, Kaokoveld remained beyond the purview of government conservationists. Beginning in the 1960s, Kaokoveld existed on the edges of a brutal and active war zone. As a result, little quantifiable information is available concerning the fortunes of the lions that lived there. Official records on wildlife are not widely available from the 1960s through 1980; no systematic wildlife surveys were performed until 1976, and no government conservationists were posted to Kaokoveld until 1980.Footnote 9 However, it is known that the accelerating war for independence led to an influx of firearms and industrial poisons previously prohibited to the Africans, primarily from South African military personnel hoping to curry favor with local leaders (Owen-Smith Reference Owen-Smith2010:106; van Wolputte Reference van Wolputte2004). As a result, wildlife in Kaokoveld came under increasing persecution, both from residents seeking provisions and from elite government officials who used the region for illegal sport hunting (GRSA 1979; Owen-Smith Reference Owen-Smith2010:189).

Information concerning Kaokoveld lions during this period comes from scattered accounts and anecdotes, such as rumors that lions there were “maneless and generally grey in colour” (Tinley Reference Tinley1971:16). One key witness to this era was government official Garth Owen-Smith, who was posted to Kaokoveld from 1968 to 1970. Owen-Smith’s anecdotal accounts include his tale of finding four desiccated lion carcasses in the dunes near Cape Fria, and records of locals’ encounters with lions around northern villages and water points. In such accounts, lions primarily play the role of fearsome pests, frequently attacking livestock. They were, in turn, harassed and killed by the residents. Owen-Smith, a white South African, sought collegiality, respect, and friendship with Kaokoveld’s African residents, which was at that time an unusual practice. This enabled him to gather locally informed clues to the persistence of lions which otherwise would have gone unrecorded. In 1971, Owen-Smith estimated approximately forty lions residing in Kaokoveld with perhaps a few additional migrants from Etosha (Owen-Smith Reference Owen-Smith1971:50–52). Thought to have been formerly widespread, by the 1980s lions were considered greatly reduced by the use of firearms and poison (Hall-Martin et al. Reference Hall-Martin, Walker and Bothma1988:32). A dramatic reduction of predators from the 1970s to the 1990s is evident in the transformation of herding practices. Michael Bollig has shown that methods of “loose herding,” where livestock are escorted in the general direction of grazing and left to return home at night, developed during this period as a consequence of the greatly decreased danger from predators (Reference Bollig2020:268 n26).

The first comprehensive account of Kaokoveld lions was given by PJ “Slang” Viljoen. Finding that lions were nowhere plentiful, Viljoen conveyed a population poised to disappear,

The status of the lion in Kaoko[veld] is uncertain because it is intensively hunted down. Until recently, the lions were also killed by poison. Only in the inhospitable, uninhabited areas will the lions survive for a while, but with the opening of the area for four-wheel drive vehicles, these lions are no longer safe either.

(Reference Viljoen1980:349, translation by author)Viljoen’s pessimism was prescient. Beginning in 1978–79, drought struck Kaokoveld. This resulted in widespread livestock and wildlife starvation. Increased numbers of weak prey and carcasses temporarily benefited the lions. However, in the coming years, prey species were decimated; mountain zebra numbers declined by 84 percent, oryx by 87 percent, and springbok by 96 percent. Plains zebra disappeared entirely. Livestock experienced a similar decline (Owen-Smith Reference Owen-Smith2010:364–66). Among Himba residents, the drought was known as “Otjita” (the dying); it was a period defined by “a complete breakdown of herding” and “outright starvation and social disintegration,” signaling disaster for people and livestock (Bollig Reference Bollig2020:227). In contrast to the various forms of state assistance available to white farmers, minimal aid was offered to Kaokoveld pastoralists other than boreholes drilled to water their livestock (Bollig Reference Bollig2020:151–236; Botha Reference Botha2005). The geographic spread of the boreholes likely worsened the effects of drought. During the 1970s, pastoralists moved into rangelands which previously had lacked water. This expanded the reach and size of their livestock herds. When the rains failed in successive years, no grass remained in the newly exploited rangelands. As a result, herds dwindled, and starvation ensued.Footnote 10

The benefits of drought for the lions were short-lived. As prey numbers declined, lions began starving (Reardon Reference Reardon1986:31). The net effect was that lions and other predators increasingly troubled residents, exacerbating state policies that kept people hungry and poor. In one community, a lioness entered the schoolgrounds while children were present. Nearby, fourteen lions killed ninety-six sheep and seventeen goats in one evening (Owen-Smith Reference Owen-Smith2010:352–53). In early 1982, the last known human fatality occurred when a starving lioness killed a young child in her home. The lioness was shot by military personnel from a nearby fort while she was still consuming the girl’s body.Footnote 11 The effects of drought, combined with the influx of firearms and poison, likely led to locals killing lions in unprecedented numbers. Simultaneously, high numbers of lions were shot by professional hunters. During the drought, no fewer than seventy-six lions were killed in the southern part of the region alone. By 1986, it was estimated only twenty to thirty lions inhabited Kaokoveld (Reardon Reference Reardon1986:34, 40; Stander Reference Stander1990). By 1991, conservationists believed there were no lions remaining there (Stander Reference Stander2018:46). In contrast, lion numbers in Etosha declined, from an estimated 500 in 1980 to 200 in 1986, but quickly rebounded to an estimated 309 by 1989 (Berry Reference Berry1987; Stander Reference Stander1990, Reference Stander1991) (See Figure 2).

Figure 2. Desert-adapted lioness in Hoanib riverbed, 2019. Photo: A. Wattamaniuk.

Human-Lion Legacies of the Colonial Era

Following independence, human-lion relationships in northwest Namibia remain largely defined by the threat lions pose to livestock. Toward the end of the 1990s, a population of approximately twenty lions was discovered in Kaokoveld’s rugged Kharokhoab mountains. Augmented by lions dispersing from Etosha, this remnant population recolonized the southern Kaokoveld rangelands under the watchful gaze of increasingly powerful government, NGO, and local conservation partnerships. Initially this growing population primarily inhabited a government concession area free of livestock herds, thus limiting human-lion conflict (Stander Reference Stander2018).

In the new millennium, northwest Namibia became a wellspring of community-based conservation, and lion numbers grew. From 2000 to 2015, the estimated lion population increased from 39 to 180 (Stander Reference Stander2001; NMET 2017). The rising number and growing range of lions has generated heightened levels of human-lion conflict, leading to negative outcomes for lions as well as pastoralists. From 2000 to 2015, 80 percent of known lion (non-cub) mortalities, and one hundred percent of known sub-adult mortalities, were due to lions being killed by people (NMET 2017). Responding to increasing human-lion conflict, pastoralists still voice complaints reminiscent of their forebearers. Said one pastoralist, “The problem of the lion…lions come and kill someone’s cattle that they are living from. Living from the milk or whatever. That is when people are getting angry.”Footnote 12 For those pastoralists neighboring Etosha, the park is considered a source of conflict. Said one pastoralist living west of Etosha, “The lions that are coming into the kraal [and killing livestock] are the ones from Etosha. Because they are staying in[side] the fence and are not afraid of people.”Footnote 13 Such challenges are still exacerbated by what many locals consider asymmetric government and NGO responses to livestock and lion death: “The government is responding [to livestock deaths] by sending people, maybe one car. But if there is a lion injured, then they will maybe send eight cars.”Footnote 14 Anthropologist John Friedman (Reference Friedman2011) has shown that for many Kaokoveld residents, the government since independence still represents a form of personal and livelihood repression. Perceptions of human-lion conflict among pastoralists are consonant with such feelings of repression.

Because lions have been eradicated from white farmlands, the burden of conserving Namibia’s lions falls disproportionately on residents of the communal land (Owen-Smith Reference Owen-Smith2017; Heydinger Reference Heydinger2020c:183–214). This affects local responses to lions as well as human-lion interactions:

In the olden days my father and the people living here were killing lions. And so the lions were stealing [livestock and running] because the lion know, “if I kill something, they will track me.” But now, since independence, lions are taking out of the kraal and they are lying there and they are eating.Footnote 15

The return of human-lion conflict combines with the legacies of racialized colonial policies to constrain and undermine pastoral livelihoods. Social and economic prospects for residents are limited. Within the Sesfontein constituency, which encompasses the majority of contemporary “core lion range” in the northwest, 40 percent of residents live on USD1 per day or less, while 23 percent live on USD0.73 per day or less. In contrast, within the Outjo and Kamanjab constituencies south of Etosha, 18 and 19 percent of people live on USD1 per day or less, respectively, while 8 and 9 percent live on USD0.73 per day or less (NMET 2017:13; NNPC 2012).Footnote 16 The Kunene Region (encompassing present-day Kaokoveld) maintains Namibia’s highest primary school drop-out rates and only 55 percent of residents complete primary school by age seventeen (UNICEF 2013). Though these unequal social welfare outcomes are not driven by the challenges of human-lion conflict, they indicate the ongoing difficulties of local communities in overcoming some of the most damaging legacies of apartheid. Additionally, since 2011, drought is again dramatically constraining pastoral livelihoods. Lions have caused nearly one-fifth of average household cattle losses during the drought (Heydinger et al. Reference Heydinger, Packer and Tsaneb2019). Another pastoralist states his difficulties succinctly: “I am becoming poor because of lions.”Footnote 17

Conclusion

The contemporary geography of lions in northwest Namibia is largely the result of colonial era policies which supported white supremacy, favoring white settlers over African pastoralists. For Africans in Kaokoveld and Namibia’s underclass of white settlers, historical interactions at the human-livestock-lion nexus presented similar livelihood challenges, but had different outcomes, primarily due to racialized government interventions. While historians and anthropologists have previously examined the effects of colonial-era policies on African pastoralists and their livestock, this history reveals a key difference: the role of the state in resolving or heightening human-lion tensions by enabling or constraining human agency along primarily racial lines. While it is a well-worn path for African studies scholars to examine the role of the colonial state in enabling or constraining human agency, there is still great opportunity to examine the role of animals, particularly wild animals under state rule (Swart Reference Swart2019). This overlaps with research examining subaltern groups in colonial Africa. By giving equal or even greater voice to those who were politically, economically, and geographically marginalized (including the lions themselves), human-lion interactions are re-imagined as a diverse space where human social positions are as important as the presence or absence of livestock. By extending our scholarly examinations to other subaltern perspectives and to new frontiers of human-nonhuman interactions, African studies can continue to push scholarly conversations forward.

For scholars of Namibia’s colonial history, and for environmental historians more generally, the comparative approach between white and African experiences shows that a diverse set of human-environmental interactions is possible, even within neighboring landscapes during the same time period. The role of an interventionist government had a profound effect on human capabilities and therefore human interactions with wild species, often in unpredictable ways. This adds to a growing corpus of environmental historiography in which environmental factors become vectors for reproducing inequality. Ongoing inequality in northwest Namibia still places different people in different positions of relative vulnerability to human-lion conflict. It remains critical to draw on a variety of perspectives to challenge the dominant ideologies in human-environmental interactions and histories as they are commonly understood.

Within northwest Namibia (and likely beyond), human-livestock-(state-)lion interactions continue to reproduce certain social and economic inequalities, including the marginalization of African pastoralists and forms of white supremacy. For wildlife conservationists, the ongoing challenge of human-lion conflict is re-understood as a postcolonial outcome inextricably tied to racialized government policies. Human-lion conflict remains a space where people occupying different social and economic positions are more or less able to secure their livelihoods. As Mahesh Rangarajan has shown, “carnivores may not make social distinctions, but the uneven spread of wealth made some people far more risk-prone than others” (Reference Rangarajan2013:120). This history suggests that proactively responding to human-lion conflict entails not only wildlife and livestock management interventions, but possibly also reparative environmental justice practices. Lions no longer inhabit white farmland. The Etosha lion population, recently estimated at 400 individuals, appears secure (Heydinger, Packer, & Funston Reference Heydinger, Packer and Funstonunpublished). The communal lands of former Kaokoveld are the only spaces in the region where humans, livestock, and lions co-exist. Estimated at between 80 and 120 individuals (unpublished meeting minutes), this lion population has recently become the focus of government and NGO conservation efforts (NMET 2017). While it is a sad irony of this history that marginalized pastoral communities are increasingly burdened with the responsibility of conserving lions, it is a hopeful lesson that human-lion conflict is responsive to different interventions. These may include livelihood interventions, such as access to social services and economic opportunities, as a mechanism for at least lessening the financial burden of living alongside lions.

Both historians and conservationists deal with the change over time. While historians aim to account for the past, conservationists seek to implement evidence-based information to improve future prospects for wild species. Conservationists working in northwest Namibia may be able to create more durable, positive human-lion outcomes by incorporating lessons from this history. This includes a recognition that human-lion conflict when livestock are present is not a new experience, and likely does not have a “solution” as such. If the problem is intractable, it is not necessarily hopeless. Conservationists can work with local stakeholders and government to innovate new social and environmental approaches for creating less antagonistic relationships between pastoralists and lions without eliminating either from the landscape.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Macquarie University Big History Institute Anthropocene Grant, the Program in History of Science and Technology at the University of Minnesota, and Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC). Thanks to the staff at the Namibia National Archives and to Molly McCullers, Art Hoole, and Uakendisa Muzuma for providing additional primary sources. I am grateful to Emily O’Gorman and Sandie Suchet-Pearson for reading early drafts. Two anonymous reviewers as well as the journal editors are thanked for their comments which greatly improved the paper.

Competing Interest

The author(s) declare none.