Introduction

This article presents the argument that the Forum of Augustus in Rome was envisioned by the patron and the architect as integrated with the Forum of Caesar into one monumental complex. It also outlines a new theory of the location and design of the principal entrance into the two fora, which is identified with the Chalcidicum, mentioned by name by Augustus in the Res Gestae.

The history of the Fora of Caesar and Augustus has been analyzed, mostly individually, in a large number of scholarly publications. Their mutual spatial and functional relationship has not been explored due to the fact that the transition between them remains buried underneath the Via dei Fori Imperiali (Fig. 1). However, it has been traditionally represented in literature as a continuous wall, with three or five door-like openings, implying that separate ideas were at the foundation of each forum. I argue instead that the design allowed for a visual and functional connection between the two spaces, joining them into one urban composition rather than dividing them spatially and conceptually.

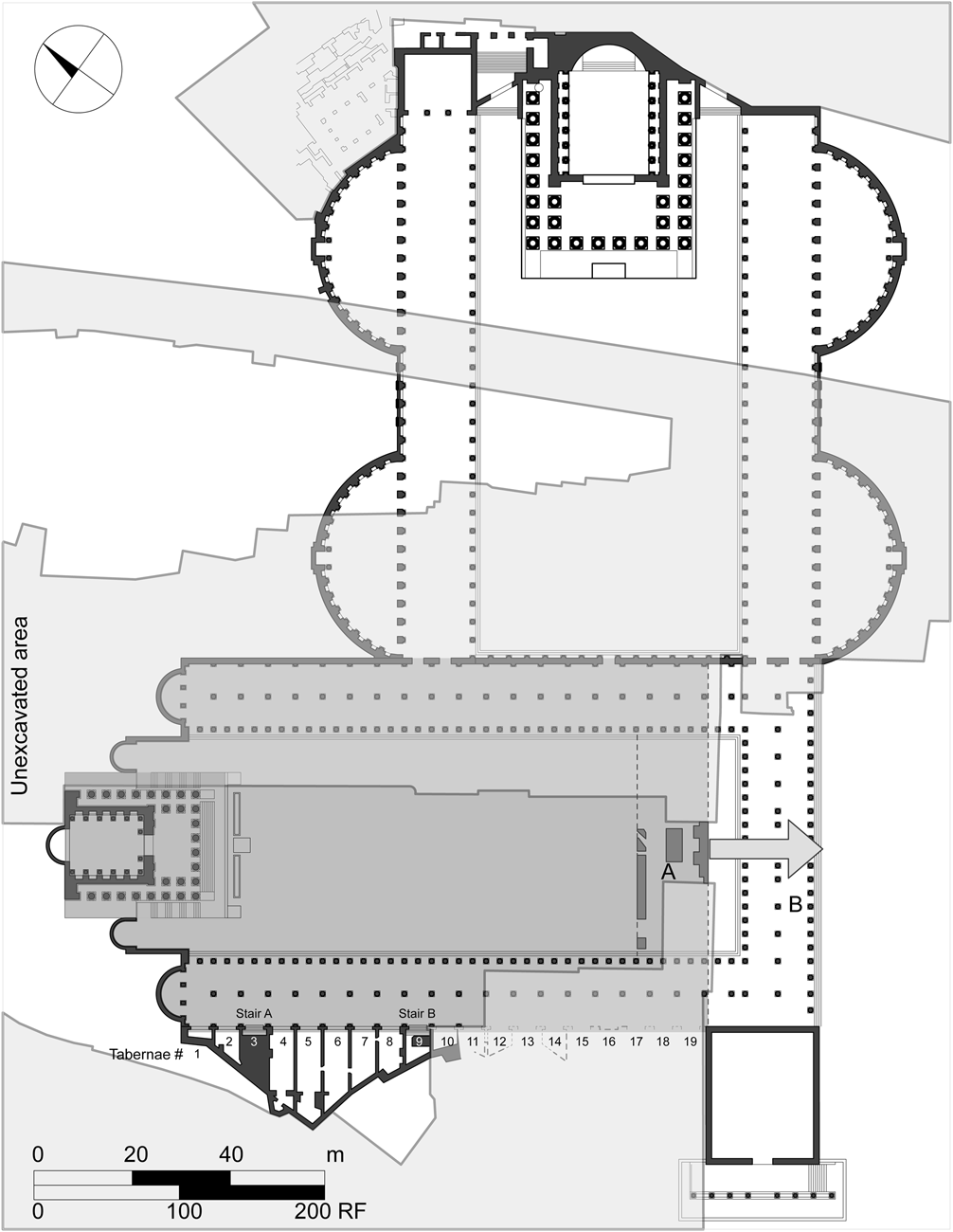

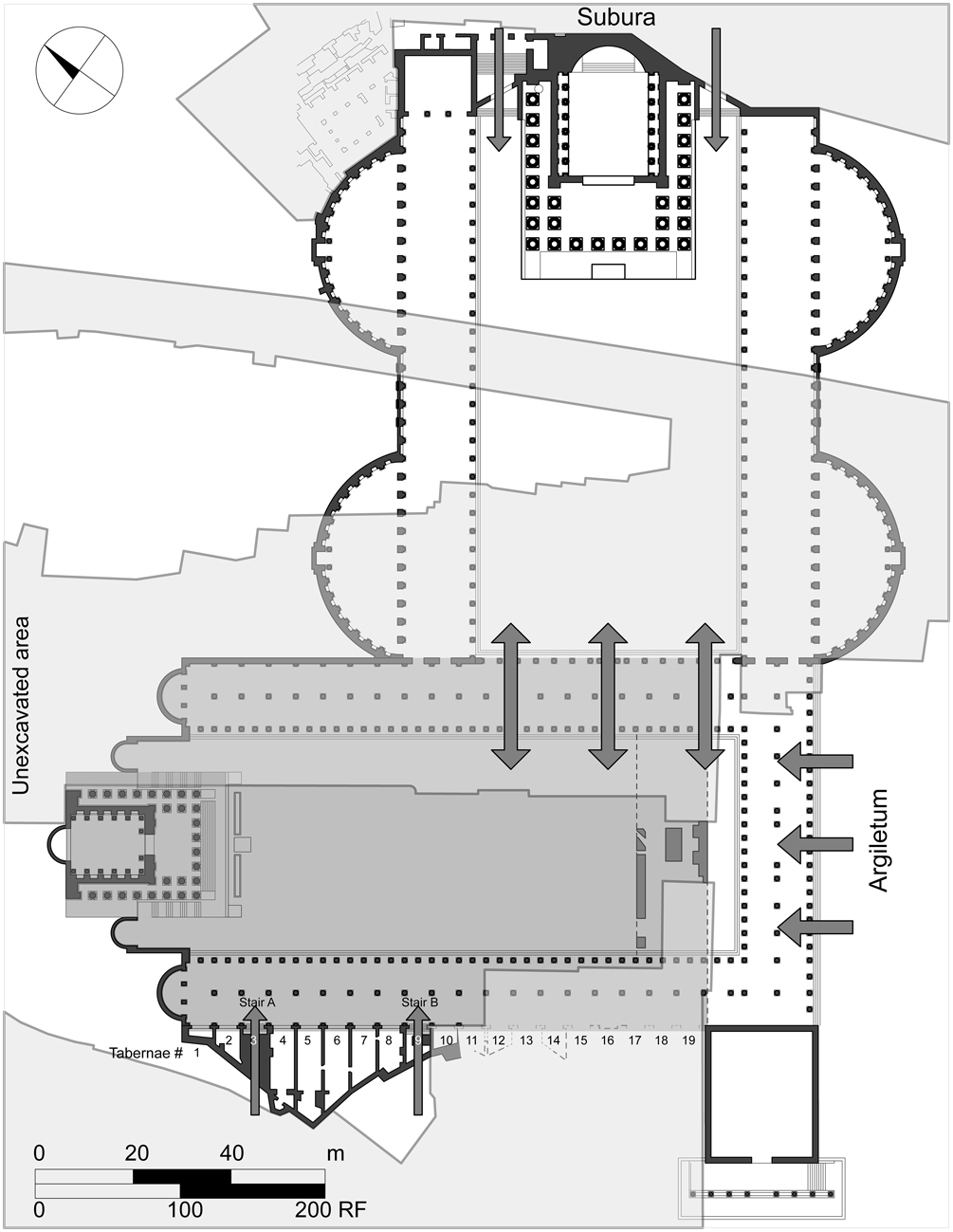

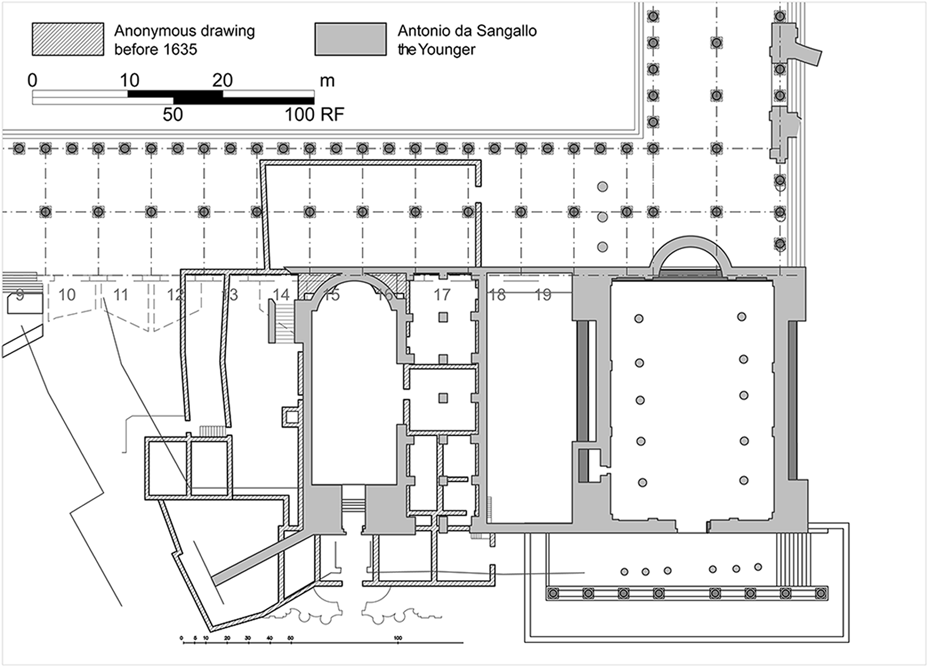

Fig. 1. The Forum of Augustus (above), Forum of Caesar (below), Curia Julia (bottom right), and “tabernae,” with their traditionally assigned numbers (bottom left). Unexcavated areas are in light gray. A marks the original length of the Forum of Caesar as constructed by Caesar; B marks the extension attributed to Augustus. (W. Fuchs.)

A new analysis of the archaeological, geometric, and historical data demonstrates that Augustus made a series of changes to the Forum of Caesar. The portico was extended by ca. 20 m toward the Argiletum and its design was significantly modified to harmonize it with the Forum of Augustus. A geometric study shows that the Temple of Mars Ultor was designed specifically to establish a sense of a spatial composition with the Temple of Venus Genetrix. I argue also that Augustus planned the main entrance to his forum through the Forum of Caesar, through a section of the portico that was open to both spaces. Finally, I present a hypothesis that the most important connection of the whole complex with the Roman Forum was just northwest of the Curia, through the Chalcidicum.

This new understanding of the design establishes a strong relationship between the urban layout of the area and the first emperor's political agenda. It conveys Augustus's vision of his forum as a continuation of the project of his adoptive father, in the same way as his political role in Rome as a Julian family legacy.

The historical context of the Fora of Caesar and Augustus

In order to understand the extent of Augustus's intervention in the design of the Forum of Caesar it is important to establish the project's level of completion at the time of Caesar's assassination in 44 BCE, as well as the objectives and consequences of the design changes introduced by his successor. Analysis of the historical events and processes shaping the two projects between 54 BCE and 2 BCE provides important context for the study of the material evidence.

It is generally accepted that the earliest reference to Caesar's plans to extend or otherwise make changes to the Roman Forum is found in a letter from Cicero to Atticus from 54 BCE (Cic. Att. 4.17):

And so we friends of Caesar ‒ myself and Oppius I mean, though you may explode with wrath at my confession ‒ have thought nothing of spending 60 million sestertii for that public work [monumentum] that you used to regard with praise, the extension of the forum and continuation of it as far as the Atrium Libertatis. We could not satisfy the private owners with less; but we will make it a most magnificent affair.Footnote 1

Whether the subject of the letter was in fact the future Forum of Caesar, as Ulrich thinks, or another project of similar significance is still a matter of dispute, the latter point of view being represented by Purcell.Footnote 2 Either way, the document nevertheless demonstrates Caesar's interest in improving the old Forum Romanum.

The next relevant date conveyed by Roman authors is 48 BCE. This is when, according to Appian (BC 2.102), “[Caesar] erected the Temple of Venus Genetrix as he had vowed to do when he was about to begin the battle of Pharsalus.” Ulrich explains the long interval since Cicero's letter by the evolution of the concept of the project.Footnote 3 He argues that Caesar originally intended it to be an expansion of the Roman Forum in its contemporary spatial character, by adding new structures with public functions. The idea of creating a separate urban entity of homogenous design, surrounded by a colonnade and dominated by a temple at its apex, materialized gradually, triggered by changes in the political situation and the urban context.

Regardless of when the design took its final shape, the new Forum of Caesar was planned as a place of great dignity. Appian continues (BC 2.102): “[Caesar] intended there to be a forum for the Roman people, not for buying and selling, but a meeting-place for the transaction of public business, like the public squares of the Persians, where the people assemble to seek justice or to learn the laws.” This gift to the city was naturally also a testimonial to the greatness of Caesar, just as the Theater of Pompey, with its vast quadriporticus, became the legacy of Pompey the Great.Footnote 4 The activity in the new forum would be sanctioned by the authority of Venus Genetrix, the divine ancestress of the Julian family and, by association, Caesar himself.

The Forum of Caesar and the Temple of Venus Genetrix were inaugurated by Caesar in 46 BCE. The amount of the actual work completed by then, and by Caesar's assassination in March 44 BCE, is not portrayed consistently by Roman historians. Cassius Dio's account (Cass. Dio 43.22.2‒3) can lead one to believe that everything was finished before the dedication in 46 BCE:

For he had himself constructed the forum called after him, and it is distinctly more beautiful than the Roman Forum; yet it had increased the reputation of the other so that that was called the Great Forum. So after completing this new forum and the temple to Venus, as the founder of his family, he dedicated them at this very time, and in their honor instituted many contests of all kinds.

According to Appian (again at BC 2.102), however, the temple was completed in 46 BCE but at the time of the dedication the forum was still mostly in the planning phase: “[Caesar] laid out ground around the temple … to be a forum.” The unfinished state of the porticos is further attested by Nicolaus of Damascus (Caes. 22), who writes about the famous incident at the beginning of 44 BCE, shortly before the assassination, during which Caesar received Roman senators on the podium of the Temple of Venus Genetrix:

Directly after this, another thing happened that greatly aroused the conspirators. Caesar was having a large handsome forum laid out in Rome, and he had called together the artisans and was letting the contracts for its construction. In the meanwhile, up came a procession of Roman nobles, to confer the honors which had just been voted him by common consent.Footnote 5

No historical source mentions the status of construction after Caesar's death until the Res Gestae (20) lists the forum among the deeds of Augustus: “I completed the Forum of Julius.” From this simple statement, it is impossible to gauge the degree of involvement of Caesar's adopted son in the undertaking. However, Augustus takes full credit (RG 20) for the construction of the Curia Julia, located against the southwest corner of the forum: “I built the senate-house and the Chalcidicum which adjoins it.”

Given the political context of the construction, the project of the Forum of Caesar emerges as a rather tumultuous undertaking. The Forum of Augustus had a more peaceful history; however, it saw some obstacles as well. According to Suetonius, the young Octavian made a vow to build a Temple of Mars Ultor before the Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE (Aug. 29.2). The text is not clear about whether the construction of the forum was part of the original idea. In the Res Gestae (21), the two parts appear together: “On my own ground I built the temple of Mars Ultor and the Augustan Forum from the spoils of war.” It is not known when the construction of the complex started, but its progress was apparently slow. The extremely long period between the initial vow and the dedication in 2 BCE has been commonly explained by scholars by difficulties with the acquisition of the land, drawing on a passage from Suetonius (Aug. 56.2): “he made his forum narrower than he had planned, because he did not venture to eject the owners of the neighboring houses.” Another reference to construction delays can be found in a less serious literary form. If we can trust Macrobius (Sat. 2.4.9), it was apparently the fault of the chief designer, because even Augustus himself complained about how slow the architect was.

Ultimately, the Temple of Mars Ultor was inaugurated in 2 BCE. Suetonius states (Aug. 29.1) that the forum and the porticos had been finished much earlier and used for public functions, but were not inaugurated separately:

His reason for building the forum was the increase in the number of the people and of cases at law, which seemed to call for a third forum, since two were no longer adequate. Therefore it was opened to the public with some haste, before the temple of Mars was finished, and it was provided that the public prosecutions be held there apart from the rest, as well as the selection of jurors by lot.

The main part of the Forum of Augustus did not see many architectural modifications until the fall of the Empire. The only significant change was the addition by Tiberius of two arches in honor of Drusus and Germanicus on the sides of the temple, and the removal of the two exedras on the south end of the porticos, to connect Augustus's project to the Forum Transitorium and the Forum of Trajan.Footnote 6 The Forum of Caesar, on the other hand, underwent several major transformations. Those undertaken by Augustus are the subject of this article and will be described in detail on the successive pages. After the death of the princeps, the most impactful alterations were realized during the period of Trajan, in conjunction with the construction of his forum.Footnote 7 The complex also had to be largely reconstructed by Diocletian after it was devastated by fire in 283 CE.Footnote 8

The first two Imperial fora stood alone for 77 years, until the Temple of Peace was completed in 75 CE. Two more monumental Imperial projects followed in quick succession, with the Forum Transitorium built by Domitian and Nerva and inaugurated in 95 CE, and the Forum of Trajan finished in 113 CE.

The construction timeline relative to the political context and the structure of power in Rome

Whatever the state of completion of the Forum of Caesar on March 15, 44 BCE, it is all but certain that construction work immediately stopped. This was because of the uncertain future not only of the funding but also of Julius Caesar's legacy: would he pass into history in glory or infamy? And would his project therefore be continued or abandoned? The ensuing conflict of the young Octavian and his supporters with Caesar's assassins took two and a half years to resolve, until the defeat and death of Brutus and Cassius in the Battle of Philippi in October 42 BCE. The forum project was most certainly stalled for this entire period. However, internal conflicts also continued past that date. Octavian was kept busy securing power until the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE. His political future was uncertain and his attention, as well as the funds that could otherwise have been directed toward a building program, had to remain dedicated to other matters.

Several correlations can be identified between these political events and building activity in Rome. The victory of Octavian and Mark Antony in 42 BCE must have resulted in a rush of confidence. It was expressed through the commitment to build the Temple of Divus Iulius and the announcement of the vow to build the Temple of Mars Ultor. However, soon after Philippi, new conflicts put a halt to the fragile surge of optimism. For the next six years the sources are silent about construction work in Rome, focusing instead on political intrigue, as well as warfare on many fronts and with multiple adversaries. An increase in building activity can be observed only after the defeat of Sextus Pompey in 36 BCE. Major public projects were undertaken by Agrippa in the city between 34 and 31 BCE (see Cass. Dio 49.42‒43). The Basilica Paulli (Aemilia) was also reconstructed by Lucius Aemilius Lepidus Paullus, from his own money, in 34 BCE (Cass. Dio 49.42). Restoration work on the Theater of Pompey, paid for by Augustus, took place around 32 BCE (see RG 20). It is possible to imagine, although this is not mentioned by the historians, that work on the first two Imperial fora was started (or restarted, in the case of the Forum of Caesar) around the same time.

The long period not spent on actual construction could have been used for design and planning. With the Temple of Mars Ultor vowed in 42 BCE, Augustus had plenty of time to work on the new project with his architect, while contemplating how to finish those projects started earlier and integrate them all into a unified composition. After the Battle of Actium, Augustus could finally dedicate himself and his money to realizing his ideas. This resulted in the dedications of the Temple of Divus Iulius, the Forum of Caesar, and the Curia Iulia, all in 29 BCE. These buildings had to be finished first because they were legacy projects; the memory of Caesar was used politically to further legitimize Augustus as his successor and to make a permanent mark on the Roman Forum through buildings bearing his name. As much as the temple, for obvious reasons, could not have been designed by Caesar, I also argue that the shape of the other two structures was mostly determined by Augustus according to an even greater vision. I will start with the analysis of the Forum of Caesar, which is essential for understanding the rest of the composition.

The design change of the Forum of Caesar

A very detailed study of the Forum of Caesar was published by Amici in 1991. It was based on the contemporary state of knowledge, which has since been improved by further excavations and analyses. Their cumulative results, including extensive new data on the archaic history of the site, were described by Delfino in 2014. These two publications are principal references for any new research, including the present article. Regarding the dating of various fragments of the site, it is important to highlight the opinion expressed by Amici that, from the point of view of the archaeological evidence, similarity in construction techniques makes it very difficult to unambiguously identify the earliest parts of the structure as either Caesarian or Augustan.Footnote 9 In the end, the only sections of the forum that Amici attributed to the latter were several elements of the staircases leading to the level of the porticos from the Clivus Argentarius through the so-called tabernae.Footnote 10 However, evidence has been found since the publication that sheds new light on the subject.

The full length of the portico of the Forum of Caesar, measured from the front of the Temple of Venus Genetrix, is ca. 121.4 m, or 410 Roman feet (RF). Amici attributed its plan and construction to Caesar. The 2006‒8 excavations inside the forum revealed a set of foundations stretching across the open space of the plaza, aligned more or less with the former Via Bonella, running north-northeast in the direction of the Forum of Augustus (Fig. 1: A). They were regarded as consistent with the construction style and the geometry of the portico of the Forum of Caesar and therefore identified as vestiges of the original southeast wing of the portico. It became clear that Caesar's plans for the forum assumed a shorter portico and that its final length was a design change (Fig. 1: B).Footnote 11

Delfino presented a theory that the modification was conceived by Julius Caesar and triggered by an authorization of the Senate to build the new Curia in 44 BCE.Footnote 12 He argued that at this point the dictator decided on the extant location of the building, as well as the extension of the porticos of his forum to the southeast. Augustus only carried out his adoptive father's design, leading up to the project's second inauguration in 29 BCE.Footnote 13 I argue however, that Octavian was responsible for the redesign of the Forum of Caesar, the location of the Curia Julia, and the execution of the project.

For Caesar to make so swift a decision about the location of the new Curia and a significant modification of his forum at the beginning of 44 BCE, two conditions would have had to be met. First, the authorization from the Senate would have had to be a surprise. Second, he would have had to order and approve the new design in the short, busy period between January, when the Senate made its resolution, and March 15.

The replacement of the Curia Hostilia was most likely always part of Caesar's plans for his forum, and part of his political maneuvers in the Senate. He clearly plotted to dissociate the Senate House from the family name of his political opponent Sulla, whose son was responsible for rebuilding it after the fire in 52 BCE, and to connect the structure with his name and his forum.Footnote 14 The old Curia was therefore demolished in 46 BCE under the pretext that a Temple of Felicitas had to be built on the same spot.Footnote 15 The timing was probably not a coincidence. It must have been done to eliminate the name of Sulla from the context of the future forum before the inauguration of Caesar's project, and to send a clear signal about who was in control of the entire northeast section of the old civic center of the city. The actual temple, built by Lepidus probably soon after 46 BCE, was not very consequential historically, as there is no further mention of it in any documents. It was probably intended from the beginning as a “placeholder” for Caesar's designs, but was most likely demolished by Augustus to make room for his vision for the area.

The consistency with which Caesar was pursuing the vision of his forum and its role in the civic center of Rome can also be recognized in the relocation of the Rostra. He had it moved probably in 45 or 44 BCE from its traditional place in the Comitium to a new one more or less on the axis of the Forum Romanum, closer to the Temple of Saturn and the Basilica Julia.Footnote 16 The gesture was bold, considering the tradition embedded in the historical location. But it allowed for a greater number of people to be addressed from the Rostra and it opened up the connection between the old Forum and the southeast wing of the Forum of Caesar.

Caesar's plans for the Curia may be also construed based on the original plan of his forum, if one considers why it was designed to be shorter in the first place, leaving around 70‒80 RF (20‒24 m) between its southeast end and the Argiletum. It is unlikely that this was a result of problems with land acquisition. Another possible explanation presents an enticing and powerful image: that Caesar planned to build the new Curia in that space, on the axis of the Temple of Venus Genetrix. There are a few facts that speak strongly in favor of the theory. First, the design would follow the model of the Porticus Pompeiana, which Caesar aspired to emulate with his project,Footnote 17 and in which the Curia was attached to the portico opposite the theater.Footnote 18 The new Curia Julia, if built according to the theory described above, would be in exactly the same relationship with the porticos of Caesar's forum. Second, the foundations of the original southeast wing of the portico of the Forum of Caesar demonstrate a possible architectural emphasis on the axis of the temple in the design.Footnote 19 Foundation blocks protruding from the continuous trench foundation of the back wall of the portico indicate the presence of columns or semi-columns. They could have framed the entrance from the portico into another structure (possibly the new Curia), the construction of which had not yet started (because Caesar was waiting for the authorization from the Senate). Third, the overall depth of a structure that could fit in the location described above could be as much as 75‒80 RF (ca. 22.2‒23.7 m), which would be 30% greater than the Curia of Pompey (ca. 60 RF or 18 m) and the same as the extant Curia Julia. Although the three observations presented above describe evidence of only a circumstantial nature, it is nevertheless clear that the connection between the new Senate House and the Forum of Caesar with the Temple of Venus Genetrix would seal the recognition of the dominant role of the gens Iulia in the political culture of Rome, and as such could have been extremely attractive to Julius Caesar.

It is also possible that Caesar planned to build his Curia in roughly the same location as the old one, though probably reoriented to align with his forum. The wide opening between the Senate House thus situated and the Basilica Paulli could have been intended as a connector between the old Forum and the principal entrance to Caesar's project, through the southeast wing of the portico. The plan of the foundations excavated in 2008 (Fig. 1) can also be interpreted as a propylaea on the axis of the temple, possibly similar to that of the Porticus Metelli.Footnote 20

Considering all the urban and political facets of the new forum project, it is hard to imagine that Caesar did not plan the location of the new Curia before he obtained the actual authorization from the Senate. He had to wait for the verdict before starting construction, but he could hardly have been surprised when approval came in January 44 BCE.

As for the second condition necessary for Caesar to be considered the author of the design change of his forum and the extant location of the Curia Julia, one must imagine that, if the dictator was in fact surprised by the decision of the Senate, he had very little time to contemplate numerous alternatives and to adapt his design to the new state of affairs, especially considering the political weight of every move. The decision to extend the porticos of the Forum of Caesar and place the new Curia in its present location required much more design consideration for the objectives and the broader context of the project. It could not have happened in the few days between January and March 15, 44 BCE.

Although a location for the replacement of the old Curia must have been part of Caesar's vision for his project, as discussed above, the extant site must have been decided later, by Augustus, relative to the new length of the portico of Caesar's forum and an altogether different idea of the urban composition of the northern quadrant of the old Forum. Therefore, the location of the Senate House relative to the change in length of the Forum of Caesar establishes important evidence regarding the development of the area: the design and construction of the Curia Julia must be attributed completely to Augustus, in agreement with his statement in the Res Gestae. Additional support for this theory and discussion of its consequences are presented below.

The size of the Forum of Caesar and the design of the porticos

The design change recognized in the archaeological evidence of the Forum of Caesar has great significance for our knowledge of the history of the area. Before the redesign, the open square of the Forum of Caesar was only marginally smaller than the future Forum of Augustus (Table 1). After the construction of the new southeast wing, it was about 22.5% larger than the original design and 20% larger than the Forum of Augustus. If Augustus was in fact behind the design change, as discussed above, it is difficult to assume that he enlarged his adoptive father's first project only to give it greater urban presence. The change must have been motivated by other objectives as part of a greater vision.

Table 1. Comparison of the dimensions of the Fora of Caesar and Augustus

An important piece of evidence for Augustus's redesign of Caesar's forum is preserved in its geometric framework. From the point of view of the development of the Roman portico, the design of the Forum of Caesar represents a more archaic model, the porticus duplex, similar to the description found in Vitruvius (5.9.1‒4). The southwest and northeast wings had two rows of columns and a perimeter wall, placed ![]() $22{1 \over 2}{\rm \; RF}$ apart, for a total depth of 45 RF. The southeast section was most likely open on both sides, therefore it had three rows of columns, with the same distance (

$22{1 \over 2}{\rm \; RF}$ apart, for a total depth of 45 RF. The southeast section was most likely open on both sides, therefore it had three rows of columns, with the same distance (![]() $22{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$) between them. The porticos of the Forum of Augustus, despite their greater depth (50 RF), were supported by the outside wall and just one row of columns. They were more advanced structurally and they must have appeared much lighter and more open. However, the analysis demonstrates that, despite the fundamental differences between the designs, they were carefully coordinated with each other.

$22{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$) between them. The porticos of the Forum of Augustus, despite their greater depth (50 RF), were supported by the outside wall and just one row of columns. They were more advanced structurally and they must have appeared much lighter and more open. However, the analysis demonstrates that, despite the fundamental differences between the designs, they were carefully coordinated with each other.

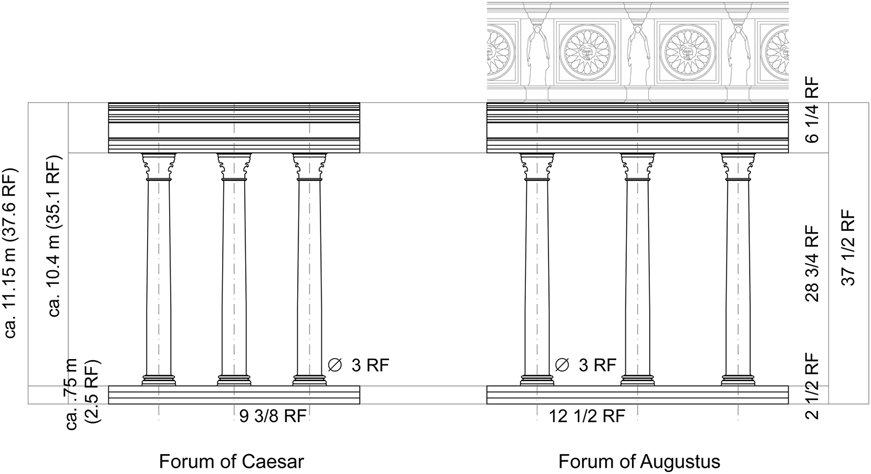

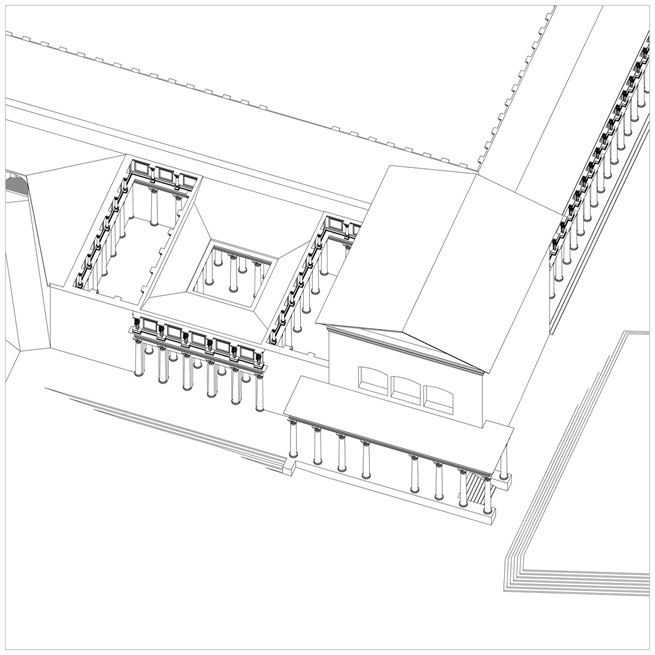

The present state of the porticos of the Forum of Caesar does not represent the original project well. The extant colonnade was re-erected in modern times from the elements found in situ, attributed to the reconstruction by Diocletian after the fire in 283 CE, when the original structure was replaced with much smaller columns reused from other sites.Footnote 21 The dimensions of the columns from the original period of construction were estimated by Amici based on the extant fragments encased in the wall between the Forum of Caesar and the Forum Transitorium. Their diameter was around 0.90 m (3.04 RF) and the overall height from the bottom of the column to the top of the cornice was 10.40 m (35.13 RF).Footnote 22 The height of the colonnade of the porticos of the Forum of Augustus was very similar: 10.36 m (35 RF). Considering the same diameter of the columns, it is possible to hypothesize that other vertical dimensions of the colonnades were also the same, as shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Reconstruction drawings of the elevation of the colonnades of the porticos of the Forum of Caesar and the Forum of Augustus during Augustan times. (W. Fuchs.)

Bearing in mind the order of construction of the two fora it would be natural to assume that Augustus followed the design of the colonnade established in Caesar's project. However, another piece of evidence points in the opposite direction. The geometric framework of the colonnade of the porticos of the Forum of Caesar is inconsistent with Roman design practice. It is not based on a square grid in plan: the distances between the rows of columns (![]() $22{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$) and thus the total depth of the portico (45 RF) are neither equal to, nor a simple multiple of, the interaxial distances between the columns

$22{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$) and thus the total depth of the portico (45 RF) are neither equal to, nor a simple multiple of, the interaxial distances between the columns ![]() $9{3 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$ in the front row and

$9{3 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$ in the front row and ![]() $18{3 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$ in the middle row; see Figure 3).

$18{3 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$ in the middle row; see Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Partial plan of the southwest portico of the Forum of Caesar with the “tabernae,” showing the geometric framework and the dimensions of the colonnade. (W. Fuchs.)

A comparative analysis shows that the layouts of extant monumental porticos found in Rome and its vicinity were always based on a square module: the portico's depth was a product of multiplying the interaxial distance between the columns by a simple value, such as 2, 3, or 4 (a few exceptions can be found in smaller provincial towns, but they were still based on values such as ![]() $1{1 \over 2}\;$or

$1{1 \over 2}\;$or ![]() $2{1 \over 2}$). A similar principle was applied by architects to the front elevation: the total height of the portico, including the steps, the columns, and the entablature, was a product of multiplying the interaxial distance between columns (in the front row, if it was a porticus duplex) by a simple integer number, most commonly 3 (Figure 4).

$2{1 \over 2}$). A similar principle was applied by architects to the front elevation: the total height of the portico, including the steps, the columns, and the entablature, was a product of multiplying the interaxial distance between columns (in the front row, if it was a porticus duplex) by a simple integer number, most commonly 3 (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Comparison of the geometric design framework of selected Roman porticos, in plan and elevation. (W. Fuchs.)

For example, the layout of the portico of the Forum of Augustus was based on a square of side ![]() $12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$, which is the interaxial distance between the front columns. The depth of the portico was 50 RF, or four

$12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$, which is the interaxial distance between the front columns. The depth of the portico was 50 RF, or four ![]() $12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$ modules. The height, including the steps, columns, and entablature (without the attic), was

$12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$ modules. The height, including the steps, columns, and entablature (without the attic), was ![]() $37{1 \over 2}{\rm RF}$, or three

$37{1 \over 2}{\rm RF}$, or three ![]() $12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$ modules. This way, three openings in the colonnade formed a perfect square in elevation, as illustrated in Figure 4. The design of the portico of the Temple of Peace was different but based on the same general principle. There, the height from the bottom of the steps to the top of the cornice has been reconstructed as ca.

$12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$ modules. This way, three openings in the colonnade formed a perfect square in elevation, as illustrated in Figure 4. The design of the portico of the Temple of Peace was different but based on the same general principle. There, the height from the bottom of the steps to the top of the cornice has been reconstructed as ca. ![]() $40{1 \over 2}\;{\rm RF}$ (Fig. 4).Footnote 23 The interaxial distance between columns was

$40{1 \over 2}\;{\rm RF}$ (Fig. 4).Footnote 23 The interaxial distance between columns was ![]() $13{1 \over 2}\;{\rm \;RF}$. The depth of the portico was three times this distance,

$13{1 \over 2}\;{\rm \;RF}$. The depth of the portico was three times this distance, ![]() $40{1 \over 2}\;{\rm \;RF}$, the same as the height. The same proportional system can be recognized in other porticos shown in Figure 4. Characteristically, the Portico of Octavia and the south portico in the Forum of Ostia used the

$40{1 \over 2}\;{\rm \;RF}$, the same as the height. The same proportional system can be recognized in other porticos shown in Figure 4. Characteristically, the Portico of Octavia and the south portico in the Forum of Ostia used the ![]() $22{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$ module (or its half,

$22{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$ module (or its half, ![]() $11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$), which is one of the two modules identified in the portico of the Forum of Caesar. The north portico in Ostia used the other module found in the Forum of Caesar:

$11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$), which is one of the two modules identified in the portico of the Forum of Caesar. The north portico in Ostia used the other module found in the Forum of Caesar: ![]() $9{3 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$. In all cases however, the layout was based on a grid of squares, not rectangles.

$9{3 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$. In all cases however, the layout was based on a grid of squares, not rectangles.

The unusual rectangular geometric framework of the portico of the Forum of Caesar indicates that most likely there was a change in design at a time when the depth of the colonnade had already been fixed by the foundations (built as continuous footings along the future rows of columns, which was standard Roman practice) but the columns had not yet been erected. Considering the conclusions of the previous section of the article, the redesign must have happened in the time of Augustus, when the Forum of Caesar was extended to the southeast.

The original geometric scheme of the porticos was most likely as depicted in Figure 5a. Their depth was 45 RF, with a distance of ![]() $22{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$ between the first and the middle rows and between the middle row and the back wall. The interaxial distances between the columns in the front row were

$22{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$ between the first and the middle rows and between the middle row and the back wall. The interaxial distances between the columns in the front row were![]() $\;11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$, and in the middle row

$\;11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$, and in the middle row![]() $\;22{1 \over 2}\;{\rm \;RF}$. If we apply the principles found in comparable projects to the hypothetical reconstruction of the original elevation, its height from the bottom of the steps to the top of the cornice should be

$\;22{1 \over 2}\;{\rm \;RF}$. If we apply the principles found in comparable projects to the hypothetical reconstruction of the original elevation, its height from the bottom of the steps to the top of the cornice should be ![]() $33{3 \over 4}\;{\rm \;RF}$ with the stairs occupying

$33{3 \over 4}\;{\rm \;RF}$ with the stairs occupying![]() $\;2{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$, the columns

$\;2{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$, the columns ![]() $25{5 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$ and the entablature

$25{5 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$ and the entablature ![]() $5{5 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$. According to modern reconstructions, a very similar design was most likely used in the Porticus Octaviae as built during the Augustan period, some time after 27 BCE.Footnote 24

$5{5 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$. According to modern reconstructions, a very similar design was most likely used in the Porticus Octaviae as built during the Augustan period, some time after 27 BCE.Footnote 24

Fig. 5. Comparison of the hypothetical original design of the porticos of the Forum of Caesar (A), the portico of the Forum of Augustus (B), and the portico of the Forum of Caesar as redesigned and finished by Augustus (C). The plan and the elevation drawings show the frequency of alignment of columns in the three designs: every 112½ RF between A and B and every 37½ RF between B and C. (W. Fuchs.)

As described above, the transverse measurements of the Forum of Caesar, as completed by Augustus in 29 BCE, remained unchanged. However, the longitudinal interaxial distances became ![]() $9{3 \over 8}\;{\rm \;RF}$ in the front row and

$9{3 \over 8}\;{\rm \;RF}$ in the front row and ![]() $18{3 \over 4}\;{\rm \;RF}$ in the middle row.. The height of the portico, including stairs, columns, and the entablature was increased to

$18{3 \over 4}\;{\rm \;RF}$ in the middle row.. The height of the portico, including stairs, columns, and the entablature was increased to ![]() $37{1 \over 2}\;{\rm RF}$ (Fig. 5c). Evidently, the modifications resulted in a geometric scheme that was at the same time disparate from the tradition and better coordinated with the design of the adjacent project of the Forum of Augustus.

$37{1 \over 2}\;{\rm RF}$ (Fig. 5c). Evidently, the modifications resulted in a geometric scheme that was at the same time disparate from the tradition and better coordinated with the design of the adjacent project of the Forum of Augustus.

The measuring units in the modular system of Roman portico design

This analysis of the design of the porticos requires additional explanation. It is evident that the modular dimensions of the porticos expressed in Roman feet do not comply with the opinion expressed by Wilson Jones that Roman architects had a preference for simple, whole-number measurements in their work.Footnote 25 However, further study demonstrates that the measurements listed above in fact become whole and simple when expressed in other standard Roman units, leading to the conclusion that the designers used those units rather than (or perhaps alongside) Roman feet. There were several standard units of length besides Roman feet: the palmipes (pl. palmipedes ‒ a foot and a palm: ![]() $1{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$, and its derivatives gradus and passus) and the cubit (a foot and a half:

$1{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$, and its derivatives gradus and passus) and the cubit (a foot and a half: ![]() $1{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}) $. Table 2 shows the portico measurements discussed above in Roman feet, palmipedes, and cubits, highlighting in each case the units that produce the simplest values.

$1{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}) $. Table 2 shows the portico measurements discussed above in Roman feet, palmipedes, and cubits, highlighting in each case the units that produce the simplest values.

Table 2. Comparison of the modular systems of the porticos discussed in the text (M = module), expressed in different standard Roman measuring units (RF = Roman feet, PP = palmipedes, CU = cubit)

Table 2 clearly demonstrates that the modular frameworks based on three out of the four values discussed above (![]() $9{3 \over 8}{\rm RF}, \;\;11{1 \over 4}{\rm RF}, \;\;{\rm and}\;12{1 \over 2}\;{\rm RF}) $ become very simple when expressed in palmipedes, as does the last one (

$9{3 \over 8}{\rm RF}, \;\;11{1 \over 4}{\rm RF}, \;\;{\rm and}\;12{1 \over 2}\;{\rm RF}) $ become very simple when expressed in palmipedes, as does the last one (![]() $13{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}) $ when expressed in cubits. The module used in the Forum of Augustus

$13{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}) $ when expressed in cubits. The module used in the Forum of Augustus ![]() $\left({12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}} \right)\;$looks particularly straightforward to the modern eye accustomed to working with the decimal system. Indeed, the measurements of the colonnade expressed in palmipedes are as follows: interaxial distance between columns,

$\left({12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}} \right)\;$looks particularly straightforward to the modern eye accustomed to working with the decimal system. Indeed, the measurements of the colonnade expressed in palmipedes are as follows: interaxial distance between columns, ![]() $10\;{\rm PP\;}\left({12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}} \right)$; total height of the colonnade from the ground level to the top of the cornice,

$10\;{\rm PP\;}\left({12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}} \right)$; total height of the colonnade from the ground level to the top of the cornice, ![]() $30{\rm \;PP\;}\left({37{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}} \right)$; height of the entablature,

$30{\rm \;PP\;}\left({37{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}} \right)$; height of the entablature, ![]() $5{\rm \;PP\;}\left({6{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}} \right)$; depth of the porticos, 40 PP (50 RF), etc. As simple as the framework is, the diameter of the columns, presumed to be 3 RF in the Forum of Augustus, does not seem to fit. It is very straightforward in the case of the Temple of Peace, where the width of 3 RF is equivalent to 2 CU. However, in the Fora of Caesar and Augustus, the same measurement cannot be expressed as a very simple number in palmipedes (

$5{\rm \;PP\;}\left({6{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}} \right)$; depth of the porticos, 40 PP (50 RF), etc. As simple as the framework is, the diameter of the columns, presumed to be 3 RF in the Forum of Augustus, does not seem to fit. It is very straightforward in the case of the Temple of Peace, where the width of 3 RF is equivalent to 2 CU. However, in the Fora of Caesar and Augustus, the same measurement cannot be expressed as a very simple number in palmipedes (![]() ${\rm D} = 2{{2} \over {5}}{\rm \;PP}$). However, a slightly larger value,

${\rm D} = 2{{2} \over {5}}{\rm \;PP}$). However, a slightly larger value, ![]() ${\rm Ddiam}. = 3{1 \over 8}{\rm \;RF\;} $ is exactly

${\rm Ddiam}. = 3{1 \over 8}{\rm \;RF\;} $ is exactly ![]() $2{1 \over 2}{\rm \;PP}$. The difference is only

$2{1 \over 2}{\rm \;PP}$. The difference is only ![]() ${1 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$ or 3.7 cm, and it is within a reasonable margin of error (4%). The

${1 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$ or 3.7 cm, and it is within a reasonable margin of error (4%). The ![]() $3{1 \over 8}$ RF diameter would result in a very simple ratio of the intercolumniation: 3 diameters

$3{1 \over 8}$ RF diameter would result in a very simple ratio of the intercolumniation: 3 diameters ![]() $\left(\left({12{1 \over 2}-3{1 \over 8}} \right)/3{1 \over 8} = 3\right)$. On the other hand, if the diameter was intended by the architect to be

$\left(\left({12{1 \over 2}-3{1 \over 8}} \right)/3{1 \over 8} = 3\right)$. On the other hand, if the diameter was intended by the architect to be ![]() $2{7 \over 8}\;{\rm \;RF\;}\left({2{3 \over {10}}{\rm PP}} \right), \;$ it would result in canonical (Vitruvian) proportions of 1:10 for the columns (

$2{7 \over 8}\;{\rm \;RF\;}\left({2{3 \over {10}}{\rm PP}} \right), \;$ it would result in canonical (Vitruvian) proportions of 1:10 for the columns (![]() $2{3 \over {10}}\;{\rm PP\;}\colon\; 23{\rm \;PP}) $. Evidently, at the scale of architectural detail Roman architects could choose which simple proportion was of greater importance for their projects. It is difficult now to determine their exact choices, due to the erosion of the stone and the typical variations in measurements of forms in stone.

$2{3 \over {10}}\;{\rm PP\;}\colon\; 23{\rm \;PP}) $. Evidently, at the scale of architectural detail Roman architects could choose which simple proportion was of greater importance for their projects. It is difficult now to determine their exact choices, due to the erosion of the stone and the typical variations in measurements of forms in stone.

Other interesting observations can be made based on the content of the table but they are beyond the scope of this article and will require a separate study. Nevertheless, the most important conclusion is that, despite their apparent complexity, the interaxial measurements found in the porticos of the Forum of Caesar were in fact elements of simple modular systems, fitting the theories previously described by scholars, even if they must be expressed in palmipedes or cubits. Regardless, to avoid confusion, this article will continue to use Roman feet as the primary measuring unit.

Returning to the discussion of the possible design change of the interaxial distances in the colonnade of the Forum of Caesar, from ![]() $11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$ to

$11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$ to ![]() $9{3 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$, we can easily observe that the latter modular system is clearly linked with the one based on

$9{3 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$, we can easily observe that the latter modular system is clearly linked with the one based on ![]() $12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$ through the value of

$12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$ through the value of ![]() $30\;{\rm PP\;}\left({37{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}} \right)$:

$30\;{\rm PP\;}\left({37{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}} \right)$:

The same simple relationship cannot be identified for the systems based in ![]() $12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$ and

$12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$ and ![]() $11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$. Since, according to Vitruvius (1.2.4 and 3.1.1), “symmetry” in architecture was created and expressed by mathematical or geometric ratios, we can assume that, in order to harmonize the design of the porticos of the Fora of Caesar and Augustus, the architect had to integrate their proportional systems into one. The greater mathematical simplicity of the ratio of

$11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$. Since, according to Vitruvius (1.2.4 and 3.1.1), “symmetry” in architecture was created and expressed by mathematical or geometric ratios, we can assume that, in order to harmonize the design of the porticos of the Fora of Caesar and Augustus, the architect had to integrate their proportional systems into one. The greater mathematical simplicity of the ratio of ![]() $12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF\;and\;}9{3 \over 8}{\rm RF\;}\left({{\rm better\;expressed\;as\;}10{\rm \;PP\;and\;}7{1 \over 2}{\rm PP}, \;{\rm \;or\;}4\,\colon\, 3} \right)$ vs. the ratio of

$12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF\;and\;}9{3 \over 8}{\rm RF\;}\left({{\rm better\;expressed\;as\;}10{\rm \;PP\;and\;}7{1 \over 2}{\rm PP}, \;{\rm \;or\;}4\,\colon\, 3} \right)$ vs. the ratio of ![]() $12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF\;and\;}11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF\;}( {{\rm or\;}10{\rm \;PP\;and\;}9{\rm \;PP}, \;{\rm \;or\;}10{\rm \;}\colon\; 9} ) $ illustrates why the interaxial distances between the columns of the Forum of Caesar had to be changed. The objective of Augustus's redesign of the colonnade of the porticos of the Forum of Caesar was therefore to coordinate the symmetry of the two projects, to create a sense of a single composition.

$12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF\;and\;}11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF\;}( {{\rm or\;}10{\rm \;PP\;and\;}9{\rm \;PP}, \;{\rm \;or\;}10{\rm \;}\colon\; 9} ) $ illustrates why the interaxial distances between the columns of the Forum of Caesar had to be changed. The objective of Augustus's redesign of the colonnade of the porticos of the Forum of Caesar was therefore to coordinate the symmetry of the two projects, to create a sense of a single composition.

In consequence of the above analysis, we must also revise the traditional attribution and dating of the so-called tabernae of the Forum of Caesar (Figs. 1, 3). Amici placed their construction in the second part of the original Caesarian period (46‒44 BCE). However, if the longitudinal distances between the columns in the portico were in fact part of the Augustan design intervention, then the cross-walls of the “tabernae” that follow the same scheme must have been constructed later as well. We must also reconsider the significance of a foundation made of blocks of travertine, ca. 2 RF wide, located directly in front of the entrances into the “tabernae.” Amici wrote that the portico of Caesar's forum had originally been enclosed at the back by a continuous wall, which was dismantled when the “tabernae” were built. She also demonstrated that the blocks of peperino used for the latter structure bear marks which can be identified as specific to the construction methods used when a new wall was built next to an older, pre-existing enclosure.Footnote 26 She concluded that Caesar's builders first erected a temporary travertine wall to support the roof of the portico before the construction of the “tabernae,” or to create an impression of the project having been completed at the time of inauguration in 46 BCE. However, from the point of view of the present study, another interpretation is more convincing: that Caesar's architects built a solid, continuous travertine wall at the back of the portico, which was dismantled when Augustus’s architects built the “tabernae” behind it (Fig. 6).

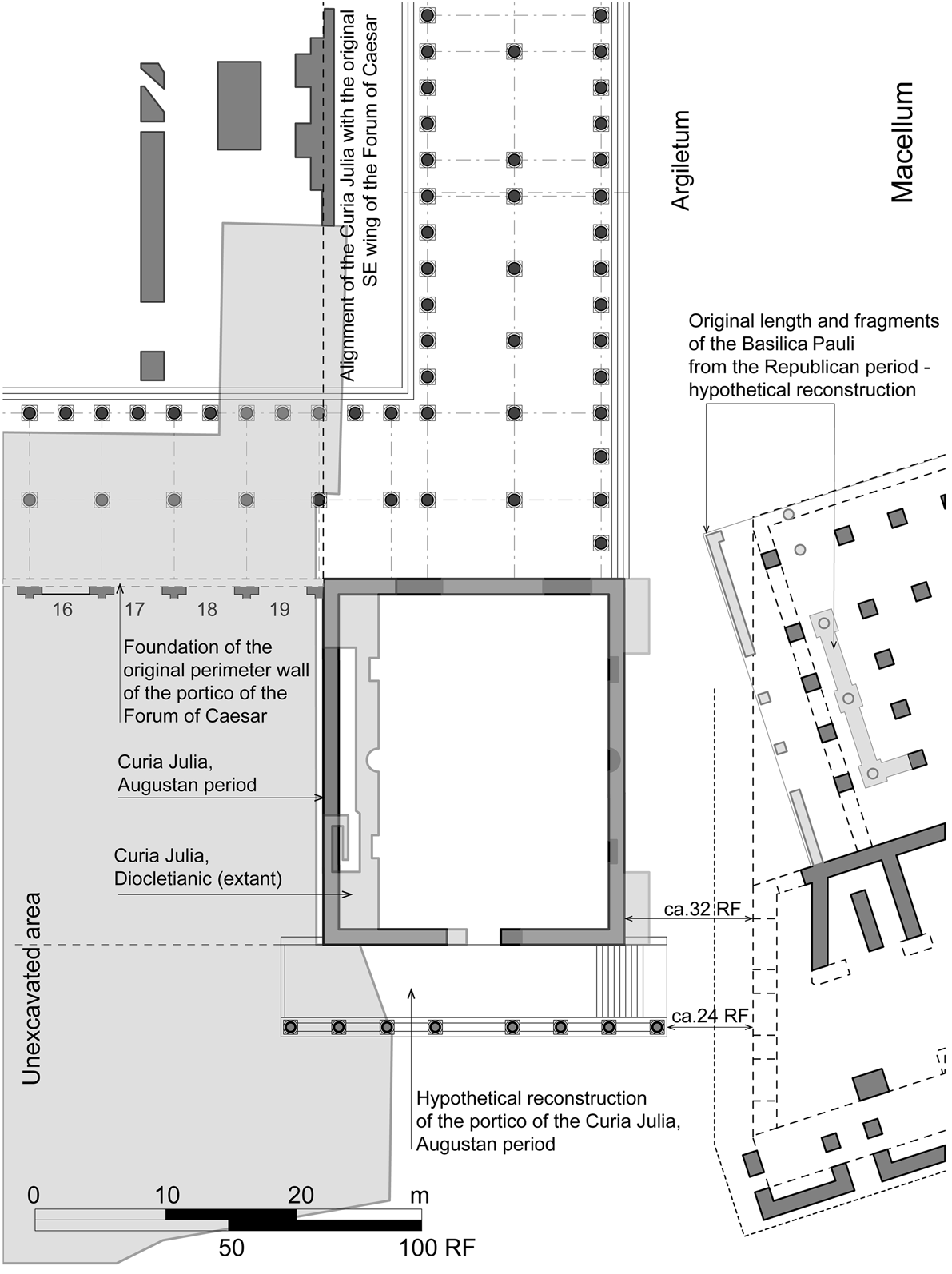

Fig. 6. Plan of the area immediately around the Curia Julia. (W. Fuchs.)

Amici also observed that the outside face of the back wall of the Curia Julia was aligned with the inside face of the travertine perimeter of the southwest portico of the Forum of Caesar. Further analysis shows that said wall starts precisely where the original, shorter portico built according to Caesar's plans ended. The width of the Senate House is therefore exactly the same as the extra length that Augustus added to the colonnades (Fig. 6). However, it also means that the back wall of the Curia was built as an extension of the original continuous perimeter wall, when Augustus increased the length of the Forum of Caesar and before the old wall was disassembled, and therefore before the new front wall of the “tabernae” was built. The latter was consequently set back 2 RF from the back wall of the Curia. According to the analysis presented by Amici, the façade of the “tabernae” was of uniform design and therefore represents a single construction period, with design variations due only to the different functions and heights of the spaces behind it. Therefore, although Amici dates the “tabernae” to the construction period between 46 and 44 BCE, it now becomes evident that they were constructed much later, after the Curia was finished and inaugurated in 29 BCE.

In the end, the following scenario for the design and construction of the porticos of the Forum of Caesar can be outlined:

1. The foundations of the colonnades of the porticos were laid under the patronage of Caesar, and the plan was to use

$11{1 \over 4}\;{\rm \;RF}\;$as the interaxial distance between the columns in the front façade and as the overall design module. Based on Roman design practices, the colonnade would have been

$11{1 \over 4}\;{\rm \;RF}\;$as the interaxial distance between the columns in the front façade and as the overall design module. Based on Roman design practices, the colonnade would have been  $33{3 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$ high to the top of the cornice. The overall length of the portico was ca. 310 RF (ca. 92 m).

$33{3 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$ high to the top of the cornice. The overall length of the portico was ca. 310 RF (ca. 92 m).2. A travertine perimeter wall was constructed under Caesar (its presence is confirmed only on the side of Clivus Argentarius).

3. The actual colonnades were either not started at all or were in a very early stage of construction at Caesar's death.

4. Construction stopped from 44 BCE until around 34 BCE.

5. After 34 BCE, Augustus made the following changes and/or completed the Forum of Caesar in the following ways: he extended the portico toward the Argiletum by ca. 67.5 RF (20 m), built the Curia Julia outside the portico's southeast corner, and redesigned the colonnades of the portico (with a new interaxial distance between columns of

$9{3 \over 8}\;{\rm \;RF}$, and an overall height for the colonnade of

$9{3 \over 8}\;{\rm \;RF}$, and an overall height for the colonnade of  $37{1 \over 2}\;{\rm \;RF}$, matching the Forum of Augustus).

$37{1 \over 2}\;{\rm \;RF}$, matching the Forum of Augustus).6. The “tabernae” between the southwest wing of the portico and the Clivus Argentarius were built after the rededication of the Forum of Caesar in 29 BCE.

I will argue below that the scope and nature of work undertaken by Augustus demonstrate that, when construction work resumed in the Forum of Caesar, it was according to a new comprehensive vision that today we would call a master plan, which included the Forum of Augustus and the entire north section of the Roman Forum. Thus, the modifications of the original design must be considered through the lens of the broader urban and architectural context. But first one must examine the possible objectives of the internal composition.

The design of the porticos of the fora and the Temples of Venus Genetrix and Mars Ultor

Although the dimensions and proportions of the colonnades as planned originally by Caesar are only speculation based on a study of similar projects and an established set of common practices, their final form after 29 BCE undeniably matched the column size and vertical dimensions of the porticos of the Forum of Augustus. I argue that the interaxial distances between the columns were part of the same objective: to coordinate the rhythm of the columns in the Forum of Caesar with the Forum of Augustus. If the two colonnades had been built with interaxial distances of ![]() $11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$ and

$11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$ and ![]() $12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$, their columns would align every 125 RF, or every 11th column in the former and every 10th column in the latter. If we substitute

$12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$, their columns would align every 125 RF, or every 11th column in the former and every 10th column in the latter. If we substitute ![]() $9{3 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$ for the

$9{3 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$ for the ![]() $11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$, the columns align every

$11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$, the columns align every ![]() $37{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$, or, respectively, every fifth and fourth column (Fig. 5). Additionally, since the height of the columns and the entablature, after the redesign, was the same in both projects (respectively

$37{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$, or, respectively, every fifth and fourth column (Fig. 5). Additionally, since the height of the columns and the entablature, after the redesign, was the same in both projects (respectively ![]() $6{1 \over 4}$ RF and

$6{1 \over 4}$ RF and ![]() $28{3 \over 4}$ RF), the modular square segment of the elevation was

$28{3 \over 4}$ RF), the modular square segment of the elevation was ![]() $37{1 \over 2}$ RF in both cases – three intercolumniations in the Forum of Augustus and four in the Forum of Caesar. Altogether, the two designs, despite their differences, were well harmonized and allowed the creation of a smooth transition from one colonnade to the other.Footnote 27

$37{1 \over 2}$ RF in both cases – three intercolumniations in the Forum of Augustus and four in the Forum of Caesar. Altogether, the two designs, despite their differences, were well harmonized and allowed the creation of a smooth transition from one colonnade to the other.Footnote 27

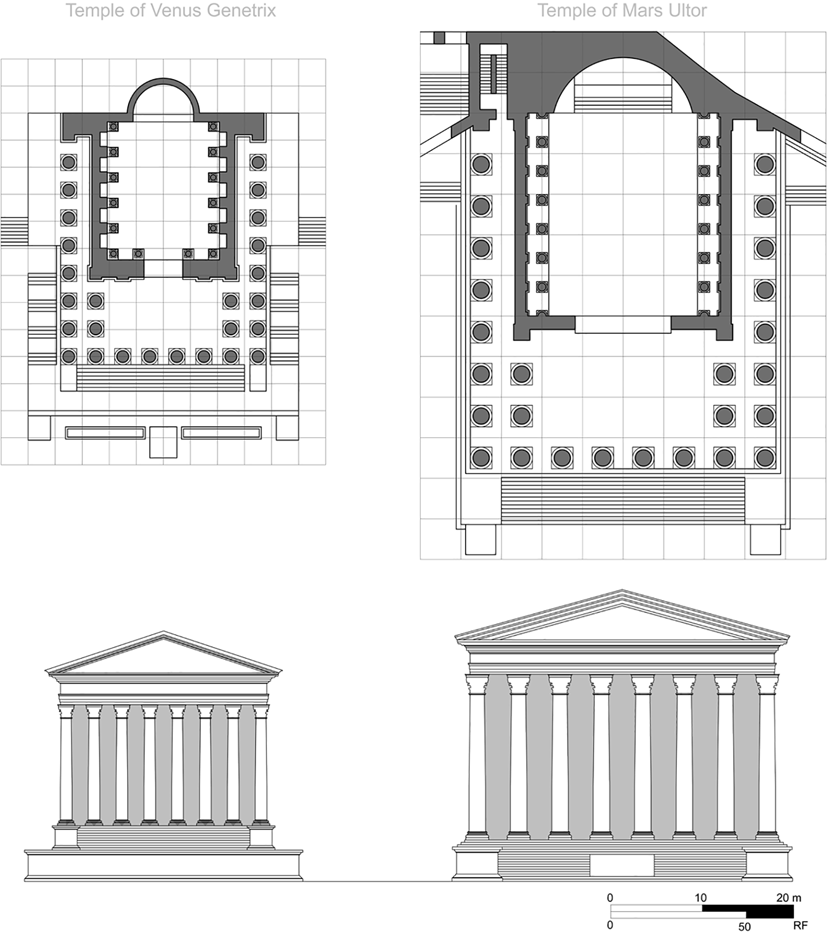

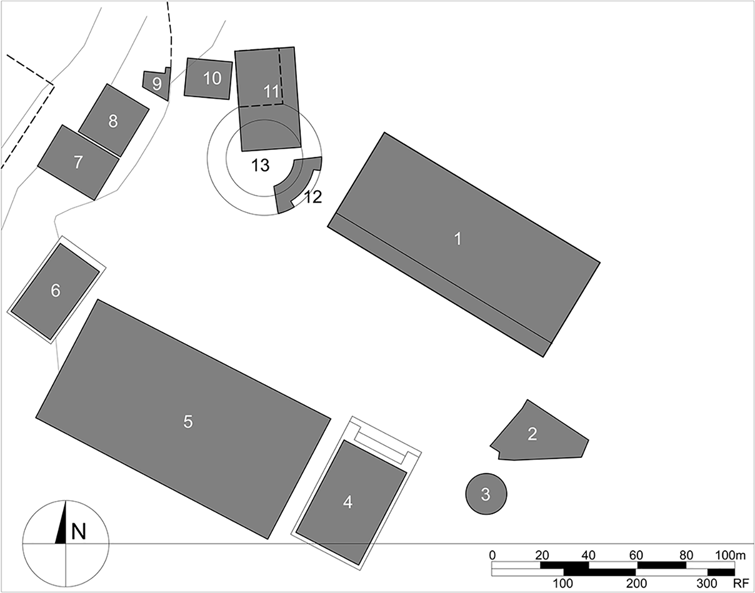

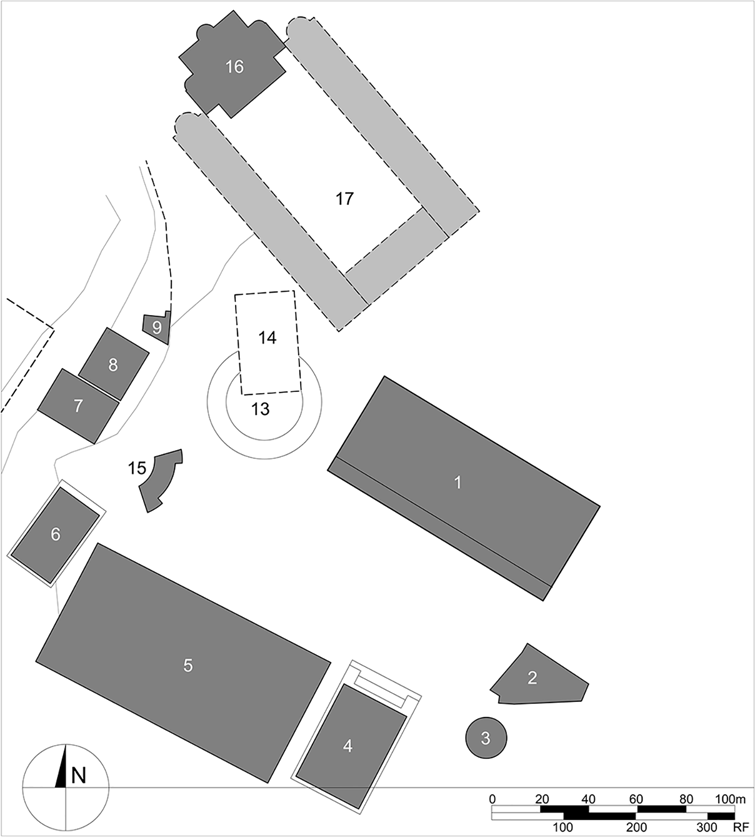

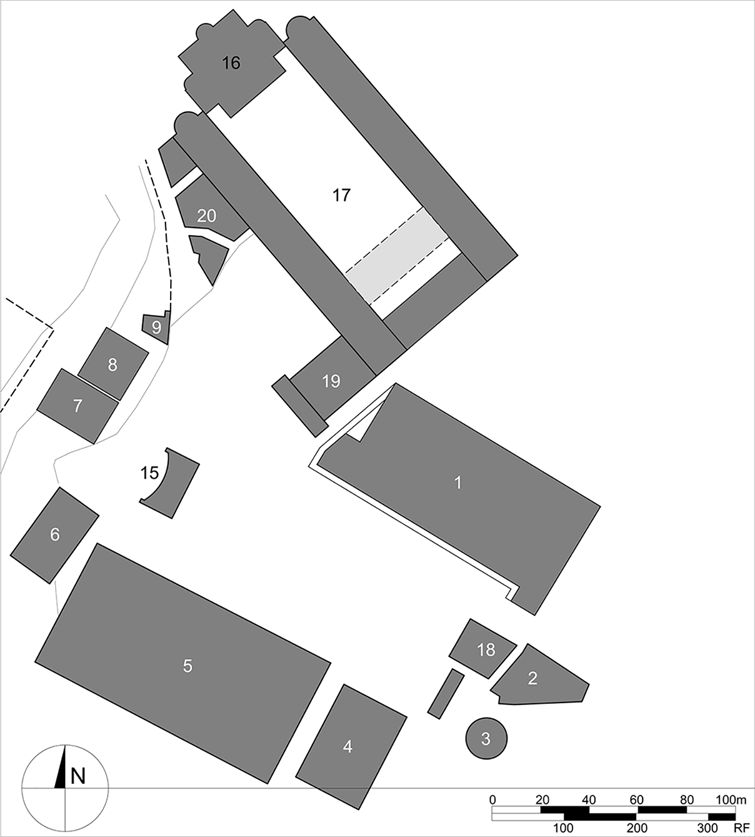

Important evidence of Augustus's intentions for the composition of the fora is found in the designs of the temples of Venus Genetrix and Mars Ultor. A study of their geometric framework shows that the latter was exactly 50% larger in plan than the former.Footnote 28 The width of their front façades were, respectively, 80 RF and 120 RF. The same relationship did not apply to all the architectural details, but the remarkable ratio in the overall scale of the structures is clearly visible in Figure 7.

Fig. 7. Comparison of the size of the Temple of Venus Genetrix (with an underlying grid of 10 RF) and the Temple of Mars Ultor (with a grid of 15 RF). (W. Fuchs.)

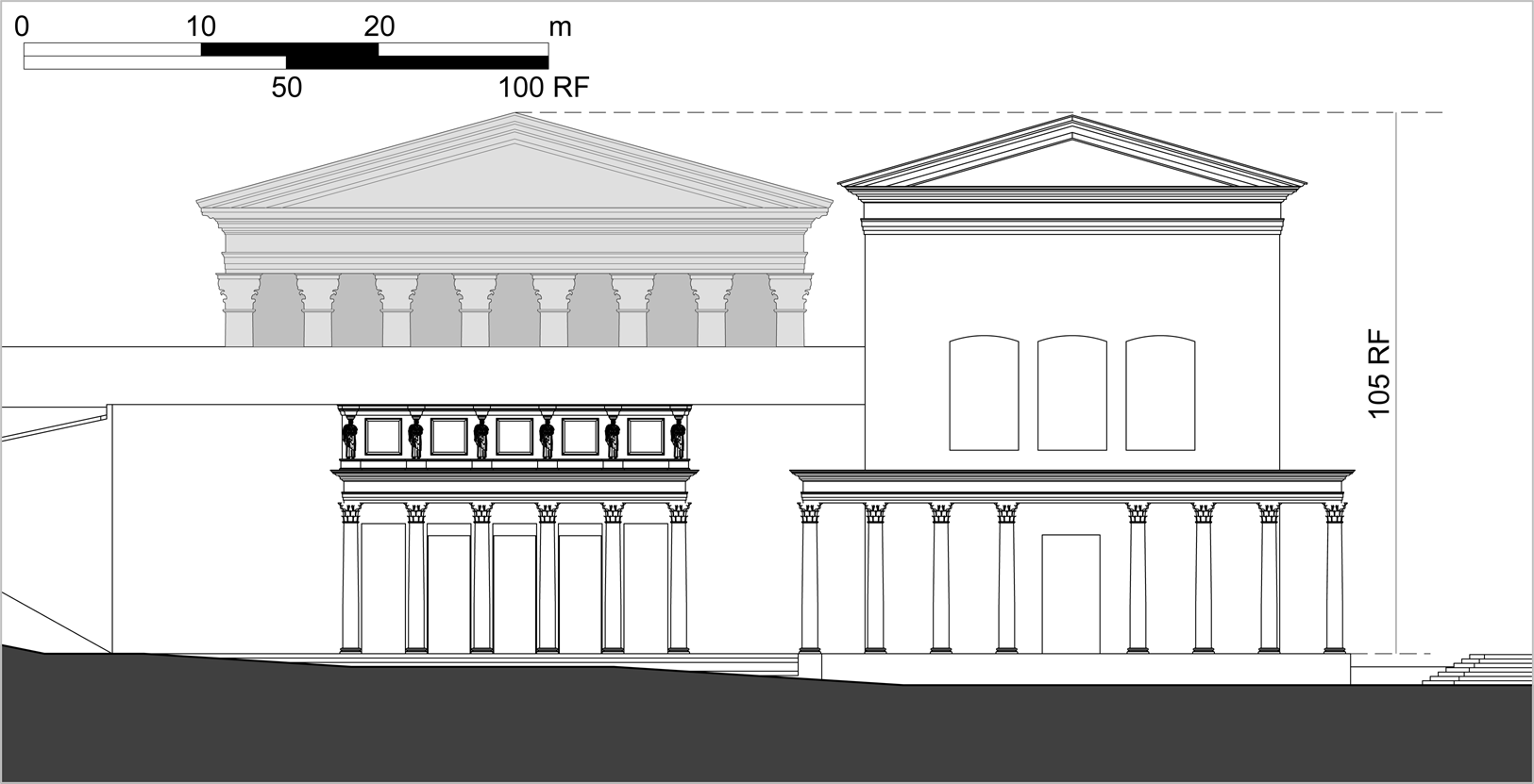

When the temple of Mars Ultor was built, it was bigger than any other shrine in Rome save the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus.Footnote 29 Was the size of Augustus's temple simply a result of vanity, or had he another reason? Did he want to manifestly overshadow his adoptive father? A geometric analysis shows that this decision was very likely dictated by the compositional needs of the two fora. The main axis of the Forum of Augustus is at exactly 90° to the axis of the Forum of Caesar. Their intersection falls within the plaza of the latter, at a distance of ca. 83 m (280 RF) from the front of the temple. The distance from the same point to the front of the Temple of Mars Ultor is ca. 124.5 m (420 RF), exactly 50% greater (Fig. 8). It means that, from the intersection of the two temples’ axes, they would appear to be precisely the same width.

Fig. 8. Plan of the Fora of Caesar and Augustus showing the distances to the temples from the intersection point of their axes. The plan shows a hypothetical design of the open portico between the fora. Circle A indicates the location of the segment of the wall along the northeast perimeter of the Forum of Caesar excavated in 2005–8. (W. Fuchs.)

It is impossible to relegate this precise relationship to the realm of coincidence. We must consider instead that the Temple of Mars Ultor was planned by the architect and the patron to be visible from the inside of the Forum of Caesar, together with the temple of Venus Genetrix, and to be seen as its equal in size. The principle upon which this visual effect was designed was well known in antiquity. It had been described 300 years earlier by Euclid, on the first page of his Optics: “those things seen within a larger angle appear larger, and those seen within a smaller angle appear smaller, and those seen within equal angles appear to be of the same size.”Footnote 30 The statement is equivalent to the visual effect realized by Augustus and his architect: two objects that are of different dimensions will appear to be exactly the same size if the ratio of their distances from the viewer is the same as the ratio of the sizes of the objects to each other. Admittedly, the height of the Temple of Mars Ultor was not 50% greater than the Temple of Venus Genetrix. Based on the available data, the former was ca. 105 RF and the latter ca. 90 RF. I will present a possible explanation for this apparent inconsistency below.

In order for the two temples to be seen together, the two fora could not have been separated by a wall with small doors only. The stretch of portico shared between the two projects, and exactly opposite the Temple of Mars Ultor, had to be open on both sides or otherwise allow for visual connection between the adjacent spaces (Fig. 8). A variety of designs can be imagined that would satisfy this requirement, but each would require the geometric coordination of the two colonnades. Hence the change of overall vertical proportions and the interaxial distances of the portico of the Forum of Caesar described above. The common module of ![]() $37{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF\;}( {30{\rm \;PP}} ) $ of the plan and the height of the colonnade allowed the architect to easily harmonize the design on both sides of the open portico. This would not have been possible if the original interaxial distance between the columns (

$37{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF\;}( {30{\rm \;PP}} ) $ of the plan and the height of the colonnade allowed the architect to easily harmonize the design on both sides of the open portico. This would not have been possible if the original interaxial distance between the columns (![]() $11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}) $ and the vertical dimensions of the colonnade (

$11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}) $ and the vertical dimensions of the colonnade (![]() $33{3 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$) of the porticos in Caesar's forum were kept.

$33{3 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}$) of the porticos in Caesar's forum were kept.

The extent of the opening and visual connection, and the exact design of the portico separating the two fora cannot be determined with certainty without a systematic archaeological study of the area. At this point only a fragment of the presumed wall between the two projects has been excavated.Footnote 31 It is a short wall segment that would have been located at the juncture of the southeast colonnade of the Forum of Augustus and the northeast edge of the Forum of Caesar (Fig. 8: A). Its character indicates a wall end, or a break in the wall, to the northwest. This might have been either a door-sized opening or a larger aperture. The find is too small to indicate the character of the entire portico. The wall could indicate that the opening between the two spaces was significantly narrower than the full width of the Forum of Augustus (for example, taking the form of an extended propylaea), or that it was a transitional element, very limited in length, where the colonnades of the two fora met.

The hypothesis of an open portico between the Fora of Caesar and Augustus challenges the prevailing theory of the Imperial fora being individual urban entities, as described by La Rocca.Footnote 32 Archaeological evidence points to only relatively small openings between them, with nothing at the scale postulated in this article. However, Rome at the time of Augustus included examples of porticos with monumental entrances. One is the Porticus Octaviae, located near the Theater of Marcellus. Reconstructions of its predecessor on the site, the Porticus Metelli, indicate a solid wall at the front with a series of small openings and possibly a four-column entrance in the center.Footnote 33 However, the project commissioned by Octavian after 33 BCE featured a continuous open portico instead, with a monumental propylaea on the axis.Footnote 34 Similarly, the southeast portico of the Forum of Caesar as redesigned by Augustus had an open colonnade facing the Argiletum, instead of a solid wall.Footnote 35 The choice between a wall and an open portico was most likely based on the particular urban context. It cannot be said, however, that an open colonnade between the Fora of Caesar and Augustus would have stood out against the principle, formulated by modern scholars, that the Imperial fora were always completely walled in with only small-scale, controlled passageways between them. There were clearly some structures where open porticos were used to create a broad opening between adjacent spaces, and the same concept could have been used by Augustus to connect his forum to his adoptive father's.

Analysis of the proportional systems of the two fora demonstrates that the architect harmonized the projects in a truly expert way, including the symmetry between the designs of the porticos and the temples. As shown in Figure 7, the podium of the Temple of Mars Ultor was planned on a 15 RF grid. The height of the front façade to the top of the cornice was ![]() $87{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$. It was divided into seven equal parts of

$87{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$. It was divided into seven equal parts of ![]() $12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$. The top segment or H(e) was used for the height of the entablature. The bottom H(e) was the height of the podium, and the five H(e) in the middle

$12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$. The top segment or H(e) was used for the height of the entablature. The bottom H(e) was the height of the podium, and the five H(e) in the middle ![]() $\left({62{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}} \right)$ became the height of the colonnade with the three-step stylobate.Footnote 36 Thus the cumulative height of the stylobate, the colonnade, and the entablature was 6 H(e) or 75 RF. The height of the portico of the forum to the top of the cornice was exactly half of that distance,

$\left({62{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}} \right)$ became the height of the colonnade with the three-step stylobate.Footnote 36 Thus the cumulative height of the stylobate, the colonnade, and the entablature was 6 H(e) or 75 RF. The height of the portico of the forum to the top of the cornice was exactly half of that distance, ![]() $37{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$. Similarly, the height of the entablature of the portico was half that of the entablature of the temple (

$37{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}$. Similarly, the height of the entablature of the portico was half that of the entablature of the temple (![]() $6{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}\;{\rm and}\;12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}) $. The modular dimension H(e) = 12½ RF of the temple was also used as the interaxial distance between the columns, and the basis for the depth of the portico (

$6{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}\;{\rm and}\;12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF}) $. The modular dimension H(e) = 12½ RF of the temple was also used as the interaxial distance between the columns, and the basis for the depth of the portico (![]() $4\times 12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF} = 50\;{\rm \;RF}$; Fig. 9).

$4\times 12{1 \over 2}{\rm \;RF} = 50\;{\rm \;RF}$; Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Comparison of the main elements of the geometric design framework (symmetry) of the elevations (ichnographia) of the temples of Venus Genetrix and Mars Ultor, and the porticos of the Fora of Caesar and Augustus. All dimensions are in Roman feet. (W. Fuchs.)

The original design of the portico of the Forum of Caesar was not coordinated with the proportional system of the Temple of Venus Genetrix in the same way. However, the redesign apparently fixed the problem, at least to some degree. The same design methodology described above for the Temple of Mars Ultor was used in the temple of the patron deity of Caesar, although with different mathematic values. The height of the entablature, H(e) (without the sima), was ![]() $9{3 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$. The columns were 4½ H(e) or ca. 42.2 RF and the upper podium was 1 H(e). Although the original intercolumniation of the portico of the forum (

$9{3 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}$. The columns were 4½ H(e) or ca. 42.2 RF and the upper podium was 1 H(e). Although the original intercolumniation of the portico of the forum (![]() $11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}) $ cannot be identified among those numbers, its redesigned value

$11{1 \over 4}{\rm \;RF}) $ cannot be identified among those numbers, its redesigned value ![]() $\left({9{3 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}} \right)$ is the same as the H(e) (Fig. 9). Clearly, in both cases one of the goals of the architect was to harmonize the way in which the porticos of the fora reflected the geometric system of the temples. However, not all dimensions in the Forum of Caesar were coordinated as precisely as in the Forum of Augustus, demonstrating the limited freedom that the architect had in working with the already existing temple and unfinished portico of the complex.

$\left({9{3 \over 8}{\rm \;RF}} \right)$ is the same as the H(e) (Fig. 9). Clearly, in both cases one of the goals of the architect was to harmonize the way in which the porticos of the fora reflected the geometric system of the temples. However, not all dimensions in the Forum of Caesar were coordinated as precisely as in the Forum of Augustus, demonstrating the limited freedom that the architect had in working with the already existing temple and unfinished portico of the complex.

The coordination of dimensions between the whole and all individual parts of buildings was a tool for creating visual harmony in design, which Vitruvius called “symmetry,” as mentioned above. Undoubtedly, a very large project, such as the Forum of Augustus, required a highly disciplined geometric framework to organize and control the design and later the construction work. As we appreciate its precision, we must consider, as discussed above, that Augustus and his architect had a lot of time to plan the work.

For Augustus, the legacy of his adopted father provided a necessary legitimization of his own status. A great part of the iconography of the Forum of Augustus was dedicated to the real and mythical members of the gens Julia and their great deeds.Footnote 37 Altogether, the forum was envisioned as a lesson in a history of devotion to Rome, in which the family of Caesar and Augustus were the main characters. Although this political agenda is no substitute for material evidence of the spatial relationship between the two fora, all findings presented so far confirm that the composition of the two fora was specifically designed by Augustus to amplify the political message: they were separate, but joined by the same purpose, the special role of the Julian legacy in the history of Rome. It is therefore extremely difficult to imagine that Augustus would have missed the opportunity to display the unity of idea through architecture, by separating his project from his adoptive father's.

The project features discussed above – the composition of the temples and the redesign of the colonnade of the Forum of Caesar were clearly instruments of spatial and conceptual integration of the two fora, and as such they pertain mostly to the internal structure of the plan. However, the choice of location for the Forum of Augustus, the extension of the portico of the Forum of Caesar, and the placement of the Curia Julia were decisions that must also be examined in relation to the urban context.

The urban location and the entrances to the fora

The connection of the Forum of Augustus to the Roman Forum, or the lack thereof, and consequently the location and form of its principal entrance, must have been an important consideration for Augustus while contemplating the plan of his project. The available site was not attached directly to the old civic center. The unfinished Forum of Caesar lay to the southwest, directly between the old Forum and Augustus's site. On the opposite side it was bordered by Subura, a neighborhood of low esteem and frequently consumed by fires. To the southeast was the Argiletum, a road which led to Subura from the old Forum, and across which there was the Macellum, a necessary but not the most dignified element of the urban landscape.Footnote 38 Very little is known about the character of the area to the northwest before it became the Forum of Trajan. In fact, the question of why Augustus did not build his forum further to the northwest, or wider in that direction, is fundamental for the subsequent part of this study.

A possible echo of the predicament can be found in the statement made by Suetonius (Aug. 56.2) that Augustus had to make his forum narrower than originally intended to avoid removing several neighbors from their houses. This statement is commonly associated with the east corner of the forum toward the Subura, where there is an obvious irregularity in the plan, but, in light of the present investigation, a different, much larger area toward the northwest can be contemplated as a potential candidate for the first emperor's consideration. The problem with the purchase of the parcel would have been significantly more consequential for the project than the small cutout at the end of the southeast portico of the forum. On the other hand, if Suetonius's quote did in fact apply to the area of the future Forum of Trajan, it would mean that at the end of the 1st c. BCE it was residential and did not have any particular civic significance with which the future Forum of Augustus could be related.

Given these conditions, Augustus and his architect might have considered two design alternatives for the project. The first option was to orient the new forum toward the Argiletum, parallel to Caesar's. This way it would have had an independent entrance, probably in the form of an open portico on the southeast end, like the Forum of Caesar. However, it would connect to the old Forum only indirectly, through the Argiletum. The design would elevate the old street to a higher status, creating a more or less continuous colonnade along its northwest side, but it would not offer the desired prestige to Augustus's forum. The second option, ultimately selected by Augustus, was to connect his project to the historic center through the forum of his adoptive father. Undoubtedly, he understood that in this way he would create a greater sense of spatial continuity between the fora of Rome, and between Caesar's legacy and his own. The decision had design consequences, some of which have been described above.

In order to make the principal entrance to the Forum of Augustus come from the Forum of Caesar, the Temple of Mars Ultor had to be placed on the axis perpendicular to that of the Temple of Venus Genetrix, with its back toward the Subura. The portico opposite the temple would be shared between the two fora and would become the connector between them, as discussed above. If my interpretation of the passage from Suetonius is correct, the Forum of Augustus could not be built farther northwest than it was. Therefore, in order to connect the two fora as intended, the Forum of Caesar had to be extended to the southeast, toward the Argiletum.

While the decision about the orientation of the Forum of Augustus fulfilled the essential objectives relative to the internal composition of the first two Imperial fora, it also had major consequences for the disposition of space around the southern corner of Caesar's forum, and on the circulation around the two fora and their entrances, further amplified by the location of the Curia Julia. I argue that the effect on the whole civic center of Rome was, in fact, so significant that it should not be seen just as an outcome of independent projects, but instead as a comprehensive planning effort, a consistent master plan.

It is important to review here what is already known about the entrances to the fora (Fig. 10). The modern reconstructions of the Forum of Caesar during the Augustan period show two staircases from the Clivus Argentarius (stair A and stair B on Figs. 1 and 3), one small door on the opposite side (the future site of the Forum of Trajan),Footnote 39 and a monumental portico on the axis of the temple, facing the Argiletum.Footnote 40 All the major entrances were built by Augustus, as demonstrated above, although the original southeast wing of the portico, as planned by Caesar, most likely would have had a similar form.Footnote 41 The Forum of Augustus is commonly shown with two entrances from the direction of the Subura (behind the Temple of Mars Ultor) and, depending on the reconstruction, three to five door-like openings in the wall separating the two fora, opposite the Temple of Mars Ultor. No entrances are believed to have existed on the side of the Argiletum, where the design was dominated by the two curvilinear walls of the exedras.

Fig. 10. Plan of the Fora of Caesar and Augustus showing the entrances and connections between them, including the portico between them open on both sides. (W. Fuchs.)

If the Forum of Augustus had in fact been designed this way, it would have lacked a ceremonial, dramatic entrance similar to the portico on the axis of the Forum of Caesar. It is difficult to imagine that Augustus would have built the monumental entrance of the latter without thinking about a matching feature for his project. Consequently, and considering the evidence presented above, it is extremely likely that the stretch of the portico between the two fora was designed as an open colonnade or another form that emphasized the visual and physical connection between the spaces, as shown in Figure 10.

The southeast wings of the two fora were aligned with each other along the Argiletum. Their line was extended further southwest by the wall of the Curia Julia. Together, they pressed from the northwest on the space of the old street, particularly at its connection point with the Roman Forum. In Caesar's project, with the original length of the portico, the opening from the old Forum toward the Argiletum would have been very wide, around 32 m (106 RF). After the Augustan redesign it became very narrow (Fig. 6). It was now only around 9.5 m (32 RF), measured between the northwest edge of the Basilica Paulli and the wall of the Curia, or as little as 7 m (17 RF) if one also takes into account the portico of the Curia.Footnote 42 The road was quite pinched between the two structures. Nevertheless, it still provided the only access from the old Forum to the southeast portico of the Forum of Caesar, the main entrance to the complex.

The history of the Basilica Paulli includes an interesting event that I believe pertains to the present analysis. The structure was rebuilt in 54 BCE and then again in 34 BCE, when it was made shorter by 5 m on its northwest end.Footnote 43 In light of the present study, it becomes likely that the design change was requested by Augustus relative to the planned new length of the Forum of Caesar and the location of the Curia Julia. Without it, the passageway from the old Forum to the Argiletum would have almost ceased to exist (Fig. 6). Consequently, we must assume that Augustus had ideas for the area before 34 BCE, as discussed above. On the other hand, he had to negotiate necessary changes to the Basilica Paulli with its patron before he could commit completely to the final shape of his project.

While the entrance to the Argiletum from the old Forum had been reduced to a narrow passage, at the same time a lot of space opened up between the Forum of Caesar and the old Forum northwest of the Curia, toward the Clivus Argentarius. This space was a central location: next to the new Senate House, open toward the northern section of the old Forum with its temples of Concord and Saturn, and directly opposite the descent from the Capitoline Hill along the Clivus Capitolinus. The width of the space northwest of the Curia Julia toward the old Forum, before the steep ascent of the Clivus Argentarius, was also very significant compared to the opening of the Argiletum, at around 30 m.

The area had not been empty before. It was the location of the Curia Hostilia and the Curia Cornelia, and since 46 BCE the enigmatic Temple of Fortuna. It also occupied the north quadrant of the Comitium. It was a site of great significance for Rome and its history. It is easy to imagine that, if the Forum of Caesar had not been extended, it would have been considered for the location for the new curia, as discussed above. Although the function and design of the area during the Imperial period have been interpreted differently in the past by scholars, I argue that this was in fact the Chalcidicum of which Augustus speaks in the Res Gestae, which also served as the principal entrance to the two new Imperial fora. Besides its history, size, and location, the site had a huge advantage for Augustus: it was on the axis of his forum and the Temple of Mars Ultor.

In order to understand the context and reasons for Augustus's design for the site, it is necessary to follow step by step the dynamic development of the entire north corner of the Roman Forum between ca. 54 and 29 BCE.

Urban development of the northern section of the Forum, and its relationship with the Fora of Caesar and Augustus