Introduction

In March 2016, Argentine and then international media, including British sources such as Sky News and The Guardian, were reporting something that on the face of it seemed quite extraordinary (for example, Buenos Aires Herald 2016, The Guardian 2016, New York Times 2016, Sky News 2016). Under their headline of ‘Argentina celebrates UN Falklands decision’, Sky News quoted Argentine Foreign Minister, Susan Malcorra, as saying, ‘This is a historic occasion for Argentina because we've made a huge leap in the demarcation of the exterior limit of our continental shelf. This reaffirms our sovereignty rights over the resources of our continental shelf’ (Sky News 2016). It should be noted that the reported quote itself makes no mention of either the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) and/or Antarctica. The source of the story was a press release by a UN body, the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), which reported on the outcome of a recent meeting held by this specialist body of experts regarding coastal state submissions and their ‘claims’ to extended continental shelves.

The CLCS press release, dated 28 March 2016, outlined in brief the achievements of the commission in its 40th session. It noted:

At the plenary level, the Commission adopted, without a vote, two sets of recommendations, namely the recommendations in respect to the submission made by Argentina . . . With regard to the recommendations in respect of the submission made by Argentina, it is recalled that, previously, the Commission had already decided that it was not in a position to consider and qualify those parts of the submission that were subject to dispute and those parts that were related to the continental shelf appurtenant to Antarctica (UN CLCS 2016).

The caveat offered up by the CLCS press release was crucial but one that was either missed and/or simply not understood by the vast majority of news commentators and political journalists who assumed that Argentina was about to be the beneficiary of a huge expansion in marine/resource interests in the South Atlantic region. Hardly surprising, one might note, given the public reaction of the Argentine government. While the Argentine Foreign Minister was right to talk about ‘sovereign rights’ over the continental shelf, the CLCS press release offered up a cautionary note to anybody who thought Argentina gained ‘sovereignty’ over the Falklands and surrounding waters.

This note briefly reviews the work of the UN CLCS and the links to sovereign rights over the continental shelf. It is crucial that the commission's scope is understood because far too many journalists in particular fail to understand some of its fundamental qualities such as it being a scientific-technical body of experts. The commission does not enjoy a legal personality and it issues what are termed ‘recommendations’ rather than rulings on the outer limits of continental shelves. Thereafter, the maritime dimension of the South Atlantic/Antarctic region is considered with reference to the 2009 submission by Argentina to the CLCS. Finally, and briefly, the note concludes with an assessment of why that CLCS press release in March 2016 and the words ‘not in a position to consider and qualify those parts of the submission that were subject to dispute and those parts that were related to the continental shelf appurtenant to Antarctica’ matters a great deal with regard to the wider region.

The Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf

The UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf owes its existence to the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS). Under article 2 of annex II of UNCLOS, it is noted that, ‘the Commission shall consist of twenty-one members who shall be experts in the field of geology, geophysics or hydrography, elected by States Parties to the Convention from among their nationals, having due regard to the need to ensure equitable geographical representation, who shall serve in their personal capacities’. Serving five years at a time, the current members are in office until June 2017. Meeting in New York, the Commission consider submissions from coastal states that are party to UNCLOS (and thus excluding non-party countries such as the United States) and who under article 76 are intent on establishing the outer limits of continental shelves. Article 76 sets out the criteria by which coastal state can define extended continental shelves and article 77 notes that coastal states enjoy ‘sovereign rights [over the continental shelf] for the purpose of exploring it and exploiting its natural resources’. The water-column over the continental shelf, up to 200 nautical miles, is part of the Exclusive Economic Zone of coastal states (for a detailed overview see Oude Elferink and others Reference Oude Elferink, Rothwell, Stephens and Scott2015).

Interest in the submission process regarding the outer limits of the continental shelf was marginal until the first submission to the CLCS in 2001 by the Russian Federation. Having ratified UNCLOS in 1997, Russia submitted its scientific and technical materials to the CLCS and requested a ‘recommendation’ on its claims to define its extended continental shelves in the Arctic and Pacific Oceans. Under the terms of the UNCLOS ratification, coastal states have ten years to make such submissions to the CLCS after becoming a party, and the CLCS then has to review and assess any such ‘claims’ by coastal states to the precise definition of the outer limits of extended continental shelves (ECS). It is an expensive and technical business. The criteria for claiming an ECS are based on geological and geographical criteria including distance, thickness of sedimentary rock and water depth. In practice, the ECS can extend up to 350 nautical miles from the baseline and possibly even further depending on the criteria concerned. Coastal states are allowed to use a mixture of criteria stated in article 76 in determining outer limits but it was recognised that the outer limits of the continental shelf of one coastal state might overlap with another. As a consequence, the CLCS issues ‘recommendations’ and any final delimitation of ECS will, in many cases, depend upon bilateral even trilateral negotiation with other coastal states under article 83 regarding overlapping entitlements. Under article 76 (8), however, it is worth noting that, ‘The Commission shall make recommendations to coastal States on matters related to the establishment of the outer limits of their continental shelf. The limits of the shelf established by a coastal State on the basis of these recommendations shall be final and binding’. So recommendations are legally important but they will be without prejudice to the delimitation of overlapping entitlements.

In short, there is no quick fix to the business of delimiting the ECS, especially where there is more than one party involved. A good case in point is the central Arctic Ocean where the Russian submission in 2001 was queried by the CLCS and the Russian authorities were requested to submit further materials regarding the determination of the outer limits of the continental shelf. In the intervening years, Denmark and Canada have also undertaken their own ECS investigations and the likely outcome is the CLCS will be making three ‘recommendations’ to the interested parties, and that they will have to negotiate the final delimitation of the outer limits of their respective continental shelves, as noted in article 83. The 2008 Ilulissat Declaration between the five Arctic Ocean coastal states reaffirmed their collective commitment to respect the provisions of the ‘law of the sea’ and to resolve any differences in an orderly manner pursuant in the case of Canada, Denmark and Russia to UNCLOS specifically (Oude Elferink Reference Oude Elferink2008; Koivurova Reference Koivurova, Gudmundur and Koivurova2009; Dodds Reference Dodds2010).

The delimitation of the ECS is also significant in the sense that the areas beyond the ECS form part of ‘The Area’ and thus fall under the jurisdiction of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) as far as mining is concerned. The area effectively starts from where the coastal state continental shelf ends. Geographically it is the most distant from the coastline and part of the seabed, which is managed by the ISA on behalf of the international community. ‘The Area’ is a common heritage of mankind. It has relevance to the Antarctic because if there are no internationally recognised coastal states (as opposed to the seven claimants including Argentina, Chile and the UK) then the waters off the polar continent are high seas. While the water column, seabed and subsoil south of 60° S is covered by the Madrid Protocol to the Antarctic Treaty (and thus included in the prohibition on mining under article 7), it is possible to imagine UNCLOS providing a framework for the ISA to manage seabed mining off the coast of Antarctica in the future.

Argentina and the 2009 submission to the CLCS

In accordance with article 76 paragraph 8, Argentina submitted materials to the CLCS in April 2009 to be considered at the next meeting of the CLCS in June of that year. The submission itself was unusual and rather more expansive than international observers would have expected. Unlike other claimant states such as New Zealand and the UK, Argentina selected not to make what is termed a ‘partial submission’ or a full submission with a caveat of selective non-consideration. Australia, by way of contrast to the UK for example, made a full submission including the AAT, but asked the CLCS not to consider the part of its submission dealing with the AAT (Oude Elferink Reference Oude Elferink, Molenaar, Oude Elferink and Rothwell2013). In this context, the coastal state might choose to submit materials to the CLCS regarding the ECS and deliberately abjure certain areas from consideration and/or ask the CLCS not to consider for the moment particular areas such as continental shelf appurtenant to Antarctica. In 2012, Australia made the Seas and Submerged Lands (Limits of the Continental Shelf) Proclamation 2012, defining the outer limits of the country's continental shelf. The accompanying figure (Fig. 1) outlines the scale and extent of that definition and purposefully excludes Australian Antarctic Territory, mindful of article 4 of the Antarctic Treaty. Notably, the areas in question do extend into the Antarctic Treaty area via the Australian sub-Antarctic islands of Heard, McDonald and Macquarie. Australian commentators reasoned that the islands themselves lay outside the Antarctic Treaty area of application and that coastal states such as Australia enjoyed sovereign rights rather than full sovereignty over any extended continental shelf lying within the area of application. As one Australian commentator noted in 2012, ‘In a well-orchestrated move, Australia requested the CLCS to not examine for the time being the Antarctic data. The diplomatic responses from some Antarctic Treaty Parties reflected the discussions among Antarctic Treaty parties in the lead up to Australia's submission’ (Press Reference Press2012).

Fig. 1. Australia and the outer limits of its extended continental shelf.

Other commentators such as Hemmings and Stephens (Reference Hemmings and Stephens2010) warn that the rights of coastal states in the Antarctic Treaty Area (ATA) are troubling because of the delicate balance achieved under article 4 of the Antarctic Treaty regarding claim abeyance. Beyond the treaty itself, there is widespread non-recognition of the seven claimants. Australia, along with others such as the UK, recognises that their capacity to act is substantially greater in the sub-Antarctic region, which lies to the north of the ATA. The authors also warn that coastal states such as Australia, while respectful of the mining ban as stipulated in the Protocol on Environmental Protection, might choose to exploit genetic resources on the extended continental shelves of sub-Antarctic territories, which protrude into ATA. The ECS of the islands of Heard and MacDonald extends south of 60’ S. Argentina's position is very different to Australia, however. The sub-Antarctic territories of concern to the Argentine Republic are disputed and are under the de facto jurisdiction of the United Kingdom, namely South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands and further north the Falkland Islands. In May 2009, the UK submitted materials to the CLCS in regard to the extended continental shelves of those South Atlantic territories.

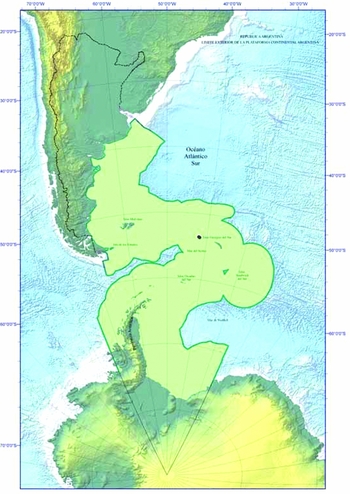

The executive summary of the Argentine submission was bullish in its content and intent, noting for example that, ‘As a coastal State, Argentina was one of the first countries to underscore the extent of its sovereignty rights over the continental shelf. In 1916 – before the Truman Proclamation – Admiral Storni developed a doctrine favouring the recognition of the rights over the continental shelf and all of the resources therein’ (Argentina 2009). Further into the submission the document reiterates the relevant transitional provision of the 1994 Constitution declaring that, ‘The Argentine Nation ratifies its legitimate and imprescriptible sovereignty over the Islas Malvinas, Georgias del Sur and Sandwich del Sur and the corresponding island and maritime areas they are an integral part of the national territory’. And finally, the Argentine Antarctic sector is noted as, ‘South of the Scotia Sea, Argentina selected both formulae. Argentina selected 8 Foot of Slope (FOS) points in this area of its continental margin. From FOS-50, located on the ARG-300 line in the central sector of the Scotia Sea, to the north of the Islas Orcadas del Sur up to FOS-57, on the ARG-355 line in the Weddell Sea, to the south of the abovementioned islands. From the FOS points thus selected, Argentina generated the 60 M arcs and the corresponding envelope. The 1 per cent formula on a total of 5 fixed points was also used’. Within the 28 page executive summary there are eight maps outlining the full submission made by the Argentine Republic to a substantial ECS encapsulating the South Atlantic, the Antarctic Peninsula, and other areas of the Southern Ocean of interest to its neighbour, Chile. For Chilean observers, the submission and in particular maps (see Fig. 2) represent a strong challenge to Chile's strategic and geopolitical ambitions regarding the area south of Cape Horn and the Chilean Antarctic Territory.

Fig. 2. Argentina and the proposed outer limits of its extended continental shelf.

While the submission by Argentina was not the first to include materials pertaining to the ATA (Australia was the first claimant state to do that), it was the first to ask explicitly that the commission examine the materials pertaining to Argentine Antarctic Territory. After publication of the executive summary, there were a series of responses to the 2009 submission by claimant and non-claimant states alike including Russia, India and the United States. The Netherlands, as it had done for the Australian submission, drew attention to the ‘unresolved land dispute in relation to Argentina's claim to territory in Antarctica’ and rejected all claims to sovereign rights over the ‘continental shelf adjacent to Antarctica (Netherlands 2009). The United Kingdom protested at the nature of the Argentine submission and the two parties exchanged notes on the subject in 2009 and again in 2012. The latest British note, dated August 2012, formally requested the CLCS ‘not to consider those parts of Argentina's submission that relate to areas appurtenant to the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands (as detailed in its note of 6 August 2009), or which relates to areas appurtenant to Antarctica’ (United Kingdom 2012).

Argentina, the Falklands and the continental shelf

Nearly four years after the UK note to the commission, representatives of the Argentine government including Foreign Minister Susana Malcorra, made an official presentation regarding the extended continental shelf. It was noted in the presentation itself that Argentina's continental shelf had been extended by an ‘additional 1.7 million square km of continental shelf to its current 4.8 million square km’ (Mercopress 2016). As Mercopress reported at the time, ‘Not a word was mentioned by Minister Malcorra in her video regarding the Falklands/Malvinas and South Atlantic Islands dispute’. Given this caveat, and the press release from the CLCS, it is intriguing how so many media sources were able to frame the announcement as being indicative of a worsening of the UK-Argentine dispute over the Falklands and the South Atlantic. As has been noted elsewhere, there is no shortage of issues which add ‘fuel’ to the continuing disagreements between the two countries over the South Atlantic and Antarctic and this is another area of what we might think of ‘blatant’ rather than ‘banal’ nationalism (for example, Dodds and Benwell Reference Dodds and Benwell2010; Benwell and Dodds Reference Benwell and Dodds2011; Dodds and Hemmings Reference Dodds and Hemmings2014; Benwell Reference Benwell2014). It also serves as a powerful reminder of how geo-legal formulae perpetuate state-making projects designed to improve, expand and consolidate volumetric territories, with height, depth and breadth all being critical factors in the calculation strategies of relevant authorities (Elden Reference Elden2013).

The Argentine Foreign Minister's reported comments might well have alarmed British and Falkland Island observers when she noted, ‘The demarcation of the exterior limit of the continental shelf constitutes a clear example of a State policy in which Argentina has worked professionally during twenty years with the purpose of reaffirming our presence, conservation of our resources and reaffirming our sovereignty rights over a zone politically, economically and strategically so important in the South Atlantic’ (Mercopress 2016). And this alongside Argentine tweeting on the issue provoked Falkland Islander, Lisa Watson, editor of the Penguin News, to write in the Daily Telegraph that, ‘The thing is, the Argentine people really do live in a stalker-like fantasy land when it comes to the Falkland Islands – and the Argentine government encourages them to. In fact it rules that they do so. The pursuit of sovereignty over the Falklands is confirmed in their constitution. It's the only thing that the country, long divided by political factionalism and social strife, can agree on’ (Watson Reference Watson2016).

For British and Falkland Island observers, there is an important take-home point, however. The UN CLCS endorsed the scientific and technical details contained within the Argentine submission but only in relation to the continental shelf of Argentina's mainland. Politically, the CLCS avoided controversy (as expected by people who understand the role of the commission) by declining to consider areas that are currently in dispute, including the South Atlantic islands and the special case of the Antarctic Treaty Area. Longer-term, there is a warning here that Argentina even with a change of government continues to take seriously the transitional provisions of its 1994 Constitution. While most media reporting exaggerated or misread the significance of the Argentine announcement regarding its extended continental shelf, those same articles were indirectly right in highlighting the significance of a little known UN body and its ‘recommendations’. Argentine observers, on the whole, will be heartened by the confirmation of the country's sovereign rights to the ECS to a vast area of the South Atlantic region.

For Argentine geopolitical observers, the news regarding the continental shelf while it excludes the disputed islands of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia, it will provide nourishment to the view that Argentina's sovereign rights over the South Atlantic seabed will further the national project of a genuinely tri-continental nation (Child Reference Child2009).

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Alex Oude Elferink and Timo Koivurova for their comments on an earlier version. The usual disclaimers apply, however.