Introduction

Cystoisospora belli is a coccidian parasite of humans. Originally named by Wenyon (Reference Wenyon1923) as Isospora belli for its bell-shaped oocysts; it was transferred to the genus Cystoisospora (Barta et al., Reference Barta, Schrenzel, Carreno and Rideout2005). The parasite is specific to humans and attempts to infect non-human primates, livestock, rodents and other animals with C. belli were unsuccessful (Jeffery, Reference Jeffery1956). Experimental infections in human volunteers and in laboratory acquired infections revealed that it has a direct fecal–oral transmission cycle and can cause serious illness in humans (Matsubayashi and Nozawa, Reference Matsubayashi and Nozawa1948; Jeffery, Reference Jeffery1956; Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Coutinho, Argento and da Silva1962; Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Gillepsie, Kaplan and Steber1963). The prepatent period (first day of oocyst excretion in feces) is 9–17 days. Hundreds of cases of intestinal infections have been reported in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised humans (Faust et al., Reference Faust, Giraldo, Caicedo and Bonfante1961; Jarpa Gana, Reference Jarpa Gana1966; Legua and Seas, Reference Legua and Seas2013). In addition to enteritis, C. belli can cause infections of the biliary tract and gallbladder (Benator et al., Reference Benator, French, Beaudet, Levy and Orenstein1994; Agholi et al., Reference Agholi, Aliabadi and Hatam2016).

Fragmentary information on endogenous stages was obtained by examination of human biopsy tissues from small intestine (Niedmann, Reference Niedmann1963; Brandborg et al., Reference Brandborg, Goldberg and Breidenbach1970; Henry et al., Reference Henry, Bird and Doe1974; Trier et al., Reference Trier, Moxey, Schimmel and Robles1974; Liebman et al., Reference Liebman, Thaler, DeLorimier, Brandborg and Goodman1980; Veldhuyzen van Zanten et al., Reference Veldhuyzen van Zanten, Lange, Sauerwein, Rijpstra, Laarman, Rietra and Danner1984; Modigliani et al., Reference Modigliani, Bories, LeCharpentier, Salmeron, Messing, Galian, Rambaud, Lavergne, Cochand-Priollet and Desportes1985; Restrepo et al., Reference Restrepo, Macher and Radany1987; Peng and Tsai, Reference Peng and Tsai1991; Benator et al., Reference Benator, French, Beaudet, Levy and Orenstein1994; Comin and Santucci, Reference Comin and Santucci1994; Michiels et al., Reference Michiels, Hofman, Bernard, Saint Paul, Boissy, Mondain, Lefichoux and Loubiere1994; Hamour et al., Reference Hamour, Curry, Ridge, Baily, Wilson and Mandal1997; Bialek et al., Reference Bialek, Overkamp, Rettig and Knobloch2001; Field, Reference Field2002; Jongwutiwes et al., Reference Jongwutiwes, Sampatanukul and Putaporntip2002; Sasaki et al., Reference Sasaki, Tanaka, Nishimura, Tsujikawa, Andoh, Ishizuka, Koyama, Fujiyama and Kushima2004; Walther and Topazian, Reference Walther and Topazian2009; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Hoogestraat, Sengupta, Prentice, Chakrapani and Cookson2011; Rao et al., Reference Rao, Geetha, Ranjini, Vidhyalakshmi and Rupashree2012; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kim, Jung, Chai and Chai2013; Agholi et al., Reference Agholi, Aliabadi and Hatam2016; Lai et al., Reference Lai, Goyne, Hernandez-Gonzalo, Miller, Tuohy, Procop, Lamps and Patil2016; Martelli and Lee, Reference Martelli and Lee2016; Swanson et al., Reference Swanson, March, Clayton, Couturier, Arcega, Smith and Evason2018), bile ducts or gallbladder (Benator et al., Reference Benator, French, Beaudet, Levy and Orenstein1994; Lagrange-Xélot et al., Reference Lagrange-Xélot, Porcher, Sarfati, de Castro, Carel, Magnier, Delcey and Molina2008; Walther and Topazian, Reference Walther and Topazian2009; Agholi et al., Reference Agholi, Aliabadi and Hatam2016; Martelli and Lee, Reference Martelli and Lee2016). Meronts, microgamonts, macrogamonts and unsporulated oocysts were seen in enterocytes of small intestine and in biliary epithelium. Histopathologic examination of tissues obtained post-mortem confirmed that asexual and sexual stages of C. belli are confined to the intestines, bile ducts and gallbladder epithelium (Brandborg et al., Reference Brandborg, Goldberg and Breidenbach1970; Restrepo et al., Reference Restrepo, Macher and Radany1987; Benator et al., Reference Benator, French, Beaudet, Levy and Orenstein1994; Michiels et al., Reference Michiels, Hofman, Bernard, Saint Paul, Boissy, Mondain, Lefichoux and Loubiere1994; Frenkel et al., Reference Frenkel, de Oliveira Silva, Saldanha, de Silva, Correia Filho, Barata, Lages, Ramirez and Prata2003). Restrepo et al. (Reference Restrepo, Macher and Radany1987) mentioned finding of schizonts and gamonts also in large intestine but did not provide any details. Additionally, monozoic tissue cysts (thought to be encysted sporozoites) were found in the lamina propria of small and large intestine, lymph nodes, spleen and liver of immunosuppressed patients (Restrepo et al., Reference Restrepo, Macher and Radany1987; Comin and Santucci, Reference Comin and Santucci1994; Michiels et al., Reference Michiels, Hofman, Bernard, Saint Paul, Boissy, Mondain, Lefichoux and Loubiere1994; Lindsay et al., Reference Lindsay, Dubey, Toivio-Kinnucan, Michiels and Blagburn1997; Velásquez et al., Reference Velásquez, Carnevale, Mariano, Kuo, Caballero, Chertcoff, Ibáñez and Bozzini2001, Reference Velásquez, Osvaldo, Di Risio, Etchart, Chertcoff, Perissé and Carnevale2011; Frenkel et al., Reference Frenkel, de Oliveira Silva, Saldanha, de Silva, Correia Filho, Barata, Lages, Ramirez and Prata2003; Meamar et al., Reference Meamar, Rezaian, Zahabium, Faghihi, Oormazdi and Kia2009; Swanson et al., Reference Swanson, March, Clayton, Couturier, Arcega, Smith and Evason2018). Parasitaemia has been reported in one patient (Velásquez et al., Reference Velásquez, di Risio, Etchart, Chertcoff, Nigro, Pantano, Ledesma, Vittar and Carnevale2016). After a review of findings in these reports, it became evident that details of the development of C. belli stages are lacking.

The diagnosis of C. belli can be made by fecal examination for its characteristic 20–37 µm long bell-shaped oocysts, and by histological and molecular examination of biopsy specimens. Fecal examination is the simplest but can be problematic, because the oocysts are excreted intermittently, often in small numbers, and can be absent during acute infection. Histological examination of biopsy of small intestine, bile duct and gallbladder can confirm diagnosis depending on the size of the tissue sample and the density of parasites. However, bile is a cytolytic agent (Tatum, Reference Tatum1916), which can lead to gallbladder epithelial inclusions mimicking C. belli schizonts and gamonts (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Goyne, Hernandez-Gonzalo, Miller, Tuohy, Procop, Lamps and Patil2016; Martelli and Lee, Reference Martelli and Lee2016; Akateh et al., Reference Akateh, Arnold, Benissan-Messan, Michaels and Black2018) and potential misdiagnosis of infection (Swanson et al., Reference Swanson, March, Clayton, Couturier, Arcega, Smith and Evason2018).

The objective of the current paper is to describe development of C. belli in intestine and biliary tract of two patients. The detailed description of the life cycle stages of C. belli reported here should facilitate in histopathologic diagnosis of this parasite.

Materials and methods

Case 1 (common bile duct)

Biopsy specimens of the common bile duct from the 42-year-old patient reported by Walther and Topazian (Reference Walther and Topazian2009) were studied here. Three 3 × 1 mm biopsy fragments were embedded in a paraffin block and multiple sections were mounted on a total of nine histological slides; the block was subsequently exhausted for molecular studies, with no tissue remaining. Nine sections were examined microscopically for parasite stages after staining with haematoxylin and eosin (HE). Retrospectively, one slide stained with HE was re-stained with periodic acid Schiff reaction (PAS), counter stained with haematoxylin (PASH).

Case 2 (duodenum)

Five 2–3 × 1 mm pieces of duodenal biopsy from a 23-year-old patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and diarrhoea (Swanson et al., Reference Swanson, March, Clayton, Couturier, Arcega, Smith and Evason2018) were embedded in a paraffin block. Seven sections from this block were studied for the present investigation. The sections were stained with HE, PASH or trichrome stain.

All host tissue from both cases was examined by one of us (J.P.D.) at 1000× magnification in an Olympus AX 70 microscope and stages photographed using a DP73 camera.

Results

In both cases, asexual and sexual stages of C. belli were present mainly in epithelial cells of surface epithelium and rarely in crypt epithelial cells. The parasites were located above or below the host cell nucleus and the host cell nucleus was indented but not hypertrophied. All stages were in host cytoplasm within a parasitophorous vacuole (pv).

To avoid confusion and to document variability in PAS staining characteristics, both cases are described separately below.

Case 1 (common bile duct)

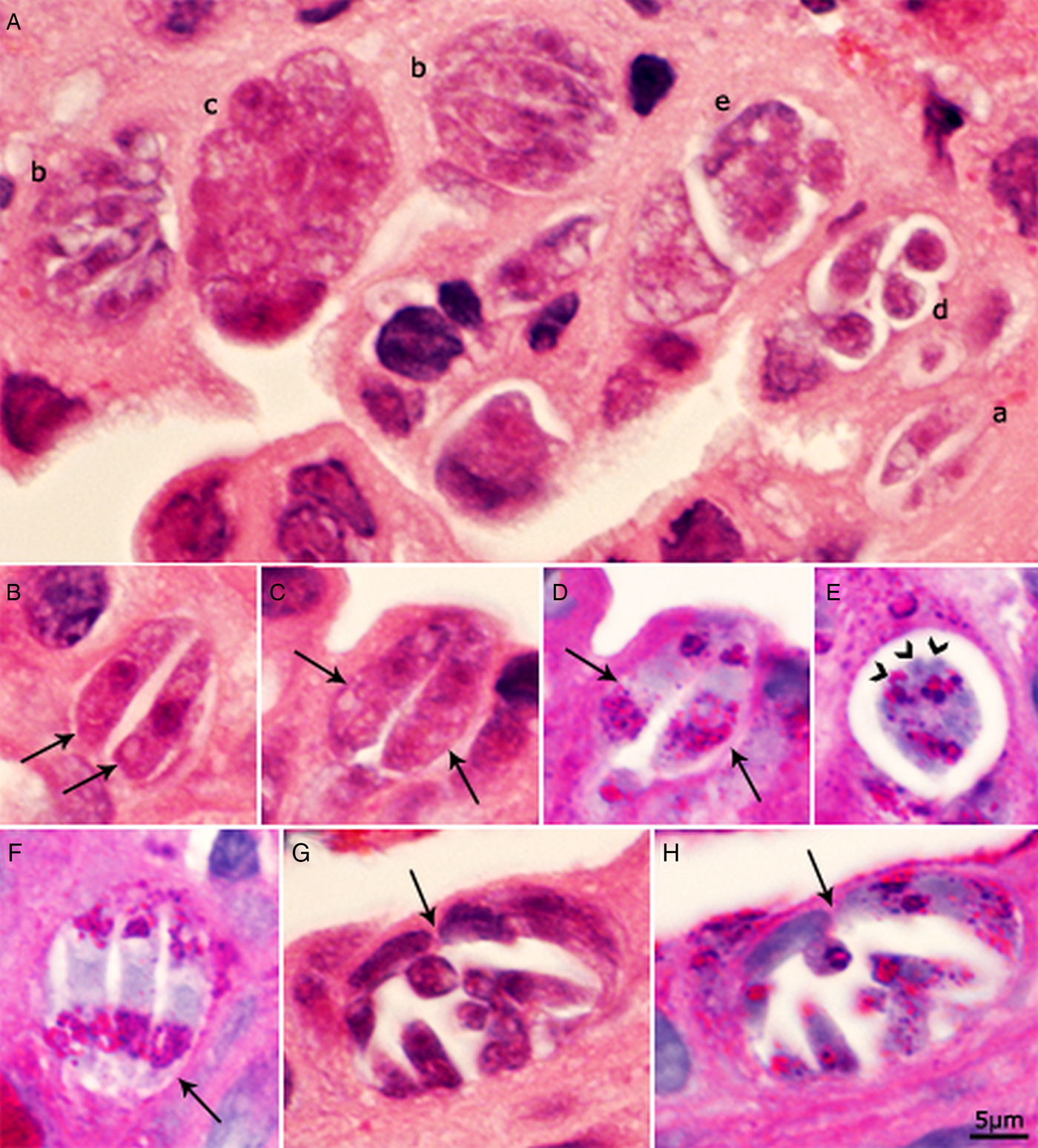

The density of parasites varied; in some microscopic fields, many parasites were seen (Fig. 1A) while most had only a few organisms. Some infected host cells were bulging into the lumen. Both immature and mature meronts were recognized. Immature meronts were elongated to pear-shaped. Meronts were up to 25 × 18 µm and contained up to ten merozoites. Merozoites were present singly, in pairs and in groups (Fig. 1). Merozoites were approximately 8–12 × 2–4 µm. In HE-stained sections, individual merozoites were elongated with a pointed (conoidal) end, a central nucleus, had a few lightly stained areas, and measured 10–11 × 3 µm (Fig. 1A). Figure 1C shows a meront containing two merozoite-like structures that are 11 × 4 µm. The nuclei in larger meronts were not well defined. Merozoites and meronts contained PAS-positive granules; the intensity of staining varied. In most merozoites, PAS-positive granules were concentrated at the polar ends of merozoites (Fig. 1D and F).

Fig. 1. Asexual stages of C. belli in histological sections of bile duct of a patient. Bar applies to all parts. A, B, C and G = HE stain; D, E, F and H = PAS counter stained with haematoxylin. The luminal side of sections is on the top. (A) Several meronts in one microscopic field. (a) Paired merozoites in one pv. (b) Meront with four or more merozoites completely filling the pv. (c) Meront containing developing merozoites. The organisms are cut in cross-section; the nuclei appear larger than in merozoites. (d) Four merozoites in a pv with spaces between merozoites. (e) Immature meront. (B) Paired crescent-shaped merozoites. (C, D) The same paired organisms/meronts after staining with HE (C) and PAS (D). Note the polar PAS-positivity. The parasite nuclei are masked by PAS staining. (E) Meront with merozoites budding (arrowheads). Note PAS-positivity. (F) Meront (arrow) with three merozoites with polar PAS-positivity. (G, H) The same mature meront (arrow) after staining with HE (G) and PASH (H).

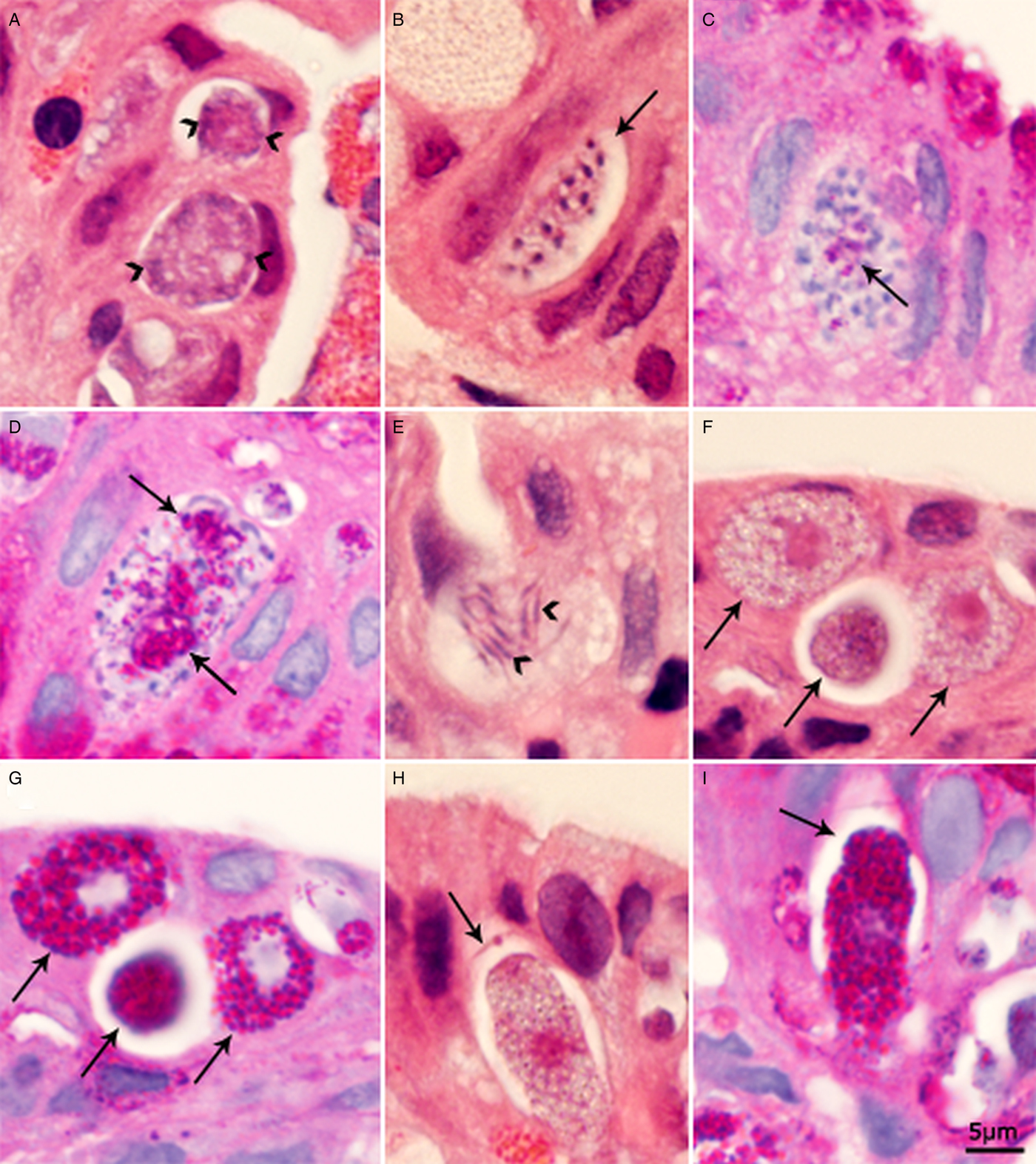

Microgamonts were rounded, oval or elongated (Fig. 2A–D). The earliest microgamont was about 6 µm in diameter and contained four nuclei. With maturation of the microgamonts, the nuclei moved peripherally and a small PAS-positive residual body was visible. Figure 2C shows a microgamont with 30 nuclei and a very small PAS-positive body. Figure 2D shows an 18 × 10 µm microgamont with at least 16 nuclei and three PAS-positive residual bodies. Microgametes were about 4 µm long (Fig. 2E) and PAS-negative.

Fig. 2. Sexual stages of C. belli in histological sections of biliary epithelium. Bar applies to all parts. A, B, E, F and H = HE stain; C, D, G and I = PAS counter stained with haematoxylin. (A) Two multinucleated microgamonts with peripheral nuclei (arrowheads); the nuclear structure is not clear. (B) An elongated microgamont (arrow) with several peripheral nuclei with condensed chromatin. (C) A microgamont with many nuclei and a small PAS-positive body. (D) A microgamont with two large residual bodies (arrows) and several microgametes. (E) Microgametes (arrowheads). (F, G) The three same young macrogamonts (arrows) after staining with HE (F) and PASH (G). Note, intensely stained PAS-positive granules in cytoplasm that do not stain with HE. (H, I) Same macrogamont with oocyst wall (arrow) after staining with HE (H) and after staining with PASH (I). The gamont is intensely PAS-positive.

Macrogamonts could be distinguished from meronts and microgamonts by the presence of a single nucleus with a large nucleolus. In sections stained with HE, dusting of granules was seen but wall forming bodies (WFB) were not recognized. The earliest macrogamonts were about 6 µm in diameter (Fig. 2F and G). All macrogamonts were intensely PAS-positive (Fig. 2G). As the macrogamonts matured, they became elongated. Only a few oocysts were seen and they contained an intensely PAS-positive sporont and a very thin oocyst wall (Fig. 2H and I).

Case 2 (duodenum)

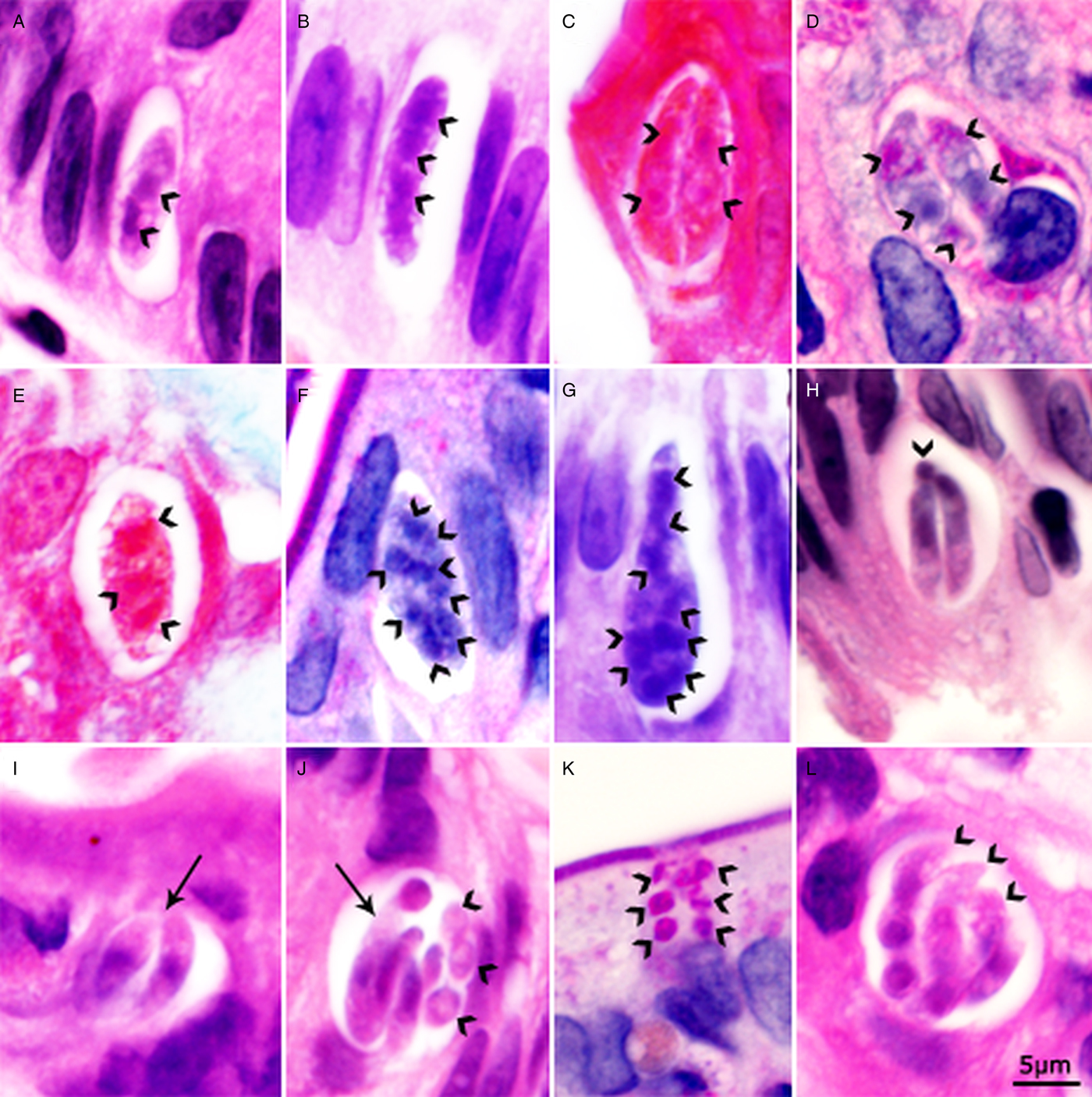

The youngest meronts were crescent-shaped, 11–15 × 3–4 µm and contained two to four nuclei; their ends were either round or pointed (Fig. 3A and B). In more advanced meronts up to eight nuclei were recognized (Fig. 3E–G). Figure 3G shows an elongated 20 × 6 µm meront with a pointed conical end and a distal rounded end; it appears to have more than eight indistinct nuclei. The pointed end is stained differently than the rest of the meront. Figure 3F shows a 15 × 6 µm meront with eight nuclei. Figure 3C and D shows meronts with paired developing crescent-shaped structures. Figure 3J shows a meront containing both mature merozoites and in division. Individual merozoites containing single nucleus were 8–11 × 2–3 µm (Fig. 3H–J). There was no residual body in meronts; sometimes merozoite in cross-section appeared like a residual body (Fig. 3H).

Fig. 3. Asexual stages of C. belli in histological sections of duodenum of a patient. Bar applies to all parts. A, B, G, H, I, J and L = HE stain; C and E = trichrome stain; D, F and K = PAS counter stained with haematoxylin. The luminal side of sections is on the top. (A) Elongated meront with dividing nucleus (arrowheads). (B) Elongated meront with three nuclei (arrowheads). Note both end of the meront are rounded. (C). A pv containing paired crescent-shaped meronts. Note large nuclei (arrowheads). (D) A pv containing paired crescent-shaped meronts. Note large nuclei (arrowheads). (E) Meront with three or more nuclei (arrowheads). (F) Meront with eight nuclei (arrowheads). (G) An elongated meront with a conical (conoidal) and a rounded non-conoidal end. There are more than eight nuclei (arrowheads). (H) A pv containing two slender merozoites and one merozoite in cross-section (arrowhead). (I) A pv with two merozoites that are thicker than merozoites in 1H (arrow). (J) A pv containing an undivided meront (arrow) and five or more merozoites (arrowheads). (K) A pv with six merozoites in cross-section (arrowheads). Note PAS positivity. (L) Mature meront with merozoites (arrowheads).

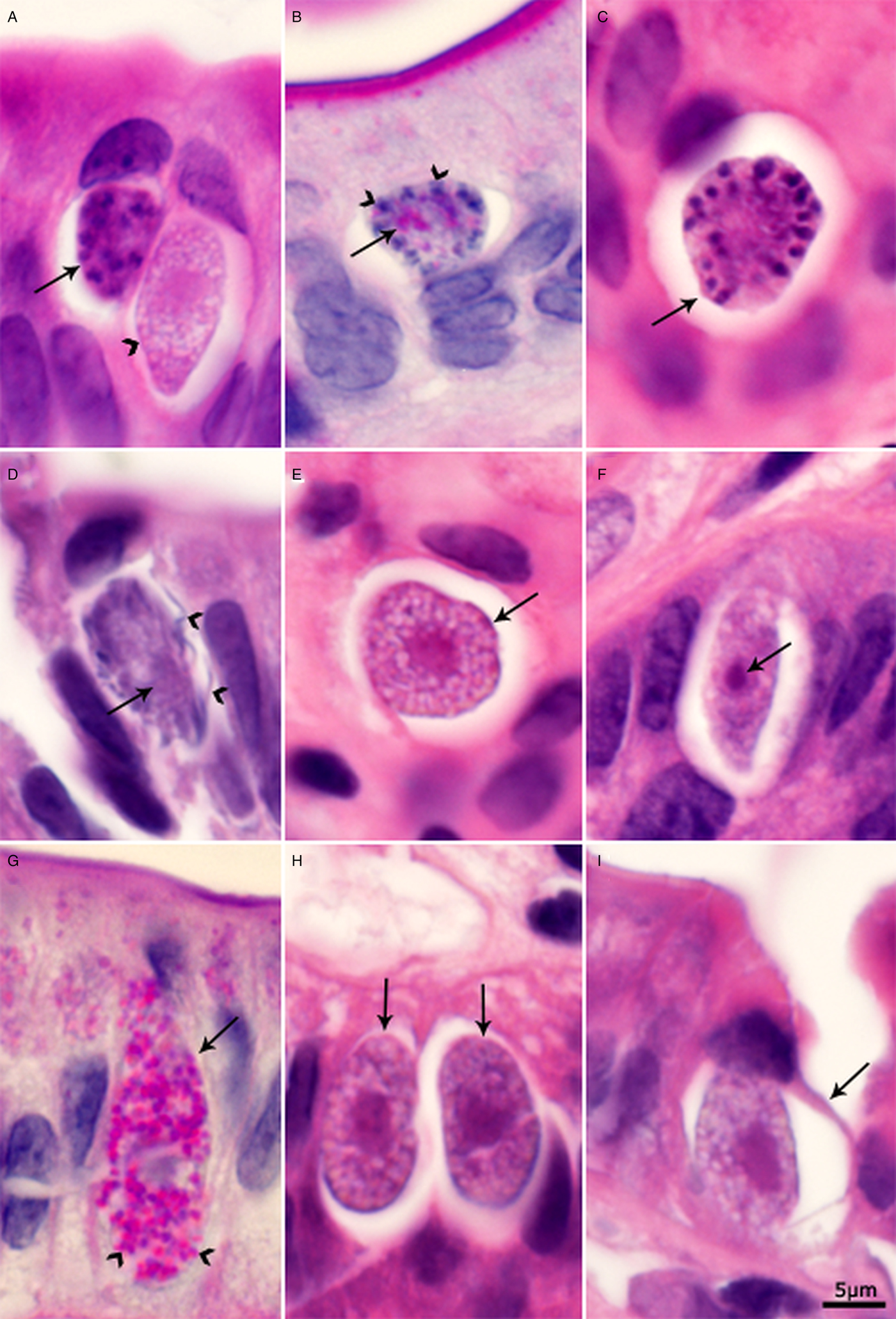

Both immature and mature gamonts were identified. The youngest microgamont was 9 × 8 µm and appeared to have four nuclei. In early microgamonts, the nuclei filled the entire gamont (Fig. 4A). With maturation of the microgamont, the nuclear chromatin condensed, and the nuclei moved to the periphery of the gamont (Fig. 4B and C). A small PAS-positive residual body was first recognized in a 9 × 7 µm microgamont containing 14 peripherally arranged nuclei (Fig. 4B). Mature microgamonts contained one or more large eosinophilic, PAS-positive residual bodies and peripherally arranged 4 µm long PAS-negative microgametes (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4. Sexual stages of C. belli in histological sections of duodenum. Bar applies to all parts. A, C, D, E, F, H, and I = HE stain; B and G = PAS counter stained with haematoxylin. The luminal side of sections is on the top. (A) Multinucleated microgamont (arrow) and an elongated macrogamont with a large nucleus (arrowhead). The conical end of the macrogamont is stained darker than the rest of the gamont. Note small granules in the cytoplasm. (B) A microgamont (arrow) with several peripheral nuclei and a small PAS-positive body. (C) A microgamont (arrow) with peripheral nuclei. (D) A mature microgamont with a large residual body (arrow) and microgametes (arrowheads). (E) A macrogamont in cross-section (arrow). Note many small granules/empty spaces. (F) An elongated macrogamont with a single nucleus and a large nucleolus (arrow). Note, both ends of the gamont are pointed. (G) Elongated macrogamont (arrow) with a large nucleus and many PAS-positive granules (arrowheads). (H) Two macrogamonts with large central nucleus (arrows). (I) Macrogamont with developing oocyst wall (arrow).

All stages of macrogamonts were PAS-positive. Early macrogamonts were round to oval and contained a central single nucleus with a large nucleolus. With maturation, the macrogamonts became elongated with pointed or rounded ends (Fig. 4E–H). In HE-stained sections, the nucleus was eosinophilic with darkly stained area at one end (Fig. 4F). The cytoplasm contained variably stained granules. Mature macrogamonts were up to 21 µm long. Only one oocyst with partial wall was seen (Fig. 4I).

Tissue cysts were seen in the lamina propria of the duodenum. They were approximately 14 × 7 µm and contained an 8 × 4 µm sporozoite. The sporozoites contained a central nucleus and few faintly stained PAS-positive granules. These tissue cysts were structurally like those described previously (Restrepo et al., Reference Restrepo, Macher and Radany1987).

Discussion

In the current study, the development of asexual and sexual stages of C. belli is described and asexual stages were called meronts instead of schizonts. Prior to this description, C. belli was thought to follow the life cycle of Eimeria species of poultry and livestock (Trier et al., Reference Trier, Moxey, Schimmel and Robles1974). In a typical Eimeria life cycle, the asexual stages are called schizonts and the parasite nucleus divides into six or more nuclei before merozoites are formed; in some Eimeria spp. thousands of nuclei are produced before merozoite formation (Levine, Reference Levine1973). Schizogony consists of a series of generations of merozoite formation in different cells that are morphologically different in each generation and occur at different time periods [up to six distinct generations are recognized in some Eimeria species (Levine, Reference Levine1973)]. Dubey and Frenkel (Reference Dubey and Frenkel1972) first proposed the term ‘type’ for intestinal stages of Toxoplasma gondii because there was a profuse asexual multiplication of meront types long after gametogony in feline enterocytes; asexual generations could not be determined. Subsequently, it was found that Isospora (now Cystoisospora) of dogs and cats followed the same pattern as in T. gondii (Dubey, Reference Dubey2018; Dubey and Lindsay, Reference Dubey and Lindsay2019). In Cystoisospora species, the parasites divide by endodyogeny (division into two), by fission, and multiple endodyogeny; typical multinucleated round schizonts are absent. The parasite can have multiple replications without leaving the host cell. Thus, immature meronts occur along with mature merozoites in the same vacuole. These stages were found here in C. belli for the first time. Therefore, the term type is more applicable than the generation/schizont. The term meront also is not specific with respect to division of the parasite; it applies both to the product of endodyogeny or schizogony. Because the ultrastructural details of mode of division of most Cystoisospora spp. are largely unknown, we used the term meront in the current paper.

In the cases studied here, the diagnosis of C. belli had been confirmed previously by polymerase chain reaction (Walther and Topazian, Reference Walther and Topazian2009; Swanson et al., Reference Swanson, March, Clayton, Couturier, Arcega, Smith and Evason2018). In both cases, there was no histologic evidence of Cyclospora cayetanensis, the other coccidian found in enterocytes of humans (Ortega et al., Reference Ortega, Nagle, Gilman, Watanabe, Miyagui, Quispe, Kanagusuku, Roxas and Sterling1997). Compared with C. belli, the oocysts of C. cayetanensis are tiny (8–10 µm). Endogenous stages of C. cayetanensis are also structurally different from C. belli. Two types of C. cayetanensis meronts were reported (Ortega et al., Reference Ortega, Nagle, Gilman, Watanabe, Miyagui, Quispe, Kanagusuku, Roxas and Sterling1997). Type I meronts contained 8–12 tiny (3–4 × 0.5 µm) mature merozoites. Type II meronts contained four large slender (12–15 × 0.7–0.8 µm) merozoites.

Trier et al. (Reference Trier, Moxey, Schimmel and Robles1974) first illustrated meronts, microgamonts, macrogamonts and oocysts of C. belli by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) but did not elaborate on details of the observed structures. Figure 6 in their paper shows a meront with four partially sectioned merozoites that contain organelles typically found in coccidian merozoites (Trier et al., Reference Trier, Moxey, Schimmel and Robles1974). Figure 6A of their paper shows amylopectin granules anterior and posterior to the nucleus of merozoites. These amylopectin granules correspond to PAS-positive granules in merozoites found here. They illustrated several micronemes at the conoidal end that were misinterpreted to be present posterior to the nucleus. They also illustrated an immature macrogamont with numerous electron lucent bodies, which are undoubtedly amylopectin granules (Trier et al., Reference Trier, Moxey, Schimmel and Robles1974). A few electron dense bodies were present which are probably WFB. Figure 10 of their paper (considered maturing oocyst) is probably a macrogamont; two types of WFB are visible and they are electron dense (Trier et al., Reference Trier, Moxey, Schimmel and Robles1974). The electron lucent bodies labelled ‘L’ by them are amylopectin or lipid bodies. Trier et al. (Reference Trier, Moxey, Schimmel and Robles1974) correctly labelled microgamonts. Walther and Topazian (Reference Walther and Topazian2009) also illustrated TEM of a mature microgamont with mature microgametes with flagella.

In conclusion, despite numerous studies mentioning the presence of asexual and sexual stages of C. belli in human intestinal and biliary epithelium over the last 50 years no study had successfully described the structural features and modes of development of C. belli in humans. The current study achieved that goal using known features of development of intestinal stages of Cystoisospora species from dogs, cats and pigs and enteroepithelial stages of T. gondii in cats as a foundation to provide a narrative of the endogenous development of C. belli. This will provide a useful tool for pathologists and others interested in infectious diseases.

Acknowledgements

We thank Camila Cezar and Fernando Murata for assistance.

Author ORCIDs

J. P. Dubey, 0000-0003-4455-2870

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This study used archived material. No experiments were performed.