Introduction

‘Hic est vere Martyr, qui pro Christi nomine sanguinem suum fudit’ is the beginning of a responsorium prolixum in the Commune plurimorum martyrum of the so-called ‘Codex Hartker’.Footnote 1 Taking this statement as the starting point, this article investigates the moral and socio-historical concepts conveyed by the responsoria prolixa in this antiphoner. What is the right way of dealing with violence and suffering in liturgy and plainchant? Is it different for men, women and children? To offer a first, brief example, in the responsories one finds expressions such as ‘effuderunt sanguinem’ in references to men, women and children, but the consequences of this bloodshed vary: God crowns a man (R. Corona aurea super caput eius);Footnote 2 God recompenses a woman, Caecilia, for having led two companions to martyrdom (‘Tyburtium et Ualerianum ad coronas(!) vocabat’, R. Cilicio Cecilia);Footnote 3 and the Innocents are predictably labelled ‘sancti, qui non inquinauerunt vestimenta sua’ (R. Isti sunt sancti).Footnote 4

This article will engage mainly with the following questions. First, what are the moral and social purposes, and reasons for, such differences? Second, what evidence can we find of such messages in the music, the notation (e.g. neumes, episemata, liquescences) and/or the interaction between text and music? Because of its early high-quality neumes, the Codex Hartker is an ideal source for addressing these questions. The responsoria prolixa, with their longer, freer and more detailed texts, afford deeper insights into the intellectual world of the compilers and composers than the comparatively short office antiphons. Diastematic melodic readings and the text orthography presented in this article are taken from the fourteenth-century antiphoner Kloster Einsiedeln, Musikbibliothek 611 (hereafter EIN 611), which originated in almost the same locality as the Codex Hartker. Its later date means that EIN 611 also offers insights into the repertoire's development over time.Footnote 5 For the same reason, the twelfth-century non-diastematic sister manuscript of the Codex Hartker, St Gall, Stiftsbibliothek 388 (hereafter SG 388) is also included in this article.

In the following analyses, striking musical or textual-musical features which emphasise and even interpret the messages of the texts are encountered again and again. It is the quantity and similarity of these observations that lift them out of the haze of arbitrariness. Naturally, each text written for recitation is ambiguous when it comes to possibilities for stressing the words. (If this were not so, there would be only one possible interpretation and no more than one production of a piece would be necessary, which would automatically give the only correct interpretation.) For this reason, our thesis requires very clear examples. We must also pay close attention to individual pieces of evidence. Maybe a similar intention will be found across individual examples, as such additive evidence may also contribute to the plausibility of the thesis.

This article also seeks to demonstrate how necessary and worthwhile it is to carry out musical and musical-textual analysis of, for example, offices of the saints, assuming one wishes to paint a socio-historical portrait of the medieval era. Because antiphons and responsories were used repeatedly in liturgical services, with their particular musical-textual emphases, they fixed themselves in people's minds in a much less filtered way than grand papal pronouncements. As we might still observe today, people become holistically involved when they sing, and they often tend to appropriate messages without reflection due to repetition – an intrinsic feature of liturgy. Furthermore, the added musical dimension brings about a quicker and more intense emotional involvement than would otherwise be the case. Ultimately ‘the right feeling’ thus created is what determines whether we actually act on something. As the psychologists Klaus Rothermund and Andreas Eder formulate:

Emotion is closely interlinked with action. Often emotions are formed in motivational contexts of action and regulate further motivational action in the form of direction and energetic stimulation but also in the form of interruption, inhibition and reorientation of the action … Actual explanatory models of pursuing or regulation of actions convey altogether an appropriate theoretical frame for analysing the complex correlations between emotion, motivation and action.Footnote 6

The cognitive psychologist Markus Kiefer expresses it even more pointedly:

Emotions are of central importance when it comes to directing our actions. We can judge things in a purely rational manner, but whether we actually act on them depends very much on our emotions. And these emotions are in turn the manifestations of our experience of similar situations that were pleasant or unpleasant. There is no cold cognition. In order to do the right thing, we also need the emotion adequate to it.Footnote 7

We are all familiar with this kind of situation. For example, in a church service on a feast day I am able to sing the following line from a well-known German hymn with full-throated conviction: ‘Fest soll mein Taufbund immer stehen. Ich will die Kirche hören. Sie soll mich allzeit gläubig sehen und folgsam ihren Lehren.’ (‘May my baptismal covenant always stand firm. I want to heed the Church. May she always see me faithful and obedient to her teachings.’) As a thinking adult individual, I would hardly approve the sentence in this form, especially its ending, if it were merely spoken. But when singing it, there is a safe feeling of being in a big group, a feeling which developed from childhood, when I often sang this hymn. This is a good feeling, which makes it easier to sing the sentence. There is nothing wrong with such behaviour if it is balanced by later or earlier reflection. When I now sing this hymn, my emotions can encompass my previous intellectual reflection, creating this ‘right’ feeling during the singing without my forgetting previous reflections.

We can assume that something comparable happened in the Middle Ages. During Bible study, the monks of Saint Gall meditated and reflected upon the texts of chants they sang time and time again. During liturgical services, emotions and associations arose which were intensified through singing. We will examine examples of responsoria prolixa from some offices of the saints (men, children and women) in the Codex Hartker with respect to their socio-historical relevance, insofar as this can be deduced from lyrical, textual-musical and musical parameters. In the course of preparing this article, all responsoria prolixa in the offices of saints in the Codex were investigated. The examples chosen appear to show the most obvious indications of interaction between music and text.

St Stephen as the first martyr: the archetype of dealing with suffering and violence

Martyrs were the first saints of the Christian church. As people whose emulation of Jesus Christ went so far that they were prepared to sacrifice their lives for their faith, they are the earliest Christian role models. The position of the celebration of the protomartyr Stephen within the liturgical calendar, falling on the day after Christmas, emphasises this significance. Even before the liturgy commemorated the apostle and evangelist John, who took Christ's message out into the world, it commemorated the first martyr, Stephen. The first Matins responsory in honour of St Stephen reads: ‘Hesterna die dominus natus est in terris, ut Stephanus nasceretur in celis. Ingressus est dominus mundum, ut Stephanus ingrederetur in celum.’Footnote 8 In short, this suggests that Christ's birth on Earth is the precondition for Stephen's entrance into heaven (see Ex. 1).

Ex. 1 SG 390, p. 56; EIN 611, fol. 22r–22v.

The neumator of the Codex Hartker stressed each of the two ‘ut’ conjunctions with a pes quadratus which slows down the movement and thus emphasises the conjunction. This is significant in this context since ‘ut’ signifies the causal relation between Christ's birth on Earth and Stephen's re-birth in Heaven. The use of the same melody in both cases underlines this relationship. The melodic formula employed is often present if a monosyllabic word at the beginning of a phrase bears some sort of significance. Parallel cases with pes quadratus in the repertoire of responsoria prolixa in Hartker are: ‘NE timeas Maria’ (R. Missus est),Footnote 9 ‘ET virtus altissimi’ (R. Ave Maria)Footnote 10 and ‘ET claues regni caelorum’ (R. Simon Petre).Footnote 11 Semiological studies have demonstrated that in contexts of synhaeresis/dihaeresis the length of notes is identical.Footnote 12 This is the case in the passage ‘CUM accepero’ in R. Amo Christum.Footnote 13 If a monosyllabic word at the beginning of a phrase is not stressed, we find the pes rotundus in the formulas employed in the following passages: ‘QUEM virgo’ (R. Adorna thalamum)Footnote 14 or ‘ET omnes’ (R. Aspiciebam).Footnote 15

How did a role model such as Stephen deal with violence and suffering? The first responsory of the second nocturn, for example, reads: ‘Lapidabant Stephanum inuocantem et dicentem: domine Iesu Christe, accipe spiritum meum: et ne statuas illis hoc ad peccatum.’Footnote 16 Here, the stoning is presented almost as incidental, as if it did not interest Stephen, who cared only for celestial things. He received the stones thrown at him joyfully (‘gaudens’), as in the following responsory: ‘Impii super iustum iacturam fecerunt, ut eum morti traderent: at ille gaudens suscepit lapides, ut mereretur accipere coronam glorie.’Footnote 17 Violence triggers a paradoxical reaction as Stephen rejoices in the stoning because it means he will receive the ‘corona gloriae’. Incidentally, the motif of the ‘corona gloriae’ or ‘corona aurea’ is one encountered repeatedly in saints' offices. The melodic progression of the responsory supports the text's message (see Ex. 2).

Ex. 2 SG 390, p. 57; EIN 611, fol. 23r.

Compared to the version in the Codex Hartker, that in the Einsiedeln Antiphonary (EIN 611, fol. 23r) is more richly imbued with traces of the East Frankish chant dialect. This draws attention to such striking features as the broken ‘triad’ on the final syllable of ‘super’, which prepares and intensifies the melodic and melismatic emphasis on ‘iustum’, which is further intensified melodically on ‘fecerunt’. The godless have sacrificed a just man; worse, they have given him over to death (‘ut eum morti traderent’). There can be no greater injustice, but this just man is actually glad for it. The leap of a fifth on the final syllable of ‘ille’ expands the initial triad, especially as the melody is extended to f and then, on ‘lapides’, even up to aa. Within a half-sentence, the melody is catapulted up a ninth, running through its entire ambitus, with the exception of the subtonic F. It should be noted that this melodic reading is also supported by the Codex Hartker, and that Stephen's ‘corona’ is also set to a broken triad. This is clarified further by an impressive climax showing how Stephen, the protomartyr, dealt with suffering and violence, and should serve as an example for ‘us’.

Saint Lawrence: holy men as celestial warriors

This says it all, really: sainthood has to be attained in order to repay one's debt to God, and ‘[R.] Hic est vere martyr, qui pro Christi nomine sanguinem suum fudit’,Footnote 18 ‘[R.] Corona aurea super caput eius’.Footnote 19 These are recurring statements in the Common offices for martyrs, which, with a degree of variation and generalisation, repeat the moral and socio-political cornerstones identified in the Office of St Stephen.

Let us now compare the Office of St Stephen to that of the deacon and martyr Lawrence, first because he is one of the most revered saints, and second because, since the Battle of Lechfeld on 10 August 955 (St Lawrence's Day), which put an end to the Hungarian invasions, he has held a special war-related significance in German lands as patron of the Ottonian kings. A third reason is that in the Codex Hartker, the responsories are given their own title, which is considerably longer than that at the beginning of the office (see SG 391, p. 96). This increases their significance, at least from a visual standpoint.

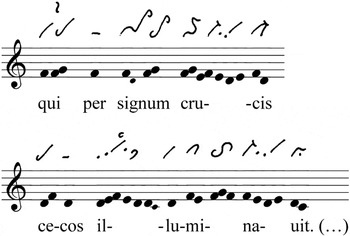

The texts for the responsories of the Office of Saint Lawrence come from different sources, such as the St Lawrence PassionFootnote 20 or the Martyrologium of the archbishop Ado of Vienne (mid-ninth century), the oldest surviving source of which is the codex St Gall, Stiftsbibliothek 454. The first Matins responsory, Levita Laurentius, adds caritas – which should be part of the job description of a deacon, as it were – to the image of the saint: ‘Leuita Laurentius bonum opus operatus est, qui per signum crucis cecos inluminauit, et thesauros ecclesiae dedit pauperibus.’Footnote 21 The Lord God addresses him as ‘puer meus’ and promises: ‘Dum transieris per ignem, flamma non nocebit et odor ignis non erit in te’ (R. Puer meus).Footnote 22 One interesting element in the Levita responsory is the relative clause ‘qui per signum crucis caecos inluminavit’. It likely relates to the following episode of the vita of St Lawrence: ‘Erat in eadem domo homo cæcus, nomine Crescentio, qui cœpit rogare beatum Diaconem, ut poneret manum suam super oculos ejus. Tunc beatus Laurentius lacrymans dixit: Dominus noster Jesus Christus, qui aperuit oculos cæci nati, ipse te illuminet: &, facto signo crucis, aperti sunt oculi ejus.’Footnote 23 The text of the Levita responsory speaks of ‘cecos’ (plural!) and thus generalises Lawrence's blessing (see Ex. 3).

Ex. 3 SG 391, p. 96; EIN 611, fol. 210r.

This blessing is given melodic emphasis through the repetition of the F which is, from a technical standpoint, merely an ornate recitation. Because of the contextual musical correlation, listeners will hear this recitation as a high point. It is the only part of the Levita responsory composed in this manner and it is not sung as fast as a recitation usually is because of the ornaments. The composer had the option of setting this phrases as a simple recitation (maybe employing a pes on ‘SIGnum’ in order to emphasise the word accent) to clarify the grammatical structure.Footnote 24 He chose instead an F-repetition at the start in combination with a pes, afterwards a virga strata with liquescence on the accented syllable of ‘signum’ and finally a liquescencent pes on the final syllable. That seems to be too much melodic and notational activity for a simple recitation for it to be without relevance. The notator of EIN 611 simplified this phrase, perhaps because there was no longer such kind of highly differenciated textual-musical relationship in the fourteenth century.

On the basis of the nuanced relationship between text and music, as well as the temporal proximity between the copying of Codex Hartker and the Battle of Lechfeld on St Lawrence's Day, let us conduct a little thought experiment in connection with the next passage. The world of medieval thought was full of association and monks were confronted with biblical texts day and night. Associations to these and other texts and contexts arose freely.Footnote 25 Jean Leclerq declared: ‘For exegesis, the free play of associations, similarities and comparisons sufficed for medieval monks.’Footnote 26 This prompts me to do the same. Starting point is the quotation ‘per signum crucis’; the full text of this in the Church's basic treasury of prayer reads (alluding to Phil. 3:18): ‘Per signum crucis de inimicis nostris libera nos, Domine.’Footnote 27 The ornate recitation might make the singer aware of the fact that this is a quotation, and that he would have had the phrase ‘de inimicis nostris libera nos, Domine’ in mind in addition to the sign of the cross described. This might in turn evoke associations with the Battle of Lechfeld, which took place on St Lawrence's Day in 955, some fifty years before the Codex Hartker was written down. The date is, still today, occasionally described (somewhat exaggeratedly) as the ‘birth’ of the German ‘nation’.Footnote 28

The victory was attributed to Lawrence among others,Footnote 29 and after the Battle of Lechfeld many churches were built and dedicated to St Lawrence.Footnote 30 Of course, this chain of associations cannot be proven, but it could provide a possible further interpretation of a text that is ambiguous, which is the case with every text written to be recited. My interpretation could be possible if one considers how political the offices of the saints often are, and what a significant event this battle was at the time. In the R. Strinxerunt,Footnote 31 Lawrence, already promoted to the status of deacon of Christ and with his eyes fixed on celestial things, mocks the coals placed under his gridiron (‘prunas insultat leuita Christi’). Therefore the singer/speaker of the prayer can ask in the repetendum and the verse: ‘Beate Laurenti, martyr Christi, intercede pro nobis. V. Mea nox obscurum non habet, sed omnia luce clarescit’Footnote 32 (see Ex. 4).

Ex. 4 SG 391, p. 98; EIN 611, fol. 210v.

The Codex Hartker neumation shows the melodic arc of meaning starting at ‘beate’ and extending to ‘martyr’, at the end of which a virga with an episema separates ‘martyr’ from ‘Christi’. Here the neumation supports the melody with a downward leap of a third.

The responsories of the Office of St Lawrence end with the same motifs as those of the Office of St Stephen. Lawrence asks the Lord for admittance to heaven and offers his thanks: ‘[R.] Suscipe spiritum meum. V. Gratias tibi ago Domine, quia ianuas tuas ingredi merui’ (R. Beatus Laurentius … et dixit).Footnote 33

Holy Innocents' Day: saints as models of innocence

Fearless belief in Christ's intercession even unto death, a gaze focused on heaven, disregard for earthly torments: this is the behaviour by which an adult can and indeed should become a saint. But what about children who die innocently, so to speak, for Christ, without having taken any kind of action? How is their ideal type presented in the responsories? This will be established using the example of the Office for Holy Innocents. Unlike Stephen and Lawrence, the innocent children ask God: ‘Why do you not defend our blood?’Footnote 34 – blood that was shed ‘like water’ in the responsory Effuderunt.Footnote 35 The melodic structure underlines the fluidity and the quantity of ‘water’ in the chant. In such cases it is of no significance whether this melody is formulaic or newly composed. Even a musical formula can show an interrelation between text and music, depending on the context. In musical rhetoric, as in verbal rhetoric, nothing is automatic. I deepen my voice at the end of a sentence, for example. This is a rhetorical formula without any deeper meaning, but in the right context it can become important. The neumation, however, demonstrates the inanity of the comparison, vividly presenting the inappropriate lightness of water in the face of mass murder (puncta as signs) (see Ex. 5).

Ex. 5 SG 390, p. 65; EIN 611, fol. 28v.

The Lord's answer to the children's question in the responsory Sub altare is ‘hold on for a little while’.Footnote 36 And they are shown their reward: they will be able to worship the living Lord ‘in saecula saeculorum’ in R. Adoraverunt, where the melodic ascent over a seventh and the interval of a fourth emphasises the aspect of eternity (Ex. 6).

Ex. 6 SG 390, p. 66; EIN 611, fol. 28v.

The children are promised salvation, not because they have fearlessly rejected the world, but ‘because they have cried out to YOU daily’, as R. Isti sunt sancti, qui passi underlines by the musically elaborate cry with its emphasis on ‘ad TE’ (see Ex. 7).

Ex. 7 SG 390, p. 66; EIN 611, fol. 28v–29r.

On both a mundane and a metaphorical level these children are saintly because ‘they have not sullied their clothes’, but ‘will walk about with me in white garments, for they are worthy’ as R. Isti sunt sancti, qui non inquinaverunt states (Ex. 8).

Ex. 8 SG 390, p. 67; EIN 611, fol. 35r.

Musically, each of the textual emphases on ‘non inquinaverunt’, ‘albis’ and ‘digni’ is stressed in its own way. The first accent on ‘non inquinaverunt’ is prepared by a G–c fourth on ‘qui’ in early sources.Footnote 37 Here the second virga element is non-cursive. This is followed by a short recitation on c, increasing the tension. On the syllable ‘inquiNA-’ before the accent, a clivis raises the level once more, to d. The accented syllable is melismatic with non-cursive neume elements, so that a non-cursive clivis on the post-tonic syllable has to capture this stress.

‘Albis’ is emphasised again, but in this case not by an accentuation of the word itself, but by a melisma on the preposition ‘IN albis’ which prepares ‘albis’ as a significant word by using a vocal accumulation. The general slowing down of movement on ‘albis’ brings about the accentuation of the word. From a semiological standpoint, the accentuation on ‘albis’ is possible because of the preparing neumation on ‘in’. Otherwise, the non-current neumes on ‘MEcum’ and ‘albis’ would be the reverse of each other: an accentuation becomes an accentuation also through non-accentuated surrounding syllables.

‘Albis’ and ‘non inquinaverunt’ belong together as a pair of words with related meanings. The melodic formula is the same in both cases. This formula may be a standard one, but there is no other responsorium prolixum in the eight mode in Hartker where this formula is used twice. The existence in two consecutive clauses, each including the highest note of the responsory, underlines the unique characteristic of this formula which makes clear in this case the relationship between ‘non inquinaverunt’ and ‘albis’. The reason given (‘quia digni sunt’) allows the tension to be released gradually, beginning with a richly ornate movement ambitus which slowly levels out in upward and downward movements from a span of a fifth to the finalis. The lengthy melismatic treatment on ‘quia’Footnote 38 underlines the condition of holiness: they are holy because they are worthy. And from a semiological point of view, this melisma is necessary to absorb the high energy created by all the non-current neumes and neume-elements before (‘SUa’, ‘AMbulabunt’, ‘MEcum’ and especially ‘albis’; in the last case all neumes are non-current).

In the verse of the same responsory for Holy Innocents, this is followed by the reason why the children are worthy: ‘Hi sunt, qui cum mulieribus non sunt coinquinati: virgines enim sunt.’Footnote 39 Here as in the context of the gospels, ‘virgo’ stands for male children, since, according to Matthew, Herod only had the male children killed. He was after all looking for Jesus, although the conclusion one draws is that preferably virginal individuals (of both sexes) can, according to medieval thinking, enter the ranks of the sainthood. The impediment to sainthood was ‘pollutio’, defilement or contamination. Arnold Angenendt writes: ‘Apparently all archaic religions shared the notion that contact with the impure, and this included sexuality, made one unholy and unfit for worship.’Footnote 40 This affected women in particular since menstrual blood was, according to medieval thinking, the greatest source of pollution.Footnote 41

In the responsories for Holy Innocents, this emphasis on virginity becomes even clearer with the stress on ‘virgines’ in the R. Centum quadraginta, Footnote 42 where the accent spans an entire phrase as the high note and target gains additional resonance from a melisma on the final syllable (see Ex. 9).

Ex. 9 SG 390, p. 68; EIN 611, fol. 29v.

The fourteenth-century Einsiedeln version disguises this treatment somewhat, since in the East Frankish chant dialect ‘hii’ is carried through to c rather than b-flat (see also ‘quadraGINta’, ‘permanSErunt’). But the composer's original intention nonetheless remains audible. Incidentally, this also applies to the 144,000 righteous people, emphasised with multiple notes at the beginning of the responsory, who are equated with the innocent children. The melody may be a formula, but it is noticeable that the text editor of the responsory placed the numeral which is usually insignificant at the beginning of the antiphon compared with the text of the Bible.Footnote 43 Furthermore, the few syllables of the numeral are set to more notes than the syllables in the rest of the responsorium. The textual basis here, as in most responsories for Holy Innocents in the Codex Hartker, is the Book of Revelation: ‘The concentration of texts from the Book of Revelation on Holy Innocent's Day is particularly striking … Multiple vigil responsories relate the whole scene of adoration to the Innocents.’Footnote 44

Saints Cecilia and Agatha: the holy woman as virgin (child) or warrior

Children have neither to fight manfully nor to regard suffering and violence with contempt in order to achieve sainthood; they ‘only’ have to bear suffering for ‘a little while’,Footnote 45 and preserve their innocence. Then the joys of eternity will last even longer for them than for everyone else. In the medieval view, however, once they have become polluted it is no longer as straightforward to attain the ranks of sainthood. Nonetheless, women could lead a saintly life in the Middle Ages. Thus Angenendt, in a work entitled ‘The Weak Sex and the Mighty Grace’,Footnote 46 argues that the idea of the weak and sinful sex was countered, among other things, by St Paul's idea ‘that God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty’ (1 Cor. 1:27ff.).Footnote 47 It followed from this that women, when it came to grace, were quite able to outdo men, and therein lay their potential for particular saintliness.Footnote 48

In short, women could become saintly only if they preserved their virginity, that is, did not actually become women, and/or if they succeeded in living more virtuously and thus more manfully then men. One of St Gall's patron saints, St Wiborada, is one example of this type. Her office, which is only recorded in the more recent sister manuscript of the Codex Hartker, SG 388 (p. 231), describes her in the following terms: ‘O beata Wiborada quae cum palma victoriae caelos intraveras’ (‘O blessed Wiborada, you who have entered the heavens with the palm of victory’).

St Agatha corresponds most closely to this type. In the Office of the Codex Hartker, she fearlessly faces her tormenter, the prefect Quintinian, who has had her breasts cut off because she rejected his suit. ‘God's impious and cruel tyrant’ she calls him who does not shrink even from cutting off that part of a woman (‘femina’ is used here, not ‘virgo’) that he himself had suckled, namely his own mother's breastFootnote 49 (see Ex. 10).

Ex. 10 SG 390, p. 121; EIN 611, fol. 174r.

The melodic structure here mimics the change in speaking habitus (Ger. ‘Sprechhaltung’), from the brusque speech of the ruler to the soft feminine words. While the beginning is syllabic, from the word ‘femina’ onwards, the melodic structure becomes fluid, adorned with numerous small groups of neumes and melismata.

In the R. Agathes laetissima, Agatha enters the dungeon ‘letissima et glorianter’.Footnote 50 The word ‘letissima’ receives melismatic, whereby the leaps of a fifth to and in ‘glorianter’ suggest a distinct tone of ostentation, clearly set apart from the rest of the melody (see Ex. 11).

Ex. 11 SG 390, p. 123; EIN 611, fol.175r.

Of passing interest here is an erasure on the ‘accented syllable’, ‘gloriANter’. Originally there was a pes, d–e, proceeding from the epiphonus, which is visible at this point in the Codex Hartker, a typical example of melodic variations over the centuries.

In R. Ego autem Agatha announces clearly in an unusual melodic structure: ‘perseverabo in confessione ejus’ (see Ex. 12).Footnote 51 The melodic leaps in the melisma on ‘perseveRAbo’ and the complementary ascending D–c leap of a seventh on ‘confessiOne’ – according to Codex Hartker a quilisma scandicus D–G–a–c (erasure in EIN 611) – are special melodic structures which emphasise Agatha's unbreakable faith (‘perseverabo in confessione eius’).

Ex. 12 SG 390, p. 123; EIN 611, fol. 175r.

Ultimately, however, Agatha is described only with attributes of male saints. Hence God himself crowns her (see R. Ipse me coronavit).Footnote 52 Agatha has outdone the men in ‘vir-tus’, and therefore receives the crown of sainthood. The only option available to other women, from the medieval viewpoint, was to preserve virginity at any price, even if it costs them their lives. St Cecilia, for example, is one of the many medieval virgin saints – actually more a girl than a woman – who suffered a martyr's death. She, like them, is betrothed to Christ and none wants to lose her immaculate state. They ask the Lord to keep their hearts and bodies pure, so that they will not be shamed (‘Fiat, domine cor meum et corpus meum immaculatum, ut non confundar’).Footnote 53 They keep the word of God in their hearts at all times, and pray day and night, as the chants recount. Observe the more ornate sections in Example 13, the R. Virgo gloriosa semper, on ‘in pectore’, ‘diebus’, ‘noctibus’ and ‘oratione’, which quite literally give resonance to this.

Ex. 13 SG 391, p. 156; EIN 611, fol. 245r.

It is stated that Cecilia calls men to martyrdom. When Valerian enters the bridal chamber, he finds her praying. A distinctive melodic structure shows the intensification through ‘cubiculum’, by way of another leap of a fourth, to ‘orantem’, the high point of the whole R. Ceciliam intra cubiculum, right at the beginning of the piece (see Ex. 14).

Ex. 14 SG 391, p. 156; EIN 611, fol. 245v.

Conclusion

In the examples presented, it has been possible to identify gender-specific and role-specific differences with regard to the representation of the behaviour which enables people to attain sainthood. These seem to be attributes and behaviour stemming directly from the medieval view of humanity. Hence the role models conveyed are fairly uniform. The only initially surprising type is the female warrior, but this can be explained if we consider the chants' prime target group. The offices of female saints contain role models for medieval (female) convents and helped medieval monasteries for men, such as St Gall, accomplish their purpose of ensuring that monks led as saintly a life as possible. Here a naturally sinful and weak woman who heroically rises above men in ‘virtus’ surely offers scope for ambition. Furthermore, the different types also stand for various types of character. These have one thing in common in their way of dealing with violence and suffering: they all gaze beyond the wretched present into their true homeland, heaven. Life does not stop with suffering. The message is: deal with suffering in whichever way you can, as a screaming child, a patient lamb or a hero, but accept and do not evade it, because in suffering you follow in Christ's footsteps. Then you will receive the ‘corona aurea’. The detailed description of suffering in the offices of the saints only makes sense because this description provides the foundation for the audience's resistance, which will always be in need of improvement.

Today, in a society of free individuals, such a message sounds like a modern maxim, albeit a well-worn one, invoking individual freedom and fulfilment. In the Middle Ages, people who heard this kind of thing were probably more easily led, for they accepted suffering, privation and war as absolute necessities, which in religious terms were required to settle at least part of their debt to God. They had heard nothing of the freedom of the individual. The community and personal affiliations were everything.Footnote 54

As has been shown here, textual-melodic parameters are important to the transmission of this message. We have seen that music gives considerable emphasis to textual messages, that additional associations are triggered in individual cases, and that the messages of the texts reach the singer and listener in a less filtered, more direct and more emotional way than words alone.Footnote 55 This increases the effect of these messages. Hence textual criticism must incorporate the findings of musicological research if the text in question was (also) performed to music. Any other approach fails to do justice either to the intention of such a text or to the history of its influence. The insight that Martin Luther formulated so aptly in the preface to the Babst hymnal in 1545 was something with which people were already familiar in the Middle Ages:

For God has made our heart and spirit glad, through his dear Son, whom he sacrificed for our salvation from sin, death and the devil. Whoever believes this in earnest cannot but be glad and sing and tell of this with joy, so that others also hear it and accept it. But if anyone does not want to sing and speak of it, that is a sign that he does not believe.Footnote 56

‘Cantando praedicare’, ‘singend predigen’, ‘preaching by chanting’: the topos always means proclaiming something with particular insistence and constancy.