WHEN THE BRITISH ORNITHOLOGIST and bird illustrator John Gould launched his monumental publication on The Birds of Australia late in 1840, the cover of the serial parts bore the image of the lyre bird (Menura superba) and a prominent dedication, “by permission,” to the young and recently-married Queen Victoria (Correspondence 2: 213; see Figure 4).1

The dedication also appeared in Gould's 1 Oct. 1840 Prospectus for the work. The Dedication page of the completed work is fuller.

Gould met Albert on 27 Mar. 1841 (Correspondence 2: 281, 288). Albert's Lyre Bird appeared in the first part of the Supplement, dated 15 Mar. 1851, just six weeks before Albert's greatest triumph, the successful opening of the Great Exhibition.

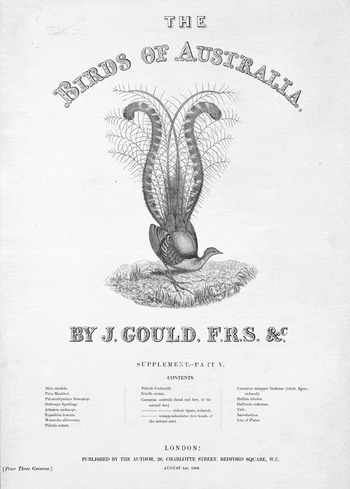

Cover illustration with male lyre bird (Menura superba), lithograph from John Gould's The Birds of Australia, Supplement Part V (London: Printed by Taylor and Francis, published by the author, 1869). The dedication to the Queen was dropped from the supplemental parts covers. Courtesy of the Natural History Museum, London, © Natural History Museum, London, 2007.

John and Elizabeth Gould, “Lyre Bird (Menura superba).” Hand-colored lithograph, from John Gould, The Birds of Australia (London: printed by R. and J. E. Taylor, published by the author, 1840–48). Vol. 3, plate 14. Courtesy of Special Collections, Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas Libraries.

While naming new species after royalty was common, Gould's association of Victoria and Albert with Australia's unusual fauna was particularly extensive, and his selection of appropriate Australian birds with which to honor the royal family was particularly careful.3

Gould dedicated The Mammals of Australia to Albert and named two other birds for family members.

John and Elizabeth Gould, “Spotted Bower-Bird (Chlamydera maculata).” Hand-colored lithograph, from John Gould, The Birds of Australia (London: printed by R. and J. E. Taylor, published by the author, 1840–48). Vol. 4, plate 8. Courtesy of Special Collections, Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas Libraries.

John and Elizabeth Gould, “Satin Bower-Bird (Ptilonorhynchus holosericeus).” Hand-colored lithograph, from John Gould, The Birds of Australia (London: printed by R. and J. E. Taylor, published by the author, 1840–48). Vol. 4, plate 10. Courtesy of Special Collections, Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas Libraries.

Figuring Victoria and Albert

AS MARGARET HOMANS AND ADRIENNE MUNICH have demonstrated individually and jointly, visual representations of Queen Victoria and the royal family – whether in official portraiture, caricature, cartes-de-visites, or newspaper wood engravings – served different and sometimes competing purposes that reflected different and sometimes competing interests and ideologies (see also Houston 1–10). “In place of a determinate identity of a singular Queen Victoria,” Homans and Munich argue, “many conflicting ideas of her increasingly came to be used to model or to justify a wide variety of cultural practices and personal self-fashionings” (3). The visual representations of Victoria reflected these conflicting public perceptions of her private life as well as of her performance as sovereign. Central to these perceptions were issues of gender and gender roles and their implications for domestic and imperial politics. Visual depictions of Victoria and her family almost invariably required negotiation of the tensions created by the existence of a Queen Regnant who wished to present herself as bourgeois wife and mother, a Hanoverian princess and her Coburg consort who sought to be identified as the thoroughly British heads of a thoroughly British empire. As Homans writes, representations of Victoria and Albert from their marriage in 1840, whether commissioned portraits or popular images, “helped to disseminate a complex picture of royalty's superordinary domesticity, to publicize the monarchy as middle-class and its female identity as unthreateningly subjugated and yet somehow reassuringly sovereign” (Homans 19).4

On this issue, see also Casteras, Gernsheim, Nadel, and Schama.

Several major events dominated representations of Victoria, and the public response to her, in the early years of her reign.5

See Williams, St. Aubyn, and Weintraub.

Margaret Homans's analysis of four visual representations of Victoria and Albert from the early 1840s – two paintings commissioned by Victoria and two colored lithographs distributed by G. A. H. Dean and Co. – not only suggests some of the complexities and tensions in figurations of royal power and gender roles during the years when Gould's Birds of Australia first appeared, but also points to representational strategies (in composition, color, and “attitudes”) relevant to Gould's depictions of the lyre birds and bower birds.6

My discussion here also draws on Cumming 109; Munich 27, 58–59; Nadel 185–87; Ormond 150–52; and Schama 155–57.

Edwin Landseer, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at the Bal Costumé of 12 May 1842, 1842–46. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of The Royal Collection, © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2005.

The two lithographic prints of the Royal Family also encode tensions about Victoria's role as imperial monarch even as they seem to celebrate the connections between her sovereignty and her domesticity. In “To the Queen's Private Apartments: The Queen and Prince Albert at Home” (1843), Victoria is both “private” and “at home” to visual callers, absorbed in her role as mother but presiding above Albert, who plays on all fours with the children. In “The Royal Family in the Nursery” (ca. 1845; Figure 9), however, Victoria sits to the side, surrounded by the younger children, while Albert presides at the center of the picture. He leans against the empty throne-like chair he himself cannot occupy, but which the patriotic Prince of Wales, on whom all the adults and the Princess Royal gaze, will. Both images present the Queen and the Royal Family as upper-middle-class and domestic while providing visual reminders of Victoria's sovereignty, yet both also express some anxiety about her absence from the throne, and the proximity of Albert to it.

“The Royal Family in the Nursery,” c. 1845. Hand-colored lithograph. Sold by Dean & Co., London. Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

John Gould and Australia

THE SUCCESS OF GOULD'S BIRD folios depended on a combination of aristocratic patronage, professional connections, and entrepreneurial initiative, with The Birds of Australia marking a momentous transitional phase in Gould's career. Initially destined to follow in the footsteps of his father, a royal gardener at Windsor, by age twenty-one Gould was in business in London as a taxidermist and dealer in natural history specimens. With a client list that included George IV, the Earl of Derby, the British Museum, the Royal College of Surgeons, the Zoological Society, and the East India Company, Gould was well connected. In 1827 he was appointed the Zoological Society's Curator and Preserver, and two years later he married Elizabeth Coxen, a naval captain's daughter employed as a governess by an important government official. A capable artist, Elizabeth drew and lithographed the birds when Gould began his first serially-published illustrated folio the following year. A few months after completing this successful project, Gould launched a more ambitious one, The Birds of Europe, in 1832. As this publication finally drew to a close in 1837, Gould turned his attention to Australian birds.7

On Gould's time in Australia, see Datta, Lambourne, Sauer, Tree.

Gould's extensive collection of Australian species was largely an accident of his marriage. Elizabeth Coxen Gould's brothers, Stephen (1798–1844) and Charles (1809–76), had emigrated to New South Wales in 1827 and 1834, respectively, and collected on Gould's behalf. Realizing he already owned one of the finest collections of Australian birds and mammals in Europe, Gould began a full-scale publication on Australian birds in 1837 but soon realized he needed to visit the colonies himself to conduct first-hand observations (Gould to Jardine, 2 Nov. 1836 and 16 Jan. [1837]; Gould to William Swainson, 21 Jan. 1837; Correspondence 1: 145–46, 161, 158). Resigning his position at the Zoological Society early in 1838, he set sail in May for Van Dieman's Land (Tasmania) with Elizabeth; their eldest son; a nephew; John Gilbert, Gould's assistant and collector; and two servants. Arriving in September, Gould spent the next twenty months in Van Dieman's Land, New South Wales, and South Australia. In Van Dieman's Land, he and his family enjoyed the hospitality of Lieutenant Governor Sir John Franklin and his wife at Government House, where the pregnant Elizabeth gave birth to a son on 6 May 1839. In April of 1840 they embarked from Sydney for England, while Gilbert, who had explored parts of the continent not visited by Gould, remained behind to continue collecting.

Gould's Australian enterprise demanded both greater entrepreneurial initiative and more extensive dependence on Britain's imperial resources than his earlier works, yet Gould fairly consistently aligned his interests with those of the landed and gentlemanly classes both at home and in the Colonies. By the late 1830s Australia was increasingly regarded in Britain as a land of opportunity rather than simply a colony of convicts and self-exiles, so Gould was effectively participating in the free emigration of those seeking to make their fortunes (Clarke 78–90). He took care to stake his claim to the Australian birds within the ornithological community in the years leading up to his trip. Although his investment in Australia – the undertaking cost him nearly £2000 – and the corresponding risk to his livelihood if The Birds of Australia failed, were considerable, Gould was confident that The Birds of Australia would enjoy “a great sale” that would “amply repay me for my exertion” (Gould to William Swainson, 21 Jan 1837; Gould to Baron Lafresnaye, 27 Sept. 1837; Gould to J.E. Gray [draft], 23 Apr. 1841; Gould to Jardine, 30 Apr. 1838; Correspondence 1: 161, 191–93, 234; 2: 297). Yet the Goulds saw themselves as engaged in an extended project comparable to that of the Coxen brothers rather than a short-term speculation. Elizabeth was openly disdainful of those who came to these “money making colonies” determined to “get money and return to England as soon as they can,” while both she and John expressed admiration for Stephen's “Lordly estate,” his large and patiently-accumulated holdings of land and livestock.8

Elizabeth Gould to Mrs. Mitchell, 4 Jan. 1839 and 6 Dec. 1839; Elizabeth Gould to Elizabeth Coxen, 13 Sept. 1839; Gould to Stephen Coxen (draft), 5 Apr. 1841; Correspondence 2: 8, 99, 132, 290. On the visualization of Australian land as English aristocratic estates, see Ryan 74–76.

Stephen's lordly estate undoubtedly utilized convict labor, a source of particularly intense debate in both Britain and the Colonies during the period of Gould's visit and the years immediately following it. Gould arrived in Van Dieman's Land in the same month as English newspapers were reporting the ongoing hearings of the Parliamentary committee on the transportation system chaired by its energetic Benthamite opponent, William Molesworth, as well as the furor occasioned by the publication of a damning report on the convict system written by Alexander Maconochie, Franklin's private secretary (see Hughes, ch. 14–15). In Britain, the view that the Australian colonies were morally tainted by transportation and the convict system had strengthened in the 1830s. The government seized on Maconochie's report to justify ending the convict system, outraging many landowners in Van Dieman's Land and New South Wales who depended on convict labor. The following month, transportation to New South Wales was stopped entirely, which meant that Van Dieman's Land, to which transportation continued, had to absorb even more convicts just as the economies of both colonies were sliding into a devastating depression from which they would not emerge until the late 1840s. While the Goulds were clearly sympathetic with those like Franklin who wanted humane treatment for convicts, and although Elizabeth expressed great moral discomfort at being surrounded by convicts, this did not mean that they opposed the convict system itself. It was, after all, Lord Stanley, the son of the Earl of Derby, Gould's greatest patron, who championed transportation in Parliament throughout this period, and John accepted when Governor George Gipps of New South Wales offered him a convict to act as servant and assistant during an expedition into the interior (Clarke 21–23, 29–34; Elizabeth Gould to Mrs. Mitchell, 4 Jan. 1839 and 6 Dec. 1839; Gipps to Gould, 7 Sept. 1839; Kavanagh to Gould, 22 Feb. [1840]; Correspondence 2: 8, 132, 97, 151).

Gould had come to these money-making colonies well-equipped for exploiting Britain's imperial presence. Armed with letters from, among others, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, the Secretaries of the Admiralty and the Royal Geographic Society, and the President of the Royal Society, Gould carried instructions to the colonial Governors and captains of the Royal Navy that he be afforded every assistance and protection in his work. He also received specimens collected by members of the Navy's various surveying ships working the Australian coasts. Gould presented himself publicly, and was perceived by others, as engaged in a largely self-sacrificing project of scientific and national significance. As the Duke of Sussex put it in his letter of introduction, Gould's “exertions will materially promote the interests of Natural History, and greatly add to the riches of our National Collections” (24 Apr. 1838; Correspondence 1: 227; see also Gould to Lord Glenelg, 8 May 1838; Correspondence 1: 236–37; and Gould, Introduction 2–3). During Gould's absence and after his return, many commentators and reviewers echoed this, describing The Birds of Australia not as a speculative business venture but as a patriotic act in the service of both Britain and the realm of knowledge, with Gould's outlay in time, effort, and money entitling him to patronage in the form of subscribers.

Although Gould would note in his Introduction that “the field [of Australian birds] was comparatively a new one, and of no ordinary degree of interest, from the circumstance of [Australia] being one of the finest possessions of the British Crown” (1), the sparsely settled and unexplored areas of Australia were still contested spaces when it came to natural history. Gould and Gilbert found themselves engaged in an imperial competition with representatives of other European powers. John Hutt, the Governor of the Swan River Colony in western Australia, was especially glad to see Gould in the field:

I wish other men of Science would show themselves as patriotic in their views as yourself. We know nothing of Australia as yet except that it is the land of convicts & kangaroos & this after 50 years possession! Why the French would have had 50 books, folios & sets published by this time. Indeed foreigners Germans are now anticipating us & we shall learn from them to understand the production of our own country, always excepting ornithology. (Hutt to Gould, 23 Apr. 1839; Correspondence 2: 53)

Figuring the Lyre Bird

MENURA SUPERBA WAS ONLY KNOWN to European ornithologists from skins and stuffed specimens, so observing it in the wild was one of Gould's highest priorities for his trip, and he successfully sought them at the first opportunity. Menura specimens, whether for display or dissection, were among his most valued acquisitions, parceled out to leading ornithologists and anatomists as well as to wealthy patrons. Although still seeking information about the Menura's nesting habits after his return to England, Gould was clearly anxious to make his findings public. He discussed the bird at the Zoological Society on 11 May 1841, just before the appearance of the part of The Birds of Australia containing the Menura plate on 1 June.

At three guineas per part, The Birds of Australia was well beyond the means of all but the most affluent. Yet Gould's illustrations and descriptions circulated more widely than his small subscriber base would suggest. Individual subscribers often made their copies available to others, and those owned by institutional subscribers in Britain, on the Continent, and in Australia were accessible to a broader if still limited circle. Reviewers of The Birds of Australia often provided detailed descriptions of the more notable plates and copious extracts from Gould's letter-press. The Westminster Review not only reproduced two plates for D. W. Mitchell's 1841 review essay of Gould's works, but also made colored versions of these and two others available to the public for sixpence each (Mitchell 26 and n). Prolific scientific popularizers like Jane Loudon and J. G. Wood spread Gould's accounts and images even more broadly. Loudon obtained Gould's permission to reproduce his illustrations and descriptions of the lyre bird and the spotted bower bird for her Entertaining Naturalist (1843), a work widely used in schools. Wood's New Illustrated Natural History (1855) included extended extracts from Gould on the lyre bird and satin bower bird, with illustrations based on, if not copied from, The Birds of Australia (Loudon to Gould, 9 Nov. 1842; Correspondence 3: 127; Loudon 242–44, 274–77; Wood 326–28, 370–72). Gould's friend the physician and ornithologist C. R. Bree later told Gould that his illustrations had been copied in popular publications without acknowledgment not only in Britain but “all over Europe” (9 Apr. 1858; qtd. in Datta 180).

If the Menura superba was for Gould an emblem of Australia, and lyre birds generally an appropriate genus for honoring Victoria and Albert, what were the characteristics and meanings that made them so? In his descriptive text, Gould explains that the lyre bird's fitness as an emblem of Australia hinges on its being both unique to Australia and an object of wonder for European naturalists. It is the imperial perspective, in other words, that elevates the Menura superba above other uniquely Australian species. The marvelous physical aspect of the species is, of course, its lyre-shaped tail feathers, in which, says Gould, all the interest in the bird adheres. The elaborate tail feathers of the male Menura clearly connect it to that even more familiar royal bird, the peacock, and yet the Menura is also very different from the peacock. In contrast to the peacock's iridescent greens and blues, the Menura's colors are browns and russets, and its body is exceptionally plain. The behavioral contrast between the two birds is also striking. Whereas the peacock struts, the Menura is extraordinarily shy. Indeed, Gould says “[o]f all the birds I have ever met with, [it] is by far the most shy and difficult to procure.” It is a bird of a “wandering disposition” only seen singly or in pairs, with the curious habit of scratching out small mounds of earth on which the male tramples and sings, “at the same time erecting and spreading out his tail in the most graceful manner” (Handbook 1: 298–99).

The lyre bird's subdued coloration and shy demeanor made it a fitting emblem of the young queen and her new consort. Australia had long been seen in Europe as a land of eccentricity and reversal, a view powerfully reinforced and extended by the European encounter with its strange flora and fauna in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Clarke 154–68; Ritvo 1–50; Ryan 105–17; B. Smith 184). While Gould occasionally evokes this way of seeing, the fascination exerted by the lyre birds lies, as it does for the royal couple, in a relative mysteriousness and inaccessibility ultimately revealed to be familiar and domestic rather than exotic. As a sort of royal portrait, Gould's plate of the Menura superba participates in, and indeed may be regarded as an early example of, the domestic iconography cultivated by Victoria and Albert, appearing precisely when portraiture of Victoria was shifting to representations of her as wife and mother. If the single male Menura standing alone on open ground on the parts covers is posed in such a way as to emphasize formality and symmetricality – note the absence of background and the way the bird has been positioned to display its tail with rigorous bilateral symmetry – the male and female in the plate (Figure 4) are depicted in an informal, unsymmetrical, domestic pose. The male stands on the branch of a tree with the female sitting beside him. Although the male's tail is displayed at the center of the plate, the (awkward) angle at which it is held reduces its symmetrical appearance. The viewer's eye is drawn more to the birds as a complementary couple, their subdued coloration almost identical. The larger, standing, displaying, male contrasts with the smaller, seated, female with its less elaborate tail, yet this contrast is presented as harmonious. No nest is depicted, but the postures are those of the incubating female and the male about to leave in search of food. Since Gould's text emphasizes the Menura's shyness and the density of the brush in which it lives, we have the sense of being afforded a privileged glimpse of this couple “at home,” as in the Dean and Co. lithographs, in its private, secluded domestic space.

And yet Gould's text exposes the extraordinary artificiality and constructedness of this domestic scene. Menura move about almost constantly on the ground. While they have extraordinary leaping ability, they spring upward onto tree branches only when they are fearful or suddenly attacked. They build nests on rock ledges or near the ground rather than in trees. They are also, Gould stresses, “of solitary habits” (Birds of Australia vol. 3, plate 14). On the only occasion when he saw two birds together, they were males engaged in “play.” And although only the male lyre bird has the extraordinary tail, the plumage of male and female is so similar that Gould's description is not sex-specific until the very end, when he casually notes that “[t]he female differs in wanting the singularly formed tail.” While this reference to the female's lack of an elaborate tail enables us to recognize the bird on the cover of the serial parts as a solitary male, its downplaying here serves to underscore the way the visual logic of the parts cover aligned M. superba with Victoria, especially since the prominent dedication to “Her Majesty” appeared directly beneath the bird. Taken together, these two depictions of the lyre bird offer Gould's solution to the problem faced in portraits of Victoria and Albert of how to represent Victoria as both ruling monarch and submissive wife. In The Birds of Australia, the cover illustration offers an image of the solitary Sovereign in subdued but regal splendor, while the plate provides a portrait of a royal but domestic couple.

Gould's images of the lyre bird also worked to flatter the Colonies and to present both colonial and British subscribers with a portrait of Australia as a stable and domestic nation in which new wealth at home and abroad was replicating the traditional landed polity of Britain (Clarke 120–41; Ryan 74–76). Because of the publication's expense, Gould sought colonial subscribers as assiduously as he did British ones. While Gould's secretary, Edwin Prince, was back in London canvassing the aristocracy and gentry, Gould courted wealthy local landowners as well as the colonial representatives of Britain's ruling elites, appealing simultaneously to imperial and national pride. Barely a month after his arrival in Van Dieman's Land, the Hobart Town Carrier was calling on affluent citizens to “enter their names as subscribers” to Gould's work “and thus become the Stanleys and the Devonshires of Tasmania, by becoming the patrons of science” (12 Oct. 1838; qtd. in Correspondence 1: 283). One potential colonial subscriber wrote to Gould that any man of “prominent station” refusing to support this “National” publication “owes you an explanation” (Alfred Stephen to Gould, 31 Mar. [1840?]; Correspondence 2: 157). By the time Gould was back in England and the first part being readied, his subscriber list – divided into British and Australian sections, with Victoria and Albert at the top – included seventy-one colonial names (about 40% of the total) headed by the four colonial Governors and the Commander of the Forces in New South Wales.9

The subscriber list was printed with the Prospectus and appears in Correspondence 2: 214.

As royal portraits and many popular representations of Victoria and her family in the early 1840s belied the growing economic and political unrest in Britain and the anxieties surrounding Victoria's rule, The Birds of Australia correspondingly avoided reference to the colony's financial distress and the debates over the transportation of convicts. Yet Gould's dependence on his Australian subscribers was such that the economic depression of the 1840s was nearly as catastrophic for him as it was for his Australian brothers-in-law, both of whom were bankrupted, the increasingly despondent Stephen Coxen committing suicide in 1844. Gould's correspondence of 1842–44 is especially anxiety-ridden and full of laments about his precarious financial situation. Although he had insisted that subscribers commit to the entire work, many were simply unable to pay, so he eventually had to allow some to take only as many parts each year as they could afford. To make matters worse, Elizabeth Gould's death from puerperal fever on 15 August 1841, five days after the birth of their daughter, Sarah, forced Gould to hire a full-time artist to replace her. His great speculation, so close to resulting in a spectacular financial as well as scientific success, was on the brink of failure. “[T]he welfare of the publication and indeed of myself,” Gould wrote to Gilbert, “depends entirely upon the prosperity of my affairs in the Colonies” (Gould to Gilbert, 14 July 1842; Correspondence 2: 205–07). Having intended that The Birds of Australia should enable him to cease dealing in natural history specimens and mark his elevation to the status of “Author,” and having identified himself as such in his Prospectus, Gould found himself bartering parts of his Australian collections for institutional subscriptions or offering them for sale to various patrons and contacts (Prince to Thomas Ewing, 11 July 1845; Gould to Gilbert, 24 Aug. 1844; Gould to Lord Derby, 7 Sept. 1840 and [16 Oct.?] 1840 [draft]; Gould to T. C. Eyton, 25 Sept. 1840 and 30 Sept. 1840; Gould to C. Dalen, 30 Jan. 1845; Prince to Lord Derby, [4 Mar.?] 1845 [draft]; Correspondence 2: 193; 3: 68, 245–47, 337–38, 376, 383, 409). Yet Gould continued to churn out the quarterly parts of The Birds of Australia on schedule. While he may have had little other choice as a single parent in dire financial straits, the need to project stability and maintain continuity in his publication meant that “Australia,” at least in this context, was represented without visible sign of its economic turmoil. Quite the contrary – Australia's relation both to Gould and to its imperial Sovereign was presented as a dignified combination of patronage and patriotism, royal display and domestic tranquility.

Figuring the Bower Birds

OF THE BOWER BIRDS GOULD would later comment that “[I]f any one circumstance…would tend to hand down the name of the author of the ‘Birds of Australia’ to posterity, it would be the discovery and the publication of the singular habits of the Bower-birds” (Supplement plate 36). Just one week after his return to England, Gould delivered a paper to the Zoological Society on the bowers of the spotted and satin bower birds, and he presented a fine spotted bower to the British Museum. The plates of these two species in The Birds of Australia were extraordinary (Figures 5 and 6). Appearing in the fourth part in September 1841, they were double plates of elaborate, lavish scenes, taking up two full imperial folio pages. Hugh Strickland told Gould they were “truly pictorial and Audubonic,” a comment echoed in the Annals of Natural History (Strickland to Gould, 9 Nov. 1841; Correspondence 2: 359; “Gould's Birds of Australia” 338). Gould apparently also had, or at least contemplated having executed, oil paintings of these plates to display at the 1841 British Association meeting in Plymouth (Gould to Jardine, 2 July 1841; Correspondence 2: 316). Gould's verbal and visual depictions of the bower birds garnered considerable public attention that only increased in 1849 when the Zoological Society's pair of satin birds constructed a bower (Scherren 89).

The illustrations of the bower birds and their bowers further emphasize the extent to which Gould wished to construct iconic Australian birds as domestic, blurring or erasing almost any suggestion of sexuality. While the bower birds were not closely related to the lyre birds taxonomically, the two groups were connected in Gould's descriptions by their shyness, their preference for thick brush, and their antics, particularly of the male. But the central question surrounding bower birds was the purpose of the bowers. In his initial presentation to the Zoological Society, Gould stated that they “are used by the birds as a playing-house, or ‘run,’…and are used by the males to attract the females” (“On the ‘bower’” 94). Yet he was considerably less assertive, and even contradictory, about the bowers’ role in courtship in the descriptions accompanying the plates in The Birds of Australia itself: “For what purpose these curious bowers are made,” he wrote, “is not yet, perhaps, fully understood” (vol. 4, plate 10). They are clearly not nests, he insists, but it is “highly probable” that the birds use them “at the period of incubation.” It is similarly probable that they serve as gathering places “at the pairing time,” although Gould uses the terms “playing-grounds” and “halls of assembly” to describe the way “many individuals of both sexes…run through and around the bower in a sportive and playful manner.”

The plates, however, work very differently. Even more so than with the Menura superba, Gould offered highly domestic scenes in which courtship and sexuality are largely erased in favor of husband/wife and family portraits. In his discussion of the spotted bower bird, Gould stresses that in his experience a bower “formed the rendez-vous of many individuals” and that he observed only males racing through the avenue-like run; the plate, however, depicts a single pair, with what is apparently the female inside the bower. While the plate can certainly be read as the male courting the female, the female's positioning within the bower invokes the iconography of nests, with the solicitous male attending to his mate's needs. The plate of the satin is even more domestic. At the center is a female seated in the bower, its sides encircling her. The larger, darker male perches just outside the bower, much like Albert as paterfamilias in “The Royal Family in the Nursery.” On the ground outside the bower are two juvenile males. The one in the right foreground is younger, for its plumage closely resembles the female's, while the one to the left is in the process of acquiring the black feathers of the adult. The scene's visual logic works at many levels. The female is enshrined in a position suggestive of incubation in what is made to look unquestionably like a nest rather than a “playing-ground” or “hall of assembly.” The male stands placidly to the side rather than running frenetically about, and his size and position cast him as the female's protector. We see not many birds but a single family, with not one but two offspring, and of apparently differing ages.

Australian Birds and Victorian Gender Roles

IT WAS OF COURSE ELIZABETH GOULD who drew and lithographed the plates of Menura superba and the spotted and satin bower birds. After her untimely death, the unusually elaborated domestic iconography of the lyre bird and bower bird plates for The Birds of Australia became increasingly prominent in Gould's illustrated bird folios, particularly in his tremendously successful works on Humming-birds (1849–61) and The Birds of Great Britain (1862–73). Yet even as she helped produce these paeans to domesticity, Elizabeth Gould's own life as wife, mother, and artist enacted tensions closer to those involved in representations of Victoria and Albert. She received only limited public credit for her work as Gould's chief artist, for it was Gould's name alone on the part covers and title page, and to the public these were primarily his books. Although her name appeared on the plates themselves, they appeared after his, and reviewers often ignored her contribution and treated the plates simply as Gould's. On the other hand, Elizabeth was not quite so self-effacing, nor her work quite so unappreciated, as is sometimes claimed (Gates 74, 77). Elizabeth frequently referred to The Birds of Australia as “our” work, and some reviewers not only praised her artistic skills but also acknowledged the joint nature of the enterprise.10

Elizabeth Gould to Elizabeth Coxen, 9 Jan. 1839 and 13 Sept. 1839; Correspondence 2: 13, 99. For reviews see the Hobart Town Carrier, 12 Oct. 1838, Correspondence 1: 282–83; M[itchell] 273, 287, 288, and 296; “Gould's Birds of Australia,” Spectator 1239.

Yet Gould continued to struggle with the increasing evidence of the role of the lyre bird's tail and the bower bird's bower in mating. Both his Introduction and Handbook to The Birds of Australia included an account of the satin bower bird by a Sydney man who stated that the bowers are “built for the express purpose of courting the female in” and who emphasized the male's extraordinary sexual energy: “the male will chase the female all over, then go to the bower, pick up a gay feather or a large leaf, utter a curious kind of note, set all his feathers erect, run round the bower and become so excited that his eyes appear ready to start from his head” (Introduction 56–57; Handbook 1: 444, 448). In the Handbook Gould affirmed that the bowers “are places of resort for both sexes of these birds at that season of the year when nature prompts them to reproduce their kind. Here the males meet and contend with each other for the favours of the females, and here also the latter assemble and coquet with the males” (1: 310). Yet the language here and elsewhere is circuitous and euphemistic, with the bowers described as “merely sporting-places,” and in some instances Gould remains silent about courtship. In the case of the Menura, Gould did not connect the male's similar behavior on its “play-grounds” with courtship despite the evident contradiction with his emphasis on the bird's shyness.

Someone who both made this connection and appropriated Gould's acknowledgments about courtship was Charles Darwin. Gould and Darwin had known each other for years – Gould and Elizabeth had described and drawn the bird specimens, including those from the Galapagos, for Darwin's Zoology of the Beagle voyage. Gould, however, was no supporter of natural selection, and his works after 1859 offer fairly clear if unpolemical visual and textual statements against it (J. Smith 54–59). His scenes of peaceful avian nuclear families, with displays of courtship and sexuality avoided in favor of depictions of the ornithological equivalent of the separate spheres, became a significant part of this anti-Darwinian presentation. Nonetheless, Darwin found in Gould's books a wealth of evidence to support his own views on both natural and sexual selection. He annotated his copy of Gould's Handbook extensively, using the work as his primary source of information about Australian birds for his discussion of sexual selection in The Descent of Man (Darwin, Marginalia 337–40). In particular, Darwin highlighted the very behavior of lyre birds and bower birds that Gould was reluctant to acknowledge, and he utilized Gould's text and images in doing so.

Although Darwin's discussion of sexual selection in birds is sometimes read as inscribing Victorian patriarchal notions about the sexes onto nature (Yeazell 219–28), his accounts are heavily directed against Gould's far more domestic visions. For Darwin, lyre birds and bower birds are of interest neither for their shyness nor their subdued regal appearance but for their extended “nuptial assemblages,” the males’ frenetic and even violent courtship activities, and the females’ aesthetic preferences and active role in mate-selection. Reproducing an image of the spotted bower bird (Figure 10) taken from A. E. Brehm's Thierleben (1864–69) but clearly based on Gould's original plate, and quoting copiously from accounts in Gould's Handbook about male display and female selection, Darwin directs us to see a mutual and very sexual courtship scene rather than a nesting pair (Darwin, Descent 2: 68–71, 101–02).

“Bower-bird, Chlamydera maculata, with bower (from Brehm).” Wood engraving, from Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (London: Murray, 1871). Vol. 2, figure 46. Courtesy of Special Collections Library, University of Michigan.

Darwin in effect set Gould's text against Gould's plate, exploiting Gould's admissions and inconsistencies in an effort to entice readers into seeing the gender traits and sexuality of these quintessentially Australian species in radically different ways. But if Darwin's appropriation of Gould's lyre birds and bower birds exposes the tenuousness of those representations, the fact that Darwin was largely unsuccessful at convincing his contemporaries of the truth of sexual selection suggests the extent and continuing power of a domestic vision of gender that encompassed both the Monarchy and the birds of its antipodean dominions.