Introduction

Humans are story-telling animals, apprehending the world and communicating about it in narrative terms. Metaphors represent an important narrative form, communicating complex concepts using analogy and inference. Richardson (Reference Richardson1990) highlights the ubiquity of metaphor in social science, arguing that paying attention to the metaphors-in-use is important in both carrying out research and representing its findings. Institutional theorists see rhetoric and metaphor as important indicators of underlying norms and assumptions (e.g. Suddaby and Greenwood, Reference Suddaby and Greenwood2005), whilst linguistic sociologists emphasise problematising the use of metaphorical language in understanding social life (Sewell, Reference Sewell2010). A rich seam of social science research focuses upon the effect of common or recurring metaphors in structuring and framing the social world. For example, Cornelissen et al. (Reference Cornelissen, Holt and Zundel2011) explore metaphors used by managers seeking to legitimise organisational change, arguing that particular types of metaphor may be more successful in particular contexts. Perhaps more dramatically, Annas (Reference Annas1995) locates the failure of the Clintons to reform the US health system in, amongst other things, a poor choice of metaphor. This illustrates the importance of metaphors in understanding policy implementation. Allan (Reference Allan2007) used this approach in studying natural resource management schemes. She found that the metaphors used had profound implications for the planning, implementation and evaluation of water management schemes, with those who used a ‘journeying’ metaphor adopting different approaches to those who spoke about ‘treating illness’ in a watershed area. Thus, the metaphor-in-use both expresses existing norms and potentially determines how policy is implemented. We respond to Dobson’s (Reference Dobson2015: 702) call for empirical policy research which takes seriously what she calls ‘practice languages’ or ‘sector speaks’ – the unconscious and naturalised use of language by insiders – as a means of understanding how policy is enacted through day-to-day practices.

The pathways metaphor has wide currency in policy research and practice including: in housing, to describe the influence of socio-economic conditions on forms of housing tenure (Payne and Payne, Reference Payne and Payne1977); in education, to refer to vocational or academic ‘tracks’ that students join (Watt and Paterson, Reference Watt and Paterson2000), often with limited prospects for switching; and criminal justice, where the ‘pathways out of crime’ metaphor has become so well established as to attract classification as professional myth (Haw, Reference Haw2006). In this paper we focus particularly on health services and examine a metaphor ubiquitous across the world – the ‘care pathway’. We explore its use in the aftermath of a wide ranging policy-driven change to the NHS in England, consider how it might drive responses to change and ask whether alternative metaphors might drive different reponses.

Sometimes called a ‘clinical pathway’, De Bleser et al., Reference De Bleser, Depreitere, Waele, Vanhaecht, Vlayen and Sermeus2006) identified the concept’s first use in the United States (US) in the 1980s (Zander et al., Reference Zander, Etheredge and Bower1987; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kocman, Stephens, Peden and Pearse2017) describe pathways as a manifestation of Taylor’s (Reference Taylor and Pugh1990) scientific management approach, whilst others trace their origin to Second World War military planning (Schrijvers et al., Reference Schrijvers, van Hoorn and Huiskes2012). From this perspective, pathways are a means of specifying, co-ordinating and controlling care processes, to manage costs, and improve the quality and safety of care (Hunter and Segrott, Reference Hunter and Segrott2008).

However, there is a more critical literature, arguing that care pathways are not simply neutral tools (Hunter and Segrott, Reference Hunter and Segrott2008); they are socially constructed, embodying particular power relationships (Barnes, Reference Barnes2000) whilst at the same time construing patient care as self-evidently capable of pre-specification (Berg, Reference Berg1997). Pinder et al. (Reference Pinder, Petchey, Shaw and Carter2005) argue that the pathway metaphor may be unhelpful, silencing and marginalising some voices. In this paper we explore the consequences of the use of the care pathways metaphor in service planning/commissioning. Based upon a study of commissioning in the English NHS we explore how the widespread use of the care pathway metaphor shapes both the conceptualisation of the task of commissioning health care and how it is carried out. We argue that, like all metaphors, care pathway is generative, not simply usefully specifying required processes but also determining what are seen as appropriate solutions to problems arising following a significant system change. We offer a new metaphor – the ‘service map’ – and discuss the different perspectives that it may encourage, whilst also being mindful of its generative potential.

Our contribution is twofold. Firstly, we offer an additional approach for those studying public service policy, organisation and management. As Dobson (Reference Dobson2015) has highlighted, the unconscious use of particular language by those enacting policy provides a window into their social worlds. We take this a step further, demonstrating that the metaphors-in-use in a situation of policy-driven change affect the enactment of that change. Secondly, we extend the literature on care pathways, moving beyond their use in individual care settings to explore their role in service planning and commissioning.

What follows is divided into five sections. A brief overview of the relevant literature is followed by an exploration of care pathways as a metaphor. We then describe our methods, before exploring the generative effect of the metaphor of care pathways in our study. A final discussion contextualises our findings, considering how an alternative metaphor might change the framing of the work to be done and exploring the implications of this for the wider literature.

Care pathways: an overview

Care pathways have been defined in a number of ways. De Bleser et al., Reference De Bleser, Depreitere, Waele, Vanhaecht, Vlayen and Sermeus2006) suggest the following definition:

A [care] pathway is a method for the patient-care management of a well-defined group of patients during a well-defined period of time. A [care] pathway explicitly states the goals and key elements of care based on EBM guidelines, best practice and patient expectations by facilitating the communication, coordinating roles and sequencing the activities of the multidisciplinary care team, patients and their relatives; by documenting, monitoring and evaluating variances; and by providing the necessary resources and outcomes. The aim of a [care] pathway is to improve the quality of care, reduce risks, increase patient satisfaction and increase the efficiency in the use of resources (De Bleser et al., Reference De Bleser, Depreitere, Waele, Vanhaecht, Vlayen and Sermeus2006: 553).

This identifies a care pathway as a co-ordination technology, implying an underlying rationality in which goals can be clearly specified. In the UK the early focus was upon pathways as a tool for quality improvement, using a rational/technical ‘evidence-based medicine’ approach (Hunter and Segrott, Reference Hunter and Segrott2008). However, increasing emphasis on choice and competition (Department of Health, 2003) has driven a more explicit focus on care pathways as co-ordination tools (Atwal and Caldwell, Reference Atwal and Caldwell2002), whilst growing interest in control of professionals under the rubric of ‘clinical governance’ supported their adoption for quality control (Ellis and Johnson, Reference Ellis and Johnson1999). Pinder et al. (Reference Pinder, Petchey, Shaw and Carter2005) thus document a rapid growth of interest in care pathways in the UK from 1998 onwards.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to review the care pathways literature in detail. However, it can be loosely categorised into four groups. Many papers focus upon defining, implementing or evaluating pathways for particular conditions. Thus, for example, Graham et al. (Reference Graham, Magee, Hunter and Atkinson2010) review evidence about diabetes management, advocating a particular improved care pathway. This literature links care pathways to clinical guidelines, defining and instantiating in a pathway the most effective care for particular conditions. A second tranche of literature explores care pathway implementation, focusing upon ‘barriers’ to their adoption (e.g. Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Jarrett, McCrone and Thornicroft2010). A third large literature takes a more questioning approach. Moving beyond the assumption that care pathways embody best practice and are axiomatically valuable, this approach seeks to evaluate the impacts of care pathways. In this vein, Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Gillen and Rixson2009) reviewed the benefits of care pathways, and concluded that:

I[ntegrated] C[are] P[athways] are most effective in contexts where patient care trajectories are predictable. Their value in settings in which recovery pathways are more variable is less clear. ICPs are most effective in bringing about behavioural changes where there are identified deficiencies in services; their value in contexts where interprofessional working is well established is less certain. (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Gillen and Rixson2009: 61)

Such limited evidence of benefit has not, however, translated into caution amongst health care system leaders, with care pathways assuming an ever more prominent role in service planning (Allen, Reference Allen2010b).

These three broad strands of literature take a largely uncritical view, presenting care pathways as a straightforward technology, which either does or does not improve care. A final, and rather smaller, body of literature critiques this view, using concepts from Science and Technology Studies to investigate the work done by care pathways as technologies, exploring embedded power and agency. For example, drawing upon ethnographic research on care pathway development, Allen argues:

The technologies that emerge from this process [of pathway development] are not neutral tools reflecting an underlying reality, but are constituents of social relations and possess structuring effects of their own. They are active in organizing health care work and in the creation and maintenance of hierarchies between and within professional groups. They differentiate who can write where and how much, determining the information that is relevant and which activities are organizationally accountable or not. (Allen, Reference Allen2010a:48)

Care pathways thus act to structure what counts as relevant, systematically including or excluding viewpoints depending on approaches to development (de Luc, Reference de Luc2000). Allen (Reference Allen2010a) highlights the multiple purposes of care pathways, distinguishing between a managerial viewpoint seeing care pathways as tools to hold clinicians to account, and a clinical viewpoint seeing care pathways as a structure supporting the exercise of valid clinical judgement. She identifies care pathways as a boundary object (Allen, Reference Allen2009), usefully blurring distinctions between these two approaches to support action without requiring explicit reconciliation between them.

From this perspective, care pathways may enhance rather than limit the expression of professionalism. An alternative view comes from Harrison and Ahmad (Reference de Luc2000), who coined the term ‘scientific bureaucratic medicine’ to describe the algorithmic approach of care pathways and guidelines. For Harrison, this approach presaged a commodification of medical care, necessary to support competition between providers (Harrison, Reference Harrison2009). Care pathways thus represent a tool by which neoliberal ideals of choice and competition (Green, Reference Green2006) may be enacted within public services, allowing costing and enumeration of ‘packages’ of care which could be delivered by any competing provider.

This highlights one of the relatively unconsidered aspects of care pathway use: the context within which they are operationalised. Whilst contexts necessarily vary by health system, the international literature identifies two broadly distinct uses for care pathways. The first lies within individual care settings, where care pathways are a means of co-ordinating the care required by categories of patients. Overlapping this, and arising from service models separating purchasers of care from providers (Figueras et al., Reference Figueras, Robinson and Jakubowski2005), care pathways are also used by purchasers/commissioners to specify the care to be purchased, potentially supporting choice and competition. These uses are subtly different, as one arises within a care setting and is usually, at least in part, locally specified, whilst the other might, at the extreme, be specified externally by a purchasing authority, and used to manage contracts. In practice, these two uses overlap and are elided one with the other: potential care providers often help to specify care pathways to be commissioned (Checkland et al., Reference Checkland, Harrison, Snow, McDermott and Coleman2012).

Pinder et al. (Reference Pinder, Petchey, Shaw and Carter2005) extend these critiques in a study of care pathway development in a commissioning organisation. Researchers asked those involved to draw their particular care pathway. They found significant variation in the pathways drawn from different professional perspectives, with different professionals delineating their zone of practice. They found that: ‘pathways were important mobilising metaphors, prescribing as well as describing’ (Pinder et al., Reference Pinder, Petchey, Shaw and Carter2005: 775) and argue there would be benefits to clinical teams fostering greater awareness of pathways as evolving processes rather than constituting complete, finished products. In this paper we take this idea further, exploring the generative nature of the pathways metaphor in relation to health care planning, and critically considering the application of an alternative metaphor.

Metaphors and meaning

Public services, administration and research are full of metaphors. Policy researchers, for example, use the metaphor of ‘translation’ to explain and illuminate aspects of policy transfer between contexts (Johnson and Hagström, Reference Johnson and Hagström2005), whilst Malpass conveys a rich picture of both the problems facing housing policy and the potential knock on effects of these on other services with his use of the metaphor of a ‘wobbly pillar’ (Malpass, Reference Malpass2003). In the health field we talk about ‘barriers to change’ (Checkland et al., Reference Checkland, Harrison and Marshall2007), ‘frontline NHS staff’ and ‘battles against disease’, ‘Integrated Care Pioneers’ (https://www.england.nhs.uk/integrated-care-pioneers/), and ‘care pathways’. Each metaphor conveys more than the words alone. Thus, ‘barriers’ to change implies a clear road across which an obstacle has fallen, but it also implies a solution – the lifting of the barrier, or its destruction. In reality, of course, change does not happen for complex reasons embedded in social realities, and ‘barriers’ are rarely amenable to simple removal (Checkland et al., Reference Checkland, Harrison and Marshall2007). Similarly, military metaphors such as ‘frontline staff’ or ‘battles against disease’ valorise health service staff and responsibilise patients, whilst implying that those failing to support ‘our troops’ or patients failing to recover are somehow culpable. In each case the reality is more complex and messy, and the solutions implied may not be as straightforwardly beneficial as the metaphors suggest. Moreover, embedded power relationships within particular metaphors may go unnoticed. As Foucault (Reference Foucault, Martin, Gutman and Hutton1988) reminds us, a ‘responsibilised’ patient is not simply engaged in neutral acts of self-help; they are ‘disciplined’ to act in ways which may serve other ends.

These things matter, because as Schön (Reference Schön and Ortony1993) clearly demonstrates, metaphors are generative. That is, they frame problems such that certain solutions are visible or desirable and others are not. Thus, for example, Schön (Reference Schön and Ortony1993:130) describes how re-imagining a paint brush as being like a pump opens up a range of different technological approaches to improving performance than appear when thinking of it as a device for spreading liquid. Conceptualising the things impeding change as ‘barriers’ focuses attention on approaches to removal, rather than accommodation or adaptation, whilst describing those at the forefront of change as ‘pioneers’ prevents consideration of the fact that they may be misguided. In each case, the metaphors are not necessarily immediately visible, and the embedded power relationships may be obscure.

‘Care pathway’ is a metaphor rich with meaning. Whilst its origin is plural, it has arisen in the context of a significant sociological literature likening patients’ experiences of illness to a journey (for example, see Lapsley and Groves, Reference Lapsley and Groves2004). Care pathway is thus a concept with broad appeal, as it suggests that not only will care be available for patients on their ‘journey’, but also implies guidance, direction and clarity. The pathway metaphor allows those planning and providing care to see themselves as accompanying patients on their journey, smoothing the way and helping them move logically and inevitably from a to b. However, this begins to demonstrate a potential problem. A pathway can suggest unidirectionality, with limited branching or switching, and implies a clear understanding of the order in which things need to happen. But the real world of patient care is rarely that simple, and generative metaphors not only explain the world, they shape it. Llewellyn et al. (Reference Llewellyn, Higgs, Sampson, Jones and Thorne2017:422) explore the care pathways metaphor from the patient’s perspective, arguing that: ‘[pathways] shape patients’ lives by particular and often hidden valuations about risk, evidence, tolerability of side effects and symptoms, and fundamentally the goals of care.’

We extend Pinder et al.’s (Reference Pinder, Petchey, Shaw and Carter2005) and Llewellyn et al.’s (Reference Llewellyn, Higgs, Sampson, Jones and Thorne2017) critiques, suggesting that not only is the metaphor ‘pathway’ potentially unhelpful at the micro-level of providing and receiving care, where it may act to marginalise patient voices, engender false expectations of the degree of co-ordination that is possible, conceal inter-professional rivalries and obscure the uncertainty inherent in medical treatment (Pinder et al., Reference Pinder, Petchey, Shaw and Carter2005; Llewellyn et al., Reference Llewellyn, Higgs, Sampson, Jones and Thorne2017), but it is also unhelpful at the meso-level of care organisation, commissioning and planning. Using evidence from a study of a significant reorganisation of the NHS in England, we show that the care pathway metaphor potentially hampered commissioners as they adapted to policy-driven change by limiting the range of options ‘seen’ as being possible and by focusing adaptive activity on particular approaches. More broadly, we show that paying attention to – and possibly altering – the metaphors-in-use within a complex public sector field provides an additional avenue for understanding and supporting policy enactment and change.

Methods and context

The context of this study is a major reorganisation of the English NHS, resulting from the Health and Social Care Act 2012 (HSCA12). It is not our intention here to describe this in detail; multiple accounts of the changes which occurred have been published (for example, see Exworthy et al., Reference Exworthy, Mannion and Powell2016; Timmins, Reference Timmins2012). For our purposes the important fact is that the reorganisation not only abolished some organisations and created others, but it also significantly redistributed responsibilities between a wider cast of organisations within the system. In particular, the HSCA12 transferred responsibility for public health services from the NHS to Local Authorities (LAs), and created a new national body responsible for providing public health advice and support, Public Health England (PHE). Commissioning responsibilities, previously held by Primary Care Trusts (PCTs), were redistributed between LAs, newly created Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and a new national body, NHS England (NHSE). The outcome of these changes is widely agreed to be a more fragmented system with, for example, a report from a House of Lords Select Committee concluding that: ‘The Health and Social Care Act 2012 has created a fragmented system which is frustrating efforts to achieve further integration’ (House of Lords Select Committee, 2017, para 99).

We used qualitative methods to explore various groups’ – including employees of CCGs, NHSE, LAs and some third sector organisations – experiences of the reformed commissioning system in two health economies, centred upon two large urban areas in England. Ethical approval was granted by University of Manchester Ethics Committee in March 2015. A total of 143 interviews with 118 unique participants were conducted between July 2015 and August 2017. Interviewees included both clinicians and managers from the aforementioned organisations. Interviews were carried out by JH and AH, and conducted either face-to-face or by telephone. Respondents were asked to reflect upon their experiences of commissioning services since the HSCA12; the concept of pathways was not initially a focus of the study, and not mentioned specifically by the interviewer. A snowball approach was used. Initial interviewees were identified primarily by searching the web sites of relevant organisations within each area. Interviewees were asked to recommend colleagues who they thought, based on the issues discussed during their own interview, may have insightful perspectives to offer. Twenty-five interviewees were interviewed twice, in order to follow up particular issues that were the subject of ongoing change in the case study areas. In each case, the research team contacted the interviewee to request a subsequent interview.

Interview transcripts were uploaded to the computerised data analysis package Nvivo 10, and read repeatedly for familiarisation. Within these accounts, the concept of care pathways was so naturalised amongst interviewees that they appeared unable to talk about their work – and the increased complexity that they were experiencing – without using it. Moreover, in team discussions about the emerging findings, it became clear that its use was associated with particular ways of speaking about tasks at hand, often alongside concerns about ‘fragmentation’. It was thus clear that the metaphor played an important role in the discourse surrounding adaptations to the reforms. In order to explore this emic phenomenon more closely, all mentions of the word ‘pathway’ were extracted. Associated data extracts were scrutinised for evidence of generative work associated with the metaphor. Team members discussed these data extracts, and analytic categories were created. These are reported below, and generic job titles are employed in data extracts to preserve respondent anonymity.

Results

Care pathways in the reorganised system

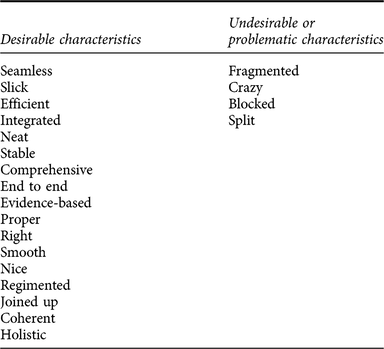

The concept of care pathways was ubiquitous, with respondents from all organisations drawing heavily and repeatedly upon it. Respondents often accompanied their use of the term with evocative adjectives. These are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Adjectives associated with care pathways

These descriptors suggest a desire for clarity and simplicity, with complexity tamed, muddle removed and every eventuality covered. They also imply some ideal yet to be attained, a ‘proper’ pathway, ‘the right’ pathway, coherent, and possibly just out of reach. When things went wrong, pathways were described as broken up, their coherence lost. We were told many stories of ‘broken’, ‘fractured’ or ‘fragmented’ pathways. For clarity and brevity, we present three of these as vignettes in Figures 1–3, highlighting the specific aspects of pre and post-Act commissioning that demonstrate a pathway related issue, an articulation of this by an interviewee, and an assessment of the role that the pathway metaphor plays in this articulation.

Figure 1. Child and Adolescent Mental Health services (CAMHS).

Figure 2. Complex oncology pathways.

Figure 3. Specialised services.

In Figure 1, the participant appeals to the ‘pathway’ approach to solve the problem of integrating different commissioners, but highlights challenges in developing such a solution, exacerbated by the split in commissioning responsibilities between different organisations. In Figure 2, the respondent highlights the complexity of breast cancer services, particularly as new tests and technologies are introduced. The pathway metaphor infuses the account, with reference to ‘go[ing] for treatment’, and ‘onward travel’. However, whilst the manager talks about ‘the pathway’, s/he later goes on to suggest that actually the complexity of services makes it a ‘crazy’ pathway that would be very difficult to commission.

Other similar examples discussed in interviews included obesity, HIV, maternity and drug and alcohol services. In all examples, informants used the metaphor of ‘pathway’ to describe the issues that they were experiencing following the reforms to the system, with associated adjectives such as ‘blockages’ or ‘fractures’. However, closer examination of the accounts suggests that the metaphor may magnify rather than solve the identified problems.

Pathway: an unhelpful metaphor?

As the vignette in Figure 2 highlights, the pathway metaphor is inadequate when faced with complex services commissioned and delivered by a variety of organisations. The point being made in the example is about the complexity of commissioning since the HSCA12. However, conceptualising the task as ‘commissioning a pathway’ compounds that complexity. If care is conceptualised as singular and unidirectional as inscribed in the pathway metaphor, then it is indeed a complicated and difficult task to make sure services are ‘joined up’. However, if the pathway metaphor is removed, we are left with patients requiring a number of different types of services at different times. Sometimes they will need more specialised services, sometimes routine local services. Thinking of it as a pathway – linear, unidirectional, moving from a to b – makes the task one of specifying what should happen in what sequence. However, patients vary and the sequence of care cannot always be pre-specified. Taking away the pathway metaphor paradoxically may simplify the task, reconceptualising it simply as ensuring that sufficient capacity is available in the relevant services, and that patients can access them as needed. Figure 3 illustrates further how letting go of the pathways metaphor might be helpful in conceptualising commissioning across multiple local areas involving multiple commissioners.

These examples suggest that removing the idea that it is necessary to design a single pathway suiting all localities potentially makes the problem easier to solve. Commissioners no longer need to ‘design a pathway’ which is seamless, they just need to consider what services might be required and make sure that patients from different localities can access them. ‘Pathway’ thus complicates the problem, rather than solving it.

Pathway: a generative metaphor

These examples suggest that the pathway metaphor might make the job of commissioners adapting to a new system more difficult, because it conditions those involved to think of their task in a particular way. Perhaps more worryingly, the metaphor may also generate a medicalising approach. In our interviews, patients were described as being ‘on’, ‘put into’, ‘flowing through’, ‘led’ along and ‘moving down’ pathways, implying motion, but also passivity, controlled by the parameters of the pathway to which they had been assigned. Our respondents talked about ‘intervening earlier in the pathway’ [4438 NHSE manager], and a ‘long term conditions pathway from prevention to end of life care’ [2388 CCG manager]. This latter implies that anyone and everyone might be conceptualised as ‘on’ a pathway, including people (the targets of prevention) who currently would not regard themselves as needing care. Llewellyn et al. Reference Llewellyn, Higgs, Sampson, Jones and Thorne(2017:422) highlight the potential for care pathways to ‘shape patients’ lives’; conceptualising even those not yet ill as ‘on a care pathway’ implies a medicalised view of the world, with potential significant consequences for society more generally. There is also an implication that once ‘on’ a pathway, it might be difficult for patients to get ‘off’. When talking about orthopaedic services, respondents highlighted the slide towards expensive treatments once a patient started along a pathway:

You get to a surgeon, and a surgeon will say, oh yeah we’ll do your hip. He won’t say, no we’ll not do your hip… So we’ve had this thing about to try and get this concept out into, certainly, all our members, around, we should do a lot more at this end of pathways, and be much more supportive. [4785 CCG clinician]

The solution to this perceived problem was to design another, separate pathway, not including surgery:

What we’ve managed to implement this year, which has been quite political, but we’ve mandated a community MSK Service, which is therapy led with consultants involved and all referrals now go through the MSK Service and patients are given informed choice and proper assessments in terms of whether they need to follow a therapy pathway or a surgical pathway [4721 CCG manager]

This may or may not be a desirable approach; the point in highlighting this is to suggest that the pathway metaphor is acting generatively in determining what solutions are regarded as possible. Rather than working to change surgeons’ behaviour – an option clearly regarded as too difficult - or to provide a variety of options in one clinic, commissioners designed a separate, non-surgical pathway. In other words, the pathway metaphor was active in making particular solutions appear obvious, whilst potentially obscuring alternatives.

The pathway metaphor also generated particular ways of describing problems - pathways are ‘blocked’, rather than services overwhelmed:

Our relationships [with the local authority] are improving, but there’s still a transparency issue, because there are spending cuts, so we’ll hear… for example, that they are reducing the number of social care placements without carefully planning it with the health service staff, in terms of, you know, what alternatives we need to put in place or whether we could have jointly commissioned those placements – [that]would have been cheaper than the implications around, you know, the acute pathway being blocked [4721 CCG manager].

Thus, the lack of availability of social care services is conceptualised in terms of the ‘blockage’ it creates in the ‘acute care pathway’. Conceptualising the problem in this way is likely to lead to a particular set of solutions, focused upon the needs of frail patients leaving hospital. It also allows organisations shift blame, and potentially obscures or downplays the political decisions underlying funding levels.

Thus, the metaphor used defines the task, whilst at the same time projecting a particular narrative that may deflect attention from more fundamental underlying problems of funding or political ideology. This commissioner described a planned stakeholder event in this way:

Today we’re going to… work with this stakeholder group around their views, their opinions et cetera, because what we’re looking to do is change the care pathway for intermediate care in older people [7831 Commissioning Support Unit manager]

The commissioning task is not to explore stakeholders’ views about the range of services available, rather it is to ‘change the care pathway’. Starting from this metaphor confines the task within a particular set of parameters, excluding some areas of policy from discussion. Interestingly, some of those who had consulted patients found that the concept of care pathways had less resonance amongst users:

Certainly the feedback we got through the consultation was that the public generally were really open to that community based design and the service wrapped around the patient, rather than the patient jogging between different steps on the pathway [7679 CCG manager]

Discussion

In this paper we have responded to Dobson’s (Reference Dobson2015) call for empirical research which foregrounds ‘practice languages’ (p.702) in understanding how policy is enacted. We have highlighted the ubiquity and breadth of use of the pathways metaphor in relation to a range of public services, and unpicked its use in the health field. Exploring how commissioners approached their role in the context of a large scale health system change, we have shown how pervasive the metaphor of ‘care pathways’ is amongst commissioners, and how it tends to condition particular ways of seeing their job. This is not to claim that it is never useful; indeed, the very complexity of the commissioning role in the more complicated system made the metaphor particularly attractive, with commissioners from all areas expressing their concern over the changes as a desire for simpler or more straightforward pathways. However, notwithstanding its appeal, we have shown that the pathway metaphor tends to limit the appreciation of possible solutions to problems, framing the issues in particular way and highlighting some approaches whilst hiding others. Thus, for example, a problem with a surgical orthopaedic service was solved by creating a separate ‘new pathway’, rather than by working with the service provider to change their behaviour. Moreover, the pathways metaphor may obscure the power relationships and political ideologies which underpin particular approaches to service delivery, whilst shaping the choices available to service users in particular ways.

Of course, the metaphor-in-use is not the only factor affecting the system’s responses to change. Indeed, the very complexity and reach of the changes that occurred means that many contextual factors will have been at work in determining system responses. Nevertheless, exploring the use of the pathways metaphor by our respondents has provided an additional way of understanding the impact of these policy changes, and has suggested an alternative approach by which ongoing adaptation might be facilitated: might changing the metaphor change the way in which the task is perceived?

Commissioners aim for ‘seamless’ and ‘joined up’ pathways, and see ‘blocked’ pathways as problematic, but as the breast cancer example above (Figure 2) suggests, the care that individual patients require may not be appropriately organised in a linear fashion. They may need to see a specialist for a while, return to a more general service when stabilised, seeing the specialist again if something changes. This is not a unidirectional ‘pathway’; it is a patient moving between available services as their circumstances require. We concur with Pinder et al.’s (Reference Pinder, Petchey, Shaw and Carter2005) suggestion that the pathway metaphor is liable to be invested with a problematically high degree of objectivity and solidity by professionals, in such a way as to foreclose consideration of processes of creation, obscure the individual life worlds of patients, and engender conflation between the pathway as a construction and the processes and events it is intended to represent. Moreover, as highlighted by Harrison (Reference Harrison2009), the use of the care pathway metaphor in service commissioning in part arose out of a need to ‘package’ services so that they could be specified and potentially put out to tender to multiple providers. It thus inscribes in the service as a whole a particular approach underpinned by an ideology privileging choice and competition, even though this underpinning ideology is rarely visible to those using the metaphor as convenient shorthand.

In response to these concerns, we offer a different potential metaphor for service planners and commissioners: a service map. This new metaphor resonates with the ‘journey’ metaphor so often used by patients, but emphasises the multiplicity of ways in which citizens might engage with services. A map suggests that a patient may travel in various directions, or miss out a particular destination, whilst remaining orientated and clear about options. Thinking of service planning and commissioning as a task of drawing and populating a map reconceptualises the key tasks as being about providing information about services, as well as ensuring that it is clear how the different destinations on the map relate to and connect with one another. A service map may also facilitate better integration of care for people with multiple complex long-term health conditions, as it challenges the single disease-specific structure inherent to the pathway metaphor. Conceptualising service commissioning as producing a service map leaves space for consideration of individual patient’s needs and values, as it removes the assumption built into the pathway metaphor (and illustrated in our examples) that patients, once ‘on’ a pathway, will move ‘seamlessly’ through its stages. A service map may thus support a more authentically person-centred approach, providing opportunities for patients to consider, with their healthcare professionals, the available services for their condition, with their personal goals, values and beliefs as a guide to help them decide what they wish to do. Furthermore, conceptualising service commissioning as drawing a map may allow a broader range of ideological approaches to service delivery to be enacted. Whilst a map may allow choice, it does not necessarily or inevitably imply the commodification of care packages, and could therefore support an approach to service design based upon planning and management of linked services rather than competition. Crucially, in the more complex post-HSCA12 English NHS, the idea of commissioning as ‘map making’ moves us away from the metaphor of the ‘blocked’ pathway, and provides a common language for commissioners responsible for different services to talk to one another. Commissioners in different organisations could agree what was missing from a map, and work together to fill the gap. Moreover, the map metaphor shifts focus away from trying to pre-specify the order in which things should occur towards ensuring links between services function well in whichever order they are accessed. Of course, it may always be necessary for some things – tests, perhaps – to happen before others such as diagnosis, but any essential sequences could form part of a map’s notation.

Changing the metaphor also changes the nature of the task of integration between services. ‘Integrated care’ (with the associated metaphor ‘integrated care pathway’) has emerged as an important goal for welfare provision across the world (Suter et al., Reference Suter, Oelke, Adair and Armitage2009). The care pathway metaphor positions integration as an act of joining up, so that pathways can be ‘seamless’. It focuses attention on multidisciplinary teams (Stokes et al., Reference Stokes, Kristensen, Checkland and Bower2016), and on contracts linking providers together (Addicott, Reference Addicott2014). A service map approach to commissioning could refocus attention on the relations between services, the amount of information they have about one another and their ability to see themselves in respect to one another, with structural or functional integration considered according to how far they enable working together, rather than being seen as an end in themselves.

Maps, of course, carry their own metaphorical baggage. Price-Chalita (Reference Price-Chalita1994: 242) notes, “[t]he map is commonly regarded as an objective record of what exists in space, and hence the map is often a metaphor for transparency” or, indeed, a symbolic shorthand for a depiction of truth. Yet a map is a product of interpretation, abstraction, and idealised representation. Thus, the process of map production can be understood as fundamentally political: “[t]o catalogue the world is to appropriate it, so that all these technical processes represent acts of control over its image which extend beyond the professed uses of cartography.” (Harley, Reference Harley1989: 13). However, this could also be regarded as a strength of this alternative metaphor. The accounts of our respondents suggest that pathways appear natural and endemic, existing in the world rather than being actively created. Re-imagining the role of commissioners as ‘map makers’ explicitly positions them as active political actors, and this potentially opens them up to greater scrutiny. Of course, map-making remains constrained by the political and policy environment in which they are conceived, and embedded power relationships will continue to determine what is possible. However, drawing the map becomes a visible act of prioritisation and resource distribution, about which debates may occur and for which the map-maker can be held accountable. Care pathways, by contrast, tend to render decisions about resource allocation invisible, as such decisions fall outside the purview of any particular pathway, which is presented in neutral terms as the expression of the best evidence in any particular condition.

The map metaphor may also emphasise process and flow rather than destinations fixed in space and time. Haraway (Reference Haraway2013) develops this idea of a map as a guide to evolving possibilities. This represents a shift from maps as a means of “transparently communicating the totality of what exists” to “rhetorical guides to possible worlds” (Price-Chalita, Reference Price-Chalita1994: 244). In health care organisation, Pinder et al.’s (Reference Pinder, Petchey, Shaw and Carter2005) conceptualisation of care pathways aligns with this. They argue for a processual approach, focusing upon the drawing and redrawing of pathway ‘maps’ from different perspectives – patients, commissioners, providers – rather than the creation of a single, comprehensive, one-time picture. Understanding commissioning (or planning) as map-making is in keeping with this approach.

Health systems face huge challenges, and ensuring the provision of care that patients experience as integrated in the face of shifting population needs is a complex task. The recent reorganisation of the NHS in England is widely agreed to have made this task more difficult, generating a more complicated system (Exworthy et al., Reference Exworthy, Mannion and Powell2016). Our study of this new system has yielded an important insight: whilst struggling to adapt to change, service planners reached for a familiar metaphor which may, in practice, have made their task more difficult. We have considered an alternative metaphor, suggesting that conceptualising the task of service planning as one of ‘map making’ may have broader value. A conscious use of a new metaphor to describe service commissioning may prompt more detailed consideration of the issues involved, make explicit power relationships and thus may provide an opportunity for improved accountability. ‘Map making’ may link more closely with the lived experiences that patients describe, with systems characterised by plurality of supply such as those based around a personal insurance model with potentially the most to gain. Our study does not, however, test that proposition, and research is needed to explore whether and how far it is possible to change the metaphors-in-use. As we have noted, ‘care pathways’ are institutionalised within the health field; changing that may be difficult.

Nonetheless, we would argue that it may be worth trying. As Schön (Reference Schön and Ortony1993) has shown, and our study confirms, all metaphors are generative, bringing into view particular ways of doing things and hiding others. We argue not for a barren language, scrupulously avoiding analogies and metaphors, but for their conscious, thoughtful and reflective use. As suggested by Dobson (Reference Dobson2015) we have examined empirically the ‘practice languages’ (p702) in use amongst service commissioners. Surfacing such naturalised discourses has allowed us to critically examine their impact and the assumptions and ideologies embedded within them. As Schön highlights, it is not metaphors per se which are problematic, rather it is their unconscious use:

One of the most pervasive stories about social services, for example, diagnoses the problem as “fragmentation” and prescribes “coordination” as the remedy. But services seen as fragmented might be seen, alternatively, as autonomous. Fragmented services become problematic when they are seen as the shattering of a prior integration. The services are seen as something like a vase that was once whole and now is broken. Under the spell of metaphor, it appears obvious that fragmentation is bad and coordination, good. But this sense of obviousness depends very much on the metaphor remaining tacit. (Schön, Reference Schön and Ortony1993 p138)

With this in mind, we offer our metaphor of commissioning as ‘map making’, conscious of its potential limitations and of its generative nature. We hope that academics and service commissioners, as well as patients and carers will engage with us in debating its merits and considering how it affects the solutions that might be sought to current health system problems.

Disclaimer

This paper is based on independent research commissioned and funded by the NIHR Policy Research Programme (Understanding the new commissioning system in England, PR-R6-1113-25001). The views expressed in the publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health, arm’s length bodies or other government departments.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our participants, who were generous with their time and helpful in facilitating contacts with their colleagues and knowledgeable informants. In addition, we would like to acknowledge how much we owe to our colleague, Julia Segar, who sadly died before this manuscript was written. Julia was an important member of our team, and the ideas expressed here owe a significant debt to her sharp intelligence and insight.