Analysis of public policy involves a range of actors and takes place in many forums with outcomes entering the public domain through means such as government statements, newspaper editorials, non-governmental briefings and academic articles. Yet despite the seemingly never-ending scrutiny and claims ‘policy has been successful’, authoritative closure on the issue of a policy's success or otherwise can be difficult to achieve. As Dye (Reference Dye2005 p. 332) argues:

Does the government generally know what it is doing? Generally speaking, no … (E)ven if programs and policies are well organized, efficiently operated, adequately financed, and generally supported by major interest groups, we may still want to ask, So what? Do they work? Do these programs have any beneficial effects on society? Are the effects immediate or long range?… Unfortunately, governments have done very little to answer these more basic questions.

Of course, politics is frequently partisan, and policies framed as successful by some political actors may be framed as unsuccessful by others (Stone Reference Stone2002; Fischer Reference Fischer2003).

Intuitively, we know that the ideal of complete success is rarely met. Some shortcomings or failings permeate virtually all policies. Some are small such as a five-year bridge building project that is a few months late or achievement of a 12 per cent budget cut instead of a target of 12.5 per cent. Others are considerable, such as a public health warning containing erroneous and potentially life-threatening information for some individuals, or train services aiming for 95 per cent punctuality but only achieving 50 per cent. The policy sciences lack an over-arching heuristic framework which would allow analysts to approach the multiple outcomes of policies in ways that move beyond the often crude, binary rhetoric of success and failure.

The purpose of this paper is to advance our understanding by building on recent work (e.g. Marsh and McConnell Reference Marsh and McConnell2010a, Reference Marsh and McConnell2010b; Bovens Reference Bovens2010) by clearly defining policy success and developing an analysis which unfolds from this definition to its polar opposite, failure, and various shades in between. It draws on a wide range of literature to illustrate why success and failure are bound inexorably with each other.

The word government is used throughout this article, whilst recognising that modern public sectors are characterised by multifaceted systems of governance, (see e.g. Bell and Hindmoor Reference Bell and Hindmoor2009; Osborne Reference Osborne2009). The term is useful because it captures that aspect of success which relates to the values, aims and policies of elected governments. The paper first provides a brief overview of a variety of literature on success and failure in order to identify gaps and themes to build on. Second, it shows that dividing policy into process, program and political dimensions, allows us to conceive of successful and unsuccessful outcomes in each of these realms. Third, it defines policy success on the basis that it is a matter of fact as well as of interpretation. Fourth, it details a spectrum of outcomes from success to failure. Finally, it suggests that there are several main contradictions evident in the overlap between the three different realms of policy, including what is known colloquially as good politics but bad policy.

Why We Need a New Approach

Six important strands can be highlighted as the contributions to our thinking about success and failure. First, literature on policy evaluation and policy improvement is close to Lasswell's (Reference Lasswell1956, Reference Lasswell1971) vision of a policy sciences which contributes to societal betterment. Indeed, he devotes over seven pages in A Pre-View of Policy Sciences, to more than 60 detailed ‘criteria of policy’, which are designed to provide guidance to policy scientists to ‘bring about improved capability in the formation and execution of policy’ (Lasswell Reference Lasswell1971 p. 85). Criteria range from providing dependable information to all members of the decision making process, through to the need for internal appraisal to be supplemented by external appraisal. Political criteria are beyond the scope of his study on the assumption that political decisions are a given. Failure is also beyond his scope, other than a general recognition that goals might not be met.

Contemporary writings are plentiful on the role of evaluation as a process for policy refinement and learning, and on tools and techniques for achieving this (Gupta 2002; Weimer and Vining Reference Weimer and Vining2005; Miller and Robbins Reference Miller, Robbins, Fischer, Miller and Sidney2007). As policy analysis has developed, so too has its debates and methods. The logic is that achieving policy success resides in good policy design, evaluating the ex ante likely impact of proposed policies, rather than relying simply on ex post evaluation to produce a stamp of success or failure, or something in between that is followed by policy refinement, change or even termination. More generally, the literature on policy evaluation and improvement contains different views on success (usually implicit), taking political goals as a given and hence success resides in meeting targets and achieving outcomes (Sanderson Reference Sanderson2002; Boyne Reference Boyne2003, Reference Boyne2004). Others are more sceptical of leaving politics out of evaluation because doing so avoids questioning societal power frameworks. They tend to assume that successful policy is one which redresses power imbalances, reduces inequalities and involves stakeholders in formulating policy goals and evaluating results (Fischer Reference Fischer1995; Taylor and Balloch Reference Taylor and Balloch2005; Pawson Reference Pawson2006).

Second, there is the concept of public value. It originates with Mark Moore (Reference Moore1995) as an antidote to the assumptions pervading American discussion of government tending to be wasteful and bureaucratic. His strategic triangle framework is a surrogate for what a successful public sector looks like. Public value rests on three tests being met: (i) production of things of value to clients and stakeholders (ii) legitimacy in being able to attract resources and authority from the political authorising environment and (iii) being operationally and administratively feasible (Moore Reference Moore1995 p. 71). Subsequent case studies and debate show that public value is something of a slippery concept (see Rhodes and Wanna Reference Rhodes and Wanna2007, Reference Rhodes and Wanna2008, Reference Rhodes and Wanna2009; van Gestel et al. Reference van Gestel, Koppenjan, Schrijver, van de Ven and Veeneman2008; Steenhuisen and van Eten Reference Steenhuisen and van Eeten2008). Moore doesn't define public value and it is as contested as the term public interest. The reality of public bodies is that they need to provide many and often conflicting values. In Moore's work, there is clear recognition that public value (as a surrogate for successful policy) does not rest on value being completely achieved, but there is no indication of how analysts may capture value shortfalls or conflicts. A new framework is needed which helps deal systematically with degrees of success and failure.

Third, a group of writings deal with good practice in the process of policy making and management. The field includes writings on the benefits of policy design (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1997), deliberation and public engagement (Gutmann and Thompson Reference Gutmann and Thompson2004), incremental bargaining (Lindblom Reference Lindblom1965), problem definition (Bardach Reference Bardach2009) and people skills (Mintrom Reference Mintrom2003). The term success is virtually absent but the broad implication is clear. Good or successful process (which for example, engages stakeholders in dialogue in order to pre-empt implementation problems and cultivate policy legitimacy) results in viable and successful programs. However, the nature of what constitutes successful policy process can prove just as contested as policy improvement or public value. For example, deliberation and public engagement have been criticised as little more than an exercise in the legitimation of dominant power (Shapiro Reference Shapiro and Macedo1999; Bishop and Davies Reference Bishop and Davis2002).

Fourthly, writings on the political aspects of policy have implications for what constitutes political success. Programmes may assist or frustrate leaders and governments in the pursuit of their agendas and aspirations. The nature of success is almost always implicit because conventions, constitutions and realpolitik are such that programs should be (or at least be portrayed as) in the public interest, as opposed to that of a party's electoral prospects, elite interests or individual career ambitions (Machiavelli 1971; Edelman 1977; Bachrach and Baratz Reference Bachrach and Baratz1970). This conceptualisation calls attention to evaluating policies in terms of their ability to produce benefits for particular political actors or groups.

Fifth, the explicit treatment of policy success is marginal. In an early article entitled ‘The Logic of “Policy” and Successful Policies’, Kerr (Reference Kerr1976) concentrated primarily on failure, perhaps understandably so, in the climate of mid-1970s political and economic turmoil. She argued that because policies can fail because they are inadequately implemented, or do not achieve their intended purpose or normative justification, they therefore can be said to succeed when they do not fail. Ingram and Mann (Reference Ingram and Mann1980) in an edited book entitled Why Policies Succeed or Fail were similarly pre-occupied with failure. Stuart Nagel (Reference Nagel, Ingram and Mann1980) defined success in its editorial introduction as the achievement of goals and the maximization of benefits minus costs. Bovens, 't Hart and Peters (Reference Bovens, 't Hart and Peters2001a) in their mammoth edited volume on success in governance likewise argue that success has two dimensions. The first is programmatic, ‘the effectiveness, efficiency and resilience of the specific policies being evaluated’ (Bovens, 't Hart and Peters Reference Bovens, 't Hart, Peters, Bovens, 't Hart and Peters2001b p. 20). The second is political, ‘the way policies and policy makers become evaluated in the political arena’ (Bovens, 't Hart and Peters Reference Bovens, 't Hart, Peters, Bovens, 't Hart and Peters2001b p. 20). Some writings mention non-failure (Bovens et al. Reference Bovens, 't Hart, Peters, Albæk, Busch, Dudley, Moran, Richardson, Bovens, 't Hart and Peters2001c), mixed success (O’Neill and Primus Reference O'Neill and Primus2005) and partial success (Pollack Reference Pollack2007), but these are typically ad hoc terms used to describe specific cases, and are not located within a broader framework that is able to capture the diversity of outcomes produced by policies. Some case studies define a programme's success according to the value judgements of the author being the standard. Others focus on standards such as goal achievement and benefits to key sectoral interests (see for example Schwartz Reference Schwartz2006, Hulme Reference Hulme, Moore, Bebbington and McCourt2007; Gupta and Saythe Reference Gupta and Sathye2009).

Finally, there is an extensive literature on failure, including policy fiascos (Dunleavy Reference Dunleavy1995; Bovens and 't Hart Reference Bovens and 't Hart1996), scandals (Tiffen Reference Tiffen1999; Thompson Reference Thompson2000), crises (Boin et al. Reference Boin, 't Hart, Stern and Sundelius2005) and disasters (Handmer and Dovers Reference Handmer and Dovers2007; McEntire Reference McEntire2007). However, the debates more or less mirror those dealing with aspects of success and its surrogates. Some, particularly those writings dealing with organisational pathologies and human error (e.g. Reason Reference Reason1997; Auerswald et al. Reference Auerswald, Branscomb, La Porte and Michel-Kerjan2007) and critical infrastructure breakdown tend to treat failure as an objective fact while others dealing with policy fiascos (e.g. Bovens and 't Hart Reference Bovens and 't Hart1996) focus heavily on competing constructions of goals to the point that failure is largely in the eye of the beholder. There is also little recognition of forms or degrees of failure, other than an implicit assumption (for example) that failures get worse as we move from emergencies and crises, to disasters and catastrophes.

Three Strands of Policy: The Basis for Succeeding and Failing

We need to comprehend different dimensions of policy in order to grasp the ways in which success and failure may be manifest within them. Also, tensions between them help explain some of the most interesting features and dynamics of policy. These differences can be found in process, programs and politics. They can overlap, but for analytical purposes can be treated separately.

Process is a traditional major concern of public policy analysts such as Lasswell (Reference Lasswell1956), Lindblom (Reference Lindblom1959, Reference Lindblom1965) and Easton (Reference Easton1953, Reference Lindblom1965), concerned with understanding the means by which societies could and should make collective choices in the public interest. The tradition continues today in works concerned with deliberative engagement (Gutmann and Thompson Reference Gutmann and Thompson2004; Gastil Reference Gastil2008), policy design (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1997), resolving controversies (Schön and Rein Reference Schön and Rein1994), solving problems (Bardach Reference Bardach2009) and the policy cycle (Althaus Bridgman and Davis Reference Althaus, Bridgman and Davis2007). In essence, what governments do is identify problems, examine potential policy alternatives, consult or not as the case may be, and take decisions. All such activities involve weighing the pros and cons of different choices such as who, when and how to consult and weighing the opportunities and risks of different policy solutions before taking a decision. Governments do process and they may succeed and/or fail in this realm.

Second, programs are what governments do (Rose Reference Rose1984: chapter 1). They give concrete form to the generalized intentions of statements of policy. For example, health policy involves dozens of programs dealing with everything from ante-natal care through preventive medicine to death. Programs combine in different ways the basic resources and tools of government – laws, public personnel, public expenditure, tax incentives and exhortation (Rose Reference Rose1984; Hood and Margetts Reference Hood and Margetts2007; Howlett Reference Howlett2010).

There is also politics. Some policy analysts prefer to keep politics at arms' length, because it is seen as a distraction from a rational form of policy analysis (Davidson Reference Davidson2005; Weimer and Vining Reference Weimer and Vining2005). Yet if we are to fully grasp the multi-dimensional nature of policy and what governments do, we need to recognize that programs have political repercussions. The choices of government (including timing of decisions and the symbolism of particular forms of action or inaction) have consequences for the reputation and electoral prospects of politicians and their capacity to manage political agendas. Many political analysts have examined the political repercussions of policy action and studies of political behaviour normally evaluate policies in terms of their relevance to winning votes. Governments do politics and they may prove successful and/or unsuccessful in this realm.

Defining Policy Success

Assumptions of what constitutes success take many forms. The foundationalist/scientific tradition, associated broadly with the rationalist strand of policy evaluation (Gupta Reference Gupta2001; Davidson Reference Davidson2005) leads us towards seeing success being a fact amenable to positive identification. For example, a government can aim to build a school and do so, or introduce a new tax and achieve this immediate goal. A different tradition is constructivist or discursive, emphasising the importance of interpretation and meaning (e.g. see Edelman Reference Edelman1988; Stone Reference Stone2002; Fischer Reference Fischer2003). The corollary of such approaches is that success is in the eye of the beholder, depending on factors such as a protagonist's values, beliefs and extent to which they are affected by the policy.

The approach here is a pragmatic combination of elements of these two approaches. The more tangible aspect of policy success relates to goal achievement. Hence, it is reasonable to suggest that a policy is successful insofar as it achieves the goals that proponents set out to achieve. However, given the positive connotations of the word success, only those who regard the original goal as desirable are likely to perceive its achievement in this way. The two approaches are combined in arriving at the following definition of policy success: A policy is successful if it achieves the goals that proponents set out to achieve and attracts no criticism of any significance and/or support is virtually universal.

The first advantage of this definition is that it recognizes that government can and sometimes does attain the goals it seeks in each of its three realms of policy. For example, a government can succeed in putting together an agreement in order to get a key decision or legislation approved. It can put in place a program with policy instruments that produce intended outputs and outcomes. Government may also succeed in producing a policy which boosts electoral fortunes.

Second, the definition also recognizes that not everyone will perceive government's achievements as successful. An extreme example is the statement of success by an architect of the US rendition program of interrogating terrorist suspects:

… the Rendition Program's goal was to protect America, and the rendered fighters delivered to Middle Eastern governments are now either dead or in places from which they cannot harm America. Mission accomplished, as the saying goes (Committee on Foreign Affairs 2007 p. 14).

Critics have viewed the policy instruments to achieve this (sic) success as a crime that ‘violates international law’ and ‘involved multiple human rights violations’, (Amnesty International 2008 p. 8).

Third, the definition reconciles, at least for heuristic purposes, the tension between the objective and dimensions of success. A definition that portrays success as purely a matter of interpretation will fail to capture the objective dimensions of goal attainment. Equally, a definition that portrays success purely as objective will fail to capture the subjective dimension of success. Therefore, both the objective and subjective dimensions of success need to be built into the definition rather than avoided or one included and the other excluded.

The Spectrum From Policy Success to Policy Failure

A spectrum makes it possible to differentiate intermediate categories between complete success or failure. The fivefold typology set out here does not deny the existence of difficult methodological issues which are best discussed elsewhere (see McConnell Reference McConnell2010).

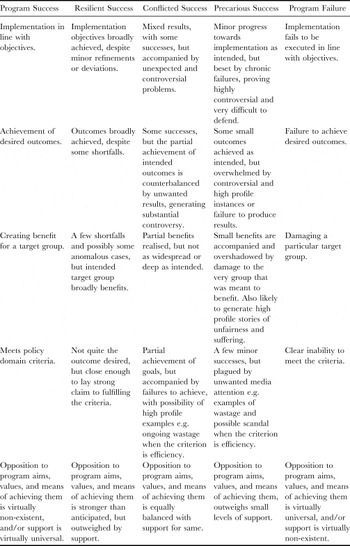

Table 1 Policy as Process: The Spectrum From Success to Failure

Success. Government does what it sets out to do and opposition is virtually non-existent and support near universal. Many matters of low politics and bureaucratic implementation of routine non-controversial issues will fall into the category of policy success as government achieving what it sets out to do. The absence of opposition and/or the existence of universal support may be hard to come by for many higher issues but it is still possible. For example, the Dutch system of dikes and dams prevents more than half the population, living below sea level, from drowning. For pragmatic purposes, I include in the outright success category, policies with minor delays or errors that can be corrected. The remaining measures or benchmarks of success can be identified across the process, program and political dimension of policy.

Process success rests first of all on the preservation of government's policy goals and instruments. For example, amendments to a government bill may facilitate the achievement of its goals rather than acting as a barrier. Second there is attaining legitimacy through a general acceptance that the policy has been produced through means that are legal and normal procedures, such as consultation with stakeholders. Third is the marshalling of a sustainable coalition of supporting interests and not just an ad hoc coalition securing the initial adoption of a policy (Patashnik Reference Patashnik2008). Fourth, success may stem from a process which encourages innovation, as in the case of Japan seeking to draw lessons from foreign experiences (see e.g. Goldfinch Reference Goldfinch2006).

Program success occurs if the measure that government adopts, including a stance of doing nothing, produces the results desired by government. Again, such outcomes can be captured in specific criteria such as implementation in a manner that produces the desired outcome. Benefiting a target group is a further criterion e.g. lowering the incidence of breast cancer in women over 60-years-old as a result of a new screening program. Satisfying criteria valued in a particular policy community is also a measure of success, for example, efficiency in public budgeting or secrecy on issues of national security.

Table 2 Policy as Program: The Spectrum From Success to Failure

Political success is the holy grail of political elites. One outcome of policies that provide significant political benefits and no problems to speak of is the enhancement of the reputation of the government, its leaders and its electoral prospects. A further criterion of no less importance is controlling the policy agenda by giving the impression of tackling a problem and marginalizing critics. For example, an urban riot can be defined as a ‘manageable’ law and order problem, as opposed to a ‘wicked problem’ involving long-term racial discrimination and urban deprivation. A final marker of political success is helping maintain broad values of government. For example, a clampdown on welfare fraud can contribute to a broader government agenda of reducing waste in public resources.

Resilient success. Opposition and shortcomings make this a second best outcome. However, as long as the measure is resilient it will not fail. In this situation, the level of opposition is more than government bargained for, but is nevertheless outweighed by levels of support. There are departures from one or more of the bundle of goals across the process, program and political realms.

Resilient process success means that government achieves its policy in broad terms notwithstanding small modifications and setbacks, for example, some opposition amendments are added to a bill. Resilient programs are survivors. Shortfalls, although not insignificant, do not undermine their core achievements. For example, a program in 90 countries to vaccinate against measles, mumps and rubella, has led to a substantial reduction in the incidence of the disease(s), despite exposing a small number of children to health risks. Insofar as political bargaining leads to compromise, politics must be prepared to settle for a second best outcome or else see their aims frustrated for a lack of agreement.

Conflicted success is a struggle for government. It achieves its policy making goals in some respects, but has to backtrack or make significant modifications along the way. Conflicted program successes are not what was intended. Proponents are troubled by substantial time delays, considerable target shortfalls, resource shortfalls, and communication failures. The program generates substantial controversy, galvanizing opposition parties and forcing government into a defence of core values and aims of the program, often coupled with program reviews and amendments.

Notwithstanding conflicts, political outcomes for government certainly have elements of success, even if accompanied by substantial controversy. Conflicted politics, as Lasswell (Reference Lasswell1971) recognized, is in part a product of competing values. Fischer's (Reference Fischer1995) work indicates that to achieve political stability requires resolving value conflicts by advocates of a program backtracking and accepting a modicum of conflicted success. In sum, conflicted successes allow government partially to achieve its goals, but it gets less than it bargained for in terms of outcomes, and more that it expected in terms of opposition.

Table 3 Policy as Politics: The Spectrum From Success to Failure

Precarious success operates on the edge of failure. Policies do exhibit small achievements, but departures from goals and levels of opposition outweigh small levels of support. They often amount to a pyrrhic victory for policymakers. Initially government does fulfill some of its policy making goals, but the costs of doing so become such that short-term success cannot be sustained.

Precarious program successes have some merits for proponents but outcomes fall well short of intentions and controversy is substantial, Even supporters seriously question the future of the policy. Precarious successes are often transient, en route to failure and termination. For example, the Child Support Agency in the UK, introduce in 1993, struggled, with its achievement in making ‘absent fathers pay’ coun tered by scandals, controversy, mismanagement and errors on a scale unprecedented for a government agency, leading to its closure in 2008 (Harlow Reference Harlow2002).

Precarious political successes are a substantial liability for government, even if there are small benefits. The political benefits of hanging onto a policy exist and are small (the benefit may be saving face and avoiding an admission of failure) but the costs are greater. The Nixon administration and the final years of the Vietnam war is arguably one such example.

Failure is the mirror image of success: A policy fails if it does not achieve the goals that proponents set out to achieve, and opposition is great and/or support is virtually non-existent. Failures can be issues of high media interest or low-level bureaucratic concerns. They include policies that have small successes overshadowed by large scale failures.

Process failures occur when the government is defeated in its ambition to enact legislation or make a decision. It may be a consequence of the ‘mobilization of bias’ (Bachrach and Baratz Reference Bachrach and Baratz1970) preventing government from doing what it thinks desirable or it may be due to the lack of a sufficient coalition of interests in order to realize governmental goals.

Program failures, in essence, not only fail to accomplish what they were intended to do but can also threaten the position of politicians and parties that sponsor failed programs. The British poll tax introduced in 1989 is an example. It was a local government tax levied on a per-capita basis, only marginally related to income. It produced high rates of non-collection, severe and costly administrative problems, and generated very visible political protests. The result was a rise in political costs and a loss in revenue. It was a significant contributing cost to Conservative MPs ejecting Margaret Thatcher from Downing Street and it was abandoned by her successor (Butler, Adonis and Travers 2004).

Contradictions Between Different Forms of Success

Locating policies in particular categories involves judgement rather than scientific precision (Wildavsky Reference Wildavsky1987 p. 3). Judgment is necessary because policy outcomes do not always have tidy results. Divergent outcomes may occur within one particular realm or there can be different outcomes across the process, program and political dimensions of policy. The result is that a policy can be much more successful in one realm than in another. Indeed, there is often a trade-off for policymakers between three realms of policy which at times sit uneasily alongside each other. Striving for success in one realm can mean sacrificing, intentionally or through lack of foresight, success in another. Such trade-offs and tensions are at the heart of the dynamics of public policy. Here I identity three key contradictions.

Successful Process vs. Unsuccessful Programs. A key concern of policymakers is to get decisions taken and legislation passed, using executive powers to steer the policymaking process towards such goals. These are process successes because government gets the policy it wants, in a legitimate manner and with the support of a coalition of interests. However, success at the process stage is no guarantee of success at the program stage. Policymaking without sufficient checks and balances is prone to producing flawed policies because goals and/or instruments have not been refined in order to produce workable policies through incremental bargaining (Lindblom Reference Lindblom1965; Braybrooke and Lindblom Reference Braybrooke and Lindblom1970), deliberative engagement (Carson and Martin Reference Carson and Martin1999; Gutmann and Thompson Reference Gutmann and Thompson2004) partisanship and plurality (Crick Reference Crick1962; Stoker Reference Stoker2006) and careful policy design (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1997). To paraphrase, government may win the battle (process) and lose the war (program).

Successful Politics vs. Unsuccessful Programs. A particular program may tilt towards the failure end of the spectrum, but produce successful political outcomes. Why would such outcomes occur? The answer liesin recognizing that political success sometimes necessitates programs that leave much to be desired in terms of tackling policy problems.

If we think about the three criteria for political success, this point is easier to make. One criterion is enhancing government or leaders' reputation/electoral prospects at the expense of programs. For example, the Anglo-French agreement to build the supersonic Concorde jet helped improve relations between Britain and France at a time in the 1960s when relations were otherwise strained, but after the Concorde became airborne it was not an economic success and airlines abandoned its use (Hall Reference Hall1982).

The second criterion is easing the business of governing through the agenda management of wicked issues (Rittel and Webber Reference Rittel and Webber1973; Head Reference Head2008). They are complex problems such as poverty and drug abuse with multiple causes and no clear solutions. Pragmatically, it is often easier for governments to deal with symptoms rather than tackle underlying social causes. Such policies have a strong symbolic or even placebo element (e.g. Stringer and Richardson Reference Stringer and Richardson1979). They demonstrate that government is trying to deal with the problem and responding to popular concerns can become the definition of success, whether or not the response effectively engages with a wicked problem.

Maintaining governance and policy trajectories often requires compromising of programs. A plausible argument could be put forward that the creation of the Department of Homeland Security in the US, proved far more successful for the Bush administration as evidence of its commitment to fight a War or Terror than in enhancing US security, because it created a super-agency which has done little to disturb long-established policy sub-systems (May, Sapotichne and Workman 2008).

Successful Programs vs. Unsuccessful Politics. Programs which produce the results desired by policy makers do not always result in political success. Well run programs can backfire on political desires. Efficiency drives, for example, can be executed successfully and desired outcomes achieved, but encroach on politics, thwarting leadership and/or electoral ambitions. Successful programs may even rebound on government agendas because of unintended consequences of an excess of success. The example of the EU's Common Agricultural Policy is a case in point. It was so successful by the mid-1980s in achieving the aim of self-sufficiency that it generated infamous ‘butter mountains’ and ‘wine lakes’.

Conclusion

When analysts assess the success or otherwise of a particular policy, they can invoke different criteria that lead to different conclusions. Career policy analysts may be more concerned with program design and program implementation issues. Political parties may be concerned with such issues but are also likely to enter into political realms. The world of policy analysis has lacked a framework that allows analysts to capture the diversity of outcomes from success to failure, in each of these three realms.

This paper has brought the three strands of policy analysis together. First, in recognizing that success and failure are not mutually exclusive, the article moves beyond the polarized portrayal of outcomes as success or failure. Second, it recognizes that there may be differences in success and failure in terms of processes, programs and policies. Third and finally, the framework allows for meaningful cross-sectoral and cross-policy comparison.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to three anonymous referees and the editors for their comments and guidance, and to Mark Bovens, Paul 't Hart, Mike Howlett and Dave Marsh for helping shape my thinking on this topic.