There is a consensus in the literature that women are disempowered socially and politically relative to men (Isaksson, Kotsadam and Nerman Reference Isaksson, Kotsadam and Nerman2014; Jayachandran Reference Jayachandran2015; Logan and Bratton Reference Logan and Bratton2006; Verba, Burns and Schlozman Reference Verba, Burns and Schlozman1997), which has important implications for the development of political knowledge and efficacy (Bleck and Michelitch Reference Bleck and Michelitch2018), as well as equal economic opportunities and development more generally (Duflo Reference Duflo2012). Depressed participation by women also results in an under-representation of their interests, especially where men and women have sharply divergent preferences (Gottlieb, Grossman and Robinson Reference Gottlieb, Grossman and Robinson2016). Attempts to improve the status of women have often failed, due to the strength and persistence of gender norms that disfavor them (Vaessen et al. Reference Vaessen2014) and the resulting backlash against interventions designed to reduce gender disparities (Clayton Reference Clayton2015; Gottlieb Reference Gottlieb2016). We identify a cultural practice – matrilineality – that instead exhibits a systematic positive association with women's political participation across sub-Saharan Africa. Using this practice as a lens through which to draw more general inferences, we demonstrate that its success in improving outcomes for women lies in its ability to sustain more progressive gender norms about their role in society. Unlike one-off programs aimed at raising the status of certain women, this communal practice shapes expectations about others’ beliefs and behaviors in a predictable way through intergenerational transmission.

Many scholars studying women's political engagement report that culture is an important element of explaining gendered outcomes. Previous studies have tied patriarchal traditions of male dominance in the private sphere to the tendency for women to be passive or submissive in the public sphere (Fish Reference Fish2002; Hudson, Bowen and Nielsen Reference Hudson, Bowen and Nielsen2015). Some explanations attribute women's passiveness in political deliberation to gendered cultural norms of interaction, which are even more prevalent when women are in the minority (Maltz and Borker Reference Maltz, Borker, Monaghan, Goodman and Robinson1982; Tannen Reference Tannen1990). Similar to our proposal that matrilineality influences women's public engagement through its ability to set expectations about how others will behave, Karpowitz, Mendelberg and Shaker (Reference Karpowitz, Mendelberg and Shaker2012) find that changing the decision rule in deliberation improves women's participation by changing the expectations of group members regarding who should be heard. The decision rule itself is a signal that creates common knowledge, which is necessary for coordinating around a behavioral norm (Chwe Reference Chwe2013). We similarly argue that matrilineality sends a signal that creates common knowledge about how children are being socialized into gender roles. One implication of these studies is that tweaking formal institutions might produce small improvements in the status of women, but sea changes will require a meaningful cultural shift.

We build on scholarship showing that culture affects gendered outcomes in the public sphere by examining why culture is so good at moderating women's prospects when other types of interventions have repeatedly failed. Decisions about whether to participate in civic and political life cannot be fully described using a cost–benefit analysis. Whether or not an individual is expected to participate also conditions that decision. Societies promote different beliefs about which individuals are welcome in the public sphere, and women are frequently thought to be unwelcome participants. This helps explain why decreasing the material costs of participation alone can often fail to improve outcomes for women: expectations that women do not belong in the public sphere remain. Culture prescribes such expectations about who can wield influence, and when. Drawing on a game-theoretic understanding of culture as a coordination equilibrium, we argue that a cultural practice such as matrilineality can set expectations about women's influence because it defines the social group within which these expectations apply, creates common knowledge about beliefs within that group, and sustains predictable norms over time through intergenerational transmission.

Before demonstrating how matrilineality as a cultural practice generates differential gender norms, we first show that it does help close the gender gap in participation on the African continent. About one-sixth of Africa's ethnic groups practice matrilineality, or the tracing of lineage through the female line; worldwide, it is practiced by about 13 per cent of ethnic groups (Murdock Reference Murdock1967). In this article, we provide the first large-N test of the relative civic and political behavior of men and women in matrilineal groups compared to patrilineal groups. We do so by matching ethnographic data on descent patterns from Murdock (Reference Murdock1967) with outcomes from public opinion polls in twenty-six African countries included in Afrobarometer V (2012). We find evidence that matrilineality is indeed associated with substantially better gender equality: the gender gaps in political engagement, political participation and civic participation are significantly smaller in matrilineal compared to patrilineal groups. These effects are robust to controlling for livestock dependence, the main historical driver of matrilineal kinship (Holden and Mace Reference Holden and Mace2003; Mace and Holden Reference Mace, Holden and Lee1999), as well as the related use of the plow, which has been shown to affect gender roles (Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn Reference Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn2013).

We then explain why matrilineality has this salutary effect on women. We analyze fine-grained individual-level data on matrilineal practices in Malawi, a country with heterogeneous kinship practices, and reject a prominent explanation in the literature: that matrilineal kinship empowers women by increasing their access to resources. We show that it is not just owning land that leads to better outcomes for women, but that the land must be inherited through the matriline in order to affect gender norms and political engagement. We also reject previous speculation that the effect is driven by differential investments in girls’ versus boys’ education. These null findings, along with qualitative insights from Malawi about the specific ways in which women's influence manifests across kinship groups, lead us to focus on the role that cultural norms and community-level socialization play in producing gender parity within matrilineal communities.

We use quantitative and qualitative data from Malawi to illustrate how culture matters. Using quantitative data, we first show that the unique practices prescribed by matrilineality – female inheritance of land and marital residence among the wife's kin – are plausible channels through which the gender gap in political participation is closing. In these analyses, we use historical ethnic kinship practices as an instrument for actual practices in order to address concerns about reverse causality, at least in the short term. Secondly, we show that these practices moderate both women's behaviors and community-wide norms about gender roles: they increase the likelihood that both women and men will hold more progressive gender attitudes. Finally, we show that the social component of the practice matters: only when a sufficient proportion of a village engages in matrilineal practices do beliefs and norms start to change; in contexts where most women practice matrilineal kinship, these effects spill over even to women who do not employ matrilineal cultural practices themselves.

While the quantitative data provides systematic evidence to support the argument that matrilineality is working, at least in part, through its cultural and institutional features, the qualitative data demonstrates how differential norms not only produce differential engagement, but also differential influence among women. From interviews across matrilineal and patrilineal communities, we uncover a key difference in how women engage in public life: in matrilineal communities, women exert more influence than men over both the selection of local leaders (chiefs) and issues related to land ownership and use. Both types of evidence from Malawi are consistent with the idea that the level and content of women's political engagement are conditional on expectations about women's role in society. If too few community members are part of a cultural system that values women's decision making, it will not be enough to simply increase women's engagement or participation.

Our findings make empirical and theoretical contributions to two literatures. First, we provide the most systematic evidence to date of a positive association between matrilineality and gendered civic and political participation, thus substantiating existing research, which argues that kinship systems shape gender dynamics. Much of the empirical literature testing this hypothesis is restricted to case studies that do not provide a direct comparison between matrilineal groups and comparable patrilineal groups (Schatz Reference Schatz2002). This has begun to change with recent studies of single-country cases that explicitly compare descent types and find that matrilineality is related to less spousal co-operation in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Lowes Reference Lowes2018) and greater political engagement in India (Brulé and Gaikwad Reference Brulé and Gaikwad2017). While Brulé and Gaikwad (Reference Brulé and Gaikwad2017) similarly attributes the effect of matrilineality on women's political engagement to norms, we extend this line of thinking by showing how certain modes of resource distribution and residence patterns may actually be endogenous to more gender-equal norms. Specifically, more progressive gender norms emerge when material and social resources are distributed to women in ways that ensure long-term access and create common knowledge among a sufficiently large proportion of households in the relevant social group.

Secondly, we contribute to the debate over the determinants of women's empowerment. Efforts to close the gender gap in political participation have attempted to both give women greater social and material resources and to change gender norms. The former suffers from what has been termed the ‘resource paradox’,Footnote 1 while the latter is constrained by the stickiness and slow-changing nature of norms. The success of matrilineality in improving women's prospects, we argue, is that it gives women access to social and material resources in a way that creates common expectations of greater female influence and can thus sustain more progressive gender roles. This has important implications for the design and implementation of policies created to empower women: while positive effects may be elusive in the short term, sustained access over time and space may generate more promising outcomes in the long term. These findings thus offer more optimistic conclusions for policy makers seeking to elevate the role of women in the public sphere. Allocating resources to women in a predictable and sustainable way may itself generate norm change, but only if those resources are distributed to women at a sufficiently large scale over a sufficiently long time. Only then will resource allocation be accompanied by commonly held expectations about the future provision of these resources and the more progressive gender roles that such continued access entails.

Matrilineal Kinship and its Implications for Women

Matrilineality refers to a kinship system in which descent is traced through the female line (matriline). At a minimum, kinship determines the lineage (mother's or father's) to which an individual belongs. Such belonging may have far-reaching implications for social, cultural, economic and political practices. Descent systems may influence the inheritance of property: land or other assets in matrilineal systems are passed from women to their daughters or from men to their sisters’ sons (Schneider and Gough Reference Schneider and Gough1961). In many, though not all, matrilineal societies, a married couple will reside in the wife's natal home with her mother, her mother's siblings, and her own sisters and their children (Davison Reference Davison1997; Schneider and Gough Reference Schneider and Gough1961).Footnote 2 Such residence patterns often imply labor obligations, because matrilineal families own the labor of the men who marry their daughters (Davison Reference Davison1997). Matrilineality may also influence the social systems of familial obligation, the gendered division of labor, political succession, social interactions between family members, and the distribution of authority (Schneider and Gough Reference Schneider and Gough1961).

Matrilineal descent systems exist in every region of the world, but are much less common than patrilineal systems. According to Murdock's (Reference Murdock1967) enumeration of all ethnocultural groups in the world, 13 per cent practice matrilineal descent, including 16 per cent of all societies in Africa (excluding Madagascar and the Sahara), 3 per cent in the circum-Mediterranean region (North Africa, Turkey, Caucasus, Semitic Near East), 1 per cent in East Eurasia (including Madagascar and islands in the Indian Ocean), 15 per cent in the insular Pacific (including Australia, Indonesia, Formosa, Philippines), 13 per cent in North America (indigenous societies to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec), and 8 per cent in South America (including Antilles, Yucatan, Central America). Matrilineal societies appear in all regions of Africa, although there is a particular concentration in the south-central region surrounding the Zambezi River (Davison Reference Davison1997), which is often referred to as the ‘matrilineal belt’ (Richards Reference Richards, Radcliffe-Brown and Daryll Forde1950).

It is not entirely clear why some groups are matrilineal and others are not, although some scholars claim that all African societies were originally matrilineal (Murdock Reference Murdock1959; Saidi Reference Saidi2010).Footnote 3 Because maternity is typically more certain than paternity, matrilineality may arise or persist in contexts where paternity is more uncertain (Holden, Sear and Mace Reference Holden, Sear and Mace2003). Under such conditions, societies will recognize patrilineal kinship only if paternal uncertainty can be reduced through the strict control of women's sexuality, or if the benefits of male inheritance outweigh that uncertainty. Holden and Mace (Reference Holden and Mace2003) argue that the latter often occurs with the introduction of cattle or other livestock.Footnote 4 Another mechanism of change in descent rules comes with the conquest of one group by another. For example, the Ngoni – fleeing early nineteenth century wars among communities in southern Africa – brought their patrilineal descent with them into parts of present-day Malawi, Mozambique and Zambia (Phiri Reference Phiri1983). Finally, matrilineal customs were challenged by both colonial and Christian ideologies, as well as the introduction of capitalist production and wage labor economies (Phiri Reference Phiri1983; Schatz Reference Schatz2002).

There are two opposing arguments in the literature about the relationship between matrilineality and women's empowerment. One argues that although lineage is traced through women, true decision-making authority within matrilineal societies nevertheless resides with men (Schlegel Reference Schlegel1972), typically manifest by the avunculate (authority of a maternal uncle). The main distinction between matrilineal and patrilineal systems of descent, according to this argument, is simply who a man controls – his wife and children in patrilineal societies, or his sisters and their children in matrilineal ones. Male authority within matrilineal societies thus gives rise to the ‘matrilineal puzzle’ (Richards Reference Richards, Radcliffe-Brown and Daryll Forde1950): matrilines have to maintain connections to their female members as bearers of future generations, but also to their male members who are the ‘decision makers’ (Schatz Reference Schatz2002). Thus men within matrilineal societies have divided allegiances between their own matriline, where they hold authority, and their wife's kin, to whom their children and labor belong. Given that men maintain control over women even within matrilineal systems, this line of argument suggests that women in matrilineal groups do not exercise more autonomy or authority than those in patrilineal groups.

Others have argued that matrilineality does improve women's welfare and relative power.Footnote 5 In some cases, women are empowered directly, through greater access to positions of power, such as village heads or clan leaders (Colson Reference Colson, Colson and Gluckman1951; Ntara Reference Ntara1977; Peters Reference Peters1997; Phiri and Vaughan Reference Phiri and Vaughan1977).Footnote 6 More typically though, women benefit from matrilineal descent and its associated practices even if men retain most decision-making power (Peters Reference Peters1997). For example, women in matrilineal societies have greater access to land and other assets, either through direct inheritance and ownership or through greater access to the possessions of the larger matriclan. This access gives women more direct control over land and other productive resources, which makes them less reliant on their husbands. In addition, women in matrilineal systems have continued kin support, either by living with or near their own family after marriage or through ongoing connections that are maintained by matrilineal kinship (Vaughan Reference Vaughan1987). Finally, women in matrilineal societies are likely to have greater intra-household bargaining power vis-à-vis their spouses (Lowes Reference Lowes2018). This is certainly true when a couple resides matrilocally and a woman is surrounded by her family. But it is also likely to be the case regardless of the residence location, because matrilineal women have a clearer exit option than patrilineal women, for whom bridewealth is generally paid, effectively limiting a woman's ability to return home after a failed marriage or her spouse's death (Schatz Reference Schatz2002; Schatz Reference Schatz2005).Footnote 7 As a result, marriage bonds tend to be weaker and divorce rates higher in matrilineal groups (Schatz Reference Schatz2002), which presumably gives women more power within the marriage (Phiri Reference Phiri1983). The security associated with matrilineal forms of descent thus translates into different patterns of behavior among women, including a greater preference for competition (Gneezy, Leonard and List Reference Gneezy, Leonard and List2009) and greater risk acceptance (Gong and Yang Reference Gong and C-L Yang2012).

Cross-National Data

To systematically determine the relationship between matrilineal kinship practices and gender differences in political participation, we combined Afrobarometer V survey data (2011–12) – for which we have measures of political and civic participation – with information from the Ethnographic Atlas (Murdock Reference Murdock1967), which provides details on kinship practices by ethnic group. The Afrobarometer includes data on 41,990 individuals across 511 ethnic groups and twenty-six countries,Footnote 8 while the Ethnographic Atlas includes information on social, cultural, political and economic characteristics of 1,267 ‘societies’ from around the world, including 551 in Africa. We matched ethnic groups across these two data sources using the coding decisions of previous scholars (for example, Nunn and Wantchekon Reference Nunn and Wantchekon2011) and multiple secondary sources (for example, Gordon Reference Gordon2005; US Center for World Mission 2010). Of the 511 ethnic groups included in Afrobarometer V, 386 were matched to an Ethnographic Atlas entry, representing 92 per cent of all Afrobarometer respondents who provided an ethnic identity.Footnote 9

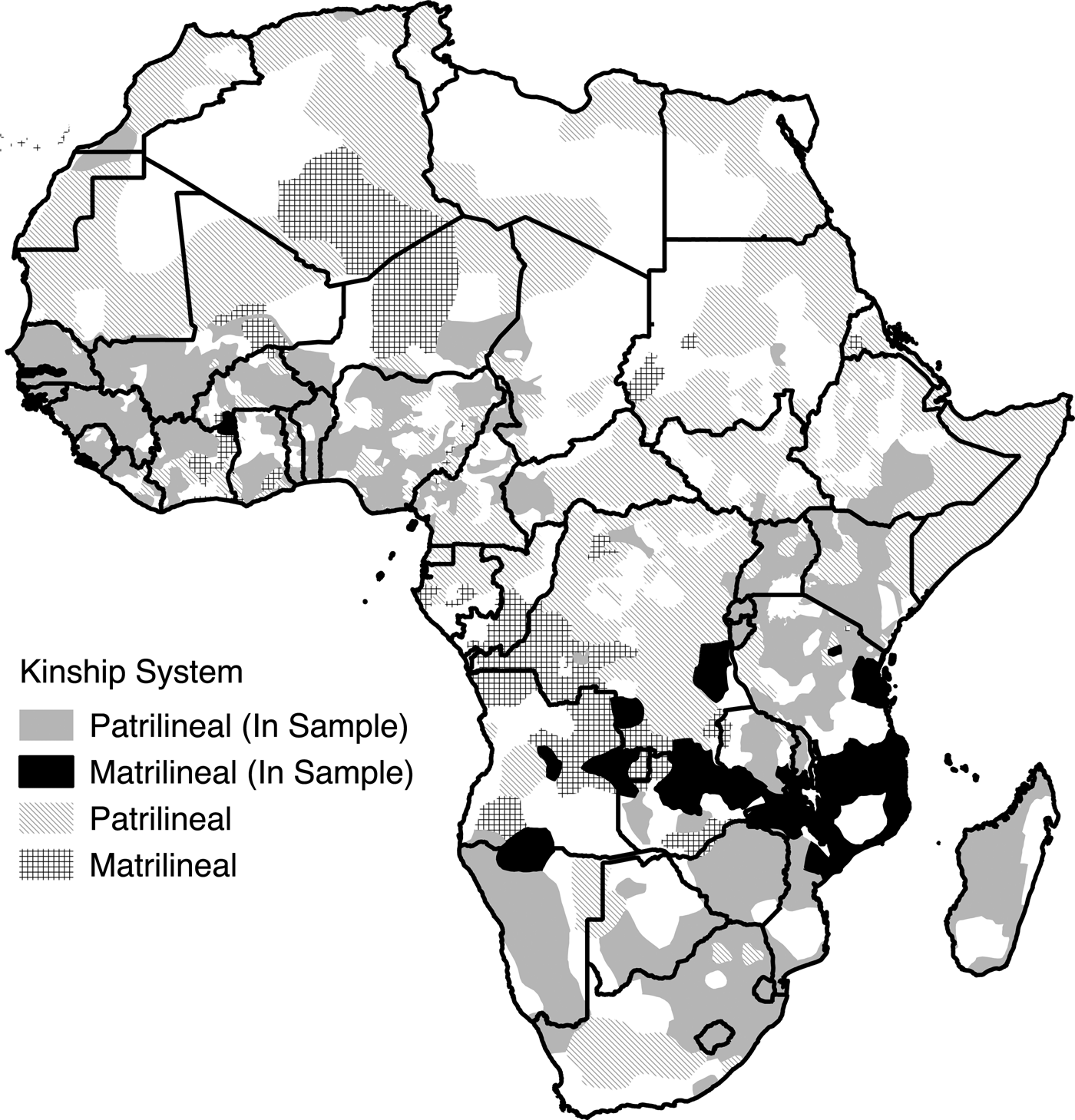

The presence of matrilineal descent is coded at the ethnic group level using an updated version of Murdock's Ethnographic Atlas (Gray Reference Gray1999). After merging Afrobarometer respondents with ethnic groups in the Ethnographic Atlas, we have data on the descent patterns of 37,198 individuals across 383 ethnic groups and twenty-six countries. We create a dichotomous measure of matrilineal descent that takes a value of 1 if the Ethnographic Atlas lists the group as matrilineal and a value of 0 if the group is coded as patrilineal, duolateral, quasi-lineages, ambilineal, bilateral or mixed. Based on these data, 10 per cent of ethnic groups (n = 37), representing 14 per cent of Afrobarometer respondents, traditionally practice matrilineal descent. Among non-matrilineal groups, most are patrilineal (76 per cent). Most respondents from matrilineal ethnic groups are located in countries within the matrilineal belt, including Malawi (75 per cent matrilineal), Mozambique (74 per cent matrilineal), Namibia (67 per cent matrilineal), Tanzania (22 per cent matrilineal) and Zambia (41 per cent matrilineal). However, several matrilineal ethnic groups are represented outside these countries, in Burkina Faso (Lobi), Niger (Asben Taureg), Sierra Leone (Sherbro) and Zimbabwe (Chikunda, Nyanja and Tonga), but in all of these countries less than 10 per cent of respondents belong to a matrilinieal group. Figure 1 shows the geographic distribution of kinship practices by ethnic group.

Figure 1. Ethnic groups in Africa by descent type

Note: geographic data for ethnic communities comes from Murdock (Reference Murdock1959) and data on kinship practices comes from Murdock (Reference Murdock1967).

The Afrobarometer V includes many questions on civic and political participation, which we group into three different indices – political engagement, political participation and civic participation – using an inverse covariance weighted approach (Anderson Reference Anderson2008). Prior to the construction of each index, the component variables were mean-centered and standardized, so the indices have a mean of 0. The thirteen component variables are summarized in Appendix Table A.1, and details on each question are presented in Appendix A.

Matrilineal Kinship and Gender Gaps in Political Engagement

We use a difference-in-differences analysis to assess whether the engagement and participation gaps between men and women are smaller in matrilineal ethnic groups compared to patrilineal and mixed-system ethnic groups.Footnote 10 The difference in differences is estimated using an interaction between the respondent's gender (female = 1) and whether or not he or she is from a matrilineal ethnic group (matrilineal = 1). Each model includes country fixed effects and ethnic group random effects. Formally, we fit the following mixed-effects linear (multilevel) regression model:

where y ij is the given dependent variable or outcome for respondent i from ethnic group j. female ij is an indicator for female, matrilineal ij is an indicator for whether i’s group j is matrilineal, and α i are country fixed effects.Footnote 11 To account for the nested nature of the data we include υ j, a random intercept for group j, and ε ij, which is the individual error term. Dependent variables are either indices or individual variables described in Appendix A. We present our results as figures rather than tables for ease of comprehension, but the coefficient on the difference-in-differences estimator β 3, as well as the p value associated with that coefficient, are included in each figure. Full regression tables are presented in Appendix C.

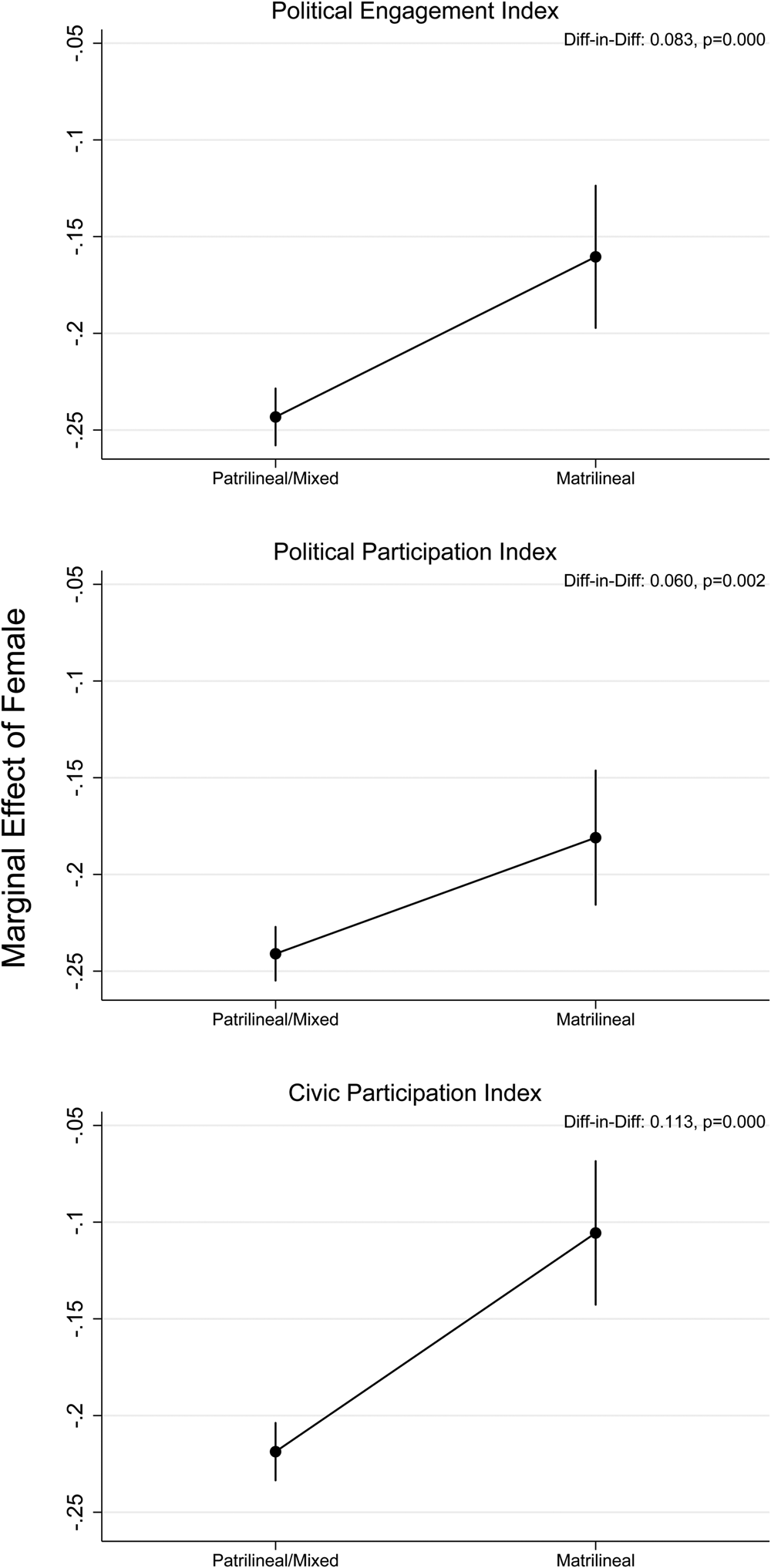

The main results of these estimations are presented in Figure 2, which shows the marginal effect of being a woman on rates of political engagement and participation by kinship system, and Appendix Table A.2.Footnote 12 For all three indices, the marginal effect is negative, meaning that women participate less than men. However, the size of this gap is significantly smaller for matrilineal groups across all three indices. The difference (between matrilineal and non-matrilineal societies) in the difference (between men and women) is statistically significant (p < 0.01) for all three indices.Footnote 13 While we cannot infer causation with respect to levels – whether men's or women's behavior is responsible for closing the gap – predicted values presented in Appendix Figure A.1 suggest that the differences are primarily due to women in matrilineal societies being more engaged and participatory than those in patrilineal and mixed societies. This suggests that matrilineality is associated with smaller gender gaps primarily because of the mobilization of matrilineal women. Taken together, these cross-sectional findings suggest that matrilineal kinship is systematically associated with more gender equality in political and civic engagement.Footnote 14

Figure 2. Gender gaps in political engagement by descent rule

Note: this figure plots the marginal effect of gender (female) on indices of political engagement by kinship system. Each outcome measure is an inverse covariance-weighted index of mean-centered and standardized constituent variables. These marginal effects are based on linear models presented in Appendix Table A.2, which include ethnic group random effects and country fixed effects.

How does Matrilineality Close the Gender Gap?

Our cross-national data analysis reveals that matrilineality is systematically related to women participating in public life at rates more equivalent to their male counterparts than women in patrilineal groups. While this is itself an important finding, its generalizability is limited given the relative rarity of the practice and its stickiness: it is not a policy that can simply be adopted. To better understand when we might expect to see these beneficial effects materialize elsewhere, we explore how matrilineality closes the gender gap in political participation. Here, we propose several plausible explanations for how matrilineal kinship exerts its salutary effects on gender equality. Each generates observable implications that we then test using qualitative and quantitative data from Malawi, a context with highly heterogeneous kinship practices.

Resources such as money and knowledge are known predictors of an individual's decision to participate in civic and political activities (Verba and Nie Reference Verba and Nie1972; Verba, Nie and Kim Reference Verba, Nie and Kim1987). Particularly in developing societies, women are less likely to have formal employment, more likely to be responsible for time-consuming household activities and are less likely to go to school. If women, on average, have fewer resources, this can explain why they engage in civic and political activities less than men. Matrilineality could then close the gender gap in participation if it distributes resources or education more equally across genders. We test this possible explanation by examining the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

If matrilineality is working through its conferral of resources (land) on women, then women with land should participate in politics more than those without land, irrespective of whether they inherit it through the matriline or acquire it through other means.

Hypothesis 2

If matrilineality is working through its more equal conferral of education across genders, then we should observe a smaller gender gap in education among daughters and sons in matrilineal families relative to patrilineal families.

Previous studies on developing nations largely conclude that the gender resource gap is not solely responsible for the gender gap in political participation (Desposato and Norrander Reference Desposato and Norrander2009; Isaksson, Kotsadam and Nerman Reference Isaksson, Kotsadam and Nerman2014).Footnote 15 We thus propose an alternative theory about how matrilineality not only confers greater resources on women, but does so in a way that supports more gender-equal norms about participation in the public sphere. To understand how matrilineal practices may have differentially shaped beliefs about gender roles, we first characterize gender roles as a solution to a co-ordination problem. We then show how features of matrilineality allow for new coordination equilibria to emerge.

Gender roles, and associated behaviors, have been described as a solution to a co-ordination problem (Lagerlöf Reference Lagerlöf2003; Mackie Reference Mackie1996). It is easiest to see this with respect to marriage. Because men and women are complementary in (heterosexual) marriage, girls will be socialized to fulfill a woman's role with the expectation that boys will be socialized to fulfill a complementary man's role. But communities must co-ordinate on gender socialization for reasons beyond marriage. Co-ordinated beliefs about each gender's role in decision making and influence in the public sphere is also important, as disparate views within society could lead to perceived improper behavior and resulting social sanctions. Avoiding such conflict requires a set of shared beliefs and norms. Conceiving of discriminatory gender norms as a type of solution to co-ordination problems helps explain why they are so stable despite potential inefficiencies.

This conception of gender norms as co-ordination equilibria also has implications for how more gender-equal norms might emerge. In the marriage example, for households to be sufficiently incentivized to socialize their daughters into progressive gender roles, they must expect that families of potential husbands are also socializing their sons in this way (Mackie Reference Mackie1996). Otherwise, parents who independently raise a daughter to conform to such a gender norm will put her at a disadvantage in the marriage market: either she will be unable to find a husband, or she will have a conflictual (and potentially violent) marriage. But expectations of how others will behave are sticky: they are set by observing prior behaviors (so there is path dependence) and by common knowledge of the context (so widely perceived shifts in underlying parameters can lead to changes in behavior). Compared to a society with stereotypical gender norms, the development of progressive gender norms requires a society with persistent cultural differences in order to set long-term expectations, and widely known and shared cultural distinctions to facilitate co-ordination at the level of the relevant group.

We argue that matrilineality closes the gender gap in political participation because it changes the gendered division of labor in affected societies and creates the conditions under which these differential behaviors become norms. First, when matrilineal kinship ties women to land ownership, they have more decision-making authority over that land, and when matrilocal customs mean that women live among their kin, this translates into greater personal security and better outside options if they leave their husbands. These features of matrilineality will lead to the socialization of girls who are more influential in intrahousehold decision making and have greater bargaining power with respect to their spouse (Lowes Reference Lowes2018). Both land ownership and residing in one's natal home also make it more likely that women will have influence in collective local decision making, including decisions about communal land use and local leadership. But even when matrilineality does not explicitly induce women to become more active in the public sphere, we expect that women's increased influence in intrahousehold and local decision making could spill over into the public sphere and formal political engagement. This expectation is based on existing theories of political efficacy, which demonstrate that practicing influence in one context can translate into political efficacy in another (Beaumont Reference Beaumont2011; Elden Reference Elden1981; Finkel Reference Finkel1985).

Secondly, two features of matrilineality – that it is practiced at the community level and that it is intergenerational – permit these economic and social resource advantages for women to translate into sticky progressive gender norms, and thus shape rates of women's political engagement in the future. When matrilineal kinship is practiced across an entire culture or community, common knowledge among members of that community sets shared expectations for how female children will wield influence in that community in the future. Because matrilineality is intergenerational, members of the community can anticipate how other families in that community will be socializing their children. Thus, we evaluate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3

If matrilineality is working through its conferral of more gender-equal norms, then we should observe more progressive gender norms in localities where a higher proportion of people is practicing matrilineality, and that women participate at higher rates in such communities, even if they do not personally follow matrilineal customs.

Data on Matrilineality in Malawi

We use quantitative and original qualitative data from Malawi, which exhibits considerable variation in kinship practices, to elucidate how and why matrilineality closes the gender gap in political participation. While the cross-sectional Murdock data allows us to make generalizations about which ethnic groups, on average, practice matrilineal descent, we know that descent rules translate into different practices across matrilineal communities, and that actual practices vary within ethnic communities. We therefore leverage individual-level data from Malawi on both the ownership of matrilineally inherited land and matrilocal residence to test the three potential mechanisms through which matrilineality affects the gender gap in participation.

Malawi is home to seven major ethnic groups – Chewa, Lomwe, Mang'anja, Ngoni, Sena, Tonga, Tumbuka and Yao – and many smaller ones. According to Murdock's (Reference Murdock1967) coding, the Chewa, Lomwe, Mang'anja, Sena, Tonga and Yao are matrilineal, while the Ngoni and Tumbuka are patrilineal. Many scholars and visitors have documented the striking implications of matrilineal descent systems in Malawi. Early European visitors to southern Malawi often noted the powerful roles of women, even if they did not attribute such observations to matrilineal descent patterns. For example, a missionary observing the Mang'anja noted that he was ‘struck with the regard which the men had for the women, whose position seemed to be in no way inferior to that of the men’ and that ‘it was at times amusing to see the deference which the men sometimes paid the women’ (Rowley Reference Rowley1867). Peters (Reference Peters1997) recounts her interactions with female chiefs in southern Malawi, and the women who surround them, as well as the marginality of men in many of her interactions. Marriages are more ephemeral and divorce more likely in matrilineal groups in Malawi (Peters Reference Peters1997; Schatz Reference Schatz2002), both because women maintain access to land after divorce and because bride prices are less often paid among matrilineal groups, meaning that women are not bound by repayment in the case of divorce (Kerr Reference Kerr2005).

Quantitative Data from Malawi

To more systematically test our hypotheses about the relationship between matrilineal practices and the gender gap in participation, we leverage the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH) (Kohler et al. Reference Kohler and Watkins2015), a six-wave panel study of over 4,000 Malawians living in three districts – Balaka (southern region), Mchinji (central region) and Rumphi (northern region) – between 1998 and 2012.Footnote 16 While MLSFH data are primarily focused on health and sexual behaviors, some rounds include information on personal land ownership and inheritance, post-marital residence patterns and attitudes about female autonomy. We utilize the 2004 round of survey data because it is the only year in which land ownership was measured at the individual rather than the household level. This round of data includes information from 3,261 respondents, 55 per cent of whom are women who have been married; the remainder are (or were) their husbands.

Because the MLSFH data were collected in only three regions, only five of the country's seven main ethnic groups are represented in the data, which comprise 34 per cent Chewa, 5 per cent Lomwe, 6 per cent Ngoni (1 per cent in the North and 5 per cent in the Center and South), 32 per cent Tumbuka and 23 per cent Yao. Of these five ethnic groups, Murdock (Reference Murdock1967) coded the Chewa, Lomwe, and Yao as matrilineal and the Ngoni and Tumbuka as patrilineal. However, a closer evaluation of these Malawian groups nicely illustrates the subtlety that is not possible with large, cross-national dataset such as Murdock's Ethnographic Atlas. For example, Murdock codes the Tumbuka as patrilineal, but they only became patrilineal in the early 1800s after being conquered by the patrilineal Ngoni from southern Africa (Kishindo Reference Kishindo2002). As a result, many Tumbuka continued to practice matrilineal descent and matrilocal residence until at least the 1930s (Davison Reference Davison1997), and even today there exist remnants of matrilineal practices (Berge et al. Reference Berge, Kambewa, Munthali and Wiig2014; Kerr Reference Kerr2005). Some matrilineal ethnic groups in Malawi have also adopted patrilineal practices. In particular, many matrilineal Chewa of the northern and western parts of the central region practice patrilocality (Berge et al. Reference Berge, Kambewa, Munthali and Wiig2014), which some attribute to colonial rule, capitalism and Christianity, all of which favor a nuclear understanding of family with a male head of household (Phiri Reference Phiri1983). The Ngoni also present a complicated case. The Mpezeni Ngoni who invaded and settled in northern Malawi and eastern Zambia mostly maintained their patrilineal practices, while the Maseko Ngoni who settled in central and southern Malawi were more likely to adopt the matrilineal practices of the groups among whom they settled (Berge et al. Reference Berge, Kambewa, Munthali and Wiig2014; Davison Reference Davison1997). For this reason, Ibik (Reference Ibik and Allott1970) codes the Ngoni outside northern Malawi as matrilineal, which tracks with our data as well: the Maseko Ngoni in our sample inherit land through the matriline and live matrilocally at rates similar to matrilineal ethnic groups. For all these reasons, it is important that our data allow us to exploit individual-level variation in kinship practices.

The MLSFH round four data include information about where respondents lived after marriage (in the wife's home village, in the husband's home village or another village), and whether a respondent personally owned land and how he or she received that land (inherited from own kin, inherited from spouse's kin, purchased or received from a chief).Footnote 17 Thus we can evaluate the degree to which kinship systems at the ethnic group level affect matrilineal inheritance of land and matrilocal residence in practice. First, men and women report similar rates of land ownership among matrilineal groups (Chewa, Lomwe, Yao, and Mapezo Ngoni: 91 per cent vs. 89 per cent), while men report owning land at a significantly higher rate than women among both patrilineal groups, the Tumbuka (91 per cent vs. 52 per cent) and the Mpezeni Ngoni (83 per cent vs. 31 per cent). This difference is driven by land inherited through the matriline: women in matrilineal and patrilineal ethnic groups are equally likely to have received land from the chief (16 per cent vs. 18 per cent) or bought land (4 per cent vs. 5 per cent). Secondly, in terms of residence after marriage, a majority of the matrilineal Yao (69 per cent) and Lomwe (57 per cent) practice matrilocal residence, but only 41 per cent of the Mapezo Ngoni and 25 per cent of the Chewa do so. This is consistent with previous studies, which found that many Chewa in Mchinji practice patrilocality (Berge et al. Reference Berge, Kambewa, Munthali and Wiig2014). For the patrilineal Tumbuka and Mpezeni Ngoni, only 8 per cent and 11 per cent, respectively, of respondents practice matrilocal residence.

We assess the effects of these matrilineal practices on three outcomes. First, we focus on a locally meaningful form of political and civic participation: attending a meeting at the chief's place of residence in the last year.Footnote 18 Across the whole sample, 61 per cent of female respondents reported that they had attended such a meeting, while 85 per cent of men had done so. Secondly, to evaluate gender differences in educational investment, we calculate the average years of education for boy and girl children within each household, and take the difference between the two as a measure of differential investment.Footnote 19 Thirdly, we utilize the variable from the MLSFH data that most closely measures gender norms: beliefs about the circumstances under which a woman is justified in leaving her husband. As Lowes (Reference Lowes2018) has shown, when women can more easily leave their husbands or have more outside options, this affects critical outcomes such as the rate of gender violence and the degree of investment in children. Similarly, Bleck and Michelitch (Reference Bleck and Michelitch2018) show that female autonomy in rural Mali is associated with the formation of political knowledge and opinions among women. Because the culturally sanctioned subjugation of wives by their husbands is a key feature of patriarchal gender norms, we consider the extent to which women are justified in leaving their husbands as a measure of progressive gender norms, which we construct using the respondent's likelihood of saying that a woman is justified in leaving her husband under a variety of circumstances. Respondents were asked whether ‘it is proper for a wife to leave her husband’ if he does not support her and the children financially (47 per cent of women answered affirmatively vs. 43 per cent of men), he beats her frequently (78 per cent vs. 63 per cent), he is sexually unfaithful (83 per cent vs. 87 per cent), she thinks he might be infected with AIDS (29 per cent vs. 22 per cent), she thinks he might have a different sexually transmitted disease (31 per cent vs. 31 per cent), he does not allow her to use family planning (27 per cent vs. 25 per cent), he cannot provide her with children (50 per cent vs. 28 per cent), or he does not sexually satisfy her (42 per cent vs. 37 per cent). We combined these eight individual answers, which are positively correlated with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.63, into a composite index using an inverse covariance-weighted method (Anderson Reference Anderson2008).

Qualitative Data from Malawi

While our quantitative data from Malawi allow us to assess hypotheses about why women participate more in matrilineal societies, we turn to qualitative data to better understand what women's participation looks like – what local issues they are involved in, and whether they wield influence in critical matters in the public sphere. In July and August 2017, we thus conducted fieldwork in several matrilineal and patrilineal communities to uncover some of the specific ways in which women's influence manifests differentially across kinship groups. In collaboration with the Institute for Public Opinion and Research of Zomba, Malawi, we conducted interviews with forty women and ten village headmen across five different ethnic communities. The five ethnic communities were chosen to maximize variation in kinship practices, and included the matrilineal Chewa, Yao and Maseko Ngoni and the patrilineal Tumbuka and Mpezeni Ngoni. To identify respondents, we first selected districts associated with each ethnic community – Dowa for the Chewa, Mangochi for the Yao, Ntcheu for the Maseko Ngoni, Rumphi for the Tumbuka, and Mzimba for the Mpezeni Ngoni. We then selected two enumeration areas within each district with near-homogenous populations of their respective ethnic majorities based on 2008 census data. Experienced Malawian research assistants traveled to each of the ten selected enumeration areas and visited one village per area. In each village, the research assistant used a structured list of questions to interview the village headmen and two female residents. A list of the questions asked is included in Appendix K. All interviews were professionally translated and transcribed.

The Practice of Matrilineality and Gender Norms

In this section, we first test our three hypotheses regarding how matrilineal practices close the gender gap in participation using survey data from across Malawi. We then use qualitative data from matrilineal and patrilineal communities in Malawi to illustrate how women's influence manifests differently across groups.

Quantitative Results

Matrilineality is like a ‘bundled treatment’, to borrow a term from experimental methods, in that it does many things at once. This makes it difficult to determine through which pathway(s) its effects are materializing. Individual-level data on women and their households in Malawi allow us to examine several competing explanations for why we observe the effects on the gender gap in the cross-national data. Unlike the Afrobarometer data, which contains only an individual's ethnic affiliation, the MLSFH data also provide individual-level indicators of whether a woman has inherited land through the matriline and whether married couples reside with her extended family. This additional information allows us to more precisely test the relationship between matrilineal practices and normative beliefs, and to exploit variation in the extent to which these practices are observed across villages. Given that our theory of norm formation centers around expectations of the desirability and legitimacy of women's participation in the community, this community-level variation is key.

Before testing the three different mechanisms through which matrilineal practices may close the gender gap in political participation, we first demonstrate that variation in actual practices is indeed associated with rates of political participation and gender-related norms at the individual level. To do so, we follow a similar empirical strategy employed in the cross-national analyses, by interacting gender with individual-level matrilineal land inheritance or matrilocal residence. However, unlike ethnic group membership and kinship patterns, which are generally exogenous at the individual level, individual-level practices of land inheritance and residency may be affected by our outcome variables – for example, households with more female political participation or stronger support for gender equality may be more likely to implement the practices associated with matrilineal kinship. Therefore, we also employ a two-stage estimation strategy that uses an individual's ethnicity as an instrument for land inheritance or marital residence.Footnote 20 In both estimation strategies, we cluster standard errors by village.

Figure 3 presents the results of the standard ordinary least squares regression in the left panels, and the estimation that uses ethnicity as an instrument in the right panels. Regression estimates are also presented in Appendix Table A.10. Both matrilineal land inheritance and matrilocal residence are associated with a reduced gender gap in the likelihood of attending a chief's meeting. The closing of the gender gap is driven by both an increased likelihood of women attending and a reduced likelihood of men attending, as shown in the predicted outcomes in Appendix Figures A.10 and A.11.

Figure 3. Matrilineal practices and the gender gap in local political participation (a) Matrilineal land inheritance and the gender gap in local political participation; (b) Matrilocal residence and the gender gap in local political participation

Note: these figures plot the marginal effect of gender (female) on the likelihood of having attended a chief's meeting, by whether or not a woman inherited land through her matriline (or, in the case of men, whether his wife inherited land from her matriline) in the top panel, and by whether or not the respondent resides matrilocally in the bottom panel. The outcome is a dichotomous measure of whether or not the respondent attended a meeting at the chief's place in the previous year. These marginal effects are based on models presented in Appendix Table A.10. In the instrumental variable analyses, a respondent's ethnic group kinship practice is used an instrument for the individual's actual practice.

We next evaluate whether matrilineal land inheritance and matrilocal residence also shape gender norms. Figure 4 shows the effects of land (left panel) and residence (right panel), both instrumented by ethnic group membership, on support for progressive gender norms by gender.Footnote 21 We show predicted outcomes rather than the marginal effects of gender, because we anticipate that matrilineality will shift gender norms among both men and women, making the gap a less relevant measure. Figure 4 shows that, consistent with our expectations, both men and women express much more progressive gender attitudes when a woman in the household has inherited land matrilineally and when they reside with the wife's kin.

Figure 4. Matrilineal practices and gender norms by gender

Note: this figure plots the predicted degree to which a respondent agrees that women are justified in leaving their husbands by matrilineal practices (matrilineal land inheritance and matriliocal residence) instrumented by ethnic group. The outcome is an inverse covariance-weighted index of eight constituent variables, each of which asks whether a wife would be justified in leaving her husband under a different circumstance. These marginal effects are based on models presented in Appendix Table A.11. Predictions based on non-instrumented models are shown in Figure A.12.

These results provide direct evidence that women's land inheritance and matrilocal residence – both of which are strongly driven by matrilineal kinship – close the gender gap in political participation and promote gender-equal norms. We now investigate why.

First, we compare the effect of land inheritance through the matriline to other means of inheriting land among women. If Hypothesis 1 is correct, we should observe that women's personal ownership of land is associated with increased political participation and stronger support for progressive gender norms, regardless of the source of that land. Figure 5 plots the effects of matrilineal land inheritance and land ownership through other means (purchase or the chief) relative to having no land, on both attending a meeting with the chief (left panel) and progressive gender norms (right panel). The results, also presented in Appendix Table A.12, suggest that while land ownership originating from matrilineal inheritance is positively associated with both outcomes, land ownership through other means does not confer the same benefits. Thus, contrary to Hypothesis 1, matrilineal kinship is not associated with greater gender parity in political participation simply because it increases land ownership among women.

Figure 5. Effects of land ownership among women

Note: this figure plots the effect of matrilineal land inheritance and land acquired through other means, relative to owning no land, on both the likelihood of attending a meeting with the chief and on gender attitudes. The sample includes only women. The outcomes are a dichotomous measure of whether or not the respondent reported having attended a meeting at the chief's place in the previous year, and an inverse covariance-weighted index of eight variables focused on justifiable reasons to leave a husband. These marginal effects are based on models presented in Appendix Table A.12.

Secondly, we evaluate the association between matrilineal practices and educational investments in daughters versus sons. If increased educational investments in girls relative to boys in matrilineal societies were driving the improved gender parity in political participation and gender-related norms, as stipulated in Hypothesis 2, we should observe a reduced gender gap in children's educational investment among women practicing matrilineality. Instead, Figure 6 and Appendix Table A.13 show no differential investment. If anything, the pattern is in the opposite direction; this may be because the sons of matrilineal women require education for their livelihood, as they will not inherit land from their family. Regardless of the reason, it is clear that there is not increased investment in daughters’ education relative to sons, and thus differential educational investment cannot explain how matrilineality promotes women's political participation and progressive gender norms.

Figure 6. Matrilineal practices and gendered educational investment

Note: this figure plots the predicted difference in daughters’ and sons’ years of education within a single household by matrilineal practices (matrilineal land inheritance and matriliocal residence) instrumented by ethnic group. The outcome is the difference between the average number of years of education for daughters minus the average number of years of education for sons for each woman in the sample. These predictions are based on models presented in Appendix Table A.13. Predictions based on non-instrumented models are shown in Appendix Figure A.13.

Finally, we evaluate Hypothesis 3 – the expectation that, if matrilineality increases women's political participation by conferring more gender-equal norms, we should observe more progressive gender norms in localities where a higher proportion of people are practicing matrilineality, and that these positive effects of a high concentration of matrilineality should extend even to those who do not practice matrilineal kinship themselves. To do so, we construct a village-level measure of the proportion of respondents that inherited land through the matriline, as well as the proportion that resides matrilocally. We then interact these community-level variables with the individual-level indicators of matrilineal practice and the gender of the respondent, clustering standard errors by village.Footnote 22 Appendix Tables A.14 and A.16 present the results of the triple interaction for both matrilineal land inheritance and matrilocality for our measures of political participation and norms, respectively.

For the outcome of political participation, we find that the interaction between gender and the concentration of matrilineal practice has a strong and significant effect. This indicates that the concentration of matrilineal land inheritance and matrilocality within the village substantially closes the gender gap in participation, independent of any direct effect the practice has on individuals. While the direct effect of the practice is still positive, it is no longer statistically significant at conventional levels. In Figure 7, we directly illustrate the existence of spillovers – or the effect of local matrilineality on women who do not themselves engage in the practice. Here, we exclude women who individually engage in matrilineal practices (inherited land or matrilocality) to more explicitly observe what happens to those who do not. The graphs show that moving from a low to high concentration of matrilineal practice closes the gender gap in participation by about 20 percentage points. Figure 7 also shows how the marginal effects change with the level of concentration. We find that a non-linear interaction model is a superior fit to the data: the marginal effect of being a patrilineal female is about the same in low to middling levels of matrilineal concentration, but when the concentration level crosses a certain threshold, the marginal effect jumps considerably.Footnote 23 This is consistent with a coordination story in which a difference in behavior (women participating relatively more) is only observed when women can expect a sufficient number of others in the community to engage in a practice that advantages women.

Figure 7. Indirect effect of village concentration of matrilineal practices on attendance at a chief meeting

Note: this figure illustrates the indirect effect of living among households that practice matrilineality on women who do not themselves The lighter bars along the bottom depict the distribution of observations along the moderating variable; the darker bars depict the proportion of patrilineal-practicing women relative to men. The top row of graphs depicts matrilineal land inheritance; the bottom row, matrilocal residence. The bars along the bottom depict the distribution of observations along the moderating variable; the colored bars depict the proportion of patrilineal-practicing women relative to men. The L, M, and H, stand for Low, Middle, and High terciles of the moderating variable. These predictions are based on models presented in Appendix Table A.15.

We now examine how the concentration of matrilineality affects norms. In prior analyses of our gender progressive norms index, matrilineality was associated with more progressive gender attitudes among both men and women. Figure 8 plots the predicted degree to which a respondent agrees that women are justified in leaving their husbands from the triple interaction analysis in Table A.16. The figure clearly shows that the difference between women who do and do not practice matrilineality is not statistically significant, but that the norms among all types of individuals change dramatically as one moves from a low to a higher concentration of matrilineal practice.

Figure 8. Village concentration of matrilineal practices and progressive gender norms

Note: this figure plots the predicted degree to which a respondent agrees that women are justified in leaving their husbands by gender and across different village concentrations of matrilineal practice. We disaggregate the predicted probability for women who do and do not practice matrilineality at the individual level (matrilineal land inheritance and matriliocal residence). These predicted probabilities are based on estimates presented in Table A.16.

One concern with this measure of gender norms is that it captures individual attitudes about gender and, only less directly, what one expects others to do. We thus also consider an outcome that is a harder test of the theory because it involves a very costly action: divorce. If matrilineality were only operating through a direct channel, then we should only see it affect women who practice it directly. However, if matrilineality indeed changes norms about the position of women in a community, then a patrilineal woman in a largely matrilineal community may still feel more secure getting divorced because she would face fewer social sanctions. We test this in Appendix Table A.17 and Figure A.14 and find that while there is a strong association between individual-level matrilineal practice and divorce, there is also a significant positive relationship between the concentration of matrilineality and divorce among patrilineal women.

Qualitative Data

In our qualitative interviews with women and village chiefs from matrilineal and patrilineal communities, we sought to better understand how kinship patterns could have such important implications for women in public life. Analyses in the previous section demonstrate that gendered attitudes and actions are indeed different in these communities. Both the justification for leaving one's husband and the decision to divorce are shown to be moderated, at least in part, by the practices of others in the community. In this way, popular practices define ‘normal’ behavior and thus dictate reactions to (or social sanctions associated with) one's own beliefs or actions. Our qualitative data provides further evidence of how these differences in norms manifest as differences in civic and political behavior. In otherwise patriarchal societies, it is not normal for women to participate in decision making about land and chief selection. It is thus consistent with our argument that differential norms about gender roles in matrilineal areas would help support such deviations in women's public behavior.

Interestingly, direct questions about whether women and men had differential access to local meetings and chiefs revealed no variation. Across both types of kinship groups, our respondents were about equally likely to say that women could approach the chief, and that women participate in meetings as much as men. However, questions about how community decisions are made reveal a much more substantial difference across groups: women have much more influence in matrilineal groups compared to patrilineal ones. The key difference is that women in matrilineal communities have more influence than men over decisions about land use and allocation and chief selection.

In half of the matrilineal villages in the sample, all or most respondents said women had more influence than men over issues related to land or farming; no respondent in a patrilineal village said this. For instance, one chief in a matrilineal village said, ‘[on] issues concerning land, I approach elder women, and ask them being elder people, they know more about the land, who was using it and how has been inherited for the past years. So they give advice and address the issue’.Footnote 24 This control over land is also echoed in within-household decision making: most respondents in matrilineal communities reported that women decide what is grown on and sold from their land, whereas only three of the ten respondents in each patrilineal district said this was the case (sometimes because the woman was a widow or from a family practicing matrilineality).

A male village chief also said women are influential in chief selection: ‘There were no men, when choosing a person to become a village head, we only recommend elder women of the village because women knows very well the behavior of every person in a village.’Footnote 25 When asked why women have little influence in a patrilineal village, one woman said it is because ‘women have a lack of understanding of each other’,Footnote 26 which may suggest a lack of autonomy to invest in female relationships or a lack of opportunity to act collectively.

It is notable that, in our data, five out of ten chiefs are female. Village chiefs in Malawi are of primary importance to villagers’ welfare, given their role as gatekeeper between the government and the village – providing information about the village to the government and distributing benefits from the government to the village (Eggen Reference Eggen2011). And importantly, they are also responsible for allocating customary land among village members. Being of the same gender as the chief likely affects the rate and productivity of interactions with this crucial local leader. Thus the presence of a female village head could, in part, be driving the higher likelihood of chief contact by women in matrilineal societies if matrilineal groups are more likely to have female heads. Four of the five female heads in our sample are in matrilineal communities.Footnote 27 Indeed, the breakdown of female chiefs by region accord with the expectation that they would be more prominent in the more matrilineal southern regions: only 3 per cent of households in the North have female village heads, while this is true of 8 per cent in the central region and 18 per cent in the South.Footnote 28

That women can have real influence in community-level decision making in typically patriarchal societies suggests a real difference in norms with respect to gender roles. Patriarchal gender norms dictate that men should be community leaders and make decisions governing the well-being of the community. This is also true of decisions at the household level among husband and wife. So while matrilineality usually co-exists with patriarchy, we have seen that the more gender progressive behaviors and beliefs associated with matrilineal practice can erode the dominance of the patriarchy through women's greater access to positions of power.

Conclusion

Motivated by the persistent gender gap in civic and political participation across the African continent, we examine whether an underexplored but plausible determinant of female empowerment – matrilineality – systematically improves political and civic participation for women relative to men. In so doing, we additionally extend the existing research finding that ‘culture matters’ in producing gendered outcomes by highlighting the generalizable features of a cultural practice that can create and sustain more progressive gender norms, thus closing gender gaps in public engagement. In the first instance, we combine ethnographic data on kinship systems with public opinion data from the Afrobarometer, generating evidence that matrilineality is strongly and significantly associated with narrower gender gaps in political engagement, political participation and civic participation. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic, cross-national study that produces evidence that matrilineal kinship practices have notable positive effects on the status of women. The empirical setup, comparing women to men within their own group, allows us to control for the many ethnicity-specific covariates that would otherwise make it difficult to isolate the effects of a cultural practice.

We then exploit additional quantitative and qualitative data to highlight the mechanisms through which this specific cultural practice is working in Malawi. Our theory, for which we find evidence, is quite general. We show that matrilineality works because it sets expectations about women's influence within a defined social group – members of the matrilineal ethnic group – and that those expectations are stable over time because of the intergenerational transmission of the practice. In particular, we only see more gender progressive behavior within communities where a sufficient proportion of households practice matrilineality. We also disconfirm a competing hypothesis that resources alone are sufficient to generate more gender-equal behavior: women who own land but did not inherit it through the matriline are no different from those without land on our outcomes of interest.

These findings have implications for interventions or policies to close the gender gap in political participation or otherwise empower women. Pure resource-based policies such as establishing micro-credit groups for women or subsidizing girls’ schooling have sometimes failed because the one-time positive economic shock is stymied by asymmetric gender norms that counteract it (Anderson and Genicot Reference Anderson and Genicot2014; Gottlieb Reference Gottlieb2016). Changing norms via formal rules, such as quotas for women in parliament or extending property rights to women, may not fully address the myriad informal barriers that prevent women from realizing the full benefits of greater formal access (Clayton Reference Clayton2015).Footnote 29 A key problem with understanding the impact of such short-term resource-based interventions or norms-based policies to address gender inequality is that changes may take generations to materialize. While most social science research does not afford us the ability to study such long-term impacts, matrilineality, an old and relatively stable institution, helps address this problem. We can conceive of matrilineality as a long-term program that consistently gives women greater access to resources (material and social), and thereby increases everyone's expectations of female access to these resources. We have shown that such long-term access, unlike many short-term programs that confer similar material resources, has the potential to shift gender norms with favorable impacts on women.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RIKYVD, and online appendices at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000650

Author ORCIDs

Amanda Lea Robinson, 0000-0002-8315-7753; Jessica Gottlieb, 0000-0002-1204-8496.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Miguel Eusse, Mwayi Masumbu and Hannah Swila for excellent research assistance, and the Institute for Public Opinion and Research in Zomba, Malawi for logistical support. Earlier versions of this article benefited from feedback at the 2016 Yale University Politics of Gender and Sexuality in Africa Symposium, the 2016 Working Group in African Political Economy annual meeting, and the University of Michigan African Politics reading group (especially Nahomi Ichino and Anne Pitcher). We are particularly grateful to Crystal Biruk for pointing us to the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH) data, and to Alick Bwanali, Amanda Clayton, Kim Yi Dionne, Guy Grossman, Michael Kevane, Sara Lowes and Jessica Preece for their insightful comments. Fieldwork for this project was funded by the Department of Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the Ohio State University (OSU), and was approved by the OSU Institutional Review Board (2017E0344). The data, replication instructions and data codebooks can be found at https://dx.doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RIKYVD (Robinson and Gottlieb Reference Robinson and Gottlieb2019).