Arabic has a long history of contact with languages outside the Middle East (Lapidus, Reference Lapidus2015; Beg, Reference Beg1979). In Asia, the spread of Arabic began with the trade network that connected the Middle East with South Asia, South-East, East Asia and East Africa from the fifth century. It intensified with the rise of Islam from the seventh century onwards (Morgan & Reid, Reference Morgan and Reid2010; Azirah & Leitner, Reference Azirah, Leitner, Leitner, Hashim and Wolf2016). In this paper we investigate the impact of Arabic on today's English in the context of Asian Englishes. More specifically we ask if the contact of Arabic with English in Asia has led to the creation of an Arabic-Islamic layer of English in countries that have a majority or a significant minority of Muslims. Would such a layer add a new dimension to the texture of English and be integrative across national Englishes? Or would it be divisive inside individual countries? In order to explore such issues we created a corpus of Arabic loanwords in Asian Englishes. Such a database will contribute to a better coverage of the impact of Arabic in dictionaries and to the study of English as a (multiple) national, regional and global language.

The impact of Arabic loanwords

Some years ago Randolph Quirk and Gabriele Stein (1990) gave some illustrations of Standard (British) English in print media such as The Straits Times (Singapore), The Australian and The Times of India to show that it set an internationally valid norm. That claim was disputed then and it has been shown to ignore local and regional layers in English today (Kachru, Reference Kachru1990). Example (1) taken from the Malaysian New Straits Times illustrates the issue.

-

(1) He [Deputy Prime Minister, Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin] said such programmes would educate Muslims on the reasons behind Islamic rules and the hikmah (good tidings) they bring … He called upon Islamic academicians and ulama to intensify efforts to restore the country's position as the centre of knowledge for Ahli Sunnah Wal Jamaah teachings … the government was prepared to cooperate with and help Islamic scholars and Islamic non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to carry out more dakwah (preaching of Islam) and tarbiyyah (give advice based on Islamic teachings) programmes. (New Straits Times, 21 May 2014)

Conventions in orthography, morphology and grammar in example (1) are the same as Standard English. What makes this passage look Malaysian (and/or Islamic) are the Arabic loanwords hikmah ‘good tidings’, ulama ‘clerics’, dakwah ‘preaching of Islam’, tarbiyyah ‘giving Islamic advice’, and Ahli Sunnah Wal Jamaah, which is the name of an Islamic organization in Great Britain, Australia, or Malaysia. The lexemes signal the complex localization of English in a multi-religious nation. They cast an Islamic perspective on the story that is moderated by English paraphrases for the sake of foreign or unacquainted readers.

Methodology

Despite the long history of contact between Arabic and English (Durkin, Reference Durkin2014; Cannon, Reference Cannon1994), there is an acute lack of contemporary data and an insufficient lexicographic coverage (Azirah & Leitner Reference Azirah and Leitner2011a; Reference Azirah, Leitner, Leitner, Hashim and Wolf2016). Some words like fatwa ‘Islamic legal ruling by an expert’, jihad and a few others have become known globally but words like hikmah, dakwah and tarbiyyah in example (1) or solat ‘prayers’, sembahyang ‘to pray, to worship’ and iftar ‘breaking the fast’ have remained local.

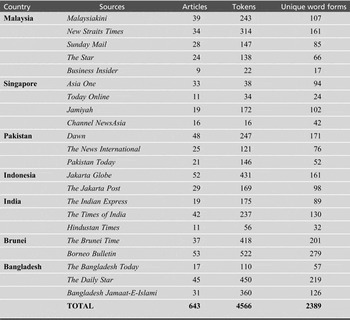

In order to address this gap and to explore the contemporary impact of Arabic on Asian varieties of English we have pursued a multi-method approach. For one, we have collected a special purpose corpus (see Bowker & Pearson, Reference Bowker and Pearson2003; Leitner, Reference Leitner, Johansson and Stenström1991), the Arabic Corpus of Asian English (ACAE) that contains data from Asian countries with a majority of Muslims or, at least, a strong Islamic segment (Azirah & Leitner, Reference Azirah and Leitner2011b). The countries we concentrated on were former anglophone colonies, i.e. Malaysia, Brunei, Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. We added data from Indonesia, the largest Islamic country worldwide, despite its non-anglophone history, and from anglophone Singapore, which is related to Malaysia and the region historically and in many other ways. ACAE consists of data from mainstream online English newspapers, blogs and some political speeches. It primarily focuses on the formal, public language (newspapers and blogs). It also has some of the formal spoken medium (speeches). As for its size, ACAE has 306,048 word forms and 25,418 word types from 643 texts (see Table 1). Like any special-purpose corpus ACAE's first-hand data open up research avenues that can but need not be pursued in a general purpose corpus (Bowker & Pearson Reference Bowker and Pearson2003).

Table 1: A breakdown of the ACAE data

The program we used for analysis, Wordsmith 7.0, automatically generates an alphabetic and frequency wordlist, which we went through manually to arrive at a glossary of Arabic loanwords (with raw frequency data). To broaden our dataset, we used that glossary for searches in the very large Corpus of Global Web-based English (GloWbE) (Davies Reference Davies2013) with 1.9 billion words from 20 native and second-language anglophone countries (excluding Indonesia). We need to point out that there are considerable differences between sampling in ACAE and GloWbE. ACAE excludes pamphlets, sermons, Islamic encyclopedia and discussion forums that we deemed limited to a more specific readership of Muslims or an Islam-expert segment of English users. Such data are well represented in GloWbE.

Loanwords of Arabic descent in English are rare in general. But there are some loanwords that figure prominently in the top 500 words of ACAE (see Table 2) and some are highly frequent in GLoWbE (see Table 2). It is not difficult even in a small corpus like ACAE to identify some ‘global’ words like Islam, Muslim, or Allah on the one hand and some ‘local-regional’ ones like hudud, haji or sukuk on the other. Yet, neither ACAE nor GLoWbE can claim their frequencies adequately represent the texture of English in general or that of specific varieties.

Table 2: Arabic loans in the first 500 most frequent word forms in ACAE

Before we begin discussing our data we must mention some constraints on the use of Arabic loanwords by non-Muslims that exist in Malaysia and Brunei but may do elsewhere. Some Arabic-Islamic words are said to express concepts that can only be used by Muslims. In Malaysia, for instance, a decree was issued by the National Fatwa Council against the use of 40 islamic words ‘in any form, version or translation in any language or for use in any publicity material in any medium, including print, electronic and any form that could insult the sanctity of Islam’ (Predeep, Reference Predeep2014). The list includes fatwa, kiblat, mufti, Ka'bah, Allah, Firman Allah, hadith, baitullah, kalimah al syahadah, haji, kiblat, imam and azan. Brunei has forbidden the use of 19 Islamic words by non-Muslims, i.e. ‘azan [call for prayer]; baitullah [house of god]; Al Quran; Allah; fatwa; Firman Allah …’ (Sulok Tawie, 2014). While violations of the misuse of these words may be hard to define in legal terms and court cases have been rare, the use of these Islamic words in the context of another religion could be punishable. After a lengthy court case that was regularly and widely covered in the Malaysian and international press (e.g. The Guardian, 23/04/2014), the Malaysian High Court ruled against the Catholic weekly Herald as it used the word Allah in publications outside the two states of Sarawak and Sabah in Borneo where it was permitted as Christian communities had traditionally used Allah to refer to the Christian God.

In the following sections we focus on the uses of loan expressions in the seven countries surveyed in ACAE and GloWbE. We comment on their meanings and uses in selected semantic fields. The fields chosen, i.e. political Islam, religion, law, and finances, appear to be highly prominent in ACAE's data and GloWbE. In this discussion we also comment on a few pragmatic or discourse expressions which illustrate the fact that Arabic loans have also entered spoken English (in Malaysia and presumably in other countries).

The domain of law

In the multi-religious nations under investigation the differences in legal systems influence the likelihood of Arabic words occurring in the public domain. In countries with an Islamic majority and a colonial past, there can be competing systems, i.e. the Common Law, if they were former British colonies, and the Shariah law. A retired Chief Justice of Malaysia, Abdul Mohamad Hamid (Reference Hamid2008), argued indeed that the Common Law and Islamic Law have approximated each other in this situation:

Islamic law was only applicable to Muslims and, even then, restricted only to matrimonial matters, inheritance and in regard to the administration of mosques, waqf and the like. Criminal law, based on the English common law as codified in India, was already in place. The only offences that the States are allowed to legislate were and are offences ‘against the precepts of Islam’ and only applicable to Muslims. Similarly, the English law of Contract, law of Evidence and others, which had been codified in India, were introduced in Malaysia. At that time, Islamic banking, Islamic finance and ‘takaful’ were unheard of.

In a situation with competitive legal systems, Abdul Mohamad Hamid (Reference Hamid2008) said that ‘we reminded ourselves that we were interpreting the words “precepts of Islam” used in the Constitution and not issuing a “fatwa” on the “precepts of Islam”’. So up to the present time Shariah has only applied to matrimony, inheritance, conversion, child education. For the rest, a modified Common Law system is in place. But there remain competing cases such as the prosecution of Malay men cross-dressing as women, which the Court of Appeal found unconstitutional in 2014.

The likelihood of legal loanwords appearing in the public domain is confined to Shariah. But religious debates are also carried out in academic contexts and are diffused in multiple ways by religious or political leaders or the press. A key area is gender relations where the term khalwat is common in Malaysia for one type of infringement. Of Arabic origin khalwat literally means ‘solitude’ and refers to a period of 42 days during which someone searches solitude to reflect upon his relation to God. This use is reminiscent of a similar period of retirement in Christianity, which is still partly observed in the Catholic Church. The long period of six weeks has gradually eroded to a few days in Islamic countries (see example (2)). In (3) khalwat refers to a place name which may well originally have been a location traditionally used for khalwat. The dominant sense in MalE describes a situation between members of the opposite sex which may suggest a deeper intimacy than is allowed for unmarried couples and counts as a crime and a sin (see (4)). GloWbE's data has 49 tokens of khalwat of which 36 come from Malaysia, 9 from Pakistan, three from Kenya and one from Tanzania. Here are some illustrations:

-

(2) However, temporary solitude (Khalwat) of a few days is necessary for the Mubtadee (beginner in Tasawwuf). (GloWbE Corpus, Pakistan English)

-

(3) After visiting the Khalwat and Lalpura ruby mining areas the valley was safe enough for the author. (GloWbE, Kenian English)

-

(4) A POPULAR film actress was detained by a religious department team after she was suspected of committing khalwat (being in close proximity) with a man at a condominium … (‘Popular actress caught for khalwat’, The Star, 16 Dec 2014)

The Malaysian Enactment No 3 of 1964 of the Administration of Muslim Law Enactment of 1963 lists in Section XI punishable offences. Section 115 defines khalwat as a situation in which men or women who are ‘found in retirement with and in suspicious proximity to any man [or woman]’ (other than those he or she cannot marry by Muslim law) ‘shall be guilty of an offence’ and be punished by imprisonment, a fine or both. The 1988 version uses more Arabic words as they seem to better express the dominant and sole valid interpretation:

Any female [or male] person who, in any place, found living with or cohabiting with or in retirement with or hiding with any male person who is not her muhram [close relatives such as parents, and siblings] other than her spouse that would arouse suspicion that they commit maksiat [sin], shall be guilty of an offence of khalwat and shall be liable.

The Malaysian Department of Islamic affairs (JAIS) has a special police force that searches for people in khalwat (see example (5)). Not all Islamic countries apply such laws. In Pakistan, India and Bangladesh atrocities have been reported in cases of agreed sex but the concept of khalwat is absent.

-

(5) Fifty-two unmarried Muslim couples face charges of sexual misconduct and possible jail terms after being caught alone in hotel rooms by Malaysia's Islamic morality police … The detained… are expected to be charged with ‘khalwat,’ or ‘close proximity’. (The Star, 4 Jan, 2010)

Money and finance

There is a considerable amount of research on Islamic financial services (Obaidullah Reference Obaidullah2005) and one can often find technical Arabic terms. Such loans describe best what conforms to Shariah. Shariah-compliant is a frequent technical hybrid for products that follow Shariah regulations. Several Islamic banking institutions such as the Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance (IIBI) in London and the First Community Bank in Nairobi have issued glossaries of finance and banking terms (see Institute of Islamic Banking and Insurance n.d.; First Community Bank (Nairobi). n.d.). The glossaries are for the general banking public and experts alike. From a linguistic angle, they act as codifiers right across the Islamic finance sector and diffuse the knowledge of words and of Islamic banking practices.

Yet, the press in the countries sampled only uses very few financial terms from Arabic; the most prominent ones are takaful and sukuk. The first, known as ‘Islamic insurance’, designates ‘a form of insurance based on the Quranic principle of mutual assistance (ta'awuni). Structured as a charitable collective pool of funds …’ (IIBI, n.d.). Sukuk is a financial certificate and is similar to a conventional bond with the difference that it is asset-backed; It ‘represents proportionate beneficial ownership’ (IIBI, n.d.) and is used to, for example, replace housing loans by a lease-back system. An interesting pattern for takaful can be found in GloWbE. There is a total of 898 tokens of takaful and only 23 come from the inner-circle varieties of English (Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand). India has 31, Sri Lanka 19, Pakistan 26 and Bangladesh has 20 tokens. In African countries one finds 19 tokens. In Asia, the vast majority of tokens comes from Malaysia. Most of the tokens in Pakistani English refer to the ‘takaful industry’ in the Middle East and Sri Lanka and do not refer to a Pakistani industry at all. Sukuk is more frequent with 1,112 tokens. It is more widely spread; 148 tokens come from Western countries and 134 from Western-type second-language countries, i.e. Singapore and Hong Kong. As for the rest, once again the majority of tokens is from Malaysia (771).

In academic contexts words like takaful are discussed in relation to a number of other Islamic concepts, as is illustrated here:

-

(6) Under Shariah law, conventional insurance is prohibited due to the elements of gharar, maysir and riba in its implementation. Instead, takaful was introduced … In order to ensure that takaful operates within Shariah law, a takaful contract is developed based on the concept of tabarru [‘donation’] … The types of contracts that can potentially be used include those created based on the principles of hibah, waqf, sadaqah or … (Asmak & Shamsiah, Reference Asmak, Shamsiah, Rawami, Kattani and Zhang2010)

Some Arabic words are even quoted in the German press. A national paper, Die Welt, carried a report on Islamic banking:

-

(7) „Riba”, „Gharar” und „Maysir” heißen die größten Sünden, Zins, Spekulation und Glücksspiel. Das Zinsverbot ist die populärste Idee. Dass Geld aus sich heraus wächst, ohne dass eine Ware gehandelt wird, schien dem Propheten frevelhaft. (Beutelsbacher, Reference Beutelsbacher2015)

The article titled ‘Allah's failed bankers’ explains that the ‘biggest sins., according to the Quran, are interest (riba), speculation (gharar) and gambling (maysir). If the trend towards Islamic business becomes more vigorous, more Arabic loans will enter the international public domain.

Pragmatics and discourse conventions

There is a range of Arabic expressions that relate to conversational routines etc. We will begin with the observation that it is hard to identify the sole influence of Arabic as, for instance, the Malay culture and Islamic practices are close to one another. One could argue that what we find is both Islamic-Arabic and Islamic-Malay and similar statements could be made about languages in Pakistan, Bangladesh or Brunei.

‘Peace be upon him’ or pbuh is a routine formula of reverence across the Islamic world. It is used after the names of ‘prophet’, ‘Mohammad’, ‘the Prophet of Islam’, and even (the prophet) Jesus. The acronyms SWA and SWT perform similar functions; all express something like sallaallah alaihi wa salam ‘may Allah's peace and blessings be upon him’. There are some differences in meaning. SWT, for instance, is Subhanahu Wa Ta'ala ‘the most glorified, the most high’. In GloWbE there are 11,332 tokens of pbuh, more than half of which (5,987) come from Pakistan. Religion-based formulae do occasionally occur in international contexts like in the talk by the Malaysian judge quoted above and can be found in local academic contexts. The opening of the Prime Minister of Malaysia Najib Razak's 2016 budget is an example of such Islamic-Malay and Arabic rhetoric.:

-

(8) … Mr. Speaker Sir, In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious and the Most

Merciful. All praise is due to Allah, the Lord of the A'lamin. Wa bihi Nastai'n. Praise be to Allahu Ta'ala who created the seven heavens and earth and who also created a state of darkness into the light. Peace be upon the Prophet Muhammad, the chosen Messenger who rejects falsehood, and safeguards rights and truths. (PM Najib Razak, 2015)

The opening of the lecture by the Malaysian High Court judge Abdul Mohamad Hamid, in contrast, is not marked by such rhetoric, while Arabic loans like fiqh (‘jurisprudence’), ibadah (‘worship’), hudud, masqasid (‘purposes’), mazhabs (‘sect’), takaful (‘joint guarantee’), sukuk (‘islamic bonds’), fatwa, aqidah (‘creed’), ulama, ummah (‘nation’), shari'ah and (the Prophet) s.a.w occur throughout his lecture. But during the closing part the speaker appeals to Allah:

-

(9) [Opening] I thought that my visit to Harvard last year to attend my daughter's graduation was going to be my first and last visit here. However, thanks to Professor Baber Johansen … This is the greatest gift for my retirement.

[Ending the lecture] Let us pray to Allah that we live long enough to see the development, if it happens. (Abdul, Reference Hamid2008)

The opening address to an international audience by Prime Minister of Malaysia Najib Razak shows how the solemn Arabic-Islamic conventions gradually shade into the less formal conventions that are widely perceived as ‘Western’ in Asia:

-

(10) Bismillahirrahmanirrahim [In the name of Allah] Your Royal Highness, your excellencies, ladies and gentlemen, distinguished guests. I am delighted to join all of you today at the very first conference of the Global Movement of the Moderates … We have a saying in Malaysia, tak kenal maka tak cinta [Malay], which means ‘we can't love what we don't know’ – and it is my sincere hope that over the next few days we will come to both know and love each other better … (Razak, 2012)

The Global Movement of the Moderates is a gathering of ‘moderate’ (or anti-terrorist) Islamic nations worldwide. The opening begins with the invocation of Allah, greetings of attendants in the order of ranks in Malaysia and a personal welcome by the Prime Minister. There follows a more colloquial wish for the success of this gathering signaled by code-switching into Malay, which is then translated and turned into a wish for the success of the conference.

Pragmatic and discourse conventions such as ones in the examples (8)-(10) can generally be used to reach out to audiences for particular political purposes. Arabic loans seem to abound with Islamic and Malay audiences. At this point one should add that a number of ordinary evaluative words in Malay and probably other languages can be replaced by phrases that include an appeal to Allah in colloquial speech. Thus, there are Insha Allah for ‘ok’, Subhana Alla for ‘wow’, Subhana Alla for ‘thanks’, and Assalamualaikum Warahmatullah as a greeting create harmony and agreement.

Conclusion

This paper has looked at the contemporary contact of Arabic with English in South and South-East Asia and has found it to be pervasive. We compiled the Arabic Corpus of Asian English (ACAE), which is small in relation to what it is meant to ‘represent’. Its glossary could be used for searches in the much larger Corpus of Global Web-based English (GloWbE) so that a picture of the use of some words on their global or regional-local use could emerge.

Arabic loanwords were seen to fulfil functions well beyond the ‘filling of lexical gaps’. They signal the power of interpretation over issues concerning religion, law, finances, or the norms governing daily life. They define the context of interpretation, express and create an Islamic perspective. They have political and ideological power. In Malaysia they are increasingly used by politicians and public figures to show the (real or pretended) strength of their belief in Islam and that they ‘live an Islamic life’. The use of Arabic words in such contexts becomes a political instrument to gain credibility with and the votes of the traditional Malays. Similar conclusions can be drawn for English in Brunei, Pakistan and Bangladesh, and in minority situations in Singapore or Great Britain. There they may not have that same ideological force and may be seen as ‘quoted’ or translated concepts to express a level of (reported) authenticity. Arabic loans were often found to be paraphrased, or an English wording was made more specific with an Arabic loan. Paraphrase and translation make texts accessible to non-Muslims and to those Muslims whose understanding would be limited without removing the Arabic-Islamic reading of the text.

There was no evidence in ACAE or in GLoWbE that words would be used outside the semantic field they have come from apart from adapting their reference to suit the contexts of modern societies. The use of halal, for instance, has gone far beyond food and is used for what could be seen as matters of privacy such as sexual practices. Non-literal uses such as humour or abrasiveness and semantic developments away from the source did not occur in our data.

As most of the Arabic loanwords in ACAE are characteristics of the Islamic segment of English speakers in epicentres of English, they may have a divisive function unless their use and meaning transcend ethnic and religious boundaries (Azirah & Leitner, Reference Azirah and Leitner2011a). But divisiveness is only one consequence. Integration is another, as they signal the pan-regional impact of Islam and its linguistic expression in Arabic. They add another, under-researched regional dimension to the texture of English today.

AZIRAH HASHIM is a professor in the English Language Department, Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, executive director of the Asia-Europe Institute and director for the Centre for ASEAN Regionalism at University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur. Her research interests include language contact in the region, language and law, English as a lingua franca in ASEAN and higher education in ASEAN. She is a Humboldt fellow and was at the Free University of Berlin in 2009–2010. Email: azirahh@um.edu.my

AZIRAH HASHIM is a professor in the English Language Department, Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, executive director of the Asia-Europe Institute and director for the Centre for ASEAN Regionalism at University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur. Her research interests include language contact in the region, language and law, English as a lingua franca in ASEAN and higher education in ASEAN. She is a Humboldt fellow and was at the Free University of Berlin in 2009–2010. Email: azirahh@um.edu.my

GERHARD LEITNER is an emeritus professor of English linguistics. He has published on varieties of English, English worldwide, language contact and its history, and educational language policies (in Australia, South-East Asia and India). He has written on the sociology of language of broadcast media (history of BBC English, Australian public broadcast media, German radio), and on Australian Aborigines and the history of Australia. He is an honorary member of the Australian Association of the Humanities, research professor (Australia) and a visiting professor in Malaysia and Singapore.

GERHARD LEITNER is an emeritus professor of English linguistics. He has published on varieties of English, English worldwide, language contact and its history, and educational language policies (in Australia, South-East Asia and India). He has written on the sociology of language of broadcast media (history of BBC English, Australian public broadcast media, German radio), and on Australian Aborigines and the history of Australia. He is an honorary member of the Australian Association of the Humanities, research professor (Australia) and a visiting professor in Malaysia and Singapore.

MOHAMMED H. AL AQAD is a PhD candidate in linguistics at the Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. He has an MA in legal translation from the same faculty. Currently, Al Aqad is research assistant at the Centre for ASEAN Regionalism University of Malaya (CARUM). His research interests include linguistics, translation studies, legal discourse and forensic linguistics.

MOHAMMED H. AL AQAD is a PhD candidate in linguistics at the Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. He has an MA in legal translation from the same faculty. Currently, Al Aqad is research assistant at the Centre for ASEAN Regionalism University of Malaya (CARUM). His research interests include linguistics, translation studies, legal discourse and forensic linguistics.