How do moral intuitions change with age? The study of human morality has been a part of psychology since its inception (James, Reference James1891), and at the beginning of the 20th century, this study was linked to the acquisition of social norms by the person in a given society (Durkheim, 1912/Reference Durkheim and Martínez Arancón2014; Freud, 1930/Reference Freud and López Ballesteros2010). Contrary to this vision of morality, as a process in which the individual takes a passive role, John Dewey pointed out the importance of rational and autonomous reflection as a way to improve values and principles of the individual and therefore his/her adaptability to the social environment (Dewey & Tufts, Reference Dewey and Tufts1908). This primordial role of rationality and the passage from a heteronomous morality to a moral autonomy was taken up by Piaget years later in his theory of the moral development of the child (Piaget, 1932/Reference Piaget and Gabain1965) and also by Kohlberg (Kohlberg & Kramer, Reference Kohlberg and Kramer1969). According to Kohlberg, human morality, reduced to a single concept of justice, evolves along with the age of the person through different stages from a heteronomous morality typical of the child towards an increasingly autonomous and decontextualized morality, typical of the young adult. However, despite the fact that none of these models included adults over 25, since Kohlberg himself has defended that moral maturity does not change after the age of 25, (Kohlberg & Kramer, Reference Kohlberg and Kramer1969), other authors have given clues that moral development is a life-long process. For example, Gibbs (Reference Gibbs2009) proposed a model of moral development throughout a person’s life that would go through phases of standard moral development and later existential development, although these phases would not be associated with specific ages. In addition, the direct relationship between age and moral reasoning has been evidenced in various studies, in which both a positive (Armon & Dawson, Reference Armon and Dawson1997) and a curvilinear (Bielby & Papalia, Reference Bielby and Papalia1975; Pratt et al., Reference Pratt, Diessner, Hunsberger, Pancer and Savoy1991) relationship have been found between both variables.

Do these relationships stand when considering more than the rational part of human morality? Moral reasoning has a limited scope in explaining moral behavior, for example, highly moralistic people do not necessarily have high cognitive abilities (Hardy & Carlo, Reference Hardy and Carlo2011). Furthermore, rationalist theoretical approaches assume an individualistic-based morality in which only elements of justice, care, and personal freedom, characteristic of Western, mostly liberal societies, are considered. Therefore, in order to investigate how individual morality changes with age, it may be preferable to choose broader theoretical models that include group-based moral elements present in all human societies.

Theoretical models including group moral dimensions in the study of human morality, have been surging in the last decades (Haidt & Joseph, Reference Haidt and Joseph2004; Shweder et al., Reference Shweder, Much, Mahapatra, Park, Brandt and Rozin1997), and Kohlberg’s purely rationalist vision has given way to a greater role of emotions in moral judgment (Rozin et al., Reference Rozin, Lowery, Imada and Haidt1999). This broader approach has lead in turn to the social-intuitive model (Haidt, Reference Haidt2001), and to other models where culture and ideology play an essential role in understanding human morality (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and Ditto2013; Janoff-Bulman, Reference Janoff-Bulman2009). The study of the relationship between age and morality from these last theoretical approaches, however, has been very scarce. One remarkable work is Jensen (Reference Jensen2011), who investigated the relationship between age and morality from the “big three” approach, and found that morality shows a clear positive and curvilinear relationship with age in its community component, and a weak realtionship in its divinity component, but no relationship in its autonomy (or individual) component.

Therefore, this article aims to further exploring the relationship between morality and age from the very successful the Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) framework, through a massive meta-analysis, that can also serve as a preliminary test of the assumptions the MFT does about the nature of human morality.

Morality, Age, and Moral Foundations Theory

Haidt et al. developed the MFT partly based on the “big three” morality model (Rozin et al., Reference Rozin, Lowery, Imada and Haidt1999; Shweder et al., Reference Shweder, Much, Mahapatra, Park, Brandt and Rozin1997) and the Relational Models Theory (Fiske, Reference Fiske1992; Rai & Fiske, Reference Rai and Fiske2011). These models had already added community and sanctity elements to the harm and justice-based elements already present in rationalist moral models, and had based their claims on empirical evidence gathered primarily outside the US. Specifically, the MFT organizes all human morality in the following series of moral foundations: Fairness/Cheating, Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Purity/Degradation. A sixth foundation, Liberty/Oppression, was added a few years later (Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Koleva, Graham, Ditto and Haidt2012). Haidt addressed the Harm/Care and Fairness/Cheating (and later Liberty/Oppression) as the Individualizing Foundations, because they were individual and interpersonal foundations of morality, whereas Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Purity/Degradation, the more culture and group-specific, were labeled as the Binding Foundations.

The moral foundations overall correspond not so much to specific values but to more general adaptation tools that have been partially been built through evolution in the human body. Nevertheless, moral intuitions are not only innate but also learned. Whereas the child is already born with at least some form of moral intuitions, cultures can modify, enhance, or suppress the emergence of moral intuitions to create a specific moral matrix (Haidt, Reference Haidt2001), which in turn evolve through generations. Therefore, according to Haidt, morality is not either innate nor learned, but rather is an emergent product.

Moreover, though rationality does not play a central role in people’s morality, it can affect self’s moral intuitions in a very limited way: Mainly by reasoning and under very specific personal circumstances (Haidt, Reference Haidt2001, Reference Haidt2003).

MFT has been very successful, and it has been used in research and publications from different disciplines (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik and Ditto2013; Tamborini, Reference Tamborini2011; Vaughan et al., Reference Vaughan, Bell Holleran and Silver2019). However, few investigations have studied the relationship between age and moral foundations or even morality in general. Although Haidt (Reference Haidt2001) described some processes through with morality can evolve, no general assumptions about how specifically the moral matrix of the individual evolve over time, were made, contrary to what some evidence from the “big three” model (Jensen, Reference Jensen2011) and rationalist models suggest (Armon & Dawson, Reference Armon and Dawson1997; Bielby & Papalia, Reference Bielby and Papalia1975; Pratt et al., Reference Pratt, Diessner, Hunsberger, Pancer and Savoy1991).

Moreover, among the few publications that have researched the relationship between age and moral foundations, the results are not conclusive. For example, Miles (Reference Miles2014) found a positive relationship between moral foundations and age, as did Friesen (Reference Friesen2019), using a US sample, especially regarding Authority/Subversion and Purity/Degradation. On the contrary, Rebega (Reference Rebega2017) found, using a Romanian sample, that although Authority/Subversion values increased with age, Purity/Degradation did not: Finally, using a Swedich sample, Nilsson et al. (Reference Nilsson, Erlandsson and Västfjäll2020) positive correlation for Individualizing Foundations and age, but not between Binding Foundations and age. The possible effect of culture on these differences has not been researched to date.

As it can be seen, the question whether people’s moral intuitions change with age or not is far from being answered, and neither is the effect culture and other factors could have on these hypothetical differences.

About this Study

The number of empirical studies focused just on the MFT itself has been numerous, though not focused on age. However, age as a sociodemographic variable is routinely included in many of the studies. That is why, taking advantage of the large amount of potential information obtained to date, a meta-analytical study was carried out to explore whether there is a significant correlation between each moral foundation and age or how does this relationship depend on culture and other variables.

The cross-sectional nature of this methodological approach is a first step to comprehend how moral foundations evolve with age, and it has been utilized as so by authors like Kohlberg (Reference Kohlberg1958). Since our sample is massive and can analyze how culture, gender and other variables can effect on the relationship between age and moral foundations, this exploratory research can serve as a means to further investigate by accurate longitudinal approaches the way morality evolves throughout the lifespan.

Method

The present work aims to study the relationship between age and different dimensions of the Moral Foundations Model proposed by Haidt & Graham (Reference Haidt and Graham2007) through the implementation of meta-analytic analyses following the guidelines recently proposed by the American Psychological Association Publications and Communications Board Task Force (Appelbaum et al., Reference Appelbaum, Cooper, Kline, Mayo-Wilson, Nezu and Rao2018).

Search Strategy and Study Selection Criteria

Our search period covered the years 2007 to 2018. In the search, PsycINFO and Google Scholar databases were employed and the following keywords were set to be found anywhere in the documents with the following terms: “Moral foundations” and “Haidt”.

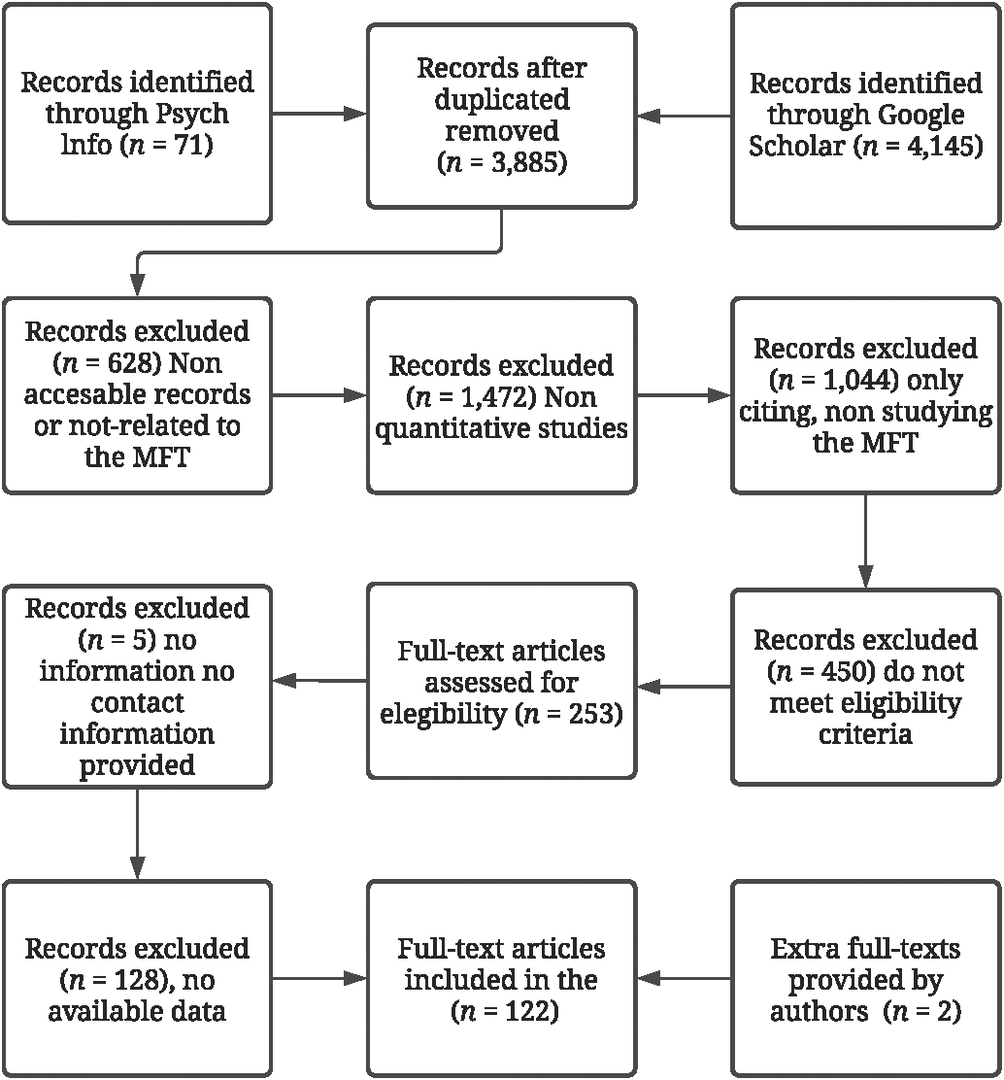

One main inclusion criteria was applied: To be an empirical study where age and moral were measured as quantitative variables in a sample of more than one subject. The following exclusion criteria were applied: (a) to be a single subject clinical trial, or a case series study; (b) to have applied a moral measure not based on the model originally proposed by Haidt & Graham (Reference Haidt and Graham2007); (c) to have used a psychological clinical sample; (d) to applied any experimental manipulation before applying the moral measurement tool. The flowchart presented in Figure 1 describes and adds details on the selection process of the studies. At the end of the process we had located 239 independent samples among 122 different studies in which an estimate of the Pearson correlation coefficient between age and any of the moral components was reported in the own document, informed via email, or computed with the online dataset.

Figure 1. Flow Chart of the Studies Search

Coding of the Studies

Pearson’s correlation between age and moral was coded as the effect size estimate from each primary study. A positive correlation implies that, the older the people are, the higher scores they obtain in that precise moral construct. Whereas a negative effect size or correlation means that, the older the people are, the lower scores they obtain for that moral construct.

Several moderator variables were coded concerning methodological aspects and sample characteristics. When data needed for coding the potential moderator variables was not reported, emails were sent to authors asking for that specific information. With respect to the sample characteristics, we coded: (a) Geographical location (country and continent); (b) sample size; (c) gender distribution of the sample (% female); (d) mean and standard deviation of the participants’ age (in years); and (e) political ideology (coded quantitatively from 0 = extreme liberal to 1 = extreme conservative). Regarding the methodological aspects, the instrument used to measure the moral components was coded: the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ30; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and Ditto2011), other versions of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire, other psychometrically validated scales, and ad-hoc scales.

Statistical Analyses

Separate meta-analytic analyses were carried out for each moral foundation and moral group correlated with age in at least five independent samples (Dimitrov, Reference Dimitrov2002; Sawilowsky, Reference Sawilowsky2000). Due to the natural asymmetry of the Pearson’s correlation coefficients distribution, correlation estimates should be transformed in order to meet the assumptions of the analyses used to meta-analyze them and search for moderators (Sánchez-Meca et al., Reference Sánchez-Meca, López-López and López-Pina2013). The most suitable transformation to normalize Pearson’s correlation coefficients is Fisher’s Z:

![]() , where

, where

![]() $ {\hat{\rho}}_{XX} $

is the correlation estimate.

$ {\hat{\rho}}_{XX} $

is the correlation estimate.

Although the statistical analyses were performed using the Fisher’s Z transformation, all tables and figures show the pooled means and their respective confidence limits once back transformed to the Pearson’s correlation metric for the purpose of facilitating interpretation (Borenstein et al., Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2009).

As a large variability was expected among the effect sizes, a random-effects model was assumed (Borenstein et al., Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2009; Sánchez-Meca & Marín-Martínez, Reference Sánchez-Meca and Marín-Martínez2008). The effect sizes were weighted by the inverse variance method, where the variance is the sum of the within-study and the between-studies variances. Between-study variance,

![]() $ {\unicode{x03C4}}^2 $

, was estimated using the Paule and Mandel estimator (Boedeker and Henson, Reference Boedeker and Henson2020). The 95% confidence interval around each overall reliability estimate was computed with the improved method proposed by Hartung (Reference Hartung1999). Heterogeneity among estimates of the same reliability coefficient was assessed with the Q test and the I2 index, assuming a level of significance of .05 and I2 values of approximately 25%, 50%, and 75% as low, moderate, and large heterogeneity, respectively (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003).

$ {\unicode{x03C4}}^2 $

, was estimated using the Paule and Mandel estimator (Boedeker and Henson, Reference Boedeker and Henson2020). The 95% confidence interval around each overall reliability estimate was computed with the improved method proposed by Hartung (Reference Hartung1999). Heterogeneity among estimates of the same reliability coefficient was assessed with the Q test and the I2 index, assuming a level of significance of .05 and I2 values of approximately 25%, 50%, and 75% as low, moderate, and large heterogeneity, respectively (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003).

For meta-analytic analyses with at least 30 correlation estimates, moderator analyses were conducted through meta-regression analyses for continuous variables and weighted analysis of variance (ANOVA) for qualitative variables. Mixed-effects models were assumed, using the improved F statistic proposed by Knapp and Hartung (Reference Knapp and Hartung2003) to test the statistical significance of moderator variables, given that it offers a better control of the Type I error rate than the standard QB and QR statistics (Hedges & Olkin, Reference Hedges and Olkin1985). The QE and QW statistics allow testing the model misspecification for meta-regression and ANOVA, respectively. The proportion of variance accounted for by the moderator variables was estimated with R 2, as it considers the total and residual between-study variances (López-López et al., Reference López-López, Marín-Martínez, Sánchez-Meca, van den Noortgate and Viechtbauer2014).

Finally, to assess publication bias, Begg’s rank correlation test (Begg & Mazumdar, Reference Begg and Mazumdar1994), Egger’s regression test (Egger at al., Reference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder1997), and Precision Effect Test-Precision Effect Estimate with Standard Error (PET-PEESE; Stanley, Reference Stanley2005; Stanley & Doucouliagos, Reference Stanley and Doucouliagos2007) analyses were conducted, and funnel plots for every moral foundation and foundations group were visually inspected.

All of the statistical tests were interpreted assuming a significance level of 5%, and all of the statistical analyses were carried out using the Metafor package in R (Viechtbauer, Reference Viechtbauer2010). Complete data files used for the analyses reported below are available upon reasonable request.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics of the Studies

The references for the 122 studies included in the meta-analysis can be found in the online-only supplemental material. The total sample was N = 492,298. The distribution of sample sizes was extremely right-skewed and leptokurtic, with a mean of 1,587.19 participants per sample (median = 283, SD = 1489.8, skewness = 3.51, kurtosis = 13.42). This is due to the fact that just one sample, from Graham et al. (Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and Ditto2011) had 281,824 subjects with respect to the rest of the 238 samples that had 210,474 subjects. The average female percentage was available for 83.3% of the samples, with a mean value of 54.78% (SD = 15.02). The mean age of participants was available for 98.75% of the 239 samples, and its distribution had a mean value of 30.58 (SD = 8.95). Finally, political ideology (coded quantitatively from 0 = extreme liberal to 1 = extreme conservative) was available for 49.2% of the samples, with a mean value of 0.29 (SD = 0.18).

Pooled Estimates and Heterogeneity

Separate meta-analytic analyses were conducted for the correlation between the participants’ age and each moral construct that were analyzed. Although the statistical analyses were performed using Fisher’s Z transformation for raw Pearson’s correlation estimates, all tables and figures show the pooled means and their respective confidence limits once back-transformed to the Pearson’s correlation coefficient metric to facilitate interpretation.

The number of independent estimates, the cumulated sample size, the pooled correlation for each moral construct and its 95% confidence interval, alongside the τ2 estimate, the Q test, and the I 2 index can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Pooled Pearson’s Correlation Estimate and its 95% Confidence Interval, between-study Variance Estimate, and Heterogeneity Statistics for the Relationship between Age and the Eight Moral Constructs

Note. k = number of independent samples were the estimate of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient was available; N = total sample size; r += pooled correlation estimate; CI = confidence interval; τ2= between-study variance; Q = Cochran’s heterogeneity Q statistic with k–1 degrees of freedom; I2 = heterogeneity index.

*** p < .001.

The pooled correlations between age and the Loyalty/Betrayal foundation, and the moral groups Individualizing and Binding Foundations were not statistically different from zero, whereas small pooled correlations were obtained for the relationship between age and the Harm/Care, Fairness/Cheating, Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Purity/Degradation foundations. However, all of the significant pooled correlations fell between .04 and .08, which represent effect sizes of negligible magnitude following the Cohen interpretations (Reference Cohen1988).

Evidence of heterogeneity was found for the correlation estimates between all the moral constructs and age, with all Q statistics being significant (p <. 001).

![]() $ {I}^2 $

indexes were of large magnitude in all cases, ranging from 87.53 to 95.14%, except for the correlation estimates between the Individualizing Foundations and age (I 2= 30.82%) which showed a small-medium magnitude. It is worth noting that the I 2 index for the correlation estimates between the Binding Foundations and age (79.38%) was more than double of the I 2 index for the correlation estimates between the Individualizing Foundations and age (30.82%).

$ {I}^2 $

indexes were of large magnitude in all cases, ranging from 87.53 to 95.14%, except for the correlation estimates between the Individualizing Foundations and age (I 2= 30.82%) which showed a small-medium magnitude. It is worth noting that the I 2 index for the correlation estimates between the Binding Foundations and age (79.38%) was more than double of the I 2 index for the correlation estimates between the Individualizing Foundations and age (30.82%).

Analysis of Publication Bias

We carried out several analyses to assess whether publication was a potential threat to the validity of our results. Table 2 presents the results for Begg’s rank correlation tests, Egger’s regression tests, and PET-PEESE analyses, whereas Figure 2 shows the funnel plots for every moral construct meta-analyzed.

Table 2. Results for the Sensitivity Analyses of Publication Bias on the Correlational Meta-Analytic Analyses for the Relationship between Age and the Eight Moral Constructs

Note.

![]() $ \unicode{x03C4} $

= Kendall’s

$ \unicode{x03C4} $

= Kendall’s

![]() $ \unicode{x03C4} $

statistic for Begg’s rank correlation test; t

n–2= T student statistic with n–2 degrees of freedom for Egger’s regression test; F

1;n–2= F statistic with 1 and n–2 degrees of freedom for PET-PEESE analyses (when the PET regression’s intercept does not reach statistical significance, PET results are reported; otherwise, PEESE results are presented); p = p-value associated to the statistic reported in the previous column.

$ \unicode{x03C4} $

statistic for Begg’s rank correlation test; t

n–2= T student statistic with n–2 degrees of freedom for Egger’s regression test; F

1;n–2= F statistic with 1 and n–2 degrees of freedom for PET-PEESE analyses (when the PET regression’s intercept does not reach statistical significance, PET results are reported; otherwise, PEESE results are presented); p = p-value associated to the statistic reported in the previous column.

Figure 2. Funnel Plot for the Random-Effects Meta-Analysis of the Pearson’s Correlation Estimates between Age and the Eight Moral Constructs

The Begg’s rank correlation test, Egger’s regression test, and PET-PEESE analyses yielded statistically significant results for the correlation coefficients between the Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Purity/Degradation foundations and age, and for correlation coefficients between the Individualizing Foundations group and age. Therefore, there is evidence for a positive relationship between the effect sizes and the studies’ sample size. Nevertheless, this does not necessarily mean that there is an effect of publication bias (in fact, funnel plots do not show a clear asymmetric pattern in this regard), it could also be due to the influence of small-study effects, such as heterogeneity. Since significant results are found only in moral constructs for where the I2 indexes were above 90%, it remains unclear whether the positive results for the sensitivity analyses of publication bias could be influenced by the underlying heterogeneity found among the effect sizes.

Moderator Analyses and Explanatory Models

Moderator analyses were carried out to explain the large variability exhibited by the effect sizes of the relationship between all the moral foundations and age with at least 30 correlation estimates. Weighted ANOVAs and simple meta-regression were carried out taking Pearson’s correlations coefficients as the dependent variable for categorical and continuous moderator variables.

With respect to the weighted ANOVAs analyses, no significant relationship was found between any categorical moderator and the effect sizes of the correlation between any moral construct and age. Therefore, tables showing the ANOVAs results are not presented in this document, but they can be accessed from the supplemental material (available in an online-only supplemental archive). Regarding the results of the simple meta-regressions, Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 present the relationships between the quantitative moderators and the correlation estimates between age and the Harm/Care, Fairness/Cheating, Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Purity/Degradation foundations and the Individualizing and Binding Foundations groups, respectively.

Table 3. Results of the Simple Meta-Regressions Applied to Pearson’s Correlation Estimates for the Relationship between Age and the Harm/Care Moral Foundation, taking Continuous Moderator Variables as Predictors

Note. k = number of independent samples were the estimate of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient was available; N = total sample size; bj = regression coefficient of each predictor; F = Knapp-Hartung’s statistic for testing the significance of the predictor, with 1 degree of freedom for the numerator and k – 2 for the denominator; p = probability level for the F statistic; QE = statistic for testing the model misspecification; R2 = proportion of variance explained by the predictor.

*** p < .001.

Table 4. Results of the Simple Meta-Regressions Applied to Pearson’s Correlation Estimates for the Relationship between Age and the Fairness/Cheating Moral Foundation, Taking Continuous Moderator Variables as Predictors

Note. k = number of independent samples were the estimate of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient was available; N = total sample size; bj = regression coefficient of each predictor; F = Knapp-Hartung’s statistic for testing the significance of the predictor, with 1 degree of freedom for the numerator and k – 2 for the denominator; p = probability level for the F statistic; QE = statistic for testing the model misspecification; R2 = proportion of variance explained by the predictor.

*** p < .001.

Table 5. Results of the Simple Meta-Regressions applied to Pearson’s Correlation Estimates for the Relationship between Age and the Loyalty/Betrayal Moral Foundation, Taking Continuous Moderator Variables as Predictors

Note. k = number of independent samples were the estimate of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient was available; N = total sample size; bj = regression coefficient of each predictor; F = Knapp-Hartung’s statistic for testing the significance of the predictor, with 1 degree of freedom for the numerator and k – 2 for the denominator; p = probability level for the F statistic; QE = statistic for testing the model misspecification; R2 = proportion of variance explained by the predictor.

*** p < .001.

Table 6. Results of the Simple Meta-Regressions Applied to Pearson’s Correlation Estimates for the Relationship between Age and the Authority/Subversion Moral Foundation, Taking Continuous Moderator Variables as Predictors

Note. k = number of independent samples were the estimate of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient was available; N = total sample size; bj = regression coefficient of each predictor; F = Knapp-Hartung’s statistic for testing the significance of the predictor, with 1 degree of freedom for the numerator and k – 2 for the denominator; p = probability level for the F statistic; QE = statistic for testing the model misspecification; R2 = proportion of variance explained by the predictor.

*** p < .001.

Table 7. Results of the Simple Meta-Regressions Applied to Pearson’s Correlation Estimates for the Relationship between Age and the Purity/Degradation Moral Foundation, Taking Continuous Moderator Variables as Predictors

Note. k = number of independent samples were the estimate of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient was available; N = total sample size;

![]() $ {b}_j $

= regression coefficient of each predictor; F = Knapp-Hartung’s statistic for testing the significance of the predictor, with 1 degree of freedom for the numerator and k – 2 for the denominator; p = probability level for the F statistic; QE = statistic for testing the model misspecification; R2 = proportion of variance explained by the predictor.

$ {b}_j $

= regression coefficient of each predictor; F = Knapp-Hartung’s statistic for testing the significance of the predictor, with 1 degree of freedom for the numerator and k – 2 for the denominator; p = probability level for the F statistic; QE = statistic for testing the model misspecification; R2 = proportion of variance explained by the predictor.

*** p < .001.

Table 8. Results of the Simple Meta-Regressions Applied to Pearson’s Correlation Estimates for the Relationship between Age and the Moral Group Individualizing Foundations, Taking Continuous Moderator Variables as Predictors

Note. k = number of independent samples were the estimate of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient was available; N = total sample size; bj = regression coefficient of each predictor; F = Knapp-Hartung’s statistic for testing the significance of the predictor, with 1 degree of freedom for the numerator and k – 2 for the denominator; p = probability level for the F statistic; QE = statistic for testing the model misspecification; R2 = proportion of variance explained by the predictor.

*** p < .001.

Table 9. Results of the Simple Meta-regressions Applied to Pearson’s Correlation Estimates for the Relationship between Age and the Moral Group Binding Foundations, Taking Continuous Moderator Variables as Predictors

Note. k = number of independent samples were the estimate of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient was available; N = total sample size; bj = regression coefficient of each predictor; F = Knapp-Hartung’s statistic for testing the significance of the predictor, with 1 degree of freedom for the numerator and k – 2 for the denominator; p = probability level for the F statistic; QE = statistic for testing the model misspecification; R2 = proportion of variance explained by the predictor.

*** p < .001.

Starting with the moral foundations, the participant’s mean age and the standard deviation of participant’s age showed a significant and positive relationship with the correlation estimates between age and the Harm/Care, Fairness/Cheating, Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Purity/Degradation foundations. This means that, the greater the participant’s mean age and the greater the variability of the participant’s age, the higher the positive correlation between the participants’ age and their score on the moral construct analyzed. Moreover, ideology showed a positive and significant relationship with the correlation estimates between Loyalty/Betrayal and age. These results indicate that, the more conservative people are, the higher the positive correlation between the participants’ age and their score on the Loalty/Betrayal foundation.

With respect to the Foundations groups, only the standard deviation of the participant’s age showed a statistically significant relationship with the correlation estimates between age and the Individualizing Foundations, whereas no significant relationship was found between any quantitative moderator and the correlation estimates between age and the Binding Foundations.

Only two quantitative moderator variables showed a significant effect on the correlation estimates between age and all the moral foundations analyzed (participant’s age and standard deviation of participant’s age), except for the correlation estimates between age and the Loyalty/Betrayal foundation, for which ideology also showed a significant effect.

Therefore, at the time of proposing an explanatory for explaining the high heterogeneity found among the correlation estimates between age and every moral foundation, collinearity assumption was tested. Given that the correlation between the mean and the standard deviation of the participants’ age for the collected studies was statistically significant (r = .66, p < .001), no explanatory models could be proposed for correlation estimates between age and the Harm/Care, Fairness/Cheating, Authority/Subversion, and Purity/Degradation foundations. For the relationship between age and all the moral foundations, the participant’s mean age explained a greater percentage of variance (

![]() $ {R}^2 $

) than the standard deviation of age did.

$ {R}^2 $

) than the standard deviation of age did.

For correlation estimates between age and the Loyalty/Betrayal foundation, the participant’s mean age was included alongside the ideology for fitting an explanatory model. Due to missing data in some variables, correlation estimates for only 79 independent samples were included in the model. The model showed a statistically significant relationship with the Pearson’s correlation coefficients, F(2, 76) = 20.10, p < .001, accounting for 40.80% of the variance. Both predictors, the participants’ mean age, F(1, 76) = 23.18, p < .001, and ideology, F(1, 76) = 10.23, p = .002, showed a statistically significant relationship with the correlation coefficients once the influence of the other variable was controlled. The inclusion of participants’ mean age led to an increase of 23.97% of variance explained, and the inclusion of ideology led to an increase of 13.15%, once the remaining predictor had already been included in the model.

Discussion

The results fit into MFT predictions about moral evolution. Although moral foundations do not show a consistent increasing or decrasing pattern throughout the lifespan, a weak curvilinear relationship can be found between moral foundations and age, especially for binding foundations. This effect is small but consistent throughout every region, gender and moral instrument utilized. The main findings of this study can be summarized in two points: (a) Moral foundations and age are related in a weak and apparently undefined manner; (b) the relationship between moral foundations and age do not depend on region or gender, but Ideology plays a role.

Moral Foundations and Age are Related in a Weak and Undefined Manner. Individualizing Foundations and Binding Foundations Evolve Differently

Both for the six moral foundations and the two moral groups, the pooled correlation with age is either non significant or significant but tiny. Given the size of the sample used, and therefore, the great power of analysis that we have handled, we can state that, although the effect is significant, the effect size is not relevant. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that significance is found only in larger samples (Harm/Care, Fairness/Cheating, Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Purity/Degradation), and not in smaller ones (Liberty/Oppression, Individualizing Foundations and Binding Foundations). Moreover, the largest pooled correlation, found in Harm/Care, only explains only 0.0016% of the variability of Harm/Care.

Nevertheless, heterogeneity found in the aggregate correlations is great, and age itself explains a significant percentage of such heterogeneity, though only in the moral foundations separately. Therefore, it can be stated that the relationship between age and moral foundations is not linear, but may be rather nor-linear, as (at least) some moral foundations have a relationship with age that in turn depends on age. This relationship, however, does not fit a quadratic or cube relationship, and appear not to follow a specific pattern. As it can be ckecked at the supplementary material, the dispersion diagrams show that the relationship between Harm/Care and Fairness/Cheating with age seems to be quite negligible, while the relationship between Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Purity/Degradation with age show some kind of positive tendency, although the pattern is not clear. In fact, regarding our analyses, results indicate that binding foundations, both as a group and separately (Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Purity/Degradation) show greater heterogeneity than the individualizing foundations (Harm/Care, Fairness/Cheating, and Liberty/Oppession, being Individualizing Foundations’ heterogeneity non-significant). This means that people who vary their moral matrix throughout their lives tend to modify group-based moral concerns to a greater extent than individual-based moral concerns, and also means that this trend is positive: People tend to be more moralistic than less. In other words, the most frequent change in the moral matrix will be that of a gradual increase in some of the binding foundations, as Jensen (Reference Jensen2011) found from the “big three” approach, although this tendency is not linear. Results regading individualizing foundations are less clearly interpretable with regard to Harm/Care and Fairness/Cheating separately, as the effect of age on both Harm/Care, Fairness/Cheating’s relationship with age is even weaker. Overall, moral foundations appear to be quite stable over the lifespan.

The Relationship between Moral Foundations and Age Do Not Depend on Region or Gender, but Ideology Plays a Role

One of the most important findings we have encounter is the absence of a significative role region has on the relationship between age and moral foundations. That is, people seem to have a quite stable moral matriz thoughout the lifespan overall, and also show a small but significant trend of increasing binding foundations as they get older, independently of the region and gender. Both men and women, people from different continents, or with different levels of weirdness, do not show significant different trends regarding this issue. Therefore, although culture can shape the intuitive moral draft the person has born with, the general moral evolution people have is essentially the same, regardless of the specific personal circumstances that each person can encounter thoughout the life than can also have an effect on one’s moral matrix.

Finally, Ideology appears to be an important positive moderator with regard only to Loyalty/Betrayal, as it explains 16.83% of age-Loyalty/Betrayal relationship. This means that more conservative people will tend to increase at a higher rate their Loyalty/Betrayal levels than liberal people. In other words, conservatives become more loyal to their group of reference throughout their lives than liberals.

Limitations

The present study is pioneer in the study of the relationship between age and moral foundations. In addition, our data is diverse and rich. For example, the size of the sample is quite large, the age range with which we have worked is also quite large (the sample means range between 12.71 and 58.43 years) and it encompasses data from five continents.

However, its results have to be interpreted caoutiously. Since this is a cross-sectional study, our results have to be taken as a first (and we believe, meaningful), step to understand the relationship between moral foundations and age. For example, as this study is not longitudinal, what we have found is simply that, to this day, the moral matrices of people of different ages evolve in a specific way. As Kohlberg did regarding his model, after our cross-sectional approach, a longitudinal study is needed to confirm our findings, and/or further explain the heterogeneity found on the relationship between moral foundations and age, that may be only possible to study at an individual level.

Finally, our study could not examine how morality evolve at early age, since the lowest age contained in this meta-analysis is 12.71 years. That is, studies regarding children are necessary to be able to ensure our interpretations to a greater extent. So far, the available evidence in favor of a innate moral draft is little, but a very recent study (Peverill, Reference Peverill2020) points out, in line with what the MFT predicted, that moral foundations are already present in early childhood.

Conclusions

The present study, using a very large and diverse sample concerning gender, region and political ideology, has found that age and morals are not correlated but that there is complex non-linear relationship between group-based morality and age, whereas individual components of morality like ideas of caring and justice may not depend on age. This result supports the assumption that everybody is born with a moral draft that can change at some point depending on the cultural context, but only in a limited way. Specially, concerns of caring for others and justice may depend even less on age than group-based moral concerns. Could the lower heterogeneity found in Harm/Care and Fairness/Cheating, and their quite low relationship with age mean that these two moral foundations are more innate than the group-based, Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, and Purity/Degradation ones? If this is true, recognizing that human beings can vary their moral matrix, but mostly regarding their group components, and also recognizing that some moral components may be just less likely to change, would allow approaching education and the study of conflicts from more individualized, less stereotyped, and, therefore, more effective approaches.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2021.35.