One day a peasant named Çavuş Emmi (Uncle Sergeant) says to İbik Dayı (Uncle İbik), “If my donkey dies, I will skin it and cover my cow with its skin so that I can escape from the livestock tax.” Thereupon, İbik Dayı suggests that Çavuş Emmi wears this skin to avoid the road tax.Footnote 1 This was one of the popular jokes that spread across the Anatolian countryside from mouth to mouth in the 1920s and 1930s. This joke reveals the ways in which the peasants dealt with taxes. To be more specific, it was a reflection of tax evasion in popular culture. Opposition to the agricultural taxes by means of deception was so common that such acts became the subject of humor. Furthermore, both the widespread nature of tax resistance and its short- and long-term consequences were so far-reaching that this article suggests a correlation between the peasant opposition to agricultural taxes and the slow waning of the peasantry. The peasants’ tax resistance was among the factors that caused the early republican state’s low transformative capacity, which slackened Turkey’s modernization.

Anatolian peasants have been so resilient through the twentieth century that their survival led historian Eric Hobsbawm to write about Turkey in his magnum opus The Age of Extremes as follows: “Only one peasant stronghold remained in or around the neighborhood of Europe and the Middle East – Turkey, where the peasantry declined but in the mid-1980s, still remained an absolute majority.”Footnote 2 Among the well-known causes for this were late industrialization, the comparative predominance of small landholding, slow urbanization, and the weakness of the state’s infrastructural capacity to transform society. Another important but lesser-known reason was the peasants’ struggle to survive. Although the Anatolian countryside appeared to lack peasant resistance and uprisings, everyday life was rife with peasants’ actions to cope with the difficulties. It was this resourcefulness of peasants in resistance and self-defense that allowed them to survive and hence further delay the modernization process and the dissolution of the peasantry. Perhaps one of the primary manifestations of peasants’ struggle was the resistance to the state’s effort to extract their scarce resources through agricultural taxes.

This article, collating untapped archive documents, newspapers, and other secondary data and concentrating on the daily encounters between state and society, scrutinizes the everyday and mostly informal means by which the Anatolian peasants survived, protected themselves, and expressed their discontent in the face of burdensome taxes during the first two decades of the Republic. It shows how political exclusion drove the low-income and smallholding peasant majority and rural poor to adopt subtle and everyday forms of resistance short of rebellion that manifested itself in rural crimes, specifically what the ruling elite called tax evasion. It also contemplates how and to what extent peasants influenced Turkey’s modernization, albeit indirectly and unintentionally. Contrary to existing studies that have portrayed peasants as silenced, cynical opponents or pre-modern groups doomed to extinction, this study underlines their key role in the formation of modern Turkey. Its findings throw light on the social dynamics that limited and even partially thwarted Kemalist modernization in the long run. This article aims to contribute to recent historiography of the Republic, which has shifted the focus from the elite and the state, asserting that change might come from below. In this regard, it offers a critique of the modernization theory that credited the elite, the state, and their splendid projects that have always mesmerized historians as sole actors of Turkish history and politics. It also points out the other side of the coin, which is the exorbitant price of the modernization process that the peasants negotiated rather than passively accepted.

After the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, the authoritarian Republican People’s Party (RPP), led by Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk), launched a series of extensive political, cultural, legal, and economic reform programs to create a modern and secular nation-state during the interwar period. Comprehensive modernization schemes, accompanied by the state’s growing centralization and control over the population and economy, which had been underway since the nineteenth century, gained impetus with the Republic. The ruling elite, in close association and overlapping with newly emerging Muslim-Turkish business circles, gave impetus to economic modernization through the policy of state capitalism. In particular, the lack of basic industries led the new rulers to pursue state-led industrialization schemes. The new state embraced economic policies that nourished and entrenched a capitalist economic structure. All of this required the transfer of vast economic resources from the peasants as the basic production force to commercial and industrial fields. During the first years of the Republic, peasants formed more than 80 percent of the population. Agriculture was the mainstay of the economy. The new regime had therefore attempted to fund its projects with rural resources. Hence, despite the abolition of the tithe (aşar) and tax farming (iltizam) in 1925, and the ruling circles’ populist rhetoric embodied in Atatürk’s famous saying, “the peasant is the master of the nation” (köylü milletin efendisidir), the costs of building a modern state and economy weighed heavily on the small plot holders and poor peasants. The new taxes, monopolies, commercialization of the rural economy, and industrialization schemes brought further exploitation. The peasants were sandwiched between state officials, such as tax collectors, monopoly officials, and gendarmes, and local dominants, who were primarily rich farmers. The Great Depression further aggravated the already unfavorable conditions in rural areas.

These are all well known thanks to existing historical studies. What is less known but equally important, however, is the peasants’ experience of these extraordinary conditions, particularly their struggle for survival amid this unprecedented upheaval. Surprisingly, although peasants constituted the majority of the population, their relations with the state and local powerholders have not been explored in depth. Scholarly interest generally revolved around state economic policies and agricultural structures.Footnote 3 The paucity of organized peasant rebellions resembling the peasant movements that occurred in other rural countries like Russia, Bulgaria, China, and Latin America during the same time span, led scholars to presume that the peasants completely surrendered to the state intervention in their lives and to the social injustice.Footnote 4 Even critical historical sociology or Marxian accounts, adopting the language of modernization theory, have portrayed the Anatolian peasants as submissive and hapless victims miserably succumbing to exploitation and oppression during the interwar period.Footnote 5

Historians of modern Turkey have barely examined the ways by which the peasants dealt with hardships and struggled for survival.Footnote 6 Rather, their focus on the ruling elite’s populist discourse and the abolition of the tithe led them to claim that the Republic had eased the peasants’ conditions at the expense of industrialization.Footnote 7 They have also seen the small landholding as a static land tenure system, as if it was free from the greed of large landowners, called ağa, and state capitalism. This postulation caused an underestimation of intravillage struggles in which smallholders tried to keep their land from falling under the large farmers’ control. This interpretation has also underpinned the peasants’ passivity thesis.Footnote 8 Historians, whether critical or nationalists, have mostly labeled rural crimes – such as livestock theft, smuggling, and banditry – as peculiar to tribalism or the Kurdish movement in eastern Anatolia.Footnote 9 Studies on Kurdish rebellions paid attention to rural uprisings in the Kurdish provinces as long as they were tied to the Kurdish nationalist movement; other rural crimes were excluded from the narrative of “the Kurdish awakening.”Footnote 10

This article is a humble contribution to recently growing efforts to embrace more informal, daily, and invisible but indirectly consequential forms of popular struggles and resistance mostly undetected by the established elite- and state-centered narratives. The theoretical origin of this effort can be found in the “history from below” approach of E. P. Thompson, subaltern studies, and broader conceptions of resistance by political anthropologists and sociologists like James C. Scott and Michel de Certeau. Their contributions provide insight into the political aspects of the seemingly non-political and daily behavior of the subaltern population, whose role and voice were silenced by established narratives that confined themselves to dealing with organized and ideological action. Likewise, the broader definition of politics, defined by Harold D. Lasswell as a struggle for the allocation of resources, also allows for the peasants’ actions, which were labeled as crime by the authorities, to be seen instead as an extension of popular politics.Footnote 11

What James C. Scott called “everyday forms of resistance” and “weapons of the weak” best exemplify how ordinary people, under risk of suppression, can display more informal and daily forms of resistance, ranging from foot dragging, poaching, cheating, tax evasion, smuggling, pilfering, and theft, to individual violence. As Guha and Chatterjee point out, rural societies, marked by illiteracy, sparsity of political organizations, and ethnic or religious fragmentation, and the high risk of state oppression, tended to adopt more covert and daily forms of resistance.Footnote 12 Along with other reasons, the accumulation of all of these daily resistances sometimes compelled governments to soften the obligations imposed on the peasantry or to ease the conditions that drove them to illegal actions. Therefore, the peasants’ struggles in daily life deserve close attention as the infrapolitics that influenced formal and high politics indirectly.

Indeed, these “weapons of the weak” became a widespread form of resistance and survival in rural areas in order to cope with the increasing weight of the new state with new impositions, particularly agricultural taxes. Rather than uprisings, minimizing losses by avoiding heavy tax obligations was perhaps the main means of survival. Contending with taxes in this way was prevalent across the Anatolian countryside. Undoubtedly these practices were not able to change the state policy directly. Nonetheless, they disabled the state’s resource-extraction capacity. This led the treasury to find itself weak, for in the face of such widespread practices it was unable to extract the revenues it sought. In this regard, weapons of the weak blunted the force of the burdens imposed by the state and allowed the peasantry to survive during the period.

Source extraction in the Anatolian countryside: burdensome agricultural taxes

During the first decades of the Republic, the government relied heavily on agriculture as the backbone of the economy to fund its extensive modernization schemes. Direct or indirect taxes on crops and livestock were the most common way of capturing agricultural surplus. These agricultural taxes were heavy, and collection methods made them more burdensome.

Despite the abolition of the tithe as well as tax farming in 1925, other agricultural taxes and tax burdens on the peasants gradually increased until the early 1930s. Therefore, contrary to the republican elite’s presentation of the tithe’s abolition as a grant to the peasantry, the government attempted to compensate for the losses of tithe revenues.

The most onerous taxes for the peasants were direct taxes, which entailed face-to-face encounters with the tax collectors. The proportion of direct taxes in the overall tax revenue increased from 22.6 percent between 1925 and 1930 to 34.3 percent between 1931 and 1940. The taxes on agriculture made up the greatest part of the direct taxes.Footnote 13 In this period the peasantry faced three major direct taxes: the land tax, the livestock tax, and the road tax. The land tax was imposed on all privately owned lands regardless of whether they were marshy, fallow, infertile, or cultivated. The rates of the land tax increased in 1925. Its share among the budget revenues rose to 6.5 percent in 1929, although its rate was lowered in the 1930s.Footnote 14 Such a tax policy forced the peasants to produce as much as possible. By increasing this tax, the government told the peasants, so to speak, “produce” or “perish.” However, the greater part of the Anatolian peasants was able to produce only for their own needs or a small amount for the market. Only the large landowners and middle-scale farmers had sufficient input and equipment to produce on large enough scales to afford to pay the land tax. Many small and even middle-scale landowners were not able to cultivate all of their lands due to the lack of necessary input and labor as well as insufficient irrigation facilities. Therefore, this tax weighed on poor peasants and some mid-sized plot holders. The peasants in an Ankara village with whom Niyazi Berkes talked, for instance, compared and contrasted the tithe and the land tax, complaining that the tithe was more favorable than the current land tax.Footnote 15

Furthermore, despite the radical decline in agricultural prices and even in the land prices with the Great Depression in 1929, the rate of the land tax was not reduced proportionally. In addition, during the economic crisis the tax continued to be assessed according to the previous astronomical values of the land. As noted by a contemporary expert, Şevket Raşit Hatipoğlu, although land valued at 20–5 liras in the Adana region before the economic crisis declined dramatically to 5 liras, the tax on such kinds of land was assessed according to their previous high prices. As a result, they were often compelled to sell their land or run into debt.Footnote 16 Given the prevalence of smallholdings throughout Anatolia, it is reasonable to think that this heavy tax must have created a financial burden for the great part of the self-sufficient small farmers rather than the large landowners who took advantage of the scale economy.

Another financial burden for the peasants was the livestock tax. This tax constituted one of the most important sources of revenue for the government from the beginning of the Independence War, with the rate increasing fourfold during the war. Therefore, the first law article discussed and enacted in the new National Assembly was the new Livestock Tax Law. Between 1923 and 1929, and especially right after the abolition of the tithe, the government further increased its rate several times and extended the scope of the tax from sheep and goats to cows, oxen, donkeys, pigs, horses, and camels.Footnote 17 The livestock tax remained at these high rates until the mid-1930s. The average share of the livestock tax in the budget revenues was around 5.9 percent between 1925 and 1930 and 5.2 percent between 1930 and 1939.Footnote 18

Another tax that inflicted the rural poor as well as the urban poor was the road tax. It was the most heartbreaking tax, leaving deep marks on the lives and memories of the peasants. The National Assembly first imposed it in the Road Obligation Law of 1921 to finance the Independence War. This tax required each male between the ages of 18 and 60 (except for the disabled) to annually pay the equivalent of four days’ income or provide three days’ labor on road construction. Just before the abolition of the tithe, the government passed a new Road Obligation Law to offset the absence of the tithe that was planned to be discarded. The tax amount was changed again in 1929 with the Law of Highroad and Bridges. The labor equivalent of a cash payment was also increased to twelve days working on road construction (at a maximum of twelve hours’ distance from the taxpayer’s domicile), unless they paid the tax, which was between 8 and 10 liras. This allowed the government to benefit from an unpaid labor force made up of low-income people, most of whom were poor peasants.Footnote 19 For instance, in 1932 the İstanbul governorship decided that about 8,000 peasants who had not paid the taxes of 1926, 1927, and 1928 in the Çatalca district of İstanbul were to work at least thirty-six days on road construction.Footnote 20 The contractors, highway officials, engineers, and local administrators often abused this tax by forcing the peasants to work in more distant places and for longer amounts of time than the law prescribed. For instance, some peasants from the İsabeyli Village of the Çal district in Denizli complained that officials had forced them to work for eighteen days instead of twelve.Footnote 21 As reported from Kırklareli and Konya, peasants whose daily income did not exceed 20 piasters were still forced to pay 12 liras. Most of the peasants who were not able to pay this amount were put to work in road construction under onerous working conditions.Footnote 22 Especially in the eastern part of the country, the road tax reached 15 liras, and compulsory work on the roads lasted longer than the law ordained.Footnote 23 What is worse, even peasants who paid the tax were sometimes forced into doing road work on the grounds that they had not paid the tax.Footnote 24

On the top of it all, the government, in search of additional funds for its wheat purchases, imposed a new tax on the flour mills in 1934 titled the Wheat Protection Tax.Footnote 25 The rate of this tax was the cash value of 12 percent of the wheat brought to the flour mills to grind. The tax covered only the mills in towns and city centers.Footnote 26 On the other hand, most of the towns in the countryside in those years were not more than big villages, most of the populations of which were peasants engaged in agriculture and animal husbandry. Moreover, most of the people who brought their wheat to flour mills in towns were peasants from neighboring villages. Therefore, this tax also afflicted peasants living in villages in the vicinity of small towns.Footnote 27

The peasants living in the Kurdish provinces also bore the brunt of the taxation. Actually, the state’s ability to access the resources in these faraway uplands was quite limited. Together with the tribal mobilization, this enabled many peasants to evade the taxes. However, as compared to the Ottoman state, the republican state was more determined to hold sway over the region financially. This partly accounts for the gendarme violence in the region, which aggrieved the peasants. Moreover, even after the abolition of the tithe, tribe chiefs and large landowners, called ağas, did not give up collecting the tithe as well as other traditional taxes and dues.Footnote 28 The tax collectors’ dependence on the ağas and tribal chiefs as an intermediary group for taxation also allowed them to manipulate the tax collectors and to squeeze the peasants.Footnote 29 Hence, the agricultural taxes fell most heavily on the poor peasants.

Dimensions of tax resistance

During the interwar years, the increase in tax rates and the extension of some taxes to hitherto exempt areas provoked a reaction from the peasants. Exacerbated by decreasing prices of crops with the global crisis and by the tax collectors’ abuses and mistakes, the practices of these taxes caused widespread discontent that culminated in tax avoidance and even protests in rural areas.

Most of the taxes imposed on the peasants were direct taxes, the kind most likely to provoke resistance since they required out-of-pocket payment and face-to-face encounters with state officials, which could degenerate into quarrels and even fights. Peasants avoided direct confrontation and protest as much as possible. The peasants’ repertoire of resistance largely comprised subtle ways of tax avoidance and cheating. As elsewhere all over the world, avoidance was a significant act of resistance to taxation.Footnote 30 They constantly deployed all of their ingenuity to get around the regulations by cheating, lying, faking compliance, and so forth. Yet, when avoidance was impossible, peasants occasionally raised open and violent objections.

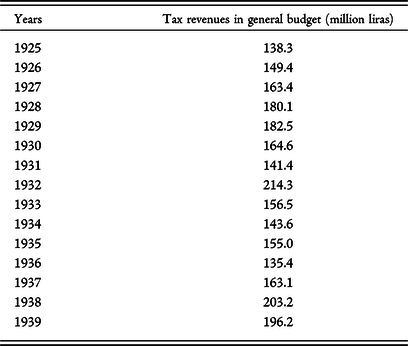

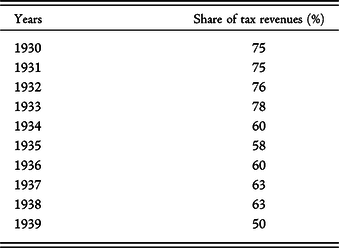

One important indicator of tax resistance was the considerable decrease in the state’s tax revenues during the 1930s, which dropped from 75 percent of total state revenues in 1930 to 58 percent in 1935 and 50 percent in 1939 (see Tables 1, 2, and 3). Undoubtedly, this downward trend was owed in part to tax relief programs, the gradual decrease in tax rates in the mid-1930s, agricultural price declines, and inefficiencies in tax collection. But another reason was tax avoidance among the peasants. Indeed, a discussion in a parliamentary session in 1934 laid bare the massive evasion of direct taxes, reaching up to 120,500,000 liras.Footnote 31 Given that the bulk of direct taxes were levied on agriculture as the main sector of the economy, peasant tax resistance was clearly significant.

Table 1. Total tax revenues in the state budget, 1925–39

Source: T.C. Maliye Bakanlığı Gelirler Genel Müdürlüğü, Bütçe Gelirleri Yıllığı 1977–1978: 1923–1978 Bütçe Gelirleri İstatistikleri (Ankara: Devlet İstatistik Enstitüsü, 1979), 6.

Table 2. Levied and collected direct taxes, 1925–30 (million liras)

Source: This table was prepared according to the data in T.C. Maliye Bakanlığı Bütçe Gider ve Gelir Gerçekleşmeleri (1924–1995), Sayı: 1995/5 (Ankara: T.C. Maliye Bakanlığı Bütçe ve Mali Kontrol Genel Müdürlüğü, 1995), 132.

Table 3. The share of the tax revenues in general state revenues, 1930–9

Source: T.C. Maliye Bakanlığı Gelirler Genel Müdürlüğü, Bütçe Gelirleri Yıllığı 1977–1978: 1923–1978 Bütçe Gelirleri İstatistikleri (Ankara: Devlet İstatistik Enstitüsü, 1979), 3.

A contemporary expert in the Finance Ministry noted that the state failed to collect the greater portion of the taxes. Tax evasion, he wrote, was out of control and direct tax revenues never reached target levels. Paucity of educated finance officials, as well as the low wages of tax collectors, also hampered the tax estimation and collection process.Footnote 32 Tax collection was more challenging in the distant Kurdish provinces. The figures regarding the land tax suggest that the state encountered great obstacles in collecting it in the eastern regions. According to a report from 1932 by General Inspector İbrahim Tali Öngören on the Kurdish provinces, including Diyarbakır, Van, Siirt, Hakkari, Muş, Mardin, Bitlis, and Urfa, the outstanding land taxes had been gradually increasing. By 1931, 87 percent of the estimated land tax in Urfa was in arrears. The next year, the government collected barely half of the estimated land tax.Footnote 33 Resentment of the land tax was so common that İnönü, on his tour to the eastern provinces, admitted, “We are waiting for the payment of the taxes in vain. They would not pay this high tax. We should not fool ourselves.”Footnote 34 According to the General Situation Report of the Erzurum governor, whereas the assessed land tax was 192,522 liras in 1932, the collected amount barely reached 47,303 liras. The following year, the estimated tax was 195,900 liras, but the collected amount only 60,838 liras. In 1934, these figures were 159,165 liras and 55,448 liras, respectively.Footnote 35 Not only in the eastern provinces, but also in the developed western province of İzmir, peasants refused to pay a considerable portion of the land tax. Thus, the provincial party congress in İzmir demanded an amnesty for land tax debt in 1936.Footnote 36

As for the livestock tax, tax revenues in Erzurum, an important center of livestock breeding, remained below anticipated levels. Although the tax amounts levied were 263,036 liras for 1932, 202,495 liras for 1933, and 178,501 liras for 1934, the peasants paid only 163,042, 147,185, and 138,962 liras respectively.Footnote 37 That is to say, taxpayers managed to curtail their tax burden by about a third. The livestock tax revenues in other eastern provinces remained far behind targeted levels.Footnote 38 Peasants usually concealed their livestock from the state. The actual number of animals exceeded those registered and taxed. In 1931–2, the number of taxed animals in Dersim, for instance, was 24,000 heads of sheep, goat, and cattle, and 7,500 camels. Their tax value was about 59,000 liras. However, 41,428 liras of this amount were not paid in 1932.Footnote 39 That is, livestock owners evaded almost 70 percent of the tax.

Peasants also avoided the road tax as much as possible. A newspaper reported that the thousands of peasants in the villages of the Çatalca district in İstanbul did not pay the road tax between 1927 and 1932.Footnote 40 Likewise, in 1934 it was reported many peasants in Kandıra had not paid the road tax for years.Footnote 41 The demands heard at provincial party congresses for cancelling road tax debts also indicate the extent of tax avoidance.Footnote 42 Republican bureaucrats often complained about peasants’ avoidance of the road tax. Refet Aksoy, for instance, in his Reference Aksoy1936 book Köylülerimizle Başbaşa (Head to Head with Our Peasants), wrote that the majority of peasants neither paid the road tax nor fulfilled their labor obligations. The peasants ran into tax debt and subsequently sought ways to circumvent their official obligations.Footnote 43 Local statistics give insight into peasant resistance to the road tax. In Erzincan, for example, the amount of the tax actually collected remained below the assessed levels. Peasants avoided working on road construction at the same time. The proportion of the collected taxes to the levied amount fell from 64 to 46 percent between 1927 and 1930.Footnote 44

Repertoire of tax resistance

Expressing criticisms: letters and petitions

Describing Atatürk’s 1930 tour of the country, Ahmet Hamdi (Başar), who accompanied the president, noted that “everyplace we go, the people are complaining concertedly about the weight of taxes.” In the villages of Kırklareli, peasants who stopped the president’s car bemoaned the calamitous agricultural prices and extortionate taxes as well as bad administration and corruption. In one village, the “sequestering” had become a pillage. “One touch, a thousand ouches! What wails are rising,” Başar wrote. They also heard numerous complaints about the livestock tax. In Thrace people were spiriting away their livestock to Bulgaria to evade the tax. In İzmir, Aydın, and Denizli, they heard the same complaints about the agricultural taxes. In Trabzon, as elsewhere, the peasants were complaining about the livestock tax and the land tax. Başar had seen many peasants who were jailed after their possessions were sequestered. In Sivas, the peasants had protested that the tax collectors had seized their livestock.Footnote 45

Indeed, the peasants did not remain silent and voiced their grievances and criticisms in the face of the tax burden. In their view, the severe tax burden amounted to exploitation by the government and city-dwellers.Footnote 46 Hilmi Uran, a prominent politician who investigated the provinces as party inspector, wrote that the major factor setting the peasants against the government was the unbearable taxes.Footnote 47 The complaint voiced most among the rural population was abusive or unqualified tax collectors.Footnote 48

Sending petitions and letters by frustrated peasants to government offices and newspapers was a ubiquitous strategy for coping with the taxes. Hundreds of thousands of peasants sought tax reduction, tax amnesty, or redress for wrongdoing or abuse by tax collectors in this way. Letters from peasants complaining about agricultural taxes inundated the national press and the government authorities, especially during the Great Depression. The majority of petitions were by individuals, yet a considerable number of them were penned collectively. Rather than using anti-government or seditious language, the peasants generally grafted their opinion on to the official discourse by praising the new regime in order to present their demands and complaints as legitimate and to invite the leaders to live up to their commitments and the RPP’s principle of populism.Footnote 49

The land tax, though seemingly targeted at the landowning class, primarily threatened subsistence farmers. Given the prevalence of small landownership in Anatolia, the rise of the land tax resulted in massive public criticism, especially during the Great Depression, when agricultural prices plummeted. According to a report by an erstwhile RPP deputy who investigated central, western, and northern Anatolian towns in 1930, peasants grumbled about the high estimation of the value of their lands as the tax base. In Havza (Samsun), for instance, peasants complained that officials had overestimated the value of their lands by 60 liras.Footnote 50 The peasant letters that flooded into newspaper, party, and government offices reveal the common grievance about the land tax. Such letters inundated the editors of Cumhuriyet, which conducted a survey about the tax. According to these letters, peasants complained most about the uneducated officials who erroneously assessed land values much higher than their actual worth and called on the authorities to correct such mistakes.Footnote 51

Peasants frequently compared the abolished tithe to the land tax, arguing that the latter was more extortionate and arbitrary than the former. As one noted, “the tithe pales in comparison with the land tax.”Footnote 52 A peasant named Mehmet Emin from Adapazarı found the land tax to be “more harmful than the tithe.” The tax was so high that low-income peasants who needed a portion of the harvest for their own subsistence were required to sell off the entire yield in order to pay it.Footnote 53 Another peasant complained that although he had been paying 150 piasters as land tax for years, the amount had recently increased to 1,000 piasters. He wrote that he had no intention of paying this “unjust tax.”Footnote 54 Some peasants wrote to newspapers to demand a reduction. Köroğlu, for instance, noted that “the peasants had been sending many letters to the newspaper insisting on a reduction in the land tax rate.”Footnote 55

The National Assembly also received many petitions sent by peasants from all corners of Anatolia collectively and individually. The petitioners sought a decrease in the land tax rates and inflated land values. Peasants in İzmit, Hopa, and Vezirköprü, for instance, penned petitions collectively protesting the astronomical amounts of the land tax and demanding a discount.Footnote 56 Petitioning the government, peasants demanded settlement of their land tax debts.Footnote 57

Tax relief demands were also expressed in local party congresses. According to the proceedings of the 1936 İzmir party congress, peasants of the province had requested the government to waive half of their land tax debt.Footnote 58 Likewise, peasants in Denizli, Kırşehir, and Tekirdağ requested the government to forgive the agricultural taxes, including the land tax.Footnote 59

Peasants’ concerns about the livestock tax were also expressed at the RPP’s provincial congresses, deputy reports, petitions, and letters to newspapers. The wish lists submitted by thirty-nine provincial party congresses to the Third General Congress of the RPP held in 1931 included the grievances of the peasantry that stemmed from this tax. Their primary demand was the reduction of its rates.Footnote 60

Petitioning both local and central authorities, peasants also raised their objections to the livestock tax. Many demanded a tax relief program including either an installment plan or cancellation of the accrued tax debts.Footnote 61 Deputies’ reports also depicted the peasants’ negative mood because of this tax. From Thrace, the Edirne deputy reported that complaints about the livestock tax had grown into widespread discontent in the region. From southern Anatolia, the Mersin and Cebeliberet (Osmaniye) deputies also noted that the high rates, unintelligible assessment, and collection methods of the livestock tax were major sources of grievance.Footnote 62

Peasants also used the newspapers to criticize the livestock tax. Son Posta, for instance, noted that the peasants in Safranbolu had sent a letter describing how animal husbandry had come to a halt in their region due to the high taxes. The peasants, on the edge of bankruptcy, wished for a reduction in the tax rates.Footnote 63 Although the government reduced the rates of the livestock tax in 1931 and again in 1932, requests for a further decrease or tax amnesty continued to inundate the authorities through petitions or politicians’ reports.Footnote 64 Disgruntlement with the livestock tax was also debated at the provincial congresses of the RPP. Almost all provincial congresses added requests for reduction in the rates and scope of the tax to their wish lists. As far as can be deduced from these lists, the peasants had three concerns: a substantial reduction in the tax rates to offset declining livestock prices; exemption of young animals from taxation; and exemption of draught animals because these animals did not yield any profit.Footnote 65 Unsurprisingly, in eastern villages like Dersim, where the main livelihood was animal breeding, peasant discontent was highest. In one instance, Dersim peasants poured out their grief to an army commander who visited the villages, openly criticizing the livestock tax and the wrongdoings of tax collectors.Footnote 66

Perhaps nothing dashed the rural and urban poor so much as being forced to dig and break rocks for the roads because they were unable to pay the road tax. The poor implementation of the tax along with the work obligation under wretched conditions in distant places proved traumatic for peasants. There were even children as young as 12 sent to do road construction. Fakir Baykurt, as one of these boys, depicted in his memoirs how the road tax victims were recruited from among poor peasants by headmen, tax collectors, and gendarmes. Once, they were worked for more than twelve days. The taxpayers generally complained by saying, “This is government. It knows taking, but not giving.”Footnote 67

Peasants’ discontent with this tax frequently appeared in official documents as well as the letters sent to the authorities and the press. An eager politician wrote in his 1930 report that he had listened to peasants’ criticism of the road tax everywhere he went in central Anatolia and the Black Sea and Marmara regions.Footnote 68 The deputy reports on Konya and Aksaray from 1931 confirmed this by stating that the decline in agricultural prices had increased the burden of the road tax, while the mistakes and abuses of the tax collectors and detention of peasants who could not pay the tax in cash doubled the grievance. Moreover, peasants were being sent to more distant road construction sites than the laws prescribed. In a village in Konya, peasants who had been sent to a distant site by mistake were sent back without having worked. Just after they returned home, the governorship once again sent them to another distant site for days. These long trips on foot exhausted them before they had even started working and provoked harsh criticism of the government.Footnote 69

According to election district and party inspection reports from the 1930s, grievances related to the road tax were rampant throughout the Anatolian provinces.Footnote 70 Peasants deemed it an injustice. Collecting the same amount from all people, regardless of their income, did not comport with the state’s avowed populist principles. One peasant, in a letter to a newspaper, argued that because building roads was the task of the government, a special tax for this was preposterous.Footnote 71 Displeased with the single rate of the tax, low-income peasants demanded that taxes graduated according to income to make taxation more equitable.Footnote 72 They also pointed out that because roads primarily benefited the well-to-do, who could afford cars, trucks, and buses, requiring poor citizens to build and repair the roads was a grave injustice.Footnote 73

Almost everywhere, wrongdoings in the implementation of the road tax generated complaints. The RPP politicians in Yozgat and Kastamonu reported that the abuses of tax collectors upset the people.Footnote 74 Denizli deputy Mustafa Kazım stated in his report, “Compulsory works that were arbitrarily placed on the shoulder of the peasants under the pretext of the Village Law, and the forced labor obligation of the road tax that lasted about one and a half months under gendarmerie oppression and torture resulted in general discontent.”Footnote 75

Indeed, there were local administrators who exploited the unpaid labor of the peasants under the guise of the road tax. Peasants’ objections to forced labor lasting longer than the laws stipulated were pouring in to the central authorities and the press. The peasants of the İsabeyli village in Denizli, writing collectively to Köroğlu, complained that although they had already fulfilled their work obligation they were not permitted to return to their villages for eighteen days.Footnote 76 More tragically, in some places the taxpayers had worked about twenty days and sometimes in the construction of bureaucrats’ own houses or barns.Footnote 77 In the following years, similar complaints continued to be heard. Karaburun peasants in İzmir, who faced such a situation, collectively wrote to Köroğlu in March 1933 to ask for the help of the government.Footnote 78 In a similar vein, in August 1934 the same newspaper, in an article titled “We Received a Letter Signed and Stamped by Several Peasants in Safranbolu,” gave space to a poignant criticism that came from Safranbolu. The peasants, unable to pay the road tax in cash, had been put at the disposal of a road construction company. In their words, “we were held captive for twenty-three days, working fourteen hours a day.” The peasants queried whether this was a violation of the laws, which had limited the duration of the work obligation to eight days, working nine hours per day. They demanded the correction of this malpractice immediately.Footnote 79 Such letters indicate that peasants were aware of their rights, at least when they came into conflict with the state.

The peasants submitted complaints about the road tax directly to local party organizations, too. During the 1930s, the wish lists of provincial party congresses included several demands for a reduction in the road tax rate or tax relief for debt. For instance, thirty provinces sent their demands for road tax reduction to the Third Congress of the RPP.Footnote 80 At the Fourth Congress, the reduction of road tax rates or an amnesty for road tax debts appeared once again as major demands.Footnote 81

The wheat protection tax also caused public outcry in rural areas just after the tax entered into force on May 30, 1934, as evidenced by letters to local newspapers. In one, a peasant from Haymana (Ankara) described the deleterious effects of the tax on all peasants living in the town.Footnote 82 In another, a group of low-income peasants in Ilgaz (Çankırı) complained that although Ilgaz was a small town inhabited mostly by peasants and small farmers, its inhabitants were not exempt from the tax. They implored the Agriculture Ministry and the Prime Ministry to exempt Ilgaz peasants from this tax.Footnote 83 Indeed, as Köroğlu reported, peasants living in small and poor towns indistinguishable from villages were not exempted from the tax, and the newspaper had received several similar letters.Footnote 84

Tax collectors attempted to tax small village flour mills. In September 1934, the peasants of the Ortahisar village of Ürgüp complained that tax officials had levied a 12 percent wheat protection tax on them, contrary to the laws. They implored the government to respond to this unlawful act.Footnote 85 Subdistrict governors in Ankara also taxed village mills on the grounds that they were within the borders of the towns. The flour mill owners of these villages gathered in front of the Finance Ministry to protest this decision in July 1934.Footnote 86

The local party congresses in Afyon, İzmir, Erzurum, Çanakkale, Yozgat, Çorum, and many other provinces also recorded that peasants, whether wheat producers or not, requested that the government lower the rate of this tax and exempt the small flour mills in small towns that were tantamount to villages.Footnote 87 A more striking gauge of the tax’s impact on poor rural dwellers who lived on wheat and flour was a series of protests by women in front of government offices that occurred in central Anatolian towns in June 1934.

Concealment of property

When their demands were not met, peasants resorted to tax evasion. As David Burg writes in his comprehensive study on tax revolts in history, “avoidance, although perhaps not overtly insurrectionist has been a significant act of resistance to taxation.”Footnote 88 The peasants in Turkey also undertook several subtle avoidance strategies such as either not declaring their property or undervaluing it, and hiding their income and taxable assets.

The first way to escape taxes was to hide taxable properties. Contemporary observers related the common incommunicative and skeptical attitude of peasants in the presence of a stranger to tax evasion. In her village surveys from the early 1940s, sociologist Mediha Berkes (Esenel) noted how difficult it was to gather information about the peasants’ properties due to their concern on a possible tax on them.Footnote 89 Another contemporary sociologist, Yıldız Sertel, also wrote that because their most frightening nightmare was the tax collector, they hid the actual amount of their land, crops, and livestock.Footnote 90

In the case of the land tax, tax resistance took mainly two forms. The first was to avoid registering their land and the second was to underreport its size. As the prominent agricultural economy expert Ömer Lütfi Barkan documented and Finance Ministry reports confirmed, the peasants either did not report or underreported their landholdings. There were also many who did not register their lands under their own names in order to escape the land tax.Footnote 91

The mechanisms of livestock tax avoidance were roughly comparable. Peasants evaded the livestock tax by underreporting or not declaring their animals. The heavy taxes made the peasants, in one peasant’s words, thieves of their own property through cheating the state.Footnote 92 A contemporary wrote that nobody in his village in Burdur declared all of their livestock. His family, owning two oxen, one cow, one donkey, and five sheep, declared only a few of them, thereby saving 305 piasters.Footnote 93 Indeed, the number of animals recorded and taxed by the state decreased sharply throughout the country after the tax increase.Footnote 94

Peasant resistance to the livestock tax also can be read from the accusatory statements of the bureaucrats. In an advisory pamphlet addressing the peasantry, republican bureaucrats accused peasants who hid their animals from the state of being thieves and traitors.Footnote 95

Peasants devised several shrewd ways to conceal their animals. Many hid their animals in bedrooms, forests, hills, or caves when tax officials came to their village. Press accounts reveal such behavior. In the Titrik village of Giresun, for instance, a peasant hid his cow in the forest by tethering it to a tree. In the same village, the preacher concealed his sheep inside a cave in order to evade the livestock tax.Footnote 96 It was reported that there were peasant women who hid their goats in their houses, in the bed.Footnote 97 Many peasants managed to mislead tax officials by declaring that their sheep and goats were missing, or else below the taxable age.Footnote 98 Tax evasion by means of deception was so common that such acts became the subject of humor as stated at the beginning of this paper.

Livestock tax evasion was rampant, especially in the distant eastern uplands where animal husbandry was the main source of livelihood. Therefore, there were always great gaps between the real number of livestock and the number taxed. For instance, whereas according to the official records there were 5,000 sheep in the center of Bitlis, the real number was up to 40,000. Likewise, in Siirt the peasants declared only 12,000 sheep, but the true number was 25,000.Footnote 99 In Dersim, the number of declared and officially recorded farm animals was 68,875, but the peasants actually had around 170,000 farm animals. That is to say, the Dersim peasants managed to shelter about 100,000 animals from the livestock tax during the 1930s.Footnote 100

Though not as extensive as in the east, livestock tax evasion was widespread even in western and central Anatolia. In Konya the number of sheep declined from 2.5 million to 500,000 within four years when the livestock tax doubled between 1926 and 1930.Footnote 101 As a more micro-level example, while there had been more than 100,000 sheep in the villages of Çorlu three years earlier, this number had halved by 1930.Footnote 102 In Aydın, whereas the number of sheep and goats was 404,874 in 1929, this number decreased sharply to 272,318 in 1933. In the same time span, the number of sheep and goat in İçel decreased from 480,927 to 321,484; in Manisa from 824,043 to 621,214; and in Kars from 498,169 to 228,411.Footnote 103 These drastic decreases stemmed partly from peasants’ shift away from animal husbandry due to runaway taxes. However, they also reflect tax evasion. The heavier the taxes became, the more the animals were shifted to the informal economy. This was reversed in the following years with the gradual decrease in taxes, which rendered concealment unnecessary. Thus, the number of officially registered animals would climb rapidly in the mid-1930s.Footnote 104

The road tax was another front on which the peasants waged a war to escape its monetary and labor obligations. One way was to run from tax collectors and gendarmes. There was also a legal way to avoid the tax: to have additional children. Indeed, having five or more exempted a family from the road tax. Some peasants tried to have a few more babies solely for this purpose.Footnote 105

Peasants also exploited popular beliefs in evil spirits to scare the tax collectors. On tax collection day, they would often hide their livestock in the mountains, a practice that tax collectors called sirkat (stealing). Folk tales concerning sirkat were common, including one that told of a demon in the guise of a naked old woman who had attacked a tax collector on his way to a village. Indeed, such stories and old peasant women pretending to be witches could intimidate tax collectors patrolling in forests to hunt after animals hidden in out of sight locations.Footnote 106

Hiding out and bribing

The most widespread tax avoidance method was to disappear whenever the tax officials came to the village. A peasant in Ardahan told Lilo Linke, a foreign journalist who toured Anatolia extensively in 1935: “The peasants have nothing for themselves. They are so poor that they disappear into the mountains when the tax-collector comes near them.”Footnote 107 Indeed, coffeehouses and village rooms were the first destinations the tax collectors dropped by. Therefore, whenever they appeared near the village, these places were suddenly abandoned. In some villages the peasants set up alarm systems to detect approaching tax collectors. In Diyarbakır, for instance, when the Kurdish shepherds caught sight of a tax collector they spread the encoded news among the peasants by saying, “the wolf is coming!” (vêr gamê vêr in Zazaki Kurdish).Footnote 108 Those who heard this warning would conceal their animals, beds, blankets, quilts, and kitchen utensils and then vanish.Footnote 109

In the villages of Balıkesir, the peasants began to stand watch on the roads to escape probable raids by the gendarme after they heard that the security forces had started to detain those who did not fulfill their road tax obligations.Footnote 110 Fakir Baykurt’s memoirs also include such scenes. Underdeclaring their livestock by half, peasants were always on the alert for tax collectors during the tax season. If an alarm was raised, they hid their livestock in caves or closets for bedding called yüklük inside homes.Footnote 111

Although the corruption of the tax collectors was a significant problem, it did sometimes create an opportunity for the peasants to evade taxes. Tax collector salaries were low, and many were willing to accept bribes. For peasants, bribing tax collectors was seen as the lesser of two evils. By offering tax officials a certain sum of money or a quarter of the tax in kind or cash, peasants managed to avoid paying higher sums.Footnote 112

Protest and violence

When avoidance was not possible, the peasants did not hesitate to confront the tax collectors and the accompanying gendarmes. Individual protests were widespread, but collective tax protests also happened, albeit occasionally. In the eyes of peasants, tax collectors posed a threat to their economic well-being; they were agents of the urban elite who transferred the peasants’ daily bread to well-off city dwellers. Whenever a tax collector dropped in, the villagers would say, “The masters in the cities cannot eat stone!”Footnote 113 As is obvious from their ciphered message, “The wolf is coming,” the Kurdish peasants perceived the tax officials to be as dangerous as wolves. As foreign journalist Bernard Newman noted, in a large part of Anatolia the peasants regarded the tax collector as “an agent of the devil.”Footnote 114 Yıldız Sertel, a contemporary sociologist who conducted a field study in villages, wrote in her memoir that the peasants had deemed the state and its tax collectors “the angel of death.”Footnote 115

Such negative perceptions often turned into aggressive action toward tax officials. When there was no other way out, the peasants did not hesitate to raise their objections directly. Individual protests were widespread, but collective tax protests in front of the offices of the local authorities also happened occasionally. The wave of peasant women’s protests that spread throughout central Anatolia in 1934 stands out as a striking example of collective action. On June 10, 1934, fifteen women chanted slogans against the wheat protection tax in front of the government office in Kayseri. The security forces prosecuted some of them.Footnote 116 One month later, in July 1934, two other protests occurred: poor elderly peasant women in the İskilip district of Çorum and the Mudurnu district of Bolu rallied in front of government offices. According to the official who reported the events, “the women made a great fuss in the streets and created uproar.” The protesters, complaining of poverty, demanded that the local government decrease the wheat protection tax.Footnote 117 In July 1934, a group of small flour mill owners from several villages around Ankara gathered in front of the finance ministry and expressed their objections to the tax burden imposed on them by the district governors.Footnote 118

As a last resort, tax resistance took the form of attacks on tax collectors. Attacks when the tax collectors were on the road or even in a village, especially during or just after tax collection, were the most frequent pattern of violence against them. Newspapers of the time are replete with stories about unfortunate tax collectors who were beaten, stabbed, shot, or robbed by the peasants.Footnote 119 Sometimes the peasants confronted the tax collectors and security forces openly. For instance, in May 1929 peasants in a village near Urfa opposed a livestock census. Their quarrel with the tax collectors, escorted by gendarmes, degenerated into a serious fight, at the end of which some livestock owners managed to escape with their animals.Footnote 120 In April 1930, in the Girlavik village near Birecik, a peasant with a tax debt attempted to flee his home as soon as he realized that a tax official accompanied by gendarmes had arrived in the village. When the gendarmes surrounded him, the peasant shot one of them and the tax collector dead, and then managed to escape. Thenceforward, he lived in the mountains as the famous bandit Girlavikli Hino.Footnote 121

Such armed clashes were not peculiar to eastern Anatolia. In June 1934, some peasants from the Botsa village in Konya attacked the tax collectors and gendarmes who had expropriated their untaxed livestock and retook their animals. Another gendarme battalion then raided the village and beat the peasants, who in turn sued the tax officials and gendarmes.Footnote 122 Another incident of armed resistance occurred in the Manavgat district of Antalya at midnight on June 3, 1937, when the peasants attacked a gendarme battalion and killed one officer. Livestock tax evasion was the main cause of the incident.Footnote 123

In eastern Anatolia, tax-related armed attacks on tax collectors and gendarmes sometimes grew into local uprisings. Since the peasants made use of tribal community ties to mobilize other peasants’ support, these uprisings have mostly been explained with reference to Kurdish nationalism or tribalism. Undoubtedly, Kurdish nationalists engineered several rebellions during this period. However, a closer look reveals that the peasants’ subjective economic experiences and motivations played a more important role than nationalist motivations or the efforts of Kurdish organizations.

The Buban Rebellion is an example of how economic struggle underpinned the conflicts between state and society in the Kurdish provinces. In 1934, some villages in the Mutki district of Siirt (in Bitlis today) rebelled against the government. This incident, referred to as the Buban Tribe Rebellion, is usually considered to have been engineered by Kurdish nationalist groups. However, as in many other instances of peasant resistance in the region, this insurrection was not motivated by any ideological hostility to the Turkish state but rather by state control over the local order.Footnote 124 The peasants first objected and then rose up against the government when the tax collectors and the gendarmes attempted to collect the road tax and to force those who could not pay to work on road construction sites. In addition, the state’s policy of disarming the peasants left them defenseless against attacks by outsiders in the dangerous uplands. This also helped stoke the insurgence, which lasted about a year before the gendarme put it down. Less than one year later, in April 1935, Kurdish peasants in the Sason district of Siirt rose up against the government officials and security forces. Again, neither Kurdish nationalism nor foreign powers were behind this insurgence. The conflicts broke out due to the growing tension between tax collectors and poor peasants who subsisted on animal husbandry and illegal tobacco farming. The annual census of taxable animals in the spring always caused quarrels between the peasants and the tax collectors. The peasants frequently hid their animals, refused to report them, or prevented the officials from counting them by sometimes driving the tax officials out of their villages. The intervention of the monopoly officials in the peasants’ tobacco cultivation also fueled local anxiety.Footnote 125 As a result of pervasive non-cooperation, tax evasion, and smuggling in the mountain villages in Sason, the local governor, accompanied by the müftü (official Muslim scholar and community leader), visited the peasants to persuade them to cooperate with the government. During a dinner given in his honor, a furious fight between the officials and the peasants broke out over tax matters. The fight escalated into an armed clash in which the district governor was killed and the müftü severely injured. The peasants were accused of the murder and hid in the mountains to defend themselves against the security forces. News of the events, labeled by the government as a rebellion, spread to other villages in Sason, which then also turned to armed resistance against tax collectors and monopoly officials. Hence peasant resistance was transformed into a local uprising, which attracted many other peasants in the region facing similar problems.Footnote 126

Regardless of individual or collective resistance, in confrontations with the tax officials one important strategy was to mobilize collaboration among peasants. When tensions between peasants and tax collectors arose, gossip (mostly unfounded) accusing tax officials of immorality circulated through the grapevine. The peasants made use of this informal medium to produce and spread manipulative information in order to encourage disobedience by others, legitimize their own actions, or provoke a government reaction against the tax collectors. When taxes increased and the tension between peasants and tax collectors rose, rumors about tax officials or the government sprang up. In January of 1939, a few months after Atatürk’s death, a rumor alleging that a tax official had fired his gun into the air to celebrate the president’s death and chanted anti-regime slogans swept through the villages in Kars. However, an investigation revealed that this rumor had been put into circulation to set the local government against the tax collector because he had pressured peasants who had avoided paying tax.Footnote 127 Also in January 1939, a peasant from a village in the Trabzon province refused to pay his taxes; to mobilize other peasants to join his disobedience, he spread a rumor of a military plot in Ankara.Footnote 128 Another rumor alleged that the new president, İnönü, had killed three tax collectors during his tour of Kastamonu in December 1938. Rumor had it that based on a widespread denunciation of a tax collector, İnönü wanted to investigate the situation; when the accused tax collector and two of his colleagues attacked the president, he shot them in self-defense.Footnote 129 It is not possible to ascertain the source of the rumor; however, it is reasonable to think that peasants had sought to justify their hatred of and resistance to tax collectors by fabricating it.

Concluding remarks: limits of the republican modernization

Peasant resistance, along with other factors, forced the government to reduce the rates and scope of taxation during the 1930s. Facing widespread land tax evasion without an accurate land registry or cadastral information, the government left land tax revenues to local governments and cut the rate by about 35 percent.Footnote 130 In addition, widespread discontent and tax avoidance as well as a fall in livestock prices due to the Great Depression resulted in successive reductions in the livestock tax rates in 1931, 1932, 1936, and 1938, nearly halving them and removing horses and donkeys from the list of taxable livestock.Footnote 131 Similarly, in 1931 resistance to the road tax in both rural and urban areas forced the government to lower the rates by around 50–65 percent and to adjust the labor equivalent accordingly.Footnote 132 Finally, in view of the widespread complaints and protests against the wheat protection tax, all village wheat mills, including those near urban centers, were exempted from it in May 1935. Furthermore, the government forgave some outstanding agricultural tax debts in 1934 and 1938.Footnote 133

The main conclusion to be drawn from this is that the peasants negotiated the cost of modernization. The founders of the Republic laid the burden of the extensive modernization schemes and state building on the peasants. In an economy based on agriculture, the peasants were the main source of surplus. Despite the abolition of the tithe, the sharp increases in other agricultural taxes along with monopolies, commercialization of agriculture, and the Great Depression put the peasants’ livelihoods at stake. After the short-lived economic recovery in the early 1920s, tremendous political changes and economic crisis brought impoverishment and anxiety to poor and low-income peasants. The situation was exacerbated by the high price of the Republic that was billed to the peasants in the form of taxes.

This article, adopting a sociohistorical perspective to examine the intersection between the state’s fundraising via taxes as a corollary of modernization, state-building projects, and the peasants’ response to the situation, reveals one of the social dynamics that played a role in the making of republican Turkey. That dynamic was the peasantry, which managed to survive until the 2000s, albeit in numbers that have gradually declined. Rather than submit to the new state’s demands, the peasant population struggled to protect themselves. In addition to the infrastructural weakness of the early republican state, this social dynamic also deeply affected its transformative performance.

Peasants’ actions mostly fit into what is called “weapons of the weak” and “everyday forms of resistance.” Petitioning the provincial administrators or central government, they sought their rights and asked for redress. Appropriating the official discourse, they demanded the government live up to its commitments. Conveying complaints to the press was also a way to put pressure on the bureaucrats. Communicative strategies like rumors functioned as an informal media through which peasants expressed their aspirations and grief or sought to mobilize others for disobedience. When these ways fell short, peasants resorted to a series of actions that power-holders stigmatized as crimes. Some of these escalated to the point of violence.

Peasants’ prolific repertoire of everyday and mostly informal stratagems, which were not intended to change the social or political system, were not inconclusive. The widespread reluctance in paying taxes in conjunction with impoverishment in rural areas prompted the government to reduce agricultural taxes several times and to forgive a certain portion of tax debt. Undoubtedly, none of these measures signaled a wholesale retreat by the government. Nonetheless, these were serious concessions for a state in need for vast resources, which decelerated the modernization process by depriving it of funds vital to state projects. The last but equally important consequence arising from peasants’ everyday politics was the longevity of the peasantry not only as a social group but as a culture. This left deep marks on Turkish politics and culture in later decades by creating a social base, which gave rise, surely with other factors at work, to the conservative right and Islamist movements.