1 Introduction

Presenting a persuasive authorial stance is a major challenge for second language (L2) writers in writing academic research. An effective stance enables an author to claim solidarity with readers, evaluate and critique the work of others, acknowledge alternative views, and argue for a position (Hyland, Reference Hyland2004a). Lee (Reference Lee2008) also proposed that highly effective essays demonstrate the features of being “reader-oriented, evaluation ridden, dialogic, multi-voiced, and contextualized” (op. cit.: 264). Failure to present an effective authorial stance often results in poor evaluation which compromises a writer's research potential (Barton, Reference Barton1993; Hyland, Reference Hyland1998; Lee, Reference Lee2008; Schleppegrell, Reference Schleppegrell2004; Wu, Reference Wu2007). Typical weaknesses found in apprentice writers’ academic writing include the following: first, they usually present an inappropriately and monotonously subjective persona in their academic argument, most likely due to their less effective deployment of concessive and tentative claims (Barton, Reference Barton1993; Hood, Reference Hood2004; Hyland Reference Hyland2004a, Reference Hyland2006; Schleppegrell, Reference Schleppegrell2004; Wu, Reference Wu2007); second, they are less able to carry a consistent evaluation to strengthen their argument (Hewings, Reference Hewings2004; Hood, Reference Hood2006); and third, they tend to present descriptive narrative more than the critical evaluation academic argumentative writing calls for (Barton, Reference Barton1993; Hyland, Reference Hyland2004a; Woodward-Kron, Reference Woodward-Kron2002).

In addition to the challenges described above, each writer has his/her own disciplinary expectations to fulfill. According to Hyland (Reference Hyland1998; Reference Hyland2003; Reference Hyland2004b), those in the “soft disciplines,” i.e., the social sciences, confront graver challenges since the writers’ interpretive capability is critical to delivering convincing studies. Research has demonstrated significant differences in introductions from different disciplines (e.g., Samraj, Reference Samraj2002). Hyland (Reference Hyland2006) argued that the social sciences “give greater importance to explicit interpretation” than the hard sciences (op. cit.: 240), making great demands on the author's interpretive role and discursive performance in communicating with readers. This field is thus especially challenging for novice L2 research writers.

Despite the urgency of taking control of one's authorial stance, writing instruction for apprentice L2 writers does not typically offer explicit help in authorial stance-taking appropriate to their academic disciplines (Chang & Schleppegrell, Reference Chang and Schleppegrell2011). Instead, they are often provided with very general writing guidelines but not specific examples of how to write.

This study therefore adopted a “textlinguistic” approach to academic writing instruction to complement a typical corpus approach that is oriented toward exploring lexico-grammatical patterns at the sentence-level divorced from their context for proper interpretation (Flowerdew, Reference Flowerdew2005). Some researchers (e.g. Hunston, Reference Hunston2002; Widdowson, Reference Widdowson1998) have argued that a typical corpus-based approach to text analysis usually fails to account for the contextual generic features, which Flowerdew (Reference Flowerdew2005: 324) considered a “serious drawback in using corpus analysis”. A number of scholars have endorsed a textlinguistic approach to academic writing instruction (e.g., Charles, Reference Charles2007; Flowerdew, Reference Flowerdew1998; Reference Flowerdew2005; Lee, Reference Lee2008; Upton & Connor, Reference Upton and Connor2001), which Flowerdew (Reference Flowerdew2009) called a “discourse-based pedagogic application of corpora” (op. cit.: 396). The stance corpus proposed in this study adopts a discursive approach to allow the users to study both the linguistic realizations of stance at clause/sentence level and how stance meanings are made at the rhetorical move level. In Johns et al. (Reference Johns, Bawarshi, Coe, Hyland, Paltridge, Reiff and Tardy2006), Hyland argued that developing interpersonal meanings, such as those related to stance and voice, is integral to successful academic writing, and should start in undergraduate classes. It is also pivotal that this knowledge is made explicit, a “visible pedagogy” (op. cit.: 238), and be delivered in a way that allows “investigating the texts and contexts of target situations in consciousness-raising tasks …” (ibid).

Pedagogical designs following this line, while still few in published research, can be realized in tagging the move structures of a text to identify the social context in corpus data to inform the learners both of the local linguistic features and the larger textual context (Flowerdew, Reference Flowerdew2005). Alternatively, students can start with tackling the macro discourse-based tasks in class and then afterwards explore the linguistic realizations of the rhetorical moves using web concordancers (Charles, Reference Charles2007).

The proposed corpus tool comprises stance linguistic resources at three levels: the clause/sentence level, the move level and the text level. This accords with Flowerdew's (Reference Flowerdew2005) proposal that while concordancing software encourages more of a bottom-up approach which tends to ignore the larger generic features, the issue can be addressed by introducing “whole texts” (op. cit.: 326), a top-down approach. In this way, the lexico-grammatical items in a typical concordance can be compensated for by examining the “discourse-based move structures” in whole texts (op. cit.: 327).

This study therefore investigated the affordances of the web-based stance corpus to assist apprentice L2 writers, specifically those in advanced academic pursuits, to learn about stance expressions of various kinds in the rhetorical context of moves (Swales, Reference Swales1990; Reference Swales2004).

2 Theoretical framework

Several strands of research informed this study. The corpus is grounded in both functional linguistics theory and learning theory informed by corpus linguistics. The “engagement framework” (Martin & White Reference Martin and White2005; see Appendix A), one of the three sub-systems of the Appraisal system in Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), served as a major analytical tool for systemizing and making explicit the stance meanings for the learners.

SFL is oriented to the description of language as a resource for meaning, and is concerned with language as a system for meaning making (Halliday & Martin, Reference Halliday and Martin1993). The engagement framework therefore provides a metalanguage that refers to expansive and contractive devices which can be deployed to convey a stance. Martin and White (Reference Martin and White2005) posited that the difference between expansive and contractive expressions lies in “the degree to which an utterance … actively makes allowances for dialogically alternative positions and voices (dialogic expansion), or alternatively, acts to challenge, fend off or restrict the scope of such (dialogic contraction)” (op. cit.: 102).

Given that stance expressions are always deployed to serve a larger rhetorical purpose, Swales’ (Reference Swales1990; Reference Swales2004) descriptive framework of rhetorical move structures was introduced to the learners as a writing scaffold in planning their argument. The three-move structure is characterized as: “Establish a territory”, “Establish a niche”, and “Present the present work” (Swales, Reference Swales2004)Footnote 1. Identifying the rhetorical structure as guided by Swales’ model for novice academic writers helps them establish a foundational draft which they can refine and polish later.

Another theoretical contribution to the study comes from research on the educational value of corpus linguistics. Many corpus linguistics studies assume that interaction with corpora stimulates a constructivist learning approach and that learning is data-driven and probabilistic, encouraging active exploration in inducing patterns from the linguistic resources provided (e.g., Hunston, Reference Hunston2002; Johns, Reference Johns1991; Leech, Reference Leech1997; McKay, Reference McKay1980; O'Sullivan, Reference O'Sullivan2007; Tribble, Reference Tribble1991). A constructivist learning process requires the learners to engage in active discovery in formulating a question, working through the evidence found, drawing conclusions and formulating hypotheses (Chambers, Reference Chambers2007; O'Sullivan, Reference O'Sullivan2007). These cognitive activities are seen as particularly well suited for adult or advanced learners when engaged in advanced tasks such as academic writing (Johns, Reference Johns1991; McKay, Reference McKay1980; Tribble, Reference Tribble1991). Drawing on this line of research, the tool reported on here sought to provide learners with opportunities to actively explore both linguistic and discursive patterns in authorial stance-taking in expert writing by way of multiple annotated examples for the learners to investigate the patterns within. While the theoretical assumptions champion the multiple benefits of using a computer corpus in language learning, studies of pedagogical applications have reported mixed results. Overall, most studies have been concerned with the products rather than the processes of learning via the use of corpus tools (e.g., Bernardini, Reference Bernardini2002; Boulton, Reference Boulton2009; Cobb, Reference Cobb1997; O'Sullivan & Chambers, Reference O'Sullivan and Chambers2006). Among the few studies that have touched directly on how learning happens, Bernardini (Reference Bernardini1998) generalized some patterns which have emerged from students’ engagement with corpus tools, and reported that: (1) learning happens in cases where those linguistic items to be learned consist of fewer patterns of usage and meanings, (2) learners infer the patterns of lexical items more than those of lexico-grammatical items, and (3) they are able to notice patterns but are unable to describe what they have noticed. Hafner and Candlin (Reference Hafner and Candlin2007) observed that the use of the authentic materials which computer corpora usually host can be taxing for learners. Because of the vast linguistic data, they found that the learners’ search strategies tend to be inflexible and that they often stick with one query and few strategies. Sun (Reference Sun2003) studied the application of concordancers in identifying grammatical errors in close-ended questions and reported that the participants were prompted to adopt such cognitive strategies as “compare”, “group”, “differentiate”, and “infer”.

Other factors than the tool itself have also been found to play equally critical roles, for example, training, guidance and time (Cobb, Reference Cobb1997; Hafner & Candlin, Reference Hafner and Candlin2007; Kennedy & Miceli, Reference Kennedy and Miceli2001, Reference Kennedy and Miceli2010; O'Sullivan & Chambers, Reference O'Sullivan and Chambers2006; Sun, Reference Sun2003; Turnbull & Burston, Reference Turnbull and Burston1998), individual differences represented by the learners’ prior knowledge, rigor in engaging with the learning, and cognitive and concordancing skills (Bernardini, Reference Bernardini1998; Kennedy & Miceli, Reference Kennedy and Miceli2001; Sun, Reference Sun2003; Sun & Wang, Reference Sun and Wang2003; Turnbull & Burston, Reference Turnbull and Burston1998).

Clearly, more evidence is needed to ascertain how corpus tools benefit language learning, not merely in the products of learning but in how learning happens. More research is also needed into how a corpus approach may benefit and enhance discursive meaning-making, which is critical to writing pedagogy.

3 Research questions

The study investigates the potential of a corpus approach to advanced academic writing, focusing on the following questions:

1. How do apprentice L2 writers make progress in developing their drafts (i.e., “introductions” to research reports) in terms of changes in move (rhetorical structure) and stance (lexico-grammatical choices)?

A. How is their move and stance performance different after using the stance corpus?

B. How accurate are the learners in identifying and labeling stances used in their drafts?

2. How do they cognitively engage with a stance-tagged corpus-based tool to help them present an effective authorial stance?

3. How is their approach to learning (i.e., a top-down discursive investigation or bottom-up lexico-grammatical approach) related to their writing performance?

4 Methods

4.1 Participants

Seven Mandarin-speaking learners of English in their doctoral pursuit in the field of social sciences in a major mid-western US university were recruited for the study. The participants were not conscious of the concept of stance prior to taking part in the study. They might have exhibited some familiarity with move but, in practice, they were similarly not clear about how to materialize the concept in their introduction.

4.2 Tool design

The raw materials came from fifteen “introductions” of research papers in the social sciences, encompassing the following fields: education (5), political science (3), information and library science (3), and psychology (4)Footnote 2. The criteria for selecting these texts were first based on readability (those which covered general topics and required less background knowledge), clear move structure (with length ranging from 350 to 550 words) and stance deployment. This decision resulted from surveying a great number of articles over an extended period of time.

The fifteen introduction texts were first segmented by move structure and were annotated, then further broken down into clause units, each of which was assigned a stance value after the key lexico-grammatical items were identified and color-coded. While the data was analyzed based on Martin & White's (2007) engagement framework, the metalanguage in the theoretical framework was adapted to label stances in ways that made the meanings accessible to language learners, a result of user feedback from pilot testing. Appendix B gives the adapted version from the original linguistic framework.

As a result, the total number of clauses generated was 380, categorized into four stance typesFootnote 4 (“Non Argumentative” [NA] = 168, “High Argumentative” [HA] = 105, “Medium Argumentative” [MA] = 38, “Tentative” [T] = 69):

(1) “NA” stands for the making of a factual statement, the purpose of which is to give a descriptive account or background information.

(2) “HA” is similar to Hyland's “booster”, used mainly to assert and proclaim one's perspective.

(3) “MA” and “T”, similar to Hyland's “hedges”, are used to suggest likelihood or tendencyFootnote 5 (Hyland, Reference Hyland1998; Reference Hyland2004a; Reference Hyland2006).

Each clause example was linked to its extended rhetorical contexts organized according to Swales’ three moves. Table 1 gives examples of each stance type. Key lexico-grammatical items characterizing each stance are in bold.

Table 1 The four stance types and examplesFootnote 3

The corpus was designed in a web format for easy access. Prior to its launch, the stance corpus was subjected to several rounds of trialing in terms of both instructional content and interface design. After several revisions based on the feedback from the pilot testing and usability tests, the corpus included three major components along with other supplementary scaffolds:

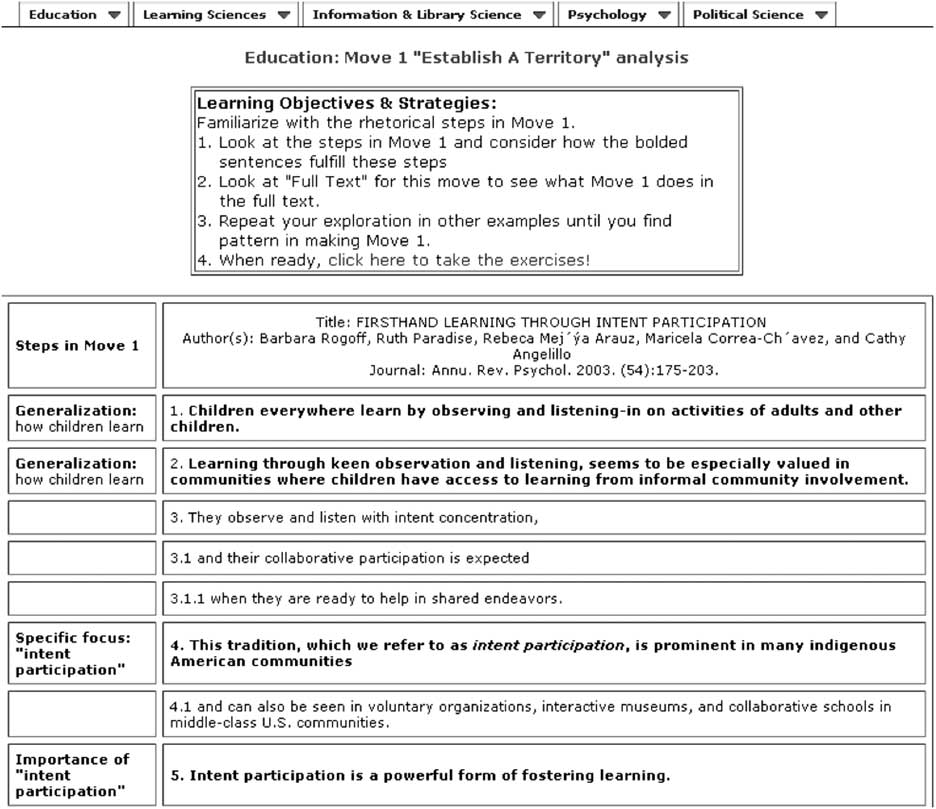

(1) Stance examples (clause/sentence-based): The texts were analyzed and identified clause by clause for their stance types. Figure 1 shows examples in move 1 which express “Higher frequency/level”, a sub-function of the MA stance. Key stance lexico-grammatical items are in bold and each clause, once clicked, takes the user to its extended context.

Fig. 1 Sentence-level examples of “Medium Argumentative” stance in move 1

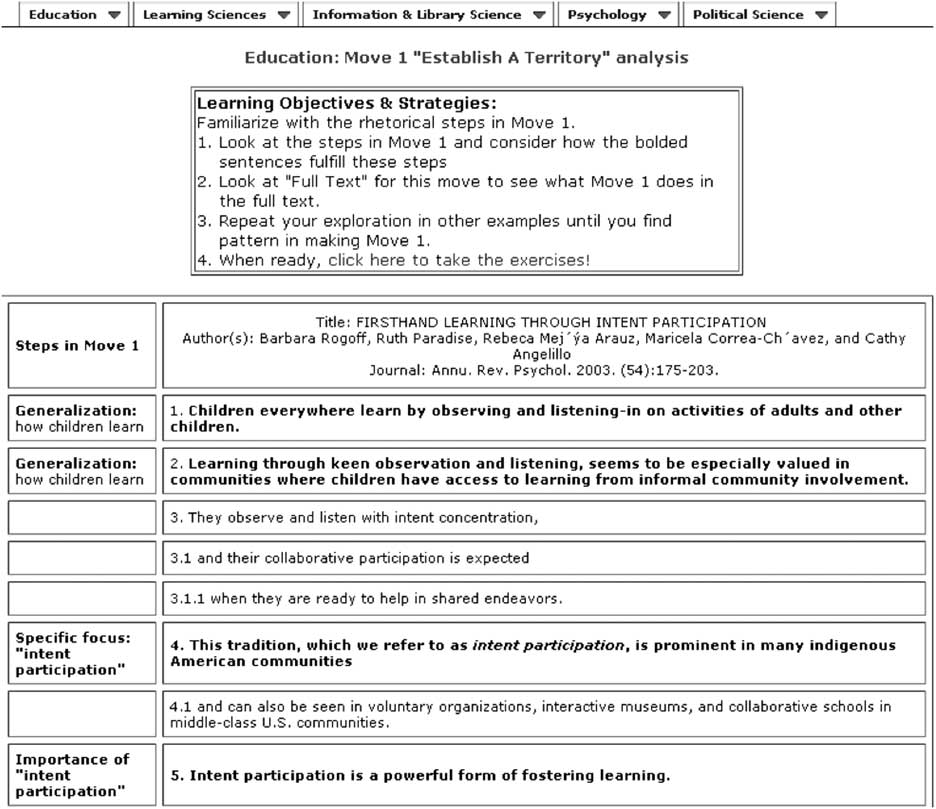

(2) Move examples: The “introduction” sections of the chosen research papers were rendered into three rhetorical moves. Figure 2 gives such an example. The steps to make move 1, “generalization” and “specific focus” are shown in the first column. The analyzed text is in bold and is shown in the adjacent column. The first two clauses make “generalizations” of the research, while the fourth and fifth sentences zero in on the specific focus of the study.

Fig. 2 Annotated move 1 example

(3) (Con)text examples: The integrated examples in Figure 3 show a move example, annotated with stance types (column 3) and move-making steps (column 2), along with textual enhancement of key stance lexico-grammatical items in each clause (column 4).

Fig. 3 Integrated text example

The complexities involved in mastering stance knowledge can be daunting. To construct foundational knowledge, a small corpus was therefore considered sufficient. In consulting the corpus, the learners were required to understand how each instance was encoded and further, how each instance functions in an extended context in terms of stance deployment. Having a good command of the total 380 instances of stance expressions is a challenging task and, if accomplished, the learners may establish a mental schema of stance-taking, on which they can further build new knowledge and expand what has been learned.

A number of researchers have proposed a small corpus for language learners given that the learning goals are those that smaller and specialized corpora might better serve (Bloch, Reference Bloch2009; Chambers, Reference Chambers2005; Flowerdew, Reference Flowerdew2004, Reference Flowerdew2005, Reference Flowerdew2009; Kennedy & Miceli, Reference Kennedy and Miceli2001; Todd, Reference Todd2001). Flowerdew (Reference Flowerdew2005) demonstrated that small corpora serve pedagogical purposes better because the teachers can draw on examples closer to the students’ needs. The development of the current corpus therefore did not seek to provide comprehensive knowledge of authorial stance-taking as there is really no limit to the myriad ways of making such meanings.

4.3 Procedures

The learners participated in two orientation sessions (overview and tutorial) and three writing sessions. First, the orientation sessions gave an overview of the experiment and the corpus tool. Learners were also given time to explore the tool and to do small exercises related to stance to get an initial impression of what stance is and how to orient themselves in the corpus tool. In the writing sessions, the core part of the experiment, the stance corpus was present at all times and was used as a stand-alone resource. The participants interacted with the corpus whenever they needed to consult it about move and stance. They spent one hour composing or revising their introductions and analyzing their stance expressions using a worksheet (Appendix C), after which they were asked to think aloud. They were prompted by screen-capture clips that captured the screen activities of the first hour to try to verbalize the cognitive processes they had just applied in learning.

5 Data analysis

The study set out to investigate whether the apprentice L2 writers progressed and, more importantly, how. Multiple methods of analysis were employed to answer the questions and provide a richer description of the learning experience:

5.1 Evaluating the quality of move and stance use in the pre- and post-drafts

The experiment began by collecting the participants’ research paper introductions previously written as a pre-test text. During the intervention, they participated in a total of three sessions and generated three developing drafts. The analysis compared the pre-test text and the final draft of the three developing drafts, the post-test text, to answer whether they had learned and shown improvement.

In evaluating the learners’ written products, both rhetorical move and stance deployment were carefully assessed. Two raters were involved in the evaluationFootnote 6. In evaluating move structure, both raters followed Swales’ (1990; 2004) CARS model. A rating scale, approved by both raters, was developed for this purpose (see Appendix D). With respect to stance evaluation, each rater adopted the framework they had been using based either on their professional training or from their teaching experience. Unlike Swales’ model, which has been widely operationalized in writing instruction, instruction about stance may not be as prevalent and even if offered, it can vary based on the instructor's conception and belief about what stance signifies. It is also true that divergent theoretical constructs referred to as “stance” exist (e.g., assumptions from the fields of linguistics and language education). Therefore it was more realistic to allow both raters to adopt the frameworks they had previously been using. The researcher applied the theoretical framework used to analyze the texts in the corpus tool (Martin & White, Reference Martin and White2005; see Appendix A), while the second rater applied Hyland's concept, “hedge” and “booster”, in her evaluation (Reference Hyland1998; Reference Hyland2004a; Reference Hyland2006); (see Appendix D). Even though it seems that the two raters adopted different perspectives, Hyland's and Martin & White's constructs are complementary. Applied together, Hyland's version is a useful pedagogical tool while Martin & White's version is a useful analytical and explanatory framework to support pedagogy.

In light of this, the two raters assessed the overall quality of the pre and post-test drafts to establish a big picture of the participants’ performance.

5.2 Analyzing moves and stance expressions in the three developing drafts

Using close text analysis, this part aimed to track the internal development specific to each learner. All the developing texts were closely and iteratively compared and analyzed for both emergent and recurrent patterns to understand what had been learned and what remained challenging.

5.3 Calculating the level of accuracy in identifying and labeling stances per written clause

The learners were presented with “self-analysis” sheets (Appendix C) where they divided their text into three moves which were further divided into clauses, each of which was then assigned a stance type. This part of the analysis calculated the probability accuracy for every stance identified per clause to evaluate how accurate and conscious they were of stance.

5.4 Coding and tallying stimulated recall protocols for cognitive learning activities

The study employed O'Sullivan's (2007) list of cognitive skills in investigating process-oriented teaching and learning with the aid of corpora. These cognitive skills involve ‘predicting’, ‘observing’, ‘noticing’, ‘thinking’, ‘reasoning’, ‘analysing’, ‘interpreting’, ‘reflecting’, ‘exploring’, ‘making inferences’ (inductively or deductively), ‘focusing’, ‘guessing’, ‘comparing’, ‘differentiating’, ‘theorising’, ‘hypothesising’, and ‘verifying’ (op. cit.: 277). The list was recommended to gauge the extent to which a constructivist and metacognitive approach to learning was effective. According to Boulton (Reference Boulton2010: 20), O'Sullivan's list “provides an impressive list of cognitive skills which data-driven learning (DDL) may be supposed to promote…”. This cognitive scheme was considered appropriate for this study because it typified those cognitive activities involved in learning with computer corpora, which is precisely what this study sought to explore.

5.5 Documenting the frequencies of the tool functions used

Each learner was tracked for the time spent on the different components they visited in the three sessions.

6 Results

The report of the results corresponds to the research questions which are recast as the following:

6.1 Whether progress was made after the intervention

Generally, improvement was found in the learners’ deployment of both move and stance, with some more salient and others more subtle.

6.1.1 Move performance

In contrast to their pre-test drafts, almost all of the writers exhibited explicit move structures in their final drafts and became more conscious and mindful in planning their rhetorical structure in their introduction. Table 2 summarizes the evaluation by the two raters. In the case of PU, for example, regarding stance performance, he moved from 0 to 2 on the first rater's scoring scale and from 4 to 6 on the second rater's scale. For move, he moved from 1 to 3 for the first rater and 1.66 to 3.66 for the second. Appendix E gives an example of their scoring scales and the scores assigned.

Table 2 Evaluation of the pre- and post-test drafts

On closer inspection, even though most of the participants were able to model on the three move structures, some of their claims were either not well developed or were not supported with evidence. It seems that mature writers do not merely rely on their linguistic or rhetorical caliber, but also rely significantly on their experience of conducting well-rounded research to produce a satisfactory argument. For instance, PU did not yet have a complete research agenda in mind and so the demand of the three-move rhetoric seemed stretching. By comparison, both SY and CG were more advanced in their research and were able to argue with confidence the issues they aimed to tackle along with the steps they planned to undertake to conduct their studies.

6.1.2 Stance performance

Regarding stance expressions, most participants showed improvement (Table 2). Among them, PU and HG obtained consistent ratings from the two raters and exhibited the greatest improvement. DG showed good improvement and was more favorably rated by the second rater whose stance performance scores progressed from 1 to 5. A paired t-test indicated that for both ratings, significant difference was observed from the pre-test to post-test at a 5% significance level.

Overall, the evaluation reveals that after engagement with the corpus tool, the subjects became more effective in deploying stance to fulfill distinct move rhetoric. Their stance deployment was more explicit with authorial interpolation, in contrast to their pre-test drafts where the arguments were often narrative-like with an obscure stance, a tendency usually spotted in both novice L1 and L2 writers (Woodward-Kron, Reference Woodward-Kron2002).

6.2 What were the recurrent patterns associated with the learning of move and stance

This part of the results is intended to understand the learners’ developing knowledge about move and stance in addition to the fact that learning did happen as indicated by the results reported above. To this end, close text analysis of the learners’ patterns in move and stance learning was conducted iteratively for recurrent patterns in writing. The results revealed that for move learning, the conceptual move structure did prompt the learners to be conscious in deploying their argument in alignment with the three specific rhetorical purposes. They all showed good connection of their ideas and explicit three-move rhetoric.

In terms of stance learning, the following recurrent patterns were observed:

(1) The learners were found to excel in extreme stances related to proclaiming (HA) and factual (NA) expressions more than in the intermediate ones (MA and T) which concede or make the argument tentative;

(2) The learners exhibited problems with handling and identifying stances when projection clauses were involved;

(3) The learners attended to how meanings radiate and are prosodic; and

(4) The learners appealed to intuition and intended meaning for stance judgment, not based on the key lexico-grammatical items identified and highlighted in the corpus.

6.3 How accurate the learners were in identifying and labeling stances per clause written

The learners were found to score higher for HA and NA stances, the two “extreme” stances, as opposed to the other two, MA and T, that is, intermediate meanings used to make concessions and tentative expressions. On average, these learners were able to identify, in the order of probability accuracy, NA (at 29.25%), and then HA (at 17.33%) more accurately, while MA and T were consistently lower in accuracy. Table 3 gives the probability accuracy of the individual learners’ stance understanding. Take DG as an example. He used a total of 33.33% of HA of all the stance types he deployed. Of those he labeled as HA, 83.33% were accurate. The ratio between actual use and conscious identification of HA stance was therefore 0.86 to 1, and the probability accuracy was 23.89%, ranked second to SY at 27.50%. In terms of MA, DG over-identified MA stance by 2.66 times, which means, apart from the MA stance he used and identified accurately, he also went over those and (mis)identified other stances as MA. All considered, his probability accuracy was lowered to 14.25%.

Table 3 Stance identification accuracy percentage

A positive relationship was established between those who were more accurate in identifying stances (DG at 21.44%; HG at 17.25%; CG at 16.95%; PU at 16.13%) and those who performed better in the pre to post-test drafts (in the order of improved performance, PU, HG, and DG). We can therefore conclude that with improved stance and move knowledge, the writers demonstrated effective argumentation in their writing. The relative weakness in the intermediate stances, however, highlights the importance of directing more attention to helping L2 writers make concessive or tentative claims in future pedagogical designs.

6.4 Frequent cognitive learning activities

This part reports the results regarding the types of cognitive activities most often encouraged while interacting with the tool. Table 4 shows average individual cognitive activities used in the three sessions. The cognitive activities are organized from higher order thinking skills as they are relevant to corpora consulting behavior, to lower order skills. The participants were found to apply “make sense” (28.48%), “explore” (18.14%), and “reason/analyze” (16.71%) more than the others, with considerable marginsFootnote 7. The cognitive skills least applied were “predict/hypothesize” and “make inference”.

Table 4 Frequency of cognitive activities

(P-H: Predict/Hypothesize; MI: Make Inferences; V: Verify; R-A: Reason/Analyze; MS-I: Make Sense/Interpret; M: Model; E: Explore; R-R: Remember/Review; G: Guess).

As previously mentioned, a positive correlation was found between performance and stance accuracy and vice versa. However, no such positive correlation was found between the cognitive types used and performance. Almost all of the users were eager to “make sense”, “explore”, and “reason/analyze”, while those more advanced corpus-related consulting skills presumed to be stimulated by a corpus tool, such as “predict/hypothesize”, “make inference” and “verify,” were less frequent, running counter to the theoretical propositions, which suggest that a concordancing approach affords inductive learning and drives learners to pose a hypothesis, test it, and draw inferences from the exploration. Some possible explanations are offered in section 7.

6.5 Frequent tool functions used

The participants were found to access the integrated “(con)text examples” most frequently (43.85% of the total time engaged), followed by “move examples” (24.26%), and “stance examples” (15.15%). Instead of probing class/sentence-based linguistic resources to learn about stance expressions, which is commonly expected in using corpus tools, the learners were found to investigate the context more and to do so quite intuitively.

The different threads of results yielded interesting pictures related to stance learning and are discussed in depth below.

7 Discussion

The study demonstrated that a positive relationship existed between the learners’ stance and move learning and their overall writing performance after interacting with the stance corpus. Those who were more accurate in identifying stances were also those who performed better from the pre- to post-test drafts. We can therefore conclude that with improved stance and move knowledge, the writers demonstrated effective argumentation in their writing. The introduction of this innovative corpus tool also revealed that the users consulted discourse-based examples more than the sentence-based linguistic resources, and their improvement was not contingent upon their applying advanced cognitive skills when interacting with the tool. Lee (Reference Lee2008) explained that the writers’ use of interpersonal meanings, both in terms of quality and quantity, was closely related to the quality of their argumentative/persuasive writing, and that this piece of knowledge should be emphasized in academic essay instruction. The L2 writers in the study were found to adopt the metalanguage in conceiving and articulating their stance deployment, which in turn enhanced their consciousness about authorial stance-taking.

The study observed a few recurrent phenomena in the learning experience as discussed below.

7.1 The learning of the extreme stances (i.e. HA and NA) more than the intermediate ones (i.e., MA and T)

A few students in the study were found to hold a misconception about stance, which compromised their performance. This misconception dictated that effective stance-taking signifies the use of proclaiming devices to tune up the author's voice, which misled these learners to make proclamations whenever they found the need to. Authorial stance was accordingly reduced to a simplistic interplay between assertion and factual statement. However, the deployment of effective stance goes beyond such a simple combination. To hone the writers’ skills in effective stance-taking, this misconception should be dealt with as early as possible.

In addition, the learning of the “intermediate” stances may be fundamentally more difficult than learning about HA and NA. This finding coincides with Hyland's studies (Reference Hyland1998;Reference Hyland2004a; Reference Hyland2006) that “hedging”, a linguistic device much akin to the spectrum of the MA and T stances introduced in this study, is most challenging for L2 learners, whereas “booster”, similar to the HA stance, is not. This can be justified by the fact that the linguistic resources that go into the making of MA and T are more complex and at times less definite. Future research therefore needs to focus on these two stance expressions to respond to the writers’ more urgent challenge. For example, Chang and Schleppegrell (Reference Chang and Schleppegrell2011) demonstrated that the use of “intermediate stances” is found to be highly effective in making rhetorical move two (“establish the niche” of the current study) or in transitioning from move one (“establish the territory”) to move two in order to gradually introduce the gap in the studies (op. cit.: 148). In future pedagogical designs, students can therefore be informed more explicitly about the rhetorical functions the intermediate stances usually serve.

7.2 The application of lower level cognitive activities

While positive learning outcomes were found, no positive relationship can be established between performance and the application of inferential skills in consulting the tool, the core cognitive type presumed to be prompted by corpus-based tools. Making inferences was infrequent among the learners and even when it was observed, it did not dictate better learning or deeper understanding. The learners mainly managed to “explore” the new concepts and the tool, “make sense” of the linguistic data, and “reason” about it in the limited time they had to engage with the new knowledge.

It seems reasonable that such higher order cognitive skills as making inferences have to be grounded on some initial exploration and sense-making to lay the groundwork for advanced cognitive strategies. Seeing this, the more frequent application of “making sense” and “exploring” cognitive processes served the learners well in comprehending the declarative aspect of the knowledge. The third most frequent skill, “reasoning/analyzing”, allowed the learners to venture a little beyond the factual domain to engage in the conceptualization of the knowledge by comparing and contrasting.

This finding is also aligned with emergent research which has generally explicated that multiple issues are involved in using corpora tools to learn, ranging from training, guidance in the use of concordancing strategies and individual learning styles, to habits (Hafner & Candlin, Reference Hafner and Candlin2007; Kennedy & Miceli, Reference Kennedy and Miceli2001; O'Sullivan & Chambers, Reference O'Sullivan and Chambers2006; Sun & Wang, Reference Sun and Wang2003; Turnbull & Burston, Reference Turnbull and Burston1998). As this study observed, individual learning styles did affect the learning outcomes to a certain extent. Kennedy and Miceli (Reference Kennedy and Miceli2001) illustrated that different learning styles, habits, and rigor in learning can set the learners’ performance apart to a large extent. In this study, among equally competent learners, those who were more attentive and careful tended to outperform those who were not. Conversely, for those who came with a strong preconception about what was to be learned or who were inattentive and careless, the learning could be compromised more than for those who were not.

7.3 The frequent access of discursive scaffolding

Quite intuitively and most frequently, the learners accessed the context examples to make sense of how stance can be constructed. They were drawn to how meanings radiate, and how the strength of stance is built up and reinforced. It seems that the making of stance meanings became so intertwined with the discursive considerations that to really make sense of stance deployment, these learners found the need to explore the discursive aspect in making their stance meanings. This suggests that the learning of stance is critically contingent on the surrounding contexts; therefore a “top-down” approach seems more useful than a lexis- and clause-based approach.

On the other hand, while these authentic context examples were indicated to be very helpful, more support was needed. The users pointed out difficulty in understanding the advanced text while required to learn and write at the same time. More assistance should therefore be implemented to alleviate their cognitive burden in dealing with all three tasks simultaneously. Such support can range from training in inferring patterns, scaffolds to assist in understanding the authentic texts, feedback systems to enable noticing the gaps in their knowledge and to support self-correction, to quick lists of key stance-taking tokens.

The current study has established important findings in the research of interpersonal meaning-making in academic writing pedagogy. A few suggestions and recommendations for future investigations include: first, in learning about authorial stance-taking, L2 writers encountered more difficulty in making intermediate expressions. Instruction on semantic stance-taking should therefore direct focus to making intermediate stance expressions. Second, learners’ learning strategies in using a corpus-based tool should be carefully scaffolded to maximize the potential of such an approach in an aim to achieve deeper learning. At the initial stage of learning a new concept, as this study reveals, expecting learners to start inferring patterns seemed too demanding. The design or instruction should additionally find a way to provide feedback to remind the learners when they are shrouded in misconceptions and are less rigorous in their learning strategies. More training prior to learning may also help to preempt these issues and maximize the benefits of using such a corpus tool. Third, the study illuminates the need to augment a traditional lexico-grammatical approach in corpus use with discourse-based instruction in academic writing. The very process of argument is inherently discursive, and L2 writers are in much need of such resources and support. As the study shows, when the participants were asked to investigate stance meanings, they accessed (con)text-based examples more frequently than sentence-based ones in order to explore the prosodies of stance meanings.

8 Limitations of the study

The researcher observed some limitations in terms of the time allowed for learning, the size of the corpus, the need to include a feedback system and a control group. For future investigations, it would be interesting to engage the learners in using the tool for an extended period of time to observe if their patterns of cognitive activities change over a longer term, particularly after moving beyond the phase of factual or declarative learning. After the learners become familiar with stances, how will they use the tool to refine their understanding of stance? What role will making inferences play in the intermediate or advanced phases of stance learning? These are inquiries worth pursuing in the future.

Also, the corpus could be expanded in two areas in particular: the expansion of discipline-specific examples and of preferred argument styles. The participants remarked that they would be more motivated if the examples were highly relevant in terms of disciplinary areas and argumentative styles. On the other hand, scaling up the corpus is challenging as both the analysis and annotation have to be done “manually”, which is immensely time-consuming (Flowerdew, Reference Flowerdew2005). The application of such a pedagogical practice, therefore, is more beneficial to groups of learners of homogenous disciplinary backgrounds.

The corpus could be further improved if a feedback system were added to evaluate learners’ progress and suggest better options in their writing. A simpler solution would be to compile a Q & A list to help learners who are not progressing.

Another limitation involves the lack of a control group in the experiment, which, if implemented, might have provided a better perspective on the intervention. On the other hand, the analytical basis of the current study was intended to investigate more closely and deeply how novice research writers develop their writing. On this premise, as an experimental design might not address this issue as effectively, an in-depth qualitative approach seems more appropriate.

9 Implications

The design of the corpus presumed that the users would concentrate on the clause/sentence-based stance examples and slowly move up to the extended texts. However, the study observed quite different behavior in stance learning, that is, the writers intuitively and most frequently accessed the (con)text examples. This demonstrates that the making of stance meaning is so intertwined with and embedded in the rhetorical contexts that sentence level knowledge becomes less pertinent. Indeed, each utterance is only meaningful when seen in the rhetorical context in which it is embedded (Chang & Schleppegrell, Reference Chang and Schleppegrell2011). For future instructional design, this discursive aspect of stance knowledge may emerge as the core materials, surrounded by and complete with other thoughtful scaffolds.

Another issue concerns what it means to induce patterns in such instruction. The ability to infer suggests that the learners are able to see beyond the factual information and can examine and reflect on the process of generating patterns. But the participants in the study were not only new to the concept but also struggled, to varying degrees, with conceiving their argument in a second language. A task so demanding, which includes reading to learn and composing research arguments, invariably takes up so many cognitive resources, and can compromise the use of more advanced strategies. Future designs may need to reconsider what inference-making entails in terms of making discursive meanings in argumentative writing, which can better frame and inform pedagogy.

10 Conclusion

This exploratory study sheds light on L2 writers’ writing processes and performance involved in the development of rhetorical, semantic and discursive aspects of writing with the aid of a corpus tool. These are challenging issues for apprentice L2 writers and a no less challenging agenda to undertake in research. While numerous existing studies have investigated lexical or lexico-grammatical features in writing, these cannot fully address the grave challenges these writers experience, as writing is a continuum from mobilizing precise linguistic resources to conceiving a persuasive argument. To offer instruction grounded in meaning-making and, at the same time, encourage active exploration, computer corpora have come to the fore, but adaptation is also needed. Built on the premise of sentence unit, typical computer corpora deliver authentic linguistic instances for the learners to explore. For the purpose of this study, a specialized corpus was developed which expanded on the typical computer corpora to include textual instances to support the development of making stance expressions. In addition, all the resources were instructionally rendered and tagged to scaffold learning.

This study has demonstrated that a stance corpus based on a textlinguistic approach afforded the apprentice L2 writers enhancement of their consciousness of stance-taking, which resulted in improved research argumentation. Additionally, the participants were found to be in much need of discursive resources and support in developing their argumentative writing. On the other hand, given the depth and the complexities of stance knowledge, the participants were preoccupied with applying lower level cognitive activities associated with the learning of facts. More advanced cognitive skills which may afford them the opportunity to become metacognitive were far less frequently observed. For future research, given more time for learning, training and refined scaffolding, it would be interesting to see how the writers can venture beyond the learning of facts, exhibit more advanced cognitive skills, and develop more nuanced academic arguments.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Pedagogical adaptation of the Engagement System

Appendix C

Self-analysis Sheet

Evaluate your learning:

(1) Divide your ‘Introduction’ into three moves.

(2) Then break your writing into sentences or clauses (visit “Start with clause” under “Tutorial,” “Teaching & Learning Strategies”).

(3) Start assigning stance values!

An example is given below.

(*NA = Non-Argumentative; HA = High-Argumentative; MA = Med-Argumentative; T = Tentative)

Appendix D

Rating scale for MOVE and STANCE

MOVE: For both raters

STANCE

THE RESEARCHER:

THE SECOND RATER:

Appendix E

Move and Stance evaluation

Move structure: an example

Rater 1

Rater 2

Stance deployment: an example

Rater 1

Rater 2