A decade into the “postconflict” period (2006), Guatemala remained a dangerous place for women. Six to seven hundred women were being killed annually, in a country with a population smaller than that of New York State. Gender-based homicide was the extreme end of a spectrum of violence against women (VAW) (Menjívar Reference Menjívar2011),Footnote 1 facilitated by government officials who viewed VAW as normal, private, or unworthy of investigation (Sanford Reference Sanford2008; Trujillo Reference Trujillo, Fregoso and Bejarano2010).

It was thus a step forward when, on April 10, 2008, the Guatemalan Congress passed the Law Against Femicide and Other Forms of Violence Against Women (2008 VAW Law), which criminalized and assigned high sentences to physical, psychological, economic, and sexual violence and gender-based murder (femicide). This law also mandated measures to increase women's access to justice, including the creation of specialized VAW courts. While there were significant gaps between the law, its implementation, and its effects (Beck Reference Beck2021), the law established VAW as a matter of public concern and provided women political capital in their struggle to live lives free of violence.

A recent scholarly consensus points to the importance of strong, autonomous domestic women's movements for the passage of such gender equality reforms as Guatemala's 2008 VAW Law, alongside political opportunities in domestic and international arenas. But this begs the question, where do movement strength and autonomy come from? What is a nascent women's movement seeking gender equality reforms to do if it has limited strength or autonomous organizing experience, which is often the case in transitional and developing-country contexts?

A long-term analysis of the Guatemalan women's movement's anti-VAW activism demonstrates that one potential road forward is through the deployment of a “politics of patience” (Appadurai Reference Appadurai2002), which allows women's movements to cultivate strength and autonomy while also incrementally shifting their environments to their future advantage. A politics of patience is rooted in the pursuit of cumulative, incremental victories, pragmatic partnerships, alongside conscious efforts to build movement cohesion, networks, and knowledge.

By advancing Arjun Appadurai's (Reference Appadurai2002) concept of the politics of patience and applying it to the field of women's mobilization, this article reinforces findings about the importance of domestic women's movements for gender equality reforms and extends the literature on women's movements and gender equality reforms in two ways. First, the concept of politics of patience offers an example for feminist scholarship that explicitly attends to the strategic and temporal dimensions of domestic women's movements, at times overlooked in the admirable search for significant causal variables using quantitative analysis (Goetz and Jenkins Reference Goetz and Jenkins2016). Second, it focuses not just on the effects of movement strength and autonomy but also on the analytically prior issue of the origins of these critical movement characteristics. A long-term periodization of the Guatemalan women's movement shows that a politics of patience allowed the movement to slowly gain strength and autonomy over time through the very act of pushing for incremental changes on which it could later build. The movement's legislative success in 2008 was therefore the product of political momentum generated over decades, demonstrating the iterative and potentially reinforcing nature of social mobilization and political reform. This article therefore contributes theoretically by buttressing the emerging scholarly consensus on the importance of strong, autonomous domestic women's movements for gender equality reforms while putting this literature into conversation with more historical and anthropological accounts that center on movements’ political practices.

Next, I discuss my theoretical framework and research methods. I outline the context of women's mobilization and gender equality reforms in transitioning and post-transition Guatemala. I then analyze the long-term development and strategies of the Guatemalan women's movement by tracing four critical periods of mobilization, from the birth of the autonomous women's movement in the 1980s through the passage of the 2008 VAW Law. I conclude by discussing the implications for domestic women's movements and gender equality.

THEORIZING WOMEN'S MOVEMENTS AND GENDER EQUALITY REFORMS

What determines the adoption of gender equality reforms like anti-VAW legislation? Scholarship focusing on developing countries, particularly countries that have recently transitioned from authoritarianism or armed conflict, points to factors related to the domestic and/or international political contexts and those related to domestic women's movements—particularly to their levels of strength and autonomy. In this section, I discuss each before putting this literature into conversation with the central focus of this article: women's movement's long-term political practices.

Political Contexts and Gender Equality Reforms

Contextual factors have been hypothesized to increase the likelihood of gender equality legislation. Some scholars, for example, have focused on the availability of domestic insider advocates, including women legislators (Lovenduski and Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris1993; Murphy Reference Murphy1997), leftist legislators (Dahlerup and Leyenaar Reference Dahlerup and Leyenaar2013), or sympathetic bureaucrats, often in women's policy machineries (Franceschet Reference Franceschet2010; McBride and Mazur Reference McBride and Mazur1995). Others have focused on the international arena, highlighting the importance of international norms promoting gender equality for reforms in developing countries (Towns Reference Towns2010) and the role of transnational networks (TANs) in pressuring governments from above, below, and sideways (Ferree and Tripp Reference Ferree and Tripp2006; Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998; Reilly Reference Reilly2007).

Scholars also highlight the political opportunities that come with transitions from conflict or authoritarianism. For example, sub-Saharan Africa scholars note that large-scale internal armed conflicts may reorganize gender roles in ways that afford women new social, economic, and political roles. They may also spur women's mobilization in the context of conflict and/or peace building. Openings in the form of peace negotiations, political liberalization, and constitutional reforms make the state more permeable to both domestic and international demands, including the gender equality demands that have been more commonly promoted since the mid-1990s (Berry Reference Berry2018; Hughes and Tripp Reference Hughes and Tripp2015; Tripp Reference Tripp2010, Reference Tripp2015). Similarly, authoritarianism and subsequent political liberalization provide gendered political openings. Latin American scholars, for example, note that authoritarian governments may create unintended openings for women's autonomous mobilization by repressing male-dominated political organizations and viewing women as unthreatening (Alvarez Reference Alvarez1990; Friedman Reference Friedman1998; Jaquette Reference Jaquette1989). Democratization thereafter opens up possibilities for women's movements to push for gender equality reforms, allowing them to ally with parties and legislators in the context of elections or with sympathetic bureaucrats in new women's policy machineries (Waylen Reference Waylen2007a).

Strong, Autonomous Domestic Women's Movements and Gender Equality Reforms

The foregoing opportunities may increase the likelihood of gender equality legislation, but on their own, they are insufficient to guarantee it. A growing consensus is that domestic women's movements play a critical role in translating these political opportunities into legislative realities. Analyzing an original data set of social movements and VAW policies spanning 70 countries and four decades, Mala Htun and S. Laurel Weldon (2012) find that the most significant determinant of VAW public policies is the presence of a strong, autonomous women's movement, more so than women's or leftist representation or levels of wealth (see also Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2018). These authors also find that the impact of international norms on VAW policies is conditional on the presence of strong, autonomous domestic women's movements. In a similar vein, examining the adoption of gender equality legislation in postconflict settings, Aili Mari Tripp (Reference Tripp2015) finds that absent mobilization on the part of an autonomous domestic women's movements, international pressure is unlikely to produce gender equality reforms even in the context of peace negotiations and constitutional reforms.

A transnational advocacy network is also unlikely to successfully promoting meaningful gender equality legislation unless it includes a strong domestic women's movement. Domestic movements play a critical role in TANs’ information, symbolic, leverage, and accountability politics, providing alternative sources of information and exposing gaps between official rhetoric and practices (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998). In the area of VAW, domestic women's movements are uniquely capable of providing information and testimonials that might otherwise be difficult to access because of the lack of government data or underreporting. Domestic activists’ information politics also help educate policy makers about the nature and extent of the problem, creating new insider allies (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2012, 553). They additionally help render problems such as VAW “knowable at a distance” (Rottenburg and Merry Reference Rottenburg, Merry, Rottenburg, En, Merry and Mugler2015, 7) among potential international allies, generating external pressure on governments through a boomerang pattern of influence (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998, 12–13).

The literature thus overwhelmingly demonstrates that strong, autonomous domestic women's movements are critical for the passage of gender equality reforms, especially for developing and post-transition contexts. Autonomy entails women mobilizing as women, independent from the state, political parties, or other civil society organizations. Autonomous women's movements, as Htun and Weldon (Reference Htun and Weldon2012) suggest, are better able to generate social knowledge about women's societal position, discuss otherwise taboo topics like VAW, and avoid the de-prioritization of their goals that may happen in other settings.

A movement's strength consists of its (1) mobilization potential, which can be measured by the number and visibility of organizations, cultural productions, protests, policy campaigns, and informal networks; (2) institutionalization, which can be measured by activists’ presence in legislatures, political parties, bureaucracies, and other institutions; and (3) cohesion, which can be measured by the density of intramovement networks, collaborative activities, and shared goals (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2012; Mazur, McBride, and Hoard Reference Mazur, McBride and Hoard2016; Waylen Reference Waylen2007a; Yashar Reference Yashar2005). Strong movements are more able to set the public agenda, engage with international or insider allies without being co-opted, persuade allies to champion their causes, and generate societal pressure on reluctant officials.

Political Practices and Gender Equality Reforms

The focus on political opportunities and domestic movements’ strength and autonomy has contributed significantly to our understanding of when gender equality reforms are likely. But it has at times distracted from the strategic and temporal elements of social mobilization that are frequently at the forefront of more anthropological accounts of social movements. This led Anne Marie Goetz and Rob Jenkins (Reference Goetz and Jenkins2016) to call for greater attention to movements’ political practices—their creative, strategic choices related to issue prioritization and framing, forming and managing alliances, and engaging the state or other powerful institutions over time. This article answers that call.

Political practices are worth centering even though they are difficult to study systematically, given their evolving, creative, and interactional nature. In developing or transitional settings, contextual factors seen as supporting women's mobilization—insider allies, international support, large-scale political transitions—are often double-edged. The fact that the very same factors bring both opportunities and risks for domestic women's movements and gender equality reforms necessitates an exploration of how movements strategically navigate this complex reality. For example, international partnerships and aid may in fact weaken domestic movements by promoting short-term projects over long-term organizing, fragmentation, NGOization, and depoliticization. Therefore, they may actually undermine domestic movements’ strength (particularly their cohesion) as well as their long-term pressure for substantive change (Alvarez Reference Alvarez1999; Berry Reference Berry2018; Friedman Reference Friedman1999; Walsh Reference Walsh2016; Widener Reference Widener2007). Similarly, democratization and new insider allies introduce important openings for advocacy, but the introduction of electoral politics and alliances with insiders may also cause partisan splintering and co-optation of women's movements, damaging movement strength, autonomy, and therefore the likelihood of more radical reforms (Friedman Reference Friedman1998; Luciak Reference Luciak2001; Waylen Reference Waylen1994). Centering political practices thus allows us to investigate how nascent women's movements navigate the complex terrain that accompanies such major political transitions in developing countries as democratization or peace building. Relatedly and critically, a focus on political practices allows for the investigation of not just the mechanisms whereby movements achieve their policy aims, but also the origins of movement strength and autonomy, characteristics we now understand to be central for promoting gender equality reforms.

Political practices are best studied through a long-term, process-based view able to capture the dynamic interplay of movement practices, strength, and autonomy, as well as its political contexts. Such a view is likely to illuminate processes through which movements develop autonomy or strength over time, potentially through the very act of pushing for reform. It may also reveal that favorable contextual factors that would be seen as external to movements in a snapshot view are in fact partly the result of earlier movement strategies (Bowen Reference Bowen2019; Friedman Reference Friedman2009; Goetz and Jenkins Reference Goetz and Jenkins2016; Goodwin and Jasper Reference Goodwin and Jasper1999; Roggeband Reference Roggeband2016; Walsh Reference Walsh2012).

Politics of Patience

A long-term, process-based view reveals that the Guatemalan women's movement was able to successfully build strength and autonomy while navigating and transforming its political environment by adopting political practices that aligned with what Appadurai (Reference Appadurai2002) labels a “politics of patience.” A politics of patience often involves a reliance on persuasive protest tactics more than the disruptive tactics often associated with social movements, adopting pragmatic partnerships with whoever is in power, and acting both “in and against the state” (Goetz and Jenkins Reference Goetz and Jenkins2016, 21; Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2012, 554). In developing and transitioning contexts, a politics of patience often involves pragmatically moving between various levels of governance (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998), the slow development of movement strength and autonomy, and the pursuit and acceptance of cumulative, incremental victories.

In these contexts, cultivating movement strength through a politics of patience often entails a focus on generating horizontal, cross-border networks, movement cohesion, and new knowledge as parts of long-term strategizing. Horizontal networks can be particularly important for sharing knowledge and strategies across borders without introducing the same risks to cohesion and autonomy as vertical networks. Concerted efforts to promote and protect movement cohesion are critical because they make it less likely that activists can be played off each other or co-opted while engaging the state or international actors. The development of movement knowledge often entails generating data about people or issues otherwise rendered marginal or invisible, as can be seen in the Indian context in slum dwellers’ self-censuses (Appadurai Reference Appadurai2002) or indigenous movements’ “counter counting” (Johnston Reference Johnston2012). Movement-generated knowledge increases the likelihood that activists will be seen as experts and asked to directly participate in policy design (Medie Reference Medie2013), and therefore it is important for promoting incremental policy change on which movements can build. Through their strategic engagement in policy design, activists may be able to shift the future political contexts to their advantage by, for example, ensuring that relevant reforms incorporate their understandings of the problem at hand or mandate civil society consultation.

A politics of patience is likely to be particularly effective for nascent movements in transitional/post-transition developing contexts because it allows activists to strengthen the movement, establish and defend their autonomy, and transform their political contexts over time. It is rooted in the potentially iterative nature of mobilization and reform and therefore should draw our attention to the temporal and strategic dimensions of mobilization alongside assessments of movement strength, autonomy, and political contexts at a given time.

RESEARCH METHODS

This article is based on research on women's organizations and gender politics in Guatemala between 2006 and 2019, with the most intensive focus on the passage and effects of the 2008 VAW Law occurring in the summers of 2016–19. I conducted semistructured interviews with 50 activists, members of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), government officials, and academics, interviewing some multiple times, for a total of 72 interviews (Appendix A in the supplementary material online lists the interviewees).Footnote 2 Interviews lasted between 15 minutes and two and a half hours and were recorded, transcribed, and coded thematically. Interview questions and coding centered on (1) personal, organizational, and movement histories; (2) views about the causes, effects, and forms of VAW over time; (3) activists’ strategies, including service provision, protests, lobbying, and information politics; (4) intramovement dynamics, including intramovement issue prioritization, debates, and networks; (5) political contexts including domestic legislation, international accords, and insider and international allies; and (6) the strengths and limitations of VAW reforms. Appendix C describes the thematic codes.

I also undertook archival research at the Centro de Investigaciones Regionales de Mesoamérica and the Asociación para el Avance de las Ciencias Sociales en Guatemala in 2008 and 2016, focusing on the history of women's organizing and VAW policies. I supplemented interviews and archival research with secondary literature and analyses of the feminist newspaper laCuerda (April 1998–May 2008). Drawing on these data, I created a periodization of mobilization and reform, making temporal divisions based on turning points for movement strength, autonomy, and political practices and putting these in the context of broader political changes. These turning points were ones commonly identified by activists themselves in their retelling of their personal histories and movement histories. This periodization is summarized in Appendix B, providing readers who are unfamiliar with Guatemala with a quick reference to accompany the following narrative account.

The bird's-eye views presented in Appendix B show evidence of a strengthening women's movement,Footnote 3 increasing regional and international pressures for gender equality reforms, and incremental policy and legislative advances, as would be expected by the literature. The narrative provided here extends the literature by delving deeper into the emergent processes and the political practices that allowed the Guatemalan women's movement to build its strength, defend its autonomy, and shift its future political landscape to its advantage over time. This narrative also shows that some of the contextual factors that might otherwise be seen as external to the movement were actually influenced by the movement's earlier strategies, illustrating that the borders between movements and their environments are to a degree artificial (Goodwin and Jasper Reference Goodwin and Jasper1999) despite the simplified image provided in Appendix B.

POST-TRANSITION OPPORTUNITIES AND OBSTACLES FOR THE GUATEMALAN'S WOMEN'S MOVEMENT

During the armed conflict in Guatemala between military-led governments and leftist guerrillas (1960–96), state forces had killed or disappeared more than 200,000 Guatemalans, used VAW as a weapon of war, repressed civil society, and therefore blocked women's domestic mobilizing (Berger Reference Berger2006; Comisión de Esclarecimiento Histórico 1999; Walsh Reference Walsh2008). As a result, Guatemala's autonomous women's movement is relatively young compared with its regional counterparts, emerging in the context of political liberalization (mid-1980s) and gaining strength thereafter, especially during the peace negotiations (mid-1990s). In that way, the emergence of the Guatemalan women's movement follows patterns similar to those found in some sub-Saharan African countries transitioning from conflict in the 1990s (Tripp Reference Tripp2015).

Postconflict Guatemala presented stubborn challenges to women's mobilizing. Long-standing legal and social norms encouraged men's domination over women. Women's unequal access to education, employment, and resources presented obstacles to their widespread mobilization. Unlike other postconflict countries, political and economic elites that held power during the armed conflict maintained considerable power even after political liberalization and peace building, reducing the openings for women's political leadership in the post-transition period. Indeed, those who had committed wartime VAW went unpunished, and some were even incorporated into the postconflict governance and security apparatus, contributing to impunity for VAW (Sanford Reference Sanford2008; Trujillo Reference Trujillo, Fregoso and Bejarano2010). An inchoate party system with numerous transitory political parties, a weak political left (Nájera Reference Nájera2009), the dearth of female legislators (Palacios Reference Palacios2019), and the scarcity of sympathetic bureaucrats with any real power (Berger Reference Berger2006) also made it difficult for activists to develop long-term relationships with sympathetic party and government insiders.

Yet, as in other countries experiencing similar transitions, political liberalization and peace building also provided opportunities for the nascent women's movement, as I detail in my discussion of four critical periods for women's post-transition mobilization (see also Appendix B). In the first period, political liberalization and the concomitant increase in international funds (mid-1980s–1994) contributed to the emergence of an autonomous women's movement that developed regional and international networks and prioritized VAW. Yet, as in other developing countries in transition, NGOization, neoliberal subcontracting, and partisan conflicts in Guatemala threatened to divide and depoliticize the nascent movement.

In the second period, the women's movement leveraged peace negotiations (1994–96) to better establish and defend its autonomy, counter divisive pressures, and enhance its strength, reflecting a politics of patience. It also institutionalized some of its goals in ways that would create future political openings.

In the third period, the women's movement drew on its previous partial successes engaging the state, focusing on public policy and legal reform (1996–early 2000s). In the process, it gained experience allying with insiders to achieve incomplete and incremental advances such as an intrafamilial violence law. While unsatisfactory, activists accepted the law as part of their politics of patience and further built on it to cultivate new knowledge and legislate a future role for themselves in VAW reforms.

In the fourth period, the movement mobilized around the issue of femicide/feminicide to push for more comprehensive VAW reforms (early 2000s–2008). In so doing, activists built on previously developed autonomy and strength, as well as openings in their political context to which they had earlier contributed. They generated new knowledge and pragmatically worked with insiders even when they were few and ideologically diverse.

To help readers follow the narrative, each of the following sections is numbered (1–4), to coincide with the numbers/headings that appear in Appendix B, and begins with a paragraph summarizing the key developments in that period.

1. Establishing Movement Autonomy, Regional Connections, and VAW as a Priority (1980s–1994)

The autonomous women's movement in Guatemala took shape during the mid-1980s, when activists took advantage of openings offered by political liberalization to provide services to women, make regional connections, and establish VAW as a priority. Yet, at the same time, the nascent movement confronted divisive pressures introduced by electoral politics, government subcontracting, and competition for international funding. This period demonstrates the opportunities and challenges that nascent movements in developing-country and transitional contexts must navigate strategically while establishing priorities and building movement strength and autonomy.

At the start of political liberalization (mid-1980s), few Guatemalan women were mobilizing as women. The armed conflict had stifled some women's mobilization, driven some into exile, and channeled others into mixed-gender groups focusing on revolution, forced disappearances, or economic insecurity (Carrillo and Chinchilla Reference Carrillo, Chinchilla, Maier and Lebon2010). Without pressure from a strong, autonomous women's movement, the constitutional and legal framework developed during this time largely prioritized family cohesion over women's rights. For example, despite international norms championing women's economic participation, legally, Guatemalan women were barred from seeking employment without their husband's permission until 1998.

Initially, women's mobilization in the context of liberalization centered broadly on human rights and addressing wartime violence rather than women's rights or VAW specifically (England Reference England2014). For example, in 1984, the mixed-gender Mutual Support Group (GAM) was formed mostly by women like Nineth Montenegro to demand information about disappeared relatives (Montenegro, 2017 interview). Soon, though, women began to organize as women to a greater degree and prioritized VAW. Autonomous mobilization was spurred in part by the new regional connections and international funding facilitated by the domestic political opening. Notably, Guatemala-based activists and Guatemalan feminists in exile participated in the Fourth Latin American and Caribbean Feminist Encounter in 1987 in Taxco, Mexico. Some attendees were inspired to found now-influential women's organizations, including the National Coordinating Committee of Guatemalan Widows (Conavigua), the Living Earth Women's Group (Living Earth), and the Guatemalan Women's Group (GGM), all of which were founded in 1988 (Lemus 2016 interview). Returning women refugees, some of whom had been exposed to feminism in exile (Morán, 2017 interview), also founded organizations such as the Mama Maquín Organization of Guatemalan Women (1990), Mother Earth (1993), and Ixmucane Women in Resistance (1993). Other women's organizations, such as the Women's Group for Family Improvement (GRUFEPROMEFAM) began as women's wings of mixed-gender organizations. Local organizations also sprung up across the country to address women's immediate needs through socioeconomic or educational projects, taking advantage of international funding aimed at “gendering” development (Beck Reference Beck2017).

Some organizations founded during this time identified as feminist (Living Earth, GGM) whereas other eschewed this label (Conavigua, GRUFEPROMEFAM). Many focused their political practices around lobbying and service provision (Berger Reference Berger2006, 31–32), responding to international funding and seeing these as the “organizational strategies in times of peace,” compared with more confrontational strategies associated with conflict (Barrios Klee, 2009 interview). Through their experiences of service provision, some organizations, such as GGM, began to appreciate how violence affected every aspect of women's daily life and prioritized VAW, forming an intramovement network, the Network against Violence against Women (Rednovi), to coordinate their efforts in 1991. In 1995, GGM opened one of the first domestic violence shelters in the country. GGM's director, Giovana Lemus, explained that the organization coupled service provision with lobbying for state reform as a strategic focus, based on its experience accompanying VAW victims to unresponsive state offices. Recognizing the double-edged nature of NGO-led, foreign-funded projects—which provided services in the short term but were limited in scope and temporary in nature—GGM activists concluded that they could only promote long-term change by reforming state institutions, because “with this problem, with this scope, we are not going to be able to [deal with it] on our own” (Lemus, 2016 interview).

Facing an unresponsive government domestically, activists drew on horizontal networks with other Latin American activists to generate new knowledge and new institutions related to VAW that they could later leverage to pressure the government—emblematic of the multilevel, pragmatic, and long-term strategizing that makes up a politics of patience. For example, in 1987, activists worked with the newly formed network connecting feminist legal scholars, the Latin American and Caribbean Committee for the Defense of Women (CLADEM), to conduct a regional evaluation of VAW legislation. Finding a legislative vacuum across the region and frustrated with the lack of attention to VAW among international institutions, Latin American activists shifted to the regional level of governance, collaborating to successfully pressure the Organization of American States’ Inter-American Commission on Women (CIM) to take up the issue of VAW, which it did in 1988, relying on the knowledge generated by national and regional networks.

In 1994, CIM issued the first binding regional accord on VAW, the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of VAW (Belém do Pará). This convention established states’ responsibility to adopt and reform legislation to prevent and address VAW. Its hard-law status made it much stronger than the United Nations (UN) General Assembly's Declaration on the Elimination of VAW, adopted the previous year. Activists participated in the process, seeing Belém do Pará as a useful “tool” to force domestic legislation, demonstrating their long-term, pragmatic vision (Lemus 2016 interview). Latin American activists were also active at the international level, contributing to a number of openings that they would later use domestically (Friedman Reference Friedman2003), including the explicit incorporation of the issue of VAW into the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW, 1992); the establishment of a Special Rapporteur on VAW at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and the UN; and the establishment of states’ obligations to adopt policies to eliminate VAW in the Fourth UN World Conference on Women's Platform for Action (1995) (Sagot Reference Sagot, Maier and Lebon2010). Activists’ participation in regional and international organizing demonstrates how they moved strategically between levels of governance to achieve their long-term domestic goals and how they contributed to the very supranational openings that later enhanced their domestic mobilization (Roggeband Reference Roggeband2016).

While liberalization and international and regional attention to VAW presented significant opportunities for women's autonomous organizing, the Guatemalan women's movement also confronted challenges common to post-transition developing countries. By the 1990s, professionalized women's NGOs were becoming the prevailing form of organization in Guatemala, incentivized by neoliberal government subcontracting and international aid in the wake of political liberalization. Debates about autonomy arose, with some organizations engaging the state and others criticizing the choice given ongoing government abuses. Competition over international support sparked disagreements in a movement that was already struggling to bridge class, ethnic, and place-based differences. Other conflicts arose with debates in the new era of electoral politics, such as those between feminists, religious, and indigenous women activists about reproductive rights in the context of the failed Population and Development Law (Solórzano Reference Solórzano2006, 21–22). The resulting divisions meant that “the government and international funding agencies could deal separately with each women's organization and sometimes pit the interests of one against those of another” (Berger Reference Berger2006, 33–34). The government was able to rely on women's organizations to manage some social services while resisting their calls for gender equality reforms.

2. Building Movement Strength and Institutionalizing Movement Goals (1994–96)

The Guatemalan government finally agreed to UN-brokered peace talks in the mid-1990s, a period when gender equality was being pushed by both international institutions and domestic women's organizations. This section describes how the Guatemalan women's movement used the opening offered by the peace negotiations to institutionalize some of its goals in the peace accords and related institutions, shaping the future political context to its advantage. It also managed to strengthen the movement—enhancing its mobilization potential, gaining experience negotiating with a recalcitrant state, and cultivating movement cohesion despite the divisive pressures discussed above. Newfound strength and incremental institutional advances would be key to future victories.

The accords’ negotiation framework called for a Civil Society Assembly, from which groups, organized into sectors, offered recommendations on negotiation topics. Women could participate in mixed-gender sectors but were not initially given their own autonomous space. Conavigua, GGM, Living Earth, GAM, Women's Civic Political Convergence (Convergence), and other women's organizations therefore launched a campaign for their own sector, recognizing the importance of protecting their autonomy. The resulting Women's Sector brought together women from 32 organizations of different classes, places, ethnicities, and political orientations. In the Women's Sector, according to activist Paula Barrios, “women converted themselves into a strong pressure group” and more women prioritized their gender and/or feminist identities (Barrios, 2016 interview). For example, Martha Godinez, a member of a Christian women's organization at the time, explained that prior to her participation she “was a woman but it was like [she] was a stranger in a woman's body”; participating in the Women's Sector made her recognize the damage of Guatemala's patriarchal system (Godinez, 2017 interview).

Organizations in the Women's Sector developed a common platform despite their differences and their relative dearth of previous collaborative experiences, calling for women's political participation; access to housing, land, and credit; and protections for indigenous rights. Through a “multicultural, multiclassed gender analysis based on rights” (Berger Reference Berger2006, 35), they came to understand gendered violence as a weapon used “to demonstrate one's control, not just over land, over life, but also over women's bodies, to degrade communities” (Godinez, 2017 interview) and linked wartime VAW with VAW in the private sphere. Despite women's recommendations to include in the accords a mandate to criminalize VAW, negotiators refused because, as activist Sandra Morán explained, “from their point of view it was a private matter” unrelated to the conflict (Morán, 2017 interview).

Negotiators did, however, incorporate some recommendations, including mandates that the government fulfill its CEDAW obligations, reform legislation to eliminate discrimination against women and criminalize sexual harassment, and create institutions to protect indigenous women's rights. Accords recognizing women's specific rights and needs represented a step forward in achieving broader institutional reform (Berger Reference Berger2006; Carrillo and Chinchilla Reference Carrillo, Chinchilla, Maier and Lebon2010). The development of the Women's Sector was also a turning point in women's organizing. Activists leveraged this institutional space on which they had previously insisted (the Women's Sector) to stake out their autonomy and strengthen the movement, countering the threats to cohesion described earlier.

Activists’ experiences during and after peace negotiations convinced many of the need to engage the state and provided them with experience of achieving incremental advances even in the face of the state's reluctance and attempts to coopt them. Additionally, in a pattern that would later be repeated, incremental successes in the peace accords became a launching pad for future mobilization. For example, after the accords were signed, activists organized grassroots activities around the country to explain them to women, receive feedback on implementation, and formulate a plan for an agency that would help put the accords into action. Meanwhile, the government attempted to wrest control of the institution-building process by charging the National Women's Office, and then later the Secretariat of the Peace, with the design of the implementing agency. Rather than drop out of the process, as the government appears to have hoped, many activists remained engaged, able to weather “the arduous debates and numerous political maneuverings” because of the newfound cohesion they developed in the Women's Sector (Berger Reference Berger, Eckstein and Wickham-Crowley2003, 204).

The anti-feminist stance of the government ensured that the resulting National Women's Forum would have limited authority and be unable to adopt an explicitly feminist stance. Yet through their continued engagement, pragmatic compromises, and the support of a handful of sympathetic insiders, activists ensured that the National Women's Forum would have a participatory element in that it would receive recommendations from elected regional and ethnic delegates. Through the process of delegate elections, women's organizations mobilized six thousand women around the country—encouraging women's political participation and enhancing their own mobilization potential (Berger Reference Berger, Eckstein and Wickham-Crowley2003). The Women's Sector thereafter became a permanent umbrella organization that continued to strategically work with the National Women's Forum to push for the accords’ implementation.

Thus, through their insistence on an autonomous Women's Sector, organizing around the peace accords, and pragmatic engagement in subsequent institution building, the women's movement adopted strategies that strengthened the movement, established its autonomy, and gave it experience negotiating with a reluctant state without sacrificing its newfound strength or autonomy. In the process, it generated new institutional openings that it could leverage in the future.

3. Promoting Incremental Advances and Alliances to address VAW (1996–early 2000s)

During the second half of the 1990s and the early 2000s, the women's movement increasingly channeled its efforts toward public policy reform. This section details how activists took advantage of their strength and autonomy and political openings to push for domestic VAW legislation. Reflecting a pragmatic acceptance of incremental change, characteristic of a politics of patience, many supported the resulting legislation on intrafamilial violence even though it was inadequate. Indeed, they strategically leveraged this incomplete law in ways that further strengthened the movement and institutionalized their influence.

The women's movement's growing strength was evidenced by the establishment of women's organizations, cultural and academic centers, women's state agencies, and the election of two activists, Conavigua's Rosalina Tuyuc and GAM's Nineth Montenegro, to Congress (1996) (see Appendix B). Having established VAW as a priority, activists pressured government officials for relevant legislation through letter writing, press conferences, and marches. They arranged meetings with policy makers and, when denied meetings, stood outside their offices with banners (Walsh Reference Walsh2008). Activists were supported by Congresswoman Montenegro, who headed the Congressional Commission for Women, Adolescence, Childhood and Family, later transformed into the Congressional Women's Commission (1998). They also benefited from the government's ratification of Belém do Pará (1995), which provided them with an opening to lobby for legislation that mirrored the convention's language and scope.

Congresswoman Montenegro faced hurdles to proposing such legislation. In the shadow of the armed conflict, she and her leftist colleagues held just six legislative seats and were seen as radicals. As a result, she explained, “To be able to gain the will of the majority there were things we could not do. Like classify VAW as a crime. So, we had to soften many many things” (Montenegro, 2017 interview). Montenegro responded to her peers' reluctance by focusing proposed legislation on intrafamilial violence. Some women's organizations withdrew, criticizing the dilution of their feminist agenda through what one activist labeled “family-ism” (López de Cáceras, 2017 interview). But other activists pragmatically continued with the process, seeing even an incomplete law as a foundation on which they could build, emblematic of a politics of patience (Lemus, 2016 interview).

The Law to Prevent, Sanction and Eradicate Intrafamilial Violence (Intrafamilial Violence Law) established victims’ rights to restraining orders and police's obligation to intervene in in flagrante abuse. But it de-gendered VAW, failed to criminalize abuse, and lacked enforcement provisions. Yet activists’ pragmatic engagement in the Intrafamilial Violence Law had positive impacts on both the women's movement and its future political context. Activists institutionalized a human rights frame in the law's text and positioned violence in the private sphere as a matter of public concern (Godinez, 2017 interview). Activists also used the law as a launching pad for subsequent mobilization and enhancement of the movement's institutionalization. They vernacularized the law for distribution around the country, used the law as a jumping off point for broader discussions of VAW in workshops and trainings, and assisted women making criminal complaints. They deployed information politics, collecting statistics on intrafamilial violence complaints, and conducted studies on the law's implementation, which they found to be inadequate (Berger Reference Berger2006; Trujillo Reference Trujillo, Fregoso and Bejarano2010). Rednovi members then drew on this self-generated knowledge during the 1999 elections, lobbying leading presidential candidates to create an oversight agency that could address implementation problems. Rednovi activists (many of whom were leftists) secured a commitment from future right-wing president Alfonso Portillo by appealing to his wife's ambitions to participate in such an agency. Portillo later fulfilled his commitment by supporting an amendment to the Intrafamilial Violence Law creating the National Coordinator for the Prevention of Intrafamilial Violence and Violence against Women (CONAPREVI) (Walsh Reference Walsh2008).

CONAPREVI was a civil society–state hybrid oversight and coordinating institution, incorporating representatives from state agencies alongside three Rednovi representatives who would become “practically the engine of CONAPREVI,” according to activist Hilda Morales Trujillo (Trujillo, 2017 interview). Through their participation in CONAPREVI, Rednovi activists promoted the collection of VAW data, contributed to national plans for the prevention and eradication of VAW, and attracted international attention and funding to the issue of VAW, even though the agency continually faced political and budgetary battles (Walsh Reference Walsh2008). Thus, activists leveraged the incremental victory of the Intrafamilial Violence Law to legislate themselves a permanent entry point into the state and a source of information, allies, and pressure. The creation of CONAPREVI demonstrates that even in the face of little political will, women's movements can create institutional allies and openings where few previously existed by adopting a politics of patience, one that accepts and builds on partial victories and pragmatic partnerships.

By the early 2000s, law had become “a site of contestation between the state and women in attempts by each to redefine citizenship and gender” (Berger Reference Berger2006, 15). Activists failed in their efforts to criminalize sexual harassment (1999) but successfully pushed for the Law for the Dignification and Integral Promotion of Women (1999) and the criminalization of discrimination (2002), among other reforms (see Appendix B). In their efforts, women's organizations collaborated with the Congressional Women's Commission, which hosted them in regular roundtables on legislative proposals since 1998. The women's movement also began in 2003 to strategically approach the leading presidential candidates with a joint list of proposals for political parties’ platforms, regardless of party ideology, demonstrating its willingness to work with insiders regardless of ideological orientation. The women's movement would later build on these experiences advocating for the Intrafamilial Violence Law, CONAPREVI, and other reforms to push for more comprehensive VAW legislation.

4. Building on Prior Activism, Focusing on Femicide/Feminicide (early 2000s–2007)

By the early 2000s, activists had developed relationships with a handful of government insiders, gained experience navigating officials’ reluctance to pass gender equality legislation, and promoted incremental institutional advances which strengthened the movement and shifted the political context to facilitate future reform. They had also legislated themselves an insider's seat to developing VAW policies through CONAPREVI. This section details how, starting in the early 2000s, activists built on these advances and focused on the alarming rates of women's homicides in their calls for more comprehensive VAW legislation. In the process, they leveraged activist-generated knowledge, a mix of disruptive and persuasive protest tactics, and alliances and institutional openings generated by their earlier politics of patience.

Between 2000 and 2006, the female population increased 8%, whereas the female homicide rate increased more than 117% (Sanford Reference Sanford2008, 108). Women's violent deaths represented the most extreme of many forms of VAW that were widespread but hidden because of underreporting and the tendency to see VAW as private. In this context, activists’ focus on women's murders was useful because they represented “a quantifiable index of the endpoint of many other forms of violence that [were] less easy to document statistically” (England Reference England2014, 125).

Guatemalan activists saw the government's failure to document sex-disaggregated homicide statistics as facilitating impunity (Prieto-Carrón, Thomson, and Macdonald Reference Prieto-Carrón, Thomson and Macdonald2007). Rednovi, GGM, and regional bodies such as CLADEM therefore pressured the government to collect more useful data, undertook what Lemus called “social audits of the state” (Lemus, 2016 interview), and generated new knowledge about women's homicides. They found that police reports often misclassified women's homicides as accidental manslaughter and officials failed to investigate or track details that would have revealed killers’ misogynistic motives, such as evidence of sexual violence or bodily torture (CLADEM 2007). Rednovi and GGM therefore combined government-generated data with newspaper reports to establish more reliable counts and conduct gender analyses of women's violent deaths (Lemus, 2016 interview; Morán, 2017 interview). They highlighted the frequent use of sexual violence, “the targeted mutilation of parts of woman's body that symbolize her femininity, such as her reproductive organs, breasts, and face” (Godoy-Paiz Reference Godoy-Paiz2012, 91), and the gruesome ways that their bodies were disposed of as evidence of the murderers’ misogynistic motives (Prieto-Carrón, Thomson, and Macdonald Reference Prieto-Carrón, Thomson and Macdonald2007).

Movement-generated data on murdered women positioned activists as experts while rendering marginalized victims visible to government and international authorities, in a manner similar to the Indian slum dwellers’ self-censuses described by Appadurai (Reference Appadurai2002). These data were also critical for framing women's murders as being motivated by misogyny and thus constituting femicide or feminicide. Some, such as Convergence's Carmen López de Cáceras, used the term “feminicide” to implicate the state in women's homicides (López de Cáceras, 2017 interview). Others, such as Martha Godinez, suggested that activists’ terminology was influenced by their connections to either Mexican feminist Marcela Lagarde (who coined the term “feminicide”) or Costa Rican feminists Montserrat Sagot and Ana Carcedo Cabañas (who used “femicide”) (Godinez, 2017 interview).

Starting in 2002, the feminist newspaper laCuerda published a “violence report” section with information on recently murdered women or statistics from governmental, nongovernmental or international agencies. The newspaper first used the term “femicide” in July 2003, in an article on Rednovi's participation in the regional awareness-raising campaign, “For the life of women, not one more death” (laCuerda 2003). Subsequently, 62% of laCuerda issues leading up to the passage of the 2008 VAW Law contained explicit mentions of femicide or feminicide, demonstrating the topic's centrality in feminist circles. Femicide/feminicide and VAW were additionally discussed in the women's radio and television shows established during this period (Monzón Reference Monzón2015, 21) (see Appendix B). Enumeration and analyses of women's violent deaths, covered in NGO and regional reports and cultural outlets, were central in activists’ battles for representational hegemony at home and abroad, establishing women's deaths as femicide/feminicide rather than generalized crime. Statistics allowed for international comparison and rankings—a woman killed every 12 hours, 97% of murders in impunity, the third-highest rate of murdered women globally—rendering femicide/feminicide visible to potential international allies.

In Congress, activists drew on connections forged during the push for the Intrafamilial Violence Law and other legislation, most notably with the Congressional Women's Commission (headed by Montenegro) and the Congressional Human Rights Commission (headed by Congresswoman Myrna Ponce, also a member of the Women's Commission). Women's organizations used their connections with these commissions to hang posters in Congress with femicide/feminicide statistics and to encourage official recognition of their efforts to help VAW victims. For example, Norma Cruz, a leftist and the head of an NGO supporting VAW victims, the Survivors Foundation, partnered with right-wing congresswomen Myrna Ponce and Zury Ríos to request budgetary allocations to fund their legal and psychological support for victims. They garnered $250,000 using unconventional tactics to convince indifferent right-wing and left-wing congressmen alike. Each morning Ponce displayed photographs of femicide/feminicide victims’ corpses and emphasized that these victims could be congressmen's daughters.

In 2004, the Women's Commission was tasked with investigating the government's failure to prevent, investigate and eradicate femicide/feminicide. Seeing them as having the relevant expertise, the commission invited activists to participate in its discussions with various governmental representatives. Soon after (in 2005–06), commission members participated alongside activist Hilda Morales Trujillo in a series of interparliamentary meetings on femicidal violence alongside Spanish and Mexican congressional representatives. Participants discussed their efforts to classify femicide/feminicide as a crime and combat VAW in their countries. At the time, Spain had recently passed a VAW law and created specialized VAW courts. According to Congresswoman Ponce, this sparked the idea of creating specialized VAW courts in Guatemala, as would be mandated by the 2008 VAW Law (Ponce, 2017 interview).Footnote 4

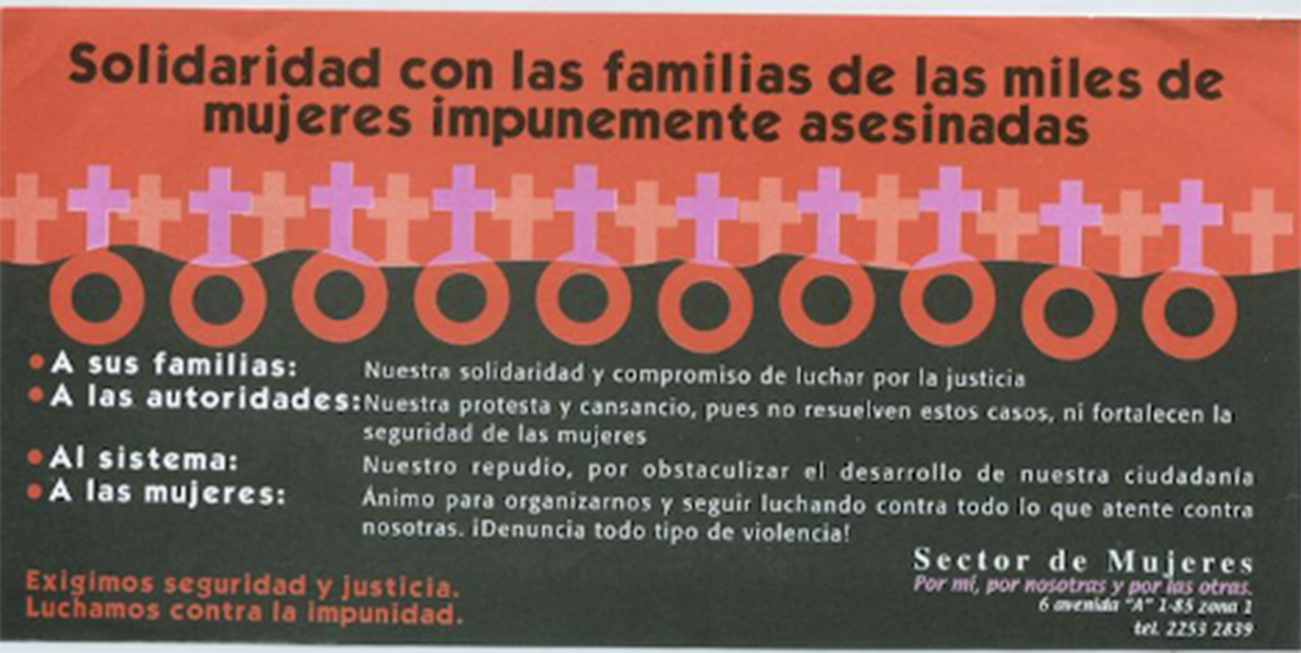

Yet the Women's Commission found its influence limited by the small number of congresswomen (14 of 158) and the lack of respect their peers gave them (Ruhl 2006, 23). Congressmen were in fact following the lead of the president at the time, Oscar Berger, who downplayed femicide/feminicide publicly, stating that most victims had gang connections. Activists thus coupled persuasive with disruptive protest tactics. They distributed pamphlets (Figure 1) and led marches in the capital, causing traffic jams and painting buildings with feminist slogans.

Figure 1. Women's Sector flyer expressing solidarity with murdered women's families and protesting authorities for leaving cases unresolved.

Activists also faced backlash. For example, the Women's Sector's offices were broken into on multiple occasions. Perpetrators searched the organization's files, poured blood on the floor, and left a shard of bloody glass on Sandra Morán's desk. Women's Sector activists responded by holding street demonstrations in the capital featuring poetry, music, speeches, and several hundred supporters (Jeffries Reference Jeffries2007).

Activists additionally used previously created strategic entry points to solicit and amplify international pressure. In their official capacity, Rednovi representatives in CONAPREVI invited international observers to the country, such as the UN Special Rapporteur on VAW (2004). The rapporteur's statements, as well as those from the UN Development Programme (2007), the CEDAW committee (2005), Amnesty International (2005), the IACHR (2007), the U.S. House and Senate (2007–08), and the European Parliament (2007), criticized the Guatemalan government's lackluster response to VAW.

By this time, mainstream newspapers had started to pay more attention to VAW and femicide/feminicide (Valverde Reference Valverde2013). They reported on women's public actions, international reports and statements related to femicide/feminicide, and, less often, the unresponsiveness of state institutions to women's complaints of VAW. For example, a December 26, 2007, Prensa Libre editorial lamented that “[i]n the case of murdered women's family members, you should hear how the public prosecutor tells them that surely what happened was because their daughter was a gang member, a prostitute or was up to no good, and that she has to be practically virginal for them to take her case seriously” (quoted in Valverde Reference Valverde2013, 152–53). In some cases, news reports of women's homicides contextualized the violence using newly available statistics. For example, a May 17, 2007, Prensa Libre article reporting the shooting death of an 18-year-old woman ended, “since January, 201 women have died violent deaths” (quoted in Valverde Reference Valverde2013, 147). International media outlets also began to cover femicide/feminicide in Guatemala, especially following the 2006 release of Giselle Portenier's documentary Killer's Paradise, which showed in graphic detail the alarming rates of women's murders and public officials’ indifference.

In response to pressure from congresswomen and other government insiders, civil society, international organizations, and media, the Guatemalan government created the National Commission to Address Femicide (2006), composed of congresspeople from different political parties and representatives from various government agencies. The commission issued recommendations in line with those of the UN Special Rapporteur, finding that the rising murders of women consisted of femicide, and that research and reforms were needed to improve women's access to justice and address VAW (Godoy-Paiz Reference Godoy-Paiz2012).

Three different proposals for new VAW legislation were drafted in 2006–07, largely originating from congresswomen participating in the Women's and Human Rights Commissions. Congresswoman Montenegro emphasized that women's organizations, especially GGM, were “fundamental” to these legislative proposals, because “initially the congresswomen who formed the Women's Commission lacked knowledge about [relevant] international conventions” and had to be educated by activists (Montenegro, 2017 interview). Activists pragmatically partnered with congresswomen (who held just 9% of congressional seats) even if they had other ideological differences. At the time, 10 of the 14 congresswomen belonged to right-wing parties, whereas most activists held leftist views.

The first legislative proposal (Initiative 3503) was initiated by Sandra Torres and the female members of her centrist party (National Unity of Hope), who “opened the door more” to women's organizations working on such initiatives, according to activist Carmen López de Cáceras (López de Cáceras, 2017 interview). Torres, a successful maquila owner without prior connections to the women's movement, was one of the party leaders at the time, having previously founded the party's women's wing. As noted later, after her husband won the 2007 presidential elections, she supported the 2008 VAW Law from her position as first lady. The second proposal (Initiative 3612) was put forth by Congresswoman Ponce and her right-wing colleagues. The third (Initiative 3718) was proposed by two leftist members of the Women's Commission, Congresswomen Nineth Montenegro and Alba Estela Maldonado Guevara.

Faced with these different proposals, congresswomen and activists decided to compromise on one shared piece of legislation. As Congresswoman Ponce explained, “we started separately, but the way we moved forward, was we created a grand alliance, that is what you call it. The power of women…I think we understood that only united could we pass the law” (Ponce, 2017 interview). Women's organizations, representatives of international organizations such as the UN Population Fund, and CONAPREVI participated in the process. Yet resistance on the part of congressmen meant that the legislative session ended in December 2007 without a vote on the unified VAW proposal.

“WOMEN WERE IN CHARGE”: PASSING THE 2008 VAW LAW

In the 2008–12 legislative session, just 19 of the 158 congresspeople were women, representing six different political parties from across the political spectrum. As Congresswoman Delia Back and activist Carmen López Cáceras note, activists and congresswomen quickly built on the existing momentum to seize on the ephemeral “honeymoon” period of the new legislative session in which they could convince congresswomen to cross party lines to support VAW legislation before partisan rancor, congressional infighting, or campaigning for the next election took over (Back, 2017 interview; López de Cáceras, 2017 interview).

A fourth legislative initiative (Initiative 3770) was proposed by a group of right-wing, centrist, and left-wing congresspeople and sent to the Women's Commission for review. Given their perceived expertise, activists’ suggestions were given significant weight in the Women's Commission's favorable opinion on the proposal and its recommendations for revision. Among other recommendations, for example, the commission suggested mandating that the government provide funding to NGOs assisting VAW victims. The revised law's sponsors secured support from all 19 congresswomen, some of whom had extreme ideological differences. As an example of the pragmatic partnerships that a politics of patience might entail, two of the most prominent congresswomen involved in campaigning for the law were Nineth Montenegro, whose husband was disappeared during the armed conflict, and Zury Ríos, the daughter of the ex-dictator Ríos Montt, who had overseen such disappearances. As Delia Back, one of the bill's sponsors and then president of the Women's Commission, explained, “there were not party flags or personal issues. Rather, the objective was to pass the law” (Back, 2017 interview). Congresswoman Back and activist Dora Amalia Taracena San Juan highlighted that in addition to congresswomen and activists, the lobby benefited from the support of women in the judiciary, the public defender's office, the Human Rights Ombudsman, and the new first lady, Sandra Torres, among others (Back, 2017 interview; Taracena San Juan, 2017 interview), demonstrating the power of strategically placed sympathetic insiders even when they are few (Waylen Reference Waylen2007b).

Congressmen were reluctant to speak out publicly against the bill given the national and international pressure. Indeed, most articles and opinion pieces published in mainstream newspapers were supportive of the legislation and critical of congressmen who expressed doubts (see Monzón Reference Monzón2008; Vásquez Reference Vásquez2008). Yet behind the scenes, some congressmen resisted. The proposed law included the criminalization of sexual harassment to fulfill the peace accord mandates that were recommended by the Women's Sector a decade prior. Yet congressmen resisted so strongly that sexual harassment was stripped from the proposal before it reached the Congressional floor. Congresswoman Montenegro recalled, “It was something so abusive, so indignant for us women…the congressmen said ‘these women are those who ask for a sexual harassment law, you women are unharassable’” (Montenegro, 2017 interview). Despite the removal of sexual harassment from the proposal, Congressmen accused their female colleagues of being radical feminists and lesbians (insults in their view) and threatened to leave the congressional floor to prevent a quorum sufficient for a vote (Montenegro, 2017 interview). Thus, on the day of the vote, congresswomen stood in the congressional entryway so that congressmen would be forced to register their vote. Congresswomen from different political parties sat together as one block, according to Montenegro, as a symbol “that we [were] united regardless of our ideologies or parties” (Montenegro, 2017 interview). Activists placed candles, funeral crowns, and women's shoes in the entryway and gathered in the congressional gallery to honor femicide/feminicide victims and, as Congresswoman Back recalled, “they applauded us, they encouraged us, and when the law was approved, they threw down rose petals” (Back, 2017 interview).

Ultimately, all congresspeople present (119 of 158) voted in favor of the legislation. Montenegro explained that even congressmen who had resisted the law voted for it because they felt “they are going to see me as behind the times, or underdeveloped, so I am going to have to give in,” even though they did so “very reluctantly” (Montenegro, 2017 interview). Congresswoman Back echoed this sentiment:

[Women's groups] had the topic in the media, on the radio, on the television, in all of the print outlets, they arranged marches, they were speaking out, they came to Congress and all of that…they put the photographs in the paper of those who were against them. ‘These congressmen are against women…’ [A]t the time women were in charge…so all of civil society had their eyes on [congressmen] and they could not say no. (Back, 2017 interview)

Congresswoman Montenegro and Convergence activist Carmen López de Cáceras both highlighted the strength, knowledge, and strategies of the women's movement to explain the differences between the Intrafamilial Violence Law and the 2008 VAW Law, arguing that legislation progressed “with the very growth of the feminist movement in the country” (López de Cáceras, 2017 interview).

Even though it did not include sexual harassment, the 2008 VAW Law was still one of the region's most comprehensive pieces of VAW legislation and one of the first to establish femicide as a unique crime. Respondents highlighted the importance of governmental and international allies and openings but emphasized that women's organizations were largely “the mothers of this law,” as explained by VAW court judge Claudia González (González, 2016 interview). Lawyers and judges highlighted that the law reflected the language and understandings of feminist theory and politics, as evidenced by its glossary of feminist terms, such as “public/private spheres,” and its depiction of VAW in the preamble as rooted in “unequal power relations between women and men, in social, economic, judicial, political, cultural and familial realms.” Recognizing the power of statistics and insider access in their prior activism and policy work, feminists and policymakers also ensured that the law mandated the government to collect and publish VAW data (Article 20), train government functionaries in coordination with women's organizations (Article 18), and support nongovernmental organizations working with victims to ensure the sustainability of their work (Article 17). It also charged CONAPREVI with oversight of the development of abuse shelters (Article 16). While the 2008 law appeared from the outside to be the result of a few years of intense international and domestic pressure, a process-based view demonstrates that it in fact reflected a long-term iterative process in which the women's movement strategically built up its strength and autonomy while shifting its political context to its advantage over decades.

As with the Intrafamilial Violence Law, the passage of the 2008 VAW Law inspired new mobilization and knowledge generation among women's organizations—demonstrating how a politics of patience relies on an iterative process of mobilization and reform. Activists and congresswomen toured the country, convening women's groups to explain the law. Women's organizations, seen as experts, were asked by international and government institutions to help design manuals for implementation and models for holistic attention for relevant state and state-supported institutions. Women's organizations such as Rednovi, GGM, Convergence, the Survivors Foundation, and Living Earth played an oversight role through their participation in CONAPREVI, citizen oversight commissions, and self-directed audits of the law's implementation. GGM was contracted to manage state-funded shelters. Thus, as they did with the Intrafamilial Violence Law, activists institutionalized their understandings of VAW, encouraged data collection that would be useful for future mobilization, and legislated themselves important implementation and oversight roles.

CONCLUSIONS

Political liberalization, peacebuilding, and international support represent important openings for gender equality reforms, but on their own, they are insufficient to ensure the institutionalization of women's rights, much less the enforcement of those rights thereafter. During periods of such political transition, the literature suggests that the best hope for the passage and implementation of gender equality reforms is growing a women's movement that is both strong and autonomous from the dominant political interests. My analysis confirms this finding. As the Guatemalan women's movement grew stronger and more autonomous, it was more successful in pushing reforms and in achieving more comprehensive reforms.

But strong, autonomous women's movements do not emerge automatically from periods of transition. In some contexts, resistance to authoritarianism or violent internal conflicts gave rise to autonomous women's movements, as can be seen in women's peace movements in Liberia or women's pro-democracy movements in Chile. In other contexts, women only began to mobilize as women in response to openings like political liberalization or peacebuilding, as was the case in Guatemala. In still other contexts, a significant autonomous women's movement failed to emerge altogether even in the face of large-scale conflict and political transition, as was the case in places such as Angola, Chad, and Eritrea (Tripp Reference Tripp2015). Thus, identifying the importance of strong, autonomous movements for gender equality reforms leads us to the analytically prior question—how do movements seeking reform develop and defend their strength and autonomy? This is a particularly critical question where women's movements are relatively young, weak, or facing resources or alliances that are at once opportunities and potential risks for movement strength and autonomy, such as international funding or partisan alliances—often the case in transitional and post-transition developing countries.

Answering this question, I argue, requires that we attend to the temporal and strategic dimensions of mobilization. This means paying close attention to how movements’ political practices over time work not just to promote institutional reforms, but also to affect levels of movement strength and autonomy. I have done so here by rooting my analysis in a long-term periodization of the Guatemalan women's movement that put shifts in movement strength, autonomy, and political practices in the context of broader political changes. Social movement scholars would benefit from applying a similar approach—through similarly structured periodization or in-depth process tracing—to other contexts, particularly developing-country and transitional contexts in which movements are relatively young. Doing so allows them to investigate the nature of social movement longevity (is the movement getting stronger or weaker? Is it picking up momentum or has it plateaued?), the learning that takes place over time through the course of mobilization, and the ways that mobilization and reform mutually affect each other over time. It allows researchers to identify the origins and evolution of movement strength and autonomy and highlights that the seeds of political openings observed in time1 may have been planted in time0 by savvy activists with a long-term view in mind—thus blurring the analytical border between movements and their contexts.

Applied to Guatemala, a process-based view showed that a nascent women's movement, without a long history of strength and autonomous mobilizing, leveraged a politics of patience to its benefit. A politics of patience necessarily incorporates a long time horizon because it involves “slow learning and cumulative change” in contrast to “the temporal logics of the project” (Appadurai Reference Appadurai2002, 30). It comprises strategies such as pragmatically working with whoever is in power, accepting partial victories, and “accommodation, negotiation, and long-term pressure rather than confrontation or threats of political reprisal” (Appadurai Reference Appadurai2002, 29). Through a politics of patience, the Guatemalan women's movement was able to build up autonomy and strength over time, through the very process of pushing for the incremental advances on which they could later build.

Early activists pushed for the creation of the Women's Sector and the inclusion of women's interests in the peace accords while mobilizing regionally and internationally for VAW conventions. They later leveraged their enhanced strength and autonomy and these new institutional openings to push for the Intrafamilial Violence Law. While it was weaker than the VAW legislation that they desired, activists used it to strengthen later mobilization and knowledge creation, and to create an institutional opening (CONAPREVI) through which they could access the state and cultivate more allies. Thereafter they used their increased access, governmental and international allies, and capacity for mobilization and information politics to push for the more comprehensive 2008 VAW Law in the face of femicide/feminicide. As with the Intrafamilial Violence Law, women's organizations were able to institutionalize some of their understandings and goals into the 2008 VAW Law, providing future points of access and influence and future bases for mobilization.

The Guatemalan case study provides tentative lessons for activists who want progressive change but who are a part of relatively new and/or weak movements unable to generate widespread societal support or pressure political authorities. A politics of patience is particularly useful for these movements because at its core it incorporates strategies aimed at incremental reforms that will facilitate future mobilization as well as building movement strength and autonomy. That is, in a politics of patience, strengthening the movement and protecting its autonomy are critical goals in and of themselves. In practice, this may mean initially prioritizing issues and strategies around which there is the most consensus to increase movement cohesion and mobilization potential. In developing-country contexts, it implies recognizing the risks and vagaries of international aid, and simultaneously cultivating intramovement and cross-border horizontal connections that are likely to be more enduring and less risky to movement strength and autonomy. It may mean using movement-generated knowledge and persuasive protest tactics to position activists as experts in their own struggle and to create insider allies who are willing to support incremental reforms.

Of course, the passage of VAW legislation alone is not enough to guarantee women's rights to live a life free of violence. In Guatemala, as elsewhere, there are significant gaps among VAW legislation, implementation, and effects (Beck Reference Beck2021). The Guatemalan government has systematically underresourced implementing institutions and underreformed other institutions like police that are often victims’ first points of contact. There have been various (mostly unsuccessful) attempts to weaken the 2008 VAW Law and recent administrations have attempted to restrict the activities of well-known women's organizations, demonstrating that progress is neither guaranteed nor linear, and that it often generates backlash. Additionally, advances in the area of VAW have not brought concomitant successes in other gender equality reforms (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2010) such as sexual harassment legislation, expansion of abortion rights, or the adoption of gender quotas. Yet this article suggests that VAW reforms may have impacts even when are challenged, inadequately implemented, or unable to inspire reforms in other areas because they may strengthen movements and shape future political contexts to activists’ advantage.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X21000349