Introduction

An increasing number of scholars of the Atlantic world have started to reassess the meaning and importance of contraband trade in Caribbean history. Through this work, it has been argued that smuggling was nearly ubiquitous and economically significant in the region. Furthermore, it was understood by its practitioners not as a criminal activity but as a necessary adaptation of unrealistic commercial restrictions imposed by metropolitan governments. These findings are also connected with a changing understanding of the legal and geographic boundaries of what could be called the Greater Caribbean or the circum-Caribbean world. In this context, the marginal and fragmented ventures of Swedish colonialism in the Caribbean have not figured as a phenomenon of particular political or economic consequence. One such venture was the Swedish acquisition and ownership of St. Barthélemy from 1784 to 1878. This article will attempt to show that St. Barthélemy facilitated a type of continuity in the Caribbean contraband trade and was economically significant, even given its relatively short-lived operation.Footnote 1

Early forays into the diminutive island's (20 sq. km) Swedish period have strictly viewed it in terms of national history. As such, they have neglected the island's larger role in a regional and comparative perspective. Consequently, St. Barthélemy's history has been understudied in Swedish historiography on the one hand, and neglected in the mercantile history of the Atlantic world on the other. An increasing interest in the study of small colonial possessions and the minor imperial powers of Northern Europe has only begun quite recently.Footnote 2 The rapid early development and ultimate success of the colony was inextricably linked to the regional trade between the Caribbean and the Americas. In this article, I will discuss the island's function as a free port during the time of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, a role which I argue was similar to the better-known case of Dutch St. Eustatius (nicknamed “the Golden Rock” or “Statia”). The once bustling activity of St. Eustatius, as well as Dutch Curaçao, came to an end when the Dutch Republic was subsumed by France in 1795. Danish St. Thomas, another free port in the hands of a peripheral Northern power, was occupied by British forces in 1807 as a result of the Danish course in the Napoleonic Wars. The effects of these circumstances for the regional trade in the Caribbean have not been well understood in current historical research. These events were however tantamount to a major turn in fortunes for the Swedish colony and its actors. On location in St. Barthélemy during the height of the Napoleonic Wars, colonial officials even ventured to claim that “gold flowed out in streams out of the very rock of the island,”Footnote 3 an allusion to the hundreds of ships which could be seen frequenting the colony to trade and barter their cargoes on a daily basis. What follows is an overview of the changing fortunes of the Swedish entrepôt during the turn of the nineteenth century, aided by access to the old administrative archive of St. Barthélemy, which has been closed to the public since its transportation to France.Footnote 4

Free Ports in the Caribbean and Swedish Colonial Ambitions

From the outset of European colonisation in the Caribbean and the Americas, numerous commercial communication networks spread across the region, spanning imperial and national boundaries. Mutual economic needs created formal and informal bonds between colonies that defied the protectionist regulations of European powers.

The imposition of the English Navigation Acts, a process that started in 1651, was aimed to counteract Dutch, French, and other foreign commercial influence in the English colonies and to ensure the exclusive trading rights of the mother country with its colonies. Other European powers followed suit during the course of the seventeenth century, adopting restrictive shipping laws for their own territories. Such mercantilistic doctrines were regularly defied and circumvented, and the conflicts of the eighteenth century served to strengthen this tendency. Smuggling and contraband trade were especially lucrative during times of war. As a result, certain harbour towns were declared neutral ports to facilitate shipping between traders of all nationalities. These included the small islands of Dutch St. Eustatius, Danish St. Thomas, and Swedish St. Barthélemy in the Lesser Antilles. These were but a few out of a constellation of small trading posts and marketplaces that existed from time to time within the Caribbean region. Other notable examples were Dutch Curaçao and English Port Royal in Jamaica, both of which thrived on the contraband trade with the Spanish American empire from the middle of the seventeenth century.Footnote 5

The Swedish acquisition of St Barthélemy itself had been the result of diplomatic negotiations with France during and after the American War of Independence, and would yield the only tangible accomplishment of Swedish colonial ambitions in the Caribbean.Footnote 6 In addition to a treaty that stipulated French subsidies to the Swedish crown, the French ceded the small Caribbean island in exchange for staple rights in Gothenburg in 1784.Footnote 7

The first Swedish survey expedition to the island carried with it two merchants, Jacob E. Röhl and A. F. Hansen. Upon returning to Sweden from the new colony in late 1785, Röhl penned a sobering report on the limited utility of the island. According to him, the only way forward was through freedom of trade with neighbouring colonies, especially the sugar-producing French colonies of Guadeloupe and Martinique. This would either have to be accomplished by formal trade rights or smuggling. It is interesting to note that he had discussed the latter subject with merchants on St. Eustatius. In his report, he detailed their methods of clandestine trade. A crucial element in the Dutchmen's strategy was “to procure so-called indulgence for their swindles in the French Islands.” He also added that “they must pay for it without exception.” Röhl commented on a broad range of other topics from military to civil administration. One of the important notes was that he viewed the Dutch system of settler inclusion in the ruling colonial councils as a way of ensuring a “popular government.”Footnote 8

Röhl's document is important since it is striking in its likeness to the decrees issued on 31 October 1786, the first of which established the Swedish West India Company (SWIC) and the second of which set forth a first set of administrative rules for the colony. The company was created as a joint stock venture with a limited charter, awarded the right to trade with St. Barthélemy, other West Indian islands, and North America for an initial period of fifteen years. Its privileged position in the form of lower duties and a share of colonial taxes did not, however, give the company exclusive trading rights. Any Swede or foreigner was allowed to carry on trade with St. Barthélemy, although with certain limitations. In accordance with Röhl's suggestions, the company was also granted rights to engage in the slave trade. The regulations for the colony council, regarding matters of administration and law, follows Röhl's document almost point-by-point, with only minor differences.Footnote 9

By the time Röhl had produced his report, the decision to establish St. Barthélemy as a free port had already been made. It was announced in a proclamation by the first governor, Salomon Mauritz von Rayalin, in 1785, later confirmed by royal decree in Stockholm on 7 July 1785. The free-port model practiced by the Dutch and Danes was well known, and was seen as the only realistic alternative when the future of the colony was debated in government. With the acquisition of St. Barthélemy, Sweden also acquired the status of a slaving power, albeit on a limited scale. In principle, the colony was Swedish territory and in all respects under the rule of Swedish law, which did not recognise serfdom or slavery. At the same time, the emerging legal structure of the fledgling colony came to incorporate a mixed legal system where previous French laws and West Indian customs were in effect, much in the same way as they were in Dutch and Danish colonies. In other words, Swedish administration of the newly acquired colony was quite firmly anchored in local and regional conditions, the Dutch example of St. Eustatius having been one of the subjects of consideration.Footnote 10

St. Barthélemy and the French Revolutionary Wars

In the free ports, foreign settlers were of the utmost importance. A scheme of homeland colonisation was not even taken under serious consideration in the case of St. Barthélemy. At the time of transition from French to Swedish governance, a local population of seven hundred French farmers and their slaves were already cultivating most of the poor island soil for household needs. Local cotton cultivation produced some quantities for regional exports, but yearly harvests did not amount to anything that would inspire official measures for its encouragement. Measures which were aimed at attracting merchants and capital from the surrounding islands were instead adopted by the Swedish government. The town of Gustavia was placed around the shores of a protected cove, La Carénage, on the southwest side of the island. In order to become a naturalised Swedish subject, settlers performed a single cash payment and signed an oath of fidelity and allegiance to the Swedish crown. Burger rights were however subject to a differential scale of payment. Merchants wishing to be able to sail their vessels under Swedish colours payed a premium of one hundred Spanish dollars. Artisans and tradesmen planning to open up retail shops or other businesses within town limits were required to pay sixteen Spanish dollars. Merely the right to residence in Gustavia and access to Swedish citizenship came at the trifling price of one dollar. These scales were a clear reflection of both the ambition to attract merchants who carried substantial capital and to provide easy access for much needed mariners and craftsmen.Footnote 11

As there were few formal obstacles to naturalisation, the free-port colonies were neutral havens where refugees could find accommodation, whether they ran from debt, conflict, persecution, or other calamities. Indeed, in the first years of the Swedish colony there was a regulation in effect that granted protection to indebted persons for up to ten years. Minimal taxation and customs fees were put in place so as to provide as much incentive as possible to settle in the colony. While Swedish governance brought with it the establishment of a Lutheran church and congregation, freedom of religion was granted for the colony's Catholic inhabitants and future immigrants of every denomination.Footnote 12 The nature of turmoil in the region, especially from the 1790s onwards, resulted in extensive and complex migration flows, as Caribbean colonies were both engulfed in internal conflicts and subject to external aggression.

After the news of the French Revolution reached the Caribbean in 1789, Frenchmen of various political convictions took refuge on neutral islands, among them St. Barthélemy. This occurred in waves both after the initial revolution in 1789 and during the subsequent Haitian revolution, the British occupations of neighbouring French islands, and after Guadeloupe was reclaimed from the British by Victor Hugues in 1794. According to Anne Pérotin-Dumon, a first great wave of emigration took place in 1793–94 by a heterogeneous group of inhabitants from both Martinique and Guadeloupe, composed of both revolutionary sympathizers and royalists. In May of 1793, Swedish Governor Bagge commented on the arrival of French families with mixed sentiments. On the one hand, he lamented granting protection to foreign “adventurers” and bankrupt persons, which he saw as a potential threat to public tranquillity. On the other hand, he welcomed those “familiar traders” from the French islands who brought with them “considerable property, consisting of slaves, households, cash etc.”Footnote 13

These new inhabitants included French caboteurs who were principally natives of nearby Guadeloupe. Caboteurs such as these tried their hand at both smuggling and privateering during the second half of the eighteenth century. They relied on the extensive port networks between the southern North American colonies and the Spanish American mainland. Gustavia on St Barthélemy, like its forebears in the Danish and Dutch colonies, had become an integral part of this complicated system by the end of the century. The commercial and political relations with the surrounding French colonies were of utmost importance to the Swedish colony. These relations would in time assume more complicated forms, both beneficial and precarious. As soon as war broke out in 1793 many French coasting craft were fitted out as corsairs in Martinique and Guadeloupe. When the British conquered Martinique in 1794, Guadeloupe became the only French colony left in the eastern Caribbean. As a result, the “buccaneering war” of the French revolutionary authorities was organised largely in the port cities of Guadeloupe. Corsairing ships were to be manned by an increasing number of corsaires particuliers, owned and commanded by local caboteurs, since naval forces sent from France, corsaires de la République, had decreased rapidly since 1794.

To support their privateering ventures, revolutionary authorities set up agences de prises, or bounty courts. These were commonly established on neutral or allied islands to oversee the sale of privateering prizes and to repair, equip, and supply their corsairs.Footnote 14 Such an agency was also set up in Gustavia under the guidance of a French consul named Balthazar Bigard. The presence of the bounty court was beneficial for locally settled merchants, insofar as cheap cargoes and ships were to be had when French corsairs brought them into Gustavia. They served as an outlet for seized colonial commodities and a purchase centre for the provisions, military supplies, manufactures, and food products the Republic no longer sent to its own Caribbean colonies. Through the bounty courts Guadeloupe also exported its reduced crops of sugar, coffee, and cotton. But the institution of the French bounty court in Gustavia could also be a political and economic nuisance for the local administration, at times an insufferable one. Small French corsairing vessels arrived on a daily basis in Gustavia, and these would habitually harass merchant vessels frequenting the Swedish free port. An infamous case strained relations between the revolutionary authorities on Guadeloupe and the administration on St. Barthélemy to a breaking point. In late 1795, a French corsair seized an outgoing Danish sloop at the roadstead of Gustavia, and after having disembarked some crew members on the sloop for a forced voyage towards St. Martin for adjudication, the corsair assuredly and calmly moored in order to report to Bigard. Besides violating territorial waters with belligerent actions, local merchants were understandably appalled by similar incidents. The event was significant enough to rally vociferous protests from local inhabitants and some of the Swedish officials, duly noted by the authorities on Guadeloupe.

The subsequent period was characterised by a problematic relationship between local Swedish and French interests. Direct, formal conflicts were however increasingly rare, as French corsairs stationed in Gustavia had learned that there were indeed some limitations that had to be observed. The Swedish administration had little if any means of opposing foreign powers with force. The local garrison was hamstrung owing to years of neglect, and attempts to form a local militia out of the island populace were unpopular and never successful. In fact, as Ale Pålsson shows, one such initiative led to a mutiny, which momentarily wrung control of the island out of the hands of the Swedes in 1810. Other legal and political conflicts with Guadeloupe followed. Another problem was the regular kidnapping of slaves by French corsairs. Local slaves were seized and emancipated if they would willingly be recruited to the French corsair fleet.Footnote 15

Other belligerent French actions in the region also had an effect on the island population. The Dutch colonies were subject to French capture in 1795, which prompted an exodus of their inhabitants. Nearby St. Eustatius was a source of some considerable immigration. A cohort of St. Eustatius merchant émigrés became naturalised Swedish subjects towards the close of the eighteenth century, and some would be of great consequence for their newly adopted home colonies. The most prominent merchants to move from St. Eustatius, were, as a rule, not Dutch by birth. One of them was the Frenchman Antony Wagthar Vaucrosson, with ties to planter families on Guadeloupe. The transfer of his merchant house and family from St. Eustatius to St. Barthélemy seems to have taken place at the earliest in 1789, because there is no head of family listed with that name in the censuses conducted in 1787 and 1788. However, a warehouse lot in Gustavia had been bought in Antony's name by 1787. In a 1796 census he was listed as the head of a large household of twenty-three people, consisting of five white men, one white woman, fifteen male slaves and two female slaves. He was succeeded in his business by his sons, both of whom lived in St. Barthélemy until the 1830s.Footnote 16 Another notable St. Eustatius arrival was the Italian John Joseph Cremony, once a native of Gaeta in the vicinity of Naples. Born in 1756, he had established himself as a merchant in St. Eustatius in 1781. He seems to have settled in St. Barthélemy by 1796. Both Cremony and the Vaucrossons came to inhabit leading positions in the polyglot community of Gustavia. They were frequent members of the various councils of the island administration and ad hoc committees that furthered independent merchant interests.Footnote 17

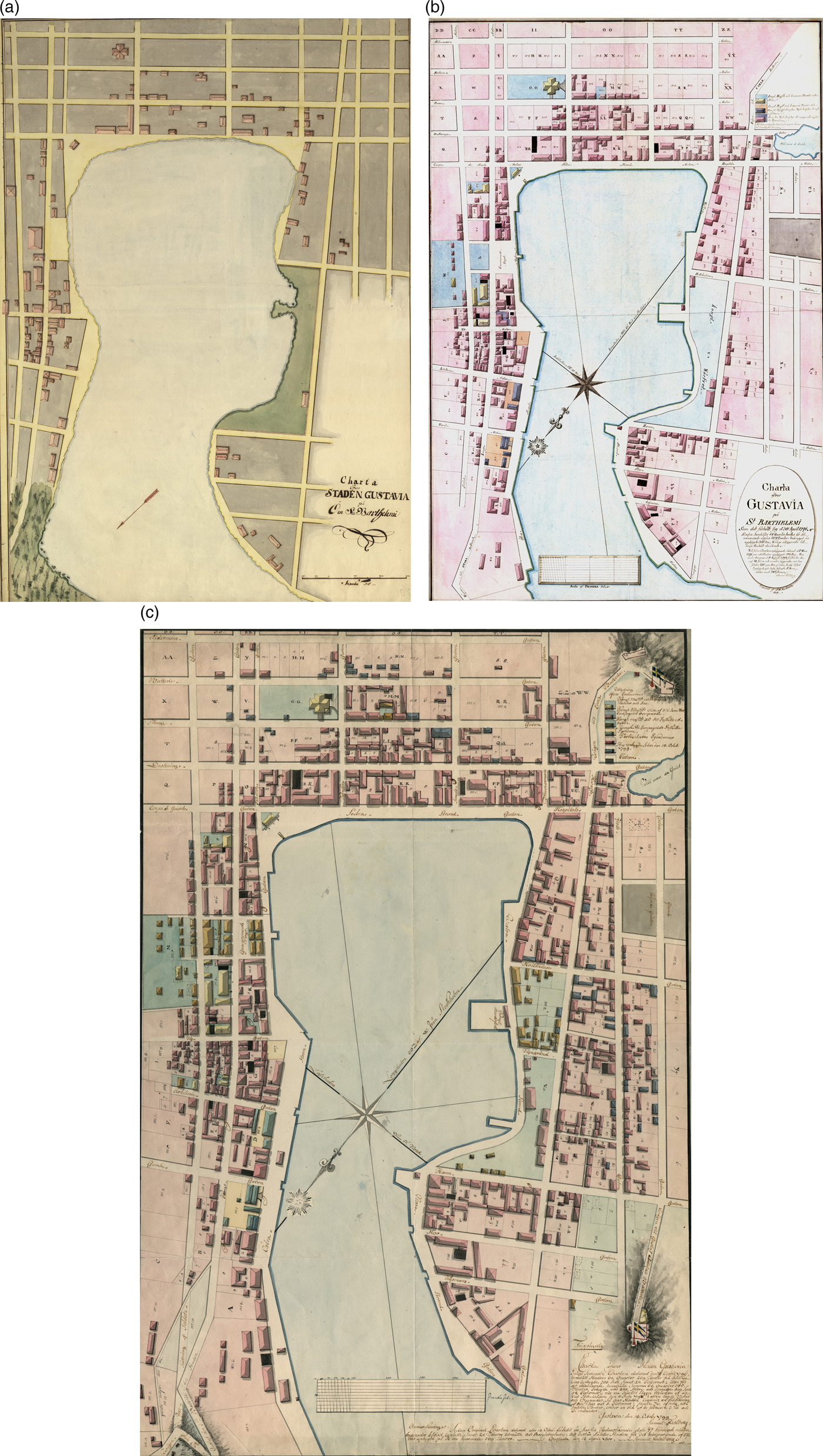

The Swedish judge Johan Norderling wrote a letter to the directors of the SWIC in July of 1795, in which he detailed the positive effects of these movements. He concluded that “all trade in St. Eustache is ruined, all warehouses at the present closed, and the wealthier houses gone away, some here, some to other islands. —A person who left St. Barthélemy three years ago would scarcely recognise the town of Gustavia: The amount of houses are now nearly doubled, some of them quite beautiful.”Footnote 18 It is evident from maps drawn in 1792, 1796, and 1799 (see Figure 1), that the expansion of Gustavia was considerable during this time. In 1791, the town counted 133 separate buildings, while in 1796 this figure had nearly trebled, and in 1800 there were over 800 separate buildings registered, ranging from the largest warehouse to the smallest cooking shed.Footnote 19 Norderling attributed this growth to former St. Eustatius residents moving to St. Barthélemy, and he also hinted at the wealth following in their wake. Others made similar conclusions, such as the SWIC agent Gustav Wernberg, who thought the island could “reap great profits” from the recent immigration from the Dutch colonies, “if only a perfect neutrality would be observed, and that no Nation should be favoured par preference.”Footnote 20 Extant demographic records give an overview of the immigration patterns from year to year (see Table 1).

Figure 1. The last decade of the eighteenth century was characterised by an increasing number of immigrants to St. Barthélemy, the majority of which were concentrated to the port town of Gustavia, depicted in these three maps. They were drawn up—from left to right—in 1792, 1796, and 1799 respectively, by the council secretary and government physician Samuel Fahlberg. They give a lively impression of the urban development during that time. The buildings of the Swedish administration and SWIC can be seen marked in dark yellow in the 1799 map. Swedish Military Archives (Krigsarkivet).

Table 1. Urban population growth, Gustavia, St. Barthélemy, 1788–1806. *This figure includes the total for whites as well.Footnote 21

From very modest beginnings, the urban population of the island soon outgrew the population of the rural hinterlands. Having consisted at first mostly of a few Swedish officials and a local garrison, Gustavia remarkably emerged as a medium-sized city in the context of the Caribbean region. The initial demographic development after Swedish acquisition reflected the immediate needs of the city. Apart from a small community of merchants from nearby islands, there was an influx of workers, artisans, craftsmen, and retailers of different kinds. The existing slave population was used by the Swedes as a labour force for the initial construction of the city, and the slave population increased rapidly during the first years of Swedish governance. It was in any case the political turbulence of the French Revolution and the subsequent wars that had the most significant impact on the city. Between 1788 and 1796, the urban population had grown threefold, from 656 to 2,051 inhabitants, owing to the recurrent waves of immigrants and refugees. In 1806, the city's white and free coloured populations were nearly of equal size, with 835 whites and 802 free persons of colour, while the slaves numbered 1,424 individuals.

Regarding urban slavery, women were not in a clear majority, which would generally be the case for other urban areas in the region. It has been suggested that the trade-oriented economy of Gustavia demanded a greater variety of labour forms, and thus did not display the same dominance of domestic urban slavery as elsewhere.Footnote 22 Extant letters of naturalisation or burgher protocols for the early period of Swedish governance on the island are rare, so it is not possible to chart immigration patterns with individual precision. Nonetheless, the available evidence shows quite convincingly that the last decade of the eighteenth century was a period of growth and consolidation for Gustavia. It also shows that this particular development was due to external factors, such as the conflicts affecting nearby islands after the French Revolution.

After the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War in 1780, which had disrupted Dutch trade in the region, only Denmark and Sweden remained as neutral Caribbean powers. St. Barthélemy and Danish St. Thomas and would soon supersede St. Eustatius as the chief free ports in the Caribbean. After the British occupation of the Danish Caribbean islands in 1807, St. Barthélemy was the sole formal free port in the region, until St. Thomas and St. Eustatius were restored to their former owners in 1814–15. The available documentation of merchants and their activities within the context of Caribbean free-port trade is fragmentary and complicated. A central problem is that private merchants’ archives have rarely been preserved, and the clandestine and illicit nature of the trade obscures the picture presented by available records. Statistical accounts for the trade through St. Barthélemy also leave much to be desired in terms of precision and consistency, but there is enough indirect evidence to glean a general picture of trade patterns around the beginning of the eighteenth century. Another indirect method is to study British vice-admiralty court records, as they functioned as prize courts for British seizures in the Caribbean Sea. They were responsible for the adjudication of vessels captured by British naval and privateer vessels during wartime, and can offer some insights into the free-port traffic as the merchant ships employed in that trade were frequently stopped, searched, and condemned by the British.Footnote 23

British imperial control in the Western Hemisphere had changed radically after the secession of the American colonies, and the Americans had emerged as independent neutral carriers, supplying Caribbean colonies with essential food supplies and other provisions. A process of pragmatic British imperial reform that had been initiated in 1783 after the Seven Years’ War was reinforced after the loss of the North American colonies. The British Free Port Act and the so-called licenced trade with the Spanish and former French colonies were far more sweeping and far-reaching than any concessions made to the independent Americans. Other Caribbean powers also modified their models of colonial trade, experimenting with limited forms of free trade. Despite this process of liberalisation, exclusionary principles were still in effect. One prime point of contention between belligerents and neutrals was the legal argument over whether belligerent goods carried in a neutral vessel were inviolable upon the principle that “free ships made free goods.” This argument followed after the reluctance of neutral carriers to allow searches by belligerent cruisers while at sea. Likewise, neutrals maintained a narrow definition of contraband, claiming that it did not include provisions. The same held for the definition of a blockade, as neutrals claimed that a blockade had to be effective in practice, not just asserted by proclamation.

There were also principles mainly developed by the British prize courts, such as the Rule of 1756, the opposition to the use of “ports of convenience” (i.e., free ports) by neutrals, and the doctrine of “continuous voyages.” The Rule of 1756 was the contention “that a neutral has no right to deliver a belligerent from the pressure of his enemy's hostilities, by trading with his colonies in time of war, in a way that was prohibited in time of peace.”Footnote 24 Direct trade between belligerent ports and friendly neutrals was prohibited as it was simply a branch of trade which had not existed during peacetime. Lastly, the principle of “continuous voyage” concerned the re-export of belligerent cargoes from neutral ports. Direct trade between belligerents and neutrals had of course always been illegal. However, merchants countered this in a circuitous way by the use of neutral “ports of convenience” for transshipment, ostensibly changing ownership of transported cargoes in the process. For example, neutral carriers such as Americans who were prohibited from carrying cargoes from Caribbean colonies to Europe “broke” their voyages from the Caribbean by calling at free ports or American ports on the Eastern Seaboard, and proceeded from there to Europe, having disguised what was in reality one continuous voyage.Footnote 25

It is quite clear that more than one of these principles were frequently violated at St. Barthélemy, aside from the obvious British discontent that was stirred by the French bounty courts operating there. When war broke out in April 1793, the British government was determined to stamp out the trade to French Caribbean colonies by neutral vessels. This involved the effective application of the Rule of 1756 and the rule against direct or continuous voyages between belligerent colonies and their mother countries. This involved an increased naval effort in prosecuting these rules. Much to the lament of St. Barthélemy merchants and the Swedish administration, locally registered vessels were affected by a great number of confiscations. Amid the protests, pretensions of innocence were hard to prove, as Swedish officials knew too well that the largest portion of the island's trade consisted of smuggling. It was also obvious that this contraband trade was directly linked to the French colonies, “from whence we get our sugar, coffee, cotton, rum, cocoa &c.,” as Norderling had pointed out to his superiors in Stockholm.Footnote 26 While the British orders-in-council in 1793 were aimed at the economic deprivation of France and its colonies, they were a gross diplomatic miscalculation insofar as they drew heavy protest from the United States, which led to a partial reversal of the orders-in-council in the latter part of the 1790s. During much of the French Revolutionary War it was in the interest of the British government to follow a more solicitous policy towards neutrals than had been customary in previous wars. The Americans in particular, whose trade with Britain itself was more important than it had ever been, received some deferential treatment throughout the war. The free ports themselves also drew direct scrutiny from the British. When news reached London about the formation of the League of Armed Neutrality in 1801, British war secretary Henry Dundas sent secret orders to the military and naval commanders in the Leewards to seize the islands of St. Thomas, St. Croix, St. John, and St. Barthélemy, and all Danish, Swedish, and Russian goods discovered there. The islands were occupied and were only returned after the Treaty of Amiens was signed in 1802.Footnote 27

Despite the toll taken on St. Barthélemy merchants and Swedish commercial interests during the war, the last decade of the eighteenth century was a period of increasing profitability for the island. Consisting of negligible sums in 1791, the incomes from port duties and tariffs shot up and hit a high point of over 40,000 Spanish dollars in 1799.Footnote 28 The island's population was dominated by a range of different merchants, nominally Swedes but in reality French, Dutch, Spanish, American, English, and other nationalities. These merchants successfully bartered for incoming cargoes from North America or Europe, bought or chartered the necessary ships, and traded to and from ports in the Caribbean formally closed to foreign traffic. The SWIC itself, which was the most privileged commercial actor on the island, was instead hampered by severe difficulties. At home, it failed to attract enough capital among Stockholm investors, and on the island it had problems with incompetent factors and agents. On average, the SWIC launched two expeditions from the Baltic to the Caribbean each year, and the company remained as a sort of nonentity on the island until its dissolution, which began in 1805.

During the period 1793–1802, there were seventeen cases involving St. Barthélemy ships tried in the British vice-admiralty court of Jamaica.Footnote 29 One of the most curious cases involved the Swedish ship Medborgaren (The Citizen), under captain Schale, of 200 tons. A local SWIC agent reported the arrival of the ship at St. Barthélemy in early July of 1797, hailing from Gothenburg, where it had been sent out on a voyage by its owner, L. E. Yvon. It had a cargo of wines and assorted dry goods addressed to a local Swedish merchant house in Gustavia, and was said to prepare for a voyage to Bordeaux with a return cargo of coffee and sugar.Footnote 30 The ship's departure is unknown, but Medborgaren, ostensibly the same ship, turns up in vice-admiralty records the next year, because she was taken off Jacqmel on 2 December 1798 by HMS Diligence, and sent into Jamaica for adjudication. The captain was now a man named Eyserman, and it was now reported that the vessel had set out from Gothenburg to the United States by way of St. Barthélemy, but after leaving the Swedish colony, while driven off course by bad weather, she was taken by a French privateer, carried into Santo Domingo, and condemned in the Spanish admiralty court. The supercargo repurchased the ship, only to see it impressed by the Spanish authorities and sent to Jacqmel with 154 slaves and 29 passengers. On 28 February 1799, the vessel was acquitted, but the slaves were decreed British recaptures. The ship's misfortunes were, however, far from over. After leaving Jamaica without a cargo, she was seized by HMS Abergavenny on 21 May 1799. This time, the prize court uncovered fraud in the alleged ownership. The original owners were said to have been not L. E. Yvon of Gothenburg, but Öström Procter & Co. of St. Barthélemy. Somewhere down the line, she had also been sold to one J. Haasum. Ultimately, the ship was condemned as French property on 24 June 1799, being said to have been on her way not to St. Barthélemy but to Hispaniola.Footnote 31

The case is important in the context of free-port trade during this time, because it illustrates just how deceptive the records can be. There are enough indicators that the ship Medborgaren reported by the SWIC agent and the ship seized by British naval cruisers are one and the same. At the very least, the ship documents investigated by the vice-admiralty court on Jamaica had the same origin as the one sighted at St. Barthélemy. There were very few “proper” Swedish ships arriving from the Baltic to St. Barthélemy at this time, no more than three to five a year. A ship of that size, and with a destination south of Cape Finisterre, had to be issued with a so-called Algerian passport as protection against North African corsairs. St. Barthélemy merchants had very limited opportunities to obtain such a passport, and local restrictions on the island entailed that they could only register ships with Swedish flags with a maximum tonnage of twenty Swedish lasts (approximately fifty tons). Lastly, the name Medborgaren was not a very common christening of a Swedish ship at the time. In any case, one is still somewhat at a loss as to determine what exactly the plans were for Medborgaren and her owner(s), as the only surviving documents seem to display an array of smoke-and-mirrors tactics by her owners and crew to distort the truth behind her voyage.

After the resumptions of hostilities in 1803, the activities of the free ports quickly regained their pace. In 1805, a total of 1,391 ships entered the harbour of Gustavia. Over 75 percent of these arrivals, or 1,051 vessels, were Swedish-flagged and registered in St. Barthélemy. They arrived with cargoes from neighboring islands. Of the remainder, 192 arrivals were American, 74 Danish, 59 English, and the remaining 15 were Spanish and French vessels. The trade patterns offered by these scant statistics show that the bulk of the Swedish vessels carried colonial products such as coffee and sugar into the island, while the American and English vessels carried victuals, provisions, building materials, and dry goods. This general picture would seem to confirm that there was an exchange between local (presumably French) colonial markets and the North American and British colonial markets, while there was a minority of transatlantic trade, with 103 arrivals from Europe and 5from the west coast of Africa.Footnote 32

Slightly more detailed information can be gained from a close reading of records pertaining to private merchants. This is certainly possible by examining the wealthier actors among the St. Barthélemy merchants, such as the Italian Cremony. Judging by the lists of issued passports, they held the largest individual cabotage fleets in 1804–06. For example, in 1805 Cremony had taken out passports for thirteen smaller vessels between eleven and eighty-four tons. He was a well-connected merchant with an extensive commercial network, extending at least through the borders of the British, Spanish, French, and Dutch territories in the Western Hemisphere. His small cabotage fleet aside, he held shares of plantations in Guadeloupe and French St. Martin. His business activities necessitated the use of a small staff of clerks in Gustavia, as well as an agent of his firm posted in St. Eustatius. He also acted in the capacity of agent for actors elsewhere, such as Liverpool slave traders Robert Todd & Co., who used the services of Cremony and the port of Gustavia as an intermediary port en route to the larger slaving hub of Havana.Footnote 33

There were also St. Barthélemy merchants directly involved in the slave trade, but there is nothing to suggest that the slave trade was more than a modest branch of the overall commerce of the island. The SWIC initially planned to engage in the transatlantic slave trade, but these designs were abandoned after the company encountered difficulties in the financing stages of a first slaving voyage. There were however Swedish merchant houses on the island well established in the regional slave trade, which showed a pattern of both transatlantic and intra-Caribbean voyages. The growing plantation economy of Cuba and the liberalisation of rules governing the import of slaves into Spanish America created a boom of regional slave imports. At least nineteen Swedish slave ships arrived in Havana during the period 1790–1820. Despite the relatively small share it held in a regional context, there is still a high degree of uncertainty regarding the extent and nature of the Swedish slave trade.Footnote 34

High Tides: St. Barthélemy as an Anglo-American Port of Convenience

The political and economic landscape of the Caribbean was again subject to the machinations of European conflict in 1807. The second period of the Napoleonic War in the Caribbean was characterised by a British “imperial sweep,” that is, an initial spurt of neutral seizures, the provocation of Denmark into war, and the systematic British conquest of enemy colonies. Anglo-American relations disintegrated as Americans grew more and more dissatisfied with the methods of the British blockade of the European continent. Furthermore, American merchants were increasingly uncomfortable with the virtual monopoly exercised by the British in the Caribbean, a discontent which ultimately sparked an outright war between the United States and Great Britain in 1812.Footnote 35

The repercussions of the ongoing conflicts naturally showed, and entailed serious consequences for St. Barthélemy. Of the utmost importance was the British occupation of the French islands between 1808 and 1810, and American legislation against Britain and France. With the American Embargo Act of 1807, another major market had been closed for the Swedish colony, which had thrived when it could function as a middleman between North America and the surrounding islands. 1808 was a dismal year for the island, punctuated by food crises and a general stagnation of commerce.Footnote 36 The embargo, as well as the Non-Intercourse Act of 1809 which replaced it, was pernicious for American merchants as well. Both measures became subject to widespread evasion. It did not take long before Americans began to exploit profitable substitutes for the Caribbean trade cut off by British conquests, particularly through their newly acquired port of New Orleans, but still found themselves restricted. One method American merchants could theoretically use to circumvent the enforcement of embargoes as well as possibly evade the British was by becoming Swedish burghers in St. Barthélemy. In 1809 this was a clear concern among already naturalised inhabitants on the island. Anticipating the effects of the Non-Intercourse Act, some twenty odd St. Barthélemy merchants petitioned the island council, stating:

We believe that our Flag will be in the number of those to be Exempted from the Resolutions of that Act [The Non-Intercourse Act of 1809] and least the benefits to arise almost Exclusively, to us, from such an Exemption should become a Temptation to the unthinking to Pervert the Friendly character of it, and by a Practice too Flagitious to deserve particular qualification, lend it to others, we beg leave to come forward with our Humble representations on an occasion which appears to us to be of great Importance to the Prosperity of this Colony, and to the least Individuals in it.Footnote 37

From a rather vague opening statement, it becomes clear that they were concerned with an impending influx of Americans, as they “have seen of late that hardly a single vessel is come to this port with the American Flag, which has not gone from it with our own.” The petitioners were obviously concerned about external competition, but draped their plea with moral arguments when discussing the perceived American threat. The administration answered the call by limiting the issuance time for passports to four months instead of the customary six, as well as instituting a bond for shipowners which could only be repaid upon the return of a vessel to St. Barthélemy.

All this was put into effect in order to prevent the “abuse of the Swedish flag,” and of course to please the resident merchants. The institution of these rules could not do anything about the Swedish island's dependence on American traffic, and ironically, it was American traffic that would bring about a new time of prosperity after the economic slump in 1808. In 1809, collections from port dues shot up to record heights, with over 100,000 Spanish dollars due to taxing of the arrivals into Gustavia during that year. Following the extracts of St. Barthélemy port journals (Table 1), the coming years followed the same trend, with 1,793 arrivals in 1811, 2,140 in 1812, and 1,442 in 1813.Footnote 38 American and British ships were the main carriers, each representing around 30 to 50 percent of the yearly tonnage imported into the colony. This suggests that St. Barthélemy was indeed neutral meeting ground between British and American traders. At other localities in the Caribbean, Great Britain enjoyed decided advantages, such as in trade with Spanish colonies after the treaty with Spain in 1808.Footnote 39

The War of 1812 became the high-water mark for the history of the Swedish colony, as it was the only neutral free port open in the Caribbean during that time. The Swedish crown had taken over direct control of the island in 1811, and was the beneficiary of the funds that poured in from the Caribbean. Some indication of the extent of the island's trade can be gained from American export statistics: albeit in a lean year, almost 20 percent of the total exports of the United States, from 1 October 1813 to 30 September 1814 went to St. Barthélemy.Footnote 40 The population of the Swedish island also swelled to 5,492 in 1812.Footnote 41 Former St. Eustatius merchant Abraham Runnels had been among the merchants who petitioned against the American competition gaining a foothold on the island. He explained the current situation on St. Barthélemy before the outbreak of the war in 1812 in a letter to the Swedish Trade and Finance Department:

We subsist almost altogether by our intercourse with the People of the United States; and are Active or Languid, in proportion to the demands of the British Possessions in these Seas for the surplus of what we receive from them, and to the Demand in America for what we get in return from those possessions, or what they bring to our Door. And this Excess, consisting without Exception of articles of Necessity. The Stock of them, is seldom suffered to lay long on our hands. Many valuable commodities of American export, not being suffered to be legitimately introduced at British Ports, we become the cheap purchasers of or the advantage[ou]s depositories of them, untill they can be runned into their markets, in such small parcels, as either do not attract the Notice of their Revenue Officers, or when sacrificed to their vigilance, does not Amount to a discouragement from new attempts!Footnote 42

While the capital and goods following in the wake of the Anglo-American trade was welcome, it was still only earned by an illicit smuggling trade made on American and British terms. An interesting detail about the port journal records from 1813 is that while American traffic fell off after the declaration of war, an inverse development occurred with Swedish St. Barthélemy vessels. Having consisted of nothing more than 4.1 and 15.2 percent of the total tonnage imported to the island in 1811 and 1812, 1813 saw these vessels haul the majority of the tonnage through the island. It is very likely that the Americans were increasingly disguising their cargoes under Swedish flags of convenience, just as local merchants had anticipated.

Aftermath: Conclusions after the Vienna Peace Treaty of 1815

As quickly as hostilities had increased the prosperity of St. Barthélemy during the last phase of the Napoleonic Wars, the subsequent period after the peace treaties in Ghent and Vienna was characterised by an equally dramatic dive in commercial activity. Since the month of April in 1816, hardly any surpluses from the colonial chest could be remitted to Sweden. The Swedish crown, having gained more insight into the financial conditions of the colony after 1811, also drew an important conclusion: as long as the war would last, St. Barthélemy would play a role in the Caribbean economy and thus lend some benefit to the Swedish royal coffers, but as soon as war ended, it would be best if Sweden got rid of the island. After Jean Baptiste Bernadotte became Charles XIV in February 1818 he addressed the problem of St. Barthélemy, gaining permission from the Estates to sell the island. The issue was only to find a purchaser, which, however, never materialised. From the 1820s onwards, profits from the Swedish island plummeted and the population dwindled accordingly. Sweden finally managed to get rid of the colony in 1878, when the island was handed back to France.

The economic success and rapid urban development of Gustavia was primed by a number of complex migration waves during the initial phase of the French Revolution, and rapid economic growth only became apparent after war broke out in 1793. While immigration from the French colonies was significant, the future cosmopolitan makeup of Gustavia was a reflection of early movements of settlers from other polyglot societies like St. Eustatius. In the wartime conditions after 1793, commercial activity increased in the Swedish colony. The colony thrived by virtue of an exchange of colonial goods from surrounding, mostly French islands, with the markets of North America, and to some extent, the markets of Europe. While the relationship with the French colonies was important, it also entailed political and legal problems particular to the Caribbean region.

After the resumption of war in 1803, St. Barthélemy became more and more dependent on the American carriers and traders, which finally showed in the later stages of the war. The intercourse between the belligerent United States and Great Britain at St. Barthélemy served as the island's main rationale after British conquests had redrawn the political map of the region. The entire history of St. Barthélemy under Swedish ownership shows quite clearly that the prosperity of the island was due to the wars and enduring trade conflicts that made it a convenient entrepôt for traders who needed to route goods in transit to otherwise closed markets. Swedish neutrality also functioned as a convenient cover for the cadres of merchants and maritime transients passing through the colony, who assumed—often pro forma—Swedish burgher rights for the privilege of flying a neutral flag. Or as one former Swedish colonial official, O. E. Bergius, writing in 1819, put it: “a free port is but a marketplace, that is borrowed to foreign traders, nothing more.” Whereas its importance to Swedish commercial and political interests was negligible in the long run, Gustavia's relatively short period of importance helped ensure the continuity of a centuries-long tradition of illicit regional trade.Footnote 43