I first encountered Joan Miller while dancing with Forces of Nature Dance Theatre. In rehearsals, acclaimed founder and artistic director Abdel Salaam would frequently cite his “dance mother” in movement quotations of her unique gestural vocabulary, “Millerisms,” such as a hand pulling off an astonished face or a fist twisting into an opened mouth, and in references to her distinct satirical, postmodern choreographic voice. Miller used satire's subversive edge in her choreography to reveal contradictions within accepted thought and institutions, with the aim of social transformation. Her satirical approach is illustrated in an excerpt of her work, performed by Baba Chuck Davis—her former student and the celebrated founder of DanceAfrica, the Chuck Davis Dance Company, and the African American Dance Ensemble:

He begins singing in a low baritone. “My country ‘tis of thee.” As he continues, he begins to stumble over the words, “Work land of misery. Of thee I moooaaaan.” He exhales a labored sigh. Following the lines, “Land where my fathers died. Land of the pilgrim's pride,” his face slides into a sardonic expression.

Here, Miller misquotes a performance of patriotic pride. She repurposes this national anthem, a nationalist pedagogical tool aimed at educating citizens on the American value of freedom, for her own ironic analysis, Signifyin’ on its internal contradictions.Footnote 1 In Miller's satire, misery is substituted for liberty, as the freedom that the song would let ring remains elusive in a land haunted by its history of genocide and enslaved labor.

In previous scholarship, Carl Paris established Miller's work as an important intervention in postmodern concert dance, emphasizing her contribution of bringing questions of race, gender, and social conflict to bear on the choreographic strategies and aesthetics associated with Judson Dance Theater (Paris Reference Paris2001). Takiyah Nur Amin argued that Miller's work constitutes a significant Black feminist contribution to African American intellectual history in the context of the Black Arts Movement (Amin Reference Amin. Takiyah2011). This article builds on these arguments by examining the ways Miller's work hovers between the realms of “Black dance” and postmodern dance, and by elaborating the role that queer desire and diaspora play in Miller's Black feminist choreographic strategies in the context of Black power activism. Through a promiscuous range of approaches to movement, Miller crafted trenchant, satirical choreographic interrogations of normative beliefs surrounding desire and desirability in both white and Black nationalisms. Her choreography affirms the capacity to desire differently, provoking considerations of other ways of being in the world.

Refusing the Rote

Joan Miller was born in 1936 in Harlem, New York, to middle-class immigrant parents from the Caribbean. Her mother was Jamaican, and her father was from St. Lucia (Paris Reference Paris2001).Footnote 2 She remembers her Catholic school education as a reproduction of social norms:

The whole rote thing … I didn't know what I was saying. The catechism. You just repeat. And I was good at it, which was why I never raised my hand when I got to college, because I didn't know that I could say anything … ask me about what was on the page and did [I] have an opinion about it and would [I] have done something differently. No. I just do what I'm told. (Amin Reference Amin. Takiyah2011, 118)

Her critique of this “rote” form of education—regurgitating information as a form of social conditioning, rather than developing critical analysis to inspire new thinking—would become a key theme in her choreography. For example, in an early piece of Miller's, Robot Game (1969), the dancers wear red tape recorders playing phrases of everyday etiquette—“Hello. Fine, thank you. How are you?”—juxtaposed against a film projection of a “collage of marching feet, a gas-masked Uncle Sam and people with guns for heads” (Hering Reference Hering1972, 26). Miller describes the piece as exploring “the rote aspect of living, the inability to be creative, the inability to be daring, the inability to get out of the box” (Amin Reference Amin. Takiyah2011, 67). Robot Game interrogates the intersection of normative conditioning with the violence of nationalism, conveyed through satire and multimedia juxtapositions. These would all become signature characteristics of her later work.

After high school, Miller's parents encouraged her to pursue a stable occupation as an educator. She graduated from Brooklyn College in 1958 with an undergraduate degree in physical education. This was directly followed by a master's degree in dance education from Columbia University's Teachers College, which she earned in 1960. Shortly afterward, Miller attended the Juilliard School on a John Hay Whitney Fellowship. During the summers, she began to study with modern dance choreographers Doris Humphrey and José Limón at Connecticut College and with Louis Horst in New York. She danced with former Limón dancer Ruth Currier between 1960 and 1967, as well as in Rod Rodgers's company from 1964 to 1968 (Amin Reference Amin. Takiyah2011). Miller also worked with members of Judson Dance Theater—including Yvonne Rainer, James Waring, and Remy Charlip—between 1965 and 1968 (Lewis-Ferguson, Reference Lewis-Fergusonn.d.). She formed a long-term artistic relationship with Judson choreographer Rudy Perez.

After a one-year appointment at Smith College, she was hired to teach modern and folk dance in 1963 at Hunter College's Bronx campus, which became Lehman College in 1968. In 1970, Miller became the director of Lehman's dance program, implementing BA and BFA degree programs at the first CUNY college to have a dance program (Kaminsky Reference Kaminsky2017). She directed the program for the next thirty years. That same year, she founded her company, the Joan Miller Chamber Arts/Dance Players, and premiered her signature solo, Pass Fe White, which she had been developing since 1968. In her choreography, Miller critiqued desires for normative subjectivity by deploying a satirical mode of a strategy I call diaspora citation to contest nationalism and imagine Black feminist forms of belonging in the world beyond “rote” conditioning into “proper” citizenship.

The Practice of Diaspora Citation

Whereas Miller's work has been positioned in the United States via its engagements with the Black Arts Movement and the development of postmodern concert dance, her choreographic references also move beyond the nation and toward a sense of belonging to the African diaspora—the dispersal of African people and their cultural practices across the globe. This sense of belonging in her work is constructed through diaspora citation: a strategic deployment of choreographic intertexts by twentieth-century African American choreographers to critique the terms for national belonging and affirm diasporic alternatives (Wells Reference Wells2020). Looking to Miller's satirical deployment of diaspora citation reveals what is at stake in her Black feminist critiques of nationalism and her turn to diaspora: the conceptual figure of the “human.”

In the United States, the terms for proper national belonging have been established through the abstract figure of the “human” as citizen—a philosophical form of personhood historically and legally defined through property in the person as white, propertied Man. This has resulted in the exclusion of African Americans from full citizenship (Harris [Reference Harris, Crenshaw, Gotanda, Peller and Thomas1993] 1995).Footnote 3 The terms of citizenship have been shaped by historical, legal structures that designated some people as objects of property and others as owners. This foundational national contradiction—between the constitutional rhetoric of freedom for all “men” and the fact of enslavement—was obscured by the law's sanctioning of “the moral and intellectual jujitsu that yielded the catachresis, person-as-property” (Spillers Reference Spillers2003, 20). As the legal system naturalized whiteness (and maleness) as “the quintessential property for personhood” and “central to national identity,” it cemented these attributes as equivalent to proper citizenship and full personhood (Harris [Reference Harris, Crenshaw, Gotanda, Peller and Thomas1993] 1995, 281, 285).Footnote 4

Black feminist theorists Hortense Spillers and Sylvia Wynter propose that this Eurocentric figuration of the “human” as white, bourgeois Western Man is reproduced through “rote” education into nationalist ideologies (Spillers Reference Spillers2003; Wynter Reference Wynter1994a, Reference Wynter1994b).Footnote 5 The Black feminist/Black studies project outlined in their work seeks to disrupt the knowledge production and dissemination that underpins this national Black/white, non/human binary, which props up racialized gender and sexual hierarchies.Footnote 6 In her work, Miller actively refused “proper” placement in established racial, gender, and sexual hierarchies of national womanhood-as-objecthood. I propose that Miller's refusal of rote education into normative desire—in her pedagogy and her choreography—constitutes a Black feminist critique, which rejects the terms for “proper” national belonging and personhood consolidated in the figure of Man (Collins Reference Collins2002; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989, Reference Crenshaw1991).Footnote 7

Spillers observes that “black writers, whatever their location and by whatever projects and allegiances they are compelled, must retool the language(s) that they inherit” (Reference Spillers2003, 4). The practice of diaspora citation engages in this strategic repurposing by employing embodied modes of Signifyin’—a Black rhetorical technique of revision—to critique nationalism and affirm diasporic belonging. Signifyin’ is an intertextual strategy of indirection developed in African American social contexts, which extends beyond textual and oral communication to encompass gestural expression (Gates Reference Gates1988).Footnote 8 Signifyin’ is also referred to in African American vernacular as “reading.”Footnote 9 A Signifyin’ statement is double voiced—conveying both a dominant meaning and an alternative trenchant social commentary. This technique of quotation-as-appropriation shifts the dominant terms of meaning making in the service of new terms of engagement.

Satire—the humorous deployment of irony to expose and mock corruption or folly in the service of social criticism—similarly intervenes as a counter to dominant discourse. “In satire, irony is militant” (Frye Reference Frye1957, 223). Miller's choreographic satires deployed diaspora citation to quote, recontextualize, and critique institutional structures for accessing “proper” national belonging through proximity to the figure of the “human”: whiteness, education, celebrity, and marriage. She appropriated these national institutions in her work, deconstructing their naturalized character by humorously and incisively “reading” contradictions at the foundation of the status quo. Miller's satirical solo for Davis illustrates her use of diaspora citation: his embodied Signifyin’ on the patriotic song's “rote” conditioning into proper citizenship advances her Black feminist critique of the terms for national belonging, implicitly demanding new terms of engagement.

In what follows, I consider Miller's work through close readings of her semi-autobiographical solos, Pass Fe White (1970) and Homestretch (1973). Pass Fe White has four sections: “Miss Jane,” “Miss Liz,” “Miss Mercy,” and “Miss Me.” “Miss Jane” reflects diasporic relations between Jamaica and the United States, opening a consideration of the color line and the racial construction of American genders. This gender construction is taken to task in “Miss Liz”—a critique of white womanhood via Elizabeth Taylor as a national symbol of desire. “Miss Mercy” simultaneously conveys desires for, and the limits of, Black nationalist separatism. Finally, “Miss Me” affirms Black womanhood in a diasporic structure of belonging. I then turn to Miller's subsequent solo, Homestretch, which illuminates her critique of marriage and education into normative gender performance. I close with a meditation on how Miller lived her choreographic theorizations in everyday life—exceeding conventional gender roles and pursuing her queer desires beyond the dominant, nationalist gender and sexual logics of her historical moment. I argue that the lens of diaspora citation allows an understanding of Miller as a choreographic theorist, offering embodied analyses of the contradictions and limitations of nationalist belonging, while turning to diaspora to imagine and perform Black feminist and queer modes of belonging in the world. Miller's work demands attending to the ways in which she reimagined belonging: queer, Black feminist, diasporic forms that recognize Black women's knowledge in the ecstatic figure of “Miss Me” dancing Black joy.

Pass Fe White

Each section of Pass Fe White is set to a poem (sometimes performed live, sometimes recorded) and accompanied by music and other media, such as slide projections. Regarding her approach to the solo, Miller states, “When I did the actual movement, none of the movement had anything to do with [narrative], and I loved it, and I still love it. I never actually did a—passing—a person passing for white, and they want to be black” (Amin Reference Amin. Takiyah2011, 74). Her choreographic approach juxtaposed movement and text, rather than acting out a narrative. The effectiveness of this strategy is evidenced in a review: “Part of the reason for the strength is that while the taped voice reads a poem about ‘passing,’ the dancer in white racing outfit and goggles steams along her own track. She doesn't attempt to illustrate the poem, and as a result she illumines it” (Jowitt Reference Jowitt1971). My approach to reading Miller's solo mirrors her juxtapositional method to suggest resonances rather than literal relationships between the movement, text, and other media.

The first section, “Miss Jane,” is set to the eponymous poem by Louise Bennett. The movement begins before the poem. Miller's dancing body is clothed from head to toe in white. She wears a white bathing cap, with goggles strapped to her head, a white motorcycle jacket and pants, or white coveralls. She launches repeatedly into a handstand against a black wall, crashing back down, before hurling herself at it again. The last time she suspends upside down. She bends one knee at a time, shifting, switching back and forth. Miller describes this image of herself: “I was the motorcycle upside down trying to right itself with the wheels spinning and trying to find himself and wasn't able” (Amin Reference Amin. Takiyah2011, 73).Footnote 10 The movement physicalizes the impossibility of belonging in a situation of racial passing. Celebrated performer and founding member of Forces of Nature Dance Theatre, Dyane Harvey, conveys her experience of this moment as a dancer who later performed the solo: “No text, no language, no wording, nothing. Just you and the wall. You and the wall. And showing the effort of it, and the frustration of it” (2017). The wall can be understood as a physical embodiment of the color line that the soloist crashes into repeatedly.Footnote 11 As the dancer faces off with the wall, the desire to pass into whiteness, out of Blackness—to advance one's social status in a racist system by performing proximity to the “human”—is rendered a contradictory frustration. “It was about … not knowing who you are, where you are, where you're supposed to fit in, kind of floating, trying to figure it out” (Harvey Reference Harvey2017). The dancer's inversions convey an elusive quest for a sense of belonging.

The history of Black people passing in white America places issues of national belonging in stark relief. Racial passing, a form of ethnic impersonation and identity transformation, has occurred in the American context “for at least as long as people of African descent have had sexual unions with people of European descent” (Smith Reference Smith2011, 11). It is traditionally understood as people who are legally Black choosing to live or “pass” as white, and it is premised on the assumption of stable, impermeable racial categories and legible, fixed racial signifiers, such as phenotype.Footnote 12 Although it may appear that individuals passed simply of their own volition, to enjoy the opportunities and privileges of whiteness, the compulsion to participate in racial passing is a structural feature of the “economic coercion of white supremacy” (Harris [Reference Harris, Crenshaw, Gotanda, Peller and Thomas1993] 1995, 285).Footnote 13 The material and social gains secured by passing were marked by profound loss and fraught with anxieties of disclosure and consequent financial and social ruin.Footnote 14 The disoriented image of Miller spinning her wheels upside down is followed by the juxtaposition of her moving body against her recorded voice reading Louise Bennett's poem “Pass Fe White.”

“Miss Jane”: Diasporic Articulations & Decolonizing Desire “Pass Fe White” by Louise Bennett

Bennett's poem was originally published in the groundbreaking 1966 collection Jamaica Labrish: Jamaican Dialect Poems. Louise Bennett, affectionately known as “Miss Lou,” engaged in satire in the service of decolonization, particularly through her formal interventions, using vernacular language to make arch social commentary: “Through her insightful humour [Bennett] persuaded many colonially educated persons to value aspects of Jamaican heritage they had tended to ignore” (Morris Reference Morris2014, 111). In the poem, Miss Jane is labrishing (gossiping in patois) about how her daughter, whom she sent to college in America, is passing for white:

In “Miss Jane,” Miller's satirical sensibility resonates with Bennett's poetic rhetoric. Miller's former student and company member, Abdel Salaam, observes that “she probably had one of the most amazing satirical voices that I have ever witnessed in dance. But again, for the purpose of constantly posing questions, provoking thought, hoping to stimulate change through deconstruction and renovation” (2017). A comment by Miller reveals the satire's urgency: “For instance there was a line [of the poem] that says … she sent her daughter to America to look about her education, and she tried to work ’pon her complexion instead. So the line comes from Jamaica Labrish. It's a humorous line, but the piece is dead serious” (1989).Footnote 15 The deadly serious critique “reads” the daughter's desire for whiteness, equating it with stupidity—“fail her exam,” “brain part not so bright,” “couldn't pass tru college.” “Miss Jane” claims as “success” the value of belonging in Black communities over “success” on the terms of whiteness: the advancement of the possessive individual.Footnote 16

Miller's recorded voice reads the poem. Her lilting intonation conveys the nuances of Patois inflection, creating a rhythmic soundscape for the movement. These cadences reference her mother's Jamaican accent, which carried sonic traces of diasporic resonance into Miller's childhood home in the United States. Her citation of the text and aurality link a postcolonial Jamaica to a segregated United States, articulating issues of the “white bias mentality” across these contexts (Bennett [Reference Bennett1966] 1995, 211).Footnote 17

Jamaica—US Décalage: Colorism versus Segregation

While Miller joins US and Jamaican contexts through her vocal performance of the vernacular poetic text, her use of the poem as a choreographic intertext also reveals the incommensurable gaps in the distinct perspectives and configurations of power across these diasporic contexts, a phenomenon Brent Hayes Edwards terms décalage (Edwards Reference Edwards2003). The desire for the privileges associated with whiteness surfaces the shared issues around colorism across these contexts, while the décalage is evident in the ways that the legal enforcement of racial lines in US segregation did not occur in the Jamaican context but did impact the ability of Jamaicans to immigrate to the United States.Footnote 18 These diasporic joints and gaps are integral dimensions of the piece's critique of the terms for “proper” citizenship. In Bennett's poem, the father celebrates his daughter's passing as subverting the Jim Crow segregation laws that refused his immigration:

In the wake of his denied application for immigration, his daughter's duping of America constitutes his revenge against the racist Jim Crow segregation laws (Papke Reference Papke2012, 110).

In contrast to the father's celebration, Miss Jane's perspective asserts the family's upper-class status—“dem pedigree is right”—in her preference for an educated daughter, rather than a “boogooyagga” (good-for-nothing) white.Footnote 19 Her perspective also foregrounds the gendered dimensions of the poem's critique of white womanhood. Miss Jane critically observes how white women exploit their structural relationship with white men through their appearance and the proximity to power it affords—compliant and complicit with the dominant terms for social advancement.

Against the voiceover labrishing about Miss Jane and the father's distinct stances, the figure in white drops into a deep crouch, exaggerating the planes of her already angular body. She moves sideways, staying low, shifting the broken shapes of her asymmetrically bent elbows and knees while switching her hips back and forth to propel her along her trajectory. This juxtaposition of movement and text suggests that, whether passing is interpreted as victory or downfall, the experience is one of fugitivity, avoiding detection. Returning to the deep crouch, she balances on the ball of one foot. The other leg trails behind her in a low bent-legged attitude. She propels herself in circles, rapidly scooting around on her hands. Physically referencing the earlier image of spinning motorcycle wheels, this moment simultaneously conveys passing as a disorienting experience and the circularity of arguments premised on the acceptance of racial categories as factual, natural, and stable.

The next section of the solo, “Miss Liz,” elaborates Miller's satirical critique of white womanhood as the national standard of femininity. Before turning to “Miss Liz,” I offer a brief consideration of how the tangled relationship between property and personhood forms the condition of possibility for the color line: specifically, how the “one-drop” rule dividing the color line emerged in a historical context of sexual predation—the enforced reproduction of people-as-property through Black women's bodies in slavery. This context shaped the racial construction of American genders, while the one-drop rule shored up the racial wealth gap via exclusions of wealth and property inheritance among blood relations. The structural aim of Miller's satirical critiques is evident in her skepticism toward institutions that reproduce the terms of normative subjectivity (such as the legal maintenance of the color line), which in turn reproduce a naturalized social order premised on sexual violence and economic exploitation.

Passing the Color Bar: The Gender, Sexual & Racial Contradictions of Patrimony

How to pass the color bar. Bar being the limbo bar, which, when you look at people who are playing limbo, they're in a deep, deep, deep lunge, or a hinge, and they're traveling underneath this bar, but then it's also, as you say, about the legal bar exams.—Dyane Harvey (Reference Harvey2017)

In “Miss Jane,” the dancer descends to the floor, shooting her body forward into space, straight and taut like a board, supported by her hands. She runs in place, low and quick, hiking her knees toward her face. Her hands push against the floor, thrusting her back into a deep squat, with one leg extended. She is suspended in this position, her arms reaching out into space above her leg. Abruptly, she pushes back to sit. She begins to shift her hips, walking forward awkwardly on her butt.

Pass Fe White was choreographed in the wake of legal segregation, in the afterlife of slavery.Footnote 20 Miller's satire indexes the inherent contradictions and absurdities in legal systems of racial classification, which have become naturalized as commonsense. Bennett's satirical double play on “colour-bar” in her poem, following B.A. and D.R. (bachelor's and doctoral degrees), also gestures to the law school bar exams:

Passing the color bar in the United States highlights the legal implications of passing beneath notice into the unmarked position of the abstract “human” and citizen. The economic motivation at the heart of systems of racial classification was obscured by the ways the law used racial pseudoscience to naturalize a social order based on racial domination. The color line was then reified in Jim Crow and anti-miscegenation laws, masking what was chosen (distorted social relations in the service of economic profit) as natural (Harris [Reference Harris, Crenshaw, Gotanda, Peller and Thomas1993] 1995).Footnote 21

The one-drop rule was the initially legal, and later de facto, pseudoscientific classification of a person with any African ancestry as Black. However, legal determinations based on blood as “objective fact” were actually premised on subjective measures, including false reporting of ancestry, shifting definitions of race, and the most flawed assumption of all, “that racial purity actually existed in the United States” (Harris [Reference Harris, Crenshaw, Gotanda, Peller and Thomas1993] 1995, 284). This one-drop definition emerged to preserve the status of white, propertied Man in a social system of domination, which was theoretically based on racial purity, but practically based in widespread miscegenation. In 1661, the common-law presumption that linked a child's status to their father was reversed by assigning the status of Black women's children to their mother. In this way, the law enabled the reproduction of white, propertied men's labor force as an economic asset, while naturalizing sexual and racial violence.Footnote 22

Hortense Spillers has theorized how the rape of enslaved Black women by white men functioned as a form of violent domination, combined with the reproduction of (people as) property as a source of free labor (Spillers Reference Spillers1987). Spillers argues that American genders are also always racialized, indexing the racialized gender and sexual discourses that emerged as ideological screens for economic and systemic domination. While discourses of hypersexuality—what Spillers refers to as “pornotroping”—naturalized sexual violence against Black women, discourses surrounding white womanhood as a symbol of sexual purity, combined with the construction of Black male sexuality as threatening, rationalized the domestic terrorism of lynching as a form of social control (Spillers Reference Spillers1987; Mercer Reference Mercer1994). Floyd James Davis clarifies the underlying stakes: “White womanhood was the highly charged emotional symbol, but the system protected white economic, political, legal, education and other institutional advantages.… It was intolerable for white women to have mixed children, so the one-drop rule favored the sexual freedom of white males, protecting the double standard of sexual morality as well as slavery” ([Reference Davis1991] 2005, 113–114). The terms, including this double standard of sexual morality, were set by those who they benefitted—white, propertied men—and naturalized by racial discourses of gender and sexuality. These conditions determined the lines along which segregation would be drawn. At stake was (and is) the protection of institutional benefits for those who could claim whiteness as their property.Footnote 23

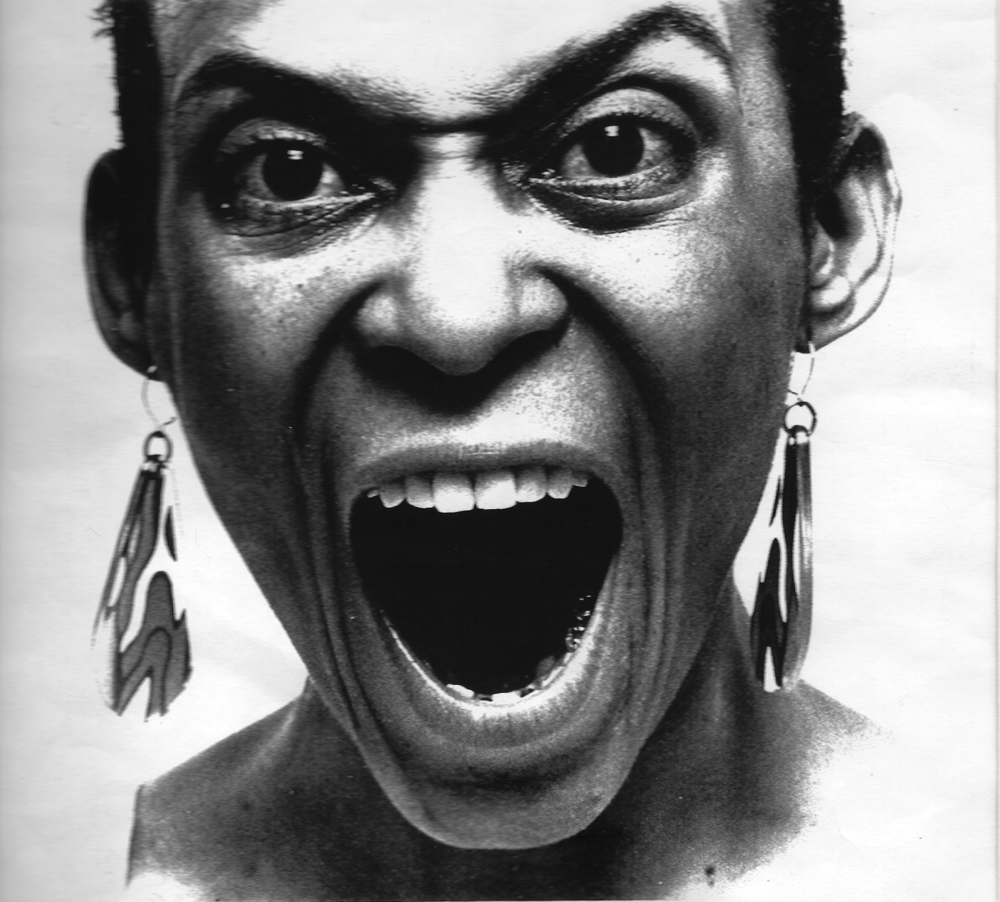

Photo 1. Joan Miller. Photographer unknown. Courtesy Martial Roumain and Sheila Kaminsky.

This extended to the literal inheritance of property. The one-drop rule classified biracial children as Black to uphold the myth of racial purity.Footnote 24 At stake in this myth—belied by the vigilant(e) enforcement of anti-miscegenation laws—were issues of legal inheritance. The legal definition of race secured the literal transfer of wealth, including property, within white families, along with the privileges of whiteness. A fundamental contradiction of status quo racial classification—the false assumption that two people of different races cannot be related—is at the heart of property laws designed to secure and reproduce white wealth.Footnote 25 The historicity of miscegenation, embodied in biracial children and the act of passing, threatened the security of a social order premised on notions of racial purity by raising the specter of interracial, patriarchal contradictions. In Miller's use of Bennett's poem, the daughter's unstable positionality between Black and white troubles the accepted foundations of these national social norms.

The legal enforcement of the exclusionary boundaries of the abstract “human” (and its progeny) through the one-drop rule is founded on the intersection of racial, sexual, economic, and legal violence. Discourses that construct women as various racialized forms of property emerge from this history of violence. This patrimony is an undesirable inheritance. Returning to face the audience, Miss Jane smacks the ground with open palms. Her bent elbows create a frame for her folded knees, which she whips briskly from side to side. She turns away from the audience, kneeling to face the back. In slow motion, she brings her hands to her head, her fingers slowly close around the white bathing cap. Attending to the racial and gendered exclusions of the narrowly defined Western conceptual figure of the “human,” Miller's choreographic critiques conveyed how desires for normativity reproduce a violent, naturalized social order.

“Miss Liz” & Fetishized White Femininity “Poem for Half White College Students” by Amiri Baraka

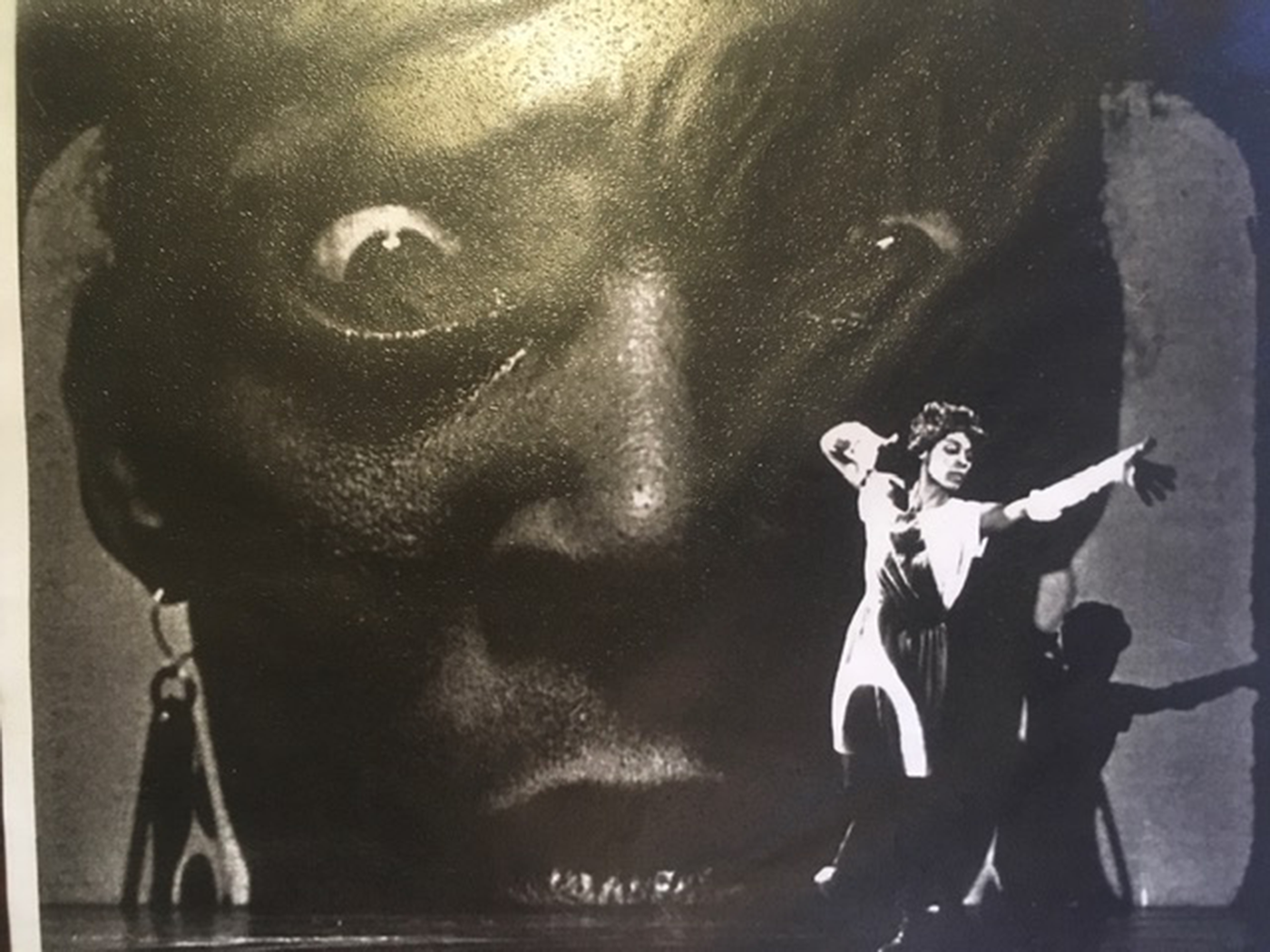

An enormous close-up of Miller's face is projected on the wall behind her. Her eyes are wide, her expression an exaggerated mask of horrified disapproval as she stares down at her own performance of propriety. She stands in front of the projection, upstage left, slightly tipped forward at the waist. Her bent arms form a hanger for a white jacket, which hides her body from view, revealing only her lower legs. She moves sideways, alternately lifting her heels and toes, shimmying across the upstage panel. As she flings the jacket aside, her body is revealed. Clothed in a white tunic, she wears long white gloves and a short blonde wig. The piece ends with her chucking the blonde wig onto the ground, physicalizing the undesirability of occupying this fetishized version of white womanhood. Harvey noted, “Oh yeah, it was a nasty wig. I mean it was clean and everything, but it wasn't styled. It was unkempt” (2017). In “Miss Liz,” Miller's satirical choreographic citations “read” the tropes of idealized white femininity.

“Miss Liz” picks up Miss Jane's critique of white womanhood in the fracture between racialized American genders constructed on the terms of (people as) property. Performed to Amiri Baraka's “Poem for Half White College Students,” “Miss Liz” interrogates Elizabeth Taylor as the paragon of white femininity. Miller's use of this poem references the historical moment of the piece's creation during the Black Arts Movement (1965–1975). Baraka was a seminal figure in the movement, theorizing principles of a Black aesthetic and the propagation of Black nationalist ideas through art (Neal [Reference Neal and Bean1968] 1999). Miller's use of this poem, citing Baraka, conveys her interest in Black Arts Movement themes. A recording of choreographer Rod Rogers reading the poem aloud frames Miller's dancing body.

Photo 2. Joan Miller in “Miss Liz” in Pass Fe White. Photographer unknown. Courtesy Martial Roumain and Sheila Kaminsky.

Baraka's poem interrogates “half white” college students’ investments in whiteness and desires for assimilation. It begins: “Who are you listening to me, who are you/listening to yourself? Are you white or/black or does that have anything to do/with it? … How do you sound, your words, are they/yours?” He repeatedly punctuates the poem with commands to “check yourself” (Baraka [Reference Baraka and Randall1971] 1985, 225). Of particular interest to Miller was the line referencing Elizabeth Taylor: “when you turn from starchecking to checking/yourself … can you look right next to you in that chair, and swear,/that the sister you have your hand on is not really so full of Elizabeth Taylor, ’til Richard Burton is/coming out of her ears” (225). Johari Mayfield, who later performed the solo, remarked, “She really wanted to see that, the embodiment of that line” (Reference Mayfield2017). Miller's citation of Baraka's reference to Elizabeth Taylor Signifies on the American cultural ideal of unmarked, white femininity—an abstraction, in Miller's words, that supposedly “all other women, regardless of race, should aspire to” (Amin Reference Amin. Takiyah2011, 76).

Although Taylor is foregrounded as a choreographic intertext from the poem, an interview with Miller's former dancers and colleagues, Sheila Kaminsky (a former professor at Lehman College and an experimental choreographer) and Martial Roumain (a celebrated performer with Chuck Davis, Eleo Pomare, Alvin Ailey, and many more), revealed that this section of the piece was also informed by the 1959 film Imitation of Life. Kaminsky recalled, “It was about how to get ahead at that time,” and Roumain added, “and the daughter passing for white” (Reference Roumain2017). Elizabeth Taylor rarely sported blonde hair, but in the movie, Lana Turner embodies the national blonde archetype of the Hollywood starlet. Turner's character in the film (as well as her actual persona) parallels Baraka's “read” of Taylor in the poem: they occupy the role of the fetishized, feminine celebrity in white patriarchy (“’til Richard Burton is coming out of her ears”). Together, these blonde and brunette icons of the silver screen articulate the spectrum of the “proper” performance of white femininity embodied in the cult of the Hollywood celebrity.Footnote 26 My reading turns to consider the significance of the blonde wig as an intertextual reference to Imitation of Life. Miller's engagement with this complex cultural text demonstrates her refusal to desire white, feminized objecthood, terms of national belonging configured through histories of property.

Imitation of Life: Deconstructing National White Womanhood

Imitation of Life exists in three versions: the Fannie Hurst novel (1933), the John Stahl film (1934), and the Douglas Sirk remake (1959), which is the most relevant to Pass Fe White. The narrative links the struggles of a Euro-American and an African American woman, each single with a daughter, to a tale of economic success. The white woman achieves Hollywood fame while living with the Black woman (who does the domestic work) and her light-skinned daughter (who tries to pass for white). Lauren Berlant argues that the women's problems result from the exclusions of the abstract citizen: the film “crystallizes the distances between the nation's promise of prophylaxis to the ‘person’ and the variety of female genders it creates … the implicit whiteness and maleness of the original American citizen is thus itself protected by national identity” (1993, 201).Footnote 27 This national identity coheres around a privileged, unmarked position in which cultural authority is secured by de-emphasizing embodiment. This provides a stark contrast to what Berlant describes as the historical “overembodiment” of women in general, and African American women in particular, who “have never had the privilege to suppress the body, and thus the ‘subject who wants to pass’ is the fiercest of juridical self-parodies as yet created by the American system” (177).Footnote 28 The US legal system is premised on this contradiction—the theoretical equality of the individual “person” and the practical embodied exclusions of “proper” citizenship—making the unstable figure of the “mulatta … the paradigm problem citizen” (177).Footnote 29 In Pass Fe White, Miller's choreographic focus on this paradigmatic problem citizen “reads” this juridical self-parody. Her critique of the contradiction, between the legal promise of equal access to the “person” and the subject who passes to secure access to the rights of full citizenship, recalls Chuck Davis in Miller's satire of the nation's promise of freedom, which remains elusive in the afterlife of slavery.

In the film, the white, blonde celebrity operates as a figure of national desire who is complicit in her own commodification. This dynamic of national desirability plays out on a distinct class register in the light-skinned daughter's performance of passing. She mimics the blonde woman's performance of feminized objecthood—becoming a white showgirl and disavowing her dark-skinned mother in the process—revealing her understanding that women gain a public body through the capital of physical allure. This “perverse opportunity to capitalize on racist patriarchal culture … reminds us that the nation holds out a promise of emancipation and a pornographic culture both” (Berlant Reference Berlant and Robbins1993, 202). The “gains” secured through compliance with these terms remain contingent and elusive, as the capital of physical allure inevitably diminishes, while the sacrifices entailed in gaining a sovereign sense of self—the possessive individual liberated from collective pain—are less emancipatory than alienating: the film star winds up alone, “enfranchised but not empowered” (1993, 189).Footnote 30

In “Miss Liz,” Miller references and refuses these terms for success. Tossing the blonde wig to the floor, she turns a critical “side-eye” toward the desirability of sexual objecthood (Itam Reference Itam2017b).Footnote 31 White womanhood offers limited agency on the terms of property, which deny recognition of women's full humanity. The pinnacle of success on these terms for white women, and women who aspire to whiteness, is to exist as a kind of glorified object in national economies of capitalist consumption established by white men. This formula for success is complicit with the status quo oppression of Black women in national economies of desire, in which they are not figured as beautiful, and in national labor economies in which domestic work is defined as a “natural” place for Black women, a place established in the gendered labor economy of slavery. Miller rejects the desire for this mode of personhood.

Miss Liz moves through quirky shuffling and “Millerisms,” her unique gestural vocabulary. Exaggerated, feminine hand gestures, accentuated by the white gloves, are subjected to a breakdown. Sliding into a crossed fourth position, her long arms extend upward, before breaking at the wrists. The broken wrists devolve into chicken wings. Her thin, angular arms break at the elbows, as they crash into her body, rebounding off her rib cage in a circular motion, the bent elbows hanging like broken wings at her side. Miller “reads” the propriety of the Hollywood celebrity by quoting the signatures—the blonde hair, the long white glamorous gloves, the dainty broken wrists—before subjecting them to a physical, theoretical deconstruction. As the voiceover reads, “Check yourself,” she pulls open the neckline of the tunic, peeking into her dress. She yanks off the short blonde wig, hurling it to the ground.

Berlant suggests that part of the problem for the historically “overembodied” is that it “thwarts her desire … to move unconsciously and unobstructed through the public sphere” (174). The contrast between the disembodied, abstract citizen and the lived experience of the historically overembodied registers in one's ease of mobility through public space. This embodied sense of (im)mobility ushers us into Miss Mercy's Black walk.

“Miss Mercy”: “Reading” Overembodiment “One Thousand Nine Hundred & Sixty-Eight Winters” by Jackie Earley

Miller describes the third section, titled “Miss Mercy,” as minimalist: “That was my minimal piece because the poem was read three times [with] cello accompaniment, and all I did was walk down from upstage to downstage and you know how long that took.… I put on a black jumpsuit during the walk. And that was it. No dancing” (Amin Reference Amin. Takiyah2011, 78).Footnote 32 The dancer enters the space in a nude leotard. She picks up a pair of black pants and begins to slide into them. As she pulls them up, they become a floor-length black jumpsuit. A recorded voice reading Earley's poem begins: “Got up this morning/Feeling good and black.… Did black things.… And minded my own black bidness!” (Earley Reference Earley and King1972). Touching her hair, she begins a sultry walk upstage, away from the audience. The dancer sinks slightly into each hip, “feeling” her Black self. Minding her own Black business, she zips up the jumpsuit, facing upstage. She turns deliberately to face the audience, sitting in one hip as she pivots to walk toward them. Against this simple but nuanced action, the voiceover describes Miss Mercy playing her Black records and putting on her best Black clothes. The poem culminates in the protagonist walking out her door: “And …/Lord have Mercy!/White/Snow!” (Earley Reference Earley and King1972). “Lord have Mercy!” is repeated three times, intensifying from a slow drawl to an exclamation, before dropping to a hushed tone on the punch line, “White Snow!” The dancer points to the ground in front of her, snaps her head up to shoot a quizzical look directly at the audience—as if to say, “Oh really?!”—and abruptly walks offstage. Soft chuckles are audible in the audience.Footnote 33

The dancer's subtle, funky walk, set against the poem's text, conveys a desire to wrap herself in Blackness, a departure from the desire for whiteness explored in the previous sections. The poem's use of African American vernacular, along with its title indexing the historical moment of 1968, reflect Black aesthetic imperatives in the Black Arts Movement era: for art making to attend to Black people's ways of knowing and being in the world.Footnote 34 Simultaneously, the piece's satirical ending surfaces the limits of separatism—Black nationalist and Black Arts Movement demands for distinct terms apart from white nationalist norms. Despite Miss Mercy's efforts to create a space completely apart from white influences, she is confronted with those terms the minute she steps out her door. Though “white snow” might initially seem to reference nature rather than the social construct of race, her ironic look confronts the audience, Signifyin’ on “snow.” The coded significance of the simple point-and-look highlights their relationship to the white world, the context that ultimately envelops Miss Mercy, the audience, and the theater.

Miss Mercy's “overembodied” Black walk is burdened by her legibility as both Black and woman, in contrast to the disembodied pedestrian activity of the abstract citizen. Whereas the national public sphere is supposedly equally accessible to all citizens, she points to its condition of uninhibited mobility: whiteness and maleness. Miss Mercy's performance of everyday life for the historically “overembodied”—her thwarted desire to move unhindered and unselfconsciously through public space—“reads” the limits of Black nationalist separatism within the white nationalist exclusions of abstract citizenship. These limitations of the nation as a structure of belonging lead into the final section in Miller's (re)turn to diaspora.

“Miss Me”: Black Feminist Diasporic Belonging “Ego-Tripping (there may be a reason why)” by Nikki Giovanni

She wears a green unitard. Moving on the diagonal, she stretches her arms in opposition, a long leg extended behind her in arabesque. She takes off in a jump—her leg slices sideways, ascending to the ceiling as her bottom foot stretches away—leaving the ground in a moment of expansive flight. Swaggering around in a circle, she breaks into a funky step, placing her hands on her hips, grooving, as she swings them from side to side. A recorded voice reading Giovanni's poem accompanies her celebratory, buoyant movement. It begins, “I was born in the Congo/I walked to the fertile crescent and built/the sphinx/I designed a pyramid so tough that a star/that only glows every one hundred years falls/into the center giving perfect divine light/I am bad” (Giovanni Reference Giovanni1970).

“Miss Me” shifts from Miller's critiques toward her imaginative capacity to desire differently. Signifyin’ is operative in the poem's vernacular appropriation of dominant meanings—“I am bad” (meaning good), and “I am so hip even my errors are correct”—but here the humor functions as an affirmation of a Black female figuration of personhood (1970). “It's a four-part suite that dealt with a woman that was trying to pass for white, and it ends with a woman that has self-confidence, self-pride and the person is eventually called Miss Me, so that she has transcended the trials and tribulations of that era” (Miller Reference Miller1989). In “Miss Me,” Miller proposes a consideration of Black womanhood as a central, rather than particular, mode of subjectivity and a foundational point of departure for constructing diasporic belonging in relation to history. Miller's citation of Giovanni's rhetoric Signifies on patriarchal origin myths that construct Man as the proper subject of History. In the poem, the female protagonist sits on the throne with Allah, gives birth to (precedes) Noah, and turns herself into herself to become Jesus: “men intone my loving name/All praises All praises/I am the one who would save” (Giovanni Reference Giovanni1970).

The poem's intertemporal references create links between the past and the present. Sites of African historical civilizations—the Congo, the fertile crescent, the pyramids, and the Nile—are articulated with 1960s and 1970s Black American vernacular: “so tough.” This framing of history is speculative, deploying the poetic imagery of historical reference points rather than constructing a linear historiography based on empirical evidence of so-called progress. Bound by neither space nor time, Miss Me's flights of historical fantasy are in pursuit of something beyond the limitations of the present determined by a reproductive logic of the status quo—reinforcing existing arrangements as “natural” and therefore beyond intervention. As a dancer who later performed this section, Harvey described the movement as “being like what I wanted to do. Break me out. Let me dance.” She situated this feeling within a paradigm of diasporic belonging, describing her interior journey as a performer through the poetic references as enabling a “sense of a global Blackness” (2017). Miss Me, breaking out into this sense of global Blackness, performs the impulse of queer diasporic belonging described by Nadia Ellis as “an urgent desire for an outside—an outside of the nation, an outside of empire, an outside of traditional forms of genealogy and family relations, an outside of chronological and spatial limitations” (Reference Ellis2015, 4).

In this section, Miller performs a desire for a world in which the contributions, power, and beauty of Black women are not only acknowledged but understood as foundational. Her performance of dancing Black, femme joy affirms the desires of Black women creating and claiming beauty in a world that insisted that they had no claims to it. Giovanni's poem claims the female protagonist's bodily discharge—excrement, fingernails, mucus, hair—as a source of immense value, producing diamonds, uranium, jewels, oil, and gold. One line states the point directly: “I am a beautiful woman” (1970). Saidiya Hartman contends that the “autobiographical example is not a personal story that folds onto itself; it's not about navel gazing, it's really about trying to look at historical and social processes and one's own formation as a window onto social and historical processes, as an example of them to tell a story capable of engaging and countering the violence of abstraction” (Saunders Reference Saunders2008, 7). “Miss Me,” as the climax of Miller's semi-autobiographical Pass Fe White, counters the violent abstraction of humanity into the “human” and the abstraction of beauty into objectified white femininity.

Dancer Johari Mayfield, who later performed the piece, describes the first three sections as an examination that moves between various binaries—black/white, inside/outside—and the performance of personas associated with those prescribed, fixed oppositions. In contrast, she describes “Miss Me” as a movement beyond those limitations, in which the soloist “graduate[s] to being human” (Reference Mayfield2017). This conception of being human emerges from the premise of Black women's lived experiences and ways of knowing. The soloist occupies a world in which Black women move freely across space and time: “I mean … I … can fly/like a bird in the sky …” (Giovanni Reference Giovanni1970). “Miss Me” moves away from Miss Mercy's confrontation with the dominant terms of the external present—the white nationalist conception of the citizen in the national public sphere—toward a speculative time warp of global Blackness.

Miller's Queer Black Nationalist Belonging

In his exploration of aesthetic radicalism in Black nationalism, Gershun Avilez defines disruptive inhabiting as a strategy of artists who convey investments in Black nationalist rhetoric while simultaneously questioning traditional conceptions of Black identity, particularly reinscriptions of normative gender and sexuality (Reference Avilez2016). Miller's citation of Nikki Giovanni, a Black feminist voice within the Black Arts Movement, simultaneously implicates her choreography in Black nationalist aesthetics and rhetoric while complicating one-dimensional notions of Black nationalist gender politics as masculinist. Moving beyond a binary framework of engagement versus rejection, Avilez describes disruptive inhabiting as a strategy of aesthetic incorporation linked to political reimagining: “It is a version of engaged critique that results in formal experimentation” (Reference Avilez2016, 12). In “Miss Me,” Miller's quotation and appropriation of Western concert dance forms results in formal experimentation. By putting ballet and Graham technique in relation to Black vernacular and pedestrian movement, juxtaposed with radical Black nationalist rhetoric advocating the beauty and power of Black womanhood, Miller repurposes concert dance traditions, retooling these inherited movement languages for her own rhetorical ends. One consequence of this formal experimentation was historical and generic illegibility, as her work was ambiguously positioned between “Black dance” and (white) postmodern dance.Footnote 35

In his discussion of Miller, Carl Paris notes that “she was one of the first African Americans to combine explicit references to race, gender and social conflict with postmodern aesthetics derived from the Judson Church” (2001, 237). He elaborates on her queer sense of belonging as an affirmation that exceeded normative genre distinctions: “She was doing [dance] within the context that still affirmed who she was.… She would not have fit with sort of the mainstream postmodern ethos—because she was too black and too woman and too outspoken about both. And then she wouldn't really fit with traditional perspectives around black dance because the work was too satirist and postmodern. During that time on the black side if you weren't toeing the nationalistic line, you didn't get no props” (Paris quoted in Amin Reference Amin. Takiyah2011, 129).

Miller's choreographic work simultaneously conveys an obscured radical feminist sensibility within Black nationalism and a tradition of Black radicalism in concert dance. She reflects on this dynamic: “If I was part of the mainstream Black Aesthetic, I would have had more gigs.… I wasn't asked because … I addressed none of [our pool of subjects] in a way that you knew this was a slave ship and we were all rowing. I realized it was because I was so oddball that I didn't fit into any of the—It didn't [clapping hands] do that you know?” (Amin Reference Amin. Takiyah2011, 127). In “Miss Me,” she choreographs an affirmative context for her distinct articulation of personhood by juxtaposing diverse approaches to movement to create a construct of queer, Black feminist, African diasporic belonging. Miller's former student Abdel Salaam remembers that

she destroyed everything that I thought was supposed to be proper. She just dismantled it. She deconstructed it. And that's what Joan was. That's why sometimes I say that she was either a postmodernist or a modern dance deconstructionist, before we even started using those terms, and probably avant-garde is an even better term. She was ahead of her time, which is probably why she never rose to the height she could've risen to. She was making socio-political statements on society and marriage and gender exploration … before people even had defined it as such. (2017)

Marriage, as the culmination of properly gendered performance in national structures, was among the institutions that Miller refused to desire. She subjected this legal structure of national belonging to her critical choreographic lens in a solo titled Homestretch.

Homestretch: “Reading” Gender Pedagogy & Refusing Marriage

In 1973, Miller created Homestretch as a follow-up to Pass Fe White. In the solo, Miller performs a satirical “read” of education into normative gender roles and marriage—the “proper” placement for women in the nation's hierarchies of citizenship and objecthood. Salaam describes this solo as “the next level of Pass Fe White … it was a commentary, to a certain degree an attack on predefined or predetermined gender roles: what a woman should do, what the arc of a woman's life should be based upon societal norms and guidance. Marriage, of course, being one of those things” (2017; original emphasis). There are very few archival remnants of Homestretch, but among them are these two reviews:

No doubt about Joan Miller's “Homestretch”—a Women's Lib piece for sure. Out stride three women, in bridal dress, graduation cap and gown and ratty bathrobe. While Sawako Yoshida runs in circles, Wanda Ward reads, “See Dick run. Dick runs a lot. Jane watches Dick run.” Ward does a whole masculine number, from cool pop dances to Mr. America muscle flexing. Rapid-fire slides of a bikini-clad woman, Virginia Slims ad and Superman and snatches of the song “I'm Your Puppet.” (Stodolsky Reference Stodolsky1973)

In another sequence, Yon Martin performs for Jane Lombardi, shouting “See Dick run. Dick runs fast. See big Dick … See Jane run. Jane runs …” Except Jane isn't running. She's sitting looking bored and frustrated. He coaxes her, performs a display of energetic masculine leaps and bounds across the stage: “See Dick run and jump and fly.” Finally, Lombardi puts on a blond wig [and says]: “I'm Barbara. Fly me.” (Jowitt Reference Jowitt1974)Footnote 36

In Homestretch, Miller cites and “reads” the essentialized, gendered worldview imparted through the Dick and Jane books in national educational curricula. Her satirical sensibility is evident in her misquotations, Signifyin’ on the uneven distribution of embodied agency transmitted through this education: “Jane watches Dick run.… See big Dick.” Her misquotation of conventional gendered embodiment—the “masculine number” performed on a woman's body—denaturalizes quotidian gender performance, while the multimedia juxtaposition of slides and music comment on objectified images of women as puppets.

The line, “I'm Barbara. Fly me,” accompanied by the blonde wig, is a choreographic intertext referencing a 1971 National Airlines ad campaign. The ads interchanged various white female stewardesses with the tagline, “I'm ____. Fly me.” The airline emblazoned the women's names onto the planes and forced flight attendants to wear buttons onboard that said, “Fly Me.”Footnote 37 This National Airlines commercial reflects the national, capitalist space of fantasy consumption, in which desire is condensed into the corporeality of white female sexual objects (Berlant Reference Berlant and Robbins1993). The status quo that Miller critiqued in her work included naturalized racial, gender, and sexual violence—the commonsense objectification of women in rape culture as part of a patriarchal social order.

Finally, the solo takes on women's “proper” placement in the nation through marriage. Historically, for women, the institution of marriage has offered proximity to the agency of the abstract national citizen. Berlant notes, “The way women have usually tried [miming the prophylaxis of citizenship] is heterosexual, but marriage turns out to embody and violate the woman more than it is worth” (Reference Berlant and Robbins1993, 200). Miller's critique of marriage in Homestretch also references her personal history: “She had a marriage that didn't work out” (Salaam Reference Salaam2017). The title Homestretch can simultaneously be read as the unworkable stretch to fit into domestic labor economies via the institutional form of marriage and as the final stretch of a race to the finish line of her own marriage.Footnote 38

Miller emerges in a white wedding dress, holding a bouquet. As she begins to move, the bouncing hemline of the dress reveals a pair of sneakers. Her casual, quotidian movements are remixed with “Millerisms,” such as a fist twisting into an opened mouth. She strips off the wedding dress, tossing the flowers and the dress aside. Clothed in a nude leotard, she chooses differently. Miller's queer desires extended beyond commonsense expectations of what might constitute a livable life for a woman.

Steaming Along on Her Own Track: Performing the Capacity to Desire DifferentlyFootnote 39

In closing, I want to dwell on a set of quotidian choreographic images from Miller's performances of everyday life. This queer archival fragment comes to me through Salaam's memory, rather than from evidence found in the archive of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Its traces are also archived in her choreography, residing in Homestretch's refusals of prescriptions for the form that women's desires should take.Footnote 40 Salaam reminisces, “She wasn't standing on a soapbox saying, ‘I'm gay, I'm gay, I'm gay.’ But she drove a truck. She and Gwen would walk down the street holding hands and smooch and kiss and cuddle in public and stuff like that. And this was back in the fucking ’60s and ’70s. So, there were some people who set precedents” (Reference Salaam2013). Thinking of Miller driving around in her truck conjures a scandalous performance of gender nonconformity in the 1960s and 1970s. She lived her queer desires by eschewing the proper gender roles satirically deconstructed in Homestretch. Miller did not broadcast a sexual identity in language—effectively confining her personhood to a label in a national context in which Black women's gender and sexuality is already subject to hypervisibility, discursively overexposed and overdetermined.Footnote 41 Instead, she conveyed her desires through embodied action.

Photo 3. Joan Miller. Photographer unknown. Courtesy Martial Roumain and Sheila Kaminsky.

Gwendolyn Watson was the original cellist in Pass Fe White, and she improvised the music for Miller's dance classes at Lehman College. She's also a white woman. In 1973, they hosted a conference whose theme, riffing on race and interdisciplinary collaborations, was titled “Music and Dance or ‘Integration is a Bitch’” (Amin Reference Amin. Takiyah2011, 83). In their artistic collaborations and everyday performances of tenderness, Joan and Gwen enacted an excess of women's “proper” racial, gender, and sexual placements in national structures. The image of their affectionate exchanges occurred in the wake of the legal prohibition of interracial marriage and sex. Miller rejected the commonsense logic of desire inherited from the legal structures of the nation: “same” race, “opposite” gender.Footnote 42 Their queer quotidian choreographies, a Black woman and a white woman exchanging caring gestures of intimacy in public, involves the intentional proximity of bodies in particular socially coded gestures. “It is the proximity of these bodies that produces a queer effect … proximity between those who are supposed to live on parallel lines, as points that should not meet” (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2007, 169; original emphasis).Footnote 43 The choreographic act of Black and white women reaching across national, gendered color lines, determined by histories of property, clears a path by improvising ways of being human together through difference.

Miller's satirical use of diaspora citation critiqued desires for normative subjectivity—the desire to occupy the position of the abstract citizen conceived through the Eurocentric notion of the “human” as white, bourgeois Western Man. The image from the beginning of this article, her satirical choreography for Chuck Davis, “reads” the figure of the patriotic citizen—who belongs to a nation that has yet to live up to its ideal of freedom—as an insufficient mode for belonging in the world. In the wake of slavery, in the afterlife of property, Christina Sharpe observes that “if we are lucky, we live in the knowledge that the wake has positioned us as no-citizen. If we are lucky, the knowledge of this positioning avails us to particular ways of re/seeing, re/inhabiting, and re/imagining the world” (Reference Sharpe2017, 22). Miller lived in this knowledge, repurposing inherited movement languages in the service of reimagining the world. Her choreographic imagination extended into a future beyond the reproduction of accepted thought, manifesting that future in the historical present of her Black avant-garde performances and offering a usable past for the present moment.