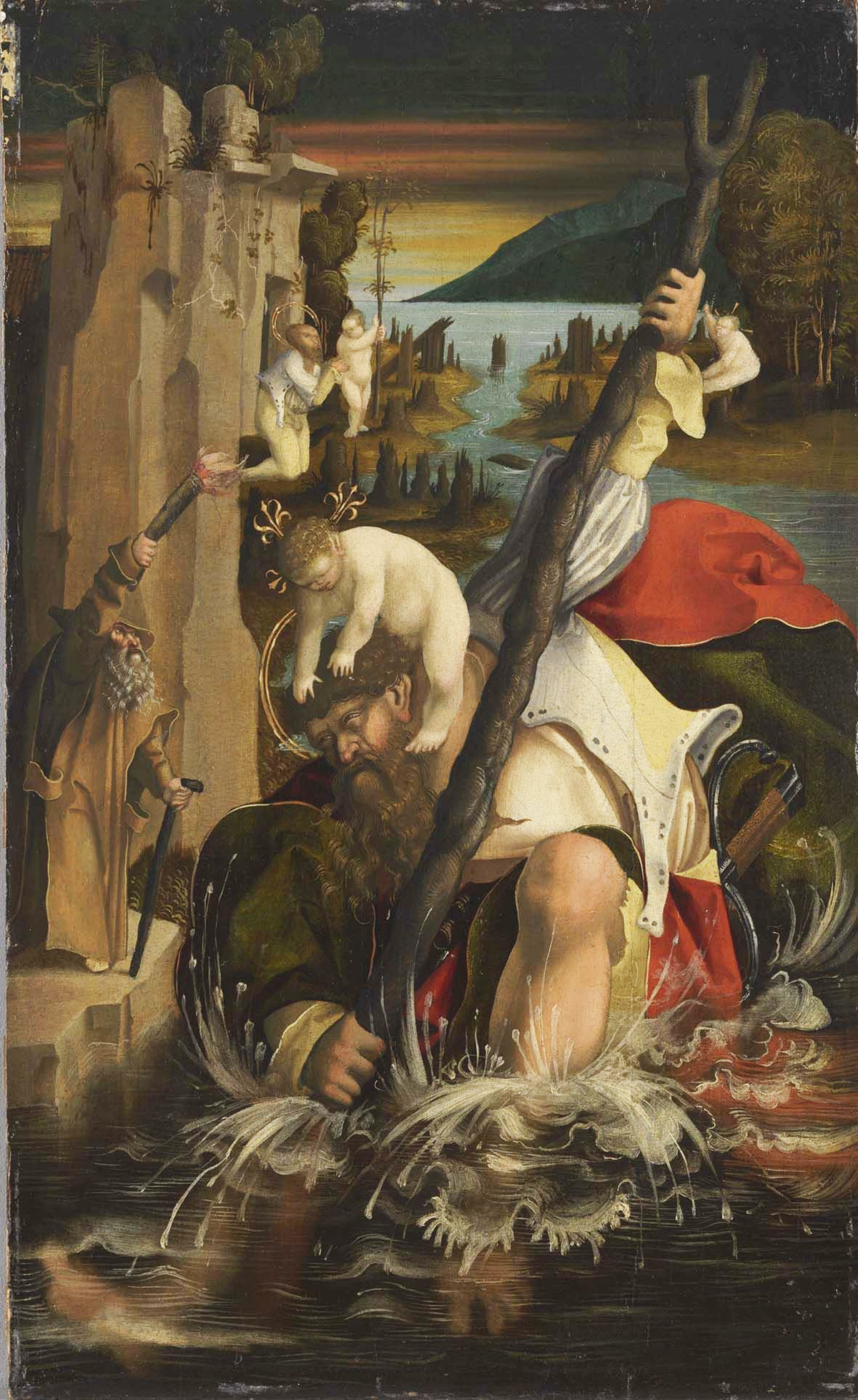

Visitors to the Fitzwilliam Museum’s collection of early Spanish and Flemish Art will come face to face with a painting of modest size and brilliant colours that blends so well into its surroundings that anyone might be forgiven for assuming it has always been there. Yet St Christopher Meeting the Devil is in fact a very recent addition, having been presented to the Fitzwilliam Museum on the two hundredth anniversary of its foundation in 2016 by the Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Charitable Trust in memory of Karl von Motesiczky, who died in Auschwitz (see Figure 1).Footnote 1 Before finding a new home in Cambridge, the painting had survived a dangerous journey through various countries: forcefully separated from its owner, it had fallen victim to the largest-scale and most brutal art theft in history – the National Socialist looting of art across Europe in the 1940s. Yet, in contrast to the various cases currently occupying the media that still await resolution and restitution, the fate of St Christopher Meeting the Devil was decided swiftly and justly soon after the end of World War II. The painting’s history, reconstructed here using the archival material available, involves some of the art world’s major players and shows in an exemplary way how the looting system functioned and what steps the Allied Forces undertook to rectify the crimes they uncovered.

Figure 1. The Master of St Christopher, sixteenth century. St Christopher Meeting the Devil. Oil on panel, 60.5 x 37 cm. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Photo: © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Loss

St Christopher Meeting the Devil, painted by an anonymous artist in the early sixteenth century and today attributed to the Master of St Christopher, shows a rarely depicted scene from the saint’s early life. On his quest to find the most powerful ruler on the earth, the young heathen, of extraordinary size and strength, has left the king of Canaan’s service and now encounters his new master. Christopher, enveloped by his billowing cloak, a double halo already suggesting his future, towers over the diminutive Devil on horseback, whose dark, rat-like features remain half-hidden under a makeshift headgear. The Devil’s armed, monstrous entourage trails behind him in a mountainous landscape.

In the 1930s, the painting was known as Ritter und Teufel (Knight and Devil) and belonged to the Viennese aristocrat Henriette von Motesiczky (born in 1882).Footnote 2 She hailed from a wealthy Jewish family that played a vital role in the Austrian capital’s intellectual and artistic circles, counting, for example, a generous donor to the Kunsthistorisches Museum among its members. Henriette had inherited the painting from her parents Leopold von Lieben, director of his own family bank and president of the Austrian Stock Exchange, and Anna von Lieben (née Todesco), one of Sigmund Freud’s earliest and most important patients. It had since become “one of the most treasured mementoes” of her childhood home on the Ringstrasse and hung in her daughter’s living room in the family’s apartment on Brahmsplatz.Footnote 3 Widowed in 1909, Henriette had been left with two children, her daughter Marie-Louise (born in 1906), who became a painter and, after studying abroad, settled in Vienna,Footnote 4 and her son Karl (born in 1904), whose life in the 1930s was determined by the psychoanalyst and communist Wilhelm Reich.Footnote 5 Having met Reich in Berlin, he fell under his spell and, in April 1933, followed him into exile, first in Denmark and then in Norway. It was only in the summer of 1937 that Karl, by now disillusioned with his former mentor, rejoined his family to study medicine at the University of Vienna. The National Socialist annexation of Austria on 12 March 1938 caught the recently reunited family by surprise. Panic-stricken, Henriette and Marie-Louise left their homeland the following day, heading for refuge with relatives in the Netherlands. Karl decided to stay on as a deliberate act of resistance and to save the large family estate in the village of Hinterbrühl in the Wienerwald from falling into the hands of the Nazis. He immediately set about organizing the shipping of his mother’s and sister’s possessions, starting with Marie-Louise’s artistic oeuvre. His request for an export licence, dated 8 May 1938, was granted at no charge by the Zentralstelle für Denkmalschutz (Central Office for Monument Conservation), formerly known as the Bundesdenkmalamt (Federal Monuments Office), which, based on the Denkmalschutzgesetz (Monument Protection Act) of 1923, decided if artworks were of national importance and therefore subject to an export ban. In total, “98 oil paintings, sketches, pastel sketches,” many of which have survived and are all that is left of his sister’s early work, departed from Vienna by train on 14 May 1938.Footnote 6

Four months later, with the prospect of an immediate return of his mother and sister diminishing by the day, Karl began arranging a second transport, this time comprising a substantial proportion of the contents of the Viennese apartment. Almost all the items, including furniture, carpets, porcelain, cutlery, linen, mirrors, tapestries, and artworks, passed the recently “gleichgeschaltet” (synchronized) Zentralstelle für Denkmalschutz’s muster.Footnote 7 Only one item was prohibited from leaving the country: “oil painting on wood saint on foot and devil on horseback with landscape. German c. 1510.”Footnote 8 As the future course of events shows, the art historical importance of the painting, which Karl had simply referred to as “altdeutsch” (old German),Footnote 9 must have been recognized by the assessors of the Zentralstelle für Denkmalschutz, who had also dated it. Karl broached the mixed news to Henriette at the beginning of October. Full of relief and hope after the Munich Agreement had just averted the imminent danger of war, he emphasized that a confiscation of the apartment was now off the table and suggested the following action plan regarding the painting: “If necessary I will ask you to transfer it to me. I have the impression they would love to have it for the museum, yet I think it can be saved for the general public in other ways, for example through a solemn declaration on my part not to take it out of the country or through making it available for loans.”Footnote 10

While the items released for shipping awaited valuation, Ritter und Teufel was deposited at the Kunsthistorisches Museum where it underwent further examination. By the time it left the museum, it was attributed to the “circle of Jörg Breu,” member of the famous group of artists known as the Danube School, which operated in Bavaria and Austria in the early sixteenth century, and the scene depicted identified as part of the legend of St Christopher.Footnote 11 Among the museum’s experts examining it would have been Ludwig von Baldass (1887–1963), a renowned art historian specializing in early Netherlandish and Gothic art.Footnote 12 Curator at the picture gallery of the Kunsthistorisches Museum since 1912 and lecturer at the University of Vienna since 1926, he had recently received an honorary professorship. A few days after the Anschluss, he had been appointed temporary director of the picture gallery of the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

As a long-standing friend of the Motesiczky family – his wife Pauly had been the young Marie-Louise’s governess – he already knew the painting well. Baldass had a special interest in the German painter Albrecht Altdorfer, the main representative of the Danube School, on whom he had published a monograph in 1923. During the last few months, he had used the rare opportunity to extensively study the master’s works in the exhibition Albrecht Altdorfer und sein Kreis at the Staatsgalerie in Munich, which commemorated the four hundredth anniversary of the painter’s death. Organized only one year after the Bavarian capital had experienced the confrontational staging of official National Socialist art in the first Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung with defamed art in the exhibition Entartete Kunst, the Altdorfer exhibition reinforced the reactionary artistic policy of the Third Reich and confirmed the ideological baggage that art was to carry. Alluding to the Anschluss, Ernst Buchner (1892–1962), the director general of the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen (Bavarian State Painting Collections) and curator of the exhibition, praised the show for “proving the inner togetherness and cultural unity of the old Bavarian Ostmark [Austria]” on whose central river Inn Braunau, the birthplace of Adolf Hitler, was situated, as he obsequiously put it.Footnote 13

Exhibit no. 638 was a work by an unknown master, “active c. 1500–1510 probably in the Austrian-Danubian foothills of the Alps,” called Szenen aus der Christophoruslegende (Scenes from the Legend of St Christopher) (see Figure 2). The Alte Pinakothek in Munich had recently acquired the “highly original” linden wood panel, which “due to its extraordinary charm” attracted a lot of attention, from a private collection in Linz.Footnote 14 For Buchner, who had been intent on acquiring it for years, it belonged to the “most important and striking works of the earlier Danube School.”Footnote 15 Buchner identified it as the sawn-off outer panel of a wing of an altarpiece whose verso showed the ascension of Mary Magdalen. Another panel in an American collection, according to Buchner, depicted a further scene from the saint’s life, and he therefore labeled the so far unidentified artist Meister der Maria Magdalena (Master of Mary Magdalen).Footnote 16 Szenen aus der Christophoruslegende would soon play a major role in the future of the Motesiczkys’ painting.

Figure 2. The Master of St Christopher with the Devil. St Christopher, c. 1515. Oil on wood, 60.4 x 37 cm. Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich.

© Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen München; Foto: Sibylle Forster.

Karl, in the meantime, had carried out his plan and, on 3 October, paid the Zentralstelle für Denkmalschutz a visit. His fear of “not standing much of a chance with the Denkmalamt apparently very interested in purchasing”Footnote 17 the painting was not unfounded since the government office was by now a firm part of the National Socialist expropriation of Austrian Jews.Footnote 18 Rather surprisingly, however, Karl’s mission was successful. He was seen by the curator Otto Demus (1902–90), who would soon emigrate to England, finding employment at the Warburg Institute in London.Footnote 19 Karl declared that the painting, which he now claimed belonged to his sister, would, if returned, stay in Vienna in his care and would be available for temporary loans.Footnote 20 Demus honored Karl’s pledge and gave him permission to collect the painting at the Kunsthistorisches Museum. In early November, Karl retrieved it, taking it back to his own flat at Operngasse 25.Footnote 21

From now on, Karl spent most of his time in Hinterbrühl. On weekends, his anti-fascist and Jewish friends would meet in the relative safety of the remote estate, some finding shelter there for several months. His opposition to the regime intensifying, he founded a resistance group with friends after the beginning of World War II. When, in the summer of 1942, they helped two Jewish couples from Poland escape to Switzerland, the group was denounced. Karl and his co-conspirators Ella Lingens and Aladar Döry were arrested by the Gestapo on 13 October 1942. Karl and Lingens were sent to Auschwitz four months later. He died in the camp’s prisoners’ infirmary of typhus on 25 June 1943.Footnote 22

No contemporary documents have yet been found that explain exactly what happened to Karl’s assets after his arrest. Enquiries in 1948 and 1951 concluded that the Gestapo had initially intended to confiscate his possessions, later on declaring the Reichsstatthalter’s office (Reich Governor), one of the chief agencies in the Aryanization of Jewish property, responsible.Footnote 23 For unknown reasons, however, the expropriation was not carried out fully. Karl’s bank account was confiscated and henceforth administered by the lawyer Friedrich Zabransky, while his “gegenständl. Vermögen” (moveable assets) seem to have stayed untouched.Footnote 24 It is therefore not possible to reconstruct the fate of the painting until it resurfaced in October 1943 at the Viennese auction house Dorotheum, a crucial accomplice in the National Socialist art looting machinery, responsible for the disposal of a large proportion of Jewish property. The painting had been submitted by a certain Albert Pfneisel (or Pfneisl), listed in address books of the time as resident of Porzellangasse 33a in the ninth district of Vienna, his profession given as “Zeitgsbeamt.” (newspaper clerk/functionary).

Pfneisel had in fact been the owner of a series of leftwing Austrian newspapers, which distinguished themselves less through informative content than ideological agitation. The latest publication, Der Neue Mahnruf, produced by order of the Kommunistische Opposition Österreich (Communist Opposition Austria), had been discontinued after the February 1934 issue.Footnote 25 Karl and Pfneisel, considering their similar political views, might have been acquainted, and it is conceivable that Pfneisel had been entrusted by Karl to look after the painting on his behalf. In any case, according to Henriette’s postwar enquiries, the painting was put up for auction on 27 July 1943, more than a month after Karl’s death.Footnote 26 Albert Pfneisel’s trail vanishes soon after the auction. He had not been seen at his address for five years when the Dorotheum attempted to trace him in 1949,Footnote 27 and the authorities could not explain how he had come to be in possession of the painting.Footnote 28

Now that the painting was in the public domain, the expertise that Ludwig von Baldass had gathered in Munich in 1938 – resulting in a richly illustrated monograph on Altdorfer in 1941 that saw its revised edition in 1943Footnote 29 – and the professional network he had established over the years were crucial in determining its fate. When Baldass, having returned to his original role as curator at the museum in late 1939, spotted Karl’s painting in Lot no. 99, advertised as Die Versuchung eines Heiligen (The Temptation of a Saint), c. 1510, by a painter of the Danube School, at the Dorotheum’s upcoming 485. Kunstauktion, scheduled for 19–22 October 1943, he informed Ernst Buchner.Footnote 30 Both men knew that it had been identified as the companion piece to Szenen aus der Christophoruslegende, belonging to the same altarpiece.Footnote 31 The identification as a pair was immediately convincing since the passage of time was neatly indicated by the tremendous beard the saint had grown since leaving the Devil’s services.Footnote 32 Eager to purchase the painting, Buchner persuaded the Bavarian State Ministry for Education and Culture to grant him permission for the acquisition by his museum.Footnote 33 The money was found in a special fund administered by the Ministry of Finance.Footnote 34

To execute the purchase, the services of the Viennese art dealer Otto Schatzker (1885–1959) were employed.Footnote 35 Now in high demand, Schatzker had been down on his luck only a short while ago. In 1938, unable to prove an Aryan ancestry, he had been forced to close his business. He had, however, carried on dealing clandestinely, acting as mediator for dealers and museums in Austria and abroad, among them the Führermuseum in Linz, and not shying away from purchasing from Jews forced to flee the country. How he managed to be reinstated in his profession again in August 1941 is unclear, but his good relations with various Nazi officials probably played a part. Schatzker was rumored to have helped Adolf Hitler sell some of his drawings during his years in Vienna before World War I and later attempted to stay in the Führer’s good books through gifts. Ludwig von Baldass had already acquired several paintings through Schatzker for the Kunsthistorisches Museum and received regular tip-offs for artworks coming up at auction from him. Schatzker’s business now flourished, and he prided himself on being able to “obtain objects quickly where others might have tried for years and in vain.”Footnote 36

The purchase was processed smoothly for the envisaged price of 14,300 Reichsmark – a relatively high figure in comparison to the 12,500 Reichsmark spent on its companion piece in 1938Footnote 37 when, however, the art market had experienced a major slump caused by the large number of Austrian Jews fleeing the country, leaving behind their property – and the painting was promptly dispatched to Munich. On 26 November 1943, Ernst Buchner reported the safe arrival of the “exquisite” panel, which he had renamed Der hl. Christophorus und der Teufel (St Christopher and the Devil), to Baldass. It fulfilled all his expectations of being a “worthy complement” to “the holy giant splashing through the water.”Footnote 38 Displaying the painting in its new location, the Alte Pinakothek, however, was not feasible. Air raids in March 1943 had damaged the exterior of the building, now closed to the public, and the museum’s collection had begun to be evacuated. For the moment, the new arrival received another variation on its title, Versuchung des Hl. Christopherus, an inventory number, 10871, and was placed in the basement of the Alte Pinakothek.Footnote 39 In anticipation of worse air raids to come, it was moved to the basement of the nearby Neue Pinakothek on 29 March 1944 and, after heavy damage to both buildings in April, together with approximately 1,000 other paintings, relocated to Schloss Höglwörth in rural Upper Bavaria in June 1944.Footnote 40 The former monastery was one of nine sites that the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen used as part of a large-scale salvage operation that started with the most precious objects and was scaled up as the threat from air raids grew.Footnote 41 There it stayed until the collapse of the Third Reich.

Restitution

At the end of World War II, the US military government assumed responsibility for all salvaged goods in its sector. For a start, the repositories were closed off, and all museum property temporarily confiscated. Quickly realizing the enormity of the challenge they were facing, the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Section (MFA&A) of the US military government established the Central Collecting Point in Munich in June 1945. Its remit was to gather, check, and return to their rightful owners all artworks retrieved, beginning with those obviously looted and the collections of party leaders, followed by museum property. This was a mammoth task involving hundreds of thousands of objects. By the autumn of 1945, the first restitutions took place, and, over the next few years, the vast majority of objects, with the exception of only a few thousand, were returned.Footnote 42

In a city devastated by bomb damage, the former party buildings of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei at the Königsplatz had escaped the aerial attacks more or less intact. With some hasty repairs, the “Führerbau,” which was the setting of the Munich Agreement in September 1938, and the “Verwaltungsbau,” the administrative building of the party, began to receive artworks that arrived in a steady flow of lorries. From 5 December 1945 to the end of 1946, the roughly 12,000 artworks belonging to the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen returned to Munich safely – no losses were suffered and no damage was recorded.Footnote 43 On 18 April 1946, St Christopher Meeting the Devil reached the Central Collecting Point where, under its “Munich number” 24808, bestowed in order of arrival, it was recorded as Temptation of a Saint by the Meister der Maria Magdalena.Footnote 44 Since the Alte Pinakothek had suffered direct hits by explosive bombs on 17 December 1944 and would only reopen to the public after a lengthy reconstruction in 1957, the painting was to spend the next few years in a storeroom. In the meantime, MFA&A experts identified it as auctioned by the Dorotheum and made enquiries about its former ownership.Footnote 45

After World War II, the remaining members of the Motesiczky family were still trying to come to terms with the loss of Karl. Henriette and Marie-Louise had emigrated to England in early 1939, first living in London and settling in Amersham, Buckinghamshire, just outside the British capital the following year. News of Karl’s death had reached them via a relative in Switzerland in October 1943. Marie-Louise would later claim that he died just a few weeks before the end of the war, making his loss even more futile as it could almost have been avoided. For the rest of her life, she felt guilty for not having been able to save Karl.Footnote 46 In 1946, Marie-Louise paid the first visit to her hometown after her hurried escape. She would return regularly, often staying with Ludwig von Baldass in his family’s apartment at the museum. Shortly after the end of the war, Baldass had again become the director of the picture gallery of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, briefly advancing to the museum’s director in 1948 before retiring in 1949. Motesiczky, naturalized as a British citizen in 1948, chose to remain in England and set about reclaiming the family’s Austrian property. All she could find of Karl’s assets was the confiscated bank account that also contained various deposits from the war years.Footnote 47 The 6,879 Schilling left in it were eventually passed on to Henriette and Marie-Louise.Footnote 48 Together with the rest of his belongings, Karl’s Stradivarius cello, which he had asked friends to send on to Auschwitz, had vanished without a trace.

In contrast, St Christopher Meeting the Devil’s recent journey was known, and it was Ludwig von Baldass who informed the Motesiczkys about it. Unfortunately, the deadline of 31 December 1948 for filing formal claims for restitution with the Central Filing Agency at Bad Nauheim in accordance with the terms of the Military Government Law no. 59 of November 1947 had already passed. Henriette therefore took matters into her own hands, first, with the help of her Munich-based niece Louise Rupé, confirming the painting’s current whereabouts and then, in a letter to the MFA&A Section of the US military government in Munich, dated 14 May 1949, filing a claim for its restitution.Footnote 49 When, by September 1949, she had not had a reply, she explored another route. She repeated her claim, this time addressing it to the Central Collecting Point in Wiesbaden, which had initially specialized in the return of artworks belonging to the Berlin museums, having learned that “all looted but so far not yet restituted pictures have now been transferred” there.Footnote 50 Doubtful about her chances of success, however, Henriette, backed up by Ludwig von Baldass, tried a third approach and also asked the Bundesdenkmalamt in Vienna, the former Zentralstelle für Denkmalschutz, now responsible for research into looted art and its reclamation, to put in a claim for the painting’s restitution to her home country.Footnote 51 Otto Demus, back in Austria since 1946 and now the Bundesdenkmalamt’s director, agreed and did so immediately, arguing that they were dealing with “an especially valuable painting … which had not been submitted to auction by the owner himself and which would never have received an export permit from the Austrian authorities.”Footnote 52

Yet, unbeknown to Henriette, her original claim had already been successful. The new director general of the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Eberhard Hanfstaengl, former director of the Nationalgalerie in Berlin until his dismissal in 1937 due to his support for “degenerate” art, had reacted swiftly. By the end of June 1949, he had informed Stefan Munsing, the director of the Central Collecting Point in Munich, that he wanted the Motesiczkys’ painting given back to the family. Although he was aware that the painting was subject to the submission of proof of confiscation, he was prepared to make an exception: “In view of the fact, however, that Herr Karl Motesiczky died in a Concentration Camp I feel inclined to return it to you for the purpose of restitution without further investigation.”Footnote 53 A list of Jewish claims at the Central Collecting Point in Munich, compiled a few days earlier, marks Henriette’s case as decided in her favor.Footnote 54 The painting was among the tenth load of “Jewish identified property” to be transferred to Wiesbaden for restitutionFootnote 55 and dispatched on 30 July 1949.Footnote 56

On this basis, the Central Collecting Point Wiesbaden informed Henriette on 5 January 1950 that the release of the painting had been granted despite her not “having filed a formal claim with the Central Filing Agency” by the end of 1948. The case could, “under these special circumstances,” be disposed of “without further formalities,” thus avoiding “the necessity of extended and complicated court procedures.”Footnote 57 Transport to England finally organized,Footnote 58 the Motesiczkys’ painting left Wiesbaden on 17 May 1950.Footnote 59

Around the same time, Otto Demus was informed that the painting already had a claim by Henriette von Motesiczky against it.Footnote 60 Mistaking this for a sign that the painting would soon be back in Austria,Footnote 61 his hope was dashed when he learnt that due to an “amicable settlement” between the director of the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen and Karl’s heirs it had already been dispatched to England.Footnote 62 Following Henriette’s announcement that the painting was soon expected to arrive in Amersham,Footnote 63 the Bundesdenkmalamt annulled its claim, informed the Baldass family of the development and filed the case.Footnote 64

In 1948, St Christopher Meeting the Devil had received its final attribution to the Meister des Christophorus mit dem Teufel (Master of St Christopher with the Devil) by Ernst Buchner. Doubting his earlier linkage between the two Mary Magdalen panels, which had been the basis for the initial attribution, the by now acknowledged pairing of the two panels showing St Christopher proved to be more plausible.Footnote 65 The painting found its new home in Amersham until it was relocated to Hampstead in northwest London where the Motesiczkys moved in 1960. When Henriette died in 1978, it passed on to Marie-Louise, upon whose death in 1996 it fell to the Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Charitable Trust, founded in 1992 to preserve her artistic legacy. On loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum since 2002, it became permanently integrated into the collection in 2016.

Justice?

St Christopher Meeting the Devil survived the Third Reich and now publicly bears witness to the fact that art looted by the National Socialists can be found all over the world. An example of the first wave of restitutions immediately after the war, its history shows that, within the existing structures, informal networks could be decisive and help influence the outcome of claims in favor of the victims in the spirit of Wiedergutmachung. It also highlights the continuous and ambiguous role of some of the actors, such as Ludwig von Baldass, involved in both the looting and the restitution of the painting. Besides, gaps in the knowledge of the painting’s history, due to a lack of documentary evidence, demonstrate the challenges still encountered today in the attempt to reconstruct cases of expropriation and to reach fair solutions.

In contrast to St Christopher Meeting the Devil, Karl von Motesiczky, who bravely fought not only for the safety of the painting but also risked his own life saving others, perished under the National Socialist regime. Although initially optimistic about his country’s future even after the Anschluss, he had remained fatalistic concerning his own: “Whatever will be, will be and I won’t attempt in any way to elude the fate of many millions and to get special treatment … Right or wrong, my country.”Footnote 66 His courage is publicly acknowledged on the memorial stone erected in the grounds of the family estate at Hinterbrühl, now an SOS-Kinderdorf, in 1961. Its inscription reads: “Für die selbstlose Hilfe, die er schuldlos Verfolgten gewährte, erlitt er den Tod” (He perished for the selfless help he granted to the innocently persecuted). Recognized by the state of Israel as a “Righteous among the Nations” in 1980, Karl is honored on the Mount of Remembrance at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. Yet a sketchy drawing by his sister probably provides the most touching commemoration: it shows Karl von Motesiczky as St Christopher, holding a staff and carrying a child on his back – a saintly savior of art and lives (see Figure 3).Footnote 67

Figure 3. Marie-Louise von Motesiczky. Karl as St Christopher, undated. Charcoal and pastel on paper, 28 x 42.5 cm. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Image: Courtesy of the Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Charitable Trust.

© Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Charitable Trust 2021.

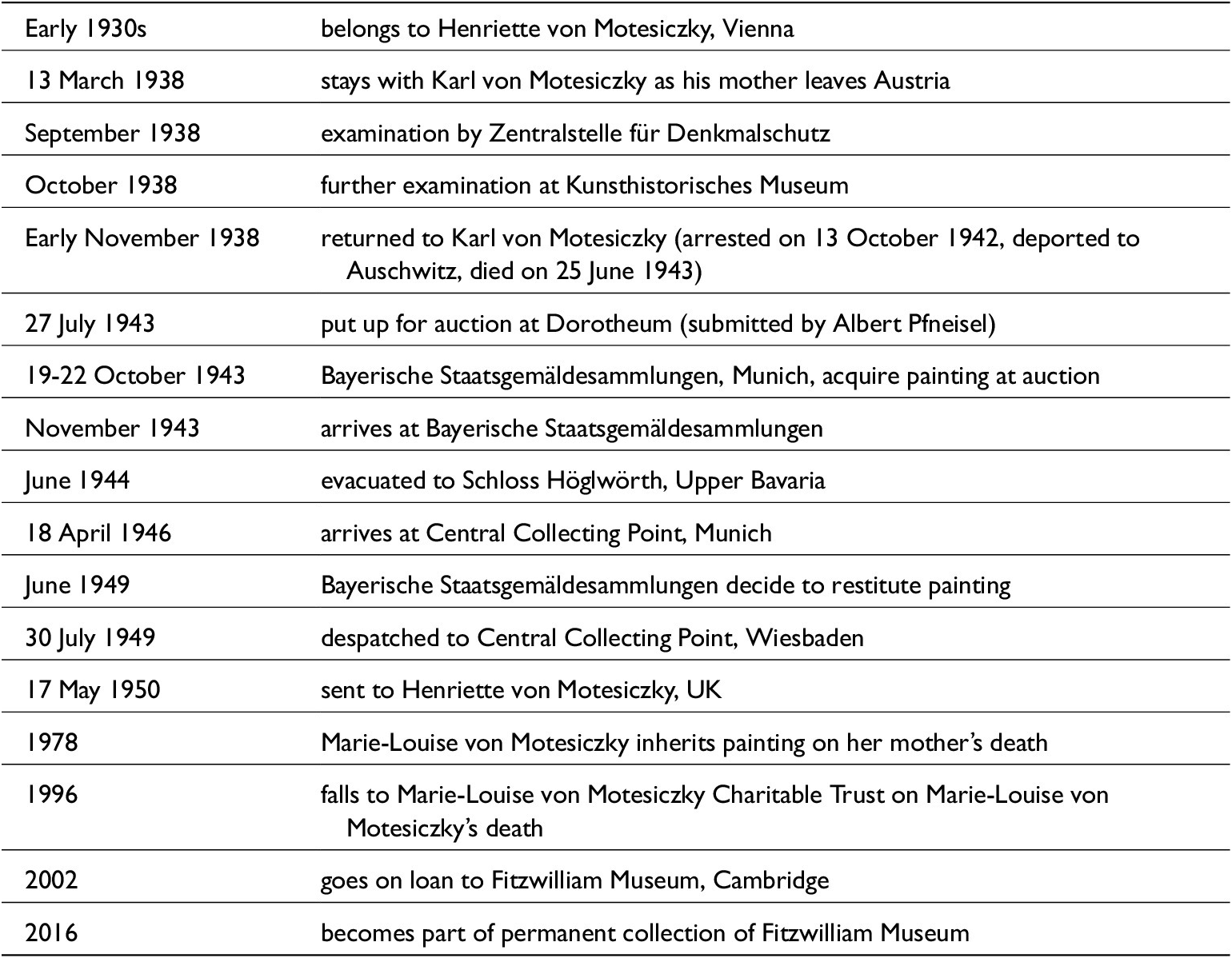

St Christopher Meeting the Devil: Chronology

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank the Trustees of the Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Charitable Trust for the financial support that made the research for this article possible. I would also like to thank Susanne Hehenberger, Monika Löscher, Christiane Rothländer, Anneliese Schallmeiner, Martin Schawe, Pia Schölnberger, Ursula Schwarz, Anita Stelzl-Gallian, and Felicitas Thurn-Valsassina for generous assistance and advice.