One of the initial disappointments that comes with studying music connected to the court of Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia Rudolf II (1552–1612) is the realization that there was no such thing as a “Rudolfine” musical style. That a distinctive visual aesthetic was cultivated by the Habsburg ruler's painters and printmakers has been amply demonstrated by art historians Thomas DaCosta Kauffmann and Eliška Fučíková, among others.Footnote 1 Yet while we might productively think of such diverse artists as Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Bartolomäus Spranger, Josef Heintz the Elder, and Hans von Aachen as belonging to a Rudolfine “school,” the same cannot be said of the many musicians who made Rudolf II's court in Prague their home between 1583 and 1612.

There is no shortage of music connected to Rudolf II's chapelmaster, Philippe de Monte, his erudite organist, Carolus Luython, or any others of the dozen or so composing musicians employed in the imperial music chapel. This music, which circulated both in print and in manuscript, ranges from weighty polyphonic settings of Latin liturgical and devotional texts (Masses and motets) to fashionable settings of serious Italian poetry (madrigals) to such light fare as the French chanson and German Lied—straightforward enough to be sung among friends around a table, partbooks in hand. It proves challenging, however, to isolate practices or compositional choices that might meaningfully be thought of as characteristic of a Rudolfine sound.Footnote 2

Some of the difficulty lies with the compositional rules that still constrained what was musically possible: rules whose violation, as we shall see, came with metaphysical consequences. But Rudolf II is also partly to blame. Famous for preferring the company of his painters and artisans to audiences with diplomats and courtiers, he does not seem to have harbored similar enthusiasms for his musicians. The growing body of scholarship on musical activities at his court and in Prague during his reign has only confirmed that the emperor's engagement with his musicians and with musical matters was at best perfunctory.Footnote 3 Put plainly, Rudolf employed musicians not because of any special love for music theory or practice but because it was expected of him.Footnote 4 Music performance was essential to court ceremonial and religious ritual, and by the sixteenth century a skilled ensemble of singers, along with an organist or two, was a customary component of a princely court. As symbols of a ruler's munificence and power, these members of the court music chapel, along with the mounted trumpeters and drummers employed in the royal stables, played an essential role in princely representation.Footnote 5

On acceding to the imperial throne in 1576, Rudolf was content to maintain what he had inherited in personnel and practice from his father Maximilian II (r. 1564–76).Footnote 6 Ensconced in Prague by 1583, he supplemented and replaced musicians as necessary to maintain a suitably impressive chapel, but without the intensity of purpose that accompanied his pursuit of artists. The notoriously unhappy dedications of the five-voice madrigal prints by Monte, issued in 1580 and 1581, do suggest the emperor on occasion weighed in on matters of musical style.Footnote 7 Still, he does not seem to have kept up with the learned discussions about ancient and modern music that were unfolding in Italy, nor to have been inclined to tell his composers what to write. To borrow a helpful distinction made by the Italian musicologist Claudio Annibaldi, Rudolf II's musical patronage was “institutional” or “conventional” rather than “humanistic,” contractually determined and reflecting widespread and generic associations between learned music and social elites rather than demonstrating his personal taste or connoisseurship.Footnote 8

Although Rudolf's apathy toward music might seem an odd way to open an article on musical encounters in Rudolfine Prague, it gives us a vantage point from which to scrutinize how other people connected to his court used music and found meaning in it. These people, learned but not necessarily wealthy, filled the spaces created by Rudolf II's absence, and found in music a means of understanding identity and difference both within their own ethnically and linguistically diverse city and in relation to their coreligionists in other parts of Europe. Broadening our view from the cosmopolitan court to take in the worlds to which the court gave access, we find robust networks of friendship and patronage and traces of far-flung contacts among diplomats, intellectuals, and musicians.Footnote 9 These ad hoc systems of support give us a sense of music's myriad uses in a gift economy that often bypassed the emperor altogether. They also help explain the incontrovertible fact that, despite the emperor's passivity, music thrived at his court and in Prague more generally during his reign. Indeed, even though Rudolf's musicians struggled to attract and sustain the attention of their melancholic employer, more compositions can be connected to his court than to those of his father and grandfather, or his successor, Matthias (r. 1612–19). In quality and quantity, the output of his composers holds up well even when compared with the splendidly musical courts of Emperors Ferdinand II (r. 1619–37) and Ferdinand III (r. 1637–57).Footnote 10

This article revolves around the musical hub that was Rudolfine Prague, using three figures to develop two basic points: that music—and ideas about music, and people who made music—traveled, and that because of this mobility, music was frequently a medium of cultural contact and encounter.Footnote 11 The Lutheran astronomer Johannes Kepler was troubled by what he heard in the cantillation of a Turkish visitor whose prayer he witnessed at the imperial court in Prague in 1608, and he used a venerable Latin plainchant to understand his discomfort. The musical adventurer Kryštof Harant of Polžice and Bezdružice set out from Prague to Venice and then to the Holy Land, making sense of his experiences through sound and song. The Flemish composer Monte, relocating from Vienna to Prague along with the rest of the imperial court, used music to comment on the plight of Catholics in a world gone heretical and sent his musical commentary across Europe to the recusant composer William Byrd—a favorite of Elizabeth I of England even as he skirted charges of sedition.

An Astronomer: Johannes Kepler, Prague 1609

There were plenty of people at the imperial court and in the city below who were interested in music's theoretical underpinnings and metaphysical workings, for all that such matters did not sustain the emperor's interests. The court painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526–93), for example, engaged in the branch of speculative thought (i.e., musica theorica) concerned with music's mathematical foundations. Arcimboldo's efforts to translate the superparticular ratios (2:1, 3:2, 4:3, and 9:8) associated with commonly used musical intervals (octaves, fifths, fourths, and whole tones) into precisely measured combinations of black and white are preserved in Il Figino overo del fine della pittura (The Figino, or on the purpose of painting; Mantua, 1591), by the Mantuan cleric and poet Gregorio Comanini (1550–1608).Footnote 12

Although more famous for its ekphrasis of Arcimboldo's 1591 portrait of Rudolf II as the Roman god Vertumnus, Comanini's treatise also describes in some detail the system Arcimboldo devised to represent music's fundamental proportions in a finely tuned gray-scale.Footnote 13 Explaining somewhat elliptically how these proportions might be applied to other colors to accommodate the overlapping ranges of a polyphonic composition, Comanini assures the reader that the imperial chamber musician Mauro Sinibaldi was able to “read” the different shades of Arcimboldo's colored cards and reproduce the corresponding musical intervals on a harpsichord.Footnote 14 For Comanini, Arcimboldo's experiments—their results proven empirically for having been tested by a practicing musician—served to make a larger point about the intellectual value of the visual arts: if colors could be shown to operate according to the same harmonious proportions that had governed musical consonances since Pythagoras's mythical discovery of the relation between sound and number in the din of a blacksmith's forge, painting might be worthy of the privileged place long accorded music among the liberal arts.Footnote 15

The same intellectual tradition (i.e., canonic theory, after kanōn, or monochord) that undergirded Arcimboldo's experiments and Comanini's apologia for painting informed the hearing and worldview of another nonspecialist with musical interests, the German astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571–1630).Footnote 16 A resident of Prague's Old Town while employed at the imperial court from 1600 to 1612, Kepler deployed his understanding of music's mathematical properties to very different ends. His understanding of the universe and its cosmic workings was fundamentally musical, as the title of his celebrated cosmological treatise Harmonices mundi (Harmonies of the world; Linz, 1619) suggests.Footnote 17 It is, moreover, shaped through and through not only by what he glimpsed in the heavens but also by what he saw and heard in the streets and squares and buildings around him. His treatise—a virtuosic reconciliation of his empirical observations of planetary motion with the venerable tradition of music as sounding number—bears the marks of his time in Prague; for all that he dedicated it to James I of England.

In other treatises on other matters, Kepler used local experiences to guide the reader into a given topic. In Strena, seu de nive sexangula (A New Year's gift, or the six-pointed snowflake; Frankfurt, 1611), for instance, he claims that snowflakes landing on his coat as he crossed Prague's Charles Bridge inspired his curiosity about why snowflakes always have six corners.Footnote 18 His little New Year's gift (strena) for the courtier and aulic counselor Johannes Matthaeus Wacker von Wackenfels (1550–1619) is a pathbreaking work on crystalline structure, and the Prague anecdote makes for an effective and picturesque opening. But his reference to the snowflake on his lapel does not have significant implications for his theory; nor does it reveal much about his thoughts on older theories or worldviews.

In contrast, a listening experience that Kepler recounts in the middle of the Harmonices mundi (Book III, chapter 13: “What Naturally Suitable and Tuneful Melody Is”) is at once evocative and explanatory.Footnote 19 He begins the chapter with his recollection of hearing the prayers of a member of an Ottoman delegation that visited Prague in 1609. He uses this account and his analysis of what he heard to deepen his justifications for assuming the divine origins of the mathematical proportions on which his cosmology rests. The anecdote both opens onto Kepler's larger theory of the geometric determination of the relationships among the planets, and updates a venerable tradition reaching back to the ancients, in which musical harmony (explained in arithmetic terms as a fundamentally rational property of sound) was aural evidence for a divine order that was invisible and unobservable, and to which humans were otherwise insensible.

The Ottoman embassy had arrived in Prague on 12 October 1609.Footnote 20 Sent by Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603–17) in the wake of the 1606 Peace of Zsitvatorok—the agreement that brought to an end a protracted war between the Ottoman and Holy Roman Empires (1593–1606)—the delegation stayed in Prague until 6 December, negotiating, hunting, eating, sleeping, and praying.Footnote 21 Details of their sojourn, from the formal greeting at the imperial frontier to the subsequent cautious and gift-laden rapprochement between representatives of the two recently warring empires, were reported to readers throughout the German-speaking lands in a short summary issued by the Augsburg printer and propagandist Wilhelm Peter Zimmermann.Footnote 22 Zimmermann's account, along with a series of engravings by the Bohemian engraver Samuel Suchuduller, gives some sense of what Prague's residents saw and heard when the delegation first arrived—details that Kepler does not provide.Footnote 23

The visiting dignitaries entered Prague in the company of Habsburg representatives and civic officials in a sumptuous procession whose progress was marked aurally by the sounds of not only local but also Ottoman musicians. Headed by a group of mounted trumpeters and drummers, three groups of riders representing Prague's constituent towns (Old Town, New Town, and the Small Side) led the way, each with its own standard-bearers and trumpeters. The Ottoman ambassador, probably Qāḍīzāde ʿAlī Paşa (d. 1616) from the Buda pashalik, took pride of place at the center of the procession, riding alongside the imperial equerry Adam of Waldstein and a “Herr von Fels”—probably Leonhard Colonna of Fels, one of the leaders of the Bohemian Estates’ forces (see Figure 1).Footnote 24 At some distance behind them, mounted drummers and trumpeters from the imperial stables heralded the presence of a group of Bohemian nobles (see Figure 2). Entering just behind them was a group of Turkish musicians on horseback, playing trumpets, shawms ("schalmain," i.e., zūrnā), and drums. Standard-bearers for the rival empires brought up the rear (see Figure 3).Footnote 25

Figure 1. Qāḍīzāde ʿAlī Paşa and Lords Adam von Waldstein and [Leonhard?] von Fels, in Suchuduller, Ankvnft vnd Einzug, [4]. Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library. Reproduced by permission.

Figure 2. The Imperial Trumpeters, in Suchuduller, Ankvnft vnd Einzug, [6]. Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library. Reproduced by permission.

Figure 3. The Ottoman Embassy's Trumpeters, Shawm Players, and Drummers, in Suchuduller, Ankvnft vnd Einzug, [6]. Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library. Reproduced by permission.

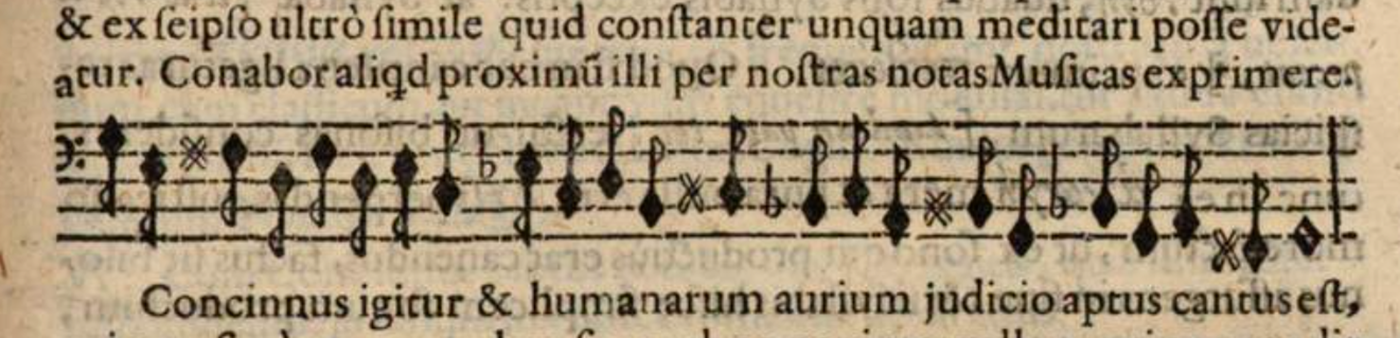

Perhaps because such processions and the accompanying fanfares were relatively routine in the imperial capital, Kepler did not comment on the entry.Footnote 26 Something else—a more private sort of utterance than the military music of the Ottoman mehterhâne, and one usually inaccessible to Christian listeners—caught the astronomer's ear. At some point during the long Ottoman sojourn, he overheard the prayers of a man he identifies as the sacerdos (priest) of the Ottoman ambassador. He struggled in his treatise to describe the man's recitation, representing it or, more precisely, representing his hearing of it, in European music notation (see Figure 4).Footnote 27

Figure 4. Transcription of Ottoman cantillation, in Kepler, Harmonices mundi, III, 62. Public domain.

He notes that the man knelt and repeatedly touched his head to the floor while singing, an observation that suggests he witnessed Qur'anic recitation with sujūd, or prostrations, typical of salat. Kepler's notational representation of the Muslim prayer is curious: simply a set of interlocking descending minor thirds without order or hierarchy, bearing little resemblance to the pitch profiles of Qur'anic recitation. He was either unable to notate it accurately or chose to render it irrationally to underscore his larger point about the rational and natural qualities of Christian song and the irrational and unnatural qualities of non-Christian song. Unaccustomed to quarter-tones—smaller intervals than the tones and whole tones that comprised the European pitch gamut—Kepler heard the chanting as out of tune. He decided that the model for their sounds could not therefore be divine, and that the “truncated, abhorrent intervals” must ultimately derive from some imperfect, crude instrument crafted by human hands.Footnote 28 Listening to the Turkish cantillation, Kepler stacked what he heard against what he knew of the resonances of music's consonances with the divine order of the cosmos, and he found the cantillation wanting.

Although a more commensurable point of comparison to Ottoman cantillation would have been the psalm tones and other recitational chants ubiquitous in Catholic worship, the Lutheran Kepler (perhaps unaware that he was hearing recited scripture) instead contrasts his transcription of Muslim prayer with the Easter sequence Victimae paschali laudes (Praise the Paschal victim), sung by Catholics and Lutherans alike. Sequences are a particularly poetic and tuneful sort of plainchant, and Kepler juxtaposes this especially beloved example with his representation of the Ottoman prayer to demonstrate for his readers—in a form they could test out for themselves—that Christian song gravitates toward consonance and thus to divine order.Footnote 29 Muslim sounds, however, he characterized as dissonant and earthbound: the soulless replication of human error.

Kepler's aural encounter with Muslim prayer reflects his confidence both in empirical observation and in received precepts concerning how a harmonious melody was structured. Certainly, he would have been able to glean these basic principles from his childhood instruction in musical rudiments. But references peppered throughout the Harmonices mundi suggest he had a far more sophisticated musical understanding than his early education could possibly have given him. He was evidently familiar with the objections of the lutenist and music theorist Vincenzo Galilei (father of the astronomer Galileo Galilei) to received canonical theory, for example, and in his discussion of the rules of polyphonic composition he makes reference to the writings of music theorist Gioseffo Zarlino's pupil and apologist Giovanni Artusi, and the German Lutheran transmitter of Zarlinian theory, Sethus Calvisius.Footnote 30 He was, moreover, sufficiently familiar with the music of the Wittelsbach chapelmaster Orlande de Lassus (1530/32–94) to aptly invoke specific compositions (e.g., the motets Ubi est Abel [Where is Abel] and Tristis est anima mea [Sad is my soul]) elsewhere in the Harmonices mundi. His admiration for Lassus puts him in the company of many other Lutherans who found Lassus's music—though connected to the most Catholic of Central European courts and by 1619 somewhat out of date—to epitomize music's possibilities as an art both mathematical and rhetorical.

Kepler's inability to make sense of the Ottoman prayer is unlikely, in other words, to have been a mere mishearing; rather, he heard what he heard because of who he was. He could not help but hear the sounds of the Ottoman prayer with the ears of a European Christian, believing this hearing to be universal and, moreover, believing that Christian music (and only Christian music) was capable of rendering divine sounds audible—perhaps even of echoing them. Significantly, he prefaces his discussion of the Ottoman prayer with a passing jibe at the bestial quality of the battle cries of Ottomans and the Hungarians fighting for them on the eastern edges of the Holy Roman Empire. “Let us say nothing of such strident battle cries,” he writes, but not before saying that these foreigners and non-Christians sound like animals.Footnote 31 Later in the chapter, Kepler quotes a melody that he identifies only as a “very old German one,” showing that even though it begins on a different pitch than the “final” or home pitch, it implies the final at every turn.Footnote 32 This kind of variety in practice is to be expected, he insists, and is, moreover, delightful. The tune he quotes is Christ ist erstanden (Christ is arisen), an eleventh-century vernacular hymn whose text and melodic contour were derived from Victimae paschali laudes. Kepler did not need to identify it because he knew his German readers, whether Catholic or Lutheran, would recognize it and would likely have sung it; moreover, he expected that any readers who did not recognize it would discern in the notated excerpt the sort of well-turned phrase that characterized natural (i.e., divinely ordered) song.

It is not clear what the members of the Ottoman delegation thought of the Christian music or prayer they heard during their time in Prague; unlike the Persian delegation that had visited in 1600, for which the Relaciones of Juan of Persia survives, there appears to be no printed account that conveys an Ottoman perspective on the 1609 visit.Footnote 33 Zimmermann did note in his report that six members of the delegation mocked (gespottet) the celebration of Mass and splattered the holy water (Weichbrunn). Unsurprisingly given his own perspective and his Christian audience, Zimmermann does not speculate about what the visitors might have found ridiculous or objectionable. Instead, he notes the harsh punishment meted out by the Ottoman leaders for these infractions. Zimmermann writes that the culprits were flogged and would have been “hacked” (säbeln; i.e., cut with a sabre) had the imperial equerry (Adam of Waldstein) not interceded on their behalf.Footnote 34

The sort of speculative music theory that informed Kepler's cosmology was already on its way out by the time his treatise appeared. Advancements in tuning theory and acoustics, as well as the transformation of musical style in the ensuing decades (the rise of the so-called stile moderno in its many forms), rendered his musical cosmos obsolete. In 1652, the Spanish-Bohemian polymath Juan Caramuel of Lobkowitz (1606–82) observed from his Prague study that, “There are many who have written about the music of spheres,” recalling that Pythagoras had done so in ancient times. In “our age,” he continued, Kepler grounded this theory geometrically, while Kepler's rival Robert Fludd located it in the principles of tension and release. Caramuel concluded that, for his part, he simply could not hold the music of the spheres—for so long a matter of faith—to be materially true.Footnote 35

A Traveler: Kryštof Harant, Jerusalem and Cairo, 1598

Eleven years before Kepler heard the prayers of the Turkish delegation in Prague, the adventuring nobleman Kryštof Harant of Polžice Bezdružice (1564–1621) had his own series of musical encounters with unfamiliar sounds over the course of an extended pilgrimage to the Holy Land.Footnote 36 His Putowánj aneb Cesta (Pilgrimage or journey; Prague, 1608), is an expansive account of that journey.Footnote 37 As is customary for such travelogues, Harant intersperses his own observations with historical descriptions of the places he visits. Less usual is the careful attention he pays to sounds musical and otherwise, and his inclusion of music notation to communicate precisely what he sang at the many sites he visited that were connected to Christ's birth, death, and resurrection. In his account of visiting the Column of Flagellation, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, and other sites in Jerusalem, for example, Harant includes both the texts and the tune of the hymns he sang at each site. These correspond in text and order to the hymns prescribed in Book 6 of Jean Zuallart's Viaggio di Gerusalemme (Venice, 1587), a widely read travelogue and guidebook, although Harant includes music notation where Zuallart does not.Footnote 38

Departing still further from the norms of the genre, Harant also includes one of his own compositions in his travelogue. At the end of the first part of the Putowánj, he appends a six-voice polyphonic setting of Qui confidunt in Domino (They who believe in the Lord), from Psalm 124 (125) with its message of confidence that those who keep faith in the Lord will enjoy the Lord's protection for eternity.Footnote 39 He explains that the sounds of monks singing polyphony in the evening at their monastery in the shadows of Mount Zion inspired him to write his own setting of the psalm.Footnote 40 He shares his motet with his Czech readers so that they might sing it too, and feel something of what he felt.

A skilled composer, Harant's received musical training came not in Prague but much earlier, at the Innsbruck court of Rudolf II's uncle Archduke Ferdinand “of the Tyrol” where he spent his youth, and where he probably studied with the Flemish chapelmaster Alexander Utendal (1543/5–81). In a world where musical affinities were widely understood to be signs of good character, this early training stood him in good stead. Indeed, in the dedication of his Czech translation of Georg Lauterbeck's Regentbuch, a popular handbook on politics and rulership, the Prague printer Jan Bohutský praises Harant for his considerable skills as a singer and instrumentalist, and above all his skills as a composer—observing that his compositions were much admired.Footnote 41 A portrait by the court engraver Aegidius Sadeler that appears in the prefatory material to the Putowánj (see Figure 5) explicitly positions Harant as a man whose musicality is a sign of his virtue.

Figure 5. Sadeler, portrait of Kryštof Harant in Harant, Putowánj, sign. (*) iijv. Public domain.

His personal motto appears below his visage—disguised, however, in a kind of musical rebus. Using the six “solmization syllables”—ut, re, me, fa, sol, la—that Christian singers had used to navigate the pitch gamut since Guido of Arezzo had devised them in the eleventh century, Harant encodes part of his motto in musical notation: Virtus UT SOL-MI-cat, that is “Virtue like the sun shines,” or more idiomatically, “Virtue shines like the sun” (the clef and position of the pitches allowing no other possibilities). Only a similarly musical (and thus virtuous) reader would be able to decipher the motto.

Having fought the Ottomans on Hungarian battlefields between 1591 and 1597, Harant probably had firsthand experience with the animal-like battle cries that Kepler could only describe secondhand (indeed, one wonders if Harant was Kepler's source). Whatever his prior experience with Ottoman sounds, Harant had no ear for the Ottoman music he heard on his 1598 journey, finding it incomprehensible and in at least one place describing it in explicitly bestial terms. The relevant passage comes in his account of his visit to Cairo, which had come under direct Ottoman rule in 1517. As the sun sets, he and his companions watch people strolling on or near their ships in their finery, and in other places sitting cross-legged in circles. The air is filled with the perfume of flowers and with the sounds of “Turkish” (i.e., Ottoman) musicians. But the sounds that give the local listeners pleasure strike him as ridiculous. Harant divulges that the music moved him and his European companions to discreet laughter because it sounded to them like they were hearing not human musicians but a pig on the pipes and a donkey on a drum, with no trace of harmony.Footnote 42

He then directs his reader to an illustration of three musicians (see Figure 6), writing dismissively that it shows what passes for music among the Turks.

Figure 6. Turkish musicians in Harant, Putowánj II, 59. Public domain.

But the image, executed by the engraver Johann Willenberger after Harant's own sketch, depicts an entirely different sort of musical performance than the evening entertainments he had just described: two men play fretted stringed instruments, while the third sings. The image is sufficiently detailed to suggest that the plucked instrument is a tanbur and the bowed instrument a rebab, and the musicians’ conical caps suggest they are members of the Mevlevi Order of Sufism—and thus that their music may have been a form of prayer.Footnote 43 Harant says nothing about the mismatch between his description and the illustration, nor does he provide any information about the way this performance unfolded. His point is simply that what he hears is not recognizable—by any measure known to him—as music.

Over the course of his journey, Harant regularly used music to communicate with fellow Christians—even when they spoke different languages—and to find common purpose in prayer. Visiting Jerusalem's holy sites, he sang the same Latin hymns countless other Christian pilgrims had sung before him at those same sites. On at least one occasion, a musical encounter revealed a specific connection to his Central European homeland: he reports that among the monks whose singing inspired him to write his setting of Qui confidunt in Domino, there was a Milanese singer who had been a member of the music chapel of Archduke Charles of Inner Austria.Footnote 44 There are other instances in which music helped Harant participate in (not just observe) a local Christian community. Arriving in Candia (i.e., Crete), for example, he found his musical abilities were needed at a local monastery. Still using the old Julian calendar, the locals were celebrating the Feast of Mary Magdalene, which Harant notes had been commemorated ten days earlier in those places (not least the Holy Roman Empire) that had adopted the Gregorian calendar. Having celebrated vespers at their monastery, a group of Discalced Carmelite monks took Harant to a nearby friary for another vespers service. There, the monks sang a five-voice polyphonic setting of the Magnificat (i.e., the Canticle of Mary: My soul magnifies the Lord, Luke 1:46–55), beckoning to Harant to join in on a three-voice setting of the Esurientes verse (Luke 1:53), which he did without hesitation.Footnote 45 Yet when he found himself in the company of Ottoman Turks, music reinforced Harant's sense of distance and difference. Whatever he admired about the performance setting of the music he happened upon in Cairo—the perfumed sunset and the delicate finery—he judged what he heard wafting through the air to be bereft of both reason and harmony. And so, he laughed.

An Exile: Philippe de Monte, Prague and London, 1583

There were no Czech composers in Rudolf's music chapel: as a landed nobleman, Harant was appointed to the more prestigious position of imperial chamberlain (a position with ample room for advancement) and was never paid by the emperor for his compositions. The imperial chapel was instead—and entirely in keeping with similar establishments elsewhere in Europe—dominated by Franco-Flemish singers and composers. They were joined by a handful of Spanish singers (high-voice “discantists”) and chamber musicians who either came from Italy or had trained in Italy. Arriving in Prague, these devoutly Catholic men found themselves surrounded by a populace and a kingdom that was primarily non-Catholic (either Lutheran or Utraquist, i.e., following the teachings of Jan Hus). Rudolf, moreover, showed little inclination toward music and even less toward religion, a situation that only got worse over the course of his reign. This backdrop is essential to understanding a remarkable and celebrated musical exchange between the imperial chapelmaster, Philippe de Monte (1521–1603), and a gentleman of the Chapel Royal at the court of Elizabeth I, the recusant William Byrd (ca. 1540–1621), on texts excerpted from Psalm 136 (137), Super flumina Babylonis (By the rivers of Babylon)—the lament of the Israelites forced to sing while in exile.Footnote 46 Well-known to musicologists, the exchange vividly illustrates how individuals separated by distance and language used Latin polyphony and a common understanding of music‘s workings to assert their shared membership in a single community of faith.Footnote 47

In 1554, the young Monte had traveled to England as a singer in the entourage of Philip II of Spain. The Spanish king remained in England for several months following his July marriage to Mary Tudor, leaving in September of the following year when an expected pregnancy did not materialize. There is little doubt that members of Philip's music chapel and the English Chapel Royal met during this long English sojourn, and it is probably during this period that Monte first met Byrd, who would at that time have been a chorister.Footnote 48 This conjectural meeting between the two would be of little substantive historical interest were it not for their well-known musical “conversation” in the early 1580s, in which they used the musical genre of the Latin motet to comment on the plight of Catholics in lands in which they were a minority. For both Monte and Byrd, the plight was urgent and immediate. The 1581 torture and execution of the Jesuit Edmund Campion while in England on a clandestine evangelizing mission devastated not only the English recusants who supported his cause but also Catholics in Prague, where Campion had been ordained and where he had spent the better part of the 1570s teaching and preaching. Through their private musical exchange (the sole trace of which is a note in an eighteenth-century English copy), Monte and Byrd gave voice to the despair of their dispersed and beleaguered community—but also to its defiance.

The careers of the two composers had proceeded along roughly parallel paths after Monte's English stay. Upon returning to the continent, Monte left the Spanish chapel (unhappy, evidently, at being the only Flemish singer) and after a short period in Antwerp joined the music chapel of Maximilian II. His many prints of madrigals and motets in the 1570s—issued either in Venice, the undisputed center of music printing at this time, or in Antwerp—earned him considerable fame and contributed to the growing reputation of the Austrian Habsburg court as an important player on the European music scene. He was retained as imperial chapelmaster by Rudolf II on Maximilian's death and remained productive, dedicating his numerous prints to eminent Catholic nobles and clerics at home and abroad. Although many imperial composers issued their music at the Prague printing house of Georgius Nigrinus, Monte continued to print his music abroad, preferring to access the more extensive distribution networks of printers in Italy and the Low Countries. A 1579 Mass setting printed in Antwerp traveled all the way to Cuzco, bound with a collection of Mass settings by Philip II's chapelmaster, Philippe Rogier, issued in Madrid in 1598.Footnote 49 Byrd, meanwhile, was appointed a gentleman of the Chapel Royal in 1572, in which capacity he composed settings of Anglican texts that were both useful for and much admired by his employer.

By 1582, Byrd's situation had become precarious, however. Already in 1580 he had been counted among those suspected of furnishing “papists” with shelter, money, and other forms of support.Footnote 50 After Campion's execution in 1581, he wrote a consort song setting Why doe I use my paper, ynke, and pen, an openly seditious poem that celebrated Campion as a martyr. Campion's refusal to remain silent despite the dangers of speaking out (“With tung & pen the truth he taught & wrote”) inspires the anonymous poet to take up his own pen, and “call [his] wits to counsel what to say.”Footnote 51 The printer Stephen Vallenger had his ears cut off and was imprisoned merely for printing the text.Footnote 52 Byrd managed to escape such drastic punishment and his subsequent use of music for political commentary was so veiled as to be nearly imperceptible.Footnote 53

Monte's eight-voice setting of Super flumina Babylonis is among the relatively few of the roughly 250 motets he wrote that was never printed—a point that underscores the private nature of the cross-continental exchange. Manuscript copies were vulnerable to loss, and indeed whatever de Monte sent to Byrd does not survive. A sixteenth-century manuscript anthology in Prague preserves just one of the eight voices of Monte's motet, while an eighteenth-century English manuscript—clearly based on a lost original—transmits the motet in its entirety.Footnote 54 The Prague copy gives no information about why, when, or for whom Monte composed the text. The later English copy, however, includes a note indicating that Monte sent the setting to Byrd in 1583. An eight-voice motet by Byrd setting different portions of the same psalm, appears immediately after Monte's motet in the English source, along with a note indicating that Byrd sent it to Monte in 1584.

The motets comment on each other and on the wider predicament facing Catholics in England, Bohemia, and in Monte's homeland textually and compositionally. Reflecting a widespread practice of combining and reordering Biblical and liturgical texts to convey specific meanings, Monte rearranged the verses of Psalm 136 as follows:

In this way, Monte's motet builds up to the question: “How shall we sing the song of the Lord in a foreign land?” In his setting, surely written with the knowledge of what had happened to Vallenger, or at the very least with a grim understanding of the risks of professing Catholicism in Elizabeth's England, the question of how to sing in a hostile land is answered with an earlier verse, such that the motet ends in silence: “On the willows in the midst thereof, we hung up our instruments.” Monte's decision to write for eight voices creates an unusually dense sonic texture even for the period and demonstrates his formidable skill at controlling dissonance among the interacting voice parts.

In Quomodo cantabimus in terra aliena, Byrd began where Monte ended: with the question “How shall we sing in a foreign land?” (Psalm 136:4). Byrd looked to scripture and found a very different answer than Monte. Letting the subsequent verses unfold exactly as they do in the psalm, the answer to the question posed by Byrd's motet is a fiery commitment to faith, where silence is a mark of those who have forgotten their spiritual home: “If I should forget you, Jerusalem, let my right hand fall idle. Let my tongue stick in my throat, if I do not remember you.”Footnote 55 In his musical rejoinder to Monte's motet—and a rejoinder it is—Byrd outdoes the older composer by embedding a canon, an exact imitation of a given melody, in three of the eight voices. With this display of compositional virtuosity, Byrd shows himself to be unwilling to “hang up his instruments” under the threat of persecution, as Monte's motet had pessimistically suggested. As the mutilated printer Vallenger languished in jail—having used his paper and his ink to encourage Catholics to write and to speak—Byrd reached across Europe and encouraged Monte to sing.

Conclusion

Music could travel in ways that paintings could not. Bought and sold, collected and bequeathed, it could and did travel deep within and far beyond Central Europe. As such, it offers a particularly useful perspective from which to consider the larger questions centered in this forum relating to Prague's status as a “global” city. Operating according to a narrow set of principles laid out in such treatises as Gioseffo Zarlino's influential Le Istitutioni harmoniche (Venice, 1558), composed polyphony was a lingua franca among sixteenth-century European Christians. In theory (theory that, crucially, shaped practice), music connected the majority of Prague's inhabitants to those of Antwerp and Madrid and London and even colonized Cuzco, holding diverse peoples in a single imagined community and keeping them in alignment with the invisible world and the movements of celestial bodies—taken in the sixteenth century, as they had been since classical antiquity, to be ordered according to the same harmonious proportions that ordered audible music.Footnote 56 Understood thus, music also necessarily left out those Europeans and those of Prague's residents—Muslims and Jews—who sounded different and who understood music differently, and whose presence could only be accounted for as dissonance in God's divine order.

The emphasis in musicological literature connected to Habsburg courts (and the Rudolfine court in particular) has long been on the preferences and inclinations of the patron. Hartmut Krones proposes that the compositions of Philippe de Monte and Carolus Luython traffic in a sort of “musical mannerism,” something akin to the sophisticated and artificial style characteristic of Rudolfine visual artists.Footnote 57 Nicholas Johnson hypothesizes that the pitch content of specific compositions engages the emperor's well-known interests in astrology and hermeticism.Footnote 58 Most recently, Christian Leitmeir argues for a sonic expression of Rudolf II's apparently pacific ideals in polyphonic settings of the votive antiphon Da pacem Domine (Grant us peace, O Lord) by his composers, pointing to their use of an unusual and plangent chromatic inflection of the chant melody.Footnote 59 The search for distinctively “Rudolfine” musical tendencies has sometimes obscured the rich and productive relationships his musicians cultivated locally, with institutions in the city below Prague Castle (an avenue that Czech scholars in particular have been exploring), as well as their participation in broader musical-stylistic movements, diplomatic exchanges, and epistolary networks that spanned Europe.Footnote 60

The cases of Kepler, Harant, and Monte—singular but not unique—suggest that there is much to be gained by thinking about how music helped ordinary people understand the world around them. Benefiting from the presence of the imperial musicians, Prague's citizenry, too, made music and collected it. The most learned among them listened closely to the music of their own communities of faith and language and assessed the musicality of those who differed from them in language and religion—responding to these other sounds sometimes with wonder, sometimes with revulsion. I have shifted the focus in this article away from the emperor and toward some of the men who made his court their home to show that sometimes it was in private moments—in overhearing unfamiliar sounds, or in sending and receiving motets to a like-minded acquaintance, knowing they might never be performed in public—that early modern individuals used music to think about themselves and to understand themselves in relation to others. Today the historian encounters a composition, or a fragment of notation, or a description of a performance, as an artifact.Footnote 61 Yet for the early moderns who thought about how to describe what they heard, who puzzled over how to write it down, or who looked at a musical passage and sang it to themselves, music was present as a living thing, mediating actual encounters.