Introduction

Farvi (locally Farvi/Farvigi) is a variety of Central Iranian languagesFootnote 1 spoken in Farvi (Persianized Farrokhi), a village in Kavir desert belonging to the Biabanak Rural District, in the Khur and Biabanak County, Isfahan Province, Iran. The village is located some 240 km east of Nāyin and 17 km west of Khur Township, at the geographical location of latitude 33.8423° and longitude 54.9529°. Its population is 3,015, in 668 families at the 2016 census. The main commercial activity in the region is cultivation of palm and grains.

Closely related to Farvi are the languages spoken in Khur and some other villages on the southern border of the central desert (Dasht-e Kavir) such as Khur, Irāj and Garma. Farvi and other Khur languages are generally listed as a subgroup of Central Iranian languages,Footnote 2 but historical phonology and some morphological features as presented in this paper show that, despite being basically Northwestern, Farvi shares some features with Southwestern Iranian languages that detach it not only from Central languages but also from other northwestern languages. It also shows further sound changes shared by Kurdish and Balochi which apparently separate them from the rest of the Northwestern languages. In later changes, Farvi shows some areal features that relate it to Northern Bashgardi and Balochi.

Farvi was first commented on in short articles by R. FryeFootnote 3 and S. KiāFootnote 4 which only included some Farvi words and sentences. Other data on its lexicon later collected by S. Kiā was provided in a dictionary of sixty-seven Iranian dialects published in Tehran after Kiā’s death.Footnote 5 A brief update is provided in Borjian,Footnote 6 where the article under “Farvi dialect” in the Encyclopaedia Iranica contains a short description of the language, but seemingly based on the data previously collected by Kiā and Frye. However, there are some differences between the data collected by the author with those attested in Borjian’s article, which might be due to different references the author used. However, all his data have been examined by the author of the current paper. A more detailed description on Khur languages was given by Borjian on Khuri.Footnote 7 He gives an outline of some morphological features and then sketches the historical phonology.

The present paper involves a description of phonology and grammar of Farvi, based on the corpus for the current study collected by the author in Farvi during April 2019, with the aim of providing more elaborate description. First attempts at achieving this aim have recently been made by Borjian. More specifically, this article discusses the phonological and lexical features that Farvi shares with Balochi and Kurdish, and with Southwestern languages to highlight it as a distinct language and distinguish it from central languages. The following language users were consulted: Ahmad Rāji (age fifty-six), Hosein Ra’isi (age thirty-eight), Zeynab Khademi (age fifty-one), Nafise Rāji (age twenty-one), Mohammad Khādemi (age forty-seven), and Ahmad Ra’isi (age twenty-six); all of them are native speakers of Farvi who had been living in Farvi all their lives.

Phonology

Synchronic phonology

The vowel system of Farvi has six short and long vowels /a/, /e/, /o/, /â/, /ī/, /ū/ and two falling diphthongs: back-falling /ua/ and front-falling /ia/. Yet the quality of vowels may vary in phonetic positions.

/a/, a short central vowel corresponding to Pers. /a/: arg “saw,” asse “bone,” tag “bottom, base,” gazar “big,” mazge “mosque,” galg “leaf,” gīsa “goat.” There is some variation in articulation of this vowel as [ε] and [e], especially in final position: mεhīk “fish,” sεg/seg “stone,” pešt “back,” gaččε “child,” tε “you,” fa/fε/fe “self.” It seems that the final /a/ is generally raised and fronted as [ε], but, affected by Persian, the final [ε] is switched to [e] in order to coincide with the Persian vowel system. As the second part of the diphthong /ia/, it is also raised as [ε]: biεlâ “top, high,” debiεre “he cuts.” Before /r/, it is centralized as [ə]: sərâ “house,” xərā “spoiled, demolished,” səreve “sneeze.”

/e/ is a short close-mid front unrounded vowel that generally corresponds to Pers. /e/: emšā “tonight,” eškâr “gazelle,” eštar “camel,” berâ “brother,” kešõ “field” and pe “father.” /e/ also coincides with /o/ or /a/ in Persian and most Iranian languages: mess “fist,” derū “lie” and je “woman.” It may also be closed to [i] in the final position: gešši “hungry.”

/o/ a short, close-mid back unrounded vowel normally corresponds to /o/ in Persian: ošnū “sneeze,” mošk “mouse,” botte “tree”; but it may also correspond to Pers. /a/ and /â/: gormâ “heat,” kong “laugh,” resso “rope,” dong “seed,” oftā “sun”; and to Persian /ū/ and /o/: botte “tree” (Pers. būte) and pos “boy” (Pers. pəsar).

/â/ is a long open central vowel generally corresponding to Pers. /â/:Footnote 8 âyar “fire,” fâr “sister,” nâg “nose,” rīvâj “rhubarb,” mâ “mother” and gâ “wind.” It has an allophone as [ā] ([æ:] in IPA) that corresponds to Pers. /â/ and appears in words that have retained MIr. ā: gāfe “sheaf,” sāv- “to rub,” tāve “pan,” gā(v) “cow”Footnote 9 čerā “lamp,” biyāvehon “they came.”

/ī/ is a long close front vowel corresponding to Pers. /ī/ and /ū/: tīj “sharp,” rīj “beard,” kīsg “haversack,” zī “early, quick,” gīšt “meat,” rīva “face,” kīča “alley.” In some words, it corresponds to Pers. /a/ and /â/: kīm “few, little” and gīj “cotton,” mīn- “to stay,” sīj- “to build,” šīm “dinner.”

/ū/ is a long close back vowel, corresponding to Pers. /ū/: gūj “ear,” dūj “yesterday,” lūš “mud,” ganū “wild pistachio”; but in some words with Pers. /ow/: rūš “light,” nū “new.”

The back-falling diphthong /ua/ historically developed by diphthongization of ū and u before h (cf. below) generally corresponds to Pers. /o/ and /ū/: duahd “d,” suahr “red,” muahre “marble,” suahd- “to burn” (but present stem sūj-), kuahnag “old, worn out” (corresponding to Pers. kohne not to Central languages kana and the like), juahn “stony mortar” (cf. Khuri john), rueje “fast” and tuare “jackal.” This kind of diphthongization is an areal feature and a common phenomenon among some varieties of Northern Bashgardi in the Kerman region, and it seems to be the result of language contact or a common substratum contact.Footnote 10

The front-falling diphthong /ia/ that might appear as [iε] corresponds with varieties of vowels, but generally with Pers. /ī/: diar “late,” bial “spade,” siav “apple,” piahrõ “shirt,” hegiahd-/hegiaj- “to sift,” xonokia “coldness”; but also with /e/ before /h/: miahmõ “guest,” tiahrõ “Tehran,” giahtar “better,” geria “knot, node”; with /ū/: riavī “day,” raviahd- “to sell”; with /â/: riah “road, path,” ketiav “book,” biεlâ “top, up”; and in one case with /aw/: kiaj “shoe” (Central languages kawš, Pers. kafš).

The consonant system of Farvi is basically similar to that of colloquial Persian with the following exceptions: contrary to Khuri /ž/ in words like žōnugun “women,”Footnote 11 /ž/ is not found in Farvi, and is replaced by /j/: jenũ “women.” The velar /q/ corresponds to Pers. /q/, appearing as aspirated [qh] in words with Arabic origin: qhevā “traditional long shirt for men,” qhâlī “carpet,” qhadīmũ “old days,” čoqhada “how much,” but also /q/ may appear as [γ] in intervocalic and final postvocalic positions (historically from OIr. intervocalic k or g): sīγor “porcupine” (cf. Balochi sikun, Av. sukurəna-), maγas “fly,” dūγ “yogurt drink.” A notable feature is the retention of the pharyngeal /ħ/ and /ʕ/ in all words of Arabic origin: sobħat “talk,” ħasan “Hasan” (proper name), maħmad “Mohammad” (proper name), moħazemũ “Mohamad Zamân” (proper name); sâʕat “hour, time,” ʕalī “Ali” (proper name), moʕalem “teacher.”

Some phonological features and processes on other consonants can be noted: final postvocalic -n is deleted, and in most cases resulted in nasalization of the former vowel: je “woman,” sīje “needle”; nũ “bread,” hezũ “tongue,” fɛmũ “ourselves,” tiahrũ “Tehran,” piahrõ “shirt,” niahrĩ “curse.” When the word is suffixed by an enclitic or inflectional suffix, the final postvocalic -n appears: jenū “the woman,” jenũ “women” and piahrōn-e espī “white shirt.” The final /rd/ is deleted in past stems when not suffixed: beka “he did” vs. karda bī “he had done” as in the deletion of -t in final post-consonantal position: algeref “he picked up,” befaf “he slept.” Notable is the use of -g- as a hiatus consonant when a word ending in a vowel is suffixed by an enclitic or inflectional suffix: gačča “child” >gaččag-õ “my child,” yagīna “fried egg” >yagīnag-eĩ karde “they have made fried egg,” fī “farmland” >fīg-eyū beraviahd “they sold the farmland,” hâmela “pregnant” >duahd-e hâmelag-ĩ “his daughter is pregnant,” qhâlī “carpet” >qhâlīg-eĩ degaft “they wove carpet,” riavī “day” >riavīgūn “days.” The process is also frequently seen in Khuri: sebi-g-ẽ “it is morning.”Footnote 12 The common use of -g- as intervocalic connector is illustrated by the examples showing that OIr. suffixal -ka (Middle Iranian -g) has commonly remained as final -g in many words like dâng “seed,” âyeng “mirror” and tag “bottom,” but also extended analogically to other words (see also below).

Historical phonology

Northwestern features. From a historical point of view, Farvi demonstrates sound changes shared by Northwestern languages that make it possible to consider them as Northwestern languages. This means that Farvi shares a set of features with other Northwestern languages such as Balochi, Talyshi and Central languages, which are already seen in Parthian (Prth.), whereas Southwestern Iranian languages such as Persian, Lori, Larestani and Bashgardi show different features that are already seen in Middle Persian (MP). According to Korn,Footnote 13 most features of Northwestern Iranian languages are of a type of “shared archaism,” i.e. these languages retain the developments already shown by Parthian. The most important sound changes in Farvi that will be discussed below show that Farvi belongs to the Northwestern group:Footnote 14

1. The development of OIr. *s (from PIE palatal velar *ḱ) that has established an isogloss in Iranian languages and separates Old Persian from the other Old Iranian languages in the Old period, and separates Northwestern from Southwestern languages is marked by the change of OIr. *s to Farvi s contrary to h in Southwestern languages: pas “goat” (OIr. *pasu-, Av. pasu-, cf. MP pah, Prth. pas “sheep”); ruâsg “fox” (OIr. *raupāsa-, Skt. lopāśa-, Prth. rōbās); kas “small” (OIr. *kasyah-, Av. kasu-, MP keh, Prth. kasādar “smaller”); gīsa “female goat” (PIr. *watsya-, cf. Skt. vatsya-, and its Southwestern form in MP wahīg and Bakhtiari bīg “kid”); tias “awn” from older tās (cf. the sound change of â to ia in Farvi, see below) <OIr. *dāsa-, cf. Talyshi dos, Gazi dâse, as against Boirahmadi and Larestani daha. Footnote 15

2. The other established isogloss in Iranian languages is the retention of OIr. *z as z in Northwestern languages but its development to d in Southwestern languages. Farvi joins the Northwestern as marked in just two lexical items: zonī-/zon- “to know” (OIr. *zan-, Av. zan-, MP dān-, Prth. zān-); and zomâ “bridegroom” (OIr. *zāmātar, Av. zāmātar-, MP dāmād, Prth. zāmād). Borjian shows that Perside /d/, as in duj “yesterday” and dušaw “last night,” is an isogloss Farvi shows with Southwestern languages, but duj is from OIr. *daušā- (cf. Av. daošastara-, Oss. dyson, Skt. doṣā-), which does not reflect an OIr. *z.

3. The OIr. initial cluster *hw- changed further to ẉ in Prth;Footnote 16 it has changed to f- in Farvi, which places Farvi alongside Khuri and Sivandi as the only Iranian languages possessing this feature: fâr “sister” (OIr. *hwahar-, Khuri fār), fĩ “blood” (OIr. *hwahūni-, Khuri fin, Sivandi fīn), fârd-/far- “to eat” (< OIr. *hwar-, Sivandi fārdan); faft- “to sleep” (OIr. *hwafta-, Khuri fāfton, Sivandi fetan); fɛ “self” (Av. xvatō, Khuri fa, Sivandi fey). As wx- in Prth. was probably pronounced as devoiced w-, we can take *w- as the starting point of departure that seems far away from the Southwestern change to x(w)-, which reveals a Northwestern development.

4. Old Iranian j changes or remains as j in Farvi: je “woman” and pireje “old woman” (<OIr. *jani-, Av. jaini-) and tīj “sharp” (OIr. *taija-). A similar sound change is found in the development of OIr. intervocalic č to Farvi j: rueje “fast” from older *rūj “day” (OIr. *raučah- “day,” Av. raočah-, MP rōzag); sīje “needle” (OIr. *sūčī-, Skt. sūcí-); novâj “worship, prayer” (cf. MP namāz, Prth. namāž) as well as the present stem of the verbs: sūj- “to burn,” sīj- “to make,” pej- “cook, bake,” gaj- “to uproot,” hegiaj- “to sift” and (he)rīj- “to pour.”

5. The change of PIr. *sw- to sp is found in only one word, espej “louse” (<OIr. *spiš-, Av. spiš-), as a Northwestern feature. Though it also found in espī “white,” it is not necessarily representative of genuine Northwestern features, because similar sound changes are seen in Middle Persian and other Southwestern languages.

6. Despite Central languages, OIr. f has remained before t, e.g. gereft- “take”, like most Central languages, OIr. *fr has developed to *r or *hr: raviahd-/raveš- “to sell” (<OIr. *fra-waxša-), niahrĩ “curse” (OIr. *ni-frī-nā-, Pers. nefrin), kuar “kid” (OIr. *kafra-), and in the preverb he-/ preposition he (<OIr. *fra-/frā-), which is retained in verbs such as hedâ- “to give,” hegiahd-“to sift,” henvešt- “to sit,” but not in tarf “lactic acid, sour extract of yogurt water” (<OIr. *tafra-, cf. Prth. tafr, Khwarezmian trf, Sogd. trp’r’k).

Southwestern features. The following sound changes show that Farvi, although basically Northwestern, regularly shows some Southwestern features that put it alongside Kurdish and Balochi and distinguishes it from the other Northwestern Iranian languages by a number of phonological developments known to be specifically Persian. A list of the similar features for Khuri has already been given by Borjian. He shows that at the Old Iranian stage, most isoglosses reveal that Khuri is a non-Perside language, while in the Middle Iranian period Khuri demonstrates significant isoglosses, which, as it possesses features belonging to both groups, categorizes it between Northwestern and Southwestern languages:Footnote 17

1. The sound change of OIr. y- and wy- to j- in Farvi is also seen in Balochi and Kurdish,Footnote 18 which can be considered as a Southwestern feature, connecting Farvi to Balochi and Kurdish as the only Northwestern languages having this feature: jârīg “husband’s brother’s wife” (OIr. *yāƟrīka-, Skt. yātar-), jā “barely”; juahn “stony mortar” (<OIr. *yawa-arna-, Av. yāvarǝna-; cf. Meymai yâna, Jowshaqani yahan, Boirahmadi jeven), jōfũ “threshing-floor” (<OIr. *yawa-hwana-, cf. Boirahmadi jəxūn, Abyanai yōvīn);Footnote 19 jâ “alone, separate” (as against the Northwestern form in Jowhshaqani yadâ, Prth. yud, Av. yuta-). Although jâ “place” may be affected by Persian, but jâgâ “bed” can be a genuine Southwestern form as its Northwestern form is seen in some Central languages such as Jowshaqani yâgâ “quilt”; johũ “nice, beautiful” (OIr. yuan-, Av. yuuan “young,” cf. its Northwestern form in Southern Tati yōnagā “bull calf, young cow”Footnote 20) shows another isogloss with Southwestern languages, but can also be a loanword from Persian. Borjian quotes some other examples in Khuri: āji “there,” juš- “boil” and jōvion “to chew.”Footnote 21

2. Both OIr. *rd and *rz appear as l in Farvi: hal- “to let, to allow” (Khuri hēl-, <OIr. *h

za-, against Northwestern form harz-, cf. Prth. harz-); esbelūk “spleen” (OIr. *sp

za-, against Northwestern form harz-, cf. Prth. harz-); esbelūk “spleen” (OIr. *sp zan-, Av. spərəzan-, against Jowshaqani sparza); preverb al- “up” as in alsat- “to weigh,” algereft- “to pick up” (OIr. *

zan-, Av. spərəzan-, against Jowshaqani sparza); preverb al- “up” as in alsat- “to weigh,” algereft- “to pick up” (OIr. * dwa-, Av. ǝrǝdwa, Central languages âr-), not corresponding to Central languages var- as Borjian has proposed.Footnote 22 Farvi bialâ “up” and Khuri bolō may be Persian loanwords. Although this feature is shown by only three words, these seem to provide evidence of a Southwestern development in Farvi. Borjian notes Khuri bēl “spade” as the reflex of OIr *rd in Khuri. Despite being a Southwestern feature, it is not a reflex of OIr. *rd. Farvi bial “spade” and Khuri bēl are from older *bayl <OIr. *badra- by lenition of -d- to -y-. However, Central languages bâla and bard “spade” are from OIr. *barda-.

dwa-, Av. ǝrǝdwa, Central languages âr-), not corresponding to Central languages var- as Borjian has proposed.Footnote 22 Farvi bialâ “up” and Khuri bolō may be Persian loanwords. Although this feature is shown by only three words, these seem to provide evidence of a Southwestern development in Farvi. Borjian notes Khuri bēl “spade” as the reflex of OIr *rd in Khuri. Despite being a Southwestern feature, it is not a reflex of OIr. *rd. Farvi bial “spade” and Khuri bēl are from older *bayl <OIr. *badra- by lenition of -d- to -y-. However, Central languages bâla and bard “spade” are from OIr. *barda-.3. For the sound change OIr. *θr, Farvi joins Southwestern languages which have s contrary to the r or hr in Northwestern languages: pos “boy, son”; āves “pregnant” (OIr. *āpuƟra-, cf. Bashgardi yōpes, Bakhtiari awos, against Central languages âvira and the like); dâsg “sickle” <OIr. *dāƟra-, Skt. dātra- as against Central languages dâr and the like (cf. Khuri pos “son,” ōves “pregnant,” although Khuri ōsio may be a Persian loanword).

4. For the sound change of OIr. *dw- to Northwestern b- (contrary to Southwestern d-), as a Southwestern isogloss, Farvi and Khuri, like MP and other Southwestern languages, demonstrate the development of *dw- to d-:Footnote 23 de “other, again” (<OIr. *dwitia-; MP did, Prth. bid); dar “door” (<OIr. *dwar-, Av. duuar-, MP dar).

Later changes. There are some innovative sound changes that have occurred in Farvi, some of which are shared with Southeastern Iranian languages. The following sound changes can be regarded as specific to Farvi and had not appeared in the Northwestern development period:

1. The initial OIr. *w- has been changed to g- in Farvi, that relates Farvi with Southeastern Iranian languages such as Northern Bashgardi and Balochi. This sound change can be regarded as an areal feature Farvi shares with Southeastern languages: gâ “wind” (OIr. *wāta-, Av. vāta-), galg “leaf” (OIr. *walka-), gâyem “almond” (MP wādām); gazar “big” (OIr. *waz

ka-), gad “bad,” gar “beside,” gīss “twenty” (OIr. *wisati, Av. visaiti), ganū “wild pistachio” (OIr. *wanā-, Av. vanā-, Bakhtiari and Boirahmadi ban “wild pistachio”); got-/gaš- “to say” (OIr. *waxta-/vaxš-); geheš “paradise” (OIr. *wahišta-, Av. vahišta-); giahtar “better” (MP wehtar). Some more examples for Farvi are recorded by Borjian: garf “snow,” gas “enough,” gar “side,” gāng “voice, call,” and gehina “pretext.” A similar change is seen in Khuri: gad “bad,” gīd “willow,” gara “lamb,” gahi “bride” and gen- “to see.”Footnote 24 The same is true for OIr. *w

ka-), gad “bad,” gar “beside,” gīss “twenty” (OIr. *wisati, Av. visaiti), ganū “wild pistachio” (OIr. *wanā-, Av. vanā-, Bakhtiari and Boirahmadi ban “wild pistachio”); got-/gaš- “to say” (OIr. *waxta-/vaxš-); geheš “paradise” (OIr. *wahišta-, Av. vahišta-); giahtar “better” (MP wehtar). Some more examples for Farvi are recorded by Borjian: garf “snow,” gas “enough,” gar “side,” gāng “voice, call,” and gehina “pretext.” A similar change is seen in Khuri: gad “bad,” gīd “willow,” gara “lamb,” gahi “bride” and gen- “to see.”Footnote 24 The same is true for OIr. *w - that is retained as go(r)- contrary to va(r)- or ve(r)- in Central languages: gorde “kidney” (<OIr. *w

- that is retained as go(r)- contrary to va(r)- or ve(r)- in Central languages: gorde “kidney” (<OIr. *w dka-, cf. MP gurdag), gorg “wolf” (<OIr. *w

dka-, cf. MP gurdag), gorg “wolf” (<OIr. *w ka-, cf. MP gurg), gešši “hungry” (<OIr. *waršna-, cf. MP gursag, with š also showing guna-grade in Northwestern vs. zer-grade in Southwestern that derived from OIr. *w

ka-, cf. MP gurg), gešši “hungry” (<OIr. *waršna-, cf. MP gursag, with š also showing guna-grade in Northwestern vs. zer-grade in Southwestern that derived from OIr. *w sna- with OIr. Vocalic

sna- with OIr. Vocalic  ).

).2. The older *w (genuine or from older ab or af) after a or ā is deleted and resulted in compensatory lengthening of a: ā “water,” ār “cloud,” ārīv “dignity” (from older *awrū<ābrū), jā “barley,” gā “cow,” šā “night,” xā “sleep,” lā “lip,” sāz “green,” qhār “grave,” dār “around, round, cycle” (cf. Pers. dowr), hāda “seventeen” (<older *hawdah<hafdah), tanā “rope” (cf. Pers. tanâb) and jelā “front” (Pers. jelow); but by joining an enclitic or a suffix, the older *w appeared or has remains as v: šavũ “nights,” ya gāvī “a cow” and av-e rī âyar beriahd “he poured water on fire.”

3. Older h is generally remained in all positions: hemī “still” (<*ham-nūn), hezũ “tongue” (from older ezwān by the addition of initial h- Footnote 25), huas- “to sleep” (OIr. *hufsa-), hamā “we,” kuahnag “old, worn-out,” geheš “paradise” and muahre “marble.” Initial and preconsonantal *x is changed to h without later deletion of h: hargūj “rabbit,” hūj “ear of grain or palm” (from older *xūš <OIr. *auša-), hormâ “palm, date,” tahl “bitter” (OIr. *taxra-, cf. MP taxl), čahr “spinning wheel” (<OIr. *čaxra-), suahr “red” (<OIr. *suxra-, cf. MP suxr); duahd “daughter” (<*duxt), gahd- “to uproot” (OIr. *waxta-, cf. Jowshaqani vat-/vaj-), riahd- “to pour,” hegiahd- “to sift,” raviahd- “to sell” (<OIr. *fra-waxta-), pahd- “to cook” (<OIr. *paxta-), âsuahd “ash,” although preconsonantal *x is deleted in Khuri: čēr “spinning wheel,” sɔr “red,” dōd “girl, daughter,” red- “spill,” sēd- “weigh,” reved- “sell.”Footnote 26

4. The OIr. intervocalic *t which had previously developed to d in MP and Prth. has changed to y through lenition of the d: âyar “fire” (OIr. *ātar-, MP ādur); kaye “winter cottage” (OIr. kata-, Prth. kadag); mâya “female” (OIr. *mātā, Prth. mādag), diya “seen” (OIr. dīta-), gâyem “almond” (OIr. *wātāma-, MP wādām). Final postvocalic d (from OIr. itervocalic t) is lost: pe “father” (OIr. pitā, Prth. pid), mâ “mother” (OIr. mātā, Prth. mād), zī “quick(ly) (<OIr. *zūti-, Av. uzūiti-). The change is also found in Khuri: māyā “female,” čoyor “veil,” keyyā “room,” moy/mā “mother,” pī(o) “father,” zi “early.”Footnote 27

5. One of the specific features of Farvi is the sound change of -š to -j in final postvocalic position:Footnote 28 rīj “beard,” mīj “ewe, sheep,” kiaj “shoe,” gūj “ear,” hūj “ear of grain or palm,” hargūj “rabbit,” espej “louse” (OIr. *spiš-), dūj “yesterday” (OIr. *daušā-, Skt. doṣā-), pīj “palm coir, palm fiber” (cf. Pers. pūšâl, Bakhtiari pīš), gīj “cotton” (Pers. vaš “unginned cotton”). A similar change is seen in Khuri by vocalization of the final š: duž “yesterday,” huž “bunch,” riž “beard,” miž “ewe,” guž “ear,” kož- “to kill,” kēž “shoe.”Footnote 29

6. Old Iranian cluster st has changed to ss by total assimilation of t with s, but to s in initial position: sâre “star” (OIr. *star-, Av. star-), ssay-/ssīn- “to buy” (OIr. *stan-, MP and Prth. istān- “to take,” Pers. sitad-/sitān-), asse “bone” (OIr. *astaka-, Av. ast-), mess “fist, two-hand fist” from a Southwestern form *must (cf. Bakhtiari most, Boirahmadi mos; OIr. *mušti-, Av. mušti.masah-), angossar “ring” from Southwestern form *angust (cf. Bakhtiari angost, Boirahmadi angōs; OIr. *angušta-, Av. angušta-). However, Farvi mess “fist, two-hand fist,” angossar “ring” and Khuri mes “fist,” āngos “finger” show an isogloss with Southwestern languages.Footnote 30

7. While the OIr. au generally changed to ū in Farvi, OIr. ū remained in MP and Prth. and later developed as fronted ü in Central languages it changed to ī in Farvi: zī “early, quick(ly)” (<OIr. *zūti-, Av. uzūiti-), sīje “needle” (OIr. *sūčī-, Skt. sūcí-), fĩ “blood” <fīn (OIr. *hwahūni-, cf. Khuri fin), šīv “husband” (cf. Central languages šü); and in some other words with an unetymological origin: kīče “alley,” pīj “palm coire” (cf. Pers. pūšâl), šī “bottom, down” (cf. Northern Bashgardi šue). In some other examples, Borjian shows the fronting of Middle Iranian ō to Farvi ī: rī “face,” mīv “hair,” šiv “husband,” gišt “meat” and rixune “river.” The same change occurred in post MIr. ū created by the loss of postvocalic h and compensatory lengthening of u: pīl “bridge” <*pūl <puhl; or ū created by rising of ā before nasals: šīm “dinner, night” <šūm <šām (cf. āsmin; <āsmun <āsmān) “sky” recorded by Borjian.

8. The change of intervocalic -m- to -v- as a particular characteristic feature of Farvi is seen in some words: noviang “salt” (<*nemeng), novâj “prayer,” where the late date of the sound change is shown by forms like biyāvehon “they come.” A similar change also occurs in a small number of other west Iranian languages like Bakhtiari (nevek “salt,” havīr “paste,” hīve “firewood,” dovâ “bridegroom,” jove “shirt”), Kurdish (nāw “name,” dūw “tail,” hawīr “paste” and kawān “bow”)Footnote 31 and some Northern Balochi varieties (nawāš “prayer,” hāwag “raw”). Although this change may be explained as independent developments and not an inherited common feature of all these language, in the case of Farvi and Northern Balochi, which are spoken in an area relatively close to each other, it may be an areal common feature in these two languages.

9. The sound change of ā to ī is found in certain words: ssīn- “to buy” (cf. MP istān-, Pers. sitān-), kīr- “to sow” (MP and Prth. kār-), sīj- “to build, to make” (Prth. sāž-), mīn- “to stay” (MP and Prth. mān-); and in some examples changes from a to ī: kīm “less, lesser” (MP and Prth. kamb), gīj “cotton” (Pers. vaš).

10. The sound change of intervocalic -b- to -v- also appears in a great number of Iranian languages, as seen in words like: tāve “pan,” kavā “kebab” and ketiav “book.” It seems that this is a relatively recent, post-Middle Iranian feature which adds to the changes common to other new Iranian languages.

11. A great vowel change is diphthongization of closed vowels. In Farvi, original long ū (from Middle Iranian ō) and short o before h (older u before h) is diphthongized as ua: ruaje “fast,” tuare “jackal” (cf. MP tōrag), balγuar “crushed wheat” (cf. Pers. balγūr), suahr “red,” duahd “daughter,” suahd- “to burn,” muahre “marble,” nuah “nine,” kuahnag “old, worn out,” guahres- “to ask” (<*gohres- <*wi-fras- ?); but also in some other words seemingly from older a: šuaš “six” (from šaš?), gījua “mold” (cf. gīj “cotton”), puahn “wide” (cf. Pers. pahn), and some other example from Borjian’s data: fuahm “understanding” and kuar (cf. Khuri ka:rɔ) “kid.” In some words, the diphthongization has caused a change in syllable break and the ua has developed to va: kolva “clod, lump” (<*kolū, cf. Pers. kolūx), golvale (from golūle, cf. Pers. golūle), ârvas “bride” (<*ârūs, cf. Pers. arūs), nârvaz (<older nawrūz) “Nowruz,” borvahna “naked” (cf. Pers. berahne), dohvason “they sleep” (from de-huas<de-hus). Another diphthongization found in Farvi is the change of older ī (from Middle Iranian ē) and e before h (older i before h) to ia: bial “spade,” diar “late,” siav “apple” siar “full, satisfied,” piašīm “noon” (MP pēšēn, cf. Central languages pīšīm “noon”), miah “nail,” hegiaj- “to sift,” biar- “to cut”; so is the change in kiaj “shoe” (< *kij< *kūj> *kawš, cf. Central languages kawš, Pers. kafš) and riavī “day” (<*rīv<*rūj), giahtar “better” (MP wehtar), niahrĩ “curse” (cf. Pers. nefrīn), siahr “pool, pond” (cf. Boirahmadi sēla “pool, pond”), diah “village” (Pers. deh), geria “knot, node” (Pers. gereh), riahd- “to pour” (MP rixt-), hegiahd- “to sift” (MP wixt-). Also, in some words the change is found in ā to ia: riah “road, path,” tias “awn” (from older *tās, cf. Central languages dâse/tâse), kiard “knife” (Pers. kârd), biεlâ “top, up,” haštia “eighty.”

Morphosyntax

Noun. Without the distinction of case and gender, morphological categories in nouns include number and definiteness. The plural suffix is -ũ (from older -ūn<-ān) for nouns ending in a consonant: jenũ “women,” segũ “stones” and siavũ “apples”; the suffix -gũ for nouns ending in vowels except -â: botte “tree” >bottegũ “trees,” čū “wood” >čūgũ “woods” and fī “farmland” >fīgũ; and the suffix -vũ for nouns ending in -â: pâ “foot” >pâvũ “feet,” and hormâ “palm, date” >hormâvũ “palm, dates.” Borjian refers to -(g)ún as a plural markers in gačegūn “children” with no example for -un allomorph. -g- and -v- are hiatus consonants inserted between the final vowel of a noun and the plural marker. For all the three allomorphs of plural markers, if a noun is suffixed by an enclitic, the final -n appears after nasalized ũ; from the historical point of view, the old -n has been retained in this position: gâyemūn-eĩ bečend “they picked almonds,” hormâvūn-am beraviahda bī “we had sold dates” and fīgūn-ayũ beraviahd “they sold the farmlands.”

While there is no gender distinction in definition marker, the definite singular noun is marked by the diminutive suffix -ū (contrary to -e and -a in Central languages and similar to -ū in Lori varieties and Fars languages). Khuri uses the same suffix -u as in mardu “the man,” which also serves as diminutive, and occurs with -ag as in sagag-ɔ˜ bedi “I saw the dog.”Footnote 32

The definite marker is also used when the noun has deictic adjective, but when the noun is followed by an attribute adjective, the definite marker is deleted:

As in colloquial Persian, the indefinite marker is -ī attached after indefinite singular and plural nouns. For indefinite singular nouns, ya “one” as the indefinite article comes before the noun: ya kočīkī “a sparrow” and ya bâγī “a garden.”

The possessive and attributive Ezafe that is characteristic of Persian and some other Western Iranian languages is not used with the noun ends in a vowel. Possessive complements and attributive adjectives regularly follow the noun that they modify without morphological marking: sərâ tε “your house,” a mâss “water of yogurt,” asse pâ “bone of foot,” sərâ katte “big house.” But after nouns ending in a consonant, Ezafe is frequently used: fâr-e mo “my sister,” siav-e suahr “red apple,” ya duahd-e kas “a small girl,” piahrōn-e espī “white shirts”; such nouns may appear without the Ezafe too: bâqh avũ “their garden,” ya sâʕat de “one hour later.” However, Borjian gives the Ezafe marker for nouns ending in both consonants and vowels: gol-e-suahr “red rose” and mā-ye-je “wife’s mother.” It is made more probable by the fact that Ezafe might not be authentically Farvi, and the influence of Persian on the languages in more recent times has established the Ezafe construction.

Adjective. The attributive adjective follows the noun it describes with or without using the Ezafe marker. The definite marker is deleted where an adjective follows the definite noun it modifies:

The comparative adjective is formed by the suffix -tar, but there is no superlative degree formed morphologically; as in colloquial Persian and other Iranian languages, the standard Persian superlative suffix -tarīn is not used in Farvi. The superlative degree is described by a form of the comparative degree combined with the plural noun or indefinite pronoun hama “all”:

PronounsPersonal pronouns

Independent personal pronouns distinguish two numbers (singular and plural) without overlapping in the third person with the deictic pronoun, thus distinguishing near and far deixis in plural third person as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Personal pronouns

The form of mā “I” and amo “we” recorded by Borjian are not recorded as this author’s material. The third person singular and plural are marked for human animacy, so that Farvi makes a distinction between human vs. inanimate by personal third person vs. demonstrative pronoun respectively: av “he/she,” em “this” (corresponding to Khuri ev “that” and em “this” also serving as third singular personal pronounFootnote 34), avũ “they (far),” emũ “they (near)” respectively vs. õ “that, it,” ânũ “those,” ĩ “this” and īnũ “these.” The following examples show the distinction:

There are six enclitic pronouns beside the independent forms (Table 2).

Table 2. Enclitic pronouns

It seems that the first person form -õ (also recorded as –ã)Footnote 35 comes from an older *-am by the deletion of final -m and nasalization of the former vowel (cf. Borgian: -a(m) for first singular enclitic). The original form might have been retained in the frozen form of fεm “myself” (see also Khuri -ɔm/-ɔ Footnote 36). For the third person singular -e (cf. Av. -hē) and plural -eĩ (also recorded as -aĩ and -ayũ, cf. Bojian -ayun), Farvi has the same forms as Kurdish -ī and -yān respectively.Footnote 37 The allomorph -yũ attested also in reflexive fεyũ “themselves” (see below) is also recorded in the author’s corpus:

Enclitic pronouns are used in a variety of oblique functions (possessive, and direct and indirect object and the agent of past transitive verbs in ergative construction): (1) possessive suffix, which is attached directly to the noun, or the phrase that it qualifies (15); (2) direct object (16); (3) indirect objects (17); and (4) agent of a past transitive verb. The enclitic pronoun may be suffixed to a noun, a verb, an adverb, an adjective or a pronoun:

Demonstrative pronoun. Farvi has a system of two demonstrative pronouns, near and far, as in Table 3.

Table 3. Demonstrative pronouns

Without pointing out the plural forms, Borjian refers to i(a) and em for near demonstratives. The form i(a) is not attested in the author data, but em is used only for animates (see above). Demonstrative pronouns are not used as third person personal pronouns (examples 20–21). Numbers are not distinguished in demonstrative adjectives; singular demonstratives are also used as deictic adjectives for plural nouns (examples 22–24):

Interrogative, reflexive and reciprocal. The interrogative pronouns are ke “who,” če “what,” and kayakī(g) “which”. They have the same form for singular and for the plural cases, yet there is a distinction between human vs. inanimate, that is, ke vs. če respectively:

For indefinite pronouns there is also a distinction between human vs. inanimate, that is, komī “someone” and čomī “something” respectively:

The reflexive pronoun fa/fe “self” has both emphatic and coreferential functions. It may appear separately (example 30), but normally takes the enclitic pronouns (examples 31–33). When acting as the agent of a past transitive verb, the corresponding enclitic may also be used before verb (examples 34-–35):

In Farvi, ham “each other” is used as a reciprocal pronoun:

Prepositions. Case relation may be expressed by prepositions alone. The corpus for the current study contains no example for postpositions and ambipositions. The following prepositions occur in Farvi:

he “from, to” is the most common preposition in Farvi, mainly used to express the ablative and indicates a starting point in the broadest sense of the word (examples 37–38); it is also used in the dative, where it has similar functions to Pers. be (example 39), and as a source or object of comparison (example 40):

bar “for” is used in the dative sense (corresponding to the Pers. barâye):

de “in,” as a general directional marker, is used to express the locative. It may also indicate motion “towards” or “location at”:

“where were you yesterday?”

bâ “with, by means of” (corresponding to the Pers. bâ) is commonly used in both instrument and accompaniment situations:

(v)a “to, toward”: the principal meaning of this preposition is to indicate the direction toward an object; va is used before words beginning with vowels:

rī “on, above” originally means “face,” extends semantically to a related position such as “upon, on, above” and indicates the location of something on the surface:

“the oil was poured on the ground”

tū “in”: corresponding to the Persian preposition tū, it expresses the meaning of inside:

There is no adposition (corresponding to Pers. râ) as a marker of direct object in Farvi:

The preposition da and (v)a are not included in Borjian’s list of Farvi’s prepositions (though he reported a as a preposition covering the lexical domain of Pers. be in Khuri, a ev head “give [it] to him”Footnote 38), and he refers to some other examples such as gar “by” and pi “in front of” not included in the author’s data.

Verb

Stem formation. As in other New West Iranian languages, the conjugation of verbs in Farvi is based on present and past stems of two types: the “irregular” verbs that have past stems ending in /-t/ or /-d/ and with no morphological relation between present and past stems; and “regular” verbs with past stems ending in -ây, or -ī where the present stem is formed by removing the suffixes.

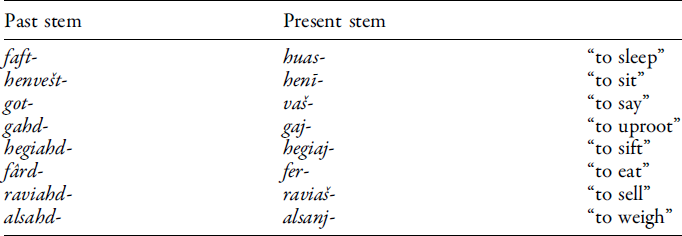

In irregular verbs, not of secondary formation, the present is derived from the OIr. present stems, and past stem from OIr. past participle in -ta. The past stem always ends in a dental stop -d after a vowel and a voiced consonant, and -t after voiceless consonants. Diachronically, the past stem is not a derivative of the present stem, nor is the present stem formed by removing the suffix of the past stem (Table 4).

Table 4. Irregular past stems

For some irregular past stems, the older final postvocalic d- has been changed to -y: ssay-/ssīn- “to buy” (<*stad-/stān-), and for some others it has been deleted: dī-/gīn- “to see” (<*dīd-< OIr. dīta-).

In some verbs where the old form of the past stem has been lost, a secondary form has arisen through the addition of -ī to the present stem: davī-/dav- “to smear” (instead of older *dūd-, <OIr. *dū-ta-, cf. Persian andūd- “to smear,” zadūd- “to polish, clean,” ālūd- “to soil”), algazī-/algaz- “to jump” (<instead of older *gašt-, frequently seen in Central as vašt-, cf. Pers. vazīd-). This can be regarded as an inherited feature Farvi shares with Southwestern languages.

In regular verbs, the past stem is a derivative of the present stem and is formed by adding the suffix -ây or -ī to the present stem. While -āy (cf. Prth. -ād) is a past formant in most Northwestern languages, -ī is typically Southwestern, and is most frequently found in Southwestern languages. Farvi makes a distinction between transitive and intransitive regular verbs in the formation of past and present stems.

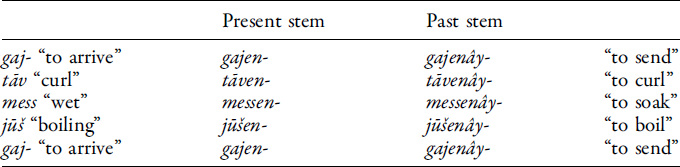

An intransitive regular stem is a denominative verb made freely from nouns and adjectives. The present stem is the noun or adjective that serves as the present stem, and the past stem is formed by the suffix -ây or -ī added to the present stem (Table 5).

Table 5. Intransitive regular stems

This includes those derived from the present stem of irregular verbs, where the old form of the past stem has been lost, and a secondary form has arisen through the addition of -ây or -ī to the present stem (Table 6).

Table 6. Intransitive regular stems

The transitive stem is formed by adding the suffix -en to intransitive present stems, nouns and adjectives, and the past stem is obtained by adding the suffix -ây to the present stem (Table 7).

Table 7. Transitive regular stems

Passive stem: Farvi also has the passive stem. The present stems are formed by adding the suffix -eh to the present stem of a transitive verb and the passive past stem is formed by adding -ây to the present passive stem (Table 8; see also below).

Table 8. Passsive stems

Endings. Farvi has two sets of endings: present endings which are attached to the present stems, and past endings which are attached to the forms with the past stems (Table 9).

Table 9. Personal endings

While the form -am comes before enclitic (cf. deginam-e “I see him”), -õ is used after stems ending in consonants: begīnõ “may I see” and befaftõ “I slept”; also, -hõ (with h- as hiatus deleter) is used with stems ending in a vowel: dedehõ “I give” and bešohõ “I went.” The same variation is found in the data quoted by Borjian for Khuri: dezunam, bezuniam “I know, I knew,” dehosān, befāftān “I sleep, I slept” and dezunān “I know.”Footnote 39 It also applied for the second person singular ending -ī or -hī:češnâsī “you know,” begotõhī “I said you (it was said to you by me),” and the third person plural past stem: befafton “they slept” and bešohon “they went.” For the second person plural ending, the form -d is used with stems ending in vowels and the form -ad with stems ending in consonants: tiyâd “you come” and deferad “you eat.” The first person plural is recorded by Borjian as -um (not attested in the author’s data). Set II of the endings (the same as the enclitic personal pronouns) proposed by Borjian for Khuri are not common in Farvi as represented in this author’s data, except for the case of zon- “to know” and gay- “to want” in the conditional past tense: agar dezonīa-mun “if we knew” and agar degay-õ “if I wanted.”

Imperative endings are singular -zero and plural -an: henī “sit!” seyl ke “look!,” beferan “eat ye!” and benahlan “do not let!”

Preverbs. The most frequently used preverbs are: he- and al-; he-(OIr. *fra-, corresponding to hâ- in Central and some Northwestern languages) without specified meaning is seen in verbs like henehâ-/hene- “to put,” hegiahd-/hegiaj- “to sift,” hedâ-/hedeh- “to give,” hegereft-/hegīr- “to take,” henvešt-/henīv- “to sit,” heriahd-/herīj- “to pour.” It changes to hī- with imperfects: hene “put!,” henvešta-hon “they have sat here,” âje-hatũ henahâ “you put there” vs. elū hīnvīm “here we sit,” ârd hīgiajan “they sift flour” and hīnjīne “they seat.” A similar form in Khuri is pointed out by Borjian as coalescence of he- with the imperfective morpheme de-: henešt![]() “I sat” vs. hīnešt

“I sat” vs. hīnešt![]() “I would sit”;Footnote 40 al- (Av. ərədwa, corresponding to âr- in Central languages) has a basic meaning of “upward, up” and is found in verbs like: algazī-/algaz- “to jump,” alsat-/alsanj- “to weigh,” algereft-/algīr- “to pick up,” algardī-/algard- “to return.”

“I would sit”;Footnote 40 al- (Av. ərədwa, corresponding to âr- in Central languages) has a basic meaning of “upward, up” and is found in verbs like: algazī-/algaz- “to jump,” alsat-/alsanj- “to weigh,” algereft-/algīr- “to pick up,” algardī-/algard- “to return.”

Morphological prefixes. The prefixes used in verbal conjugations are de-, be-, and negation and prohibitive na-/nā-:

1. The prefix de-is also found in the Northern and Northwestern branch of Central languages such as Vafsi, Ashtiani and Khansari,Footnote 41 and is also prominent in Northern varieties of Kurdish like Mukri.Footnote 42 As an imperfective marker, it is used in present imperfect and past imperfect. With present verbs, de- distinguishes the indicative from the subjunctive: deferad “you eat,” degaje “he is arriving” vs. bessīnan “may they buy,” beravešī “if you sell”; with past verbs, it distinguishes the past imperfect from the simple, perfect, past pluperfect and past subjunctive: defafton “they were sleeping,” šīm-ad defard “you were eating dinner” vs. befafton “they slept,” orzūntar-am beraviahd-e “we have sold cheaper,” befaftε bī “he had slept” and šīm-ayũ benafârda bū “maybe they did not eat dinner.” The prefix de- has remained as a frozen form t- in some verbs beginning in vowels: tarze “is worth” vs. biarzâ “was worth”; īzem-atũ he kū biavard? “where did you find the firewood?” vs. riavũ dešohon īzem-eĩ tiavard “they used to go and bring firewood in daytime” and natiašenan “they do not hear.” In the present indicative and imperfect the negation marker nā- replaces the imperfective marker de-: nāgeje “does not reach” and nātarse “he does not fear.”

2. be-: as an aspect marker it often appears to express completion of an event or the perfect aspect. It occurs normally in simple past, perfect and pluperfect: lobâs-eĩ bessay “they bought cloths,” šīm-õ benafârde “I have not eaten dinner,” pi-õ befaftɛ bī “my father had slept” and agar begaya bū “if he has arrived.” The prefix be- is also used with the imperative and subjunctive: beferan “eat! ye,” šâyad beraveš-e “maybe he sells” and agar siavũ befârda ban “if the apples were eaten.” It is normally dropped in prefixed verbs: ī kâr-am henakard “we did not do the work”; but contrary to de-, it remains with negation marker: benahlan “do not let” and benadia bī “I had not seen.”

3. na-/nā-: as a negation and prohibition marker, it comes before verbs, but contrary to the imperfect marker de-, the use of the negative does not preclude that of be-: nāčešnâsam-e “I do not know,” mon-eĩ benanī “they did not take me,” while in prefixed verbs nā- occurs between the prefix and stem of the verb ī kâr-am henakard “we did not do the work.” The form nā- is used with imperfect verbs: nātarsan “they don’t fear,” nāgeje “it doesn’t reach” (cf. Khuri na- vs. nē: benakarda “you didn’t do,” arnalo “don’t stand!,” henaniv

“that I do not sit,” nēkari “you don’t/won’t do” Borjian suggests that Khuri nē- is formed as a result of coalescing na- with the imperfective de-).Footnote 43

“that I do not sit,” nēkari “you don’t/won’t do” Borjian suggests that Khuri nē- is formed as a result of coalescing na- with the imperfective de-).Footnote 43

Tense, aspect and mood. The basic verb system has a double distinction of tense (present and past), three moods (indicative, imperative and subjunctive) and three aspects (imperfect, perfect and resultative) as follows:

1. Present indicative. The present indicative is marked by prefix de- and is used to indicate actions that are usually or always happening:

As there is no specific form for future tense in Farvi, the indicative present is also used to indicate actions in the future:

2. Present subjunctive. The present subjunctive is formed with the prefix be-, and in the main clause it is used to express suggestion or exhortation; it is also used in subordinate clauses:

3. Present progressive. The present indicative is also used to indicate ongoing and uncompleted actions, and the present progressive is generally expressed by the indicative present, but a form for progressive is based on the Persian model in affected speech, which is formed with the present conjugation of dīr-/der- “to have” followed by the present indicative of the main verb:

4. Imperative. The imperative is only used for the second person, singular and plural, and is formed with the present stem of the verb, the prefix be-, plus the personal imperative endings (cf. above), while prefixed verbs do not take the prefix be-; in the negative form, the prefix be- comes before the prohibitive prefix na-:

5. Simple past. Simple past is the perfective form of the verb system used for the past. It states that an action was performed in the past and is now complete, irrespective of its duration. In Farvi, simple past forms show a distinction between intransitive and transitive alignments. The intransitive is formed from the past stem with the prefix be- and past personal endings, while prefixed verbs do not take the prefix be-:

The transitive verbs are conjugated ergatively and do not generally use personal endings; the agent appears mostly as enclitic pronouns before the verb and attaches to any word other than the verb:

Only with the verbs zonī- “to know” and dâšt- “to have” (as past progressive marker) does the enclitic agent appear after the verb. This form is also seen in some other Central languages (cf. Jowshaqani: dard-edun du-sāt “you were making”):Footnote 44

6. Past imperfect. As the general past imperfective is formed like the present indicative, it may refer to events that were constantly taking place or took place over a definite period of time in the past. It is formed like the simple past, except that it has the prefix de- instead of be-:

Like other past transitive forms, imperfect in transitive verbs are conjugated ergatively and do not generally use personal endings:

7. Present perfect. The present perfect of intransitive verbs are formed with the past participle of the main verb ending in -a or -e followed by the enclitic copula form of the verb “to be.” The prefix be- as the perfect marker also precedes the past participle form, while the use of verbal prefix precludes that of be-:

The transitive perfect has an ergative form and is formed with the past participle without copula:

8. Past perfect. The past perfect of transitive verbs are formed with the past participle of the main verb followed by an inflected past form of “to be.” The prefix be- as the perfect marker also precedes the past participle form:

The transitive pluperfect is conjugated ergatively and consists of the participle of the verb, with the prefix be- and the third person singular simple past of “to be” (bī “was”); as an enclitic pronoun, the agent comes before the verb:

9. Perfect subjunctive. There is a form for past subjunctive that may be affected by the Persian model and is formed with a past participle with the prefix be-, plus the subjunctive of b- “to be.” It is primarily used to express unreal conditional and unrealizable past wishes:

Like other forms of past transitive verbs, the transitive past subjunctive is conjugated ergatively:

10. Past progressive. The past progressive is formed with the past conjugation of dâšt- “to have” followed by the imperfect of the main verb. As there is no genuine verb for “to have” in Farvi,Footnote 45 it seems that dâšt- in Farvi maybe a loanword from Persian and the Persian model of the past progressive is used. The progressive past is used to indicate an uncompleted situation to occur at a period of time in the past. As it appears in the examples, the past of dâšt- is conjugated ergatively and the enclitic pronoun as the agent typically attaches after the verb. The patterns used in some other Central languages have been noted by Windfuhr as “raising” a personal affix.Footnote 46

Ergative. Like all the Central languages, Farvi has retained a form of the so-called split ergative which shows ergative verb agreement. This indicates that originally the endings of transitive past verbs agreed with the object, not the agent. However, this form of agreement has largely been lost and in past transitive verb forms, instead of a verb ending, the enclitic pronoun and/or noun is placed before the verb as agent. This is used for all verb forms conjugated based on the past stem:

Still there are some forms showing that verbs may take an ending which is in agreement with the object:

The agreement is also shown by zero ending of third person singular when the verb has a singular object used in the sentence:

The agreement has also been recorded in some other Central languages, e.g. Meymayi: kia da bar-ešūn kardī “they turned you out of the house,” bī-m bevotī ge abī ūna nāše “I told you that he couldn't go there.”Footnote 47 The agential enclitic pronouns are generally suffixed to the direct object, but may attach to the other constituents:

Passive. Passive is most commonly expressed by a passive stem that is formed by the suffix -eh (from Mid. Ir. -īh- <OIr. -ya-; also found in some Lori languages) to the present stem of a transitive verbs.Footnote 48 The past passive stem is then formed by adding -ây to the present passive stem (see also above): fer-/fârd- “to eat” >fereh-/ferehây- “to be eaten,” gīn-/dī- “to see” >gīneh-/gīnehây- “to be seen,” pej-/pahd- “to cook” >pejeh-/pejehây- “to be cooked,” (he)rīj-/(he)riahd- “to pour” >(he)rījeh-/(he)rījehây- “to be poured.” The passive is conjugated as an intransitive verb in all tenses, aspects and modes:

The passive may be formed by means of periphrastic constructions similar to Persian. This kind of passive is formed by the combination of the past participle with the corresponding finite form of the auxiliary verb bo “to become”:

More Southwestern and Southeastern Isoglosses

As discussed above, Farvi regularly has shared phonological and morphological features with Southwestern, Kurdish and Balochi and in later changes with Southeastern languages. Consulting the lexicon, we find a number of pieces of lexical evidence showing more isoglosses.

Farvi has these lexical elements in common with Southwestern languages: mošk “mouse” (cf. Bakhtiari, Boirahmadi and Bashgardi mošk from PIr. *muHs-ka- with loss of laryngeal without compensatory lengthening, as against mūš from PIr. *muHs- with loss of laryngeal and compensatory lengthening); sose “lung” (cf. Bakhtiari and Boirahmadi sos, from OIr. *suši-, the progressive assimilation is only seen in Lori languages); hezũ “tongue” from OP hazāna-;Footnote 49 gam “mouth, opening” (cf. Bakhtiari and Boirahmadi gam “nibble”); pīl “bridge” (from older pūl<*puhl) versus pard and the like in some Northwestern languages; gerī “weeping” versus berma and the like in Central and most Northwestern languages; ssay-/ssīn- “to buy” versus herī-/herīn- “to buy” and the like in most Northwestern languages. The suffix -iang in words like noviang “salt,” galiang “necklace” and maybe niang “hen” is common in Southwestern languages (cf. Bakhtiari havang “metal mortar,” nezeng “near”). The same applies to the diminutive suffix -ešk in words like miarešk “ant,” which is also more common in Lori languages (cf. Boirahmadi marmarūšk “small salamander,” parparūšk “butterfly,” sēsēyūšk “a tiny black thing”).Footnote 50

Retention of Middle Iranian final postvocalic -g (from OIr. suffixal -ka) is a common phenomenon among Southeastern Iranian languages such as Balochi, Northern Bashgardi and Kumzari,Footnote 51 probably the result of language contact in the region. In Farvi, OIr. suffixal -ka has remained as -g: dong “seed,” ruâsg “fox,” dâsg “sickle,” nāfg “navel,” tarâsg “balance,” nâg “nose” (<*nāh-ka, cf. OP nāh-), tafg “a kind of bread baked on pan,” kerg “fireplace,” âyeng “mirror,” kīsg “haversack.” These exemplify the common usage in Farvi of -g- as intervocalic connector. A similar feature for Khuri is pointed out by Borjian as an extra velar stop added to the final sonorant, a process he calls “velarization of final consonant.” But there are some problems with the examples for Khuri given by Borjian. Some words have a suffixal -ešk: čerešk “chick” (cf. Farvi čerīk, Central languages čuri “chick”), mērešk “ant” (cf. Pers, mur “ant”); some others seem to have a suffixal -eng: galeng “necklace” (Pers. gal “hanging”?), nenang “hen” (<nana “mother”?).

The sound change of OIr. *x-> Farvi k- in words like kong “laugh” and nâko “nail” is also shared by Balochi (cf. kandag “laugh,” nākun “nail”), which shows another agreement between Farvi and Balochi; similar examples are found in Khuri: kerus “rooster,” kuruj “rabbit,” kohnion “to laugh,” nokon/nākon “fingernail.”Footnote 52 Some other lexical isoglosses like pemâz “onion,” gīsa “female goat,” giahnīj “coriander,” čerīk “chick,” gaš- “to say” (cf. Balochi pīmāz, gwask/gēs, genīč, čōrīg, gwaš- respectively) show more agreement with Balochi.

Conclusion

The fact that some of the Southwestern features have been taken over by Farvi (and also by Balochi and Kurdish) shows that Farvi, Balochi and Kurdish have been influenced by Persian since Old Iranian times. In contrast to Kurdish and Balochi, Farvi with more Southwestern features shows more contact with Persian or Southwestern languages in Old and Middle Iranian times.

On the position of Farvi among Western Iranian languages, looking at historical phonology and some morphological and lexical features shows that Farvi, though basically Northwestern, shares a set of old isoglosses with Southwestern languages that place Farvi beside Kurdish and Balochi as a transitional language among Western Iranian languages. These agreements also give some idea of a common origin of Farvi with Balochi and Kurdish, where all of the three languages have apparently separated from the rest of the Northwestern languages earlier than other languages. In later changes, Farvi also shares some areal features that relate it with Southeastern Iranian languages such as Northern Bashgardi and Balochi. These isoglosses could therefore be regarded as less old than the Northwestern and Southwestern features discussed above. The lexicon of Farvi contains many old lexemes not attested in other Iranian languages, and in later changes show many sound changes that are unique among New Western Iranian languages.

More Farvi words not attested in the text:

ajia “glaire,” appây-/appâ- “to stand,” arzâ-/arz- “to be worth,” avesk “sleeve,” āvard-/āvar- “to bring,” bard-/bar- “to carry,” biard-/biar- “to cut,” čend-/čen- “to pick,” čerīk “chicken,” češnâxt-/češnâs- “to recognize, to know,” dand “wasp,” duahd-/dūš- “to milk,” ezo “such, this way,” fele “foremilk,” gaft-/gāf- “to weave,” galiang “necklace,” ganvaš “blossom of wild pistachio,” gare “lamb,” gay-/gaj- “to arrive, to come,” gay-/gū- “to want,” gâlī “wart,” gârī-/gâr- “to rain,” gâzī “game,” gerīv-/gerv- “to weep,” geriahd-/gerīj- “to flee,” giard-/gīr- “to pass,” giūz “walnut,” gorvang “cotton boll,” haftia “seventy,” henjond-/henjīn- “to seat,” hejar “fig,” hešt-/hal- “to let,” jīrg “caraway,” kerg “tandoor, oven,” kond-/kon- “to throw,” koss-/kot- “to pound,” kotre “pup,” kowčīz “ladle, kuahr “kid, young goat,” lūš “mud,” mard-/mer- “to die,” maske “butter,” mazge “mosque,” messehây-/messeh- “to get wet,” mīv “hair,” mog “date palm,” mōjū “bitter wild almond,” momojū “lizard,” mond-/mīn- “to stay,” mua “height, hill,” našg “beak, neb,” nâzūg “cat,” ošnū “sneeze,” pālve “jacket or trouser pocket,” pahd-/pej- “to cook,” parg “niche,” paz “algae,” pesgarū “swallow,” pešnū “forehead,” piarehī “two days ago,” pīn “dried whey,” pīšg “date kernel,” ravo “oil,” ruahd-/rū- “to sweep,” rūs “bark of wild almond using for dyeing,” sa “three,” šīlam “turnip,” sīsk “beetle,” šī “bottom,” suak “bucket,” škass-/škeh- “to break,” šo-/šū- “to go,” tafg “a kind of bread,” tarrū “wet, moist,” tohorū “cuckoo” vasīrg “the flour of unripe barley,” xâ “soil,” zerũ “knee,” zog “abdomen.”

Sample text

1. deguõ bar šomā čan marâsem-e farvī degašõ. marâsem-e xaš-kardõ: ĩ marâsem jašn-e šorū-e kešt-e pâizag-ĩ vo doyyem-e Mordad tū kešũ anjâm degere ba čâbošia vo fondon-e qhōrũ. gavar-e ahâlī īn-ĩ ke vaqtī sâɁat xaš dekaran, kamar gormâ deškehe vo ā siā vo zard debū, yānī ā xonok debū. bânī-e xaš kardõ degu xaš-dass buyī, be estelâh-e mahalīgũ dass-e suak buyī. pīštar nūnī ke estefâdag-eĩ dekarda tū ĩ marâsem, nūn mohalī bâ revan-e xaš bia-g-ĩ. amâ hemī nūn nūnvâyī-a bâ mīvagūn-e tāvessūnī ke ziyâdtar hendūnag-ĩ.

2. ziâdtar-e hâzerũ tū ĩ marâsem tū ā-yahdõ vo toxmkâria komak dekeran. ī marâsem âyīnīg-ĩ bâ fondon-e qhōrūn o čâbošia hamrah-ĩ. afrâd-e kemnī doguan ke bânī-e ī marâsem beban. ī marâsem maxsūs-e keštan-e jā vo gonnam-ĩ. čomūn-e de mesl-e šīlam hõ dekīran.

3. marâsem-e de ke rasm biag-ĩ , marâsem-e nūn-e bībīhūr biag-ĩ ke šav-e gist o haftom meh ruaja anjâm degerefte. mardam mōtaqhed bia-hõ ke ī bībīhūr be nūn-e mardam barakat dedehe vo tū šā gist o haft meh ruaja tanīr sərâvūn tū sobahī garm gūj dedâšte. mōtaqhed bia-hõ bībīhur te vo be ĩ tanīr sar dekote vo bâ assây âyar-e tanīrūn garm gūj dedīre, be nūn-e ī tanīrūn barakat hedehe. sabah-e zī jenū tū ī tanīrūn nūn-eĩ depahde beyn dūssūn o hamsâyagūn taqsīm-eĩ dekarde. ya zarrag-eĩ hõ bar feyũ gūj dedâšte. alāve he ĩ hõ mōtaqhed bia-hõ tanīrūnī ke tū ī šā garm nahon, he barakat-e ī bībīhūr be diar hon. ī kâr tū rī-e âxar sâl hõ tū bāzī jâgūn-e mantaqhe-ye biâbūnak biag-ĩ. yāni rī gīst o nohem-e esfand hõ anjâm degerfte.

4. âš-e pešt-e pâ: baɂīd-ĩ komī bešia hame âšūn o dalīl-e pahdon-e õ barrasia kõ vo bešmâre. har kīča vo har mohalla ya âš depeje. tū mohallag-ĩ amā hõ hamīn-ĩ. amā hõ nāzonīm ke râbete-ye âš bâ xodahafezia če-ĩ. amā tū har marâsemī ke boguam ajâge kerīm yâ har komī bogue he jām amā xodâhâfezia kõ be safar šū , âxar har barnâmag-am bâ âš-ĩ. hamĩ ke doguam be miahmūnūn begašīm ke de dešâd zahmat miahmũ biõ he rī kual amâ algerad, âš depejīm o ezõ jām-amũ parâkende debū.

5. yakī he vaqtūn-e de ke amā âš depejīm âxer-e meh ruajag-ĩ. hamĩ ke meh ruaje âxer debū vo amā bād a ya mah miahmūn-e xodâ biõ dogvam jām-am parâkenda kerīm o ī miahmūnagia tark karīm âš depejīm , âš-e pešt-e pâ-ye meh ruaje. har mazge vo sərāyī jenũ tū meh ruaje bar qhōrũ fondõ dār ham jām debia- hon. rĩ ɂīd-e ruaje ke ĩ mah ajâ debū âš depejan har komī ya čomī tiavo vo harkī dogve te âš hegere. yâ hamõ je eyfo yâ zarfī tiavo be sərâ debo. be omīd-e ĩ ke be ruaje-ye sâl de begajan, eyferan.

1. I want to talk about some Farvi customs. The custom of delight-doing. This custom is the feast of autumnal farming celebrated in farmlands at the second half of Mordad (August) with chanting and reading the Quran. The belief of the local inhabitants is that when they do delight, the waistline of heat is broken (heat begin to reduce) and water becomes black and yellow. The celebrant of delight-doing should be good-handed. According to the local people, his hand should be light (easing the tasks). Formerly, the bread that they have used in this custom has been a local type with domestic delicious oil, but now it is the bakery bread with some summer fruits which is mostly watermelon.

2. Most of the participants in this custom help [the celebrant] in irrigating and sowing. This custom is ritual and is accompanied by chanting and reading of Quran. There are just a few men who want to be the celebrant of this custom. This custom is related to barley and wheat sowing. Some other things like turnip they also sow.

3. The other custom that has been customary has been Bibihur that was celebrated on the 27th of Ramadan month. The people believe that this Bibihur gives abundance to the bread of people’s clay oven, and keep warm the oven of houses on the 27th of Ramadan. They believe that Bibihur comes and visits and keeps warm the fire of oven with her cane, and gives abundance to the bread of ovens. In the early morning, women baked in these ovens and apportioned the bread among their friends and neighbors. A little bit they kept for themselves. Furthermore, they believed that the ovens that are not warm in this night are removed away from the abundance of Bibihur. It has also been practiced in the last day of year in some locations in Biabanak region. It means that it was also celebrated on 29th of Esfand (19 March).

4. The sending of the pottage of Ramadan: it is unlikely that someone can consider and enumerate all the pottage and the reason for cooking it. In each alley and quarter [of Farvi], a kind of pottage is cooked, which holds in our quarter too. The relationship between pottage and farewell is yet unknown. When someone wants to bid farewell or to travel, a pottage is cooked at the end of a ceremony. When we want to say our guest that you can take off our shoulders the difficulty of guest inviting, we cook pottage, and this way we disrupt our party.

5. The other time that we cook pottage is the end of Ramadan. When Ramadan ends, and after one month to be the guest of God, we want to disrupt our party and leave the party, we cook a pottage: the send-off pottage of Ramadan. In the feast of Ramadan when the month ends, they cook pottage. Everybody brings something and anyone is welcome to take the pottage. They eat there or bring a dish and take it home to eat in the hope that they arrive at the Ramadan feast of the next year and eat again.