1 Introduction

It is estimated that around one quarter of the world's languages have a grammatical evidential system (Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald2004: 30), but despite a recent, growing interest, evidentiality remains under-researched because it does not seem to concern Indo- European languages. Although most studies on evidentiality have focused on so-called ‘evidential languages’ (Chafe & Nichols Reference Chafe, Chafe and Nichols1986; Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald2004, Reference Aikhenvald2018), evidentiality is in fact a universal semantic domain that leaves a functional gap in languages lacking a grammatical paradigm for it (Boye & Harder Reference Boye and Harder2009). One might thus wonder how relevant the notion of evidentiality is for a language such as English.

The majority of studies that deal with Indo-European languages use a different definition of evidentiality than the prevailing one in linguistic typology, and many focus on pragmatics rather than on semantics (Fox Reference Fox2001; Precht Reference Precht2003; Alonso-Almeida & Cruz-García Reference Alonso-Almeida and Cruz-García2011). Other studies on Indo-European languages do use a stricter definition of evidentiality, closer to the one adopted in typological studies, and show how the notion can also apply to the linguistic forms of languages that are usually considered ‘non-evidential’ (Squartini Reference Squartini2007; Cornillie Reference Cornillie2007; Diewald & Smirnova Reference Diewald and Smirnova2010).

Several studies refer to evidentiality in English, but scholars disagree on what an evidential is. Chafe (Reference Chafe, Chafe and Nichols1986) investigates English evidentials in academic writing, and considers any linguistic form relating to knowledge to be ‘evidential’, whether it expresses ‘reliability’, such as certainly, ‘mode of knowledge’, such as in my opinion, or ‘expectation’, such as actually. Nuyts (Reference Nuyts2001: 25–8) uses the notion of evidentiality to distinguish between a subjective and an intersubjective epistemic evaluation. Gisborne & Holmes (Reference Gisborne and Holmes2007) refer to what Palmer calls the two kinds of ‘evidential modality’: ‘reported’ and ‘sensory-perceptual’ (Palmer Reference Palmer2001: 35–52). They explore the diachronic developments of English verbs of appearance, such as seem, and Aijmer (Reference Aijmer2009) provides further details on their evidential functions. Whitt (Reference Whitt2009, Reference Whitt2010, Reference Whitt2011) describes English perception verbs, and includes stance, (inter)subjectivity, as well as ‘generalized observation, inference, knowledge and understanding’ as part of evidentiality. Brinton (Reference Brinton1996: 211–64) provides a diachronic and synchronic description of phrases like I guess, which she calls ‘epistemic parentheticals’, focusing on their pragmatic functions. In Brinton (Reference Brinton2017: 132–4), she further explores the interaction and overlap between epistemic and evidential parentheticals. Finally, López-Couso & Méndez-Naya (Reference López-Couso and Méndez-Naya2014) describe the evolution of epistemic/evidential parentheticals, such as seem/appear/look/sound like, without distinguishing the epistemic and evidential domains explicitly. The vast majority of these studies posit that English expresses evidentiality lexically, but a few do suggest signs of early grammaticalization for some specific phrases (Aijmer Reference Aijmer2009; Whitt Reference Whitt2009; López-Couso & Méndez-Naya Reference López-Couso and Méndez-Naya2014).

Adopting a definition similar to that used in typological research, I intend to examine the rendering of evidentiality in English, and investigate whether the language possesses grammatical evidentials. The article is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the definitions of evidentiality and grammaticalization. Section 3 introduces the methodology I used to collect a corpus and determine what can be counted as an evidential. Section 4 presents the data that lead me to argue that a significant grammaticalization of evidentiality is attested in English. Section 5 discusses the main findings and examines to what extent evidentiality is relevant in English. Finally, section 6 concludes the study, and offers suggestions for further research.

2 Discussions on evidentiality and grammaticalization

2.1 How to define evidentiality

As is the case for many notions in linguistics, scholars have not reached full consensus on the definition of evidentiality. The dominant definition, and the one adopted in Aikhenvald (Reference Aikhenvald2004, Reference Aikhenvald2018), is ‘the grammatical marking of information source’. Other scholars argue that evidentiality should not be limited to grammatical marking but also refers to lexical marking. For methodological purposes, I have chosen not to restrict evidentiality to its grammatical expression. The degree of grammaticality of English evidentials can only be assessed after listing the different tools available in English to encode evidential meaning without rejecting any marker because of its supposed lexical status.

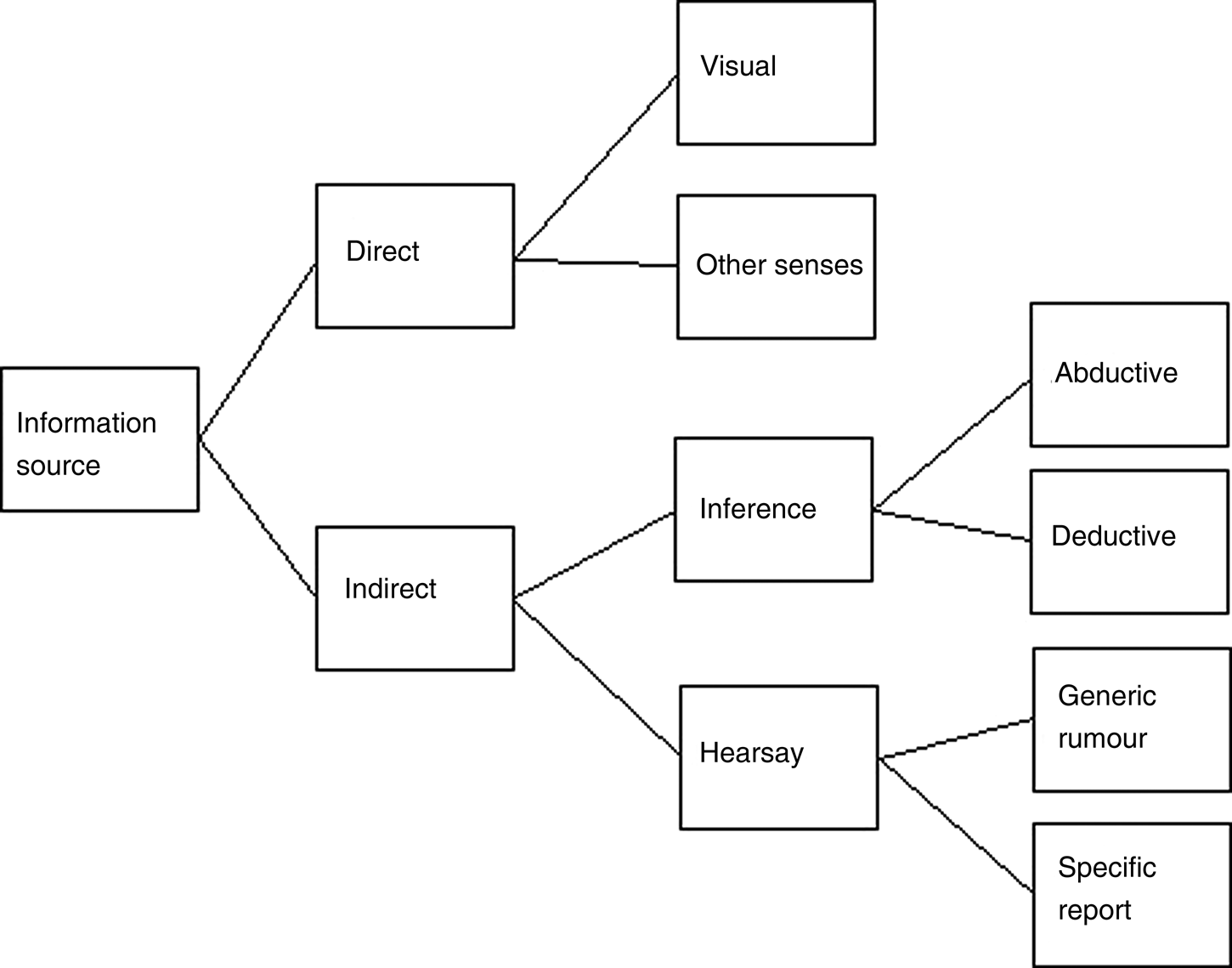

For evidentiality to be relevant from a semantic point of view, the frontiers of its domain have to be clearly defined to distinguish it from neighbouring notions, such as epistemic modality, subjectivity, stance or mirativity. The literature on linguistic typology reveals that evidentials can be divided into three main categories: direct perception, inference and hearsay. These categories can be further subdivided, since direct perception may be visual, or involve other senses, an inference can be abductive, i.e. based on observations, or deductive, i.e. based on logic, and hearsay can refer to a general rumour, or a first-hand report, etc. Figure 1 presents a taxonomy of evidential categories.Footnote 2

Figure 1. A taxonomy of evidential categories

What all categories of evidential markers have in common is indeed that each of them refers to a specific type of information source, i.e. they specify in what way the information that is being shared has been accessed. I am thus adopting a morphologically open and semantically strict definition of evidentiality (see notably Schenner Reference Schenner2010): the linguistic expression of the source of the information shared by the speaker.

2.2 Evidentiality as a universal semantic notion

According to Aikhenvald (Reference Aikhenvald2004, Reference Aikhenvald2007, Reference Aikhenvald2018), evidentiality should be used only for ‘evidential languages’ that possess grammatical morphemes dedicated to the expression of information source. She argues that using a broader definition challenges terminological clarity, and that languages which have not fully grammaticalized the notion simply resort to lexical ‘evidential strategies’ (Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald2007). While it is true that evidentiality is far more grammaticalized in some languages than in others, seeing evidentiality as a universal semantic notion presents clear heuristic advantages (Squartini Reference Squartini2007; Cornillie Reference Cornillie2007; Cornillie et al. Reference Cornillie, Marín Arrese and Wiemer2015).

First, research on grammaticalization has shown that no criterion suffices in determining what is lexical and what is grammatical in a language, and that linguistic forms tend to be located at different places on a continuum between those two poles depending on the selected parameter (Newmeyer Reference Newmeyer2000; Campbell Reference Campbell2000; Brinton & Traugott Reference Brinton and Traugott2005: 89–110).

Secondly, considering some languages to be ‘evidential’ because they possess ‘evidential grammatical morphemes’ is disputable in many respects. First of all, it can be misleading to use a semantic term to refer to morphological or syntactic phenomena, since linguistic forms are generally used for a diversity of semantic functions. For example, traditional grammar calls would a ‘modal’, but this vaguely semantic name fails to capture its other functions, such as the expression of the iterative aspect. So-called ‘evidential morphemes’ of ‘evidential languages’ are also generally multifunctional, and are often exploited to express other notions, such as person, time, aspectuality, realis/irrealis modality, epistemic modality, passive voice or mirativity (see Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald2004: 105–52, 195–216). In addition, languages that are often considered ‘non-evidential’ do possess grammatical morphemes with evidential meanings. The French conditional inflection can, for example, express hearsay evidentiality (Dendale Reference Dendale and Hitty1993), and an increasing number of papers also describe grammatical or semi-grammatical evidential forms in languages such as Spanish, or English (Cornillie Reference Cornillie2007; Whitt Reference Whitt2010; Cornillie et al. Reference Cornillie, Marín Arrese and Wiemer2015; Guentchéva Reference Guentchéva2018, inter alia). These reflections lead us to question whether it remains relevant to maintain a typological taxonomy with, on the one hand, ‘evidential languages’ and, on the other hand, ‘non-evidential languages’.

Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 115) advocate a clear distinction between forms (tense, aspect, mood) and their semantic counterparts (time, aspectuality, modality). From this perspective, terminological clarity would encourage us to use the -ity variant for the semantic notion that can be rendered through the lexicon or the grammar of a language, and not for the forms themselves. Although English does not possess an inflectional mood system which is as developed as what can be found in a language like French, no linguist would argue that English does not express modality at all. Similarly, some languages may possess a developed system of evidential inflections, but languages without such inflections may still encode evidentiality.

To sum up, I argue that evidentiality can be defined as a universal semantic domain that is encoded by a variety of linguistic forms, as is the case for time, aspectuality or modality. In this article I will further argue that evidentiality is one of the few notions that tend to attract forms towards the grammatical end of the lexicon–grammar continuum, and that there is evidence of this force of attraction in English.

2.3 Why is evidentiality different from epistemic modality?

Scholars have dealt with the relationship between evidentiality and epistemic modality quite differently. Cornillie (Reference Cornillie2009), Whitt (Reference Whitt2010) and Boye (Reference Boye2010b) give an overview of the diverse treatments of the two notions. It is, however, difficult to determine whether the debate is really ontological, or rather terminological, since authors use diverse definitions for the two notions. The dominant view nowadays is that evidentiality and epistemic modality have to be treated separately, even though some forms may express both. It is indeed possible to express evidentiality, i.e. the information source underlying a proposition, without expressing epistemic modality, i.e. the degree of likelihood of a proposition.

Unlike evidentiality, epistemic modality has been integrated in the grammatical description of English for decades (Perkins Reference Perkins1983; Traugott Reference Traugott1989; Bybee & Fleischman Reference Bybee and Fleischman1995; Nuyts Reference Nuyts2001; Palmer Reference Palmer2001, Reference Palmer2014; Boye Reference Boye2012). In the conceptual index of the Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (Huddleston & Pullum et al. Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002), the epistemic modality entry refers to seventeen sections, in striking contrast to evidentiality, which does not appear. In more recent reference grammars, such as the Oxford Modern English Grammar (Aarts Reference Aarts2011), as well as in the Oxford Handbook of English Grammar (Aarts et al. Reference Aarts, Bowie and Popova2020), evidentiality is not mentioned either. However, as the present article argues, a close examination of the data reveals that evidentiality is as pervasive and grammaticalized in English as epistemic modality. The reason why the former is barely evoked in grammar books is merely historical, and will be argued to stem from a conceptual confusion between the two semantic domains. Due to the frequent conflation between the two notions, many grammatical or semi-grammatical forms of English have been labelled ‘epistemic’, while they are sometimes both epistemic and evidential, or even sometimes only evidential. It is, for example, widely accepted to talk about the epistemic use of the auxiliary must in a sentence such as:

(1) She must have been wearing a black dress yesterday.

I would argue, however, that this use of must is not just epistemic, but also evidential. One can thus compare:

(2) I'm trying to remember … I think she was wearing a black dress yesterday.

(3) Let me guess … She always wears a black dress at parties, so she must have been wearing a black dress yesterday.

In example (2), the speaker's uncertainty is due to the vagueness of his/her memory of a situation that he/she directly witnessed, which is a suitable context to use I think. Conversely, in example (3), the speaker's uncertainty is caused by the fact that he/she did not witness the situation, but is just inferring what happened. This context will favour the use of must. These examples show that the choice between I think and must depends on the speaker's information source. Even though this use of must is traditionally called ‘epistemic’, it could equally be called ‘evidential’, since must is avoided when the speaker's statement is not based on an inference.

Other forms denote either epistemic modality or evidentiality, but not both. An adverb like maybe or a matrix clause like I doubt that… expresses epistemic modality, but do not indicate the speaker's information source. Conversely, constructions such as Vegetables taste bland nowadays or I saw that he had eaten the cake are evidential, but not epistemic. They specify how the speaker knows what he/she is saying, but do not question the validity of the proposition they modify.

Now that I have discussed what defines evidentiality, and before investigating whether evidentiality has indeed grammaticalized in English, I still need to specify what signs indicate grammaticalization.

2.4 How to define and assess grammaticalization

Kuryłowicz (Reference Kuryłowicz1975 [1965]) defines grammaticalization as the transition of an autonomous word to a grammatical form, or the movement from a less grammatical status to a more grammatical status. As linguistic forms grammaticalize, they progress on a continuum by losing lexical properties and acquiring grammatical features. With very few exceptions, this process happens by a gradual series of individual shifts (Plank Reference Plank and Pantaleon1989; Lichtenberk Reference Lichtenberk1991; see also Traugott & Trousdale Reference Traugott and Trousdale2010), and in a unidirectional fashion (Lehmann Reference Lehmann1995 [1982]: 16; Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath2004; Börjars & Vincent Reference Börjars, Vincent, Narrog and Heine2011).

If one sees lexicon and grammar as two poles, there should be signs that enable us to measure where a linguistic form is located on this continuum. For that purpose, the publication of Lehmann's parameters (Lehmann Reference Lehmann1995 [1982]: 121–78) was a milestone in the establishment of the main criteria for diagnosing the degree of grammaticality of a form. The parameters proposed by Lehmann are integrity, paradigmaticity, paradigmatic variability, structural scope, bondedness and syntagmatic variability.

These criteria correspond to diachronic processes that linguistic forms usually undergo when they are grammaticalizing. In order to illustrate these processes, let us consider one of the most cited cases of grammaticalization, namely the development of the French future chanterai ‘sing:FUT 1SG’ from the late Latin cantare habeo ‘sing:INF + have:PRES 1SG’:

i. Three processes correspond to a reduction of a form's integrity:

a. Phonological attrition, i.e. the partial loss or simplification of the pronunciation: habeo > -ai;

b. Desemanticization, i.e. the loss of concrete semantic features: possession > deontic modality > future;

c. Decategorialization, i.e. the loss of lexical morpho-syntactic properties: a verb with mood/tense/person inflections > a future inflection with person agreement;

ii. Paradigmaticization corresponds to an increase of a form's paradigmaticity,

i.e. its inclusion in a closed set: a verb replaceable by thousands of other verbs > an inflection in the closed paradigm of the French conjugation system;

iii. Obligatorification corresponds to a decline of a form's paradigmatic variability, i.e. if the form is deleted, the sentence becomes ungrammatical: an optional verb > an obligatory inflection (* je chanter ‘I sing’);

iv. Condensation corresponds to a contraction of a form's structural scope: a verb whose syntactic scope can be a large phrase > an inflection whose syntactic scope is limited to its host verb;

v. Coalescence corresponds to a tightening of a form's bondedness to its host: cantare + habeo > chante-r-ai;

vi. Fixation corresponds to a restraint on the syntagmatic variability of a form: a moveable verb > an inflection that must follow its host.

Most works on grammaticalization refer to quite similar criteria, even though certain authors may leave some out, and others may add one or two (Wiemer & Bisang Reference Wiemer, Bisang, Bisang, Himmelmann and Wiemer2004; Brinton & Traugott Reference Brinton and Traugott2005: 89–110; Norde Reference Norde, Cornillie and Cuyckens2012; Kuteva et al. Reference Kuteva, Heine, Hong, Long, Narrog and Rhee2019: 1–22). Norde (Reference Norde, Cornillie and Cuyckens2012) points out that Lehmann's taxonomy is not perfect, because some parameters have proven to be of little use to distinguish grammaticalization from other types of language change. I would argue that some of these parameters are indeed more relevant than others, and I have chosen to focus on only five processes that are particularly applicable for the present study: morphophonological reduction, desemanticization, backgrounding, decategorialization and paradigmatization. In section 4, I will define more precisely each of the five processes selected, and give concrete examples.

There are several reasons why I consider processes such as obligatorification, condensation, coalescence and fixation to be outside the scope of this study.Footnote 3 Obligatorification is problematic to measure because there are many types of syntactic, semantic or pragmatic obligatoriness (Mélac Reference Mélac and Hancil2018). Nothing is obligatory all the time in a language, and context plays a crucial role. Obligatorification is not necessary when a form grammaticalizes, and is attested in other kinds of linguistic changes (Heine & Kuteva Reference Heine and Kuteva2007: 34). Moreover, although Aikhenvald (Reference Aikhenvald2007) stated that obligatoriness was a necessary factor to identify a grammatical evidential, she then retracted that claim, because many evidential inflections and clitics are perfectly deletable (Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald2018: 10). In Tibetan, for example, evidential inflections and copulas are obligatory in the sense that deleting them when they appear in a matrix clause would usually make the sentence ungrammatical. However, from a semantic point of view, they can be substituted by other inflections and copulas that do not contain any inherent evidential feature. Tibetan evidential enclitics are syntactically optional, but they are often quasi-obligatory from a pragmatic point of view, and are usually considered fully grammatical.Footnote 4

Condensation is also a controversial process, since syntactic scope expansion is very often attested for grammaticalizing forms (see Norde Reference Norde2009: 126). For example, the conjunction supposing saw its scope expand to the clause level as it grammaticalized from a lexical verb (Visconti Reference Visconti2004). As far as evidentials are concerned, the potential scope of the Tibetan enclitic -ze is larger than the scope of the lexical verb zer (‘say’), from which it nevertheless grammaticalized, just like the English adverb apparently saw its scope expand when it became a sentence adverb with an evidential meaning.

Coalescence may be a noticeable process for several forms becoming more grammatical, but it is not a very reliable symptom of grammaticalization. Prepositions, such as off, auxiliaries, such as may, or determiners, such as this, have not undergone any coalescence even though they are fully grammatical. In addition, coalescence is very often involved in other types of language change, such as lexicalization. Brinton & Traugott (Reference Brinton and Traugott2005: 63–7) cite numerous examples of lexical forms that result from a process of coalescence. In English, one can think of the words ma'am, which comes from the Old French ma dame (‘my lady’), or England from Old English Engla land (Oxford English Dictionary (OED)).

Finally, fixation is also a problematic criterion for identifying an instance of grammaticalization. As argued in Brinton & Traugott (Reference Brinton and Traugott2005: 138–40), the development of discourse markers can be seen as a case of grammaticalization, since it results from several processes that typically co-occur when a form grammaticalizes, such as desemanticization and decategorialization. However, discourse markers tend to acquire more syntagmatic freedom than their original forms. The English evidential expressions I guess, I hear or it seems are a case in point.

I have thus chosen to exclude obligatorification, condensation, coalescence and fixation from my present investigation of English evidentials. However, I have included the process of backgrounding, because this concept has become rather central to the definition of grammaticalization more recently. According to Boye & Harder (Reference Boye and Harder2012), grammatical expressions are ‘ancillary, and as such discursively secondary’, while lexical expressions can be ‘discursively primary’, i.e. the potential focus of an utterance. From this perspective, grammaticalization is synonymous to the ‘ancillarization’ of a form so that it may serve as a background support to a lexical unit. Traugott & Trousdale (Reference Traugott and Trousdale2013: 10–15) acknowledge that this new perspective ‘suggests ways of addressing several problems’ that are left unanswered in the diverse theories of grammaticalization, and Kuteva et al. (Reference Kuteva, Heine, Hong, Long, Narrog and Rhee2019: 5) argue that it is ‘perhaps the most attractive’ proposal to distinguish lexical and grammatical expressions. I found that the process of backgrounding was manifest in many cases of the grammaticalization of evidentiality in several languages, and thus I will take this criterion into account for the present study.

Now that I have clarified my approach to evidentiality and grammaticalization, I will specify the methodology I adopted to collect the data and observe how evidentiality is rendered in English.

3 Data and methodology

The list of evidential forms I will refer to in this study is the result of the research I conducted in Mélac (Reference Mélac2014). In this section, I will describe how I collected a corpus aimed at eliciting evidentials (section 3.1), and what criteria I used to identify what should be counted as an evidential (section 3.2).

3.1 Corpus collection and exploitation

In order to arrive at a list of evidentials that is as accurate as possible, the first step of my study was to collect a contrastive corpus of Tibetan and English using the same methodology of data elicitation for both languages. Tibetan possesses one of the most highly grammaticalized evidential systems, which covers the categories of direct perception, inference and hearsay. Tibetan also presents a written record dating from the eighth century, providing evidence of how evidentiality grammaticalized, which helped me identify patterns potentially applicable to English. I collected the English part of the corpus at Cambridge University (Cambridge Student Corpus, 18 native English speakers, ~26,100 words), and the Tibetan part at Tibet University in the Tibetan Autonomous Region, PRC (Tibet Student Corpus, 8 native speakers of standard Tibetan, ~25,706 words).

The methodology of corpus collection was designed to elicit as many evidentials as possible in a context of conversation between two native speakers. The subjects were requested to ask each other questions related to various information sources, such as ‘Could you tell me how your parents met?’, ‘Tell me about a dream you had’, or ‘Tell me about a story that happened to you when you were three years old’. I also used three activities: recognizing what a set of pictures represent, identifying sounds and reporting the content of a comic strip. This contrastive corpus allowed me to pinpoint what types of evidential forms spontaneously emerge in conversation in Tibetan, and to see how often, as well as in what way, English speakers express their information sources in the same situations. The English part of the corpus contains approximately 2,000 evidential forms, but the expression of information source is, as expected, both rarer and more varied in English than in Tibetan.Footnote 5 After completing my investigation with the help of larger corpora, such as The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), I presented a preliminary description of Present-day English evidential forms that intended to be as exhaustive as possible (Mélac Reference Mélac2014: 149–365).Footnote 6 English speakers mark evidentiality by using words and phrases that belong to many syntactic categories. Here are just a few examples:

I will now present the method I used in order to verify whether a form should be included in the list of evidentials.

3.2 Identification of evidentials

Adopting the strict definition of evidentiality mentioned in section 2.1, I considered a linguistic form to be evidential only when it explicitly denoted which of the three main types of information source the speaker relied on when making his/her statement:

i. Did the speaker witness the situation? (direct perception evidentiality)

ii. Did he/she infer it? (inferential evidentiality)

iii. Did he/she hear about it? (hearsay evidentiality)

The form had to have scope over some propositional content, adding a meta- propositional qualification of evidentiality. A separate sentence such as ‘I saw it’ does reveal the speaker's information source, but cannot be considered an evidential because the information it pertains to is not included in the same sentence.

Tests involving (a) the deletion of markers and (b) the use of these markers in a variety of contexts were applied to verify the evidential nature of the different forms. For example, I hear in I hear John kissed Mary is an evidential because it specifies that the speaker knows about John's action through hearsay. Deleting I hear would result in making a statement without mentioning how one knows about the shared piece of information. Adding I saw it or I inferred it after I hear John kissed Mary sounds incoherent, which confirms that I hear + finite clause is incompatible with a context of direct perception or inference. Conversely, I did not consider an adverb such as clearly to be evidential because it is compatible with all information sources: John clearly kissed Mary… I saw it / I inferred it / I heard about it.

However, the identification and classification of evidentials can be a challenging task for a number of forms. For example, the adjective obvious might appear to express evidentiality in a sentence such as:

(4) It is obvious that Jasper is in love with Alice and would do anything for her. (COCA: Web: Jasper Hale – Twilight Saga Wiki, 2012)

The matrix clause of this example seems to indicate that the speaker shares his/her opinion based on what he/she has observed. However, I would not classify such a construction as a prototypical evidential because obvious is ambiguously polysemic, and often expresses certainty without clearly specifying whether the speaker has witnessed the situation directly, inferred it or heard about it. The evidential meaning of obvious in (4) emerges more from an implicature than an intrinsic semantic feature.

Now that I have specified what I consider to be an English evidential, I am going to examine to what extent they have grammaticalized.

4 Signs of grammaticalization of evidentiality in English

Many English evidentials have undergone changes that are typical of lexical forms progressing towards (semi-)grammaticality. As mentioned in section 2.4, the five criteria I will explore are: reduction, desemanticization, backgrounding, decategorialization and paradigmatization. While space constraints prevent me from exploring the complete set of evidential strategies for each of the five parameters, I will consider and test each parameter with a number of English evidentials taken from a variety of sources. Adopting a wide perspective will allow me to examine how relevant the notion of evidentiality is in English in general, and I thus hope to contribute to the debate on the relation between evidentiality and grammaticalization.

4.1 Morphophonological reduction

Numerous studies have shown a correlation between grammaticalization and reduction (Heine & Reh Reference Heine and Reh1984: 21; Bybee & Pagliuca Reference Bybee, Pagliuca and Fisiak1985; Lehmann Reference Lehmann1995 [1982]: 113, inter alia), and it is possible to observe signs that many English evidentials have undergone reduction. For example, the inferential marker I suppose tends to be pronounced in a reduced form, as is attested by its transcription in several written texts:

(5) See the little swelling buds! See how plain they're showing! S'pose they know they're going to make peaches, apples, cherries. (The Corpus of Historical American English (COHA): M. M. Dodge, When life is young, 1894)

From a phrase made up of three syllables, I suppose often erodes to one syllable in contemporary English. While the deletion of a subject pronoun is a common phenomenon, and does not only concern evidentials, phrases dedicated to the expression of evidentiality seem to be more easily reduced than mere lexical combinations, since s'pose clearly stands for I suppose, and not for they suppose.

The process of reduction can indeed be observed in many other English evidentials, as shown by how they are sometimes transcribed in contemporary novels:

(6) Guess he wasn't hungry after all. (COCA: J. M. Paquette, Lilith, 2003)

(7) Heard she's adopting more children. (COCA: C. Crane, The bad always die twice, 2011)

(8) Mus’ve been a detective from a thriller series. (A. Wendt, Black rainbow, 1992)

It could be argued that reduction is a widespread process which concerns frequent linguistic forms located at various places on the lexicon–grammar continuum. Reduction is a multifactorial phenomenon and frequency is indeed one of the major factors predicting it (Bybee Reference Bybee and Tomasello2003: 38–43). Nevertheless, previous research has shown that grammaticalized forms are often more reduced than equally frequent, lexical forms. For example, when do is an auxiliary, it is usually reduced to /d(ə)/ whereas lexical do is pronounced /du:/. Several examples of evidential markers that have undergone morphophonological reduction corroborate this tendency. The left-periphery markers ØLooks like and ØSounds like are, for example, reduced forms specialized in the expression of evidentiality. They denote that the speaker infers a situation based on some sensory evidence particularly when the subject it is deleted.

(9) Looks like you nailed it. (COCA: Web, Abusing celebrities with cancer in order to promote quackery, 2012)

Conversely, It looks like or It sounds like may express the mere appearance of a situation, not specifying what the situation actually is. In these cases, it is possible to negate the content of the subordinate clause.

(10) It looks like you nailed it, but actually you didn't.

However, when the pronoun it is dropped, the meaning of the same phrase becomes unambiguously inferential, making it less appropriate to contradict the content it introduces:

(11) ?? Looks like you nailed it, but actually you didn't.

The specialization of reduced phrases such as ØLooks like and ØSounds like in the encoding of inferential evidentiality, whereas their non-reduced versions can have a more literal meaning, therefore suggests that they have partially grammaticalized.

4.2 Desemanticization

While it is true that all linguistic forms can undergo semantic change, some forms see their meaning evolve towards a semantic domain that is typically grammatical. They lose concrete meaning in a process usually called ‘desemanticization’, or ‘semantic bleaching’ (Traugott Reference Traugott1989; Heine Reference Heine1993: 89; Ziegeler Reference Ziegeler1997). All semantic domains can be expressed with lexical forms whereas only a few domains (such as time, number, gender, causality, etc.) can be encoded with grammatical means (Slobin Reference Slobin and Slobin1997; Talmy Reference Talmy2000). Indeed, in none of the world's languages have we found grammatical words or inflections meaning ‘bone’, ‘bird’, ‘being in love’ or ‘blue’. The grammaticalization of a form thus typically implies a semantic shift from a specific, concrete meaning to a more generic, schematic meaning. This pattern of semantic change can be observed in the evolution of many English evidentials. Let us consider for example the emergence of sentence-initial Ø Looks like in English.

According to the OED, the verb look comes from Old English lōcian (with several allomorphs). Like its Germanic cognates, lōcian initially meant ‘to direct one's sight’, and its first recorded meaning thus referred to a concrete action. A subsequent meaning of the verb look, when it is associated with adverbs, is ‘to direct one's gaze in a manner expressive of a certain thought or feeling; … to present a specified facial expression’ (OED, s.v. look, v., def. I1b):

(12) Godd..lokeð wraðliche uppe hem ðe euele doð.

‘God looks with anger upon those who do evil.’ (OED: Vices and Virtues, F. Holthausen, ed., 1888, a.1225)

This specific meaning seems to have led to the broader sense of ‘having a certain visual appearance’ (def. II.11b), as the verb started being employed as a copula from the fourteenth century, first with animate subjects, and later with inanimate subjects:

(13) The Clowde began to vanish away, and the heauens looked fayre and cheerefull as before.

‘The cloud began to vanish away, and the sky looked beautiful and cheerful as before.’ (OED: The famous, pleasant, and delightful history of Palladine of England, A. Munday, trans. C. Colet, 1588)

The construction look as if preceded by a personal subject starts appearing at around the same period (def. P2 b), but one has to wait until the mid seventeenth century before seeing the construction look as if with an impersonal subject:

(14) It looks as if men had no designe in the world, but to be suffered to die quietly.

(OED: Vnum necessarium, Jeremy Taylor, 1655)

Although as if has often been replaced by like since the later Middle English period in several contexts, the first instances of the impersonal construction It looks like + clause only emerged in the nineteenth century.

(15) It looks like it belonged to another Continent and to another age of the world.

(COHA: W. T. Thompson, Major Jones's sketches of travel, 1848)

This phrase first meant that the situation has the appearance of something it is not, and later that the speaker presumes what the situation is like. Finally, the construction eroded into the left-periphery marker ØLooks like, and saw its frequency rise from the end of the nineteenth century; it retained the strict evidential meaning ‘from what I can see, I can infer that…’:

(16) Looks like all the Deef Woman wants is to be let alone, while she makes a play the best she can for a home-stake. (COHA: A. H. Lewis, Wolfville, 1897)

The different stages that led the lexical verb lōcian to the evidential ØLooks like are summed up in table 1.

Table 1. Semantic evolution from the action verb look to the evidential øLooks like

This kind of semantic change is typical of grammaticalization, since look has evolved from a concrete action verb to encoding some meta-propositional qualification. The same pattern is observable in the evidential ØSounds like + clause, which ended up encoding an inference based on auditory or verbal evidence after a long process of grammaticalization, which started from the semantic extension of the Old French action verb suner (‘to emit a sound’).

Several other English evidentials have developed from lexical verbs, such as the parentheticals formed on the I guess pattern. The original verbs refer to precise cognitive processes whereas their uses as parentheticals are now specialized in the encoding of inferential evidentiality. For example, one can compare imagine used lexically to the inferential I imagine.

(17) He imagined that he looked like the Buddha himself, under a flowering lotus tree, serene in meditation. (COCA: R. Rougeau, ‘Cello’; The Atlantic Monthly, 2000)

(18) My supervisor, Ceci, appears in the doorway. I imagine we've been making a racket. “Is everything all right in here?” she asks. (COCA: K. D'Agostino, The Sleepy Hollow family almanac, 2012)

Lexical imagine (in (17)) refers to the act of generating a mental picture representing a fictive scene, whereas I imagine (in (18)) encodes that the speaker's statement results from an inference.

Another process of semantic change which typically occurs when a form grammaticalizes is subjectification. Grammatical forms tend to encode meaning from the perspective of the speaker while their lexical sources can be matched with several points of view (see Traugott Reference Traugott1989). Subjectification concerns many English evidentials, further suggesting their movements towards the grammatical pole of the lexicon–grammar continuum. One can for instance compare ØLooks like + clause to its non-reduced form It looks like + clause.

(19) She told me that when you drink something hot, never sip it the first time. Instead, dip your top lip into the cup. That way it looks like you're drinking, but instead you're testing. (COHA: E. Krouse, Other people's mothers, 1999)

(20) I've been watching the standings. Looks like you're heading to the World Championship this year. (COCA: J. Graves, Cowboy take me away, 2013)

It looks like can refer to other people's impressions of a situation, whereas ØLooks like typically expresses an inference made by the speaker.

Several other cases of subjectification are noticeable when examining the semantic evolution of markers that are used nowadays to denote evidentiality. For example, inferential must can be seen as a subjectified extension of deontic must:

(21) It was a law among them that when the lord of the group spoke, the others must obey. (COHA: V. Fisher, Darkness and the Deep, 1943)

(22) His handwriting was steady, precise, so he must have worn his reading glasses. (COCA: P. Painter, ‘Hindsight’; Kenyon Review, 2013)

In (21), must has a deontic meaning, and the obligation it expresses is not imposed by the speaker, but by a law established in a group. Inferential must is considered a further grammaticalization of deontic must, and as illustrated in (22), this specific meaning is construed by adopting the speaker's perspective, since this example could easily be paraphrased by ‘I presume he wore…’, and far less convincingly by ‘John presumes he wore…’.

Grammaticalization is all the more evident when semantic bleaching is tightly associated with a subjective perspective. The distinct evolution of evidential markers consisting of the first-person singular pronoun and a cognition verb is a case in point. Guess or imagine as lexical verbs are, by definition, compatible with all types of subjects. However, when used with the first person, these verbs not only see their syntactic behaviour change, but their semantics also bleaches, since they no longer express a specific mental process but present the proposition they are related to as an inference. In other words, it is specifically when those verbs are used subjectively that their meaning bleaches and comes to encode inferential evidentiality.

4.3 Backgrounding

Boye & Harder (Reference Boye and Harder2009) argue that grammatical forms are prototypically more backgrounded than lexical forms. It seems indeed true that evidential markers are more informatively prominent in English than in languages with an inflectional evidential system, partly because verbs or adverbs are more salient forms than inflections, which normally cannot be the focus of an utterance (Mélac Reference Mélac2014: 394–400). However, a closer examination of the data reveals that many English evidentials are more backgrounded than fully lexical expressions, and do show signs of evolution towards backgroundedness. The ‘non-focalizability’ of grammatical expressions can be revealed by several tests (Boye & Harder Reference Boye and Harder2012), such as the impossibility of receiving a nuclear stress, of being modified by a focus marker, or of being the focus of a cleft sentence. These tests suggest that evidential adverbs, such as presumably, are more grammatical than other adverbs, such as recently. In a prototypical sentence, the nuclear stress is unlikely to fall on presumably while recently can receive it. In examples (23) and (24), the underlined syllable represents the nuclear stress:

(23) He's been seeing her presumably.

(24) He's been seeing her recently.

A grammatical form cannot be in the semantic scope of focus markers, such as just:

(25) *He's been seeing her just presumably.

(26) He's been seeing her just recently.

Finally, a grammatical form cannot be foregrounded in a cleft construction:

(27) *It is only presumably that he's been seeing her.

(28) It is only recently that he's been seeing her.

When an evidential is a matrix clause, one would think logically that its meaning has a higher informational status than the content of its subordinate clause. However, Thompson & Mulac (Reference Thompson and Mulac1991) have shown how clauses such as I think or I guess have lost their matrix clause status, and have been pushed into the background. This mechanism of ‘desubordination’ is observed very frequently when examining the grammaticalization of evidentiality from a typological perspective (Friedman Reference Friedman2018). The secondary status of these matrix clauses can be revealed by a question-tag test. If a speaker chooses to use a question tag after a sentence whose matrix clause has an evidential and/or epistemic meaning, the tag will quite often be formed by extracting the auxiliary and the subject from the subordinate clause, whereas they should be extracted from the matrix clause in a canonical sentence.

(29) I guess he'd be with you then, wouldn't he? (COCA: Spoken Ind_Springer, 1997)

This genuine example sounds perfectly well-formed, but if the matrix clause I guess… is replaced by another matrix clause, such as They decided…, it would not be acceptable to form the question tag with the subject and auxiliary of the subordinate clause:

(30) *They decided he'd be with you then, wouldn't he?

(31) They decided he'd be with you then, didn't they?

Another test suggesting the backgroundedness of a form is its lack of addressability (Boye & Harder Reference Boye and Harder2012). Grammatical expressions typically cannot be questioned by WH- words. Compare (32) and (33):

(32) A: I guess he'd be with you then.

B: How?

(33) A: They decided he'd be with you then.

B: How?

The question How? in (32) is bound to be interpreted as ‘How would he be with me?’, and not as ‘*How do you guess?’. Conversely, the same question in (33) can be interpreted as ‘How did they decide?’.

Evidentials are typically in the background because they no longer participate in the state of affairs described by the speaker, but simply specify how the speaker got to know what he/she is stating. Accordingly, as an evidential expression grammaticalizes, the information it has scope over becomes the main point of the sentence. This does not mean that the speaker always commits to the truth of the proposition, but that the information is at least reliable enough to be shared, and that stating the opposite would sound contradictory. To see more clearly what this entails, one can compare a lexical use of a form with its evidential use. In the first example, it is possible to add ‘even though I know it isn't true’, whereas, in the second example, it would sound contradictory:

(34) I often imagine that I can see her beckoning me to the happy world to which she has gone. (COHA: A. Nehemiah, Catharine, 1859) (even though I know it isn't true)

(35) You have spoken to the landlord, too, I imagine. (COCA: E. Phyllis, The Caravan to Nowhere, 2014) (*even though I know it isn't true)

These tests reveal that many forms expressing evidentiality in English are more backgrounded than their lexical equivalents. It suggests that evidentiality is a notion which, even in English, tends to push into the background linguistic units encoding it, strengthening the hypothesis that these forms have partially grammaticalized.

4.4 Decategorialization

The process of grammaticalization involves the reanalysis of linguistic units according to certain clines (Hopper & Traugott Reference Hopper and Traugott2003: 6–7). These units typically shift from an open- class to a closed-class category, and all the world's languages apparently have this dual system of lexical and grammatical forms. Lexical forms belong to categories that contain hundreds, or thousands of members, and allow new members easily (nouns, verbs, etc.), while grammatical forms belong to categories that possess very few members and rarely accept new ones (determiners, auxiliaries, inflections, etc.). A form starts losing its membership in a major part of speech when it loses the syntactic properties associated with it. For example, when a noun grammaticalizes into a preposition, it loses what syntactically defines it as a noun, such as the singular/plural inflection, the possibility to be determined by an article or modified by an adjective, etc. Many English items expressing evidentiality have been reanalysed into closed classes (modals, copulas, subject-raising verbs) or semi-closed classes (parentheticals, sentence adverbs, discourse markers, complex prepositions). A sample set of examples will be discussed in what follows.

The inferential markers must and should belong to the category of auxiliaries. In Old English, must and should behaved essentially like other lexical verbs, but as they grammaticalized, they lost inflectional properties, such as person indexing, and their usage became restricted to grammatical modifications to a main lexical verb (Roberts Reference Roberts1985). Other verbs employed to express evidentiality may not have reached the full status of auxiliaries, but they have clearly taken a step in that direction. The verbs seem and appear are evidential subject-raising verbs when they license an infinitive, since their syntactic subject is semantically linked to the verb in the infinitive, and these two verbs typically express that the speaker infers the proposition from his/her observations. Both seem + infinitive and appear + infinitive have lost lexical properties, as their syntactic behaviour resembles that of auxiliaries in a number of aspects. They cannot refer to a new state-of-affairs, but can only qualify the proposition expressed by the main verb. They are also largely incompatible with certain inflectional constructions, such as the passive voice. Furthermore, they can be associated with syntactic constructions that are typical of the inferential use of modals, such as the perfect infinitive, or post-modified negation:

(36) You seem to have forgotten that I too have some skill in my poor way. (COHA: W. G. Simms, Charlemont: Or, the Pride of the Village. A Tale of Kentucky, 1856)

(37) The T'kai have no words for time. They also appear not to die. We're sending you to investigate. (COHA: A. Steele, Tom Swift and His Humongous Mechanical Dude, 2001)

The construction seem to have V-en in (36) is comparable to the auxiliary construction must have V-en. The construction appear not in (37) adopts the post-modified negation typical of auxiliaries, and competes with the quasi-synonymous construction doesn't appear. Lastly, seem and appear have partially lost their ability to be modified by adverbs, contrary to other, more lexical verbs, such as mean:

(38) I never mean to hurt anybody. (COCA: Spoken ABC, 1994)

(39) I never seem to hurt anybody.

In both cases, the adverb never is placed before the first verb in the sentence, but in example (38) never has scope over mean, while in (39), it has scope over hurt. Example

(38) can be interpreted as ‘I may hurt people, but never intentionally’ whereas (39) would be more easily glossed by ‘I never hurt anybody, it seems’, which suggests that seem is not actually modified by never.Footnote 7

Several other forms have partially lost their lexical privileges when they mark evidentiality, such as the verb accord, which cannot receive any inflection other than -ing when it encodes hearsay evidentiality in the complex preposition according to:

(40) According to Mom, this was no coincidence. (COCA: A. Gretes, Sweat a wormhole, 2019)

Finally, the loss of inflection typical of decategorialization may also explain why several grammaticalized evidential phrases such as I hear or I guess are used with the zero inflection in cases where they refer to an acquisition of information that must have happened in the past.Footnote 8

4.5 Paradigmatization

Paradigmatization is listed in Lehmann (Reference Lehmann1995 [1982]) as one of the most prominent criteria of grammaticalization. A grammatical paradigm can be identified by a closed set of markers that appear in the same syntagmatic domain, and encode several subcategories of a highly homogeneous semantic frame. English ‘modals’ are a perfect example of a paradigm, as they constitute a closed set of forms, and each one of them encodes a subcategory of a similar semantic frame. They appear in a specific syntagmatic domain since they possess their own slot inside the English verb phrase structure, as shown in table 2.

Table 2. The structure of the English verb phrase

The frame of a paradigm is not airtight because the functions of linguistic forms keep evolving (Nørgård-Sørensen & Heltof Reference Nørgård-Sørensen, Heltoft, Smith, Trousdale and Waltereit2015). As such, so-called ‘modals’ are not only used to express modality, but also other notions such as time, aspect and evidentiality.

Paradigmatization is often seen as resulting from decategorialization. The latter involves the eviction of a linguistic form from an open-class category, and the former refers to the complete adherence of this form to a closed set. However, certain forms may be more advanced on one parameter than the other, which justifies treating the two processes separately. The paradigm of perception copulas is a good example of forms that do not display many signs of syntactic erosion but constitute a homogeneous paradigm. Despite their varied origins, the copulas look, sound, feel, taste and smell have each taken a different path that led them to the same evidential paradigm. The etymology of look, feel and smell is Anglo-Saxon, whereas the verbs sound and taste come from Old French (OED). Their diverse routes to the same destination typically illustrate the process of paradigmatization, which involves ‘a levelling out of the differences with which the members were equipped originally’ (Lehmann Reference Lehmann1995 [1982]: 135). These copulas now belong to a closed set sharing a specific syntagmatic domain, since a very limited number of verbs in English can be complemented by an adjectival phrase as a subject complement, a prepositional phrase in like, or a clause introduced by as if or like.Footnote 9 Their semantic frame is clearly evidential, as they encode either a direct perception or an inference, further specifying which sensory channel led to this impression. The syntactic and semantic organization of the perception copula paradigm is summed up in table 3.

Table 3. The perception copula paradigm and its evidential functions (simplified)

There are other examples of English evidentials that function in a paradigm, such as the cognition verb constructions I guess/I suppose/I imagine/I assume, etc. These phrases are based on the same model, and organized in a closed set. They share the syntactic properties of parentheticals, allowing them to be inserted in various positions in a sentence, and they all express epistemic modality and inferential evidentiality with subtle semantic and discursive nuances.

The special behaviour of all these markers shows that evidentiality is not a semantic domain like any other, since evidentiality tends to impact the internal and external syntax of the lexical forms encoding it. Evidentiality seems to make linguistic forms behave more and more like grammatical items, leading them to closed-class categories. It can nevertheless be argued that the grammaticalization of evidentiality is still partial in English, since these forms have not reached the final stage of the process, which would be to bind to a host word, and enable them to work as an inflection. However, is it really true that English does not possess any inflection which can encode evidentiality?

4.6 Evidential inflections in English?

It is generally accepted that the verbal inflections of English denote the grammatical categories of person (third-person -s), tense (present -ø/-s vs past -ed) and aspect (gnomic or habitual -ø vs progressive -ing vs perfect -en). It is also accepted that the ‘past inflection’ -ed can also encode ‘modal remoteness’ in some contexts, as in If he worked… or I wish he worked… However, for the -ed inflection to mark modal remoteness, the sentence has to include a specific trigger, such as the de-actualizing conjunction if or the boulomaic verb wish. Might there exist special contexts where evidentiality determines the choice of an inflection in English?

Let us consider the following examples:

(41) I heard that he takes showers, you know – when he's having a bad game he'll take a shower at half time, you know. (COCA : Spoken NPR_ATC, 2007)

(42) I heard him take showers.

The propositions introduced by I heard will be interpreted differently depending on the form of the clause, which is determined by the inflection of its verb. The latter can be either finite (with the present or past inflection, as in (41)) or non-finite (with the gerund or bare infinitive inflection, as in (42)). What motivates the choice between the two options is the evidential specification given to the proposition. When the verb in the subordinate clause is finite, the speaker knows about the situation from hearsay, whereas a clause with a non-finite verb encodes an auditory perception.

Other examples reveal the exploitation of the English inflectional system to encode evidentiality. The past participle inflection is used in English for the passive voice construction (be + V-en), and transitive verbs can normally appear in the active or passive voice. However, as Huddleston & Pullum et al. (Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: 1435) point out, three verbal constructions happen to be limited to the passive voice: be said to, be rumoured to and be reputed to. What is particularly striking is that these three constructions are specialized in the expression of hearsay evidentiality. The verb say can undeniably be used in the active voice, but it will only be followed by an infinitive clause with a jussive function, and not a declarative function. One can therefore compare:

(43) Mom says to be there at two o'clock. (COCA: C. Johnson, That mistletoe moment, 2007)

(44) Queen Elizabeth is said to be devoted to her children. (COCA: K. Emerson, Secrets of the Tudor Court: The pleasure palace, 2009)

In example (43), say is in the active voice, and the infinitive clause can only be interpreted with a jussive meaning. In example (44), the use of be + V-en transforms the meaning of the whole construction, which then encodes hearsay (see also Noël Reference Noël2001).

Finally, one can notice that most modal auxiliaries of modern English have retained a dual system of inflections: can/could, may/might, shall/should and will/would. The system is now very asymmetric. The first inflection of the modal shall is, for example, limited to the expression of deontic modality, whereas its second inflection should can either have a deontic or an inferential meaning:

(45) This is a niche he should know well: Jacobs was Canada's downhill champion in 1957. (COCA : Magazine Skiing, 1993)

In this example, should expresses an inference, since ‘he should know’ could be paraphrased by ‘I suppose he knows’. Replacing should with shall would not change the time reference of the state-of-affairs or the strength of the modal qualification, but would simply be infelicitous. One can thus conclude that the so-called ‘past inflection’ of shall has developed some specific extensions, one of which being the encoding of inferential evidentiality for a present or future state of affairs. It is yet another case where an inflection is used to encode evidentiality.

Evidentiality can therefore be expressed by forms that belong to closed-class categories in English, and even by verbal inflections in specific contexts. Those inflections do not result from lexical items that have gradually grammaticalized into evidential markers. Instead, they are forms that had already grammaticalized for a particular function, and have been recycled into evidentials. It might be possible to argue that these examples of semantic shifts are not actual cases of grammaticalization, because the forms in question were already grammatical. However, several studies have shown that the evidential inflections of so-called ‘evidential languages’ also result from the semantic shifts of forms that had previously grammaticalized for another function. For example, inferential evidential inflections come from perfect aspect inflections in many languages (Willett Reference Willett1988; Mélac Reference Mélac2014: 433–4; Johanson Reference Johanson2018). In Tibetan, direct perception evidentials come from locative or directional inflections (Tournadre Reference Tournadre and Guentchéva1996; Oisel Reference Oisel2013: 75–9; Mélac Reference Mélac2014: 432–3). Other evidentials seem to result from the semantic evolution of past tense inflections, as in Matses, a Panoan language (Fleck Reference Fleck2007: 614).Footnote 10 The grammaticalization of these forms occurred before they came to encode evidentiality, but it does not change the fact that they have indeed grammaticalized and are now used to express evidentiality. The contexts of use of English evidentials may be more limited than in some other, non-Indo-European languages, but it can no longer be maintained that English grammar does not encode evidentiality.

5 Discussion

The previous analysis has offered a non-exhaustive account revealing that evidentiality is partly grammatical in English. I have chosen several forms that can encode the semantic domain of evidentiality, and assessed whether they have undergone processes of change that are typical of grammaticalization. As in so-called ‘evidential languages’, English grammatical evidentials come either from lexical forms expressing information sources that have undergone grammaticalization, or from forms that were already grammatical, and which have extended their uses to the evidential domain. The data on English evidentials show that the grammaticalization of evidentiality is substantial, and seriously question the widespread belief that evidentiality has only grammaticalized in a few non-Indo-European languages. Evidentiality is instead a necessary concept for a thorough description of English grammar.

It might be argued that linguistic change is an omnipresent phenomenon, and that similar processes could be observed, regardless of the semantic domain investigated. While it is true that all linguistic forms can undergo changes, certain linguistic changes, such as decategorialization and paradigmatization, are symptomatic only of grammaticalization, and concern a very limited number of forms. Furthermore, it is the accumulation of changes typical of grammaticalization that allows me to state that evidentiality is a semantic notion with a special force of attraction towards the grammatical end of the lexicon–grammar continuum. In other frequent semantic domains such as anatomy, health, behaviour, food, colour, politics, sports or the arts, words do evolve, but it is not the case that the linguistic units expressing these domains behave more and more like grammatical forms.

It might also be argued that the linguistic forms that I have described belong to syntactic categories that are so disparate that one cannot talk about evidentiality as a single consistent grammatical category. In reality, the expression of evidentiality is not as consistent as one could imagine in so-called ‘evidential languages’, since inflectional paradigms are multifunctional, and all such languages do have lexical and semi-grammatical ways to render the notion in addition to the grammatical means (see Mélac Reference Mélac2014: 371–411). It is generally accepted that time and modality are grammatical notions in English, while they are frequently expressed by inflections, auxiliaries, semi-auxiliaries and adverbs, among other means. What makes evidentiality a consistent notion is that it refers to a coherent semantic domain. Like any semantic domain that triggers grammaticalization, it influences various lexical forms moving towards grammatical categories at different paces.

The grammaticalization of certain forms may be more advanced on certain criteria and less on others. For example, I guess has undergone reduction because it is almost never followed by the complementizer that and its pronominal subject is frequently omitted. It has desemanticized, since it no longer refers to a specific mental process but to a broad inferential qualification. It is backgrounded, as revealed by the tag question test. It has also decategorialized in the sense that selecting the evidential meaning greatly limits the possibilities of inflections and modifications for the verb guess. One may say that it has also paradigmatized, as it appears in a syntactic slot where the speaker can choose from several alternatives such as I suppose or I assume. However, it seems that the paradigm is not as closed and clear-cut as other paradigms such as the modal auxiliary paradigm, or the copular verb paradigm in English.

The auxiliary must has desemanticized when it encodes an inferential meaning. It has clearly decategorialized and paradigmatized since it no longer has the properties of lexical verbs, and can only be used in a specific slot within the verb phrase structure. However, some scholars have pointed out that it is rarely reduced when used as an inferential marker, and the tests of backgroundedness are only partially conclusive.

Sentence-initial øLooks like combines desemanticization and backgroundedness particularly in its reduced form. One can say that it has decategorialized because using this phrase with an evidential meaning limits its possibilities in terms of inflections and modifications. Finally, even though it does not seem to have clearly entered a closed class of parts of speech, it appears in the category of left-periphery particles where it can alternate with øSounds like, each expressing a different subcategory (visual inference vs auditory inference) of the same evidential frame.

Even though certain English evidentials meet more criteria of grammaticality than others, all evidence confirms that evidentiality does have grammaticalizing tendencies in English. Table 4 illustrates this point by presenting six common English evidentials, and evaluating them according to the five criteria of grammaticalization investigated in this study. A minus sign (–) is used when the given evidential does not show clear evidence of validation of the given criterion. A plus sign (+) appears when the given evidential meets the given criterion, suggesting that it may have grammaticalized. A double plus sign (++) indicates that the given evidential shows significant advancement towards the grammatical pole of the lexicon–grammar continuum according to the given criterion.

Table 4. Parameters of grammaticalization (six common English evidentials)

6 Conclusion

There may be differences between so-called ‘evidential languages’ such as Quechua or Tibetan, and other languages like English, but the data presented here argued against a dichotomous view of evidentiality, which would underestimate its relevance for the majority of languages. This investigation did not challenge the fact that languages differ in the degree of grammaticalization of some of their evidentials, but aimed to disprove that the English evidential system is purely lexical.

Further research is required to fully account for the phenomenon, but it is unlikely that the linguistic changes that led to the forms encoding evidentiality in English have happened by sheer accident. As we know, not all semantic domains trigger such patterns of evolution. The evolution of forms expressing evidentiality towards the grammatical pole of the lexicon–grammar continuum confirms that this notion is pertinent and necessary for a thorough linguistic description of English grammar. It also suggests that this semantic domain has to be investigated as a potential grammaticalizing notion in all language families. Evidentiality does not seem to be so much a grammatical category present in only a few ‘exotic languages’, but rather a universal functional niche that has an observable impact on the lexicon–grammar interface of any language.