Defining Steppe Zoomorphism

A pre-cursor to the Silk Roads, the Eurasian Steppe network stretches from the Mongolian-Manchurian grassland to the Hungarian plain. During the Iron Age (eighth to second century b.c.e.) in Central Eurasia,Footnote 1 the region was occupied by pastoralists known under loose umbrella exonyms such as Scythians, Saka, Donghu 東湖, Xiongnu 匈奴 and Sarmatians. These politonyms are indebted to the historiographical accounts of Chinese and Classical thinkers—Sima Qian, Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, Strabo, Ctesias, and others. As such, external ethnographies of pastoral societies often fall into the trap of essentialism and political bias, constructing a one-fit-all model for what were in fact diverse and complex societies who left behind no evidence of a writing system.Footnote 2 Equally misleading at times are blanket geographical or cultural attributions such as “northern zone” or even the “northern periphery” of China, both of which seem to mean different things to different disciplines and schools of thought (for one, the so-called Chinese northern periphery likely considered itself a center to a purely nomadic periphery further north rather than a periphery to a Chinese capital). The archaeological cultures along the steppe cultural domain point to shared characteristics in material culture but also indicate regional and local departures from the broader visual formula. Steppe zoomorphic visuality is traceable to the following archaeological cultures: Ordos Loop, Tuva basin, Altai mountains, Kazakh steppe, Ural lowlands, northern Black Sea grasslands, Dobrudzha and the Hungarian plain. More broadly, the Eurasian steppe is traditionally divided into Western (Pontic-Caspian), Central (Kazakh) and Eastern Steppe (Mongolia, north China, South Siberia). In the Warring States, the pastoralists of the Eastern Steppe started to respond to earlier developments in material culture in the Central and Western Steppe, where zoomorphic visuality had become the dominant principle in image-making as early as 800 b.c.e.

Portable gold adornments cover the bodies of nomadic nobles from the highest echelons of those pastoral societies.Footnote 3 Hereafter, I refer to such individuals as “super-elites” or the “elite nucleus,” thus distinguishing them from the middle-ranking warriors whose proximity to the ruling elite was accomplished through military merit but never resulted in actual membership in that nucleus. Moreover, the mid-ranking warriors rarely wore large amounts of gold, instead opting for bronze, felt, leather or wood. Drawing from Wenskus's framework applied to the social formation of the Germanic tribes in the early Migration Period, I also consider the ability of that small yet unstable and negotiable elite “core” to manufacture and maintain the collective memory and ties of the otherwise reluctant nomadic alliances along the Chinese northern border and further west.Footnote 4 Belt buckles, plaques, torques, and elongated headdresses forming elaborate funerary suits define the portable luxuries produced and circulated among the elite of the steppe starting in the eighth century b.c.e. Sometimes, as many as four-thousand gold ornaments adorned the interred noble's body—such was the case with at least five nomadic noblemen and one noblewoman buried on the Kazakh Steppe, now known as the “Golden Men” of Kazakhstan.Footnote 5 Images of peculiar zoomorphic configurations embellish the surfaces of such portable metalworks. The light-reflecting properties of massive gold amounts would have been even more impressive. Across these archaeological findings emerges a shared approach to conceptual design in zoomorphic adornment. This design strategy becomes the common denominator at the heart of a trans-steppe visual formula, always rooted in a very particular conception of animality. I identify three primary visual tropes in the animal-style formula shared and translated widely across this expanse: (a) zoomorphic entanglement (b) visual synecdoche present in zoomorphic junctures, and (c) visual parallelism (bilateral reflectivity). Not all three tropes “catch on” in the northern Chinese periphery for reasons which I henceforth set out to uncover. Considering the ancient Chinese artisan's preoccupation with zoomorphism in ritual bronzes, one wonders whether, and to what extent, the steppe zoomorphic rhetoric was integrated into early Chinese art and design. One might also ask how animality is conveyed similarly or differently in these neighboring cultural spheres, and how distinct visions of zoomorphism in China and the steppe converged under specific socio-economic conditions. Why did some zoomorphic designs travel swiftly across thousands of miles while others barely left their birthplace? And what was China's role in such transmissions?

The Zoomorphic Entanglement Trope: Beyond the “Animal Combat” Narrative

First, one needs to better understand the term “animal style” which is often applied too broadly and arbitrarily across cultures and media. In the context of Central Eurasia, it is a kind of zoomorphic visuality that is rooted in the ecology of steppe biota, the core principles of pastoral nomadism, and the psychology of mobility. As such, it also constitutes a type of visual rhetoric shared by the elites across different steppe communities, all of whom likely did not invent their own writing system. Nonetheless, the animal-style visual language had its distinct regional and local topolects in the Western, Central and Eastern Steppe: a shared trope was often interpreted differently at these micro levels. The first such device, which I describe as “zoomorphic entanglement” rather than “animal combat,” appears in scenes of entwined animals. Although we frequently encounter predation imagery across the steppe micro-zones, some images are not always meant to depict inter-species combat. Realistic scenes of animal fights are more typical of the Western Steppe than they are of the regions along China's periphery. Realistically conveyed animal predation appears on funerary goldworks from Scythian tombs in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe where animal contours are less condensed, and animals have preserved their relative taxonomical credibility. The more naturalistic representation of animal combat in the Western Steppe might be indebted to the Pontic Scythians’ close interactions with Classical Greece and Achaemenid Persia both of which showed a certain proclivity for confronted animals and lifelike renderings of forms (Figure 1). As Gombrich would have probably exclaimed, the “sense of order” sought by artisans in Western Antiquity was closely allied with that in the creations of their Scythian neighbors.Footnote 6 Such depictions abound in the animal-style collection of Peter the Great, comprising approximately 240 gold ornaments, weapons, and vessels from plundered Siberian tombs, the majority of which are identified as Pontic Scythian and Sarmatian.Footnote 7 Figure 1, a classical “animal-style” example, shows a predator caught in the midst of a vigorous fight, ferociously biting onto the excessively contorted back of the horse.Footnote 8 The textured teeth and claws, along with the crisp delineation of contours, expose the predatory nature and violent intensity of the conflict. Similar findings come from numerous royal Scythian tombs at Kul'oba, Chertomlyk, Solokha, MelgunovFootnote 9 in Crimea and other elite nomadic barrows in the north Caucasus.

Figure 1. Animal combat scene. Belt buckle. Gold, hammered and soldered, inlay. Fourth to third century b.c.e., Siberian collection of Peter the Great (likely from South Siberia).

Source: The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

The Solokha barrow on the left bank of the Dnieper is a pivotal case in point as it has yielded objects exhibiting animal-style tropes specific to the north Black Sea grasslands.Footnote 10 A golden comb from the inventory features human images in defiance of the well-known nomadic penchant for zoomorphism.Footnote 11 Around the legs of the interred Scythian noble were found 130 golden plaques, also featuring human images of (likely) local Scythians from the area of the Black Sea coastal cities at the Greek periphery (e.g., Olbia).Footnote 12 Similarly, a bowl from the same tomb with a depiction of a lion hunt also features humans—a subject matter not normally favored by nomadic patrons. This proclivity for human subjects engaged in hunts is also echoed on the decoration of golden philae and an overlay for gorytos from the same tomb. These items are assumed to be reflective of the Greco-Scythian context, featuring Scythian subject matter along with workmanship techniques and object types popularized by the Greeks. In his ethnography of the Scythians in Histories, Herodotus speaks of many colonial Black sea ports like Olbia and Chersonesos as cultural cauldrons, with Scythians and Greeks actively engaging in commercial interactions.Footnote 13 A fusion of steppe and Classical elements could explain the surprising departure from the zoomorphism seen elsewhere along the steppe expanse and in early China: the Classical Greek interest in human anatomy coupled with the centrality of the human experience in the Greek canon was not left unnoticed by the Scythian alliances working to accommodate the new markets in Greece and Thrace. By comparison, Chinese art had been primarily zoomorphic and devoid of human imagery from its very inception.Footnote 14

Be that as it may, even in select regions of the North Black Sea Steppe, zoomorphic entanglement of form becomes the de-facto visual trope employed in animal-style décor. In some instances, however, predation is conveyed metonymically and schematically, marking a departure from the Classical idiom of anatomical realism. A different example from the collection of Peter the Great shows an aggressive feline predator mauling an elk—here, it becomes difficult to untangle the contours and decipher the species’ identitiesFootnote 15 (Figure 2). The elk's snout has the characteristics of a raptor's beak, and its antlers are extremely stylized. It is increasingly challenging to decode such metonymies which only allude to animality without conveying the entire anatomy. Here, a condensed microcosm of zoomorphic fabrications adorns the surface. This image marks a structural and conceptual departure from more realistically rendered objects from the Western Steppe: while zoomorphic imagery is at the heart of the design formula in both, each adopts a different approach to zoomorphism. In the last instance, it might be more appropriate to speak of the imagery in terms of “zoomorphic entanglement” rather than combat: contours and shapes are so entangled that they lose their structural crispness and biological clarity. Crowded, condensed, and stylized, the antlers here echo an earlier development seen on the surface of the so-called “deer stone” monoliths across South Siberia and Mongolia.Footnote 16 Dated to the Bronze Age and thus preceding Iron-Age steppe ornaments, deer stone structures present a comparable vision of zoomorphism in which animal forms and classifications are fluid and negotiated rather than strictly outlined. Drawn or pecked vertically along such stone slabs, deer antlers tend to replace complete deer bodies thus fulfilling similar metonymic functions.

Figure 2. Gold bridle fitting with animal contest scene of a feline predator mauling an elk. Gold, cast and hammered. Siberian collection of Peter the Great.

Source: Simpson and Pankova, Scythians, 67, Fig. 26.

One also wonders how regional and local interpretations of this trope are applied as one moves closer to the northern Chinese periphery. The answer lies a few centuries earlier and several thousand miles east of the Black Sea. More examples consistent with this zoomorphic entanglement occur in the funerary complex of Arzhan-1 and 2, situated in the Tuva basin of South Siberia. The finds from the kurgans at Arzhan-1 include horse gear, bridle ornaments, weapons, and other fragments such as beads and semi-precious stones.Footnote 17 A much earlier example (and a possible archetype) of the trope in question comes from the Arzhan-2 barrow dated to the eighth century b.c.e.Footnote 18 There, the main tomb constitutes a rectangular pit with wooden chambers. It has yielded thousands of gold items, mostly decorative appliques consistent with the Pontic Scythian style which they predate by at least a century.Footnote 19 The image embellishing a golden sword clip from Arzhan-2 presents another metonymically conveyed zoomorphic entanglement (Figure 3). Animal heads denote the presence of the whole organism in a schematic, pro-forma mode of expression: a feline head devours a deer one. Both are excessively abbreviated: their forms are overtly intertwined, and their outlines quickly lose the crispness and autonomy that were once so tangible on Pontic-Caspian examples influenced by Greek conventions. Animal bodies are thus reduced to their signature components, creating a visual cacophony of intertwined, fluid forms. Since this is the earliest known nomadic tomb on the Eurasian Steppe, it is likely that later variants of this trope were derived from the Arzhan approach to zoomorphism.

Figure 3. Clip of sword knot, Arzhan 2, Tuva. Late eighth century b.c.e.

Source: Image is used from www.hermitagemusum.org, courtesy of The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Along the northern Chinese periphery, animal style follows the Arzhan regional formula more closely than it does the Pontic-Caspian one. Animal combat takes on a new form in Warring-States north China where entwined zoomorphic bodies no longer look like well-delineated, lifelike species entering combat. Nowhere is this more evident than at the cemetery of Majiayuan 馬家塬 in Gansu 甘肅, dated to the late Warring states or early Qin.Footnote 20 The burials might have belonged to nomads collectively referred to as Xi Rong 西戎 (Western Rong) in Chinese chronicles. The Shi ji mentions interactions between the Qin state, which originated from the Tianshui 天水 vicinity of the cemetery, and the Rong. It goes as far as claiming that once the Qin customs merged with those of the Rong and Di barbarians, cruelty and violence took over, and benevolence and righteousness were diminished (今秦雜戎翟之俗,先暴戻,後仁).Footnote 21 Most of the tombs at Majiayuan follow the traditional catacomb structure, some also featuring auxiliary chariot pits which point to a local hierarchy.Footnote 22 The burials have yielded several wooden chariots, consistent with earlier Western Zhou ones, which are covered with animal-style gold and silver decorations made of abstracted antlers. Smaller steppe items were found on or near the interred nobles.Footnote 23 The interred bodies in the largest burials were those of nomadic nobles. Elite tomb occupants were covered with gold adornments consistent with the portable luxury and zoomorphic visuality of other steppe alliances. The gold object shown in Figure 4 exbibits an incredibly intertwined hodgepodge of twisted, distorted, or abbreviated animal forms: swept in the visual cacophony, one might be able to decipher several raptor beaks and snake bodies, but ideation remains obstructed. Other plaques from the cemetery, also made of gold and inlaid with semi-precious stones, follow the same mode of stylization and extreme abstraction. Along the northern Chinese periphery, inhabited by mixtures of nomadic and sedentary populations, the original “predation” theme undergoes a conceptual and structural shift: animal shapes enter a full pars-pro-toto mode. Across the northern zone in China, the visual trope of animal combat could be more accurately described as a zoomorphic entanglement in which animal anatomies lose their visual and functional autonomy, instead forming a zoomorphic juncture of individual taxonomical references. Eastern Steppe nomads seem to have developed a regional topolect of the broader trans-steppe visual trope by prioritizing abstraction and the removal of animal bodies from the reality of their biota. The Majiayuan example rejects the Pontic embrace of naturalism and anthropomorphism, most likely because neither human nor naturalistically rendered animal bodies could fit organically with the already established aesthetic of the Central Plains.

Figure 4. Plaque. Gold with inlay. Fourth to third century b.c.e., Majiayuan, Gansu province.

Source: Xirong yi zhen: Majiayuan Zhanguo mudi chutu wenwu, 42

Moreover, the plaques at Majiayuan reveal a less elaborate inlay technique when compared with similar animal-style articles from other steppe micro zones, particularly the superbly executed Sarmatian examples from Khokhlch in South Russia, a first-century tomb widely known for its inlaid animal-style embellishments.Footnote 24 This might be because the craftsmen at Majiayuan were less seasoned in goldwork; indeed, they were either local Rong artisans or possibly artisans from the Qin state, which wished to export these adornments for the northern market. The later scenario is especially plausible considering the inconsistency in design, rushed distribution and uneven application of inlay. The craftsman might have been tasked with the making of a great number of plaques which he had to cast separately. He might have, as a result, compromised the overall quality of the goldwork. Such rough execution would be unthinkable at the heart of the steppe realm where bodies of the highest-ranking nomadic elites, such as the famous “Golden Man” of Issyk (Kazakhstan), were covered in as many as four-thousand gold objects all rendered to perfection. But while artisans on the steppe produced these items as custom jewelry for the top elites, their Chinese rivals had a more pragmatic goal in mind. It is important that almost all the animal-style objects at Majiayuan and the northern Chinese periphery in general used casting to make such objects—indeed, this was most opportune because artisans in early China were accustomed to bronze casting, and switching to gold would not have presented significant difficulties. However, the difference in quality should not be attributed simply to the Chinese lack of experience with steppe-style goldwork. In the Eurasian Steppe proper, plaques akin to the Majiayuan ones were often produced specifically for the burial of a noble from the highest echelons of nomadic society. Even when they were used by the deceased in his life, it was probably not in his everyday wear but on special occasions of significance to the nomadic alliance (e.g., a military victory). We rarely see these gold plaques and buckles on the bodies of mid-ranking nomadic warriors. Yet in early China, the production of such animal-style goldworks was likely mainly meant for export to the northern nomadic market, and it was only later (and seldom) that some of these items produced for purely economic benefit were taken out of circulation to honor a Han Chinese deceased noble.

Some hints to the increasingly opportunistic interactions between China and its northern neighbors can be found in the scattered textual references to the region in the Shi ji. We know from the Biographies of the Money Makers (“Huozhi liezhuan” 貨殖列傳) chapter that the first emperor of Qin honored the stockbreeder Wuzhi Luo who facilitated trade with the Rong people.Footnote 25 He raised domestic animals, and when he had large numbers of cattle, he sold some and bought rare silks and sold them to the king of the Rong; the king of the Rong repaid him ten times the original cost of the articles by sending him great numbers of domesticated animals.Footnote 26 The Tianshui region is identified as prolific for trade further into the chapter and as laying in close proximity to the Qiang nomads (to their west) and the Rong and Di (further to the north).Footnote 27 The “Money Makers” section overall indicates that with the establishment of the Han dynasty, many barriers to trade were removed and restrictions on the use of mountain and water resources were significantly relaxed; in light of this increased circulation of goods, it makes sense that we see a cemetery with syncretic features and inventories with steppe-inspired designs in the region controlled by the Qin. Naturally, these are scattered and brief textual fragments but in light of findings like Majiayuan, and the equally sumptuous burial M30 at Xinzhuangtou 辛莊頭Footnote 28 in the Yan capital of the late Warring States, one cannot help but embrace the possibility of an increasingly opportunistic exchange between China and the steppe nomads. Thus, what has been frequently described in rather florid terms as “cultural exchange” was in fact an exchange driven by economic objectives. We shall return to this point in the following sections.

The Visual Synecdoche Trope

The trans-steppe visual formula relies heavily on a “pars-pro-toto” device, rooted in replacement and reduction of bodies, anatomies, concepts. Abbreviation and transposition guide the underlying logic in the construction of steppe visuality across most archeological cultures. Antlers denote the presence of a deer, a curved beak implies a raptor, horns stand for a ram, a mane suggests a feline, and hoofs indicate a horse: each fulfills the function of a visual synecdoche denoting a fully fledged animal through the introduction of its signature anatomy. Such allusions are then fused together into an irregular anatomical composite—a zoomorphic juncture. The resulting anatomical hodge-podge is a counterfactual zoomorphic body composed of the incongruous anatomical parts of various animals—once fused together, the individual anatomical allusions lose their visual, conceptual, and taxonomical autonomy, engendering a new organism. Notable examples of syncretic antlers terminating into bird heads come from the tombs of the equestrian Pazyryk culture (fifth to third century b.c.e.) nested in the alpine ravines of the Altai, as well as a bronze bell terminal from Ul'skii aul in the Northern Caucasus (sixth to fifth century b.c.e.; Figures 5 and 6). Neither of the two items from the Scythian phase are made of gold. Still, the same zoomorphic principle recurs in both instances. In the Pazyryk case, predation is framed by a visual synecdoche: antlers denote stags which in turn emanate into bird heads attributing a raptor-like quality to the organism. One of the main predators has an outline of a griffin-like creature but the overall configuration is one of great ambiguity, guided by transposition, substitution, abbreviation. The same is true of the cast bronze terminal: a curved raptor beak indicates the raptor's animality while the stylized meanders on the being's head allude to deer terminals. Looking closely at the bronze bell terminal, one might also notice two raptor silhouettes—a more pronounced one at the center of the imagery and a concealed one facing leftward. Such bizarre concoctions become prominent image-making tools across the steppe domain and reach the Chinese northern periphery around the early Warring States. I have discussed their possible functions as potent guardians and expressions of the nomadic maker's anxiety over the unpredictability of their changing biota in a different article, drawing from Ernst Gombrich's preliminary observations of zoomorphic junctures in other ancient cultures; this theme is slightly beyond the goals of the present discussion but should be taken into account.Footnote 29 All nomadic burials across Central Eurasia exhibit a desire to circumscribe beasts into more manageable formats, and also reduce their anatomy in the hope of controlling their prowess—in Pazyryk, for instance, even sacrificial horses are covered with such animal-style objects or horned masks to obfuscate their anatomy and potentially dangerous power. These aims might also account for the nomadic rejection of “monumentality” and persistent adherence to portable luxury, which the canon has simply, and in my view unjustly, shrugged off as a lack of resources and ability. The reliance on the visual synecdoche and abbreviated anatomies detached from modern-day Western taxonomies was purposeful and only made sense if the surface of objects was limited and the animal forms crowded and fluid. It is unknown whether Chinese artisans understood those nomadic conceptions, but they certainly studied and copied the peculiarities of the designs behind them.

Figure 5. Griffin holding a stag in its beak. Finial, fifth century b.c.e.

Source: Image is used from www.hermitagemusum.org, courtesy of The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Figure 6. Bronze bell terminal. Ulskii'aul no. 2 barrow. Late sixth-early fifth century. Kuban, Russia

Zoomorphic junctures frequent nomadic funerary sites in the Ordos Loop 鄂爾多斯, a cultural zone in Warring-States north China (lower Yellow river bend) inhabited by various pastoral nomadic peoples.Footnote 30 In the “Xiongnu liezhuan” 匈奴列傳 some of the Ordos Zone inhabitants are referred to as Linhu 林胡 (“forest barbarians”) although the exonym, like many other in the Shi ji, probably constitutes an umbrella reference to ethnically and culturally diverse steppe groups. The chronicle only mentions the Linhu twice in a general discussion regarding the umbrella group of the Donghu 東胡 during the reign of Duke Wen of Jin and Duke Mu of Qin in the seventh century b.c.e.Footnote 31 After the defeat of the Linhu and the closely related group Loufan, King Wuling (r. 325–299 b.c.e.) ordered the construction of a great wall starting from Tai at the foot of the Yin Mountain range.Footnote 32 Not much is known about the Linhu through these textual references. Archaeological finds, however, provide more insights into their material culture.

At the Inner Mongolian cemetery of Aluchaideng 阿鲁柴登 associated with the Linhu nomads, archeologists uncovered numerous gold and silver ornaments, including the widely published two-part headdress topped by a turquoise bird and a large number of small plaques and buckles.Footnote 33 A few of the gold buckles are embellished with images of individual animals such as porcupines and dragons.Footnote 34 (See Figure 7a) However, most plaques and buckles embellishing the deceased's attire feature zoomorphic junctures comprised of a feline body with a ferocious jaw and sharp claws, deer antlers sprouting into bird heads with curved beaks. The outcome is an apparent aberration from taxonomical normativity. This approach to zoomorphism presents a biological fallacy although the final image appears surprisingly organic when subject to the initial scrutiny of an unsuspecting viewer. Here, the syncretic antler trope stands out—the “deer-ness” denoted by the antlers is disrupted and consequently fused with the “bird-ness” of the raptor's head. The designer constructed steppe-inspired visual parameters of animality (Figure 7b). Conceptually there is no difference between the Aluchaideng syncretic antler trope motif and the ones from Pazyryk and the Caucasus.

Figure 7a. Aluchaideng ornaments. Fifth to third century b.c.e.

Source: Chengjisihan: Zhongguo gudai beifang caoyuan youmu wenhua (Beijing: Beijing chubanjituan, 2004), 88.

Figure 7b. Gold buckle from Aluchaideng. Fifth to third century b.c.e. Inner Mongolia.

Source: Zhao Fangzhi 趙芳志, Caoyuan wenhua: youmu minzu de guangkuo wutai 草原文化: 遊牧民族的廣闊舞台 (Shanghai: Shanghai yuandong, 1999), 111 bottom.

In the Warring States, we continue to observe the wide implementation of this abstruse visual trope across nomadic tombs, including at the Ordos site of Nalin'gaotu 納林高兔 in Shenmu 神木 county, Shaanxi. A headdress finial (Figure 8) features a fantastic composite with syncretic, irregular features. The whimsical creature is a prime example of the zoomorphic juncture (synecdoche) trope in north China. The hoofed animal has a griffin head in place of its tail, a dramatically curved raptor's beak, and exaggerated, stylized deer antlers which evolve and sprout into four additional griffin heads. Its anatomy is both functionally and visually disturbed, fragmented and reordered. Such syncretic antlers are found across Ordos sites of the Warring States, such as in the burial at Xigoupan 西溝畔 and the Nianfangqu 碾坊渠 hoard in Inner Mongolia.Footnote 35 Such creatures are transitional and inherently unstable, fluctuating between various ontological and biological categories.

Figure 8. Gold ornament. Nalin'gaotu, Shenmu county. Fifth to third century b.c.e.

Of particular pertinence to the Ordos corpus of material is an example from a Qin bronze caster's tomb located at Beikangcun 北康村 just outside Xi'an. The burial was part of a larger cemetery of commoners. In the caster's burial inventory, archaeologists uncovered a group of twenty-five molds, some of which were presumably used in the mass production of animal-style imagery; the design of one matrix in particular shows an ungulate with antlers terminating in birds recalling the steppe-inspired “syncretic antler” trope.Footnote 36 It is significant that the Chinese caster's tomb has yielded tools for the making of ritual Chinese bronzes as well as a matrix for animal-style production. Evidently, he catered to two distinct clienteles and markets, a Chinese and a nomadic one, but conveniently used the casting technique for both. This composite is comprised of a winged horse with a horn which sprouts into an antler-like formation and terminates into the familiar bird heads in profile (Figure 9). It is then finished in the traditional steppe “braided rope” pattern, seen across Ordos burials. The Beikangcun composite is especially akin to the Nalin'gaotu beast because in both instances, the raptor head reappears toward the animal's tail and even feet, not just at the antlers—this is yet another regional reinterpretation of the original trope. Anatomical functions and part–whole relations are reconfigured, the bird's head takes the place of what a viewer would expect to be a tail. Yet again, ideation is fully disrupted. The syncretic antler trope is a not-so-distant echo of a widely understood and circulated animal-style visuality which, around the fourth century b.c.e., started to take noticeably firmer roots in Chinese material culture. Likely seeking to satisfy the demands of the lucrative nomadic market, the caster had to study and understand the conceptual, as well as structural and material value of the animal-style formula along with its distinct tropes and idioms. This newly acquired understanding came about as a result of the changing economic dynamics in China and nomadic Inner Asia, whose increased interdependency at the end of the Warring States was becoming evident to both sides.

Figure 9. Animal-style matrix, Beikangcun. Warring States period.

Source: Shaanxi sheng kaogu yanjiusuo, “Xi'an beijiao Zhanguo zhutong gongjiang mu fajue jianbao,” Wenwu 2003.9, 8.

“Sinicized” Animal-Style Tropes: Visual Parallelism

Starting from the Warring States, steppe nomads were becoming an enticing market whose tastes and demands Chinese makers needed to study and fulfill out of economic expediency. The new market opened new possibilities. Chinese makers did not blindly copy animal-style designs. Instead, they took some fundamental and familiar concepts in zoomorphism as steppingstones toward the construction of new tropes. This is how a new regional “topolect” of the animal-style visual language emerged in north China: there, we continuously encounter bilateral reflectivity, a sort of visual parallelism which favors the mirrored depictions of abstracted zoomorphic bodies. The parallelism trope is China's own contribution to the visual rhetoric of the steppe, and one which seems to have been indeed preferable to Chinese makers, and not widely embraced elsewhere along the steppe network.Footnote 37 The question is: why?

The vertical parallelism trope was not only adopted across the Ordos zone but also in places like Xinzhuangtou in the state of Yan and even at Majiayuan where a gold object resembling the zoomorphic “taotie” mask was unearthed, displaying a fusion of the traditional Chinese zoomorphism of ritual bronzes with the steppe-inspired materiality of goldwork.Footnote 38 In this new mode of expression, twin beasts appear reflected along a well-delineated vertical axis. A pair of gold plaques from Aluchaideng most prominently features this device (Figure 10a and 10b). The imagery is constructed around a vertical line along which zoomorphic structures unfold on opposite sides, creating mirrored images. Highly stylized felines bite onto the backs of oxen. These bodies mark a return to earlier approaches to zoomorphism—animals are abridged, highly abstracted and hardly recognizable.Footnote 39

Figure 10a. Gold plaques. Aluchaideng, Inner Mongolia, Fifth to third century b.c.e.

Source: Zhongguo meishu quanji bianji weiyuanhui, Yuanshi shehui zhi zhanguo diaosu. Zhongguo meishu quanji, diaosu bian 1 (Taipei: Jinxiu, 1989), 177.

Figure 10b. Gold buckle. M18, Majiayuan tombs.

Source: Xirong yi zhen: Majiayuan Zhanguo mudi chutu wenwu, 50.

The northern pastoralists of the Ordos cultural zone readily and consistently adopted this trope, We see a similar approach to the decoration of several plaques from Xigoupan, yet another site which has yielded plaques and buckles consistent with steppe style and easily differentiable from the predominant styles in the Central Plains.Footnote 40 The Xigoupan cemetery's zoomorphic inventory provides some useful examples which directly link China to animal-style production: along with the plaques featuring reflected, symmetrically positioned horses and deer, a return to the syncretic antler with bird terminals is also present, though slightly reinterpreted. One of the Xigoupan plaques features an ungulate in profile with a bird's beak and extremely stylized, curvilinear antlers with terminals mimicking the curvature of the beakFootnote 41 (See Figure 11, nos. 7 and 10). Another (Figure 11, no. 1) has entangled beasts on the front and Chinese characters on the back, thus indicating that the object was likely manufactured in the Chinese imperial workshops. Four plaques feature reflected angulates in the manner observed on a nomadic plaque from the Metropolitan Museum's Ancient China collection, said to have come from the Eastern Steppe zone. The MET buckle echoes the reflected entanglement of an ibex and a feline from Aluchaideng. The view faces visually parallel anatomical configurations, which, in keeping with steppe image-making, remain abridged and entwined to the extent of unrecognizability (Figure 12).

Figure 11. Inventory from the Warring-States site of Xigoupan, Inner Mongolia.

Source: Yikezhaomeng wenwu gongzuozhan, “Xigoupan Xiongnu mu” Wenwu 1980.7, figs. 2–4

Figure 12. A buckle with paired felines attacking ibexes, Fifth to third century b.c.e. Gold.

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Database, New York

A return to the Beikangcun cemetery further illuminates the development of this “parallelism” trope. Along with the matrix of a zoomorphic juncture, a few other plates and terracotta molds for animal-style decor were found in the craftsman's tomb. Two objects have a unique triangular shape, and one bears a striking similarity to the Aluchaideng piece, also featuring predation scenes along a reflective vertical axis (Figure 13). Living at the fringes of the Ordos Cultural Zone, the Beikangcun craftsman understood the new applications of animal-style design in the constantly evolving material culture in China. Animals are extremely abbreviated and stylized on the triangular plates, and references to tigers, oxen, and goats are made repeatedly in a pars-pro-toto or a related metonymic mode. The preoccupation of Chinese and Eastern Steppe artisans with verticality and parallelism was not shared by their Western and Kazakh Steppe counterparts. The visual parallelism trope is not encountered frequently outside the Eastern Steppe where it enjoyed especially high popularity. Notable exceptions are the reflected beasts on diadems from Ulandryk and Tashanta of the Pazyryk culture.Footnote 42 However, these are rare instances; in the Pazyryk archaeological cluster and the general Altai-Tuva domain the bilateral symmetry trope is not adopted nearly as often as in the communities living along the northern Chinese periphery.

Figure 13. More articles from Beikangcun. Suburbs of Xi'an. Warring States.

Source: Shaanxi sheng kaogu yanjiusuo, “Xi'an beijiao Zhanguo zhutong gongjiang mu fajue jianbao,” Wenwu 2003.9, 8.

Why did steppe-inspired images have to be reflected and mirrored in the north Chinese vocabulary? Seasoned Chinese designers must have invented this new “parallelism” trope because of how close it was to their own expertise with bronzes. Stylized and fragmented zoomorphs reflected along a vertical axis are at the heart of Shang vessel design. Numerous Erlitou bronze plaques with turquoise inlay convey a similar approach to zoomorphic bodiesFootnote 43 (Figure 14). Like on the steppe examples, the parallel structures are not simple life-like animals mirrored on opposite sides of an axis; rather, they are incomplete, highly stylized zoomorphs rendered in a pro-forma fashion. From the onset of the Shang, such zoomorphic imagery became widespread in the Chinese imperial center and continued to thrive into the succeeding Zhou dynasty despite all the undeniable shifts in ritual bronze design previously outlined and debated by Bagley, Loehr, and others.Footnote 44 The “inception” of Chinese zoomorphic bodies clearly precedes that of nomadic animal-style design by many centuries. During the Eastern Zhou, one starts to notice the further proliferation of steppe-inspired zoomorphism and its frequent encounters with existing Chinese designs and image systems. For example, a mold for a bell exhibiting the symmetrical animal-mask motif, often referred to as “taotie,” was discovered at the famous Houma foundry established by the State of Jin in the sixth century b.c.e. (Figure 15). At this site associated with several generations of ancient Chinese patrons, archaeologists managed to unearth hundreds of pattern blocks and decorative clay models like the example shown in Figure 15.Footnote 45 Chinese artisans were clearly comfortable with conceptual designs rooted in unfinished, stylized, abbreviated, and metonymically rendered bodies, and their logical modularity was only further enhanced by the underlying principles of the piece-mold technique. It is thus unsurprising that bronze casters like the deceased from Beikangcun specialized in catering to the tastes of both Chinese and steppe customers: an experienced caster would have found it easy to transition from gold to bronze (and vice versa), and he would have also understood the loosely shared zoomorphism which he could then translate into what he was already comfortable with in his own skillset. Naturally, the artisan was fulfilling the demands of two very different types of clients, whose understanding of zoomorphism was perhaps different but not necessarily unrelated—the Chinese visual corpus was, after all, primarily zoomorphic and so was that of their nomadic rivals. Overall, early China was much more receptive to animal-style zoomorphism and could buy more heavily into the steppe market than, say, Persia or Greece could, because China and the nomadic sphere shared a certain proclivity for zoomorphic visuality and stylization of animal forms that artisans and patrons in other Eurasian cultures did not. China's reliance on zoomorphism thus became one of its economic and political strengths, particularly when dealing with the nomadic world.

Figure 14. Bronze plaques with turquoise inlay. Erlitou civilization. Yanshi, Henan province.

Source: Allan Sarah, ed. The Formation of Chinese Civilization: An Archaeological Perspective (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 148, Figure 6.7

Figure 15. Mold for a bell. Houma foundry. State of Jin, Sixth b.c.e., Shanxi province.

Source: Yang Xiaoneng, New Perspectives on China's Past: Twentieth-Century Chinese Archaeology (New Heaven: Yale University Press, 2004), 185.

Dissemination in the Han Dynasty: Animal Style Travels South

In the Warring States, these newly developed animal-style variants emerged predominantly in the beifang region nested between the Eastern Steppe proper and the Chinese dynastic domain. In the Han dynasty, animal-style design tropes continued to permeate Chinese funerary art and design, reaching much farther south into regions that had been historically isolated from developments in the fluid northern border. Examples of the wider dissemination in the Han dynasty come from the Shizishan princely tomb located in Xuzhou where a nobleman was buried with a great number of traditional Chinese objects, including jades and ritual bronzes. The Shizishan tomb is part of the larger elite complex of Liu Bang's clan, located near the ancient Chu capital of Pengcheng, where each tomb is named after the respective hill on which it was found—Shizishan, Beidongshan, Chuwangshan, Dongdongshan, Tuolanshan, Yangguishan.Footnote 46 All tombs have long squared off access passages, with chambers on each side, and some of them even have subsidiary chambers.Footnote 47 Along with jade cups, personal ornaments, and a traditional Han-dynasty jade burial suit, a number of animal-style plaques were also located at Shizhishan (Figure 16). Here, the buckle's design features a tiger and a bear devouring a horse. Encircled within an entanglement of contours and a flurry of incomprehensible shapes, the horse is in fact not “real” or complete but rather a brief signifier of an imagined anatomy—his head sprouts into deer antlers which in turn terminate into the familiar syncretic antler tropes seen elsewhere on the steppe.Footnote 48 The twisted ram motif also appears on plaques from the Xiongnu cemetery of Daodunzi in Ningxia and Xichagou in Liaoning, where bronze ornaments feature similarly positioned contorted rams devoured by felines.Footnote 49 Like Ordos craftsmen, the artisan was fluent in the zoomorphic visual language of steppe nomads. They understood the particularities of its zoomorphism and created these objects with a specific formula in mind.

Figure 16. Buckle with a tiger and a bear attacking a horse, Shizishan princely tomb, Xuzhou, Jiangsu. Third to second century b.c.e.

Even more intriguing is a pair of gold buckles located at a female elite burial (no. 6) at Houloushan, also part of the Liu family's mausoleum in Xuzhou (Figure 17). It was quite rare to find a grassland-style object in a Chinese noblewoman's possession during the Warring States but not so much in the Han.Footnote 50 Since she was buried less than a hundred meters from the Chu king's tomb, the woman was likely his consort: she is identified as a member of the Liu family through a bronze seal.Footnote 51 She chose to be interred with a variety of objects from various cultural centers, including animal-style artworks. On one object, the braided rope pattern at the borders reminds us of buckles from Aluchaideng and Xigoupan in Ordos. Even more faithful to steppe visuality are the contorted ram bodies arranged in a row. The animals are not fully outlined but rather abbreviated, schematically rendered to the degree of extreme abstraction. One can decipher their identities through their heads and textured horns. One starts to consider the possibility that steppe zoomorphism penetrated much further into the heartland of the Han empire than has been hitherto assumed. To see references to animal-style art all the way in the Chu domain is astounding considering the vast distance from the northern frontier zone. During the Warring States, marked by China's first intensive encounters with the northern nomads, one observes a much more contained diffusion of steppe visuality and techniques—for the most part, animal-style portable luxuries were circulated in the Ordos Loop, Gansu, and Xinjiang—the regions normally associated with these types of cross-cultural encounters. This trajectory seems to have changed and its scope widened in the Western Han, especially as the Xiongnu became a serious geopolitical factor at the northern border, and trade routes expanded significantly.

Figure 17. Gold buckle. Houloushan, Tomb no. 6, Xuzhou, Jiangsu. Third to second century b.c.e.

The ram configuration from Xuzhou reappears on a buckle unearthed from a chance discovery from a now destroyed cemetery in Zhushan county 竹山縣in Hubei.Footnote 52 The buckle shown in Figure 18 is reminiscent of the Houloushan buckle with ram heads. One encounters the same contorted ram bodies at the lower portion of the object, topped by other rams with textured, upright horns sprouting into what appear to be bird heads in profile. The craftsman used embossing and openwork when marking the borders whereas the animal heads at the top appear to have been cast. The owner of this buckle was most likely a Chinese noble rather than a nomad—we have no records of nomadic presence in Hubei during or before the Han dynasty. One possibility is that the gold ornament belonged to the infamous prince-turned-serial killer Liu Pengli 劉彭離, a nephew of Emperor Jing. As Prince of Jidong, he allegedly murdered hundreds of civilians and their slaves in the night, causing people to fear walking after dark. According to the Shi ji, the emperor could not bear to have his own nephew killed, instead choosing to banish him to Shangyong or what is now Zhushan county in Hubei province.Footnote 53

Figure 18. Gold buckle, Zhushan county, Hubei province. Western Han.

Source: Wenwu 2010.9, inside cover top

An echo of northern nomadic aesthetics, the Zhushanxian example recalls numerous parallels in Ordos. Most notable are its design similarities with a bronze buckle excavated at the Xiongnu cemetery of Xichagou 西岔溝 in Liaoning provinceFootnote 54 (Figure 19). In the same manner, the artisan has chosen to construct a row of bird heads which seem to emanate from the main contorted bodies. In these parts of China, the tendency to fragment and re-imagine bodies is even more prevalent than at the heart of the steppe. Following the formulaic design strategy of the steppe, Chinese makers still took some liberties in the construction of fantastic beasts by subjecting their anatomies to excessive abstraction and reconfiguration.

Figure 19. Plaques from the Xichagou cemetery, Liaoning province, North China, Second to first century b.c.e.

Perhaps the most surprising trajectory of animal style in the Han is marked by the mausoleum of the second ruler of the Nanyue Kingdom in Guangzhou—a semi-independent state established at the southern periphery at the end of the Qin. Built of more than 750 slabs of sandstone, the kingly tomb features a multi-room plan, with side rooms surrounding both the front and main chambers.Footnote 55 This layout might be derived from the compartmented wooden chambers of Chu tombs in the south.Footnote 56 The tomb gate and walls were adorned with wall paintings following Han burial traditions, and the emperor's body was buried in a traditional Han jade suit. A seal found inside the tomb has an inscription which reads as “the administrative seal of Emperor Wen.” The inscription indicates that Zhao Mo 趙眜 (r. 137–122 b.c.e.) styled himself in the Han Chinese rather than in a foreign manner and likely saw himself as an equal to the Western Han emperor.Footnote 57 Various ritual bronze vessels, Han-style bronze mirrors, musical instruments, and jade ornaments were also located inside the king's final resting place, indicating the link with the funerary cultures of the Central Plains, Ba and Shu cultures of the upper Yangzi, the Wu and Yue cultures of the lower Yangzi, and the northern zone. Some objects stand out.

The gilt bronze plaque shown in Figure 20 features the steppe “braided rope” design at the borders.Footnote 58 It also presents a local translation of the trans-steppe zoomorphic entanglement trope, featuring the anatomies of turtles and a dragon. Pars-pro-toto gives way to a pro-forma mode of expression, as the main concern is no longer mere reduction of forms. Rather, forms become completely fluid, interchangeable, and non-representational—abstraction has completely taken over. While predation was at least alluded to on the Majiayuan piece, here the animal shapes are so abstruse and heavily stylized that the product in no way reminds the viewer of animal combat. The anatomical and taxonomical credibility have been completely removed from the scene; a zealous viewer might be able to untangle the parts of a dragon and a tortoise only after some seriously concerted efforts. The Nanyue piece represents a regional, or perhaps even local, adaptation of a broadly understood visual trope which had been coined in the nomadic cultural realm as early as Arzhan (eighth to seventh b.c.e.). Here the craftsman has opted for animals more strictly aligned with the Han worldview, such as the dragon and turtle; this shift in subject matter could be interpreted as a strategic remaking of animal style into a Sino-Steppe visuality.Footnote 59 Since the overall burial is akin to Chu practices, one can perhaps speak of a more broadly defined southern cultural zone during the Han, at least with regard to funerary rites and inventories. Interestingly, the extreme abstraction on this plaque is more closely related to the zoomorphic entanglements featured on plaques and buckles from the beifang zone (e.g. Majiayuan) than it is to the ram imagery at Xuzhou.

Figure 20. Ornament. Gilt bronze. Tomb of the Nanyue King. Western Han dynasty, Second century b.c.e.

Source: Huang Guangnan, Artifacts in the Nan Yue King's Tomb of Western Han Dynasty (Taipei: National Palace Museum, 1998), 138.

The parallelism trope is evident on other objects from the Nanyue tomb. Archeologists also found three buckles with paired-ram images reminiscent of the Xuzhou and Zhushanxian examples (Figure 21). Eight peach-shaped gold ornaments embellished the piece of cloth which covered the tomb occupant's face.Footnote 60 Goats with sharp horns are positioned along a vertical axis on each– the animals are sufficiently schematic and condensed to warrant a comparison with steppe animal-style, also recalling similar examples from the Han tomb in Mancheng in Hebei and a similar imperial tomb from Dayunshun in Jiangsu.

Figure 21. Tomb of Nanyue King gold decoration. Guangzhou. Gold decoration.

Source: Huang Guangnan, Artifacts in the Nan Yue King's Tomb of Western Han Dynasty (Taipei: National Palace Museum, 1998), 83.

As noted earlier, it must have been expedient for Chinese bronze casters to expand their knowledge and skill set to fit the needs of a new market niche by re-purposing and adapting already existing techniques and motifs. The original animal combat trope was filtered to the level of extreme abstraction and pro-forma expression precisely because this is what Chinese makers were already familiar with in their work with zoomorphic bronzes and jades. Structurally, the zoomorphic entanglements on the animal-style objects at Nanyue is not markedly different from that exhibited in the upper portion of the animal-faced jade pendant excavated from the same royal tomb. A jade “pei” ornament with openwork images of a dragon and a bird was also located amongst the Nanyue King's inventory; this abstract zoomorphism reappears on several of his sword terminals and a small bi disk with carved dragon and tiger shapes. The openwork abstraction here seems to be somewhere in the spectrum between Chinese and steppe zoomorphism, with apparent allusions to early bronze designs and possibly the Han-dynasty swirl motif, but also references to steppe-inspired composites. Most of the Nanyue pieces seem to show a fusion of animal-style and Han decorative elements. Evidently, such fusions were vastly popular with elite patrons and easily transferable to various media and formats.

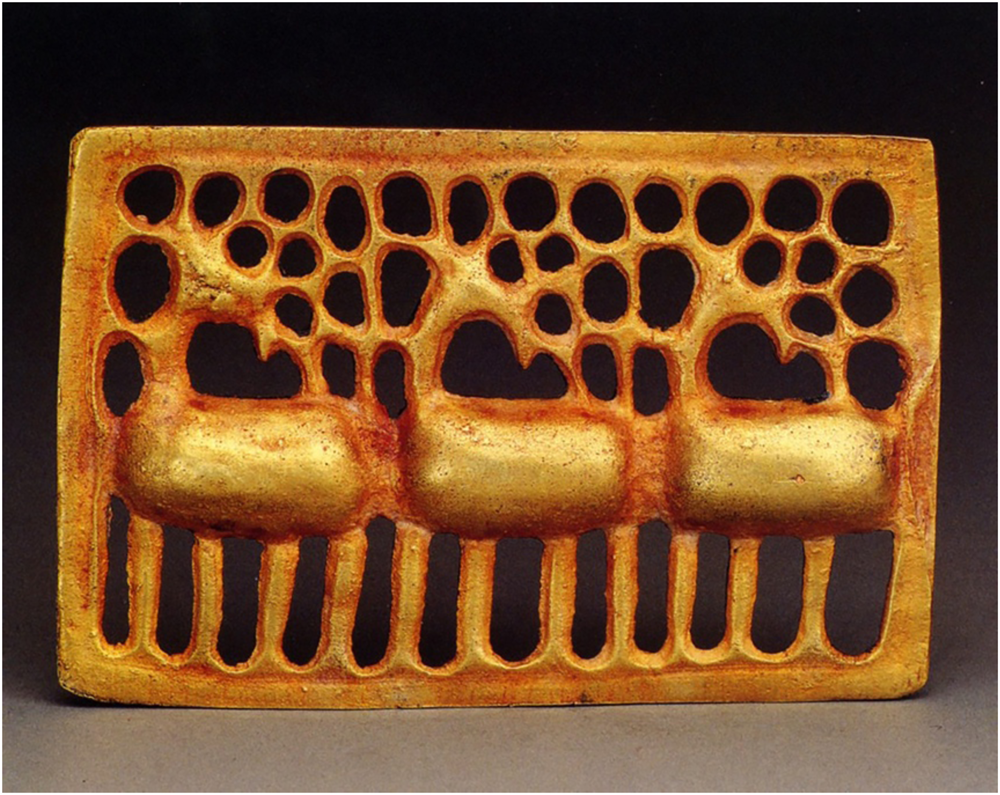

Speaking of transferability, zoomorphism reoccurs in certain architectural elements of the Nanyue complex, namely on a large palace foundation surrounded by an apron paved with bricks and pebbles.Footnote 61 Recent excavations yielded a number of architectural stone and pottery components there. One of them is the ornamental architectural brick shown in Figure 22.Footnote 62

Figure 22. Architectural molded brick. Royal gardens of the King of Nanyue. Third to second century b.c.e.

Source: Yang Xiaoneng, New Perspectives on China's Past, 262.

Squeezed into the surface is a molded animal body of what looks like a boar. It appears fragmented and condensed. Its animality is conveyed metonymically, through the introduction of representative anatomical components. Body parts are abbreviated, perhaps in a fashion slightly different from that of steppe pieces, but the result still echoes steppe design strategies and concepts. Once again, animality is alluded to rather than fully demonstrated. Interestingly, the animal here is depicted frontally rather than in profile as was the case with most steppe designs, perhaps a further indication of the Sinicization of steppe decorative schemata.

The presence of animal-style design tropes in the Chu and Nanyue cultural domains is telling. One would never have seen intrusions of steppe visuality so far south before the Han dynasty. After the third century b.c.e., both Chinese and steppe elites took an increasing interest in mutual commercial transactions. Their economic interactions must have increased the overall production and circulation of valuable gold objects, leading to surprising trajectories of transmission. Moreover, both Chinese and nomadic elites now defined themselves through various types of cultural capital and not simply through ritual vessels or tokens of their military achievements.Footnote 63 The occasional but not frequent occurrence of animal-style objects in the South leads to two conclusions. First, Chinese elites saw animal-style art as a signifier of “barbaric otherness”: thus, steppe zoomorphism served as a synecdoche in several different ways, replacing or reducing animal bodies, and also acting as a stand-in for the “Other” and for one's political clout. To the Han, gold zoomorphic items would have been easy to transport, sufficiently “foreign” yet familiar enough to fit the aesthetic system of traditional Chinese burials. These types of rare acquisitions by members of the Liu clan would have conditioned the funeral's audience to see them as worldly and highly connected to places beyond their immediate domain of influence. A shrewd strategy like this used foreign elements in visual culture to one's political and economic advantage, creating a sense of “governable otherness.” Secondly, one must not be overzealous in their quest for finding receptivity. Even in the Western Han the tastes and aesthetic demands of the Chinese dynastic lands and those of the steppe zone remained distinctly separate: one preferred large bronzes and jades and was never too fond of gold while the other saw golden portable items as inextricably linked to elitism and political clout. Therefore, we rarely see animal-style items in the tombs of mid-ranking officials in Central and South China; only members of the highest echelons would have had a reason to showcase their networks and power through syncretic burials and the occasional nod to steppe design.

Animal-Style in North Korea: The Case of Lelang (108 b.c.e.–313 c.e.)

In the Western Han, animal-style tropes reached other peripheries of the Han empire. Notably absent from most discourse on the subject is the Korean peninsula which came under Chinese control after Emperor Wu of Han defeated Gojoseon in 109 b.c.e. Chinese presence on the peninsula likely predates this event by at least a century, as indicated in the Shi ji. The Chinese chronicle tells us that the state of Gojoseon was already occupied by descendants of general Wiman who had arrived in Korea after a failed coup in the Yan state; he acted as a middleman in trade and diplomacy with the Han thereafter.Footnote 64 Most likely the northern Korean peninsula had seen resettlements from China even before its annexation by the Han dynasty. Lelang was a Han commandery located in modern-day North Korea.Footnote 65 The map below shows the distribution of Han-period tombs across Lelang—most are situated near present-day Pyongyang. Elite burial inventories are dominated by Chinese bronze mirrors, chariot pieces, Han administrative seals, and various agricultural tools; the majority follow the traditional Han tomb layout.Footnote 66 A great number of graves belong to Han Chinese officials, including generals and administrators stationed in Lelang, while a smaller number of tomb clusters constitute native burialsFootnote 67 (Figure 23).

Figure 23. Distribution of Han tombs in Lelang, North Korea. After Hyung II Pai 1992, 307.

Animal-style items make an appearance in several Lelang tombs. For instance, the chambers from Shiyanli 石岩里 (Seogam-ri) near Pyongyang have yielded a number of belt buckles with entwined dragon motifs. Han Chinese tomb occupants were placed in wooden-chambered tombs consistent with traditional Chinese layouts. Currently kept at the National Museum of Korea in Seoul, the object in Figure 24 was discovered at Shiyanli in 1916 during the Japanese colonial period (as is the case with most Lelang tombs). The buckle in question was originally placed on the occupant's belt. On the surface, a large dragon is surrounded by six smaller dragons. A line of thin gold beads was soldered onto a thin gold wire to emphasize the textured skin. Turquoise stones were then inlaid to further enhance those textures. The dragon's nostrils, horns, and eyes are formed by coils of gold wire, while the ears are expressed by discs of gold granules. Three large gold beads are attached to the dragon's forehead, two of which are encircled by gold wire.Footnote 68 Embossing and granulation are used frequently in Lelang design, which sets it apart from the more canonical steppe examples.

Figure 24. Buckle. Gold, L 9.4cm. First century. Nangnang 樂浪, Shiyanli tomb no. 9, North Korea. (Lelang) Commandery, Seogam-ri Tomb No.9, Korea. National Treasure No. 89.

Source: National Museum of Korea

Notable parallels to this object exist in north and central China. At the Bogedaqin site in Karasahr, an ancient Silk Road oasis, Chinese archaeologists uncovered a dragon buckle which bears a striking resemblance to the Shiyanli one.Footnote 69 This is unsurprising because, as part of the Western regions (Xiyu 西域) in the Tarim basin, Karasahr (Yanqi) was at a strategic spot which more than once found itself at the center of Han and Xiongnu rivalry in the region.Footnote 70 After losing Karasahr to the northern Xiongnu, China made several attempts to reestablish control there: in the year 75 c.e. the new protector general of the Western regions Chen Mu was killed by the Xiongnu allies in Karasahr and the Hami garrison was withdrawn.Footnote 71 As a result, the region of Karasahr came into contact with both Chinese and nomadic tastes and styles, hence the occurrence of a Sino-Steppe product in one of the funerary sites there.

A closely related silver buckle was discovered in tomb M219 at the Shiyanli complex. It also features the steppe braided rope design. Here, too, the object in question is embellished with a twisted dragon design. In fact, virtually all Lelang's belt buckles and plaques of the steppe formula feature dragon patterns as opposed to animals derived from steppe ecology. This is further attested in another important Han complex of wooden-chambered tombs in North Korea. At Zhenbaidong, M 92 and M2, have all yielded silver examples of dragon buckles while M37 contained a gold buckle with a silver frame (another rare implementation).Footnote 72

The examples excavated from Lelang tombs all have closely related parallels across China, and not only at Karasahr in Xinjiang. At the Western Jin funerary site at Anxiang, archeologists discovered the same granulated gold buckle with twisted dragons.Footnote 73 This is an isolated discovery in the Hunan area and one which defies the traditional diffusion narratives of steppe visuality. At the Western Han tomb at Yingchengzi in Dalian, archaeologists also unearthed a similar dragon-patterned buckle.Footnote 74 Inlaid with turquoise like its Korean counterparts, the item features the widest range of techniques so far: granulation, soldering, hammering, mold-pressing and the usage of strip-twisted wire. Such similarities are easily explainable when one considers the make-up of the population inhabiting present-day Liaoning region in and after the Western Han. Prior to the Han dynasty, this had already been a territory coinhabited by Donghu nomads and Korean tribal groups such as Yemaek and Choson. The Shi ji claims that upon Yan's territorial expansion under general Qin Kai, several commanderies were established in the region to defend against Hu attacks.Footnote 75 The interactions between Yan, Donghu and Choson in the area of Liaodong is also recorded in the Yantie lun (“Debates on Salt and Iron”) which indicates that Yan attacked the Donghu, opening up one thousand li of land, and then proceeding to attack Choson.Footnote 76 It was exactly the Donghu who circulated and popularized animal-style design along the northern frontier zone of China between the fifth and third century b.c.e. It is likely that they had already brought animal-style visuality to the Liaoning area toward the end of the Warring States. Thus, these regional Sino-steppe topolects in the Liaodong peninsula are indebted to the intensive interactions of Donghu, Korean and Chinese officials in an area which was a hotbed for cultural and military exchanges from the Warring States onward. In the Han dynasty, northeastern China, namely the Dalian area, became a conduit for expansion in North Asia.

Some belt buckles of the newly developed Sino-Steppe formula start to feature new materials and modes of making that are more consistent with Chinese traditions than they are with steppe conventions. A jade example of a dragon buckle was excavated from the Eastern Han tomb at Jiamaying near the capital Luoyang.Footnote 77 In pre-Han times, jade was never the material of choice in animal-style items; although bronze substituted gold in graves belonging to mid-ranking Chinese nobles, metalwork was still the primary medium of animal style. A noticeable incursion of Chinese motifs and materials took place during the Western Han as animal-style themes started to represent indigenous Chinese ecology, mythology and making-practice rather than those of the steppe pastoralists. This is an important shift because it indicates the high level of receptivity in Western Han China, which found itself on the receiving end of this foreign visuality but also in a greater position to revisit it than were its Warring States predecessors for whom interactions with the nomadic world were still a relatively new, uncharted territory. The Sino-Steppe designs no longer featured imagined encounters between animals from the steppe biota, or junctures of zoomorphic allusions to that biota. Instead, they depicted fully fledged mythological beasts. Still preserved, however, is the general approach to zoomorphism, with dragon and other forms twisted, intertwined, and abbreviated.

Geometricization: A New Abstraction Mode

Along with the creation and consolidation of this new Sino-Steppe style, a separate shift in image-making took place in Western Han China and its northern geopolitical rival. The remains of the nomadic alliance of the Xiongnu (third to first century b.c.e.) in the Transbaikal region of South Siberia, Ordos Loop, Mongolia, and the Tarim basin show an increased interest in the visual synecdoche device in the decorative scheme of portable objects. Zoomorphic art was becoming increasingly standardized and less frequently “custom-made” for individual elites, pointing perhaps to the increasingly centralized structure of a sophisticated nomadic empire which was involved in numerous commercial transactions with their southern neighbor China and possibly polities further west. During the Xiongnu's rise to power (third to second century b.c.e.), animal style took a turn toward extreme abstraction and geometricization. Pars-pro-toto was replaced by a pro-forma mode of representation in which extremely schematic, mostly geometric renderings of animal anatomy were the norm. Most Xiongnu buckles and plaques were executed in openwork, with animal contours increasingly thinned out. The new vogue was to represent anatomical parts more abstractly than ever before – with meanders, circles or other geometric shapes that acted as stand-ins for body parts.

A closer look at the discoveries of Dyrestui, located in the Siberian republic of Buryatia, helps us understand the changes Iron-Age animal style underwent under the Xiongnu hegemony. Figure 25 shows plaques and buckles in openwork that continue the themes and visual tropes established in the arts of the early Eurasian nomads. Some of the imagery (Figure 25, nos. 2 and 5,) indicate a return to the bilateral symmetry trope, presenting two twin animals reflected along a vertical axis. In a clear reference to the earlier syncretic antler / zoomorphic juncture tropes, image no. 4 on the chart features a whimsical composite with a horse-deer body and antlers, terminating into bird heads (see Figure 25, no. 4). The majority of zoomorphic images are finished in openwork and often feature the steppe “braided rope” pattern. The contours are therefore significantly thinner and more “geometricized” than those in earlier Eastern steppe art. Evident also is the consistent utilization of the braided rope design, indebted to earlier Ordos trends.

Figure 25. Dyrestui burial inventory. Bronze objects. Second century b.c.e., Xiongnu period.

More recent Xiongnu discoveries come from other parts of South Siberia, such as Tuva, which was once home to the earliest steppe findings of Arzhan. On the left bank of the Upper Yenisei River, one would find a few tumuli consistent with the Xiongnu topology such as Ala-tey 1 (mostly containing pottery, bronze knives, and other weapons).Footnote 78 Terezin and Ala-tey 1 both contain examples of animal-style belt clasps, all of which could serve as representative examples of the Xiongnu animal style. Here, too, ornaments are finished in openwork, a technique which gives preference to contours and allows for smoother transitions between the entwined segments. A great many images are of reflected animals, an already well-established steppe trope in the Eastern Steppe, and a few repeat the commonplace scenes of animal-style predation and interlace (Figure 26). In some instances (Figure 26, nos. 1 and 2), individual animal parts such as antlers and beaks are so stylized and thin that they end up resembling foliage or other vegetal patterns, which is also mirrored in the braided pattern on the frame. A few plaques (Figure 26, nos. 5, 6 and 7) have marked a complete departure from animal imagery, instead featuring only repeated geometric patterns. In no. 5, two snake heads are visible at the terminals. The bodies of actual species are now replaced by geometric forms rather than single anatomical parts or other zoomorphic allusions as was the case in the early phase of animal style. Since these geometric plaques were deposited together with more traditional animal-style ornaments as part of the same adornment scheme, they signal a transition from the zoomorphic pars-pro-toto device to an utterly conceptual, geometric substitution. The new idiom reintroduces old modes of substitution and abbreviation but departs from previous application methods.

Figure 26. Bronze openwork plaques and buckles. Nos. 1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12: Ala -tey 1; No. 2, 5: Terezin; No. 4: Urbyun III; No. 8: chance find from Bulun Terek. Second to first century b.c.e., Xiognu period.

The Legacy of Iron-Age Animal-style: Xianbei Approaches to Animal Style

It is significant that the Han dynasty oversaw a shift in the earlier approach to zoomorphism because this change ushered in a new era for animal style in the post-Xiongnu period. It is assumed that animal-style art, and its various offshoots, died out with the disappearance of the Xiongnu and Sarmatians on, respectively, the Eastern and Western Steppe around the first century c.e. There is rarely any discussion of steppe zoomorphism after that: the general assumption is that the anthropomorphic stelaeFootnote 79 introduced by the Turkic Khaganates permanently replaced zoomorphic art on the steppe. Indeed, with the ascension of the first Türks (Tujue 突厥) in the early Middle Ages, most Central Eurasian communities, including pastoral nomads, transitioned to strikingly different burial customs and layouts. Be that as it may, the period between the third and sixth century was marked by innovations in animal-style, at least along the Chinese northern periphery. While there certainly was a period of waning in the production and circulation of animal style after the fall of the Xiongnu, the Turkic Xianbei 鮮卑 who replaced the Xiongnu along China's northern frontier continued to adapt earlier steppe systems of imagery until the rise of the Northern Wei. Likely descendants of the Eastern Hu, various branches of the Xianbei split off from the original nomadic alliance and started to dominate different parts of present-day north China and Mongolia before their ultimate consolidation by the Tuoba clan who established the Northern Wei (386–535) dynasty.

The Wei shu 魏書 and the Hou Han shu 後漢書 provide scattered records of the nomadic group. The Wei shu demarcates the territory of the Xianbei as stretching from the Liao River in the east to the Western regions to the west. (其地東接遼水,西當西城).Footnote 80 The texts make multiple references to the Xianbei's agricultural activities and products, which are indicative of their relationship with the surrounding biota. They linked the gestation and birthing practices of birds and beasts according to the passage of the four seasons; in cultivating the land, they always made use of the cuckoo for the purpose of timing.Footnote 81 As for their husbandry, the textual record in Hou Han shu lists the animals they used in daily activities: “The animals of the Xianbei differ from those in the Central States, consisting of wild horses, sheep, and saiga antelopes the horns of which are used in the making of bows, customarily named ‘horn bows’. They (the Xianbei) also have marten, na, and hunzi, the furs of which are soft and elastic. They are thus known among all under Heaven for their famous fur garments.”Footnote 82 More information appears in Wei shu's “Lingzheng zhi” 靈徵志 divided into two sections (shang 上 and xia 下), the latter describing the appearances of the spirit animal (shenshou 神獸), turtle (龜), giant elephant (巨象), white foxes (白狐), five-colored dog (五色狗), white deer (白鹿), one-antlered deer (一角鹿), white wolf (白狼), white rabbit (白兔) and more than ten kinds of different birds; in addition, the opening paragraph outlines the anecdote related to the appearance of the auspicious beast, the shenshou spirit shaped like a horse with a cow-like voice.Footnote 83 Zoomorphic junctures continued to occupy the imagination of the pastoral nomadic alliance in the Eastern Steppe even after the Xiongnu period, but now the imagined beasts are consistent with earlier Chinese theriomorphic composites. Wei Shou's preface to the text makes it apparent that the historiographical treatment of the Tuoba Xianbei would be vastly different from previous treatments of northern non-Han groups by suggesting that the rise of the Northern Wei was mandated by Heaven and the Xianbei themselves were descendants of the Yellow emperor.Footnote 84 The Xianbei welcomed their prescribed role and unsurprisingly, further developed the Sino-Steppe translation of the animal-style formula. While the Xiongnu and earlier nomadic groups were always viewed as “Barbarian Other” in Chinese thought, discourse was much different now that the Xianbei came to occupy the frontier.

Unlike the purely zoomorphic imagery from previous periods, Xianbei depictions overtly emphasize the relationship between fauna and flora. Stylized foliage started to play a major part in animal style. They also developed the Xiongnu geometricization trend further, rendering as foliage patterns as schematic meanders or coils in openwork. In Xianbei tombs, there are multiple examples of gold plaques of three identical deer whose heads are intertwined with abstracted foliage. An example from southeastern Inner Mongolia is cast in gold in the lost-wax technique (Figure 27). The image depicts three stags in a single row. Several closely related examples exist in the collection of Ordos-style bronzes at the Penn Museum—based on the emphasis on thinned contours and vegetation they should be dated to the late Xiongnu or possibly early Xianbei period.Footnote 85 In fact, much of the so-called “Ordos” material scattered in museums in Inner Mongolia, the US, and Europe can be reconsidered in light of this important stylistic difference; it is only in the Xiongnu and Xianbei phase in north China that this regional variant of animal-style design flourishes.Footnote 86 Thinned out and schematically abbreviated, the deer contours sprout in equally stylized branches rather than whole new animals as was the case with the animal style in previous periods. A tendency to accentuate vegetal motifs can also be observed in the opulent Xianbei headdresses of the elite. They are decorated with a combination of openwork and pendant gold leaves attached by wires, some taking the form of trees or antlers, or both.Footnote 87 Such animal-style elements were also transferred to other media, namely tomb murals at Yunboli and other elite burials where fantastic beasts on the wall paintings mirror those on Xianbei metalwork and appear in the midst of vegetation or even realistic landscapes.Footnote 88

Figure 27. Gold Plaque with Three Deer from Jingtan Village, Chayouhou Banner, Wulanchabu City. 265–316.

Source: Caoyuan wenhua: youmu minzu de guangkuo wutai (Xianggang: Shangwu yinshuguan, 1996), 125, cat.136

Even when vegetation is absent, zoomorphism takes on a new mode of representation with a stronger emphasis on geometric forms and contours mimicking vegetation. A Western Jin tomb from Inner Mongolia provides another helpful example. The buckle is a composite of a dog and a tiger (Figure 28). On the rims one notices the braided rope design seen on much of the earlier goldwork. Hammered onto the surface are also reliefs of schematically rendered animal heads (possibly of boars). Various coils and swirls in openwork are added toward the edges of this configuration.Footnote 89 Overall, this image structure offers a strong parallel with several Scythian examples from the Crimean aristocratic kurgan cluster. The Kul'oba buckle shown in Figure 29 follows a similar arrangement and take on animality: several smaller homomorphic outlines are rendered in relief within the larger recumbent animal. The Western Jin example, along with most of Xianbei-type goldwork from early medieval China, showcases a new “topolect” of the original shared idiom.

Figure 28. Gold Ornament in the Shape of a Tiger and Dog from Xiaobazitan Site, Liangcheng County Wulanchabu City. 265–316.

Source: Chengjisihan: Zhongguo gudai beifang caoyuan youmu wenhua (Beijing: Beijing chubanjituan, 2004), 143.

Figure 29. Scythian-stag plaque. Gold. Fifth century. Kul'oba barrow, Crimea.

Source: State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

Such a strong interest in vegetation could point to a growing incursion of traditional Chinese motifs into the Eastern Steppe visual vocabulary. Trees and other vegetal patterns dominate the repertoire of whimsical beings in various Classical Chinese texts, from the Shanhai jing 山海經 (approx. fourth century b.c.e.) to Soushen ji 搜神記 (fourth century c.e.). One is reminded of the peculiar penghou 彭侯 creature introduced both in the Soushen ji and the later herbology volume Bencao gangmu 本草綱目 (Compendium of Materia Medica) as a monster which sprawled from the core of a tree.Footnote 90 While the original record is no longer in existence, the extract about penghou is mentioned in a Dunhuang manuscript (P2682) which refers to it as a “creature that has evolved out of the essence of wood.”Footnote 91 Its supernational qualities are introduced through its tree-like quality and not through its animality. Naturally, these might be isolated examples not directly linked to the increased interest in landscapes and vegetation among the Xianbei, but they offer some initial evidence that flora became an increasingly pivotal component of zoomorphic visuality in north China during the Xianbei hegemony, likely the result of the nomads’ comparatively symbiotic interactions with Chinese subjects.

Animal-style Traces in Japan