How does theology, religious identity, and race interact in predicting political beliefs and behavior? The existing literature on race, politics, and religion extensively analyzes how one's experience as both a racialized subject and one's affiliation with a religious group predicts political behaviors and attitudes—from policy opinions to party ID (Koch Reference Koch2009; McCarthy et al. Reference McCarthy, Davis, Garand and Olson2016; McDaniel et al. Reference McDaniel, Dwidar and Calderon2018; Thomson and Froese, Reference Thomson and Froese2018). Among mainly—though not exclusively—Protestant Christians, the Prosperity Gospel (PG) is one notable theological compass that directs political attitudes and behaviors (Harris Reference Harris, Wolfe and Katznelson2010; McDaniel et al. Reference McDaniel, Dwidar and Calderon2018). The PG, a spiritual belief that connects material wealth to faith in God and upholds individualism over social justice, has gathered increasing support from Black Protestants in recent decades (Harris Reference Harris, Wolfe and Katznelson2010; McDaniel et al. Reference McDaniel, Dwidar and Calderon2018; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2016). For the most part, Black PG support has been linked to conservative political values and decreased support for social services and the Democratic Party, contrasting the long history of Black religious life anchored by social activism and collective spirituality (Koch Reference Koch2009; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2016). However, despite growing adherence to and prominence of PG beliefs, it is still an understudied topic in the religion and politics literature, especially as it cuts across racial lines and how it affects broader society (Djupe and Burge Reference Djupe and Burge2021).

While there are an increasing number of studies connecting the PG with race, much of the extant data comes from the pre-Trump era of American politics. Indeed, some of the best empirical work done on race and the political effects of PG beliefs come from data collected in 2012 or earlier (McDaniel Reference McDaniel2016, Reference McDaniel2019; Philpot and McDaniel Reference Philpot and McDaniel2020; Burge Reference Burge2017). There is still much for which we have only limited descriptive data, such as how many people of different racial and religious backgrounds identify with the PG and believe in its tenets, and how individuals' political affiliations and beliefs compare as a result. Additionally, while most scholars assess PG adherence by asking respondents whether they agree with a set of principles or possess certain beliefs associated with the PG, this is merely one way to assess PG involvement. There has been little data to examine the role of PG identity via belonging to a church or group that preaches PG messages. To this literature we add analyses from a unique data set from a high quality, nationally representative 2018 sample that asks respondents about their PG group membership as well as their PG beliefs to better understand how the PG interacts with race to predict economic and political attitudes, partisanship, and vote choice. These analyses are especially relevant in the context of the presidency of Donald J. Trump, a man who is emblematic of many PG values and counts as his “spiritual advisor” Paula White, a well-known preacher of PG religious principles who is ever ready to connect those principles to support for Trumpian policies and politics. In sum, this paper will provide updated data and an expanded approach to measuring the effects of the PG and race on politics during a time in which these issues are especially relevant.

Race, Politics, and the Prosperity Gospel

For Black Americans, political achievements such as the abolition of slavery and civil rights have been facilitated by the mobilizing force of Black religious life. For most of the twentieth century, Black politico-religious life was thought to be undergirded by the Social Gospel—a spiritual devotion to social justice that linked individual growth to Black collective progress (Mitchem Reference Mitchem2007; Harris Reference Harris, Wolfe and Katznelson2010). By the 1980s, the combination of privatized and dwindling social services, the rebranding of American individualism targeted to a burgeoning Black middle class, and the crackdown on Black radical activism introduced a new theological anchor to Black religion and politics (Harris Reference Harris, Wolfe and Katznelson2010; Wrenn Reference Wrenn2019). The PG—personified by religious and media figures such as Creflo Dollar and Frederick K.C. Price who insist on the power of praying one's way to wealth and personal prosperity—represents the marriage between modern neoliberal capitalism and spirituality, as theorized by economist Mary V. Wrenn who describes the PG as a neoliberal variation on Pentecostalism (Bowler Reference Bowler2013; Wrenn Reference Wrenn2019).

PG supporters often attribute the rise of social and economic precarity to individual shortcomings as opposed to social systems or institutional changes (Walton Reference Walton2009; Dougherty et al. Reference Dougherty, Neubert and Park2019; Wrenn Reference Wrenn2019). It is important to note that Black PG supporters are not simply Blacks that have ascended to the middle-class and above and credit themselves for their success. Working-class and less-educated Blacks aspiring to climb the economic ladder subscribe to PG theology much more often than their more educated, wealthier peers (Schieman and Jung, Reference Schieman and Jung2012; Wrenn Reference Wrenn2019). As many scholars have shown, the popularity of PG has prompted a measurable and complex growth in support for conservatism and the Republican Party among Black Protestants (Koch Reference Koch2009; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2016). While most Black Protestants continue to support a Social Gospel outlook when engaging in politics, the growing number of Black PG supporters that believe in conservative policies and identify with the Republican Party illuminate the complex and often competing theological guides within Black religious life and potentially signal the decline in the Black church as a vehicle for collective social activism (Koch Reference Koch2009; Harris Reference Harris, Wolfe and Katznelson2010; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2016; Burge Reference Burge2017).

As a result, it is challenging to make universal statements about the political identities and behaviors of Black PG Protestants, in no small part because a vast literature reveals incongruities between party ID and political ideology among Black voters, especially compared to their white and Hispanic evangelical counterparts (Koch Reference Koch2009; McCarthy, et al. Reference McCarthy, Davis, Garand and Olson2016; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2016; McDaniel et al. Reference McDaniel, Dwidar and Calderon2018; Burge and Djupe Reference Burge and Djupe2019). Hakeem Jefferson's “The Curious Case of Black Conservatives” suggests that the very notion of American conservatism and the normative 7-point Liberal-Conservative scale are ill-equipped metrics to appropriately describe how Black voters understand and identify with political attitudes and behaviors (Jefferson Reference Jefferson2020). Jefferson analyzes 2012 ANES data of Black respondents to demonstrate how 90% identify as Democrats while only 47.5% would also say they are liberal. He terms this discrepant political effect the “partisan-ideology paradox,” whereby a lack of ideological awareness can lead to inconsistent identification across political parties and ideologies (Jefferson Reference Jefferson2020). However, he argues that this paradox is not simply due to a lack of political education, but a reflection of disciplinary shortcomings of American political science to not account for the many social factors that inform Black understandings of party ID and political ideology within traditional methods of measuring political identification.

Ismail White and Chryl Laird's recent book Steadfast Democrats provides numerous examples of the complexity of party ID and political ideology as socio-political forces for Black Americans. They show how Black citizens, many of whom identify as conservative and might benefit from typically conservative Republican economic policies such as lower taxes, maintain support for the Democratic Party as a result of what they term “racialized social constraint” (White and Laird Reference White and Laird2020). They detail how for those Black citizens that have vested economic interests and individual financial incentives to vote for conservative and Republican policies, they instead largely support liberal and Democratic policies to preserve their social bonds with other Blacks and positively impact a national Black collective. Thus, White and Laird, along with Jefferson, reveal that Black conceptions of ideology, party ID, and political attitudes are richly and complexly informed by social factors, and they invite scholars to consider how other social factors such as religious identity may come to paint a dynamic picture of contemporary politics across racial groups. As we will argue, shared theological frameworks may nonetheless have very different political effects for believers of different racial identities.

Sociologist Bradley Koch notes how the political effectiveness of the Black church has long been an opportunity for Blacks to make economic demands and advances through grassroots mobilization where traditional American political structures otherwise stripped them of upward mobility (Koch Reference Koch2009). Koch describes the political significance of the Black church as a product of Blacks' political “exclusion” from the American government. In this context of political exclusion, it becomes clear why theological guides for upward mobility, whether they focus on the collective (Social Gospel) or individual (PG), might have particular appeal for Blacks and other historically marginalized groups.

While Black Protestants traditionally have tended to deemphasize the role of individualism, Weberian Protestant values, and asceticism in their religious outlook, Hispanic Evangelicals in America have taken up the promise of work ethic faith to envision their own “American dreams” (Lin Reference Lin2020). That is, until recently. As Tony Tian-Ren Lin notes in his text Prosperity Gospel Latinos, the Hispanic Evangelical community in America, traditionally oriented toward classic ideas of hard work as faith, have started to expand their theological toolbox, allowing PG tenets to motivate their pursuit for upward mobility (Lin Reference Lin2020). Lin suggests that the power of the PG for Hispanics lies in its ability to promise an aspirational financial boon while preserving American individualism, a strong antithesis to Latinx liberation theology (which is comparable to the Social Gospel within Black Protestant theology).

Putting this literature together, we expect PG support to be driven in no small part by race. Specifically, we predict that Blacks and Hispanics will be more supportive of the PG compared to whites, who have traditionally been able to achieve upward economic and social mobility through the normative promises of Weberian hard work and formal political participatory channels such as voting (hypothesis 1).Footnote 1 As we noted above, there is little hard data on the prevalence of PG identity or beliefs broken down by racial group. But Burge (Reference Burge2017) analyzes two questions from the 2012 General Social Survey that indirectly get at PG theology by asking the extent to which the respondent reads their holy book to learn about wealth, prosperity, health, and healing. He finds that PG theology is highest among Black Protestants, Democrats, and those with low income. So while Black Protestants have a long Social Gospel tradition that may push against the individualistic precepts of the PG, there is some prior evidence to suggest that they will also be more likely than white Christians to adopt PG beliefs.

Assuming that race drives PG adherence, how do these theological positions affect politics for different racial groups? While the literature outlines a potential shift in the political behaviors of younger white evangelicals, the historical and political trajectory of white evangelicals across recent decades is consistently conservative and Republican (Patrikios Reference Patrikios2013; Smidt Reference Smidt2013; Djupe and Claassen Reference Djupe and Claassen2018; Miller Reference Miller2018). Some scholars suggest that, similar to Black Protestants, white evangelicalism should be understood as a social movement that mobilizes theology for the explicit purposes of directing evangelical political life (McDaniel and Ellington Reference McDaniel and Ellington2008). Considering how entwined politics and theology are, and how racial identity amplifies this bond, it is vital to untangle the complex relationship between race, religion, and politics. For example, while Black Protestants and white evangelicals share many conservative religious and political attitudes, their theology is applied in very different ways politically, leading to often opposing partisan identities and policy stances (Burge and Djupe Reference Burge and Djupe2019). Also distinct from white evangelicals, Hispanic Christians have a social and religious history that has uniquely shaped their political worldviews. This connection is made more complex by the diversity of Hispanic identities, national origins, and beliefs, especially the dramatic theological and increasingly relevant political divides between Hispanic Catholics and Hispanic Evangelicals (Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Allen Gershon, Pantoja, Claassen and Djupe2018; Molina Reference Molina2020). In sum, we argue that the political implications of the PG will differ based on race and—especially for whites and Hispanics—religious tradition.

Given social and economic changes, combined with growing income inequality, the PG has emerged as an optimistic theology for people across denominational and racial lines, potentially forming a tenuous multi-racial political coalition. The PG has extended its influence into high office—to President Donald J. Trump. After the 2016 Presidential election, some scholars and pundits described President Trump as a “Prosperity Gospel President,” connecting earthly victories with spiritual blessings and supporting PG figures such as Joel Osteen and his own personal pastor, Paula White (Rogers-Vaughn Reference Rogers-Vaughn2019; Lewis and Timmons Reference Lewis and Timmons2020). Making sense of the theological and political complexity of PG supporters in the age of Trump—a President who connects faith with wealth and American individualism while also making notoriously flagrant racial statements—may reveal much about the trajectory of religious and political life today, especially for nonwhite believers (Rogers-Vaughn Reference Rogers-Vaughn2019; Lewis and Timmons Reference Lewis and Timmons2020; Lin Reference Lin2020).

Finally, to understand the complex relationship between religion, race, and politics, it is important to distinguish between beliefs and identities. Religious beliefs entail general opinions and values that individuals have about the relationship between the divine and their world (Djupe and Burge Reference Djupe and Burge2021). Religious identity suggests a more salient and consistent adoption of those beliefs that often translates into forms of self-identification and social engagement such as belonging to a church community. Some scholars assess religious beliefs with affective measures, investigating how one's view of God as punitive or benevolent influences one's personal behavior and trust in God (Mencken et al. Reference Mencken, Bader and Embry2009; Shepperd et al. Reference Shepperd, Pogge, Lipsey, Miller and Webster2019). Most literature about PG supporters and its political consequences measures PG beliefs or attitudes rather than PG identity. For example, expressing PG beliefs has been linked to increased entrepreneurial activity in the workplace and support for the creation of new businesses (Ferguson et al. Reference Ferguson, Dougherty and Neubert2014; Dougherty et al. Reference Dougherty, Neubert and Park2019). Agreeing with PG beliefs can lead to less political engagement for Black PG supporters compared to their Black peers that support the Social Gospel (Philpot and McDaniel Reference Philpot and McDaniel2020). Thus, religious beliefs help to shape worldviews which can inform political attitudes or behaviors and help one identify with a particular track of theological thought. Using a measure of PG belief can help convey a more general sense of PG support among the American public. However, belief in PG tenets does not necessarily indicate that one belongs to a PG church or group and may underestimate the role of the PG as a socio-religious ordering principle. In order to enrich the existing literature about the origins and effects of the PG, we measure both PG beliefs and PG identity to contextualize white, Black, and Hispanic PG supporters' economic policy attitudes in the Trump era.

Putting together the literature discussed above, we ultimately expect that PG theology and identity will generally push Americans in a more individualistic, materialistic, and consumer-focused direction that is consonant with support for Donald Trump, the modern Republican Party, and political conservatism (hypothesis 2). However, we also expect that complex sociocultural forces such as White and Laird's “racialized social constraint” will have a countervailing effect on the application of Black and Hispanic PG identity/beliefs to political outcomes. We specifically anticipate higher support for liberal economic policies, social welfare, and the Democratic Party among nonwhite PG adherents compared to white PG adherents (hypothesis 3). That is, while the inputs of racial identity, religiosity, and the PG should collectively push whites in the same direction (toward Trump, conservative policy opinions, and Republican identity), the effect of these same inputs for Blacks and Hispanics—especially Hispanic Evangelicals—on politics will likely be more complex, as racial solidarity and socio-economic status likely represent cross-cutting cleavages with PG beliefs. In other words, will a Black Protestant who follows the PG behave politically more like a white PG follower, or like a Black Protestant who does not adhere to the PG? Will Hispanics face similar dynamics, and how will the effects differ between Hispanic Catholics and Evangelicals? Our key prediction is that racial and PG cross-pressures will be evident for racial minorities, while for whites the PG will simply magnify a predisposition to individualistic, capitalist-friendly ideology that predicts conservative beliefs and voting behavior.

Data and Methods

Our data come from a July 2018 survey implemented and collected by Qualtrics Panels. While not a simple random sample, the data come from a massive opt-in collection of Americans 18+ that allows for constructing a sample that reflects a broad, representative swath of citizens. Our final sample of 1,892 was designed to fill quotas matched to the Census based on race, Christian identification, age, and gender. Data quality checks were implemented to ensure a high rate of valid responses. Respondents were asked a series of questions about their religious beliefs/behaviors, economic and political attitudes, personal financial habits, questions related to the PG, and the usual battery of demographics.

In order to assess PG identity, respondents were first asked: “Are you aware of Christian churches and groups that emphasize God's gift of personal prosperity to his followers?” The 47.25% of respondents who answered “Yes,” were then asked whether they considered themselves a member of such a church or group. Of those familiar with the PG, nearly 31% (277 respondents) said that they consider themselves a member. Thus, nearly 15% of the overall sample are coded as having PG belonging or identity.

We operationalized PG attitudes in three different ways, adopting the approach of a June 2006 Time Magazine poll that represented one of the most comprehensive efforts to measure PG adherence. First, we asked respondents: “Do you believe that God wants people to be financially prosperous?” Overall, nearly 43% of all respondents said yes to this question—which we consider emblematic of “soft” PG belief (Bowler Reference Bowler2013)—demonstrating the degree to which a religiously grounded prosperity mindset pervades the American public.Footnote 2 In other words, 28% of Americans who do not consider themselves members of a PG church nonetheless believe that God wishes people to financially prosper, showing the importance of analyzing both identity and belief. Second, we asked for people's attitudes toward the PG movement itself. Here, the movement has a 36.35% approval rate.

Lastly, we asked a battery of five questions that tap into “hard” PG beliefs, that is, beliefs that draw a direct line between one's faith and their material circumstances (Bowler Reference Bowler2013). These questions asked respondents how strongly they agreed or disagreed with five PG sentiments: (1) material wealth is a sign of God's blessing; (2) if you give away your money to God, God will bless you with more money; (3) poverty is a sign that God is unhappy with something in your life; (4) if you pray enough, God will give you what money you ask for; and (5) giving away 10% of your income is the minimum God expects. These items have a high degree of construct validity (α = 0.8747). Agreement with these five sentiments individually ranges from 11 to 23%, and nearly 20% of respondents agree with a majority of these sentiments. So while 43% of respondents believed in the general idea that God wants people to prosper, far fewer believe in the stringent cause and effect approach to faith most associated with the “hard” PG.

Results

In what follows, we test our hypotheses by asking three questions: (1) How prevalent is PG identity/belief across race and religious tradition? (2) What factors predict PG belief/identity? (3) How do these PG beliefs/identities affect political attitudes across racial categories and religious traditions? To answer this final question, we will analyze the data in four ways. First, we examine the distribution of Trump approval, Republican Party identity, and conservative ideology across religious tradition, race, and PG identity/beliefs. Second, we will see how the PG—controlling for other religious and demographic factors—affect these political outcomes for the whole sample and then among three key religious tradition subgroups: White Born Again Protestants, Black Protestants, and Hispanic Evangelicals.Footnote 3 In other words, we will ask how PG believers compare to non-PG believers within particular racial-religious traditions. This will also allow us to separate the effect of the PG from traditional measures of religious identity and beliefs. Third, we will analyze the effects of race within the subpopulation that identifies with, or believes in, the PG. In this way, we can isolate the effect of race and determine whether Black and Hispanic PG followers differ in their political attitudes from white PG believers. Finally, we will repeat these analyses on a broader set of economic and policy attitude questions to better understand the interplay between PG theology, race, and public opinion.

First, to address hypothesis 1, we need to have a better understanding of who does and does not follow the PG. As Figure 1 shows, regardless of how it is measured, whites are the least likely of the four broad racial categories to follow the PG.Footnote 4 In keeping with the results in Burge (Reference Burge2017), Blacks have statistically significantly higher PG rates than any other racial group (the one exception being compared with Asians for PG approval, where the difference is not quite significant). A third of Black respondents identify as a member of a PG church or group, 70% believe that God wants people to be financially prosperous, and almost half agree with a majority of the hard PG sentiment scale questions, compared to under 9, 36, and 12% of whites, respectively.Footnote 5 Hispanics are also significantly more likely to identify with PG churches and have PG beliefs compared to whites. Interestingly, Asians have similar levels of PG identity and belief as Hispanics, though a discussion of various Asian religious traditions and theology as it relates to the PG is beyond the scope of this paper. Figure 2 breaks down the hard PG sentiment scale from Figure 1 into each of the five underlying questions, showing much the same thing: Blacks are consistently more likely to agree with each statement than other racial categories and whites the least likely to agree.

Figure 1. Race and the PG. Bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2. Percentage agreeing with PG sentiments. Bars show 95% confidence intervals.

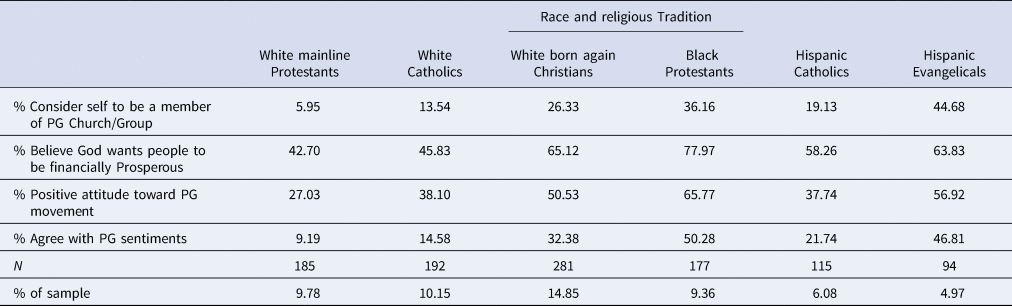

So far, hypothesis 1 receives considerable support: racial minorities—especially Blacks—are much more likely to follow the PG than whites. But does this relationship persist when incorporating religious tradition? Figures 3 and 4 divide whites into three groups: Catholic, Mainline Protestant, and Born Again, based on whether they report experiencing a “born again” conversion experience or not. Hispanics are separated according to Catholic or Evangelical identity, and Black Protestants receive their own category.Footnote 6 Once again, Black Protestants are generally the most likely to identify with and believe in the tenets of the PG than any other race/tradition, though the differences are not statistically significant from Hispanic Evangelicals. Among whites, Christians who say they are born again are far more likely to identify with the PG (26% compared to 6% of Mainliners and 13.5% of Catholics, a statistically significant difference). This difference persists when comparing PG beliefs, with white born again Christians far more likely to adopt PG sentiments than white Catholics or mainline Protestants—the latter being the least likely to adopt PG positions.

Figure 3. Race, religious tradition, and the PG. Bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4. Percentage agreeing with PG sentiments. Bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 1 shows that Hispanics were more likely than whites to follow the PG, but the aggregate racial category masks considerable difference based on religious tradition. Specifically, Evangelical Hispanics are more than twice likely to adopt PG identity and agree with hard PG sentiments than Catholic Hispanics.Footnote 7 With this caveat in mind, it remains clear that minority religious traditions are significantly more likely to follow the PG than white denominations. Furthermore, for whites the religious tradition (evangelicals) that demonstrates the highest level of PG support is the one that most commonly advocates individualistic theology and has historically had lower levels of income and education. PG adherence therefore follows our predicted patterns.

Given that we are most interested in the political effects of PG identity and beliefs (rather than general approval for the PG movement), we limit our further analysis to three PG measures: self-identity with a PG group/church, belief that God wants people to be financially prosperous (“soft” PG), and the battery of five hard PG sentiment questions. It is clear from the above figures that PG beliefs/identity are most common for three racial-religious groups: white born again Christians, Black Protestants, and Hispanic Evangelicals. As a result, our forthcoming analysis will focus on these three groups. This is not to say that the PG is irrelevant for Catholics or white mainline Protestants, but that PG ideology will be a relatively small force in those churches' and believers' political activities and beliefs.

Table 1 examines the predictors of PG identity/beliefs, including measures of religious identity, behavior/beliefs, and demographics. The religious variables that are most closely associated with the PG include belief in the second coming of Jesus Christ, speaking in tongues, and biblical literalism. Frequency of prayer also is related to increased PG identity/belief, but not for whites. Identifying as a Fundamentalist, Pentecostal, or Liberal Christian also generally increases PG identity/sentiments, though the effects are inconsistent across racial-religious groups.Footnote 8 In terms of demographic and political characteristics, income increases PG identity for born again whites and Black Protestants, showing that the PG is not just an aspirational theology for poor people. Older respondents and liberals are generally less likely to identify with the PG or express PG sentiments, and education has a mostly negative—but only occasionally significant—relationship with the PG.

Table 1. Predicting PG identity and sentiments

*p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01 (two-tailed).

The baseline religious category in models 1–3 is respondents who identify as a “none”: atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular.

The first three columns also show the effect of racial-religious identity on the PG, compared to people with no religious identity (i.e., the “nones”), controlling for the demographic and religious factors discussed above. White born again Christians are no more likely to have a PG identity or adopt the hard PG sentiments, once controlling for religious beliefs and practices. In fact, Hispanic Evangelicals are the only group significantly more likely to identify as part of a PG church once other religious beliefs/identities are controlled for. Hispanic Evangelicals and Black Protestants are the only two groups significantly more likely to express hard PG sentiments, while all religious groups are more likely than “nones” to believe that God wants people to be financially prosperous.Footnote 9 In sum, it is apparent that both identity and belief in the PG is connected with conservative religious beliefs (such as a literal reading of the Bible), especially for white born again Christians. For these believers, once accounting for religious beliefs and demographic factors, religious tradition has no predictive power for either PG identity or hard PG beliefs. Only for Black Protestants and Hispanic Evangelicals does religious affiliation seem to really matter, above and beyond individual religious beliefs.

Now that we have shown PG identity/beliefs are most pronounced among Black Protestants, Hispanic Evangelicals, and—to a lesser extent—white born again Christians, and that PG identity/beliefs are driven in large part by conservative theological attitudes, we now turn to examining the political effects of the PG. Again, hypothesis 2 predicts that the PG will push believers toward the political right and increase support for Donald Trump overall. Hypothesis 3 amends this prediction by arguing that the individualizing effects of the PG on racial minorities' partisanship and policy opinions—in particular for Black Protestants—will be constrained because of group norms and countervailing theological beliefs such as the Social Gospel.

Figure 5 shows the relationship between racial-religious tradition and Trump approval, Republican partisanship, and conservative political ideology. For the first two of these, there is a clear racial divide between whites and Blacks/Hispanics, with whites of all religious traditions being more supportive of Trump and more likely to identify as Republican. White born again Christians unsurprisingly tend to be the most consistently conservative, Republican, and Trump supporting. As we discussed earlier building on Jefferson (Reference Jefferson2020), the relationship between ideology and other political attributes—especially partisanship—is very different for Blacks than whites, as Blacks understand and contextualize the political ideology scale uniquely. Black Protestants report similar levels of conservative self-placement as white Christians (including born again whites) yet are far less likely to support Trump or identify as a Republican. Hispanic Evangelicals are also somewhat less supportive of Trump and Republican than might be expected given their ideological self-placement.

Figure 5. Race, religious tradition, and political identities/attitudes. Bars show 95% confidence intervals.

So far, this is exactly as the literature would expect. But what happens when adding in the PG? Table 2 contains models where PG identity is used to predict Trump support, Republican identity, and conservative ideology for all respondents and among the three racial-religious traditions.Footnote 10 Overall, the results provide support for much of hypothesis 2. For respondents overall, PG identity increases conservative self-placement as expected, the effect on Trump approval is positive but not significant, and PG identity is actually associated with lower Republican identification when controlling for religious and demographic variables. Breaking down these findings by racial-religious categories finds very similar rightward effects for all subgroups, as hypothesis 2 predicts. PG identity significantly increases support for Trump and conservative self-placement for white born again Christians and Black Protestants, and (marginally) increases conservatism for Hispanic Evangelicals as well, though again with no significant effect on partisanship for any of these groups.Footnote 11 But while this table shows that the PG moves people in a pro-Trump/rightward direction, it cannot demonstrate how large of an effect it has. We simulated the predicted probabilities of Trump approval and conservative identity within these groups, comparing a PG identifier with a non-identifier, keeping all other variables at their mean or modal position.

Table 2. Effect of PG identity on Trump approval, partisanship, and political ideology, by race and religious tradition

*p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01 (two-tailed).

The baseline religious category in models 1–3 is respondents who identify as a “none”: atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular.

We find that a white born again Christian is predicted to increase their strong approval of Trump by over 16 points when they go from not identifying with the PG to being a PG member. A white born again Christian is also predicted to be over 16 points more likely to identify as a conservative when going from non-PG to PG-identifying. A Black Protestant, on the other hand, is predicted to only increase their strong Trump approval by 4 points when identifying with the PG, compared to being over 18 points more likely to identify as conservative.Footnote 12 So although conservatism and Trump approval increase in tandem when white born again Christians identify with the PG, for Black Protestants there is a large disconnect between the effect of PG identity on conservatism and its effect on Trump support. While the effect of PG identity on conservatism for Blacks is just as strong, if not more so, as for white born again Christians, Blacks' increase in Trump support is only 25% as much as for white born again Christians. This again demonstrates the constraint that race provides on connecting the PG to political outcomes, and the disconnect between the traditional ideological scale and other political identities/behaviors for Black Americans.

To summarize our findings regarding hypothesis 2: while the PG increases political conservatism across the board, the pro-Trump effect is far weaker for Blacks (and non-existent for Hispanic Evangelicals). On the other hand, the PG leads to no demonstrable change in partisan identity for any individual group and seems to actually decrease Republican ID overall. While the lack of positive effects for Republican partisanship goes against our predictions, it is likely the case that partisanship is entrenched in the identities of most respondents, and once controlling for demographics, religious affiliation and beliefs, there is little explanatory power left for the PG. Indeed, as Margolis (Reference Margolis2018) shows, partisanship may be so powerful that it may influence religious choices, rather than the other way around. In other words, white conservative Christians are simply going to be Republicans, and the PG can do little to change this, just as Black Protestants are so overwhelmingly Democratic that the PG can make no meaningful partisan effects.

While Table 2 shows the effect of the PG on respondents within racial-religious subgroups, Table 3 examines the effect of race within PG identifiers/believers. That is, if the PG makes people (especially white born again Christians) more conservative and supportive of Trump, how does race affect those who identify as members of the PG or who have PG beliefs? If hypothesis 3 is correct, we will see significant racial differences among PG identifiers/believers, as race will constrain the rightward shift brought about by the PG.

Table 3. Effect of race within PG categories on political outcomes

*p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01 (two-tailed).

Table 3 shows the effect of race on Trump approval, Republican identity, and Conservative self-placement for those categorized as part of the PG using each of our three PG measures, controlling for religious and demographic variables. Each racial variable coefficient is interpreted as a comparison to a baseline of white identifiers.Footnote 13 Black respondents are less supportive of Trump than whites within two of the three PG groups; only for PG identifiers the negative coefficient is not significant. But as expected given the work of Jefferson (Reference Jefferson2020) and White and Laird (Reference White and Laird2020), Blacks are significantly less likely to identify as Republicans than whites across all three measures of the PG, while simultaneously being no less conservative than whites in any of the three models.

Figure 6 visualizes the effects of PG beliefs by reporting the first differences associated with predicted probabilities derived from the PG sentiment models in Table 3. This figure shows the effect of changing race while keeping all other variables at their mean/modal value. Compared to whites, holding all other variables constant, being Black is associated with a 22 percentage point decline in Trump approval on average and a 29 point drop in the likelihood of identifying as a Republican, but no difference on conservative ideology. Compared to being white, being Hispanic has an average decline of 34 and 28 percentage points on Trump approval and Republican identity, respectively. We also examined reported vote choice (not shown here), and for those expressing hard PG sentiments, Blacks are 24 points less likely to say they voted for Trump compared to whites, and Hispanics are 20 points less likely to have voted for Trump.

Figure 6. Effect of race on political outcomes among PG believers. Bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Earlier, we posed the question “Will a Black Protestant who follows the PG behave politically more like a white PG follower, or like a Black Protestant who does not adhere to the PG?” So far, the answer is that racial minorities who follow the PG will be politically somewhere in between non-PG adherents of their racial-religious community and fellow PG adherents who are white. As hypotheses 2 and 3 predict, the PG strongly increases minorities' conservative self-placement and marginally increases Trump support for Black Protestants, while at the same time being Black or Hispanic serves to severely reduce any pro-Trump/Republican effect among PG adherents without touching political ideology. Clearly the constraint of race on politics within the PG is significant both statistically and substantively.

Thus far, we have strongly supported hypothesis 3 by showing that while the PG does generally push people to the right and in support of Trump, there are profound racial differences in this process, with white PG adherents being far more likely to identify as Republican and approve of Trump than nonwhite PG adherents. As a final analysis, we will examine how the PG and race combine to influence a variety of attitudes toward debt and economic policies. Since PG theology is primarily concerned with economic success and instructs followers to demonstrate their faith with financial contributions to receive financial blessings, we expect that if the PG affects peoples' policy attitudes it will be primarily in the area of economics, debt, and social welfare. However, the relationship between the PG and economic attitudes is likely complex. For instance, if your theology tells you to give away your money to receive future rewards, might that increase your willingness to support budget deficits to support public investments or high government spending that promises to protect peoples' welfare? Or does the individualistic nature of the PG make people more likely to focus on their own individual well-being and financial position at the expense of policies designed to help the broader public? If the PG increases support for Trump's “populist” agenda, what kind of populism does that mean?

Tables 4 and 5 seek to answer these questions by repeating the analysis of Tables 2 and 3 with 11 questions tapping into attitudes on debt, spending, and social welfare. Full question wordings are found in the Appendix. Table 4 examines the effect of our three measures of PG adherence on these eleven questions, first for all respondents and then broken down for our three racial-religious subgroups. First, we examine attitudes toward money debt at a personal level. PG identity and hard PG sentiments generally increase agreement that “debt is a path to the American Dream” for all groups. Similarly, PG identity/sentiments increase agreement that debt has “expanded your opportunities” rather than being a burden, especially for Black Protestants. While there is minimal evidence for individualistic sentiments on Americans relying too much on government to give them free things because individuals spent too much (almost all coefficients are insignificant), we see that the PG decreases respondents' beliefs that Americans place too much importance on wealth and money—especially for white born again Christians in the PG belief categories and Black Protestants in the PG identity category. Overall, it appears that the PG increases Americans' acceptance of personal debt and spending as a pathway to opportunity and success, especially for Black Protestants and white born again Christians.Footnote 14

Table 4. Effect of the PG on economic attitudes, by religious tradition

*p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01 (two-tailed).

Note: Each PG measure comes from a separate model.

Table 5. Effect of race on economic attitudes among PG identifiers/believers

*p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01 (two-tailed).

Note: Each coefficient is compared to the White category.

Second, we show that there is limited evidence that the PG dramatically affects attitudes toward government debt. On the one hand, Black PG identifiers are significantly less likely to say it is important that the government prioritizes “living within its means” when making budgetary decisions, while white born again Christians and Hispanic Evangelicals in the PG belief categories believe living within the government's means is more important than those who do not believe in the PG. White born again PG believers are also more likely to say that the government's budget deficit affects their own finances, while no other group agrees. Finally, there is some evidence that the PG affects whether people think the national debt should be prioritized, though in inconsistent directions.

Finally, we examine the effect of the PG on three economic policy areas. Hard PG sentiments increase white born again support for increasing the minimum wage, but not for the other racial groups. The PG generally decreases support for making sure that wealth is more evenly distributed, but outside of Hispanic PG identifiers, this does not differ by race/religion. Finally, the PG generally increases support for allowing Americans to invest a portion of their Social Security taxes into a private account. Again, the PG mostly moves Americans in a more individualistic direction on economic and social welfare issues, while also being more accepting of debt and spending at a personal level. While the results from within racial-religious categories are not consistently significant, the PG does often influence how Christians view these issues.

As a final analysis, Table 5 repeats the previous analysis within PG categories to examine whether (and how) race divides PG adherents. Focusing on the comparison of Blacks with whites, we find that Black respondents with hard PG sentiments are less likely than whites to say that debt serves as a path to the American dream, but also less likely to say Americans place too much importance on money and wealth. Blacks are more likely to say that the budget deficit affects their finances and prioritize the national debt, while somewhat less likely to say that the government should live within its means. While these questions provide a fairly mixed assessment of the role of race on political attitudes, the final three policy questions are clearer. Blacks within the PG are significantly more likely than whites to approve of raising the minimum wage and say that they want wealth to be more evenly distributed, and less likely to approve of allowing individuals to invest their Social Security payroll taxes into private accounts.

Hispanics also significantly differ from whites on many of these measures. Specifically, they are less likely to say that Americans are spending too much or place too much importance on money, more likely to believe the budget deficit affects their finances and want to raise the minimum wage, and less likely to say government should live within its means, budget like a household, or make sure wealth is more evenly distributed. Again, the effects are somewhat of a mixed bag in terms of policy preferences and personal attitudes toward debt, showing some ambivalence when turning PG theology into political opinions.

Discussion

Putting all these results together, our analysis shows that: (1) when understanding who affiliates with the PG and adopts PG beliefs, race matters. Blacks (namely Black Protestants) are the racial group most likely to adhere to the PG, with Hispanic Evangelicals and white born again Christians following them. White mainline Protestants, white Catholics, and Hispanic Catholics are no more likely than the average respondent to follow the PG. (2) Conservative religious beliefs, practices, and identities increase the likelihood of identifying with and believing in the PG, with the only religious traditions further predicting PG beliefs/identity being racial minorities. (3) PG identity pushes all groups in a conservative ideological direction and increases support for Trump among white born again Christians and Black Protestants. It has no significant effect on partisanship. (4) The pro-Trump effects of the PG within racial categories are much weaker for non-whites than for whites, and among PG identifiers/believers, being Black (and to a lesser extent, Hispanic) makes people much less supportive of Trump and less likely to identify as Republican compared to whites. Again, race matters. (5) Identifying with and believing in the PG generally increases positive attitudes toward debt and spending on a personal level, and generally (though inconsistently) increases preferences for fiscal responsibility by the federal government. In terms of policies, the PG tends to increase support for increasing the minimum wage and investing Social Security taxes into private accounts, while decreasing support for wealth redistribution. In other words, the PG increases individualistic economic policy stances, though the significance of this relationship is again inconsistent across groups and measures. (6) Within PG categories, Black Protestants are significantly more likely than whites to support liberal social welfare policies, including raising the minimum wage, increasing wealth redistribution, and opposing privatizing Social Security. The Social Gospel may not be wholly inconstent with PG beliefs for Black Protestants.

While the results are not perfectly in line with the predictions of our three hypotheses, overall the data clearly support our arguments about the complexity of the relationship between race, the PG, and politics. Theological beliefs matter, but so does race and religious tradition. For whites—especially white evangelicals—the PG tends to work in concert with other religious beliefs and habits in pushing adherents to the right on political matters and in supporting Trump. For nonwhites, the tension between PG beliefs and contrary racial/theological norms are apparent in how their faith gets translated into politics. In particular, Black Protestants who follow the PG are caught in the middle: somewhat more supportive of Trump and more conservative than their non-PG Black Protestant peers, but far less supportive of Trump and less Republican than their white PG peers. While there is certainly a good degree of overlap in religious beliefs/attitudes between Black, Hispanic, and white evangelical Christians, the multitude of differences in historical development, theology, social context, and religious behavior clearly matter for applying those religious beliefs to politics. These contradictions are worthy of further exploration.

There is much speculation as to why Black Protestants support the PG in greater numbers than Whites. Perhaps, as the reviewed literature details, the recent popularity of the PG is connected with rising Black economic fortunes, making the PG especially timely for and resonant with Blacks looking for a new theological compass to guide their shifting economic realities within a persistently unequal society. More analysis of Blacks' economic perceptions and financial habits might shed light on the appeal of the PG. Also, recalling Koch's argument, perhaps Blacks are primed to frame theology as a vehicle for in-group or individual economic mobility instead of more traditional routes to wealth and power enjoyed by whites in the past and current socio-political structure. Does affinity for the PG represent current economic and social realities or reflect longstanding cultural and theological traditions? Digging into what messages (and messengers) Black Christians hear and follow will help us understand how religion is connected to economic and political issues. Do Blacks who attend multi-ethnic PG churches differ from those who inhabit Black-dominated spaces? When national figures such as Joel Osteen or Dave Ramsey talk about debt and faith, does that affect racial groups differently?

This paper also invites further exploration of the complex effects that the PG has on Black political life—particularly a pointed effort to understand how Black PG supporters simultaneously exhibit conservative ideological positions and greater Trump approval while also being no more likely report voting for Trump or identifying as a Republican. Does a Trumpian populism represent an opportunity for Republicans to make inroads in minority communities, especially those that exhibit conservative religious views and PG sentiments? If Trump is the first PG president, and nonwhite Christians are the most strongly PG, there would seem to be a great opportunity for Republicans to expand their political coalition beyond their conservative white base. Perhaps, the PG can provide a bridge between white born again Christians who represent the foundation of Trump's (and other Republicans') political base and nonwhite believers who have tended to distrust Republican politicians and policies.

A further investigation would perhaps observe how the increasingly dynamic influence of the PG on Black politics operates in relation to the Social Gospel. That is, great insight can emerge about Black political identification and behaviors if the Social Gospel and PG are found not to be inherently contradictory. How do these two theological guides work together to shape the multi-layered connections between party ID, political ideology, and voting patterns for Black Protestants? To what degree do the racial differences in political behavior reflect theological differences as opposed to the effects of racism, political sorting, polarization, and entrenched partisanship? And how will these relationships change in a post-Trump era?

There still remains much work in disentangling the effect of the PG as a belief system and religious identity/network on a wide variety of political behaviors and beliefs. But this paper has provided data on the distribution of such identities and beliefs across racial categories and religious traditions, helped to understand the underlying factors that push people toward the PG, and tracked how the PG differentiates individuals' beliefs within race and between races and traditions in the Trump era.

Ben Gaskins is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, OR. His research examines the role of religion on economic attitudes and behaviors, vote choice, and democratic citizenship.

JahAsia Jacobs is a graduate student in the Department of Anthropology at Princeton University. Her research focuses on how religion and emotion mediate economic experiences for Black Americans.

Appendix

Table A1. Relationship between race and the PG

Table A2. Relationship between RACE and PG beliefs

Table A3. Relationship between race, religious tradition, and the PG

Table A4. Relationship between race, religious tradition, and PG beliefs

Table A5. Effect of PG beliefs on Trump approval, partisanship, and political ideology, by race and religious tradition

Table A6. How race, religious tradition, and the PG affect politics

Table A7. Race, religious tradition, the PG and economic attitudes (% agree)

Question wording for Tables 4–5

1. Which of the following statements about personal debt do you agree with more?

1. Personal debt provides a path to achieving the American Dream by making it possible for people to borrow against their future earnings to pay for college, start a business, finance a car, and buy a home.

2. Personal debt creates an obstacle to achieving the American Dream by encouraging people to spend beyond their means, burdening them with high levels of debt and many years of interest payments.

2. In your own life, do you think that personal debt has expanded your opportunities by allowing you to make purchases you couldn't afford from your income at the time, or reduced your opportunities by burdening you with bills that you couldn't really afford to pay?

1. Expanded opportunities

2. Burdened with bills

3. Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: America has succeeded because of hard work and competition, not because we expect government to give us things for free. For too long, Americans have spent money they couldn't afford, driving up personal and government debt.

1. Strongly agree

2. Somewhat agree

3. Somewhat disagree

4. Strongly disagree

4. Do you think Americans place too much importance on money and personal wealth, too little importance on money and personal wealth, or about the right amount?

1. Too much

2. Too little

3. Right amount

5. How much do you believe the federal government's budget deficit and debt impacts your personal financial situation?

1. A great deal

2. Only some

3. Not too much

4. Not at all

6. As you may know, every year Congress holds a debate about the federal budget for the coming year, which will involve decisions over national priorities. How important do you think the value or principle of “living within our means” should be as a guide for these decisions?

1. Most important

2. Very important

3. Somewhat important

4. Not too important

5. Not at all important

7. Which of the following statements do you agree with more?

1. The federal government should manage its budget like American families run their household budgets. Households take on debt to pay for a house or a college education or pay everyday expenses, but there are limits on how much households can borrow and they are obligated to pay back the loans they take out. The government, like households, should invest and save for future needs and emergencies and at the same time live within its means by not spending more than it takes in while limiting and paying off its debt.

2. The federal government should not be expected to manage its budget like American families run their household budgets. The government has the unique ability, resources and responsibility to stimulate economic activity to lessen the effects of a recession and to invest in things like education and research that can help the country in the future. Given these responsibilities and the government's ability to borrow money at lower rates and on a much longer timeline, there are times when government has to spend more than it takes in.

8. Some people say that addressing the national debt should be among the President and Congress's top 3 priorities. Do you agree or disagree?

1. Strongly agree

2. Somewhat agree

3. Somewhat disagree

4. Strongly disagree

9. As you may know, the federal minimum wage is currently $7.25 an hour. Which position best reflects your view about the minimum wage? Should it be eliminated, kept where it is, raised to $12.00, raised to $15.00, or raised to $20.00?

1. Eliminated

2. Kept where it is

3. Raised to $12

4. Raised to $15

5. Raised to $20

10. Do you feel that the distribution of money and wealth in this country is fair, or do you feel that the money and wealth in this country should be more evenly distributed among more people?

1. The distribution is fair

2. Wealth should be more evenly distributed

3. Unsure

11. Imagine a proposal has been made that would allow people to put a portion of their Social Security payroll taxes into personal retirement accounts that would be invested in stocks and bonds. Would you favor or oppose this proposal?

1. Strongly favor

2. Somewhat favor

3. Neither favor nor oppose

4. Somewhat oppose

5. Strongly oppose