INTRODUCTION

Whetstones are small and unprepossessing but necessary implements, likely to be found in all Romano-British homes, farmsteads, villas, workshops and garrisons, wherever iron edge-tools, implements and weapons required maintenance or finishing. In the published archaeological record, however, their presence is distinctly limited, having been overlooked or given limited and generally unsystematic attention on the ground and subsequently in the laboratory. Attitudes and practice towards those of Roman date are nevertheless slowly changing, especially on the near-Continent, where geological methods have been more wholeheartedly and systematically applied.Footnote 1 It is becoming appreciated, in Britain and overseas, that many kinds of whetstone are the products of major stone-based extractive industries, with a considerable geographical reach through trade and other means of dispersal.Footnote 2 Their geological provenance and methods of manufacture are becoming increasingly clear. Whetstones are proving to have been valued if not also valuable objects, and some had a role in Roman ritual.Footnote 3

The aim of this paper is to raise the profile of Romano-British whetstones as objects of archaeological significance worthy of detailed study, by means of a review of their distribution, character and geological provenance, using published descriptions and illustrations in printed excavation and related reports numbering upwards of 200. As they stand, however, these records are far from uniform in quality and value, ranging from one-word, open-ended, unqualified and almost useless descriptions, such as ‘sandstone’, to, much more rarely, detailed, technical accounts founded on thin-section petrography or geochemical analysis. Consequently, the outcome of the survey necessarily includes much that remains uncertain and subject to review, while also revealing previously unknown geographical patterns that should prompt further research and lead on to a more balanced and systematic understanding of these widely spread finds.

PRELIMINARY MATTERS

Many kinds of rock have been exploited for whetstones. Whichever is selected, it is generally agreed that what makes a good whetstone is a rock composed of a mixture of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ particles or elements.Footnote 4 The hard particles could be angular, uniformly sized grains of quartz (7 on Mohs’ hardness scale), as in a sandstone, or well-shaped, angular phenocrysts of quartz, feldspar (Mohs’ 6) or pyroxene (Mohs’ 5–6), as in a lava or tuff. All of these can act as the tiny chisels needed to remove slivers of metal from an object being sharpened or finished. Although not strictly particles, a similar role is played by the edges of empty gas bubbles dispersed in glassy or finely crystalline lavas when used for whetstones. The soft element in whetstones is played by voids and by mineral cements, such as gypsum (Mohs’ 1.5–2), clay (Mohs’ 2–4), calcite (Mohs’ 3), dolomite (Mohs’ 3.5–4), or by a clayey matrix formed of soft rock fragments squeezed tightly together during burial of the rock (Mohs’ 2–4). The weakness of these materials allows the sharp edges of the hard grains in whetstones to be continually undercut and kept exposed during use.

The quality of the edges produced by whetstones is determined not only by the composition of the mixture of hard and soft elements, but also by the general size and size-spread of the hard particles. Keen edges, and also fine polishes, can be produced only by using fine-grained whetstones, such as those of siltstone, cementstone, or slate. Coarse particles abrade metals quickly but afford only ragged edges to blades.

As there is at present no generally agreed typology for whetstones, it is convenient to use the scheme applied to the assemblage found in Iron Age and Roman Silchester (Calleva Atrebatum), the largest and most varied from any published British site.Footnote 5 Bar-shaped whetstones (or simply bars) are up to a Roman foot or so in length, square to rectangular in section when unworn, of the order of 20 mm in thickness and up to about twice as wide as thick. They are manufactured items, made in one mode of production by grooving with a saw the opposite faces of a prepared slab of stone and then snapping off the individual whetstones like pieces of chocolate.Footnote 6 Proof of this origin is the presence of rebates of rectangular section along each long edge of the whetstone, as seen on the 100 or so bars found in the forum gutter at Wroxeter (Viroconium),Footnote 7 an exceptionally rare and extraordinary ‘pre-use’ assemblage.Footnote 8 In an alternative mode of production, known from two British military sites,Footnote 9 and widely used on the near-Continent,Footnote 10 the grooving is done using a mason's chisel or point driven by a mallet. In this case the grooves in appearance are ragged and irregular, as well as V-shaped in profile, leading to uneven bevels along the edges of the detached whetstones. In use, bar-shaped whetstones are intended to be held in the hand, and either kept stationary, as when a knife-blade is drawn along them, or swept to and fro on larger items such as a sword or scythe.

Bar-shaped whetstones as a class may be either primary or secondary: they are primary when directly made from quarried rock, but secondary when prepared from such as a roofing tile or milling stone. Other primary whetstones are ‘found’, or natural, objects, such as suitable pieces of rock detached from natural outcrops, pebbles collected from stream beds or beaches, or fragments of suitable stone (‘brash’, ‘float’) picked up from cultivated fields or construction sites.

Secondary whetstones are objects with a demonstrable biography,Footnote 11 which began life in some other form, such as a stone rooftile, or a piece of broken quern or millstone. These repurposed items are commonly tablet-shaped, that is, thin, platy and irregularly tabular in form, but they are also found as bars. That many derive from stone rooftiles is shown by their thickness, typically in the range 15–20 mm, and the survival on the larger examples of punched holes for fixing nails.Footnote 12 They can vary in size and portability from just a few centimetres across, suitable for use in the hand as in a toolkit, to examples which are almost complete tiles and clearly intended to be laid flat and kept stationary in use. Secondary whetstones derived from millstones or querns are typically more robust and commonly irregular in shape and, as evidence of their origin, may display curved faces on which traces of pecking or rasping have survived.

WHETSTONE FORMS

BARS

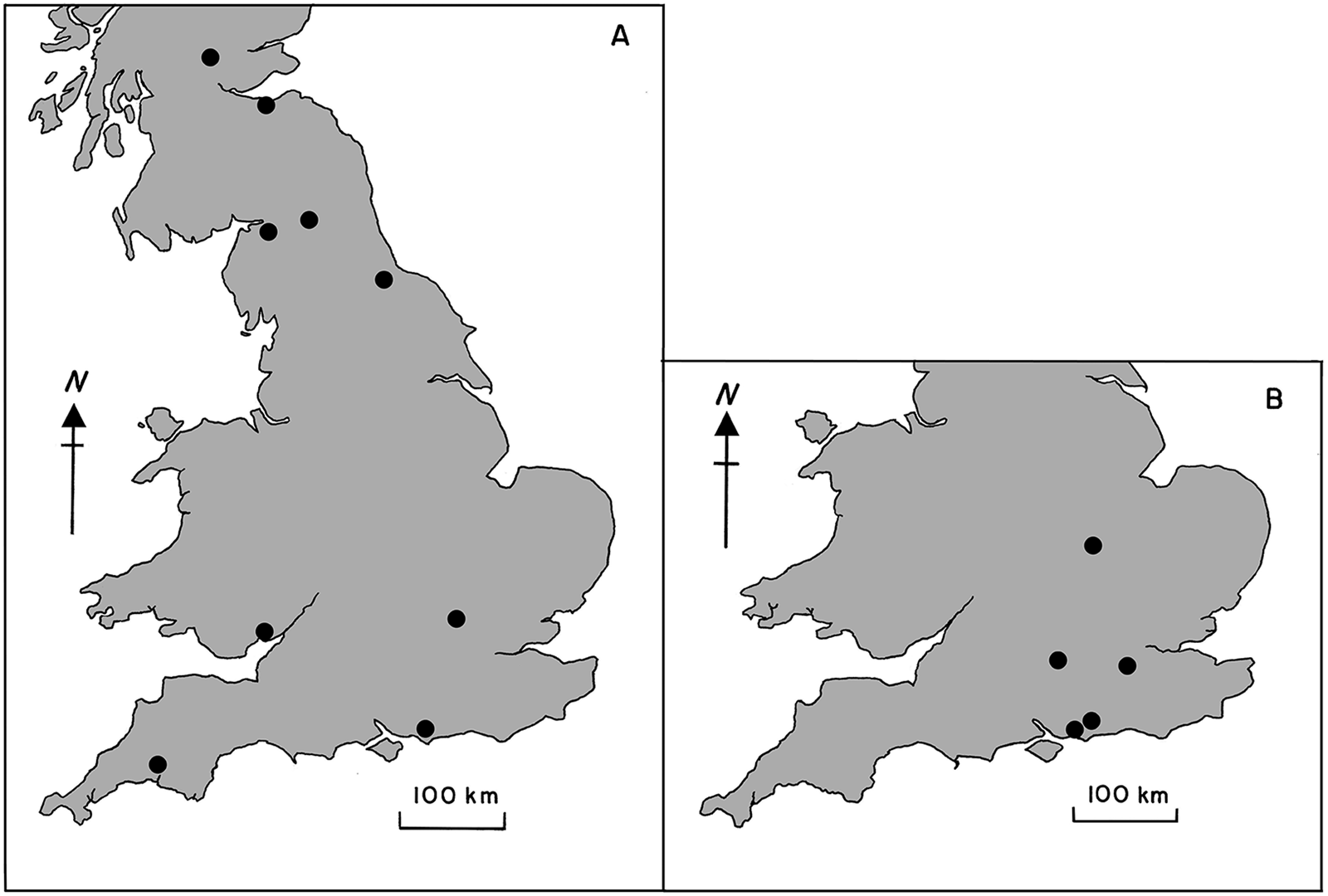

Most of the whetstones recorded in the database are best classed as bar-shaped, as defined above, occurring at 99 findspots. They occur throughout Roman Britain (fig. 1A), but are most plentiful at southern sites, forming an east–west belt that ranges from the Thames Estuary area through the south Midlands to the shores of the Severn Estuary and Bristol Channel. Their findspots otherwise straggle northward, but at a lower density, mainly through eastern England and south-east Scotland as far as the southern Scottish Highlands. Most bar whetstones are likely to have been made as described above, but convincing direct evidence for this is at present sparse.

FIG. 1. Distribution of whetstone forms in Roman Britain: (A) bars; (B) tablets.

TABLETS

Localities yielding tablet-shaped whetstones (n=52) are only about half as common, and have a different distribution (fig. 1B). They are clustered in the same east–west belt as the bar-shaped forms, but are seldom found elsewhere. It is no coincidence that this concentration is also the area – aptly named the ‘stone-tile belt’ – which chiefly saw the use of quarried roofing materials such as the Swithland slate (Precambrian), Brownstones (Devonian Old Red Sandstone), Pennant sandstone (Upper Carboniferous), Stonesfield slate (Middle Jurassic), Collyweston slate (Middle Jurassic) and Purbeck limestone (Upper Jurassic),Footnote 13 as well as the perhaps more familiar ceramic tiles (CBM).

FOUND OBJECTS

The database shows these lithologically varied, primary whetstones to be present at 21 localities. There is no particular pattern to their distribution, but most of the sites are in southern Britain.

WHETSTONES OF IGNEOUS/METAMORPHIC ROCKS

Rocks of igneous or metamorphic origin occur widely in Britain, mainly in the geologically older and more altitudinous west, but particularly in the Scottish Highlands. Never much used for whetstones, they have been recorded from seven military sites, six settlements, five towns and two villas.

GRANITE

There are only two recorded occurrences of possibly granite whetstones (fig. 2A), from the Flavian fort at Elginhaugh on the southern shores of the Firth of Forth.Footnote 14 The location is consistent with such a provenance, but the description of one whetstone as of ‘very fine grain’ points to a different type of rock. The name granite can be misleading, as the name is widely used, even in the trade, for any kind of hard rock, including many not of igneous origin.

FIG. 2. Distribution of recorded whetstone lithologies in Roman Britain: (A) granite, lava and tuff; (B) basalt/dolerite; (C) mica-schist; (D) slate.

BASALTS-DOLERITES

Basalts-dolerites constitute a family of very finely to coarsely crystalline basic igneous rocks of intrusive to extrusive origin, to be found in several parts of Britain.Footnote 15 Whetstones attributed to this family, in some cases under a local name, are recorded from eight sites (fig. 2B). The distribution is in two parts.

There is a northern cluster (n=4), dominated by military sites associated with Hadrian's Wall, with whetstones described as ‘whinstones’, and a doubtful whetstone of tholeitic basalt (by thin-section) from the settlement to the south at Shiptonthorpe on the eastern main road north.Footnote 16 The well-known Carboniferous intrusion of the Whin Sill, on the crags of which Hadrian's Wall partly stands, was clearly an important and readily accessible local source of suitable material.

The other cluster of sites (n=4) lies far to the south in the West Country and South Midlands (fig. 2B). The source of the whetstone from the most westerly locality, Marshfield north of Bath, is assigned to intrusive basaltic dykes that crop out near Bristol.Footnote 17 At the other localities the whetstones are variously described as dolerite or basalt (?including a Leicestershire source).

LAVA

Lavas are extrusive igneous rocks, of acid to basic composition, but typically very fine to fine-grained in terms of matrix, or even glassy, with dispersed larger vesicles and phenocrysts. A whetstone of this sort is recorded in the database at only one site (fig. 2A), and is suggested to be of a German lava. It is possibly a discarded fragment of an imported Mayen quern.

TUFF

Tuffs are indurated volcanic ashes, deposited on land or on the sea, varying from very fine-grained to coarsely fragmental, with abundant crystals and rock fragments. They are widely known from the geologically older parts of western Britain, up to and including southern Scotland. The single whetstone of this kind is described as ‘fine-grained’,Footnote 18 but the findspot, Stowmarket in East Anglia, is a long way from any plausible primary source and the object may be of the found kind, perhaps brought south as a glacial erratic (fig. 2A).

MICA SCHIST

Metamorphic rocks, such as mica schist, arise chiefly when mudrocks and muddy sandstones buried deep in the Earth's crust are subjected to substantial heat and stress. They acquire new fabrics and mineral compositions, but without significant overall chemical change.

Mica schist is a high-grade metamorphic rock making whetstones at three, highly dispersed localities (fig. 2C). The Scottish Highlands are almost certainly the ultimate primary source, but the finds in eastern and southern England suggest that these could be found objects introduced glacially from the north.

SLATES/PHYLLITES

Slates/phyllites are formed from shales and mudrocks that have recrystallised under conditions of low-grade metamorphism, so as to acquire a more or less pronounced slaty cleavage due to the parallel orientation of the contained micas. They abound in the Lower Palaeozoic sequences of Wales, Cumbria and the Southern Uplands of Scotland, in the Upper Palaeozoic rocks of Devon and Cornwall, and to a small extent in the Precambrian rocks of the East Midlands.

Typically fine-grained, whetstones of slate/phyllite are recorded from nine sites dispersed chiefly in the West Midlands and southern Britain (fig. 2D). None of the findspots lie near putative sources; an item from County Hall in Dorchester (Durnovaria) has been attributed to a source in Devon/Cornwall.Footnote 19 A small whetstone at Silchester (Calleva Atrebatum) was considered to resemble a coarse slate from the Silurian of south-west Cumbria.Footnote 20 Does the clustering of findspots near the Channel coast point to importation from potential sources on the near-Continent, or by sea from (south-west) Wales or south-west England (see Dorchester above)?

BROWNSTONES AND PENNANT SANDSTONE

The Brownstones and Pennant sandstone are two Upper Palaeozoic sandstone formations of particular importance as sources of whetstone material in Roman Britain. Although most of the tools appear to be secondary, based on roofing tiles, a probably small, early Roman, military manufactory making primary whetstones from the local Brownstones is known to have been established at Usk (Burrium) in south-east Wales.Footnote 21 The possibility that there were others, the Pennant sandstone included, cannot be excluded (see below).

BROWNSTONES

The Brownstones is an upward-coarsening sequence of very fine- to coarse-grained and pebbly sandstones of Lower Devonian (Lower Old Red Sandstone) age that crops out in the Forest of Dean, south-east Wales and the Bristol area.Footnote 22 The beds most suited to the direct manufacture of whetstones and to making roof tiles are the flaggy, micaceous, finer-grained sandstones in the lower part of the sequence. There are no known Roman quarries, but the outcrops on the east side of the Forest of Dean, in the Wye Valley and, especially, on the coast of the Severn Estuary at Portishead, near the mouth of the River Avon, are all favourable sites. For example, the gently shelving shore at the latter place would have allowed vessels to be beached at high tide for later loading within site of the outcrop.

Whetstones attributable to the Brownstones are recorded in the database at 24 findspots (fig. 3A). They lie squarely in the stone-tile belt alluded to above (fig. 2B), in a geographical distribution closely similar to that of Brownstones roofing tiles.Footnote 23 The findspots show a distinct fall-off in spatial density eastward into East Anglia, a pointer to the westerly provenance of the tools. Most of the whetstones are tablets, but there is a substantial proportion of bars. Their occurrence is from the first century onward, but mostly in the later Roman period, as at Silchester.Footnote 24

FIG. 3. Distribution of recorded whetstone lithologies in Roman Britain: (A) Brownstones; (B) Pennant sandstone.

FIG. 4. Distribution of recorded whetstone lithologies in Roman Britain: (A) micaceous sandstone; (B) grey sandstone; (C) Millstone Grit; (D) Coal Measures.

PENNANT SANDSTONE

Pennant sandstone is a generic term for thick series of relatively coarse-grained sandstones with thin shales and coals of late Carboniferous age that outcrop in the South Wales Coalfield,Footnote 25 the central Forest of DeanFootnote 26 and the structurally complex basins of the Bristol-Somerset Coalfield.Footnote 27 The rocks are closely similar in outcrop to the Brownstones and, given the co-distribution (see below) of Pennant with Brownstones products in terms of location and date, may have contributed to the basis of a single, large Roman quarrying industry in the West Country. Where the Roman quarries lay is unknown. A very convenient site, however, would have been the banks of the River Avon in what is now part of the city of Bristol, from which, in the nineteenth and earlier twentieth centuries, Pennant sandstone preferred for building was extracted.Footnote 28 A perhaps less accessible location is the valley of the River Frome, entering the Avon from north-east of the city.

In contrast to the Brownstones, Pennant sandstones seen as whetstones are greenish grey to dark grey in colour and medium to coarse grained. The strata are well bedded and flaggy, with abundantly micaceous partings. Distinctive under the microscope, the rocks are seen to be lithic sandstones, composed about equally of quartz, with a little feldspar, and many rock fragments, chiefly shales, mudrocks and phyllites with scattered microschists, metaquartzites and acid lavas. Coalified plant fragments and grains of clay ironstone and siderite are not uncommon. A distinctive feature of the sandstones is that the softer rock fragments during post-depositional burial were tightly squeezed between the harder quartzes and feldspars to produce an overall ‘condensed’ fabric and soft matrix lacking cement-filled voids.

In harmony with the proximity of the outcrops themselves, and the findspots of roofing tiles,Footnote 29 the spatial distribution of Pennant whetstones (n=24) is virtually identical within the stone-tile belt (fig. 3B) to that of Brownstones implements (fig. 3A), the two lithologies being found together at many sites. Like the Brownstones, the whetstones are recorded as far eastward as London and East Anglia, but are not known to range further to the north than Wroxeter. Most are tablets, but many bars are recorded. As work at Silchester has shown,Footnote 30 Pennant sandstone whetstones are most prevalent in the later Roman period, in harmony with their Brownstones equivalents.

SOME OTHER SANDSTONES

The database has abundant references to whetstones of ‘sandstone’, in many cases in association with a simple qualifier, such as ‘micaceous’, ‘grey’, ‘red’, or ‘ferruginous’. There is also a scattering of whetstones diagnosed as ‘Millstone Grit’ or ‘Coal Measures’. These are all reviewed below. A total of 51 whetstones is involved.

MICACEOUS SANDSTONES

Tablet and bar sandstone whetstones are described as ‘micaceous’ at 20 sites. Their distribution is in two parts (fig. 4A), with most findspots in the stone-tile belt, between the Severn and Thames Estuary regions, but four at a distance in northern England.

Micaceousness is a property of both the Brownstones and Pennant sandstone flaggy source rocks. Given this, and the distribution recorded in fig. 4A, it seems possible that the signifier micaceous is an alias for Brownstones/Pennant rocks (see fig. 3) in the case of the main findspot cluster.

The northern cluster is dominated by military sites linked to Hadrian's Wall. The micaceous whetstones here could have been brought from the south, but local Carboniferous sandstones in the north Pennines, or even the Midland Valley of Scotland, also micaceous, may instead have been exploited. The outlying site in this cluster, at Shiptonthorpe,Footnote 31 yielding two whetstones, lies on a main road north from the landing place of Petuaria (Brough) on the Humber Estuary.

GREY SANDSTONES/SILTSTONES

Bar and tablet whetstones described as formed of grey sandstone/siltstone are recorded at a total of 18 sites, with a distribution in two parts (fig. 4B). Like the micaceous whetstones (fig. 4A), the findspots of most of these tools lie firmly in the stone-tile belt between the Severn and Thames Estuary regions. Three are dispersed at a distance, in the north-west Midlands (Nantwich), eastern England (Shiptonthorpe, also micaceous whetstones) and Cumbria (Carlisle, also micaceous whetstones).

Arguing as before, it is plausible this this signifier is at least a partial alias for Pennant sandstone, given that greyness is a property of these beds, and the findspots lie mainly in the stone-tile belt, along with whetstones identified as Pennant (fig. 3B). Other grey sandstones could have been exploited at the three outlying sites.

MILLSTONE GRIT

The Millstone Grit is a thick formation of shales and sandstones of early Upper Carboniferous age with extensive outcrops in the Pennine region of northern England. The sandstones are distinguished by being feldspathic and coarse to very coarse grained, with a partial siliceous cement.

Whetstones attributed to the Millstone Grit are reported at nine dispersed sites (fig. 4C), most of which are remote from the main outcrop. This need not mean that some other source rock should be sought, for millstones of Millstone Grit are widely present in the Midlands of Roman Britain as far south as the Thames valley.Footnote 32

COAL MEASURES

The Coal Measures are thick series of shales, sandstones and substantial coals that define the exposed coalfields widespread throughout Britain. They are younger than the Millstone Grit and date to the late Upper Carboniferous. Whetstones referred to as the Coal Measures are recorded from 18 highly dispersed sites, though tending to be concentrated in the south at the western end of the stone-tile belt (fig. 4D). As described in excavation reports, the group lacks consistency, the rocks ranging in colour from grey or buff to grey-brown or purple-brown, with some being micaceous. The buff varieties may well be true Coal Measures, as represented by generic York stone from the south Pennine region,Footnote 33 but the clustering in the stone-tile belt perhaps suggests other aliases (Technically, the formations yielding Pennant sandstone are part of the Coal Measures in a broad sense). Sandstone whetstones from Strageath in central Scotland are attributed to the Coal Measures of the Midland Valley.Footnote 34

RED SANDSTONES

Whetstones described as red sandstone are reported from nine findspots arranged in two widely separated groups (fig. 5A). Of the northern cluster of five locations, with the exception of the Ingleby Barwick villa, four are military in character. The southern group is more dispersed, only two findspots having military links. Red sandstone whetstones are conspicuously absent from middle England.

FIG. 5. Distribution of recorded whetstones lithologies in Roman Britain: (A) red sandstone; (B) ferruginous sandstone.

The sources of these whetstones appear to lie mainly in the very considerable outcrop of the Permo-Triassic – broadly, New Red Sandstone – rocks that can be traced from south-west England through the English Midland and the Pennine flanks to the Scottish Borders. Sandstone units occur at many levels within this thick sequence, but many are comparatively soft and friable, and only those with a calcareous, dolomitic, or siliceous cement are hard enough to be of much use for whetstones. The Penrith Sandstone (Permian) from the Vale of Eden and the St Bees Sandstone (Triassic) of the Cumbrian coast are mentioned as possible sources of the pink sandstone whetstones found at Carlisle,Footnote 35 and the same source(s) may have been exploited for the pink whetstones from Housesteads.Footnote 36 The Triassic Sherwood Sandstone is suggested as the source of whetstones at Ingleby Barwick, on the outcrop at the foot of the North Yorkshire Moors.Footnote 37 A whetstones found at St Albans may be of the Triassic Arden Sandstone,Footnote 38 a stone much favoured for building with an extensive outcrop in the English Midlands.

The Brownstones, discussed above, is not the only early Devonian (Lower Old Red Sandstone) formation to have been exploited for whetstones. The whetstones of red, micaceous sandstone found at Caerleon,Footnote 39 in south-east Wales, are plausibly from the slightly older St Maughan's Group, on the outcrop of which the fort and settlement stand. The amphitheatre, for example, is largely built of this material. Red siliceous sandstones of Devonian age also occur in the Borders and Midland Valley of Scotland, and are possible sources of Scottish finds.

FERRUGINOUS SANDSTONES

Five sites in south-central England have yielded whetstones attributed to ferruginous sandstone or ironstone (fig. 5B), also called ironpan, of which the best known to date are from Silchester.Footnote 40 These rocks are very fine- to medium-grained sandstones composed of angular to well-rounded quartz grains, with a little feldspar and rock fragments, set in a dense, opaque, pervasive matrix of iron oxy-hydroxides. The source of the whetstones appears to be local sandy deposits of various ages that were ferruginised in Pleistocene times in the zone of water-table fluctuation. Similar materials, potentially the source of other ferruginous sandstone whetstones, are widespread in the Pleistocene deposits of East AngliaFootnote 41 and the London Basin.Footnote 42 Of probably another origin is the ferruginous sandstone whetstone from Ewell, south of London, described as carstone from the local Lower Cretaceous Folkestone Beds.Footnote 43

SARSEN

Sarsen stone or silcrete is an off-white, well-sorted, fine- to medium-grained pure quartz sandstone with a secondary quartz or, less commonly, flint-like cement and a saccharoidal, partly open texture. It formed superficially in southern England on a number of occasions during Tertiary times, as the result of the leaching and silicification of sands, sandstones and flint gravels (these yield puddingstones).

Whetstones of sarsen stone are recordedFootnote 44 only from Silchester and Little Oakley, Essex, and are extremely rare. They appear to be mainly found objects.

WHETSTONES OF WEALDEN ORIGIN

An extraordinary discovery was made when the site of the forum at Roman Wroxeter (Uriconium) was excavated in the early twentieth century. Second-century deposits in the portico gutter along the east side yielded a considerable, and very rare, ‘pre-use’ assemblageFootnote 45 of nested samian vessels, Midlands mortaria and a consignment of about 100 unused, foot-length, sandstone whetstones, evidently manufactured by snapping individual bars off slabs of rock into which corresponding grooves had been sawn into the opposite faces, affording rebates of rectangular section along the long edges.Footnote 46 Atkinson considered the whetstones – patently a high-end product – to be evidence of a large and widespread business in Roman Britain, a view amply supported by subsequent work on their age and distribution (figs 6A, B). It is now clear that whetstones essentially identical to those at Wroxeter, dating from the first to the fourth centuries,Footnote 47 are widespread in Roman Britain (n=57) and also, on the basis of detailed petrological work,Footnote 48 across the English Channel in Gallia Belgica and Germania Inferior (n=21). In Britain, Wealden whetstones are reported from seven villas, 18 settlements and rural sites, 20 towns, three ritual sites and nine military contexts, including Hadrian's Wall and the Scottish Borders. At these locations, the average numbers of whetstones vary from 2.56 at the military sites to 3.9 in the towns and 3.3 at the ritual centres. On the near-Continent the whetstones appear chiefly in military contexts and in towns.

FIG. 6. Recorded whetstones of Wealden lithology in Roman Britain: (A) Distribution; (B) Distribution of whetstones of Wealden provenance in Roman Gallia Belgica and Germania Inferior, according to Reniere et al. (Reference Reniere, Thiébaux, Dreesen, Goemare and De Clercq2018); (C) Comparative spatial distributions (exponential) of Wealden whetstones over the land area of Roman Britain based on marketing from London or the quarry site in the north-west Weald, using a random sample of 20 sites (after Allen Reference Allen2016).

Views have changed considerably on the geological provenance of these whetstones. On palaeontological grounds, CantrillFootnote 49 assigned them to a horizon in the Middle Jurassic Great Oolite Series of the south Midlands. The most popular attribution has been to the Kentish rag facies of the Lower Cretaceous Hythe Beds of the Wealden area.Footnote 50 Neither proposal can now be supported by geological evidence. Allen and ScottFootnote 51 concluded on multiple grounds that the source rocks lay among the 30 or so thin, locally developed sandstone units present in the thick Weald Clay Formation of the north-west Weald, an older formation in the Lower Cretaceous sequence than the Hythe Beds. These Wealden sandstones, so the sedimentology of the whetstones showed, had accumulated on the shores and in the estuaries of a wooded landmass subject to frequent, seasonal wildfires. The rocks are greenish grey, delicately parallel-laminated, very fine- to fine-grained, firmly cemented, slightly micaceous, calcareous quartz sandstones. The quartz is angular, very well sorted and accompanied by a little chert, occasional feldspar and sporadic glauconite (a few grains only per thin section). Also present are variable amounts of bioclastic material, chiefly ostracod/pelecypod and sea-urchin debris, and scattered grains of charcoal, commonly showing anatomical structure.Footnote 52 Large, disarticulated shell fragments, attributable to the pelecypods Cardium and Ostrea, are found in some whetstones. Typically, the calcite cement, the soft element in the whetstones, is lustre-mottled on a millimetre scale.

The precise location in the north-west Weald of the quarries/mines where the sandstones were extracted remains unknown, but it is not necessarily true that the whetstones were also manufactured and marketed there. As has been shown,Footnote 53 and as is also evident in figure 6A, there is a clear, essentially northerly, exponential fall-off in the density of the sites that yield Wealden whetstones. Statistical analysis of the site distributionFootnote 54 reveals that the variance in plots of density–distance is significantly less when Roman London rather than a plausible location in the north-west Weald is chosen for the origin of the spread (fig. 6C). This is good evidence that the whetstones were marketed from London, probably by an agent, rather than from the Weald.

Speculating, the whetstones could also have been made in London. The River Wey, directed north-eastward to join the east-flowing Thames at Weybridge, is a tributary that offers a plausible route for the transport to London of sandstone slabs quarried in the north-west Weald. In that case, a waterfront location would be an appealing site for both a workshop and a trading centre. There is also a main road into London which emerges from the north-west Weald at Dorking.

Attention is convincingly drawn by Reniere and colleaguesFootnote 55 to the presence of low numbers of Wealden whetstones at Roman sites spread over the near-Continent (fig. 6B), especially military ones and towns, echoing the presence in the same region of pottery and other artefacts of British manufacture. A few of the sites are coastal, but most are concentrated in the middle River Scheldte basin. There are several possible explanations, including direct trade, for their presence,Footnote 56 but perhaps the most persuasive of those discussed by Morris, given the low numbers of finds and their locations, is the movement, with their families and goods, of especially Roman officials and military personnel from one posting to another during their career,Footnote 57 in keeping with the well-known ethnic diversity of Roman urban populations.

LIMESTONE WHETSTONES

Generally speaking, limestones do not make good whetstones, typically lacking the requisite hard and soft elements. It is therefore not surprising that they are represented only 17 times in the database, at sites limited to southern Britain.

SANDY LIMESTONES

The commonest (n=9) are described simply as sandy limestones, but those at NeathamFootnote 58 and ChichesterFootnote 59 are further reported to be glauconitic. Their findspots form a thin dispersion across southern Britain, without any obvious local concentration (fig. 7A). The sources of these whetstones are unknown, but it is worth noting that calcareous sandstones and sandy limestones are found at several horizons in the Lower and especially the Middle Jurassic of this general area. The two examples of glauconitic sandy limestone could be evidence for the exploitation of either an uppermost Jurassic formation or the true Lower Cretaceous Kentish rag (Hythe Beds), outcropping around the Weald in the south-east of the area.

FIG. 7. Distribution of recorded whetstones of limestone lithology: (A) sandy limestone; (B) shelly limestone; (C) Carboniferous Limestone; (D) Lias cementstone and sandy oolite.

SHELLY LIMESTONES

Just four locations have yielded whetstones described as shelly limestone. They occur in a loose string from Nantwich in the north-west Midlands to Portchester on the shores of the Solent (fig. 7B). Such rocks can be found in the Carboniferous Limestone Series of North Wales and the southern Pennines, but especially in the Jurassic strata of southern England.

(LOWER) CARBONIFEROUS LIMESTONE

There are two reports of whetstones of Carboniferous limestone (fig. 7C). That from St Albans (Verulamium) is remote from any outcrop of the Lower Carboniferous Limestone Series, and only the three finds from the military site of Castleford in West YorkshireFootnote 60 are at all nearby.

OTHER LIMESTONES

A whetstone from Roman Alcester (fig. 7D) is attributed to the Lower Jurassic Blue Lias,Footnote 61 a formation of alternating, thin shales and cementstones, outcropping near the site. A whetstone of these clay/silt-dominated materials may be expected to have afforded a fine edge or polish.

A solitary whetstone of sandy oolite is reported from the remote East Anglian site of Scole (fig. 7D).Footnote 62 Possibly a glacial erratic, an ultimate Middle-Upper Jurassic source is likely.

DISCUSSION

The database for the mappings described above has many clear and serious limitations, but these are not sufficient to cloud entirely the importance and role of whetstones in the economy of Roman Britain. A large and long-lived industry based on sandstones from the Weald Clay Formation (fig. 6) emerges with particular clarity, but there are hints of the existence of other significant industries based on the Millstone Grit and the Brownstones-Pennant sandstone.

BRITISH STONE-BASED INDUSTRIES

There is now a fair understanding of Roman industries procuring stone for building and the sources of stone exploited for other purposes. Formations used variously for rotary querns, millstones and mortars include the Upper Old Red Sandstone of the Welsh Borders,Footnote 63 the Millstone Grit of the Pennines,Footnote 64 the uppermost Jurassic of the Channel coast,Footnote 65 the Lower Cretaceous Lodsworth stone in south-east EnglandFootnote 66 and the silcretes (puddingstones) of the London Basin and East Anglia.Footnote 67

The millstone industry based on the Millstone Grit of the Pennines could have been more complex than is suggest by the millstones alone,Footnote 68 co-distributed with the whetstones mapped in figure 4C. Millstone Grit rotary querns/millstones and a few reused items are known from some of the findspots, but there are also bar and tablet whetstones from at least four locations. Are these items reused grinding stones, and therefore secondary, that have lost through wear all traces of their origin, or are they primary whetstones co-produced at, and co-marketed from, quarry sites along with the milling stones?

For whetstones of Brownstones-Pennant sandstone (fig. 3) and their possible aliases, micaceous sandstone (fig. 4A) and grey sandstone (fig. 4B), the case is supported by better evidence, and therefore more secure, although also more complex (fig. 8). These whetstones are co-distributed in the stone-tile belt that ranges from the Severn to the Thames.

FIG. 8. Speculative model for the entangled whetstone industry based on the Brownstones and Pennant sandstone of the West Midlands.

The outcrops of the Brownstones and Pennant sandstone in the Welsh Borders and West Country are essentially identical, and the roofing tiles produced from these formations are co-distributed in terms of both place and date, seemingly made available as decorative alternatives (red-brown or grey).Footnote 69 There is abundant evidence that the numerous tablet whetstones recorded from the findspots (fig. 3) have been made secondarily from roofing tiles,Footnote 70 but is this also true of the very many bar-shaped whetstones known? Some could plausibly have been manufactured at local centres from imported tiles – the size and shape of the latter is not inappropriate – and others co-produced and co-marketed at the primary quarry sites along also with tiles. A plausible picture tentatively presents itself of an entangled, multi-layered, mainly later Roman industry in Britain based on dispersed primary and secondary production centres, possibly affording for southern and eastern markets a range of stone products, including primary and secondary whetstones. Such an industry could be centrally controlled.Footnote 71

APPROACHES TO WHETSTONES

Three sequential steps of increasing difficulty are needed in order to gain a full appreciation of the archaeological significance of a stone artefact. The first step is to characterise petrologically and name the rock-type (mineral composition, texture, fabric, structures), emphasising critical diagnostic features. The second is to identify the geological formation from which the material for the item came (name, age, outcrop location and extent), together with its geological context (intrusive/extrusive igneous, low/high-grade metamorphic, sedimentology). The third step – the most difficult of the three – is to locate the exposure, quarry or mine from which the stone was extracted, or at least the likely district from which it came, and to place this in the context of a wider geographical distribution of the artefacts.

When the database exploited above is matched against this ambitious programme, its limitations and weaknesses – many surely avoidable – are at once exposed. How might matters turn out differently in the future? Several options for change are available, each with its particular attractions, disadvantages and resource implications: mount appropriate collaborative research programmes between professional geologists and archaeologists, as has been successful in the case of Roman Belgium;Footnote 72 prevail on commissioning and funding bodies to fund more generously, and monitor more rigorously, post-excavation work on stone artefacts; create accessible collections with commentaries of appropriate rocks in hand-specimen and thin-section form; invite appropriately resourced university departments to offer (for a fee) short residential courses in geology with an emphasis on British stratigraphy and petrography; encourage universities to include in their undergraduate degree programmes a module in geology, emphasising British stratigraphy and petrography. Perhaps the last option is the one most likely in the longer term to produce a significant change in the appreciation and treatment of whetstones.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am indebted to Dr Ruth Shaffrey for help with sources, and to Dr Rob Fry (University of Reading) for base maps.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

For supplementary material for this article, please visit <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0068113X22000277>.