Women played a vital role during the British industrialization. Their cheap, diligent, and flexible labor influenced the direction as well as the nature of the industrialization process (Honeyman Reference Honeyman2000: 36). From the centralized cotton factories in Lancashire to the traditional putting-out workshops in the countryside, female labor was a key determinant in the success of industrial capitalism (Berg Reference Berg1993; Hudson Reference Hudson1992; Lown Reference Lown1990). In addition, women’s contribution to the economy did not just confine itself to the formal labor market. The monetary returns to their labor may have been relatively small in comparison with men (Horrell and Humphries Reference Horrell and Humphries1995). Their nonmonetary contributions in the form of childcare, gleaning, managing household budget, and organizing credit nonetheless proved to be essential in many households’ well-being and survival (Humphries Reference Humphries1990; Lemire Reference Lemire2005; Sharpe Reference Sharpe1996).

Given women’s important contribution to the economy, an accurate assessment of female labor is needed to answer some of the most important questions in economic and social history such as economic productivity, real wages, and organization of household economy. Admittedly, the limited data availability has often hindered historians’ attempts to achieve such a goal. However, thanks to the digitization of the official statistics on women’s occupations in the census from mid-nineteenth century onward, there is now an unparalleled opportunity to systematically study women’s work and its impact on the market and household economy. But a critical evaluation of the empirical basis should always be undertaken before the making of major arguments. It is the aim of this article to contribute to the ongoing debate with regard to the quality of the information on female employment in the British census.

Ever since the publication of Edward Higgs’s article (Reference Higgs1987) drawing attention to the potential pitfalls of using British census statistics, the literature has never been short of criticisms of the accuracy of the census recording of women’s employment (Bourke Reference Bourke1994: 167; Burnette Reference Burnette2008; Davidoff and Hall Reference Davidoff and Hall1987: 27; Hill Reference Hill1993; Horrell and Humphries Reference Horrell and Humphries1995: 95; Roberts Reference Roberts1995: 18–19; Sharpe Reference Sharpe1995: 333; Verdon 1999). More recently, studies undertaken by Michael Anderson (Reference Anderson and Goose2007a, Reference Anderson and Goose2007b), Leigh Shaw-Taylor (Reference Shaw-Taylor and Goose2007), Timothy Hatton and Roy Bailey (Reference Hatton and Bailey2001), Sophie McGeevor (Reference McGeevor2014), as well as Higgs and Wilkinson (Reference Higgs and Wilkinson2016) launched a powerful counterargument to most of the criticisms and to some extent restored our faith in the census recording. However, even those optimists admit, due to married women’s general economic dependence on male wages and the irregular nature of their employment, census reporting of married women’s employment was most problematic (Shaw-Taylor Reference Shaw-Taylor and Goose2007).

So far the focus on married women’s employment in the census has been its underreporting. While this criticism is true in many case studies, it is certainly not the whole story. It is fair to argue that the most notable problem of using the census to study women’s employment is not its alleged inaccuracy. It is the fact that we still have not obtained a full picture of what exactly the nature and the scale of the problems are. As Higgs argues, “It is clear, therefore, that there is a considerable body of opinion that holds that the censuses under-enumerated the work of women during the Victorian era. What is less clear, however, is where the factual evidence for this conclusion with respect to the British censuses, at least in terms of occupational titles, is to be found” (Higgs and Wilkinson Reference Higgs and Wilkinson2016: 18–19). With criticism misplaced and attention mistargeted, any future effort to provide a reasonably accurate account of women’s work and its impact on the market and household economy would be in vain.

This article will enrich our understanding of the census recording of women’s employment by examining a particular issue pertaining to married women’s work. That is the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” in the Census Enumerators’ Books (hereafter CEBs) as well as the tabulation of “occupation’s wife” in the published census reports. This peculiar term as a description of married women’s occupations in the census deserves some terminological explanations. The occupation within the single quote refers to husband’s occupation. It could be farmer, butcher, agriculture laborer, and so forth. The occupational title for married women in concern then were farmer’s wife, butcher’s wife, agriculture laborer’s wife, and so forth. Unlike more conventional occupational titles such as “spinner” or “domestic servant,” the term “occupation’s wife” is embedded with conceptual ambiguity. Ascertaining which aspects of married women’s labor “occupation’s wife” tried to capture is one of the main objectives of this article.

There are only few existing studies of “occupation’s wife” and they have so far only focused on the inconsistent tabulation of “occupation’s wife” in the published census reports over time. It has been revealed that wives of farmers, shoemakers, butchers, shopkeepers, and innkeepers were considered by the census officials between 1851 and 1871 to be working together with their husband in the same trade. Hence, they were included in the employment totals in the published census reports. But from 1881 onward, they were assumed to be unoccupied. Based on this finding, Booth, Higgs, and McKay have all discussed its distortive effect on constructing a reliable series of women’s labor force participation rate (hereafter LFPR) over time (Booth Reference Booth1886; Higgs Reference Higgs1987; McKay Reference McKay and Goose2007). Female LFPR from 1881 onward, calculated from the census materials, was particularly underestimated. More recently, Humphries in her Ellen McArthur lectures uses “occupation’s wife” in the census as an example of married women gaining access to the labor market by the dint of their husband’s employment (Humphries Reference Humphries2016). She argues that, contrary to the belief that marriage limited women’s labor force participation, it enabled women’s employment in certain occupations. The aforementioned arguments are all based on the crucial assumption that “occupation’s wife” in the census indeed captured married women’s labor in the form of working together with their husband in the same trade. However, there has been no discussion on the validity of this assumption in the literature.

As will be demonstrated later in this article, women recorded as “occupation’s wife” constitute the largest group of married women with any occupational titles in the census. Therefore, to ascertain whether “occupation’s wife” captured married women’s work with their husband is not just an issue of technicality concerning the mechanism of census recording. It has a profound effect on solidifying the empirical basis for future studies of married women’s labor force participation. Two major findings will emerge from this article. First, “occupation’s wife” in the census does not reveal much about the true level of married women’s labor in the form of working together with their husband in the same trade. Second, the recording of “occupation’s wife” does reveal certain aspects of the gender relationship in the nineteenth century, particularly how the male adherence to domestic ideologies magnified women’s supposed domestic position as someone’s wife and ignored their economic function as wage earner and family business partner. However, it should be stressed at this point that it is not the author’s intention to discredit census materials as an invaluable source to study women’s employment in the nineteenth century. By identifying and discussing a problem that has so far been missing from the literature, the author only aims to enrich our understanding of the census and to facilitate future research using such material.

This article will be organized as follows. The first section will briefly discuss the source materials, namely the Integrated Census Microdata (hereafter I-CeM) data set of the CEBs and the published census reports in England and Wales between 1851 and 1911. The second section will analyze the tabulation of “occupation’s wife” in the published census reports. Patterns of the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs will be presented in the third section. The fourth section aims to find the rationale behind the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs. The fifth section will use “farmer’s wife” in the 1881 CEBs as a particular example to further the argument. Some caveats and conclusion will be presented in the last two sections.

Source Materials

This article uses two related, and yet not completely synonymous, bodies of census materials: the 100 percent sample of CEBs in England and Wales between 1851 and 1911 (with the exception of 1871) and the published census reports in England and Wales between 1851 and 1911. The biggest difference between the CEBs and the published census report is that the former contain nominal data at the individual level while the latter only contain tabulations grouped by sex, age, and various geographical units based on the information recorded in the CEBs. The British censuses started recording female occupations from 1841, but it was not until 1851 that it started to be fit for analytical purposes (Higgs Reference Higgs1987: 63). Although the exact enumeration procedures may have varied slightly across different census years since 1851, the core procedures by which the censuses were taken were similar (Higgs Reference Higgs2005; Mills and Schürer Reference Mills, Schürer, Mills and Schürer1996).

There were more than 600 registration districts in England and Wales in the mid-nineteenth century. Each of them was under the charge of a superintendent registrar. These registration districts were further divided into subdistricts, each under the charge of a registrar. Registrars were instructed to divide their subdistricts into Enumeration Districts (hereafter EDs). EDs were the geographical basis in which the census enumeration took place, and each ED was in the charge of a census enumerator. However, it should be noted that EDs often do not coincide with parishes.Footnote 1 EDs were supposed to be of fairly standard size either in terms of population or geography (Higgs Reference Higgs2005: 37–38). Census enumerators distributed the household schedules to householders over the previous week before the census night. Information requested in the household schedules were the address of the household, as well as the name, relationship to household head, marital status, sex, age, “[r]ank, profession or occupation,” birthplace, and description of medical disability for each person residing in it on the census night as well as those returning to the household in the morning. The occupational recording under the “[r]ank, profession or occupation” column are the core information on which this article relies. With regard to filling this column, there were a set of instructions that householders were supposed to follow. Census enumerators then transferred the information from household schedules to their CEBs with certain revisions and checks, according to the instructions given to them, in the morning after the census night. The CEBs were then sent to the local registrars and superintendent registrars. At each stage examinations, checks and simple tabulations were performed (Woollard Reference Woollard1998). Then the CEBs, household schedules, and various summary forms were sent to the Census Office in London. Here, some 60 clerks, with a set of instructions given to them, spent around three months undertaking further checks on the CEBs and performing the tabulations that led to various tables in the published census reports. It is clear that the CEBs were regarded by the census authorities only as the medium by which the end product, namely the published reports were to be obtained. The editorial interference—such as revisions, checks, and standardization—carried out during each stage before the finalization of the published census reports could add further alterations to the enumerators’ initial recordings in the CEBs (ibid.). The only notable exception to the aforementioned procedures occurred in 1911 when the original household schedules rather than the CEBs formed the basis for the tabulation in the published census reports.

The sheer volume of data contained in the CEBs and published census reports constitutes an analytical obstacle. For example, the 1851 CEBs in England and Wales contain circa 18 million individual records; the 1911 CEBs in England and Wales contain circa 36 million individual records. Without them available in a machine-readable form, it would be impossible to conduct detailed research so that their full potential could be realized. Fortunately, the digitization is done now. The I-CeM projectFootnote 2 led by Schürer and Higgs, with the raw data supplied by their commercial partner FindMyPast, created a digitized and standardized data set of all the CEBs between 1851 and 1911, with the only exception being 1871.Footnote 3 In this data set, they reformatted the input data, performed a number of consistency checks, coded the nonstandard textual occupational strings with the occupational classification, added a number of enriched variables relating to household structure,Footnote 4 and linked the data set to the GIS boundary data so that cartographical representation could be produced.Footnote 5 Shaw-Taylor et al. at the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure (hereafter Campop) undertook further checks and corrections to the I-CeM data set. The published census reports were digitized by Campop as part of the Occupation Project led by Shaw-Taylor and Wrigley.Footnote 6 The data set of published census reports was also linked to GIS boundary data. Furthermore, this article will also utilize the farm acreage information that Gill Newton extracted from the 1881 CEBs as part of the Entrepreneurship Project led by Bennett at Campop.Footnote 7

“Occupation’s Wife” in Published Census Reports

The tabulation of “occupation’s wife” was inconsistent over time in the published census reports. Prior to 1881, wives of farmers, shoemakers, butchers, shopkeepers, and innkeepers were assumed to be working together with their husband in the same trade. Hence, they were included in the employment totals in the published census reports. For instance, one item in the instructions to the census clerks employed in producing the published census reports in 1871 reads:

The WIVES of the following Persons are supposed to take part immediately in their Husband’s business, and they are therefore to be ticked on their respective lines in 4:1, unless they are expressly returned as following an independent occupation, in which case they must be dealt with as hereafter directed:--

Wife of Innkeeper, Hotelkeeper, Publican, Beerseller.

Wife of Lodging House, Boarding House-Keeper.

Wife of Shopkeeper (branch undefined).

Wife of Farmer, Grazier (but not of Farm Bailiff).

Wife of Shoemaker.

Wife of Butcher.Footnote 8

However, these items were omitted from the instructions to the clerks from 1881 onward. Those wives, who were previously taken as part of the employment totals, were no longer regarded as taking part in the labor force. Instead, they were consigned to the category of “unoccupied.” Higgs argues that this was largely due to the changing paradigms of the Victorian social sciences in the late nineteenth century (Higgs Reference Higgs1987: 71). Such change persuaded the census authorities to reconstruct the occupational census from 1881 onward in a form to emphasize more on paid labor in a market economy (ibid.).

The distortive effect of changes in the tabulation of “occupation’s wife” on constructing a consistent series of married women’s LFPR over time has been acknowledged. McKay in addressing Hunt’s assertion of a declining married women’s LFPR over the second half of the nineteenth century (Hunt Reference Hunt1981: 18), compares married women’s employment figures in 1851 and 1911 published census reports (McKay Reference McKay and Goose2007). While the employment totals give married women’s LFPR of about 25 percent in 1851, married women’s LFPR in 1911 was just about 10 percent. But after artificially deducting those wives from the 1851 employment totals, he finds that married women’s LFPR in these two census years was at the similar level (ibid.).

The implication of “occupation’s wife” on calculating female LFPR in general is significant as well. Charles Booth, for example, had to artificially reassign wives included in the pre-1881 employment totals to the unoccupied category to arrive at a more consistent series of female LFPR over time (Booth Reference Booth1886). With this revision, it can be shown that a 10 percent point gap in female LFPR between 1851 and 1911 would largely disappear.

Consistency, however, does not necessarily mean accuracy. Firstly, part of the census authority’s assumption behind the inclusion of these wives in the employment totals rings true. It was probable that some of these wives were engaged in the same trade with their husbands. Even if they were not paid as others with independent occupational titles, the produce of their labor was likely to enter a wider market economy rather than just for home consumption. In that sense, they were unmistakably a part of the market economy. Secondly, the aforementioned treatment of “occupation’s wife” ignored the time-variant aspect of the likelihood of married couples working together. Given the changes in the underlying economy, the opportunities for married couples working together in the same trade may have indeed become more limited over time. Therefore, deducting all these wives from the employment totals between 1851 and 1871 would produce an underestimation of married women’s LFPR as well as female LFPR in general. However, the scale of the underestimation depends on if the number of married women returned in the published censuses as “occupation’s wife” faithfully reflected the true level of their work in the same trade with their husbands. Unfortunately, this is unlikely to be true.

The number of married women returned in the published census reports as “occupation’s wife” is likely to represent a form of overreporting of female employment. It can be revealed that this occupational title hardly had any discriminate nature concerning married women’s actual employment. The fact that they were married to men in these occupations alone sufficed for them to be considered as being employed. The aforementioned instructions to census clerks provide the first clue. These instructions seem to suggest the clerks to tabulate all married women whose husbands were farmers and butchers and so forth as “farmer’s wife” and “butcher’s wife,” unless they were returned with independent occupational titles in the CEBs. However, to what extent these instructions were faithfully executed by the clerks remains unclear, unless we can directly compare the published figures with those extracted from the CEBs.

Table 1, using the census year of 1851 as an example, compares the number of married women returned as “occupation’s wife” in the published census reports with the corresponding figures extracted from the CEBs. The first column states husband’s occupations. It shows that these instructions to the clerks were indeed well implemented. Across all these occupations, the proportion of married women who were tabulated as “occupation’s wife” in the published reports (column 6) is always radically higher than the proportion of married women being enumerated as such in the CEBs (column 4). For instance, less than 10 percent of women married to shoemakers were enumerated as “shoemaker’s wife” in the CEBs. However, the published census reports tabulated nearly 85 percent of women married to shoemakers as “shoemaker’s wife.” It is clear that, apart from those married women enumerated as such in the CEBs, clerks also tabulated married women with no stated occupation as “occupation’s wife” in the published reports. In addition, there is also evidence suggesting that some clerks went against the instruction and even tabulated some married women with independent occupational titles in the CEBs as “occupation’s wife” in the published reports. Had the clerks only tabulated those married women who were enumerated either as “occupation’s wife” or with no occupational title in the CEBs as “occupation’s wife” in the published reports, column 7 should be close to zero. However, that is not the case. For example, with regard to “farmer’s wife,” column 7 shows that 18 percent of all the “farmer’s wife” tabulated in the published reports cannot be accounted for by married women either recorded as “occupation’s wife” or with no occupational title in the CEBs. The only possible explanation is that some married women with independent occupational titles in the CEBs were instead tabulated as “farmer’s wife” in the published reports.

Table 1. Number of married women tabulated as “occupation’s wife” in the published census reports and number of married women enumerated as “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs, 1851

Sources: 1851 census, P.P. 1852–53, LXXXVII, population tables II, vols. I to II, parts I to II, population tables, occupations of the people. 1851 CEBs from I-CeM data set.

Note: Innkeepers, publicans, beerseller, hotelkeepers, lodging housekeeper, and boarding housekeepers are put together in the single category “innkeeper etc.” in table 1.

The different recording rates of “occupation’s wife” between the CEBs and the published reports on its own cannot gauge which one is more accurate. However, unless in reality almost all married couples in farming and innkeeping and so forth worked together, as table 1 suggests, the published reports between 1851 and 1871 overestimated the number of married women working with their husbands in those trades. Meanwhile, the published reports may have underreported the number of married women working with their husbands in other trades. The list of “occupation’s wife” included in the published reports was unlikely to be exclusive. There may have been other occupations in which married couples worked together in the same trade. So a question still remains: What was the true level of married women’s employment with their husband in the same trade? If the published census figures could tell us little about this issue, would the original enumeration in the CEBs be able to solve the puzzle? This will be the focus of the following sections.

“Occupation’s Wife” in CEBs

The scale of the enumeration of married women as “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs is massive, at least between 1851 and 1881. Table 2 shows the proportion of married women enumerated with independent occupational titles and as “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs between 1851 and 1911. There were nearly as many married women enumerated as “occupation’s wife” as those with independent occupational titles between 1851 and 1881. In the 1881 CEBs, there were even more former than the latter. In addition, it can be shown that, up until 1881, the number of married women enumerated as “occupation’s wife” was almost 10 times larger than that enumerated with the most common independent occupational title and 3 times as large as the collective group that enumerated with the top five most common independent occupation titles. The enumeration rate of “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs declined dramatically after 1881. But even so, married women enumerated as such still represented a substantial group of married women with any occupational titles. Taking the census year of 1901 as an example when the enumeration rate of “occupation’s wife” was the lowest, it was still the fifth largest “employer” of married women out of about six hundred standardized occupations in the CEBs. Without any doubt, “occupation’s wife” as a generic occupational group accounted for more married women’s employment than any independent occupational title in the CEBs between 1851 and 1911.

Table 2. Married women enumerated with independent occupational titles and as “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs in England and Wales between 1851 and 1911

Sources: I-CeM data set.

Note α: The top five most common independent occupational titles for married women between 1851 and 1911 in descending order are as follows. The number of married women enumerated with each occupational title is included in the parentheses.

1851: laundry workers (37,370), dressmakers (33,858), domestic servants (27,149), agricultural laborers/farm servants (16,937), and weavers (15,100).

1861: dressmakers (48,650), laundry workers (47,235), domestic servants (32,532), cotton manufacture (25,859), and agricultural laborers/farm servants (20,196).

1881: laundry workers (56,317), dressmakers (54,145), domestic servants (46,099), cotton manufacture (35,592), and charwomen (18,126).

1891: laundry workers (54,142), dressmakers (37,374), cotton manufacture (32,229), tailors (18,965), and charwomen (18,931).

1901: laundry workers (44,082), cotton manufacture (33,124), dressmakers (29,236), charwomen (17,142), and domestic servants (14,487).

1911: domestic servants (60,769), cotton manufacture (35,645), laundry workers (32,669), dressmakers (23,745), charwomen (19,354).

Apart from the sheer number of women enumerated as “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs, its enumeration was also prevalent across a wide spectrum of occupations. As shown in the previous section, there were only five occupations against which “occupation’s wife” was tabulated in the published census reports. However, many more occupations had the corresponding enumeration of “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs. Again, taking the 1881 CEBs as an example, it can be shown that, out of all the standardized occupations where married men’s employment can be found, all but three had corresponding enumerations of “occupation’s wife.”

The large number of married women enumerated as “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs as well as the wide spectrum of occupations involved in such enumerations are puzzling. As mentioned previously, there were instructions to census clerks as what and how to tabulate “occupation’s wife” in the published census. But no such instructions related to “occupation’s wife” were given to householders or enumerators in producing the CEBs. The only entity on the household schedule that may have had a weak link to the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs was “farmer’s wife” given as an example on how to fill up the occupational column. But no other “occupation’s wife” was given as an example. Many enumerators and householders before 1891 may have taken the single example of “farmer’s wife” in the household schedule as a general guidance to record married women as “occupation’s wife” regardless of their husband’s occupations. Even the example of “farmer’s wife” was dropped out of the household schedule after 1881. This change may partly explain the dramatic decline on the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” in the post-1881 CEBs. However, whether this simple change was powerful enough to account for such a dramatic decline is still debatable. More research should be directed toward it. But it is beyond the scope of this article to develop this topic any further.

As the criteria by which married women should be enumerated as “occupation’s wife” remains a black box, this creates a conceptual ambiguity and leaves much room for different interpretations. Most intuitively and straightforwardly, one may argue it represented married women’s labor in the form of working together with their husband in the same trade. This was also the reason behind the census authorities’ decision to include certain “occupation’s wife” in the employment totals in the published census report between 1851 and 1871. In this case, married women who were enumerated as “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs should be rightly regarded as being active in the labor market. But at the same time, one may also argue this term is more of an acknowledgment of married women’s domestic contribution at home such as washing, cooking, and childcare. In this case, they probably should not be included in the calculation of total employment for two reasons. First, no one can deny the economic value of married women’s domestic contributions. They greatly reduced the opportunity cost of family members’ participation in the labor market (Field Reference Field2013: 257; Horn Reference Horn1990: 124–32, 184–88). But they did not possess the same characters as those, such as weaving in factories, that received monetary returns and whose output directly entered the market economy. Should they be included in the employment figures in the same way as those with independent occupational titles, the employment totals could be misleading. Second, within the broader socioeconomic environment, married women were almost always responsible for unpaid domestic labor (Aktinson Reference Aktinson2012: 154–58; de Vries Reference De Vries2008: 186–89; Perkin Reference Perkin1989: 141–46; Rose Reference Rose1992: 93–100; Ross Reference Ross1993; Seccombe Reference Seccombe1986). Should only those married women enumerated as “occupation’s wife” be regarded as participating in the labor market, we will be implicitly applying different definitions to the same work done by married women. Meanwhile, if we recognize all married women’s domestic contribution as labor force participation, then married women’s LFPR would be nearly 100 percent. Distinctions between different types of married women’s work are needed to avoid such meaningless statistics in the context of calculating LFPR. This is not to undermine the value of married women’s domestic work. It only suggests that different frameworks are needed to analyze married women’s domestic work and gainful employment separately.

The prevalence of “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs together with the difficulty of interpreting its true meaning has an overwhelming implication in studying married women’s LFPR from the CEBs. Perhaps the most obvious example is when one tries to analyze the spatial patterns of married women’s LFPR. Figure 1 compares the spatial patterns of married women’s LFPR by making different assumptions with regard to the status of “occupation’s wife” in the labor force, namely either assuming they were active in the labor market and included in the female labor force or they were not directly a part of the market economy and excluded from the female labor force. Three distinctions can be drawn. First, married women’s LFPR would become higher in more than 75 percent of all parishes if we assume “occupation’s wife” was active in the labor market. Second, much fewer parishes would have 0 percent married women’s LFPR if we assume “occupation’s wife” was active in the labor market. For instance, more than 21 percent of all parishes would have a married women’s LFPR of 0 percent if we assume “occupation’s wife” was not active in the labor market. But this figure would drop to 9 percent if we assume the opposite. Third, and more importantly, different assumptions about “occupation’s wife” would lead to dramatic changes in the relative spatial pattern of married women’s LFPR. Married women’s LFPR, which is derived only from the independent occupational titles (map on the left panel in figure 1), shows a spatial pattern that is clearly associated with the economic geography, particularly concerning the demand for female labor. While most of the country saw married women’s LFPR below 10 percent, higher rates can be found in areas where demand for female labor was greater, for instance, the cotton districts in Lancashire, woolen districts in Yorkshire West Riding, straw plaiting and lacemaking districts in South East Midlands, nail making districts in West Midlands, and silk manufacturing districts on the Suffolk and Essex border.Footnote 9 The spatial pattern of married women’s LFPR appears very different if one assumes “occupation’s wife” was active in the labor market (map on the right panel in figure 1). On the one hand, West Wales and the Pennines would see clear concentrations of high levels of married women’s LFPR. This may partly be explained by the prevalence of small family farms and dairy farms in these regions. On the other hand, the areas identified with higher married women’s LFPR on the left panel in figure 1 cease to stand out in comparison with the rest of the country on the right panel. Instead, many parishes with married women’s LFPR greater than 80 percent can be found scattered around the country.

Figure 1. Spatial pattern of married women’s LFPR in England and Wales, 1881.

It is clear that the conceptual ambiguity as well as the large scale of “occupation’s wife” recorded in the CEBs create an empirical uncertainty concerning married women’s labor force participation. This empirical uncertainty in turn could imperil historians’ endeavors to answer important questions such as: (1) What was the true level of married women’s employment? (2) What was the driving forces behind married women’s labor force participation? (3) How did married women respond to socioeconomic variations both inside and outside the home? The key to solve this problem is to ascertain which aspect of married women’s work “occupation’s wife” tried to capture in the CEBs.

Working with Husband?

The seemingly most credible hypothesis is that the term “occupation’s wife” represents married women’s labor in the form of working together with their husbands in the same trade (Humphries Reference Humphries2016). Under this hypothesis, the fact that, for example, 11 percent of women married to shoemakers were enumerated as “shoemaker’s wife” in the 1881 CEBs should be interpreted as about 11 percent of women married to shoemakers working together with their husband in shoemaking. An effective way to test this hypothesis is to investigate the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” by husband’s occupation in the CEBs. If this hypothesis holds true, we would expect to observe the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” only in or, at least highly skewed toward, economic sectors and occupations that were largely household based mainly utilizing labor input from family members.

The evidence from the CEBs goes against this hypothesis. Taking the 1881 CEBs for example, table 3 shows the proportion of married women enumerated as “occupation’s wife” by their husband’s employment sector and major subsectors in the PST occupational classification scheme.Footnote 10 Two messages become immediately clear. First, “occupation’s wife” can be found in all economic sectors and subsectors, even when there was virtually no room for married couples to work together in the same trade. Second, even with variations, the enumeration rate of “occupation’s wife” did not show clear skew toward economic activities such as earthenware manufacture and shoemaking that had greater likelihood for married couples to work together in the same trade. This suggests that “occupation’s wife” fails to distinguish between different groups of married women based on their actual form of labor input and provides little indication of married women working together with their husband in the same trade.

Table 3. Enumeration rate of “occupation’s wife” by husband’s employment sectors and subsectors in England and Wales, 1881

Sources: 1881 CEBs from I-CeM data set.

The primary sector had the highest enumeration rate of “occupation’s wife.” Agriculture and fishing are probably the only two subsectors within the primary sector that offered the possibility for married women to work with their husband in the same trade. Some women married to farmers helped the daily running of the farm (Ellis Reference Ellis1750; Henry Reference Henry1771: 23; Loudon Reference Loudon1831: 1036; Verdon Reference Verdon2003). Agricultural laborers’ wives were sometimes found working with their husbands in harvesting (Burnette Reference Burnette2007; Verdon Reference Verdon2002: 120). Fishermen’s wives were likely to be engaged in activities such as gutting, baiting, and net-repairing in the inshore fisheries. Other economic activities in the primary sector such as forestry and mining were extremely unlikely to offer such possibility. However, the recording of “occupation’s wife” can be found in these subsectors as well with similar enumeration rates. But it would certainly be wrong to argue, for example on the basis of the enumeration of “miner’s wife,” that nearly 15 percent of women married to miners were also employed in mining.Footnote 11 Similar observations can be found in the secondary and tertiary sectors as well. Within the secondary sector, clothing, footwear, and earthenware were in reality more likely to have married women working with their husband in the same trade (Dupree Reference Dupree1995). The enumeration rate of “occupation’s wife” in these subsectors was around 10 percent. However, similar enumeration rates can also be found in industries such as building and construction as well as iron and steel manufacture. These subsectors are well known for the near absence of female workforce (Burnette Reference Burnette2008: 19–20; Jordan Reference Jordan1988, Reference Jordan1989). It is beyond doubt there was little room for married women to work together with their husband in the same trade in these subsectors. Within the tertiary sector, there was room for married couples to work together in selling and hawking. However, the similar enumeration rate of “occupation’s wife” can also be found in professions and services as well as transport. The subsector professions and services included occupations such as lawyers, bankers, and managers. It is highly unlikely that women married to these professionals would work in the same trade. Neither was it likely that married women whose husbands were employed in transport, such as railway engineers or stagecoach drivers, worked together with their husband in the same trade.

The argument that the term “occupation’s wife” indicates little about married women’s labor in the form of working together with their husband in the same trade becomes even more apparent if we analyze its enumeration rate by husband’s specific occupations. As alluded to in the previous section, out of all the standardized occupations where married men’s employment can be found, all but three had the corresponding enumerations of “occupation’s wife” in the 1881 CEBs. This is perhaps the most revealing evidence against the claim that married women who were enumerated as “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs worked with their husband in the same trade. It is simply inconceivable that almost all occupations in the British economy in the last quarter of the nineteenth century could offer such opportunities.

Occupations such as shopkeepers and shoemakers were indeed likely to have married couples working together, and hence the correspondingly “occupation’s wife” was included in the employment totals in some published reports. However, it can be shown that the enumeration rate of “occupation’s wife” for most occupations in the CEBs was similar to those such as shopkeeper and shoemaker. For example, the mean and median enumeration rates among all “occupation’s wife” in the 1881 CEBs were 13.8 percent and 10.1 percent as against 11.5 percent for “shopkeeper’s wife.” That is to say, most married women were almost equally likely to be enumerated as “occupation’s wife” regardless of whether in reality they worked with their husband in the same trade or not. Furthermore, it can be shown that the number of married women enumerated as “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs for those occupations such as farmers and shoemakers, which were more likely to employ married couples together only covered less than fifth of all married women who were enumerated as “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs. The rest of the occupations, which were less likely to have married couples working together, accounted for the majority of married women enumerated so in the CEBs.

The argument that “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs indicates little about married women working with their husband in the same trade can be further strengthened by analyzing the enumeration rate of “occupation’s wife” by ED. It can be shown that there were enumerators who simply recorded all married women in their EDs as “occupation’s wife”; a significant proportion of enumerators recorded almost all married women in their EDs as “occupation’s wife”; and a large number of enumerators did not use the term “occupation’s wife” in their enumeration at all. This is strong evidence showing that enumerators, when deciding whether to use “occupation’s wife” as an occupational title, paid little attention to the fact of whether married women worked with their husband in the same trade or not. The indiscriminate nature of the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” in many cases as well as the absence of the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” in others strongly suggests that its enumeration was heavily influenced by enumerators’ idiosyncrasies. It bears little resemblance to the true level of married women working with their husbands.

As alluded to in the first section, parishes and EDs often do not coincide (Higgs Reference Higgs2005: 37–38). While parishes identifiers are available for all census years in I-CeM database, ED identifiers are currently only available for the census year 1861.Footnote 12 So let us use 1861 as an example. The results pertaining to the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” by ED in the 1861 CEBs are presented in table 4.Footnote 13 Nearly 270 enumerators recorded all married women in their districts as “occupation’s wife.” The number of married women in these districts is greater than 12,000. It is inconceivable that, regardless of the local economic conditions and their husband’s occupations, all married women from these districts worked together with their husbands in the same trade. It is the clearest example of enumerators’ idiosyncrasies presiding over reality to yield faulty enumeration practice in the extreme.

Table 4. Proportion of married women enumerated as “occupation’s wife” in different types of Enumeration Districts in England and Wales, 1861

Sources: 1861 CEBs in I-CeM data set.

In comparison with the total number of EDs where “occupation’s wife” can be found and the total number of married women enumerated as such in the country, the corresponding figures from these 269 districts may not seem particularly large. However, this is not the only case showing the effect of enumerators’ idiosyncrasies on the enumeration of “occupation’s wife.” Many enumerators recorded almost all married women in their districts as “occupation’s wife.” With regard to the districts where more than 90 percent of married women were enumerated as “occupation’s wife,” the number of married women enumerated as such in these districts accounted for nearly 25 percent of all married women enumerated as such in the country. With regard to the districts where more than 75 percent of married women were enumerated as “occupation’s wife,” this figure jumps to more than 40 percent (column 6).

The fact that not all married women were enumerated as “occupation’s wife” in these districts does not necessarily mean that careful deliberations were made by enumerators as to whether married women worked with their husband or not. Column 7 in table 4 shows that, on average, the population size of these districts was much larger than that of the districts where all married women were enumerated as “occupation’s wife.” This implies, and as supported by column 8 in table 4, that these more populated districts can be expected to have a more diverse labor market. This in turn made it more likely for some married women to have independent occupations outside the home. In this case, male household header would be likely to return these married women as someone with independent occupational titles in the household schedule. Given this, it is unlikely that enumerators would deliberately go against what was recorded in the household schedules and record all married women as “occupation’s wife” instead. This is the reason why not all married women were recorded as “occupation’s wife” in these EDs. But the high enumeration rate of “occupation’s wife,” say more than 90 percent, nevertheless indicates that for married women without an independent occupational title in these EDs, they were enumerated as “occupation’s wife” anyway regardless of whether they worked with their husband in the same trade. In that sense, the term “occupation’s wife” to some extent managed to separate those women enumerated as such from those enumerated with independent occupational titles, depending on whether or not they regularly participated in the labor market outside the home. But for married women who were enumerated as “occupation’s wife,” it still failed to separate those who were genuinely working together with their husband in the same trade from those who were not.

On the other extreme, there were EDs where no married women were enumerated as “occupation’s wife” at all (penultimate row in table 4). The number of this type of EDs accounted for more than 35 percent of all the EDs in the country. This is another strong piece of evidence supporting the argument that the enumeration of “occupation’s wife,” or the lack of it, heavily depended on individual enumerators’ idiosyncrasies. If the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” were to capture married women’s work with their husband, one should expect to find a marked difference in married men’s occupational structure between EDs with the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” and EDs without. The latter should have almost no occupations that could offer married couples the opportunity to work together. But it can be shown from the 1861 CEBs that married men from the former group of districts were employed in 703 occupations out of the total of 707, while married men in the latter group can be found in 705 occupations. The potential scope for married couples to work together in the same trade was similar between these two groups of EDs. Table 5 shows married men’s occupational structure in these two groups of EDs. There is a difference between the two with the primary sector covering a larger share of married men’s employment in the EDs with the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” than those without. Given the higher enumeration rate of “farmer’s wife” identified in the fourth section, this can partly explain the higher probability of finding “occupation’s wife” in the former group of EDs but it cannot at all explain the complete absence of “occupation’s wife” in the latter group. Instead of difference, the most important message from table 5 is the similarity of married men’s occupational structure between these two groups. It is clear that the latter group of EDs also offered opportunities for married couples to work together in the same trade. On the one hand, as shown before, enumerators’ idiosyncrasy led to an overestimate of the scale of married couples working together in many of the districts in the former group. On the other hand, it led to an extreme underestimate in the latter group.

Table 5. Married men’s occupational structure in different types of Enumeration Districts distinguished by the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” in England and Wales, 1861

Sources: 1861 CEBs from I-CeM data set.

Individual enumerators’ idiosyncrasies in the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” was likely to be the product of Victorian domestic ideology. Originating from the evangelical movement and widely supported by the British middle and upper classes, Victorian domestic ideology assumed and promoted the key role of women as the “angel at home” offering companionship and care to other household members as wives, mothers, daughters, or sister (Hall Reference Hall and Sandra1979; Rose Reference Rose1986). It argued that this domestic position was the only proper role for which women should be recognized and it discredited and discouraged women’s physical toil as inappropriate to their gender and morally corrupting.Footnote 14 It is still debatable how far this ideology trickled down the social hierarchy and to what extent it altered most families’ labor supply strategy in light of economic reality (Vickery Reference Vickery1993). But based on the enumeration patterns of “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs, it is clear that many male enumerators were more than willing to recognize married women solely through their supposed domestic position as someone’s wife. In that sense, “occupation’s wife” seems to be more of a domestic title than an occupational title. Instead of showing married women’s employment, it was more indicative of the gender relationship in Victorian England and Wales. The male adherence to rigid gender role and domestic status quo, it appears, turned a blind eye to many married women’s economic function as wage earner or family business partner, even if in many cases married women’s work with their husband was crucial in the household economy characterized by frail breadwinners. The lack of enumeration of “occupation’s wife” in many other EDs does not mean they were free from the influence of this domestic ideology either. In a different form, it led male enumerators to completely ignore married women’s work, either with their husband or outside the home, and gave them no recording under the occupational column at all. The underreporting of married women’s employment in this form is well documented by the existing literature (Higgs Reference Higgs1987).

By examining the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” by husband’s occupation and EDs, this section shows that its enumeration was heavily influenced by individual enumerators’ idiosyncrasies, which was possibly the result of Victorian domestic ideology. The term “occupation’s wife” had little credibility in indicating married women’s labor in the form of working together with their husband in the same trade for most occupations. However, one question remains: Did the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” at least capture married women’s work with their husband in occupations such as farmer and shoemaker where the likelihood of married couples working together was higher? Using farmer and farmer’s wife as an example, this will be the focus of next section.

Farmer’s Wife as a Case Study: Their Work and CEB Recordings

The enumeration of “farmer’s wife” in the CEBs is a good case study to test the hypothesis put forward at the end of the last section. Whether married couples worked together in the same trade did not only depend on the type of husband’s trade but also the nature and the scale of the business operation. While such information is not readily available in the CEBs for most occupations, it is available for farmers. The scale of farmers’ business operation can be assessed by farm acreage.

In the census household schedules, farmers were asked not only to return their occupation but also the acreage of his or her farm as well as the number of laborers employed on the farm.Footnote 15 For example, one item from the instructions to householders on how to fill in the household schedule in 1881 reads:

FARMERS to state the number of acres occupied, and the number of men, women, and boys employed on the farm at the time the Census.—Example: ”Farmer of 317 Acres, employing 8 Labourers and 3 Boys.”

The information pertaining to farm acreage have been extracted from the 1881 CEBs as part of the Entrepreneurship Project led by Bennett at Campop.Footnote 16 However, it should be noted that not all farmers followed the instructions given to them. Some of them simply recorded themselves as farmer without giving any information on farm acreage. Out of 263,933 farmers identified in the 1881 CEBs, 198,097 of them, that is about 75 percent, returned farm acreage information. Out of 172,098 married male farmers identified in the 1881 CEBs, 135,900 of them, that is about 80 percent, returned farm acreage information. The rest of the section will only focus on farmers who returned farm acreage.

The existing historiography identified an inverse relationship between farm size and likelihood of family members’ engagement in farming activities. Allen argues that farms of 50 to 60 acres were family farms and could be operated by family members without much hired labor. By contrast, farms of more than 100 acres were capitalist farms and were run predominately by hired labor. Farms of 60 to 100 acres, in the middle, were transitional farms employing roughly equal amount of family and hired labor (Allen Reference Allen1992: 57). Shaw-Taylor criticizes Allen’s approach of applying a single set of acreage thresholds to capture the characteristic of farming employment across the country. He finds the threshold of farm acreage by which no hired labor was required varied greatly across the country. However, despite the regional diversity, he too finds a general inverse relationship between farm size and likelihood of family labor in farming (Shaw-Taylor Reference Shaw-Taylor2012). In counties south and east of a line between Dorset and the Wash, average farm sizes were much larger than the rest of the country, and the proportion of farms utilizing any family members’ labor in these counties was much smaller than the rest of the country (ibid.: 35–39). This inverse relationship was recognized by contemporary observers as well. While farmers’ wives in large farms were criticized for retreating back to the home and distancing themselves from farming activities, farmers’ wives in small farms were praised for their farming labor in assisting their husband (Cobbett Reference Cobbett1985 [1830]: 226–27; Howitt Reference Howitt1884: 104; Loudon Reference Loudon1831: 1036). Verdon, drawing on evidence from contemporary manuals and encyclopedias, highlights the fact married women in smaller farms were more likely to be involved in farming activities than married women in large farms (Verdon Reference Verdon2003). The distinction between the activities of farmers’ wives by farm size was clearly marked over the nineteenth century. Farmers’ wives in large farms, who were enabled by healthy family income and being status conscious, increasingly distanced themselves from the farming activities. This led William Cobbett to describe them as the “Mistress Within” (Cobbett Reference Cobbett1985 [1830]: 229). But at the same time, farmers’ wives in small farms, particularly in north west England, were still engaged in a wide spectrum of customary farming activities, ranging from manual labor on the field, pig rearing, poultry keeping, cheese making, beekeeping, and food preserving, that formed an integral part of the household economy (Verdon Reference Verdon2003: 34–35; Winstanley Reference Winstanley1996). Apart from farm size, the function of the farm, namely whether being an arable farm or dairy farm, is also a factor affecting the likelihood of married women’s engagement in farming activities. Before the nineteenth century, dairy work, either manual or supervisory, was seen as a natural task of farmer’s wife (Verdon Reference Verdon2003: 28–29). However, given the increasing commercialization over the nineteenth century, even within dairy farming, farmer’s wife on large dairy farms increasingly distanced themselves from dairy work while those on small dairy farms continued their tradition role (Valenze Reference Valenze1991: 166).

Given the inverse relationship between farm size and married women’s engagement in farming activities, were the enumeration of “farmer’s wife” to faithfully record married women’s labor activities in farming, one would expect to find the enumeration rate of “farmer’s wife” decrease significantly with farm acreage.

Figure 2 shows the proportion of women married to farmers that were enumerated as “farmer’s wife” by farm size in the 1881 CEBs. The results go against the aforementioned hypothesis. The enumeration rate of “farmer’s wife” does not show any significant variations by farm size. It is remarkably similar between 40 and 50 percent across a wide range of farm sizes with increments of 20 acres.Footnote 17 This is yet the strongest evidence going against the argument that “farmer’s wife” in the CEBs captured married women’s work with their husband in farming. The question concerning the acreage thresholds between family farms and capitalist farms may never be settled. However, the detailed breakdown of farm acreage in figure 2 means that both types of farms must have been covered here. It shows that married women from large capitalist farms, which were run predominately by hired labor with almost no need for family labor, were just as likely to be enumerated as “farmer’s wife” as their counterparts from small family farms where married women were more directly and actively engaged in farming. For example, 42.5 percent of married women in farms smaller than 20 acres were enumerated as “farmer’s wife” in the 1881 CEBs. The corresponding figures for married women in farms larger than 400 acres was just 1 percent point lower. Allen finds that farmers on average had an annual income of £159.22 in 1867, which can be translated into 12 consumption baskets (Allen Reference Allen2019: 106). Farming families holding farms greater than 400 acres must surely have had an annual income much greater than that. Given the high levels of income, genteel status, and adherence to middle-class behavioral codes, it is hard to imagine married women from these large capitalist farms being directly involved in farming. The similar enumeration rates by farm size hint at a strong element of randomness involved in the enumeration of “farmer’s wife” as a result of the hitherto mentioned enumerators’ idiosyncrasies. It bears little, if any, indication of married women’s labor activities in farming.

Figure 2. Enumeration rate of “farmer’s wife” by farm size in England and Wales, 1881.

Table 6 can further support the aforementioned argument. It shows the enumeration rate of “farmer’s wife” by ED in 1861 CEBs.Footnote 18 In comparison with table 4, which concerns the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” in general, the effect of enumerators’ idiosyncrasies on the enumeration of “farmer’s wife” becomes even more apparent. Out of 10,418 EDs where “farmer’s wife” can be found, 3,537 enumerators, that is nearly 35 percent, had all women married to farmers in their EDs enumerated as “farmer’s wife.” The number of women enumerated as “farmer’s wife” from these EDs accounted for more than 40 percent of all married women enumerated as such in the country. This is clearly a case of the enumerators failing to distinguish between different groups of married women based on their actual labor activities. It is a serious overestimate of married women’s labor input into farming in these districts. By contrast, 10,147 EDs out of the total of about 20,000 EDs, which had married male farmers recorded, had no enumeration of “farmer’s wife” at all. Some married women from these EDs surely worked with their husband on the farms. The fact that none of them were enumerated as “farmer’s wife” constitutes a serious underestimate of married women’s labor activities in farming. It shows once again how enumerators’ idiosyncrasy can distort the picture of reality. The previous section suggests that the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” had little indication of married women’s labor in the form of working together with their husband for most occupations. This section shows that, even with regard to occupations that offered greater possibilities for married couples to work together, “occupation’s wife” still bears little indication of married women’s actual labor activities.

Table 6. Proportion of women who were married to farmers and enumerated as “farmer’s wife” in different type of Enumeration District in England and Wales, 1881

Sources: 1881 CEBs in I-CeM data set.

Caveats

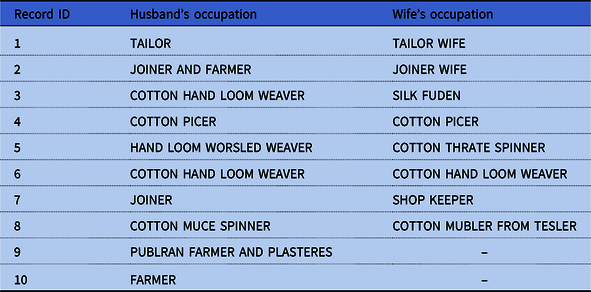

The task of finding the true meaning of “occupation’s wife” is complicated. The results presented in this article surely have caveats. First, the fact that “occupation’s wife” in the census failed to capture married women’s work with their husband does not mean such work did not exist. Many married women, in reality, undoubtedly worked with their husband in the same trade. However, we should not use “occupation’s wife” in the census to analyze such work. More suitable sources such as diaries and autobiographies should be consulted instead. Second, even though “occupation’s wife” in the census did not capture married women’s employment, could this term mean something else? The most obvious candidate is married women’s domestic function such as cooking, washing, and childrearing. It is difficult to ascertain this argument. Married women were almost always responsible for unpaid domestic labor in the nineteenth century. Those married women who were recorded as “occupation’s wife” were undoubtedly in charge of domestic chores. But so were those who were not recorded so. We should not use “occupation’s wife” as an exclusive indicator of whether married women were engaged in domestic duties or the intensity of their domestic duties. Third, for some married women, their occupational title of “occupation’s wife” could be a meaningful indicator of their work with husband in the same trade. Take part of one ED in the parish of Owthorne in Yorkshire in 1861 for example. Table 7 shows that, among 10 married couples in this area, two married women were enumerated as “occupation’s wife,” six married women were enumerated with independent occupational titles, and the remaining two had no occupational descriptors at all. The question then needs to be asked if those two married women in records 1 and 2 were not working with their husband, why did the enumerators just give them no occupational descriptor at all like records 9 and 10. In this case, deliberations were clearly being made by this enumerator as to whether married women were working or not and whether married women were working with their husbands or not. Unfortunately, it is beyond the scope of this article to identify all the EDs of this type and offer a detailed analysis.

Table 7. Husband and wife’s occupations in one Enumeration District in the parish of Owthorne in Yorkshire, 1861

Sources: 1861 CEBs from I-CeM data set.

Conclusion

This article delineates how “occupation’s wife” was tabulated in the published census reports and how “occupation’s wife” was enumerated in the CEBs. It argues that “occupation’s wife,” either in the published census reports or in the CEBs, in general had little indication of married women’s labor in the form of working with their husband in the same trade.

With regard to the published census reports, this article shows that, on one hand, “occupation’s wife” was not regarded as being part of the employment totals between 1881 and 1911, that is an extreme underestimation. On the other hand, the tabulation of “occupation’s wife” between 1851 and 1871 is likely to be an overestimation for certain occupations. Almost all women married to men in the occupations such as farmers and shoemakers were tabulated as “occupation’s wife” even if they were not recorded so in the original manuscripts, that is CEBs.

With regard to the CEBs, this article shows that almost all occupations had the corresponding enumeration of “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs, even if the occupations offered almost no opportunities for married couples to work together. It is also revealed that enumerators did not use this occupational title with careful deliberation to distinguish between married women who worked with husband and married women who did not. Some enumerators simply recorded all or almost all married women in their EDs as “occupation’s wife,” and at the same time, many enumerators recorded none of married women in their EDs as “occupation’s wife.” It suggests that the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” was heavily influenced by enumerators’ idiosyncrasy possibly as a result of Victorian domestic ideologies. Instead of showing married women’s employment, the enumeration of “occupation’s wife” in the CEBs was more indicative of the gender relationship in Victorian England and Wales. Its enumeration patterns suggest that many men were just more than willing to recognize married women solely through their supposed domestic position as someone’s wife. In that sense, “occupation’s wife” is more of a domestic title than an occupational title.

Married women’s nondomestic work could take many different forms. As shown in other studies, their regular gainful employment outside the home was, to some extent, faithfully recorded in the census (You Reference You2020). However, this type of employment does not make up the entirety of married women’s work. The work with husband in the same trade, among some married women, was likely to constitute a sizeable part of married women’s total labor input. However, the census was inadequate to shed much light on this issue. For this particular form of married women’s employment, alternative sources to the official statistics, such as diaries, autobiographies, and household budgets, must be consulted for a more accurate reassessment.

Acknowledgments

I thank the two anonymous referees whose comments improved the quality of this article. I would also like to thank Jeffrey Beemer for his editorial assistance. As a member of the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure, I have the privilege of having access to the data set created by the I-CeM project led by Kevin Schürer and Eddy Higgs (ESRC project grant number RES-062-23-1629), the Occupational Project led by Leigh Shaw-Taylor and Tony Wrigley (ESRC project grant number RES-000-23-1579), and the Entrepreneurship Project led by Bob Bennett (ESRC project grant number ES/M010953). This article would not have been possible without their data creation efforts. Kevin Schürer, Eddy Higgs, Amy Erickson, Auriane Terki-Mignot, and Leigh Shaw-Taylor read various drafts of this article. I thank them for their comments and suggestions. The usual disclaimers apply.