Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is present in 2–4% of adults and is characterised by symptoms of inattention, over activity and impulsiveness (McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Wilton, Murray, Hodgkins, Asherson and Wong2012). Features of ADHD emerge in childhood and symptoms persist into adulthood; 60% of adults have ongoing notable ADHD symptoms and 15–20% continue to meet the full diagnostic criteria (Agnew-Blais et al., Reference Agnew-Blais, Polanczyk, Danese, Wertz, Moffitt and Arseneault2016; Faraone, Biederman, & Mick, Reference Faraone, Biederman and Mick2006). There are psychiatric and social comorbidities associated with ADHD; adults with ADHD are at increased risk of impairments in education and academic performance, serious traffic accidents, criminality and physical and mental health problems (Dalsgaard, Ostergaard, Leckman, Mortensen, & Pedersen, Reference Dalsgaard, Ostergaard, Leckman, Mortensen and Pedersen2015; Ginsberg, Hirvikoski, & Lindefors, Reference Ginsberg, Hirvikoski and Lindefors2010; Ljung, Chen, Lichtenstein, & Larsson, Reference Ljung, Chen, Lichtenstein and Larsson2014; Shaw-Zirt, Popali-Lehane, Chaplin, & Bergman, Reference Shaw-Zirt, Popali-Lehane, Chaplin and Bergman2005; Spencer, Faraone, Tarko, McDermott, & Biederman, Reference Spencer, Faraone, Tarko, McDermott and Biederman2014). Pharmacological treatments are effective first-line treatments for ADHD (Cortese et al., Reference Cortese, Adamo, Del Giovane, Mohr-Jensen, Hayes, Carucci and Cipriani2018). However, up to half of patients discontinue medication within the first 3 years of treatment (Zetterqvist, Asherson, Halldner, Långström, & Larsson, Reference Zetterqvist, Asherson, Halldner, Långström and Larsson2013), with reported reasons being adverse effects and treatment ineffectiveness (Gajria et al., Reference Gajria, Lu, Sikirica, Greven, Zhong, Qin and Xie2014). Recent guidelines produced by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend that non-pharmacological treatment be used in combination with medication for adults who are still experiencing significant symptoms or for those who have made the informed choice not to start medication (NICE, 2018). Recent evidence notes that cognitive-behaviour-based treatments may be beneficial for adults with ADHD (Lopez et al., Reference Lopez, Torrente, Ciapponi, Lischinsky, Cetkovich-Bakmas, Rojas and Manes2018). However, other modalities of non-pharmacological treatment require further review, particularly whether improvements occur beyond the core symptoms of ADHD such as in social functioning (Davidson, Reference Davidson2008; Hodgson, Hutchinson, & Denson, Reference Hodgson, Hutchinson and Denson2014). This study aims to conduct a systematic review of the effectiveness of all non-pharmacological treatments for adult ADHD on improving the core behavioural ADHD symptoms, symptoms of functional impairment and comorbid conditions.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible studies included participants with ADHD or hyperkinetic disorder diagnosed according to the established diagnostic criteria (e.g. DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, DSM-5 or ICD-10); with participants all aged 18 years or over; and reported the results of a non-pharmacological intervention. Studies were excluded if the primary intervention was being used as a medicine, including dietary supplementation and homeopathy. All studies were required to use randomisation to allocate participants to either the intervention or a control condition. Control conditions included using a waiting list, treatment as usual (TAU), a pharmacological intervention, placebo or an alternative non-pharmacological intervention. Outcomes of interest were improvement in the core behavioural symptoms of ADHD (i.e. those outlined in DSM-III-R, DSM-IV or DSM-5), improvement in comorbid symptoms (e.g. anxiety and depression) and in symptoms of functional impairment (defined as problems in life domains such as work/education, family, life skills, social skills and/or risk-related behaviours). Neuropsychological, neurophysiological and neurobiological outcome measures were not examined since this was considered beyond the scope of this review and because behavioural rating scales are chiefly relied upon for the diagnosis and assessment of ADHD in routine clinical practice (NICE, 2018). Studies were also excluded if they were not available in English.

Search strategy

The following databases were searched in May 2018: PsycINFO, MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE, CINAHL and CENTRAL. Search strategies for all databases are available in online Supplementary Table S1. Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility by independent reviewers LS, SL and VN-S. In cases of uncertainties, the full articles were obtained and independently inspected, and inclusion criteria applied by the reviewers. Where meta-analysis or systematic reviews of treatment were available, we referred to the primary studies and assessed these for eligibility and reviewed the references of all included studies to identify any additional studies.

Data extraction, assessment of bias and data analysis

Data from the studies were extracted using a purpose-designed proforma (online Supplementary Table S2). The quality of studies was appraised using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Altman, Gotzsche, Juni, Moher and Oxman2011) and, where there was uncertainty, clarification was sought from a second reviewer. Where information was not known the corresponding author for the studies was contacted. It was decided a-priori to undertake a narrative synthesis of the data should an insufficient number of studies be identified, and/or the identified studies be at high risk of bias, and/or the identified studies appear highly heterogeneous in terms of methodology and study characteristics.

Results

Search results

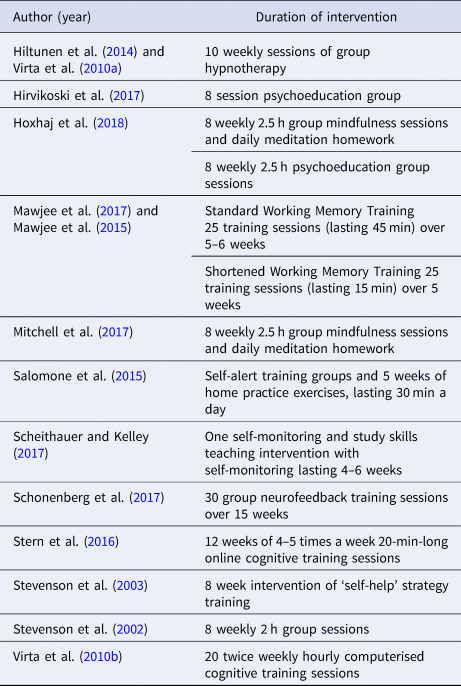

The results of the initial search, title and abstract screening, and selection of the final studies are presented in Fig. 1. The search string identified 55 865 articles, the majority of which were excluded following review of titles and abstracts. Of the 75 full-text records screened for eligibility, 32 met inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. Two papers reported differing outcomes of the same trial, with the later paper presenting additional functional outcomes (Young et al., Reference Young, Khondoker, Emilsson, Sigurdsson, Philipp-Wiegmann, Baldursson and Gudjonsson2015, Reference Young, Emilsson, Sigurdsson, Khondoker, Philipp-Wiegmann, Baldursson and Gudjonsson2017). Two papers reported the results of different comparison groups from within the same trial (Virta et al., Reference Virta, Salakari, Antila, Chydenius, Partinen, Kaski and Iivanainen2010a, Reference Virta, Salakari, Antila, Chydenius, Partinen, Kaski and Iivanainen2010b).

Fig. 1. Study flow diagram.

Risk of bias

Results of the risk of bias assessment are presented in Table 1. Only one of the included records was assessed as having a low risk of bias across all five domains and that was for only one of the interventions within the trial (Schonenberg et al., Reference Schonenberg, Wiedemann, Schneidt, Scheeff, Logemann, Keune and Hautzinger2017), and nine records were assessed as having a low risk of bias in four out of five domains (Dittner, Hodsoll, Rimes, Russell, & Chalder, Reference Dittner, Hodsoll, Rimes, Russell and Chalder2018; Gu, Xu, & Zhu, Reference Gu, Xu and Zhu2018; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Kan, Carpentier, Sizoo, Hepark, Schellekens and Speckens2018; Philipsen et al., Reference Philipsen, Jans, Graf, Matthies, Borel and Colla2015; Salomone et al., Reference Salomone, Fleming, Shanahan, Castorina, Bramham, O'Connell and Robertson2015; Stern, Malik, Pollak, Bonne, & Maeir, Reference Stern, Malik, Pollak, Bonne and Maeir2016; Vidal et al., Reference Vidal, Bosch, Nogueira, Gomez-Barros, Valero, Palomar and Ramos-Quiroga2013; Young et al., Reference Young, Khondoker, Emilsson, Sigurdsson, Philipp-Wiegmann, Baldursson and Gudjonsson2015, Reference Young, Emilsson, Sigurdsson, Khondoker, Philipp-Wiegmann, Baldursson and Gudjonsson2017). For a significant number of studies, it was not possible to assess the risk of bias in at least one of the five domains due to insufficient information.

Table 1. Risk of bias assessment for RCTs of non-pharmacological interventions for adult ADHD

a This refers to time T1 and T2 only as we cannot use time T3 as there is not a suitable control group.

Study characteristics

Study characteristics are presented in Table 2 (and results in online supplementary Table S3). The interventions fell into eight broad categories: (1) cognitive-behavioural therapy; (2) dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT); (3) mindfulness-based therapy; (4) hypnotherapy; (5) psychoeducation; (6) neurofeedback; (7) cognitive remediation and other forms of ‘brain training’ and (8) a study skill intervention. Studies were highly heterogeneous in terms of sample size, age range and gender of the participants and outcome measures. Due to this heterogeneity, and the aforementioned risk of bias, a narrative synthesis of results was used.

Table 2. Overview of non-pharmacological intervention sample characteristics, outcome measures and results

CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; DBT, dialectical behavioural therapy; MBCT, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; TAU, treatment as usual; WL, waiting list.

Narrative synthesis

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

There were 14 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of CBT and one additional study presenting outcomes of further results from an earlier study (Young et al., Reference Young, Emilsson, Sigurdsson, Khondoker, Philipp-Wiegmann, Baldursson and Gudjonsson2017). Details of CBT interventions are given in Table 3 and online supplementary Table S4. None of the CBT studies were assessed as having a low risk of bias across all five domains and there was substantial variation in sample size across studies.

Table 3. Duration and details of cognitive behavioural-based interventions and DBT

Five studies compared CBT with TAU (Dittner et al., Reference Dittner, Hodsoll, Rimes, Russell and Chalder2018; Emilsson et al., Reference Emilsson, Gudjonsson, Sigurdsson, Baldursson, Einarsson, Olafsdottir and Young2011; Safren et al., Reference Safren, Otto, Sprich, Winett, Wilens and Biederman2005; Young et al., Reference Young, Khondoker, Emilsson, Sigurdsson, Philipp-Wiegmann, Baldursson and Gudjonsson2015, Reference Young, Emilsson, Sigurdsson, Khondoker, Philipp-Wiegmann, Baldursson and Gudjonsson2017) CBT produced an improvement in independent and self-reported ADHD symptoms, both for group (Emilsson et al., Reference Emilsson, Gudjonsson, Sigurdsson, Baldursson, Einarsson, Olafsdottir and Young2011; Young et al., Reference Young, Khondoker, Emilsson, Sigurdsson, Philipp-Wiegmann, Baldursson and Gudjonsson2015) and individual (Dittner et al., Reference Dittner, Hodsoll, Rimes, Russell and Chalder2018; Safren et al., Reference Safren, Otto, Sprich, Winett, Wilens and Biederman2005) therapy. Improvements included changes in inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms and were based on measures taken at pre- and post-treatment and at follow-up. Three studies also reported lower Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scores following CBT (Dittner et al., Reference Dittner, Hodsoll, Rimes, Russell and Chalder2018; Safren et al., Reference Safren, Otto, Sprich, Winett, Wilens and Biederman2005; Young et al., Reference Young, Khondoker, Emilsson, Sigurdsson, Philipp-Wiegmann, Baldursson and Gudjonsson2015). These results indicate a favourable effect of CBT compared with TAU. However, all studies had a high risk of bias associated with blinding as participants in the treatment arms received more attention than controls.

Three studies compared CBT with a form of generic counselling. The studies ranged in sample size from 32 (Vidal et al., Reference Vidal, Bosch, Nogueira, Gomez-Barros, Valero, Palomar and Ramos-Quiroga2013) to 433 (Philipsen et al., Reference Philipsen, Jans, Graf, Matthies, Borel and Colla2015). In two studies, both CBT and counselling were associated with improvements in ADHD symptoms; however, there was no evidence that CBT led to greater improvements in either informant or self-reported ADHD (Philipsen et al., Reference Philipsen, Jans, Graf, Matthies, Borel and Colla2015; Vidal et al., Reference Vidal, Bosch, Nogueira, Gomez-Barros, Valero, Palomar and Ramos-Quiroga2013) and only one study found CBT improved CGI scores (Philipsen et al., Reference Philipsen, Jans, Graf, Matthies, Borel and Colla2015). The largest study was Philipsen et al. (n = 433); however, it is limited by comparing group CBT with individual supportive clinical management and so arguably the control group received a more intensive treatment (Philipsen et al., Reference Philipsen, Jans, Graf, Matthies, Borel and Colla2015). In addition to this, the programme manual followed in this study had more similarities with the DBT treatment described in a later study than other CBT studies (Table 3 and online supplementary Table S4) (Hesslinger, Philipsen, & Richter, Reference Hesslinger, Philipsen and Richter2004; Hirvikoski et al., Reference Hirvikoski, Waaler, Alfredsson, Pihlgren, Holmstrom, Johnson and Nordstrom2011).

One study examined the impact of CBT on a ‘younger’ (aged under 50) and ‘older’ (aged 50 or older) group of patients with ADHD (Solanto, Surman, & Alvir, Reference Solanto, Surman and Alvir2018). This found improvements in ADHD symptoms on both independent and self-reported measures in the ‘younger’ group, but not the ‘older’ group.

One study compared CBT with relaxation training (Safren et al., Reference Safren, Sprich, Mimiaga, Surman, Knouse, Groves and Otto2010). CBT was associated with greater improvements in independent ratings of ADHD symptoms and in clinician-rated CGI scores. CBT also led to quicker improvements in self-reported ADHD symptoms. Improvements were maintained at 6- and 12-month follow-up. Two studies explored the use of internet-delivered CBT v. a waiting list control (Moëll, Kollberg, Nasri, Lindefors, & Kaldo, Reference Moëll, Kollberg, Nasri, Lindefors and Kaldo2015; Pettersson, Sostrom, Edlund-Soderstrom, & Nilsson, Reference Pettersson, Sostrom, Edlund-Soderstrom and Nilsson2017). Both studies found that CBT was associated with significant improvements in self-reported ADHD symptoms.

Two studies examined meta-cognitive therapy, a form of CBT based on improving executive functioning skills. Group meta-cognitive therapy was associated with greater changes in clinician and informant ratings of inattentive ADHD symptoms and clinician ratings of time-management, organisation and planning skills when compared with group supportive therapy, although both CBT and supportive therapy were associated with changes in ADHD symptoms rated using the Brown Attention Deficit Disorder Scale (Solanto et al., Reference Solanto, Marks, Wasserstein, Mitchell, Abikoff, Alvir and Kofman2010). One study compared individual meta-cognitive therapy with neurofeedback and sham neurofeedback, and found no significant difference between treatment groups for changes in self-reported ADHD symptoms (Schonenberg et al., Reference Schonenberg, Wiedemann, Schneidt, Scheeff, Logemann, Keune and Hautzinger2017).

Two studies used the same sample to compare CBT with cognitive training, hypnotherapy and a control condition (Hiltunen et al., Reference Hiltunen, Virta, Salakari, Antila, Chydenius, Kaski and Partinen2014; Virta et al., Reference Virta, Salakari, Antila, Chydenius, Partinen, Kaski and Iivanainen2010b). CBT was associated with an improvement in one informant-rated measure of ADHD symptoms when compared with the control condition (Virta et al., Reference Virta, Salakari, Antila, Chydenius, Partinen, Kaski and Iivanainen2010b). There were no differences between CBT and cognitive training based on informant or self-reported ADHD symptoms but CBT was associated with lower CGI scores. Compared with hypnotherapy, CBT produced no significantly different changes in informant or self-reported ADHD symptoms or CGI scores post-treatment. However, at follow-up, hypnotherapy but not CBT was associated with a change in informant ratings of ADHD (Hiltunen et al., Reference Hiltunen, Virta, Salakari, Antila, Chydenius, Kaski and Partinen2014). These studies were particularly small with 10 or less individuals in each treatment group.

Dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT)

Two RCTs assessed group DBT. Details are presented in Table 3 and online supplementary Table S4. One (Hirvikoski et al., Reference Hirvikoski, Waaler, Alfredsson, Pihlgren, Holmstrom, Johnson and Nordstrom2011) compared 14 sessions of DBT with a discussion group. DBT, but not the discussion group, was associated with a significant reduction in self-ratings of ADHD symptoms; however, this difference was attenuated to a non-significant level when an intention-to-treat analysis was performed. This study was associated with a low risk of bias. The second study (Fleming, McMahon, Moran, Peterson, & Dreessen, Reference Fleming, McMahon, Moran, Peterson and Dreessen2015) compared DBT with self-help and was associated with a higher risk of bias. Those who received DBT performed significantly better on measures of the clinical impact of executive functioning deficits after treatment and at 3-month follow-up; however there was no significant effect of the intervention on self-rated symptoms of inattention.

Mindfulness-based interventions

Four studies examined mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), an intervention that combines elements of mindfulness training with CBT, while two additional studies examined mindfulness interventions. These studies varied in terms of sample size and risk of bias, with none rated as low risk of bias for the blinding of participants. Details are presented in Table 4 and online supplement Table S5.

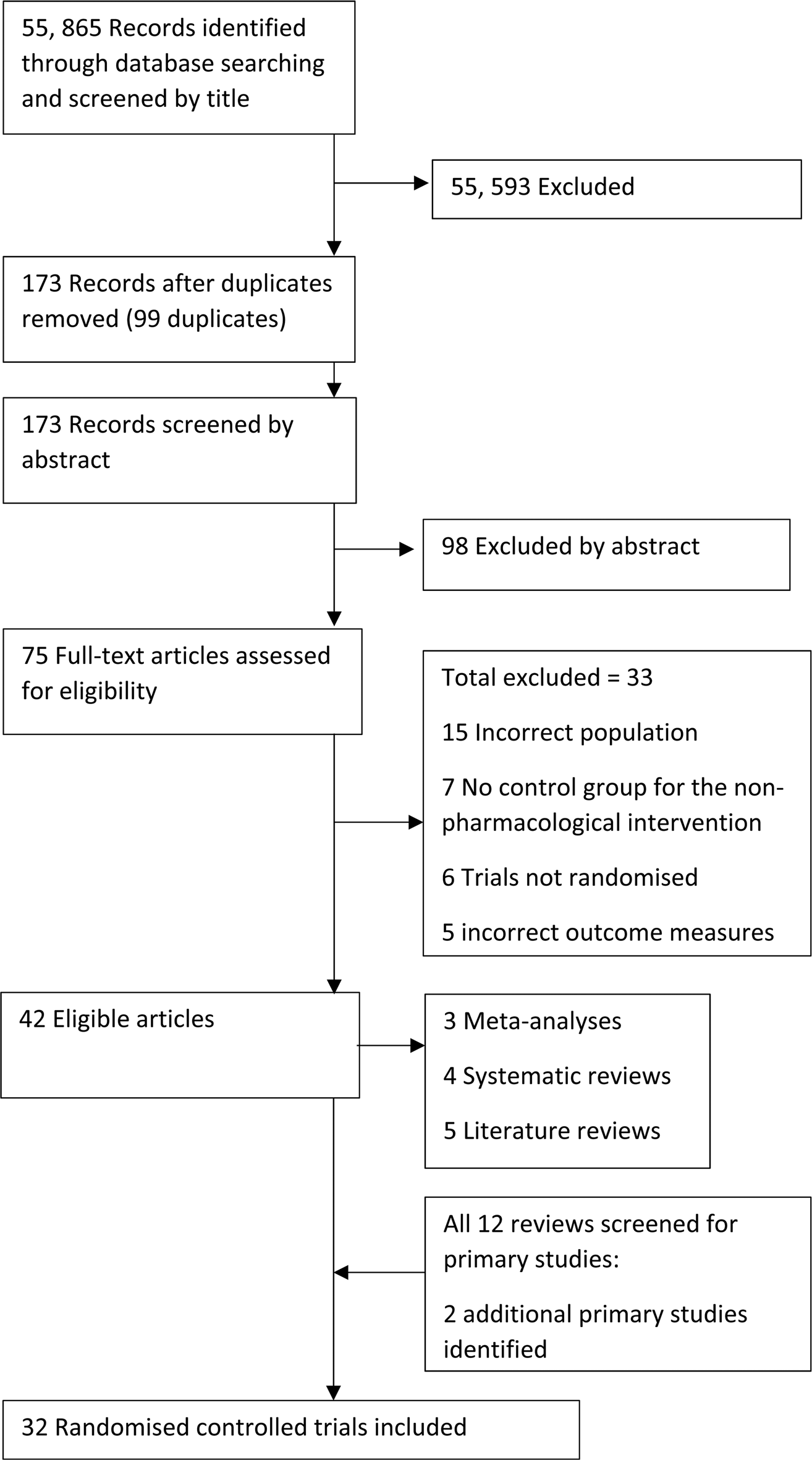

Table 4. Duration and details of all other interventions

Compared with TAU, group MBCT was associated with a significant improvement in post-treatment observer and self-reported ADHD symptoms and with improved behavioural ratings of executive functioning at 3- and 6-month follow-up but not immediately after treatment (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Kan, Carpentier, Sizoo, Hepark, Schellekens and Speckens2018). Two further studies, which compared group MBCT with a waiting list control, found significant improvements in ADHD symptoms post treatment for self-reported (Hepark et al., Reference Hepark, Janssen, de Vries, Schoenberg, Donders, Kan and Speckens2019; Schoenberg et al., Reference Schoenberg, Hepark, Kan, Barendregt, Buitelaar and Speckens2014) and observer-reported (Hepark et al., Reference Hepark, Janssen, de Vries, Schoenberg, Donders, Kan and Speckens2019) ADHD symptoms immediately after the intervention but did not collect follow-up data. A fourth study compared individual MBCT with a waiting list control and found an improvement in self-reported ADHD symptoms at post-treatment and at follow-up (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Xu and Zhu2018).

Compared with an active control of group psychoeducation, group mindfulness did not produce a significant improvement in observer or self-reported ADHD symptoms either post-treatment or at 6-month follow-up (Hoxhaj et al., Reference Hoxhaj, Sadohara, Borel, D'Amelio, Sobanski, Muller and Philipsen2018). However, it was noted that both interventions appeared to improve outcomes. A smaller study found that group mindfulness sessions produced a significant improvement in self- and observer-reported ADHD symptoms, however this was v. a waiting list control and had had high risk of bias (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, McIntyre, English, Dennis, Beckham and Kollins2017).

Hypnotherapy

Hypnotherapy as a treatment for ADHD has been studied in two small RCTs, both of which were associated with a high risk of bias. Details are provided in Table 4 and online supplementary Table S5. One study compared hypnotherapy with CBT, the results of which are described above (Hiltunen et al., Reference Hiltunen, Virta, Salakari, Antila, Chydenius, Kaski and Partinen2014). Another study (Virta et al., Reference Virta, Salakari, Antila, Chydenius, Partinen, Kaski and Iivanainen2010a) compared the same participants with those receiving no intervention, finding that those in the ADHD group scored significantly lower for self-reported total ADHD scores and some subscales of the BADDS scale; however, there was no significant improvement in ADHD symptoms over time based on aggregate self and informant ratings of ADHD.

Psychoeducation

Group psychoeducation was measured as the primary intervention v. a TAU control in one study by Hirvikoski et al. (n = 87) and in comparison with MBCT by Hoxhaj et al. (n = 81). Both studies had a low risk of bias in three out of the five domains. Hirvikoski et al. assessed the feasibility and effectiveness of a group-based psychoeducation programme for people with ADHD and their significant others (Hirvikoski et al., Reference Hirvikoski, Lindstrom, Carlsson, Waaler, Jokinen and Bolte2017). ADHD behavioural symptoms were not measured and no significant differences were found in secondary outcomes of functional impairment (reported in online supplementary Table S3). Hoxhaj et al. found no difference between the psychoeducation group and mindfulness group in observer or self-reported ADHD symptoms (see above) (Hoxhaj et al., Reference Hoxhaj, Sadohara, Borel, D'Amelio, Sobanski, Muller and Philipsen2018).

Neurofeedback

One RCT compared neurofeedback with both sham neurofeedback and meta-cognitive therapy as control interventions (Schonenberg et al., Reference Schonenberg, Wiedemann, Schneidt, Scheeff, Logemann, Keune and Hautzinger2017). This study was assessed as low risk of bias in all five domains, as the sham neurofeedback provided an effective control condition. There were no significant differences between neurofeedback, sham neurofeedback and metacognitive therapy for improvement in ADHD symptoms after treatment or at 6-month follow-up.

Cognitive remediation and rehabilitation

Seven studies sought to improve both the behavioural symptoms and the neurocognitive functioning of people with ADHD using methods such as cognitive remediation, rehabilitation or another form of ‘brain training’. Details of these interventions are given in Table 4 and online supplementary Table S5. Two studies examined therapist-delivered (Stevenson, Whitmont, Bornholt, Livesey, & Stevenson, Reference Stevenson, Whitmont, Bornholt, Livesey and Stevenson2002) and self-directed (Stevenson, Stevenson, & Whitmont, Reference Stevenson, Stevenson and Whitmont2003) cognitive remediation. Four studies examined computerised cognitive training (Mawjee et al., Reference Mawjee, Woltering, Lai, Gotlieb, Kronitz and Tannock2017; Mawjee, Woltering, & Tannock, Reference Mawjee, Woltering and Tannock2015; Stern et al., Reference Stern, Malik, Pollak, Bonne and Maeir2016; Virta et al., Reference Virta, Salakari, Antila, Chydenius, Partinen, Kaski and Iivanainen2010b), with two focussing on working memory training (Mawjee et al., Reference Mawjee, Woltering and Tannock2015, Reference Mawjee, Woltering, Lai, Gotlieb, Kronitz and Tannock2017). Finally, one study examined self-alert training (Salomone et al., Reference Salomone, Fleming, Shanahan, Castorina, Bramham, O'Connell and Robertson2015). Only two of the studies were assessed as having low risk of bias in only one of the five domains (Salomone et al., Reference Salomone, Fleming, Shanahan, Castorina, Bramham, O'Connell and Robertson2015; Stern et al., Reference Stern, Malik, Pollak, Bonne and Maeir2016), with the remainder having a high risk of bias or unknown risk of bias in at least two domains.

Therapist delivered cognitive remediation produced a significant improvement in ADHD symptoms and in organisation skills, which were maintained at 2- and 12-month follow-up. These findings remained after controlling for ADHD medication (Stevenson et al., Reference Stevenson, Whitmont, Bornholt, Livesey and Stevenson2002). Self-directed cognitive remediation augmented with three therapist-led sessions also significantly improved ADHD symptoms and organisation post-intervention and at 2-month follow-up (Stevenson et al., Reference Stevenson, Stevenson and Whitmont2003).

Two studies of working memory training consisting of standard (45 min of daily training), or a shortened (15 min training), found no significant improvement in measures of ADHD symptoms or self-reported measures of deficits in executive function with either form of working memory training v. a waiting list control (Mawjee et al., Reference Mawjee, Woltering and Tannock2015, Reference Mawjee, Woltering, Lai, Gotlieb, Kronitz and Tannock2017). However Mawjee et al. (Reference Mawjee, Woltering, Lai, Gotlieb, Kronitz and Tannock2017) found on post-hoc analysis that although self-reported symptoms of cognitive failures did not differ between shortened and standard length training and the control group, there was a significant difference when both forms of working memory training were compared together against the control. This study had limited power due to having a small sample size (n = 38).

The study comparing cognitive training v. a CBT and control group in a group of 32 individuals has been described above, noting that there was no significant difference in improvement in ADHD symptoms (Virta et al., Reference Virta, Salakari, Antila, Chydenius, Partinen, Kaski and Iivanainen2010b). A larger study of 60 individuals comparing computerised cognitive training v. a control condition of generic exercises found no difference between the intervention and control on improvement in ADHD symptoms (Stern et al., Reference Stern, Malik, Pollak, Bonne and Maeir2016).

Self-alert training using biofeedback scored significantly lower post-intervention and at 3-month follow-up for symptoms of inattention, impulsivity and emotional lability, for problems with self-concept, and for the ADHD index score compared with a control condition which used all aspects of the treatment except for the use of biofeedback (Salomone et al., Reference Salomone, Fleming, Shanahan, Castorina, Bramham, O'Connell and Robertson2015). In contrast, there were no significant group differences for scores on the attention and memory problems scale, the hyperactivity and restlessness scale, the DSM-IV hyperactive symptoms scale or the DSM-IV total symptoms scale. There was evidence of a treatment dose–response effect, whereby longer self-alert training practice was associated with greater reductions in inattentive symptoms of ADHD, but not to changes in other ADHD symptom domains. Participants in the training group reported significantly lower ratings for attentional slips than controls, but with no group differences for lapses in memory.

Study skills intervention and self-monitoring

There was one study which specifically explored a ‘study skills intervention’ compared with a control condition (Scheithauer & Kelley, Reference Scheithauer and Kelley2017). The details of this are described in more detail in Table 4 and online supplementary Table S5. Significantly more individuals in the self-monitoring group v. the control group demonstrated clinical improvements in self-reported symptoms of ADHD. However, this study was noted to be of high-risk for bias.

Functional impairment

Symptoms of psychiatric comorbidity and/or functional impairment were also examined in this review, with results summarised in online supplementary Table S3. In summary, of the 14 CBT studies (including one follow-up study) measuring comorbidity or functional outcomes, six found a positive result for CBT in at least one measure of these outcomes (Dittner et al., Reference Dittner, Hodsoll, Rimes, Russell and Chalder2018; Emilsson et al., Reference Emilsson, Gudjonsson, Sigurdsson, Baldursson, Einarsson, Olafsdottir and Young2011; Moëll et al., Reference Moëll, Kollberg, Nasri, Lindefors and Kaldo2015; Safren et al., Reference Safren, Otto, Sprich, Winett, Wilens and Biederman2005; Young et al., Reference Young, Khondoker, Emilsson, Sigurdsson, Philipp-Wiegmann, Baldursson and Gudjonsson2015, Reference Young, Emilsson, Sigurdsson, Khondoker, Philipp-Wiegmann, Baldursson and Gudjonsson2017). One of the two DBT studies and one of the two hypnotherapy studies measuring comorbidity or functional outcomes found a significantly improved outcome in at least one measure favouring the intervention (Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, McMahon, Moran, Peterson and Dreessen2015; Hiltunen et al., Reference Hiltunen, Virta, Salakari, Antila, Chydenius, Kaski and Partinen2014). None of the studies of psychoeducation or neurofeedback found a significant difference for measures of these outcomes. Seven of the cognitive remediation studies measured comorbidity and/or functional impairment, with four finding a statistically significant result in at least one measure (Mawjee et al., Reference Mawjee, Woltering, Lai, Gotlieb, Kronitz and Tannock2017; Salomone et al., Reference Salomone, Fleming, Shanahan, Castorina, Bramham, O'Connell and Robertson2015; Stevenson et al., Reference Stevenson, Whitmont, Bornholt, Livesey and Stevenson2002, Reference Stevenson, Stevenson and Whitmont2003). Self-monitoring was associated with significantly improved functional outcomes relating to academic studies (Scheithauer & Kelley, Reference Scheithauer and Kelley2017). Four of the six mindfulness-based intervention studies found significant improvements in measures of comorbidity, favouring the intervention, but none of the studies found significant improvements in functional outcomes (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Xu and Zhu2018; Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Kan, Carpentier, Sizoo, Hepark, Schellekens and Speckens2018; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, McIntyre, English, Dennis, Beckham and Kollins2017; Schoenberg et al., Reference Schoenberg, Hepark, Kan, Barendregt, Buitelaar and Speckens2014).

Discussion

This systematic review examined the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for adult ADHD. These studies used a wide range of outcome measures and most of the identified studies were small (<60 randomised participants) and at a high risk of bias, with marked heterogeneity in terms of study design and delivery of the intervention. A meta-analysis was therefore considered inappropriate and these limitations impact on the extent to which firm conclusions can be drawn.

The results across studies suggest that non-pharmacological interventions perform significantly better than inactive control conditions when used to manage the core behavioural symptoms of ADHD. Studies with an active control condition gave more mixed results as often there was a significant within-group improvement in the control condition, which could be due to placebo effect or another aspect of the control condition providing an active treatment element, such as increasing patient knowledge, and motivation for engagement (Hoxhaj et al., Reference Hoxhaj, Sadohara, Borel, D'Amelio, Sobanski, Muller and Philipsen2018; Vidal et al., Reference Vidal, Bosch, Nogueira, Gomez-Barros, Valero, Palomar and Ramos-Quiroga2013), or through task demands such as practicing sustaining focus (Schonenberg et al., Reference Schonenberg, Wiedemann, Schneidt, Scheeff, Logemann, Keune and Hautzinger2017), or through providing a therapeutic relationship (Philipsen et al., Reference Philipsen, Jans, Graf, Matthies, Borel and Colla2015). Nonetheless, these findings suggest that non-pharmacological interventions can play an important role in helping adults diagnosed with ADHD to manage their condition.

By far, the greatest number of studies (n = 14) examined CBT. The results of these studies broadly suggest that CBT is associated with a reduction in the core behavioural symptoms of ADHD and can be delivered as either a group, individual or internet-based form of therapy. However, there was marked heterogeneity across studies, both in terms of sample size, study design and quality, and in terms of the kind of change in ADHD symptoms identified. For example, some studies found a reduction in informant but not self-reported ADHD symptoms and vice-versa; some identified lasting change in ADHD symptoms based on follow-up data but not immediately after the intervention and some studies failed to find any benefit of CBT over and above an active control condition. Further research into CBT interventions is therefore required, including studies that seek to replicate the promising results identified thus far.

Some other interventions also showed promise, in particular cognitive remediation and rehabilitation, mindfulness-based therapies and to some extent DBT and hypnotherapy. Both MBCT and DBT are similar to CBT in that they support people to change their behaviours, and indeed there are many parallels across all of the different classes of intervention identified in this study. However, MBCT and DBT are considered ‘third-wave’ cognitive and behavioural therapies and differ from traditional CBT in that they help individuals to change the relationship with their thoughts as opposed to directly challenging the content of thoughts (Hayes & Hofmann, Reference Hayes and Hofmann2017). MBCT and DBT both also teach mindful awareness as a therapeutic technique, which involves gently redirecting attention to the present moment when it wanders. It is possible that this acts as a form of brain training, highlighting parallels between these interventions and cognitive remediation therapy, which also involves attention training and was associated with a reduction in the core symptoms of ADHD.

Symptoms of functional impairment and comorbidity were also examined in this review. There was a wide variation in results, with the most consistent effect of therapy being the impact of mindfulness-based therapies on psychiatric comorbidity, which is consistent with the use of mindfulness-based therapies on treating anxiety and depression (Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, & Oh, Reference Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt and Oh2010). Whilst studies reporting on comorbidity and functional outcomes were likely to be powered primarily to detect a change in behavioural symptoms of ADHD and not to detect changes in comorbidity, there is the potential for non-pharmacological interventions to improve quality of life for adults with ADHD in a much broader sense, and this is an area that should be explored further in future research.

There were a wide number of measures used for ADHD symptoms, comorbidity and functional impairment. This contributed to the heterogeneity of the results and difficulty in making comparisons between treatment approaches. Because of this, it seems important to recommend that future research takes a systematic approach. First, a set of core outcome measures could be established, including both observer and self-reported ratings of ADHD symptoms in accordance with diagnostic criteria. A set of core outcome measures could include measures of psychological distress, such as Beck's inventories for anxiety and depression (Beck & Steer, Reference Beck and Steer1990; Beck, Steer, & Brown, Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996) and a scale of functional impairment such as the adult attention-deficit hyperactive disorder quality-of-life scale (AAQOL scale) (Brod, Johnston, Able, & Swindle, Reference Brod, Johnston, Able and Swindle2006). Importantly, these should be developed in consultation with the adult ADHD community in order to ensure that ‘real life’ outcomes that matter to individuals are included in future trials.

Second, where there have been studies of non-pharmacological interventions that have shown promise, we need larger, better designed trials. Trials with a low risk of bias should ensure that allocation concealment occurs and that outcomes are assessed by independent, blinded assessors. Trials should aim to be powered to detect not only effects of treatment on the behavioural symptoms of ADHD, but also symptoms of comorbidity. Trials should also directly compare non-pharmacological interventions for ADHD with pharmacotherapy. This form of comparison was rarely undertaken, yet the right of adults with ADHD to make an informed choice about interventions sits at the heart of patient-centred care. One large study included in this review did compare non-pharmacological interventions with medication and in doing so found that methylphenidate had the greatest effect on ADHD regardless of the non-pharmacological intervention used (Philipsen et al., Reference Philipsen, Jans, Graf, Matthies, Borel and Colla2015).

Third, and to help identify the ‘active ingredients’ of treatment, studies could begin to look at mediating variables to find out what leads to a change in symptoms following non-pharmacological treatment. In CBT, for example, it is not clear whether psycho-education, problem-solving, cognitive restructuring, behavioural change or a combination thereof, leads directly or indirectly to a change in ADHD or comorbid symptoms. Mediators may also include neurobiological, neurophysiological or neuropsychological performance, particularly as these variables are considered to be ‘endophenotypes’ of ADHD (Castellanos & Tannock, Reference Castellanos and Tannock2002) that may bridge the gap between genes and behaviours.

This review should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, the review was not pre-registered. Second, although much effort was made to retrieve a maximum number of relevant studies, we cannot rule out the possibility that we have missed some relevant studies. For example, we only included published papers and did not search the grey literature. We also focused on English-language publications due to resource limitations. This could have possibly introduced a cultural bias in terms of the kinds of interventions reported and may limit the extent to which findings generalise to different countries and cultures. Third, due to heterogeneity and risk of bias across the identified studies, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis; therefore, the effect sizes across different studies were not examined. This makes it difficult to draw any direct comparisons between the different classes of intervention. Finally, many of the interventions described take similar approaches, meaning that the different classes of intervention have much in common.

Despite these limitations, this review serves as a bellwether, identifying the state of research into non-pharmacological interventions for adult ADHD and highlighting their potential in clinical practice, and identifying gaps in the evidence with suggestions about the direction of future research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720000069

Author contributions

JB, DH, RG, VP, LS, SL and DR contributed to the conception and design of this project, to interpretation and comments on revised drafts of this article and final approval of this article; LS, SL and VN-S conducted the literature search and data extraction; AM and VN-S contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results, the writing of the first draft and subsequent drafts of this article and final approval of this article.

Financial support

This work was supported by Research Capability Funding (NIHR-RCF) provided by Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Trust and Victoria Nimmo-Smith was funded by a National Institute for Health Research Academic Clinical Fellowship award (reference number ACF-2016-25-503). This study was also supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol (BRC-1215-2011).

Conflict of interest

VN-S, AM, JB, RG, LS, SL, VP and DR have nothing to declare.

DH has been sponsored to attend educational events by several pharmaceutical companies. He has been a paid speaker at events organised by Flynn Pharma, Janssen Cilag and Shire Pharmaceuticals.