Introduction

The relationship between the central government and local literati is a vital issue in pre-modern Chinese history. On the one hand, local literati or local elites could become agents of a regime by participating in dynastic recruitment systems; on the other hand, depending on their personal views or positions in a certain region, they could choose to remain spokesmen for local interests.Footnote 1 The actions of the literati are often a key factor in assessing the overall direction of centrifugal or centripetal forces between a given locale and the central authorities. Did the literati of a certain place involve themselves in local affairs because they were uninterested in pursuing a political career in the central court, or did their active careers as state bureaucrats cause them to lose their roots in their places of origin? Or did their shuttling between the center and the local regions foster a closer relationship between the state and their localities? Any of these possibilities will lead to changes in the relationship between a given region and the central government.

Existing research on the relationship between the central government and local literati during the “Tang–Song transition” is sufficient to outline a general trend.Footnote 2 In the ninth century, capital-based elites held both court offices and high-ranking positions in local government, while provincial elites served only in lower-level local positions.Footnote 3 This indicates that in the Tang, provincial elites had difficulty securing positions at court, and thus the connection and communication between the central government and local areas were relatively weak. However, after the decline of the capital-based elite at the end of the Tang, this situation underwent significant change during the Song dynasty. Established scholarship has noted that literati from various regions actively sought official positions in the central government.Footnote 4 The expanded Song imperial examination system was key to facilitating this change. In short, the relative detachment between the center and the local areas in the Tang shifted in the Song to a scenario in which local literati sought and successfully achieved promotion in the central government.

If this shift indeed occurred as part of the Tang–Song transition, can we assume that the demise of capital-based elites inevitably led to a rise of elites with local roots? Or were there significant developments that prompted the central government to more consciously seek cooperation with local elites? This is especially important considering the complex Interregnum period between 878 and 978, the middle period of the Tang–Song transition and the only period in Chinese history when multiple regimes co-existed in the south. The Tang–Song Interregnum extended well beyond the five decades labeled as Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907–960).Footnote 5 During the Interregnum, China experienced a century-long political structure of “Central Plains-Southern Kingdoms” rule, in which the authority of the Central Plains regimes over the South went through a process of being challenged, denied, and finally rebuilt. Different southern regimes maintained different relationships with the Central Plains regimes, courting or opposing them,Footnote 6 and the literati had to deal both with the government of the Central Plains and also with the local regimes to which they belonged.

The case of Fujian deserves closer attention as a border area during the Interregnum. In the early Tang, Fujian was a backward place in terms of literati culture, but established studies have shown that after the mid-Tang, Fujian literati were remarkably successful in the civil service examinations. Using the connections they built with intellectuals at the central level, they fostered scholarly exchanges between the central government and Fujian.Footnote 7 Even more striking is the fact that Jianzhou 建州, Fuzhou 福州, and Xinghua Military Prefecture 興化軍 in Fujian ranked first, second, and fourth respectively in jinshi degree holders in the Northern Song.Footnote 8 This advantage became quite evident even at the early stage of the Northern Song, indicating that a large number of local literati in these areas aspired to join the regime and succeeded in doing so in the beginning of the Song dynasty.Footnote 9 Clearly, between the mid-Tang and the early Northern Song, the Fujian literati community underwent an impressive development.

However, since independent regimes existed in Fujian during the Interregnum, one cannot assume that the initial Song rule over Fujian was necessarily smooth. During the Huang Chao Rebellion (875–884), when massive uprisings caused extensive destruction to the Tang Empire from the capital to the south,Footnote 10 three brothers, Wang Chao 王潮 (846–898), Wang Shengui 王審邽 (858–904), and Wang Shenzhi 王審知 (862–925) from Gushi 固始 in Guangzhou 光州 joined Wang Xu’s 王緒 army and entered Fujian in 885. By 893 the three brothers had occupied all of Fujian. The Min kingdom (Minguo 閩國) was then established in 909 under the rule of Wang Shenzhi. After Wang Shenzhi’s death, his sons and grandsons fought fierce civil wars for power, and each sought military assistance from the Southern Tang 南唐 and Wu-Yue 吳越 kingdoms, resulting in the division of Fujian between three powers: the Southern Tang occupied Jianzhou and Tingzhou 汀州; Wu Yue occupied Fuzhou; and the warlord Liu Congxiao 留從效 (906–962) occupied Quanzhou 泉州 and Zhangzhou 漳州. During the reign of Song Taizu 宋太祖 (r. 960–976) and Song Taizong 宋太宗 (r. 976–997), the Song state conquered the south and established direct rule over Fujian in 978 (see Table 1).Footnote 11 This article will refer to the period from 885 to 925, when Wang Shenzhi passed away, as “the early Interregnum,” and the subsequent period ending in 978 as “the late Interregnum.”

Table 1. Timeline of the Central Plains and Fujian Regimes during the Interregnum

If the trend from the mid-Tang to the Northern Song saw more and more Fujian literati forming ties with Central Plains regimes, what role did Fujian’s local regimes play during the Interregnum? Why did the independent regimes of Fujian in the Interregnum fail to reverse or stem the increasingly close ties between Fujian and the Central Plains? Given that the Song dynasty emerged after the south had been divided into many independent regimes for a century, we cannot assume that after the unification of the empire (or the Song annexation of the south), all southern literati would willingly and unconditionally accept the new regime.

This article takes Puyang 莆陽 in Fujian as an example to explore the subtle relationship between local literati and the Central Plains regimes during the Interregnum. In the Tang dynasty, Puyang referred to Putian 莆田 County of Quanzhou. In the early Song, the three counties of Putian, Xianyou 仙遊, and Xinghua 興化, were merged into Xinghua Military Prefecture, which was then collectively known as Puyang. With mountains to its west, Puyang consisted of coastal plains that were formed after millennia of alluvial flooding. The development of settlements on the plains was thus closely related to construction projects involving water conservation. Since the mid-Tang, people had excavated ponds to store water, allowing more and more settlements to form.Footnote 12

To study the relationship between a small region in the south and the Central Plains regimes in or before the Northern Song, one often encounters the problem of insufficient historical materials. However, two literati in Fujian during the Tang left behind their collected works: Ouyang Zhan 歐陽詹 (758–801), a Quanzhou native, and Huang Tao 黃滔 (860–911), a Putian native. Although Ouyang was not from Puyang, he studied there with other Puyang literati. In addition, a few local inscriptions dating from the beginning of the Northern Song are extant. When supplemented by other historical sources, such as the Zizhi tongjian 資治通鑑 and excavated tomb inscriptions, it is possible to reconstruct the local activities and local narratives of Puyang literati and their relationship with the Central Plains regimes during the Interregnum. By analyzing how the local discourses of the Puyang literati were embedded in dramatically changing political and social contexts, this article explores the complex processes by which an imperial borderland linked itself to the Central Plains regime.

Puyang literati political and social networks in the early Interregnum

This section first analyzes how the three Wang brothers endeavored in the late Tang to establish a regime in Fujian. It then shows how Puyang literati proved their importance to these local rulers by bridging the Min regime with the Tang government. The discussion in this section will illustrate that despite the weakened control of the Tang central government over the south after the Huang Chao Rebellion, the crucial role played by local literati enabled the Tang to maintain governance over Fujian.

The Wang brothers’ multiple strategies to rule Fujian

It is no easy task for an outside military force such as the Wang brothers to control an unfamiliar region and unknown people. To this end, the Wang brothers adopted two significant strategies: the first was to legitimize their position through creating nominal loyalty to the Tang court, and the second was to strengthen their local roots through linking up with different local forces.Footnote 13

As former bandits turned founders of a new regime, Wang Chao and Wang Shenzhi needed Tang court recognition to affirm their legitimacy to local forces. The Tang court appointed Wang Chao as Fujian Surveillance Commissioner (福建觀察使) in 893. In 896, the Tang court elevated Fujian to the status of Weiwu Military Prefecture (威武軍) and promoted Wang Chao to Weiwu Military Commissioner (威武節度使).Footnote 14 After Wang Chao died in 897, Wang Shenzhi declared himself the interim Military Commissioner (liuhou 留後) and submitted a memorial to this effect to the Tang court. The Tang court recognized him as Weiwu Military Commissioner in 898.Footnote 15 In 906, when Zhu Wen 朱溫, the future Emperor Taizu and founder of Later Liang, controlled the Tang court, he supported the court’s decision to confer the title of King of Langya 瑯琊王 on Wang Shenzhi and awarded him a stele that described his benevolent governance. The stele eulogized Wang Shenzhi for “upholding the treaty of alliance with the imperial court, thus setting an example to other military governors” (奉大國之歡盟, 為列藩之表率).Footnote 16 After Zhu Wen usurped the Tang throne, he was eager to win the recognition of the southern kingdoms. Since Zhu Wen and Wang Shenzhi had had positive interactions at the end of the Tang, in 910 Zhu bestowed the title of King of Min on Wang Shenzhi in exchange for his nominal loyalty.Footnote 17 In short, Wang Chao and Wang Shenzhi demonstrated their apparent submissiveness to the northern courts, and the northern courts in return awarded many significant titles to help them strengthen the legitimacy of their local regime.

As outsiders from Gushi County, Wang Chao and Wang Shenzhi sought greater localization through various means to build connections with local forces. When the three Wangs’ soldiers first entered Fujian, they did not intend to stay permanently and planned to return to their home city. When the army marched through Tingzhou 汀州, they encountered a Quanzhou native, Zhang Yanlu 張延魯. With many local elders in tow, Zhang prepared beef and wine to entertain the Wang brothers and to persuade them to settle in Quanzhou. Zhang stated that the current prefect of Quanzhou, Liao Yanruo 廖彥若, was very despotic; henceforth they would support the Wang brothers to replace Liao as prefect. Wang Chao then commanded his troops to defeat Liao and replaced him in 886 with the support and help of the local Quanzhou leaders.Footnote 18 After becoming prefect of Quanzhou, Wang Chao undertook other actions—allowing the return of refugees, reforming the taxation system, and training soldiers—to prove to the local elite that they had indeed chosen a better prefect.Footnote 19

However, the Wang brothers had to assert political power over Fuzhou if they wanted to rule all of Fujian. When Huang Chao’s troops plundered Fujian in 878, Chen Yan 陳巖, a Jianzhou native, organized and assembled thousands of local people to protect their home villages, and the Tang court in 884 bestowed upon him the title of Fujian Surveillance Commissioner. Chen Yan’s governance in Fuzhou was allegedly benevolent, and he had a harmonious relationship with the Fuzhou natives.Footnote 20 After Chen Yan died in 891, his wife’s younger brother, Fan Hui 范暉, acted as interim commissioner. Since Fan was too arrogant to earn the people’s loyalty, Wang Chao decided to seize his position. He dispatched Wang Shenzhi to attack Fan Hui. Once again, the local people helped the Wang brothers. Natives sent rice to feed Wang’s soldiers, and indigenous inhabitants living on the coast supplied them with sea-going vessels.Footnote 21 In contrast to this reliance on the local people, Fan Hui depended on his affinity with Dong Chang 董昌, who was Weisheng Military Commissioner 威勝節度使, occupying the Zhejiang region. Dong Chang responded to Fan’s requests for reinforcements by sending five thousand soldiers on a rescue mission. This civil war persisted for a year before the Wang brothers eventually defeated Fan Hui.Footnote 22 Fan Hui fled from the region by sea and was subsequently killed by the boat people.Footnote 23 The victorious Wang Chao finally controlled Fuzhou, and the Tang court bestowed upon him the title of Fujian Surveillance Commissioner in 893.

Among Wang Chao’s initial actions was to hold an honorable burial for Chen Yan and marry his daughter to Chen’s son.Footnote 24 This action not only eased the tension with Fan Hui’s remnant forces but also built cooperation with the local power groups that had previously been loyal to Chen Yan. To conclude, the Wang brothers’ success in Fujian stemmed not (only) from their military power in Gushi, but from addressing local concerns and gaining strong support from local communities.

The importance of the Greater Puyang literati in the Wang Shenzhi regime

The Puyang literati community played also an important role in legitimizing the Fujian regime. After the Wangs consolidated their control over the whole of Fujian, the number of Puyang jinshi degree holders increased dramatically, allowing the Puyang literati’ network to serve as a key intermediary between the Wang regime and the late Tang government.

Previous studies have noted the marked increase from the mid to the late Tang in the number of Fujian scholars. A recent study observes that in the southeast region (including Jiangnan East Circuit 江南東道 and Jiangnan West Circuit 江南西道) the number of jinshi degree holders in Fujian during the reign of Tang Xizong (r. 873–888) was second only to the number in Zhejiang; and during the reign of Tang Zhaozong (r. 888–904), the number of Fujian degree holders greatly surpassed those from Zhejiang and ranked the highest in the Tang.Footnote 25 This change may indicate that after the Huang Chao Rebellion, the Tang regime preferred to utilize the imperial examinations (which were then not anonymous) to bestow jinshi degrees upon literati whose warlord superiors supported the Tang dynasty. The following are examples from Fuzhou and Quanzhou in Fujian.Footnote 26

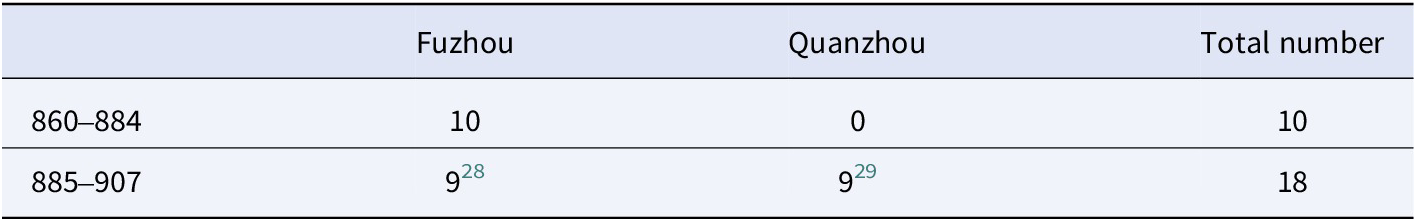

The Huang Chao Rebellion ended in 885, and Tang Emperor Xizong returned from Sichuan to Chang’an. The following year, the Wang brothers occupied Quanzhou. Table 2 shows the number of jinshi in Quanzhou and Fuzhou between 860 and 884, and between 885 and 907.Footnote 27

Table 2. Numbers of Fuzhou and Quanzhou Jinshi in the Late Tang

If we combine these numbers, the jinshi numbers from Fujian almost doubled between 885 and 907, largely due to Quanzhou’s growth. In other words, after the Wang brothers took power, the jinshi number in Quanzhou surged from none in twenty-five years to match that of Fuzhou, the original cultural center of Fujian.

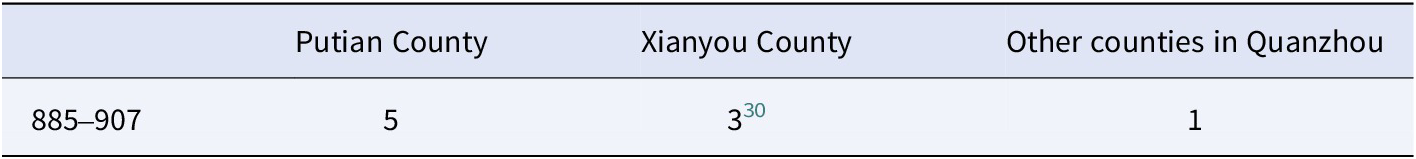

Further analysis of the jinshi numbers within Quanzhou reveals that Putian County (i.e., Puyang) had more jinshi than other counties, as shown in Table 3. Putian County alone accounted for over half the Quanzhou jinshi; and before the end of the Tang, Putian’s neighboring county Xianyou (incorporated into Xinghua Military Prefecture along with Putian County in the early Song), which had thus far produced no jinshi, welcomed their first three degree holders under Wang regime.

Table 3. Jinshi in Quanzhou Counties after 885

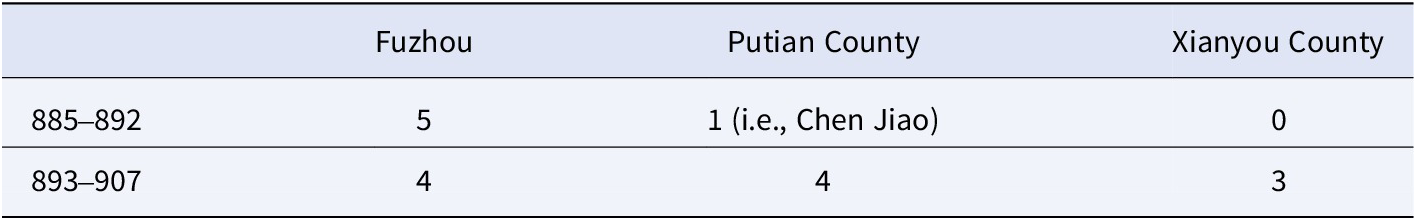

With the year 893 as the cut-off point, when the Wang regime defeated Fan Hui and unified Fujian, the number of jinshi in Fuzhou, Putian, and Xianyou counties was as seen in Table 4. In the eight years between 885 and 892, when Chen Yan and Fan Hui governed Fuzhou, Fuzhou produced five jinshi. During the same period, Putian produced only one. However, after Wang Chao extended his control over all Fujian in 893, Fuzhou produced only four jinshi during the last fifteen years of the Tang, while Putian County produced four, and Xianyou County produced three. Their combined total thus far exceeded that of Fuzhou.

Table 4. Jinshi in Fuzhou, Putian, and Xianyou

In sum, after 893 the number of jinshi from Fuzhou decreased, but the number of jinshi from Putian and Xianyou increased dramatically. This is hardly a coincidence. Under the Tang examination system, candidates had to take a prefecture-level examination before taking the capital examination, and this procedure gave prefects considerable influence in recommending local talents.Footnote 31 Quanzhou, to which the Putian and Xianyou counties belonged, was the first stronghold of the Wang regime; and there is no doubt that the Wang clique trusted the Quanzhou literati more than Fuzhou literati, whom they viewed as subjects of a rival power. When the Wang brothers controlled all of Fujian, they were naturally more willing to recommend Quanzhou literati to the Tang court.Footnote 32 From the perspective of the Tang central government, accepting literati recommended by the southern regimes also guaranteed that the Tang would be able to count on the future support of these emerging southern regimes.

However, the Quanzhou jinshi were not evenly distributed throughout the prefecture. More than half came from Puyang. In the next section, I will show that the gathering of Puyang literati in the mid- and late Tang dynasties provided a good foundation for their preparation for the imperial examinations. In addition, during the Later Liang period, two other Puyang scholars received jinshi degrees in 908, while none from Fuzhou did so.Footnote 33 As mentioned above, the Fujian regime had a good relationship with the Later Liang, and not surprisingly, all the Fujian literati admitted by the Later Liang came from Puyang.

Furthermore, not only did the number of late Tang jinshi from Fuzhou decrease, but the most politically active among them, Huang Pu 黃璞 (jinshi 891) and Weng Chengzan 翁承贊 (859–932; jinshi 896), had close ties to Puyang. Huang Pu, a native of Houguan 侯官, Fuzhou, chose to cooperate with the Wang regime after the Wang brothers defeated Fan Hui. As mentioned above, Wang Chao ordered an honorable burial for Chen Yan, for whom Huang Pu wrote a funeral inscription. This inscription notes the date of Chen’s burial, and that date was only three months after the Wang brothers’ defeat of Fan Hui and their control of Fuzhou. The inscription mentions that Chen Yan’s wife, née Fan, was from a prestigious family; however, it says nothing of her younger brother, Fan Hui, or of the civil war between Fan Hui and Wang Chao.Footnote 34 As the last jinshi from Fuzhou during Chen Yan’s administration, Huang Pu’s cooperation with the Wang regime probably helped consolidate Wang’s rule in Fuzhou.

That Huang Pu was Huang Tao 黃滔’s cousin may explain why the Wang brothers’ regime was able to secure Huang Pu’s cooperation.Footnote 35 Huang Tao, a famous Puyang scholar-official, received his jinshi degree in 895 and served as an Erudite of the Four Gates (Simen boshi 四門博士) in the Tang central government from 898 to 901. In 901 he accepted an appointment from Wang Shenzhi and returned to Fujian as an official and afterward became Wang’s relative by marriage.Footnote 36 Citing Huang Pu family records (jiachuan 家傳), the Puyang bishi 莆陽比事 writes that he “moved to Hantou 涵頭” in Putian. It further writes that Huang Chao forbade his troops from burning Huang Pu’s house because Huang Chao knew that Huang Pu was a famous Confucian.Footnote 37 The truth of this statement may be doubtful, but it does reveal that Huang Pu had moved to Putian before 878 when Huang Chao invaded Fujian. In 895, Huang Pu’s son, Huang Shen 黃詵, took the “Elite Selection” examination (Bacui ke 拔萃科) which required a recommendation from the applicant’s prefectural administrator.Footnote 38 It is clear that the Wang regime recommended Huang Shen. In short, Huang Pu and Huang Shen not only came from the same clan as Huang Tao, but they also moved to Puyang. We can thus conclude with confidence that they belonged to the same literati group.

Regarding Weng Chengzan, the Ba Min tongzhi 八閩通志, compiled in 1489, labels him a native of Putian. Although the Sanshan zhi 三山志, a twelfth-century Fuzhou gazetteer, lists him as a Fuzhou native, it also notes that he “lived in the Suan Ridge 蒜嶺” in Puyang.Footnote 39 The Puyang bishi, compiled in 1214, mentions that Weng Chengzan’s father, Weng Juyu 翁巨隅, moved to Puyang and built the Qilin Studio 漆林書堂 there.Footnote 40 These references all suggest that although Weng Chengzan’s origin was Fuzhou, he was educated in Puyang and had a close relationship with the Puyang literati. The next section will illustrate that Huang Tao addressed Weng Chengzan as a member of “our cohort.” In addition, Weng Ximing 翁襲明, a Puyang jinshi of 906, was the younger brother of Weng Chengzan and a nephew of Huang Tao.Footnote 41 Clearly, the Huang and Weng families were related by marriage. In short, although Table 4 still lists Weng Chengzan as a Fuzhou jinshi, he was closer to Puyang in terms of geographic and personal ties.

To summarize: after 893, the main jinshi community of Fujian which supported the Wang’s regime consisted not only of Puyang literati but also those Fuzhou natives who lived in Puyang. I will refer to them as the “Greater Puyang literati community.” After the Huang Chao Rebellion, the Tang central government was unable to control the South directly. By recruiting more southern literati, it sought to engage emerging political forces supportive of the Tang regime. It was precisely at this time that Fujian scholars, particularly the Greater Puyang literati, made a quantitative leap forward in the imperial examinations.

Unsurprisingly, the Greater Puyang jinshi of the late Tang served as an intermediary between the Wang regime and the Central Plains, shuttling between the central government and the Min regime. Their career patterns were quite similar: after obtaining their jinshi degrees, they first served in the Tang court and then returned to the Wang regime. Apart from Huang Tao mentioned above, Chen Jiao 陳嶠 (825–899) served as Adjutant in Jingzhao Prefecture (京兆府) in Chang’an after earning his jinshi degree in 888. He later returned to Fujian and held several positions under the Wang regime.Footnote 42 Weng Chengzan earned his jinshi degree in 895 and then served as an official in the Tang and the Later Liang 後梁 (907–923) courts. Weng Chengzan went to Fujian in 904 and again in 909 at the behest of the Tang and Later Liang rulers to bestow honorary titles on the Wang brothers, and afterward he chose to stay in Fujian. He became chief councilor during Wang Shenzhi’s rule and wrote funerary inscriptions for Wang Shenzhi and his wife.Footnote 43 Xu Yin 徐寅 (849–938, jinshi 894), traveled to Liang 梁 and presented a flattering poem to Zhu Quanzhong 朱全忠, thus gaining Zhu’s appreciation. He then returned to Fujian to serve as an official.Footnote 44 Another example is Zheng Liangshi 鄭良士, a native of Xianyou. Although he did not have a jinshi title, he submitted five hundred poems to the Tang court in 893 and was given official positions. He later returned to Min to serve Wang Shenzhi, who valued him as a senior scholar.Footnote 45

In addition to their northern connections, the Greater Puyang literati were an important local force. Puyang literati, having spent years preparing for the imperial examinations, were likely wealthy enough to forgo farmwork and cover the travel costs from Fujian to Chang’an. To a considerable extent they monopolized the opportunities for education and examination at the local level.Footnote 46 Wang Shenzhi took a woman from Huang Tao’s family as his concubine. This woman was the biological mother of Min Emperor Huizong 閩惠宗, Wang Yanjun 王延鈞 (r. 926–935). After Wang Yanjun was crowned emperor, he honored his mother as the empress dowager. Wang Yanjun once visited the Huang family temple to pay his respects.Footnote 47 All this demonstrates that the Huangs were influential at the local level.

Another significant role the Greater Puyang literati played was as hosts to the capital-based literati who had escaped to Fujian. For example, Xu Yin hosted Yang Yifeng 楊沂豐, the cousin of Tang Prime Minister Yang She 楊涉, and Wang Dan 王淡, the son of another Tang Prime Minister, Wang Pu 王溥 (?–905). Other capital literati, like Han Wo 韓偓 and Li Xun 李洵, fled to the Min kingdom, and many of them gathered around Huang Tao.Footnote 48 In an inscription, Huang Tao named eleven capital literati who attended a Buddhist assembly held by Wang Shenzhi; he recorded not only their names but also their official positions and places of origin. Huang asserted that these brilliant outside literati agreed that the Min region was safer, and Wang Shenzhi was a sincere lord.Footnote 49 For these displaced capital literati, the Greater Puyang scholars with jinshi degrees would undoubtedly become their trusted counterparts in helping them establish ties with the Wang brothers.

Huang Tao’s narrative of local identity in the early Interregnum

How did the Puyang literati respond to their sudden rise in political status during the late Tang? Fortunately, the collected works of Huang Tao have survived to the present day. Huang Tao’s writings in the early Interregnum clearly display his identification with his hometown, Puyang. This section examines Huang Tao’s discourse on local identity and analyzes it within the political and social context of the early Interregnum. I will reveal how Huang Tao’s narrative of local identity illustrates Puyang as a meaningful spatial unit for the Greater Puyang literati, thereby reinforcing the unique status of the Puyang literati.

In the funerary inscription written for his friend Chen Jiao, Huang Tao clearly expresses his sense of local identity:

Chen [Jiao] and I belong to the same county. The rivers and mountains of Puyang are the best in Minyue.Footnote 50 During the Zhenyuan [785–805] period, Lin Zao attained the top civil service examination degree among the literati in the southeast. Ten years later, Xu Ji also earned the degree. Afterwards, many poets appeared one after another—Chen Houqing, Chen Fan, Chen An, Lin Hao, Xu Wen, Lin Su, Xu Guitu, Huang Yanxiu, Xu Chao, and Lin Yu. All of them wrote elegantly and with a wealth of knowledge. They spent half of their lives taking the examinations but without success. After one hundred years of such ignominy, Chen Jiao [who attained a jinshi degree], followed in the footsteps of his two outstanding predecessors. Seven years later, Xu Yin attained a jinshi degree, and in the next year I [also attained the degree]. Are these successes not the fated result of our rivers and mountains?

愚與公同邑, 閩越江山, 莆陽爲靈秀之最。貞元中, 林端公藻冠東南之科第, 十年而許員外稷繼翔。其後詞人亹亹, 若陳厚慶、陳泛、陳黯、林顥、許温、林速、許龜圖、黃彦修、許超、林郁, 俱以夢筆之詞, 籝金之學, 半生隨計, 沒齒銜冤。曠乎百年, 而公追二賢之後, 七年而徐正字夤捷, 八年而愚[缺一字], 莫不江山之數耶。Footnote 51

Huang elaborates here on two related claims. First, he asserts that the mountains and rivers in Puyang were the best in Fujian. Second, he avers in the last phrase that the outstanding mountains and rivers were the reason that so many talented literati, several of whom earned the jinshi degree, gathered there. Even though the Tang court hosted these examinations, Huang did not mention the court when he discussed the success of local literati. Instead, Huang connected the scholarly achievements of the local literati with the geographic environment in Puyang. In other words, the prominent literati and the auspicious topography of Puyang were, in Huang Tao’s view, mutually confirming. In addition, he claimed that the Puyang landscape was the best in Fujian, implying that Puyang was superior to other sub-regions of Fujian.

This causal relationship between the geographic environment and scholarly achievement in Puyang recurs several times in Huang Tao’s collected works. His funeral oration for Chen Jiao makes a similar proclamation:

Among the mountains and rivers in Min, those in Puyang are regarded as the most magnificent. Once the first Puyang literatus became a degree-holder during the Wude era (618–626), after the wise and outstanding men of the Zhenyuan period, many great scholars appeared one after another [in this region]. Many of them went on to pursue opportunities in the capital.

伏以靈閩之江山, 莆稱秀絶,首武德之科級, 自貞元之英哲, 其後繼生碩儒, 亹亹鴻都.Footnote 52

In another example, a poem praising the Hugong Mountain (壺公山) in Puyang, Huang first rhapsodized over the beautiful and solitary mountain and then claimed that “the mountain’s fame made Puyang proud, and its elegant spirit produced many persons of virtue” (嘉名光列土, 秀氣産羣賢).Footnote 53

In an inscription written for public display in the Lingyan 靈巖 Temple, Huang stated that the temple was located in “the spiritual beauty of Puyang Mountain” (莆山之靈秀). The latter portion of this inscription for a Buddhist temple turns to the literary achievements of Puyang literati. Huang states that Ouyang Zhan, a Quanzhou native, left his hometown to study with Lin Zao 林藻 and Lin Yun 林蘊, who were brothers, Puyang natives, and successful in their examinations.Footnote 54 He attributed the Lin brothers and Ouyang Zhan’s advanced degrees and their prestige in literature to the spiritual power and elegance of Puyang’s mountains and rivers. Huang Tao then mentions that in emulation of their three predecessors, he and his friends gathered at this mountain to study and prepare for the examinations. At the end of this inscription, Huang Tao remarks that after struggling for twenty-four years, he earned the jinshi degree. He then came back to Puyang and visited the temple to show his gratitude to the spiritual power of the mountains.Footnote 55 The repeated theme linking human achievement to Puyang landscape suggests that his interpretation of this human–landscape relationship was intentional and deliberate.

However, in the Lingyan Temple inscription Huang Tao also confessed that during the long interval between Ouyang Zhan in 792 and Chen Jiao in 888, Puyang literati had not been successful in the examinations. He argued that Puyang literati who came from commoner families had almost no chance of attaining the jinshi degree because members of noble families, capital-based elites, monopolized all such opportunities during the Xiantong 咸通 (860–874) and Qianfu 乾符 (874–879) periods. This unfair situation changed in 885 when Tang Xizong 唐僖宗 (r. 873–888) returned to Chang’an from Sichuan after the Huang Chao Rebellion and opened up opportunities for literati from commoner families.Footnote 56 In other words, Huang Tao attributed the failure of Puyang literati to the political situation at the time. However, while members of noble families were indeed predominant in the late Tang civil service examinations,Footnote 57 this fact alone cannot fully explain why no Puyang literati succeeded during this period. Huang ignored the fact that during the same Xiantong and Qianfu periods, Fuzhou produced ten jinshi—all provincial elites.Footnote 58 Huang Tao’s explanation reflects more his personal view than it does a thorough consideration of the facts. However, despite their repeated failures, these Puyang literati continued to travel to Chang’an to take the examinations, and they thus built a connection between their own locale and the court.

We can better understand Huang Tao’s strong identification with Puyang through his use of the phrase “our cohort” 吾黨 to refer to the Greater Puyang literati. For example, he mentioned that after years of failure, Chen Jiao not only obtained the jinshi degree but also accepted a political position in which he could display his literary talents. He further described Chen’s achievement as “wiping out past indignities and bringing some glory to our cohort” (更雪當時之冤滯, 少爲吾黨之隆崇).Footnote 59 Another example is Huang’s farewell poem for Weng Chengzan in 909, when Liang Taizu (r. 907–912) sent Weng as an emissary to Fujian to confer the title of King of Min upon Wang Shenzhi. In the poem, Huang commented, “Who says that the fate of our cohort is hard? The high honor that you [i.e., Weng] enjoy is rare indeed” (誰言吾黨命多奇, 榮美如君歷數稀).Footnote 60 He then opined that Weng Chengzan would be a “guest” during his stay in Min and described his journey back to Bianjing 汴京 as a “return.”Footnote 61 In celebrating the court connections of Weng from “our cohort,” Huang Tao evidently saw no conflict between local and court identities.

Although Puyang seemed to spark Huang’s strongest emotions towards locale, he sometimes turned his attention to the entire Fujian region. When he praised Weng Chengzan’s appointment as a Tang emissary, he proclaimed “although people say there are many virtuous literati in Minyue, who has come home [like Weng] with the special favor from the emperor?” (雖言閩越繫生賢, 誰是還家寵自天).Footnote 62 In his funeral oration for Chen Ding 陳鼎, a native of Fuzhou, Huang similarly wrote, “The Min mountains hold a refined spirit, [just as] the state of Lu holds pristine earth. What heaven bestows congregates in the benevolent people (referring to Chen Ding) of our land” (閩山秀氣,魯國清塵。天之授受, 鍾我仁人).Footnote 63 Both Weng Chengzan and Chen Ding were from Fuzhou, but Huang Tao did not praise Fuzhou in the same way that he praised his hometown of Puyang. Rather, he made a causal connection between the achievements of the two men and the wider Fujian/Min region.

Huang Tao’s rhetoric contrasted sharply with that of mid-Tang literati, who often spoke more broadly of Fujian or Min rather than focusing on a specific place like Puyang. As Chen Ruoshui has pointed out, at the turn of the eighth to ninth century, Fujian scholars had a deep sense of regionalism.Footnote 64 For example, Lin Yun wrote, “Within thirty years, literature will flourish in Min” (三十年內, 文興在閩). Ouyang Zhan mentioned in a poem sent to Lin Yun from Sichuan that when he saw the villages and mountains of Sichuan, he could not help but recall their Min hometowns of Yanshou 延壽 and Fuping 福平. Ouyang Zhan explained, “Yanshou and Fuping are the names of the river and plain in Min. Lin Yun’s villa is in Yanshou, while mine is in Fuping” (延壽、福平皆閩中川原之名, 延夀即藴之别墅在焉, 福平即予之别墅在焉).Footnote 65 In fact, Yanshou River and Fuping Mountain are both located in Puyang. But Ouyang Zhan did not refer to their villas’ more precise locations in Puyang; instead, he adopted the more encompassing name of Min.Footnote 66 In other words, both Lin Yun and Ouyang Zhan identified themselves with the larger geographical region of Fujian. It seems clear therefore that Huang Tao’s emphasis on the fact that the Puyang landscape nourished the Lin brothers and Ouyang Zhan was his own interpretation.

Huang Tao’s discourse on local identity should be read in the context of the political and social environment of the time analysed in the previous section. When Huang Tao claimed that “the rivers and mountains in Puyang are the best in Min,” he was in fact attempting to rationalize the sudden increase in the number of Greater Puyang literati in the imperial jinshi examinations. After the establishment of the Min regime by the Wang brothers, the Greater Puyang literati functioned as a key support for the regime. As local men, not only did this Greater Puyang literati community maintain close personal ties with each other, they also linked the Fujian regime to the Tang and the Later Liang through their attainment of jinshi degrees. Thus, Huang Tao’s focus on Puyang in his expression of local identity may well reflect a sense of competition among scholars from different sub-regions within Fujian, such as Fuzhou, affirming the importance of the Greater Puyang literati in the Fujian regime.

The changing political environment and the marginalization of Puyang literati in the late Interregnum

When Wang Chao and Wang Shenzhi ruled Fujian, they demonstrated their respect for local Confucian literati in order to gain more recognition from the Tang court. However, as the Wang regime became more firmly established, and after the death of Wang Shenzhi in 925, the status of Puyang literati experienced a decline for three reasons.

The first factor that weakened the Greater Puyang literati was their involvement in the internal power struggles of the Wang regime during the later years of Wang Shenzhi’s rule. After Wang Chao’s death, Wang Shenzhi succeeded him. But Shenzhi could only effectively rule northern Fujian, while his second brother, Wang Shengui, served as the Quanzhou prefect. After Shengui’s death, his eldest son, Wang Yanbin 王延彬, served as the Quanzhou prefect for seventeen years. However, in 917, Wang Shenzhi removed Yanbin from his position and killed his aides due to suspicion of rebellion.Footnote 67

Wang Yanbin had a close relationship with some Puyang and Xianyou literati, including Xu Yin, Zheng Liangshi, Chen Cheng 陳乘 (Xianyou jinshi in 894), and Chen Tan 陳郯, a Puyang literatus.Footnote 68 Although Xu Yin and Huang Tao were good friends, the former served Wang Yanbin while the latter was loyal to Wang Shenzhi. Four years after Wang Shengui’s death, Wang Yanbin asked Xu Yin to write a stele inscription for his father. The inscription strongly praised Shengui and also acknowledged his brother Wang Chao, but it contained no praise for Wang Shenzhi. It only states that “[Shengui] and his brother Shenzhi jointly defended the two garrisons, with harmonious rhythms like chi and xun. Their political cooperation is just like Lu and Wei” (與弟審知聯守兩鎮, 韻契篪塤, 政侔魯衛). Although it mentions a good relationship between Shengui and Shenzhi, the narrative places the two in equal positions, completely lacking any indication of Wang Shenzhi’s higher political status. Moreover, Xu Yin interprets Wang Shengui’s burial at Huangji 皇績 Mountain in Quanzhou as follows: “Heaven gives birth to auspicious people, and the earth gives birth to auspicious graves; thus the lord’s mandate came from heaven and his achievements covered the world” (天生吉人, 地生吉穴, 以公之命自天, 以公之勳蓋世).Footnote 69 This suggests a notion of Shengui receiving a heavenly mandate.

As Hugh Clark has pointed out, Wang Shenzhi and Shengui respectively governed northern and southern Fujian.Footnote 70 Correspondingly, the literati of Puyang had different political choices and served different factions. Historical sources suggest that because Xu Yin had offended the Later Tang Emperor Zhuangzong (r. 923–925), Wang Shenzhi followed Zhuangzong’s request not to employ Xu Yin.Footnote 71 But a more likely reason that Wang Zhenzhi refused to use Xu is that Xu was a close aide of his political rival. Another aide of Wang Yanbin, Zheng Liangshi, resigned from his position in the Tang dynasty in 901 and returned to Fujian. He chose to support Wang Yanbin rather than Wang Shenzhi, only accepting Wang Shenzhi’s summons in 915.Footnote 72 No direct historical records detail the impact on the Greater Puyang literati following Wang Yanbin’s punishment in 917, but it seems unlikely that Wang Shenzhi and his successors could trust them again as they once did.

Second, the influence of Daoism gradually surpassed that of the Confucian literati in Min politics. To localize their regime and legitimize their rule over Fujian, the Wang regime utilized local Daoism from the very beginning. Wang Chao and Wang Shenzhi claimed that they were descendants of Wang Ba 王霸, who purportedly became an immortal on Mount Yi 怡 in Fuzhou during the Southern Liang dynasty (502–557).Footnote 73 By propagating this story, the Wang brothers attempted to shed their identity as outsiders and considered themselves locals appointed by the deity to govern Fujian. The successors of Wang Shenzhi further elevated their reverence for Daoism. Wang Yanjun claimed he found a stone inscribed “descendants of Wang Ba” (王霸裔孫). He then built Baohuang 寶皇 Temple beside the Wang Ba alter and let the Daoist Chen Shouyuan 陳守元, a Fuzhou native, be the abbot.Footnote 74 Compared to the Wang Chao brothers, who used the Puyang literati as brokers to gain the legitimacy bestowed by the Central Plains, their successors, Wang Yanjun and Wang Chang 王昶 (r. 935–939), utilized the power of local Daoism to crown themselves as emperors. Consequently, the Daoist group headed by Chen Shouyuan controlled the Min court for nearly ten years.Footnote 75

Third, corresponding to the second development, in the latter period of Wang Yanjun’s rule, he sought the title of emperor and ceased to maintain even a nominal relationship with the Central Plains government, eliminating the need to rely on the literati for communication between the Central Plains and his Min regime. The following story illustrates the waning role of literati in connecting the local and Central Plains regimes during the late Min Kingdom. In 937 Zheng Liangshi’s eldest son, Zheng Yuanbi 鄭元弼, traveled north on behalf of Wang Chang to deliver a letter to the Later Jin court. In the letter, Wang Chang wrote provocatively to Jin Emperor Gaozu (r. 936–942) that, in contrast to the unstable regimes in the north, Min was flourishing and thus demanded equality with the Later Jin. Not surprisingly, the letter angered the Jin emperor and Zheng Yuanbi was imprisoned. In an attempt to absolve himself, Zheng bowed down before the Jin emperor and called Wang Chang “a ruler of barbarians, who does not understand rites and justice.” Zheng was released and allowed to return to Min.Footnote 76

Records of Puyang literati after the death of Wang Shenzhi in 925 reveal they did not enjoy the same high status they did during the early Min regime, and some distanced themselves from the political arena.Footnote 77 They found themselves in an increasingly precarious position due to the power struggles among the sons and grandsons of Wang Shenzhi.Footnote 78 At the same time, Fuzhou literati became more competitive. For example, Wang Yanjun chose a Fuzhou native, Ye Qiao 葉翹, who was learned and modest, to be Wang Chang’s teacher. After Wang Chang was enthroned, Ye Qiao received an important position at the Min court.Footnote 79 In addition, in 928, when Wang Yanjun was the Min ruler, Chen Baoji 陳保極, a Fuzhou literatus, received the jinshi degree from the Central Plains, while no literatus from Puyang was able to obtain the degree after Wang Shenzhi died.Footnote 80 Compared to Wang Chao and Wang Shenzhi who, as enemies of Fan Hui, distrusted the Fuzhou literati, Wang Shenzhi’s successor was not handicapped in this way. In addition, placing the Min capital in Fuzhou naturally led to an increase in the influence of the Fuzhou men.

There is no surviving source on how the Puyang literati viewed their increasingly marginalized position. But clearly, for the Puyang men, a more independent and autonomous Min regime that kept its distance from the Central Plains regimes would not be conducive to the maintenance of their own superiority.

The Min kingdom fell in 945, and the Southern Tang, the Wu Yue kingdom, and local warlords then occupied and controlled Fujian. In the Later Zhou 後周 and the early Song, the local warlords Liu Congxiao and Chen Hongjin 陳洪進 successively governed Quanzhou and Zhangzhou, then under the nominal control of the Southern Tang. However, as the Southern Tang grew weaker during the Later Zhou, the southern Min regime saw no need to maintain allegiance to the Southern Tang. Instead, the warlords sought to become direct feudatories of the Northern courts. In 959, the Later Zhou Emperor Shizong 後周世宗 (r. 954–959) rejected Liu Congxiao’s request to be his nominal subordinate, because the Zhou emperor asserted that Liu should be loyal to the Southern Tang.Footnote 81 However, soon after the Song dynasty replaced the Later Zhou, Song Taizu (r. 960–976) changed his stance toward these local warlords.Footnote 82 In 963, Chen Hongjin submitted a memorial to express his willingness to be entitled as a Song official. Song Taizu accepted Chen’s request despite protests from the Southern Tang.Footnote 83 In his edict to Chen, Taizu complimented Chen’s sincere desire to be his subordinate and claimed that it was reasonable to approve Chen’s request because Taizu himself was now the ruler of “civilized world” (華夏).Footnote 84

The Song court, however, viewed southern Fujian ruled by Chen Hongjin as a disorderly periphery. In Taizu’s edict to the Southern Tang, he described Quanzhou and Zhangzhou as “rather remote and distant” (甚為僻遠), thereby justifying his responsibility to prevent turmoil and the ruler-subject relationship he established with the Southern Min regime.Footnote 85 In 975, the Song military conquered the largest southern kingdom, the Southern Tang, heralding the Song’s imminent control of southern China. In 977, Chen Hongjin left his territory to present himself at the Song court; and he submitted the southern Fujian territory to the Song the following year. The amnesty edict stated: “This remote culture has begun to come under the influence of our imperial civilization. To foster a sense of belonging, greater emphasis should be placed on gentle care” (矧惟遠俗, 初被皇風。用安歸向之心, 倍注撫柔之意).Footnote 86 This edict prominently asserted the superiority of the Song court over the uncultured periphery of southern Fujian.

A local revolt unfortunately confirmed the image of southern Fujian as a disorderly area. At the end of 978, the same year Chen Hongjin surrendered his territory to the Song throne, a pre-planned rebellion broke out in Puyang. More than one hundred thousand “robbers from the forests” (i.e., bandits, 草寇) in Xianyou, Putian, and Baizhang 百丈 took advantage of the regime change to gather and attack Quanzhou. Since only three thousand soldiers defended the city, the army supervisors (監軍) He Chengju 何承矩 and Wang Wenbao 王文寶 made plans to abandon Quanzhou city. The controller-general (通判) Qiao Weiyue 喬維岳 thwarted their plans and asked Liangzhe Fiscal Commissioner (兩浙轉運使) Yang Kerang 楊克讓 to rescue the city.Footnote 87 After the relief of the siege of Quanzhou, another army supervisor, Wang Jisheng 王繼昇, led two hundred soldiers in a nighttime ambush, successfully captured the bandits’ leader, and escorted him to the Song court. Having lost its leader, the revolt soon collapsed.Footnote 88 This challenge to Song authority by local forces shows that the court’s authority over southern Fujian was not unquestioned.

This revolt undoubtedly reinforced the Song court’s impression of Puyang as a remote and turbulent region. After this rebellion, Puyang was separated from Quanzhou. In early 979, Taizong made Youyang Garrison (游洋鎮), located between Quanzhou and Fuzhou, into Xinghua Military Prefecture, and the following year incorporated Putian and Xianyou counties into the new jurisdiction.Footnote 89 The next section will explore how the local literati in Puyang and the state, after the Song dynasty’s unification, overcame their mutual mistrust from the long-term independence and the recent revolt.

Early song narratives praising the court

After about half a century of scarcely being mentioned in historical records in the late Interregnum, Puyang literati reemerged in the early Song. However, following the turmoil in Fujian during the late Interregnum, the new local literati were no longer the Huang, Xu, or Weng families.Footnote 90 At the beginning of Song rule over Fujian, Puyang literati displayed a positive, cooperative approach toward the new dynasty, a stance markedly different from the defiant local military. Chen Renbi 陳仁璧, a Putian native and a former official under Chen Hongjin’s regime, wrote an inscription in 983 for the new government office complex in Xinghua Military Prefecture. He adopted a humble outlook towards his own locale and expressed his admiration for the Song emperor and for the Xinghua prefect:

In the seventh month of the eighth year of the Taiping xinguo 太平興國 [976–984] of the Great Song, an edict was issued to move the Military Prefecture to [Putian] and establish its [government office] here … His Majesty has achieved his grand enterprise and enlightens all under heaven. Like heaven and earth, he supports [all things], not leaving aside even animals and plants. Like the light from the sun and moon, [his Majesty] without fail scrutinizes even faint and remote things. In the spring of the fourth year of his rule, [he] issued an edict to the relevant officials: “I examined the atlas of Quanzhou and Fuzhou and noticed that Youyang [Town] is between these two prefectures. This area is full of dangers and obstacles, and the people may not be trustworthy. We should carefully choose an administrator to show them what is right and ensure they are educated and return to good deeds.” Accordingly, Xinghua Military Prefecture and Xinghua County were established, and [the court] commanded Assistant Director of the Court of the National Granaries Duan Peng, a native of Jingzhao, to govern them. On the day of his arrival, Master Duan Peng propagated the emperor’s instructions and proclaimed his governance. [He] swayed them with rites and music and guided them with loyalty and filiality. Those affected by abominable customs and those who were previously uncultured have all been reformed. The yellow-turban rebels have changed their attire to that of the common people; the forests are empty of brigands, and the wastelands are cultivated … The happiness of common people is like a drought relieved by the rains and children cared for by their parents … In the summer of the fifth year [of the Taiping xinguo], his Majesty knew the area [of the Xinghua Military Prefecture] was not large enough, so he incorporated Putian County and Xianyou County from Quanzhou into Xinghua Military Prefecture. People [i.e., of Putian and Xianyou] who were from the neighboring areas before admired Duan’s virtue; therefore, they were changed by his manners and became obedient without his instruction.

皇宋太平興國八年秋七月, 詔移軍於茲而建之。 … … 今上皇帝纘成丕緒, 光宅天下, 法乾坤覆載, 則動植罔遺; 象日月照臨, 而幽遐必察。踐祚之四年春, 詔有司曰:「嘗覽泉福圖志, 睹游洋界于兩郡, 地多險阻, 民或未信, 必謹擇其人往義之, 必從化而遷善也。」乃立興化軍暨縣, 命司農寺丞京兆段公鵬兼之。公至之日, 誕敷皇猷, 昭宣政教, 風之以禮樂, 導之以忠孝。染頑囂之俗, 舊為不類者, 咸與惟新。黃巾變而服飾同, 綠林空而汙萊辟。 … … 百姓胥悅, 如旱歲之遇膏雨, 嬰孩之得父母也。 … … 五年夏, 上知其地未廣, 乃以泉郡莆田及仙遊屬焉。厥民曩鄰于境, 嚮公之德, 皆望風而化, 不教而順。Footnote 91

In this inscription, Chen Renbi describes the town of Youyang as an uncultured area in need of enlightenment from court officials. He then weaves together a complex rhetoric that lauds Song Taizong’s rule as emperor and Duan Peng’s governance as prefect. He regards Duan Peng as a successful governor who implemented rites from the central court and thus transformed the remote area into a cultured place. In Chen’s narrative, the Puyang locals were thrilled to accept and be absorbed into the civilization defined by the central court. He further asserts that the people of Putian and Xianyou admired Duan Peng’s governance and, happy for his guidance, became part of Xinghua Military Prefecture. In this narrative, Chen, local literatus though he was, adopts a top-down perspective, composing a story of “where the wind passes, the grass bends.”

To further understand Chen Renbi’s narrative, it is necessary to consider his family background. Fortunately, Chen Renbi’s epitaph is among the few early Song Fujian literati biographies that survive. Composed in 995 by Wang Yucheng 王禹偁 (954–1001), a famous early Song scholar-official, the inscription emphasizes that Chen’s family had always longed to serve the northern courts. The epitaph first discusses Chen Renbi’s father, Chen Hang 陳沆, who received the jinshi degree in the Later Liang and then obtained an appointment in Daming 大名 Prefecture. According to the epitaph, Chen Hang foresaw the imminent upheaval in the Later Liang and consequently resigned his position to return to Fujian. Although his career experiences were very similar to those of the Puyang jinshi in the late Tang, the epitaph proclaims he refused any appointment offered by the Wang regime and thus remained free of the stain of association with illegitimate officials throughout his life. Regardless of whether Chen Hang’s epitaph reflects the real reason he did not serve the Min regime, the essential point is that the text describes his distance from the Min kingdom as both justified and moral. Following this narrative logic, Wang Yucheng continues to explain why Chen Renbi, unlike his father, ultimately decided to accept many positions in the Min kingdom and from the southern Fujian warlords. He cited Chen Renbi’s own opinion that since he had no jinshi degree, he would endanger himself if he offended those violent warlords. Therefore, the inscription states, Chen Renbi “suffered himself to accept their appointments” (屈身應命), underscoring that he accepted positions in the local regimes only with great reluctance.Footnote 92

Wang Yucheng then continued to state how Chen Renbi and his son Chen Jing 陳靖 (948–1025) looked forward to serving the Song court. During the Kaibao 開寶 era (968–976), Chen Renbi paid tribute to the Song court on behalf of Chen Hongjin. Song Taizu bestowed upon Chen Renbi a red robe and a nominal position as administrative supervisor (錄事參軍), which nevertheless conferred his identity as a Song official. After Chen Renbi returned to southern Fujian, he persuaded Chen Hongjin to surrender his territory to the Song court.Footnote 93 When he did so, most officials in Chen Hongjin’s local regime lost their official status. Even Qian Xi 錢熙, Chen’s favorite and nephew-in-law, could not obtain a position at the Song court.Footnote 94 Chen Renbi’s family, however, met with exceptional treatment. Chen Renbi, already old and having received a political title from Song Taizu, decided to remain in Puyang and let his second son, Chen Jing, assume a Song political position on his behalf.Footnote 95 In office, Chen Jing befriended outstanding Song literati such as Sun He 孫何 (961–1004), Ding Wei 丁謂 (966–1037), and Wang Yucheng.Footnote 96 During his official career, Chen Jing submitted many memorials to emperors Taizong and Zhenzong 宋真宗 (r. 997–1022) and won their respect.Footnote 97 In his later life, Chen Jing gained high position in Fujian and finally retired as prefect of Quanzhou.Footnote 98

These details of the political fortunes of three generations of the Chen family help us to further analyze the rhetoric of Chen Renbi’s inscription for the Xinghua Military Prefecture office complex. First, Chen Renbi had served the local regimes for many years. He went on behalf of Chen Hongjin to pay tribute to the Song and suggested that Chen Hongjin might surrender his territory, proof that Chen Renbi had won Chen Hongjin’s trust. Since Chen Hongjin was a Xianyou native, both Chens were Puyang men, a fact that might have led the Song government to view them with suspicion. To emphasize their loyalty, therefore, Chen was eager to show that his father had been determined not to serve the “bogus” southern regimes and that he himself was also reluctant to assume positions in local regimes. This narrative was intended to show that the Chen family’s loyalty to the Song was unquestionable.

Second, as mentioned in the previous section, the revolt that occurred right after Chen Hongjin surrendered his territory intensified Song Taizong’s distrust of the Puyang region. In this moment of crisis, Chen Jing walked to Fuzhou to offer information about the rebels and helped the Song military suppress the revolt, thus demonstrating his desire to cooperate with the Song court.Footnote 99 Consequently, when Chen Jing asked Wang Yucheng to write a funerary inscription for his father, Wang’s narrative repeatedly stressed the Chen family’s disaffection from the local regimes and its deep appreciation for the central court.

Written for the construction of the Xinghua official complex, the inscription would undoubtedly be displayed on site and read by government officials and local literati. On the surface, Chen Renbi’s inscription describes the people of Puyang as ignorant of propriety and uneducated, but this should not be interpreted to mean that Chen looked down on his own hometown. As a scholar-official of the former local regime, Chen was in fact proclaiming to the Song that the people of Puyang had already submitted to the Song court with sincerity, and that Puyang was no longer the land of former rebels. In sum, the monument in fact symbolizes the initial establishment of a cooperative relationship between Puyang and the Song government.

Two other public inscriptions, both written by Duan Quan 段全 in early Song Puyang, also adopt a similar narrative of the Central Plains civilizing remote places, but the author’s account differs subtly from Chen Renbi’s in his cultural assessment of Fujian. Duan Quan was Xianyou county district defender (縣尉) and a native of Jinjiang 晉江 County in Quanzhou. Both Jinjiang County and Puyang belonged to Quanzhou and were ruled by local warlords during the late Interregnum. Duan Quan would have had a deep understanding of the mistrust between Puyang and the central government in the early Song. Accordingly, his inscription’s narrative represents the viewpoint of both Song officials and local literati.

The first inscription was written in 1000, for the Xinghua prefectural Confucian shrine. Duan Quan mentions that Fang Yi, a Puyang native, lamented the deterioration of the Confucian Temple and organized his locals to rebuild the temple in 999. But a lack of funds delayed the restoration work. In the following year, Fang Yi took the imperial examination and received the jinshi degree. He took the opportunity to appeal to Song Zhenzong for official funding to build the local Confucian temple to “manifest your culture and learning to the distant people [of Puyang]” (以示文教於遠人), indicating that Puyang people looked forward to the civilizing influence of the Song court. Song Zhenzong not only instructed the central treasury to allocate three hundred thousand copper coins but also ordered the Xinghua prefectural administration to preside over the construction project. Thus, Duan asserted the significance of the construction of the Confucian temple was that “those who were already learned became virtuous, and those who had not yet pursued learning became learned.” (已學者進而為賢者, 未學者化而為學者). Later, after carefully recording the ritual objects in the temple, the inscription writes that “compared to its counterparts in Capital region and Zou and Lu, this temple [in Puyang] lacks nothing in cultural refinement.” (比夫畿甸、鄒魯作者, 則廟之文不一闕也). The final note praises “[Fang] Yi’s efforts that have transformed Min into Lu” (變閩為魯, 實儀之力).Footnote 100 Overall, this inscription reveals that while local literati acknowledged Puyang as a cultural borderland, they claimed that twenty years of Song rule had boosted their cultural self-confidence.

In 1002, Duan Quan wrote another inscription for the Confucian temple built by the Xianyou County government on a vacant lot southeast of the county office. He emphasized how the Xianyou temple perfectly replicated the rituals of the Confucian temple at Zoulu 鄒魯. Although he again regarded the Confucianism of the Central Plains as superior, the text is more explicit in demonstrating his cultural confidence in Fujian. The beginning of the inscription laments that Fujian was not influenced by Confucianism during the Three Dynasties; not until the Tang dynasty did any Confucians from Fujian serve as officials under the Central Plains states. Duan Quan then asserted:

the great Song uses its culture to instruct all lands under heaven and demands prefectures and counties submit every year ten times as many talented men as before; and men from Min comprise three to four out of ten. We can see from this fact that the merit of our great Song far exceeds that of the Three Dynasties, the Han, and the Tang.

盛宋以文化天下, 歲詔州縣貢秀民十倍於昔, 而閩人十計三四 。有以見吾宋之德邁三代, 逾兩漢,越李唐遠矣.Footnote 101

While praising Song rule, he also highlighted the large number of Fujian literati who, despite the long distance, were willing to join the Song regime.

Chen Renbi’s deprecatory description of his hometown, Fang Yi’s pleas to the central government for the local Confucian temples, and Duan Quan’s account of Fujian’s flourishing Confucianism all indicate the process by which rulers and ruled developed mutual trust amid the decline of local regimes and the shift to unified dynastic governance. The conscious portrayal of the relationship between the local and the central government by the local literati also suggests that, after a century of the Interregnum, this rapprochement was not easily achieved.

The limitations of the surviving historical sources make it impossible to ascertain if there were other local voices in early Song Puyang that were less appreciative of the Confucian indoctrination from the Central Plains. What is certain is that the three inscriptions by Chen Renbi and Duan Quan were preserved for five hundred years and eventually included in the Xinghua fuzhi 興化府志 compiled in 1503. According to this gazetteer, Duan Quan’s inscription for the Xianyou Confucian temple was first inscribed on a stele erected in 1002, and was erected again in Puyang by the county magistrate, Chen Jie 陳接 in 1183.Footnote 102 Fang Dacong 方大琮 (1183–1274), a famous scholar-official of the Southern Song and Fang Yi’s descendant, wrote enthusiastically that after Chen Hongjin surrendered his land to Song, “the status of Puyang was elevated to a prefecture, and the literati’s morale increased greatly” (莆陞為郡, 士氣百倍). Fang Dacong went on to claim that Fang Yi had traveled to the central court expressly to request construction of the Confucian temple, for which he became famous in the capital.Footnote 103 By the thirteenth century, Fang Yi’s story had become a cultural resource for the Fang clan to enhance the prestige of their family. All this shows that the aspirations of the Puyang scholars to connect with the Central Plains had become the dominant local narrative, and these three inscriptions became key texts for future generations of Puyang people to understand their local history in the early Song.

Conclusion

It is generally agreed in our academic community that literati of the Northern Song aspired to work in the central government. A political question, however, remains so far unanswered: after a century of independence in the south, can we assume that the Northern Song would undoubtedly establish friendly relations with the southern literati? This article provides a micro analysis and detailed research on Puyang, Fujian.

It is precisely because the existence of the Interregnum regimes challenged the connections between the Central Plains and the South that the late Tang court became more aware that collaborating with local literati was key to maintaining a ruler–subject relationship with southern regimes. The imperial examination system played a crucial role in facilitating this cooperation. Although more research is needed, the case of Puyang suggests that the emergence of the Fujian regimes in the late Tang may have created more opportunities for local literati to succeed in the jinshi examinations and enter the Tang central government. Thus, the rise of local literati and the decline of capital-based elites may not be entirely a replacement relationship, but rather a phenomenon that occurred before the capital elites were largely exterminated by Zhu Quanzhong in 904.Footnote 104

Correspondingly, during the late Interregnum, as the Fujian regimes ceased cooperation with the Central Plains regime, the literati were marginalized. For the early Song court, the challenges posed by the Interregnum to the northern regimes ultimately stimulated the Song court to recognize the importance of seeking cooperation with southern scholars. This may also explain why Song Taizong, after unifying the south, significantly expanded the number of jinshi through the imperial examination.Footnote 105 As this article demonstrates, Puyang literati actively responded to this new situation. The local literati’s adoption of narratives of court-centered Confucian indoctrination came to reshape the relationship between the Central Plains and the borderland. Through their public inscriptions, the Puyang literati ensured the stability of their regions and expressed a willingness to cooperate with the Central Plains regime.

From a nation-wide perspective, how do we assess the cooperative relationship between the central government and the Puyang literati’s efforts at the beginning of the Song dynasty? An obvious fact is that even though the imperial examination was open to literati from all regions, there were significant differences in both the willingness of local literati to participate and the number who passed across different areas. Literati from many regions performed poorly at the imperial examinations and thus had fewer opportunities to participate in political activities. Accordingly, fewer historical records survive from these areas. As mentioned in the introduction, in the early stage of the Northern Song, Puyang, along with Fuzhou and Jianzhou, had achieved outstanding results in the civil service examinations. Duan Quan’s inscriptions show that Fujian literati were particularly active in taking the imperial examinations.Footnote 106 The success of Fujian in the imperial examination system in the Northern Song should be closely related to the wealth accumulated from prosperous commercial trade in this region since the mid-Tang period, especially during the Interregnum, and the subsequent investment of that wealth in education.Footnote 107 If we can think of the relationship between the southern administrative districts and the central court as a spectrum, with the far left representing a distant relationship and the far right representing a close relationship, then Puyang would likely sit on the far right of the spectrum. As this article argues, this harmonious and cooperative relationship did not form naturally, but was a conscious cooperation undertaken by center and locale to overcome the distrust caused by regional independent powers during the Interregnum.

Finally, we can gain some valuable reflections from Huang Tao’s discourse on local identity in the late Tang, even though it cannot be directly compared to the potential local identity tendencies that emerged after the Southern Song.Footnote 108 Huang Tao’s strong narrative of local identity was written for the politically active Greater Puyang literati community rather than for those who were involved in local infrastructure. This was local pride grounded in phenomenal political success.Footnote 109 The local narratives from Huang Tao to Chen Renbi also show no linear development of local identity. Huang Tao’s culturally advanced Puyang contrasts sharply with Chen Renbi’s depiction of it as remote and backward eighty years later. This “degradation” reflects neither Puyang’s actual development nor Chen Renbi’s indifference to his hometown. In fact, their narratives of the same locale are firmly embedded in their respective political frameworks, both seeking to connect their region with the Central Plains regimes. In other words, local identity functions more as an “expression” about a place and is not necessarily closely tied to the “localization” of literati. The absence of expressed local identity does not imply a lack of concern for their homeland. However, when literati choose to articulate their local identity in their writings, it indicates that their local space holds significance for establishing social and political networks.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers for the journal for their insightful comments. I also appreciate the valuable suggestions provided by the associate editor, Prof. Beverly Bossler. I presented a draft of this article online at the “Conference on Tang–Song Transitions” at Princeton University in June 2022, where I received many inspiring opinions. I am especially indebted to the readers of the early drafts, including Prof. Hugh Clark, Prof. Charles Hartman, Shih Yu-cheng, and Chen Ruth Yunru, for their critical and thought-provoking ideas.

Funding

This article is one of the outcomes of my research project, “The Changing Relationship between Local Literati and the State: A Case Study of Puyang, Fujian from the Tenth to Twelfth Century,” funded by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (General Research Fund, 2021/2022, Project No. 15601521).

Competing Interests

The author declares none.