Introduction

Euthanasia or assisted suicide (EAS) for psychiatric disorders, legal in some European countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands, remains controversial (see Box 1). Although psychiatric EAS cases comprise a relatively small number of cases overall, their proportion has increased from 0.06% to 1.2% during the period 2010–2017 in the Netherlands (RTE, 2017). Personality disorders are present in at least half of those who request and receive psychiatric EAS (Thienpont et al., Reference Thienpont, Verhofstadt, Van Loon, Distelmans, Audenaert and De Deyn2015; Kim et al., Reference Kim, De Vries and Peteet2016). Given their chronicity, prevalence, significant symptom burden, and impact on outcomes of co-morbid Axis I psychiatric disorders (Tyrer et al., Reference Tyrer, Reed and Crawford2015), it is perhaps not surprising that these disorders are so common in patients requesting EAS. Such disorders raise some important issues for further examination. In particular, the characteristic features of personality disorders, such as feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and suicidal thoughts (which are usually addressed therapeutically) may be difficult to distinguish from feelings of intolerable and hopeless suffering (which are eligibility criteria for EAS) (Swildens-Rozendaal and van Wersch, Reference Swildens-Rozendaal and van Wersch2015). Thus, it may be challenging to evaluate whether there really is no prospect of improvement and no alternative to EAS in such cases. Furthermore, because personality disorders are known to evoke complex interpersonal interactions, including with health care providers (Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Huisman, Legemaate, Nolen, Polak, Scherders and Tholen2009), managing such dynamics in the EAS evaluation process may require special care and expertise.

Box 1. Brief background on EAS practice and regulation in the Netherlands.

The Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide Act was enacted in 2002, formalizing what had been legally protected practice based on court decisions (Griffith et al., Reference Griffith, Weyers and Adams2008). The Act's due care criteria for EAS require that the physician must be satisfied that patient's request be voluntary and well-considered and the patient's suffering is unbearable and with no prospect of improvement. The physician must inform the patient about his/her situation and prognosis and must come to the conclusion, together with the patient, that there is no reasonable alternative in the patient's situation. The procedural criteria require that at least one, independent physician be consulted and that due medical care is exercised in performing EAS (Swildens-Rozendaal and van Wersch, Reference Swildens-Rozendaal and van Wersch2015).

All cases must be reported to the Dutch regional euthanasia review committees (Regionale Toetsingscommissies Euthanasie (RTE); https://www.euthanasiecommissie.nl/uitspraken-en-uitleg) which reviews all EAS reports. There are five RTEs, with the goal of providing uniform guidance. They are committed to transparency and publish on their website a selection of case reports that are deemed ‘important for the development of standards’ to provide ‘transparency and auditability’ of EAS practice (RTE, 2014; Swildens-Rozendaal and van Wersch, Reference Swildens-Rozendaal and van Wersch2015). Given the controversial nature of psychiatric EAS, the RTE has published a relatively high proportion of the cases – publishing all psychiatric cases from 2013, for example (RTE, 2014). The RTE has since reduced the number of published psychiatric EAS cases.

The End-of-Life Clinic (Levenseindekliniek) is an organization founded in 2012, which provides EAS evaluation for persons whose treating physician declined to perform EAS. Most patients who receive EAS at the End-of-Life Clinic are non-terminally ill (Levenseindekliniek, 2018). A review of the activity of the End-of-Life Clinic has been published (Snijdewind et al., Reference Snijdewind, Willems, Deliens, Onwuteaka-Philipsen and Chambaere2015).

The debate regarding psychiatric EAS has mainly focused on treatment-resistant depression as the paradigm case (Schuklenk and van de Vathorst, Reference Schuklenk and van de Vathorst2015; Blikshavn et al., Reference Blikshavn, Husum and Magelssen2017; Steinbock, Reference Steinbock2017), and personality disorders have received little attention so far despite their prevalence and their unique challenges in the context of psychiatric EAS. This study aimed to describe the characteristics of patients with personality disorders who receive EAS and how their requests for EAS are evaluated, given the potential challenges in evaluating these patients’ beliefs about irremediability of their condition.

Methods

According to the RTE website (see Box 1) as of 1 October 2017, a total number of 232 psychiatric EAS cases had been reported to the RTE since 2010: two cases in 2010, 13 cases in 2011, 14 cases in 2012, 42 cases in 2013, 41 cases in 2014, 56 cases in 2015, 60 cases in 2016, and four cases in 2017Footnote 1Footnote †. One hundred and sixteen of these 232 cases (50%) were published and available on the RTE website during the period between 1 June 2015 and 1 October 2017.

We selected 74 cases based on the goals of our study, using the following criteria. Category 1 included the cases where a formal diagnosis of a personality disorder was reported (n = 48; 65%), including personality disorder not otherwise specified (NOS). Because the RTE reports are not always written with precise clinical language and because persons can have clinically significant symptoms of a personality disorder without fully meeting diagnostic criteria (Oldham, Reference Oldham2006; Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Chelminski, Young, Dalrymple and Martinez2012), we included two more categories of patients. Category 2 included the cases without a formal diagnosis but with explicit mention of prominent personality difficulties or ‘traits’ (n = 16; 22%). This included specific mention of cluster A, B, or C ‘personality traits’Footnote 2, or ‘impaired personality development’. Because of the clinically significant overlap between (cluster B) personality disorders and interpersonal hardship following trauma as seen in some disorders, e.g. complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Giourou et al., Reference Giourou, Skokou, Andrew, Alexopoulou, Gourzis and Jelastopulu2018), a third category included cases with explicit mention of early traumatic events and chronic residual symptoms of interpersonal dysfunction (n = 10; 13%), defined by the presence of chronic/complex PTSD (n = 6), self-harming behavior (n = 8), psychotic or dissociative symptoms (n = 4), or a combination of those.

We analyzed the cases using a directed content analysis, as described previously (Kim et al., Reference Kim, De Vries and Peteet2016). Cases were read and coded independently by a bioethicist-psychiatrist (M.N.) and a consultation-psychiatrist (J.P.). The first author (M.N.) is a native Dutch speaker and reviewed all of the cases in original Dutch. For the second author (J.P.), of the 74 cases, 40 cases had been translated into English and have been analyzed for a different set of variables, as described previously (Kim et al., Reference Kim, De Vries and Peteet2016). The remaining 34 cases were machine translated (using Google translate). Discrepancies in coding occurred in 9% of coded items (505/5476 total), and for each discrepancy, the Dutch-speaking author reviewed the accuracy of the English translation by comparing it with the original Dutch text. Discrepancies involving a difference in judgment between the two readers were revolved through discussion, involving an additional reader, a bioethicist-psychiatrist (S.K.).

The coding scheme was developed iteratively and in light of the main research domains: (a) patient characteristics; (b) patients’ treatment histories; (c) treating physicians’ responses to EAS requests; (d) the EAS evaluation process (duration, consultants involved, relevant texts regarding due care criteria, and RTE judgments); (e) emerging themes, such as features of the End-of-Life Clinic cases. The data were analyzed using SPSS statistical data package, version 25. Analysis consisted of frequencies and tabulations, and exploratory post-hoc tests of bivariate associations, without hypothesis testing given the descriptive goals of the study.

Results

Characteristics of patients

Seventy-six percent (n = 56) of patients were women (Table 1). Nineteen percent were younger than 40 and 51% were older than 60. About two-thirds of the cases (65%, n = 48) mentioned cluster B personality disorders or traits, and 18% (n = 13) were personality disorders NOS. In the remainder, 9% (n = 7) had cluster C traits only and 3% (n = 2) mentioned cluster A traits.

Table 1. Characteristics of 74 patients who received EAS for personality and related disorders

a Age groups overlap but reflect the categories used in the RTE reports.

All but two patients had comorbid Axis I psychiatric conditions (97%, 72 cases) (Table 2). The three most common conditions were depression (unipolar or bipolar) in 70% (n = 52), PTSD or prominent post-traumatic symptoms in 31% (n = 23) and anxiety disorders in 31%. Somatoform disorders were present in 19% of the cases (n = 14) (including conversion, somatization, and unspecified somatoform disorders).

Table 2. Psychiatric Axis-I comorbidity

a This column does not add up to 100% because some patients had multiple diagnoses.

Thirty-eight percent (n = 28) had only psychiatric diagnoses and 62% (n = 46) had in addition one or more physical comorbidities. These conditions included musculoskeletal and rheumatologic disorders in 23 cases (including osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, polyarthritis, bone fractures), chronic or generalized pain disorders (chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia, chronic pain) in eight cases, neurological disorders (migraine, anosmia, stroke and sequels, ataxia, head trauma, neurogenic bladder, and quadriplegia) in 14 cases, cardiovascular disease (heart failure, cardiac surgery, and myocardial infarct) in three cases, and pulmonary disease (mostly COPD) in five cases.

Forty-two percent of the patients were described as functionally dependent (n = 31). This was the case in 11% (three out of 28) of the cases with only psychiatric problems, and in 61% (28 out of 46) of the cases with physical comorbidity.

Treatment history

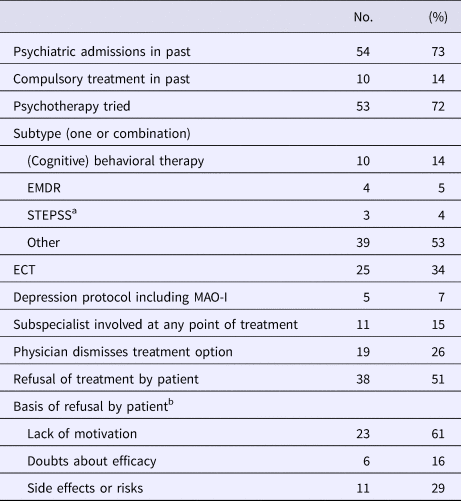

Seventy-three percent (n = 54) of patients had a psychiatric admission in the past, and in 14% (n = 10) some form of compulsory or other court-ordered treatment was mentioned (Table 3). Psychotherapy had been tried in 72% (n = 53), mostly of unspecified nature (39 of 53). Among the known standard evidence-based treatments for cluster B personality disorders, ranging from cognitive-behavioral to psychodynamic treatments (Zanarini, Reference Zanarini2009; Cristea et al., Reference Cristea, Gentili, Cotet, Palomba, Barbui and Cuijpers2017), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) was not mentioned in any cases, mentalization-based treatment (MBT) was considered but not tried in one case, and schema-focused treatment (SFT) was mentioned once.

Table 3. Treatment history

a In the Dutch reports, the term ‘VERS’ was used (abbreviation for Vaardigheidstraining Emotie Regulatie Stoornis), a supportive group treatment similar to STEPPS (‘Systems training for emotional predictability and problem solving’) (Van Wel et al., Reference Van Wel, Bos, Appelo, Berendsen, Willgeroth and Verbraak2009).

b Total sum more than 100 because some patients refused for different reasons.

About a third (34%, n = 25) of patients received electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) at some point; treatment with all indicated medication types for depression including a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAO-I) was mentioned in 7% (n = 5). A subspecialist involvement in the patient's treatment history was mentioned in 15% (n = 11) of the cases (e.g. when patients were referred to a ‘specialized clinic’ or ‘tertiary academic center’). However, a subspecialist involvement in the EAS evaluation process itself occurred only in one case (2013-27), where a psychiatrist who specialized in geriatric psychiatry evaluated an elderly patient.

In one of the two cases without an Axis-I diagnosis (2015-19), there was no mention of any form of psychiatric treatment.

About one-half (51%, n = 38) of the patients refused some form of treatment which included hospital admissions, medications, psychotherapy, other modalities (including ECT), or a combination. Forty-three percent (16 of 38) of these patients refused more than one treatment modality. The main reason for refusals was a lack of motivation (61%, 23 of 38).

In a fourth (26%) of the cases (n = 19), physicians appeared to consider a treatment option and then determined that it need not be tried. The most common reasons given were that the physician thought the patient may not benefit from it (n = 13) or was not motivated enough (n = 6). For example: ‘In theory there were other treatment options for the personality disorder (…) but the psychiatrist noted it was an open question whether the patient could cope with these treatments and whether she could form and uphold an adequate treatment relationship’ (case 2016-01). As in this case, in more than half of the cases where a physician considered and then dismissed a treatment option (10 out of 19 cases), there was also a mention of the patients not wanting treatment. In most cases, the patients expressed their refusal first.

Refusal of prior EAS requests

Overall, 46% (34 of 74) of EAS cases occurred after at least one doctor refused to provide it. In 29 (39%) cases, the treating GP refused to endorse the EAS request. The main reason for refusal was a non-specific ‘for own reasons’ or ‘complexity’ of the case. The GPs mostly explained complexity either as the combination of physical and psychiatric conditions [‘the GP was very involved but found it difficult to perform EAS in this particular case, whereby somatic and psychic suffering were entangled’ (2014-40)] or in reference to the patient's personality [‘the complexity… was grounded in the fact that the patient was a difficult, not very nice man who had difficulties expressing himself’ (2014-37)].

In 32 (43%) cases, the request was made to a treating psychiatrist, and half (n = 16) of the psychiatrists refused to perform EAS. The main reasons were ‘own reasons’ (n = 11), due to criteria considered not met (n = 3), and reasons of conscience (n = 2).

In 11 cases (15%), both the patient's treating psychiatrist and the GP refused the request. Notably, most (eight of 11) of these were recent cases (2015–2017), meaning that 30% (eight of 27) of published cases from those years involved both the GP and the psychiatrist refusing the request. All 11 cases received EAS at the End-of-Life Clinic, and in nine of those cases, the EAS physician was not a psychiatrist.

Roles of psychiatrists and other doctors in the EAS evaluation process

In over a third (36%, 27 of 74) of cases, there was no mention of current treating psychiatrist involvement at the time of the EAS request (Table 4). In 30% (22 of 74) of the cases, the EAS physician was a psychiatrist. In 50% of all cases, the EAS physician was new to the patient (n = 37), and most of those patients received EAS at the End-of-Life Clinic (n = 32).

Table 4. Process of EAS evaluation

a Any discussion beyond the statement that the patient made a ‘well-considered request’.

Although the Dutch law does not require that the EAS consultant be a psychiatrist even in psychiatric EAS cases, the RTE's Code of Practice of 2015 requires consulting an independent psychiatrist (Swildens-Rozendaal and van Wersch, Reference Swildens-Rozendaal and van Wersch2015). In 41% of the cases, a psychiatrist was one of the official EAS consultants (n = 30); in 53% (n = 39) of cases, the EAS physician relied on a less formal ‘second opinion’ of a psychiatrist; and in five cases (7%), there was no independent psychiatrist involved. In those five cases, the RTE found that the due care criteria were not met in one case (2014-01), did not address the lack of psychiatric consultation (2012-62 and 2014-74), or explained its discretion in applying the rules (2011-124658 and 2015-45).

End-of-Life Clinic and patients with physical comorbidities

Forty-three percent of the cases were referred to the End-of-Life Clinic (n = 32), either after refusal of a physician (n = 26) or through self-referral (n = 6) but not all cases of physician refusals ended up at the End-of-Life Clinic. End-of-Life Clinic cases were more likely to be older than 60 [75% (24 of 32) v. 33% (14 of 42), p = 0.0005, Fisher's exact test]. Although not statistically significant, a current treating psychiatrist was less often involved [53% (17 of 32) v. 71% (30 of 42) in End-of-Life Clinic cases, p = 0.14]. The patients were less likely to have tried psychotherapy [53% (17 of 32) v. 86% (36 of 42), p = 0.004] and the physician evaluating/performing EAS was less often a psychiatrist [13% (four of 32) v. 43% (18 of 42), p = 0.005]. The official consultant was a psychiatrist in 38% (12 of 32) but 13% (two of 16) in 2015–2017; a second opinion psychiatrist was involved in 72% (23 of 32).

Patients with physical comorbidity were more likely to have had a prior EAS request refused by their psychiatrist, referred to the End-of-Life Clinic, and less likely to have tried psychotherapy (Table 5).

Table 5. Comparison of psychiatric EAS evaluation of patients with and without physical comorbidity

a Fisher's exact test.

b Among those who had a prior treating psychiatrist, n = 32.

Assessment of the unbearableness of suffering

According to the RTE (following the Dutch Psychiatric Association Guidelines), the unbearableness of suffering, while defined subjectively by the patient's perspective, ‘must be palpable (‘invoelbaar’) to the physician’ (Swildens-Rozendaal and van Wersch, Reference Swildens-Rozendaal and van Wersch2015). Among the 116 psychiatric EAS cases published by the RTE, the term ‘invoelbaar’ is used in 34 cases and 31 of those (91%) were cases with personality disorders or difficulties: e.g. ‘the unbearableness of the suffering was palpable for the physician by the way the patient looked, the way she spoke about her life, the sadness and powerlessness that she emanated’ (2011-125900).

Discussion

Despite having received little attention so far, persons with personality disorders constitute more than half of those who request and receive psychiatric EAS (Thienpont et al., Reference Thienpont, Verhofstadt, Van Loon, Distelmans, Audenaert and De Deyn2015; Kim et al., Reference Kim, De Vries and Peteet2016). Addressing such EAS requests from persons with personality disorders could be particularly challenging as these patients may have self-destructive behavior, a traumatic background, feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and despair (Verhofstadt et al., Reference Verhofstadt, Thienpont and Peters2017) which may create challenges in EAS evaluation of irremediability. Furthermore, personality difficulties can influence interpersonal dynamics that could affect the EAS evaluation process.

Characteristics of patients

Most patients had a long history of a complex set of comorbid conditions. In contrast to a Belgian report of 100 requestors of psychiatric EAS who were younger with few medical co-morbidities (Thienpont et al., Reference Thienpont, Verhofstadt, Van Loon, Distelmans, Audenaert and De Deyn2015), we found that 51% were over 60 years old, nearly two-thirds had comorbid physical disorders, and 61% were functionally dependent to some degree. Almost all had co-morbid Axis-I psychiatric disorders (with 70% having two or more). In only two patients were personality difficulties the sole psychiatric basis for EAS (both had comorbid chronic pain). Thus, EAS of persons with personality difficulties most often occurs in persons with long psychiatric and medical histories. Many treating physicians were aware of these issues as indicated by frequent references to ‘complexity’ of cases when explaining their refusal of EAS requests.

On the other hand, these patients shared features common to suicidal persons with personality difficulties. Women, who are more likely to attempt suicide (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Haro, Bernert, Brugha, de Graaf, Bruffaerts, Lepine, de Girolamo, Vilagut, Gasquet, Torres, Kovess, Heider, Neeleman, Kessler and Alonso2007; O’Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Wetherall, Cleare, Eschle, Drummond, Ferguson, O'Connor and O'Carroll2018), were disproportionately represented (76%). Many patients had a depressive disorder (70%), a previous suicide attempt (47%, with multiple attempts in 36%), self-harm (27%), and a traumatic background (36%). There was evidence of demoralization and difficulties relating to others: ‘She suffered from the meaninglessness of her existence (…) Because she was not able to connect with others, she experienced deep despair and loneliness’ (2015–32: 50–60 years, personality disorder NOS and chronic pain) and ‘(t)he patient's suffering consisted of continuous negative thoughts and negative judgments about herself’ (2014–78: 30–40 years, PTSD, borderline personality disorder, multiple suicide attempts).

Evaluation of EAS requests

Irremediability is a key due care requirement; patients need not to go through ‘every conceivable form of treatment’ but they do not meet the requirement if they refuse ‘a reasonable alternative’ (Swildens-Rozendaal and van Wersch, Reference Swildens-Rozendaal and van Wersch2015). Not all patients appeared to receive some standard treatments, such as ECT and MAO-inhibitors for mood disorders. Over a fourth of patients (27%) had not been hospitalized. Most notably, psychotherapy, the primary treatment for personality disorders (Bateman and Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2015; Bateman et al., Reference Bateman, Gunderson and Mulder2015), was not tried in 28%.

It is known that having a personality disorder is a predictor of poor outcome of comorbid Axis-I disorders (Newton-Howes et al., Reference Newton-Howes, Tyrer, Johnson, Mulder, Kool, Dekker and Schoevers2014; Tyrer et al., Reference Tyrer, Reed and Crawford2015). However, both cognitive and psychodynamic psychotherapeutic treatments have proven to be effective for personality disorders (Leichsenring and Leibing, Reference Leichsenring and Leibing2003; Bateman and Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009; McMain et al., Reference McMain, Links, Gnam, Guimond, Cardish, Korman and Streiner2009; Swenson and Choi-Kain, Reference Swenson and Choi-Kain2015; Cristea et al., Reference Cristea, Gentili, Cotet, Palomba, Barbui and Cuijpers2017). For example, DBT and MBT have shown to reduce suicidal behavior in patients with borderline personality disorders (Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Tutek, Heard and Armstrong1994, Reference Linehan, Comtois, Murray, Brown, Gallop, Heard, Korslund, Tutek, Reynolds and Lindenboim2006; Bateman and Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009; Kvarstein et al., Reference Kvarstein, Pedersen, Folmo, Urnes, Johansen, Hummelen, Wilberg and Karterud2019) and MBT and SFT to reduce depressive symptoms in these patients (Bateman and Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009; Bamelis et al., Reference Bamelis, Evers, Spinhoven and Arntz2014). In fact, treatment guidelines of both the American Psychiatric Association and the Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction (Trimbos Institute) advise DBT, MBT, or SFT for the treatment of persons with borderline personality disorders (Trimbos Institute, 2008; Oldham et al., Reference Oldham, Gabbard, Goin, Gunderson, Soloff, Spiegel, Stone and Phillips2010), and applying evidence-based treatments for personality disorders is cost-effective (Meuldijk et al., Reference Meuldijk, McCarthy, Bourke and Grenyer2017). However, DBT was not mentioned in any of our case reports, MBT was mentioned but not tried in one case, and SFT occurred once. What factors, then, may explain the variability of past psychiatric treatments, psychotherapeutic in particular, in patients with personality disorders receiving psychiatric EAS?

One reason for these results may be that due to the patients’ chronic, complex histories, clinicians were inclined to accept the patients’ perspectives more readily. This would be consistent with a trend that Dutch psychiatrists note as an evolution toward accepting patients’ subjective definition of irremediability (den Hartogh, Reference den Hartogh2017; Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al., Reference Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Legemaate, van der Heide, van Delden, Evenblij, El Hammoud, Pasman, Ploem, Pronk, van de Vathorst and Willems2017). Second, the high prevalence of medical comorbidities in persons with psychiatric disorders may lead physicians to treat the patients predominantly as ‘medical’ patients. This might be influenced by clinicians’ general tendency to consider personality disorders as coincidental rather than as a true diagnosis (Tyrer et al., Reference Tyrer, Reed and Crawford2015; Van and Kool, Reference Van and Kool2018). It is notable that over a third (36%) did not have a treating psychiatrist at the time of their EAS request, only 30% of the EAS physicians were psychiatrists, and half of the EAS evaluations were managed by physicians new to the patient. When other psychiatrists were involved, this tended to be for cross-sectional evaluation of EAS eligibility, not treatment.

A third reason may be that counter-transference issues [(tegen)overdracht] may no longer be emphasized. Although counter-transference has long been recognized as a challenge in EAS evaluations involving personality disorders (Groenewoud et al., Reference Groenewoud, Van Der Heide, Tholen, Schudel, Hengeveld, Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Van Der Maas and Van Der Wal2004; Berghmans et al., Reference Berghmans, Huisman, Legemaate, Nolen, Polak, Scherders and Tholen2009), the term is not mentioned in any of our case reports. Yet vigilance regarding counter-transference seems especially important given that the RTE directs physicians to use their own reactions to patients’ suffering [‘palpable’ (‘invoelbaar’)] in EAS evaluations. It is notable that ‘palpable’ is used almost exclusively (91%) in cases with personality difficulties. Thus, physicians seem uniquely emotionally affected by the suffering of patients with personality disorders seeking EAS. This raises the question of whether the RTE's guidance may lead physicians to operate within a patient's psychopathology. For example, a clinician may identify with a patient's perception of irremediability (e.g. ‘nothing will work’): ‘Other therapeutic avenues were explored including Mentalization Based Therapy (MBT). However, the patient did not want to be treated anymore. The physician agreed with her as her personality structure was deemed not strong enough to endure such a drastic treatment (MBT) without her suicidal tendencies or depression getting out of control’ (2014-78). However, as mentioned earlier, this evidence-based treatment is especially beneficial for high clinical severity patients (Kvarstein et al., Reference Kvarstein, Pedersen, Folmo, Urnes, Johansen, Hummelen, Wilberg and Karterud2019), with positive effects on suicidality and depressive symptoms (Bateman and Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009).

Implications

The results of our study raise questions about how to interpret the irremediability requirement in patients with personality disorders. There is substantial evidence for the effectiveness of several psychotherapeutic treatment options on outcome measures such as depressive symptoms or suicidal behavior (Bateman and Fonagy, Reference Bateman and Fonagy2009; McMain et al., Reference McMain, Links, Gnam, Guimond, Cardish, Korman and Streiner2009; Cristea et al., Reference Cristea, Gentili, Cotet, Palomba, Barbui and Cuijpers2017). Furthermore, although the number of studies are limited (Leichsenring and Leibing, Reference Leichsenring and Leibing2003), long-term follow-up shows that the majority of persons with personality disorders achieve sustained remission (Zanarini et al., Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Reich and Fitzmaurice2012). Whether these results would be generalizable to some of the more complex cases in our study – with multiple psychiatric and somatic comorbidities – is an open question. However, it is important to note that treatment studies targeting personality disorders and psychiatric comorbidity such as depression are still lacking (Van and Kool, Reference Van and Kool2018). Similarly, the complex interplay between psychiatric and somatic comorbidity, in particular in female patients, needs further study (WHO, 2001).

The results of this study may support recent proposals to improve psychiatric EAS evaluation that include a longer-term evaluation, more than one independent expert input, and a parallel therapeutic focus on recovery while the EAS request is evaluated (Vandenberghe et al., Reference Vandenberghe, Titeca, Matthys, Van den Broeck, Detombe, Claes, De Fruyt, Hermans, Lemmens, Peeters and Van Buggenhout2017; Gastmans, Reference Gastmans2018). Our results show that young, physically healthy psychiatric patients with personality disorders may be more likely to receive expert attention attuned to their personality disorders. But in older patients with multiple somatic conditions, this may be less so. These results suggest that these patients with both psychiatric and somatic conditions may require a higher level of psychiatric expertise during the evaluation process given the complexity of their clinical conditions and their sparser past psychiatric treatment history. In these patients’ assessments, a ‘medical model’ seems to predominate rather than a more psychologically oriented model focusing on coping and interpersonal skills. While the Dutch euthanasia law allows for physicians’ discretion, the results raise the question of whether sufficient safeguards are in place, including the necessary expertise in personality disorders.

Involvement of experts may be limited by the reluctance of psychiatrists to be involved in EAS (Onwuteaka-Philipsen et al., Reference Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Legemaate, van der Heide, van Delden, Evenblij, El Hammoud, Pasman, Ploem, Pronk, van de Vathorst and Willems2017) and the physician-centric nature of EAS evaluations (with no official role for other mental health professionals, such as psychologists and other therapists, who may have more expertise in the long-term management of personality issues). The need for more expertise in personality disorders may also apply to the RTEs given its difficulties in finding mental health professionals to serve on the RTE (Doernberg et al., Reference Doernberg, Peteet and Kim2016; Kurniawan and van der Zwaard, Reference Kurniawan and van der Zwaard2018).

Finally, these results, which are based on retrospective reviews, suggest a need to prospectively investigate psychiatric EAS in persons with personality disorders, focusing on the patients’ perceptions underlying their requests for EAS and on their clinicians’ decision-making when evaluating those requests, with special attention to how the granted EAS requests differ from those that are denied.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. First, the RTE does not publish all psychiatric EAS cases, limiting generalizability of studies based on only the published cases. These were all completed EAS cases, and do not include requests that did not lead to EAS. However, the RTEs intend the published cases to serve educational, precedent setting functions so that they do carry a special significance (RTE, 2014). Further, these published reports comprise the only source of reliable EAS case information beyond anecdotal media reports. Second, the qualitative coding requires judgment in interpretation. Moreover, given that the reports are not always written in clinical language, there was often a lack of specificity regarding the type of personality disorder and their diagnostic descriptions. Although two-thirds of our cases had a formal diagnosis of a personality disorder, we chose to risk over inclusion in order to include all patients with personality difficulties. Third, our use of statistical tests was post-hoc, using a small sample. However, this report comprises all available case descriptions of an infrequent but growing phenomenon which allowed for patient-level analysis. Finally, because this article focuses mainly on the irremediability requirement, we did not address the issue of mental capacity in personality disorders, a complex issue (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Richardson, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2008; Ayre et al., Reference Ayre, Owen and Moran2017) which requires a separate discussion.

Conclusion

Personality disorders are common in persons receiving psychiatric EAS. For most patients, their personality difficulties were part of complex clinical histories with multiple psychiatric and physical comorbidities. These patients generally had long histories of suffering, with features common to suicidal persons with personality disorders, including histories of serious self-harm, suicide attempts, and demoralization. However, in the EAS evaluations of these patients, especially if the patients were older with physical co-morbidities, the EAS physicians tended to be non-psychiatrists who were new to them at a specialty EAS clinic and relied on less formal, cross-sectional psychiatric second opinions. The current practice of psychiatric EAS involving persons with personality difficulties raises important questions about whether the special challenges associated with personality disorders are being thoroughly addressed. The lack of specialist and longitudinal evaluations may impede an objective evaluation of irremediability and limit the focus on recovery. The issues raised are worthy of further investigation and discussion, especially as some jurisdictions consider legalization of psychiatric EAS.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719000333.

Author ORCIDs

Marie E. Nicolini, 0000-0003-1111-4372.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Carl Runge for assistance with data entry. M.N. thanks the Pellegrino Center for Clinical Bioethics and Kennedy Institute of Ethics, Georgetown University, where she was a Visiting Scholar during which part of this research was carried out. We thank Frank G. Miller, Ph.D. (Cornell University), Yeates Conwell, M.D. (University of Rochester), and Eric Caine, M.D. (University of Rochester), for their comments provided on an earlier draft of this manuscript. No compensation was provided.

Author contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work: all authors. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: all authors. Final approval of the version to be published: all authors.

Financial support

Funded in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, USA (S.K.).

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval by an IRB was not needed according to US federal regulations because this study used publicly available anonymized data [see US Code of Federal Regulations (45 CFR 46.102f)].