Introduction and Background

The Problem

All around the world, as mass gatherings (MGs) take place, health outcomes for many events have been reported and analyzed.Reference Aitsi-Selmi, Murray and Heymann1-Reference Yezli and Alotaibi4 Currently, there is an imperfect understanding of which factors influence health outcomes at MGs, both at the individual and population levels, and how the level of the supporting health services affects these outcomes.Reference Ranse, Hutton and Keene5 Because standardized data reporting does not currently exist, the ability to make meaningful comparisons between similar and dissimilar MGs demonstrating radically different health outcomes is challenging due to heterogeneity in the definitions and variables reported in the literature.

A Partial Solution

Improving the understanding of health outcomes requires the standardization of post-event medical reporting. Case reports, case series, and field reports all have a recognized role to play in advancing knowledge, and many health care specialties have recommended specific standards for reporting as an important strategy for improving data collection.Reference Bradt and Aitken6-Reference Wardle and Roseen13 In the context of MGs, standardized reporting has been discussed for years, with several authors having argued that this strategy will improve the quality of case reports.Reference Arbon14-Reference Schwellnus, Kipps and Roberts18 Setting minimum standards for case reporting is recognized as an important strategy for improving data quality.Reference Schwartz, Nafziger, Milsten, Luk and Yancey3,Reference Bradt and Aitken6,Reference Hotwani, Rambhia and Mehta7,Reference Maas, Harrison-Felix and Menon9,Reference Wardle and Roseen13

The goal of this project was to create and launch a lean, practical, efficient, and effective post-event medical reporting template.

Research Questions: What are Essential Variables for Post-Event Medical Reporting?

Also of interest to the research team, from a knowledge translation perspective, was understanding the role of professional journals in advancing the science underpinning MG medicine.

Methods

Literature Review

A decade (January 2009-December 2018) of MG case reports (n = 54) were analyzed.Reference AlAssaf19-Reference Westrol, Koneru, McIntyre, Caruso, Arshad and Merlin71 In brief, the authors analyzed case reports published in two peer-reviewed journals: Prehospital and Disaster Medicine and Current Sports Medicine Reports, with the search strategy outlined in Turris, et al.Reference Turris, Rabb and Munn62 An additional literature search was undertaken looking for existing models describing data reporting methods for MG health outcomes. Existing models were identified, compared, and summarized.

Template

The template proposed in the present paper is based on data from an earlier study by Turris, et al detailing the current state of post-event medical reporting.Reference Turris, Rabb and Munn62 Both quantitative and qualitative methods were employed. Analysis of the data from that study led to a deeper understanding of what might constitute systematic, rigorous, lean data collection and analysis for a soon to be realized future state. Specifically, the authors identified the lack of well-developed conceptual models to underpin and inform data collection vis a vis clinical presentations, disposition, and health outcomes. Initial conceptual models supporting the proposed publication template are published elsewhere.

The goal of this project was to create a lean, practical, efficient, and effective post-event medical reporting template, containing only essential variables that might aid in rigorous comparison between events. Note that the astute reader will argue that the definition of “essential” could be argued a number of different ways, depending on capacity, event type, and many other factors. The authors acknowledge that the proposed template is version 1.0 and will evolve over time with discussion, debate, and collaboration amongst members of the international MG community. As well, authors would be at liberty to include additional detail as appropriate.

Based on the data domains, essential variables were selected for the template using the following criteria:

1. Reported in peer-reviewed MG literature;

2. Highly relevant to understanding the basic context of the event;

3. Highly relevant to understanding the risk level of the event;

4. Highly relevant to understanding the capacity of the event to manage patients on-site; and

5. Captured an important concept related to the impact of events on local health services infrastructure.

Two examples of how variables were screened for inclusion/exclusion were as follows. “Gender” is an oft-cited data point in the MG literature; however, based on a review of the 54 case reports, in none of those papers did gender offer any insights into health-related outcomes for events. Although gender is important in comparing populations of attendees or participants, it was judged not to be essential to understanding the health outcomes of a given event. In contrast, temperature was both oft-cited and essential to understanding health outcomes, and so temperature was included in the template.Reference Anikeeva, Arbon and Zeitz20,Reference Divine, Daggy, Dixon, LeBlanc, Okragly and Hasselfeld27,Reference Woodall, Watt and Walker70

Data Dictionary

A data dictionary is a living document that provides a list of variables along with clear, standardized definitions, moving users away from inconsistent naming conventions and variations in data reporting. The primary purpose of a data dictionary is to provide a “controlled vocabulary” that reduces inaccuracies and the variability of the data.Reference Linnarsson and Wigertz72 Having a data dictionary imposes standards for reporting and can produce data that is comparable across multiple users.Reference Arenson, Bakhireva and Chambers73,Reference McCabe, Nic An Fhailí and O’Sullivan74 The data dictionary was assembled by the research team with the aid of documents and resources from the following sources, and those sources are cited in the findings section of the manuscript:

World Health Organization (WHO; Geneva, Switzerland);

Government publications;

Published peer-reviewed literature;

Policy statements from professional organizations;

Grey literature; and

Expert opinion.

Results

Template

Based on the four data domains developed (ie, Event, Hazard and Risk, Capacity, and Clinical Domains) and the screening criteria described above, 25 essential variables were identified as most relevant for post-event case reporting (Table 1).

Table 1. Essential Variables for Post-Event Medical Reporting

Abbreviations: ACP, advanced care paramedic; ATR, ambulance transfer rate; CEL, Celsius; EMR, emergency medical responder; FA, first aid; FR, first responder; HLC, higher level of care; LPN, licensed practical nurse; MD, medical doctor; NP, nurse practitioner; PCP, primary care paramedic; PPR, patient presentation rate; PPST, percentage of patients seen and transferred to hospital; RN, registered nurse; RPN, registered psychiatric nurse; PA, physician assistant; SFA, standard first aid; TP, total patients; TTHR, transfer-to-hospital rate.

Table 2. Data Dictionary for Event Domain

Table 3. Data Dictionary for Hazard and Risk Domain

Table 4. Data Dictionary for Capacity Domain

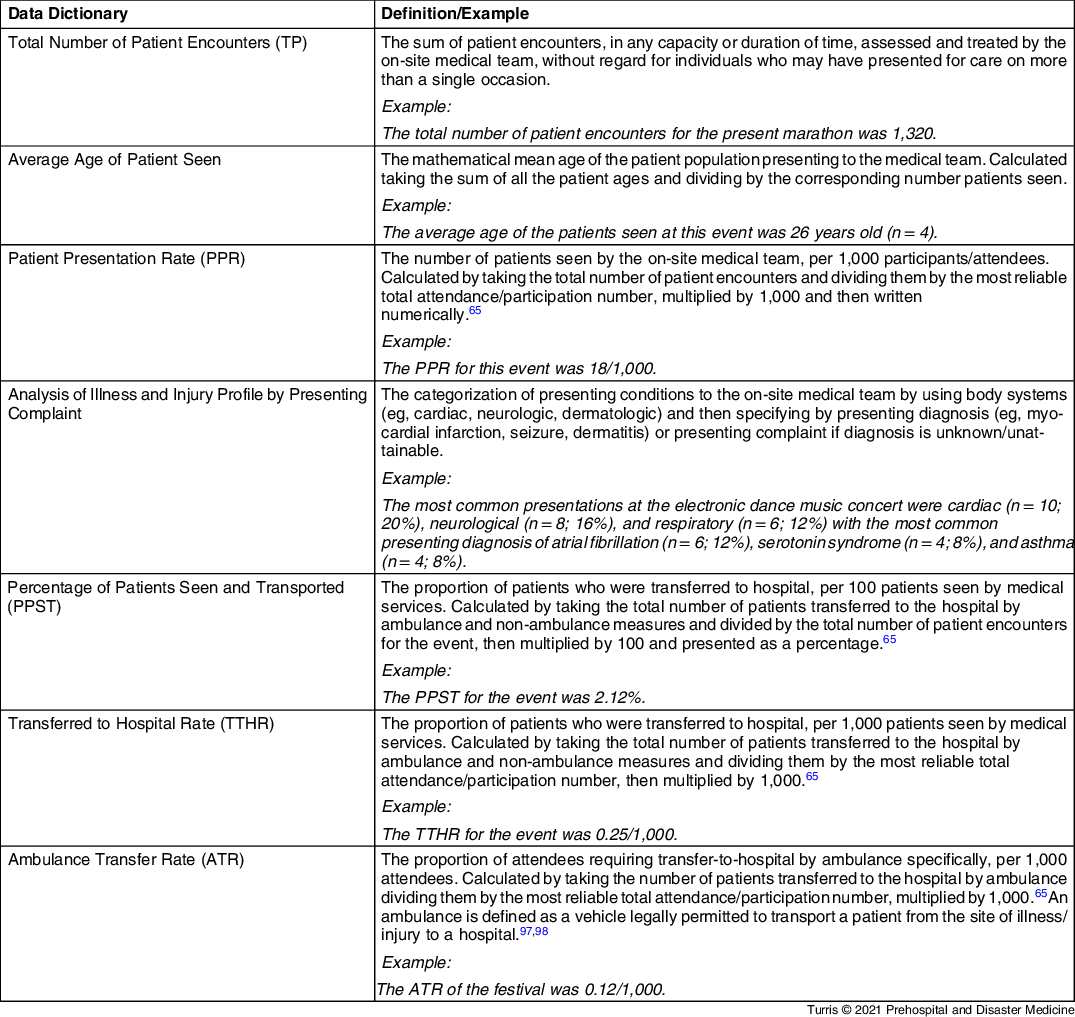

Table 5. Data Dictionary for Clinical Narrative

Data Dictionary

The following abbreviated data dictionary provides the background required for reporting on the 25 essential variables (Table 2Reference Turris, Lund and Hutton75, Table 3 Reference Milsten, Tennyson and Weisberg49, Reference Munn, Lund, Golby and Turris53, Reference Turris, Callaghan, Rabb, Munn and Lund65, Reference Jaensch, Whitehead, Ivanka and Hutton76-Reference Yazawa, Kamijo, Sakai, Ohashi and Owa91, Table 4Reference AlAssaf19, Reference Dutch and Austin28, Reference Gutman, Lund and Turris33, Reference Turris, Callaghan, Rabb, Munn and Lund65, Reference Nelson, Turnbull and Bainbridge92-96, and Table 5Reference Turris, Callaghan, Rabb, Munn and Lund65, 97, Reference Eburn and Bendall98).

Discussion

Setting the Stage

The authors of the present paper have argued that a post-event medical reporting template should contain only essential variables. The alert reader may be wondering why the template proposed above is perhaps more comprehensive than the contents of many published case reports. For example, the current template contains multiple variables that address hazard and risk and focuses on variables that provide measures of capacity (for on-site and community medical services). This was a deliberate choice. As argued by Aitsi-Selmi, et al, influencing the health outcomes associated with MGs requires a comprehensive approach, looking at upstream factors that contribute to outcomes, rather than focusing solely on the outcomes.Reference Aitsi-Selmi, Murray and Heymann1 Turris, et al took a similar position arguing that a broad understanding of the context of an event category, event type, and the characteristics of a specific event are necessary to interpret and understand health outcomes.Reference Turris, Rabb and Munn62

A reporting template, incorporating carefully selected variables, can be both lean and comprehensive. Of note, the authors are proposing a standardized set of 25 variables be collected for every event, at a minimum. If additional variables are provided, that decision should rest with the authors of a given event report. For example, any unique occurrences such as a stage collapse, fire, or the total number of fatalities (if applicable) would also be important to report at the discretion of the research team.

Planning for Data Collection

Each of the 25 essential variables listed in the template are relatively easy to report if some planning with regard to data management is incorporated in the pre-event planning phase. Creating a plan for collecting each of the 25 variables will improve the chances that each data point will be addressed after the event is completed. For example, consider documentation of patient encounters. If there is no space on the form to enter the patient’s age or arrival/discharge times, clinicians and researchers will be unable to report on those specific variables. Alignment between the collection of encounter data and reporting data is therefore key.

The current proposed template for post-event medical reporting supports written, peer-reviewed case reports. However, in the near future, the authors hope to develop an international, online Registry for MGs. This will reduce one barrier to an exchange of knowledge that is created by the length of time it takes to move a project from conception, to analysis, to writing, and then to peer review and publication. This process can result in a delay of one or more years. It is hoped that the creation of a Registry, based on earlier work that confirmed proof of concept, will eliminate that delay.Reference Lund, Turris, Amiri, Lewis and Carson99

Retrievability of Reports

Once pre-event planning has occurred, the event has taken place, and the data have been analyzed, publication is the final step. The authors propose that all clinicians and researchers consider carefully when choosing a title for submitted manuscripts, to improve retrievability. The words “case report” and the type of event should appear in the title (eg, “Case Report on an Obstacle Adventure Course in a Hot Climate”). Similarly, in order to improve retrieval, the authors propose two to five keywords/phrases that identify areas covered in the case report; “mass-gathering medicine” and “mass-gathering health” should be included as keywords, as well as the event type (eg, “obstacle adventure course,” “triathlon”).

Challenges

Although the ultimate desired result is an internationally standardized case reporting template for post-event medical case reports, standing in the way of achieving this result lie a myriad of challenges. At the macro level, launching a standardized reporting template depends on the willingness of researchers and clinicians, as well as journal editors, to support and operationalize standardized reporting. This challenge has been met in other contexts within health sciences.Reference Bradt and Aitken6-Reference Maas, Harrison-Felix and Menon9,100

In terms of public policy, standardized reporting would benefit local governments and decision-making authorities because the quality of the data would improve. However, at this time, local governments are seeking to understand how to support community events while preserving local services for the host community. Attention is not currently being directed toward standardized reporting of outcomes. Advocacy at the level of local, state, and federal governments might advance the adoption of standardized reporting.

As discussed above, the time it takes to move a study from the conceptual stage to publication is considerable.Reference Björk and Solomon101 The time it will take to grow, evolve, and improve a post-event reporting template, based on feedback from the international community, will require additional time and resources. And, it may not be possible to engage a fully representative sample of the MG community.

At the meso level, challenges related to data collection and analysis, in the absence of a partnership with a research team, may be solvable if the reporting template is stream-lined and straightforward. And at the micro level, as discussed above, medical directors will need to consider and embed the collection and management of data within event medical plans because a lack available rigorous data (eg, attendance numbers for a given event) is a barrier to advancing the science underpinning MG health.

Building for the Future

The post-event medical reporting template will continue to evolve. The next phase of this project will involve seeking input from the international MG community, after clinicians and researchers have had a chance to apply the template. With regard to the data dictionary, there should be a plan for constant evolution and updating.Reference Linnarsson and Wigertz72

Limitations

The template presented in this paper has not yet been vetted by the international MG medicine community. It is the hope of the authors that the template will be in constant evolution in the next decade, becoming more usable and being refined as the understanding of events, and the health outcomes of events, becomes more sophisticated.

The authors look forward to collaborating with colleagues with the goal of improving the current version (1.0).

Conclusions

The goal of this project was to create a lean, practical, efficient, and effective post-event medical reporting template. The authors of this paper propose moving toward a future state for post-event medical case reporting. That future state will, at a minimum, involve standardization of data collection and analysis. The development of such a reporting template is consistent with the goal of improving data quality and allowing comparison between and among events.

The proposed template will standardize the reporting of 25 essential variables. An accompanying data dictionary provides background for each of the essential variables. Of note, this template will develop over time, with input from the international MG community. In the future, additional groups of variables may be helpful as “overlays,” depending on the event category and type, and could be developed in the future.

Conflicts of interest

Turris is a shareholder with a medical services company that provides health care services for mass gatherings. Rabb, Chasmar, Ranse, Hutton, and Callaghan have no Conflicts of Interest to declare. Munn is the medical director for an annual major music festival and provides volunteer and paid services working as a director and clinician at other events. Lund is the medical director and a shareholder of a medical services company that provides health care services for mass gatherings. All the authors take on both volunteer and paid roles providing medical services at mass gatherings. None of the authors received income for this project, which is unfunded.