In recent years, women's numerical representation has been increasing in legislatures across established democracies. This has raised significant questions about what women bring to legislatures and how their contributions may be different from those of male colleagues. Studies thus far have concentrated primarily on differences in legislative voting (e.g., Swers Reference Swers2002) or outputs (e.g., Volden and Wiseman Reference Volden and Wiseman2014). Our research contributes to a distinct but associated body of literature that examines the impact women have on the process of how politics is done (e.g., Lawless, Theriault, and Guthrie Reference Lawless, Theriault and Guthrie2018). This literature has asked a number of questions, including whether women are more collaborative, lead in different ways, or have different communication styles. It is the last of these three questions that we examine: whether there are differences in men's and women's communication styles. In this article, we investigate communication styles in the context of parliamentary speechmaking in the U.K. House of Commons. Speechmaking is an important setting for analysis, as it has implications for how policies are discussed and informed, how the public engages with political elites, and how representation is carried out.

So far, the evidence supporting the idea of gendered differences in political communication styles has come primarily from testimonies of politicians themselves (e.g., Bochel and Briggs Reference Bochel and Briggs2000; Childs Reference Childs2004b; Tolleson-Rinehart Reference Tolleson-Rinehart and Carroll2001). In these studies, there is an emerging view that women evidence their arguments differently (Childs Reference Childs2004a), have more concrete orientations when discussing policies and politics (Bochel and Briggs Reference Bochel and Briggs2000), and are less adversarial and aggressive than men (Sones, Moran, and Lovenduski Reference Sones, Moran and Lovenduski2005). Thus far, however, this view has been based primarily on self-perceptions and has not been empirically tested using observational data, which we use here. Further, the limited number of studies measuring communication style have used a somewhat narrow conceptualization of it.

We advance this literature by testing for three dimensions of communication style, thereby providing a more systematic approach to studying gendered speech behavior. Specifically, we conduct an in-depth content analysis of almost 200 parliamentary speeches between 1997 and 2016 on three policy areas—education, immigration, and welfare. With the results from the content analysis, we then carry out multivariate ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses with fixed effects in which we account for debate- and individual-level determinants of style (years in Parliament, party, and government or opposition status).

While we find overlaps in gendered communication style, our study presents compelling evidence of a number of differences: women make greater use of personal experience when evidencing arguments, provide a more concrete orientation to the discussion of issues and policies, and are less adversarial. These findings have important implications for the institutional and democratic value that women's styles bring to Parliament.

First, we find that women use personal and anecdotal experience to a greater extent when evidencing arguments. The way politicians convincingly present and evidence their arguments ultimately determines how others—both the public and fellow legislators—engage with these arguments and how persuasive they will be. Studies in a number of fields have shown that arguments based on experience are necessary to complement fact-based arguments to achieve successful engagement with policy (Freiberg and Carson Reference Freiberg and Carson2010; Welch Reference Welch1997). The more traditional form of fact-based arguments may appeal to bureaucrats and politicians; however, when used in isolation, these arguments fail to resonate with the public. For engagement to be achieved, both fact-based and experience-based arguments need to be used together, to appeal to both the public and politicians. In our study, we present evidence that women use personal experience three times as much as men. Therefore, women's argumentative styles may be both more engaging and effective.

Second, we find indications that men and women bring different focuses to policy discussion. Our findings show that women take a more concrete approach and orient the discussion to consider the effects of these policies on specific groups and individuals in society, such as single mothers, rural families, or disabled individuals. In contrast, we find that men consider the effects of policies in a more abstract manner, instead considering how bigger issues will be impacted, such as the economy, the environment, or the state. This has important implications for how issues are presented in legislative debates. Women and men therefore bring different focuses to the discussion of policies; women contribute a more individual and personal focus and, in doing so, offer a different perspective to debate.

Finally, we examine gendered differences in adversarial language. Such behavior has been shown to be unpopular with the public (Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2017; Hansard Society Reference Society2014) and relatively unpersuasive as an argumentative technique (Blumenau and Lauderdale Reference Blumenau and Lauderdale2020). Our research design allows us to say that women use adversarial language at a much lower rate (50%) than their male colleagues. That women engage less in this behavior has important implications—women's approach to speechmaking may offer a welcome change to the kinds of parliamentary behavior the public finds dissatisfying and disengaging.

GENDERED PARLIAMENTARY STYLES

By far the most researched area in the gender and politics literature has dealt with how women's numerical presence in legislatures—their descriptive representation—relates to the articulation of women's interests, perspectives, and policy priorities—their substantive representation (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967; Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2009). These studies have taken a range of approaches, such as whether women are more likely to vote for women's issue bills (e.g., Swers Reference Swers2002), raise women's concerns in parliamentary questions (e.g., Bird Reference Bird2005), and have different attitudes and policy priorities (e.g., Lovenduski and Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris2003). In addition to the claim that men and women speak systematically about different political issues (e.g., Catalano Reference Catalano2009), another dimension on which men and women are said to differ is with regard to their political communication styles (e.g., Dietrich, Hayes, and O'Brien Reference Dietrich, Hayes and O'Brien2019). It is the latter of these that we focus on here.

Why are men and women said to exhibit different styles in political settings? Gender role theory argues that individuals are categorized into men and women based on biological (sex) differences (West and Zimmerman Reference West and Zimmerman1987). This categorization goes hand in hand with beliefs and expectations about the qualities or behavioral tendencies believed to be desirable for each sex (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). Behavioral expectations are eventually internalized as a result of many small but cumulative factors that men and women experience through socialization. Consequently, while we do not believe there is such a thing as a biologically determined “feminine” or “masculine” style, there may be differences in how men and women “do politics” that result from the process of gendered socialization. With regard to gendered styles in institutions such as legislatures, a vast body of literature suggests that the gendered nature of institutions can interact with men's and women's behavior (see, e.g., Krook and Mackay Reference Krook and Mackay2011; Puwar Reference Puwar2004). Institutions traditionally dominated by men will re-create norms and practices that perpetuate a hegemonic masculinity. In this way, institutions are “far from neutral” in their adaptation to female legislators (Childs and Webb Reference Childs and Webb2012, 32). Therefore, it is possible that the institution itself may impact men's and women's adoption of distinct communication styles.

In practice, do men and women have different political styles? Studies investigating men's and women's styles have primarily taken two approaches: (1) interviews with politicians regarding their perceptions of and claims about gendered styles and (2) studies that have measured differences in political style by observing legislator behavior. The first group of studies dominates the literature. Legislators interviewed in a wide range of parliaments (e.g., Blair and Stanley Reference Blair and Stanley1991 on the United States; Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup1988 on the Nordic countries; Thelander Reference Thelander1986 on Sweden), and in Westminster in particular (Bochel and Briggs Reference Bochel and Briggs2000; Childs Reference Childs2004b; Sones, Moran, and Lovenduski Reference Sones, Moran and Lovenduski2005), claim that women and men take different approaches in their debating styles. Overall, in many of the interview-based studies, it is believed that women “do politics” differently than men. Emerging from these studies are claims that women do less “standing up and shouting” and are less “combative and aggressive” (Childs Reference Childs2004a; Tolleson-Rinehart Reference Tolleson-Rinehart and Carroll2001), orient the discussion of issues in less abstract ways (Bochel and Briggs Reference Bochel and Briggs2000), and put greater emphasis on collaboration and working together (Sones, Moran, and Lovenduski Reference Sones, Moran and Lovenduski2005). These studies of perceptions say something about women's understanding of themselves in parliament, but they suffer from the limitation that they do not actually observe legislator behavior. Furthermore, it is quite possible that these women's claims may be subject to social desirability bias and the intention of projecting a more favorable image of their own behavior and that of their female colleagues. Therefore, our primary contribution is to take these testimonies and examine the styles of both women and men to establish whether differences are actually observable in legislative speechmaking.

The second group of studies, those measuring style in parliaments, is more limited than the interview-based studies. Thelander (Reference Thelander1986), Gomard and Krogstad (Reference Gomard and Krogstad2001), and Karvonen, Djupsund, and Carlson (Reference Karvonen, Djupsund, Carlson, Karvonen and Selle1995) studied gendered styles in the Nordic countries. Thelander (Reference Thelander1986) focused on linguistic complexities and the use of official language and found few differences between men's and women's language use. Gomard and Krogstad (Reference Gomard and Krogstad2001) and Karvonen, Djupsund, and Carlson (Reference Karvonen, Djupsund, Carlson, Karvonen and Selle1995) both also studied linguistic differences, such as the use of metaphors, pronouns, arguments for or against policies, and propaganda techniques. Both studies found some small differences—for example, Karvonen, Djupsund, and Carlson (Reference Karvonen, Djupsund, Carlson, Karvonen and Selle1995) found that women had more “concrete” and community orientations, and Gomard and Krogstad (Reference Gomard and Krogstad2001) found that women made more frequent use of the pronoun we, whereas men more frequently used I. Overall, however, the Nordic-based studies found limited evidence of gendered differences. However, this may be somewhat unsurprising in countries known for an overall more consensual and female-friendly style of politics, alongside greater gender equality beyond political institutions. Further, these studies focus on specific linguistic differences and do not examine some of the more prominent differences emergent in the interview-based studies, such as women being less adversarial.

Other studies have looked outside the Nordic countries and found greater evidence for gendered differences. Grey (Reference Grey2002) studied the New Zealand parliament between 1975 and 1999 by examining the number of lines of debate taken up by interruptions, personal attacks, and interjections. She found that female politicians made fewer personal attacks and interrupted less often than their male counterparts. Kathlene (Reference Kathlene1994) studied floor appointments in U.S. state legislative committee hearings and found that men spoke longer, took more turns than women, and made and received more interruptions. In the United Kingdom, Shaw (Reference Shaw2000) used discourse analysis to investigate styles and also found that men made more interruptions. Studies outside the Nordic countries, therefore, have been more successful in identifying gendered differences in legislator style. Nonetheless, we hope to make further contributions to this literature by testing a wider range of styles. Existing studies are limited in that they do not test many of the dimensions of style raised in the interview-based studies, or they test for only a single type of style. We build upon this literature by testing for the presence of three stylistic indicators, presenting a more holistic approach.

The three indicators that we measure are argumentation, orientation, and adversarial language. Each will be introduced in turn. Styles can be operationalized in a number of ways, and we do not claim here to present an exhaustive conceptualization of legislator style. However, we select these indicators as they occur most frequently in the interview-based studies and are directly measurable in legislative speechmaking.

Our first measure of style examines how women and men evidence their arguments. It is proposed that when evidencing arguments, women have a greater tendency to use anecdotal and personal experiences (Broughton and Palmieri Reference Broughton and Palmieri1999; Dunaway et al. Reference Dunaway, Lawrence, Rose and Weber2013), emphasizing “lived experience” (Blankenship and Robson Reference Blankenship and Robson1995, 359). In contrast, men are said to avoid personal consideration and instead rely on “empirical evidence,” “statistics” (Mattei Reference Mattei1998, 448), “scientific research,” and “back[ing] everything up with figures” (Childs Reference Childs2004b, 180). Therefore, as our first dimension of style, we investigate the evidence base for the claims that women have a greater tendency to use personal and anecdotal experience, whereas men focus more on facts and numbers.

Our second dimension of style examines women's and men's different orientations and approaches to issues and policy making. While men are said to tend toward a global and abstract perspective on policies, issues, and discussion, women are said to take a concrete approach (Dow and Tonn Reference Dow and Tonn1993). When examining issues, the women in the interview-based studies argue that they do not “want to know global sums, they want to know that every primary school gets between three and nine thousand pounds,” and therefore they are said to apply arguments to “real people” (Childs Reference Childs2004b, 184). Karvonen, Djupsund, and Carlson (Reference Karvonen, Djupsund, Carlson, Karvonen and Selle1995) developed a measure of three kinds of policy and issue orientations. The purpose was to examine who the recipients and beneficiaries of policies and politics were and whose problems politicians attempted to resolve. They argue that women's language seeks to “identify the person's concerned,” whereas men employ “objective expressions which avoid personal considerations” (Karvonen, Djupsund, and Carlson Reference Karvonen, Djupsund, Carlson, Karvonen and Selle1995, 346). Women are said to make greater use of “concrete” and “mixed” orientations and refer to specific groups and individuals, such as “single mothers,” “students,” or “low-income families.” Men are said to make greater use of “abstract” orientations and refer to issues such as “the system,” “the state,” or “the economy.” We adopt Karvonen, Djupsund, and Carlson's measures and classifications as a guide for coding. We therefore investigate whether women are more likely to orient their discussion of policies and politics to concrete and specific groups and people, whereas men orient their discussion of policies and politics in terms of abstract issues.

Our final measure of style, and perhaps the most widely acknowledged, is that women are said to be less adversarial and aggressive (Kathlene Reference Kathlene1994), a dimension that captures behavior such as insulting others or engaging in political point-scoring. Many of the women in the interview-based studies were critical of this kind of behavior, seeing it as “childish” and “negatively perceived by the electorate” (Childs Reference Childs2004a, 6); instead, women claim that they are “more willing to listen to the other side” (Bochel and Briggs Reference Bochel and Briggs2000, 66). Adversarial behavior is connected to the idea that women interrupt others less and are interrupted more than men, which has become well established in both observational (Anderson and Leaper Reference Anderson and Leaper1998) and experimental studies (Karpowitz and Mendelberg Reference Karpowitz and Mendelberg2014; Mendelberg, Karpowitz, and Goedert Reference Mendelberg, Karpowitz and Goedert2013). We therefore investigate the extent to which men are more adversarial in their legislative speechmaking than women.

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

The U.K. House of Commons

Our case for this study is the House of Commons, the lower chamber of the U.K. Parliament. The Commons is a classic majoritarian legislature, typically with a single governing party and one main opposition party (Lijphart Reference Lijphart2012). We focus our attention on three parliamentary sessions: 1997–98, 2005–06, and 2015–16. Each of these was the first session following a general election. The 1997–98 session immediately followed the 1997 general election, which saw the election of Tony Blair's Labour government; the 2005–06 session immediately followed the 2005 general election, which saw the reelection of Blair's Labour government; and the 2015–16 session followed the 2015 general election, which saw the election of David Cameron's Conservative government. Each of these elections resulted in single-party majority governments. The percentages of votes won by the Conservative and Labour parties and the corresponding parliamentary seat compositions are reported in Table 1. Our sample includes periods of both Labour and Conservative government, allowing us to examine the behavior of men and women on the government and opposition sides.

Table 1. Vote shares and seat composition, 1997, 2005, and 2015 general elections

* Indicates the party won the election and held a majority of parliamentary seats.

Data and Sample

We select three parliamentary sessions (1997–98, 2005–06, and 2015–16) so as to provide more than a snapshot of communication styles and to ensure that they are not determined by a particular contextual circumstance, hence improving the validity and robustness of our results.Footnote 1 Therefore, we select three sessions that are relatively equally spaced in time.

We take 1997 as the beginning of our sample period, for two reasons. First, the 1997 election witnessed the doubling of the number of female Members of Parliament (MPs). This not only marks an important milestone in British politics but also provides data limitations for studying earlier periods. Following the 1992 general election, there were only 60 female MPs (9.2% of seats). Comparatively, in the sessions we study, there were 120 (18.2% of seats) in 1997, 128 (20% of seats) in 2005, and 191 (29% of seats) in 2015. Therefore, given our selection of legislation, there were not enough women in the debates in 1992 to say anything conclusive about gendered differences; hence, we take 1997 as the start of our sample. Second, a number of women interviewed were first elected in 1997 (see, e.g., Childs Reference Childs2004a), and this enables us to more directly test their claims.

Studying the U.K. Parliament in relation to gender styles is particularly interesting. First, it is a legislature that is widely associated with a highly masculinized political culture. Feminist critics argue that the Commons institutionalizes the predominance of particular masculinities, and it is often spoken about as aggressive and adversarial (Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2005). Second, the aforementioned increase in the number of women representatives over the past two decades—from 18.2% of seats in 1997 to 33.9% of seats in 2020—allows for an investigation of how styles change as numbers increase (Inter-Parliamentary Union 2020). Therefore, we select the Commons as our case because of both the commonly perceived hypermasculinized culture and the recent growth in women's numbers.

Within the three parliamentary sessions we study, we investigate politicians’ speeches in legislative debates—the second reading stage—as our source of data. During second readings, the government minister, spokesperson, or MP responsible for the legislation opens the debate by introducing the bill, the official opposition responds, and the debate continues with opposition parties and backbench MPs voicing their opinions on the bill (for a full explanation of the legislative process, see Russell and Gover Reference Russell and Gover2017). Second reading debates are the first opportunity for MPs to debate bills and for the general principles of each bill to be discussed. Therefore, there is substantive debate on the floor of the House. Legislation debates take up a large proportion of parliamentary time, estimated at 37% of the Commons’ sitting hours (Institute for Government 2018, 26), and therefore they are an appropriate setting for analysis. Furthermore, legislative debates are a useful avenue for investigating legislator style specifically, for two reasons. First, these debates typically receive less time regulation than other debates. Second, they are arguably less high profile and in the public eye than other parliamentary events, such as Prime Minister's Questions (Hansard Society Reference Society2014). Therefore, we believe the lack of time limits and lower profile increases individual MPs’ freedom of behavior, giving us a more accurate investigation into styles.

We select debates on bills on similar policy topics in each of our three time periods, resulting in the examination of nine debates overall. The topics are education, immigration, and welfare. For education, we study the Education (Schools) Act (1997), the Education and Inspections Act (2006), and the Education and Adoption Act (2016). For immigration, we study the Immigration and Asylum Act (1999), the Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act (2006), and the Immigration Act (2016). Finally, for welfare, we study the Social Security Act (1998), the Welfare Reform Act (2007), and the Welfare Reform and Work Act (2016).Footnote 2

We attempt to match bills on the same topics, but we also select only bills introduced by the government and bills that have become law. This again allows us to hold constant as many debate-level factors as possible. We select the topics of education, immigration, and welfare to provide a broader scope of gendered styles. Previous studies have noted that topic may influence legislator behavior (Catalano Reference Catalano2009). It is for this reason that the 2001–02 and 2010–12 sessions are excluded from the analysis, as we were not able to find bills that matched our three topic areas. We believe that matching on the topic is particularly important, given the wealth of literature showing that men and women systematically participate in different kinds of debates (e.g., Piscopo Reference Piscopo2011) and take ownership of different issues (e.g., Catalano Reference Catalano2009; Krook and O'Brien Reference Krook and O'Brien2012; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006). Topic may drive styles; therefore, the inclusion of different topics would weaken our analysis.

Finally, we make two further design decisions to focus our attention unambiguously on gendered differences. First, we remove all maiden speeches from our sample, as they are deliberately noncontentious, which may be problematic when studying adversarial language. Second, we examine only the speeches of backbench MPs. While this may limit the breadth of our analysis to some extent, we expect that the behavior of frontbenchers is substantively different from that of backbenchers. Backbenchers are awarded more freedom of behavior in their speeches, which might affect the kinds of arguments they make. Our selection process resulted in a final sample of 196 speeches: 40 in 1997–98, 68 in 2005–06, and 88 in 2015–16.

Coding Scheme and Protocol

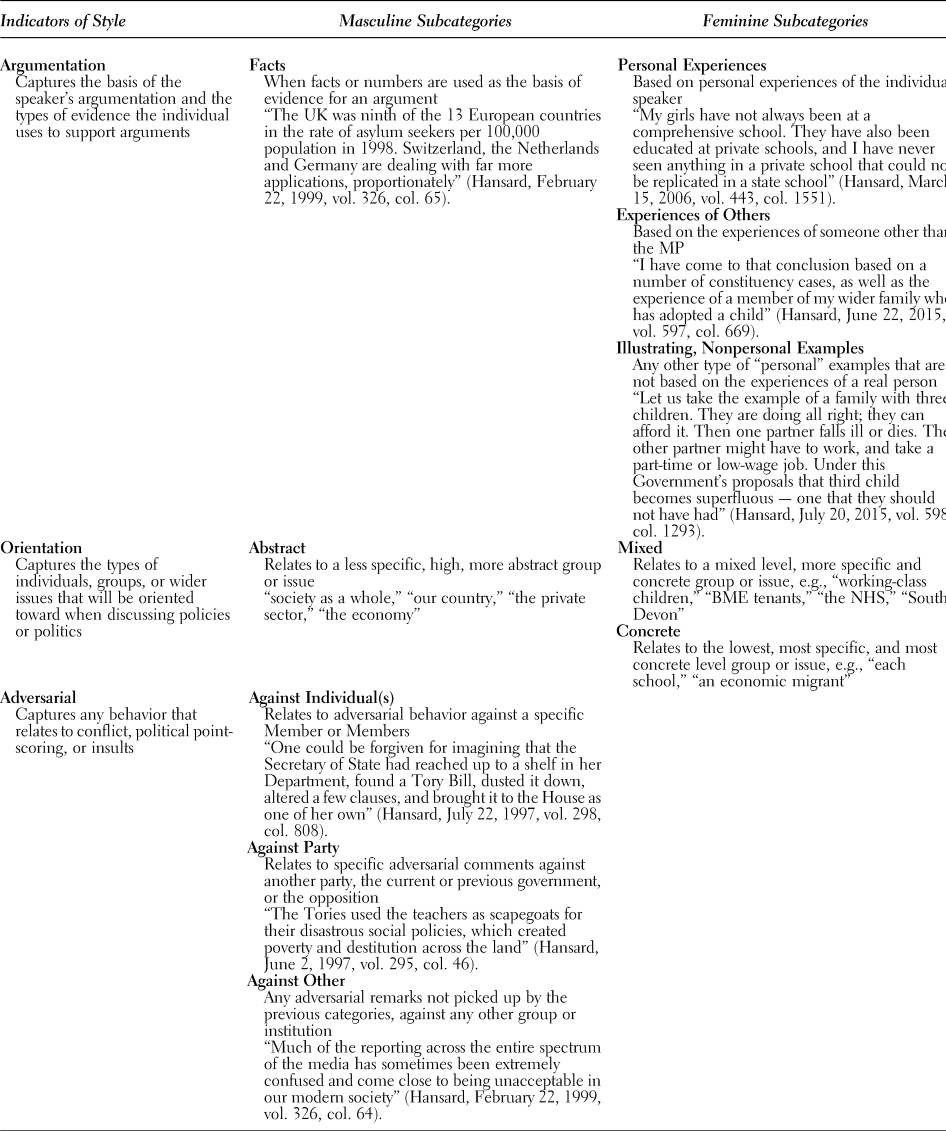

Before turning to the coding process, we first present our coding scheme with textual examples in Table 2. Our coding scheme is divided into “masculine” and “feminine” subcategories based on the literature's categorizations of gendered differences.

Table 2. Coding scheme and textual examples

With the scheme in hand, all coding was done qualitatively using NVivo software. Individual MPs’ speeches were removed from the nine main debates and broken down into individual units to be coded. For the argumentation and adversarial categories, we present the percentage of characters in each individual speech (unit) that contain a single code, a measure that is generated by NVivo.Footnote 3 For example, a speech receiving 10.5% for the adversarial category means that of all the characters in that MP's speech, 10.5% of the characters were classified by our coding scheme as containing adversarial language. We present the percentage of characters and not the raw numbers, as the speeches vary in length. For example, the average speech was 86 lines, the longest was 311 lines, and the shortest was 24 lines. Therefore, aggregated percentages are a more comparable measure across speeches.Footnote 4

By examining the proportions of speeches rather than raw counts, we look beyond the fact that men and women contribute at different rates, something that has been well documented (e.g., Bäck, Debus, and Müller Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014; Blumenau Reference Blumenau2019) and would cause problems here. If we only examined counts, and men speak significantly more in general, we would only pick up those differences across all of our categories. Instead, taking the percentage measures overcomes this, because we are examining the relative degree to which men's and women's speeches are marked by these styles. Therefore, we use percentage coverage. To conduct the analysis, percentages for each individual speech by men and women are used as observations. For the orientation category, we do not use the percentage measure, but rather individual counts of references to concrete, abstract, and mixed groups, a measure that is also generated by NVivo. This is because only the group (e.g., single mothers) or issue (e.g., the economy) was coded and not the entire sentence. To show comparability across our three orientation measures, the counts for each category are presented as a proportion of all counts for orientation (see Table 3).Footnote 5

Table 3. Differences in means between men and women for each stylistic category

Note: Measures are the average percentage of characters in a parliamentary speech that contains a code. For argumentation and adversarial, the aggregate measure is presented. For orientation, the percentage for each subcategory is in relation to the total number of occurrences for the orientation code.

The primary virtue of our qualitative approach to coding is that it offers a more in-depth and nuanced analysis than most quantitative text analysis approaches. For example, quantitative approaches to measuring adversarial behavior are only able to capture this in regard to interruptions, whereas our qualitative investigation allows us to capture a subtler kind of parliamentary insult that would be missed by automated approaches, such as sarcasm. To ensure reliability, we anonymized the speeches before coding by removing names and any other individual-level identifier. This alleviates potential coder bias when interpreting and classifying the speeches. To carry out the coding, speeches were removed from the main text of the debate into individual coding units (each MP's speech). This removed the broader political context and further ensured that the speaker's gender could not be inferred from the wider debate.

Methodology

With our qualitative coding of the 196 speeches in hand, we now explain our modeling approaches. First, we carry out a bivariate investigation into men's and women's speech styles. This tells us the average difference between men and women for each of the speech styles, the results of which are presented in Table 3. Second, gender is clearly not the only important difference between men and women; rather, there are many other differences between individuals that may also influence legislator style. Therefore, in a second step, we estimate multivariate regression analyses to account for these differences. We control for years in Parliament, party, and government or opposition status as individual-level covariates.

Finally, in examining only individual-level factors in the multivariate regression analyses, we do not account for the fact that men and women may systematically participate in different types of debates. Therefore, it is unclear whether we are picking up individuals engaging with different topics or talking about the same topics in different ways. To alleviate this problem, we estimate fixed-effect models with debate-level intercepts, which focuses our analysis unambiguously on the differences between male and female MPs in the same debates. The results from the bivariate, multivariate, and fixed-effect OLS regression models are presented in Figure 1, and the estimates from the fixed-effects results are presented in isolation in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Results for bivariate, multivariate, and fixed-effects OLS regression models, female = 1 (coefficients, standard errors and confidence intervals).

Figure 2. Effect of female MP, fixed-effects OLS regression models, female = 1 (coefficients, standards errors and confidence intervals).

Throughout our analysis, we run separate OLS linear regressions in which each of the individual measures of style acts as our outcome variable. Based on Table 2, these are evidence based on experience and facts; abstract, mixed, and concrete orientations; and adversarial language. Our primary independent variable is female: capturing whether an MP is a man (coded 0) or woman (coded 1).

We also account for a number of individual-level factors that might influence styles. First, we include years in Parliament as a control variable (ranging from 1 to 45 years), which we calculate by subtracting the year of election from the year of the debate.Footnote 6 It is possible that MPs are socialized the longer they are in a parliamentary institution, and therefore gendered differences may decrease as years in Parliament increases. Second, we control for party, which is divided into Conservative (the reference category), Labour, and other parties.Footnote 7 Party has been highlighted by a number of studies as an important difference within types of men and types of women. The Labour Party has historically had a higher proportion of women in the party, whereas the Conservatives have been regarded as less women-friendly than Labour (Childs and Webb Reference Childs and Webb2012). Third, we include opposition as our final individual-level covariate. This captures whether an MP is part of the government (coded 0) or opposition (coded 1). Opposition parties might be expected to engage in more adversarial behavior toward the government; indeed, Shaw (Reference Shaw2000) found that opposition parties asked the most adversarial questions.

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

We now present the results of our analysis. Table 3 shows the difference in means for men and women for each of our stylistic categories (bivariate results). For all categories, there is an observable difference between men's and women's styles. For argumentation, we find that men do refer to experience, but women use this kind of evidence three times as often as men on average. The same pattern is not found for the other subcategory of argumentation: facts. Men and women refer to facts to a broadly similar degree, with women referring to facts marginally more than men on average (11.5% compared with 9.8%).

Turning to orientation, we again find evidence of gendered differences. Men refer to abstract groups or issues more frequently than women (30.7% compared with 21.1%), and women refer to concrete groups or issues more frequently than men (9.1% compared with 6.2%). Women also refer to mixed groups or issues marginally more than men (69.7% compared with 63%). Finally, the bivariate results also show a difference in use of adversarial language: men use this language more than twice as often as women (10.7% compared with 4.2%).

Therefore, for all three of our stylistic dimensions—argumentation, orientation, and adversarial language—the bivariate results suggest that there are observable differences in men's and women's speech styles. As there are a number of other important individual-level factors that may influence legislator style, we now turn to the results from the multivariate and fixed-effect models.

Figure 1 presents the gender coefficients (β), standard errors, and confidence intervals for the bivariate, multivariate, and the debate fixed-effects models. It is worth noting immediately that despite the inclusion of debate fixed effects and a number of individual-level covariates (years in Parliament, party, and government or opposition status), the coefficients and confidence intervals remain fairly constant across the three model types. This suggests that while other individual-level factors may influence legislator style, gender is the key predictor of speech style in our models. Figure 2 presents the coefficients (β), standard errors, and confidence intervals specifically from the fixed-effect regressions, the most conservative models we estimate (see Table A1 in Appendix C for the full fixed-effect regression output). The results of these models allow us to focus unambiguously on the differences between men and women within the same debates while controlling for years in Parliament, party, and government or opposition status.

For argumentation, experience is positive and significant when controlling for all other factors (p = .001).Footnote 8 This includes the use of personal experiences: “I am the daughter of economic migrants, and I take exception to the tone sometimes used to describe such people” (Hansard, February 22, 1999, vol. 326, col. 92). This can also include the experience of others: “This afternoon, a constituent telephoned me because his nine-year-old nephew had come to visit him from South Africa. The nephew is of Indian origin and his name is Yash Patel. He arrived at terminal 1 of Heathrow airport and was refused admission because the immigration officers believed that there was not a sufficient program of activities for the nine-year-old during his visit to his uncle” (Hansard, July 5, 2005, vol. 436, col. 223). This also includes illustrating, nonpersonal examples: “Five years can be a very long time in the life of a child. If a young child has come to this country as part of a family of refugees, is at school here, making friends and doing well in the education system, as often happens with refugees, it can be extremely traumatic for them to be told that they have to return.” (Hansard, July 5, 2005, vol. 436, col. 248). Our results suggest that while alleviating debate-level covariates and controlling for years in Parliament, party, and government or opposition status, women are three times more likely to use experience when evidencing arguments. Interestingly, the coefficient for female is the only significant result in the model. Therefore, we find no differences in the use of experience for years in Parliament, party, or government or opposition status.

However, for the other subcategory—facts—the model reveals no significant gendered differences. Men and women use facts when evidencing their arguments to a similar degree, for example: “Since 1997, Labour's macro-economic policies, support for flexible labour markets and welfare to work incentives have guaranteed faster growth in this country than across the EU as a whole, created 2.5 million additional jobs and reduced employment to less than 1 million” (Hansard, July 20, 2015, vol. 598, col. 1319). Therefore, as with the bivariate results, we uncover no evidence to suggest men make greater reference to fact-based arguments than women. Similarly, as with experience, there are no significant effects for any of the other covariates.

Turning to orientation, there are significant relationships with the gender of the speaker both for abstract (p = .01) and concrete (p = .01) orientations. Abstract orientation is negatively correlated with being female, whereas concrete orientation is significantly positively correlated with being female. Therefore, as with the bivariate results, while men and women refer to both abstract and concrete orientations, we find men dedicate more of their discussion of issues or problems to abstract issues such as the economy, the environment, or the deficit. By contrast, women dedicate more of their discussion of issues or problems to specific and concrete groups, such as individual schools.

Contrary to the other stylistic indicators, we see a number of significant effects for the individual-level covariates. For years in Parliament, we see that as the number of years increases, there is a decrease in the use of abstract language (p = .05) and an increase in the amount of concrete language (p = .001). However, it is worth acknowledging that the effect sizes are small for both: a one-unit increase in years in Parliament results in a decrease of just 0.31% for abstract language and an increase of just 0.26% for concrete language. Party, too, returns significant effects. Compared with Conservatives, Labour MPs use significantly less abstract language (p = .01). This suggests that conditional on debate and individual-level characteristics, Conservative and Labour MPs’ speeches differ by approximately 8.76% with respect to abstract language. However, there is no corresponding significant result for concrete language. Finally, we also find that members of the opposition use less abstract language than members of the government party: the difference between opposition and government MPs speeches is approximately 5.90% (p = .05). Therefore, for orientation, we uncover not only differences between men and women, but further differences between types of MPs: years in Parliament, party, and government or opposition status all matter.

For our final style type—adversarial language—we find evidence of gendered differences: the gender coefficient is negative and significant (p = .001). Therefore, conditional on debate- and individual-level factors, male and female speeches differ on this dimension by on average 6.15%.Footnote 9 To give an example of variation in the data, the most extreme case of adversarial language we found was by a male MP, in which 58.5% of the characters in a speech were dedicated to adversarial remarks. However, some individual speeches contained no adversarial language. Adversarial statements were mostly against party, for example: “The Tories used the teachers as scapegoats for their disastrous social policies, which created poverty and destitution across the land” (Hansard, June 22, 1997, vol. 295, col. 46). But adversarial statements were also made against individuals, such as an MP's statement that certain individuals had revealed their “profound ignorance of the social security system” (Hansard, July 22, 1997, vol. 298, col. 827). This finding strongly supports the existing perception and behavior studies. The men in the sample insult other MPs and parties more often than women. Therefore, when accounting for debate fixed effects, years in Parliament, party, and government or opposition status, men dedicate more than twice as much time to insults and adversarial remarks than their female counterparts. The other parties coefficient is also significant, showing a positive and significant effect (p = .05) on being adversarial, indicating that MPs belonging to parties other than Labour and the Conservatives are more adversarial. This is perhaps intuitive, as third parties may be expected to be more adversarial overall; one might expect the role of a third party to critique both the government and opposition parties. Furthermore, third parties have fewer policy responsibilities having not previously been part of the government, which facilitates a more critical style of communication.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Our findings present compelling evidence that men and women take different approaches when engaging in political discussion. Therefore, in the U.K. House of Commons at least, there are significant differences in the legislative speeches of male and female MPs. With these findings, we provide new data and an empirical evidence base that support the testimonies of legislators and findings from earlier studies. In particular, our findings relating to argumentation show empirical support for the testimonies of women in the interview-based studies, indicating that women are more likely to evidence their arguments with anecdotes and lived experience and to examine issues “from the personal perspective” (Childs Reference Childs2004b, 184). Likewise, our findings relating to orientation support the idea that women refer more often to concrete groups and issues, whereas men refer more often to abstract ones. Finally, we present evidence for the claim that female MPs use less adversarial and aggressive language than male MPs.

Our findings present persuasive evidence to support the idea that there are differences in the styles of men's and women's political communication. We contribute to the literature in three key ways. First, our study is, to our knowledge, the first to directly measure the testimonies of the women in the interview-based studies. In doing so, it provides support for the women's claims and demonstrates through careful measurement that perceptions correspond with behavior in practice. Second, we contribute to the studies that have measured language and behavior by examining a broader range of indicators and offering a more holistic approach to answering these questions. Third, we take seriously that differences are unlikely to be driven by gender alone. Rather, other individual-level factors and the debate context may matter, too. To account for these, we examine gender conditional on other debate- and speaker-level characteristics: years in Parliament, party, and government or opposition status. While we find the gender results to be most compelling, we also uncover differences in our three covariates for some, although not all, of the style dimensions.

Notably, though, we do not find support for all of the defined aspects of style. Some of the subcategories did not reveal any significant differences between men and women. Women do refer to personal experience three times more when evidencing their arguments; however, men do not base their arguments on facts more. Instead, we found that men and women used facts to an equivalent degree. This is an important finding. Women's equivalent use of facts contrasts the expectations of the stereotypes literature that women use only their own lived experiences when making arguments (Blankenship and Robson Reference Blankenship and Robson1995; Hannah and Murachver Reference Hannah and Murachver2007). Instead, we show there is no evidence base for these claims, and there are no gendered differences in the use of facts within our sample period. Furthermore, not only do men not use fact-based arguments more than women, they use less experience-based argumentation. Therefore, within the kinds of evidence we examine, men use neither to a greater degree. Together, fact-based and experience-based argumentation makes up just 12.8% of the average male MP's speech. Presumably, male legislators are using some form of evidence to support their arguments. This raises the question of what are these other kinds of evidence that men use to support their arguments? The purpose of our study was to test the claims of the interview-based studies; hence, a further investigation into evidence types is beyond the scope of our work. Nonetheless, future research could use a more refined coding scheme, and investigate other types of argumentation, and the gendered differences within this.

Overall, we present evidence to support the claim that men and women do differ in their political speech styles. In this way, we enhance existing knowledge about how our elected representatives engage in political discussion. Nonetheless, while we present compelling evidence of differences, there are, of course, many similarities in how male and female MPs communicate. For example, while men are more abstract in their orientations (30.7%), women still use abstract orientations regularly (21.1%)—in fact, more so than they use concrete orientations (9.1%). Therefore, although there are differences between genders, there are many overlaps, too. Furthermore, even though we find gender to be the biggest predictor of style, we uncover a number of other factors that may influence aspects of style: the number of years an MP has been in Parliament, their party, and whether they are part of the government or opposition.

While we account for a range of individual-level factors that may influence style, there are numerous other things we do not examine. For example, seniority or leadership status may also affect style. A recent study by Blumenau (Reference Blumenau2019) on roles models in parliamentary debates in the British House of Commons investigates how the presence of female ministers increases the participation and influence of female backbenchers. The study finds the presence of a role-model effect: female ministers increase the participation of female MPs in relevant debates by approximately one quarter over the level of female participation under male ministers. Similarly, Barnes (Reference Barnes2016) examines gendered patterns of collaboration in Argentine state legislatures. Barnes hypothesizes that senior women would collaborate more than junior women both as a result of having developed more networks over time, and as a tool to help newcomers. The study finds support for this: senior women collaborate at higher rates. Both of these studies present compelling evidence that not just a legislator's gender influences behavior, but other factors (seniority and leadership) matter also. It is not the purpose of our study to investigate how institutional or compositional factors might mitigate gender differences. However, future work could fruitfully investigate how context matters for the expression of gendered styles.

Along a similar vein, we study a very specific context for political styles: MPs’ speeches within parliamentary debates in the U.K. House of Commons. While this allows us to investigate speech behavior in this instance, we are unable to say how these findings generalize beyond parliamentary debates or the U.K. Parliament more broadly. The recording of debates in Hansard is “merely the tip of the iceberg” for what men and women do in their roles as MPs (Childs Reference Childs2004b, 184). Therefore, we do not attempt to make statements about other kinds of legislator style, such as campaigning behavior, discussion in select committees, nor behind the scenes collaboration or networking. Furthermore, we examine only the U.K. House of Commons. It is beyond the scope of this study to make comparative statements about how political styles might manifest in other settings. Nonetheless, future research could build on these findings to investigate how things may differ in other institutions and, in doing so, how context might affect style.

In conclusion, this study pays careful attention to measuring the speeches of politicians and provides compelling evidence of gendered differences in men's and women's political styles. Our findings have important implications for how women's styles might improve public engagement with politicians, offer a different focus to discussion, and improve democratic legitimacy.

First, our findings on how women and men argue, coupled with what we know about the argumentation styles people find persuasive (e.g., Freiberg and Carson Reference Freiberg and Carson2010; Welch Reference Welch1997), suggest that perhaps women are more compelling arguers than men. We show they use experience-based and anecdotal evidence three times as much as men, furthermore they use fact-based arguments to an equivalent extent. Women therefore use a wider variety of evidence, which is convincing in many different ways. Experience-based argumentation resonates more with other legislators and the public. Fact-based argumentation is good for developing evidence-based policy. Therefore, these findings have important implications for suggesting that perhaps female MPs are simply more convincing arguers.

Second, women orient their discussion to concrete and specific individuals, while men have more abstract focuses. In doing so, women introduce a different perspective when debating legislation. Finally, women are less adversarial in their speechmaking. Therefore, women may offer a potentially more constructive approach to traditional perceptions of legislative speechmaking. Politicians engaging in political point-scoring and insults contributes to public disengagement with politics (Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2017) and has been shown to be a relatively unpersuasive argumentation technique (Blumenau and Lauderdale Reference Blumenau and Lauderdale2020). Therefore, not only might adversarial language feed into negative evaluations of political institutions, it simply may not be very persuasive as an argumentative style. An overall reduction in the aggressive nature of the Commons could have the effect of altering negative public perceptions of and engagement with Parliament (Childs Reference Childs2016), which could even enhance participation in traditional politics and encourage a more positive relationship between the public and political elites.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X20000100.