Ornamentation is essential in Irish fiddling. A “straight” version of a tune is only an abstraction—in practice, fiddlers (and other Irish instrumentalists) use extensive ornamentation, which imparts the proper crispness and crackle to the performance. This article investigates the ornamentation practice of Eileen Ivers, an Irish fiddler from the Bronx.Footnote 1 It focuses on her playing of dance tunes, especially reels, jigs, and slip jigs. Ornamentation mentioned in connection with reels applies equally to hornpipes, but in moderation. Ivers's performances of hornpipes are much more restrained and austere than her spirited style of playing reels.Footnote 2

Ornamentation is one of the major elements that gives Irish fiddling its distinctive character. Ornaments play various roles: they function as small-scale melodic diminutions, rhythmic stresses and articulations, and textural alterations.Footnote 3 What C. P. E. Bach wrote concerning them applies as well to Irish instrumental music as to eighteenth-century keyboard music:

No one disputes the need for embellishments. This is evident from the great numbers of them everywhere to be found. They are, in fact, indispensable. Consider their many uses: they connect and enliven tones and impart stress and accent; they make music pleasing and awaken our close attention. Expression is heightened by them: let a piece be sad, joyful, or otherwise, and they will lend a fitting assistance. Embellishments provide opportunities for fine performance as well as much of its subject matter. They improve mediocre compositions. Without them the best melody is empty and ineffective, the clearest content clouded.Footnote 4

I make an expedient distinction between “ornamentation” and “variation,” partly because Ivers makes a similar distinction.Footnote 5 “Ornamentation” here refers to the more or less stereotyped figures (recognized by the fiddler as such) that embellish a note, connect two notes, or substitute for a note or group of notes. Ornaments usually (excepting the slide) include notes of shorter duration than the most common rhythmic value, usually notated as an eighth note in dance music.Footnote 6 Irish musicians refer to these by name, although the names vary to some extent (for instance, “bow trill/trebling” or “grace note/cut”). Although fiddlers recognize these ornaments as conventional formulae, the technique of their execution can be very individual. Although some fiddlers are known for their idiosyncratic ornaments (Brendan Mulvihill, for instance), most Irish fiddlers share a basic core repertoire of ornaments, although the manner and frequency of usage depends on the regional/ individual style of the fiddler.Footnote 7

“Variation,” as used here, refers to freer and more extensive melodic and rhythmic changes in the basic tune.Footnote 8 These changes are not as formulaic as ornaments in the narrow sense (although they can fall into fairly common patterns), do not generally involve the quick notes of embellishments, and Irish musicians generally do not have specific names for them.

It is difficult to maintain this distinction with any rigor. In its larger sense, variation is an inclusive term. It can be taken at its most general to refer to the many different ways in which a player realizes a tune model, which is not an entity but rather a set of criteria in different parameters. Ornamentation is a type of variation consisting of formulaic embellishments that are widely used and recognized by performers, known by common names, generally include very short note values, and constitute one criterion of skillful performance among performers and listeners alike. A common way of varying a tune is to change the ornamentation.Footnote 9 Incidentally, the existence of ornamentation as an important species of variation is not universal among fiddling traditions. Most North American fiddling styles emphasize variation to a greater or lesser degree, but many do not include a repertoire of named embellishment formulae.

Terms such as “ornamentation,” “variation,” and “basic tune” can be misleading if they imply that the use of rolls, graces, etc., are optional in Irish fiddling, and that there is something concrete—i.e., the tune in its naked state—to which ornamentation (and, for that matter, variation) is then applied. This reification of the basic tune may be true conceptually for the fiddler (it is true for Ivers), but in my experience, although the degree and kind of ornamentation is variable, the tune is never played “straight” except in lessons for beginning students (and in interviews with music researchers). The “naked” tune, although it certainly has a conceptual existence, does not seem to have any actual phenomenal existence as an object of performance. Samuel Bayard sums this idea up neatly in words that are as applicable to Irish fiddling as to singing:

Often, in Irish singing, the skeletal tune is so heavily overlaid with ornamental features that it becomes hard to recognize; yet, too, it is hard to call these features (cadenza-like runs, slides, rapid shakes, grace notes of various sorts) an “overlay”—they seem to form an integral part of the melody, as well as of the style of performance.Footnote 10

Ivers is a prominent Irish fiddler from the New York area. She was born in the Bronx in 1965 of Irish parents (from County Mayo), and began studying the fiddle with Martin Mulvihill at the age of nine.Footnote 11 She won an unprecedented nine All-Ireland awards on fiddle (and one on tenor banjo), including the senior title in 1984. She was a founding member of Cherish The Ladies, was the musical star in Riverdance, and has been a featured player with such groups and artists as the Chieftains, Hall and Oates, Afrocelts, Hothouse Flowers, Luka Bloom, Patti Smith, Paula Cole, Al Di Meola, and Steve Gadd. Other bands in which she has played include Green Fields of America, Jigsaw, Chanting House, and Paddy a Go Go. Her current band is Eileen Ivers and Immigrant Soul, a fusion of Irish, African, and Caribbean styles. In addition, she has made over fifty appearances with symphony orchestras, maintains an active touring schedule, and has recorded the albums listed in the discography.Footnote 12

Trained in the rolling Kerry-Limerick style of Martin Mulvihill, she has since studied and assimilated a number of different Irish fiddling styles, and emerged with her own unique sound characterized by extreme crispness, strong rhythmic drive, and exceptional control and flexibility. She is known for experimenting with nontraditional arrangements and techniques: some of her playing falls outside the usual Irish fiddle norms—e.g., descending slides, strong syncopations and anticipations, unusual combinations of ornaments, and the exploitation of dynamic contrasts exceeding that of most Irish fiddlers, and mixing different musical styles;Footnote 13 her current band, Immigrant Soul, for instance, combines African, Caribbean, and Latin rhythms with Irish fiddling.Footnote 14 This element of fusion has led to divergent opinions among the New York Irish traditional music community about how “Irish” her playing really is. Some of this disagreement stems from the fact that her strongly individual playing departs radically from the Kerry-Limerick style in which she was trained and reflects many different influences.

In my interviews and lessons with Ivers, and at other lessons at which I was present, Ivers played exclusively in her more “traditional” manner, which seems to be her core style. When teaching, Ivers is aware of her position in the Mulvihill lineage and attempts to teach as she herself was taught. She makes a distinction between traditional playing and “freer” playing, as she remarks in my interview with her.

EI: Well, when you put a variation in a tune, I think you should really try and stick, of course, to the melody of the tune as far as the chordal structure and not go too crazy. You know, don't try and go into some weird minor thing if you're in a major tune. Some variations I hear people do just don't work, because I don't think they understand where the tune is coming from. The nicest variations complement the tune, definitely.

SS: Do you mean by variation a whole part, a whole alternate part A or part B?

EI: Oh no, just a little bar in a part.

SS: Just like changing a note sequence or something.

EI: That's all. You know, again that would be traditional to do that—we were talking more traditional. I mean, nowadays you can get into a freer thing and splice up a tune and go like nuts about it, but that's a different form of looking at Irish music. But traditionally, again, it's just taking a little bar or two and just altering the notes a little, but again around, I think, the chord of the tune makes the best variations.

Notes on the Transcriptions

Each turn through a tune is notated on a separate staff and labeled with a Roman numeral. Variants are either written out or, when the same as in a previous turn, identified by a Roman numeral.Footnote 15 Bowings are approximate. In the absence of a filmed record, it is difficult to notate bowings accurately.Footnote 16 Although I have kept to the standard practice of notating tunes in straight eighth notes, Ivers's playing of consecutive eighth notes approaches a dotted rhythm, especially in jigs. This characteristic is typical of Limerick-Kerry style.Footnote 17 In reels she places a very strong rhythmic stress on the offbeats. The following abbreviations are used in the examples.

The Ornaments

The Grace Note

I guess the simplest [ornament] is the grace note, which is just a full extra note thrown in a tune on a plain note.

—Eileen Ivers

There are two varieties of grace notes—single and double.Footnote 18 In the single grace note, the ornamented note is preceded by a higher note on the same string, executed with a quick flick of the finger. In the double grace note, the ornamented note is replaced with a three-note diminution: the original note, a note above (never below), and the original note again. The “note above” is not always the next consecutive scale-step. Ivers muses: “For the first finger grace note I like to use the third finger, because it's a stronger finger. There's no rules against it, you could use the second finger, but it's very close to the first finger, so it's a little bit awkward. You get a stronger sound of the grace note with your third finger.”

In grace notes and rolls, Ivers's fingers—especially her third finger—approach the string from the side, creating a slight left-hand pizzicato “ping” behind the pitch. Gracing an open string or first finger with the third finger is fairly common among Irish fiddlers. Example 1 gives Ivers's fingering of double grace notes on the E string. The same fingering, of course, applies to the other strings. Grace notes are initiated on the beat and are played on a single up- or down-bow stroke.

Example 1. Double grace notes.

Demonstrating with the jig “Boys of the Town,” Ivers first played the tune “totally straight” (Example 2); then she repeated the first strain, adding grace notes (Example 3). In this extremely simple pedagogical example, the grace notes are all double; embellish the tonic; articulate the initial G in the G–F-sharp–G motive; and stress the onbeat except in the upper octave, where the offbeat is stressed. As Breathnach points out, the grace note can (as here) emphasize an accented note, can separate notes of the same pitch, and can be “used also to good effect before the unaccented notes of a group, imparting a lift or skip to the music.”Footnote 19

Example 2. “Boys of the Town,” unornamented.

Example 3. “Boys of the Town” with double grace notes.

According to Ivers, of all the ornaments, grace notes are “the easiest to fit in.”

The Roll

The roll is perhaps the most ubiquitous Irish ornament, universally used except by the older generation of Donegal fiddlers;Footnote 20 these fiddlers tend to employ the bow trill where other fiddlers would use the roll.Footnote 21 Conversely, Kerry-Limerick and Sligo fiddlers tend to use more rolls than bow trills. The roll consists of five notes: the main note, upper neighbor, main note, lower neighbor, and main note. As with the grace note, the identity of the upper and lower “neighbors” depends on which finger plays the main note. Example 4 shows Ivers's fingering of rolls on the E string.

Example 4. Rolls.

Rolls are played on one bow stroke. They cannot be taken on an open string because the lower neighbor is not available without an extremely awkward string crossing. Tomás O'Canainn gives two versions of an alternative open string roll (Example 5), but Ivers does not use these.Footnote 22

Example 5. Open-string rolls from O'Canainn, Traditional Music in Ireland, 93.

Ivers lifts her fingers during rolls to produce a sharper articulation of each note. She feels that when the fingers are held down the sound is dead and lacks snap. Thus during a roll on D (third finger on the A string), while the third finger D is played, the second finger (C) is held off the fingerboard; when the fourth finger E is played, both the second and third fingers (C and D) are held off the fingerboard.

Rolls are of two types: long and short. The long roll takes up the time of a dotted quarter (if the running notes of a reel or jig are notated as eighth notes). The short roll condenses the five notes into the space of a quarter note.

In the long roll, the initial note is always the longest. Ivers usually increases her bow speed and pressure on this note, creating a crescendo into the rest of the roll. She stresses that the rhythm of the long roll distinguishes it from a grace note configuration with the same pitch sequence, in which the first note is not lengthened; Example 6 shows the double grace note and long roll. In the first measure of the “Boys of the Town,” the first group of three eighth notes (G–F-sharp–G) can be incorporated into a roll on G, creating the pitch sequence G–A–G–F-sharp–G.Footnote 23 Alternatively, the initial G can be embellished with a double grace note (as in Example 3), which, followed by the next two notes of the tune (F-sharp–G), creates the identical pitch sequence but a different timing and accentuation. This distinction is often not reflected in the various notational renderings of the roll by scholars—indeed, there is less notational uniformity for the roll than for any other ornament, as shown in Examples 7a–7d. In my transcriptions I have modified Philippe Varlet's usage and indicate long rolls by LR and short rolls by SR.Footnote 24Examples 7b, 7c, and 7d are transposed to begin on G.

Example 6. Double grace note compared with the long roll.

Example 7a. Roll, notation variant from Varlet, Notes, n.p.

Example 7b. Roll, notation variant from Breathnach, Folk Music and Dances of Ireland, 97; McCullough, “Style in Traditional Irish Music,” 86; and Cowdery, The Melodic Tradition of Ireland, 19.

Example 7c. Roll, notation variant from DeMarco and Krassen, A Trip to Sligo.

Example 7d. Roll, notation variant adapted from O'Canainn, Traditional Music in Ireland and Cranitch, The Irish Fiddle Book.

In the short roll, the first note is not lengthened and the notes tend to be rendered “explosively,” as Breathnach puts it.Footnote 25 Another way to think of the short roll is as the last two-thirds of a long roll. Equally, the long roll could be considered as a short roll preceded by a tied eighth note.

Continuing to use “Boys of the Town” as a pedagogical illustration, Ivers played it again, this time incorporating both grace notes and rolls, shown in Example 8. She still applied embellishments only to the G–F-sharp–G motive, alternating between plain unembellished notes, long rolls, and double and single grace notes.

Example 8. “Boys of the Town” with grace notes and long rolls. Transcriptions published by permission of Eileen Ivers.

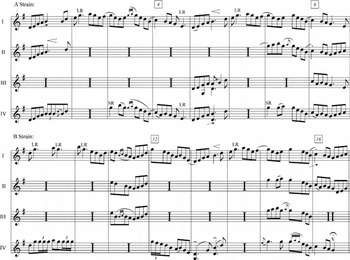

Long rolls in jig time tend to be placed most often, as in “Boys of the Town,” on the first beat of the measure, where they reinforce the natural accent. They can also fall, less often, on the second or, in the case of slip jigs, on the third beat. In “Kid on the Mountain,” shown in Example 9, long rolls are used consistently on the first beat (especially in mm. 1, 3, 9, and 11, where they replace motion to a lower neighbor), but in the second pass, when the ornamentation has become more elaborate, they occur also on the third beat (mm. 13, 18/IIb).

Example 9. “Kid on the Mountain.”

In reels, long rolls are usually applied to the second of a group of four eighth notes. The increased rhythmic stress on the second eighth note, produced by the augmented duration, the bow change, and a slight crescendo caused by increased bow pressure and speed, creates a strongly accented syncopation, which is “set up” by the first eighth note. In “Reel of Rio,” shown in Example 10, this rhythm (eighth note plus a long roll on a dotted eighth) forms one of the characteristic motives of the tune. Henceforth, this figure will be referred to as a syncopated long roll (my term). After three syncopated long rolls in the A strain separated by a measure or more, the B strain begins with three in a row. They are all associated with the note G (m. 2: E–G; m. 4: G–E; m. 6: E–G; mm. 9–10: D–G, A–G, B–G; m. 14: E–G). As in “Boys of the Town,” the most embellished pitch is the tonic.

Example 10. “Reel of Rio.”

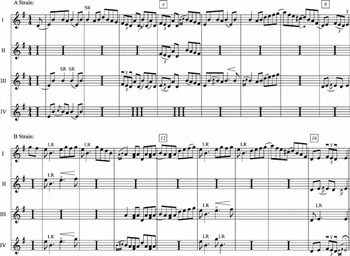

Syncopated long rolls are often clustered together in reels, especially in groups of three. In such clusters the pitch of the introductory eighth note changes, but the long roll itself always embellishes the same pitch. Examples include the three long rolls on G in mm. 9–10 of “Reel of Rio” in Example 10, and the three on B in “Cooley's Reel,” mm. 13–14/IV, shown in Example 11. An even better example is “The Bunch of Keys,” shown in Example 12, mm. 19–20/II, which has four syncopated long rolls on F in a row.

Example 11. “Cooley's Reel.”

The short roll is used in jigs in two situations: (1) when the roll must be limited to a quarter note because the following eighth note moves to a different pitch; or (2) when the player wants to compress the roll from a dotted quarter to a quarter in order to do something else (usually apply another ornament or diminution) with the free eighth note. In an example of the latter, the long E roll in Example 9, m. 2, pass Ia, of “Kid on the Mountain” changes to an appoggiatura eighth note followed by a short roll in pass IIb. To give an instance of the former, in m. 13/Ib, a short roll is applied to the G quarter note partly to preserve the passing F-sharp eighth note. This F-sharp is itself ornamented by a double grace note. This combination of two ornaments produces a sudden electric crackle in the sound texture. When Ivers decides to use a long roll on the same G in m. 13/IIb, she simply sacrifices the passing F-sharp altogether.

Just as long rolls are often placed on the first beat in jigs, where the beat (dotted quarter note) has a triple subdivision, so short rolls are often found on the first beat in reels, where the beat (quarter note) has a duple subdivision. Most of the short rolls in “Cooley's Reel” (Example 11) and “Reel of Rio” (Example 10) are of this type. In m. 1/III of “Cooley's Reel,” two short rolls occur one after the other, followed by another on the first beat of m. 2. This cluster of ornaments creates the same kind of explosive brilliance as the short roll plus a double grace note in Example 9, m. 13/Ia of “Kid on the Mountain.” Another example of paired rolls is the beginning of the B strain of “The Bunch of Keys,” shown in Example 12, m. 9, where the long G is ornamented by a short roll followed immediately by a long roll. The G is so static by itself that it positively demands ornamentation of some sort. This type of situation recalls C. P. E. Bach's statement that embellishments provide not only “opportunities for fine performance” but much of its “subject matter” as well.

Example 12. “Bunch of Keys.”

The Bow Trill

K. E. Dunlay and D. L. Reich define the bow trill as a “slightly uneven bowed triplet which has the same time value as a quarter note.”Footnote 26 Although usually notated as three equal notes in reels (in jigs it is notated as two sixteenths followed by an eighth), it is executed with a rapid shake of the wrist in a single gesture rather than as three distinct motions.

The bow trill can be executed in two ways: (1) with three repetitions of the same pitch, which gives a primarily rhythmic and percussive effect; and (2) with two or three different pitches, which adds a melodic component. This type of bow trill can also be played, alternatively, as a bowed triplet, provided that no two successive notes have the same pitch.

Ivers often starts the bow trill on the down-bow: down-up-down. This seems to be a matter of individual preference (Maureen Glynn, for instance, always started on the up-bow), but more research is needed on this point, as one or the other method may be characteristic of certain regional styles or teaching lineages.Footnote 27 Ivers digs into the string while playing bow trills even more than do most Irish fiddlers. Her bow trills are characterized by a crisp staccato crunch. This quality contrasts with and complements the more fluid whip-crack snap of the roll. Bow trills and rolls are usually interchangeable, especially in reels and hornpipes. For instance, in “Reel of Rio” (shown in Example 10) the syncopated long rolls in m. 9/I are replaced with bow trills in m. 9/IV. Both of these configurations are used so much in Irish fiddling that they are almost clichés. In this figure, the bow trill is preceded by two eighth notes, is played on the offbeat, and takes over the pitch of the second eighth note. Commonly, the preceding pair of eighth notes are on adjacent strings, as in the C strain of “The Bunch of Keys” (Example 12, mm. 17–18), or the beginning of the B strain of “Bonnie Kate” (Example 13), both transcribed from Ivers's playing. Under “Bonnie Kate” is an alternate version utilizing long rolls instead of bow trills.

Example 13. “Bonnie Kate,” B strain, beginning.

Bow trills can also occur on a strong beat in reels, where they give an added stress to an already strong accent. An excellent example is “The Bunch of Keys” (Example 12), m. 11/I, where the bow trill serves to articulate the initial D. This bow trill is made up of two pitches, the first repeated—D, D, C-sharp—possibly because the next note is D again, and four D's in a row would be monotonous.

The two bars that end each strain in “The Bunch of Keys” also begin with a bow trill, this time composed of three ascending adjacent pitches. Although these bow trills have a similar rhythmic effect as the one in m. 11/I, they do not serve to articulate any particular pitch. Bow trills of this type function rather as a connection between two pitches, often, as here, filling in the interval of a third. In mm. 7, 15, and 23 the second note of the bow trill acts as a passing note between F-sharp and A. The F-sharp–A ascending third, in turn, elaborates the initial F-sharp, which proceeds to G on beat two. Similar instances can be found in “Kid on the Mountain” (Example 9), m. 5/IIb (filling in a third), and m. 17/IIb (filling in a fourth).

Bow trills composed of three adjacent pitches in ascending or descending order function much like bowed triplets, with which they are usually interchangeable. Bowed separately, they take on the percussive quality and added rhythmic weight of a bow trill. An example occurs in “Cooley's Reel” (Example 11), where the ending formula is played as a bowed triplet in m. 8/I and as a bow trill in m. 16/I, IV.

Bow trills in reels have a very different effect when played on the strong rather than the weak beats. Ivers's reel playing is characterized by a very strong backbeat accent, and the percussive force of the bow trills helps to emphasize the offbeats. When the bow trill is moved to a strong beat the accentual stress moves forward, as it were, altering the swing of the reel. This shift in accentual balance is one of the ways that Ivers maintains a variety of stress and accent in a tune and avoids rhythmic monotony.Footnote 28 An excellent example occurs in “The Bunch of Keys” (Example 12).

The first five measures of the A and C strains are played with a heavy backbeat stress, which is caused both by Ivers's heavy offbeat bow pressure and by the ornamentation. The second beat of each of the first five measures is stressed by an ornament: in the A strain; a double grace note in mm. 1, 3, and 5; a bow trill in m. 2; and a short roll in m. 4. In the C strain, bow trills in mm. 17–18, rolls in mm. 19–20, and a double grace note in m. 21. Moreover, the cross bowing emphasizes the offbeats, as do the octave double-stops in m. 6/II. In the last two bars of strains A and C, the bow trills on the first beat shift the accent forward and partially neutralizes the backbeat emphasis. In the B strain, the same effect is created in m. 11 by the D–D–C-sharp bow trill in pass I and the long vibrated D dotted quarter in pass II, as well as by the bow trills on beat one of mm. 15–16.

In jigs, the bow trill usually serves to replace the first two eighth notes in a group of three; sometimes it replaces the last two eighths. In “Kid on the Mountain” (Example 9), the bow trills in m. 5/IIb, 13/IIb, and 15/IIb are of the first type; that in m. 17/IIb is of the second. Bow trills can also serve a harmonic function as an inner voice chord tone on the next lower adjacent string, especially the open A string in the keys of D and A. In “Humours of Ballyloughlin,” shown in Example 14, this dipping down to the lower string happens in mm. 17–18, where the A serves as a kind of intermittent staccato drone beneath F-sharp.

Example 14. “Humours of Ballyloughlin.”

Theoretically the same technique could be used on any open string, but Ivers feels that “it sounds a lot better in A because it's higher up . . .. it wouldn't come out half as well in D.” However, bow trills often serve the same function on stopped strings. “Bonnie Kate” (Example 13) and “Bunch of Keys” (Example 12), both mentioned above, are two examples. In the former, the melody A is followed by a bow trill on D, which continues to sound under the succeeding melodic A–B–A. In the latter (beginning of the C strain), B is supported by a bow trill on G.

The Cran

The cran is a uilleann pipe ornament that has been adapted by fiddlers; its use is not as widespread as the other ornaments. Besides Ivers, some other fiddlers who use the cran are Sean Keane of the Chieftains and Brendan Mulvihill. On the pipes the cran consists of a series of repeated pitches separated (cut) by different single grace notes. The exact pitches of the grace notes do not matter so long as the same pitch is not played as two consecutive grace notes.Footnote 29 Mitchell notes: “The actual notes played can, and do, vary from player to player; they can also vary in the playing of a single tune.”Footnote 30 On the pipes, the cran is usually applied to the low E, but especially to the low D. This note is the lowest on the chanter and cannot be decorated by any lower note, thus the cran serves as a substitution for a roll. It is conceivable that the bow trill developed on the fiddle as an open-string ornament for similar reasons, and then began to be used on stopped strings. Mitchell, in his analysis of the piping of Willie Clancy, groups rolls and crans together.Footnote 31Examples 15a–15d gives some of the ways scholars have notated the pipe cran, as well as my notation of Ivers's fiddle cran.

Example 15a. Cran, notational variant from O'Riada, Our Musical Heritage, 43.

Example 15b. Cran, notational variant from Breathnach, Folk Music and Dances of Ireland, 97.

Example 15c. Cran, notational variant, Ivers's fiddle cran.

On the fiddle, at least in Ivers's rendition, the cran is a compound ornament, combining the bow trill and the grace note.Footnote 32 It begins with a bow trill in which the first and last notes have the same pitch; the middle note is higher, conforming to the same fingering patterns used in grace notes and rolls. The last note of the bow trill is sustained on one bow stroke and cut by a single grace note of the same pitch as the second bow trill note. Ivers remarks:

The best sound of the cran is on the open string, so on the D what I'm doing is down-up-down with D–G–D. I use my third finger because it's stronger. And this time I'm trying to get sort of a crunchy sound on the fiddle. . .. And on the last D I'm going to go into a slur and grace-note an extra D. And the last G is not going to be a note now but just a grace note, like a flick of my third finger, to deaden the string basically. And I can also do them on the up-down-up, keep the up-bow going and do the grace note. Either way it works really well.

Although the cran can conceivably be played on any finger except the fourth, Ivers prefers to use it with open strings and the first finger. Example 16 gives the possible crans on the E string. The open string has the best resonance, and with both the open string and first finger the third finger has a broader range of motion and can produce a strong left hand pizzicato “ping” behind the bowed note. The bow trill in a cran is so rapid that the pitch of the second note is completely inaudible.

Example 16. Crans on the open E string.

Ivers remarks:

I asked a piper once, you know, what notes they use, and it just varies; there's no set notes. Like they could use sometimes—I thought it was interesting—say on a D again they sometimes use the F-sharp, say, as the note in the very beginning of the trill, and then maybe the G at the end. It's just whatever notes their fingers fly on, you know. But really, if you listen closely, you can't hear the difference between [plays D open-string bow trill] and [plays again]. All I did there was use the F-sharp on the first one and a G on the second one. It's just so fast. And again, the same reason, the third finger sounds better, it's a bit better for the fiddle because it's a stronger finger, you can really flick it more, as opposed to the middle finger or the first finger, where your flicking is sort of limited. . .. The third you can really just fly on.

The entire cran lasts for the space of a dotted quarter note (although in reels the last note can be extended by an eighth note. It can substitute for a long roll or a bow trill plus an eighth note; in jigs it often replaces a group of three eighth notes. It is always initiated on the beat.

Ivers feels that crans are more effective if used sparingly. They work especially well, as one would expect, in pipe tunes. One such tune is the jig “Humours of Ballyloughlin” shown in Example 14. Ivers uses crans on the open D string in the last two measures of the A, B, and D strains; in an alternate version of those measures (mm. 15–16 in the transcription), she plays three crans in a row, the first starting on a down-bow, the second up-bow, and the third on down-bow again. Crans are used on the open A string in mm. 5/II and 25/I. A good example of their application in reels appears in Example 10, “Reel of Rio,” m. 1/IV.

Slides and Ivers's “Contemporary” Practice

Ivers included the slide in her list of ornaments as an afterthought: “It's an ornament, in a sense.” It is not in the same class as grace notes, rolls, bow trills, and crans, but closer to double-stops and vibrato, which Ivers classifies as “techniques” rather than as ornaments.Footnote 33 On the transcriptions, slides are notated with an arrow pointing to the “slid-into” note.

Traditionally, slides always ascend. Ivers uses them to connect notes that occupy neighboring scale steps, sliding from the lower to the higher. The note “slid into” is usually a local contour peak, followed by at least one lower note (an exception is “Reel of Rio,” Example 10, m. 5/IV). She makes a distinction between a slide that connects two neighboring notes taken on the same bow and a slide (still connecting two neighboring notes) that is initiated on a new bow stroke. She prefers the former, which she describes as smoother and more subtle, to the latter, which is harsher and more abrupt. A slide will give a note an added feeling of lift. In Ivers's words, “It just shoves the rhythm out a bit more.”

Descending slides at the end of a note are a feature of Ivers's more “contemporary” practice. The downward slide can connect two notes or end a note. Sometimes Ivers will initiate a note with an upward slide and terminate it with a downward slide. This double slide is related to her practice of applying a crescendo followed by an immediate decrescendo on a single note or short phrase, creating a swelling-fading effect. Ivers employs these extreme (by Irish traditional standards) dynamic changes and upward/downward slides especially on the first tune in a medley, although a conscious use of dynamics, beyond that of most Irish fiddlers, is a feature of all her playing. This usage will often be coupled with a sensitive and selective use of vibrato.

These techniques, to one degree or another, are characteristic of fiddlers who are, or were, associated with traditionalist revivalist groups, such as David Swarbrick in Fairport Convention, Peter Knight in Steeleye Span, John Cunningham in Silly Wizard, and Kevin Burke in the Bothy Band.Footnote 34 A good example of Ivers's more modern practice is the jig “The Orphan” (Example 17), the first half of a medley from the album Cherish the Ladies.Footnote 35

Example 17. “The Orphan.”

Ivers's playing in “The Orphan” does not have nearly as pronounced a swing as her playing in the interviews and lessons. The performance is more finely honed, more meticulous. There is a greater care especially for subtle dynamic and articulative differentiations between notes as well as broader dynamic contrasts. She does not bear down as hard on the bow; the bow triplets and crans are bouncier and less crunchy.

The ornaments are the same, except for the crans in m. 7/IV, where the bow triplet that constitutes the first half of the cran utilizes three notes of the same pitch rather than a different pitch on the second note. The chief difference is the increased use of dynamic differentiation, especially in the long rolls. In my lessons and interviews the initial note of the long roll almost always crescendos into the four-note turn at the end. In “The Orphan,” some of the long rolls are played in this manner, but many have a crescendo-decrescendo dynamic envelope. Others are played with no appreciable change in dynamics. A descending slide appears in m. 3/V, where the B begins with an upward slide from A and ends with a downward slide to A. In m. 9/VI, the descending notes G–F-sharp–E are connected with downward slides.

The variant in mm. 1–2/V is a distinct departure from the rest of the tune. This change is clear partly because it is the only part of the tune doubled by the guitar (at the lower tenth). It departs from traditional practice in that it is not a direct elaboration or simplification of the melodic line and the descending two-measure contour is completely different from the contour of the other versions of mm. 1–2. It is prepared, however, by mm. 1–2/IV, which is based on the melody and preserves the general contour. The similarity between mm. 1–2/IV and V consists of the division of the two bars into four groups of even eighth notes without ornamentation of any sort; the contour of m. 2/V is the inversion of m. 2/IV.

“The Orphan” uses a greater range of syncopation than Ivers's playing in the interview-lessons. In m. 12/I and the first half of m. 13/I, the first note in each three-note group is accented, reinforcing the normal 6/8 stress pattern (the slightly stronger accent on the first beat is emphasized by the slide into B). But in m. 12/III the accentual stress shifts to the last note in each group (E and A), and the A is tied over into the next bar. In mm. 11–13/VI, the syncopation is even stronger, and alters the rhythm of the three-note groups. Now the second and third notes become the first two-thirds of a sixteenth-note triplet, followed by a rest that extends into the first beat of the next bar. These rests replace the B on the first beat of m. 12/I and the tied A in m. 12/III, V. The syncopated double-stops in m. 1–2/VI are another example. These double-stops do not contain any open strings, which somehow makes them stronger.

“The Orphan” begins with tasteful, somewhat sparse ornamentation and fairly “regular” accentuation. The ornamentation becomes more complex and dense as the performance proceeds, and the more outré elements, such as the strongest syncopations and the descending slides, occur only in the last three passes. This pattern is typical of Ivers's playing and of Irish fiddling in general.Footnote 36

Double-stops and Vibrato

Ivers uses vibrato fairly sparingly in her dance tunes, as one means of embellishing and adding weight to metrically stressed notes that have a duration of a quarter note or more.Footnote 37 In the transcriptions, vibrato is designated by a “v” placed above the note in question. A good example is “Kid on the Mountain” (Example 9). Whenever the quarter-note G appears on the third beat of an odd-numbered bar, it is highlighted in some way. In the first three passes of m. 3, for instance, it is embellished by vibrato and, in IIa, by an octave double-stop. In the fourth pass the octave double-stop recurs, but this time the note is emphasized by a quick short attack. In m. 15 the high G is vibrated in Ia and Ib, and emphasized by a heavy bow stroke without vibrato in IIa and IIb. In m. 1/IIa, IIb the stress on G is partly absorbed by the appoggiatura F-sharp, which displaces G on the third beat. The only other note that is vibrated is A (m. 14/IIb), also on the third beat, the one time it is augmented from an eighth note to a quarter plus an eighth.

Double-stops, as in the preceding example, are often used to add breadth and rhythmic stress. An instance of this usage is “The Orphan” (Example 17), mm. 6 and 14. The eighth-note group G–F-sharp–G is usually played in single notes, which puts the accentual stress on the first note. Sometimes, however, the second G is doubled with the open G string (as in mm. 2/III, 6/IV, and 14/I). This added weight shifts the stress to the third eighth note. Once, in m. 14/V, the first G is doubled at the lower octave, which places an even stronger emphasis on the first beat. Most of Ivers's double-stops involve the use of open strings, which often are retained as lower drones for the next few notes, as in “Reel of Rio,” m. 5/III (Example 10), or “Kid on the Mountain,” m. 1/IIa (Example 9). This use of open strings is not simply because they are easy to play but because their resonance and tone blanc contrasts with the quality of a stopped string. In Irish fiddling, open strings are an asset, and their unique tone is exploited in performance. Double-stops without open strings, as in “The Orphan,” mm. 1–2/VI, tend to have more weight than double-stops where one of the notes is an open string.

Placement of Ornaments

One criterion in ornamenting a tune is simply the need for variety. Ivers observes:

The trick is to combine them in an interesting way, so you're not overdoing too many rolls or too many grace notes or whatever—bow trills, crans—in the tune. The crans are the least used. They're used very infrequently, because they're sort of tiring. They're kind of nice when they come out of the blue in a tune. Rolls are very, very popular, and the bow trills are sort of popular, and grace notes sort of fall in all over the place.

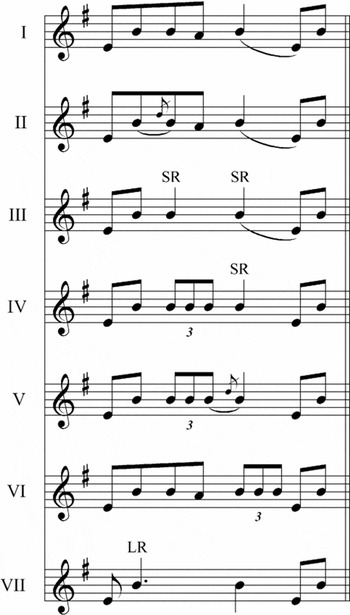

Her feeling is that, given the right amount of space, any ornament can substitute for any other. If there is not enough space for a particular ornament the tune can be altered—“cut and pasted”—to make space: “You can make anything fit.” For instance, the first bar of “Cooley's Reel” (Example 11) is mainly taken up with the note B, and the player's problem is how to enliven that note to prevent it from forming a static space. The longest stretch of B starts on the second half of (quarter) beat one, and persists through beat 3 (the A is a less important embellishing tone). Ornamentation usually falls on the second and/or third beats. I will distinguish the B's that fall on the second half of the first beat, the second beat, and the third beat respectively by labeling them B1.5, B2, and B3.

Example 18 presents six versions of the first measure of “Cooley's Reel” from Ivers's playing and a seventh that is my own idea. In I, the “basic” version, there is no ornamentation at all, and the B is embellished by motion to lower neighbor A. A is present as an eighth note in II and VI, and incorporated into rolls in III, IV (moved a beat later), and VII. Only in V, where B2 and B3 are ornamented with a cran (of which the last note is extended by an eighth note) is A entirely absent. The ornamentation of Examples II–VII is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of ornamentation in Example 18, Versions II–VII.

Example 18. “Cooley's Reel,” m. 1, variants.

The Functions of Ornaments

As Robert Donington has demonstrated, C. P. E. Bach, in the well-known passage quoted at the opening of this article, suggests that ornaments have functional roles.Footnote 38 First, “[t]hey connect and enliven tones”—a melodic function. Embellishments in Irish music articulate or emphasize a particular pitch in two ways: (1) grace notes, rolls, bow trills, and crans create minute melodic diminutions; (2) ornaments highlight or attract attention to a pitch and “enliven” notes, especially long notes (such as the G in “Bunch of Keys,” m. 9), which otherwise would become static. Bow trills composed of three stepwise ascending or descending notes “connect tones,” as do slides. Second, they “impart stress and accent”—a rhythmic/metric function. Here, too, ornaments function both as rhythmic subdivisions, and, more important, as accentual stresses.

A category not specifically mentioned by Bach is the role of ornaments in varying texture and timbre—not an inconsiderable part of their effect in Irish fiddling. Bow trills and crans have an audible crunch, rolls a kind of whiplike snap, and vibrato alters the linear texture. In grace notes, rolls, and crans, the angle at which the fingers hit the string sounds a left-hand pizzicato that articulates the note behind the bowed stroke. Double-stops add weight and thickness.

These are the main categories of ornamentation. But other comments by Bach are also certainly valid for Irish fiddling. Ornaments in Irish fiddling “provide opportunities for fine performance” and constitute “much of its subject matter.” There is no doubt that they “improve mediocre compositions.” Although there is no specific affective association to any specific ornament, it is true that embellishments “will lend a fitting assistance” to the expressive content of a tune.

It is important to realize that ornaments are not the only techniques at the fiddler's disposal to create rhythmic accentuation and melodic articulation. These differentiations can also be realized by playing a note: (1) long or short; (2) loud or soft; (3) with heavy or light bow pressure; (4) with fast or slow bow speed; (5) with a sharp, martelé attack or a smooth legato initiation;Footnote 39 (6) with a crescendo or a decrescendo. Another crucial variable, which I have barely addressed, is the bowing pattern. More than anything else, bowing shapes the phrase, as well as creating accentual stresses. These variables not only act when ornamentation is absent but are also an essential part of the technical execution of an ornament. The crunch of a bow trill or cran is caused by a martelé attack with heavy bow pressure; the first note of a long roll usually is played with a crescendo that results from the gradual increase of bow pressure and bow speed; and any ornament is necessarily played at some dynamic level and with a certain bowing pattern.

I discussed all of these issues with Ivers, and, as an experiment, she attempted to play “The Reel of Rio” without ornamentation—which is almost unnatural—but achieved the same effects through the manipulation of bow pressure, bow speed, dynamics, as well as vibrato and double-stops, which she considers techniques rather than ornaments. In her rendition, the essential swing is still present. As she reflects, “It's very difficult, but still, if everything else is there, it still sounds good.”

Ornaments are the most sophisticated and complex tools for “enlivening tones” and “imparting stress and accent,” but they are supported and complemented by the variables explored here, which can create the same effects, although perhaps to a lesser extent. These parameters in turn depend on the fiddler's basic technical skills, without which no ornament can be executed with proper timing and accent. The most important of these skills is the manipulation of the bow to create a danceable feeling of lift and swing. If this skill is present, then the ornamentation acquires its proper quality of sharpness, precision, and snap.