On his return to France from a brief stint working for the new French military government of occupation in post-war Baden-Baden, the future sociologist Edgar Morin despaired of ‘the ennui, the ennui of the southern Algerian “bled”, small-town colonial ennui, the ennui of the stay-at-home Frenchman when he doesn't have France, or his bistro . . . his pals, the atmosphere in his town, his memories, his furniture’, that he suggested afflicted the French community in occupied Germany.Footnote 1 Morin was scathing of his countrymen – and of his countrywomen too – but that a French community was in the process of being born he seemed in little doubt. Little has been written in English about the French Zone of Occupation (ZFO, or Zone) whose governance, along with the French sector in Berlin, required as many as 750,000 French personnel immediately after the war. It is this substantial group of people and the means of their transformation into a French national community that preoccupies me here.

German historians initially regarded the French as incompetent and unkind governors, intent on retribution for four years of German occupation in France, and historians continue to debate whether the view of Germans as enemies drove French policy.Footnote 2 Studies of the French presence in post-war Germany tend to fall into three broad strands: the Cold War and European integration;Footnote 3 Franco–German economic relations;Footnote 4 and the impact on Germany of distinct aspects of French policy.Footnote 5 All these foreground international relations. Nor do most histories distinguish between the French in the Metropole and the French in the Zone, a practice members of the military government may have found surprising. Called the ‘military government’, it was in fact run by two branches of French administration: the military, who reported to the Ministry of Defence, and the diplomatic, governed by Foreign Affairs. Civilians were accorded military rank (swaggering in their specially designed flashy uniforms, much to the derision of career military),Footnote 6 but ultimate responsibility rested with the high commissioner, a diplomat who, after 1949, was also the ambassador. Conflicts between his office and the commanding general's, and between French headquarters in Baden-Baden and Paris, were continuous, and inform the story told here. In it, I turn the gaze inwards, to explore the ZFO in terms of the nascent French community. In so doing, I draw a contrast with much diplomatic and military history, and respond to Morin's tantalising allusions, by exploring the little-known domestic side of the French army of occupation.

The French military in post-war Germany was very different from the army which had just helped to win the war – or believed it had.Footnote 7 Regardless of US, British or Soviet opinion (which excluded France from Potsdam), such were France's self-important ambitions that the diplomat René Massigli imagined its Berlin sector would be located at the city's very cultural and strategic heart.Footnote 8 (Among other landmarks, the French sector was to include the Siegessäule, the Reichstag, Gendarmenmarkt, Französische Straße, Pariser Platz, Friedrichstraße station and Bellevue palace. None of these was actually in the smallish corner of north Berlin that became the French sector. The Soviets governed the pre-war city centre, while West Berlin's new administrative centre was under US control.) Readers of the glossy monthly for French troops, the Revue d'Information des Troupes Françaises d'Occupation en Allemagne, which started in October 1945, were invited to reflect with pride on the French army's victorious exploits in 1944–5, a pattern duplicated in the book its editor published in 1949.Footnote 9 Double-page spreads illustrated with watercolours of soldiers on the move allowed readers to believe that France's position as the fourth member of the quadripartite Allied command, the Kommandatura, was deserved.

After 1945, though, the French army in Germany was static. Notwithstanding the Cold War and the steady transfer of men to Indochina and Algeria, in Germany at least, this was a pacific army. Indeed, officers complained that soldiers could not even shoot; ammunition shortages made the few practice guns, often sports rifles, unusable.Footnote 10 The Revue d'Information had no stories about manoeuvres in the Zone. The considerable material it did run about the army included histories of the units stationed in Germany, features about action under fire in the resistance or Indochina, reports of them presenting arms, in fitness training or building hospitals in Germany, but not once is the army featured as a fighting instrument there. Other than parades, then, this was an army that did scarcely any marching. Their stomachs, on the other hand, remained primordial to officers’ concerns.

This was not only because of the size of the occupation forces, though it was substantial. In autumn 1945, there were nearly 330,000 French individuals working for the military government in the Zone, plus around 5,600 family members, and 400,000 in Berlin.Footnote 11 Officer numbers dropped slightly thereafter, but these were more than compensated for by the arrival of women and children. Compared to ten occupiers per thousand German population in the British Zone, and just three per thousand in the American Zone, from 1946, France employed eighteen occupiers per thousand Germans.Footnote 12 Family members who were routinely assumed to accompany officers added to these figures, and trains from France to Germany were crowded with women and children joining their husbands and fathers.Footnote 13 Precise totals are difficult to establish, but top brass were so concerned about the provision of appropriate family facilities, such as housing, food and clothing, that it is clear that officers were expected to live with their wives and children. The new French enclave thus had similar requirements to civilian populations, and the French authorities established schools for their children, an extensive network of leisure facilities, social and health services, and the means to fulfil their day-to-day needs: shops.

These shops were the économats. Originally a co-operative system devised at the beginning of the Third Republic for railway workers to obtain necessities at cost price,Footnote 14 the économat took charge of military provisioning during the First World War. Their status was confirmed in 1939 and remained in place through several administrative adjustments up to the period in Germany where they assumed control of the entire military domestic retail market.Footnote 15 The économats were a rather contradictory sort of shop. They resembled private establishments, but were run by a major public service, the army, which ferociously guarded this responsibility against civilian incursion.Footnote 16 Just as the military government reported to two separate ministries in Paris, so there were two sets of food supply lines in the ZFO: Ravitaillement, the civilian supply unit, was responsible for feeding the Zone's entire population, while Intendance supplied the military.Footnote 17 As an army organisation, military men with no relevant know-how were often put in charge of the économat, despite the likelihood that many members of the occupation forces would have had prior experience in the commercial sector. Military governance was often bureaucratic and cumbersome, and decisions were made in line with army protocol rather than commercial practicalities.Footnote 18

French military and diplomatic archives demonstrate the authorities’ perhaps surprising level of concern for their married troops, and for the French community in West Germany overall. Through these records we can begin to understand the establishment of this community via its households and their consumption, and bring into focus the formations of French identity that remain rather obscure in the existing literature. The Zone offers an excellent case study. In contrast to unsustainable claims that Germany in 1945 was at zero hour (Stunde Null) the French did build communities from scratch (albeit in the context of at least 150 years of French presence east of the Rhine), bringing their own patterns with them. Germany provided a unique environment: it was a familiar, neighbouring country (though one that French people rarely visited as tourists) and shared Catholicism as the regional religion.

Military occupation and its express wish for what, since 2003, has become known as ‘regime change’, often looks something like colonialism. The commitment to establish locally developed democratic independence may appear, on the evidence of early twenty-first-century Afghanistan or Iraq, at best slight. Bearing in mind the fractured power struggle of French and German occupation and counter-occupation of each other's countries that had persisted throughout the period since 1870, it is worth querying whether the French occupation of post-war West Germany was itself an imperial project. France, moreover, was a powerful colonial presence elsewhere; three of the Zone's first four military commanders (Generals Goislard de Monsabert, Sevez and Guillaume) had led colonial divisions during the war, and members of the military government may have had administrative experience in French colonies in Africa or south-east Asia. Colonies, argues Ann Laura Stoler, are characterised by ‘ambiguous zones, partial sovereignty, temporary suspensions of . . . the right to have rights, provisional impositions of states of emergency, promissory notes for elections, deferred or contingent independence, and “temporary” occupations’.Footnote 19 Coming hard on the heels of the brutal and, to a degree, colonising, German occupation of France between 1940 and 1945, the French occupation of Germany fulfilled some of these criteria and was initially, perhaps, closer to imperial ambition than the other Allies were prepared to countenance.Footnote 20 Nonetheless, both the Cold War and the lack of a sense of racial superiority that French forces adopted with respect to the Germans, and a real, and realised, desire for German self-determination – achieved in four years – make post-war Germany something of a colonial anomaly.Footnote 21 Where these distinctions become a little blurred, however, is with respect to the various sorts of segregation that were imposed between French forces and Germans; these, I suggest, were for national rather than racial reasons. And while French authorities may have been clear about where their (shifting) national interests lay, the essential component to the realisation of these interests in the form of a (French) ‘national community’ was not something that was already in place. It had to be made. It is the materialisation, via some of its private and domestic dealings, of this community – a community that would bolster and entwine with French national interests – that this article sets out to trace.

It asks if we can understand the construction of a French community by looking at systems of domestic buying and selling – systems that inevitably implicate gender – and whether they were not themselves constitutive of the very transformation of a disparate group of soldiers and civil servants into a ‘French community’. In the early period of the Zone, requisitions fulfilled myriad French needs, from factories and housing to the most basic (for instance, the blanket and sheet – in good condition – that each household had to supply in January 1946).Footnote 22 Quickly though, the French started to establish their own enclaves in purpose-built barracks for ordinary troops and private apartments for officer families. Across the Zone, the army built or acquired its own leisure facilities, dining areas, hospitals and nurseries, and it paid great attention to the needs of its married officers who were expected to live with their families. Army reports from the Zone to the Ministry of Defence in Paris frequently demanded recognition of the particular requirements of pregnant women and children, an oddity in military records.Footnote 23 Most often, these reports concern the supply of goods to support their specific needs.

In the context of this significant presence of French households and the infrastructure to support them, then, this article explores whether particular practices of distribution and the values placed on goods can be used to determine a sense of community, and whether they provide a way to interpret broader relations with local German neighbours over whom the French would rule for ten years after the war. These questions inform this story of internal relations within the French enclave, which will be told by a focus on the consumption of ‘basic goods’.Footnote 24

These were goods that were seen to reflect a certain sense of what France should be. They were largely those used in the home – the ‘single most important site for material culture’Footnote 25 – and purchasers were assumed on the whole to be women. Gender and consumption thus form the twin theoretical planks on which the argument here rests. Historians of both often insist on the notion of constructed identities; here, it is suggested that we need to historicise both the means whereby a gendered or consuming individual is constructed, and the meaning that the goods consumed confer on the society under examination. That the consumer is constructed, rather than a naturally emergent being, is taken as self-evident. As Frank Trentmann has indicated, historians have progressed from regarding the de-individualised consumer either as a simple product of mass society or as driven by a compulsion to make rational choices.Footnote 26 Nor is it any longer surprising for historians to consider the consumer as gendered, and shopping as overwhelmingly women's work.Footnote 27 The gendered consumer is also someone whose behaviour helps to construct broader identities. Nancy Reagin argues that via their consumption, German housewives elaborated a community of national cleanliness that became an integral part of Wilhelmine national identity.Footnote 28 In the period after 1945, suggests Erica Carter, the feminised consumer helped make possible the construction of a new West German national identity via the development of a ‘national economy as a textualized and gendered cultural space’, in place of a historically more problematic identity formed around the state.Footnote 29 Activities of consumption elsewhere were also productive of social identities; the gendered citizenship of the ‘citizen-consumer’ derived from their ability both to purchase and to intervene in the polity by virtue of that consumption.Footnote 30 In France, Rebecca Pulju regards the rise of a normative post-war French family as one product of the dynamic relation between women's consumption and mass consumer society.Footnote 31

This sort of economic dialogue between state and female ‘citizen-consumer’ flourished after the mid-1950s; the story told here focuses on the hungrier years immediately after the war, and forms a bridge between the mass consumption of the late 1950s and 1960s and the privations of the war itself. French consumers in the ZFO were on the margins of these movements chronologically, therefore, but also geographically and politically. While metropolitan France was experiencing major socio-economic shifts, the fact that families were moving to Germany disrupted old class allegiances in other ways, partly because of the new expectations for raised standards of living discussed below. These differences of place, politics and class need to be understood within the context of a community abroad that was in the process of making itself as emphatically French. National identity was affirmed to themselves as much as to others by the uniforms that they wore, the enclaves in which they lived, and their frequent public displays of Frenchness, such as military parades. The need to reiterate and reproduce this French national identity while on foreign soil was, this article will argue, reaffirmed still more via the consumption of specifically French produce.

It should be clear, therefore, that we shall here be less interested in the production of the consumer than in the meanings attributed to the products she was intended to consume, their means of distribution, and the agents – in this case, the army – which determined the array of goods and the context within which they were available. This article's argument rests on an assumption that consumption is embedded in a set of material circumstances whose relationship is worth historicising. Oddly, little attention has been paid in recent cultural histories of consumption to the French experience of shopping. This article goes a small way to rectifying that trend.

Feeding the troops

French residents in the Zone had to shop in the économat. By September 1946, there were an astonishing 432 économat shops in the Zone, including twenty-four in Baden-Baden alone and a further seven in Berlin.Footnote 32 They sold fresh food and groceries, drinks, tobacco, clothing, shoes, children's items, and multiple domestic necessities from haberdashery and notepaper to highly sought-after (but rarely available) fridges and sewing machines.Footnote 33 Shops were reserved for the sole use of French customers who worked in some capacity for the administration. Rules were adjusted in 1951, but at no point were Germans permitted to make purchases, even if they worked in the shop, and they could expect punishment if they tried.Footnote 34 Until 1949, nor were French customers permitted to shop in German shops. Access was regulated by a complex system of ration cards, which changed according to stock availability and rationing, with separate cards for different kinds of goods. The majority of these goods were imported from France. These restrictions on access, and stipulations about the origins of goods should alert us to the project of national implantation that appears to have been underway. Far more was at stake here than simple questions of organisation.

Each of the western armies of occupation in Germany established shops to supply troops with essential memories of home, though what was considered essential differed in important ways, as did the functioning of the shops. Like the économat, the United States PX (Post Exchanges) were founded during the First World War. From 1941, they aimed to supply the luxury comforts that US troops were expected to miss – top-selling American brand cigarettes, sweets, toiletries, Coca-Cola, weak beer and chewing gum and, for the 150,000 female troops, suspender belts and make-up.Footnote 35 In post-war Germany, the PX became a significant part of American military life with relatively few large shops which stocked a huge range of goods at bargain prices. Happy customers at the Heidelberg PX, for example, were pictured snapping up giant boxes of Hershey chocolate bars and cartons of American cigarettes.Footnote 36 British troops were catered for by the Naafi (Navy, Army and Air Force Institute). Founded in 1921, the Naafi aimed during the war to feed British, colonial and other Allied troops according to their perceived cultural needs. Naafi shops in Germany sold plenty of alcohol and tobacco, and non-food household items. Good profits were made from selling hard liquor to Americans forbidden to buy this at the PX.Footnote 37

Governance of the économat was informed by post-war shortages and post-war politics, and often led to sharp exchanges of views between Baden-Baden and Paris, and between the military and diplomatic axes of the French occupation government in Germany. Economic conditions may have been unalterable; the strategic response to them, however, in the decisions about how to feed the French military forces, was entirely political. Before we explore its evolution and its impact on the community under discussion, it is necessary to provide a sketch of France's post-war agricultural economy.

Agriculture and industry in both countries were terribly damaged by the war. Across the Zone, little more than a third of 1938 levels of such German staples as pigs and potatoes were produced in 1945–6, and farming was in sharp need of modernisation.Footnote 38 Likewise, French agriculture had been improved by neither Vichy's back to the land scheme nor the German occupation. Apart from the physical destruction of buildings and land, the French economy was subjected to more Nazi asset-stripping than any other occupied country, with German demand often exceeding total production.Footnote 39 Difficulties produced by war-time worker absences and shortages were aggravated by two unusually harsh winters in 1944–5 and 1946–7 followed by drought in the summer of 1947. Not only were 1.9 million fewer hectares under wheat in 1946–7 than in 1938, but yield per hectare had dropped to around three-fifths of pre-war levels.Footnote 40 For a country whose main staple was bread, the effects of these reductions were widespread. Food imports rocketed; exports slumped.

The broader economic context was a France where inflation was running at around 50% between 1946 and 1948, only falling to manageable levels after 1950. ‘Food’ and ‘prices’ jostled for first place as issues of the greatest concern in public opinion polls.Footnote 41 By late 1949, the French franc was worth seven times less against the dollar than in 1945, after four devaluations from December 1945. Efforts to encourage consumers via two reductions in food prices of 5% each in January 1947 and March 1947 had no discernible effect.Footnote 42 Foods which had been rationed during the war (via a notoriously uneven rationing system), and still were, included bread, flour, crackers, pasta, sugar, coffee, rice and rice products, pearl barley, milk, dairy products, meat, chocolate, jam, fruit preserves, saccharine and cooking fat. From 1945, these were joined by pulses, tea, chicory, malted barley, fruit, fresh vegetables, eggs, fresh and tinned fish, potatoes, wine, walnut oil, olive oil and confectionery.Footnote 43 People accustomed to these conditions took over the governance of south-west Germany. ‘It leaves a bitter taste having to serve a hungry master’, observed one author of the ZFO from the safety of the American Zone.Footnote 44

It is something of an understatement to suggest that French customers of the économat were not expected to go hungry. During the period of rationing (bread was no longer rationed in France in 1948, and most other foodstuffs in 1949), army managers devised rations that entitled them to provisioning far superior to the French in France and their German neighbours.Footnote 45 Until the mid-1950s, working people's diets throughout France were dull and stodgy. Meat was a treat, and fresh fruit a rarity.Footnote 46 In the ZFO, Germans were expected to subsist officially on around 1,500 calories per day, though in January 1947, they actually received no more than 1,090 calories, fluctuating to a high of 1,396 calories in April 1948.Footnote 47 Where the British population was feeding Germans by foregoing food themselves,Footnote 48Ravitaillement planned 3,500 or 3,600 calories per day for the French population in the Zone (aside from gendarmes, security personnel, foresters, and fathers of large families who were to get even more).Footnote 49 Daily per capita rations would include half a kilo of fresh vegetables, 200 grams of chicken, the same quantity of fresh fruit, 140 grams of meat, half a litre of wine, 5 grams of chocolate and 40 grams each of cooking fats and cheese, plus bread, coffee, pasta, pulses, sugar, jam and potatoes, and three eggs a weekFootnote 50 – even more than serving sailors were allocated.Footnote 51 This excessively ambitious diet – beyond the expectations of any demographic sector in France – emerged in part from a desire to make Germany pay for its own occupation of France: the army, weakened by hunger, would quite explicitly be fattened up. But this fantasy diet and the excessive investments in food that it demanded were also a means to express a new version of national strength, which had more than merely material consequences, speaking instead of ideological desires.

On a practical level, only groceries and bread were supposed to be supplied from France; all other fresh foods to feed the military government were to be derived from local sources. In fact, the French initially sought to import vast quantities of goods, raw materials and food from Germany, and to feed the French in the Zone too.Footnote 52 Given the parlous conditions in Germany in autumn 1945, plans for the occupiers’ diets were far from realistic: there were no eggs or chickens, little fat or cheese (partly because German milk was being shipped to a Strasbourg cheese factory whose production was distributed in France), no wine, and less than half the anticipated quantities of meat, fruit and vegetables (and then only carrots and turnips). In fact, the only commodity in relatively plentiful supply was potatoes. All this was the case in early autumn; conditions could only worsen during the winter, so the food needs of the French population could not but be fulfilled by the Metropole.Footnote 53 (Potatoes were a perpetual worry. They kept rotting in storage, and in 1948, the occupation government had to ‘borrow’ 10,000 tonnes from the Germans to tide them over the winter.)Footnote 54

The response to these problems of supply was by no means predetermined. Occupation authorities quickly abandoned plans to provision French forces from German resources. In its place, they made such a special virtue of ‘buying French’ that French customers were even banned from shopping in German shops.Footnote 55 Instead, they were obliged to buy French products in shops that were restricted to their use. That there were ideological undertones to the rules governing how shoppers were supposed to make purchases is also revealed by official responses to infractions to the ‘buy French’ rule. These were threatened with both material consequences, such as fines, and via discursive means, such as scare stories about the tubercular dangers of German milk and meat. This sort of propaganda was deliberately circulated to warn customers off non-French food, despite private admissions that German veterinary checks were more stringent than French ones, and that both countries permitted milk to be sold from cattle infected with TB.Footnote 56 Although French consumers persistently attempted to circumvent these rules, the sanctions imposed on them demonstrate that more was at issue than the mere practicalities of getting enough food in soldiers’ bellies: we see here the delineation of a Frenchness that had normative force, and the establishment of national norms to which all members of the French community in Germany were enjoined to conform.

As the articulation of these rules implies, the adoption of such norms did not run altogether smoothly. There was customer resistance – some individuals engaged in clandestine selling on to Germans of scarce goods that they had bought at the économat,Footnote 57 or bypassed the shop all together to barter directly with German producers – and économat managers themselves fought a long campaign to preserve the économat's status. These efforts to protect its independence involved the establishment of some unusual commercial practices. First, économat managers saw no need to make a profit. Unlike the original railway économat, where a public service commitment enabled customers to buy goods at cost price, however, the économat outlets in Germany were terribly expensive. Prices were so uncompetitive that they could be as much as double those of the same goods available over the border in France, and higher than similar goods in German shops.Footnote 58 These price differentials and unauthorised price hikes incited hostility from the économat's own customers, as well as from critics who probably rightly felt that shoppers in France were going short.Footnote 59

The économat's atypical approach to money was compounded by baroque exchange arrangements. French occupation authorities operated in four currencies: the French franc; the Reichsmark (until currency reform in 1948) and the Deutschmark thereafter; the internal currency used by the French population in the Zone, known as the ‘occupation franc’; and the US dollar, which formed the basis on which other calculations were made. Marks could not be converted into francs and all decisions relating to supply were subject to rapidly shifting exchange rates and rocketing inflation in France. French suppliers were paid in francs; German suppliers were paid in marks; suppliers elsewhere – in Switzerland, for example – demanded dollars (making Nescafé an unaffordable luxury).Footnote 60 To overcome these impediments, the économat made the novel decision to sell goods – in a single shop – in both francs and marks. But this still left the army short of hard French currency to buy the bulk of its stock which came from France.

While France adopted an early policy of exporting as much as possible from the Zone into the Metropole, the inverse was also true. The cost of goods being far from equal across the border, complicated calculations, and not a little profiteering and dumping of surplus,Footnote 61 often low-quality, stock from France on the German market, occurred (such as the consignment of 36,000 litres of vinegar brewed from undrinkable Bordeaux wine which ended up on the German market where, being more expensive than German vinegar, it probably sat gathering dust).Footnote 62 Once it was decided that certain foods would be sought from German suppliers, and both paid for in bulk and sold to individuals in marks, a portion of French wages had to be paid in marks. The économat business had to keep accounts in two currencies, but the mark – unexchangeable and useless for paying for costs such as wages or transport – had to be kept within very strict limits, not always achieved.Footnote 63 Management difficulties were exacerbated by the tendency of those near the French border to pop over to France – using army supplied petrol in army vehicles – to stock up (a perk impossible for those stationed in Berlin).Footnote 64 Shops which planned their stock on the basis of likely demand complained about their inability to predict sales, though as far as Ravitaillement were concerned, it was Intendance's ‘insufficiently commercial methods’ which were to blame for the many complaints about the économat and its poor functioning.Footnote 65 The army, though, vigorously deflected criticism that the économat failed to control prices and profits – along with the less than credible assertion that losses and theft were so low as to make barely a dent in the books.Footnote 66 It even claimed that customers enjoyed the dual currency arrangement.Footnote 67

This chaotic system underwent a kind of regularisation in 1950, but it was probably a combination of monetary reform, unprofitability, army mismanagement, price fluctuations and the ‘heavy responsibility’ of the cost of keeping the économat going that propelled the Minister of Defence in Paris to announce its complete closure in 1950.Footnote 68 In place of the several hundred économat outlets there would be around ten new PX-style co-operative stores, selling a much smaller range of products in occupation francs to French purchasers.Footnote 69 Opposition to these proposals came from the highest level in Germany, and united the often rival civilian and military wings of the French administration, along with, they claimed, the other Allies.Footnote 70 No sooner had the co-operative proposal been tested with a Strasbourg group than it was rejected out of hand by the Zone's commanding general.Footnote 71

The main problem for the minister appears to have been Intendance's inability to run the shops properly. As an interim measure to deflect criticisms of army mismanagement, it established a new governing council, the Conseil des Economats en Allemagne. This comprised military, trade union and, crucially, family representatives, and resolved early in 1950 to defy the minister.Footnote 72 It demanded government funding in marks to pay German staff, that the économat could make more profit, and to be permitted to buy more supplies in Germany. All these demands were rejectedFootnote 73 – but the minister still failed to close down the économat. Discussions about the closure revolved around the best means to maximise French trade in Germany without loss of économat jobs or increasing the complications in feeding the troops.Footnote 74 As one adviser put it, ‘The [Paris] government is only interested in reform [of the économat] if they can envisage a free flow of French agricultural surplus into Germany. Possibly the Federal supply ministry would accept cauliflowers and dates instead of meat and margarine, but they will only accept them at German prices’. Now that in certain areas of France there was enough food to export, the poor exchange rate ‘would not produce enough marks against francs in reserve. Thus, French consumers in Germany would be asked to subsidise French agricultural products and would justifiably protest’.Footnote 75

Selling Frenchness

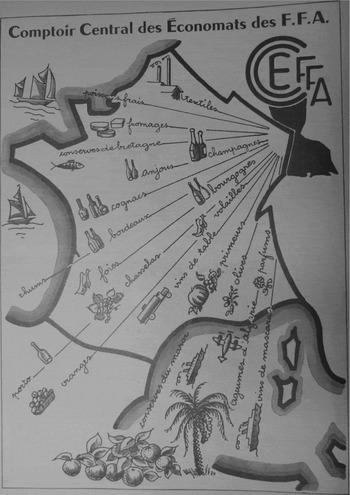

Despite a detailed survey of the économat's problems conducted by the Ministry of Defence in 1948–9, the failure to close them down arguably rested on the fact that these peculiar non-profit-making shops, run by frankly incompetent army managers,Footnote 76 whose staff were notoriously rude to customers, had a function other than the sale of potatoes, eggs or socks: they were part of an ideological implantation of France in the midst of former enemy territory, and what they sold (at inflated prices) was Frenchness. Once the co-operative idea had been abandoned, the économat expanded into the Comptoir Central des Economats des Troupes d'Occupation en Allemagne (Central Syndicate of the Economat for Occupation Troops in Germany), which made even greater virtue of the Frenchness of its supply chain. Advertising showed abundant goods, overwhelmingly comestibles, flowing from France and North Africa into Germany (Figure 1). The économat thus actively encouraged desire for French products alongside disdain for similar German ones.

Figure 1. Advertising French goods for sale in the ZFO.

Source: Revue d'Information des Troupes Françaises d'Occupation en Allemagne, Jan. 1950.

This sort of promotion was not solely about trade. Paris was extremely concerned that French people in Germany should continue to consider themselves French. In 1953, the French consul in Stuttgart (outside the Zone) informed Paris that many French civilians living in his jurisdiction district no longer bothered to attend events mounted by the consulate, such as 14 July celebrations. It was uncertain whether they even spoke French any more.Footnote 77 These were real concerns about the potential assimilation of the French into Germany, which the économat mirrored. The insistence on at least two-thirds of stock being of French origin, and that every économat had as an absolute minimum a butcher, a baker, a grocer, and a clothes and knick-knacks shop,Footnote 78 helped to remind French customers of home, and its small, local shops. Moreover, the wish to fulfil the cultural culinary desires of the French military population was clear from the complaints that officers running the économat sent their top brass and from managers’ efforts to ensure certain supplies. These concerned two commodities above all: meat and vegetables.

Not all goods, even if they appeared similar, had the same value. Convoluted efforts were made to fulfil the French preference for fresh, unhung meat over chilled or frozen. Consequently, it had to be supplied from German farms as livestock. In exchange, frozen meat imported from France would be offered for sale on the German market. In mid-1948, a plan to import 700 tonnes of frozen meat from France, of which only 300 tonnes would be sold in the économat, collapsed because the économat refused even these quantities on grounds of customer preference, and the costs involved. Nor were German butchers considered capable of presenting meat to French customers’ taste.Footnote 79 Despite the fact that freshly slaughtered meat was often unavailable, and exchanging frozen and fresh meat added greatly to prices, Oficomex was still supposed to bear the costs involved.Footnote 80 In France, cultural capital was accorded to fresh meat, especially beef. Working people considered that charcuterie was not really meat; beef, on the other hand, was so appreciated that, according to one anecdote recounted to a sociologist by a military chef who served his troops hamburgers and chips every single day, it was not they who demanded a change, but the cooks.Footnote 81

Shortages – sometimes the complete lack – of fresh vegetables, on the other hand, were thought so serious that they were even held to damage morale.Footnote 82 The supply of fresh vegetables had been one of the driving forces behind the establishment of the économat, and continued to inform its existence.Footnote 83 The only picture of a working économat to illustrate a ten-page article in the Revue d'Information on Intendance's shops and other services shows most of the sales space taken up with what appear to be boxes of potatoes and onions.Footnote 84 Vegetables were demanded not only for nutrition, though report after report regrets their absence, but also for other cultural purposes. When the British proudly served ‘beef rissoles in brown sauce’, ‘boiled cabbage’, ‘baked jam roll’ and German (that is to say, requisitioned) wine at an international banquet at the Berlin Kommandatura, one might imagine that the men would rarely consciously miss their vegetables. For the French, who for months after arrival were obliged to wear uniforms borrowed from the American and British armies, and whose officers were ashamed that they had no clubs at which to host the other Allies,Footnote 85 it was via comestibles that they confirmed their national identity, to themselves as much as to others. In contrast to the British, diners at a French banquet a week or two earlier were served, among other dishes, a ‘French-style platter’, ‘Toulouse-style roast beef’, ‘Paris potatoes’, ‘Agen prunes’, ‘Provençal cakes’, champagne, southern French white wine and cognac.Footnote 86 It is not just the Frenchness of this food that is splendidly reiterated; this menu is a solid Republican affair. It does not favour one region over another, but gathers the best of France (as available in 1945) into one coherent whole. It is doubtful that the experience of being in occupied Germany led the occupiers to lose interest in French regional food differences, which were not as marked in this period as might be imagined; more probably, it was the later internationalisation of cuisine that led to more emphasis on ‘national’ and ‘regional’ foods, so that they no longer served to characterise different national groups.Footnote 87 In any case, French regional and local preferences – which depended substantially on garden produce – began to lose their specificity after 1850 as new communications systems opened up trade and exchange.Footnote 88

To return to the Kommandatura banquets, they were served largely to men but it is unlikely that the économat would have continued to operate had the French population in Germany not included significant numbers of women. Some French women were recruited to the women's army section, the Arme féminine de l'Armée de Terre, while others were civilians incorporated like men into the military command. All were channelled into acceptably feminine occupations such as telephonists, typists and nurses. The majority of French women in the Zone and Berlin were, however, wives, and it is thanks to them that the économat enabled the development of a durable version of a French home in Germany. Indeed, their very presence was used to justify the continued existence of the économat. They were represented on the Economat Council, and it had been to the économat that dismayed Berlin commanders turned when women began to arrive in the city.Footnote 89

According to Edgar Morin, little affinity existed between the French and German communities, which barely integrated with each other.Footnote 90 This seems entirely unlikely if we take gender into account. Had that been the case, the General Command would have had no need to ban marriages between French military men and German women in September 1945,Footnote 91 a ban which lasted until 1948. In a region where the female population outnumbered the male in even higher proportions than elsewhere in Germany,Footnote 92 contact between French and Germans would have occurred within the économat from shortly after their establishment, though they were initially staffed by German prisoners of war. By 1946, the économat employed German women, bringing the French population into direct and frequent contact with the German (though not all customers would have gone to gaze daily on their object of stupefied desire, like translator Alain Bosquet, whose infatuation with a seventeen-year-old sales assistant propelled him to buy unwanted goods such as ‘lamb's tongue’ and ‘tiny biscuits probably meant for dogs’).Footnote 93

French women were assumed to do the shopping and cookingFootnote 94 and, despite the Revue d'Information being a magazine explicitly for soldiers, they were directly appealed to as mothers, via advertisements for family vacations or food attractive to children, as well as indirectly by the many articles on tourism in Germany. Women's identity as female and French was confirmed by their consumption of particular products in which the économat took a leading role. Indeed, just as the économat had an ideological function in terms of reasserting an idea of Frenchness through obviously French products, so it sold a certain idea of gender too. Madame Koenig, wife of the first commanding general, herself promoted the major post-war French pro-natalist drive launched by Charles de Gaulle, and she was used to persuade the économat to stock and distribute baby products to pregnant women and to encourage others to reproduce. The économat responded positively to the message to display these special goods with a view to encouraging reproduction.Footnote 95 But the gendered form of Frenchness that the économat promoted was not confined to the very obvious one of women as mothers. Its concern to stock products of direct appeal to women in the form of decorative treats known as ‘articles de Paris’ – inexpensive costume jewellery, perfume, scarves, ornaments of obviously French character, and so on – indicates the significance of women in the Zone as consumers who would be tempted by the indulgences that were very occasionally available, and continually advertised. The presence of these commodities, which in the 1930s had been disparaged as dangerous signs of feminine decadence, alongside goods already gendered female, such as food, asserted the économat's identity as a place for women within the male military zone, while simultaneously inviting them to insist on a version of remembered Frenchness. The one was embedded in the other.

Conclusion

The manifestation of all these goods and campaigns go some way to support the argument advanced here that the économat was part of French implantation for the French. Unlike France's interest in cultural policy, social policy or denazification in the Zone, they were promoted not for Germans, but for French people. Economat shops were not shiny showcases but dimly lit, small outlets that, once distinct French enclaves had been built towards the end of the 1940s, and housing was no longer requisitioned, were hidden from German eyes. Whereas Marilyn Halter argues in her work on ethnic identity and shopping in the US that ‘exalting a particular culture and making money while doing it are not necessarily antithetical. Naturally, the bottom line is increasing sales, and in these times [the 1970s] one of the primary strategies to accomplish this goal is to broaden the consumer base by finding new audiences’,Footnote 96 for the économats, the aim was neither to make money, nor to find new customers. So that the French could insist on their Frenchness they needed to shop and eat in French style. As the menu described earlier indicates, this was a conglomeration of the best of regional produce that could be mustered in 1945 that, together, in true Republican style, would produce a single whole. It was by supplying French people, not their Allied guests or German neighbours, that a notion of French ‘at-home-ness’ could be imparted and embedded.

Within a history of consumption, the économat occupies a singular place, with little work having been done on this sort of transnational and intercultural trade. As a closed system of trading, the économat probably resembles conditions in the German Democratic Republic more than the Federal Republic or France itself.Footnote 97 Fruitful relations with shopkeepers needed to be developed for a chance to obtain goods in short supply, and the array of stock was determined by a state agency, in this case the army, with all the attendant bureaucratic anomalies and annoyances that this implied for customers (and the archives reveal them as manifold). But whereas the amount of food one could buy in the early GDR was fundamentally determined by the consumer's labour in terms of his (and it was generally his) expenditure of physical energy, women's unpaid domestic labour being sidelined,Footnote 98 rations at the économat were determined by the consumer's nationality, and sales by the consumer's gender. Women shoppers were essential to the économat's very survival.

Moreover, if a shift from producer-led to demand-led consumption and the production of identities via what people buy has been dated to the last third of the twentieth century,Footnote 99 the earlier économat embodied neither of these. In the hungry immediate post-war years, it was the army and shop/distributor itself, as intermediary between producer and consumer, which in many ways determined demand for goods, and that in turn constituted in large part a goods-based French identity. In its insistence on having French products available, rather than asking residents to adapt to German ones, and selling them in a familiar, poky environment, the économat continually contrived a certain kitsch nostalgia for a provincial version of France.Footnote 100 French – or ‘ethnic’ – essentials formed the core concerns: beef (not German pork), wine (not beer), vegetables, bread. All caused a problem, and all help to define the consumer. They also helped to define the community that the consumers made. By selling Frenchness as its main commodity, the économat gained a position which gave it the economic force to persist in West Germany until the French departed half a century after their arrival. Neither colony, nor France, the ZFO was run by a military with few normal military functions. In promoting the Frenchness of the product as something of value in itself (regardless of the often poor quality), the économat produced an identification with France that it reinforced every day as the French women of south-west Germany went out shopping.

This article has suggested that the logic and function of retail in the ZFO was not to provide a shop window onto France for Germans, and that as a commercial, capitalist enterprise, the économat was nonsensical. Its often disgruntled customers were, however, persuaded that it was worth shopping there because it provided something more than basic goods. A key work on gender and consumption argued that,

the process of negotiation among persons with an affective as well as material stake in this joint enterprise – usually wife and husband, but also older and younger generations . . . would seem to shape profoundly what kinds of goods are purchased, what services are delegated to or reappropriated from the market, and what values are attached to goods in the pursuit of family wellbeing.Footnote 101

Consumption thus makes the family; how it does, though, changes with context. The économat arguably presented a variant of this process: family wellbeing did not simply define the type of goods that were available, but permitted and justified their availability in the first place in an army made up of families. As we know, the ‘military’ government in Germany was in large measure not military, but consisted of civilians dressing up in military costume; it was also a military that disdained the usual army functions of fighting war or aggressively subduing hostile populations. These factors explain its atypical gender make-up and made it more like home, though a rather inward-looking and nostalgic one, ‘with its own clubs and societies, shows, sports clubs and championships, its provincial societies and excursions by “the Rhineland Bretons” or “the Lake Constance Corsicans”.’Footnote 102 In the years before distinct enclaves were built, occupying forces lived in requisitioned housing. Shops provided an important reaffirmation of who residents were, and a sense of community.Footnote 103 The Zone's peculiar ‘landscape of consumption’Footnote 104 contrasts with scholarly focus on sites of plenty – such as theme parks, department stores and shopping malls – and French cantonments in post-war Germany were characterised by shortages and hunger. The places explored here were neither spectacular nor particularly public, but hidden away. The économat was less the showy ‘store of tomorrow’ with its automation and lack of salespeople exhibited at the 1947 French Packaging Fair,Footnote 105 and more like the store of yesterday. It was dingy (perhaps because there were so few light bulbs),Footnote 106 queues were long, opening hours were inconvenient and produce was expensive. But for the nascent French community in West Germany, the économat provided the necessities that confirmed one's qualities as French. And when the économat faced closure, its continued existence was justified on the grounds of its fundamental importance to families. The French officer class in Germany, in the early post-war construction of a military society that was a little like civil society, needed wives, and the homes that having a wife implied, if their ennui were not to propel them into the nausea described by Morin or into becoming the assimilated Germans feared by the Stuttgart consul. In just five years, the exasperation that greeted women's arrival in 1945 – ‘once and for all, we must answer in the negative all questions about whether families can come’Footnote 107 – had not merely transformed into acceptance, but had become a necessity. Germany could now be a real French home.